Submitted:

10 July 2025

Posted:

14 July 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

1.1. Faculty Support and Belonging to University

1.2. The Mediating Role of Perceived Campus Climate

1.3. The Mediating Role of Self-Efficacy

1.4. The Serial Mediating Role of Perceived Campus Climate and Self-Efficacy

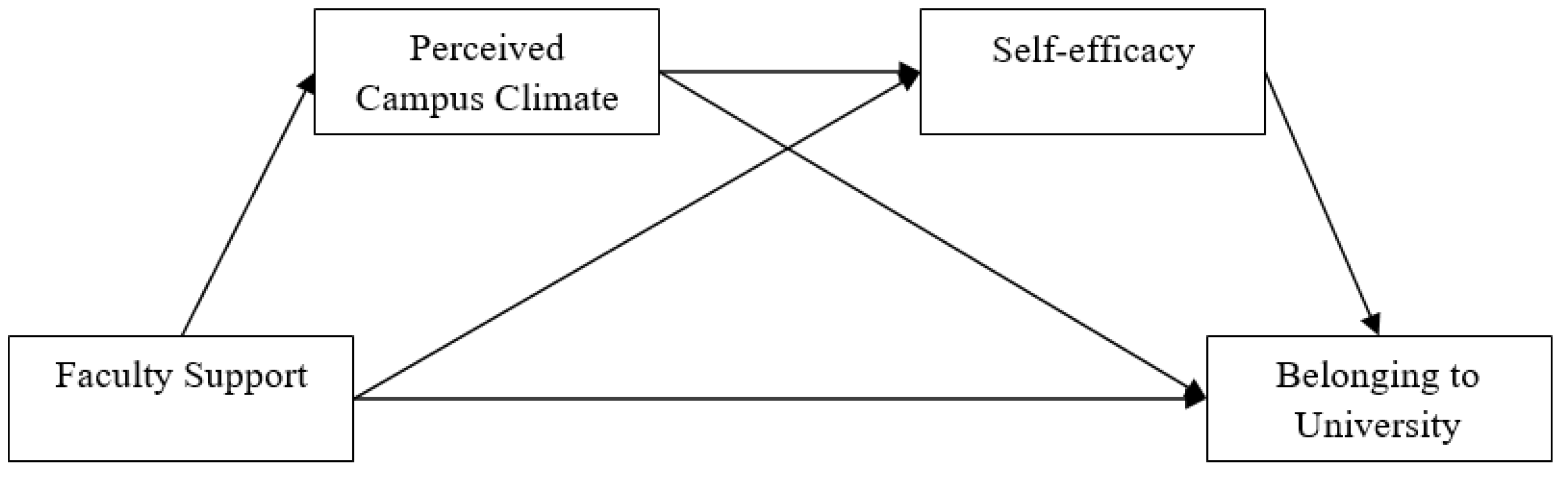

1.5. The Current Study

2. Method

2.1. Participants and Procedure

2.2. Measures

2.2.1. Perceived Faculty Support

2.2.2. Students' Perceptions of Atmosphere

2.2.3. The General Self-Efficacy Scale

2.2.4. The Belonging to University Scale

3. Results

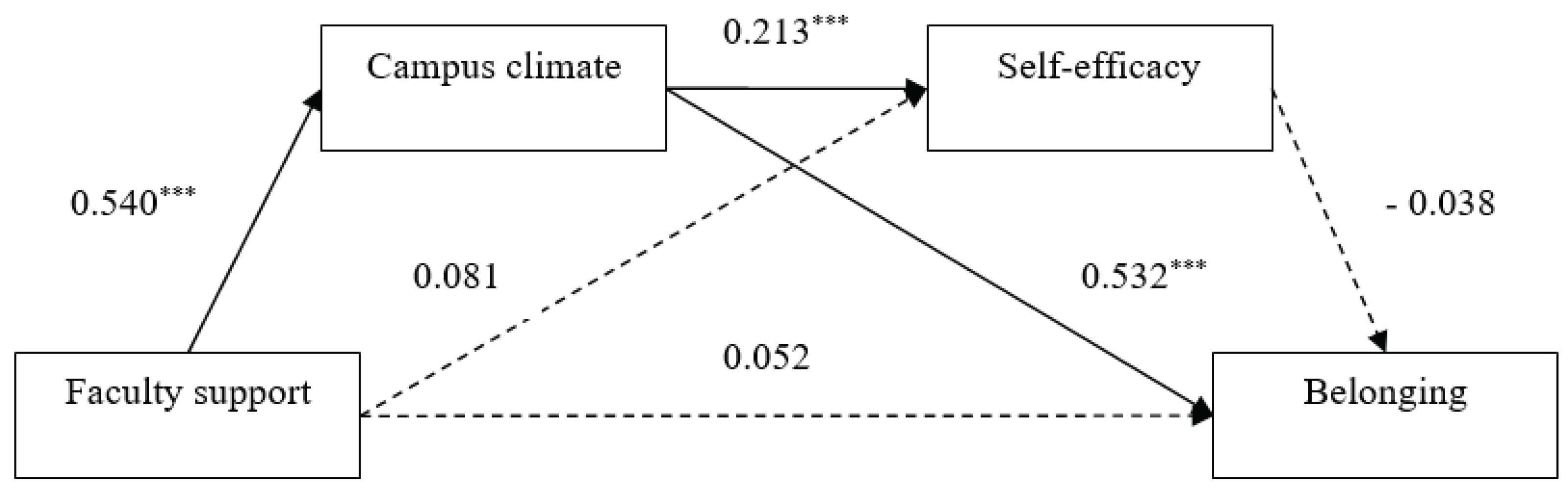

Testing the Serial Mediation Effect

4. Discussion

4.1. Faculty Support and Belonging to University

4.2. The Mediating Role of Perceived Campus Climate

4.3. The Mediating Role of Self-Efficacy

4.4. The Serial Mediating Role of Perceived Campus Climate and Self-Efficacy

4.5. Limitation

4.6. Implications

4.6.1. Theoretical Implications

4.6.2. Practical Implications

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Abd-Elmotaleb, M., & Saha, S. K. (2013). The Role of Academic Self-Efficacy as a Mediator Variable between Perceived Academic Climate and Academic Performance. Journal of Education and Learning, 2(3), 117-129. [CrossRef]

- Ahn, M. Y., & Davis, H. H. (2020). Four domains of students’ sense of belonging to university. Studies in Higher Education, 45(3), 622-634. [CrossRef]

- Astin, A. W. (1993). Diversity and multiculturalism on the campus: How are students affected? Change: The Magazine of Higher Learning, 25(2), 44-49. [CrossRef]

- Baumeister, R. F., & Leary, M. R. (2017). The need to belong: Desire for interpersonal attachments as a fundamental human motivation. Interpersonal development, 57-89.

- Bandura, A. (1986). The explanatory and predictive scope of self-efficacy theory. Journal of social and clinical psychology, 4(3), 359-373. [CrossRef]

- Bandura, A. (1997). Self-efficacy: The exercise of control (Vol. 11). Freeman.

- Berhanu, K. Z., & Sewagegn, A. A. (2024). The role of perceived campus climate in students’ academic achievements as mediated by students’ engagement in higher education institutions. Cogent Education, 11(1), 2377839. [CrossRef]

- Bordbar, M. (2021). Autonomy-supportive faculty, students' self-system processes, positive academic emotions, and agentic engagement: Adding emotions to self-system model of motivational development. Frontiers in Psychology, 12, 727794. [CrossRef]

- Karaman, O., & Cirak, Y. (2017). The Belonging to the University Scale. Acta Didactica Napocensia, 10(2), 1-20.

- Chemers, M. M., Hu, L. T., & Garcia, B. F. (2001). Academic self-efficacy and first year college student performance and adjustment. Journal of Educational psychology, 93(1), 55. [CrossRef]

- Çikrıkci, Ö. (2017). The Effect of Self-efficacy on Student Achievement. In: Karadag, E. (eds) The Factors Effecting Student Achievement. Springer, Cham. [CrossRef]

- Daliri, E., Zeinaddiny Meymand, Z., Soltani, A., & Hajipour Abaei, N. (2021). Examining the model of academic self-efficacy based on the teacher-student relationship in high school students. Iranian Evolutionary Educational Psychology Journal, 3(3), 247-255. [CrossRef]

- Girmay, M., & Singh, G. K. (2019). Social isolation, loneliness, and mental and emotional well-being among international students in the United States. International Journal of Translational Medical Research and Public Health, 3(2), 1-8. [CrossRef]

- Glass, C. R., Kociolek, E., Wongtrirat, R., Lynch, R. J., & Cong, S. (2015). Uneven Experiences: The Impact of Student-Faculty Interactions on International Students' Sense of Belonging. Journal of International Students, 5(4), 353-367. [CrossRef]

- Hajar, A., Mhamed, A. A. S., & Owusu, E. Y. (2025). African international students’ challenges, investment and identity development at a highly selective EMI university in Kazakhstan. Language and Education, 39(1), 54-71. [CrossRef]

- Handagoon, S. (2017). The influence of social support and student's self-efficacy on academic engagement of undergraduate students mediated by sense of belonging and psychological distress.

- Hoffman, M., Richmond, J., Morrow, J., & Salomone, K. (2002). Investigating “sense of belonging” in first-year college students. Journal of College Student Retention: Research, Theory & Practice, 4(3), 227-256. [CrossRef]

- Huang, X., & Fan, B. (2024). The association between campus climate and the mental health of LGBTQ+ college students: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Sexuality & Culture, 28(4), 1904-1959. [CrossRef]

- Hausmann, L. R., Schofield, J. W., & Woods, R. L. (2007). Sense of belonging as a predictor of intentions to persist among African American and White first-year college students. Research in higher education, 48, 803-839. [CrossRef]

- Jean-Francois, E. (2019). Exploring the perceptions of campus climate and integration strategies used by international students in a US university campus. Studies in Higher Education, 44(6), 1069-1085. [CrossRef]

- Jerusalem, M., & Schwarzer, R. (1992). Self-efficacy as a resource factor in stress appraisal processes. In R. Schwarzer (Ed.), Self-efficacy: Thought control of action (pp. 195-213). Washington, DC: Hemisphere.

- Juarez, D. R. (2017). Creating an environment of success: community college faculty efforts to engage in quality faculty-student interactions to contribute to a first-generation student's perception of belonging. Pepperdine University.

- Kim, Y. K., & Lundberg, C. A. (2016). A structural model of the relationship between student–faculty interaction and cognitive skills development among college students. Research in Higher Education, 57, 288-309. [CrossRef]

- Kim, D., Woo, Y., Song, J., & Son, S. (2023). The relationship between faculty interactions, sense of belonging, and academic stress: a comparative study of the post-COVID-19 college life of Korean and international graduate students in South Korea. Frontiers in Psychiatry, 14, 1169826. [CrossRef]

- Lin, C., Tong, Y., Bai, Y., Zhao, Z., Quan, W., Liu, Z., ... & Dong, W. (2022). Prevalence and correlates of depression and anxiety among Chinese international students in US colleges during the COVID-19 pandemic: A cross-sectional study. Plos one, 17(4), e0267081. [CrossRef]

- Meyers, L. S., Gamst, G., & Guarino, A. J. (2016). Applied multivariate research: Design and interpretation. Sage publications.

- McQueen, C., Thelamour, B., & Daniel, D. K. (2023). The Relationship Between Campus Climate Perceptions, Anxiety, and Academic Competence for College Women. College Student Affairs Journal, 41(1), 138-152. [CrossRef]

- Museus, S. D., Williams, M. S., & Lourdes, A. (2022). Analyzing the relationship between campus environments and academic self-efficacy in college. Journal of Student Affairs Research and Practice, 59(5), 487-501. [CrossRef]

- Neter, J., Kutner, M. H., Nachtsheim, C. J., & Wasserman, W. (1996). Applied linear statistical models (Vol. 4, p. 318). Chicago: Irwin.

- Nhien, C. (2025). How southeast Asian students develop their science self-efficacy during the first year of college. The Journal of Higher Education, 96(2), 251-278. [CrossRef]

- Organization of Student Affairs. (2024, August 4). Measures of the Student Affairs Organization in the field of international students during the 13th Iranian government. Organization of Student Affairs. https://www.saorg.ir/portal/home/?news/235224/235398/354655/.

- Pascarella, E. T. (1985). College environmental influences on learning and cognitive development: A critical review and synthesis. Higher education: Handbook of theory and research, 1(1), 1-61.

- Pedler, M. L., Willis, R., & Nieuwoudt, J. E. (2022). A sense of belonging at university: Student retention, motivation and enjoyment. Journal of Further and Higher Education, 46(3), 397-408. [CrossRef]

- Raboca, H. M., & Carbunarean, F. (2024, July). Faculty support and students’ academic motivation. In Frontiers in Education (Vol. 9, p. 1406611). Frontiers Media SA. [CrossRef]

- Reeve, J., & Cheon, S. H. (2021). Autonomy-supportive teaching: Its malleability, benefits, and potential to improve educational practice. Educational psychologist, 56(1), 54-77. [CrossRef]

- Roff, S. U. E., McAleer, S., Harden, R. M., Al-Qahtani, M., Ahmed, A. U., Deza, H., ... & Primparyon, P. (1997). Development and validation of the Dundee ready education environment measure (DREEM). Medical teacher, 19(4), 295-299. [CrossRef]

- Samadieh, H., Kareshki, H., Aminyazdi, S. A., & Hejazi, E. 92021). The Belonging to the University Scale: Psychometric Properties and Analysis of Current Status in the Context of Higher Education. Learning and Instruction, (12), 2, 1-22.

- Samadieh, H., Kareshki, H., Amin Yazdi, S. A., & Hejazi, E. (2023a). The Dynamics of Students' Sense of Belonging to University: A Phenomenological Study. Rooyesh-e-Ravanshenasi Journal (RRJ), 12(7), 41-52. http://frooyesh.ir/article-1-4706-en.html.

- Samadieh, H., Kareshki, H., Aminyazdi, S. A., & Hejazi, E. (2024a). Development and Validation of the Students' Sense of Belonging to University Scale. Quarterly of Educational Measurement, 14(55), 38-71.

- Samadieh, H., Kareshki, H., Amin Yazdi, S. A., & Hejazi, E. (2024b). Motivational Antecedents of Students' Sense of Belonging to University: The Role of Autonomy, Competence, Relatedness and Individual Interest. Education Strategies in Medical Sciences, 17(1), 33-44. http://edcbmj.ir/article-1-2667-en.html.

- Samadieh, H., & Rezaei, M. (2024). A serial mediation model of sense of belonging to university and life satisfaction: The role of social loneliness and depression. Acta Psychologica, 250, 104562. [CrossRef]

- Samadieh, H., Sadri, M., Heidari Jaghargh, K., Sabeti Baygi, A., & Esfalani, Y. (2023b). The Relationship of Basic Needs Satisfaction in Friendship Relationships to Students' Academic Engagement during COVID-19: The Mediating Role of Sense of Belonging to University. Journal of Research in Behavioural Sciences, 21(2), 410-422. http://rbs.mui.ac.ir/article-1-1593-en.html.

- Samadieh, H., & Tanhaye Reshvanloo, F. (2023). The relationship between sense of belonging and life satisfaction among university students: The mediating role of social isolation and psychological distress. Iranian journal of educational sociology, 6(3), 11-24. [CrossRef]

- Schumacker, R. E., & Lomax, R. G. (2012). A beginner's guide to structural equation modeling. Routledge.

- Severiens, S. E., & Schmidt, H. G. (2009). Academic and social integration and study progress in problem-based learning. Higher education, 58(1), 59-69. [CrossRef]

- Shalka, T. R., & Leal, C. C. (2022). Sense of belonging for college students with PTSD: The role of safety, stigma, and campus climate. Journal of American college health, 70(3), 698-705. [CrossRef]

- Sischka, P. E., Décieux, J. P., Mergener, A., Neufang, K. M., & Schmidt, A. F. (2022). The impact of forced answering and reactance on answering behavior in online surveys. Social Science Computer Review, 40(2), 405-425. [CrossRef]

- Smith, C. (2020). International students and their academic experiences: Student satisfaction, student success challenges, and promising teaching practices. Rethinking education across borders: Emerging issues and critical insights on globally mobile students, 271-287. [CrossRef]

- Souza, S. B. D., Veiga Simão, A. M., & Ferreira, P. D. C. (2019). Campus climate: The role of teacher support and cultural issues. Journal of Further and Higher Education, 43(9), 1196-1211. [CrossRef]

- Stevens, J. (2002). Applied multivariate statistics for the social sciences (Vol. 4). Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence erlbaum associates.

- Strayhorn, T. L. (2018). College students' sense of belonging: A key to educational success for all students. Routledge. [CrossRef]

- Tajvar, M., Ahmadizadeh, E., Sajadi, H. S., & Shaqura, I. I. (2024). Challenges facing international students at Iranian universities: a cross-sectional survey. BMC Medical Education, 24(1), 210. [CrossRef]

- Tinto, V. (1993). Building community. Liberal education, 79(4), 16-21.

- Tinto, V. (1997). Classrooms as communities: Exploring the educational character of student persistence. The Journal of higher education, 68(6), 599-623. [CrossRef]

- Tinto, V. (2012). Leaving college: Rethinking the causes and cures of student attrition. University of Chicago press.

- Turk, T., Elhady, M. T., Rashed, S., Abdelkhalek, M., Nasef, S. A., Khallaf, A. M., ... & Huy, N. T. (2018). Quality of reporting web-based and non-web-based survey studies: What authors, reviewers and consumers should consider. PloS one, 13(6), e0194239. [CrossRef]

- Yong, M. H., Chikwa, G., & Rehman, J. (2025). Factors affecting new students’ sense of belonging and wellbeing at university. Innovations in Education and Teaching International, 1-14. [CrossRef]

- van Kessel, G., Ryan, C., Paras, L., Johnson, N., Zariff, R. Z., & Stallman, H. M. (2025). Relationship between university belonging and student outcomes: A systematic review and meta-analysis. The Australian Educational Researcher, 1-24. [CrossRef]

- Xue, W., & Singh, M. K. M. (2025). Unveiling the academic, sociocultural, and psychological adaptation challenges of Chinese international students in Malaysia: A systematic review. Journal of International Students, 15(2), 69-86. [CrossRef]

- Zysberg, L., & Schwabsky, N. (2021). School climate, academic self-efficacy and student achievement. Educational Psychology, 41(4), 467-482. [CrossRef]

| Variable | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Faculty Support | 1 | |||

| 2. Campus Climate | 0.540** | 1 | ||

| 3. Self-efficacy | 0.197** | 0.257** | 1 | |

| 4. Belonging to University | 0.333** | 0.551** | 0.109* | 1 |

| M | 19.30 | 25.63 | 27.80 | 36.18 |

| SD | 4.631 | 6.461 | 5.709 | 5.004 |

| Regression equation (N=512) | Fit indicator | Coefficient and significance | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Outcome variable | Predictor variable | R | R2 | F | β | t |

| Campus climate | Faculty support | 0.540 | 0.292 | 210.477 | 0.540*** | 14.507 |

| Self-efficacy | Faculty support | 0.266 | 0.071 | 19.447 | 0.081 | 1.611 |

| Campus climate | 0.213*** | 4.197 | ||||

| Belonging | Faculty support | 0.332 | 0.110 | 63.559 | 0.332*** | 7.972 |

| Belonging | Faculty support | 0.554 | 0.307 | 74.997 | 0.052 | 1.194 |

| Campus climate | 0.532*** | 11.930 | ||||

| Self-efficacy | - 0.038 | -1.011 | ||||

| Effects | Boot SE | Boot LLCI | Boot ULCI | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total effect | 0.359 | 0.045 | 0.271 | 0.448 |

| Direct effect | 0.056 | 0.047 | - 0.036 | 0.150 |

| Total indirect effect | 0.280 | 0.030 | 0.221 | 0.342 |

| Indirect effect 1 | 0.288 | 0.031 | 0.228 | 0.353 |

| Indirect effect 2 | - 0.003 | 0.004 | - 0.014 | 0.003 |

| Indirect effect 3 | - 0.004 | 0.004 | - 0.014 | 0.005 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).