Submitted:

06 January 2025

Posted:

07 January 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

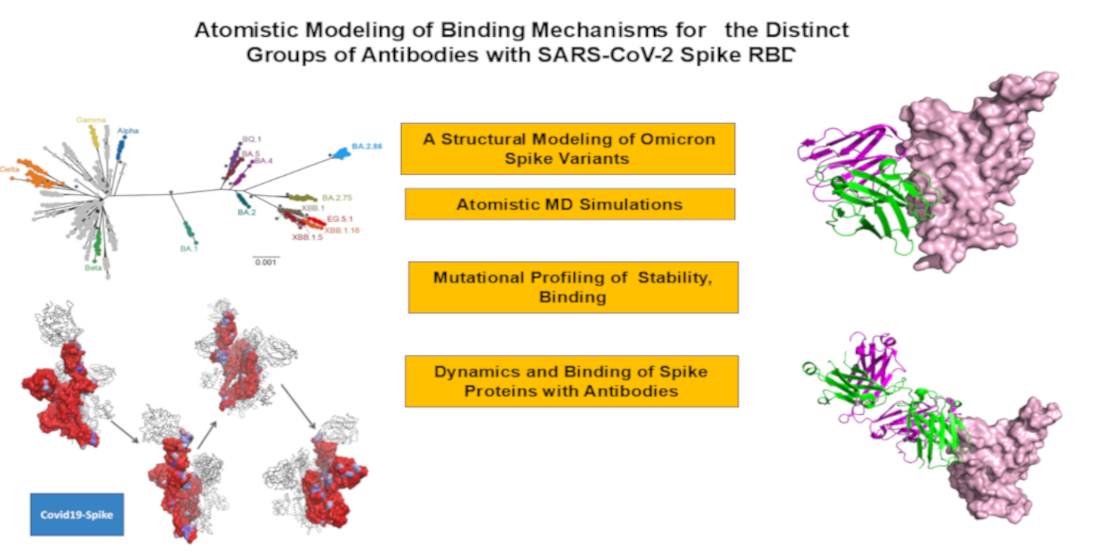

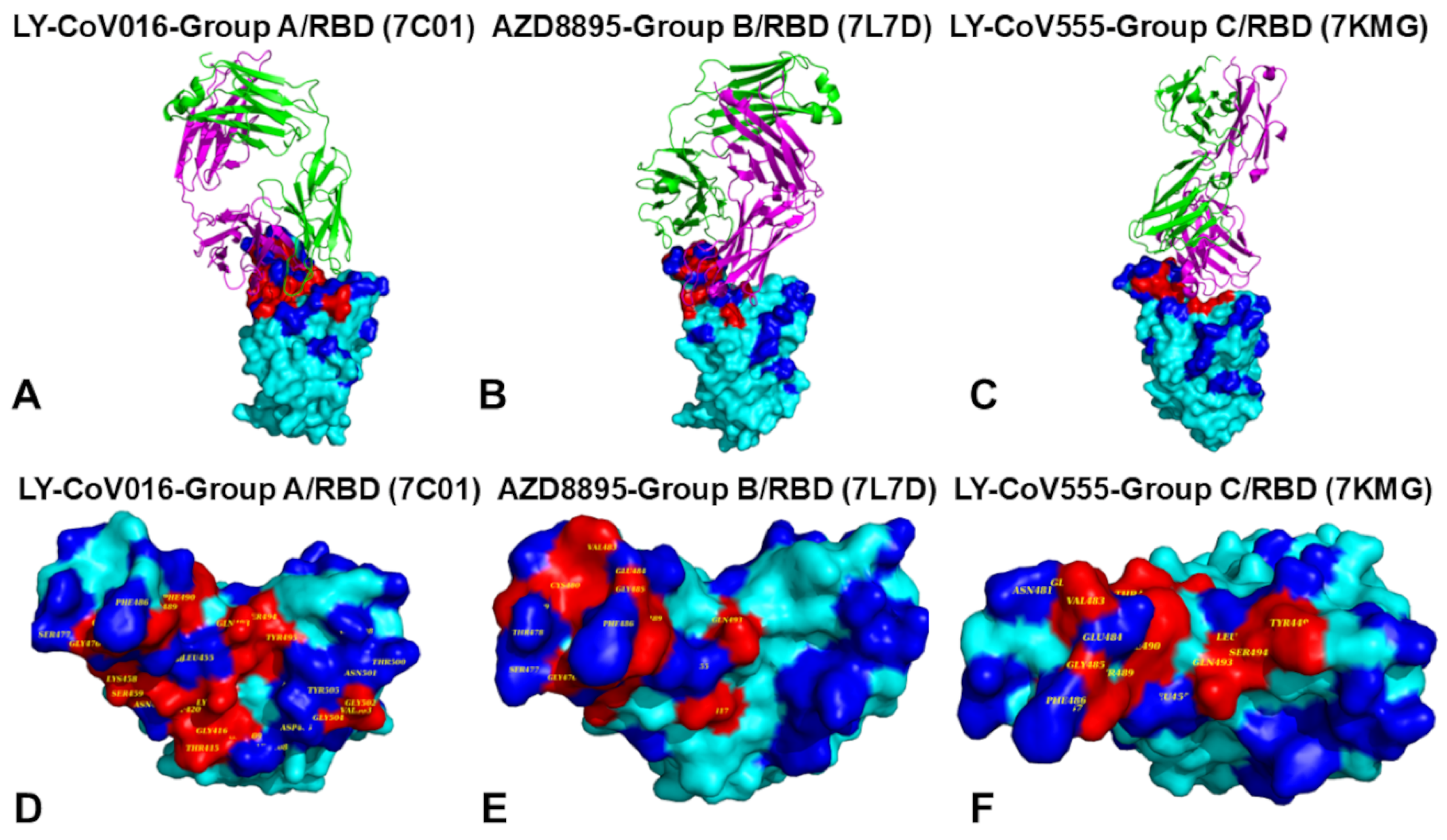

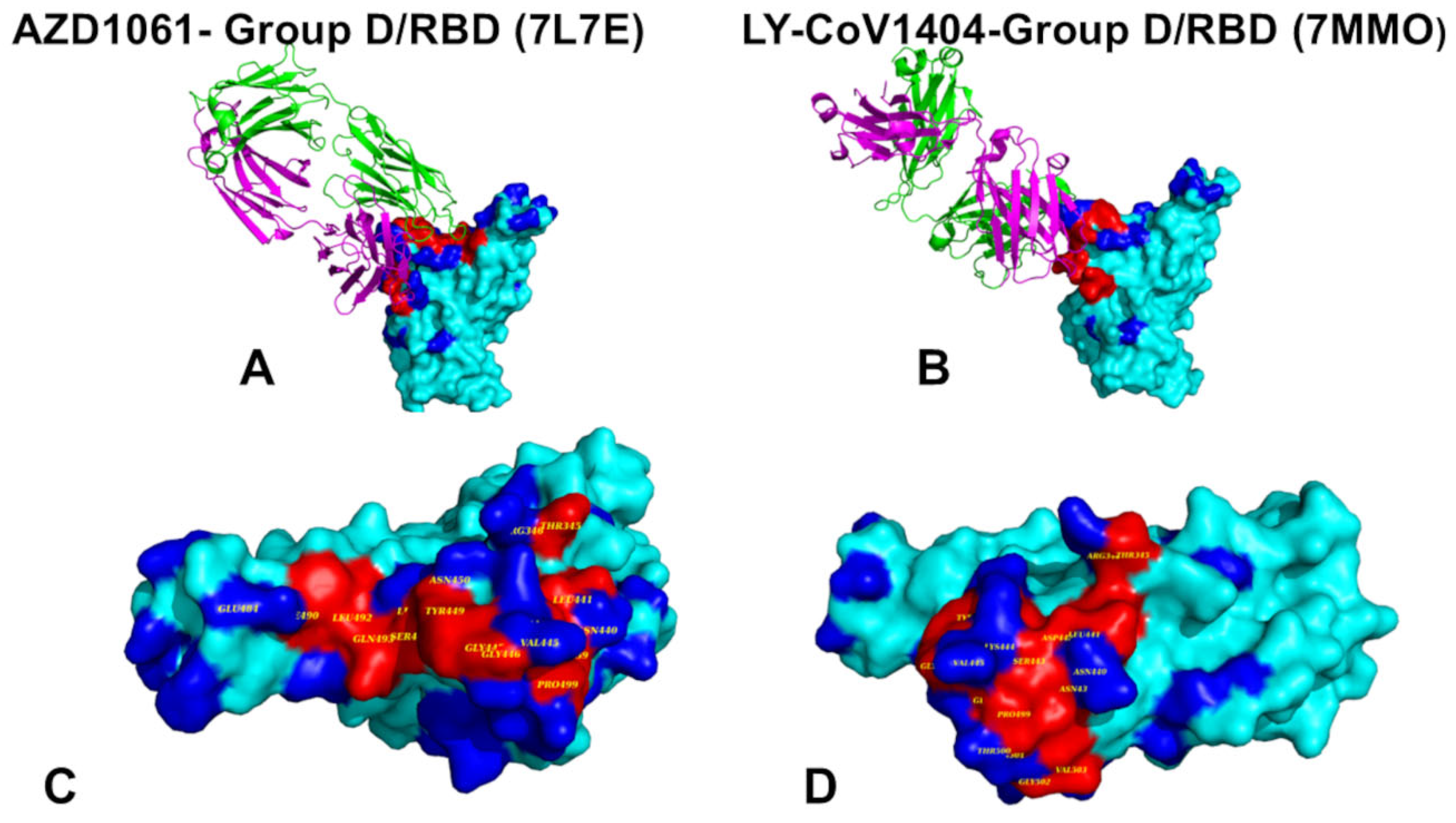

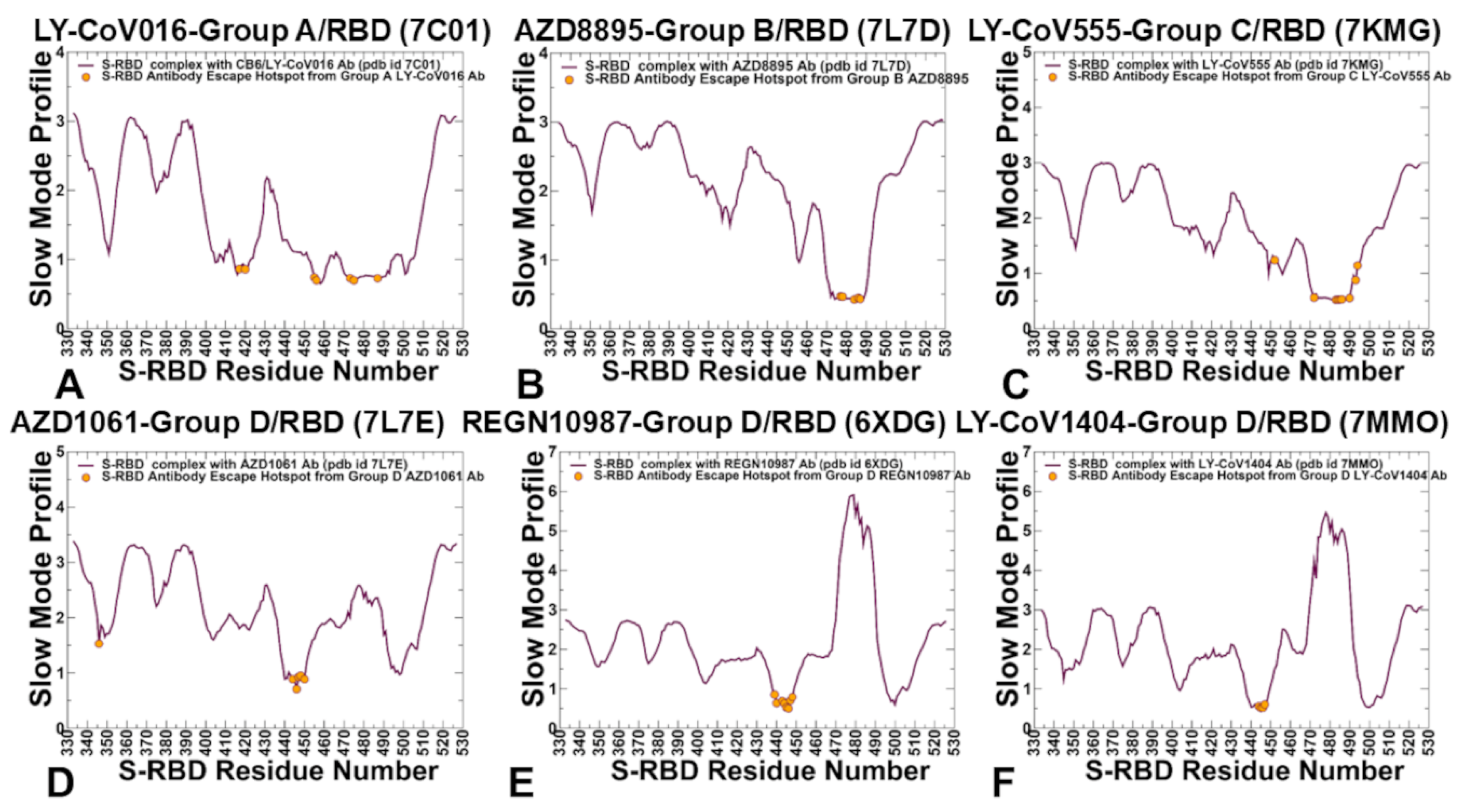

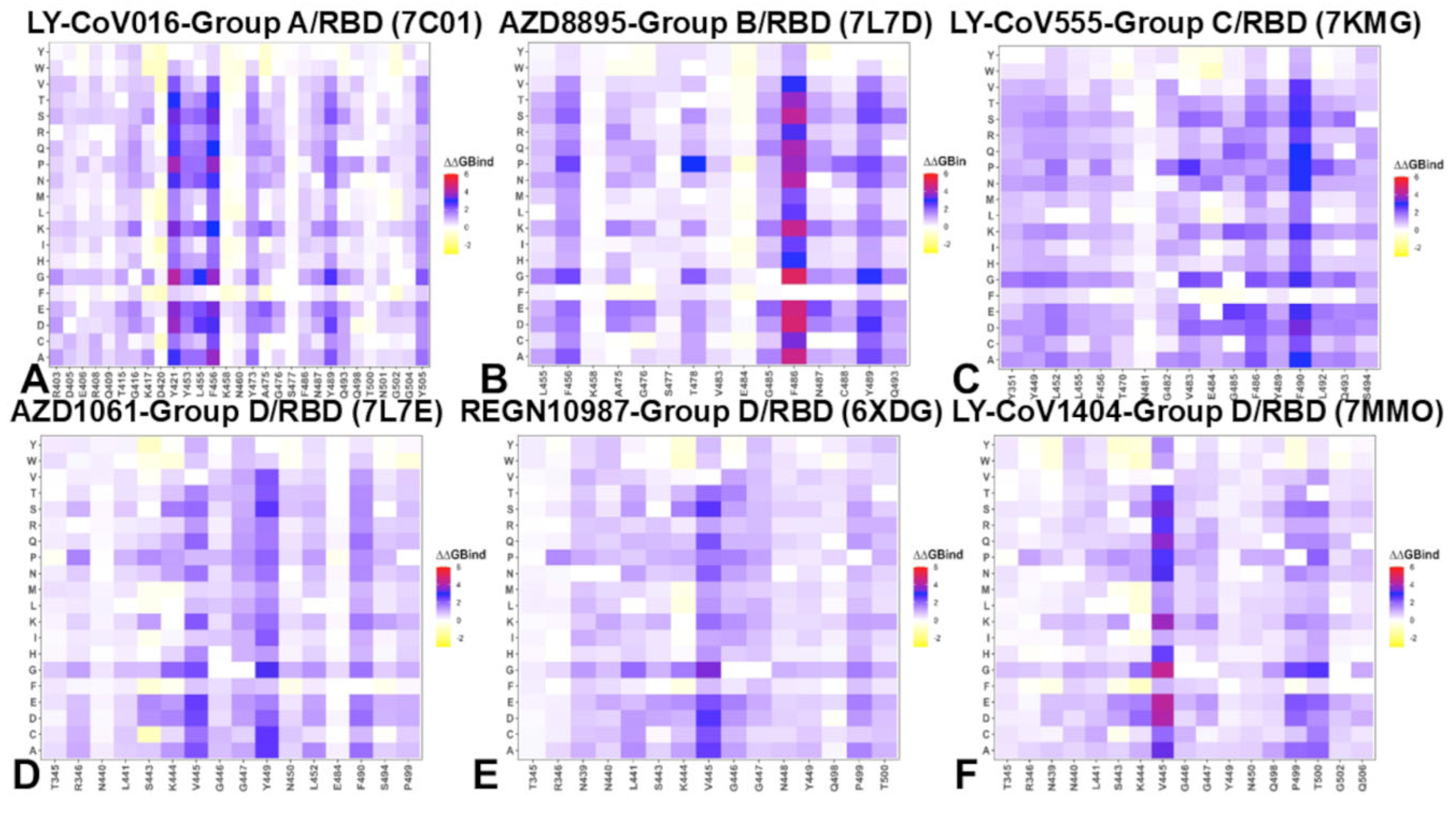

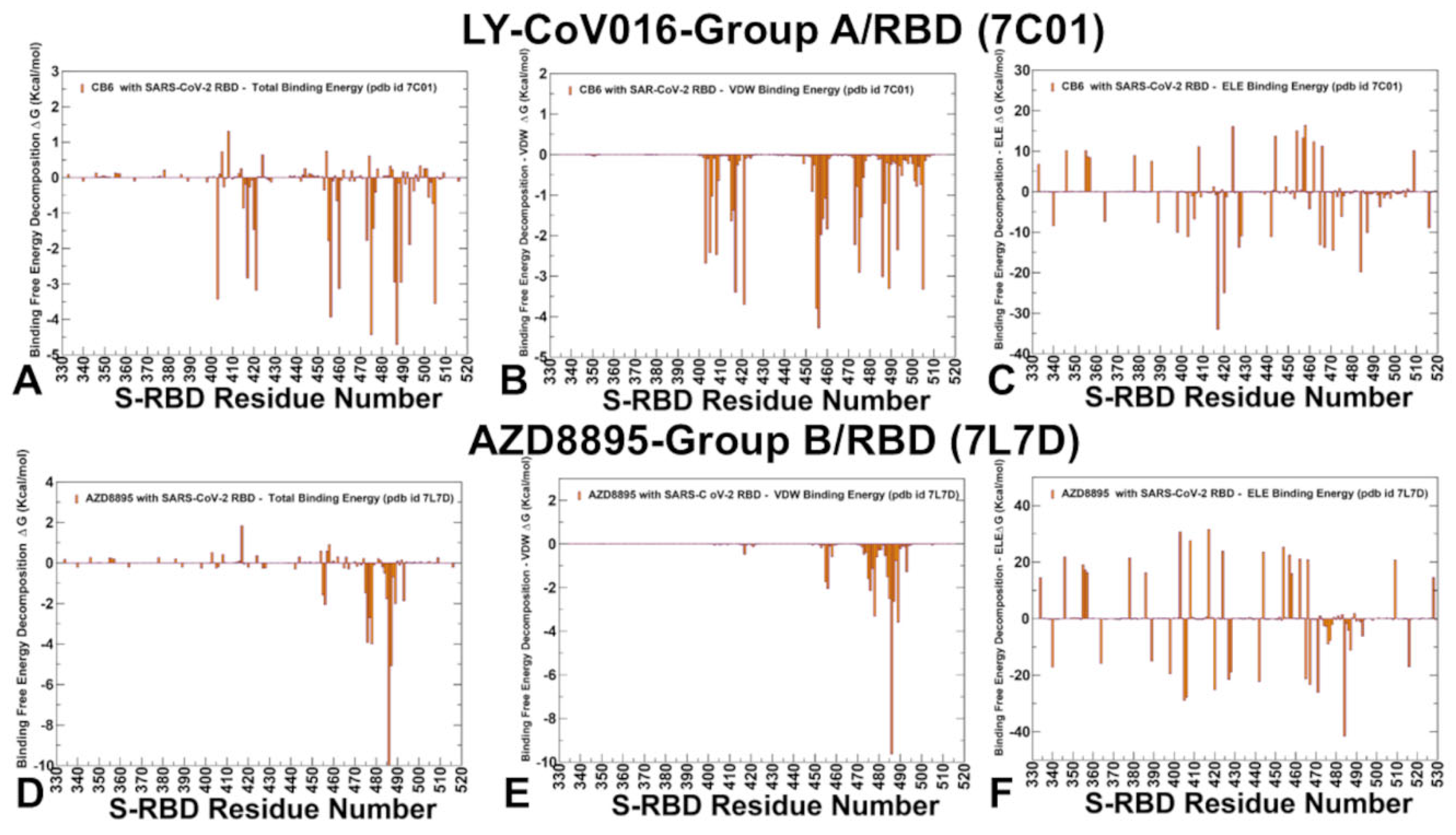

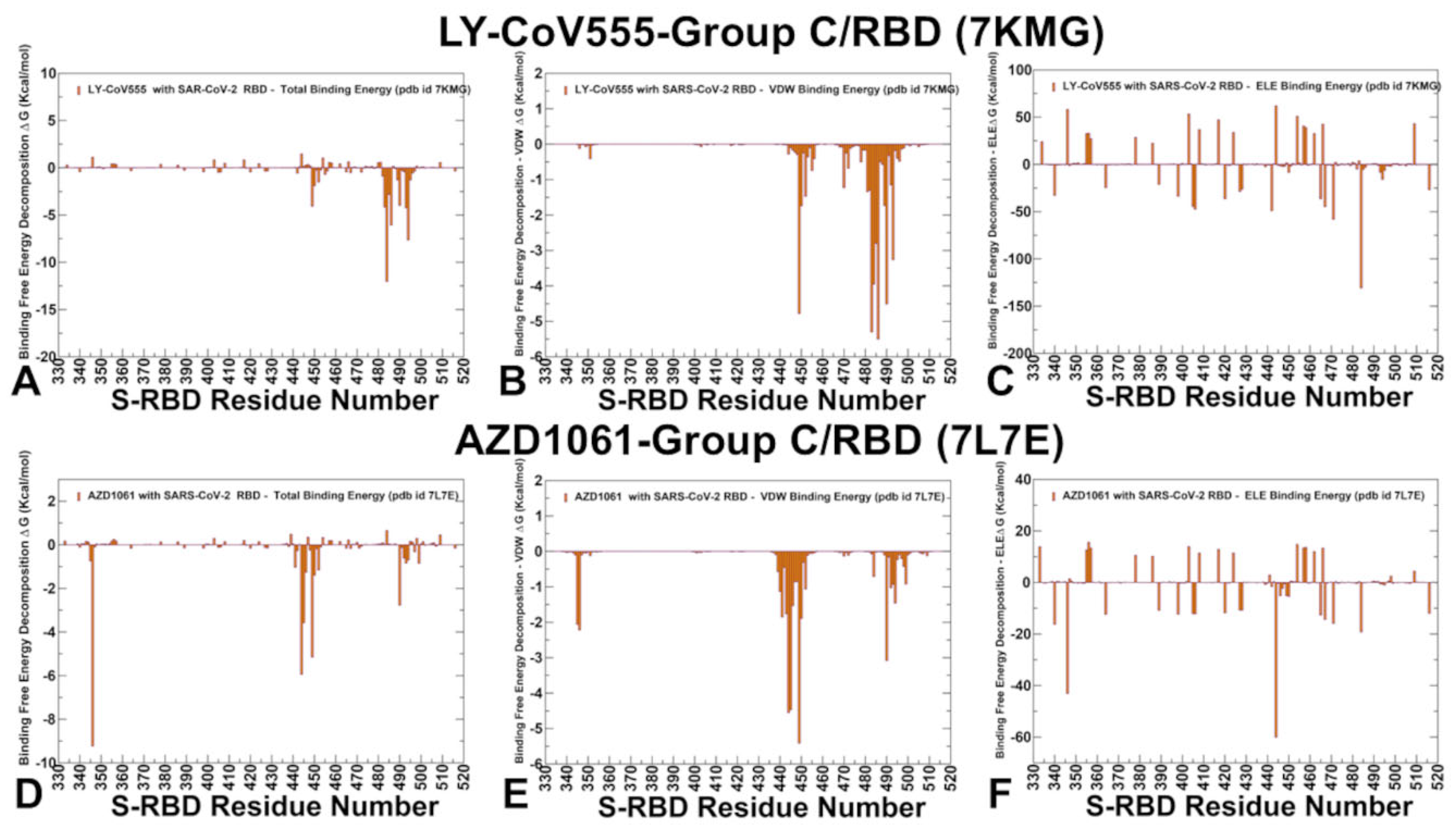

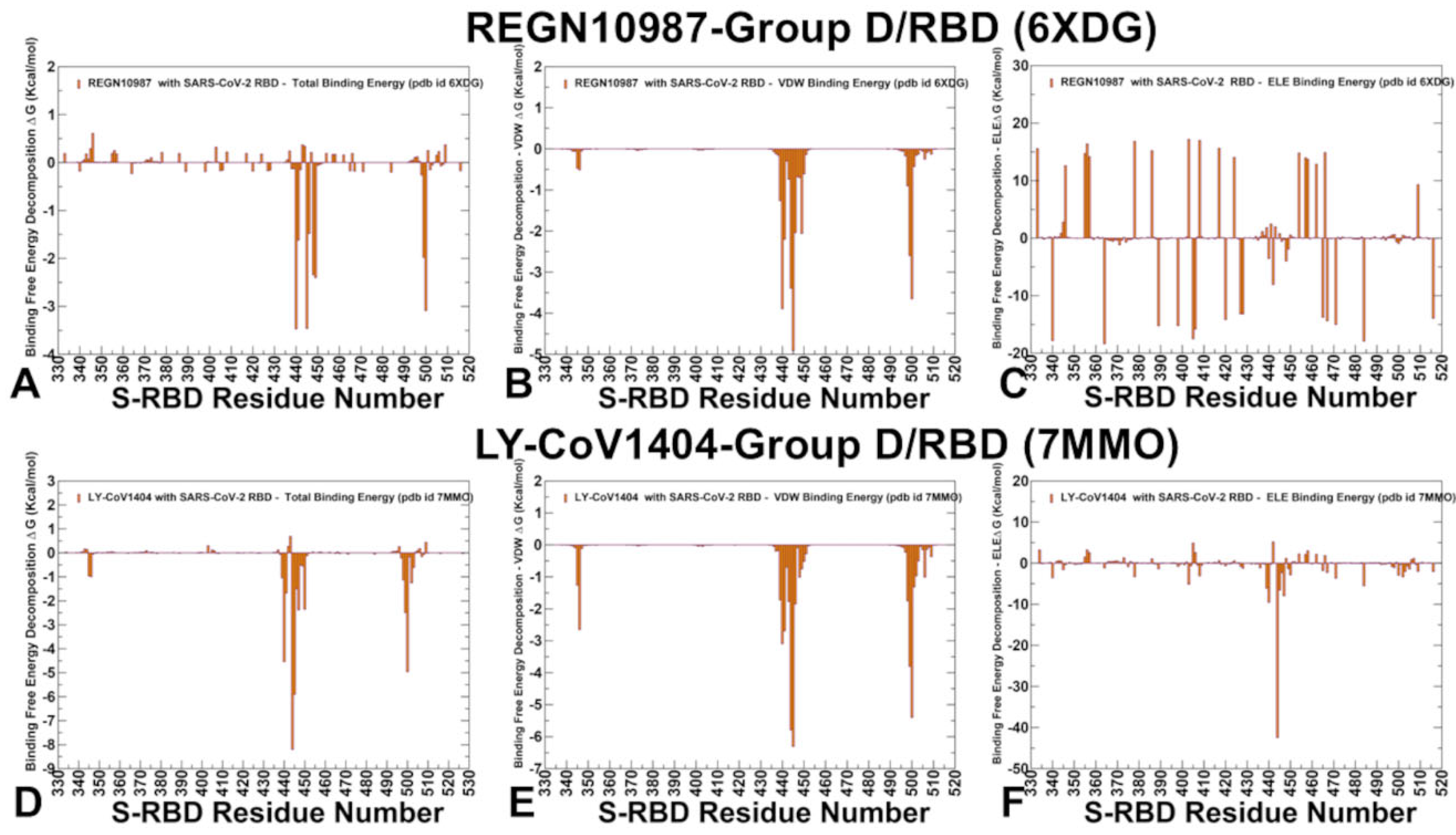

The rapid evolution of SARS-CoV-2 has led to the emergence of variants with increased immune evasion capabilities, posing significant challenges to antibody-based therapeutics and vaccines. In this study, we conducted a comprehensive structural and energetic analysis of SARS-CoV-2 spike receptor-binding domain (RBD) complexes with neutralizing antibodies from four distinct groups (A-D), including group A LY-CoV016, group B AZD8895 and REGN10933, group C LY-CoV555, and group D antibodies AZD1061, REGN10987, and LY-CoV1404. Using coarse-grained simplified simulation models, rapid energy-based mutational scanning, and rigorous MM-GBSA binding free energy calculations, we elucidated the molecular mechanisms of antibody binding and group-specific escape mechanisms, identified key binding hotspots, and explored the evolutionary strategies employed by the virus to evade neutralization The structural analysis and mutational profiling revealed distinct binding mechanisms and epitope specificities for each antibody group, which directly influence their neutralization potency and susceptibility to escape mutations. The MM-GBSA binding free energy analysis identified critical binding hotspots and quantified the contributions of van der Waals and electrostatic interactions to antibody binding. The results showed that key binding hotspots, such as F456, F486, and V445, are dominated by van der Waals interactions, while residues like K417, E484, and K444 contribute significantly through electrostatic interactions. Mutations at these sites, including K417N, E484K, and K444Q, are frequently observed in emerging variants and enable immune evasion by disrupting antibody binding. We identified synergistic effects of van der Waals and electrostatic interactions at key residues K417, F486, and K444 underscore their dual role in binding and immune evasion. Mutations at these sites disrupt both types of interactions, leading to significant reductions in binding affinity and susceptibility to escape mutations. These findings align with experimental data, which identify these residues as dominant escape hotspots. The residue-based decomposition analysis revealed energetic mechanisms and thermodynamic factors underlying the effect of mutations on antibody binding. The results of this energetic analysis demonstrate excellent qualitative agreement between the predicted binding hotspots and critical mutations with respect to the latest experiments on average antibody escape scores. These findings provide valuable insights into the molecular determinants of antibody binding and viral escape, highlighting the importance of targeting conserved epitopes and leveraging combination therapies to mitigate the risk of immune evasion.

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Results

2.1. Structural Analysis of S-RBD Binding with Four Classes of Antibodies A-D

2.2. CG-CABS Simulations and Collective Dynamics Reveal Role of Hinge Sites as Positions of Antibody Escape

2.3. Mutational Profiling of Protein-Antibody Binding Interfaces

2.4. MM-GBSA Analysis of the Binding Affinities

3. Discussion

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Structure Preparation

4.2. Coarse-Grained Molecular Simulations

4.3. All-Atom Molecular Dynamics Simulations

4.2. Binding Free Energy Computations: Mutational Scanning and Sensitivity Analysis

2.3. Binding Free Energy Computations

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| MD | Molecular Dynamics |

| NTD | N-terminal domain |

| RBD | Receptor-Binding Domain |

| VOC | variants of concern |

References

- Tai, W.; He, L.; Zhang, X.; Pu, J.; Voronin, D.; Jiang, S.; Zhou, Y.; Du, L. Characterization of the receptor-binding domain (RBD) of 2019 novel coronavirus: implication for development of RBD protein as a viral attachment inhibitor and vaccine. Cell. Mol. Immunol. 2020, 17, 613–620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Q.; Zhang, Y.; Wu, L.; Niu, S.; Song, C.; Zhang, Z.; Lu, G.; Qiao, C.; Hu, Y.; Yuen, K. Y.; Wang, Q.; Zhou, H.; Yan, J.; Qi, J. Structural and functional basis of SARS-CoV-2 entry by using human ACE2. Cell 2020, 181, 894–904.e9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Walls, A. C.; Park, Y. J.; Tortorici, M. A.; Wall, A.; McGuire, A. T.; Veesler, D. Structure, Function, and Antigenicity of the SARS-CoV-2 Spike Glycoprotein. Cell 2020, 181, 281–292.e6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wrapp, D.; Wang, N.; Corbett, K. S.; Goldsmith, J. A.; Hsieh, C. L.; Abiona, O.; Graham, B. S.; McLellan, J. S. Cryo-EM structure of the 2019-nCoV spike in the prefusion conformation. Science 2020, 367, 1260–1263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, Y.; Zhang, J.; Xiao, T.; Peng, H.; Sterling, S. M.; Walsh, R. M., Jr.; Rawson, S.; Rits-Volloch, S.; Chen, B. Distinct conformational states of SARS-CoV-2 spike protein. Science 2020, 369, 1586–1592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsieh, C. L.; Goldsmith, J. A.; Schaub, J. M.; DiVenere, A. M.; Kuo, H. C.; Javanmardi, K.; Le, K. C.; Wrapp, D.; Lee, A. G.; Liu, Y., Chou, C.W.; Byrne, P.O.; Hjorth, C.K.; Johnson, N.V.; Ludes-Meyers J.; Nguyen, A.W.; Park, J.; Wang, N.; Amengor, D.; Lavinder, J.J.; Ippolito, G.C.; Maynard, J.A.; Finkelstein, I.J.; McLellan, J.S. Structure-based design of prefusion-stabilized SARS-CoV-2 spikes. Science 2020, 369, 1501–1505. [CrossRef]

- Henderson, R.; Edwards, R. J.; Mansouri, K.; Janowska, K.; Stalls, V.; Gobeil, S. M. C.; Kopp, M.; Li, D.; Parks, R.; Hsu, A. L., Borgnia, M.J.; Haynes, B.F.; Acharya, P. Controlling the SARS-CoV-2 spike glycoprotein conformation. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 2020, 27, 925–933. [CrossRef]

- McCallum, M.; Walls, A. C.; Bowen, J. E.; Corti, D.; Veesler, D. Structure-guided covalent stabilization of coronavirus spike glycoprotein trimers in the closed conformation. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 2020, 27, 942–949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiong, X.; Qu, K.; Ciazynska, K. A.; Hosmillo, M.; Carter, A. P.; Ebrahimi, S.; Ke, Z.; Scheres, S. H. W.; Bergamaschi, L.; Grice, G. L., Zhang, Y.; CITIID-NIHR COVID-19 BioResource Collaboration, Nathan, J.A.; Baker, S.; James, L.C.; Baxendale, H.E.; Goodfellow, I.; Doffinger, R.; Briggs, J.A.G. A thermostable, closed SARS-CoV-2 spike protein trimer. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 2020, 27, 934–941. [CrossRef]

- Costello, S.M.; Shoemaker, S.R.; Hobbs, H.T.; Nguyen, A.W.; Hsieh, C.L.; Maynard, J.A.; McLellan, J.S.; Pak, J.E.; Marqusee, S. The SARS-CoV-2 spike reversibly samples an open-trimer conformation exposing novel epitopes. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 2022, 27, 229–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCormick, K.D.; Jacobs, J.L.; Mellors, J.W. The emerging plasticity of SARS-CoV-2. Science 2021, 371, 1306–1308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghimire, D.; Han, Y.; Lu, M. Structural Plasticity and Immune Evasion of SARS-CoV-2 Spike Variants. Viruses 2022, 14, 1255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, C.; Wang, Y.; Liu, C.; Zhang, C.; Han, W.; Hong, X.; Wang, Y.; Hong, Q.; Wang, S.; Zhao, Q.; Wang, Y.; Yang, Y.; Chen, K.; Zheng, W.; Kong, L.; Wang, F.; Zuo, Q.; Huang, Z.; Cong, Y. Conformational dynamics of SARS-CoV-2 trimeric spike glycoprotein in complex with receptor ACE2 revealed by cryo-EM. Sci. Adv. 2021, 7, eabe5575. [CrossRef]

- Benton, D. J.; Wrobel, A. G.; Xu, P.; Roustan, C.; Martin, S. R.; Rosenthal, P. B.; Skehel, J. J.; Gamblin, S. J. Receptor binding and priming of the spike protein of SARS-CoV-2 for membrane fusion. Nature 2020, 588, 327–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turoňová, B.; Sikora, M.; Schuerman, C.; Hagen, W. J. H.; Welsch, S.; Blanc, F. E. C.; von Bülow, S.; Gecht, M.; Bagola, K.; Hörner, C.; van Zandbergen, G.; Landry, J.; de Azevedo, N. T. D.; Mosalaganti, S.; Schwarz, A.; Covino, R.; Mühlebach, M. D.; Hummer, G.; Krijnse Locker, J.; Beck, M. In situ structural analysis of SARS-CoV-2 spike reveals flexibility mediated by three hinges. Science 2020, 370, 203–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, M.; Uchil, P. D.; Li, W.; Zheng, D.; Terry, D. S.; Gorman, J.; Shi, W.; Zhang, B.; Zhou, T.; Ding, S.; Gasser, R.; Prevost, J.; Beaudoin-Bussieres, G.; Anand, S. P.; Laumaea, A.; Grover, J. R.; Lihong, L.; Ho, D. D.; Mascola, J.R.; Finzi, A.; Kwong, P. D.; Blanchard, S. C.; Mothes, W. Real-time conformational dynamics of SARS-CoV-2 spikes on virus particles. Cell Host Microbe 2020, 28, 880–891.e8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Z.; Han, Y.; Ding, S.; Shi, W.; Zhou, T.; Finzi, A.; Kwong, P.D.; Mothes, W.; Lu, M. SARS-CoV-2 Variants Increase Kinetic Stability of Open Spike Conformations as an Evolutionary Strategy. mBio 2022, 13, e0322721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Díaz-Salinas, M.A.; Li, Q.; Ejemel, M.; Yurkovetskiy, L.; Luban, J.; Shen, K.; Wang, Y.; Munro, J.B. Conformational dynamics and allosteric modulation of the SARS-CoV-2 spike. Elife 2022, 11, e75433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Liu, C.; Zhang, C.; Wang, Y.; Hong, Q.; Xu, S.; Li, Z.; Yang, Y.; Huang, Z.; Cong, Y. Structural Basis for SARS-CoV-2 Delta Variant Recognition of ACE2 Receptor and Broadly Neutralizing Antibodies. Nat. Commun. 2022, 13, 871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mannar, D.; Saville, J.W.; Zhu, X.; Srivastava, S.S.; Berezuk, A.M.; Tuttle, K.S.; Marquez, A.C.; Sekirov, I.; Subramaniam, S. SARS-CoV-2 Omicron Variant: Ab Evasion and Cryo-EM Structure of Spike Protein–ACE2 Complex. Science 2022, 375, 760–764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, Q.; Han, W.; Li, J.; Xu, S.; Wang, Y.; Xu, C.; Li, Z.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, C.; Huang, Z.; Cong, Y. Molecular Basis of Receptor Binding and Ab Neutralization of Omicron. Nature 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCallum, M.; Czudnochowski, N.; Rosen, L.E.; Zepeda, S.K.; Bowen, J.E.; Walls, A.C.; Hauser, K.; Joshi, A.; Stewart, C.; Dillen, J.R.; Powell, A.E.; Croll, T.I.; Nix, J.; Virgin, H.W.; Corti, D.; Snell, G.; Veesler, D. Structural Basis of SARS-CoV-2 Omicron Immune Evasion and Receptor Engagement. Science 2022, 375, 864–868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, W.; Xu, Y.; Xu, P.; Cao, X.; Wu, C.; Gu, C.; He, X.; Wang, X.; Huang, S.; Yuan, Q.; Wu, K.; Hu, W.; Huang, Z.; Liu, J.; Wang, Z.; Jia, F.; Xia, K.; Liu, P.; Wang, X.; Song, B.; Zheng, J.; Jiang, H.; Cheng, X.; Jiang, Y.; Deng, S.J.; Xu, H.E. Structures of the Omicron Spike Trimer with ACE2 and an Anti-Omicron Ab. Science 2022, 375, 1048–1053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gobeil, S. M.-C.; Henderson, R.; Stalls, V.; Janowska, K.; Huang, X.; May, A.; Speakman, M.; Beaudoin, E.; Manne, K.; Li, D.; Parks, R.; Barr, M.; Deyton, M.; Martin, M.; Mansouri, K.; Edwards, R. J.; Eaton, A.; Montefiori, D. C.; Sempowski, G. D.; Saunders, K. O.; Wiehe, K.; Williams, W.; Korber, B.; Haynes, B. F.; Acharya, P. Structural Diversity of the SARS-CoV-2 Omicron Spike. Mol Cell. 2022, 82, 2050–2068.e6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, Z.; Liu, P.; Wang, N.; Wang, L.; Fan, K.; Zhu, Q.; Wang, K.; Chen, R.; Feng, R.; Jia, Z.; Yang, M.; Xu, G.; Zhu, B.; Fu, W.; Chu, T.; Feng, L.; Wang, Y.; Pei, X.; Yang, P.; Xie, X.S.; Cao, L.; Cao, Y.; Wang, X. Structural and Functional Characterizations of Infectivity and Immune Evasion of SARS-CoV-2 Omicron. Cell 2022, 185, 860–871.e13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.; Guo, Y.; Liu, L.; Schwanz, L. T.; Li, Z.; Nair, M. S.; Ho, J.; Zhang, R. M.; Iketani, S.; Yu, J.; Huang, Y.; Qu, Y.; Valdez, R.; Lauring, A. S.; Huang, Y.; Gordon, A.; Wang, H. H.; Liu, L.; Ho, D. D. Antigenicity and Receptor Affinity of SARS-CoV-2 BA.2.86 Spike. Nature 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, S.; Yu, Y.; Jian, F.; Song, W.; Yisimayi, A.; Chen, X.; Xu, Y.; Wang, P.; Wang, J.; Yu, L.; Niu, X.; Wang, J.; Xiao, T.; An, R.; Wang, Y.; Gu, Q.; Shao, F.; Jin, R.; Shen, Z.; Wang, Y.; Cao, Y. Antigenicity and Infectivity Characterization of SARS-CoV-2 BA.2.86. Lancet Infect Dis. 2023, 23, e457–e459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tamura, T.; Mizuma, K.; Nasser, H.; Deguchi, S.; Padilla-Blanco, M.; Oda, Y.; Uriu, K.; Tolentino, J. E. M.; Tsujino, S.; Suzuki, R.; Kojima, I.; Nao, N.; Shimizu, R.; Wang, L.; Tsuda, M.; Jonathan, M.; Kosugi, Y.; Guo, Z.; Hinay, A. A., Jr.; Putri, O.; Kim, Y.; Tanaka, Y. L.; Asakura, H.; Nagashima, M.; Sadamasu, K.; Yoshimura, K.; Saito, A.; Ito, J.; Irie, T.; Tanaka, S.; Zahradnik, J.; Ikeda, T.; Takayama, K.; Matsuno, K.; Fukuhara, T.; Sato, K. Virological Characteristics of the SARS-CoV-2 BA.2.86 Variant. Cell Host Microbe. 2024, 32, 170–180.e12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.; Zhou, D.; Dijokaite-Guraliuc, A.; Supasa, P.; Duyvesteyn, H. M. E.; Ginn, H. M.; Selvaraj, M.; Mentzer, A. J.; Das, R.; de Silva, T. I.; Ritter, T. G.; Plowright, M.; Newman, T. A. H.; Stafford, L.; Kronsteiner, B.; Temperton, N.; Lui, Y.; Fellermeyer, M.; Goulder, P.; Klenerman, P.; Dunachie, S. J.; Barton, M. I.; Kutuzov, M. A.; Dushek, O.; Fry, E. E.; Mongkolsapaya, J.; Ren, J.; Stuart, D. I.; Screaton, G. R. A Structure-Function Analysis SARS-CoV-2 BA.2.86 Balances Ab Escape and ACE2 Affinity. Cell Rep Med. 2024, 5, 101553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, K.; Lustig, G.; Römer, C.; Reedoy, K.; Jule, Z.; Karim, F.; Ganga, Y.; Bernstein, M.; Baig, Z.; Jackson, L.; Mahlangu, B.; Mnguni, A.; Nzimande, A.; Stock, N.; Kekana, D.; Ntozini, B.; van Deventer, C.; Marshall, T.; Manickchund, N.; Gosnell, B. I.; Lessells, R. J.; Karim, Q. A.; Abdool Karim, S. S.; Moosa, M.-Y. S.; de Oliveira, T.; von Gottberg, A.; Wolter, N.; Neher, R. A.; Sigal, A. Evolution and Neutralization Escape of the SARS-CoV-2 BA.2.86 Subvariant. Nat Commun. 2023, 14, 8078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, S.; Yu, Y.; Xu, Y.; Jian, F.; Song, W.; Yisimayi, A.; Wang, P.; Wang, J.; Liu, J.; Yu, L.; Niu, X.; Wang, J.; Wang, Y.; Shao, F.; Jin, R.; Wang, Y.; Cao, Y. Fast Evolution of SARS-CoV-2 BA.2.86 to JN.1 under Heavy Immune Pressure. Lancet Infect Dis. 2024, 24, e70–e72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaku, Y.; Okumura, K.; Padilla-Blanco, M.; Kosugi, Y.; Uriu, K.; Hinay, A. A., Jr; Chen, L.; Plianchaisuk, A.; Kobiyama, K.; Ishii, K. J.; Zahradnik, J.; Ito, J.; Sato, K., K. Virological Characteristics of the SARS-CoV-2 JN.1 Variant. Lancet Infect Dis. 2024, 24, e82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.; Mellis, I. A.; Ho, J.; Bowen, A.; Kowalski-Dobson, T.; Valdez, R.; Katsamba, P. S.; Wu, M.; Lee, C.; Shapiro, L.; Gordon, A.; Guo, Y.; Ho, D. D.; Liu, L. Recurrent SARS-CoV-2 Spike Mutations Confer Growth Advantages to Select JN.1 Sublineages. Emerg Microbes Infect. 2024, 13, 2402880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, H.; Guo, H.; Wang, A.; Cao, L.; Fan, Q.; Jiang, J.; Wang, M.; Lin, L.; Ge, X.; Wang, H.; Zhang, R.; Liao, M.; Yan, R.; Ju, B.; Zhang, Z. Structural Basis for the Evolution and Antibody Evasion of SARS-CoV-2 BA.2.86 and JN.1 Subvariants. Nat Commun. 2024, 15, 7715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L.; Shi, K.; Gu, Y.; Xu, Z.; Shu, C.; Li, D.; Sun, J.; Cong, M.; Li, X.; Zhao, X.; Yu, G.; Hu, S.; Tan, H.; Qi, J.; Ma, X.; Liu, K.; Gao, G. F. Spike Structures, Receptor Binding, and Immune Escape of Recently Circulating SARS-CoV-2 Omicron BA.2.86, JN.1, EG.5, EG.5.1, and HV.1 Sub-Variants. Structure 2024, 32, 1055–1067.e6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, P.; Faraone, J. N.; Hsu, C. C.; Chamblee, M.; Zheng, Y.-M.; Carlin, C.; Bednash, J. S.; Horowitz, J. C.; Mallampalli, R. K.; Saif, L. J.; Oltz, E. M.; Jones, D.; Li, J.; Gumina, R. J.; Xu, K.; Liu, S.-L. Neutralization Escape, Infectivity, and Membrane Fusion of JN.1-Derived SARS-CoV-2 SLip, FLiRT, and KP.2 Variants. Cell Rep. 2024, 43, 114520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kaku, Y.; Uriu, K.; Kosugi, Y.; Okumura, K.; Yamasoba, D.; Uwamino, Y.; Kuramochi, J.; Sadamasu, K.; Yoshimura, K.; Asakura, H.; Nagashima, M.; Ito, J.; Sato, K. Virological Characteristics of the SARS-CoV-2 KP.2 Variant. Lancet Infect Dis. 2024, 24, e416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, K.; An, Y.; Liu, X.; Xie, H.; Li, D.; Yang, T.; Duan, M.; Wang, Y.; Zhao, X.; Dai, L.; Gao, G. F. Neutralization of SARS-CoV-2 KP.1, KP.1.1, KP.2 and KP.3 by Human and Murine Sera. NPJ Vaccines 2024, 9, 215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaku, Y.; Yo, M. S.; Tolentino, J. E.; Uriu, K.; Okumura, K.; Ito, J.; Sato, K. Virological Characteristics of the SARS-CoV-2 KP.3, LB.1, and KP.2.3 Variants. Lancet Infect Dis. 2024, 24, e482–e483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaku, Y.; Uriu, K.; Okumura, K.; Ito, J.; Sato, K. Virological Characteristics of the SARS-CoV-2 KP.3.1.1 Variant. Lancet Infect Dis. 2024, 24, e609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, Z.; Huang, J.; Baboo, S.; Diedrich, J. K.; Bangaru, S.; Paulson, J. C.; Yates, J. R., III; Yuan, M.; Wilson, I. A.; Ward, A. B. Structural and Functional Insights into the Evolution of SARS-CoV-2 KP.3.1.1 Spike Protein. bioRxiv 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaku, Y.; Okumura, K.; Kawakubo, S.; Uriu, K.; Chen, L.; Kosugi, Y.; Uwamino, Y.; Begum, M. M.; Leong, S.; Ikeda, T.; Sadamasu, K.; Asakura, H.; Nagashima, M.; Yoshimura, K.; Ito, J.; Sato, K. Virological Characteristics of the SARS-CoV-2 XEC Variant. Lancet Infect Dis. 2024, 24, e736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Yu, Y.; Jian, F.; Yang, S.; Song, W.; Wang, P.; Yu, L.; Shao, F.; Cao, Y. Enhanced Immune Evasion of SARS-CoV-2 Variants KP.3.1.1 and XEC through N-Terminal Domain Mutations. Lancet Infect Dis 2024, S1473-3099(24)00738-2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gavor, E.; Choong, Y. K.; Er, S. Y.; Sivaraman, H.; Sivaraman, J. Structural Basis of SARS-CoV-2 and SARS-CoV Antibody Interactions. Trends Immunol 2020, 41, 1006–1022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barnes, C. O.; Jette, C. A.; Abernathy, M. E.; Dam, K. A.; Esswein, S. R.; Gristick, H. B.; Malyutin, A. G.; Sharaf, N. G.; Huey-Tubman, K. E.; Lee, Y. E.; et al. SARS-CoV-2 neutralizing antibody structures inform therapeutic strategies. Nature 2020, 588, 682–687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brouwer, P. J. M.; Caniels, T. G.; van der Straten, K.; Snitselaar, J. L.; Aldon, Y.; Bangaru, S.; Torres, J. L.; Okba, N. M. A.; Claireaux, M.; Kerster, G.; et al. Potent neutralizing antibodies from COVID-19 patients define multiple targets of vulnerability. Science 2020, 369, 643–650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dejnirattisai, W.; Zhou, D.; Ginn, H. M.; Duyvesteyn, H. M. E.; Supasa, P.; Case, J. B.; Zhao, Y.; Walter, T. S.; Mentzer, A. J.; Liu, C.; et al. The antigenic anatomy of SARS-CoV-2 receptor binding domain. Cell 2021, 184, 2183–2200.e2122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hastie, K. M.; Li, H.; Bedinger, D.; Schendel, S. L.; Dennison, S. M.; Li, K.; Rayaprolu, V.; Yu, X.; Mann, C.; Zandonatti, M.; et al. Defining variant-resistant epitopes targeted by SARS-CoV-2 antibodies: A global consortium study. Science 2021, 374, 472–478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mittal, A.; Khattri, A.; Verma, V. Structural and antigenic variations in the spike protein of emerging SARS-CoV-2 variants. PLoS Pathog. 2022, 18, e1010260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niu, L.; Wittrock, K.N.; Clabaugh, G.C.; Srivastava, V.; Cho, M.W. A Structural Landscape of Neutralizing Antibodies Against SARS-CoV-2 Receptor Binding Domain. Front Immunol. 2021, 12, 647934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harvey, W.T.; Carabelli, A.M.; Jackson B, Gupta RK, Thomson EC, Harrison EM, Ludden C, Reeve R, Rambaut A; COVID-19 Genomics UK (COG-UK) Consortium, et al. SARS-CoV-2 variants, spike mutations and immune escape. Nat Rev Microbiol 2021, 19, 409–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deshpande, A.; Harris, B.D.; Martinez-Sobrido, L.; Kobie, J.J.; Walter, M.R. Epitope Classification and RBD Binding Properties of Neutralizing Antibodies Against SARS-CoV-2 Variants of Concern. Front Immunol. 2021, 12, 691715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, M.; Huang, D.; Lee, C.-C. D.; Wu, N. C.; Jackson, A. M.; Zhu, X.; Liu, H.; Peng, L.; van Gils, M. J.; Sanders, R. W.; Burton, D. R.; Reincke, S. M.; Prüss, H.; Kreye, J.; Nemazee, D.; Ward, A. B.; Wilson, I. A. Structural and Functional Ramifications of Antigenic Drift in Recent SARS-CoV-2 Variants. Science 2021, 373, 818–823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pinto, D.; Park, Y.-J.; Beltramello, M.; Walls, A. C.; Tortorici, M. A.; Bianchi, S.; Jaconi, S.; Culap, K.; Zatta, F.; De Marco, A.; Peter, A.; Guarino, B.; Spreafico, R.; Cameroni, E.; Case, J. B.; Chen, R. E.; Havenar-Daughton, C.; Snell, G.; Telenti, A.; Virgin, H. W.; Lanzavecchia, A.; Diamond, M. S.; Fink, K.; Veesler, D.; Corti, D. Cross-Neutralization of SARS-CoV-2 by a Human Monoclonal SARS-CoV Antibody. Nature 2020, 583, 290–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tortorici, M. A.; Beltramello, M.; Lempp, F. A.; Pinto, D.; Dang, H. V.; Rosen, L. E.; McCallum, M.; Bowen, J.; Minola, A.; Jaconi, S.; et al. Ultrapotent human antibodies protect against SARS-CoV-2 challenge via multiple mechanisms. Science 2020, 370, 950–957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Starr, T. N.; Greaney, A. J.; Dingens, A. S.; Bloom, J. D. Complete Map of SARS-CoV-2 RBD Mutations That Escape the Monoclonal Antibody LY-CoV555 and Its Cocktail with LY-CoV016. Cell Rep Med. 2021, 2, 100255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greaney, A.J.; Loes, A.N.; Crawford, K.H.D.; Starr, T.N.; Malone, K.D.; Chu, H.Y.; Bloom, J.D. Comprehensive mapping of mutations to the SARS-CoV-2 receptor-binding domain that affect recognition by polyclonal human serum antibodies. Cell Host Microbe 2021, 29, 463–476.e6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greaney, A.J.; Starr, T.N.; Barnes, C.O.; Weisblum, Y.; Schmidt, F.; Caskey, M.; Gaebler, C.; Cho, A.; Agudelo, M.; Finkin, S.; et al. Mapping mutations to the SARS-CoV-2 RBD that escape binding by different classes of antibodies. Nat. Commun. 2021, 12, 4196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, Y.; Wang, J.; Jian, F.; Xiao, T.; Song, W.; Yisimayi, A.; Huang, W.; Li, Q.; Wang, P.; An, R.; Wang, J.; Wang, Y.; Niu, X.; Yang, S.; Liang, H.; Sun, H.; Li, T.; Yu, Y.; Cui, Q.; Liu, S.; Yang, X.; Du, S.; Zhang, Z.; Hao, X.; Shao, F.; Jin, R.; Wang, X.; Xiao, J.; Wang, Y.; Xie, X. S. Omicron Escapes the Majority of Existing SARS-CoV-2 Neutralizing Antibodies. Nature 2022, 602, 657–663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, Y.; Yisimayi, A.; Jian, F.; Song, W.; Xiao, T.; Wang, L.; Du, S.; Wang, J.; Li, Q.; Chen, X.; Yu, Y.; Wang, P.; Zhang, Z.; Liu, P.; An, R.; Hao, X.; Wang, Y.; Wang, J.; Feng, R.; Sun, H.; Zhao, L.; Zhang, W.; Zhao, D.; Zheng, J.; Yu, L.; Li, C.; Zhang, N.; Wang, R.; Niu, X.; Yang, S.; Song, X.; Chai, Y.; Hu, Y.; Shi, Y.; Zheng, L.; Li, Z.; Gu, Q.; Shao, F.; Huang, W.; Jin, R.; Shen, Z.; Wang, Y.; Wang, X.; Xiao, J.; Xie, X. S. BA. 2.12.1, BA.4 and BA.5 Escape Antibodies Elicited by Omicron Infection. Nature 2022, 608, 593–602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, Y.; Jian, F.; Wang, J.; Yu, Y.; Song, W.; Yisimayi, A.; Wang, J.; An, R.; Chen, X.; Zhang, N.; Wang, Y.; Wang, P.; Zhao, L.; Sun, H.; Yu, L.; Yang, S.; Niu, X.; Xiao, T.; Gu, Q.; Shao, F.; Hao, X.; Xu, Y.; Jin, R.; Shen, Z.; Wang, Y.; Xie, X. S. Imprinted SARS-CoV-2 Humoral Immunity Induces Convergent Omicron RBD Evolution. Nature 2023, 614, 521–529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yisimayi, A.; Song, W.; Wang, J.; Jian, F.; Yu, Y.; Chen, X.; Xu, Y.; Yang, S.; Niu, X.; Xiao, T.; Wang, J.; Zhao, L.; Sun, H.; An, R.; Zhang, N.; Wang, Y.; Wang, P.; Yu, L.; Lv, Z.; Gu, Q.; Shao, F.; Jin, R.; Shen, Z.; Xie, X. S.; Wang, Y.; Cao, Y. Repeated Omicron Exposures Override Ancestral SARS-CoV-2 Immune Imprinting. Nature 2024, 625, 148–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jian, F.; Wang, J.; Yisimayi, A.; Song, W.; Xu, Y.; Chen, X.; Niu, X.; Yang, S.; Yu, Y.; Wang, P.; Sun, H.; Yu, L.; Wang, J.; Wang, Y.; An, R.; Wang, W.; Ma, M.; Xiao, T.; Gu, Q.; Shao, F.; Wang, Y.; Shen, Z.; Jin, R.; Cao, Y. Evolving Antibody Response to SARS-CoV-2 Antigenic Shift from XBB to JN.1. Nature 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cao, Y.; Jian, F.; Zhang, Z.; Yisimayi, A.; Hao, X.; Bao, L.; Yuan, F.; Yu, Y.; Du, S.; Wang, J.; Xiao, T.; Song, W.; Zhang, Y.; Liu, P.; An, R.; Wang, P.; Wang, Y.; Yang, S.; Niu, X.; Zhang, Y.; Gu, Q.; Shao, F.; Hu, Y.; Yin, W.; Zheng, A.; Wang, Y.; Qin, C.; Jin, R.; Xiao, J.; Xie, X. S. Rational Identification of Potent and Broad Sarbecovirus-Neutralizing Antibody Cocktails from SARS Convalescents. Cell Rep. 2022, 41, 111845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yu, L.; Wang, Y.; Liu, Y.; Xing, X.; Li, C.; Wang, X.; Shi, J.; Ma, W.; Li, J.; Chen, Y.; Qiao, R.; Zhao, X.; Gao, M.; Wen, S.; Xue, Y.; Guan, Y.; Chu, H.; Sun, L.; Wang, P. Potent and Broadly Neutralizing Antibodies against Sarbecoviruses Elicited by Single Ancestral SARS-CoV-2 Infection. bioRxiv 2024, 2024.06.06.597720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosen, L. E.; Tortorici, M. A.; De Marco, A.; Pinto, D.; Foreman, W. B.; Taylor, A. L.; Park, Y.-J.; Bohan, D.; Rietz, T.; Errico, J. M.; Hauser, K.; Dang, H. V.; Chartron, J. W.; Giurdanella, M.; Cusumano, G.; Saliba, C.; Zatta, F.; Sprouse, K. R.; Addetia, A.; Zepeda, S. K.; Brown, J.; Lee, J.; Dellota, E., Jr.; Rajesh, A.; Noack, J.; Tao, Q.; DaCosta, Y.; Tsu, B.; Acosta, R.; Subramanian, S.; de Melo, G. D.; Kergoat, L.; Zhang, I.; Liu, Z.; Guarino, B.; Schmid, M. A.; Schnell, G.; Miller, J. L.; Lempp, F. A.; Czudnochowski, N.; Cameroni, E.; Whelan, S. P. J.; Bourhy, H.; Purcell, L. A.; Benigni, F.; di Iulio, J.; Pizzuto, M. S.; Lanzavecchia, A.; Telenti, A.; Snell, G.; Corti, D.; Veesler, D.; Starr, T. N. A Potent Pan-Sarbecovirus Neutralizing Antibody Resilient to Epitope Diversification. Cell 2024, 187, 7196–7213.e26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jian, F.; Wec, A. Z.; Feng, L.; Yu, Y.; Wang, L.; Wang, P.; Yu, L.; Wang, J.; Hou, J.; Berrueta, D. M.; Lee, D.; Speidel, T.; Ma, L.; Kim, T.; Yisimayi, A.; Song, W.; Wang, J.; Liu, L.; Yang, S.; Niu, X.; Xiao, T.; An, R.; Wang, Y.; Shao, F.; Wang, Y.; Henry, C.; Pecetta, S.; Wang, X.; Walker, L. M.; Cao, Y. A Generalized Framework to Identify SARS-CoV-2 Broadly Neutralizing Antibodies. bioRxiv 2024, 2024.04.16.589454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zimmerman, M.I.; Porter, J.R.; Ward, M.D.; Singh, S.; Vithani, N.; Meller, A.; Mallimadugula, U.L.; Kuhn, C.E.; Borowsky, J.H.; Wiewiora, R.P.; et al. SARS-CoV-2 simulations go exascale to predict dramatic spike opening and cryptic pockets across the proteome. Nat. Chem. 2021, 13, 651–659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mansbach, R.A.; Chakraborty, S.; Nguyen, K.; Montefiori, D.C.; Korber, B.; Gnanakaran, S. The SARS-CoV-2 Spike variant D614G favors an open conformational state. Sci. Adv. 2021, 7, eabf3671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, C.; Wang, Y.; Liu, C.; Zhang, C.; Han, W.; Hong, X.; Wang, Y.; Hong, Q.; Wang, S.; Zhao, Q.; et al. Conformational dynamics of SARS-CoV-2 trimeric spike glycoprotein in complex with receptor ACE2 revealed by cryo-EM. Sci. Adv. 2021, 7, eabe5575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mori, T.; Jung, J.; Kobayashi, C.; Dokainish, H.M.; Re, S.; Sugita, Y. Elucidation of interactions regulating conformational stability and dynamics of SARS-CoV-2 S-protein. Biophys. J. 2021, 120, 1060–1071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barton, M.I.; MacGowan, S.A.; Kutuzov, M.A.; Dushek, O.; Barton, G.J.; van der Merwe, P.A. Effects of common mutations in the SARS-CoV-2 Spike RBD and its ligand, the human ACE2 receptor on binding affinity and kinetics. Elife 2021, 10, e70658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, S.; Alshahrani, M.; Gupta, G.; Tao, P.; Verkhivker, G. Markov State Models and Perturbation-Based Approaches Reveal Distinct Dynamic Signatures and Hidden Allosteric Pockets in the Emerging SARS-Cov-2 Spike Omicron Variant Complexes with the Host Receptor: The Interplay of Dynamics and Convergent Evolution Modulates Allostery and Functional Mechanisms. J. Chem. Inf. Model. 2023, 63, 5272–5296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Raisinghani, N.; Alshahrani, M.; Gupta, G.; Xiao, S.; Tao, P.; Verkhivker, G. AlphaFold2 Predictions of Conformational Ensembles and Atomistic Simulations of the SARS-CoV-2 Spike XBB Lineages Reveal Epistatic Couplings between Convergent Mutational Hotspots That Control ACE2 Affinity. J. Phys. Chem. B. 2024, 128, 4696–4715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Raisinghani, N.; Alshahrani, M.; Gupta, G.; Verkhivker, G. Ensemble-Based Mutational Profiling and Network Analysis of the SARS-CoV-2 Spike Omicron XBB Lineages for Interactions with the ACE2 Receptor and Antibodies: Cooperation of Binding Hotspots in Mediating Epistatic Couplings Underlies Binding Mechanism and Immune Escape. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 4281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Raisinghani, N.; Alshahrani, M.; Gupta, G.; Verkhivker, G. AlphaFold2 Modeling and Molecular Dynamics Simulations of the Conformational Ensembles for the SARS-CoV-2 Spike Omicron JN.1, KP.2 and KP.3 Variants: Mutational Profiling of Binding Energetics Reveals Epistatic Drivers of the ACE2 Affinity and Escape Hotspots of Antibody Resistance. Viruses 2024, 16, 1458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verkhivker, G.M.; Di Paola, L. Dynamic Network Modeling of Allosteric Interactions and Communication Pathways in the SARS-CoV-2 Spike Trimer Mutants: Differential Modulation of Conformational Landscapes and Signal Transmission via Cascades of Regulatory Switches. J. Phys. Chem. B 2021, 125, 850–873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verkhivker, G.M.; Agajanian, S.; Oztas, D.Y.; Gupta, G. Dynamic Profiling of Binding and Allosteric Propensities of the SARS-CoV-2 Spike Protein with Different Classes of Antibodies: Mutational and Perturbation-Based Scanning Reveals the Allosteric Duality of Functionally Adaptable Hotspots. J. Chem. Theory Comput. 2021, 17, 4578–4598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verkhivker, G.M.; Agajanian, S.; Oztas, D.Y.; Gupta, G. Allosteric Control of Structural Mimicry and Mutational Escape in the SARS-CoV-2 Spike Protein Complexes with the ACE2 Decoys and Miniprotein Inhibitors: A Network-Based Approach for Mutational Profiling of Binding and Signaling. J. Chem. Inf. Model. 2021, 61, 5172–5191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verkhivker, G.M.; Di Paola, L. Integrated Biophysical Modeling of the SARS-CoV-2 Spike Protein Binding and Allosteric Interactions with Antibodies. J. Phys. Chem. B 2021, 125, 4596–4619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verkhivker, G.M.; Agajanian, S.; Oztas, D.Y.; Gupta, G. Comparative Perturbation-Based Modeling of the SARS-CoV-2 Spike Protein Binding with Host Receptor and Neutralizing Antibodies: Structurally Adaptable Allosteric Communication Hotspots Define Spike Sites Targeted by Global Circulating Mutations. Biochemistry 2021, 60, 1459–1484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verkhivker, G.; Agajanian, S.; Kassab, R.; Krishnan, K. Integrating Conformational Dynamics and Perturbation-Based Network Modeling for Mutational Profiling of Binding and Allostery in the SARS-CoV-2 Spike Variant Complexes with Antibodies: Balancing Local and Global Determinants of Mutational Escape Mechanisms. Biomolecules 2022, 12, 964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yajima, H.; Nomai, T.; Okumura, K.; Maenaka, K.; Ito, J.; Hashiguchi, T.; Sato, K.; Matsuno, K.; Nao, N.; Sawa, H.; Mizuma, K.; Li, J.; Kida, I.; Mimura, Y.; Ohari, Y.; Tanaka, S.; Tsuda, M.; Wang, L.; Oda, Y.; Ferdous, Z.; Shishido, K.; Mohri, H.; Iida, M.; Fukuhara, T.; Tamura, T.; Suzuki, R.; Suzuki, S.; Tsujino, S.; Ito, H.; Kaku, Y.; Misawa, N.; Plianchaisuk, A.; Guo, Z.; Hinay, A. A., Jr.; Usui, K.; Saikruang, W.; Lytras, S.; Uriu, K.; Yoshimura, R.; Kawakubo, S.; Nishumura, L.; Kosugi, Y.; Fujita, S.; M.Tolentino, J. E.; Chen, L.; Pan, L.; Li, W.; Yo, M. S.; Horinaka, K.; Suganami, M.; Chiba, M.; Yasuda, K.; Iida, K.; Strange, A. P.; Ohsumi, N.; Tanaka, S.; Ogawa, E.; Fukuda, T.; Osujo, R.; Yoshimura, K.; Sadamas, K.; Nagashima, M.; Asakura, H.; Yoshida, I.; Nakagawa, S.; Takayama, K.; Hashimoto, R.; Deguchi, S.; Watanabe, Y.; Nakata, Y.; Futatsusako, H.; Sakamoto, A.; Yasuhara, N.; Suzuki, T.; Kimura, K.; Sasaki, J.; Nakajima, Y.; Irie, T.; Kawabata, R.; Sasaki-Tabata, K.; Ikeda, T.; Nasser, H.; Shimizu, R.; Begum, M. M.; Jonathan, M.; Mugita, Y.; Leong, S.; Takahashi, O.; Ueno, T.; Motozono, C.; Toyoda, M.; Saito, A.; Kosaka, A.; Kawano, M.; Matsubara, N.; Nishiuchi, T.; Zahradnik, J.; Andrikopoulos, P.; Padilla-Blanco, M.; Konar, A. Molecular and Structural Insights into SARS-CoV-2 Evolution: From BA.2 to XBB Subvariants. mBio 2024, 15, e0322023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xue, S.; Han, Y.; Wu, F.; Wang, Q. Mutations in the SARS-CoV-2 Spike Receptor Binding Domain and Their Delicate Balance between ACE2 Affinity and Antibody Evasion. Protein Cell. 2024, 15, 403–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Focosi, D.; Quiroga, R.; McConnell, S.; Johnson, M.C.; Casadevall, A. Convergent Evolution in SARS-CoV-2 Spike Creates a Variant Soup from Which New COVID-19 Waves Emerge. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 2264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gan, H.H. Twaddle, A.; Marchand, B.; Gunsalus, K.C. Structural Modeling of the SARS-CoV-2 Spike/Human ACE2 Complex Interface can Identify High-Affinity Variants Associated with Increased Transmissibility. J. Mol. Biol. 2021, 433, 167051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gan, H. H.; Zinno, J.; Piano, F.; Gunsalus, K. C. Omicron Spike Protein Has a Positive Electrostatic Surface That Promotes ACE2 Recognition and Antibody Escape. Front. Virol. 2022, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barroso da Silva, F. L.; Giron, C. C.; Laaksonen, A. Electrostatic Features for the Receptor Binding Domain of SARS-COV-2 Wildtype and Its Variants. Compass to the Severity of the Future Variants with the Charge-Rule. J. Phys. Chem. B. 2022, 126, 6835–6852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raisinghani, N.; Alshahrani, M.; Gupta, G.; Xiao, S.; Tao, P.; Verkhivker, G. AlphaFold2 Predictions of Conformational Ensembles and Atomistic Simulations of the SARS-CoV-2 Spike XBB Lineages Reveal Epistatic Couplings between Convergent Mutational Hotspots That Control ACE2 Affinity. J Phys Chem B. 2024, 128, 4696–4715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raisinghani, N.; Alshahrani, M.; Gupta, G.; Xiao, S.; Tao, P.; Verkhivker, G. Exploring Conformational Landscapes and Binding Mechanisms of Convergent Evolution for the SARS-CoV-2 Spike Omicron Variant Complexes with the ACE2 Receptor Using AlphaFold2-Based Structural Ensembles and Molecular Dynamics Simulations. Phys Chem Chem Phys. 2024, 26, 17720–17744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tortorici, M. A.; Czudnochowski, N.; Starr, T. N.; Marzi, R.; Walls, A. C.; Zatta, F.; Bowen, J. E.; Jaconi, S.; Di Iulio, J.; Wang, Z.; De Marco, A.; Zepeda, S. K.; Pinto, D.; Liu, Z.; Beltramello, M.; Bartha, I.; Housley, M. P.; Lempp, F. A.; Rosen, L. E.; Dellota, E., Jr; Kaiser, H.; Montiel-Ruiz, M.; Zhou, J.; Addetia, A.; Guarino, B.; Culap, K.; Sprugasci, N.; Saliba, C.; Vetti, E.; Giacchetto-Sasselli, I.; Fregni, C. S.; Abdelnabi, R.; Foo, S.-Y. C.; Havenar-Daughton, C.; Schmid, M. A.; Benigni, F.; Cameroni, E.; Neyts, J.; Telenti, A.; Virgin, H. W.; Whelan, S. P. J.; Snell, G.; Bloom, J. D.; Corti, D.; Veesler, D.; Pizzuto, M. S. Broad Sarbecovirus Neutralization by a Human Monoclonal Antibody. Nature 2021, 597, 103–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinto, D.; Sauer, M. M.; Czudnochowski, N.; Low, J. S.; Tortorici, M. A.; Housley, M. P.; Noack, J.; Walls, A. C.; Bowen, J. E.; Guarino, B.; Rosen, L. E.; di Iulio, J.; Jerak, J.; Kaiser, H.; Islam, S.; Jaconi, S.; Sprugasci, N.; Culap, K.; Abdelnabi, R.; Foo, C.; Coelmont, L.; Bartha, I.; Bianchi, S.; Silacci-Fregni, C.; Bassi, J.; Marzi, R.; Vetti, E.; Cassotta, A.; Ceschi, A.; Ferrari, P.; Cippà, P. E.; Giannini, O.; Ceruti, S.; Garzoni, C.; Riva, A.; Benigni, F.; Cameroni, E.; Piccoli, L.; Pizzuto, M. S.; Smithey, M.; Hong, D.; Telenti, A.; Lempp, F. A.; Neyts, J.; Havenar-Daughton, C.; Lanzavecchia, A.; Sallusto, F.; Snell, G.; Virgin, H. W.; Beltramello, M.; Corti, D.; Veesler, D. Broad Betacoronavirus Neutralization by a Stem Helix–Specific Human Antibody. Science 2021, 373, 1109–1116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, R.; Shan, C.; Duan, X.; Chen, Z.; Liu, P.; Song, J.; Song, T.; Bi, X.; Han, C.; Wu, L.; Gao, G.; Hu, X.; Zhang, Y.; Tong, Z.; Huang, W.; Liu, W. J.; Wu, G.; Zhang, B.; Wang, L.; Qi, J.; Feng, H.; Wang, F.-S.; Wang, Q.; Gao, G. F.; Yuan, Z.; Yan, J. A Human Neutralizing Antibody Targets the Receptor-Binding Site of SARS-CoV-2. Nature 2020, 584, 120–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dong, J.; Zost, S. J.; Greaney, A. J.; Starr, T. N.; Dingens, A. S.; Chen, E. C.; Chen, R. E.; Case, J. B.; Sutton, R. E.; Gilchuk, P.; Rodriguez, J.; Armstrong, E.; Gainza, C.; Nargi, R. S.; Binshtein, E.; Xie, X.; Zhang, X.; Shi, P.-Y.; Logue, J.; Weston, S.; McGrath, M. E.; Frieman, M. B.; Brady, T.; Tuffy, K. M.; Bright, H.; Loo, Y.-M.; McTamney, P. M.; Esser, M. T.; Carnahan, R. H.; Diamond, M. S.; Bloom, J. D.; Crowe, J. E., Jr. Genetic and Structural Basis for SARS-CoV-2 Variant Neutralization by a Two-Antibody Cocktail. Nat Microbiol. 2021, 6, 1233–1244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hansen, J.; Baum, A.; Pascal, K. E.; Russo, V.; Giordano, S.; Wloga, E.; Fulton, B. O.; Yan, Y.; Koon, K.; Patel, K.; Chung, K. M.; Hermann, A.; Ullman, E.; Cruz, J.; Rafique, A.; Huang, T.; Fairhurst, J.; Libertiny, C.; Malbec, M.; Lee, W. Y.; Welsh, R.; Farr, G.; Pennington, S.; Deshpande, D.; Cheng, J.; Watty, A.; Bouffard, P.; Babb, R.; Levenkova, N.; Chen, C.; Zhang, B.; Romero Hernandez, A.; Saotome, K.; Zhou, Y.; Franklin, M.; Sivapalasingam, S.; Lye, D. C.; Weston, S.; Logue, J.; Haupt, R.; Frieman, M.; Chen, G.; Olson, W.; Murphy, A. J.; Stahl, N.; Yancopoulos, G. D.; Kyratsous, C. A. Studies in humanized mice and convalescent humans yield a SARS-CoV-2 antibody cocktail. Science 2020, 369, 1010–1014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jones, B. E.; Brown-Augsburger, P. L.; Corbett, K. S.; Westendorf, K.; Davies, J.; Cujec, T. P.; Wiethoff, C. M.; Blackbourne, J. L.; Heinz, B. A.; Foster, D.; Higgs, R. E.; Balasubramaniam, D.; Wang, L.; Zhang, Y.; Yang, E. S.; Bidshahri, R.; Kraft, L.; Hwang, Y.; Žentelis, S.; Jepson, K. R.; Goya, R.; Smith, M. A.; Collins, D. W.; Hinshaw, S. J.; Tycho, S. A.; Pellacani, D.; Xiang, P.; Muthuraman, K.; Sobhanifar, S.; Piper, M. H.; Triana, F. J.; Hendle, J.; Pustilnik, A.; Adams, A. C.; Berens, S. J.; Baric, R. S.; Martinez, D. R.; Cross, R. W.; Geisbert, T. W.; Borisevich, V.; Abiona, O.; Belli, H. M.; de Vries, M.; Mohamed, A.; Dittmann, M.; Samanovic, M. I.; Mulligan, M. J.; Goldsmith, J. A.; Hsieh, C.-L.; Johnson, N. V.; Wrapp, D.; McLellan, J. S.; Barnhart, B. C.; Graham, B. S.; Mascola, J. R.; Hansen, C. L.; Falconer, E. The Neutralizing Antibody, LY-CoV555, Protects against SARS-CoV-2 Infection in Nonhuman Primates. Sci Transl Med. 2021, 13, eabf1906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Westendorf, K.; Žentelis, S.; Wang, L.; Foster, D.; Vaillancourt, P.; Wiggin, M.; Lovett, E.; van der Lee, R.; Hendle, J.; Pustilnik, A.; Sauder, J. M.; Kraft, L.; Hwang, Y.; Siegel, R. W.; Chen, J.; Heinz, B. A.; Higgs, R. E.; Kallewaard, N. L.; Jepson, K.; Goya, R.; Smith, M. A.; Collins, D. W.; Pellacani, D.; Xiang, P.; de Puyraimond, V.; Ricicova, M.; Devorkin, L.; Pritchard, C.; O’Neill, A.; Dalal, K.; Panwar, P.; Dhupar, H.; Garces, F. A.; Cohen, C. A.; Dye, J. M.; Huie, K. E.; Badger, C. V.; Kobasa, D.; Audet, J.; Freitas, J. J.; Hassanali, S.; Hughes, I.; Munoz, L.; Palma, H. C.; Ramamurthy, B.; Cross, R. W.; Geisbert, T. W.; Menachery, V.; Lokugamage, K.; Borisevich, V.; Lanz, I.; Anderson, L.; Sipahimalani, P.; Corbett, K. S.; Yang, E. S.; Zhang, Y.; Shi, W.; Zhou, T.; Choe, M.; Misasi, J.; Kwong, P. D.; Sullivan, N. J.; Graham, B. S.; Fernandez, T. L.; Hansen, C. L.; Falconer, E.; Mascola, J. R.; Jones, B. E.; Barnhart, B. C. LY-CoV1404 (Bebtelovimab) Potently Neutralizes SARS-CoV-2 Variants. Cell Rep. 2022, 39, 110812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kmiecik, S.; Gront, D.; Kolinski, M.; Wieteska, L.; Dawid, A.E.; Kolinski, A. Coarse-grained protein models and their applications. Chem. Rev. 2016, 116, 7898–7936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kmiecik, S.; Kouza, M.; Badaczewska-Dawid, A.E.; Kloczkowski, A.; Kolinski, A. Modeling of protein structural flexibility and large-scale dynamics: Coarse-grained simulations and elastic network models. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2018, 19, 3496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kurcinski, M.; Oleniecki, T.; Ciemny, M.P.; Kuriata, A.; Kolinski, A.; Kmiecik, S. CABS-flex standalone: A simulation environment for fast modeling of protein flexibility. Bioinformatics 2019, 35, 694–695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baum, A.; Fulton, B. O.; Wloga, E.; Copin, R.; Pascal, K. E.; Russo, V.; Giordano, S.; Lanza, K.; Negron, N.; Ni, M.; Wei, Y.; Atwal, G. S.; Murphy, A. J.; Stahl, N.; Yancopoulos, G. D.; Kyratsous, C. A. Antibody cocktail to SARS-CoV-2 spike protein prevents rapid mutational escape seen with individual antibodies. Science 2020, 369, 1014–1018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koukos, P.I.; Glykos, N.M. Grcarma: A fully automated task-oriented interface for the analysis of molecular dynamics trajectories. J. Comput. Chem. 2013, 34, 2310–2312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haliloglu, T.; Bahar, I. Adaptability of protein structures to enable functional interactions and evolutionary implications. Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol 2015, 35, 17–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Y.; Doruker, P.; Kaynak, B.; Zhang, S.; Krieger, J.; Li, H.; Bahar, I. Intrinsic dynamics is evolutionarily optimized to enable allosteric behavior. Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol. 2020, 62, 14–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rose, P. W.; Prlic, A.; Altunkaya, A.; Bi, C.; Bradley, A. R.; Christie, C. H.; Costanzo, L. D.; Duarte, J. M.; Dutta, S.; Feng, Z.; Green, R. K.; Goodsell, D. S.; Hudson, B.; Kalro, T.; Lowe, R.; Peisach, E.; Randle, C.; Rose, A. S.; Shao, C.; Tao, Y. P.; Valasatava, Y.; Voigt, M.; Westbrook, J. D.; Woo, J.; Yang, H.; Young, J. Y.; Zardecki, C.; Berman, H. M.; Burley, S. K. The RCSB protein data bank: integrative view of protein, gene and 3D structural information. Nucleic Acids Res. 2017, 45, D271–D281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hekkelman, M.L.; Te Beek, T.A.; Pettifer, S.R.; Thorne, D.; Attwood, T.K.; Vriend, G. WIWS: A protein structure bioinformatics web service collection. Nucleic Acids Res. 2010, 38, W719–W723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernandez-Fuentes, N.; Zhai, J.; Fiser, A. ArchPRED: A template based loop structure prediction server. Nucleic Acids Res. 2006, 34, W173–W176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Krivov, V.P. B.F.; Shapovalov, M.V.; Dunbrack, R.L., Jr. Improved prediction of protein side-chain conformations with SCWRL4. Proteins 2009, 77, 778–795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Søndergaard C., R.; Olsson M., H.; Rostkowski, M.; Jensen J., H. Improved treatment of ligands and coupling effects in empirical calculation and rationalization of pKa values. J. Chem. Theory Comput. 2011, 7, 2284–2295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olsson M., H.; Søndergaard C., R.; Rostkowski, M.; Jensen J., H. PROPKA3: consistent treatment of internal and surface residues in empirical pKa predictions. J. Chem. Theory Comput. 2011, 7, 525–537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhattacharya, D.; Cheng, J. 3Drefine: Consistent Protein Structure Refinement by Optimizing Hydrogen Bonding Network and Atomic-Level Energy Minimization. Proteins 2013, 81, 119–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhattacharya, D.; Nowotny, J.; Cao, R.; Cheng, J. 3Drefine: An Interactive Web Server for Efficient Protein Structure Refinement. Nucleic Acids Res. 2016, 44, W406–W409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marti-Renom, M. A.; Stuart, A. C.; Fiser, A.; Sanchez, R.; Melo, F.; Sali, A. Comparative protein structure modeling of genes and genomes. Annu Rev Biophys Biomol Struct 2000, 29, 291–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Webb, B.; Sali, A. Comparative Protein Structure Modeling Using MODELLER. Curr Protoc Bioinformatics 2016, 54, 5.6.1–5.6.37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Phillips, J.C.; Hardy, D.J.; Maia, J.D.C.; Stone, J.E.; Ribeiro, J.V.; Bernardi, R.C.; Buch, R.; Fiorin, G.; Hénin, J.; Jiang, W.; et al. Scalable Molecular Dynamics on CPU and GPU Architectures with NAMD. J. Chem. Phys. 2020, 153, 044130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, J.; Rauscher, S.; Nawrocki, G.; Ran, T.; Feig, M.; de Groot, B.L.; Grubmüller, H.; MacKerell, A.D., Jr. CHARMM36m: An improved force field for folded and intrinsically disordered proteins. Nat. Methods 2017, 14, 71–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernandes, H.S.; Sousa, S.F.; Cerqueira, N.M.F.S.A. VMD Store-A VMD Plugin to Browse, Discover, and Install VMD Extensions. J. Chem. Inf. Model. 2019, 59, 4519–4523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jo, S.; Kim, T.; Iyer, V. G.; Im, W. CHARMM-GUI: A Web-based Graphical User Interface for CHARMM. J Comput Chem. 2008, 29, 1859–1865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.; Cheng, X.; Swails, J. M.; Yeom, M. S.; Eastman, P. K.; Lemkul, J. A.; Wei, S.; Buckner, J.; Jeong, J. C.; Qi, Y.; Jo, S.; Pande, V. S.; Case, D. A.; Brooks, C. L., III; MacKerell, A. D., Jr.; Klauda, J. B.; Im, W. CHARMM-GUI Input Generator for NAMD, GROMACS, AMBER, OpenMM, and CHARMM/OpenMM Simulations Using the CHARMM36 Additive Force Field. J Chem Theory Comput. 2016, 12, 405–413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jorgensen, W.L.; Chandrasekhar, J.; Madura, J.D.; Impey, R.W.; Klein, M.L. Comparison of Simple Potential Functions for Simulating Liquid Water. J. Chem. Phys. 1983, 79, 926–935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ross, G.A.; Rustenburg, A.S.; Grinaway, P.B.; Fass, J.; Chodera, J.D. Biomolecular Simulations under Realistic Macroscopic Salt Conditions. J. Phys. Chem. B 2018, 122, 5466–5486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Pierro, M.; Elber, R.; Leimkuhler, B. A Stochastic Algorithm for the Isobaric-Isothermal Ensemble with Ewald Summations for All Long Range Forces. J. Chem. Theory Comput. 2015, 11, 5624–5637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martyna, G.J.; Tobias, D.J.; Klein, M.L. Constant pressure molecular dynamics algorithms. J. Chem. Phys. 1994, 101, 4177–4189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feller, S.E.; Zhang, Y.; Pastor, R.W.; Brooks, B.R. Constant pressure molecular dynamics simulation: The Langevin piston method. J. Chem. Phys. 1995, 103, 4613–4621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davidchack, R.L.; Handel, R.; Tretyakov, M.V. Langevin thermostat for rigid body dynamics. J. Chem. Phys. 2009, 130, 234101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dehouck, Y.; Kwasigroch, J. M.; Rooman, M.; Gilis, D. BeAtMuSiC: Prediction of changes in protein-protein binding affinity on mutations. Nucleic Acids Res. 2013, 41, W333–W339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dehouck, Y.; Grosfils, A.; Folch, B.; Gilis, D.; Bogaerts, P.; Rooman, M. Fast and accurate predictions of protein stability changes upon mutations using statistical potentials and neural networks:PoPMuSiC-2.0. Bioinformatics 2009, 25, 2537–2543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Srinivasan, J.; Cheatham, T. E.; Cieplak, P.; Kollman, P. A.; Case, D. A. Continuum Solvent Studies of the Stability of DNA, RNA, and Phosphoramidate−DNA Helices. J. Amer. Chem. Soc. 1998, 120, 9401–9409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kollman, P. A.; Massova, I.; Reyes, C.; Kuhn, B.; Huo, S.; Chong, L.; Lee, M.; Lee, T.; Duan, Y.; Wang, W.; Donini, O.; Cieplak, P.; Srinivasan, J.; Case, D. A.; Cheatham, T. E. Calculating Structures and Free Energies of Complex Molecules: Combining Molecular Mechanics and Continuum Models. Acc. Chem. Res. 2000, 33, 889–897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, T.; Wang, J.; Li, Y.; Wang, W. Assessing the Performance of the MM/PBSA and MM/GBSA Methods. 1. The Accuracy of Binding Free Energy Calculations Based on Molecular Dynamics Simulations. J. Chem. Inf. Model. 2011, 51, 69–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weng, G.; Wang, E.; Wang, Z.; Liu, H.; Zhu, F.; Li, D.; Hou, T. HawkDock: A Web Server to Predict and Analyze the Protein–Protein Complex Based on Computational Docking and MM/GBSA. Nucleic Acids Res. 2019, 47, W322–W330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mongan, J.; Simmerling, C.; McCammon, J. A.; Case, D. A.; Onufriev, A. Generalized Born Model with a Simple, Robust Molecular Volume Correction. J Chem Theory Comput. 2007, 3, 156–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, A. H.; Zhan, C.-G. Generalized Methodology for the Quick Prediction of Variant SARS-CoV-2 Spike Protein Binding Affinities with Human Angiotensin-Converting Enzyme II. J. Phys. Chem. B. 2022, 126, 2353–2360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, H.; Duan, L.; Chen, F.; Liu, H.; Wang, Z.; Pan, P.; Zhu, F.; Zhang, J. Z. H.; Hou, T. Assessing the Performance of MM/PBSA and MM/GBSA Methods. 7. Entropy Effects on the Performance of End-Point Binding Free Energy Calculation Approaches. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2018, 20, 14450–14460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miller, B. R., III; McGee, T. D., Jr.; Swails, J. M.; Homeyer, N.; Gohlke, H.; Roitberg, A. E. MMPBSA.Py: An Efficient Program for End-State Free Energy Calculations. J Chem Theory Comput. 2012, 8, 3314–3321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Valdés-Tresanco, M. S.; Valdés-Tresanco, M. E.; Valiente, P. A.; Moreno, E. gmx_MMPBSA: A New Tool to Perform End-State Free Energy Calculations with GROMACS. J Chem Theory Comput. 2021, 17, 6281–6291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).