Submitted:

09 July 2025

Posted:

11 July 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Soil Sampling

2.2. Soil Characterization

2.3. Preparation of Soil Samples

2.4. Biological Analysis

2.4.1. Microbial Activity, Biomass, and Metabolic Quotient

2.4.2. Total Bacteria Count in Petri Dishes

2.4.3. Phytotoxicity Test

2.4. Statistical Analysis

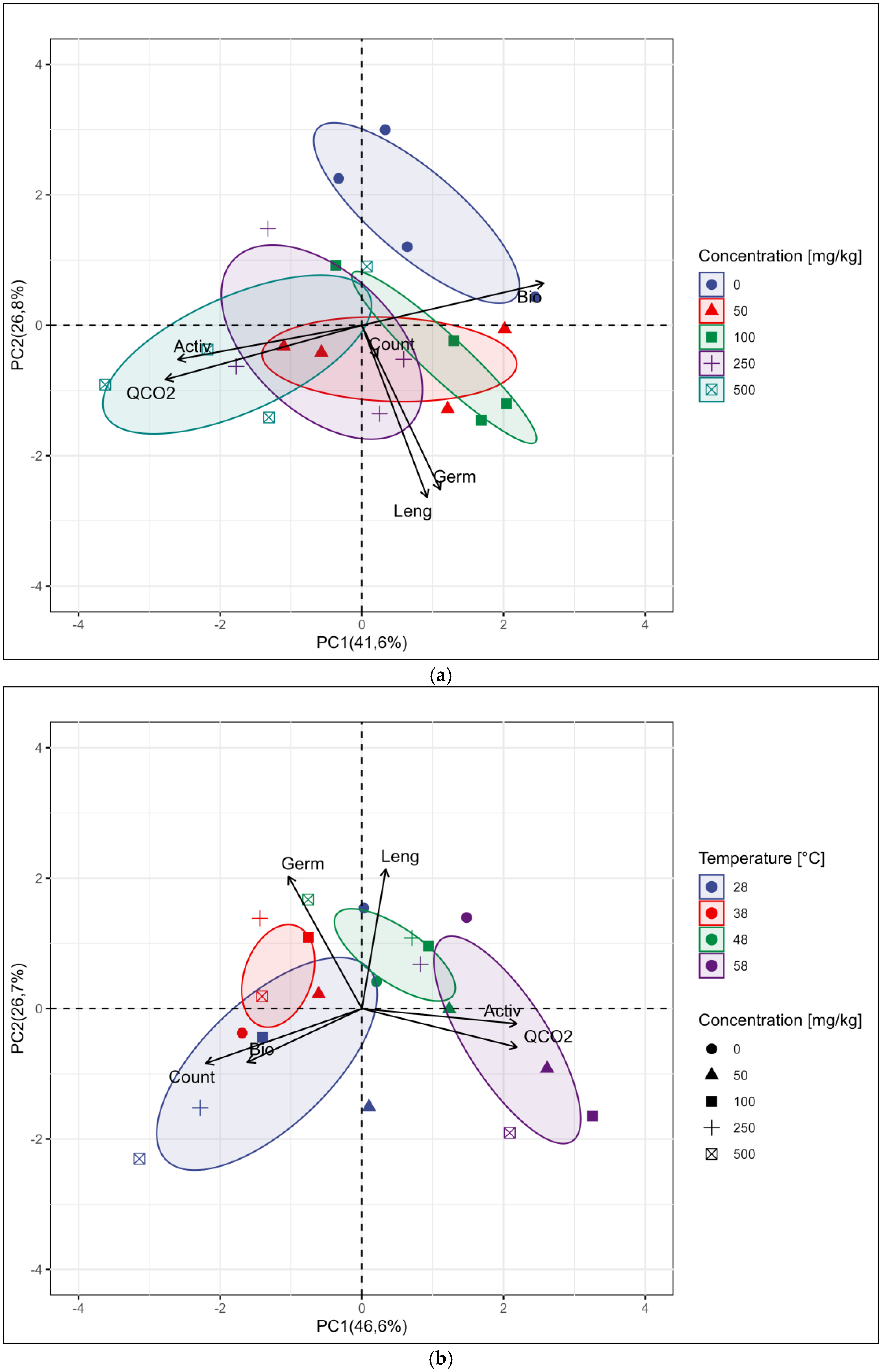

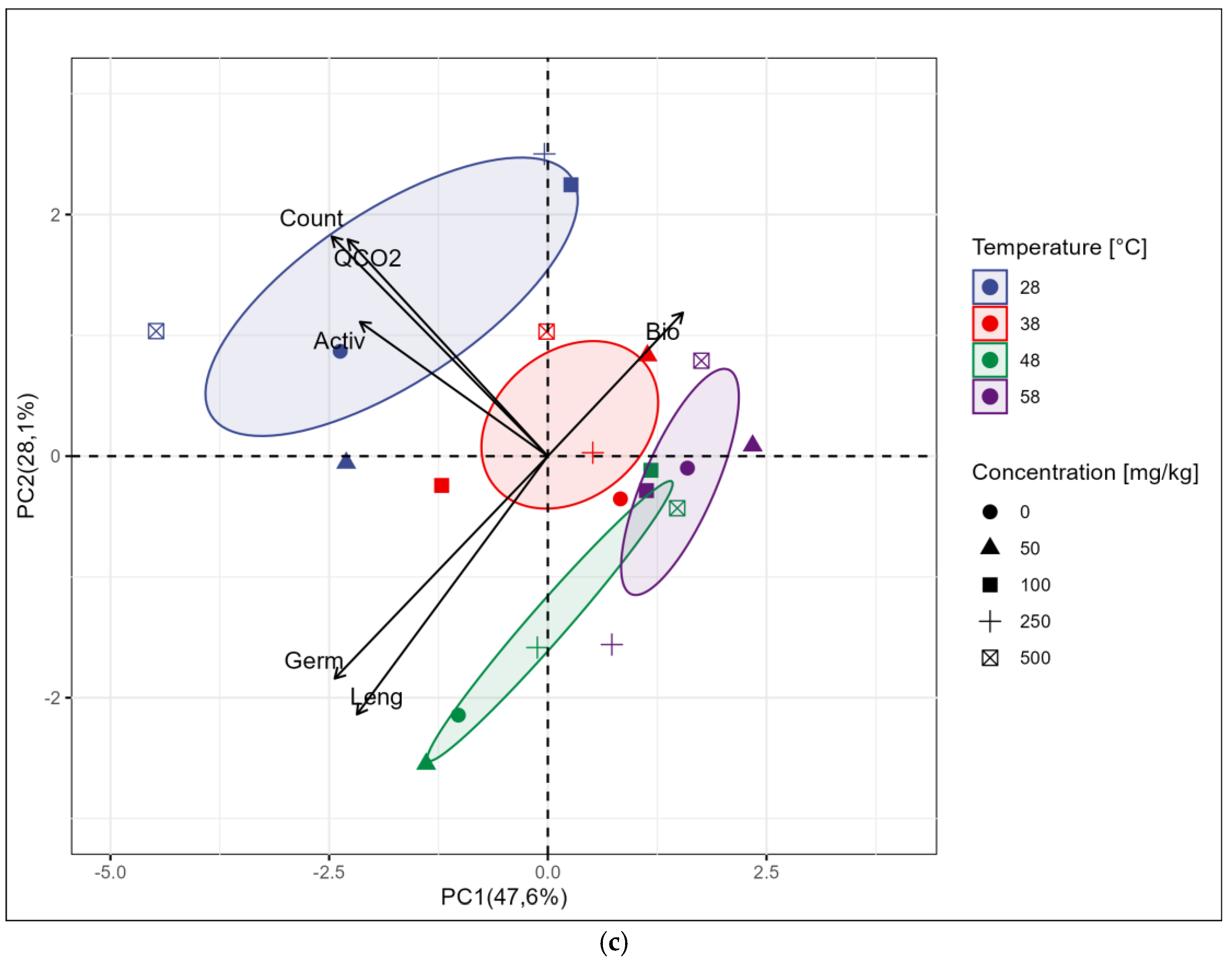

3. Results

3.1. Physicochemical Characterization of the Soil

3.2. Results of Biological Analysis

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| Activ | Microbial activity |

| Bio | Microbial biomass |

| QCO2 | Metabolic quotient |

| Count | Bacterial count on plate |

| Germ | Germination of lettuce seeds (L. sativa) |

| Leng | Lettuce root length (L. sativa) |

References

- Martins, E. da S.; Gianfredo, G. de M.; Martins, H.L.; Alves, P.L. da C.A. Contagem Microbiana, Atividade de β-Glicosidase e Isolamento de Fungos Termofílicos/Termotolerantes Em Solos Com Cultivo Convencional e Agroecológico. Rev. Geogr. - PPGEO - UFJF 2024, 14, 188–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pankhurst, C.E.; Hawke, B.G.; McDonald, H.J.; Kirkby, C.A.; Buckerfield, J.C.; Michelsen, P.; O’Brien, K.A.; Gupta, V.V.S.R.; Doube, B.M. Evaluation of Soil Biological Properties as Potential Bioindicators of Soil Health. Aust. J. Exp. Agric. 1995, 35, 1015–1028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Carmona, M.; Romero-Freire, A.; Sierra Aragón, M.; Martínez Garzón, F.J.; Martín Peinado, F.J. Evaluation of Remediation Techniques in Soils Affected by Residual Contamination with Heavy Metals and Arsenic. J. Environ. Manage. 2017, 191, 228–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gupta, A.; Gupta, R.; Singh, R.L. Microbes and Environment. In Principles and Applications of Environmental Biotechnology for a Sustainable Future; Singh, R.L., Ed.; Springer Singapore: Singapore, 2017; pp. 43–84. ISBN 978-981-10-1865-7. [Google Scholar]

- Cardoso, E.J.B.N.; Vasconcellos, R.L.F.; Bini, D.; Miyauchi, M.Y.H.; dos Santos, C.A.; Alves, P.R.L.; de Paula, A.M.; Nakatani, A.S.; Pereira, J. de M.; Nogueira, M.A. Soil Health: Looking for Suitable Indicators. What Should Be Considered to Assess the Effects of Use and Management on Soil Health? Sci. Agric. 2013, 70, 274–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernández, M.D.; Cagigal, E.; Vega, M.M.; Urzelai, A.; Babín, M.; Pro, J.; Tarazona, J.V. Ecological Risk Assessment of Contaminated Soils through Direct Toxicity Assessment. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2005, 62, 174–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lentendu, G.; Wubet, T.; Chatzinotas, A.; Wilhelm, C.; Buscot, F.; Schlegel, M. Effects of Long-Term Differential Fertilization on Eukaryotic Microbial Communities in an Arable Soil: A Multiple Barcoding Approach. Mol. Ecol. 2014, 23, 3341–3355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stroud, J.L.; Low, A.; Collins, R.N.; Manefield, M. Metal(Loid) Bioaccessibility Dictates Microbial Community Composition in Acid Sulfate Soil Horizons and Sulfidic Drain Sediments. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2014, 48, 8514–8521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zamulina, I. V.; Gorovtsov, A. V.; Minkina, T.M.; Mandzhieva, S.S.; Burachevskaya, M. V.; Bauer, T. V. Soil Organic Matter and Biological Activity under Long-Term Contamination with Copper. Environ. Geochem. Health 2022, 44, 387–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Izmalkova, T.Y.; Sazonova, O.I.; Nagornih, M.O.; Sokolov, S.L.; Kosheleva, I.A.; Boronin, A.M. The Organization of Naphthalene Degradation Genes in Pseudomonas Putida Strain AK5. Res. Microbiol. 2013, 164, 244–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, Y.; Lee, Y.; Jeon, C.O. Biodegradation of Naphthalene, BTEX, and Aliphatic Hydrocarbons by Paraburkholderia Aromaticivorans BN5 Isolated from Petroleum-Contaminated Soil. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 24–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de Souza, E.S.; Texeira, R.A.; da Costa, H.S.C.; Oliveira, F.J.; Melo, L.C.A.; do Carmo Freitas Faial, K.; Fernandes, A.R. Assessment of Risk to Human Health from Simultaneous Exposure to Multiple Contaminants in an Artisanal Gold Mine in Serra Pelada, Pará, Brazil. Sci. Total Environ. 2017, 576, 683–695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Steffan, J.J.; Brevik, E.C.; Burgess, L.C.; Cerdà, A. The Effect of Soil on Human Health: An Overview. Eur. J. Soil Sci. 2018, 69, 159–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gundlapalli, M.; Sivagami, K.; Gopalakrishnan, M.; Harshini, P.; Janjaroen, D.; Ganesan, S. Biodegradation of Low Molecular Weight Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbons in Soil: Insights into Bacterial Activities and Bioremediation Techniques. Sustain. Chem. Environ. 2024, 7, 100146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barbosa, F.; Rocha, B.A.; Souza, M.C.O.; Bocato, M.Z.; Azevedo, L.F.; Adeyemi, J.A.; Santana, A.; Campiglia, A.D. Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbons (PAHs): Updated Aspects of Their Determination, Kinetics in the Human Body, and Toxicity. J. Toxicol. Environ. Heal. - Part B Crit. Rev. 2023, 26, 28–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Phale, P.S.; Shah, B.A.; Malhotra, H. Variability in Assembly of Degradation Operons for Naphthalene and Its Derivative, Carbaryl, Suggests Mobilization through Horizontal Gene Transfer. Genes (Basel). 2019, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mendes, G.P.; Magalhães, V.M.A.; Soares, L.C.R.; Aranha, R.M.; Nascimento, C.A.O.; Vianna, M.M.G.R.; Chiavone-Filho, O. Treatability Studies of Naphthalene in Soil, Water and Air with Persulfate Activated by Iron(II). J. Environ. Sci. 2020, 90, 67–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Preuss, R.; Angerer, J.; Drexler, H. Naphthalene - an Environmental and Occupational Toxicant. Int. Arch. Occup. Environ. Health 2003, 76, 556–576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tao, W.; Lin, J.; Wang, W.; Huang, H.; Li, S. Biodegradation of Aliphatic and Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbons by the Thermophilic Bioemulsifier-Producing Aeribacillus Pallidus Strain SL-1. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2020, 189, 109994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thimmarayan, S.; Mohan, H.; Manasa, G.; Natesan, K.; Mahendran, S.; Muthukumar Sathya, P.; Oh, B.T.; Ravi Kumar, R.; Sigamani Gandhimathi, R.; Jayaprakash, A.; et al. Biodegradation of Naphthalene – Ecofriendly Approach for Soil Pollution Mitigation. Environ. Res. 2024, 240, 117550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kaur, B.; Kaur, J.; Gupta, B. Augmentation of Degradation Prospects of Dioxygenases from the Crude Extract of an Efficient Bacterial Strain, Using Pyrene as Sole Carbon Source. Mater. Today Proc. 2020, 28, 1690–1694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, J.; Wu, R.; Peng, T.; Li, Q.; Wang, Q.; Wu, Y.; Song, X.; Lin, X. Low-Temperature Thermally Enhanced Bioremediation of Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbon-Contaminated Soil: Effects on Fate, Toxicity and Bacterial Communities. Environ. Pollut. 2023, 335, 122247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Z.; Wang, W.; Li, Y.; Yang, Q. Co-Metabolic Degradation of Naphthalene and Pyrene by Acclimated Strain and Competitive Inhibition Kinetics. J. Environ. Sci. Heal. - Part B Pestic. Food Contam. Agric. Wastes 2019, 54, 505–513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gou, Y.; Song, Y.; Yang, S.; Yang, Y.; Cheng, Y.; Wu, X.; Wei, W.; Wang, H. Low-Temperature Thermal-Enhanced Anoxic Biodegradation of Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbons in Aged Subsurface Soil. Chem. Eng. J. 2023, 454, 140143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carroll, K.C.; Brusseau, M.L.; Tick, G.R.; Soltanian, M.R. Rethinking Pump-and-Treat Remediation as Maximizing Contaminated Groundwater. Sci. Total Environ. 2024, 918, 170600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, S.; Zhong, M. Bioremediation of Petroleum-Contaminated Soil. In Environmental Chemistry and Recent Pollution Control Approaches; IntechOpen, 2019; Vol. 81, pp. 229–249. [Google Scholar]

- Leite, E.C.P.; Rodrigues, F.M.; Horimouti, T.S.T.; Shinzato, M.C.; Nakayama, C.R.; Freitas, J.G. de Thermally-Induced Changes in Tropical Soils Properties and Potential Implications to Sequential Nature-Based Solutions. J. Contam. Hydrol. 2021, 241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moreira, F.M.S.; Siqueira, J.O. Microbiologia e Bioquímica Do Solo, 2nd ed.; Editora UFLA: Lavras, 2006; ISBN 85-87692-33-x. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Q.; Guo, S.; Ali, M.; Song, X.; Tang, Z.; Zhang, Z.; Zhang, M.; Luo, Y. Thermally Enhanced Bioremediation: A Review of the Fundamentals and Applications in Soil and Groundwater Remediation. J. Hazard. Mater. 2022, 433, 128749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zeneli, A.; Kastanaki, E.; Simantiraki, F.; Gidarakos, E. Monitoring the Biodegradation of TPH and PAHs in Refinery Solid Waste by Biostimulation and Bioaugmentation. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2019, 7, 103054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z.; Hu, H.; Xu, P.; Tang, H. Soil Bioremediation by Pseudomonas Brassicacearum MPDS and Its Enzyme Involved in Degrading PAHs. Sci. Total Environ. 2022, 813, 152522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gou, Y.; Song, Y.; Li, P.; Wei, W.; Luo, N.; Wang, H. Study on the Accelerated Biodegradation of PAHs in Subsurface Soil via Coupled Low-Temperature Thermally Treatment and Electron Acceptor Stimulation Based on Metagenomic Sequencing. J. Hazard. Mater. 2024, 465, 133265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, Z.; Oury, B.M.; Xia, L.; Qin, Z.; Pan, X.; Qian, J.; Luo, F.; Wu, Y.; Liu, L.; Wang, W. The Ecological Response and Distribution Characteristics of Microorganisms and Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbons in a Retired Coal Gas Plant Post-Thermal Remediation Site. Sci. Total Environ. 2023, 857, 159314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Santos, R.D.; et al. Manual de Descrição e Coleta de Solo No Campo, Sociedade Brasileira de Ciência do Solo, Ed., 7th ed.; Sociedade Brasileira de Ciência do Solo: Viçosa, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Food and agriculture organization of the United Nations (FAO). World Reference Base; FAO: Rome, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Lima, O. de; Melloni, E.G.P.; Melloni, R.; Barison, M.R.; Curi, N. Soil Catenas in a Pilot Sub-Basin in the Region of Itajubá, Minas Gerais State, Brazil, for Environmental Planning. Semin. Ciências Agrárias 2021, 42, 1511–1528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- dos Santos, H.G.; Jacomine, P.K.T.; dos Anjos, L.H.C.; de Oliveira, V.Á.; Lumbreras, J.F.; Coelho, M.R.; de Almeida, J.A.; de Araújo Filho, J.C.; Lima, H.N.; Marques, F.A.; et al. Sistema Brasileiro de Classificação de Solos; 6 ed., rev.; Embrapa: Brasília, 2025; ISBN 978-85-7035-198-2. [Google Scholar]

- Teixeira, P.C.; Donagemma, G.K.; Fontana, A.; Teixeira, W.G. Manual de Métodos de Análise de Solo, 3rd ed.Solos, E., Ed.; Brasília, 2017; ISBN 9788570357717. [Google Scholar]

- Anderson, J.P.E. Soil Respiration. In Methods of soil analysis: Chemical and microbiological properties; PAGE, A.L., MILLER, R.H., KEENEY, D.R., Eds.; Soil Science Society of America/American Society of Agronomy: Madison, 1982; pp. 831–845. [Google Scholar]

- Ferreira, A.S.; Camargo, F.A.O.; Vidor, C. Utilização de Microondas Na Avaliação Da Biomassa Microbiana Do Solo. Rev. Bras. Ciência do Solo 1999, 23, 991–996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, T.; Domsch, K. The Metabolic Quotient for CO2 (QCO2) as a Specific Activity Parameter to Assess the Effects of Environmental Conditions, Such as Ph, on the Microbial Biomass of Forest Soils. Soil Biol. Biochem. 1993, 25, 393–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Döbereiner, J.; Baldani, V. L. D.; Baldani, J.I. Como Isolar e Identificar Bactérias Diazotróficas de Plantas Não-Leguminosas; Embrapa, Ed.; CNPAB: Itaguaí, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Melloni, R.; Nóbrega, R.S.A.; Moreira, F.M.S.; Siqueira, J.O. Densidade e Diversidade Fenotípica de Bactérias Diazotróficas Endofíticas Em Solos de Mineração de Bauxita, Em Reabilitação. Rev. Bras. Ciência do Solo 2004, 28, 85–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wollum II, A.G. Cultural Methods for Soil Microorganisms. In Methods of Soil Analysis: Part 2 Chemical and Microbiological Properties; American Society of Agronomy, Inc., 1982; pp. 781–802. [Google Scholar]

- US EPA – United States Environmental Protection Agency Ecological Effects Test Guidelines (OPPTS 850.4200): Seed Germination/Root Elongation Toxicity Test 1996, 8.

- OECD – Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development Test No. 208: Terrestrial Plant Test: Seedling Emergence and Seedling Growth Test 2006, 21.

- R Core Team R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing. R Foundation for Statistical Computing 2024.

- Oksanen, J.; Simpson, G.L.; Blanchet, F.G.; Kindt, R.; Legendre, P.; Minchin, P.R.; O’Hara, R.B.; Solymos, P.; Stevens, M.H.H.; Szoecs, E.; et al. Vegan: Community Ecology Package. CRAN Contrib. Packag. 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Kassambara, A.; Mundt, F. Factoextra: Extract and Visualize the Results of Multivariate Data Analyses. CRAN Contrib. Packag. 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Wickham, H.; Chang, W.; Henry, L.; Pedersen, T.L.; Takahashi, K.; Wilke, C.; Woo, K.; Yutani, H.; Dunnington, D.; van den Brand, T. Ggplot2: Create Elegant Data Visualisations Using the Grammar of Graphics. CRAN Contrib. Packag. 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Neuwirth, E. RColorBrewer: ColorBrewer Palettes. CRAN Contrib. Packag. 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Anderson, M.J. Permutational Multivariate Analysis of Variance (PERMANOVA ). In Wiley StatsRef: Statistics Reference Online; Wiley, 2017; pp. 1–15. ISBN 9781118445112. [Google Scholar]

- Du, J.; Liu, J.; Jia, T.; Chai, B. The Relationships between Soil Physicochemical Properties, Bacterial Communities and Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbon Concentrations in Soils Proximal to Coking Plants. Environ. Pollut. 2022, 298, 118823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, Y.A.; Grace Liu, P.W.; Whang, L.M.; Wu, Y.J.; Cheng, S.S. Effect of Soil Organic Matter on Petroleum Hydrocarbon Degradation in Diesel/Fuel Oil-Contaminated Soil. J. Biosci. Bioeng. 2020, 129, 603–612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Łyszczarz, S.; Lasota, J.; Błońska, E. Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbons Accumulation in Soil Horizons of Different Temperate Forest Stands. L. Degrad. Dev. 2022, 33, 945–959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Badzinski, C.; Ferraz Ramos, R.; Godoi, B.; Daroit, D.J. Soil Acidification and Impacts over Microbial Indicators during Attenuation of Soybean Biodiesel (B100) as Compared to a Diesel-Biodiesel Blend (B8). Fuel 2021, 289, 119989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, X.; Fan, F.; Zhou, H.; Zhang, P.; Zhao, G. Microbial Diversity and Activity of an Aged Soil Contaminated by Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbons. Bioprocess Biosyst. Eng. 2018, 41, 871–883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, G.; Guo, X.; Zhu, Y.; Liu, X.; Han, Z.; Sun, K.; Ji, L.; He, Q.; Han, L. The Effects of Different Biochars on Microbial Quantity, Microbial Community Shift, Enzyme Activity, and Biodegradation of Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbons in Soil. Geoderma 2018, 328, 100–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wołejko, E.; Jabłońska-Trypuć, A.; Wydro, U.; Butarewicz, A.; Łozowicka, B. Soil Biological Activity as an Indicator of Soil Pollution with Pesticides – A Review. Appl. Soil Ecol. 2020, 147, 103356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, T.H.; Domsch, K.H. Soil Microbial Biomass: The Eco-Physiological Approach. Soil Biol. Biochem. 2010, 42, 2039–2043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Behdarvandan, P.; Yengejeh, R.J.; Sabzalipour, S.; Roomiani, L.; Payandeh, K. Assessing the Efficiency of Floor Disinfection on Bacterial Decontamination in Sanandaj Governmental Hospitals. J Adv. Env. Heal. Res 2020, 8, 234–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ravi, A.; Ravuri, M.; Krishnan, R.; Narenkumar, J.; Anu, K.; Alsalhi, M.S.; Devanesan, S.; Kamala-Kannan, S.; Rajasekar, A. Characterization of Petroleum Degrading Bacteria and Its Optimization Conditions on Effective Utilization of Petroleum Hydrocarbons. Microbiol. Res. 2022, 265, 127184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, Y.; He, N.; Wen, X.; Xu, L.; Sun, X.; Yu, G.; Liang, L.; Schipper, L.A. The Optimum Temperature of Soil Microbial Respiration: Patterns and Controls. Soil Biol. Biochem. 2018, 121, 35–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pietikäinen, J.; Pettersson, M.; Bååth, E. Comparison of Temperature Effects on Soil Respiration and Bacterial and Fungal Growth Rates. FEMS Microbiol. Ecol. 2005, 52, 49–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anderson, T. -H; Domsch, K.H. Carbon Assimilation and Microbial Activity in Soil. Zeitschrift für Pflanzenernährung und Bodenkd. 1986, 149, 457–468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamazaki, Y.; Hasegawa, A.; Tian, X.; Suzuki, I.; Kobayashi, T.; Shimizu, T.; Inoue, D.; Ike, M. Effect of Elevated Temperature on Cis-1,2-Dichloroethene Dechlorination and Microbial Community Structure in Contaminated Soils—A Biostimulation Approach. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2020, 8, 103682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaur, G.; Krol, M.; Brar, S.K. Geothermal Heating: Is It a Boon or a Bane for Bioremediation? Environ. Pollut. 2021, 287, 117609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Łyszczarz, S.; Lasota, J.; Staszel, K.; Błońska, E. Effect of Forest and Agricultural Land Use on the Accumulation of Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbons in Relation to Soil Properties and Possible Pollution Sources. For. Ecol. Manage. 2021, 490, 119105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Couto, F.R.; Ferreira, A. de M.; Pontes, P.P.; Marques, A.R. Physical, Chemical and Microbiological Characterization of the Soils Contaminated by Iron Ore Tailing Mud after Fundão Dam Disaster in Brazil. Appl. Soil Ecol. 2021, 158, 103811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lamy, E.; Tran, T.C.; Mottelet, S.; Pauss, A.; Schoefs, O. Relationships of Respiratory Quotient to Microbial Biomass and Hydrocarbon Contaminant Degradation during Soil Bioremediation. Int. Biodeterior. Biodegrad. 2013, 83, 85–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rabani, M.S.; Sharma, R.; Singh, R.; Gupta, M.K. Characterization and Identification of Naphthalene Degrading Bacteria Isolated from Petroleum Contaminated Sites and Their Possible Use in Bioremediation. Polycycl. Aromat. Compd. 2022, 42, 978–989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, M.; Song, X.; Wang, Q.; Zhang, Z.; Zhang, M.; Chen, X.; Tang, Z.; Liu, X. Thermally Enhanced Biodegradation of Benzo[a]Pyrene and Benzene Co-Contaminated Soil: Bioavailability and Generation of ROS. J. Hazard. Mater. 2023, 455, 131494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Heidari, P.; Panico, A. Sorption Mechanism and Optimization Study for the Bioremediation of Pb(II) and Cd(II) Contamination by Two Novel Isolated Strains Q3 and Q5 of Bacillus Sp. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 4059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Palanivel, T.M.; Sivakumar, N.; Al-Ansari, A.; Victor, R. Bioremediation of Copper by Active Cells of Pseudomonas Stutzeri LA3 Isolated from an Abandoned Copper Mine Soil. J. Environ. Manage. 2020, 253, 109706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kaur, G.; Lecka, J.; Krol, M.; Brar, S.K. Novel BTEX-Degrading Strains from Subsurface Soil: Isolation, Identification and Growth Evaluation. Environ. Pollut. 2023, 335, 122303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Silva, Í.S.; Santos, E. da C. dos; Menezes, C.R. de; Faria, A.F. de; Franciscon, E.; Grossman, M.; Durrant, L.R. Bioremediation of a Polyaromatic Hydrocarbon Contaminated Soil by Native Soil Microbiota and Bioaugmentation with Isolated Microbial Consortia. Bioresour. Technol. 2009, 100, 4669–4675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moreira, A.A.; Mali, S.; Yamashita, F.; Bilck, A.P.; de Paula, M.T.; Merci, A.; Oliveira, A.L.M. de Biodegradable Plastic Designed to Improve the Soil Quality and Microbiological Activity. Polym. Degrad. Stab. 2018, 158, 52–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Onwosi, C.O.; Odimba, J.N.; Igbokwe, V.C.; Nduka, F.O.; Nwagu, T.N.; Aneke, C.J.; Eke, I.E. Principal Component Analysis Reveals Microbial Biomass Carbon as an Effective Bioindicator of Health Status of Petroleum-Polluted Agricultural Soil. Environ. Technol. 2020, 41, 3178–3190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dovletyarova, E.A.; Slukovskaya, M. V.; Ivanova, T.K.; Mosendz, I.A.; Novikov, A.I.; Chaporgina, A.A.; Soshina, A.S.; Myazin, V.A.; Korneykova, M. V.; Ettler, V.; et al. Sensitivity of Microbial Bioindicators in Assessing Metal Immobilization Success in Smelter-Impacted Soils. Chemosphere 2024, 359, 142296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, S.; Oh, B.; Kim, J. Effect of Various Amendments on Heavy Mineral Oil Bioremediation and Soil Microbial Activity. Bioresour. Technol. 2008, 99, 2578–2587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chibwe, L.; Geier, M.C.; Nakamura, J.; Tanguay, R.L.; Aitken, M.D.; Simonich, S.L.M. Aerobic Bioremediation of PAH Contaminated Soil Results in Increased Genotoxicity and Developmental Toxicity. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2015, 49, 13889–13898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zeng, J.; Li, Y.; Dai, Y.; Wu, Y.; Lin, X. Effects of Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbon Structure on PAH Mineralization and Toxicity to Soil Microorganisms after Oxidative Bioremediation by Laccase. Environ. Pollut. 2021, 287, 117581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Urionabarrenetxea, E.; Garcia-Velasco, N.; Anza, M.; Artetxe, U.; Lacalle, R.; Garbisu, C.; Becerril, T.; Soto, M. Application of in Situ Bioremediation Strategies in Soils Amended with Sewage Sludges. Sci. Total Environ. 2021, 766, 144099. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aswani, K.V.; Manu Sankar, V.; Kalamdhad, A.S.; Das, C. Microbial Enrichment-Based Bioremediation of Petroleum Refinery Wastewater- Enhanced Effluent Quality Assessment by Phytotoxicity Studies. Bioresour. Technol. Reports 2025, 29, 102043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hawrot-Paw, M.; Koniuszy, A.; Zając, G.; Szyszlak-Bargłowicz, J. Ecotoxicity of Soil Contaminated with Diesel Fuel and Biodiesel. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kwak, J. Il; Kim, D.; An, Y.J. Evidence of Soil Particle-Induced Ecotoxicity in Old Abandoned Mining Area. J. Hazard. Mater. 2024, 470, 134163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Caravaca, F.; Roldán, A. Assessing Changes in Physical and Biological Properties in a Soil Contaminated by Oil Sludges under Semiarid Mediterranean Conditions. Geoderma 2003, 117, 53–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zawierucha, I.; Malina, G.; Herman, B.; Rychter, P.; Biczak, R.; Pawlowska, B.; Bandurska, K.; Barczynska, R. Ecotoxicity and Bioremediation Potential Assessment of Soil from Oil Refinery Station Area. J. Environ. Heal. Sci. Eng. 2022, 20, 337–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hernandez, D.J.; David, A.S.; Menges, E.S.; Searcy, C.A.; Afkhami, M.E. Environmental Stress Destabilizes Microbial Networks. ISME J. 2021, 15, 1722–1734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Piccardi, P.; Vessman, B.; Mitri, S. Toxicity Drives Facilitation between 4 Bacterial Species. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2019, 116, 15979–15984. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peng, C.; Wan, X.; Zhang, J.; Zhang, B.; Wang, S.; Ma, T.; Bian, Y.; Wang, W. Bacterial Diversity and Competitors for Degradation of Hazardous Oil Refining Waste under Selective Pressures of Temperature and Oxygen. J. Hazard. Mater. 2022, 427, 128201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jiao, S.; Chen, W.; Wang, E.; Wang, J.; Liu, Z.; Li, Y.; Wei, G. Microbial Succession in Response to Pollutants in Batch-Enrichment Culture. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hanke, A.; Berg, J.; Hargesheimer, T.; Tegetmeyer, H.E.; Sharp, C.E.; Strous, M. Selective Pressure of Temperature on Competition and Cross-Feeding within Denitrifying and Fermentative Microbial Communities. Front. Microbiol. 2016, 6, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roy, A.; Dutta, A.; Pal, S.; Gupta, A.; Sarkar, J.; Chatterjee, A.; Saha, A.; Sarkar, P.; Sar, P.; Kazy, S.K. Biostimulation and Bioaugmentation of Native Microbial Community Accelerated Bioremediation of Oil Refinery Sludge. Bioresour. Technol. 2018, 253, 22–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, J.; Zhao, Q.; Zhao, Y.; Fu, H.; Li, X.; Huang, J.; Li, Y.; Hu, X.; Tian, S. Remediation of Heavy Metal-Contaminated Mine Soils Using Smoldering Combustion Technology. Environ. Technol. Innov. 2023, 32, 103333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lima, M.P.R.; Cardoso, D.N.; Soares, A.M.V.M.; Loureiro, S. Carbaryl Toxicity Prediction to Soil Organisms under High and Low Temperature Regimes. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2015, 114, 263–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, Z.; Hollebone, B.P.; Shah, K.; Yang, C.; Brown, C.E.; Dodard, S.; Sarrazin, M.; Sunahara, G. Biodegradation Potential Assessment by Using Autochthonous Microorganisms from the Sediments from Lac Mégantic (Quebec, Canada) Contaminated with Light Residual Oil. Chemosphere 2020, 239, 124796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Patowary, R.; Patowary, K.; Kalita, M.C.; Deka, S.; Borah, J.M.; Joshi, S.J.; Zhang, M.; Peng, W.; Sharma, G.; Rinklebe, J.; et al. Biodegradation of Hazardous Naphthalene and Cleaner Production of Rhamnolipids — Green Approaches of Pollution Mitigation. Environ. Res. 2022, 209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Imperato, V.; Portillo-Estrada, M.; McAmmond, B.M.; Douwen, Y.; Van Hamme, J.D.; Gawronski, S.W.; Vangronsveld, J.; Thijs, S. Genomic Diversity of Two Hydrocarbon-Degrading and Plant Growth-Promoting Pseudomonas Species Isolated from the Oil Field of Bóbrka (Poland). Genes (Basel). 2019, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Elumalai, P.; Parthipan, P.; Huang, M.; Muthukumar, B.; Cheng, L.; Govarthanan, M.; Rajasekar, A. Enhanced Biodegradation of Hydrophobic Organic Pollutants by the Bacterial Consortium: Impact of Enzymes and Biosurfactants. Environ. Pollut. 2021, 289, 117956. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kesavan, S.; Gousuddin Inamdar, M.; Muthunarayanan, V. Concentration of Benzene, Toluene, Napthalene and Acenaphthene on Selected Bacterial Species. Mater. Today Proc. 2020, 37, 273–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Wang, X.; Nong, S.; Bai, Z.; Han, N.; Wu, Q.; Huang, Z.; Ding, J. Display of a Novel Carboxylesterase CarCby on Escherichia Coli Cell Surface for Carbaryl Pesticide Bioremediation. Microb. Cell Fact. 2022, 21, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Al-Dossary, M.A.; Abood, S.A.; Al-Saad, H.T. Factors Affecting Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbon Biodegradation by Aspergillus Flavus. Remediation 2020, 30, 17–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Parameter | Unit | Result |

| Clay | % | 47,00 |

| Silt | % | 11,64 |

| Total sand | % | 41,36 |

| Organic Matter | dag/dm³ | 1,45 |

| pH | - | 5,04 |

| P | mg/dm³ | 32,6 |

| K | mg/dm³ | 233,6 |

| Ca | cmol/dm³ | 0,4 |

| Mg | cmol/dm³ | 0,17 |

| Al | cmol/dm³ | 0,9 |

| H+Al1 | cmol/dm³ | 8,28 |

| SB2 | cmol/dm³ | 1,2 |

| Ca/Mg | 2,49 | |

| Mg/K | 0,29 | |

| V3 | % | 12,66 |

| m4 | % | 42,86 |

| T5 | cmol/dm³ | 9,48 |

| Zn | mg/dm³ | 2,3 |

| Fe | mg/dm³ | 66,9 |

| Mn | mg/dm³ | 14,2 |

| Cu | mg/dm³ | 1,6 |

| B | mg/dm³ | 0,2 |

| S | mg/dm³ | -- |

| Time (Days) | p Value | ||

| Interaction | Temperature | Concentration | |

| T0 | - | - | 0,001* |

| T15 T30 |

0,001* | 0,001* | 0,078 |

| 0,001* | 0,001* | 0,1 | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).