Submitted:

11 July 2025

Posted:

11 July 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

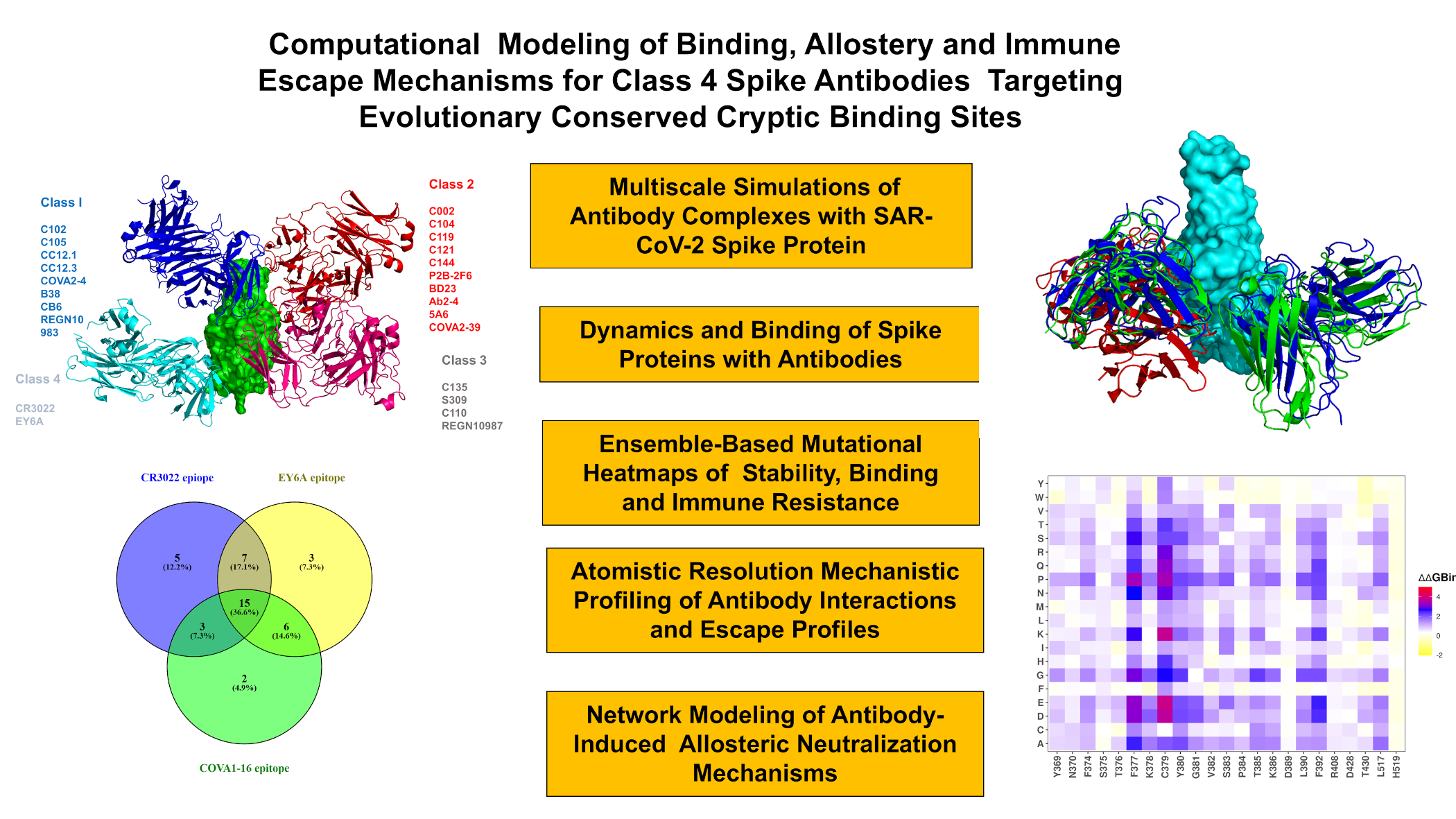

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Coarse-Grained Simulations Molecular Dynamics Simulations

2.2. Molecular Dynamics Simulations

2.3. Mutational Scanning Profiling

2.4. Binding Free Energy Computations

2.5. Modeling of Residue Interaction Networks

2.6. Network-Based Mutational Profiling of Allosteric Residue Centrality

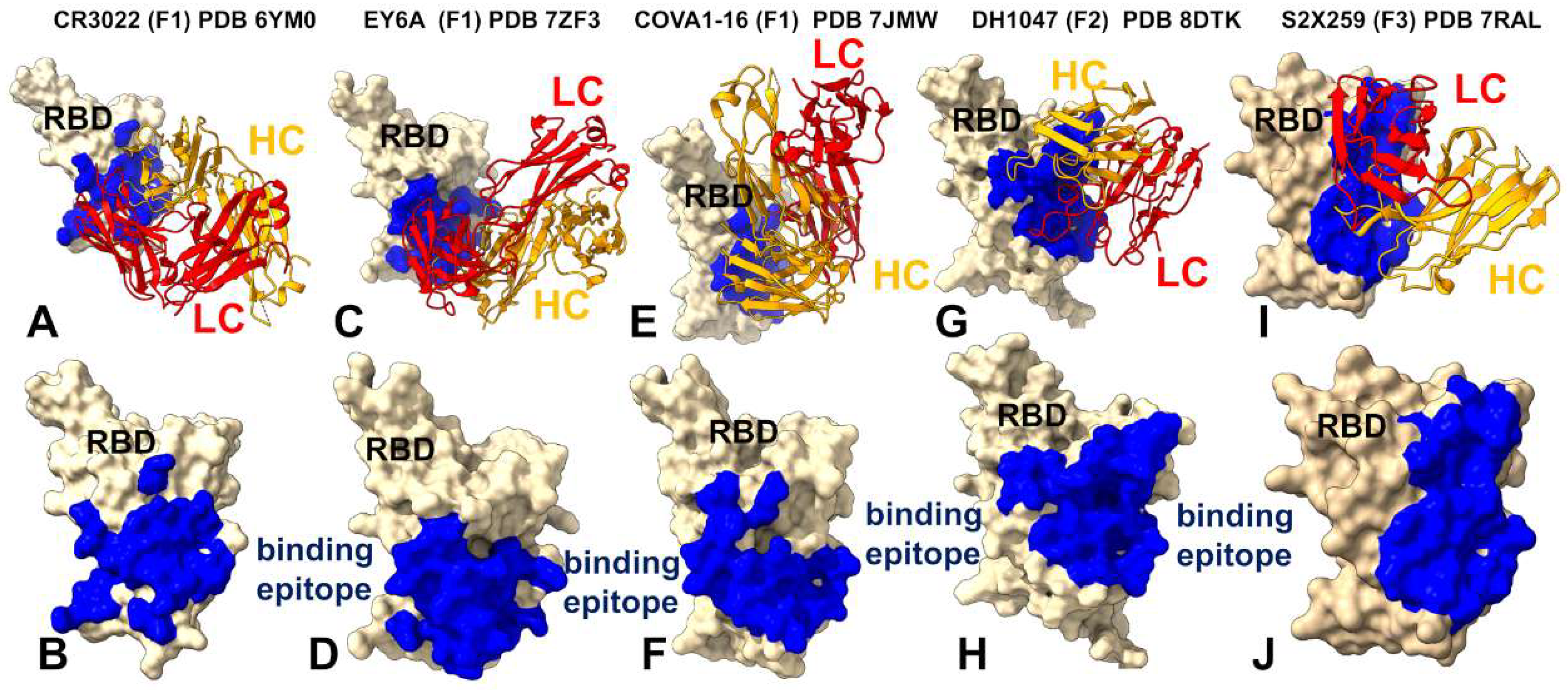

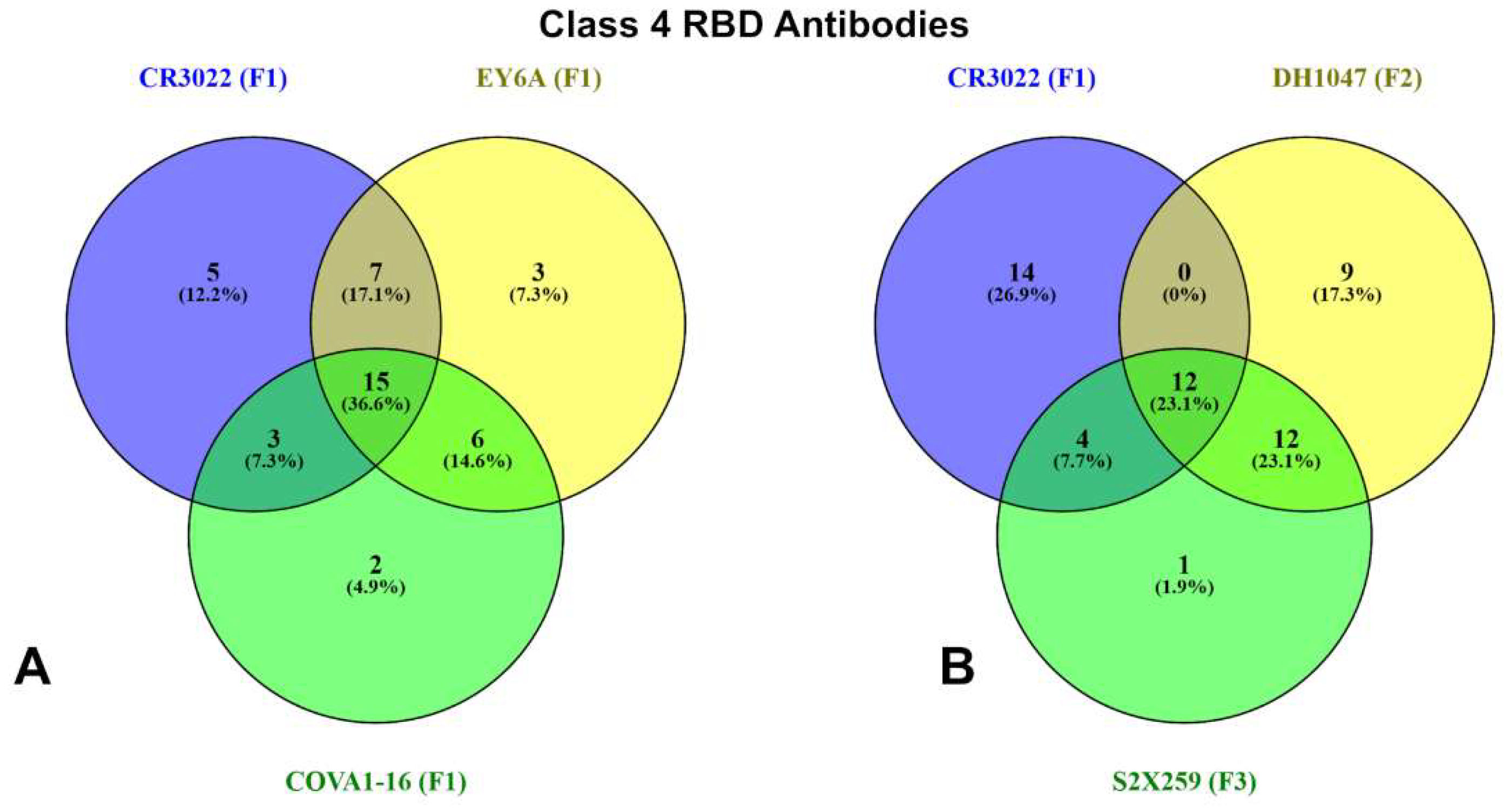

3. Results

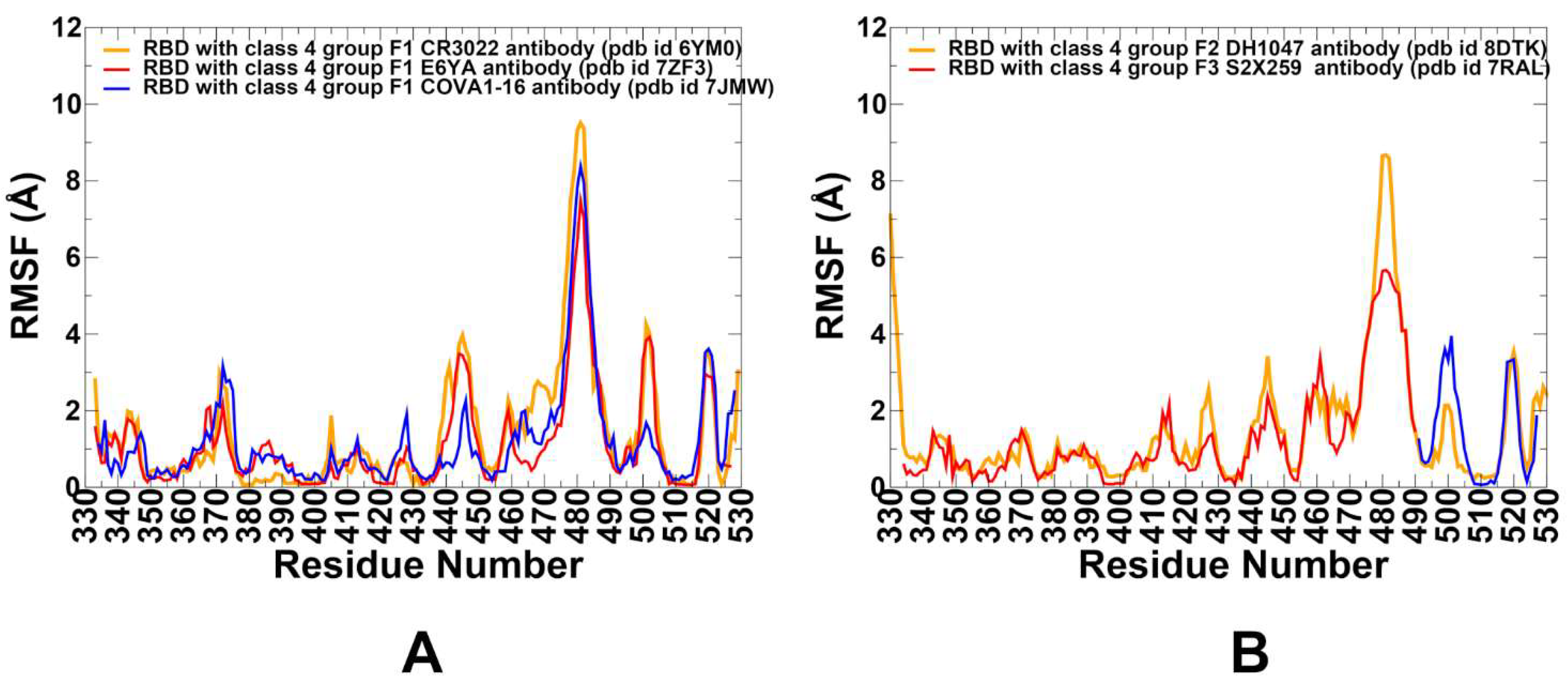

3.2. Conformational Dynamics of the RBD Complexes with Antibodies Using Coarse-Grained and Atomistic Simulations

3.3. Mutational Profiling of Antibody-RBD Binding Interactions Interfaces Reveals Molecular Determinants of Immune Sensitivity and Emergence of Convergent Escape Hotspots

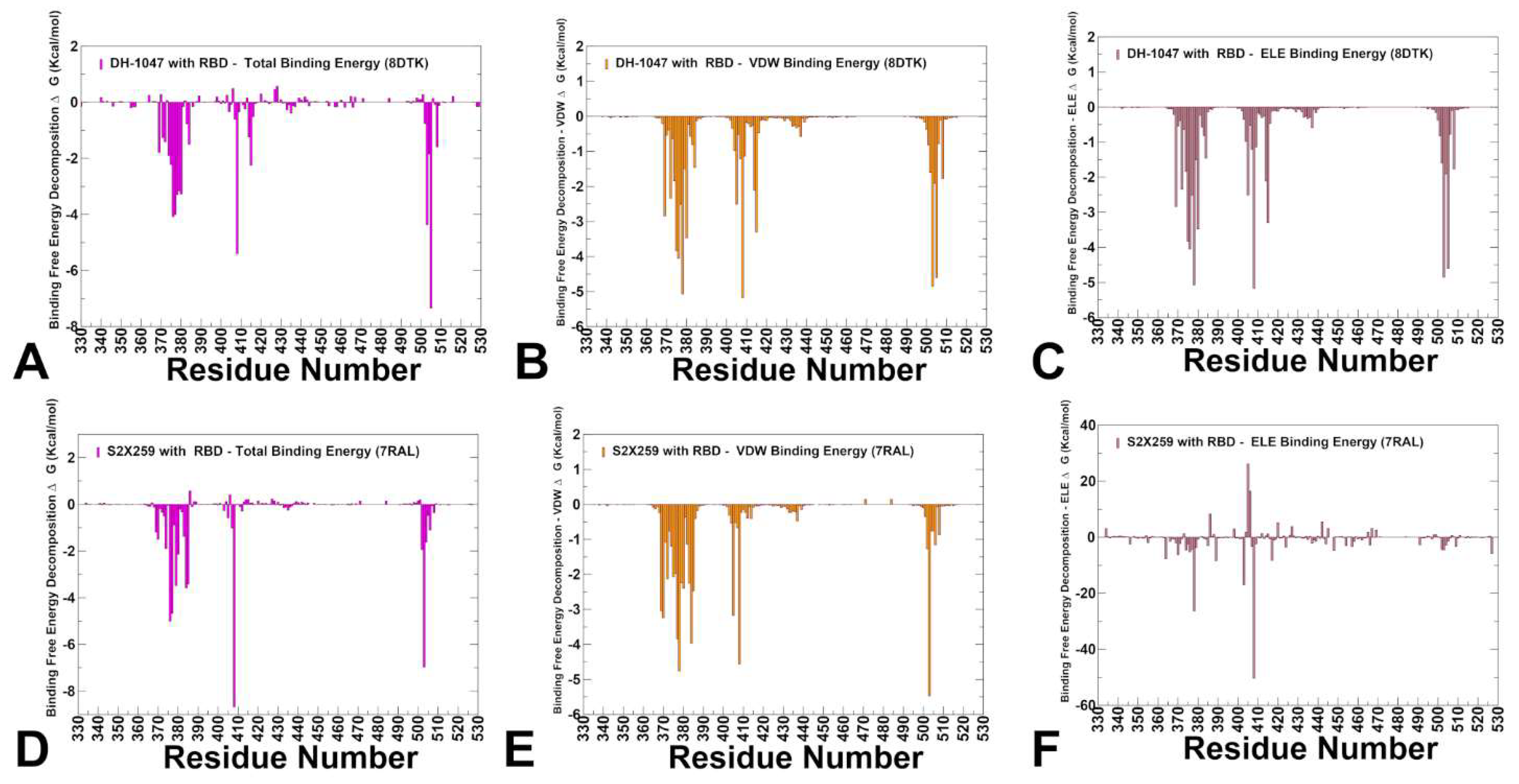

3.4. MM-GBSA Analysis of the Binding Energetics for Class 4 Antibodies Complexes

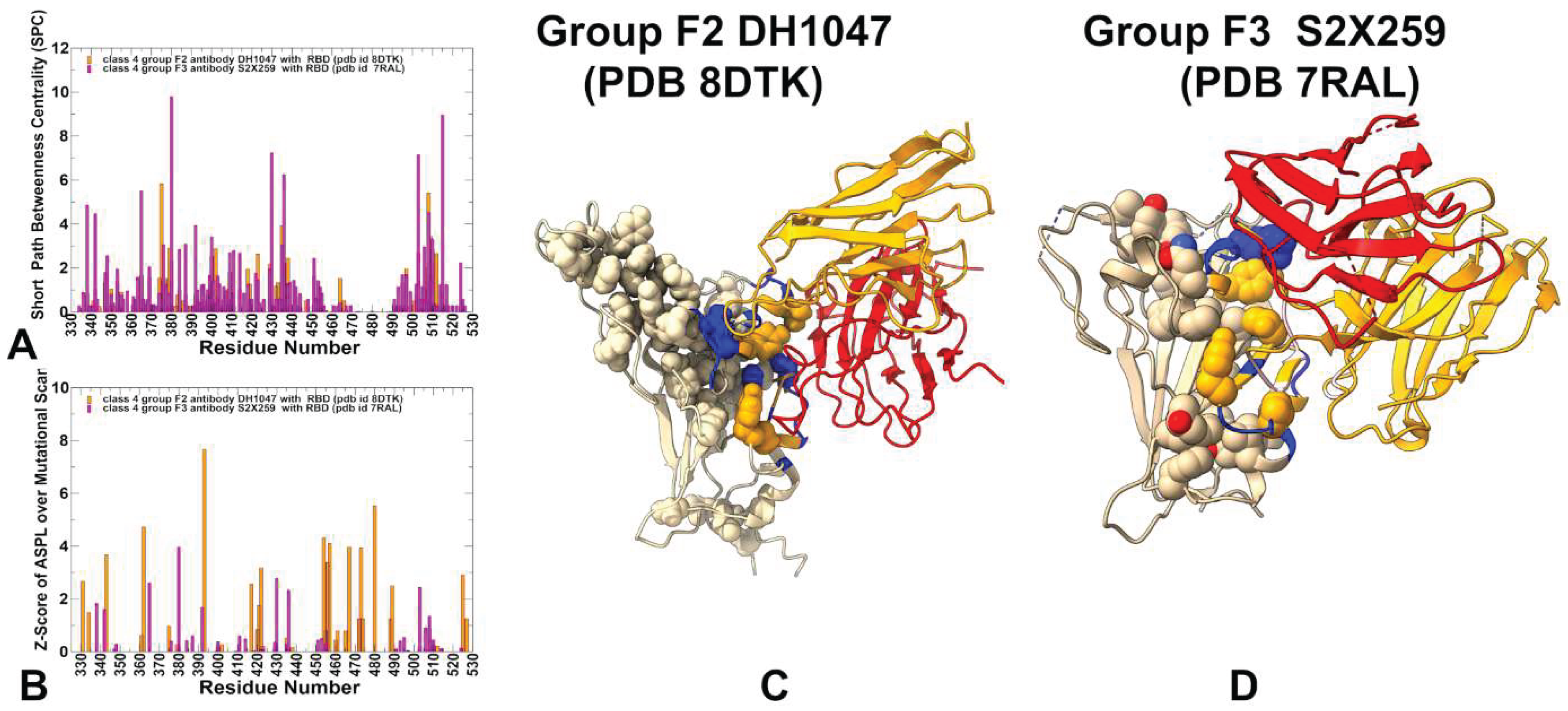

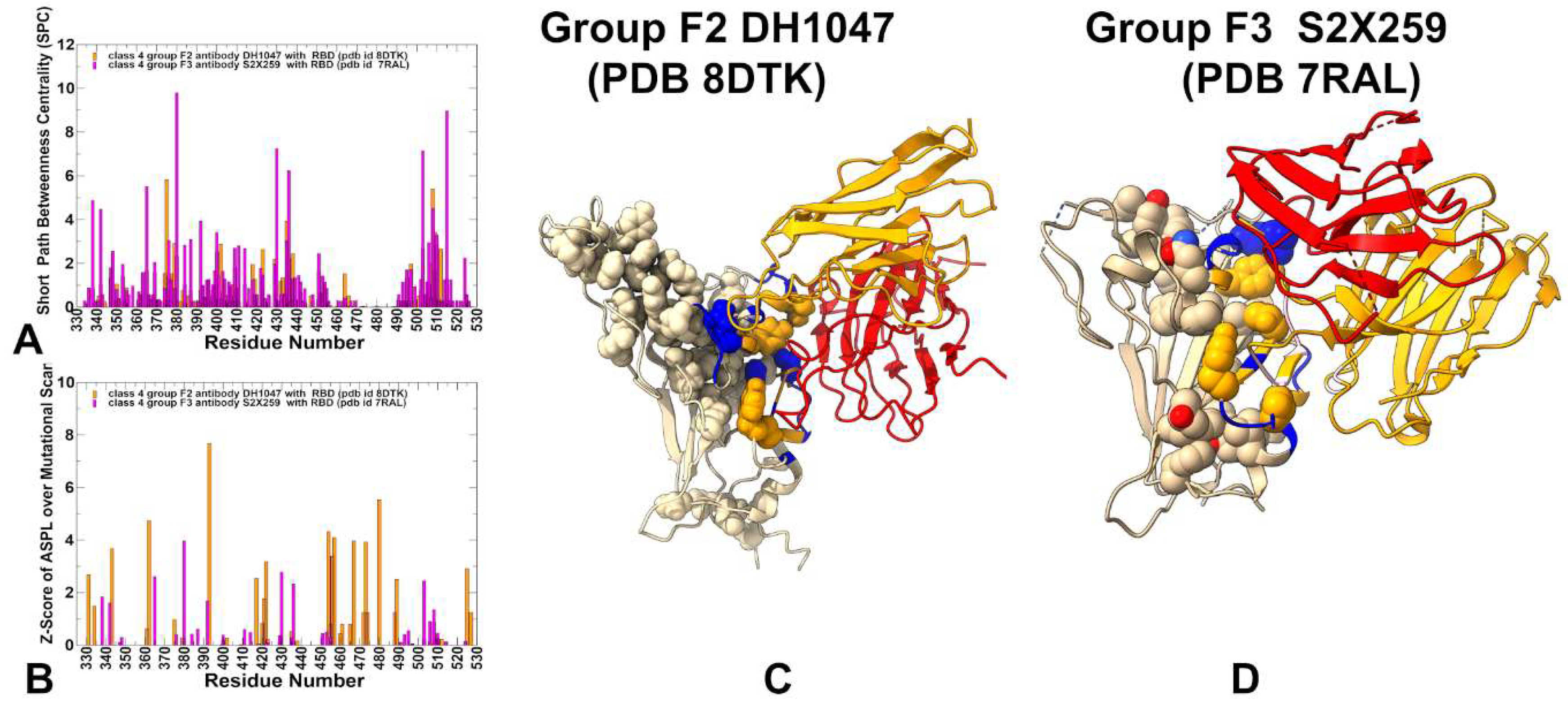

3.5. Exploring Allosteric Binding Pathways Using Dynamic Network Analysis

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Tai, W.; He, L.; Zhang, X.; Pu, J.; Voronin, D.; Jiang, S.; Zhou, Y.; Du, L. Characterization of the receptor-binding domain (RBD) of 2019 novel coronavirus: implication for development of RBD protein as a viral attachment inhibitor and vaccine. Cell. Mol. Immunol. 2020, 17, 613–620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Q.; Zhang, Y.; Wu, L.; Niu, S.; Song, C.; Zhang, Z.; Lu, G.; Qiao, C.; Hu, Y.; Yuen, K. Y.; Wang, Q.; Zhou, H.; Yan, J.; Qi, J. Structural and functional basis of SARS-CoV-2 entry by using human ACE2. Cell 2020, 181, 894–904.e9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Walls, A. C.; Park, Y. J.; Tortorici, M. A.; Wall, A.; McGuire, A. T.; Veesler, D. Structure, Function, and Antigenicity of the SARS-CoV-2 Spike Glycoprotein. Cell 2020, 181, 281–292.e6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wrapp, D.; Wang, N.; Corbett, K. S.; Goldsmith, J. A.; Hsieh, C. L.; Abiona, O.; Graham, B. S.; McLellan, J. S. Cryo-EM structure of the 2019-nCoV spike in the prefusion conformation. Science 2020, 367, 1260–1263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, Y.; Zhang, J.; Xiao, T.; Peng, H.; Sterling, S. M.; Walsh, R. M., Jr.; Rawson, S.; Rits-Volloch, S.; Chen, B. Distinct conformational states of SARS-CoV-2 spike protein. Science 2020, 369, 1586–1592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsieh, C. L.; Goldsmith, J. A.; Schaub, J. M.; DiVenere, A. M.; Kuo, H. C.; Javanmardi, K.; Le, K. C.; Wrapp, D.; Lee, A. G.; Liu, Y. , Chou, C.W.; Byrne, P.O.; Hjorth, C.K.; Johnson, N.V.; Ludes-Meyers J.; Nguyen, A.W.; Park, J.; Wang, N.; Amengor, D.; Lavinder, J.J.; Ippolito, G.C.; Maynard, J.A.; Finkelstein, I.J.; McLellan, J.S. Structure-based design of prefusion-stabilized SARS-CoV-2 spikes. Science 2020, 369, 1501–1505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henderson, R.; Edwards, R. J.; Mansouri, K.; Janowska, K.; Stalls, V.; Gobeil, S. M. C.; Kopp, M.; Li, D.; Parks, R.; Hsu, A. L. , Borgnia, M.J.; Haynes, B.F.; Acharya, P. Controlling the SARS-CoV-2 spike glycoprotein conformation. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 2020, 27, 925–933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCallum, M.; Walls, A. C.; Bowen, J. E.; Corti, D.; Veesler, D. Structure-guided covalent stabilization of coronavirus spike glycoprotein trimers in the closed conformation. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 2020, 27, 942–949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiong, X.; Qu, K.; Ciazynska, K. A.; Hosmillo, M.; Carter, A. P.; Ebrahimi, S.; Ke, Z.; Scheres, S. H. W.; Bergamaschi, L.; Grice, G. L. , Zhang, Y.; CITIID-NIHR COVID-19 BioResource Collaboration, Nathan, J.A.; Baker, S.; James, L.C.; Baxendale, H.E.; Goodfellow, I.; Doffinger, R.; Briggs, J.A.G. A thermostable, closed SARS-CoV-2 spike protein trimer. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 2020, 27, 934–941. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costello, S.M.; Shoemaker, S.R.; Hobbs, H.T.; Nguyen, A.W.; Hsieh, C.L.; Maynard, J.A.; McLellan, J.S.; Pak, J.E.; Marqusee, S. The SARS-CoV-2 spike reversibly samples an open-trimer conformation exposing novel epitopes. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 2022, 27, 229–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCormick, K.D.; Jacobs, J.L.; Mellors, J.W. The emerging plasticity of SARS-CoV-2. Science 2021, 371, 1306–1308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghimire, D.; Han, Y.; Lu, M. Structural Plasticity and Immune Evasion of SARS-CoV-2 Spike Variants. Viruses 2022, 14, 1255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, C.; Wang, Y.; Liu, C.; Zhang, C. ; Han,W.; Hong, X.; Wang, Y.; Hong, Q.; Wang, S.; Zhao, Q.; Wang, Y.; Yang, Y.; Chen, K.; Zheng, W.; Kong, L.; Wang, F.; Zuo, Q.; Huang, Z.; Cong, Y. Conformational dynamics of SARS-CoV-2 trimeric spike glycoprotein in complex with receptor ACE2 revealed by cryo-EM. Sci. Adv. 5575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benton, D. J.; Wrobel, A. G.; Xu, P.; Roustan, C.; Martin, S. R.; Rosenthal, P. B.; Skehel, J. J.; Gamblin, S. J. Receptor binding and priming of the spike protein of SARS-CoV-2 for membrane fusion. Nature 2020, 588, 327–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Turoňová, B.; Sikora, M.; Schuerman, C.; Hagen, W. J. H.; Welsch, S.; Blanc, F. E. C.; von Bülow, S.; Gecht, M.; Bagola, K.; Hörner, C.; van Zandbergen, G.; Landry, J.; de Azevedo, N. T. D.; Mosalaganti, S.; Schwarz, A.; Covino, R.; Mühlebach, M. D.; Hummer, G.; Krijnse Locker, J.; Beck, M. In situ structural analysis of SARS-CoV-2 spike reveals flexibility mediated by three hinges. Science 2020, 370, 203–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lu, M.; Uchil, P. D.; Li, W.; Zheng, D.; Terry, D. S.; Gorman, J.; Shi, W.; Zhang, B.; Zhou, T.; Ding, S.; Gasser, R.; Prevost, J.; Beaudoin-Bussieres, G.; Anand, S. P.; Laumaea, A.; Grover, J. R.; Lihong, L.; Ho, D. D.; Mascola, J.R.; Finzi, A.; Kwong, P. D.; Blanchard, S. C.; Mothes, W. Real-time conformational dynamics of SARS-CoV-2 spikes on virus particles. Cell Host Microbe. 2020, 28, 880–891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Z.; Han, Y.; Ding, S.; Shi, W.; Zhou, T.; Finzi, A.; Kwong, P.D.; Mothes, W.; Lu, M. SARS-CoV-2 Variants Increase Kinetic Stability of Open Spike Conformations as an Evolutionary Strategy. mBio 2022, 13, e0322721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Díaz-Salinas, M.A.; Li, Q.; Ejemel, M.; Yurkovetskiy, L.; Luban, J.; Shen, K.; Wang, Y.; Munro, J.B. Conformational dynamics and allosteric modulation of the SARS-CoV-2 spike. Elife 2022, 11, e75433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Liu, C.; Zhang, C.; Wang, Y.; Hong, Q.; Xu, S.; Li, Z.; Yang, Y.; Huang, Z.; Cong, Y. Structural Basis for SARS-CoV-2 Delta Variant Recognition of ACE2 Receptor and Broadly Neutralizing Antibodies. Nat. Commun. 2022, 13, 871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mannar, D.; Saville, J.W.; Zhu, X.; Srivastava, S.S.; Berezuk, A.M.; Tuttle, K.S.; Marquez, A.C.; Sekirov, I.; Subramaniam, S. SARS-CoV-2 Omicron Variant: Ab Evasion and Cryo-EM Structure of Spike Protein–ACE2 Complex. Science 2022, 375, 760–764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, Q.; Han, W.; Li, J.; Xu, S.; Wang, Y.; Xu, C.; Li, Z.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, C.; Huang, Z.; Cong, Y. Molecular Basis of Receptor Binding and Ab Neutralization of Omicron. Nature 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCallum, M.; Czudnochowski, N.; Rosen, L.E.; Zepeda, S.K.; Bowen, J.E.; Walls, A.C.; Hauser, K.; Joshi, A.; Stewart, C.; Dillen, J.R.; Powell, A.E.; Croll, T.I.; Nix, J.; Virgin, H.W.; Corti, D.; Snell, G.; Veesler, D. Structural Basis of SARS-CoV-2 Omicron Immune Evasion and Receptor Engagement. Science 2022, 375, 864–868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, W.; Xu, Y.; Xu, P.; Cao, X.; Wu, C.; Gu, C.; He, X.; Wang, X.; Huang, S.; Yuan, Q.; Wu, K.; Hu, W.; Huang, Z.; Liu, J.; Wang, Z.; Jia, F.; Xia, K.; Liu, P.; Wang, X.; Song, B.; Zheng, J.; Jiang, H.; Cheng, X.; Jiang, Y.; Deng, S.J.; Xu, H.E. Structures of the Omicron Spike Trimer with ACE2 and an Anti-Omicron Ab. Science 2022, 375, 1048–1053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gobeil, S. M.-C.; Henderson, R.; Stalls, V.; Janowska, K.; Huang, X.; May, A.; Speakman, M.; Beaudoin, E.; Manne, K.; Li, D.; Parks, R.; Barr, M.; Deyton, M.; Martin, M.; Mansouri, K.; Edwards, R. J.; Eaton, A.; Montefiori, D. C.; Sempowski, G. D.; Saunders, K. O.; Wiehe, K.; Williams, W.; Korber, B.; Haynes, B. F.; Acharya, P. Structural Diversity of the SARS-CoV-2 Omicron Spike. Mol Cell. 2022, 82, 2050–2068.e6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cui, Z.; Liu, P.; Wang, N.; Wang, L.; Fan, K.; Zhu, Q.; Wang, K.; Chen, R.; Feng, R.; Jia, Z.; Yang, M.; Xu, G.; Zhu, B.; Fu, W.; Chu, T.; Feng, L.; Wang, Y.; Pei, X.; Yang, P.; Xie, X.S.; Cao, L.; Cao, Y.; Wang, X. Structural and Functional Characterizations of Infectivity and Immune Evasion of SARS-CoV-2 Omicron. Cell 2022, 185, 860-871.e13. [CrossRef]

- Cao, Y.; Wang, J.; Jian, F.; Xiao, T.; Song, W.; Yisimayi, A.; Huang, W.; Li, Q.; Wang, P.; An, R.; Wang, J.; Wang, Y.; Niu, X.; Yang, S.; Liang, H.; Sun, H.; Li, T.; Yu, Y.; Cui, Q.; Liu, S.; Yang, X.; Du, S.; Zhang, Z.; Hao, X.; Shao, F.; Jin, R.; Wang, X.; Xiao, J.; Wang, Y.; Xie, X. S. Omicron Escapes the Majority of Existing SARS-CoV-2 Neutralizing Antibodies. Nature 2022, 602, 657–663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cao, Y.; Yisimayi, A.; Jian, F.; Song, W.; Xiao, T.; Wang, L.; Du, S.; Wang, J.; Li, Q.; Chen, X.; Yu, Y.; Wang, P.; Zhang, Z.; Liu, P.; An, R.; Hao, X.; Wang, Y.; Wang, J.; Feng, R.; Sun, H.; Zhao, L.; Zhang, W.; Zhao, D.; Zheng, J.; Yu, L.; Li, C.; Zhang, N.; Wang, R.; Niu, X.; Yang, S.; Song, X.; Chai, Y.; Hu, Y.; Shi, Y.; Zheng, L.; Li, Z.; Gu, Q.; Shao, F.; Huang, W.; Jin, R.; Shen, Z.; Wang, Y.; Wang, X.; Xiao, J.; Xie, X. S. BA. 2.12.1, BA.4 and BA.5 Escape Antibodies Elicited by Omicron Infection. Nature 2022, 608, 593–602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinto, D.; Park, Y.-J.; Beltramello, M.; Walls, A. C.; Tortorici, M. A.; Bianchi, S.; Jaconi, S.; Culap, K.; Zatta, F.; De Marco, A.; Peter, A.; Guarino, B.; Spreafico, R.; Cameroni, E.; Case, J. B.; Chen, R. E.; Havenar-Daughton, C.; Snell, G.; Telenti, A.; Virgin, H. W.; Lanzavecchia, A.; Diamond, M. S.; Fink, K.; Veesler, D.; Corti, D. Cross-Neutralization of SARS-CoV-2 by a Human Monoclonal SARS-CoV Antibody. Nature 2020, 583, 290–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tortorici, M. A.; Beltramello, M.; Lempp, F. A.; Pinto, D.; Dang, H. V.; Rosen, L. E.; McCallum, M.; Bowen, J.; Minola, A.; Jaconi, S.; Zatta, F.; De Marco, A.; Guarino, B.; Bianchi, S.; Lauron, E. J.; Tucker, H.; Zhou, J.; Peter, A.; Havenar-Daughton, C.; Wojcechowskyj, J. A.; Case, J. B.; Chen, R. E.; Kaiser, H.; Montiel-Ruiz, M.; Meury, M.; Czudnochowski, N.; Spreafico, R.; Dillen, J.; Ng, C.; Sprugasci, N.; Culap, K.; Benigni, F.; Abdelnabi, R.; Foo, S.-Y. C.; Schmid, M. A.; Cameroni, E.; Riva, A.; Gabrieli, A.; Galli, M.; Pizzuto, M. S.; Neyts, J.; Diamond, M. S.; Virgin, H. W.; Snell, G.; Corti, D.; Fink, K.; Veesler, D. Ultrapotent Human Antibodies Protect against SARS-CoV-2 Challenge via Multiple Mechanisms. Science 2020, 370, 950–957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosen, L. E.; Tortorici, M. A.; De Marco, A.; Pinto, D.; Foreman, W. B.; Taylor, A. L.; Park, Y.-J.; Bohan, D.; Rietz, T.; Errico, J. M.; Hauser, K.; Dang, H. V.; Chartron, J. W.; Giurdanella, M.; Cusumano, G.; Saliba, C.; Zatta, F.; Sprouse, K. R.; Addetia, A.; Zepeda, S. K.; Brown, J.; Lee, J.; Dellota, E., Jr.; Rajesh, A.; Noack, J.; Tao, Q.; DaCosta, Y.; Tsu, B.; Acosta, R.; Subramanian, S.; de Melo, G. D.; Kergoat, L.; Zhang, I.; Liu, Z.; Guarino, B.; Schmid, M. A.; Schnell, G.; Miller, J. L.; Lempp, F. A.; Czudnochowski, N.; Cameroni, E.; Whelan, S. P. J.; Bourhy, H.; Purcell, L. A.; Benigni, F.; di Iulio, J.; Pizzuto, M. S.; Lanzavecchia, A.; Telenti, A.; Snell, G.; Corti, D.; Veesler, D.; Starr, T. N. A Potent Pan-Sarbecovirus Neutralizing Antibody Resilient to Epitope Diversification. Cell 2024, 187, 7196–7213.e26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, M.; Wu, N. C.; Zhu, X.; Lee, C.-C. D.; So, R. T. Y.; Lv, H.; Mok, C. K. P.; Wilson, I. A. A Highly Conserved Cryptic Epitope in the Receptor Binding Domains of SARS-CoV-2 and SARS-CoV. Science. 2020, 368, 630–633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piccoli, L.; Park, Y.-J.; Tortorici, M. A.; Czudnochowski, N.; Walls, A. C.; Beltramello, M.; Silacci-Fregni, C.; Pinto, D.; Rosen, L. E.; Bowen, J. E.; Acton, O. J.; Jaconi, S.; Guarino, B.; Minola, A.; Zatta, F.; Sprugasci, N.; Bassi, J.; Peter, A.; De Marco, A.; Nix, J. C.; Mele, F.; Jovic, S.; Rodriguez, B. F.; Gupta, S. V.; Jin, F.; Piumatti, G.; Lo Presti, G.; Pellanda, A. F.; Biggiogero, M.; Tarkowski, M.; Pizzuto, M. S.; Cameroni, E.; Havenar-Daughton, C.; Smithey, M.; Hong, D.; Lepori, V.; Albanese, E.; Ceschi, A.; Bernasconi, E.; Elzi, L.; Ferrari, P.; Garzoni, C.; Riva, A.; Snell, G.; Sallusto, F.; Fink, K.; Virgin, H. W.; Lanzavecchia, A.; Corti, D.; Veesler, D. Mapping Neutralizing and Immunodominant Sites on the SARS-CoV-2 Spike Receptor-Binding Domain by Structure-Guided High-Resolution Serology. Cell 2020, 183, 1024–1042.e21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martinez, D. R.; Schäfer, A.; Gobeil, S.; Li, D.; De la Cruz, G.; Parks, R.; Lu, X.; Barr, M.; Stalls, V.; Janowska, K.; Beaudoin, E.; Manne, K.; Mansouri, K.; Edwards, R. J.; Cronin, K.; Yount, B.; Anasti, K.; Montgomery, S. A.; Tang, J.; Golding, H.; Shen, S.; Zhou, T.; Kwong, P. D.; Graham, B. S.; Mascola, J. R.; Montefiori, D. C.; Alam, S. M.; Sempowski, G. D.; Khurana, S.; Wiehe, K.; Saunders, K. O.; Acharya, P.; Haynes, B. F.; Baric, R. S. A Broadly Cross-Reactive Antibody Neutralizes and Protects against Sarbecovirus Challenge in Mice. Sci Transl Med. 2022, 14, eabj7125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rappazzo, C. G.; Tse, L. V.; Kaku, C. I.; Wrapp, D.; Sakharkar, M.; Huang, D.; Deveau, L. M.; Yockachonis, T. J.; Herbert, A. S.; Battles, M. B.; O’Brien, C. M.; Brown, M. E.; Geoghegan, J. C.; Belk, J.; Peng, L.; Yang, L.; Hou, Y.; Scobey, T. D.; Burton, D. R.; Nemazee, D.; Dye, J. M.; Voss, J. E.; Gunn, B. M.; McLellan, J. S.; Baric, R. S.; Gralinski, L. E.; Walker, L. M. Broad and Potent Activity against SARS-like Viruses by an Engineered Human Monoclonal Antibody. Science. 2021, 371, 823–829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yuan, M.; Zhu, X.; He, W.; Zhou, P.; Kaku, C. I.; Capozzola, T.; Zhu, C. Y.; Yu, X.; Liu, H.; Yu, W.; Hua, Y.; Tien, H.; Peng, L.; Song, G.; Cottrell, C. A.; Schief, W. R.; Nemazee, D.; Walker, L. M.; Andrabi, R.; Burton, D. R.; Wilson, I. A. A Broad and Potent Neutralization Epitope in SARS-Related Coronaviruses. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2022, 119, e2205784119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barnes, C. O.; Jette, C. A.; Abernathy, M. E.; Dam, K.-M. A.; Esswein, S. R.; Gristick, H. B.; Malyutin, A. G.; Sharaf, N. G.; Huey-Tubman, K. E.; Lee, Y. E.; Robbiani, D. F.; Nussenzweig, M. C.; West, A. P., Jr; Bjorkman, P. J. SARS-CoV-2 Neutralizing Antibody Structures Inform Therapeutic Strategies. Nature 2020, 588, 682–687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, Y.; Jian, F.; Wang, J.; Yu, Y.; Song, W.; Yisimayi, A.; Wang, J.; An, R.; Chen, X.; Zhang, N.; Wang, Y.; Wang, P.; Zhao, L.; Sun, H.; Yu, L.; Yang, S.; Niu, X.; Xiao, T.; Gu, Q.; Shao, F.; Hao, X.; Xu, Y.; Jin, R.; Shen, Z.; Wang, Y.; Xie, X. S. Imprinted SARS-CoV-2 Humoral Immunity Induces Convergent Omicron RBD Evolution. Nature 2023, 614, 521–529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jian, F.; Wang, J.; Yisimayi, A.; Song, W.; Xu, Y.; Chen, X.; Niu, X.; Yang, S.; Yu, Y.; Wang, P.; Sun, H.; Yu, L.; Wang, J.; Wang, Y.; An, R.; Wang, W.; Ma, M.; Xiao, T.; Gu, Q.; Shao, F.; Wang, Y.; Shen, Z.; Jin, R.; Cao, Y. Evolving Antibody Response to SARS-CoV-2 Antigenic Shift from XBB to JN.1. Nature 2025, 637, 921–929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, Y.; Jian, F.; Zhang, Z.; Yisimayi, A.; Hao, X.; Bao, L.; Yuan, F.; Yu, Y.; Du, S.; Wang, J.; Xiao, T.; Song, W.; Zhang, Y.; Liu, P.; An, R.; Wang, P.; Wang, Y.; Yang, S.; Niu, X.; Zhang, Y.; Gu, Q.; Shao, F.; Hu, Y.; Yin, W.; Zheng, A.; Wang, Y.; Qin, C.; Jin, R.; Xiao, J.; Xie, X. S. Rational Identification of Potent and Broad Sarbecovirus-Neutralizing Antibody Cocktails from SARS Convalescents. Cell Rep. 2022, 41, 111845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yisimayi, A.; Song, W.; Wang, J.; Jian, F.; Yu, Y.; Chen, X.; Xu, Y.; Yang, S.; Niu, X.; Xiao, T.; Wang, J.; Zhao, L.; Sun, H.; An, R.; Zhang, N.; Wang, Y.; Wang, P.; Yu, L.; Lv, Z.; Gu, Q.; Shao, F.; Jin, R.; Shen, Z.; Xie, X. S.; Wang, Y.; Cao, Y. Repeated Omicron Exposures Override Ancestral SARS-CoV-2 Immune Imprinting. Nature 2024, 625, 148–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jian, F.; Wec, A. Z.; Feng, L.; Yu, Y.; Wang, L.; Wang, P.; Yu, L.; Wang, J.; Hou, J.; Berrueta, D. M.; Lee, D.; Speidel, T.; Ma, L.; Kim, T.; Yisimayi, A.; Song, W.; Wang, J.; Liu, L.; Yang, S.; Niu, X.; Xiao, T.; An, R.; Wang, Y.; Shao, F.; Wang, Y.; Pecetta, S.; Wang, X.; Walker, L. M.; Cao, Y. Viral Evolution Prediction Identifies Broadly Neutralizing Antibodies to Existing and Prospective SARS-CoV-2 Variants. Nat Microbiol 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Starr, T. N.; Czudnochowski, N.; Liu, Z.; Zatta, F.; Park, Y.-J.; Addetia, A.; Pinto, D.; Beltramello, M.; Hernandez, P.; Greaney, A. J.; Marzi, R.; Glass, W. G.; Zhang, I.; Dingens, A. S.; Bowen, J. E.; Tortorici, M. A.; Walls, A. C.; Wojcechowskyj, J. A.; De Marco, A.; Rosen, L. E.; Zhou, J.; Montiel-Ruiz, M.; Kaiser, H.; Dillen, J. R.; Tucker, H.; Bassi, J.; Silacci-Fregni, C.; Housley, M. P.; di Iulio, J.; Lombardo, G.; Agostini, M.; Sprugasci, N.; Culap, K.; Jaconi, S.; Meury, M.; Dellota Jr, E.; Abdelnabi, R.; Foo, S.-Y. C.; Cameroni, E.; Stumpf, S.; Croll, T. I.; Nix, J. C.; Havenar-Daughton, C.; Piccoli, L.; Benigni, F.; Neyts, J.; Telenti, A.; Lempp, F. A.; Pizzuto, M. S.; Chodera, J. D.; Hebner, C. M.; Virgin, H. W.; Whelan, S. P. J.; Veesler, D.; Corti, D.; Bloom, J. D.; Snell, G. SARS-CoV-2 RBD Antibodies That Maximize Breadth and Resistance to Escape. Nature 2021, 597, 97–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, L.; Wang, Y.; Liu, Y.; Xing, X.; Li, C.; Wang, X.; Shi, J.; Ma, W.; Li, J.; Chen, Y.; Qiao, R.; Zhao, X.; Tian, S.; Gao, M.; Wen, S.; Xue, Y.; Qiu, T.; Yu, H.; Guan, Y.; Chu, H.; Sun, L.; Wang, P. Potent and Broadly Neutralizing Antibodies against Sarbecoviruses Elicited by Single Ancestral SARS-CoV-2 Infection. Commun Biol. 2025, 8, 378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, S.; Alshahrani, M.; Gupta, G.; Tao, P.; Verkhivker, G. Markov State Models and Perturbation-Based Approaches Reveal Distinct Dynamic Signatures and Hidden Allosteric Pockets in the Emerging SARS-Cov-2 Spike Omicron Variant Complexes with the Host Receptor: The Interplay of Dynamics and Convergent Evolution Modulates Allostery and Functional Mechanisms. J. Chem. Inf. Model. 2023, 63, 5272–5296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raisinghani, N.; Alshahrani, M.; Gupta, G.; Xiao, S.; Tao, P.; Verkhivker, G. AlphaFold2 Predictions of Conformational Ensembles and Atomistic Simulations of the SARS-CoV-2 Spike XBB Lineages Reveal Epistatic Couplings between Convergent Mutational Hotspots That Control ACE2 Affinity. J. Phys. Chem. B. 2024, 128, 4696–4715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raisinghani, N.; Alshahrani, M.; Gupta, G.; Verkhivker, G. Ensemble-Based Mutational Profiling and Network Analysis of the SARS-CoV-2 Spike Omicron XBB Lineages for Interactions with the ACE2 Receptor and Antibodies: Cooperation of Binding Hotspots in Mediating Epistatic Couplings Underlies Binding Mechanism and Immune Escape. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 4281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raisinghani, N.; Alshahrani, M.; Gupta, G.; Verkhivker, G. AlphaFold2 Modeling and Molecular Dynamics Simulations of the Conformational Ensembles for the SARS-CoV-2 Spike Omicron JN.1, KP.2 and KP.3 Variants: Mutational Profiling of Binding Energetics Reveals Epistatic Drivers of the ACE2 Affinity and Escape Hotspots of Antibody Resistance. Viruses, 1458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verkhivker, G.; Alshahrani, M.; Gupta, G. Balancing Functional Tradeoffs between Protein Stability and ACE2 Binding in the SARS-CoV-2 Omicron BA.2, BA.2.75 and XBB Lineages: Dynamics-Based Network Models Reveal Epistatic Effects Modulating Compensatory Dynamic and Energetic Changes. Viruses 2023, 15, 1143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Verkhivker, G.; Agajanian, S.; Kassab, R.; Krishnan, K. Integrating Conformational Dynamics and Perturbation-Based Network Modeling for Mutational Profiling of Binding and Allostery in the SARS-CoV-2 Spike Variant Complexes with Antibodies: Balancing Local and Global Determinants of Mutational Escape Mechanisms. Biomolecules 2022, 12, 964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alshahrani, M.; Parikh, V.; Foley, B.; Raisinghani, N.; Verkhivker, G. Quantitative Characterization and Prediction of the Binding Determinants and Immune Escape Hotspots for Groups of Broadly Neutralizing Antibodies Against Omicron Variants: Atomistic Modeling of the SARS-CoV-2 Spike Complexes with Antibodies. Biomolecules 2025, 15, 249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alshahrani, M.; Parikh, V.; Foley, B.; Verkhivker, G. Integrative Computational Modeling of Distinct Binding Mechanisms for Broadly Neutralizing Antibodies Targeting SARS-CoV-2 Spike Omicron Variants: Balance of Evolutionary and Dynamic Adaptability in Shaping Molecular Determinants of Immune Escape. Viruses 2025, 17, 741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, H.; Guo, H.; Wang, A.; Cao, L.; Fan, Q.; Jiang, J.; Wang, M.; Lin, L.; Ge, X.; Wang, H.; Zhang, R.; Liao, M.; Yan, R.; Ju, B.; Zhang, Z. Structural Basis for the Evolution and Antibody Evasion of SARS-CoV-2 BA.2.86 and JN.1 Subvariants. Nat Commun. 2024, 15, 7715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yajima, H.; Nomai, T.; Okumura, K.; Maenaka, K.; Ito, J.; Hashiguchi, T.; Sato, K.; Matsuno, K.; Nao, N.; Sawa, H.; Mizuma, K.; Li, J.; Kida, I.; Mimura, Y.; Ohari, Y.; Tanaka, S.; Tsuda, M.; Wang, L.; Oda, Y.; Ferdous, Z.; Shishido, K.; Mohri, H.; Iida, M.; Fukuhara, T.; Tamura, T.; Suzuki, R.; Suzuki, S.; Tsujino, S.; Ito, H.; Kaku, Y.; Misawa, N.; Plianchaisuk, A.; Guo, Z.; Hinay, A. A., Jr.; Usui, K.; Saikruang, W.; Lytras, S.; Uriu, K.; Yoshimura, R.; Kawakubo, S.; Nishumura, L.; Kosugi, Y.; Fujita, S.; M. Tolentino, J. E.; Chen, L.; Pan, L.; Li, W.; Yo, M. S.; Horinaka, K.; Suganami, M.; Chiba, M.; Yasuda, K.; Iida, K.; Strange, A. P.; Ohsumi, N.; Tanaka, S.; Ogawa, E.; Fukuda, T.; Osujo, R.; Yoshimura, K.; Sadamas, K.; Nagashima, M.; Asakura, H.; Yoshida, I.; Nakagawa, S.; Takayama, K.; Hashimoto, R.; Deguchi, S.; Watanabe, Y.; Nakata, Y.; Futatsusako, H.; Sakamoto, A.; Yasuhara, N.; Suzuki, T.; Kimura, K.; Sasaki, J.; Nakajima, Y.; Irie, T.; Kawabata, R.; Sasaki-Tabata, K.; Ikeda, T.; Nasser, H.; Shimizu, R.; Begum, M. M.; Jonathan, M.; Mugita, Y.; Leong, S.; Takahashi, O.; Ueno, T.; Motozono, C.; Toyoda, M.; Saito, A.; Kosaka, A.; Kawano, M.; Matsubara, N.; Nishiuchi, T.; Zahradnik, J.; Andrikopoulos, P.; Padilla-Blanco, M.; Konar, A. Molecular and Structural Insights into SARS-CoV-2 Evolution: From BA.2 to XBB Subvariants. mBio. 2024, 15, e0322023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xue, S.; Han, Y.; Wu, F.; Wang, Q. Mutations in the SARS-CoV-2 Spike Receptor Binding Domain and Their Delicate Balance between ACE2 Affinity and Antibody Evasion. Protein Cell. 2024, 15, 403–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tulsian, N. K.; Palur, R. V.; Qian, X.; Gu, Y.; D/O Shunmuganathan, B.; Samsudin, F.; Wong, Y. H.; Lin, J.; Purushotorman, K.; Kozma, M. M.; Wang, B.; Lescar, J.; Wang, C.-I.; Gupta, R. K.; Bond, P. J.; MacAry, P. A. Defining Neutralization and Allostery by Antibodies against COVID-19 Variants. Nat Commun. 2023, 14, 6967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yuan, M.; Liu, H.; Wu, N. C.; Lee, C.-C. D.; Zhu, X.; Zhao, F.; Huang, D.; Yu, W.; Hua, Y.; Tien, H.; Rogers, T. F.; Landais, E.; Sok, D.; Jardine, J. G.; Burton, D. R.; Wilson, I. A. Structural Basis of a Shared Antibody Response to SARS-CoV-2. Science 2020, 369, 1119–1123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huo, J.; Zhao, Y.; Ren, J.; Zhou, D.; Duyvesteyn, H. M. E.; Ginn, H. M.; Carrique, L.; Malinauskas, T.; Ruza, R. R.; Shah, P. N. M.; Tan, T. K.; Rijal, P.; Coombes, N.; Bewley, K. R.; Tree, J. A.; Radecke, J.; Paterson, N. G.; Supasa, P.; Mongkolsapaya, J.; Screaton, G. R.; Carroll, M.; Townsend, A.; Fry, E. E.; Owens, R. J.; Stuart, D. I. Neutralization of SARS-CoV-2 by Destruction of the Prefusion Spike. Cell Host Microbe, 2020 , 28, 445- 454.e6. [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; Wu, N. C.; Yuan, M.; Bangaru, S.; Torres, J. L.; Caniels, T. G.; van Schooten, J.; Zhu, X.; Lee, C.-C. D.; Brouwer, P. J. M.; van Gils, M. J.; Sanders, R. W.; Ward, A. B.; Wilson, I. A. Cross-Neutralization of a SARS-CoV-2 Antibody to a Functionally Conserved Site Is Mediated by Avidity. Immunity. 2020, 53, 1272–1280.e5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tortorici, M. A.; Czudnochowski, N.; Starr, T. N.; Marzi, R.; Walls, A. C.; Zatta, F.; Bowen, J. E.; Jaconi, S.; Di Iulio, J.; Wang, Z.; De Marco, A.; Zepeda, S. K.; Pinto, D.; Liu, Z.; Beltramello, M.; Bartha, I.; Housley, M. P.; Lempp, F. A.; Rosen, L. E.; Dellota, E., Jr; Kaiser, H.; Montiel-Ruiz, M.; Zhou, J.; Addetia, A.; Guarino, B.; Culap, K.; Sprugasci, N.; Saliba, C.; Vetti, E.; Giacchetto-Sasselli, I.; Fregni, C. S.; Abdelnabi, R.; Foo, S.-Y. C.; Havenar-Daughton, C.; Schmid, M. A.; Benigni, F.; Cameroni, E.; Neyts, J.; Telenti, A.; Virgin, H. W.; Whelan, S. P. J.; Snell, G.; Bloom, J. D.; Corti, D.; Veesler, D.; Pizzuto, M. S. Broad Sarbecovirus Neutralization by a Human Monoclonal Antibody. Nature 2021, 597, 103–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hastie, K. M.; Li, H.; Bedinger, D.; Schendel, S. L.; Dennison, S. M.; Li, K.; Rayaprolu, V.; Yu, X.; Mann, C.; Zandonatti, M.; Diaz Avalos, R.; Zyla, D.; Buck, T.; Hui, S.; Shaffer, K.; Hariharan, C.; Yin, J.; Olmedillas, E.; Enriquez, A.; Parekh, D.; Abraha, M.; Feeney, E.; Horn, G. Q.; Aldon, Y.; Ali, H.; Aracic, S.; Cobb, R. R.; Federman, R. S.; Fernandez, J. M.; Glanville, J.; Green, R.; Grigoryan, G.; Lujan Hernandez, A. G.; Ho, D. D.; Huang, K.-Y. A.; Ingraham, J.; Jiang, W.; Kellam, P.; Kim, C.; Kim, M.; Kim, H. M.; Kong, C.; Krebs, S. J.; Lan, F.; Lang, G.; Lee, S.; Leung, C. L.; Liu, J.; Lu, Y.; MacCamy, A.; McGuire, A. T.; Palser, A. L.; Rabbitts, T. H.; Rikhtegaran Tehrani, Z.; Sajadi, M. M.; Sanders, R. W.; Sato, A. K.; Schweizer, L.; Seo, J.; Shen, B.; Snitselaar, J. L.; Stamatatos, L.; Tan, Y.; Tomic, M. T.; van Gils, M. J.; Youssef, S.; Yu, J.; Yuan, T. Z.; Zhang, Q.; Peters, B.; Tomaras, G. D.; Germann, T.; Saphire, E. O. Defining Variant-Resistant Epitopes Targeted by SARS-CoV-2 Antibodies: A Global Consortium Study. Science 2021, 374, 472–478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rose, P. W.; Prlic, A.; Altunkaya, A.; Bi, C.; Bradley, A. R.; Christie, C. H.; Costanzo, L. D.; Duarte, J. M.; Dutta, S.; Feng, Z.; Green, R. K.; Goodsell, D. S.; Hudson, B.; Kalro, T.; Lowe, R.; Peisach, E.; Randle, C.; Rose, A. S.; Shao, C.; Tao, Y. P.; Valasatava, Y.; Voigt, M.; Westbrook, J. D.; Woo, J.; Yang, H.; Young, J. Y.; Zardecki, C.; Berman, H. M.; Burley, S. K. The RCSB protein data bank: integrative view of protein, gene and 3D structural information. Nucleic Acids Res. 2017, 45, D271–D281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kmiecik, S.; Kolinski, A. Characterization of protein-folding pathways by reduced-space modeling. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2007, 104, 12330–12335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kmiecik, S.; Gront, D.; Kolinski, M.; Wieteska, L.; Dawid, A.E.; Kolinski, A. Coarse-grained protein models and their applications. Chem. Rev. 2016, 116, 7898–7936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kmiecik, S.; Kouza, M.; Badaczewska-Dawid, A.E.; Kloczkowski, A.; Kolinski, A. Modeling of protein structural flexibility and large-scale dynamics: Coarse-grained simulations and elastic network models. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2018, 19, 3496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ciemny, M.P.; Badaczewska-Dawid, A.E.; Pikuzinska, M.; Kolinski, A.; Kmiecik, S. Modeling of disordered protein structures using monte carlo simulations and knowledge-based statistical force fields. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019, 20, 606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kurcinski, M.; Oleniecki, T.; Ciemny, M.P.; Kuriata, A.; Kolinski, A.; Kmiecik, S. CABS-flex standalone: A simulation environment for fast modeling of protein flexibility. Bioinformatics 2019, 35, 694–695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Badaczewska-Dawid, A. E.; Kolinski, A.; Kmiecik, S. Protocols for fast simulations of protein structure flexibility using CABS-Flex and SURPASS. Methods Mol. Biol. 2020, 2165, 337–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marti-Renom, M. A.; Stuart, A. C.; Fiser, A.; Sanchez, R.; Melo, F.; Sali, A. Comparative protein structure modeling of genes and genomes. Annu. Rev. Biophys. Biomol. Struct. 2000, 29, 291–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fernandez-Fuentes, N.; Zhai, J.; Fiser, A. ArchPRED: A template based loop structure prediction server. Nucleic Acids Res. 2006, 34, W173–W176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Krivov, V.P., B. F.; Shapovalov, M.V.; Dunbrack, R.L., Jr. Improved prediction of protein side-chain conformations with SCWRL4. Proteins, 1002. [Google Scholar]

- Søndergaard C., R.; Olsson M., H.; Rostkowski, M.; Jensen J., H. Improved treatment of ligands and coupling effects in empirical calculation and rationalization of pKa values. J. Chem. Theory Comput. 2011, 7, 2284–2295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olsson M., H.; Søndergaard C., R.; Rostkowski, M.; Jensen J., H. PROPKA3: consistent treatment of internal and surface residues in empirical pKa predictions. J. Chem. Theory Comput. 2011, 7, 525–537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.; Cheng, X.; Swails, J. M.; Yeom, M. S.; Eastman, P. K.; Lemkul, J. A.; Wei, S.; Buckner, J.; Jeong, J. C.; Qi, Y.; Jo, S.; Pande, V. S.; Case, D. A.; Brooks, C. L., III; MacKerell, A. D., Jr.; Klauda, J. B.; Im, W. CHARMM-GUI Input Generator for NAMD, GROMACS, AMBER, OpenMM, and CHARMM/OpenMM Simulations Using the CHARMM36 Additive Force Field. J Chem Theory Comput. 2016, 12, 405–413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, S.-J.; Lee, J.; Qi, Y.; Kern, N. R.; Lee, H. S.; Jo, S.; Joung, I.; Joo, K.; Lee, J.; Im, W. CHARMM-GUI Glycan Modeler for Modeling and Simulation of Carbohydrates and Glycoconjugates. Glycobiology. 2019, 29, 320–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phillips, J.C.; Hardy, D.J.; Maia, J.D.C.; Stone, J.E.; Ribeiro, J.V.; Bernardi, R.C.; Buch, R.; Fiorin, G.; Hénin, J.; Jiang, W.; et al. Scalable Molecular Dynamics on CPU and GPU Architectures with NAMD. J. Chem. Phys. 2020, 153, 044130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, J.; Rauscher, S.; Nawrocki, G.; Ran, T.; Feig, M.; de Groot, B.L.; Grubmüller, H.; MacKerell, A.D., Jr. CHARMM36m: An improved force field for folded and intrinsically disordered proteins. Nat. Methods 2017, 14, 71–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jorgensen, W.L.; Chandrasekhar, J.; Madura, J.D.; Impey, R.W.; Klein, M.L. Comparison of Simple Potential Functions for Simulating Liquid Water. J. Chem. Phys. 1983, 79, 926–935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ross, G.A.; Rustenburg, A.S.; Grinaway, P.B.; Fass, J.; Chodera, J.D. Biomolecular Simulations under Realistic Macroscopic Salt Conditions. J. Phys. Chem. B 2018, 122, 5466–5486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hoover, W. G. Canonical Dynamics: Equilibrium Phase-Space Distributions. Phys. Rev. A 1985, 31, 1695–1697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Parrinello, M.; Rahman, A. Polymorphic transitions in single crystals: a new molecular dynamics method. J. Appl. Phys. 1981, 52, 7182–7190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Pierro, M.; Elber, R.; Leimkuhler, B. A Stochastic Algorithm for the Isobaric-Isothermal Ensemble with Ewald Summations for All Long Range Forces. J. Chem. Theory Comput. 2015, 11, 5624–5637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martyna, G.J.; Tobias, D.J.; Klein, M.L. Constant pressure molecular dynamics algorithms. J. Chem. Phys. 1994, 101, 4177–4189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feller, S.E.; Zhang, Y.; Pastor, R.W.; Brooks, B.R. Constant pressure molecular dynamics simulation: The Langevin piston method. J. Chem. Phys. 1995, 103, 4613–4621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dehouck, Y.; Kwasigroch, J. M.; Rooman, M.; Gilis, D. BeAtMuSiC: Prediction of changes in protein-protein binding affinity on mutations. Nucleic Acids Res. 2013, 41, W333–W339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dehouck, Y.; Gilis, D.; Rooman, M. A new generation of statistical potentials for proteins. Biophys. J. 2006, 90, 4010–4017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dehouck, Y.; Grosfils, A.; Folch, B.; Gilis, D.; Bogaerts, P.; Rooman, M. Fast and accurate predictions of protein stability changes upon mutations using statistical potentials and neural networks:PoPMuSiC-2.0. Bioinformatics 2009, 25, 2537–2543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pucci, F.; Bernaerts, K. V.; Kwasigroch, J. M.; Rooman, M. Quantification of Biases in Predictions of Protein Stability Changes upon Mutations. Bioinformatics 2018, 34, 3659–3665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsishyn, M.; Pucci, F.; Rooman, M. Quantification of Biases in Predictions of Protein–Protein Binding Affinity Changes upon Mutations. Brief Bioinform. 2023, 25, bbad491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Srinivasan, J.; Cheatham, T. E.; Cieplak, P.; Kollman, P. A.; Case, D. A. Continuum Solvent Studies of the Stability of DNA, RNA, and Phosphoramidate−DNA Helices. J. Amer. Chem. Soc. 1998, 120, 9401–9409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kollman, P. A.; Massova, I.; Reyes, C.; Kuhn, B.; Huo, S.; Chong, L.; Lee, M.; Lee, T.; Duan, Y.; Wang, W.; Donini, O.; Cieplak, P.; Srinivasan, J.; Case, D. A.; Cheatham, T. E. Calculating Structures and Free Energies of Complex Molecules: Combining Molecular Mechanics and Continuum Models. Acc. Chem. Res. 2000, 33, 889–897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hou, T.; Wang, J.; Li, Y.; Wang, W. Assessing the Performance of the MM/PBSA and MM/GBSA Methods. 1. The Accuracy of Binding Free Energy Calculations Based on Molecular Dynamics Simulations. J. Chem. Inf. Model. 2011, 51, 69–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weng, G.; Wang, E.; Wang, Z.; Liu, H.; Zhu, F.; Li, D.; Hou, T. HawkDock: A Web Server to Predict and Analyze the Protein–Protein Complex Based on Computational Docking and MM/GBSA. Nucleic Acids Res. 2019, 47, W322–W330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mongan, J.; Simmerling, C.; McCammon, J. A.; Case, D. A.; Onufriev, A. Generalized Born Model with a Simple, Robust Molecular Volume Correction. J Chem Theory Comput. 2007, 3, 156–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, A. H.; Zhan, C.-G. Generalized Methodology for the Quick Prediction of Variant SARS-CoV-2 Spike Protein Binding Affinities with Human Angiotensin-Converting Enzyme II. J. Phys. Chem. B. 2022, 126, 2353–2360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, H.; Duan, L.; Chen, F.; Liu, H.; Wang, Z.; Pan, P.; Zhu, F.; Zhang, J. Z. H.; Hou, T. Assessing the Performance of MM/PBSA and MM/GBSA Methods. 7. Entropy Effects on the Performance of End-Point Binding Free Energy Calculation Approaches. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2018, 20, 14450–14460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, B. R., III; McGee, T. D., Jr.; Swails, J. M.; Homeyer, N.; Gohlke, H.; Roitberg, A. E. MMPBSA.Py: An Efficient Program for End-State Free Energy Calculations. J Chem Theory Comput. 2012, 8, 3314–3321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Valdés-Tresanco, M. S.; Valdés-Tresanco, M. E.; Valiente, P. A.; Moreno, E. gmx_MMPBSA: A New Tool to Perform End-State Free Energy Calculations with GROMACS. J Chem Theory Comput. 2021, 17, 6281–6291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brinda, K. V.; Vishveshwara, S. A Network Representation of Protein Structures: Implications for Protein Stability. Biophys. J. 2005, 89, 4159–4170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vijayabaskar, M. S.; Vishveshwara, S. Interaction Energy Based Protein Structure Networks. Biophys. J. 2010, 99, 3704–3715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piovesan, D.; Minervini, G.; Tosatto, S. C. The RING 2.0 Web Server for High Quality Residue Interaction Networks. Nucleic Acids Res. 2016, 44, W367–W374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clementel, D.; Del Conte, A.; Monzon, A. M.; Camagni, G. F.; Minervini, G.; Piovesan, D.; Tosatto, S. C. E. RING 3.0: Fast Generation of Probabilistic Residue Interaction Networks from Structural Ensembles. Nucleic Acids Res. 2022, 50, W651–W656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Del Conte, A.; Camagni, G. F.; Clementel, D.; Minervini, G.; Monzon, A. M.; Ferrari, C.; Piovesan, D.; Tosatto, S. C. E. RING 4.0: Faster Residue Interaction Networks with Novel Interaction Types across over 35,000 Different Chemical Structures. Nucleic Acids Res. 2024, 52, W306–W312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hagberg, A. A.; Schult, D. A.; Swart, P. J. Exploring Network Structure, Dynamics, and Function Using NetworkX. In Proceedings of the 7th Python in Science Conference (SciPy2008); Varoquaux, G., Vaught, T., Millman, J., Eds.; Pasadena; 2008; pp. 11–15. [Google Scholar]

- Shannon, P.; Markiel, A.; Ozier, O.; Baliga, N. S.; Wang, J. T.; Ramage, D.; Amin, N.; Schwikowski, B.; Ideker, T. Cytoscape: A Software Environment for Integrated Models of Biomolecular Interaction Networks. Genome Res 2003, 13, 2498–2504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saito, R.; Smoot, M. E.; Ono, K.; Ruscheinski, J.; Wang, P.-L.; Lotia, S.; Pico, A. R.; Bader, G. D.; Ideker, T. A Travel Guide to Cytoscape Plugins. Nat Methods 2012, 9, 1069–1076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ono, K.; Fong, D.; Gao, C.; Churas, C.; Pillich, R.; Lenkiewicz, J.; Pratt, D.; Pico, A. R.; Hanspers, K.; Xin, Y.; Morris, J.; Kucera, M.; Franz, M.; Lopes, C.; Bader, G.; Ideker, T.; Chen, J. Cytoscape Web: Bringing Network Biology to the Browser. Nucleic Acids Research 2025, 53, W203–W212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dejnirattisai, W.; Zhou, D.; Ginn, H. M.; Duyvesteyn, H. M. E.; Supasa, P.; Case, J. B.; Zhao, Y.; Walter, T. S.; Mentzer, A. J.; Liu, C.; Wang, B.; Paesen, G. C.; Slon-Campos, J.; López-Camacho, C.; Kafai, N. M.; Bailey, A. L.; Chen, R. E.; Ying, B.; Thompson, C.; Bolton, J.; Fyfe, A.; Gupta, S.; Tan, T. K.; Gilbert-Jaramillo, J.; James, W.; Knight, M.; Carroll, M. W.; Skelly, D.; Dold, C.; Peng, Y.; Levin, R.; Dong, T.; Pollard, A. J.; Knight, J. C.; Klenerman, P.; Temperton, N.; Hall, D. R.; Williams, M. A.; Paterson, N. G.; Bertram, F. K. R.; Siebert, C. A.; Clare, D. K.; Howe, A.; Radecke, J.; Song, Y.; Townsend, A. R.; Huang, K.-Y. A.; Fry, E. E.; Mongkolsapaya, J.; Diamond, M. S.; Ren, J.; Stuart, D. I.; Screaton, G. R. The Antigenic Anatomy of SARS-CoV-2 Receptor Binding Domain. Cell, 2183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, D.; Duyvesteyn, H. M. E.; Chen, C.-P.; Huang, C.-G.; Chen, T.-H.; Shih, S.-R.; Lin, Y.-C.; Cheng, C.-Y.; Cheng, S.-H.; Huang, Y.-C.; Lin, T.-Y.; Ma, C.; Huo, J.; Carrique, L.; Malinauskas, T.; Ruza, R. R.; Shah, P. N. M.; Tan, T. K.; Rijal, P.; Donat, R. F.; Godwin, K.; Buttigieg, K. R.; Tree, J. A.; Radecke, J.; Paterson, N. G.; Supasa, P.; Mongkolsapaya, J.; Screaton, G. R.; Carroll, M. W.; Gilbert-Jaramillo, J.; Knight, M. L.; James, W.; Owens, R. J.; Naismith, J. H.; Townsend, A. R.; Fry, E. E.; Zhao, Y.; Ren, J.; Stuart, D. I.; Huang, K.-Y. A. Structural Basis for the Neutralization of SARS-CoV-2 by an Antibody from a Convalescent Patient. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2020, 27, 950–958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Group F1 antibodies | Group F2 antibodies | Group F3 antibodies | |

| Binding Site | Core RBD, cryptic | Partial overlap + ACE2 interface | Further shift toward ACE2 interface |

| ACE2 Competition | No | Partial | Yes |

| Key Interactions | Leu445, Phe486, Tyr505 | R408, 500–508 | D405, R408, V503, G504, Y508 |

| Escape Mutations | 383–386, 390, 391 | 408, 500–508 | 501, 505 |

| RMSF Profile | Stabilized core, flexible 470–490 loop | Moderate flexibility in 450–470 | Reduced flexibility in 470–490 |

| Neutralization Mechanism | Allosteric | Partial steric hindrance | Direct competition with ACE2 |

| Feature | Group F1 | Group F2 | Group F3 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Network Localization | Broad, diffuse | Intermediate, partially localized | Highly localized |

| ACE2 Coupling | Weak, indirect | Moderate, hybrid | Strong, direct |

| Key Residues | Core β-sheet (e.g., 355–380, 431, 436) | Core + emerging ACE2 sites (T376, R408, V503) | ACE2-overlapping residues (D405, R408, G504, Y508) |

| Escape Vulnerability | Low | Moderate | Moderate |

| Neutralization Mechanism | Indirect allostery | Hybrid (dynamic + partial steric) | Direct ACE2 competition + allosteric stabilization |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).