1. Introduction

Cyber-Physical Systems (CPS) are usually networked systems composed of a number of heterogeneous systems characterized by independent system dynamics, coupled through a set of signals that are transmitted to other systems, where information is exchanged between the systems to enable computation of control commands, in order to regulate or track desired outputs in the systems with reference to an overall control objective in the CPS. In cases where large number of interconnecting nodes are involved it is often advantageous to administer exchange of information merely among adjacent neighbours (i.e., distributed control), rather than deploying a central control architecture that communicates with all the individual nodes. This is particularly important in order to ensure security and reliability, since in this case communication signals can be kept covert and contained in a local fashion. The dispersed nature of CPS often requires public tele-communication infrastructures to be employed for information exchange, rather than dedicated (i.e., leased) communication lines (due to cost and operating expenses). This especially poses threat to the CPS in the form of cyberattacks, and may encounter highly unwanted consequences [

1,

2]. Therefore, the security of the CPS has to be considered and addressed properly in the CPS design phase. A CPS with a distributed control philosophy in which the systems take part in a cooperative control network to achieve a common goal is referred to a Multi-Agent System (MAS), and the systems are referred to as the agents. Specifically, power generating stations in the LFC problem are subsystems (or agents) of the power system (i.e., the CPS) where system states are collected from remote locations and tele-metered to the controllers through a communication system, in order to regulate the frequency of the grid, and exact the desirable amount of electric power to be traded between the power areas.

Cyberattacks are broadly categorized in the literature into deception, and time-delay or DoS attacks [

4]. In deception attacks an adversary attempts to maliciously alter the information packets that are transmitted among the agents in order to cause an intended consequence in the CPS, while time-delays and DoS attacks are obstructive means conducted by adversaries to delay or interrupt in the normal flow of information. The authors in [

3,

4] have considered the cooperative output regulation problem for heterogeneous linear multi-agent systems in the presence of communication constraints. Cooperative output regulation is a generalization of the leader-follower consensus problem in MAS. Load sharing in power systems as explained in [

5] can be formulated from a MAS point of view, in which the area power systems are considered as agents, and limited information are exchanged among the agents to achieve a secondary coordinated control in a decentralized fashion. In [

6] the authors have presented a distributed secondary control scheme for power allocation and voltage restoration in islanded DC micro-grids employing MAS consensus control techniques. As far as the LFC problem is concerned, the authors in [

24] have performed a thorough literature review with respect to the inadequacies in the literature with regard to LFC with time-delays and packet dropouts. According to their studies "existing works have incorporated either DoS cyberattacks, or time-delays in the control loops", where time-delay resiliency methods in the literature either aim at major modifications in the existing communication systems and controllers (such as in [

26]), or suggest gain re-adjustments in PLC controllers [

24], or complicated LMI equations that require precise knowledge of system models [

25,

27,

28].

3. Related Works

The conditions for "consensusability" in linear homogenous MASs has been presented in [

7,

8], where output feedback consensus protocols were given and the closed-loop MAS was shown to be achieving asymptotic consensus if the topology had a spanning tree. Output consensus for heterogeneous MAS with Markovian switching network topologies has been discussed in [

9] and can be used as the basis for studying MAS under DoS cyberattacks assuming that DoS attacks can be represented as switching topologies. Unfortunately, [

9] does not address communication time-delays and instability issues that can be caused due to information reception delays. The authors in [

11] have also attempted to solve the output consensus problem in a leader-follower heterogenous MAS under DoS attack. Unfortunately, the solution proposed in [

11] can neither be applicable in real-world, since leader’s dynamic is unknown to the follower agents in most scenarios (especially, in a MAS where the leader is randomly switched from time to time, such as in a MAS of UAVs where the leader may have to be switched randomly from one agent to another for the system to be robust against the leader’s internal faults and outages).

The subject of distributed consensus of heterogenous MAS subject to switching topologies and communication time-delays has been a recent research problem in the literature (as in [

10]) with a focus on power systems. This article provides a comprehensive solution for stability and control of heterogenous MAS systems considering a switching controller that alters the controller gain based on the knowledge that a time-delay attack has taken place. The authors in [

3] have investigated cooperative resilient output regulation problem with time-delay constraints for a specific class of heterogenous MAS with uniform exogenous inputs (following a LTI dynamics with pure imaginary eigenvalues). Unfortunately, the authors have assumed an exogenous signal that has a predetermined dynamics, which violates a fully arbitrary output trajectory condition for the leaders (as we discussed earlier), due to the fact that the followers are assuming a consensus law that is based on some predefined system parameters. The authors in [

4] have recently addressed the same subject for a class of CPS systems with non-uniform but bounded communication delays under denial-of-service (DoS) attacks, where a switching resilient control approach is proposed. However, the proposed controller is only functional for DoS attacks (where agents are assumed to understand "missing" information from neighbour agents) but does not address time-delay attacks.

The authors in [

12] have studied consensus in a homogenous MAS, where the agents are expected to follow a given reference command under intrinsic and communication time-delays and disturbances. The authors in [

13] have considered consensus problem for discrete-time homogenous multi-agent systems over an undirected, fixed network communication graph, focusing on the robustness of consensus with respect to communication delay. The authors in [

15,

16] have discussed the problem of output synchronization in a multi-agent system subject to time-delays, with linear right-invertible agents that is subject to arbitrary time-delays. The authors in [

17] have addressed adaptive consensus tracking for a class of nonlinear multi-agent systems under time varying actuator faults. Several other recent publications have also paid attention to time-delayed nonlinear MAS output regulation using data-driven consensus [

18]. The authors in [

19] have discussed consensus problem in a discrete-time nonlinear MAS using sliding mode control laws. The authors in [

20] have investigated the consensus problem of MAS with time-varying delays subject to switching topologies with less conservative consensus conditions. The authors in [

21] have very recently investigated the group consensus problem for heterogeneous MAS with time-delays via pinning control in the frequency domain. For the LFC problem subject to time-delays which nowadays continues as an ongoing and challenging problem in the literature, the authors in [

23] have addressed cybersecurity using linear feedback control employing a set of LMIs. The authors in [

24] have used a filtered PID controller that is tuned in the LFC using the particle swarm optimization (PSO) algorithm to solve the problem. More recent research works on the same topic include [

26]-[

28] to name a few.

4. Definitions and Assumptions

Let us consider an interconnected CPS , and its N constituent subsystems , hereinafter referred to as "subsystems". Generally, subsystems in a CPS may (or may) not involve states that are shared with other subsystems.

Definition 1. We define an "exogenous state" as a shared state between dynamically coupled subsystems whose value is transmitted from one subsystem to another subsystem through a tele-communication channel. On the other hand "endogenous states" are defined as subsystem states when the coupling between the subsystems are removed. Therefore, one may assume that exogenous states are prone to cyberattacks, and endogenous states are immune against cyberattacks.

Definition 2. Let denote the state of , and denote the value of after transmission to , and denote the exogenous state vector of that is transmitted from to . In a delayed communication system and , where is a random time-delay of the communication link from . Therefore, represents the full state vector of which is the sum of the endogenous (i.e., ) and exogenous states .

When the subsystems in a CPS are dynamically coupled, in order to model subsystem dynamics the state of other subsystems involve. One can imagine a very heavy load that is chained and transported by multiple helicopters, or a power system that involves interconnected power areas, which are examples of physically and dynamically coupled subsystems. Autonomous air traffic control in urban air mobility is another example where the coupling between subsystems are non-physical.

Remark 1. It is generally problematic to model a dynamically coupled CPS in which randomly time-delayed exogenous states are involved, and where the dynamic model of the subsystems are unavailable to other subsystems.

In this article we consider a multi-agent system framework in order to facilitate time-delay recovery in the CPS. Therefore, we consider an undirected graph

where

is the set of nodes representing

N number of subsystems (or agents),

as the set of edges (or communication links between the subsystems), and

, representing the adjacency matrix. The elements of

are defined such that

, if

, and

, if

. Let

denote the neighbour set of agent

i (where,

). The Laplacian matrix

, associated to

is defined such that,

where

is the diagonal in-degree matrix. Generally, a heterogeneous linear subsystem

with a time-delay tele-communication system can be defined by the equations,

where

denotes the exogenous states of

according to Definition 2. Furthermore,

denotes the endogenous state vector of

,

denotes the local control command vector, and

denotes a vector of bounded unknown disturbances, and finally

denotes the output vector of

, where matrices

,

and

have appropriate dimensions. System matrices are such that when there is no time-delay present in the tele-communication system Equation (

2) could be represented as,

as later exemplified in Remark 5 (in

Section 8).

Definition 3. Time-delay resiliency in a CPS is defined as a condition where , and for all , where is an arbitrarily small number, where from Definition 2 we had .

Assumption A1. We assume that the network is a connected network with N agents, where all subsystems are stable when there in no time-delay in the tele-communication channels. In other words, the endogenous states are continuous Lipchitz functions of time, and there exists a small , such that , for an arbitrarily small .

Assumption A2. Let us assume that constitute a controllable pair, and constitute an observable pair, for all .

Assumption A3. We assume that a Denial of Service (DoS) attack on agent i from j is equivalent to the condition in a finite duration in time. This is due to the fact that is equivalent to the edge being removed from , implying no communication service from j to i, hence DoS on i from j.

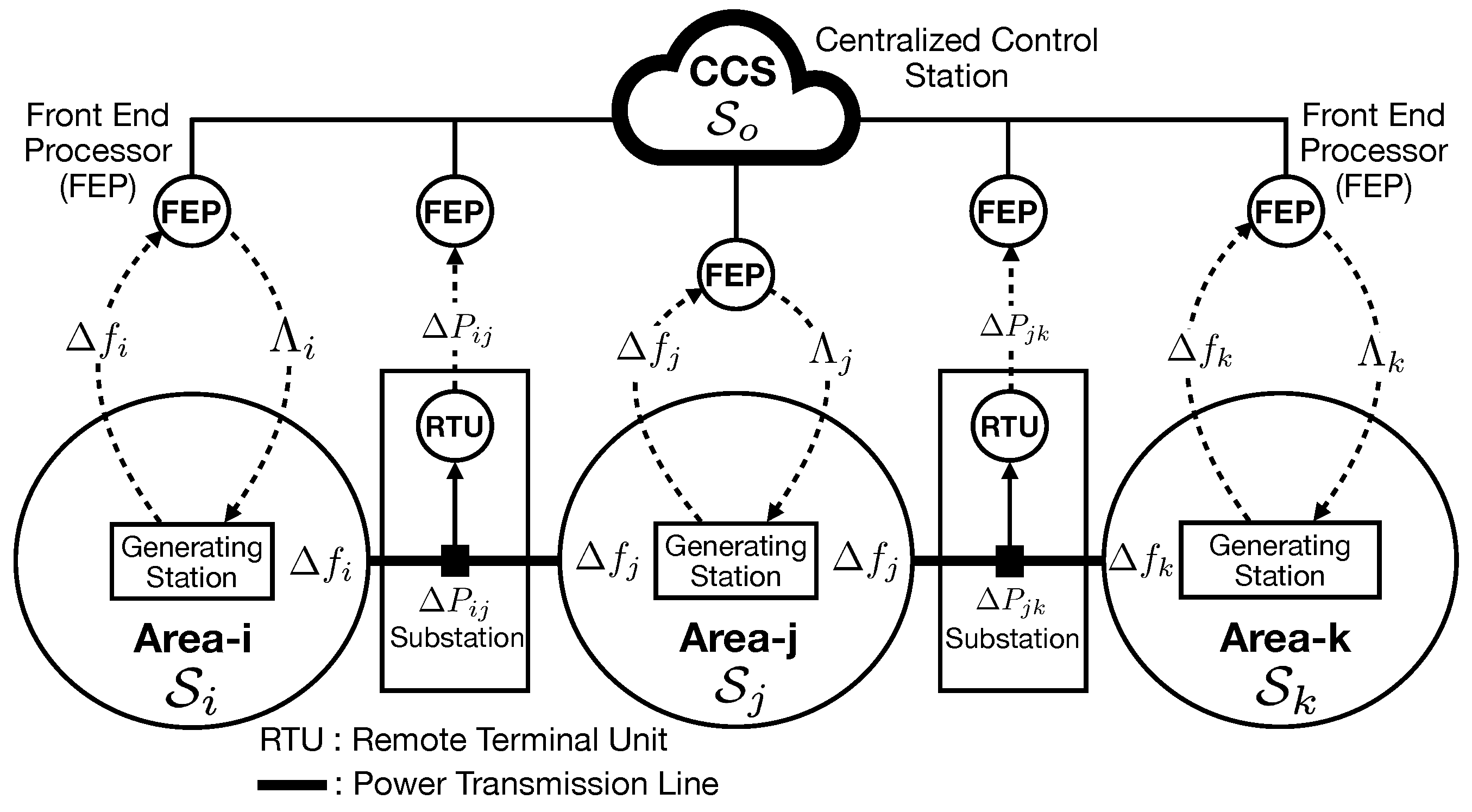

5. The Load Frequency Control (LFC) Example

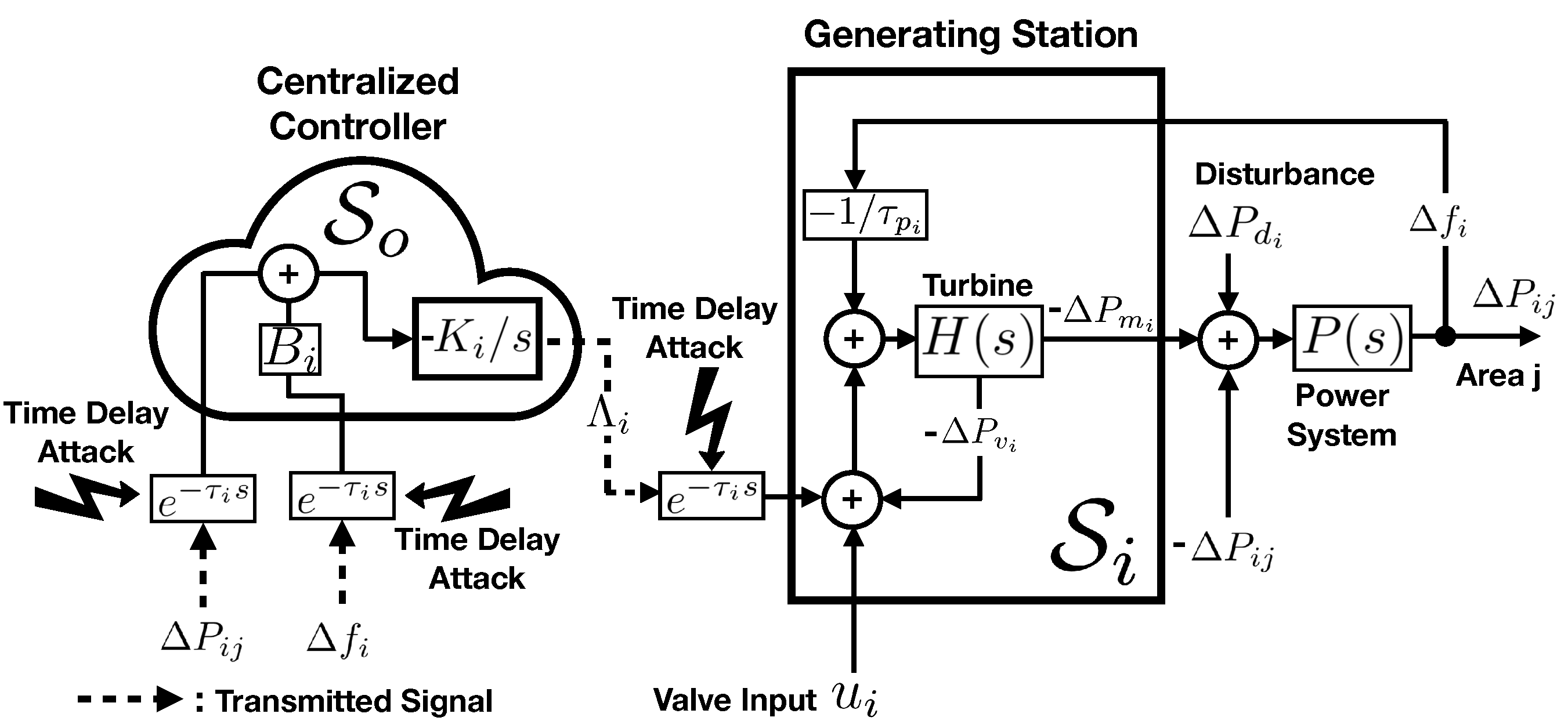

The LFC example clarifies the definitions raised in the previous section, and explains the complexities behind modelling of a CPS. The literature [

5] models the states of a generating station

as

denoting the fluctuations and variations in the area frequency, the mechanical power of the prime mover, the governor valve position, the integrated Area Control Error (ACE) of the equivalent generating units, where ACE

, and the interconnecting tie-line power, respectively, as in

Figure 1, where,

where

are positive constants, and where

is a control variable calculated by the Central Control Station (CCS) and transmitted to

as shown in

Figure 1.

in the figure denotes variations in the power of the area transmission lines and intermittent renewable energies, and is considered as a random variable. The objective of the LFC as the name implies is to control the area frequency with respect to changes in

, while maintaining the preset amount of energy exchange between the areas (i.e.,

). In other words, the objective of the LFC is that,

This is due to the fact that

is often a time-varying contracted variable between two areas and is set by the main input

in

Figure 1, where one area commits to supply a regulated amount of energy to the other area, irrespective of the variations in area load.

and

are exogenous states for

, and the first three entries of

are endogenous states for

.

A time-delay cyberattack on the tele-communication channels of

causes the actual

to be observed by the controller in

as

, where

is an unknown random time-delay. Similarly, let

denote the desirable power to be traded between

and its adjacent power area

. The sensor collecting the instantaneous power

is often remote from the controller in

. Therefore, the practice is to install Remote Terminal Units (RTUs) inside the power substations (controlling circuit breakers, disconnector switches, and other electric apparatus associated with transmission lines) to continuously read

and transmit the value to the CCS through a tele-communication line for the computation of

. However, the tele-communication time-delays result in

, and

being observed in the CCS. Therefore, time-delays

affect the computed value

, and

is further delayed by

to finally affect

. In the LFC example of

Figure 2,

’s are the only exogenous states that are actually required by the generating areas for the operation. However, the CCS requires the tie-line power values (i.e.,

’s) and the area frequencies

’s to compute the

’s.

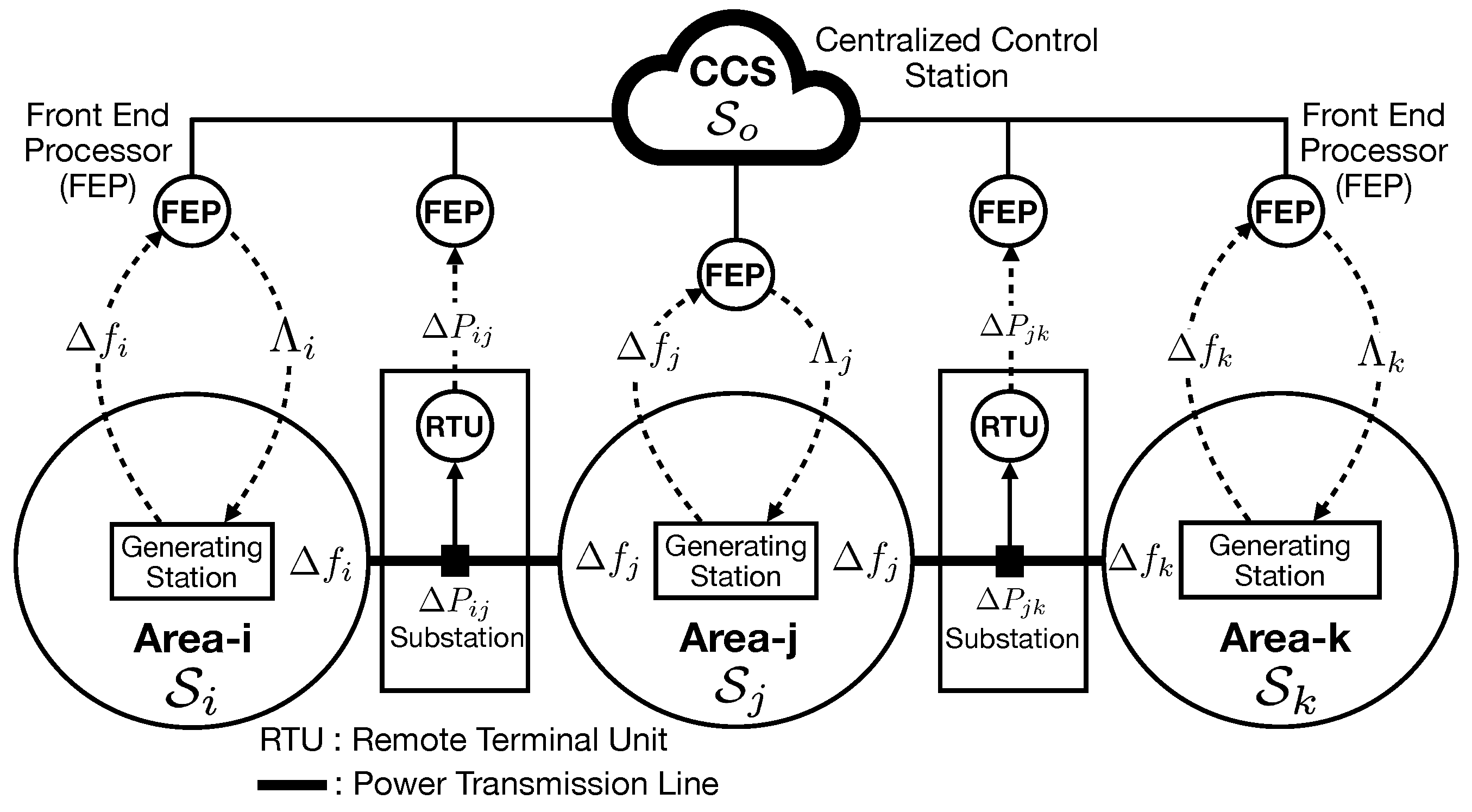

Figure 2 depicts the interconnection of the area generating stations in an LFC through power transmission lines and the flow of information, as an example of a CPS.

6. Problem Statement

Before we formally state the problem let us note from the definitions and the assumptions that

, resulting

, where

is a vector of ones. Through substitution in Equation (

2) it follows that,

where

, and due to the controllability condition in Assumption A2 one would be able to design a feedback control law such as

using

methods, so that

, and for an arbitrarily small

, ensuring stability of the CPS in a Lyapunov sense. This would be always possible since

could be considered as a small disturbance similar to

and rejected through an appropriate state feedback. Therefore,

Remark 2. A time-delay resilient CPS as in Definition 3 guarantees stability of the CPS under all random time-delays , including the objective in Equation (5).

Let denote a connected graph of a CPS with random communication delays between the constituent subsystems . Let be an endogenous state of to be transmitted to all other subsystems , and let denote the delayed value of at , respectively, where .

The problem is to recover the real-time value of

at all recipient subsystems

, with an arbitrarily negligible time-delay

, by cooperative-filtering of the delayed signals. In particular, the objective is to find an LTI filter with impulse response

so that,

for all

, where

’s are real constant coefficients,

is an arbitrarily small transient time for the filter

, and where

is the input of the filter, and

are auxiliary inputs from the neighbouring subsystems of

.

Definition 4. A CPS that incorporates the exchange of information among constituent subsystems in order to achieve a common goal (i.e., time-delay resiliency) in a distributed system framework is referred to as a Multi Agent System (MAS), and the processing component (e.g., the filter) in each subsystem that involves the exchange of information is referred to as an "agent". Therefore, the cooperative filter proposed in Equation (6) is a MAS.

7. Main Results

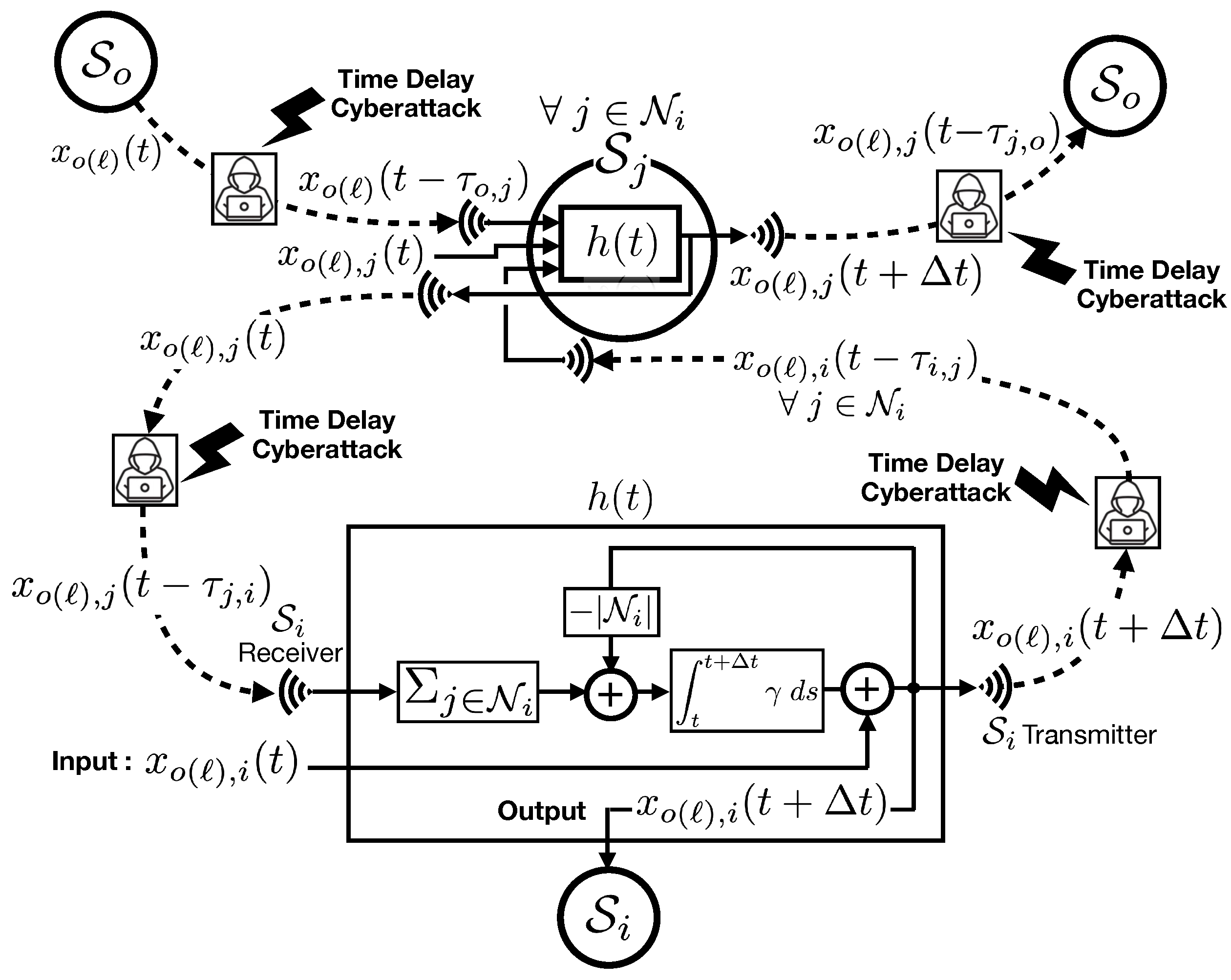

The multi-agent filtering structure in

Figure 3 guarantees time-delay resiliency in the CPS despite of the random time-delay cyberattacks on the communication channels, and the objective is to attain the real-time value of a state

in agent

.

The filters

are identical in all agents and are located immediately after the data receivers. The internal block diagram of the filter

is as shown in the box for

where the input

can be

if there is a direct communication link between

, or any arbitrary conjecture available to

. The output of the filter is

where

is a controllable transient time for the filter that can be arbitrarily adjusted through the filter gain

, and is fed to the internal controller in

and simultaneously shared with the neighbouring agents. The interesting and important characteristic of the multi-agent filtering scheme is that the outputs of all filters will become identical after lapse of the filter transients and within a negligible settling time

. In particular, for any arbitrary set of inputs

one will have,

regardless of the time delays in the tele-communication channels. Consequently, if any single agent such as

temporarily maintains its output at

, then it follows that,

which satisfies the objective in Equation (

6). This implies that any single agent in the MAS such as

where its output follows its input for a time period

will act as the leader in the MAS and all other agents in

will follow and track the output

. More specifically,

Remark 3. The connected MAS shown in Figure 3 will achieve consensus as in Equation (7) regardless of the time-delays in the tele-communication links, and the consensus value will be equal to the output of the leader only if there is a single leader such as available in the MAS, and where the leader is characterized by the equation .

Remark 4. Clearly, realization of time-delay resiliency through the cooperative filters does not involve dynamic models of the subsystems (as it is evident from Figure 3). Furthermore, can be arbitrarily reduced to improve the error ϵ in Definition 3 by increasing the filter gain γ (refer to [30] Theorem-2). Finally, cooperative filters are components that can be added to existing communication systems without necessary modifications to the existing subsystems.These characteristics are unique advantages that would make the presented technique an ideal solution for CPS time-delay security.

However, in case there are multiple leaders in the MAS the consensus output will be the centroid of the leaders outputs. In what follows the statement in Remark 3 will be justified mathematically, which constitutes firstly, proof of the stability of the MAS filter scheme in the presence of time-delays, and secondly, the output consensus of the MAS under all random time-delays. The following equations can be derived from the schematics of

in

Figure 3.

or,

which follows that,

In order to simplify the notations let

and

. With this simplification, the input/output equation of the MAS in

Figure 3 reduces in a compact form to,

where

is the diagonal in-degree matrix as defined earlier,

, and

is the adjacency matrix of the nodes with time delay

, where

. Note that in case of no time delay, the input-output relation of

Figure 3 could be simply represented as

, where the laplacian matrix would be

.

Lemma 1. For a connected MAS with no time-delays, the cooperative filter in Figure 3 with a sufficiently large gain ensures that , as , if is not filtered, while all other agents use to filter their inputs as depicted in the figure.

The proof is straightforward and can be found in standard MAS textbooks. The implication of Lemma 1 is that the schematics in

Figure 3 guarantees that the agents filter outputs simultaneously converges to

if all the agents except

use

to filter their inputs, and if the output of

is simply connected to the input of

, when there is no time-delay in the system. Theorem 1 and Theorem 3 below will prove that this would be the case even if there is a time-delay in the communication channels, and this would prove time-delay resiliency of the MAS in

Figure 3. The condition

would be equivalent to

for an arbitrarily small

and a sufficiently large

.

Theorem 1. Given the connected MAS in Figure 3, the time-delayed system in Equation (9) is marginally stable (i.e., remains bounded, for all , as ) for all finite time-delays, and all .

Proof. Assume the Lyapunov candidate function,

In order to prove the theorem it would be sufficient to show that

, since in this case

, or

, or

, implying boundedness of

. However, from Equation (

10) it follows that,

which can be written in a compact form as,

where,

, excluding

, and

, excluding

, and

, excluding

, where

is a diagonal matrix with all entries being zeros except

. Therefore, one can write,

where it is denoted that,

and the sufficient condition for marginal stability is to have

. We use the Gershgorin disk theorem to evaluate the eigenvalues of

, which states that "if

is an

real matrix, then all the eigenvalues of

M are located in the union of the following sets",

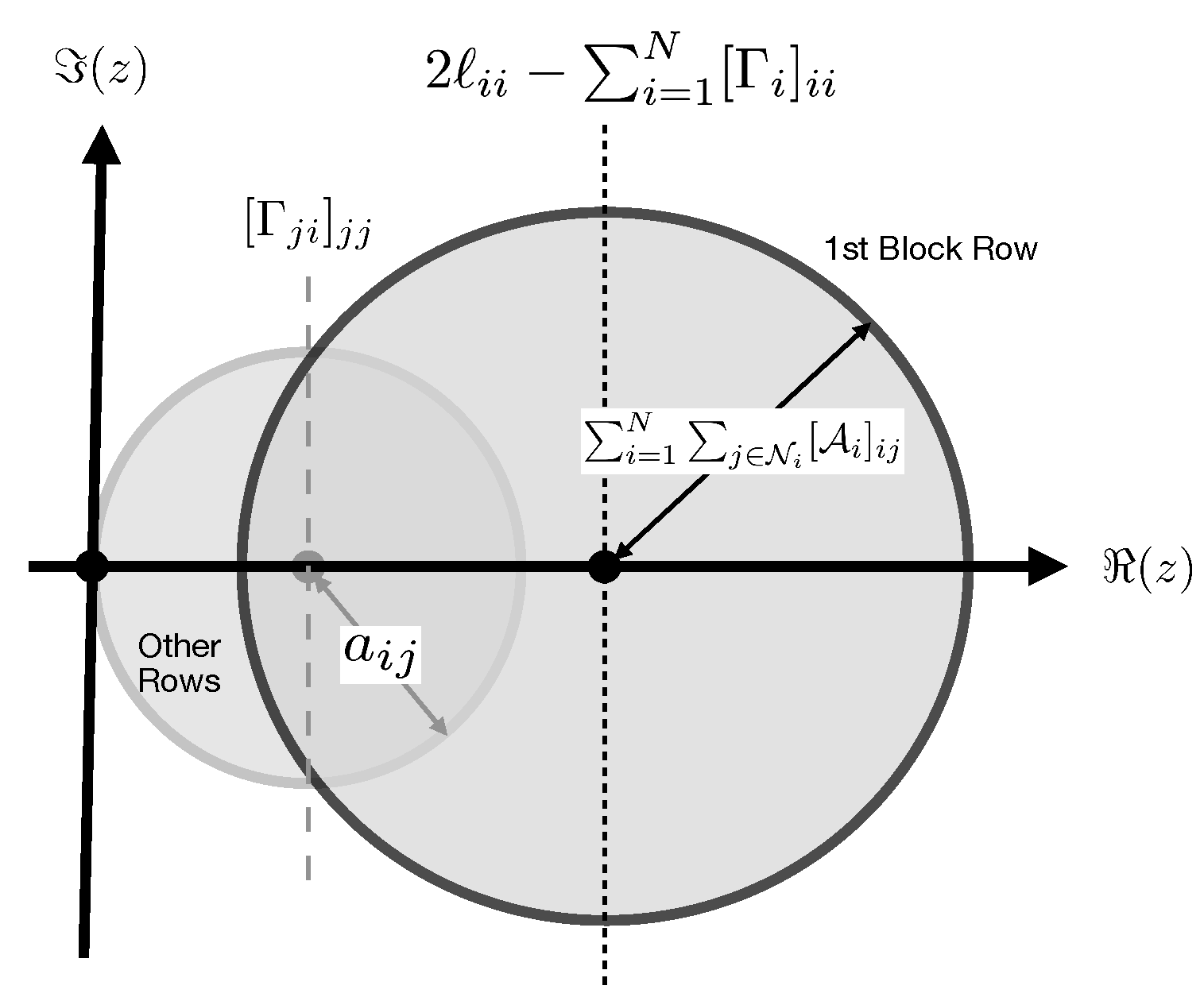

Figure 4 is an illustration of the spectrum of

according to the Gershgorin disk theorem, where each disk corresponds to one row in

, and encloses an eigenvalue of

. Therefore, the eigenvalues of

are encapsulated by the union of the disks illustrated in

Figure 4.

Consequently, the condition

is equivalent to satisfying the following conditions simultaneously,

or,

where the second condition always hold since

. On the other hand

, where

, validating the first condition for all

i. In conclusion, for all finite

one may assume

, which completes the proof of the theorem. □

Figure 4.

Spectrum of with reference to the Gershgorin disk theorem, is the union of several disks where each disk corresponds to a row in . The bigger circle represents the first N rows, referred to as the first block row, where the center of the disk is on the real axis and at to the right, with a radius . The smaller disk represents the set of other block rows where each row is represented by a disk with its center on the real axis at and a radius , and a set of null disks located at the origin.

Figure 4.

Spectrum of with reference to the Gershgorin disk theorem, is the union of several disks where each disk corresponds to a row in . The bigger circle represents the first N rows, referred to as the first block row, where the center of the disk is on the real axis and at to the right, with a radius . The smaller disk represents the set of other block rows where each row is represented by a disk with its center on the real axis at and a radius , and a set of null disks located at the origin.

Theorem 2. The connected MAS with finite time-delays in Theorem 1 achieves consensus. In other words, there exists some , such that , as , where is a column vector with all unit entries.

Proof. One can prove consensus if at (i.e., the equilibrium), and if equilibrium point is at . Therefore, consensusability would be equivalent to the condition, where firstly, the sum of all the entries in every row of is zero, and secondly, if .

In Theorem 1, it was specified that , and , (with every other entry being zero), and (with every other entry being zero). This implies that and , or , and . On the other hand, since , and , it follows that, , and finally, and , which proves that is an equilibrium for V. On the other hand, since is the only solution for , it follows that is the only equilibrium, which completes the proof of the theorem. □

Theorem 3. A time-delayed connected MAS with the cooperative filter scheme in Figure 3 is time-delay resilient with respect to against all bounded time-delay attacks, if is the output of . In other words .

We omit the proof of this lemma due to space constraints. However, one can have a non-rigorous proof to this theorem from the implication of Theorem 2, which states that the output of all the agents in

Figure 3 at

is necessarily equal regardless of their inputs at time

t, and since the output of

is

for all

t including

, it follows that the output of all the filters at

is

, which proves the theorem.

As discussed in the Assumptions, a DoS cyberattack from agent i to j can be represented by the assumption . Therefore, a DoS cyberattack on a random set of edges (where represents the attack on some edges) in the time duration would result a random subgraph and a new Laplacian matrix where, .

Theorem 4. The cooperative filter scheme in Figure 3 achieves asymptotic consensus under arbitrarily random DoS cyberattacks, if there is no infinite DoS attack that disconnects the graph.

Proof. Let us denote that

, and

. Let us also denote the Laplacian matrix of the MAS comprising the leader

and the followers

as

. We have seen from Theorem 1 that for a non switching topology

and therefore

are asymptotically stable for all

. However, in case of random DoS attacks (refer to [

14]) we assume that there are

possible topologies that an adversary may inflict in the network as a result of DoS attack on one or more communication channels, including disconnections in the grid among the followers as well as the leader. Let us consider

Laplacian matrices corresponding to each scenario, denoted by

where

(where

implies disconnections in the network). Corresponding to each scenario

let us consider a symmetric positive definite matrix

with the same dimension (i.e.,

), and let us additionally consider a Lyapunov function

.

We will further assume that a random switching scenario

takes place for

where

is finite for all

. In order to prove Theorem 4 it would be sufficient to prove that for an arbitrary

and an arbitrary topology (denoted by

and

), one could find a

up to the next switching scenario

(with topology

) such that

. For this, one could simply derive

and

as,

and,

Substituting

in Equation (

13), one could obtain,

However, if

or equivalently,

then

, or simply

, for all

, implying that

, which further implies that

, as

, or

, as

.

This could always be possible even if or , which proves that there always exists positive symmetric matrices for all such that the Lyapunov function uniformly decays for all scenarios , under the condition that a disconnection does not last infinitely, which completes the proof of the theorem. □

8. Simulations and Case Studies

The results derived in

Section 7 can be validated by examining the LFC problem discussed in

Figure 2, when the CPS is under time-delay attacks and multiple tele-metered variables such as

are simultaneously attacked by different random time-delays, and when

is a random non-predictable bounded disturbance in the area load. To the best of the knowledge of this authors the above problem is yet a state-of-the-art open problem constituting an open challenge in the literature. The objective is to guarantee that

for all bounded load variations

, regardless of the time-delay cyberattacks. The time-delayed LFC equation for area

can be represented by,

where

is the state vector of the endogenous states in

,

is the vector of the exogenous states in

from

(i.e., the central control station CCS) as in

Figure 1, and where,

and where

is a disturbance in the LFC representing the variations in the area load, and the renewable energies that contribute to the area power generation.

Remark 5. Clearly, in a real-time LFC without time-delays is the state vector for as explained in outset of Section 5, and is the state matrix of the LTI system.

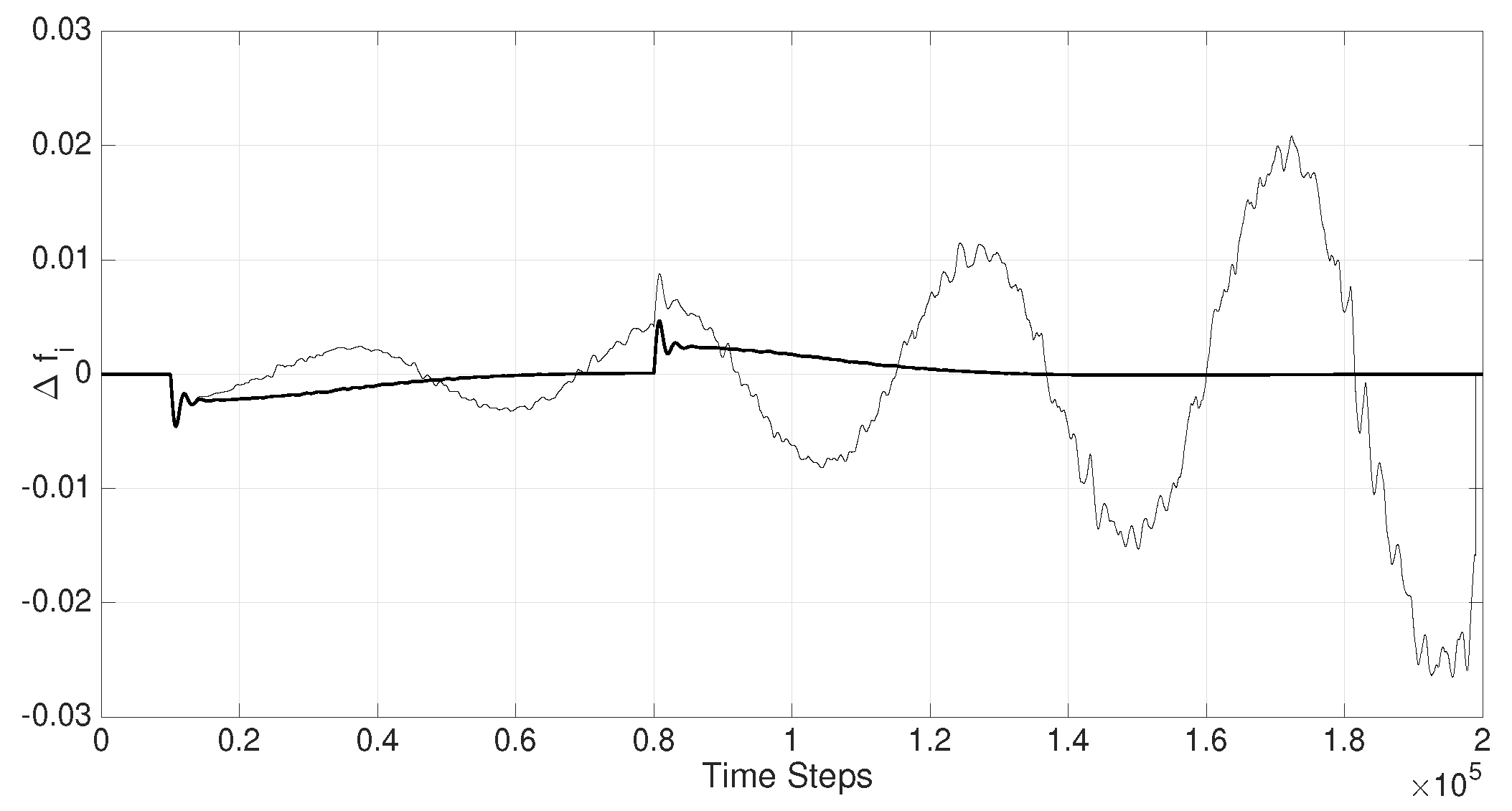

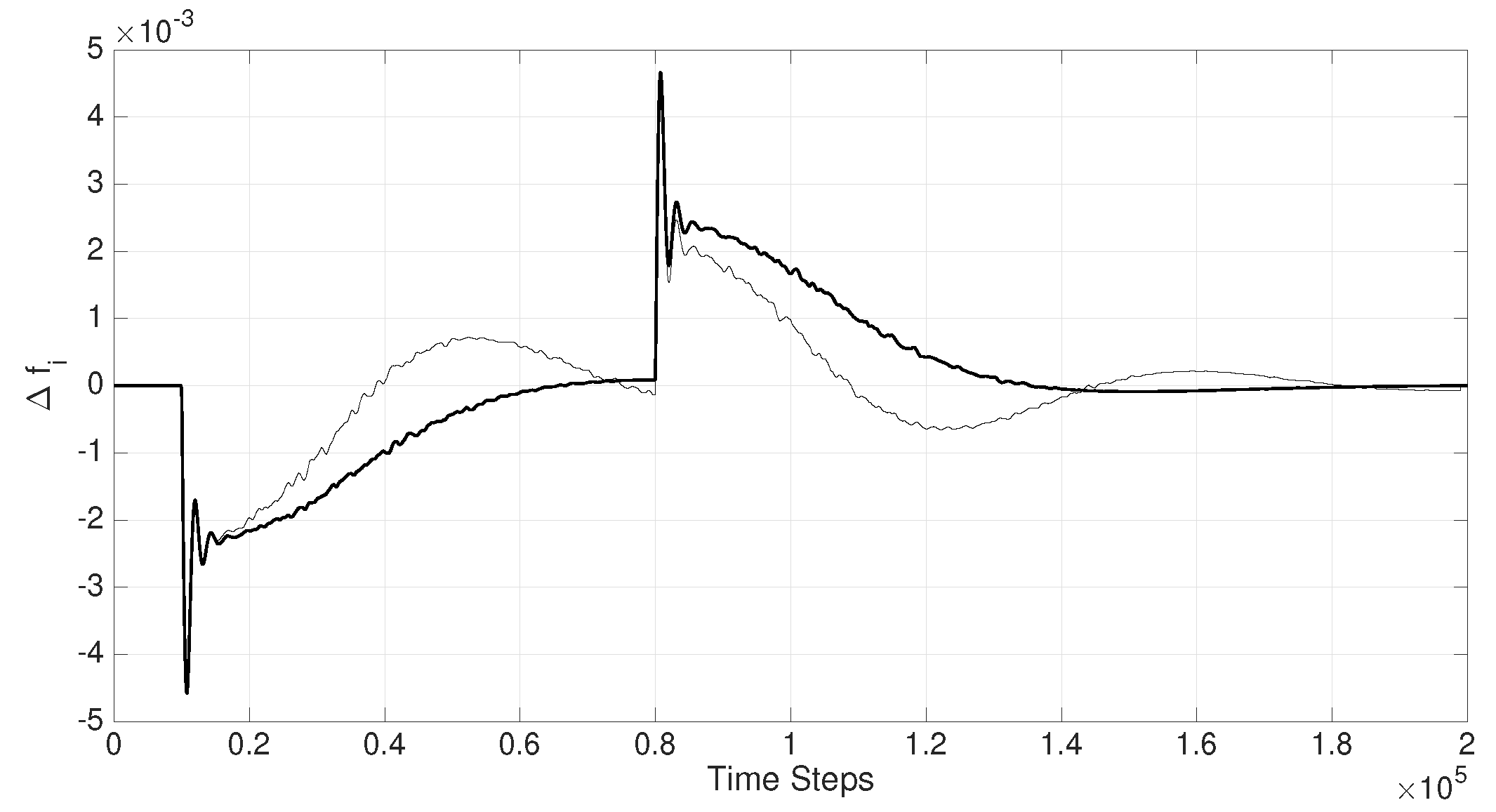

In the simulation results below, a relatively significant and sudden load change in

(

of the nominal area load at time

and

, as per the dashed line

Figure 6) that triggers swings in the power system which has to be contained automatically. Time-delay attacks (if present) are capable of inducing severe instability in the power system if not appropriately circumvented as shown by the thinner line in

Figure 5, which depicts the variations in the area frequency

when resilient filters are not present.

The solid curve in

Figure 5 illustrates the simulation results in the presence of cooperative filters (outlined in

Figure 3), where all tele-metered signals were conditioned by

before they were applied to the agents

. Corresponding to each exogenous state variable (i.e.,

, and

) a cooperative filter is deployed to recover time-delays in the signals. As a result, the instability in the power system can be maintained and the swings in the frequency in result to load variations are rapidly contained.

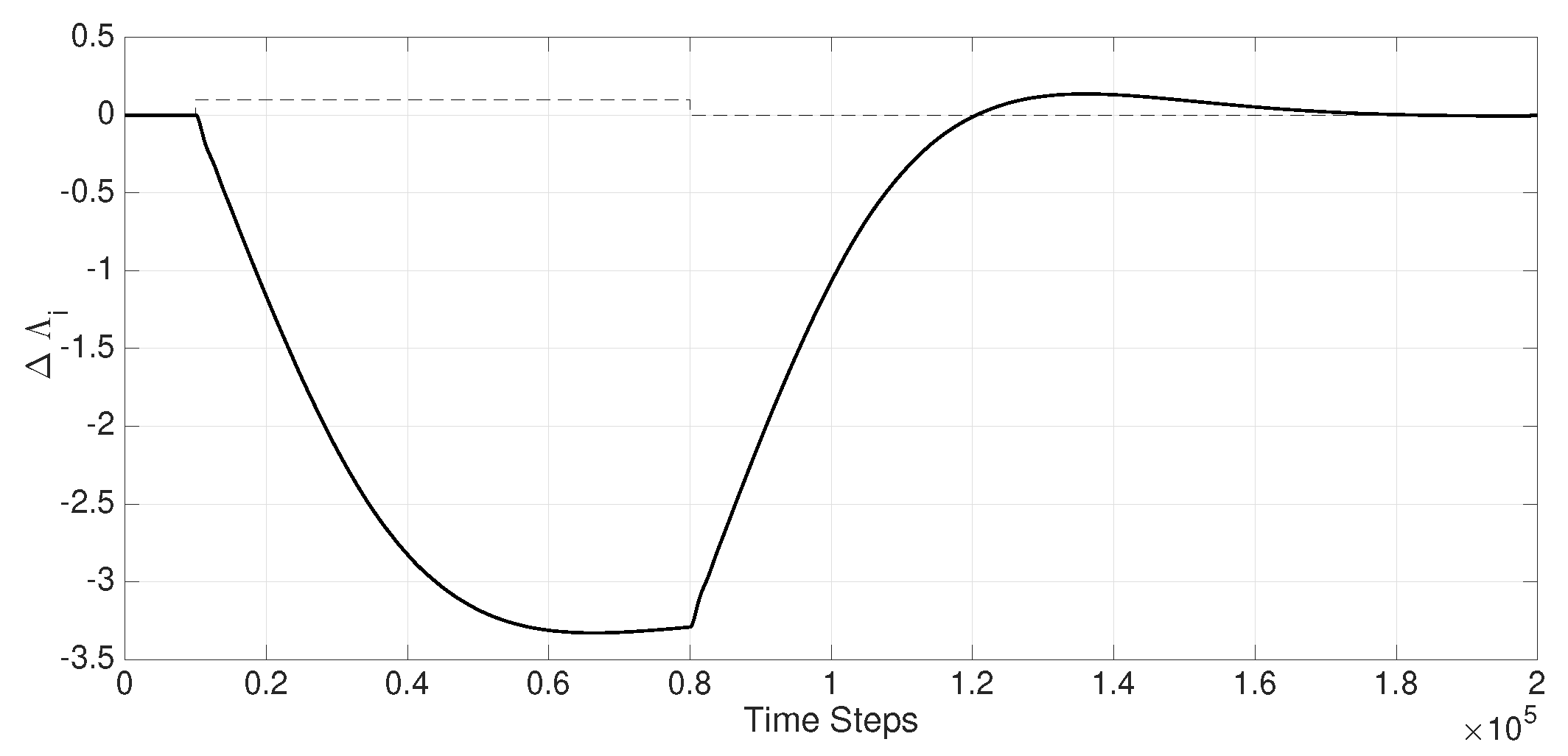

The thick line in

Figure 6 depicts the ACE

in response to a

load variations

(the dashed line). The ACE is the control parameter telemetered by the CCS

to all individual power generating units participating in the LFC. In the absence of a resilient filter mechanism, time-delay attacks on tele-communication links cause delayed inputs to CCS and delayed commands transmitted to the generating units.

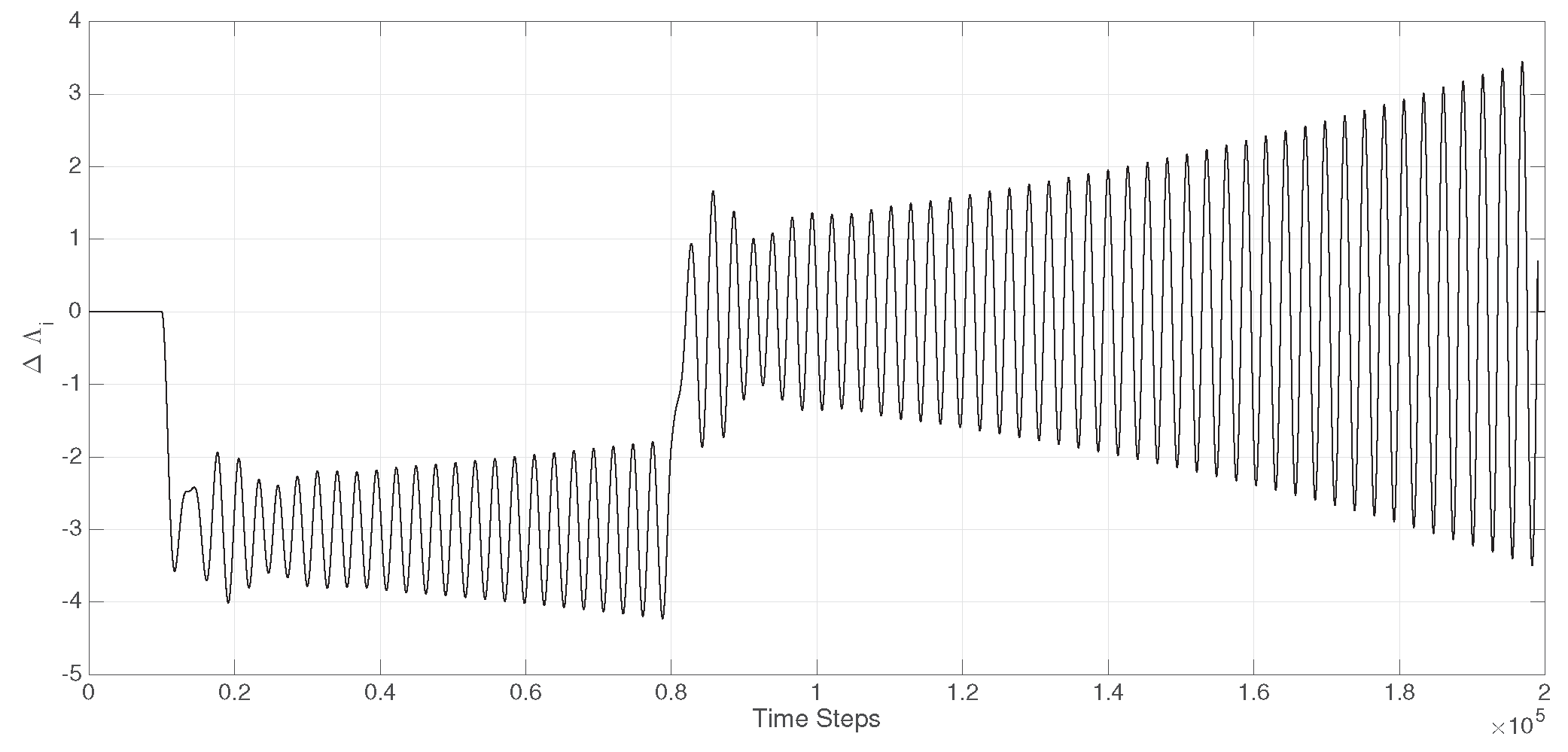

This inflicts uncontrollable swings in the area power system that disseminates to the entire power system

as exemplified in 5. For the purpose of comparison, the time-delayed ACE signal

without deploying delay-resilient cooperative filters would be as in

Figure 7. It is important to note that the CCS requires

to be transmitted from

(as explained in

Figure 2), as well as

to be transmitted from

, in order to compute

according to Equation (

3). Without employment of a time-delay resilient methodology, the delayed information

and

would cause instability in the CCS controlled which will be disseminated to

, which indeed is the phenomenon taking place in our case studies. Clearly, being at

it appears to be heuristically impossible to recover the real-time signal

from

, since the instability observed in

stems from a delayed signal transmitted from

. Consequently, recovery of

(while being at

) requires information that is clearly beyond the reach of

. The significance of the proposed methodology in this paper would now become clear, as it has been possible to restore normality in the entire CPS without requirement of subsystem’s information, and only through the filtering of available signals at the subsystems.

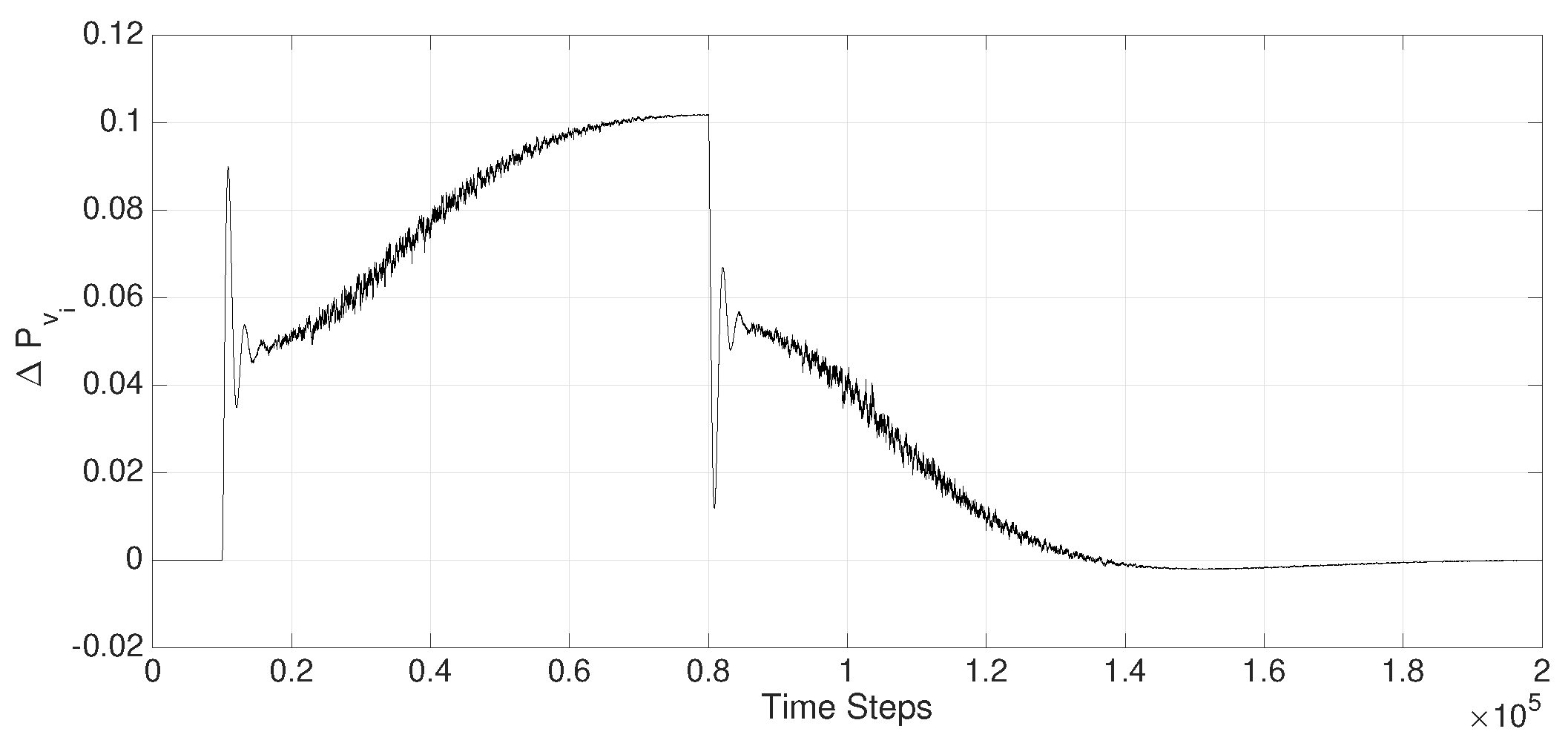

Figure 8 depicts the electric signal to the governor servo-valve of the generator in

in response to the disturbance

in the area load. It is evident that the

load change triggers a

command to the servo-valve in order to compensate for the load, ensuring complete balance in the supply-demand, which expectedly guarantees that

and

.

However, satisfactory functioning of the time-delay resilient LFC control scheme proposed in this paper strictly depends on the bandwidth of the tele-communication system and the speed of data transported between the system controllers, in comparison to the natural frequency of the system states.

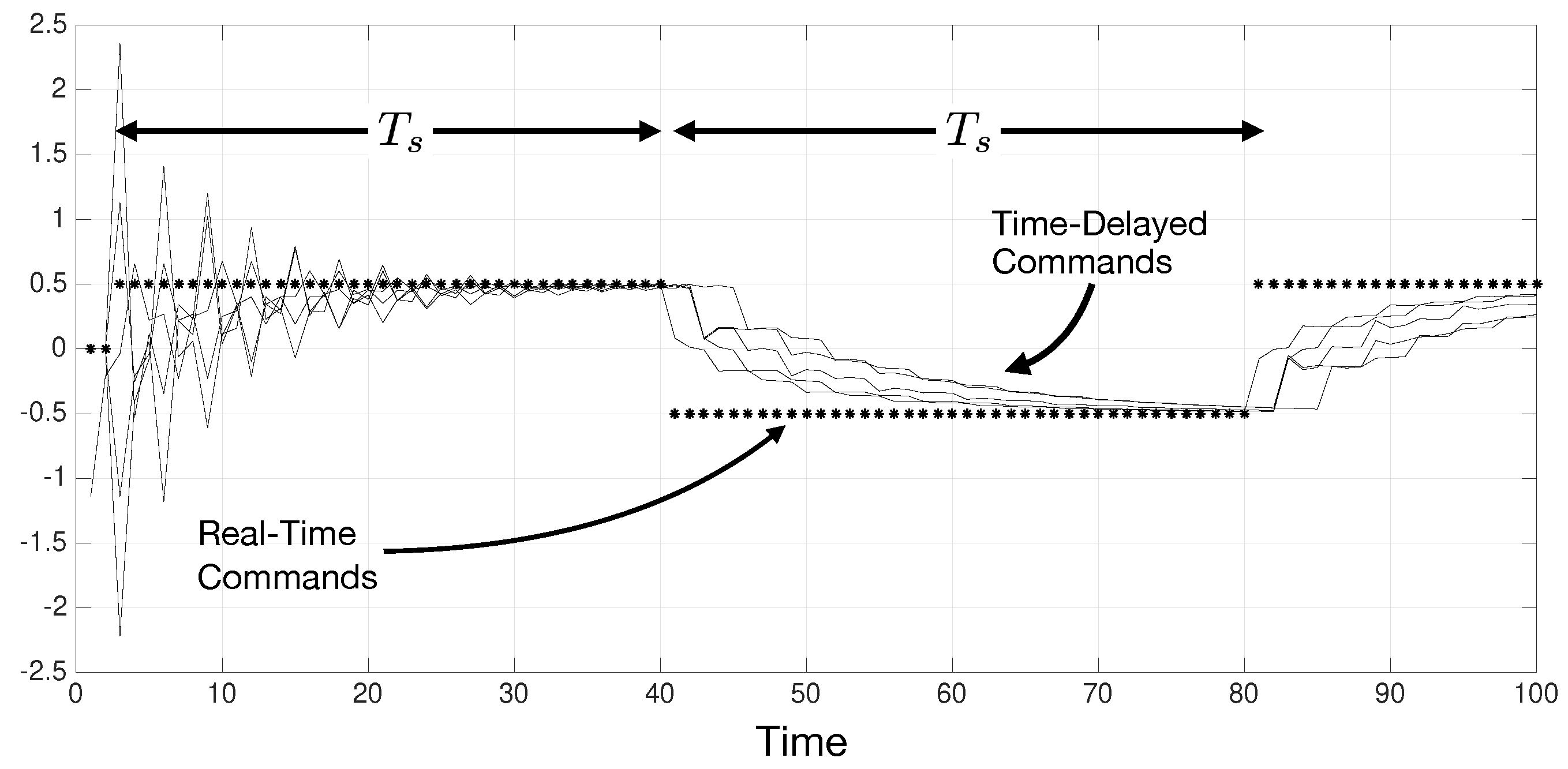

Figure 9 illustrates the importance of the tele-communication system bandwidth by comparing two scenarios. In the first scenario (thick line) a high bandwidth system is deployed, and in another attempt low bandwidth communication channels were being used. It is evident that inadequate bandwidth gives rise to instability in the power system (as depicted by the thin line in

Figure 9).

Finally,

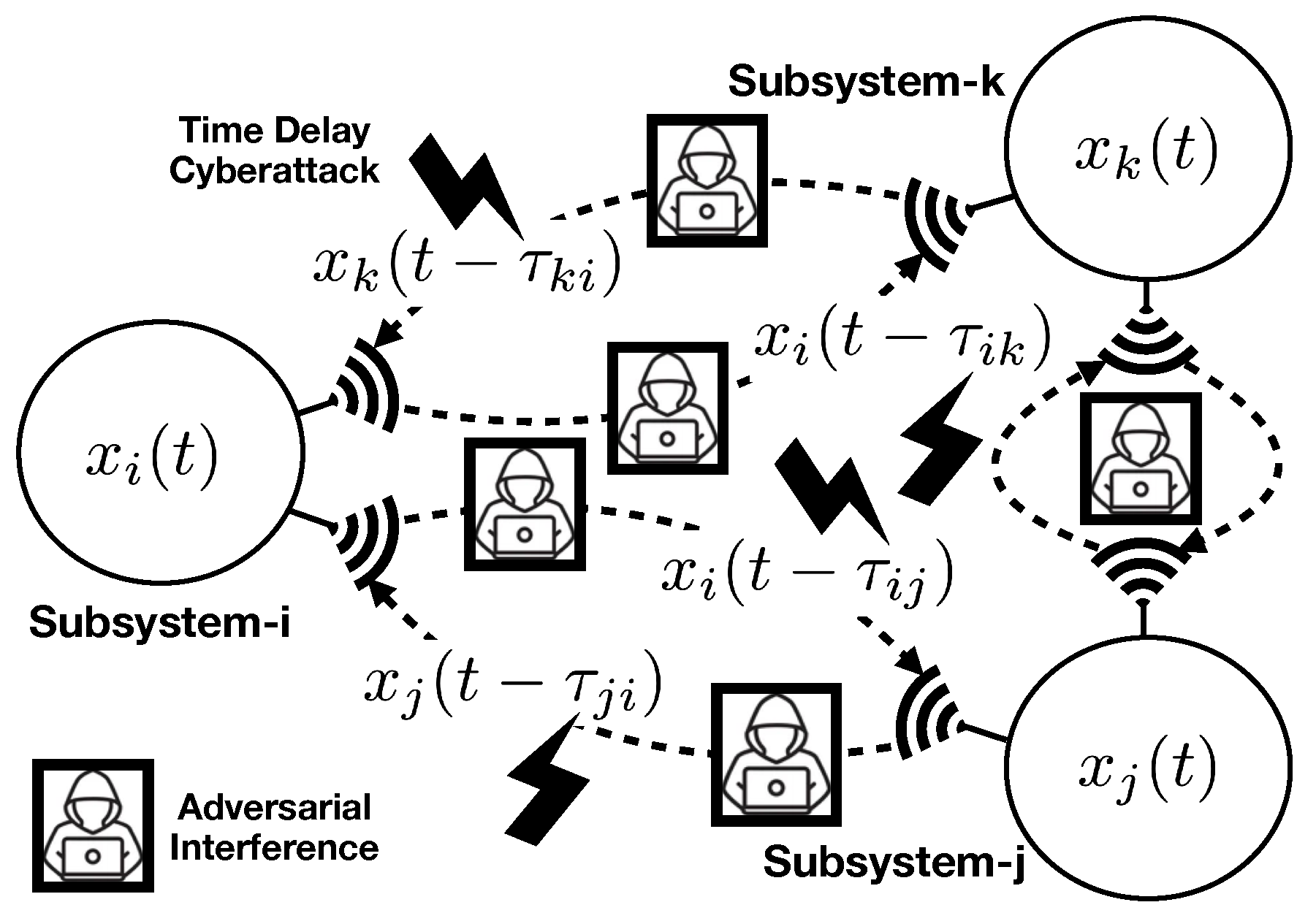

Figure 10 is a general schematic of a part of an interconnected CPS with a random topology. It is assumed that the subsystems are transmitting equivalent reference signals to others, where each signal is subject to a random time-delay.

Figure 11 is the simulation result of the cooperative filters for five interconnected subsystems in a discrete-time framework. It is evident that the filters can track the real-time reference signal despite of the unknown time-delays within a time-duration

.

Figure 1.

Block diagram of a frequency control mechanism for a generating station

contributing the LFC in a multi-area power system. The solid lines are hard-wired measurements/commands that are presumably immune from cyberattacks (as they are confined in

), where the dashed lines represent tele-metered data that are subject to TDS/DoS cyberattacks. Borrowed from [

5].

Figure 1.

Block diagram of a frequency control mechanism for a generating station

contributing the LFC in a multi-area power system. The solid lines are hard-wired measurements/commands that are presumably immune from cyberattacks (as they are confined in

), where the dashed lines represent tele-metered data that are subject to TDS/DoS cyberattacks. Borrowed from [

5].

Figure 2.

Schematics of a LFC power system with three area generating stations and the Centralized Control Station . The CPS in this figure can be represented as where denote the two substations, each also considered as a subsystem of the CPS. The tele-communication system can be further regarded as a subsystem in a more comprehensive model. However, this is not considered in this paper. The CCS and the tele-communication system comprise the cyber part of the system that is responsible for the data collection and processing, and the power system comprises the physical part of the CPS. The Front-End Processors (FEPs) are electronic apparatus inside the CCS that transmit/receive tele-communication signals and demodulate the state variables. The Remote Terminal Unit (RTU) is a micro-scale FEP with a similar function located in every substation. is a system state whose sensor (i.e., current and voltage power transformers) is located in a substation, and whose instantaneous value is transmitted to the CCS through an RTU. The CCS receives all , and computes for individual generating stations.

Figure 2.

Schematics of a LFC power system with three area generating stations and the Centralized Control Station . The CPS in this figure can be represented as where denote the two substations, each also considered as a subsystem of the CPS. The tele-communication system can be further regarded as a subsystem in a more comprehensive model. However, this is not considered in this paper. The CCS and the tele-communication system comprise the cyber part of the system that is responsible for the data collection and processing, and the power system comprises the physical part of the CPS. The Front-End Processors (FEPs) are electronic apparatus inside the CCS that transmit/receive tele-communication signals and demodulate the state variables. The Remote Terminal Unit (RTU) is a micro-scale FEP with a similar function located in every substation. is a system state whose sensor (i.e., current and voltage power transformers) is located in a substation, and whose instantaneous value is transmitted to the CCS through an RTU. The CCS receives all , and computes for individual generating stations.

Figure 3.

Schematics of a MAS time-delay resilient CPS, and the schematics of the cooperative filter . The agents in the MAS exchange information in order to recover a time-delayed state . is the input of the filter in (if , or can be any other conjecture available to which needs not be a correct estimate), and the output of the filter is , where is a small response time. It will be shown that , where is a negligible arbitrary settling time for the filter that will be controlled by the filter gain .

Figure 3.

Schematics of a MAS time-delay resilient CPS, and the schematics of the cooperative filter . The agents in the MAS exchange information in order to recover a time-delayed state . is the input of the filter in (if , or can be any other conjecture available to which needs not be a correct estimate), and the output of the filter is , where is a small response time. It will be shown that , where is a negligible arbitrary settling time for the filter that will be controlled by the filter gain .

Figure 5.

Performance of the time-delay resilient filter. The thin line represents in response to a load variation in , at and back to 0 at , for the case where a conventional LFC is in operation. Perilous swings in the system frequency are clear when the telemetered data are attacked by sufficiently long time-delays, resulting in pervasive instability in the power system (thinner line). The same scenario is repeated when resilient cooperative filters are deployed (solid thicker line) which demonstrates stability and a satisfactory LFC control.

Figure 5.

Performance of the time-delay resilient filter. The thin line represents in response to a load variation in , at and back to 0 at , for the case where a conventional LFC is in operation. Perilous swings in the system frequency are clear when the telemetered data are attacked by sufficiently long time-delays, resulting in pervasive instability in the power system (thinner line). The same scenario is repeated when resilient cooperative filters are deployed (solid thicker line) which demonstrates stability and a satisfactory LFC control.

Figure 6.

Variations in as a result of .

Figure 6.

Variations in as a result of .

Figure 7.

Time-Delayed ACE signal transmitted from without the employment of a delay-resilient cooperative filter system, and as a result of a 10% load disturbance .

Figure 7.

Time-Delayed ACE signal transmitted from without the employment of a delay-resilient cooperative filter system, and as a result of a 10% load disturbance .

Figure 8.

Adjustment of the servo-valve electric signal in response to the area load variations depicted in

Figure 5.

Figure 8.

Adjustment of the servo-valve electric signal in response to the area load variations depicted in

Figure 5.

Figure 9.

Affect of the tele-communication bandwidth. Inadequate bandwidth in tele-communication channels result in marginal instability as depicted by the thin line.

Figure 9.

Affect of the tele-communication bandwidth. Inadequate bandwidth in tele-communication channels result in marginal instability as depicted by the thin line.

Figure 10.

General architecture of a CPS, subject to adversarial time-delay cyberattacks. The exogenous states of the systems (

) are transmitted to adjacent subsystems with unknown time-delay and the output of

filters in each subsystem transmits the conditioned signal back to the source, hence, cooperative filters. The architecture shown in this figure results in time-delay resiliency in the CPS as demonstrated in

Figure 11.

Figure 10.

General architecture of a CPS, subject to adversarial time-delay cyberattacks. The exogenous states of the systems (

) are transmitted to adjacent subsystems with unknown time-delay and the output of

filters in each subsystem transmits the conditioned signal back to the source, hence, cooperative filters. The architecture shown in this figure results in time-delay resiliency in the CPS as demonstrated in

Figure 11.

Figure 11.

A discrete-time network of five interconnected agents transmitting equivalent reference signals (shown by the asterisks) to adjacent subsystems. The tele-communication channels are randomly delayed and the output of the cooperative filters are shown by thinner lines for each subsystem. It is evident that the delayed signals follow the real-time reference signal in a time-duration that is dependent of the filter gain and the topology of the network.

Figure 11.

A discrete-time network of five interconnected agents transmitting equivalent reference signals (shown by the asterisks) to adjacent subsystems. The tele-communication channels are randomly delayed and the output of the cooperative filters are shown by thinner lines for each subsystem. It is evident that the delayed signals follow the real-time reference signal in a time-duration that is dependent of the filter gain and the topology of the network.