1. Introduction

Poultry production has experienced remarkable growth within the livestock industry, becoming a favored choice for animal protein worldwide, including both meat and eggs [

1]. Economic and market projections indicate a 14% increase in global meat protein consumption by 2030, with poultry projected to grow at a rate of 17.8%. By 2030, poultry meat is expected to represent 41% of all protein from meat sources, solidifying its position as the protein of choice for many people globally [

2]. While high-density and fully commercial broiler systems contribute significantly to the sector’s growth and global production, it is essential to acknowledge the continued significance of small-scale poultry production [

3]. These traditional systems remain important in numerous developing and industrialized countries [

4,

5,

6]. Within small-scale production settings, backyard production systems (BPS) are recognized as the most widely distributed form of animal production in the world [

3].

Backyards are characterized by rearing multiple poultry species in variable flock sizes, with household consumption and informal trade as the primary destinations for poultry products, thereby providing an economic contribution to low-income families, mainly in rural areas [

7,

8]. Nevertheless, backyards usually lack the traditional biosecurity measures commonly observed in highly industrialized production systems, making them more susceptible to the introduction, maintenance, and dissemination of infectious pathogens [

7,

9,

10,

11]. Additionally, these systems act as an interface where domestic poultry species interact with wild animals, as domestic poultry kept in BPS frequently roam freely in search of food [

7,

11,

12,

13]. The interface between backyard poultry and wild birds is recognized as a high-risk area for the movement of priority pathogens affecting the poultry industry, as well as pathogens with zoonotic risk [

14]. This phenomenon has been previously documented in Chile, where systematic surveillance studies of avian influenza virus have revealed spillover from wild birds to backyard poultry [

11]. Consequently, BPS may serve as reservoirs and amplifiers of infectious diseases, significantly impacting both the commercial poultry industry and public health. Respiratory pathogens have a direct economic impact, primarily through increased animal mortality and decreased productivity indicators. Indirect costs are also incurred, encompassing treatments, vaccines, surveillance, as well as market losses due to restrictions on international trade [

15,

16].

Infectious bronchitis virus (IBV) and infectious laryngotracheitis virus (ILTV) are among the respiratory tract pathogens with the most significant economic impact [

17,

18]. Birds infected with these pathogens exhibit a range of clinical signs, including cough, respiratory distress, conjunctivitis, sinusitis, ocular and nasal discharge, general fatigue, reduced feed intake, increased morbidity, and substantial mortality [

19,

20,

21,

22,

23]. Furthermore, laying hens undergo a decline in both egg production and quality. Moreover, these pathogens can induce co-infections or multiple infections, potentially involving other viral, bacterial, or fungal pathogens, as sick birds tend to be more susceptible to secondary respiratory tract infections [

24,

25].

In Chile, poultry meat constitutes the primary form of meat production and consumption. Throughout 2021, the poultry industry made substantial contributions to both the country’s economy and food security, accounting for 48% of the total livestock production, with a significant proportion allocated for export [

26]. Based on the last national agricultural census, BPS accounts for 3.4% of the national poultry stock, with a concentration mainly in central Chile [

27]. Despite the endemic nature of IBV and ILTV in Chile, there exists limited knowledge regarding the prevalence of these pathogens in both industrial and backyard poultry systems. Prior research has primarily focused on characterizing IBV isolates from the poultry industry [

28,

29,

30]; however, minimal attention has been given to the study of ILTV, except for a few instances concerning wild bird reports [

31] and one study describing its circulation in BPS in the southern region of Chile [

32]. Therefore, the objective of this study was to investigate the prevalence and seroprevalence of IBV and ILTV in backyard poultry in central Chile.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Area and Study Design

The central region of the country has a Mediterranean climate [

33], which has proven advantageous for both agricultural and animal husbandry activities [

34]. Consequently, around 95% of poultry production is concentrated in central Chile, involving the rearing of over 43.5 million birds, which accounts for a substantial 83% of the total national poultry population. This same geographical region also hosts a significant number of BPS dedicated to poultry rearing [

8], which have been designated as the study units in this study.

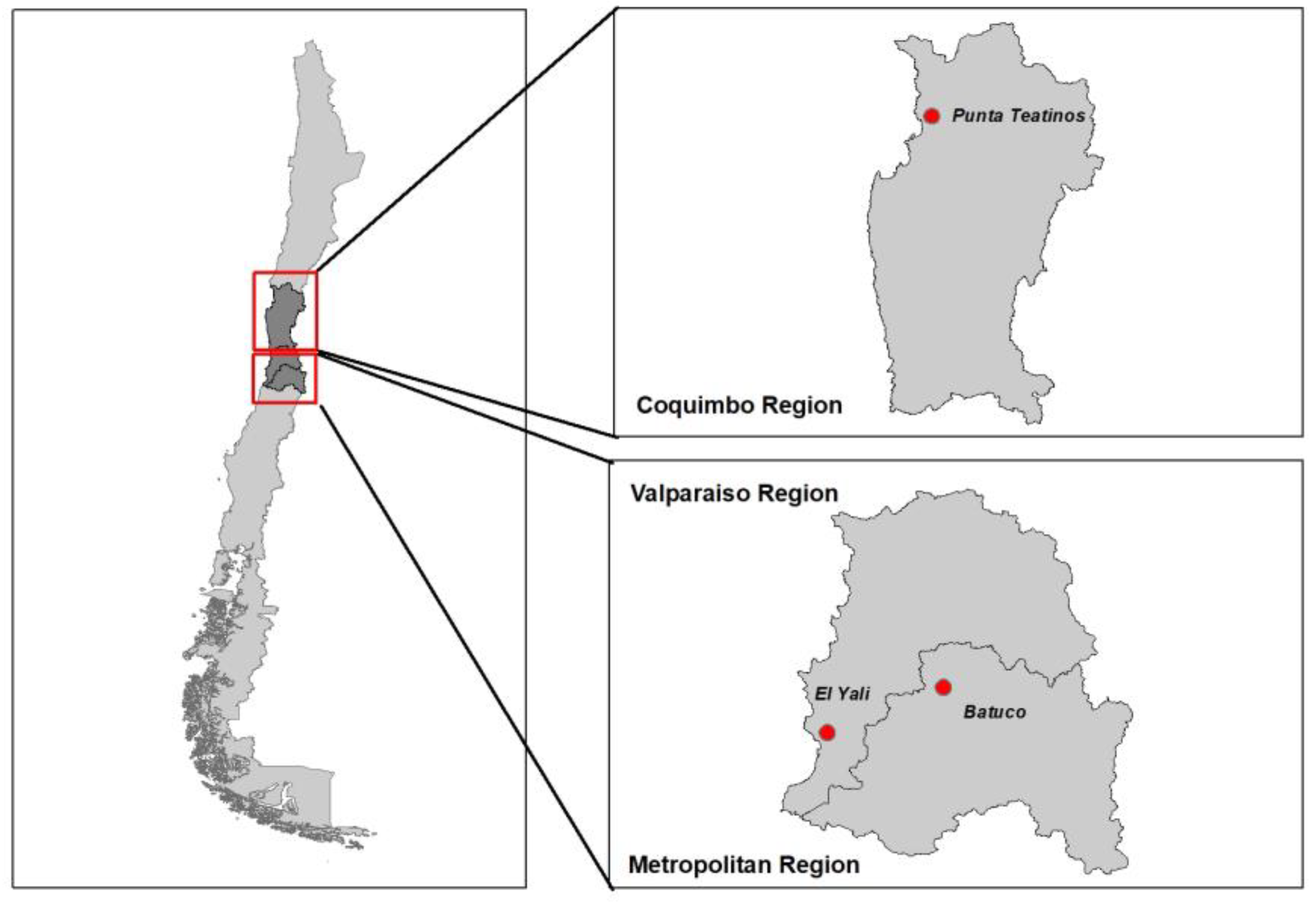

The study areas were defined based on wetlands recognized as important wild aquatic bird concentration areas in central Chile: i) Punta Teatinos (Coquimbo region), ii) Batuco wetland (Metropolitan region), and iii) El Yali National Reserve (Valparaíso region) (

Figure 1). The target population included poultry BPS located in the proximity of these wetlands. A cross-sectional study was undertaken in a total of 88 poultry BPS that were visited during January and February 2021. A BPS was defined as a family farm unit breeding up to 100 poultry [

8]. Blood samples were collected from eight poultry per BPS, or the entire flock if the BPS had fewer than eight birds. Blood samples were obtained from the brachial vein (1-3 mL) using blood collection tubes and refrigerated at 4°C upon arrival at the laboratory at the Faculty of Veterinary Medicine, University of Chile. Serum was obtained by centrifugation at 1,300 g for 15 minutes and stored at -20°C until analysis. Parallel to this, tracheal swabs were obtained from 92 birds from 11 BPS from Batuco and El Yali National Reserve study areas. The COVID-19 pandemic led to the early termination of the first sampling season; therefore, a second season was undertaken in November 2024 to increase the sample size for estimating prevalence. This sampling included 158 tracheal swabs collected from poultry belonging to 20 BPS located in Batuco and El Yali National Reserve. Disposable sterile swabs were placed into vials containing 1 mL of Universal Transport Media for sampling (Copan Group, Italy). Swab samples were kept at 4°C during transportation and stored at -80°C upon arrival at the laboratory.

2.2. Laboratory Analysis

Commercial ELISA kits were employed for serological analysis to determine the seroprevalence of IBV (CK119) and ILT (CK124; BioChek BV, Netherlands), following the manufacturer’s instructions. Each serum sample was tested in a single well of the antigen-coated plates provided in the kits for each pathogen. In brief, 100 µL of diluted serum (1:500) was added to the well and incubated for 30 min (IBV) or 1 h (ILTV) at room temperature. Subsequently, each well was washed four times with 350 µl of wash buffer, and 100 µl of conjugate reagent was added to the wells. After a second incubation at room temperature, plates were washed as described above. Following this, 100 µL of substrate reagent was added to each well, and the plate was incubated for an additional 15 min. Finally, the reaction in each well was quenched with 100 µl of stop solution. Absorbance was read using a Sunrise TM microplate reader (Tecan Group AG, Switzerland). Positive and negative controls provided in the kits were included in all plates. To estimate prevalence, tracheal swabs were analyzed using qPCR. Nucleic acid extraction from swab samples was performed using MagMax AI/ND-96 viral extraction kit (ThermoFisher Scientific, USA). For qPCR, commercial kits were used for IBV (CP108) and ILTV (CP104; BioChek BV, Netherlands) on a Mx3000P Stratagene™ thermocycler (Agilent Technologies, USA).

2.3. Data Analysis

IBV and ILTV prevalence and seroprevalence and 95% confidence intervals were estimated overall and stratified by study area (Di Rienzo et al., 2011). A BPS was considered positive if at least one sample tested positive. The comparison of flock size by study area was performed using Kruskal-Wallis, and statistical significance was set at ≤0.05.

3. Results

3.1. Seroprevalence

Across all study areas, a total of 449 serum samples (n = 229, n = 120, and n = 100 from Punta Teatinos, El Yali National Reserve, and Batuco, respectively) were collected from backyard poultry belonging to 88 BPS. Median flock size was 40 birds (Q1 = 25; Q3 = 70) and did not differ for study areas (

P = 0.783). Flock was composed mainly of chickens; however, other poultry species (such as ducks or geese) were also present in 31% of BPS. Seropositivity at the animal level was 82.2% (95% CI = 78.6% - 85.7%) and 57.2% (95% CI = 52.7% - 61.8%) for IBV and ILTV, respectively. Most of the birds (51.2%) tested seropositive for both pathogens, while only 53 birds (11.8%) were seronegative for both. Overall seroprevalence at the BPS level was 95.5% (95% CI = 91.1% - 99.8%) and 85.2% (95% CI = 77.8% - 92.6%) for IBV and ILTV, respectively (

Table 1). Among IBV-seropositive BPS, all screened poultry were seropositive in 71% of cases, compared to 36% for ILTV.

3.2. Prevalence

During the first sampling season, 92 tracheal swabs were collected, of which four (4.3%) tested qPCR-positive for IBV and 13 (14.1%) for ILTV. IBV-positive samples corresponded to three BPS (27.3%) and ILTV-positive samples to eight BPS (72.7%). During the second sampling season, 0.6% of samples (belonging to one positive farm from 20 BPS; 5.0%) tested qPCR-positive to IBV and 3.8% (six positive samples belonging to five farms from 20 BPS; 25.0%) to ILTV (

Table 2). No poultry tested qPCR-positive for both pathogens for either sampling season.

4. Discussion

This study assessed the prevalence and seroprevalence of IBV and ILTV in backyard poultry in central Chile. The results showed a significant circulation of both pathogens at the backyard level, constituting the first study investigating these viruses in such production settings in central Chile. Studies conducted in Chile over the last decade have revealed extensive deficiencies in the implementation of biosecurity measures in backyards. These studies identified non-permanent poultry confinement, the absence of functional fences to prevent contact with neighboring animals, the contact between poultry and wild birds, the presence of neighboring backyard animals, the absence of footbaths, among other biosecurity deficiencies [

7,

8,

10,

11,

12,

13]. Moreover, BPS often lack poultry disease management, including quarantine measures and treatment for birds exhibiting clinical signs, as well as vaccination campaigns [

8]. Consequently, BPS are recognized as high-risk hotspots for the introduction, maintenance, and spread of infectious diseases, underscoring the need for preventive and surveillance programs [

8,

35,

36,

37]. In our study, in 71% of IBV-seropositive BPS, all screened birds were seropositive, suggesting substantial within-flock exposure in the absence of preventive health measures [

38]. Both IBV and ILTV are typically included in Chile’s commercial poultry vaccination programs. However, outbreaks remain frequent and commonly underdiagnosed in small-scale production systems where vaccination is absent, primarily due to the unavailability of vaccine doses for small flocks. Dissemination of vaccine virus cannot be ruled out as a contributing factor to outbreaks in small-scale farms, given recent molecular evidence of vaccine-related ILTV strains circulating in unvaccinated backyard poultry in southern Chile [

32].

Our study revealed significant seroprevalence levels in backyard poultry at the BPS level, with 95.5% and 85.2% for IBV and ILTV, respectively. Conversely, poultry tracheal swabs analyzed using qPCR showed lower positivity rates, which may be attributed to the cross-sectional design employed in this study. Sampling was performed at a single time point at each BPS, potentially underestimating infection events within the study population. The ILTV positivity rate at the animal level reported in this study (14.2% and 3.8% for 2021 and 2024, respectively) is lower compared to a recent study conducted in backyard poultry from southern Chile, which reported a positivity rate of 90% [

32]. This difference could be attributed to the targeted population of each study. While Gatica and collaborators (2025) evaluated upper respiratory tract samples obtained during necropsy of poultry exhibiting respiratory clinical signs, we evaluated tracheal swabs collected from asymptomatic poultry. Results from the present study evidence a greater seroprevalence compared to previous cross-sectional studies conducted in poultry backyards [

39,

40]. This difference can be partially explained by the backyard population selected in our study, which was represented by farms with poor biosecurity implementation, located in proximity to wetlands. Consequently, a higher risk of contact between wild birds and backyard animals was expected. Verdugo and collaborators (2019) found a 20% prevalence of Gammacoronavirus closely related to IBV in Cormorants, which are one of the most abundant aquatic wild birds in Chile [

31]. This adds to previous evidence of IBV in aquatic wild birds [

41,

42,

43] indicating the potential role of wild birds as vectors facilitating the spread of IBV between wild and domestic avian populations [

44].

Both IBV and ILTV significantly impact poultry production, leading to reduced egg production, altered egg quality, and decreased growth rates, resulting in substantial economic losses [

19,

38]. This is particularly relevant since only 62% of backyard farmers achieve a positive economic balance from poultry production and the economic contribution (through household consumption or local trade) is especially important for backyards located further away from markets and for lower-income families [

7]. Our findings suggest that both IBV and ILTV are circulating within poultry BPS, potentially contributing to decreased productivity and negatively impacting overall poultry production outputs. The widespread detection of IBV and ILTV in BPS in central Chile, where it had not been previously reported, is concerning, as this region concentrates most of the country’s poultry production and poses a potential risk for transmission to commercial farms. Enhanced surveillance, particularly using molecular tests, is essential; however, these methods are often limited by cost and diagnostic time. Finally, the first sampling season of this study was conducted during the COVID-19 pandemic; therefore, interviews with backyard farmers were not included. Further information on farm characteristics and animal management could have provided valuable insights into risk factors at the backyard level. Future research should explore these factors to develop evidence-based preventive measures.

5. Conclusions

This study provided the first serological and molecular evidence of IBV and ILTV in backyard poultry in central Chile. Our findings revealed high seroprevalence rates, indicating widespread circulation of these pathogens in BPS. This evidence highlights the importance of enhanced molecular surveillance, particularly through qPCR, and the implementation of preventive measures in BPS. Educational programs aimed at improving poultry disease signs among backyard farmers are essential to mitigate the negative impacts of respiratory infectious diseases.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, CHW; methodology, PJ, KO, SR, CB, DT, CC, CO, DG, CT; software, CB; validation, CHW, PJB, and FDP; resources, CHW; data curation, CB.; writing—original draft preparation, CB and FDP; writing—review and editing, CB, FDP, PJB, SR; supervision, CHW, PJB, PG.; project administration, CHW; funding acquisition, CHW and PJB. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.”

Funding

This research project was financed by ANID Fondef IDeA I+D grant 23I10281 and Fondecyt grants 1241662 to P.J.-B. and 1241908 to C.H.-W.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The animal study protocol was approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (CICUA) of the University of Chile 19265-VET-UCH.

Conflicts of Interest

Authors declare no conflict of interests.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| BPS |

Backyard Production System |

| IBV |

Infectious Bronchitis Virus |

| ILTV |

Infectious Laryngotracheitis Virus |

| ELISA |

Enzyme-Linked Immunosorbent Assay |

| qPCR |

Quantitative Polymerase Chain Reaction |

| CI |

Confidence Interval |

| COVID-19 |

Coronavirus Disease 2019 |

References

- Mottet, A. and G. Tempio, Global poultry production: current state and future outlook and challenges. World’s poultry science journal, 2017. 73(2): p. 245-256. [CrossRef]

- OECD/FAO, OECD-FAO Agricultural Outlook 2021-2030. OECD Publishing. Paris, 2021.

- Sonaiya, E. and S. Swan, Small-scale poultry production, technical guide manual. FAO Animal Production and Health, 2004. 1.

- Alders, R.G., et al., Livestock across the world: diverse animal species with complex roles in human societies and ecosystem services. Animal Frontiers, 2021. 11(5): p. 20-29. [CrossRef]

- Diao, X., et al., The future of small farms: innovations for inclusive transformation, in Science and Innovations for Food Systems Transformation. 2023, Springer International Publishing Cham. p. 191-205.

- von Braun, J., et al., Science and innovations for food systems transformation. 2023: Springer Nature.

- Di Pillo, F., et al., Backyard poultry production in Chile: animal health management and contribution to food access in an upper middle-income country. Preventive Veterinary Medicine, 2019. 164: p. 41-48. [CrossRef]

- Hamilton-West, C., et al., Characterization of backyard poultry production systems and disease risk in the central zone of Chile. Research in veterinary science, 2012. 93(1): p. 121-124. [CrossRef]

- Bravo-Vasquez, N., et al., Risk factors and spatial relative risk assessment for influenza A virus in poultry and swine in backyard production systems of central Chile. Vet Med Sci, 2020. 6(3): p. 518-526. [CrossRef]

- Baumberger, C., et al., Swine Backyard Production Systems in Central Chile: Characterizing Farm Structure, Animal Management, and Production Value Chain. Animals, 2023. 13(12): p. 2000. [CrossRef]

- Jimenez-Bluhm, P., et al., Circulation of influenza in backyard productive systems in central Chile and evidence of spillover from wild birds. Preventive veterinary medicine, 2018. 153: p. 1-6. [CrossRef]

- Bravo-Vasquez, N., et al., Presence of influenza viruses in backyard poultry and swine in El Yali wetland, Chile. Preventive veterinary medicine, 2016. 134: p. 211-215. [CrossRef]

- Bravo-Vasquez, N., et al., Risk factors and spatial relative risk assessment for influenza A virus in poultry and swine in backyard production systems of central Chile. Veterinary medicine and science, 2020. 6(3): p. 518-526. [CrossRef]

- Ayala, A.J., M.J. Yabsley, and S.M. Hernandez, A review of pathogen transmission at the backyard chicken–wild bird interface. Frontiers in veterinary science, 2020. 7: p. 539925. [CrossRef]

- Jones, P., et al., A review of the financial impact of production diseases in poultry production systems. Animal production science, 2018. 59(9): p. 1585-1597. [CrossRef]

- Di Pillo, F., et al., Movement Restriction and Increased Surveillance as Efficient Measures to Control the Spread of Highly Pathogenic Avian Influenza in Backyard Productive Systems in Central Chile. Frontiers in Veterinary Science, 2020. 7(424). [CrossRef]

- Chaves Hernández, A., Poultry and avian diseases. Encyclopedia of Agriculture and Food Systems.: 504–520. 2014.

- Laamiri, N., et al., Accurate detection of avian respiratory viruses by use of multiplex PCR-based luminex suspension microarray assay. Journal of Clinical Microbiology, 2016. 54(11): p. 2716-2725. [CrossRef]

- Hidalgo, H., Infectious laryngotracheitis: a review. Brazilian Journal of Poultry Science, 2003. 5: p. 157-168. [CrossRef]

- Ou, S.-C. and J.J. Giambrone, Infectious laryngotracheitis virus in chickens. World journal of virology, 2012. 1(5): p. 142. [CrossRef]

- Agunos, A., et al., Review of nonfoodborne zoonotic and potentially zoonotic poultry diseases. Avian diseases, 2016. 60(3): p. 553-575. [CrossRef]

- Goraya, M.U., L. Ali, and I. Younis, Innate immune responses against avian respiratory viruses. Hosts and Viruses, 2017. 4(5): p. 78. [CrossRef]

- Brown Jordan, A., et al., A review of eight high-priority, economically important viral pathogens of poultry within the Caribbean region. Veterinary sciences, 2018. 5(1): p. 14. [CrossRef]

- Seifi, S., K. Asasi, and A. Mohammadi, Natural co-infection caused by avian influenza H9 subtype and infectious bronchitis viruses in broiler chicken farms. Veterinarski Arhiv, 2010. 80(2): p. 269-281.

- Abdo, W., et al., Acute Outbreak of Co-Infection of Fowl Pox and Infectious Laryngotracheitis Viruses in Chicken in Egypt. Pakistan Veterinary Journal, 2017. 37(3).

- ChileCarne. La industria en cifras. Resumen de cifras 2021. 2022 July 28th 2023 [cited 2023 August 22nd]; Available from: https://www.chilecarne.cl/la-industria-en-cifras/.

- INE. Censo Agropecuario y Forestal. Santiago, Chile. Instituto Nacional de Estadística; 2021. 2021; Available from: https://www.ine.gob.cl/censoagropecuario.

- Cubillos, A., et al., Characterisation of strains of infectious bronchitis virus isolated in Chile. Avian Pathol, 1991. 20(1): p. 85-99. [CrossRef]

- Lopez, J.C., R. McFarlane, and J. Ulloa, Detection and characterization of infectious bronchitis virus in Chile by RT-PCR and sequence analysis. Archivos de Medicina Veterinaria, 2006. 38(2): p. 175-178.

- Guzmán, M., L. Sáenz, and H. Hidalgo, Molecular and Antigenic Characterization of GI-13 and GI-16 Avian Infectious Bronchitis Virus Isolated in Chile from 2009 to 2017 Regarding 4/91 Vaccine Introduction. Animals, 2019. 9(9): p. 656. [CrossRef]

- Verdugo, C., et al., Molecular identification of avian viruses in neotropic cormorants (Phalacrocorax brasilianus) in Chile. Journal of Wildlife Diseases, 2019. 55(1): p. 105-112. [CrossRef]

- Gatica, T., et al., Development of a qPCR Tool for Detection, Quantification, and Molecular Characterization of Infectious Laryngotracheitis Virus Variants in Chile from 2019 to 2023. Animals, 2025. 15(11): p. 1623. [CrossRef]

- Di Castri, F. and E.R. Hajek, Bioclimatología de Chile. 1976: Vicerrectoría Académica de la Universidad Católica de Chile Santiago, Chile.

- Aguayo, M., et al., Cambio del uso del suelo en el centro sur de Chile a fines del siglo XX: Entendiendo la dinámica espacial y temporal del paisaje. Revista chilena de historia natural, 2009. 82(3): p. 361-374. [CrossRef]

- Baumberger, C., et al., Exposure Practices to Animal-Origin Influenza A Virus at the Animal–Human Interface in Poultry and Swine Backyard Farms. Zoonoses and Public Health, 2025. 72(1): p. 42-54. [CrossRef]

- Conan, A., et al., Biosecurity measures for backyard poultry in developing countries: a systematic review. BMC veterinary research, 2012. 8: p. 1-10. [CrossRef]

- Iqbal, M., Controlling avian influenza infections: The challenge of the backyard poultry. Journal of molecular and genetic medicine: an international journal of biomedical research, 2009. 3(1): p. 119. [CrossRef]

- Bhuiyan, M.S.A., et al., Infectious bronchitis virus (gammacoronavirus) in poultry farming: vaccination, immune response and measures for mitigation. Veterinary sciences, 2021. 8(11): p. 273. [CrossRef]

- Gutierrez-Ruiz, E., et al., A serological survey for avian infectious bronchitis virus and Newcastle disease virus antibodies in backyard (free-range) village chickens in Mexico. Tropical Animal Health and Production, 2000. 32: p. 381-390. [CrossRef]

- Pohjola, L., et al., A survey for selected avian viral pathogens in backyard chicken farms in Finland. Avian Pathology, 2017. 46(2): p. 166-172. [CrossRef]

- Chen, G.-Q., et al., Identification and survey of a novel avian coronavirus in ducks. PloS one, 2013. 8(8): p. e72918. [CrossRef]

- Hughes, L.A., et al., Genetically diverse coronaviruses in wild bird populations of northern England. Emerging infectious diseases, 2009. 15(7): p. 1091. [CrossRef]

- Woo, P., et al., Discovery of seven novel mammalian and avian. 2012, Coronaviruses. [CrossRef]

- Miłek, J. and K. Blicharz-Domańska, Coronaviruses in avian species–review with focus on epidemiology and diagnosis in wild birds. Journal of veterinary research, 2018. 62(3): p. 249. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).