Submitted:

08 June 2025

Posted:

09 June 2025

You are already at the latest version

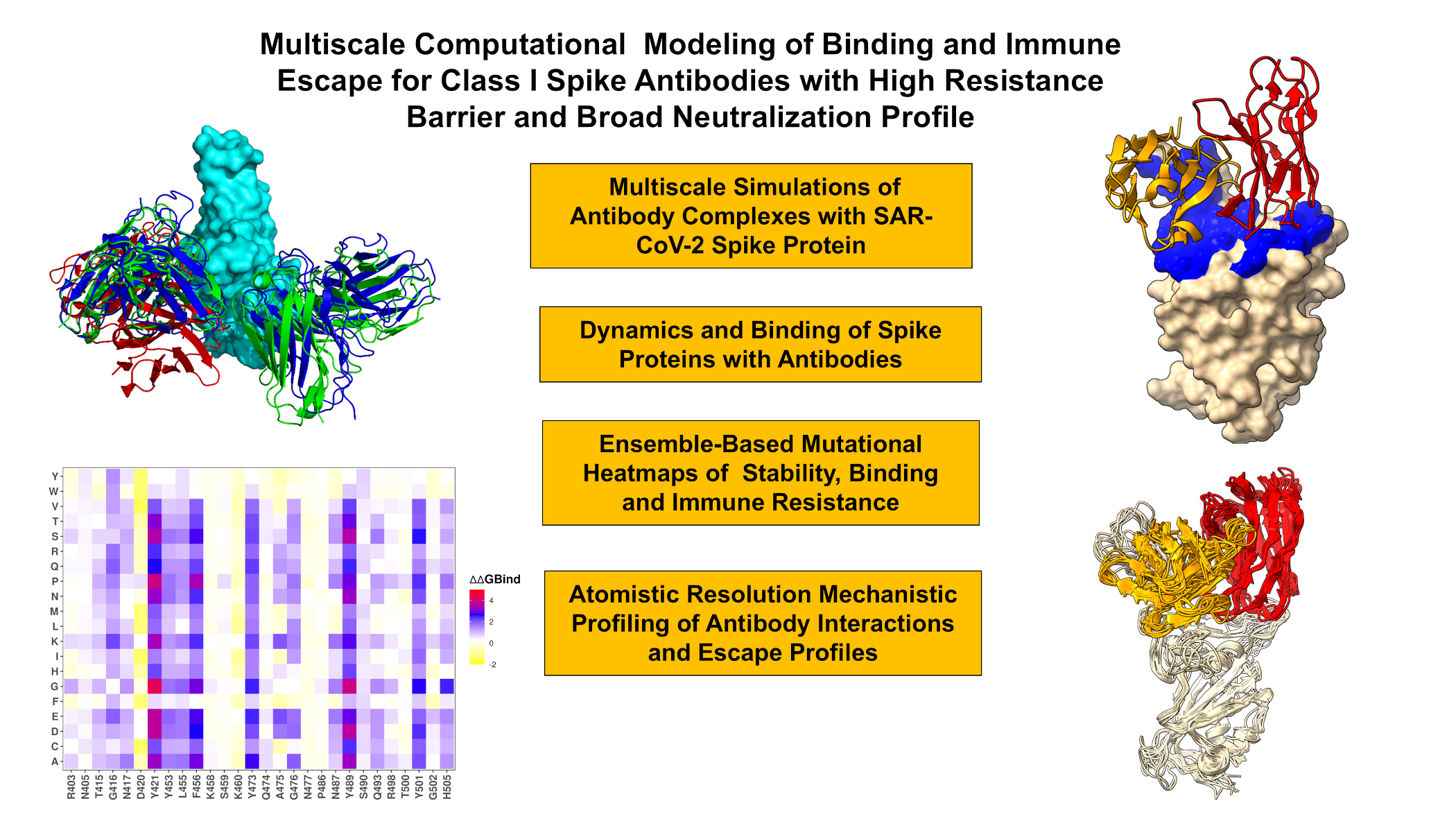

Abstract

Keywords:

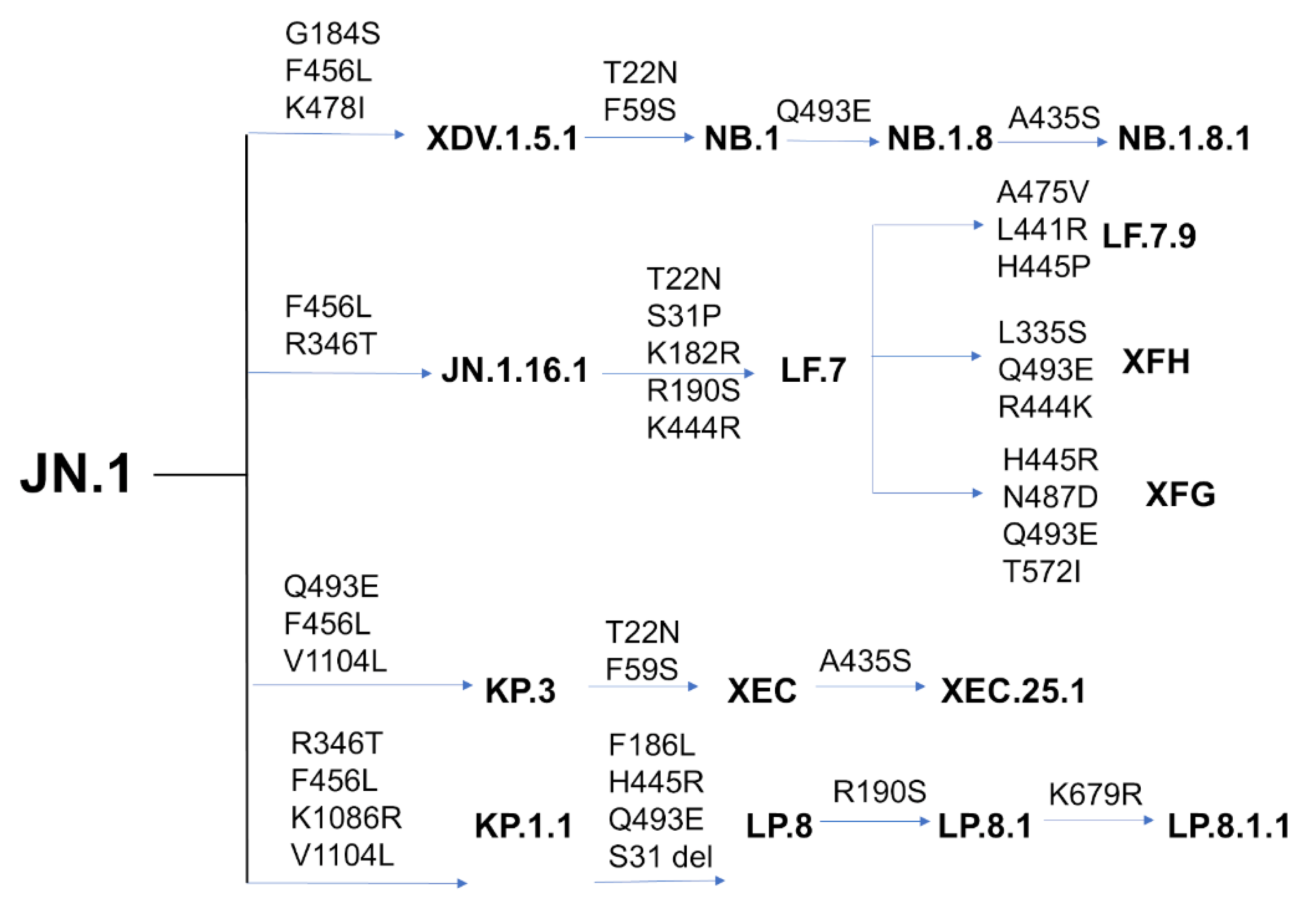

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Coarse-Grained Molecular Simulations and Atomistic Reconstruction of Equilibrium Ensembles

2.2. Binding Free Energy Computations: Mutational Scanning Profiling and Analysis

2.3. Binding Free Energy Computations

3. Results

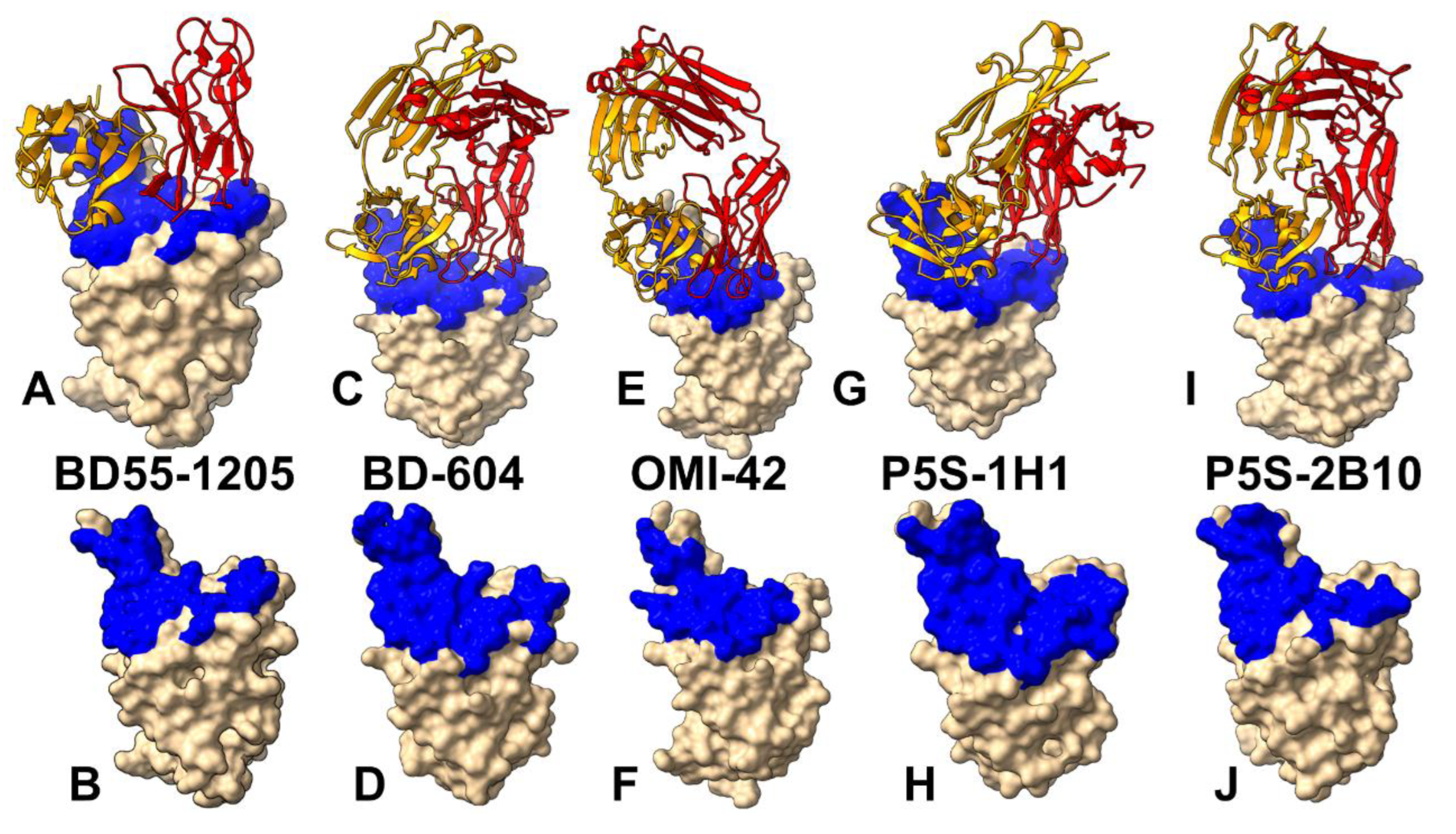

3.1. Structural Analysis of the RBD Complexes

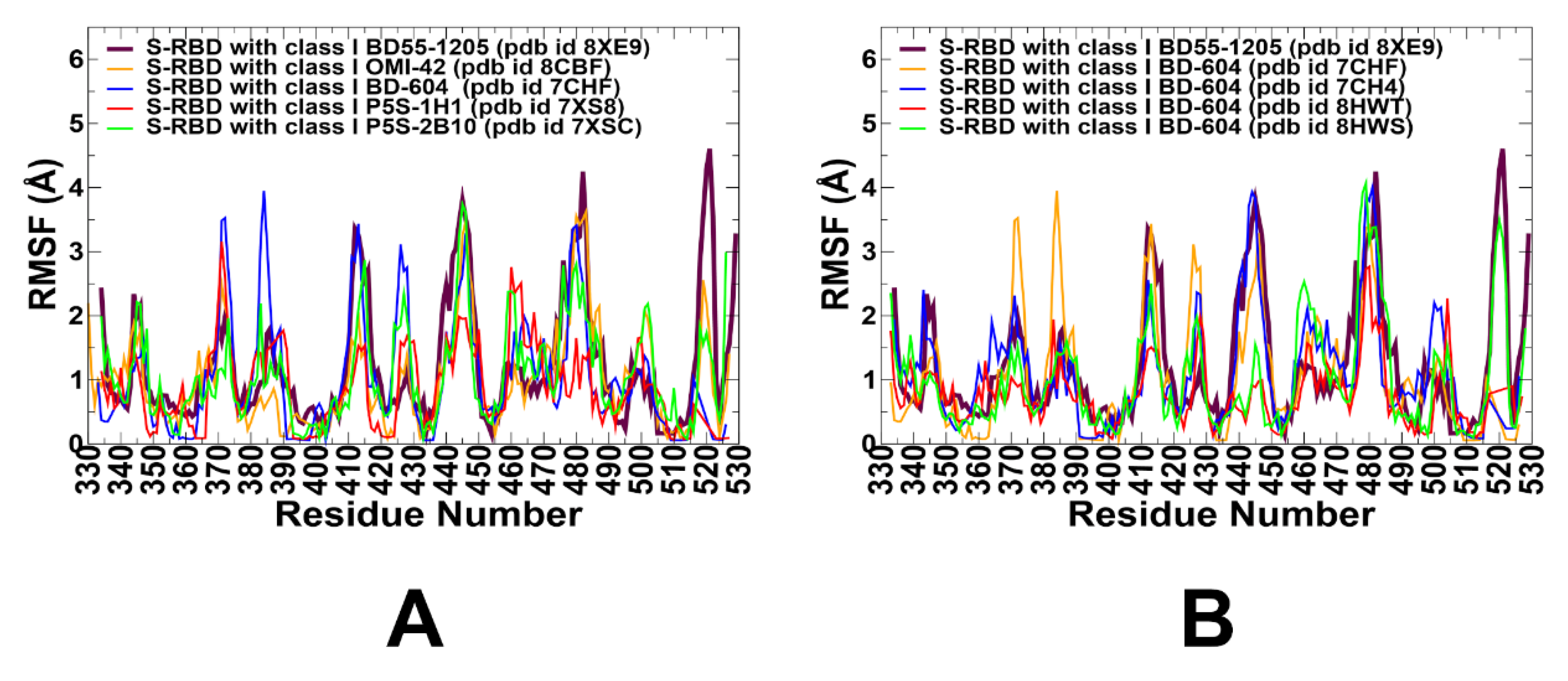

3.2. Coarse-Grained Simulations and Atomistic Reconstruction of the Conformational Ensembles for RBD Complexes with Class I Antibodies

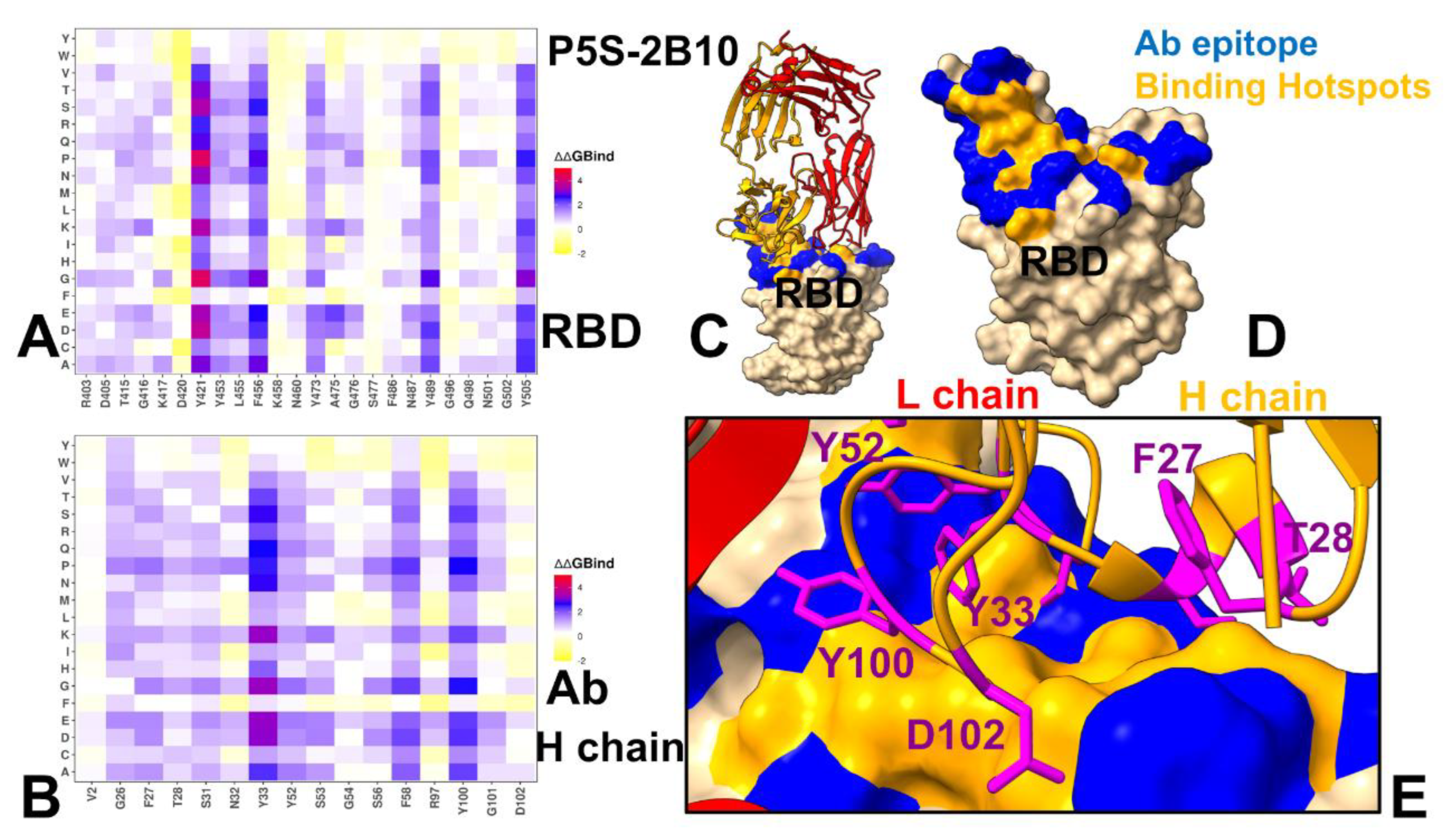

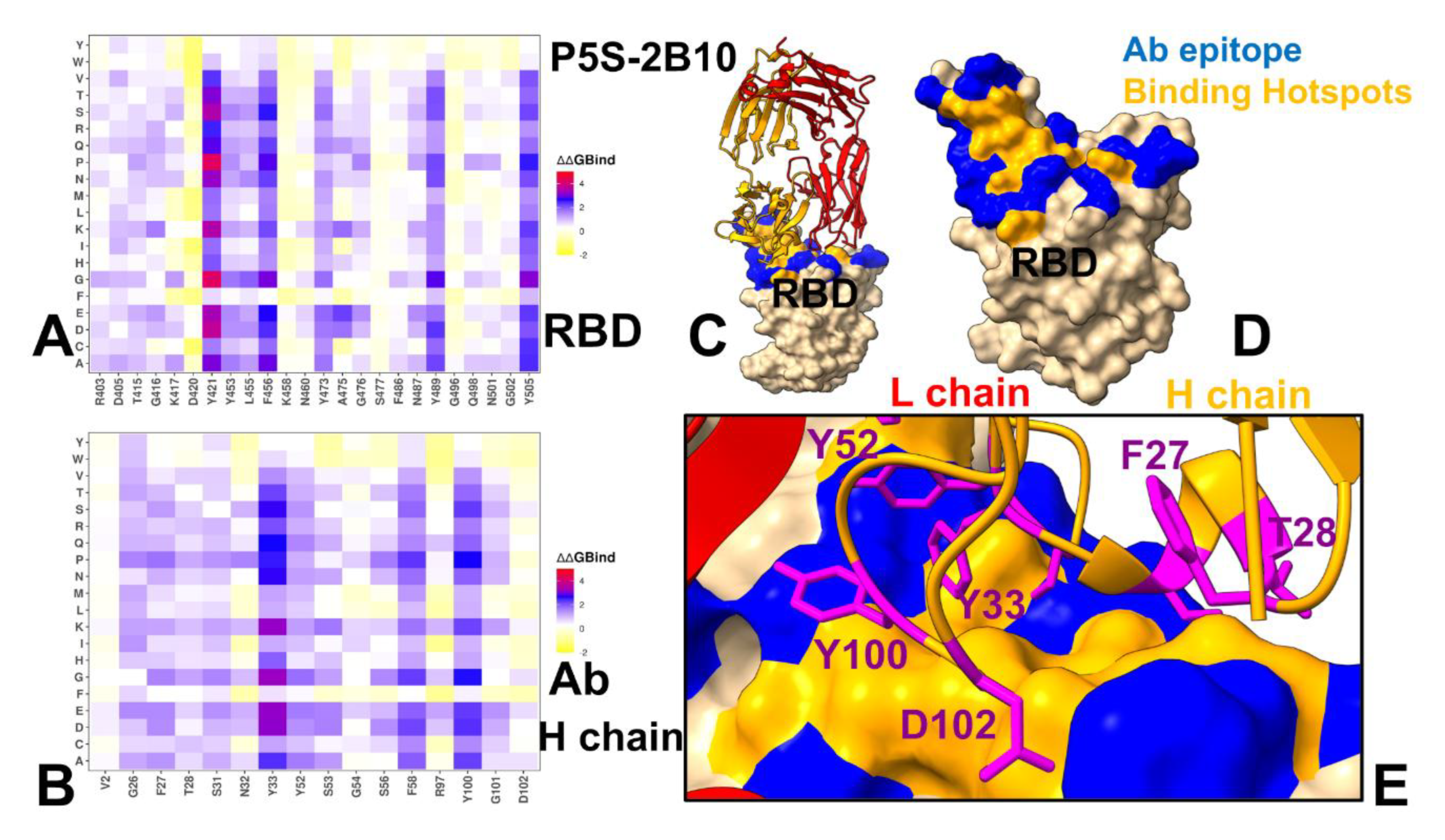

3.3. Mutational Profiling of Antibody-RBD Binding Interactions Interfaces Reveals Molecular Determinants of Immune Sensitivity and Emergence of Convergent Escape Hotspots

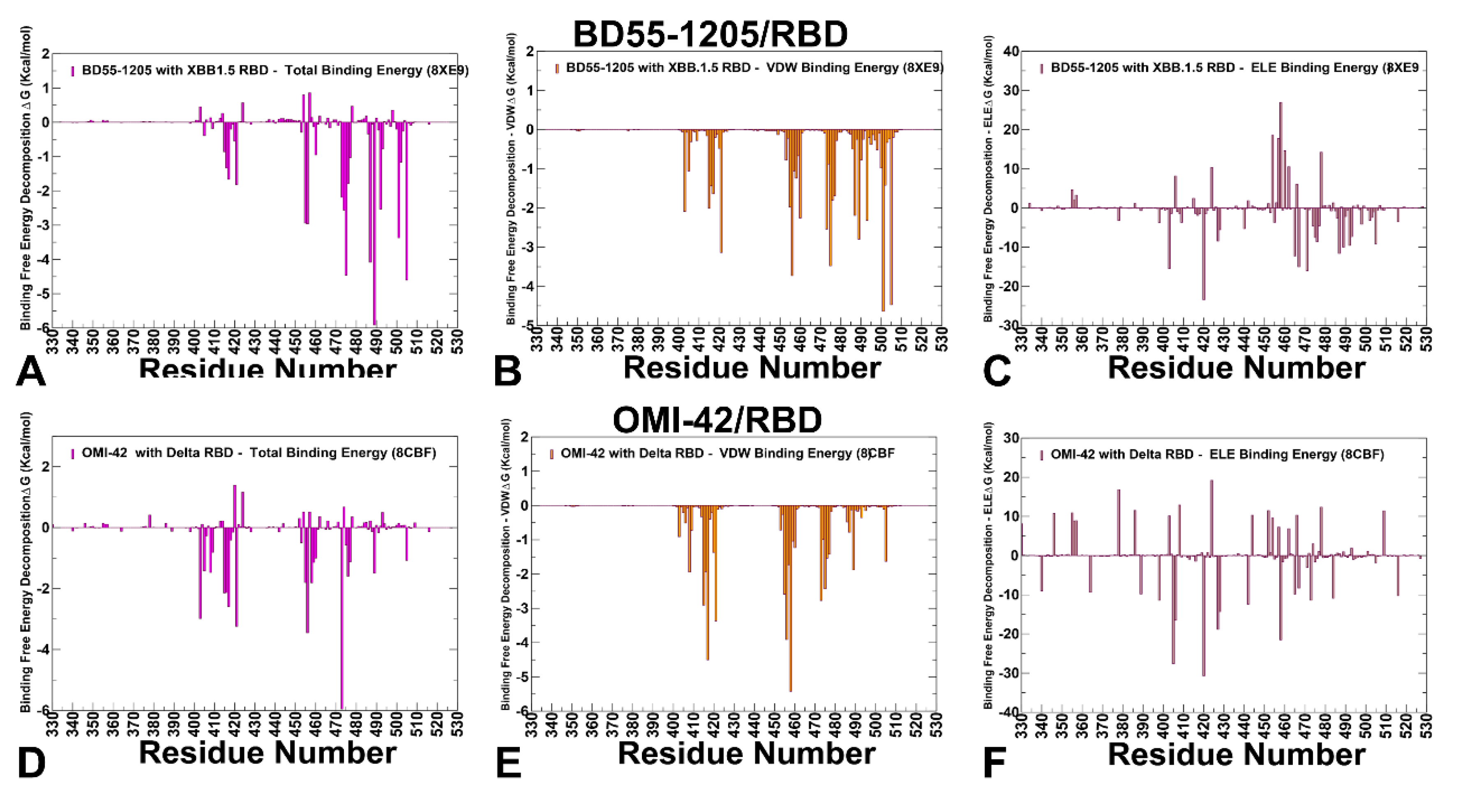

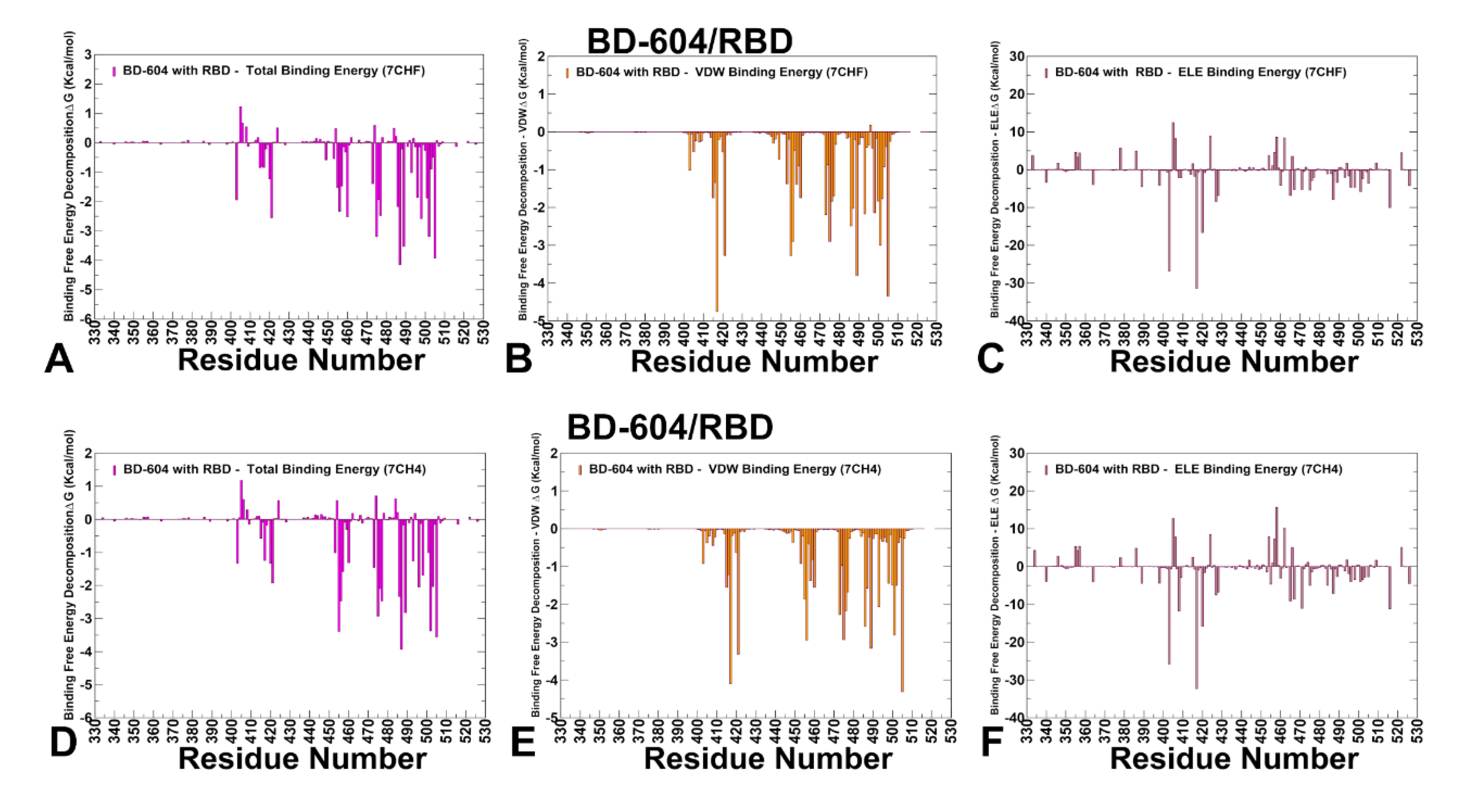

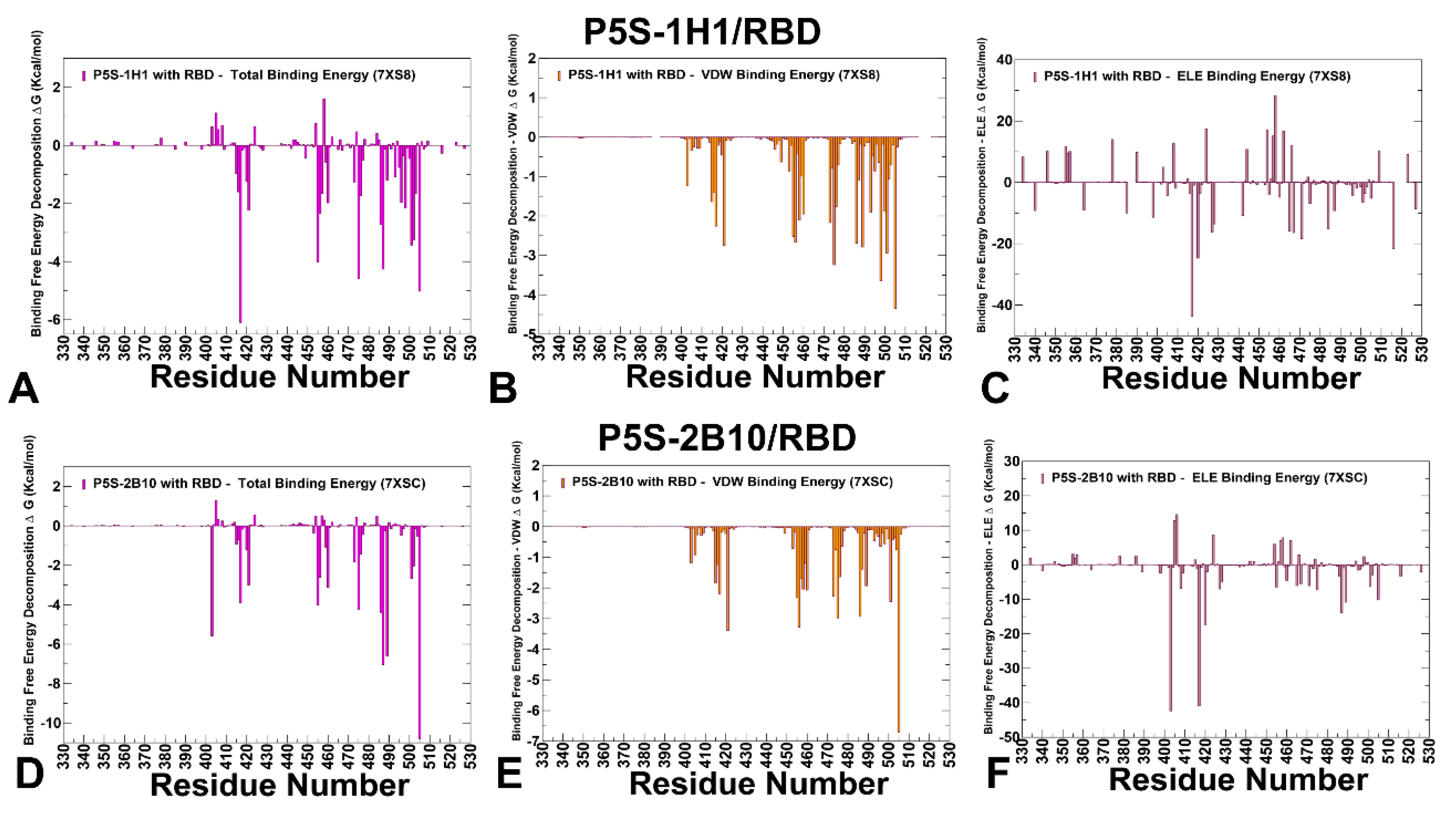

3.4. MM-GBSA Computations of the Binding Energetics and Residue-Based Decomposition Analysis for Class I Antibody-RBD Complexes: Broadly Distributed Footprint of Multiple Binding Hotspots Determines Unique Neutralization Profile of BD55-1205

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Tai, W.; He, L.; Zhang, X.; Pu, J.; Voronin, D.; Jiang, S.; Zhou, Y.; Du, L. Characterization of the receptor-binding domain (RBD) of 2019 novel coronavirus: implication for development of RBD protein as a viral attachment inhibitor and vaccine. Cell. Mol. Immunol. 2020, 17, 613–620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.; Zhang, Y.; Wu, L.; Niu, S.; Song, C.; Zhang, Z.; Lu, G.; Qiao, C.; Hu, Y.; Yuen, K. Y.; Wang, Q.; Zhou, H.; Yan, J.; Qi, J. Structural and functional basis of SARS-CoV-2 entry by using human ACE2. Cell 2020, 181, 894–904.e9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walls, A. C.; Park, Y. J.; Tortorici, M. A.; Wall, A.; McGuire, A. T.; Veesler, D. Structure, Function, and Antigenicity of the SARS-CoV-2 Spike Glycoprotein. Cell 2020, 181, 281–292.e6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wrapp, D.; Wang, N.; Corbett, K. S.; Goldsmith, J. A.; Hsieh, C. L.; Abiona, O.; Graham, B. S.; McLellan, J. S. Cryo-EM structure of the 2019-nCoV spike in the prefusion conformation. Science 2020, 367, 1260–1263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, Y.; Zhang, J.; Xiao, T.; Peng, H.; Sterling, S. M.; Walsh, R. M., Jr.; Rawson, S.; Rits-Volloch, S.; Chen, B. Distinct conformational states of SARS-CoV-2 spike protein. Science 2020, 369, 1586–1592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsieh, C. L.; Goldsmith, J. A.; Schaub, J. M.; DiVenere, A. M.; Kuo, H. C.; Javanmardi, K.; Le, K. C.; Wrapp, D.; Lee, A. G.; Liu, Y. , Chou, C.W.; Byrne, P.O.; Hjorth, C.K.; Johnson, N.V.; Ludes-Meyers J.; Nguyen, A.W.; Park, J.; Wang, N.; Amengor, D.; Lavinder, J.J.; Ippolito, G.C.; Maynard, J.A.; Finkelstein, I.J.; McLellan, J.S. Structure-based design of prefusion-stabilized SARS-CoV-2 spikes. Science 2020, 369, 1501–1505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henderson, R.; Edwards, R. J.; Mansouri, K.; Janowska, K.; Stalls, V.; Gobeil, S. M. C.; Kopp, M.; Li, D.; Parks, R.; Hsu, A. L. , Borgnia, M.J.; Haynes, B.F.; Acharya, P. Controlling the SARS-CoV-2 spike glycoprotein conformation. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 2020, 27, 925–933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCallum, M.; Walls, A. C.; Bowen, J. E.; Corti, D.; Veesler, D. Structure-guided covalent stabilization of coronavirus spike glycoprotein trimers in the closed conformation. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 2020, 27, 942–949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiong, X.; Qu, K.; Ciazynska, K. A.; Hosmillo, M.; Carter, A. P.; Ebrahimi, S.; Ke, Z.; Scheres, S. H. W.; Bergamaschi, L.; Grice, G. L. , Zhang, Y.; CITIID-NIHR COVID-19 BioResource Collaboration, Nathan, J.A.; Baker, S.; James, L.C.; Baxendale, H.E.; Goodfellow, I.; Doffinger, R.; Briggs, J.A.G. A thermostable, closed SARS-CoV-2 spike protein trimer. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 2020, 27, 934–941. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costello, S.M.; Shoemaker, S.R.; Hobbs, H.T.; Nguyen, A.W.; Hsieh, C.L.; Maynard, J.A.; McLellan, J.S.; Pak, J.E.; Marqusee, S. The SARS-CoV-2 spike reversibly samples an open-trimer conformation exposing novel epitopes. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 2022, 27, 229–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCormick, K.D.; Jacobs, J.L.; Mellors, J.W. The emerging plasticity of SARS-CoV-2. Science 2021, 371, 1306–1308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghimire, D.; Han, Y.; Lu, M. Structural Plasticity and Immune Evasion of SARS-CoV-2 Spike Variants. Viruses 2022, 14, 1255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, C.; Wang, Y.; Liu, C.; Zhang, C.; Han, W.; Hong, X.; Wang, Y.; Hong, Q.; Wang, S.; Zhao, Q.; Wang, Y.; Yang, Y.; Chen, K.; Zheng, W.; Kong, L.; Wang, F.; Zuo, Q.; Huang, Z.; Cong, Y. Conformational dynamics of SARS-CoV-2 trimeric spike glycoprotein in complex with receptor ACE2 revealed by cryo-EM. Sci. Adv. 5575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benton, D. J.; Wrobel, A. G.; Xu, P.; Roustan, C.; Martin, S. R.; Rosenthal, P. B.; Skehel, J. J.; Gamblin, S. J. Receptor binding and priming of the spike protein of SARS-CoV-2 for membrane fusion. Nature 2020, 588, 327–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turoňová, B.; Sikora, M.; Schuerman, C.; Hagen, W. J. H.; Welsch, S.; Blanc, F. E. C.; von Bülow, S.; Gecht, M.; Bagola, K.; Hörner, C.; van Zandbergen, G.; Landry, J.; de Azevedo, N. T. D.; Mosalaganti, S.; Schwarz, A.; Covino, R.; Mühlebach, M. D.; Hummer, G.; Krijnse Locker, J.; Beck, M. In situ structural analysis of SARS-CoV-2 spike reveals flexibility mediated by three hinges. Science 2020, 370, 203–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, M.; Uchil, P. D.; Li, W.; Zheng, D.; Terry, D. S.; Gorman, J.; Shi, W.; Zhang, B.; Zhou, T.; Ding, S.; Gasser, R.; Prevost, J.; Beaudoin-Bussieres, G.; Anand, S. P.; Laumaea, A.; Grover, J. R.; Lihong, L.; Ho, D. D.; Mascola, J.R.; Finzi, A.; Kwong, P. D.; Blanchard, S. C.; Mothes, W. Real-time conformational dynamics of SARS-CoV-2 spikes on virus particles. Cell Host Microbe. 2020, 28, 880–891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Z.; Han, Y.; Ding, S.; Shi, W.; Zhou, T.; Finzi, A.; Kwong, P.D.; Mothes, W.; Lu, M. SARS-CoV-2 Variants Increase Kinetic Stability of Open Spike Conformations as an Evolutionary Strategy. mBio 2022, 13, e0322721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Díaz-Salinas, M.A.; Li, Q.; Ejemel, M.; Yurkovetskiy, L.; Luban, J.; Shen, K.; Wang, Y.; Munro, J.B. Conformational dynamics and allosteric modulation of the SARS-CoV-2 spike. Elife 2022, 11, e75433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Liu, C.; Zhang, C.; Wang, Y.; Hong, Q.; Xu, S.; Li, Z.; Yang, Y.; Huang, Z.; Cong, Y. Structural Basis for SARS-CoV-2 Delta Variant Recognition of ACE2 Receptor and Broadly Neutralizing Antibodies. Nat. Commun. 2022, 13, 871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mannar, D.; Saville, J.W.; Zhu, X.; Srivastava, S.S.; Berezuk, A.M.; Tuttle, K.S.; Marquez, A.C.; Sekirov, I.; Subramaniam, S. SARS-CoV-2 Omicron Variant: Ab Evasion and Cryo-EM Structure of Spike Protein–ACE2 Complex. Science 2022, 375, 760–764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, Q.; Han, W.; Li, J.; Xu, S.; Wang, Y.; Xu, C.; Li, Z.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, C.; Huang, Z.; Cong, Y. Molecular Basis of Receptor Binding and Ab Neutralization of Omicron. Nature 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCallum, M.; Czudnochowski, N.; Rosen, L.E.; Zepeda, S.K.; Bowen, J.E.; Walls, A.C.; Hauser, K.; Joshi, A.; Stewart, C.; Dillen, J.R.; Powell, A.E.; Croll, T.I.; Nix, J.; Virgin, H.W.; Corti, D.; Snell, G.; Veesler, D. Structural Basis of SARS-CoV-2 Omicron Immune Evasion and Receptor Engagement. Science 2022, 375, 864–868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yin, W.; Xu, Y.; Xu, P.; Cao, X.; Wu, C.; Gu, C.; He, X.; Wang, X.; Huang, S.; Yuan, Q.; Wu, K.; Hu, W.; Huang, Z.; Liu, J.; Wang, Z.; Jia, F.; Xia, K.; Liu, P.; Wang, X.; Song, B.; Zheng, J.; Jiang, H.; Cheng, X.; Jiang, Y.; Deng, S.J.; Xu, H.E. Structures of the Omicron Spike Trimer with ACE2 and an Anti-Omicron Ab. Science 2022, 375, 1048–1053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gobeil, S. M.-C.; Henderson, R.; Stalls, V.; Janowska, K.; Huang, X.; May, A.; Speakman, M.; Beaudoin, E.; Manne, K.; Li, D.; Parks, R.; Barr, M.; Deyton, M.; Martin, M.; Mansouri, K.; Edwards, R. J.; Eaton, A.; Montefiori, D. C.; Sempowski, G. D.; Saunders, K. O.; Wiehe, K.; Williams, W.; Korber, B.; Haynes, B. F.; Acharya, P. Structural Diversity of the SARS-CoV-2 Omicron Spike. Mol Cell. 2022, 82, 2050–2068.e6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, Z.; Liu, P.; Wang, N.; Wang, L.; Fan, K.; Zhu, Q.; Wang, K.; Chen, R.; Feng, R.; Jia, Z.; Yang, M.; Xu, G.; Zhu, B.; Fu, W.; Chu, T.; Feng, L.; Wang, Y.; Pei, X.; Yang, P.; Xie, X.S.; Cao, L.; Cao, Y.; Wang, X. Structural and Functional Characterizations of Infectivity and Immune Evasion of SARS-CoV-2 Omicron. Cell, 2022; 185, 860–871.e13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parums, DV. Editorial: The XBB.1.5 ('Kraken') Subvariant of Omicron SARS-CoV-2 and its Rapid Global Spread. Med Sci Monit. 2023, 29, e939580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.; Iketani, S.; Li, Z.; Liu, L.; Guo, Y.; Huang, Y.; Bowen, A. D.; Liu, M.; Wang, M.; Yu, J.; Valdez, R.; Lauring, A. S.; Sheng, Z.; Wang, H. H.; Gordon, A.; Liu, L.; Ho, D. D. Alarming Ab Evasion Properties of Rising SARS-CoV-2 BQ and XBB Subvariants. Cell 2023, 186, 279–286.e8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hoffmann, M.; Arora, P.; Nehlmeier, I.; Kempf, A.; Cossmann, A.; Schulz, S. R.; Morillas Ramos, G.; Manthey, L. A.; Jäck, H.-M.; Behrens, G. M. N.; Pöhlmann, S. Profound Neutralization Evasion and Augmented Host Cell Entry Are Hallmarks of the Fast-Spreading SARS-CoV-2 Lineage XBB.1.5. Cell Mol Immunol. 2023, 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamasoba, D.; Uriu, K.; Plianchaisuk, A.; Kosugi, Y.; Pan, L.; Zahradnik, J.; Ito, J.; Sato, K. Virological Characteristics of the SARS-CoV-2 Omicron XBB.1.16 Variant. Lancet Infect Dis. 2023, S1473-3099(23)00278-5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsujino, S.; Deguchi, S.; Nomai, T.; Padilla-Blanco, M.; Plianchaisuk, A.; Wang, L.; Begum, M. M.; Uriu, K.; Mizuma, K.; Nao, N.; Kojima, I.; Tsubo, T.; Li, J.; Matsumura, Y.; Nagao, M.; Oda, Y.; Tsuda, M.; Anraku, Y.; Kita, S.; Yajima, H.; Sasaki-Tabata, K.; Guo, Z.; Hinay, A. A., Jr.; Yoshimatsu, K.; Yamamoto, Y.; Nagamoto, T.; Asakura, H.; Nagashima, M.; Sadamasu, K.; Yoshimura, K.; Nasser, H.; Jonathan, M.; Putri, O.; Kim, Y.; Chen, L.; Suzuki, R.; Tamura, T.; Maenaka, K.; Irie, T.; Matsuno, K.; Tanaka, S.; Ito, J.; Ikeda, T.; Takayama, K.; Zahradnik, J.; Hashiguchi, T.; Fukuhara, T.; Sato, K. Virological Characteristics of the SARS-CoV-2 Omicron EG.5.1 Variant. Microbiol Immunol. 2024, 68, 305–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.; Guo, Y.; Zhang, R. M.; Ho, J.; Mohri, H.; Valdez, R.; Manthei, D. M.; Gordon, A.; Liu, L.; Ho, D. D. Ab Neutralization of Emerging SARS-CoV-2 Subvariants: EG.5.1 and XBC.1.6. Lancet Infect Dis. 2023, 23, e397–e398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faraone, J. N.; Qu, P.; Goodarzi, N.; Zheng, Y.-M.; Carlin, C.; Saif, L. J.; Oltz, E. M.; Xu, K.; Jones, D.; Gumina, R. J.; Liu, S.-L. Immune Evasion and Membrane Fusion of SARS-CoV-2 XBB Subvariants EG.5.1 and XBB.2.3. Emerg. Microbes Infect. 2023, 12, 2270069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kosugi, Y.; Plianchaisuk, A.; Putri, O.; Uriu, K.; Kaku, Y.; Hinay, A. A.; Chen, L.; Kuramochi, J.; Sadamasu, K.; Yoshimura, K.; Asakura, H.; Nagashima, M.; Ito, J.; Sato, K.; Misawa, N.; Guo, Z.; Tolentino, J. E. M.; Fujita, S.; Pan, L.; Suganami, M.; Chiba, M.; Yoshimura, R.; Yasuda, K.; Iida, K.; Ohsumi, N.; Strange, A. P.; Tanaka, S.; Fukuhara, T.; Tamura, T.; Suzuki, R.; Suzuki, S.; Ito, H.; Matsuno, K.; Sawa, H.; Nao, N.; Tanaka, S.; Tsuda, M.; Wang, L.; Oda, Y.; Ferdous, Z.; Shishido, K.; Nakagawa, S.; Shirakawa, K.; Takaori-Kondo, A.; Nagata, K.; Nomura, R.; Horisawa, Y.; Tashiro, Y.; Kawai, Y.; Takayama, K.; Hashimoto, R.; Deguchi, S.; Watanabe, Y.; Sakamoto, A.; Yasuhara, N.; Hashiguchi, T.; Suzuki, T.; Kimura, K.; Sasaki, J.; Nakajima, Y.; Yajima, H.; Irie, T.; Kawabata, R.; Tabata, K.; Ikeda, T.; Nasser, H.; Shimizu, R.; Begum, M. M.; Jonathan, M.; Mugita, Y.; Takahashi, O.; Ichihara, K.; Ueno, T.; Motozono, C.; Toyoda, M.; Saito, A.; Shofa, M.; Shibatani, Y.; Nishiuchi, T. Characteristics of the SARS-CoV-2 Omicron HK.3 Variant Harbouring the FLip Substitution. Lancet Microbe, 2024; S2666-5247(23)00373-7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.; Guo, Y.; Liu, L.; Schwanz, L. T.; Li, Z.; Nair, M. S.; Ho, J.; Zhang, R. M.; Iketani, S.; Yu, J.; Huang, Y.; Qu, Y.; Valdez, R.; Lauring, A. S.; Huang, Y.; Gordon, A.; Wang, H. H.; Liu, L.; Ho, D. D. Antigenicity and Receptor Affinity of SARS-CoV-2 BA.2.86 Spike. Nature 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, S.; Yu, Y.; Jian, F.; Song, W.; Yisimayi, A.; Chen, X.; Xu, Y.; Wang, P.; Wang, J.; Yu, L.; Niu, X.; Wang, J.; Xiao, T.; An, R.; Wang, Y.; Gu, Q.; Shao, F.; Jin, R.; Shen, Z.; Wang, Y.; Cao, Y. Antigenicity and Infectivity Characterization of SARS-CoV-2 BA.2.86. Lancet Infect Dis. 2023, 23, e457–e459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tamura, T.; Mizuma, K.; Nasser, H.; Deguchi, S.; Padilla-Blanco, M.; Oda, Y.; Uriu, K.; Tolentino, J. E. M.; Tsujino, S.; Suzuki, R.; Kojima, I.; Nao, N.; Shimizu, R.; Wang, L.; Tsuda, M.; Jonathan, M.; Kosugi, Y.; Guo, Z.; Hinay, A. A., Jr.; Putri, O.; Kim, Y.; Tanaka, Y. L.; Asakura, H.; Nagashima, M.; Sadamasu, K.; Yoshimura, K.; Saito, A.; Ito, J.; Irie, T.; Tanaka, S.; Zahradnik, J.; Ikeda, T.; Takayama, K.; Matsuno, K.; Fukuhara, T.; Sato, K. Virological Characteristics of the SARS-CoV-2 BA.2.86 Variant. Cell Host Microbe. 2024, 32, 170–180.e12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, C.; Zhou, D.; Dijokaite-Guraliuc, A.; Supasa, P.; Duyvesteyn, H. M. E.; Ginn, H. M.; Selvaraj, M.; Mentzer, A. J.; Das, R.; de Silva, T. I.; Ritter, T. G.; Plowright, M.; Newman, T. A. H.; Stafford, L.; Kronsteiner, B.; Temperton, N.; Lui, Y.; Fellermeyer, M.; Goulder, P.; Klenerman, P.; Dunachie, S. J.; Barton, M. I.; Kutuzov, M. A.; Dushek, O.; Fry, E. E.; Mongkolsapaya, J.; Ren, J.; Stuart, D. I.; Screaton, G. R. A Structure-Function Analysis SARS-CoV-2 BA.2.86 Balances Ab Escape and ACE2 Affinity. Cell Rep Med. 2024, 5, 101553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, K.; Lustig, G.; Römer, C.; Reedoy, K.; Jule, Z.; Karim, F.; Ganga, Y.; Bernstein, M.; Baig, Z.; Jackson, L.; Mahlangu, B.; Mnguni, A.; Nzimande, A.; Stock, N.; Kekana, D.; Ntozini, B.; van Deventer, C.; Marshall, T.; Manickchund, N.; Gosnell, B. I.; Lessells, R. J.; Karim, Q. A.; Abdool Karim, S. S.; Moosa, M.-Y. S.; de Oliveira, T.; von Gottberg, A.; Wolter, N.; Neher, R. A.; Sigal, A. Evolution and Neutralization Escape of the SARS-CoV-2 BA.2.86 Subvariant. Nat Commun. 2023, 14, 8078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, S.; Yu, Y.; Xu, Y.; Jian, F.; Song, W.; Yisimayi, A.; Wang, P.; Wang, J.; Liu, J.; Yu, L.; Niu, X.; Wang, J.; Wang, Y.; Shao, F.; Jin, R.; Wang, Y.; Cao, Y. Fast Evolution of SARS-CoV-2 BA.2.86 to JN.1 under Heavy Immune Pressure. Lancet Infect Dis. 2024, 24, e70–e72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kaku, Y.; Okumura, K.; Padilla-Blanco, M.; Kosugi, Y.; Uriu, K.; Hinay, A. A., Jr; Chen, L.; Plianchaisuk, A.; Kobiyama, K.; Ishii, K. J.; Zahradnik, J.; Ito, J.; Sato, K., K. Virological Characteristics of the SARS-CoV-2 JN.1 Variant. Lancet Infect Dis. 2024, 24, e82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, P.; Faraone, J. N.; Hsu, C. C.; Chamblee, M.; Zheng, Y.-M.; Carlin, C.; Bednash, J. S.; Horowitz, J. C.; Mallampalli, R. K.; Saif, L. J.; Oltz, E. M.; Jones, D.; Li, J.; Gumina, R. J.; Xu, K.; Liu, S.-L. Neutralization Escape, Infectivity, and Membrane Fusion of JN.1-Derived SARS-CoV-2 SLip, FLiRT, and KP.2 Variants. Cell Rep. 2024, 43, 114520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qu, P.; Faraone, J. N.; Evans, J. P.; Zheng, Y.-M.; Carlin, C.; Anghelina, M.; Stevens, P.; Fernandez, S.; Jones, D.; Panchal, A. R.; Saif, L. J.; Oltz, E. M.; Zhang, B.; Zhou, T.; Xu, K.; Gumina, R. J.; Liu, S.-L. Enhanced Evasion of Neutralizing Ab Response by Omicron XBB.1.5, CH.1.1, and CA.3.1 Variants. Cell Rep. 2023; 42, 112443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaku, Y.; Uriu, K.; Kosugi, Y.; Okumura, K.; Yamasoba, D.; Uwamino, Y.; Kuramochi, J.; Sadamasu, K.; Yoshimura, K.; Asakura, H.; Nagashima, M.; Ito, J.; Sato, K. Virological Characteristics of the SARS-CoV-2 KP.2 Variant. Lancet Infect Dis. 2024, 24, e416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaku, Y.; Yo, M. S.; Tolentino, J. E.; Uriu, K.; Okumura, K.; Ito, J.; Sato, K. Virological Characteristics of the SARS-CoV-2 KP.3, LB.1, and KP.2.3 Variants. Lancet Infect Dis. 2024, 24, e482–e483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.; Mellis, I. A.; Ho, J.; Bowen, A.; Kowalski-Dobson, T.; Valdez, R.; Katsamba, P. S.; Wu, M.; Lee, C.; Shapiro, L.; Gordon, A.; Guo, Y.; Ho, D. D.; Liu, L. Recurrent SARS-CoV-2 Spike Mutations Confer Growth Advantages to Select JN.1 Sublineages. Emerg Microbes Infect. 2024, 13, 2402880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jian, F.; Wang, J.; Yisimayi, A.; Song, W.; Xu, Y.; Chen, X.; Niu, X.; Yang, S.; Yu, Y.; Wang, P.; Sun, H.; Yu, L.; Wang, J.; Wang, Y.; An, R.; Wang, W.; Ma, M.; Xiao, T.; Gu, Q.; Shao, F.; Wang, Y.; Shen, Z.; Jin, R.; Cao, Y. Evolving Antibody Response to SARS-CoV-2 Antigenic Shift from XBB to JN.1. Nature 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Taylor, A. L.; Starr, T. N. Deep Mutational Scanning of SARS-CoV-2 Omicron BA.2.86 and Epistatic Emergence of the KP.3 Variant. Virus Evol. 2024, 10, veae067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, L.; Sun, Z.; Zhang, Y.; Jian, F.; Yang, S.; Xia, K.; Yu, L.; Wang, J.; Shao, F.; Wang, X.; Cao, Y. Structural and Molecular Basis of the Epistasis Effect in Enhanced Affinity between SARS-CoV-2 KP.3 and ACE2. Cell Discov. 2024, 10, 123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Yu, Y.; Jian, F.; Yang, S.; Song, W.; Wang, P.; Yu, L.; Shao, F.; Cao, Y. Enhanced Immune Evasion of SARS-CoV-2 Variants KP.3.1.1 and XEC through N-Terminal Domain Mutations. Lancet Infect Dis. 2025; 25, e6–e7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaku, Y.; Uriu, K.; Okumura, K.; Ito, J.; Sato, K. Virological Characteristics of the SARS-CoV-2 KP.3.1.1 Variant. Lancet Infect Dis. 2024, 24, e609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kaku, Y.; Okumura, K.; Kawakubo, S.; Uriu, K.; Chen, L.; Kosugi, Y.; Uwamino, Y.; Begum, M. M.; Leong, S.; Ikeda, T.; Sadamasu, K.; Asakura, H.; Nagashima, M.; Yoshimura, K.; Ito, J.; Sato, K. Virological Characteristics of the SARS-CoV-2 XEC Variant. Lancet Infect Dis. 2024, S1473-3099(24)00731-X. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.; Guo, Y.; Mellis, I. A.; Wu, M.; Mohri, H.; Gherasim, C.; Valdez, R.; Purpura, L. J.; Yin, M. T.; Gordon, A.; Ho, D. D. Antibody Evasiveness of SARS-CoV-2 Subvariants KP.3.1.1 and XEC. Cell Rep. 2025, 44, 115543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, Z.; Huang, J.; Baboo, S.; Diedrich, J. K.; Bangaru, S.; Paulson, J. C.; Yates, J. R., III; Yuan, M.; Wilson, I. A.; Ward, A. B. Structural and Functional Insights into the Evolution of SARS-CoV-2 KP.3.1.1 Spike Protein, bioRxiv 2024. [CrossRef]

- Kaku, Y.; Uriu, K.; Okumura, K.; Ito, J.; Sato, K. Virological Characteristics of the SARS-CoV-2 KP. 3.1.1 Variant. Lancet Infect Dis. 2024, 24, e609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Yu, Y.; Yang, S.; Jian, F.; Song, W.; Yu, L.; Shao, F.; Cao, Y. Virological and Antigenic Characteristics of SARS-CoV-2 Variants LF.7.2.1, NP.1, and LP.8.1. Lancet Infect Dis. 2025, 25, e128–e130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, C.; Yu, Y.; Liu, J.; Jian, F.; Yang, S.; Song, W.; Yu, L.; Shao, F.; Cao, Y. Antigenic and Virological Characteristics of SARS-CoV-2 Variants BA.3.2, XFG, and NB.1.8.1. Lancet Infect Dis. [CrossRef]

- Cao, Y.; Wang, J.; Jian, F.; Xiao, T.; Song, W.; Yisimayi, A.; Huang, W.; Li, Q.; Wang, P.; An, R.; Wang, J.; Wang, Y.; Niu, X.; Yang, S.; Liang, H.; Sun, H.; Li, T.; Yu, Y.; Cui, Q.; Liu, S.; Yang, X.; Du, S.; Zhang, Z.; Hao, X.; Shao, F.; Jin, R.; Wang, X.; Xiao, J.; Wang, Y.; Xie, X. S. Omicron Escapes the Majority of Existing SARS-CoV-2 Neutralizing Antibodies. Nature 2022, 602, 657–663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, Y.; Yisimayi, A.; Jian, F.; Song, W.; Xiao, T.; Wang, L.; Du, S.; Wang, J.; Li, Q.; Chen, X.; Yu, Y.; Wang, P.; Zhang, Z.; Liu, P.; An, R.; Hao, X.; Wang, Y.; Wang, J.; Feng, R.; Sun, H.; Zhao, L.; Zhang, W.; Zhao, D.; Zheng, J.; Yu, L.; Li, C.; Zhang, N.; Wang, R.; Niu, X.; Yang, S.; Song, X.; Chai, Y.; Hu, Y.; Shi, Y.; Zheng, L.; Li, Z.; Gu, Q.; Shao, F.; Huang, W.; Jin, R.; Shen, Z.; Wang, Y.; Wang, X.; Xiao, J.; Xie, X. S. BA. 2.12.1, BA.4 and BA.5 Escape Antibodies Elicited by Omicron Infection. Nature 2022, 608, 593–602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cao, Y.; Jian, F.; Wang, J.; Yu, Y.; Song, W.; Yisimayi, A.; Wang, J.; An, R.; Chen, X.; Zhang, N.; Wang, Y.; Wang, P.; Zhao, L.; Sun, H.; Yu, L.; Yang, S.; Niu, X.; Xiao, T.; Gu, Q.; Shao, F.; Hao, X.; Xu, Y.; Jin, R.; Shen, Z.; Wang, Y.; Xie, X. S. Imprinted SARS-CoV-2 Humoral Immunity Induces Convergent Omicron RBD Evolution. Nature 2023, 614, 521–529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cao, Y.; Jian, F.; Zhang, Z.; Yisimayi, A.; Hao, X.; Bao, L.; Yuan, F.; Yu, Y.; Du, S.; Wang, J.; Xiao, T.; Song, W.; Zhang, Y.; Liu, P.; An, R.; Wang, P.; Wang, Y.; Yang, S.; Niu, X.; Zhang, Y.; Gu, Q.; Shao, F.; Hu, Y.; Yin, W.; Zheng, A.; Wang, Y.; Qin, C.; Jin, R.; Xiao, J.; Xie, X. S. Rational Identification of Potent and Broad Sarbecovirus-Neutralizing Antibody Cocktails from SARS Convalescents. Cell Rep. 2022, 41, 111845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yisimayi, A.; Song, W.; Wang, J.; Jian, F.; Yu, Y.; Chen, X.; Xu, Y.; Yang, S.; Niu, X.; Xiao, T.; Wang, J.; Zhao, L.; Sun, H.; An, R.; Zhang, N.; Wang, Y.; Wang, P.; Yu, L.; Lv, Z.; Gu, Q.; Shao, F.; Jin, R.; Shen, Z.; Xie, X. S.; Wang, Y.; Cao, Y. Repeated Omicron Exposures Override Ancestral SARS-CoV-2 Immune Imprinting. Nature 2024, 625, 148–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jian, F.; Wec, A. Z.; Feng, L.; Yu, Y.; Wang, L.; Wang, P.; Yu, L.; Wang, J.; Hou, J.; Berrueta, D. M.; Lee, D.; Speidel, T.; Ma, L.; Kim, T.; Yisimayi, A.; Song, W.; Wang, J.; Liu, L.; Yang, S.; Niu, X.; Xiao, T.; An, R.; Wang, Y.; Shao, F.; Wang, Y.; Pecetta, S.; Wang, X.; Walker, L. M.; Cao, Y. Viral Evolution Prediction Identifies Broadly Neutralizing Antibodies against Existing and Prospective SARS-CoV-2 Variants, bioRxiv, 2024. [CrossRef]

- Rosen, L. E.; Tortorici, M. A.; De Marco, A.; Pinto, D.; Foreman, W. B.; Taylor, A. L.; Park, Y.-J.; Bohan, D.; Rietz, T.; Errico, J. M.; Hauser, K.; Dang, H. V.; Chartron, J. W.; Giurdanella, M.; Cusumano, G.; Saliba, C.; Zatta, F.; Sprouse, K. R.; Addetia, A.; Zepeda, S. K.; Brown, J.; Lee, J.; Dellota, E., Jr.; Rajesh, A.; Noack, J.; Tao, Q.; DaCosta, Y.; Tsu, B.; Acosta, R.; Subramanian, S.; de Melo, G. D.; Kergoat, L.; Zhang, I.; Liu, Z.; Guarino, B.; Schmid, M. A.; Schnell, G.; Miller, J. L.; Lempp, F. A.; Czudnochowski, N.; Cameroni, E.; Whelan, S. P. J.; Bourhy, H.; Purcell, L. A.; Benigni, F.; di Iulio, J.; Pizzuto, M. S.; Lanzavecchia, A.; Telenti, A.; Snell, G.; Corti, D.; Veesler, D.; Starr, T. N. A Potent Pan-Sarbecovirus Neutralizing Antibody Resilient to Epitope Diversification. Cell 2024, 187, 7196–7213.e26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, S.; Alshahrani, M.; Gupta, G.; Tao, P.; Verkhivker, G. Markov State Models and Perturbation-Based Approaches Reveal Distinct Dynamic Signatures and Hidden Allosteric Pockets in the Emerging SARS-Cov-2 Spike Omicron Variant Complexes with the Host Receptor: The Interplay of Dynamics and Convergent Evolution Modulates Allostery and Functional Mechanisms. J. Chem. Inf. Model. 2023, 63, 5272–5296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raisinghani, N.; Alshahrani, M.; Gupta, G.; Xiao, S.; Tao, P.; Verkhivker, G. AlphaFold2 Predictions of Conformational Ensembles and Atomistic Simulations of the SARS-CoV-2 Spike XBB Lineages Reveal Epistatic Couplings between Convergent Mutational Hotspots That Control ACE2 Affinity. J. Phys. Chem. B. 2024, 128, 4696–4715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raisinghani, N.; Alshahrani, M.; Gupta, G.; Verkhivker, G. Ensemble-Based Mutational Profiling and Network Analysis of the SARS-CoV-2 Spike Omicron XBB Lineages for Interactions with the ACE2 Receptor and Antibodies: Cooperation of Binding Hotspots in Mediating Epistatic Couplings Underlies Binding Mechanism and Immune Escape. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 4281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raisinghani, N.; Alshahrani, M.; Gupta, G.; Verkhivker, G. AlphaFold2 Modeling and Molecular Dynamics Simulations of the Conformational Ensembles for the SARS-CoV-2 Spike Omicron JN.1, KP.2 and KP.3 Variants: Mutational Profiling of Binding Energetics Reveals Epistatic Drivers of the ACE2 Affinity and Escape Hotspots of Antibody Resistance. Viruses, 1458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verkhivker, G.; Alshahrani, M.; Gupta, G. Balancing Functional Tradeoffs between Protein Stability and ACE2 Binding in the SARS-CoV-2 Omicron BA.2, BA.2.75 and XBB Lineages: Dynamics-Based Network Models Reveal Epistatic Effects Modulating Compensatory Dynamic and Energetic Changes. Viruses 2023, 15, 1143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verkhivker, G.; Agajanian, S.; Kassab, R.; Krishnan, K. Integrating Conformational Dynamics and Perturbation-Based Network Modeling for Mutational Profiling of Binding and Allostery in the SARS-CoV-2 Spike Variant Complexes with Antibodies: Balancing Local and Global Determinants of Mutational Escape Mechanisms. Biomolecules 2022, 12, 964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alshahrani, M.; Parikh, V.; Foley, B.; Raisinghani, N.; Verkhivker, G. Quantitative Characterization and Prediction of the Binding Determinants and Immune Escape Hotspots for Groups of Broadly Neutralizing Antibodies Against Omicron Variants: Atomistic Modeling of the SARS-CoV-2 Spike Complexes with Antibodies. Biomolecules 2025, 15, 249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alshahrani, M.; Parikh, V.; Foley, B.; Verkhivker, G. Integrative Computational Modeling of Distinct Binding Mechanisms for Broadly Neutralizing Antibodies Targeting SARS-CoV-2 Spike Omicron Variants: Balance of Evolutionary and Dynamic Adaptability in Shaping Molecular Determinants of Immune Escape. Viruses 2025, 17, 741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, H.; Guo, H.; Wang, A.; Cao, L.; Fan, Q.; Jiang, J.; Wang, M.; Lin, L.; Ge, X.; Wang, H.; Zhang, R.; Liao, M.; Yan, R.; Ju, B.; Zhang, Z. Structural Basis for the Evolution and Antibody Evasion of SARS-CoV-2 BA.2.86 and JN.1 Subvariants. Nat Commun. 2024, 15, 7715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yajima, H.; Nomai, T.; Okumura, K.; Maenaka, K.; Ito, J.; Hashiguchi, T.; Sato, K.; Matsuno, K.; Nao, N.; Sawa, H.; Mizuma, K.; Li, J.; Kida, I.; Mimura, Y.; Ohari, Y.; Tanaka, S.; Tsuda, M.; Wang, L.; Oda, Y.; Ferdous, Z.; Shishido, K.; Mohri, H.; Iida, M.; Fukuhara, T.; Tamura, T.; Suzuki, R.; Suzuki, S.; Tsujino, S.; Ito, H.; Kaku, Y.; Misawa, N.; Plianchaisuk, A.; Guo, Z.; Hinay, A. A., Jr.; Usui, K.; Saikruang, W.; Lytras, S.; Uriu, K.; Yoshimura, R.; Kawakubo, S.; Nishumura, L.; Kosugi, Y.; Fujita, S.; M. Tolentino, J. E.; Chen, L.; Pan, L.; Li, W.; Yo, M. S.; Horinaka, K.; Suganami, M.; Chiba, M.; Yasuda, K.; Iida, K.; Strange, A. P.; Ohsumi, N.; Tanaka, S.; Ogawa, E.; Fukuda, T.; Osujo, R.; Yoshimura, K.; Sadamas, K.; Nagashima, M.; Asakura, H.; Yoshida, I.; Nakagawa, S.; Takayama, K.; Hashimoto, R.; Deguchi, S.; Watanabe, Y.; Nakata, Y.; Futatsusako, H.; Sakamoto, A.; Yasuhara, N.; Suzuki, T.; Kimura, K.; Sasaki, J.; Nakajima, Y.; Irie, T.; Kawabata, R.; Sasaki-Tabata, K.; Ikeda, T.; Nasser, H.; Shimizu, R.; Begum, M. M.; Jonathan, M.; Mugita, Y.; Leong, S.; Takahashi, O.; Ueno, T.; Motozono, C.; Toyoda, M.; Saito, A.; Kosaka, A.; Kawano, M.; Matsubara, N.; Nishiuchi, T.; Zahradnik, J.; Andrikopoulos, P.; Padilla-Blanco, M.; Konar, A. Molecular and Structural Insights into SARS-CoV-2 Evolution: From BA.2 to XBB Subvariants. mBio. 2024, 15, e0322023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xue, S.; Han, Y.; Wu, F.; Wang, Q. Mutations in the SARS-CoV-2 Spike Receptor Binding Domain and Their Delicate Balance between ACE2 Affinity and Antibody Evasion. Protein Cell. 2024, 15, 403–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kmiecik, S.; Kolinski, A. Characterization of protein-folding pathways by reduced-space modeling. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2007, 104, 12330–12335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kmiecik, S.; Gront, D.; Kolinski, M.; Wieteska, L.; Dawid, A.E.; Kolinski, A. Coarse-grained protein models and their applications. Chem. Rev. 2016, 116, 7898–7936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kmiecik, S.; Kouza, M.; Badaczewska-Dawid, A.E.; Kloczkowski, A.; Kolinski, A. Modeling of protein structural flexibility and large-scale dynamics: Coarse-grained simulations and elastic network models. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2018, 19, 3496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ciemny, M.P.; Badaczewska-Dawid, A.E.; Pikuzinska, M.; Kolinski, A.; Kmiecik, S. Modeling of disordered protein structures using monte carlo simulations and knowledge-based statistical force fields. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019, 20, 606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kurcinski, M.; Oleniecki, T.; Ciemny, M.P.; Kuriata, A.; Kolinski, A.; Kmiecik, S. CABS-flex standalone: A simulation environment for fast modeling of protein flexibility. Bioinformatics 2019, 35, 694–695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Badaczewska-Dawid, A. E.; Kolinski, A.; Kmiecik, S. Protocols for fast simulations of protein structure flexibility using CABS-Flex and SURPASS. Methods Mol. Biol. 2020, 2165, 337–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rose, P. W.; Prlic, A.; Altunkaya, A.; Bi, C.; Bradley, A. R.; Christie, C. H.; Costanzo, L. D.; Duarte, J. M.; Dutta, S.; Feng, Z.; Green, R. K.; Goodsell, D. S.; Hudson, B.; Kalro, T.; Lowe, R.; Peisach, E.; Randle, C.; Rose, A. S.; Shao, C.; Tao, Y. P.; Valasatava, Y.; Voigt, M.; Westbrook, J. D.; Woo, J.; Yang, H.; Young, J. Y.; Zardecki, C.; Berman, H. M.; Burley, S. K. The RCSB protein data bank: integrative view of protein, gene and 3D structural information. Nucleic Acids Res. 2017, 45, D271–D281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marti-Renom, M. A.; Stuart, A. C.; Fiser, A.; Sanchez, R.; Melo, F.; Sali, A. Comparative protein structure modeling of genes and genomes. Annu. Rev. Biophys. Biomol. Struct. 2000, 29, 291–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rotkiewicz, P.; Skolnick, J. , Fast procedure for reconstruction of full-atom protein models from reduced representations. J. Comput. Chem. 2008, 29, 1460–1465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lombardi, L. E.; Marti, M. A.; Capece, L. CG2AA: backmapping protein coarse-grained structures. Bioinformatics 2016, 32, 1235–1237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bhattacharya, D.; Nowotny, J.; Cao, R.; Cheng, J. 3Drefine: an interactive web server for efficient protein structure refinement. Nucleic Acids Res. 2016, 44, W406–W409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dehouck, Y.; Kwasigroch, J. M.; Rooman, M.; Gilis, D. BeAtMuSiC: Prediction of changes in protein-protein binding affinity on mutations. Nucleic Acids Res. 2013, 41, W333–W339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dehouck, Y.; Gilis, D.; Rooman, M. A new generation of statistical potentials for proteins. Biophys. J. 2006, 90, 4010–4017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dehouck, Y.; Grosfils, A.; Folch, B.; Gilis, D.; Bogaerts, P.; Rooman, M. Fast and accurate predictions of protein stability changes upon mutations using statistical potentials and neural networks:PoPMuSiC-2.0. Bioinformatics 2009, 25, 2537–2543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Srinivasan, J.; Cheatham, T. E.; Cieplak, P.; Kollman, P. A.; Case, D. A. Continuum Solvent Studies of the Stability of DNA, RNA, and Phosphoramidate−DNA Helices. J. Amer. Chem. Soc. 1998, 120, 9401–9409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kollman, P. A.; Massova, I.; Reyes, C.; Kuhn, B.; Huo, S.; Chong, L.; Lee, M.; Lee, T.; Duan, Y.; Wang, W.; Donini, O.; Cieplak, P.; Srinivasan, J.; Case, D. A.; Cheatham, T. E. Calculating Structures and Free Energies of Complex Molecules: Combining Molecular Mechanics and Continuum Models. Acc. Chem. Res. 2000, 33, 889–897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hou, T.; Wang, J.; Li, Y.; Wang, W. Assessing the Performance of the MM/PBSA and MM/GBSA Methods. 1. The Accuracy of Binding Free Energy Calculations Based on Molecular Dynamics Simulations. J. Chem. Inf. Model. 2011, 51, 69–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Weng, G.; Wang, E.; Wang, Z.; Liu, H.; Zhu, F.; Li, D.; Hou, T. HawkDock: A Web Server to Predict and Analyze the Protein–Protein Complex Based on Computational Docking and MM/GBSA. Nucleic Acids Res. 2019, 47, W322–W330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mongan, J.; Simmerling, C.; McCammon, J. A.; Case, D. A.; Onufriev, A. Generalized Born Model with a Simple, Robust Molecular Volume Correction. J Chem Theory Comput. 2007, 3, 156–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, A. H.; Zhan, C.-G. Generalized Methodology for the Quick Prediction of Variant SARS-CoV-2 Spike Protein Binding Affinities with Human Angiotensin-Converting Enzyme II. J. Phys. Chem. B. 2022, 126, 2353–2360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, H.; Duan, L.; Chen, F.; Liu, H.; Wang, Z.; Pan, P.; Zhu, F.; Zhang, J. Z. H.; Hou, T. Assessing the Performance of MM/PBSA and MM/GBSA Methods. 7. Entropy Effects on the Performance of End-Point Binding Free Energy Calculation Approaches. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2018, 20, 14450–14460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, B. R., III; McGee, T. D., Jr.; Swails, J. M.; Homeyer, N.; Gohlke, H.; Roitberg, A. E. MMPBSA.Py: An Efficient Program for End-State Free Energy Calculations. J Chem Theory Comput. 2012, 8, 3314–3321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valdés-Tresanco, M. S.; Valdés-Tresanco, M. E.; Valiente, P. A.; Moreno, E. gmx_MMPBSA: A New Tool to Perform End-State Free Energy Calculations with GROMACS. J Chem Theory Comput. 2021, 17, 6281–6291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, S.; Cao, Y.; Zhu, Q.; Yu, P.; Qi, F.; Wang, G.; Du, X.; Bao, L.; Deng, W.; Zhu, H.; Liu, J.; Nie, J.; Zheng, Y.; Liang, H.; Liu, R.; Gong, S.; Xu, H.; Yisimayi, A.; Lv, Q.; Wang, B.; He, R.; Han, Y.; Zhao, W.; Bai, Y.; Qu, Y.; Gao, X.; Ji, C.; Wang, Q.; Gao, N.; Huang, W.; Wang, Y.; Xie, X. S.; Su, X.; Xiao, J.; Qin, C. Structurally Resolved SARS-CoV-2 Antibody Shows High Efficacy in Severely Infected Hamsters and Provides a Potent Cocktail Pairing Strategy. Cell 2020, 183, 1013–1023.e13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, Q.; Wu, L.; Xu, Z.; Wang, X.; Xie, Y.; Chai, Y.; Zheng, A.; Zhou, J.; Qiao, S.; Huang, M.; Shang, G.; Zhao, X.; Feng, Y.; Qi, J.; Gao, G. F.; Wang, Q. An Updated Atlas of Antibody Evasion by SARS-CoV-2 Omicron Sub-Variants Including BQ.1.1 and XBB. Cell Rep Med. 2023, 4, 100991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nutalai, R.; Zhou, D.; Tuekprakhon, A.; Ginn, H. M.; Supasa, P.; Liu, C.; Huo, J.; Mentzer, A. J.; Duyvesteyn, H. M. E.; Dijokaite-Guraliuc, A.; Skelly, D.; Ritter, T. G.; Amini, A.; Bibi, S.; Adele, S.; Johnson, S. A.; Constantinides, B.; Webster, H.; Temperton, N.; Klenerman, P.; Barnes, E.; Dunachie, S. J.; Crook, D.; Pollard, A. J.; Lambe, T.; Goulder, P.; Paterson, N. G.; Williams, M. A.; Hall, D. R.; Mongkolsapaya, J.; Fry, E. E.; Dejnirattisai, W.; Ren, J.; Stuart, D. I.; Screaton, G. R. Potent Cross-Reactive Antibodies Following Omicron Breakthrough in Vaccinees. Cell 2022, 185, 2116–2131.e18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, C.; Das, R.; Dijokaite-Guraliuc, A.; Zhou, D.; Mentzer, A. J.; Supasa, P.; Selvaraj, M.; Duyvesteyn, H. M. E.; Ritter, T. G.; Temperton, N.; Klenerman, P.; Dunachie, S. J.; Paterson, N. G.; Williams, M. A.; Hall, D. R.; Fry, E. E.; Mongkolsapaya, J.; Ren, J.; Stuart, D. I.; Screaton, G. R. Emerging Variants Develop Total Escape from Potent Monoclonal Antibodies Induced by BA. 4/5 Infection. Nat Commun. 2024, 15, 3284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ju, B.; Zhang, Q.; Wang, Z.; Aw, Z. Q.; Chen, P.; Zhou, B.; Wang, R.; Ge, X.; Lv, Q.; Cheng, L.; Zhang, R.; Wong, Y. H.; Chen, H.; Wang, H.; Shan, S.; Liao, X.; Shi, X.; Liu, L.; Chu, J. J. H.; Wang, X.; Zhang, Z.; Zhang, L. Infection with Wild-Type SARS-CoV-2 Elicits Broadly Neutralizing and Protective Antibodies against Omicron Subvariants. Nat Immunol 2023, 24, 690–699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Greaney, A. J.; Starr, T. N.; Bloom, J. D. An Antibody-Escape Estimator for Mutations to the SARS-CoV-2 Receptor-Binding Domain. Virus Evol. 2022, 8, veac021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dadonaite, B.; Crawford, K. H. D.; Radford, C. E.; Farrell, A. G.; Yu, T. C.; Hannon, W. W.; Zhou, P.; Andrabi, R.; Burton, D. R.; Liu, L.; Ho, D. D.; Chu, H. Y.; Neher, R. A.; Bloom, J. D. A Pseudovirus System Enables Deep Mutational Scanning of the Full SARS-CoV-2 Spike. Cell 2023, 186, 1263–1278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dadonaite, B.; Brown, J.; McMahon, T. E.; Farrell, A. G.; Figgins, M. D.; Asarnow, D.; Stewart, C.; Lee, J.; Logue, J.; Bedford, T.; Murrell, B.; Chu, H. Y.; Veesler, D.; Bloom, J. D. Spike Deep Mutational Scanning Helps Predict Success of SARS-CoV-2 Clades. Nature. 2024, 631, 617–626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jian, F.; Feng, L.; Yang, S.; Yu, Y.; Wang, L.; Song, W.; Yisimayi, A.; Chen, X.; Xu, Y.; Wang, P.; Yu, L.; Wang, J.; Liu, L.; Niu, X.; Wang, J.; Xiao, T.; An, R.; Wang, Y.; Gu, Q.; Shao, F.; Jin, R.; Shen, Z.; Wang, Y.; Wang, X.; Cao, Y. Convergent Evolution of SARS-CoV-2 XBB Lineages on Receptor-Binding Domain 455–456 Synergistically Enhances Antibody Evasion and ACE2 Binding. PLoS Pathog. 2023, 19, e1011868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.; Guo, Y.; Zhang, R. M.; Ho, J.; Mohri, H.; Valdez, R.; Manthei, D. M.; Gordon, A.; Liu, L.; Ho, D. D. Antibody Neutralisation of Emerging SARS-CoV-2 Subvariants: EG.5.1 and XBC.1.6. Lancet Infect Dis. 2023, 23, e397–e398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, S.; Yu, Y.; Jian, F.; Yisimayi, A.; Song, W.; Liu, J.; Wang, P.; Xu, Y.; Wang, J.; Niu, X.; Yu, L.; Wang, Y.; Shao, F.; Jin, R.; Wang, Y.; Cao, Y. Antigenicity Assessment of SARS-CoV-2 Saltation Variant BA.2.87.1. Emerg Microbes Infect. 2024, 13, 2343909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variant | Mutational landscape |

| BA.1 | A67, T95I, G339D, S371L, S373P, S375F, K417N, N440K,G446S, S477N, T478K, E484A, Q493R, G496S, Q498R,N501Y, Y505H, T547K, D614G, H655Y, N679K, P681H, N764K, D796Y, N856K, Q954H, N969K, L981F |

| BA.2 | T19I, G142D, V213G, G339D, S371F, S373P, S375F, T376A, D405N, R408S, K417N, N440K, S477N, T478K, E484A, Q493R, Q498R, N501Y, Y505H, D614G, H655Y, N679K, P681H, N764K, D796Y, Q954H, N969K |

| BA.4 | T19I, G142D, V213G, G339D, S371F, S373P, S375F, T376A, D405N, R408S, K417N, N440K, L452R, S477N, T478K, E484A, F486V, R493Q reversal, Q498R, N501Y, Y505H, D614G, H655Y, N679K, P681H, N764K, D796Y, Q954H, N969K |

| BA.5 | T19I, LPPA24-27S, Del 69-70, G142D, V213G, G339D, S371F, S373P, S375F, T376A, D405N, R408S, K417N, N440K, L452R, S477N, T478K, E484A, F486V, R493Q reversal, Q498R, N501Y, Y505H, D614G, H655Y, N679K, P681H, N764K, D796Y, Q954H, N969K |

| BQ.1.1 | T19I, LPPA24-27S, H69del, V70del, V213G, G142D, G339D, S371F, S373P, S375F, T376A, D405N, R408S, K417N, N440K, K444T, L452R, N460K, S477N, T478K, E484A, F486V, R493Q reversal, Q498R, N501Y, Y505H, D614G, H655Y, N679K, P681H, N764K, D796Y, Q954H, N969K |

| XBB.1 | T19I, V83A, G142D, Del144, H146Q, Q183E, V213E, G252V, G339H, R346T, L368I, S371F, S373P, S375F, T376A, D405N, R408S, K417N, N440K, V445P, G446S, N460K, S477N, T478K, E484A, F486S, F490S, R493Q reversal, Q498R, N501Y, Y505H, D614G, H655Y, N679K, P681H, N764K, D796Y, Q954H, N969K |

| XBB.1.5 | T19I, V83A, G142D, Del144, H146Q, Q183E, V213E, G252V, G339H, R346T, L368I, S371F, S373P, S375F, T376A, D405N, R408S, K417N, N440K, V445P, G446S,N460K, S477N, T478K, E484A, F486P, F490S, R493Q reversal, Q498R, N501Y, Y505H, D614G, H655Y, N679K, P681H, N764K, D796Y, Q954H, N969K |

| JN.1 | T19I, R21T, S50L, del69-70, V127F, delY144, F157S, R158G, delN211, L213I, L226F, H25N, A264D, I332V, D339H, K356T, R403K, V445H, G446S, N450D, L452W, L455S, N460K, N481K, del V483, A484K, F486P, R493Q, E554K, A570V, P612S, I670V, H68R, D939F, P1143L |

| KP.2 |

JN.1 + S:R346T, S:F456L, S:V1104L T19I, R21T, S50L, del69-70, V127F, delY144, F157S, R158G, delN211, L213I, L226F, H25N, A264D, I332V, D339H, R346T, K356T, R403K, V445H, G446S, N450D, L452W, L455S, F456L, N460K, N481K, del V483, A484K, F486P, R493Q, E554K, A570V, P612S, I670V, H68R, D939F, V1104L, P1143L |

| KP.3 |

JN.1 + S:F456L, S:Q493E, S:V1104L T19I, R21T, S50L, del69-70, V127F, delY144, F157S, R158G, delN211, L213I, L226F, H25N, A264D, I332V, D339H, K356T, R403K, V445H, G446, N450D, L452W, L455S, F456L, N460K, N481K, del V483, A484K, F486P, Q493E, E554K, A570V, P612S, I670V, H68R, D939F, V1104L, P1143L |

| KP.1.1 |

JN.1 + S:F456L, S:R346T, S:K1086R, S:V1104L T19I, R21T, S50L, del69-70, V127F, delY144, F157S, R158G, delN211, L213I, L226F, H25N, A264D, I332V, D339H, R346T, K356T, R403K, V445H, G446, N450D, L452W, L455S, F456L, N460K, N481K, del V483, A484K, F486P, Q493E, E554K, A570V, P612S, H68R, D939F, K1086R, V1104L, P1143L |

| LP.8 |

KP.1.1+ F186L, H445R, Q493E, S31 del T19I, R21T, S31 del, S50L, del69-70, V127F, delY144, F157S, R158G, F186L, delN211, L213I, L226F, H25N, A264D, I332V, D339H, R346T, K356T, R403K, H445R, G446, N450D, L452W, L455S, F456L, N460K, N481K, del V483, A484K, F486P, Q493E, E554K, A570V, P612S, I670V, H68R, D939F, K1086R, V1104L, P1143L |

| LB.1 |

JN.1+ S:S31-, S:Q183H, S:R346T, S:F456L T19I, R21T, S31-, S50L, del69-70, V127F, delY144, F157S, R158G, Q183H, delN211, L213I, L226F, H25N, A264D, I332V, D339H, R346T, K356T, R403K, V445H, G446S, N450D, L452W, L455S, F456L, N460K, N481K, del V483, A484K, F486P, R493Q, E554K, A570V, P612S, I670V, H68R, D939F, P1143L |

| XEC |

JN.1 + S:T22N, S:F59S, S:F456L, S:Q493E, S:V1104L T19I, R21T, T22N, S50L, F59S, del69-70, V127F, delY144, F157S, R158G, delN211, L213I, L226F, H25N, A264D, I332V, D339H, K356T, R403K, V445H, G446S, N450D, L452W, L455S, F456L. N460K, N481K, del V483, A484K, F486P, Q493E, E554K, A570V, P612S, I670V, H68R, D939F, V1104L, P1143L |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).