1. Introduction

The cardiac sarcoidosis (CS) is an inflammatory disease of the heart, characterized by the formation of noncaseating granulomas within the myocardium, which can disrupt normal cardiac function and lead to a spectrum of severe complications. These complications include conduction disturbances, arrhythmias such as ventricular tachycardia and heart block, cardiomyopathy, heart failure, and even sudden cardiac death [

1]. Although sarcoidosis is a multisystem disorder, cardiac involvement is a major cause of morbidity and mortality and is often underdiagnosed due to its variable clinical presentation and the patchy distribution of myocardial lesions [

2]. Therefore, the clinical presentation of CS is highly variable, ranging from asymptomatic cases to life-threatening cardiac events. Common symptoms include palpitations, syncope, chest pain, shortness of breath, and peripheral edema, but up to 37% a significant proportion of patients may remain asymptomatic until advanced disease or a sentinel event occurs [

2,

3].

The diagnosis of CS is further complicated by its often patchy myocardial distribution and traditional diagnostic methods such as endomyocardial biopsy, electrocardiography and echocardiography have limited sensitivity and specificity. In this context, advanced noninvasive imaging techniques have become increasingly important and essential for timely diagnosis [

3].

Recent advances in imaging, particularly positron emission tomography/computed tomography (PET/CT), have greatly improved the ability to detect active myocardial inflammation, guide treatment decisions, and assess therapeutic response in CS [

1,

4,

5]. A recent systematic review and meta-analysis confirmed the prognostic value of cardiac PET imaging in predicting major adverse cardiac events and informing clinical management of CS [

4]. Furthermore, another recent review highlighted the central role of PET/CT in the assessment and follow-up of CS, emphasizing its utility in both diagnosis and treatment monitoring [

5]. PET/CT is considered a valuable tool for the early diagnosis and ongoing management of CS, enabling clinicians to tailor immunosuppressive therapy and monitor disease progression or remission [

1,

2,

3,

6,

7,

8].

However, despite the proven diagnostic accuracy of PET/CT, current reference standards for CS often rely on clinical criteria that may be less sensitive than PET imaging in detecting myocardial involvement. Moreover, despite the technological and methodological advancements, data reflecting the routine use and real-world effectiveness of PET/CT in clinical practice remain limited [

5].

Given these challenges and the evolving landscape of diagnostic imaging, further research is needed to clarify the optimal role of PET/CT in the management of CS.

The present study aims to report our experience with PET/CT in diagnosing and monitoring CS, emphasizing its value in clinical practice for improving patient outcomes.

2. Materials and Methods

We conducted a retrospective analysis of all PET/CT scans performed at our institution between January 2014 and March 2024 in patients with either newly diagnosed systemic sarcoidosis or clinical suspicion of CS. The study population included adult patients who underwent PET/CT as part of their diagnostic workup for sarcoidosis, as well as those referred for evaluation of possible cardiac involvement due to symptoms such as unexplained arrhythmias, conduction abnormalities, or heart failure, in accordance with current clinical practice guidelines [

8,

9,

10]. Exclusion criteria included patients with incomplete clinical data and prior immunosuppressive therapy before imaging (or contraindications to PET/CT).

For each patient, we systematically collected comprehensive clinical data and relevant medical history. Radiological data included findings from perfusion and metabolism PET/CT, cardiac magnetic resonance imaging (CMR), and echocardiography. When available, histological confirmation of sarcoidosis was obtained from endomyocardial or extracardiac biopsies.

All FDG PET/CT scans were performed following standardized protocols for CS assessment [

7]. Patient preparation included adherence to a high-fat, low-carbohydrate diet for at least 24 hours and a minimum fasting period of 12 hours prior to imaging to suppress physiological myocardial glucose uptake. Blood glucose levels were checked before tracer injection to ensure they were within acceptable limits. FDG was administered intravenously at a dose of approximately 4-5 MBq/kg. Dedicated cardiac scan following base of the skull to mid-thigh acquisition was performed between 60- and 90-minutes post-injection, using a dedicated 3D PET/CT scanner. PET images were corrected for detector efficiency (normalization), system dead time, random coincidences, scatter, and attenuation. Image reconstruction was performed using an ordered subsets expectation maximization (OSEM) iterative algorithm, with 2 iterations and 21 subsets, incorporating point spread function (PSF) modeling and time of flight (TOF) information. After reconstruction, a Gaussian filter with a 3-mm full width at half maximum (FWHM) was applied for smoothing. Image analysis was conducted using Syngo.via Siemens Healthineers software, with visual assessment performed by experienced nuclear medicine physicians, who assessed for patterns of FDG uptake suggestive of active myocardial inflammation [

11].

Myocardial perfusion 13N-NH3 PET/CT at rest was performed in patients who, according to CMR, demonstrated the presence of late gadolinium enhancement (LGE), suggestive of myocardial fibrosis, as well as in patients who were unable to undergo MRI.

13N-NH3 was administered intravenously at a standard dose of 370 MBq over 15 seconds and a dynamic scan of 10 min was simultaneously performed. The dynamic list sequence was reframed for qualitative assessment (static imaging 1x360s). Image reconstruction used a similar iterative algorithm as FDG PET, with corrections applied. Images were analyzed for perfusion defect and compared to FDG images.

In cases where both perfusion and metabolism PET/CT were available, the combined findings were used to characterize the spectrum of CS, presenting patterns of perfusion-metabolism mismatch or match [

9].

Imaging follow-up with FDG PET/CT was performed in patients who received immunosuppressive therapy, allowing for assessment of treatment response.

The diagnosis of CS was established according to the Heart Rhythm Society (HRS) consensus criteria, which incorporate clinical, imaging, and histological findings to improve diagnostic accuracy [

8]. In particular, Endomyocardial biopsy (EMB) was guided by three-dimensional electroanatomic ventricular mapping (3D-EAM) by Rhythmia system (Boston Scientific).

This comprehensive approach enabled us to evaluate the role of PET/CT in the diagnosis and monitoring of CS, as well as to correlate imaging findings with clinical outcomes and therapeutic responses (including the assessment of the presence of atrioventricular block and ventricular tachycardia) [

12,

13].

3. Results

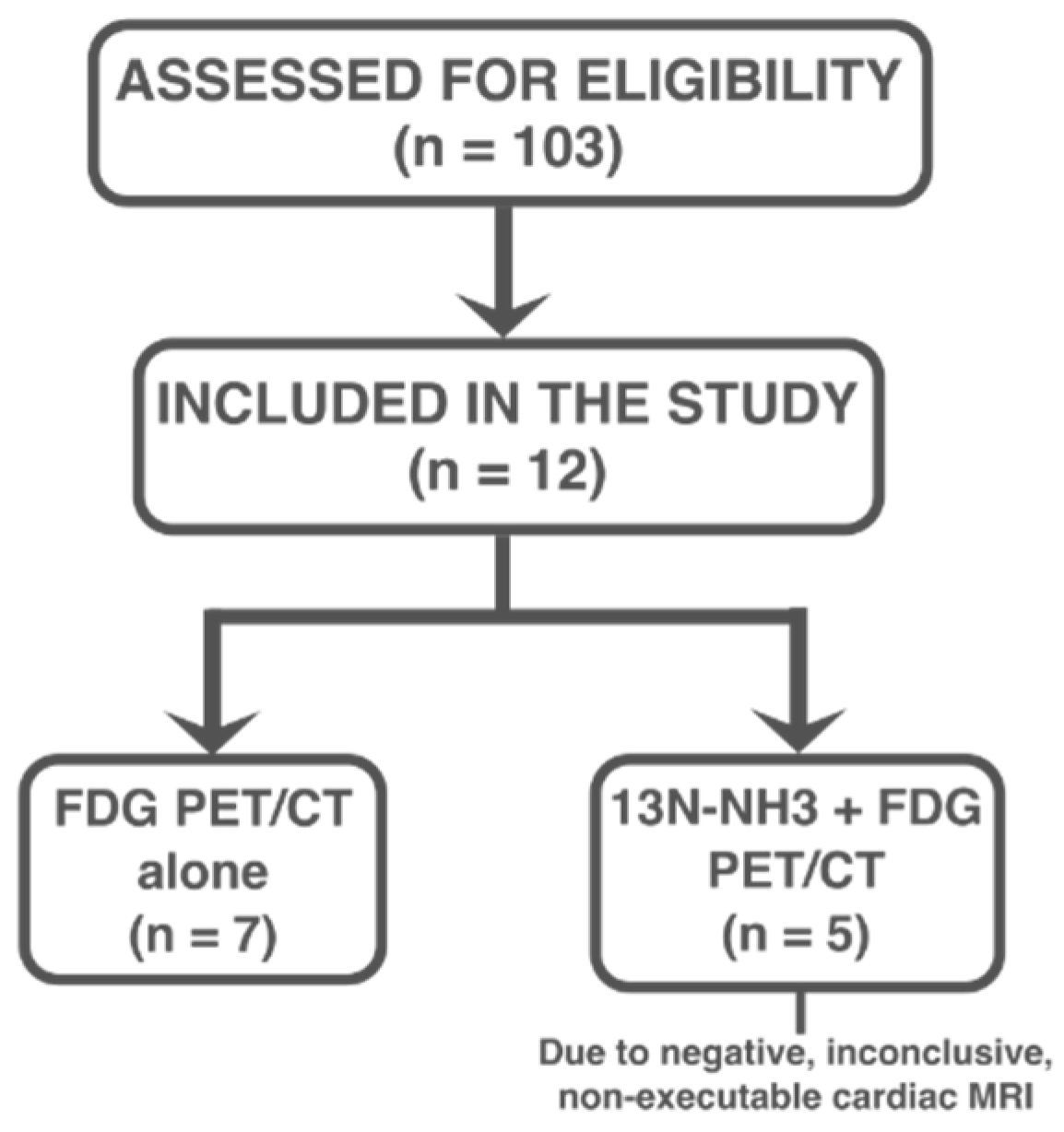

Among the 103 patients initially evaluated for suspected sarcoidosis over the study period, 12 (mean age 53 ± 14 years; 58.3% male) were ultimately diagnosed with cardiac involvement based on clinical, imaging, and, when available, histological criteria, and were included in the study. Of these 12 patients, 7 patients underwent FDG PET/CT alone, while 5 patients underwent both FDG PET/CT and

13N-NH

3 PET/CT imaging due to negative, inconclusive, or contraindicated CMR [

Figure 1].

For each patient included in the study, comprehensive clinical and diagnostic data were systematically collected, encompassing demographic information, age at diagnosis, sex and the results of key diagnostic investigations such as electrocardiography, echocardiography, CMR and histological findings, as detailed in

Table 1.

Clinically, at admission, sustained life-threatening arrhythmias were documented in 4 patients: 2 sustained ventricular tachycardia and 2 complete atrioventricular blocks, respectively. As a result, device therapy was required: 2 patients received an implantable cardioverter-defibrillator (ICD) while the remaining 2 underwent permanent pacemaker (PMK) implantation to manage significant conduction disturbances.

Cardiac magnetic resonance imaging (CMR) was performed in 4 patients; in 3 out of 4 patients CMR demonstrated late gadolinium enhancement (LGE) and regional wall motion abnormalities. In the first patient, LGE was localized to the basal inferolateral wall of the left ventricular (LV) septum. The second patient showed transmural and meso-epicardial LGE involving the basal, anterior, and anterolateral mid segments, as well as the LV septum, accompanied by severe hypokinesia/akinesia of the interventricular septum and the mid-basal anterior wall. In the third patient, CMR revealed a non-coronary distribution of contrast enhancement, which was compatible with, but not specific for, sarcoidosis. The fourth patient had a negative CMR, with no pathological findings detected.

All 12 patients demonstrated optimal suppression of physiological myocardial FDG uptake (FDG myocardial uptake less than blood pool), confirming the effectiveness of the pre-scan dietary preparation and fasting protocols. This allowed for clear visualization and assessment of pathological FDG uptake within the myocardium. Notably, 3 of these patients (25%) were found to have isolated CS, without evidence of extracardiac disease.

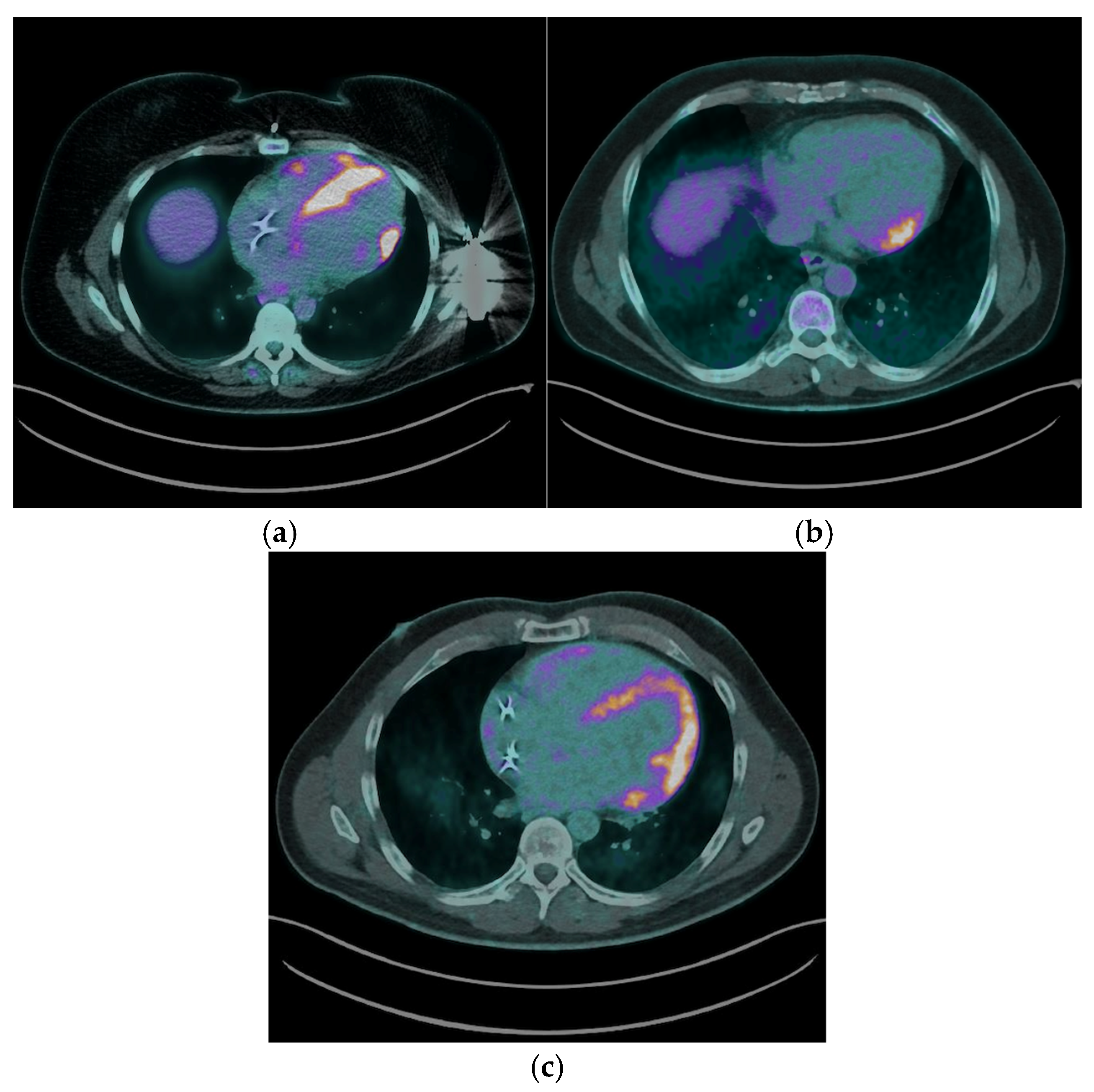

The most common myocardial FDG uptake pattern was focal patchy uptake, observed in 6 (50%) patients [

Figure 2a], which is considered highly suggestive of active granulomatous inflammation. Focal uptake was identified in 2 (16.7%) patients ([

Figure 2b], while 4 (33.3%) exhibited a focal on diffuse FDG uptake pattern, characterized by areas of intense focal uptake superimposed on a background of diffuse myocardial activity [

Figure 2c].

Right ventricular (RV) FDG uptake was observed in 50% of patients with CS in our cohort, as illustrated in

Figure 2a.

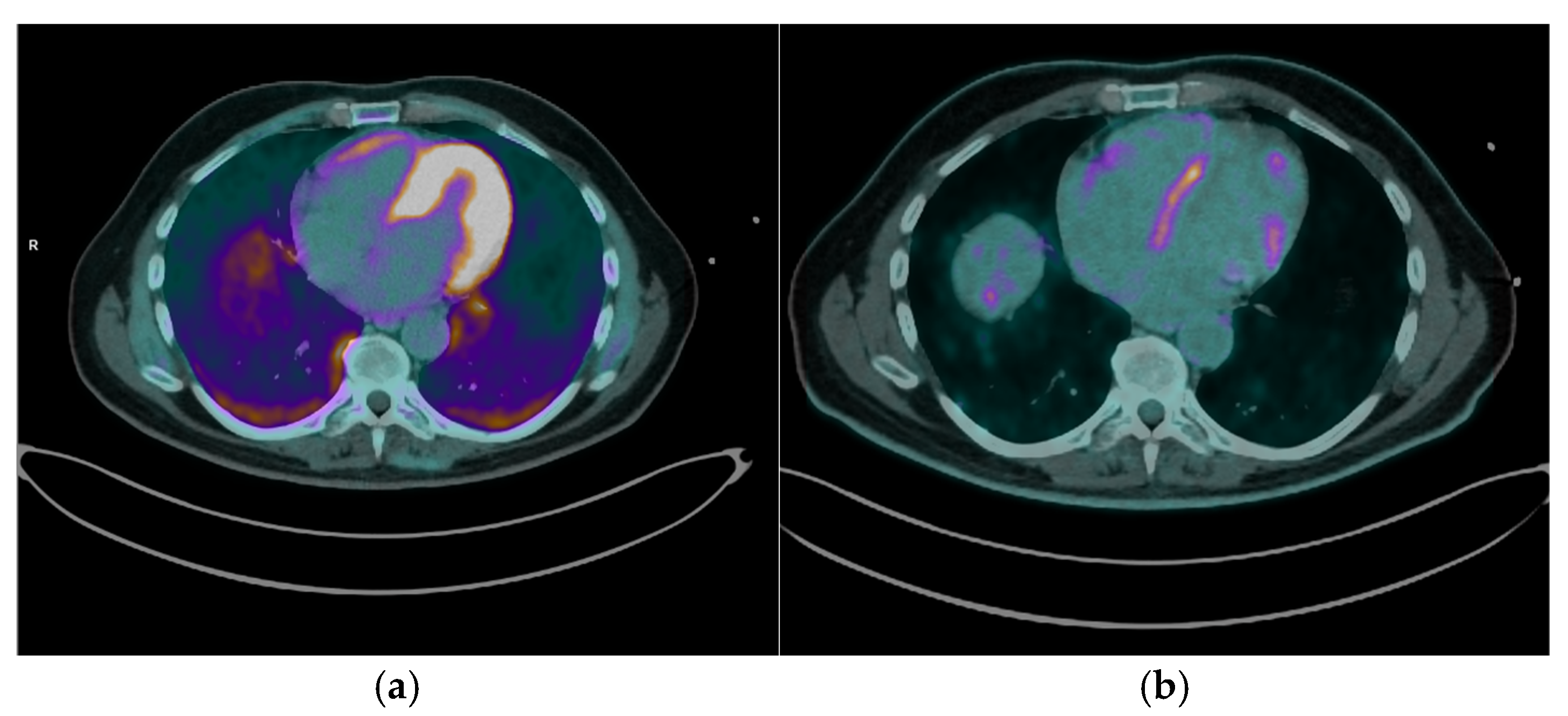

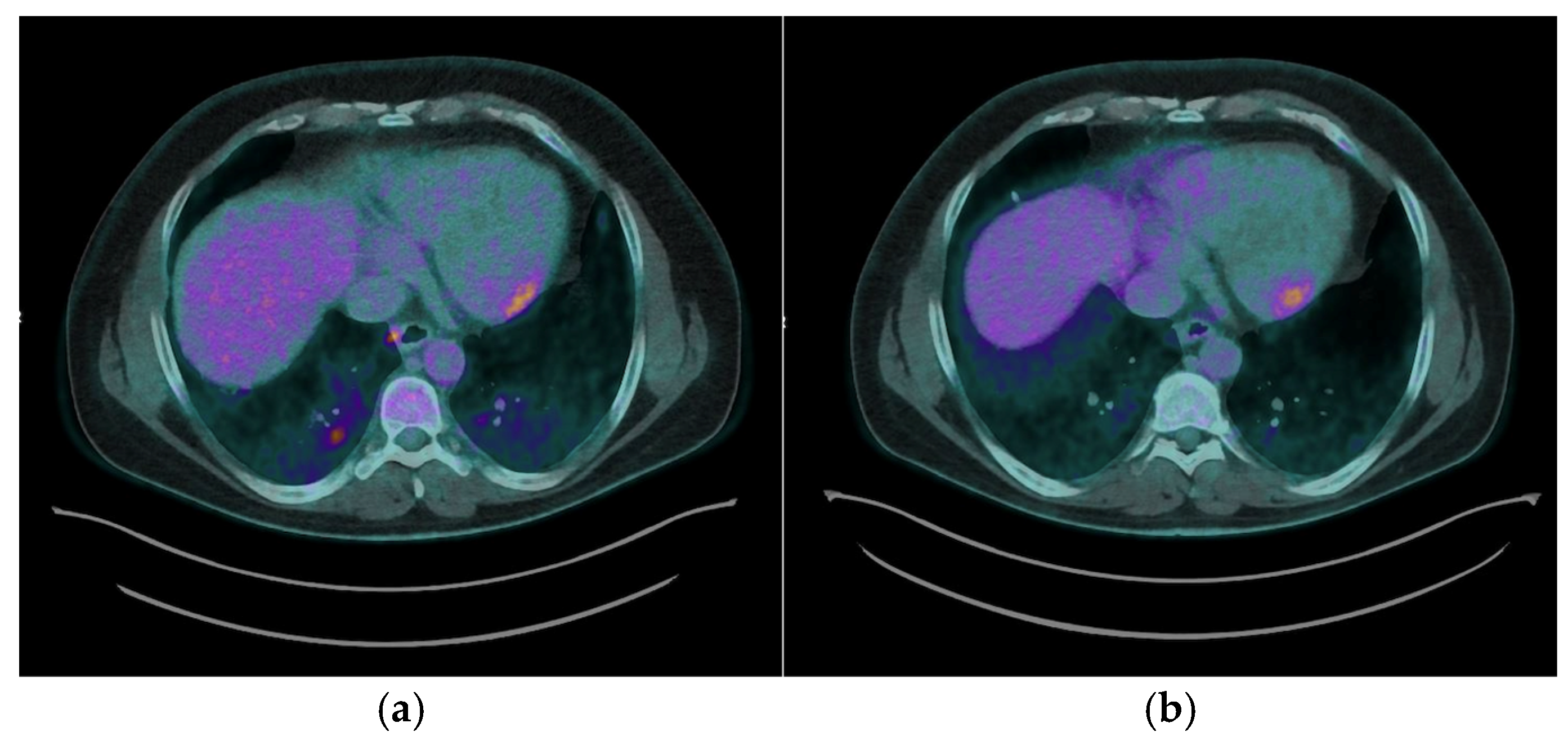

13N-NH

3 PET/CT was performed in 5 out of the 12 patients (41.7%) diagnosed with CS. Among these, 4 patients (80%) showed concomitant perfusion defects consistent with fibrosis [

Figure 3], while in 1 patient (20%) the

13N-NH₃ PET/CT was negative, indicating normal resting myocardial perfusion. This combined assessment enables characterization of the full spectrum of CS, ranging from isolated inflammation (normal perfusion with increased FDG) to isolated fibrosis (perfusion defects without FDG uptake), and matched perfusion-metabolism abnormalities where fibrosis and active inflammation coexist.

Endomyocardial biopsy (EMB) guided by three-dimensional electroanatomic mapping (3D-EAM) was conducted in 4 patients demonstrating positive findings on FDG PET/CT, without histological evidence of cardiac sarcoidosis.

Following the diagnosis of CS, all patients were initiated on immunosuppressive therapy. The majority (11 patients, 91.7%) received a combination regimen of prednisone and methotrexate, which is consistent with current recommendations for managing active cardiac involvement [

2,

3]. One patient (8.3%) was treated with prednisone monotherapy.

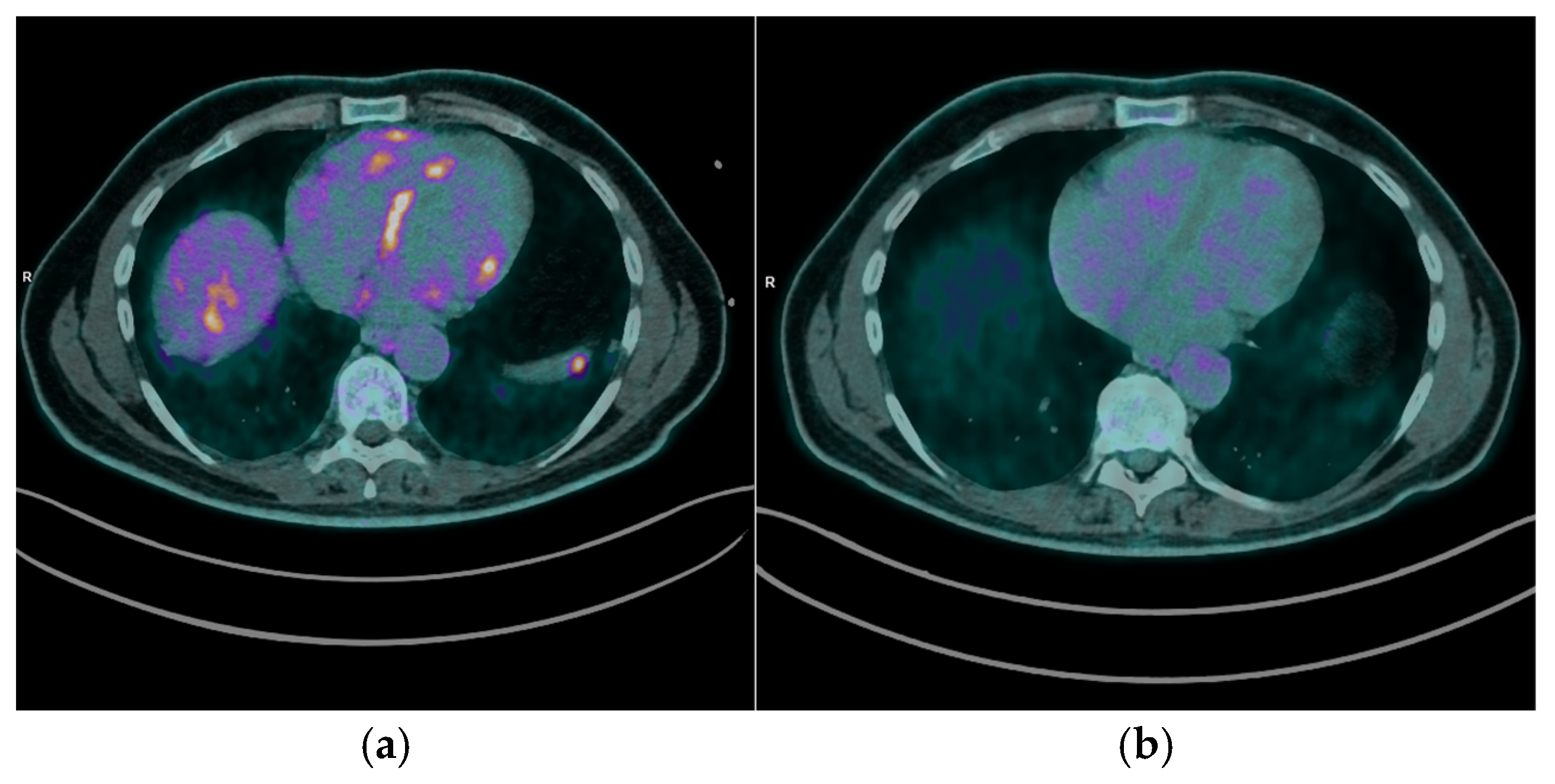

After a median follow-up period of 10 months (range 38 months), 9 patients (75%) underwent FDG PET/CT imaging to assess the response to immunosuppressive therapy. Of these, 7 patients (77.8%) demonstrated a complete cardiac metabolic response, characterized by the absence of abnormal myocardial FDG uptake on follow-up scans [

Figure 4]. The remaining 2 patients (22.2%) exhibited stable cardiac disease, with persistent but non-progressive FDG uptake patterns [

Figure 5].

Some cardiac events occurred during follow-up, including 1 patient (8.3%) with sustained ventricular tachycardia refractory to pharmacological therapy treated with targeted radiation therapy, and another (8.3%) who experienced heart failure with preserved ejection fraction.

Most patients continued their immunosuppressive therapy regimen (11 patients, 91%), with plans for further PET/CT reassessment scheduled at 6- to 8-month intervals, in line with current recommendations for ongoing disease surveillance [

12]. In 3 cases where a complete cardiac response was achieved, clinicians opted to reduce the prednisone dosage while maintaining methotrexate therapy, reflecting a tailored approach to minimize corticosteroid exposure while sustaining disease remission. This stepwise reduction of immunosuppression is supported by imaging evidence of disease quiescence by FDG PET TC in concordant 25% patients.

4. Discussion

This study further underscores the crucial role of PET/CT imaging in the diagnosis and management of CS [

1,

2,

3,

7]. Our real-world cohort reveals the diversity of clinical and imaging presentations associated with CS, emphasizing the need for advanced, multimodal imaging to achieve accurate disease characterization and therapeutic guidance.

It is essential to consider CS even in the absence of systemic manifestations (among the 103 patients evaluated for suspected sarcoidosis during the study period, 12 individuals, 11.7%, presented with cardiac manifestations only, without evidence of systemic involvement).

The capability of FDG PET/CT to detect active myocardial inflammation at an early stage enables clinicians to initiate timely therapeutic interventions, potentially preventing severe complications such as life-threatening brady and tachy-arrhythmias. Early identification of cardiac involvement is vital, given the often subtle or nonspecific clinical presentations and the limitations of conventional diagnostic methods like EBM. One significant challenge in diagnosing CS is the low sensitivity of EBM, primarily due to the patchy and focal nature of granulomatous infiltration within the myocardium [

8]. In our cohort, only 4 patients underwent EMB, without histological diagnosis of CS, highlighting the limitations of histological confirmation although guided by ventricular 3D-EAM [

14].

The integration of perfusion imaging with

13N-NH

3 PET/CT enhances the diagnostic and prognostic value of PET/CT. By distinguishing areas of perfusion defects (indicative of fibrosis) from regions of increased FDG uptake (active inflammation), clinicians can fully characterize the spectrum of disease, from isolated inflammation to fibrosis, and overlapping pathology, for comprehensive disease evaluation, prognosis, and guiding tailored therapeutic strategies [

9].

Cardiac magnetic resonance (CMR) imaging is the first-line advanced diagnostic test for CS; however, it was not feasible for all patients and sometimes produced inconclusive results, further illustrating the diagnostic gap that PET/CT can address. In this regard, our findings confirm that FDG PET/CT is highly sensitive for detecting active myocardial inflammation, as demonstrated by the characteristic uptake patterns observed.

Moreover, our findings reinforce the utility of PET/CT in guiding individualized treatment strategies. By offering a non-invasive assessment of myocardial inflammatory activity, PET/CT allows clinicians to tailor immunosuppressive therapy based on objective evidence of disease activity or remission. This approach facilitates the adjustment of immunosuppressive regimens, such as corticosteroids and steroid-sparing agents, while minimizing unnecessary exposure to medication side effects, thereby improving patient safety and quality of life [

13]. Serial PET/CT imaging enhances disease monitoring by enabling quantitative and qualitative assessments of therapeutic response. In our cohort, follow-up PET/CT scans confirmed a complete metabolic response in most patients (77.8%), supporting decisions to taper immunosuppressive therapy in selected cases (25%). Conversely, persistent or recurrent FDG uptake necessitated continued or intensified treatment (75%), underscoring the role of PET/CT in dynamic, patient-centered clinical management.

Despite these positive outcomes, our cohort experienced some cardiac events during follow-up, including one patient who developed sustained ventricular tachycardia, refractory to conventional therapy and managed with targeted radiation therapy, and another who experienced heart failure with preserved ejection fraction. These findings highlight that patients with CS remain at risk for complications, emphasizing the need for ongoing clinical vigilance and periodic imaging reassessment. They also reinforce the central role of FDG PET/CT not only in initial diagnosis but also in the longitudinal management of CS. Serial imaging allows clinicians to monitor therapeutic responses, guide adjustments in immunosuppressive regimens, and promptly identify patients at risk for adverse cardiac events, thereby improving overall patient outcomes.

Despite the promising diagnostic and prognostic capabilities of PET/CT in CS, our study underscores the need for larger prospective multicenter trials to validate standardized imaging protocols and the routinary use of PET/CT. Clinically, PET/CT facilitates early detection of active myocardial inflammation, enabling timely initiation and adjustment of immunosuppressive therapy. This tailored approach may reduce the incidence of adverse cardiac events and improve long-term outcomes. Incorporating PET/CT into a multidisciplinary care model, alongside CMR and clinical evaluation, is essential for a comprehensive management of CS.

Future research should focus on integrating PET/CT findings with emerging biomarkers and genetics data to enhance diagnostic accuracy and personalize treatment. Technological advancements, such as artificial intelligence and machine learning, hold potential to improve image analysis and reduce interobserver variability. Additionally, novel PET tracers targeting specific inflammatory pathways may offer more precise disease characterization.

5. Conclusions

In summary, our experience aligns with and expands upon existing literature, confirming that PET/CT, particularly when combining metabolic and perfusion imaging, provides a comprehensive, non-invasive approach for the diagnosis, risk assessment, and management of CS. The ability to visualize the spectrum of disease activity and tailor therapy accordingly has the potential to enhance both short- and long-term patient outcomes.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study (ID 2415).

Data Availability Statement

The data supporting the findings of this study are not publicly available due to privacy and ethical restrictions. Further information may be provided by the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| CS |

cardiac sarcoidosis |

| CMR |

cardiac magnetic resonance |

| EMB |

endomyocardial biopsy |

| FDG |

18F-fluorodeoxiglucose |

| LGE |

late gadolinium enhancement |

| LV |

left ventricle |

| RV |

right ventricle |

References

- Saric P, Young KA, Rodriguez-Porcel M, Chareonthaitawee P. PET Imaging in Cardiac Sarcoidosis: A Narrative Review with Focus on Novel PET Tracers. Pharmaceuticals (Basel). 2021 Dec 9;14(12):1286. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Shah HH, Zehra SA, Shahrukh A, Waseem R, Hussain T, Hussain MS, Batool F and Jaffer M (2023) Cardiac sarcoidosis: a comprehensive review of risk factors, pathogenesis, diagnosis, clinical manifestations, and treatment strategies. Front. Cardiovasc. Med. 10:1156474. [CrossRef]

- Pour-Ghaz, I.; Kayali, S.; Abutineh, I.; Patel, J.; Roman, S.; Nayyar, M.; Yedlapati, N. Cardiac Sarcoidosis: Pathophysiology, Diagnosis, and Management. Hearts 2021, 2, 234–250. [CrossRef]

- Kafil TS, Shaikh OM, Fanous Y, Benjamen J, Hashmi MM, Jawad A, Dahrouj T, Abazid RM, Swiha M, Romsa J, Beanlands RSB, Ruddy TD, Mielniczuk L, Birnie DH, Tzemos N. Risk Stratification in Cardiac Sarcoidosis With Cardiac Positron Emission Tomography: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. JACC Cardiovasc Imaging. 2024 Sep;17(9):1079-1097. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu A, Munemo LT, Martins N, Kouranos V, Wells AU, Sharma RK, Wechalekar K. Assessment of Cardiac Sarcoidosis with PET/CT. J Nucl Med Technol. 2025 Jun 4;53(2):123-129. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bois JP, Muser D, Chareonthaitawee P. PET/CT Evaluation of Cardiac Sarcoidosis. PET Clin. 2019 Apr;14(2):223-232. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abikhzer G, Treglia G, Pelletier-Galarneau M, Buscombe J, Chiti A, Dibble EH, Glaudemans AWJM, Palestro CJ, Sathekge M, Signore A, Jamar F, Israel O, Gheysens O. EANM/SNMMI guideline/procedure standard for [18F]FDG hybrid PET use in infection and inflammation in adults v2.0. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2025 Jan;52(2):510-538. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Birnie DH, Sauer WH, Bogun F, Cooper JM, Culver DA, Duvernoy CS, Judson MA, Kron J, Mehta D, Cosedis Nielsen J, Patel AR, Ohe T, Raatikainen P, Soejima K. HRS expert consensus statement on the diagnosis and management of arrhythmias associated with cardiac sarcoidosis. Heart Rhythm. 2014 Jul;11(7):1305-23. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Al Hayja MA, Vinjamuri S. Cardiac sarcoidosis: the role of cardiac MRI and 18F-FDG-PET/CT in the diagnosis and treatment follow-up. Br J Cardiol. 2023 Feb 21;30(1):7. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Tuominen H, Haarala A, Tikkakoski A, Kähönen M, Nikus K, Sipilä K. FDG-PET in possible cardiac sarcoidosis: Right ventricular uptake and high total cardiac metabolic activity predict cardiovascular events. J Nucl Cardiol. 2021 Feb;28(1):199-205. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Kaneko K, Nagao M, Yamamoto A, Sakai A, Sakai S. FDG uptake patterns in isolated and systemic cardiac sarcoidosis. J Nucl Cardiol. 2023 Jun;30(3):1065-1074. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chareonthaitawee P, Beanlands RS, Chen W, Dorbala S, Miller EJ, Murthy VL, Birnie DH, Chen ES, Cooper LT, Tung RH, White ES, Borges-Neto S, Di Carli MF, Gropler RJ, Ruddy TD, Schindler TH, Blankstein R. Joint SNMMI-ASNC expert consensus document on the role of 18F-FDG PET/CT in cardiac sarcoid detection and therapy monitoring. J Nucl Cardiol. 2017 Oct;24(5):1741-1758. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cheng RK, Kittleson MM, Beavers CJ, Birnie DH, Blankstein R, Bravo PE, Gilotra NA, Judson MA, Patton KK, Rose-Bovino L; American Heart Association Heart Failure and Transplantation Committee of the Council on Clinical Cardiology, and Council on Cardiovascular and Stroke Nursing. Diagnosis and Management of Cardiac Sarcoidosis: A Scientific Statement From the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2024 May 21;149(21):e1197-e1216. . Erratum in: Circulation. 2024 Aug 20;150(8):e197. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0000000000001275. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Narducci ML, La Rosa G, Pinnacchio G, Inzani F, d’Amati G, Perna F, Bencardino G, D’Amario D, Pieroni M, Dello Russo A, Casella M, Pelargonio G, Crea F. Assessment of patients presenting with life-threatening ventricular arrhythmias and suspected myocarditis: The key role of endomyocardial biopsy. Heart Rhythm. 2021 Jun;18(6):907-915. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).