1. Introduction

Cardiac amyloidosis is a form of infiltrative cardiac disease characterized by the deposition of amyloid fibrils within the myocardial interstitium, which can culminate in a restrictive cardiomyopathy. It may present as heart failure or by manifestations of concomitant systemic amyloidosis, invariably impacting the quality of life and patient survival. Recent advancements in imaging techniques and the development of novel biomarkers have enhanced diagnostic precision, facilitating the differentiation between the two principal forms of cardiac amyloidosis: light-chain amyloidosis (AL) and transthyretin amyloidosis (ATTR). More importantly, treatment modalities have progressed markedly, particularly with the introduction of innovative pharmacological agents that have the potential to modify disease progression in ATTR amyloidosis, as well as targeted chemotherapy options for AL amyloidosis. [

1] In contrast, cardiac sarcoidosis is an infiltrative cardiomyopathy resulting from granulomatous inflammation of the myocardium. Although cardiac sarcoidosis (CS) has been noted in only approximately 5% of cases of sarcoidosis, autopsy studies indicate that involvement may be as prevalent as 25%. [

2] Common presentations include conduction disease, ventricular arrhythmias, and/or left ventricular dysfunction. [

2]

The primary objective of this study is to evaluate and compare the clinical presentations, imaging characteristics, and outcomes of patients diagnosed with cardiac amyloidosis with those of patients diagnosed with cardiac sarcoidosis. We propose that, despite both these conditions being “infiltrative diseases” with some overlapping features, there are significant differences in diagnostic findings, clinical outcomes, and responses to treatment strategies.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design, Setting, Patient Enrollment, and Data Collection

This was a retrospective, observational cohort study. Patients were selected based on diagnostic codes for cardiac amyloidosis or cardiac sarcoidosis, as queried in the Mount Sinai Morningside Electronic Medical Record (EMR) System. The CS database screened all patients with a reported diagnosis from January 2023 to October 2023, while the CA database screened all patients with a reported diagnosis from 2017 to 2023. Duplicate records were eliminated. For cardiac amyloidosis, the inclusion criteria included confirmation via histological evidence of amyloid deposits (using Congo red staining) or typical imaging features on PYP scan. For cardiac sarcoidosis, the inclusion criteria followed those established by the Heart Rhythm Society (HRS) and the Japanese Circulation Society (JCS), which included evidence from biopsy-proven non-caseating granulomas and supportive cardiac imaging features. Pertinent clinical, laboratory, and imaging data were collected.

2.2. Outcome Measures

The primary outcome measures for this study were categorized into three main areas: Imaging Differences, Clinical Outcomes, and Management. Imaging Differences encompassed characteristics from transthoracic echocardiography (TTE) such as ejection fraction, interventricular septal thickness, left ventricular posterior wall thickness, and left atrial volume index, alongside cardiovascular magnetic resonance (CMR) imaging findings, including T1 and extracellular volume (ECV) values and the presence & pattern of late gadolinium enhancement (LGE). Additional imaging outcomes from positron emission tomography (PET) scans and PYP scans were also included. Clinical Outcomes focused on the occurrence of atrial fibrillation, atrial flutter, ventricular tachycardia, the placement of implantable cardioverter-defibrillators (ICD), and mortality rates. Lastly, management examined the initiation of disease-specific treatments, specifically Tafamidis for transthyretin amyloid cardiomyopathy and various forms of immunosuppression for sarcoidosis. Very recently introduced disease-modifying therapies for transthyretin amyloid cardiomyopathy, such as acoramidis and vutrisiran, were omitted.

2.3. Statistical Analysis

Data were analyzed using SPSS statistical software. Continuous variables are presented as means ± standard deviations, and categorical variables as counts and percentages. Chi-square tests were used to examine associations between categorical variables, and independent samples T-tests were used to compare continuous variables between groups. A significance level of p < 0.05 was set for all tests.

2.4. Missing Data

The study employed a complete-case analysis approach due to its retrospective design; therefore, only variables with complete data were included in the final analyses. For primary outcomes and critical imaging data, missing data did not exceed 5%, ensuring robustness and validity of the analysis. The retrospective design ensured there were no losses to follow-up.

3. Results

3.1. Demographics

The demographic analysis of the study population revealed statistically significant differences in several variables between patients with cardiac amyloidosis and those with cardiac sarcoidosis. The mean age for patients with cardiac amyloidosis was significantly higher at 78.2 years compared to 62.0 years for those with sarcoidosis (p = 0.01). Rates of smoking were notably lower in the sarcoidosis group (18.5%) compared to the amyloidosis group (36.8%), showing a significant difference (p = 0.01). Hypertension was more prevalent among amyloidosis patients (87.2%) than sarcoidosis patients (75.0%), with a statistically significant p-value of 0.02. Significant differences were also observed in the family history of disease, with 24.8% of amyloidosis patients reporting a family history, compared to only 5.4% in the sarcoidosis group (p = 0.01). Additionally, significant disparities were found in previous stent placement (23.2% in amyloidosis vs. 5.4% in sarcoidosis, p = 0.01) and the prevalence of heart failure (93.6% in amyloidosis vs. 68.5% in sarcoidosis, p = 0.01). No significant differences were found in sex distribution, body mass index, diabetes mellitus, hyperlipidemia, myocardial infarction, and history of coronary artery bypass grafting (CABG) between the two groups. (

Table 1.)

3.2. Imaging Results

Imaging comparisons between CA and CS groups revealed notable differences across several modalities. In transthoracic echocardiography (TTE), the interventricular septal (IVS) thickness and left ventricular posterior wall thickness (LVPWd) were significantly greater in cardiac amyloidosis patients, with mean thicknesses of 1.57 ± 0.35 cm and 1.45 ± 0.34 cm, respectively, compared to 1.10 ± 0.25 cm and 1.04 ± 0.18 cm in sarcoidosis patients (p = 0.01 for both). Conversely, there was no significant difference in ejection fraction (EF) and left atrium (LA) volume index between the groups. Mitral regurgitation (MR) was more severe in the amyloidosis group, with 5.0% experiencing severe MR compared to only 1.1% in the sarcoidosis group (p = 0.01).

In CA, of the 19 out of 125 patients who underwent CMR, the results showed a mean T1 mapping value of 1119 ± 59 ms and an ECV of 56.9 ± 14.7%, indicating significant myocardial infiltration. PYP highlighted extensive amyloid deposition, with 73 (58.4%) patients displaying high uptake (Grade 3) and 22 (17.6%) showing moderate uptake (Grade 2).

Conversely, in the cardiac sarcoidosis group, out of 91 patients, 77 had CMR, with 51 (66%) showing LGE. PET was performed in 80 patients, where intense fluorodeoxyglucose (FDG) uptake was noted in 72 (90%) of the cases, and a ‘mismatch pattern’ (FDG uptake in the same areas as perfusion defects) was identified in 40 (50%) of these patients. (

Table 2.)

3.3. Outcome

The outcome analysis for patients with cardiac amyloidosis and cardiac sarcoidosis shows significant differences in clinical endpoints, which may reflect the underlying pathophysiological differences between these two conditions. Atrial fibrillation was more common in cardiac amyloidosis (57.6%) compared to cardiac sarcoidosis (45.7%), though the difference was not statistically significant (p = 0.08). However, significant disparities were observed in other areas: atrial flutter occurred in 31.2% of amyloidosis patients versus 17.4% of sarcoidosis patients (p = 0.02); ventricular tachycardia was markedly higher in the sarcoidosis group, at 53.3%, compared to 10.7% in the amyloidosis group (p = 0.01). The placement of implantable cardioverter-defibrillators (ICDs) was significantly more common in patients with cardiac sarcoidosis (66.3%) than in those with cardiac amyloidosis (13.0%), possibly reflecting a greater incidence of life-threatening arrhythmias in sarcoidosis (p = 0.01). (

Table 3.)

3.4. Therapy

The analysis of management strategies between the CA and CS groups demonstrated significant differences in treatment approaches, reflecting the distinct pathophysiology of these conditions. In cardiac amyloidosis, a substantial majority of the patients, 70.4% (88 out of 125), were treated with Tafamidis, a medication specifically targeting transthyretin stabilization to mitigate the progression of amyloidosis. Conversely, in the cardiac sarcoidosis group, a lower proportion, 39.6% (36 out of 92), received immunosuppressive therapies, which are standard in managing the inflammatory aspects of sarcoidosis. This significant difference in treatment modalities (p = 0.01) highlights the need for tailored therapeutic strategies to address the specific clinical manifestations and disease mechanisms inherent to each of these severe cardiac conditions (

Table 4).

4. Discussion

Differentiating cardiac amyloidosis from cardiac sarcoidosis is of critical clinical importance, as both fall under the umbrella of infiltrative cardiomyopathies but represent fundamentally distinct pathophysiological processes with divergent clinical manifestations, imaging profiles, and disease trajectories. CA is characterized by the extracellular deposition of amyloid fibrils, leading primarily to restrictive physiology and left ventricular hypertrophy. [

1] In contrast, CS is driven by granulomatous inflammation, which predominantly results in conduction abnormalities and ventricular arrhythmias, without producing significant LVH on imaging. [

2]

These disorders are positioned at different points along the spectrum of cardiomyopathy. Though they are often clubbed together by virtue of the “infiltrative” pathophysiologic bases, they are very different conditions: CA often presents as a progressive, infiltrative disease that progresses to a restrictive cardiomyoathy (hypertrophied myocardium with severe diastolic dysfunction), while CS behaves more as an inflammatory disorder with a high arrhythmic burden and only a portion of these progress to dilated or restrictive cardiomyopathies. [

3,

4] Moreover, their natural histories and prognoses are shaped by their underlying biology; untreated CA can rapidly progress to refractory heart failure, whereas CS has a waxing and waning clinical course with episodes of inflammation and clinical quiescence between these episodes[

5,

6]

Given these differences, early and accurate differentiation is essential not only for prognostication but also for guiding therapy: CA management centers around amyloid-directed therapies, such as tafamidis (for ATTR) or chemotherapy (for AL), whereas CS requires immunosuppressive agents to curb granulomatous myocardial inflammation and prevent arrhythmic complications. [

1,

2] Therefore, recognizing the unique clinical trajectories, imaging hallmarks, and treatment needs of CA and CS is paramount for clinicians aiming to improve patient outcomes in these high-risk populations.

4.1. Demographics Discussion

Our cohort demonstrated a significantly older age among patients with cardiac amyloidosis (78.2 ± 11.3 years) compared to those with cardiac sarcoidosis (62.0 ± 11.9 years), consistent with previous reports that document advanced age distributions in amyloid populations, particularly among male patients. [

7,

8] In contrast, cardiac sarcoidosis cohorts, such as the Finnish registry, have described a higher proportion of females, underlining demographic variability in sarcoidosis that can be influenced by sex and race. [

9,

10,

11] Although the body mass index (BMI) did not differ significantly between the two groups (27.7 ± 5.8 vs. 29.0 ± 5.6, p = 0.13), the clinical relevance of BMI in either disease remains unclear, given that disease severity and organ involvement are often more critical factors. [

7]

Hypertension was significantly more frequent in the amyloidosis cohort (87.2%) compared to the sarcoidosis cohort (75.0%), aligning with existing literature that suggests elevated blood pressure in amyloidosis may indicate a more severe phenotype. [

12] Nonetheless, other studies point out that specific cardiac amyloidosis subsets display lower rates of hypertension, signifying heterogeneous clinical presentations. [

13] For sarcoidosis, our findings resonate with pooled analyses noting considerable rates of hypertension (28.8%) and an elevated risk of heart failure, both underscoring the complexity of managing cardiac sarcoidosis. [

14,

15] Long-term corticosteroid use may further compound metabolic issues, contributing to hypertension and diabetes mellitus. [

16] Smoking habits also differed notably, with fewer sarcoidosis patients (18.5%) being smokers than those with amyloidosis (36.8%), which aligns with studies indicating that nonsmokers might exhibit a higher degree of myocardial inflammation in cardiac sarcoidosis. [

17] Meanwhile, hyperlipidemia rates were similar (70.4% vs. 71.7%), although aberrant lipid profiles such as Lipoprotein-X in sarcoidosis highlight the need for meticulous lipid evaluation. [

18]

Family history was more prevalent in the amyloidosis group (24.8% vs. 5.4%), consistent with epidemiological data on variant transthyretin (ATTR) amyloidosis, particularly the Val122Ile mutation, which is more commonly seen in African American and Caribbean descendants. [

19] In contrast, sarcoidosis presents a more intricate genetic landscape, with ethnic and familial predispositions that are not seemingly straightforward but do contribute to disease vulnerability, particularly in Northern Europeans and African Americans. [

20] Some patients initially labeled with “isolated cardiac sarcoidosis” have indeed been discovered to harbor pathogenic variants of inherited cardiomyopathies, emphasizing the significance of genetic testing in ambiguous cases. [

21]

Interestingly, prior coronary interventions (e.g., stent placement) also differed: 23.2% in amyloidosis versus 5.4% in sarcoidosis, although myocardial infarction (10.4% versus 7.6%) and CABG (6.4% versus 3.3%) were relatively rare in both groups. We believe this difference is primarily influenced by the age disparity between the groups, which is consistent with findings from national databases. The National Readmissions Database, which includes 4,252 CA patients, shows a mean age of 73.3 ± 11.7 years, with approximately 10% having a history of STEMI. The post-STEMI period was associated with high rates of multi-organ complications, regardless of whether patients underwent PCI or CABG, ultimately resulting in similar mortality outcomes among CA-STEMI patients irrespective of intervention. [

22,

23]

4.2. Imaging Discussion

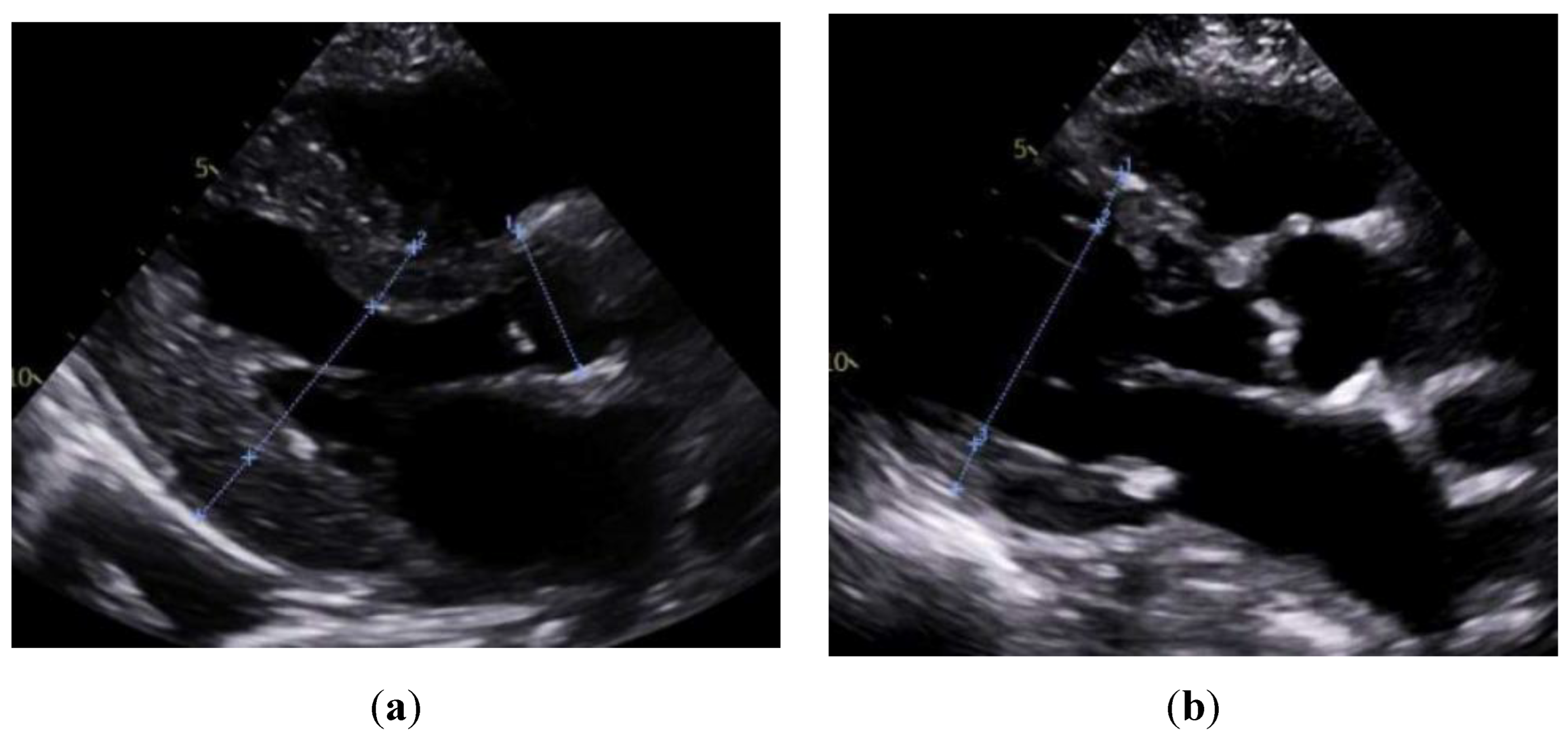

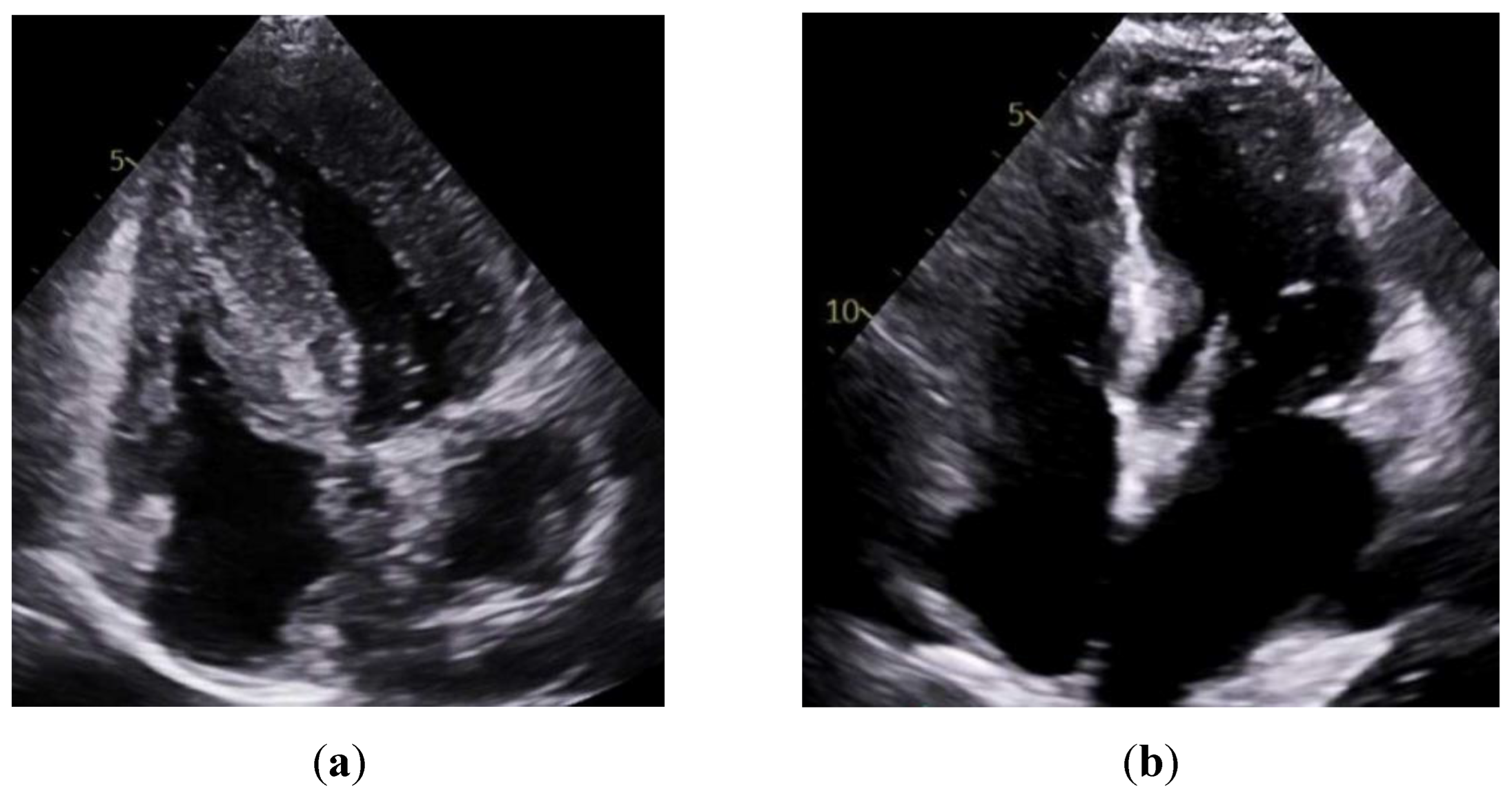

Consistent with prior reports on echocardiographic findings in amyloidosis, namely, pronounced LV wall thickening and diastolic dysfunction. [

24] Our study found significantly greater IVSd and LVPWd in amyloidosis compared to sarcoidosis. (

Figure 1 &

Figure 2) Conversely, TTE offers limited sensitivity in sarcoidosis, functioning mainly to prompt further diagnostic imaging when regional wall thinning or basal septal changes are detected. [

25] Our CMR findings revealed focal or patchy LGE in sarcoidosis, as well as mismatch uptake patterns on PET, which parallels the existing literature that utilizes CMR for structural analysis and FDG PET for monitoring active inflammation. [

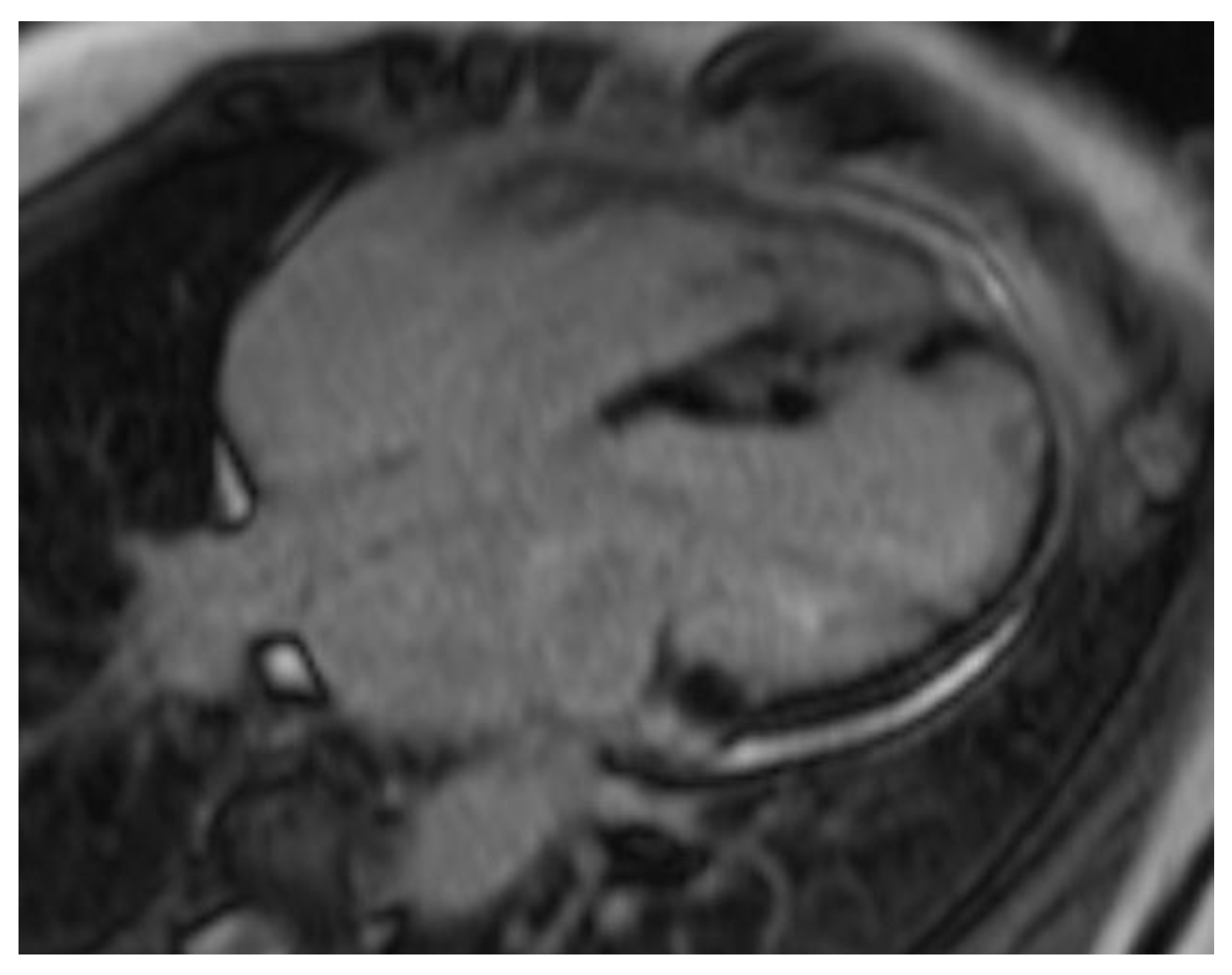

26,

27] Meanwhile, PYP scintigraphy (with a negative monoclonal protein screen) remains highly specific for transthyretin cardiac amyloidosis [

28]. T1 mapping and ECV measurements on CMR can indicate the extent of amyloid infiltration. [

29] However, only 19 of the 125 amyloidosis patients underwent CMR in our study, which limited the robustness of sub-analyses in this domain (

Figure 3).

4.3. Outcome Discussion

Atrial fibrillation (AF) occurred more commonly in amyloidosis (57.6%) than in sarcoidosis (45.7%), aligning with previously reported AF rates approaching 70% in wild-type transthyretin amyloidosis. [

30] Management in amyloidosis often includes anticoagulation, regardless of CHA₂DS₂-VASc scores, and may incorporate rhythm control strategies; however, catheter ablation carries a high risk of recurrence. [

31,

32] In sarcoidosis, AF has been increasingly linked to direct atrial inflammation, especially when FDG PET shows atrial uptake. [

33] Immunosuppression can reduce the inflammatory component, although its effectiveness in purely atrial arrhythmias remains uncertain. [

34] Atrial flutter may also stem from direct sarcoid involvement of the atria, mandating immunosuppressive therapy and potential ablation. [

35]

In contrast, the rates of ventricular tachycardia (VT) (53.3% vs. 10.7%) and ICD placement (66.3% vs. 13.0%) were significantly higher in sarcoidosis than in amyloidosis, consistent with the recognized prevalence of ventricular arrhythmias in infiltrative cardiomyopathies. [

36] While AL amyloidosis carries a significant risk of ventricular arrhythmias, and one population-based study noted a 153-fold increase in ventricular tachycardia, the utility of ICDs is frequently limited by electromechanical dissociation and atrioventricular (AV) block. [

37,

38] Sarcoidosis, though more prone to VT, benefits from timely ICD implantation, likely explaining why higher VT rates do not translate into higher mortality. [

39]

5. Conclusions

Collectively, these findings highlight the critical importance of distinguishing between cardiac amyloidosis and sarcoidosis in clinical practice, given the significant differences in age distributions, imaging signatures, arrhythmia profiles, and mortality rates. Utilizing advanced imaging modalities, such as CMR, PYP, and PET, to identify hallmark disease features, including TTR-specific uptake or inflammatory mismatch patterns, can inform individualized treatment strategies, including disease-modifying agents for ATTR amyloidosis or immunosuppression for sarcoidosis. However, our single-center, cross-sectional analysis relies on limited CMR data and a small sample size. Future research and larger datasets could validate our observed associations, refine arrhythmic risk stratification, explore disease-specific genetic underpinnings, and assess emerging therapeutics, such as vutisiran and acoramidis in amyloidosis, and novel immunomodulators in sarcoidosis.

In conclusion, our study demonstrates key demographic, imaging, and outcome-related distinctions between CA and CS. Greater awareness of these distinctions will ultimately enhance diagnostic precision, inform tailored therapeutic approaches, and potentially improve patient outcomes in both of these challenging cardiac conditions.

Author Contributions

L.K., S.S., A.C. contributed to the writing, elaboration, editing, designed the figures and tables. L.K., S.S., J.C., D.K., V.A.T., A.S., A.N., U.S., K.J., S.Z. were involved in data collection. A.C. was involved in reviewing, editing, and supervising the manuscript. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted by the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Institutional Review Board of Mount Sinai Morningside for studies involving humans (STUDY-22-00967; approval date: 3 May 2024)

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable

Data Availability Statement

All data supporting the findings of this study are available from the corresponding authors upon reasonable request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| CA |

Cardiac Amyloidosis |

| CS |

Cardiac Sarcoidosis |

| AL |

Light-Chain Amyloidosis |

| ATTR |

Transthyretin Amyloidosis |

| LGE |

Late Gadolinium Enhancement |

| ECV |

Extracellular Volume |

| PYP |

Pyrophosphate Scintigraphy |

| FDG-PET |

Fluorodeoxyglucose Positron Emission Tomography |

References

- Martinez-Naharro, A.; Hawkins, P.N.; Fontana, M. Cardiac Amyloidosis. Clinical Medicine 2018, 18, s30–s35. [CrossRef]

- Birnie, D.H.; Nery, P.B.; Ha, A.C.; Beanlands, R.S.B. Cardiac Sarcoidosis. JACC 2016, 68, 411–421. [CrossRef]

- Knight, D.S.; Zumbo, G.; Barcella, W.; Steeden, J.A.; Muthurangu, V.; Martinez, -Naharro Ana; Treibel, T.A.; Abdel, -Gadir Amna; Bulluck, H.; Kotecha, T.; et al. Cardiac Structural and Functional Consequences of Amyloid Deposition by Cardiac Magnetic Resonance and Echocardiography and Their Prognostic Roles. JACC: Cardiovascular Imaging 2019, 12, 823–833. [CrossRef]

- Banba, K.; Kusano, K.F.; Nakamura, K.; Morita, H.; Ogawa, A.; Ohtsuka, F.; Ohta Ogo, K.; Nishii, N.; Watanabe, A.; Nagase, S.; et al. Relationship between Arrhythmogenesis and Disease Activity in Cardiac Sarcoidosis. Heart Rhythm 2007, 4, 1292–1299. [CrossRef]

- Falk, R.H. Cardiac Amyloidosis. Circulation 2011, 124, 1079–1085. [CrossRef]

- Nordenswan, H.-K.; Pöyhönen, P.; Lehtonen, J.; Ekström, K.; Uusitalo, V.; Niemelä, M.; Vihinen, T.; Kaikkonen, K.; Haataja, P.; Kerola, T.; et al. Incidence of Sudden Cardiac Death and Life-Threatening Arrhythmias in Clinically Manifest Cardiac Sarcoidosis With and Without Current Indications for an Implantable Cardioverter Defibrillator. Circulation 2022, 146, 964–975. [CrossRef]

- Ney, S.; Ihle, P.; Ruhnke, T.; Günster, C.; Michels, G.; Seuthe, K.; Hellmich, M.; Pfister, R. Epidemiology of Cardiac Amyloidosis in Germany: A Retrospective Analysis from 2009 to 2018. Clin Res Cardiol 2023, 112, 401–408. [CrossRef]

- Mora, -Ayestaran Nerea; Dispenzieri, A.; Kristen, A.V.; Maurer, M.S.; Diemberger, I.; Drachman, B.M.; Grogan, M.; Gupta, P.; Glass, O.; Amass, L.; et al. Age- and Sex-Related Differences in Patients With Wild-Type Transthyretin Amyloidosis. JACC: Advances 2024, 3, 101086. [CrossRef]

- Kandolin, R.; Lehtonen, J.; Airaksinen, J.; Vihinen, T.; Miettinen, H.; Ylitalo, K.; Kaikkonen, K.; Tuohinen, S.; Haataja, P.; Kerola, T.; et al. Cardiac Sarcoidosis. Circulation 2015, 131, 624–632. [CrossRef]

- Mathai, S.V.; Patel, S.; Jorde, U.P.; Rochlani, Y. Epidemiology, Pathogenesis, and Diagnosis of Cardiac Sarcoidosis. Methodist Debakey Cardiovasc J 18, 78–93. [CrossRef]

- Duvall, C.; Pavlovic, N.; Rosen, N.S.; Wand, A.L.; Griffin, J.M.; Okada, D.R.; Tandri, H.; Kasper, E.K.; Sharp, M.; Chen, E.S.; et al. Sex and Race Differences in Cardiac Sarcoidosis Presentation, Treatment and Outcomes. Journal of Cardiac Failure 2023, 29, 1135–1145. [CrossRef]

- Argirò, A.; Biagioni, G.; Mazzoni, C.; Zampieri, M.; Allinovi, M.; Musumeci, B.; Tini, G.; Cianca, A.; Merlo, M.; Sinagra, G.; et al. Prognostic Impact of Hypertension and Diabetes in Patients with Cardiac Amyloidosis. International Journal of Cardiology 2025, 424, 133027. [CrossRef]

- Beyene, S.S.; Yacob, O.; Melaku, G.D.; Hideo-Kajita, A.; Kuku, K.O.; Brathwaite, E.; Wilson, V.; Dan, K.; Kadakkal, A.; Sheikh, F.; et al. Comparison of Patterns of Coronary Artery Disease in Patients With Heart Failure by Cardiac Amyloidosis Status. Cardiovascular Revascularization Medicine 2021, 27, 31–35. [CrossRef]

- Mahmoud, A.R.; Dahy, A.; Dibas, M.; Abbas, A.S.; Ghozy, S.; El-Qushayri, A.E. Association between Sarcoidosis and Cardiovascular Comorbidity: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Heart & Lung 2020, 49, 512–517. [CrossRef]

- Yafasova, A.; Fosb, øl E.L.; Schou, M.; Gustafsson, F.; Rossing, K.; Bundgaard, H.; Lauridsen, M.D.; Kristensen, S.L.; Torp, -Pedersen Christian; Gislason, G.H.; et al. Long-Term Adverse Cardiac Outcomes in Patients With Sarcoidosis. JACC 2020, 76, 767–777. [CrossRef]

- Arcana, R.I.; Crișan-Dabija, R.; Cernomaz, A.T.; Buculei, I.; Burlacu, A.; Zabară, M.L.; Trofor, A.C. The Risk of Sarcoidosis Misdiagnosis and the Harmful Effect of Corticosteroids When the Disease Picture Is Incomplete. Biomedicines 2023, 11, 175. [CrossRef]

- Xu, C.; Nery, P.B.; Wiefels, C.; Beanlands, R.S.; Spence, S.D.; Juneau, D.; Promislow, S.; Boczar, K.; deKemp, R.A.; Birnie, D.H. Negative Association of Smoking History With Clinically Manifest Cardiac Sarcoidosis: A Case-Control Study. CJC Open 2022, 4, 756–762. [CrossRef]

- Yehya, A.; Huang, R.; Bernard, D.W.; Gotto, A.; Robbins, R.J. Extreme Hypercholesterolemia in Cholestatic Sarcoidosis Due to Lipoprotein X: Exploring the Cholesterol Gap. Journal of Clinical and Translational Endocrinology: Case Reports 2018, 10, 11–13. [CrossRef]

- Arno, S.; Cowger, J. The Genetics of Cardiac Amyloidosis. Heart Fail Rev 2022, 27, 1485–1492. [CrossRef]

- Sivalokanathan, S. Exploring the Role of Genetics in Sarcoidosis and Its Impact on the Development of Cardiac Sarcoidosis. Cardiogenetics 2024, 14, 106–121. [CrossRef]

- Lal, M.; Chen, C.; Newsome, B.; Masha, L.; Camacho, S.A.; Masri, A.; Nazer, B. Genetic Cardiomyopathy Masquerading as Cardiac Sarcoidosis. Journal of the American College of Cardiology 2023, 81, 100–102. [CrossRef]

- Uddin, M.M.; Mir, T.; Kaur, J.; Pervaiz, E.; Babu, M.A.; Sheikh, M. ST-Elevation Myocardial Infarction among Cardiac Amyloidosis Patients; a National Readmission Database Study. Heart Fail Rev 2022, 27, 1579–1586. [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, R.; Najam, N.; Ramphul, K.; Mactaggart, S.; Dulay, M.S.; Okafor, J.; Azzu, A.; Bilal, M.; Memon, R.A.; Sakthivel, H.; et al. Characteristics and Clinical Outcomes of Patients with Sarcoidosis Admitted for ST-Elevation Myocardial Infarction in the United States: A Propensity Matched Analysis from the National Inpatient Sample. Arch Med Sci Atheroscler Dis 2024, 9, e47–e55. [CrossRef]

- Liang, S.; Liu, Z.; Li, Q.; He, W.; Huang, H. Advance of Echocardiography in Cardiac Amyloidosis. Heart Fail Rev 2023, 28, 1345–1356. [CrossRef]

- Okafor, J.; Khattar, R.; Sharma, R.; Kouranos, V. The Role of Echocardiography in the Contemporary Diagnosis and Prognosis of Cardiac Sarcoidosis: A Comprehensive Review. Life 2023, 13, 1653. [CrossRef]

- Torelli, V.A.; Sivalokanathan, S.; Silverman, A.; Zaidi, S.; Saeedullah, U.; Jafri, K.; Choi, J.; Katic, L.; Farhan, S.; Correa, A. Role of Multimodality Imaging in Cardiac Sarcoidosis: A Retrospective Single-Center Experience. Journal of Clinical Medicine 2024, 13, 7335. [CrossRef]

- Aitken, M.; Chan, M.V.; Urzua Fresno, C.; Farrell, A.; Islam, N.; McInnes, M.D.F.; Iwanochko, M.; Balter, M.; Moayedi, Y.; Thavendiranathan, P.; et al. Diagnostic Accuracy of Cardiac MRI versus FDG PET for Cardiac Sarcoidosis: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Radiology 2022, 304, 566–579. [CrossRef]

- Dower, J.; Dima, D.; Lalla, M.; Patel, A.R.; Comenzo, R.L.; Varga, C. The Use of PYP Scan for Evaluation of ATTR Cardiac Amyloidosis at a Tertiary Medical Centre. Br J Cardiol 2022, 29, 19. [CrossRef]

- Syed, I.S.; Glockner, J.F.; Feng, D.; Araoz, P.A.; Martinez, M.W.; Edwards, W.D.; Gertz, M.A.; Dispenzieri, A.; Oh, J.K.; Bellavia, D.; et al. Role of Cardiac Magnetic Resonance Imaging in the Detection of Cardiac Amyloidosis. JACC: Cardiovascular Imaging 2010, 3, 155–164. [CrossRef]

- Mints, Y.Y.; Doros, G.; Berk, J.L.; Connors, L.H.; Ruberg, F.L. Features of Atrial Fibrillation in Wild-Type Transthyretin Cardiac Amyloidosis: A Systematic Review and Clinical Experience. ESC Heart Failure 2018, 5, 772–779. [CrossRef]

- Bukhari, S.; Oliveros, E.; Parekh, H.; Farmakis, D. Epidemiology, Mechanisms, and Management of Atrial Fibrillation in Cardiac Amyloidosis. Current Problems in Cardiology 2023, 48, 101571. [CrossRef]

- Loungani, R.S.; Rehorn, M.R.; Geurink, K.R.; Coniglio, A.C.; Black-Maier, E.; Pokorney, S.D.; Khouri, M.G. Outcomes Following Cardioversion for Patients with Cardiac Amyloidosis and Atrial Fibrillation or Atrial Flutter. American Heart Journal 2020, 222, 26–29. [CrossRef]

- Niemel, ä M.; Uusitalo, V.; P, öyhönen P.; Schildt, J.; Lehtonen, J.; Kupari, M. Incidence and Predictors of Atrial Fibrillation in Cardiac Sarcoidosis. JACC: Cardiovascular Imaging 2022, 15, 1622–1631. [CrossRef]

- Mehta, D.; Willner, J.M.; Akhrass, P.R. Atrial Fibrillation in Cardiac Sarcoidosis. J Atr Fibrillation 2015, 8, 1288.

- Namboodiri, N.; Stiles, M.K.; Young, G.D.; Sanders, P. Electrophysiological Features of Atrial Flutter in Cardiac Sarcoidosis: A Report of Two Cases. Indian Pacing and Electrophysiology Journal 2012, 12, 284–289. [CrossRef]

- Ashraf, I.; Peck, M.M.; Maram, R.; Mohamed, A.; Ochoa Crespo, D.; Kaur, G.; Malik, B.H. Association of Arrhythmias in Cardiac Amyloidosis and Cardiac Sarcoidosis. Cureus 12, e9842. [CrossRef]

- Bukhari, S.; Khan, B. Prevalence of Ventricular Arrhythmias and Role of Implantable Cardioverter-Defibrillator in Cardiac Amyloidosis. Journal of Cardiology 2023, 81, 429–433. [CrossRef]

- Lubitz, S.A.; Goldbarg, S.H.; Mehta, D. Sudden Cardiac Death in Infiltrative Cardiomyopathies: Sarcoidosis, Scleroderma, Amyloidosis, Hemachromatosis. Progress in Cardiovascular Diseases 2008, 51, 58–73. [CrossRef]

- Okada, D.R.; Smith, J.; Derakhshan, A.; Gowani, Z.; Misra, S.; Berger, R.D.; Calkins, H.; Tandri, H.; Chrispin, J. Ventricular Arrhythmias in Cardiac Sarcoidosis. Circulation 2018, 138, 1253–1264. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).