Submitted:

01 March 2025

Posted:

03 March 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Methods

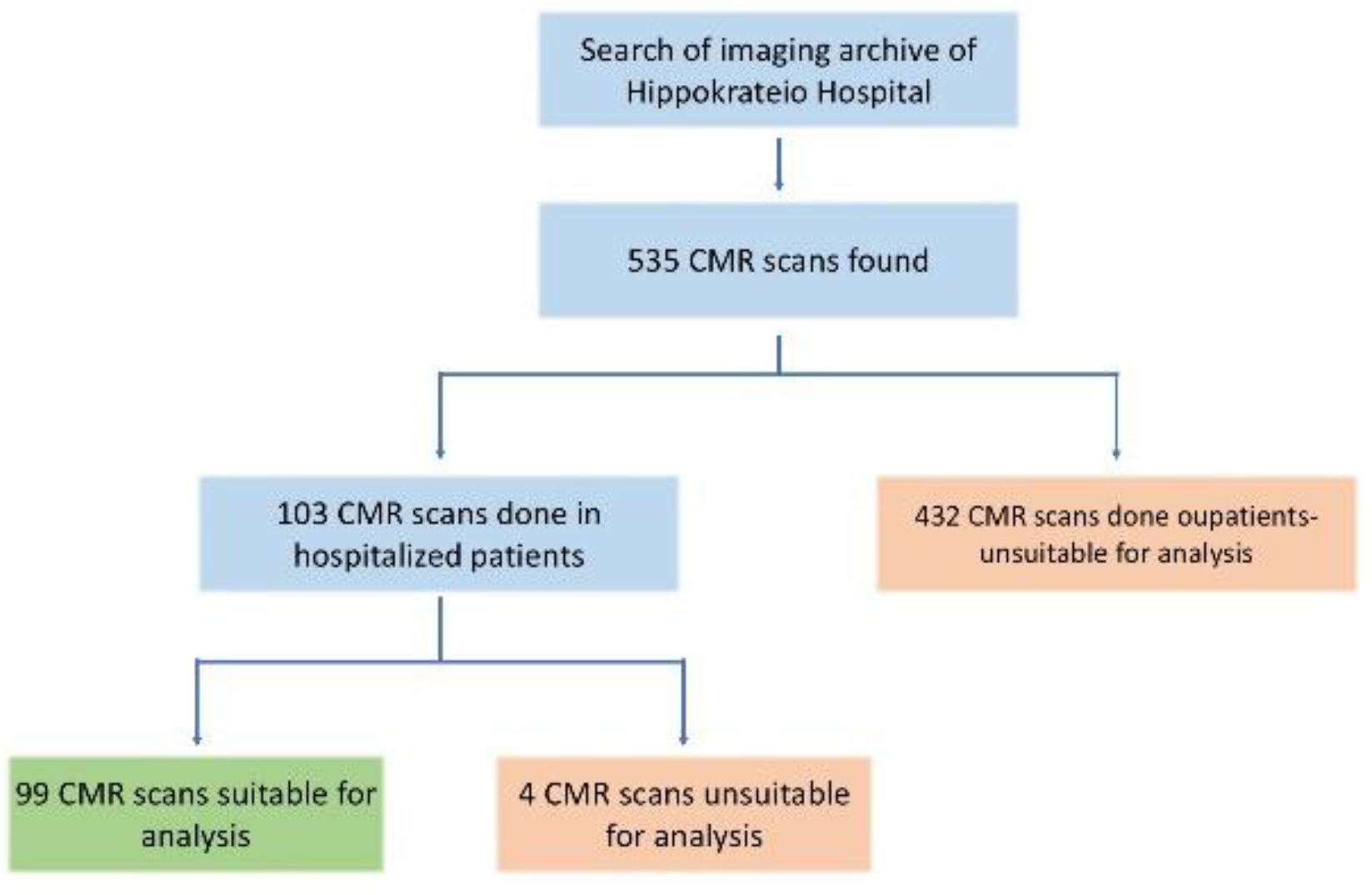

2.1. Study Design

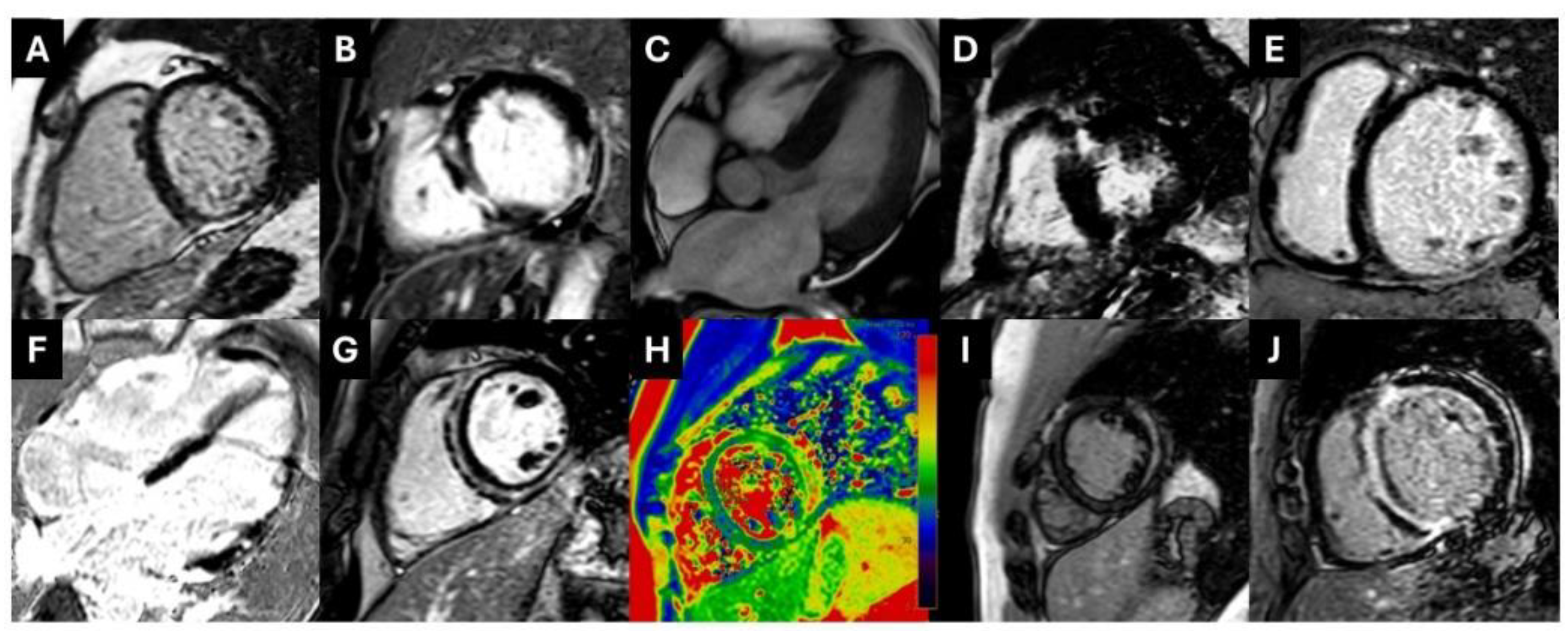

2.2. CMR Imaging

2.3. CVI42 Measurements

2.4. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

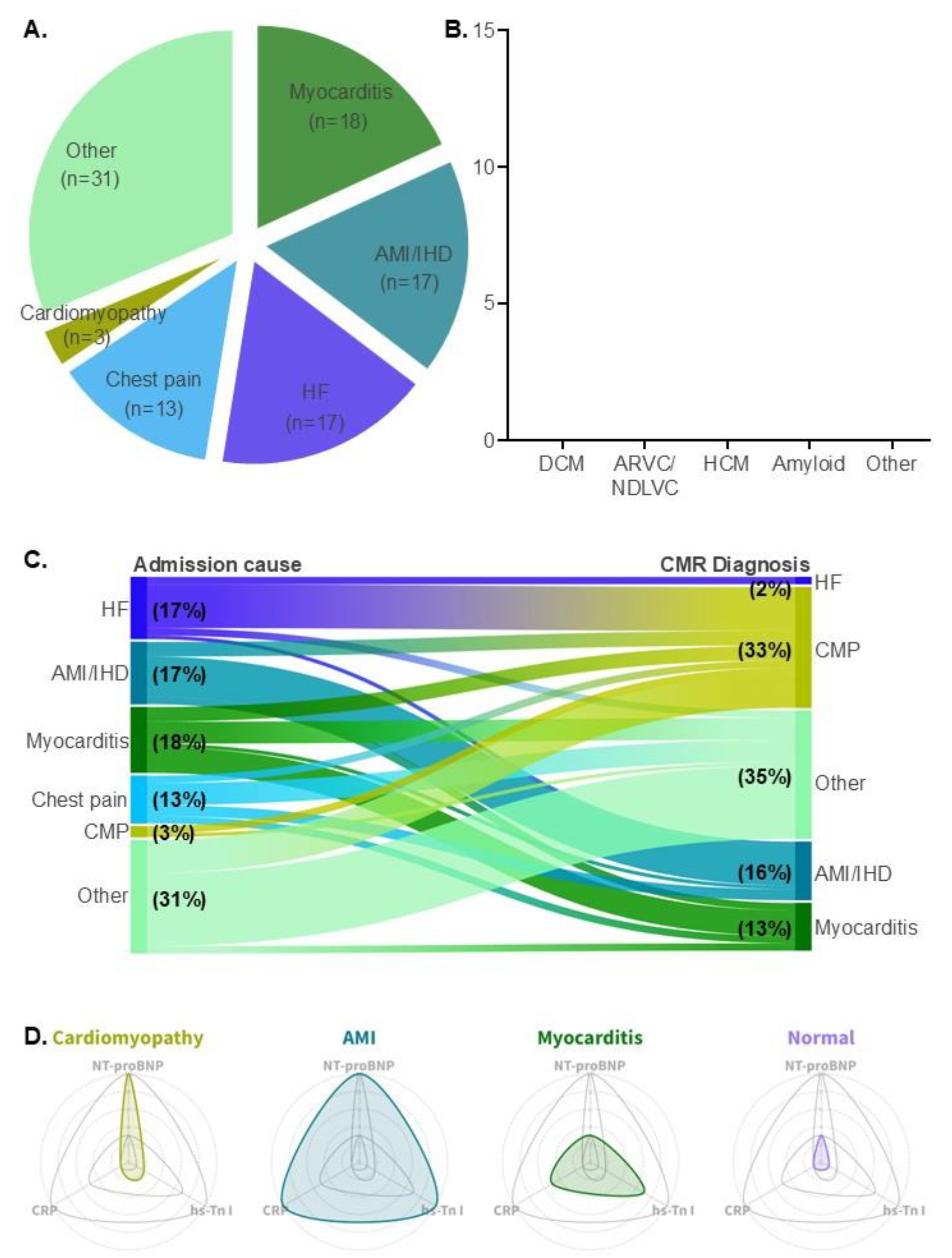

3.1. Patient Demographics and Causes of Hospital Admission

3.2. Clinical Diagnosis by CMR

3.3. Reclassification of Clinical Diagnosis by CMR

3.4. Biomarker Values Among Different Patient Groups

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Abbreviations

References

- McKenna, W.J.; Maron, B.J.; Thiene, G. Classification, Epidemiology, and Global Burden of Cardiomyopathies. Circ Res 2017, 121, 722–730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tsatsopoulou, A.; Protonotarios, I.; Xylouri, Z.; Papagiannis, I.; Anastasakis, A.; Germanakis, I.; Patrianakos, A.; Nyktari, E.; Gavras, C.; Papadopoulos, G.; et al. Cardiomyopathies in children: An overview. Hellenic J Cardiol 2023, 72, 43–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sinagra, G.; Carriere, C.; Clemenza, F.; Minà, C.; Bandera, F.; Zaffalon, D.; Gugliandolo, P.; Merlo, M.; Guazzi, M.; Agostoni, P. Risk stratification in cardiomyopathy. Eur J Prev Cardiol 2020, 27, 52–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zegkos, T.; Tziomalos, G.; Parcharidou, D.; Ntelios, D.; Papanastasiou, C.A.; Karagiannidis, E.; Gossios, T.; Rouskas, P.; Katranas, S.; Paraskevaidis, S.; et al. Validation of the new American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Guidelines for the risk stratification of sudden cardiac death in a large Mediterranean cohort with Hypertrophic Cardiomyopathy. Hellenic J Cardiol 2022, 63, 15–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jefferies, J.L.; Towbin, J.A. Dilated cardiomyopathy. Lancet 2010, 375, 752–762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lukas Laws, J.; Lancaster, M.C.; Ben Shoemaker, M.; Stevenson, W.G.; Hung, R.R.; Wells, Q.; Marshall Brinkley, D.; Hughes, S.; Anderson, K.; Roden, D.; et al. Arrhythmias as Presentation of Genetic Cardiomyopathy. Circ Res 2022, 130, 1698–1722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoffman-Andrews, L.; Chokshi, N.; Owens, A.T.; Munson, T.; Mehr, L.; Chowns, J.; Deo, R. Desmoplakin-related cardiomyopathy presenting with syncope and elevated troponins. Journal of the American College of Cardiology 2024, 83, 2724–2724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antonopoulos, A.S.; Xintarakou, A.; Protonotarios, A.; Lazaros, G.; Miliou, A.; Tsioufis, K.; Vlachopoulos, C. Imagenetics for Precision Medicine in Dilated Cardiomyopathy. Circ Genom Precis Med 2024, 17, e004301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Semsarian, C.; Ingles, J.; Maron, M.S.; Maron, B.J. New Perspectives on the Prevalence of Hypertrophic Cardiomyopathy. Journal of the American College of Cardiology 2015, 65, 1249–1254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Japp, A.G.; Gulati, A.; Cook, S.A.; Cowie, M.R.; Prasad, S.K. The Diagnosis and Evaluation of Dilated Cardiomyopathy. J Am Coll Cardiol 2016, 67, 2996–3010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antonopoulos, A.S.; Almogheer, B.; Azzu, A.; Alati, E.; Papagkikas, P.; Cheong, J.; Clague, J.; Wechalekar, K.; Baksi, J.; Alpendurada, F. Typical and atypical imaging features of cardiac amyloidosis. Hellenic J Cardiol 2021, 62, 312–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mavrogeni, S.I.; Kallifatidis, A.; Kourtidou, S.; Lama, N.; Christidi, A.; Detorakis, E.; Chatzantonis, G.; Vrachliotis, T.; Karamitsos, T.; Kouskouras, K.; et al. Cardiovascular magnetic resonance for the evaluation of patients with cardiovascular disease: An overview of current indications, limitations, and procedures. Hellenic J Cardiol 2023, 70, 53–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Merlo, M.; Gagno, G.; Baritussio, A.; Bauce, B.; Biagini, E.; Canepa, M.; Cipriani, A.; Castelletti, S.; Dellegrottaglie, S.; Guaricci, A.I.; et al. Clinical application of CMR in cardiomyopathies: evolving concepts and techniques : A position paper of myocardial and pericardial diseases and cardiac magnetic resonance working groups of Italian society of cardiology. Heart Fail Rev 2023, 28, 77–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nikolaidou, C.; Bazmpani, M.A.; Tziatzios, I.; Toumpourleka, M.; Karvounis, C.; Karamitsos, T.D. Double-chambered left ventricle characterized by CMR. Hellenic J Cardiol 2017, 58, 459–460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ugander, M.; Bagi, P.S.; Oki, A.J.; Chen, B.; Hsu, L.Y.; Aletras, A.H.; Shah, S.; Greiser, A.; Kellman, P.; Arai, A.E. Myocardial edema as detected by pre-contrast T1 and T2 CMR delineates area at risk associated with acute myocardial infarction. JACC Cardiovasc Imaging 2012, 5, 596–603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rudolph, A.; Abdel-Aty, H.; Bohl, S.; Boyé, P.; Zagrosek, A.; Dietz, R.; Schulz-Menger, J. Noninvasive detection of fibrosis applying contrast-enhanced cardiac magnetic resonance in different forms of left ventricular hypertrophy relation to remodeling. J Am Coll Cardiol 2009, 53, 284–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chrysohoou, C.; Antoniou, C.K.; Stillman, A.; Lalude, O.; Henry, T.; Lerakis, S. Myocardial fibrosis detected with Gadolinium Delayed Enhancement in Cardiac Magnetic Resonance Imaging and Ventriculoarterial Coupling alterations in patients with Acute Myocarditis. Hellenic J Cardiol 2016, 57, 449–454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antonopoulos, A.S.; Tsampras, T.; Lazaros, G.; Tsioufis, K.; Vlachopoulos, C. A phenomap of TTR amyloidosis to aid diagnostic screening. ESC Heart Failure n/a. [CrossRef]

- Antonopoulos, A.; Tsampras, T.; Ioannides, M.; Eftychiou, C.; Panagiotopoulos, I.; Naka, K.; Zacharoulis, A.; Ktenopoulos, N.; Katsimaglis, G.; Vavouranakis, E.; et al. Insights into cardiac amyloidosis screening in TAVI from a Greek/Cypriot Cohort: the GRECA-TAVI registry. European Heart Journal 2024, 45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arbelo, E.; Protonotarios, A.; Gimeno, J.R.; Arbustini, E.; Barriales-Villa, R.; Basso, C.; Bezzina, C.R.; Biagini, E.; Blom, N.A.; de Boer, R.A.; et al. 2023 ESC Guidelines for the management of cardiomyopathies. Eur Heart J 2023, 44, 3503–3626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, K.; Nakou, E.; Del Buono, M.G.; Montone, R.A.; D'Amario, D.; Bucciarelli-Ducci, C. The Role of Cardiac Magnetic Resonance in Myocardial Infarction and Non-obstructive Coronary Arteries. Front Cardiovasc Med 2021, 8, 821067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daneshrad, J.A.; Ordovas, K.; Sierra-Galan, L.M.; Hays, A.G.; Mamas, M.A.; Bucciarelli-Ducci, C.; Parwani, P. Role of Cardiac Magnetic Resonance Imaging in the Evaluation of MINOCA. J Clin Med 2023, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mileva, N.; Paolisso, P.; Gallinoro, E.; Fabbricatore, D.; Munhoz, D.; Bergamaschi, L.; Belmonte, M.; Panayotov, P.; Pizzi, C.; Barbato, E.; et al. Diagnostic and Prognostic Role of Cardiac Magnetic Resonance in MINOCA: Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. JACC: Cardiovascular Imaging 2023, 16, 376–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, C.; Ferrari, V.A.; Han, Y. Cardiovascular Magnetic Resonance Imaging and Heart Failure. Curr Cardiol Rep 2021, 23, 35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Andreini, D.; Dello Russo, A.; Pontone, G.; Mushtaq, S.; Conte, E.; Perchinunno, M.; Guglielmo, M.; Coutinho Santos, A.; Magatelli, M.; Baggiano, A.; et al. CMR for Identifying the Substrate of Ventricular Arrhythmia in Patients With Normal Echocardiography. JACC Cardiovasc Imaging 2020, 13, 410–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schultheiss, H.P.; Fairweather, D.; Caforio, A.L.P.; Escher, F.; Hershberger, R.E.; Lipshultz, S.E.; Liu, P.P.; Matsumori, A.; Mazzanti, A.; McMurray, J.; et al. Dilated cardiomyopathy. Nat Rev Dis Primers 2019, 5, 32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reichart, D.; Magnussen, C.; Zeller, T.; Blankenberg, S. Dilated cardiomyopathy: from epidemiologic to genetic phenotypes: A translational review of current literature. J Intern Med 2019, 286, 362–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huggins, G.S.; Kinnamon, D.D.; Haas, G.J.; Jordan, E.; Hofmeyer, M.; Kransdorf, E.; Ewald, G.A.; Morris, A.A.; Owens, A.; Lowes, B.; et al. Prevalence and Cumulative Risk of Familial Idiopathic Dilated Cardiomyopathy. Jama 2022, 327, 454–463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pilichou, K.; Thiene, G.; Bauce, B.; Rigato, I.; Lazzarini, E.; Migliore, F.; Perazzolo Marra, M.; Rizzo, S.; Zorzi, A.; Daliento, L.; et al. Arrhythmogenic cardiomyopathy. Orphanet J Rare Dis 2016, 11, 33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corrado, D.; Basso, C.; Judge, D.P. Arrhythmogenic Cardiomyopathy. Circulation Research 2017, 121, 784–802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tschöpe, C.; Cooper, L.T.; Torre-Amione, G.; Van Linthout, S. Management of Myocarditis-Related Cardiomyopathy in Adults. Circ Res 2019, 124, 1568–1583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bariani, R.; Cipriani, A.; Rizzo, S.; Celeghin, R.; Bueno Marinas, M.; Giorgi, B.; De Gaspari, M.; Rigato, I.; Leoni, L.; Zorzi, A.; et al. ‘Hot phase’ clinical presentation in arrhythmogenic cardiomyopathy. EP Europace 2020, 23, 907–917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bariani, R.; Rigato, I.; Cipriani, A.; Bueno Marinas, M.; Celeghin, R.; Basso, C.; Corrado, D.; Pilichou, K.; Bauce, B. Myocarditis-like Episodes in Patients with Arrhythmogenic Cardiomyopathy: A Systematic Review on the So-Called Hot-Phase of the Disease. Biomolecules 2022, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Radunski, U.K.; Lund, G.K.; Stehning, C.; Schnackenburg, B.; Bohnen, S.; Adam, G.; Blankenberg, S.; Muellerleile, K. CMR in Patients With Severe Myocarditis: Diagnostic Value of Quantitative Tissue Markers Including Extracellular Volume Imaging. JACC: Cardiovascular Imaging 2014, 7, 667–675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biesbroek, P.S.; Hirsch, A.; Zweerink, A.; van de Ven, P.M.; Beek, A.M.; Groenink, M.; Windhausen, F.; Planken, R.N.; van Rossum, A.C.; Nijveldt, R. Additional diagnostic value of CMR to the European Society of Cardiology (ESC) position statement criteria in a large clinical population of patients with suspected myocarditis. European Heart Journal - Cardiovascular Imaging 2017, 19, 1397–1407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pregenzer-Wenzler, A.; Abraham, J.; Barrell, K.; Kovacsovics, T.; Nativi-Nicolau, J. Utility of Biomarkers in Cardiac Amyloidosis. JACC: Heart Failure 2020, 8, 701–711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Coats, C.J.; Gallagher, M.J.; Foley, M.; O'Mahony, C.; Critoph, C.; Gimeno, J.; Dawnay, A.; McKenna, W.J.; Elliott, P.M. Relation between serum N-terminal pro-brain natriuretic peptide and prognosis in patients with hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. European Heart Journal 2013, 34, 2529–2537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martens, P.; Cooper, L.T.; Tang, W.H.W. Diagnostic Approach for Suspected Acute Myocarditis: Considerations for Standardization and Broadening Clinical Spectrum. Journal of the American Heart Association 2023, 12, e031454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- James, S.K.; Armstrong, P.; Barnathan, E.; Califf, R.; Lindahl, B.; Siegbahn, A.; Simoons, M.L.; Topol, E.J.; Venge, P.; Wallentin, L. Troponin and C-reactive protein have different relations to subsequent mortality and myocardial infarction after acute coronary syndrome: a GUSTO-IV substudy. J Am Coll Cardiol 2003, 41, 916–924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galvani, M.; Ottani, F.; Oltrona, L.; Ardissino, D.; Gensini, G.F.; Maggioni, A.P.; Mannucci, P.M.; Mininni, N.; Prando, M.D.; Tubaro, M.; et al. N-Terminal Pro-Brain Natriuretic Peptide on Admission Has Prognostic Value Across the Whole Spectrum of Acute Coronary Syndromes. Circulation 2004, 110, 128–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roifman, I.; Hammer, M.; Sparkes, J.; Dall'Armellina, E.; Kwong, R.Y.; Wright, G. Utilization and impact of cardiovascular magnetic resonance on patient management in heart failure: insights from the SCMR Registry. Journal of Cardiovascular Magnetic Resonance 2022, 24, 65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pasupathy, S.; Air, T.; Dreyer, R.P.; Tavella, R.; Beltrame, J.F. Systematic review of patients presenting with suspected myocardial infarction and nonobstructive coronary arteries. Circulation 2015, 131, 861–870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Byrne, R.A.; Rossello, X.; Coughlan, J.J.; Barbato, E.; Berry, C.; Chieffo, A.; Claeys, M.J.; Dan, G.A.; Dweck, M.R.; Galbraith, M.; et al. 2023 ESC Guidelines for the management of acute coronary syndromes. Eur Heart J 2023, 44, 3720–3826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hampal, R.; Knott, K.D.; Plastiras, A.; Bunce, N.H. CMR is vital in the management of cardiology inpatients: a tertiary centre experience. Br J Cardiol 2023, 30, 41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bosman, L.P.; Te Riele, A. Arrhythmogenic right ventricular cardiomyopathy: a focused update on diagnosis and risk stratification. Heart 2022, 108, 90–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Demographics | |

| Patients, n | 99 |

| Age, median, years | 47 [31-63] |

| Male sex, n (%) | 64 (64.7) |

| Race | |

| Caucasian, n (%) | 83 (83.8) |

| Asian, n (%) | 16 (16.2) |

| CMR, days from admission | 3 [31,6] |

| CMR parameters | |

| LVEDV, ml | 178.4±8.5 |

| LVESV, ml | 98.4±8.1 |

| LVSV, ml | 80.0±3.0 |

| LVEF, % | 48.5±1.7 |

| LVCO, L/min | 5.6±0.2 |

| LV Myo Mass Diast, g | 116.5±5.3 |

| LV Myo Mass Syst, g | 121.2±5.5 |

| RVEDV, ml | 169.0±7.6 |

| RVESV, ml | 92.2±6.5 |

| RVSV, ml | 76.8±3.0 |

| RVEF, % | 47.4±1.4 |

| RVCO, L/min | 5.4±0.2 |

| LGE, n (%) | 57 (57.6) |

| Hematologic tests | |

| cTnI, pg/ml | 173.0 [35.1-3019.0] |

| NT-proBNP, pg/ml | 628.5 [221.2-3086.0] |

| CRP, mg/l | 19.0 [5.7-60.1] |

| Type of cardiomyopathy | N |

| DCM | 12 (36%) |

| ARVC / ACM (NDLVC) | 9 (27%) |

| HCM | 5 (15%) |

| CA | 2 (6%) |

| Othera cardiac sarcoidosis EGPA endomyocardial fibrosis unclassified cardiomyopathy |

5 (15%) 1 (3%) 1 (3%) 1 ( 3%) 2 (6%) |

| Biomarker | Cardiomyopathy | Myocarditis | AMI/IHD | Normal CMR | p-value |

| cTnI (pg/ml) | 151.7 [63.4-1940.0] |

5763.0** [2524.0-16922.0] |

14157.0** [2762.0-48310.0] |

107.8 [28.4-339.3] |

p<0.0001 |

| NT-proBNP (pg/ml) | 2263.0 [216.2-4143.0] |

458.8 [357.1-604.6]* |

2336.0 [2083.0-9196.0] |

574.0 [123.4-1823.0] |

p=0.10 |

| CRP (mg/l) | 10.9 [5.9-52.7] |

45.8* [25.8-85.8] |

128.4* [21.7-145.9] |

8.6 [2.7-38.1] |

p=0.01 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).