Submitted:

10 July 2025

Posted:

11 July 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Energy Conservation

2.1. Kinetic Energy

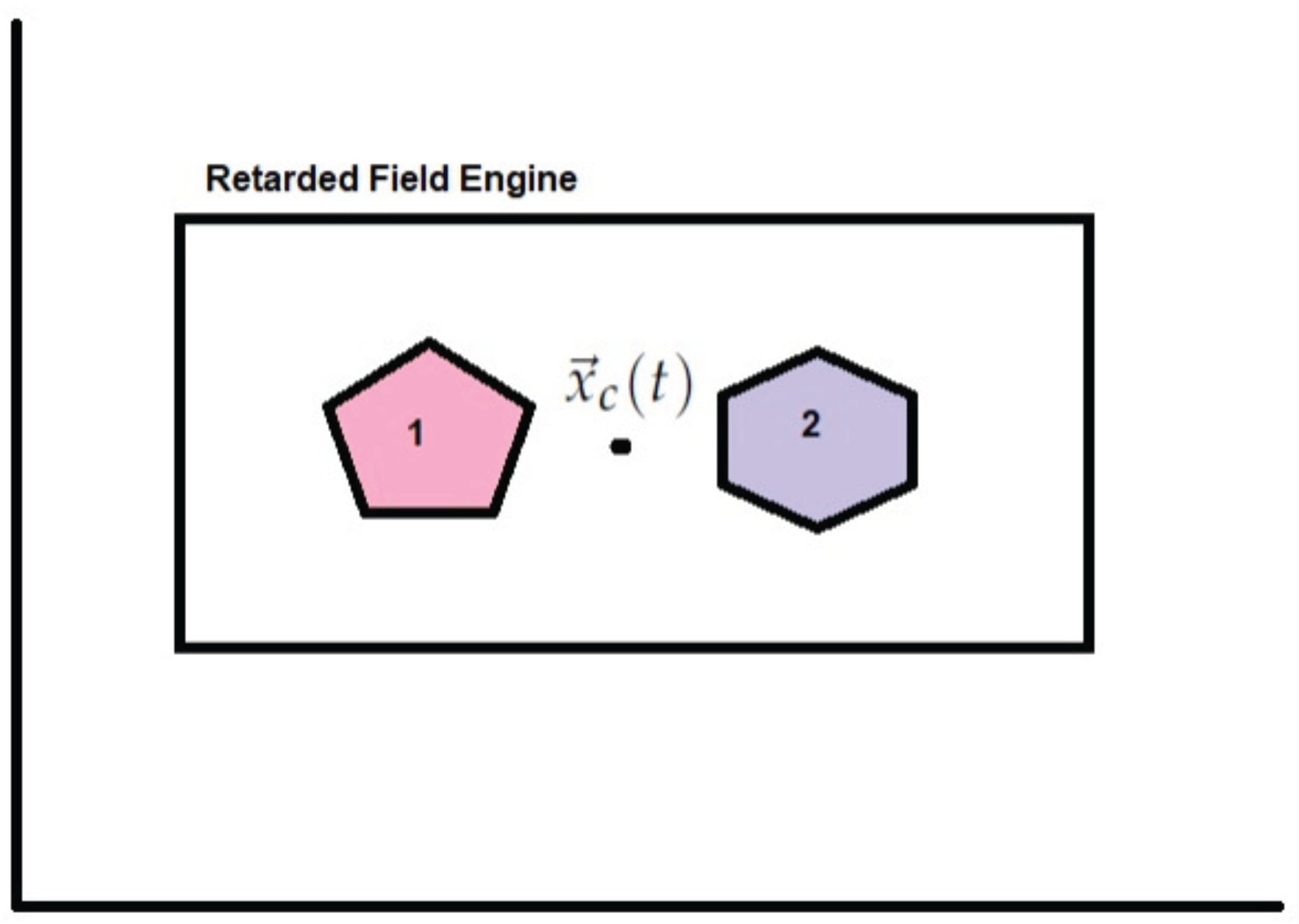

3. Field Energy for Two Charged Sub-Systems

4. Power Expansion in

4.1. n=0

4.1.1. Power

4.1.2. Field Energy

4.1.3. Poynting Vector

4.2. n=1

4.2.1. Power

4.2.2. Field Energy

4.2.3. Poynting Vector

4.3. n=2

4.3.1. Power

4.3.2. Field Energy

4.3.3. Poynting Vector

4.4. n=3

4.4.1. Power

4.4.2. Field Energy

4.4.3. Poynting Vector

4.5. n=4

4.5.1. Power

4.5.2. Poynting Vector

4.5.3. Field Energy

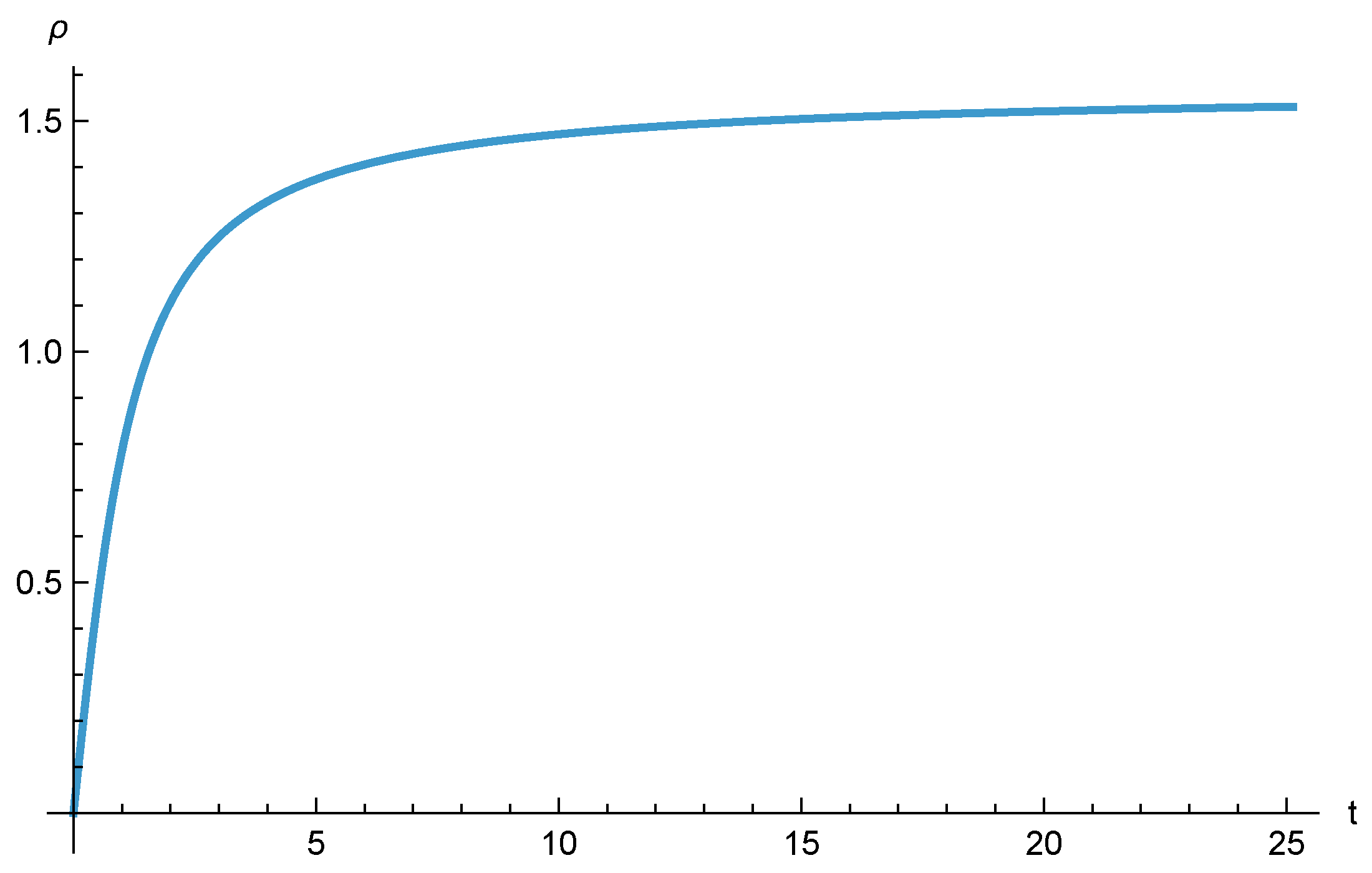

5. Discussion

6. The source of the Charged Retarded Field Engine Energy

7. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A. Simplification of Certain Integrals

Appendix B.

Appendix C.

Appendix D.

References

- Robertson, G.A.; Murad, P.; Davis, E. New frontiers in space propulsion sciences. Energy Conversion and Management 2008, 49, 436–452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Einstein, A. On the electrodynamics of moving bodies 1905.

- Jackson, J.D. Classical electrodynamics, 3rd ed. ed.; Wiley: New York, NY, 1999.

- Feynman, R.P.; Leighton, R.B.; Sands, M. The Feynman lectures on physics, Vol. I: The new millennium edition: mainly mechanics, radiation, and heat; Vol. 1, Basic books: New York,New York,USA, 2011.

- Griffiths, D.J.; Heald, M.A. Time-dependent generalizations of the Biot–Savart and Coulomb laws. American Journal of Physics 1991, 59, 111–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jefimenko, O. Electricity and Magnetism 2nd edn; Electret Scientific: Star City, WV:, 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Breitenberger, E. Magnetic interaction between charged particles. American Journal of Physics 1968, 36, 505–515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scanio, J. Conservation of momentum in electrodynamics - an example. American Journal of Physics 1975, 43, 258–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Portis, A. Electromagnetic Fields, Source and Media; John Wiley & Sons Inc: New-York, NY, USA, 1978. [Google Scholar]

- Jefimenko, O. A Relativistic Paradox Seemingly Violating Conservation of Momentum in Electromagnetic Systems. Eur. J. Phys. 1999, 20, 39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jefimenko, O. Cuasality, Electromagnetic Induction and Gravitation 2nd edn; Electret Scientific: Star City, WV:, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Rajput, S.; Yahalom, A. Newton’s Third Law in the Framework of Special Relativity for Charged Bodies. Symmetry 2021, 13, 1250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, P.; Yahalom, A. A Charged Relativistic Engine Based on a Permanent Magnet. Applied Sciences 2024, 14, 11764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajput, S.; Yahalom, A.; Qin, H. Lorentz symmetry group, retardation and energy transformations in a relativistic engine. Symmetry 2021, 13, 420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tuval, M.; Yahalom, A. Momentum conservation in a relativistic engine. The European Physical Journal Plus 2016, 131, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajput, S.; Yahalom, A. Material Engineering and Design of a Relativistic Engine: How to Avoid Radiation Losses. In Proceedings of the Advanced Engineering Forum. Trans Tech Publ, 2020, Vol. 36, pp. 126–131.

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).