1. Introduction

Heat conduction problems are prevalent across various engineering applications, including mechanical engineering, architectural engineering, and the thermal management of electronic devices. The inverse problem of temperature fields[

1,

2], which involves deducing the distribution of heat sources and boundary conditions from known temperature data, is a critical technique for addressing these challenges. Traditional numerical simulation methods, particularly those based on finite difference methods (FDM)[

3] and finite element methods (FEM)[

4], often rely on comprehensive sensor networks and detailed boundary conditions. However, in practical scenarios, sensor deployment frequently suffers from sparsity, making it difficult to accurately capture the complete temperature field information, thereby complicating the solution of the temperature field inverse problem.

Classical methods for solving thermal inverse problems primarily encompass analytical methods[

5], regularization techniques[

6], optimization strategies[

7], Bayesian approaches[

8], and iterative inversion methods[

9]. Analytical methods yield precise solutions through mathematical derivation; in the fields of fluid flow and heat transfer, Fourier transforms, Green's functions, and Laplace inversion[

10] are widely utilized. These methods typically apply to linear problems with simple models and regular boundary conditions[

12]. For instance, in steady-state conduction problems where thermal conductivity varies linearly with temperature, inverse analysis can be employed for parameter estimation. Although analytical solutions can offer accurate results with clear physical interpretations, they are mainly constrained by stringent requirements regarding the linearity of the problem and geometric regularity, making them inadequate for complex nonlinear problems and irregular geometries.

Ill-posedness is an inherent challenge of inverse problems, where even minor data noise can lead to significant deviations in solutions. Regularization methods aim to stabilize solutions by introducing additional constraints, thereby enhancing robustness. Tikhonov regularization is one of the most established techniques, which smooths solutions by adding a penalty term to the least squares objective function, achieving a balance between data fitting error and the "smoothness" or "simplicity" of the solution[

13]. In the context of heat transfer, regularization methods are extensively employed to identify unknown parameters within mathematical models. For instance, when dealing with ill-posed problems, various regularization techniques can be selected with appropriately adjusted regularization parameters[

14]. However, the selection of these parameters often depends on empirical judgment, and inappropriate choices may lead to erroneous results.

Optimization methods convert inverse problems into optimization tasks, estimating unknown parameters by minimizing the residuals between observed data and model predictions. Prominent approaches include nonlinear least squares, constrained optimization, and variational methods[

15]. These methods are versatile and theoretically sound, finding broad applications in parameter estimation, imaging, and system identification. For example, in intricate heat transfer scenarios, they can optimize thermal performance designs[

16]. Nevertheless, these methods are susceptible to local optima and may struggle with multimodal problems, while computational efficiency is restricted by the problem's scale and complexity[

17]. Bayesian methods, rooted in probability theory, treat unknown parameters as random variables, updating posterior probability distributions by synthesizing prior knowledge with observational data to quantify uncertainty. Techniques such as Markov Chain Monte Carlo (MCMC) and variational Bayes are commonly employed[

18]. This approach excels in managing complex models and quantifying uncertainties, as exemplified by predicting the energy consumption of HVAC systems using Bayesian networks[

19]. The primary challenges arise from the computational demands of high-dimensional parameter spaces and the intricacies involved in model construction. Iterative inversion methods approach the true solution through successive iterations, with prevalent algorithms including Landweber iteration, Conjugate Gradient Method (CGM), and Gauss-Newton methods[

20]. These techniques are straightforward to implement, capable of addressing nonlinear problems, and are widely used in image reconstruction, bioelectrical impedance tomography (BIT), and seismic imaging. For example, when solving ill-posed linear inverse problems, a recently proposed second-order dynamic method (SODM) integrates Tikhonov regularization with second-order asymptotic regularization and employs a dual-parameter strategy, demonstrating superiority over conventional methods under noisy conditions[

21]. However, it is essential to note that this approach has slower convergence rates, sensitivity to initial values, and demands meticulous parameter tuning[

22].

With the advancement of machine learning and data-driven methodologies, data-based field reconstruction techniques have increasingly emerged as effective tools for addressing related challenges. These approaches effectively reconstruct accurate temperature field distributions by leveraging limited sensor data, integrated with dimensionality reduction techniques and model simplification strategies. Specifically, the Proper Orthogonal Decomposition (POD) method[

23] facilitates dimensionality reduction of temperature field data, extracting principal feature modes and thereby simplifying complex heat transfer problems. The Gappy POD method[

24] is an extension of POD designed to handle incomplete data. In heat transfer scenarios, complete temperature field data may not be obtainable due to sensor malfunctions or data transmission errors. Gappy POD allows for the reconstruction of the full temperature field from available partial data. For example, research conducted by Wang et al.[

25] involved deploying a limited number of sensors, combined with Computational Fluid Dynamics (CFD) simulations and the Gappy POD methodology to reconstruct the temperature field distribution across an entire indoor space. Moreover, Xu et al.[

26] addressed the severe missing data issues in meteorological observations by generating a POD basis using the WRF model and subsequently employing Gappy POD to fill in the gaps, successfully reconstructing the temperature field in the Tibetan region. The POD-RBF (Proper Orthogonal Decomposition - Radial Basis Function) method effectively reconstructs temperature fields with a small number of measurement points. This technique utilises POD to extract key characteristics of the temperature field and employs RBF interpolation for complete temperature reconstruction, thus striking a balance between computational efficiency and accuracy. Research by Wang et al.[

27] demonstrated the use of the POD-RBF method to rapidly reconstruct the temperature field of printed circuit boards (PCBs) based on minimal sensor data, facilitating monitoring and control of thermal behaviour in devices. The Multilayer Perceptron (MLP) represents a type of artificial neural network capable of learning nonlinear relationships between inputs and outputs. The POD-MLP method integrates POD dimensionality reduction with MLP neural networks, aiding in the estimation of physical system states, including thermal and flow conditions. Qi et al.[

28] leveraged the POD-MLP technique for real-time monitoring and reconstruction of the surface temperature field of batteries. The accuracy of data-driven field reconstruction methods significantly depends on the sparse sensor layout. A strategically designed sensor arrangement can not only enhance the precision of temperature field reconstruction but also effectively reduce data acquisition costs and computational burdens. However, many existing reconstruction methods overlook the influence of sparse sensor configurations, often resorting to uniform or random placement techniques, which can lead to considerable variability in reconstruction accuracy. Willcox et al.[

29] optimized the sparse sensor placement for the Gappy POD method using matrix stability criteria, specifically condition numbers, achieving commendable results; however, this approach demands iterative and repeated matrix computations, resulting in lower time efficiency. It also necessitates integration with optimization methods to accelerate the selection process in complex scenarios. Lauzon et al.[

29] introduced the S-OPT method, which quickly determines optimal sensor configurations by scanning orthogonal basis matrices to maximise an S-metric. Yet, this method proves sensitive to the dimensionality of the basis, requiring higher-order modes for accurate results in complex fields such as turbulence. Yuan et al.[

30] proposed a method utilising the Pearson correlation coefficients of matrices to gauge the interrelationships between sensors and employed a threshold-based strategy to swiftly identify optimal sensor placement locations, known as the Correlation Coefficient Filtering Method (CCFM). This method enables sparse sensor layout optimization under low-modal and confined regional conditions.

Building upon the clustering-based dimensionality reduction method guided by pod structures proposed (C-POD) by Yuan et al.[

30], this paper introduces the Gappy C-POD approach, incorporating principles from inverse problem solving, and develops a multi-scale sample database alongside various sensor layout optimization strategies to facilitate its implementation. This study systematically compares the reconstruction pathways, accuracy, and robustness of four data-driven reconstruction methods—Gappy POD, Gappy C-POD, POD-RBF, and POD-MLP—across different modal truncation numbers, database sizes, and selection strategies, focusing on steady-state and transient heat conduction problems with multiple internal heat sources in two dimensions. The findings aim to provide theoretical foundations and methodological guidance for the engineering modelling and optimisation design of temperature field inverse problems.

3. Reconstruction of Steady-State Temperature Field

3.1. Case Study Overview

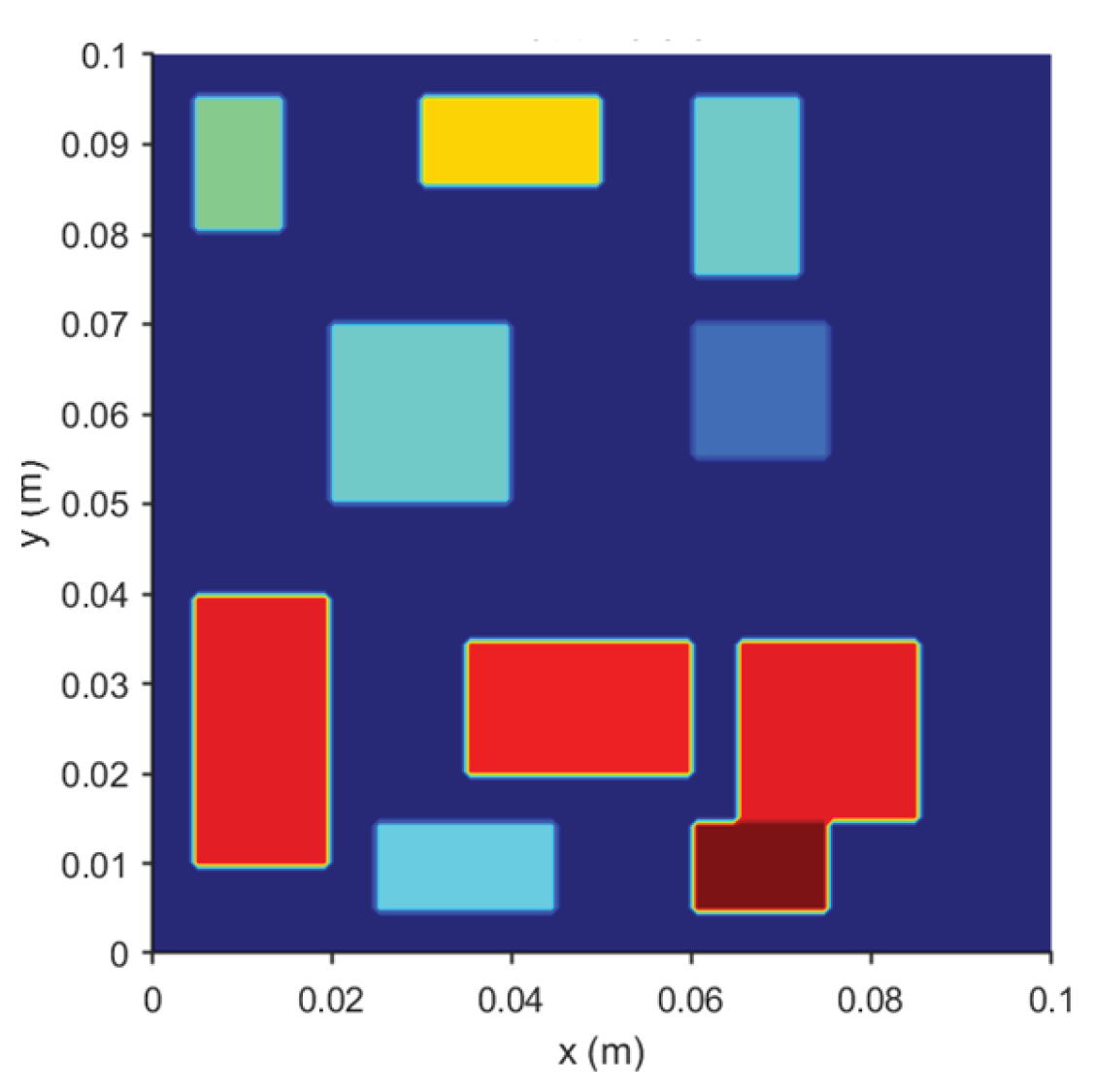

To evaluate the applicability and robustness of the methodology for solving inverse problems related to temperature fields, this study presents a classic example of a two-dimensional steady-state heat conduction problem, as illustrated in

Figure 1. The model simulates the heat transfer process influenced by multiple irregularly distributed heat sources and certain isothermal boundary conditions, employing the finite difference method for numerical analysis.

3.1.1. Geometric Parameters and Heat Source Distribution

As depicted in

Figure 1, the computational domain in this case has a side length of L = 0.1 m. Within this domain, there are ten rectangular heat sources, the locations, dimensions, and intensity of which are specified in

Table 1:

3.1.2. Governing Equation

The governing equation is a nonlinear steady-state heat conduction equation, represented as shown in Equation (18):

Where is defined as a two-dimensional square area; and isthe heat source term is included.

3.1.3. Initial Conditions

The initial temperature field is uniformly distributed, as expressed in Equation (19):

3.1.4. Boundary Conditions

The boundary conditions are specified as mixed. The left and right boundaries are characterised by adiabatic conditions:

The upper boundary also maintains an adiabatic condition:

For the lower boundary, most of it is adiabatic, except for the central position which is kept at a constant temperature, as illustrated in Equation (22):

3.1.5. Solution Method

The solution is obtained through the finite difference method:

Grid: A uniform rectangular grid of 100×100 is employed;

Spatial Discretisation: A nonlinear five-point difference scheme is used;

Nonlinear Solving: The Gauss-Seidel iterative method is applied as per Equation (23):

where

,the representation of other directions is analogous. The convergence criterion is established in Equation (24), with a maximum iteration limit set to 10,000.

3.2. Construction of Verification Set

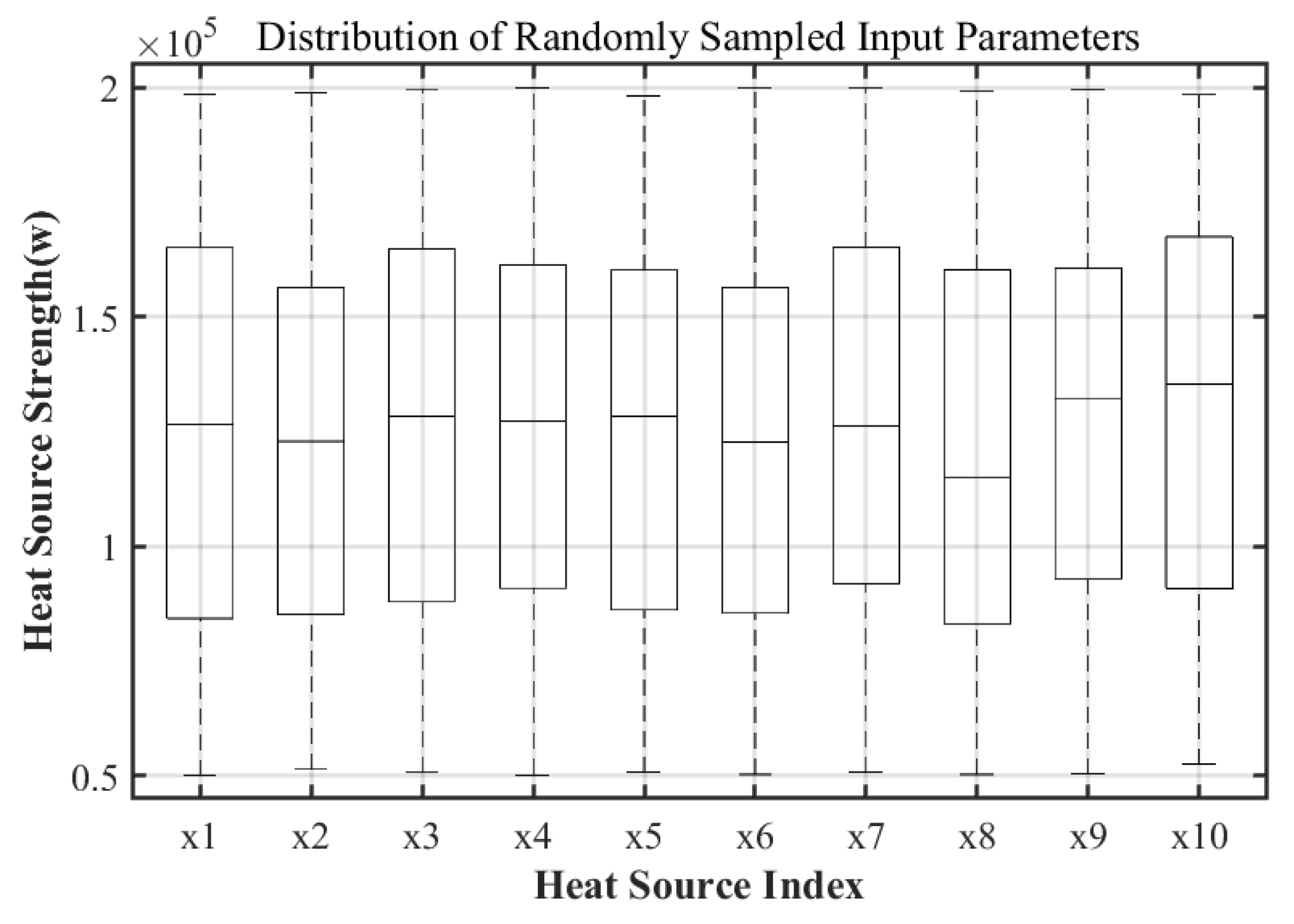

As indicated in section 2.1, the thermal conduction problem incorporates ten internal heat sources as independent variables. A test set comprised of 200 randomly sampled groups has been created, with the distribution depicted in Boxplot 2. The boxplot illustrates the thermal power values for each heat source, uniformly spanning the defined range of (0.5–2.0)×10⁵ W, devoid of outliers. This indicates sufficient input coverage for both model training and validation purposes.

Figure 2.

Distribution of the test set input parameters (boxplot).

Figure 2.

Distribution of the test set input parameters (boxplot).

3.3. Database Construction

To establish a representative and widely encompassing sample database, this study employs three typical sampling methods: Latin Hypercube Sampling[

32], Sobol Sequence Sampling[

33], and Maximum Distance Sampling[

34]. These methods are applied to sample the combination space of ten thermal power variables. Given the dimensionality of the variables, denoted as

d=10, sample sizes are set at five, ten, twenty, thirty, forty, and fifty times the number of variables, resulting in the generation of 50, 100, 200, 300, 400, and 500 sets of independent variable combinations. This yields a total of 18 multi-scale sample databases that will be utilized for subsequent modeling and analysis.

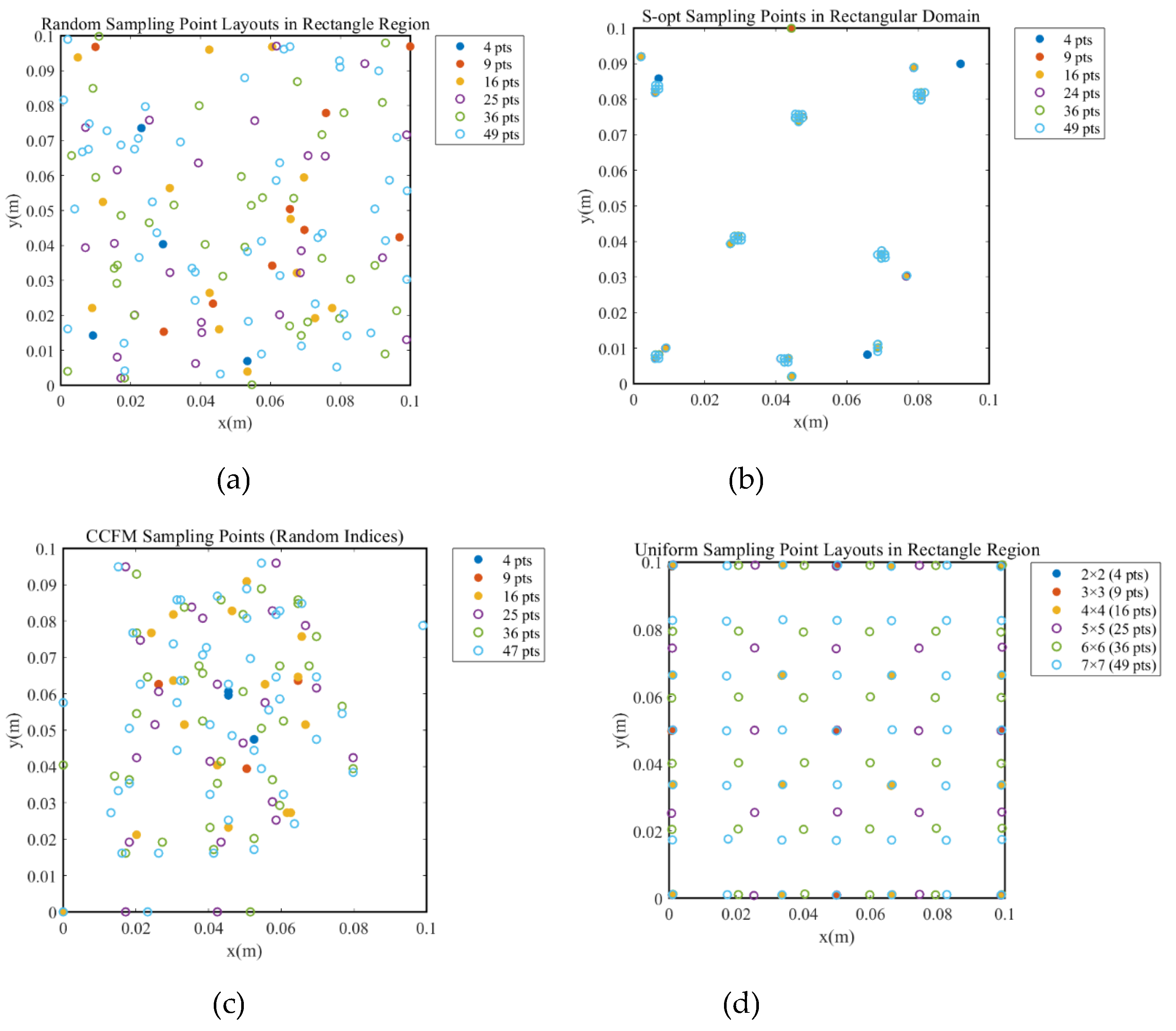

3.4. Sparse Sensor Layout Optimization Methods

To investigate the impact of different sparse sensor layout optimization methods on field reconstruction performance, four representative sensor placement strategies are selected: random sampling, S-OPT method, Correlation Coefficient Filtering Method (CCFM), and uniform sampling. For each strategy, the number of sensors is varied at 4, 9, 16, 25, 36, and 49, resulting in a total of 24 distinct sparse sensor layout configurations, as illustrated in

Figure 3.

3.5. Reconstruction Methods

To evaluate the reconstruction capabilities of various methods, this study compares four representative approaches: Gappy Proper Orthogonal Decomposition (POD), Gappy Composite Proper Orthogonal Decomposition (C-POD), POD-Radial Basis Function (RBF), and POD-Multilayer Perceptron (MLP). Under the conditions specified in items (3) to (5), a systematic investigation was conducted based on the validation set detailed in

Section 2. This research focused on the impact of various factors on reconstruction accuracy, including different dimensional reduction modes, database construction methods, sparse sensor layout optimization strategies, and reconstruction methods. To quantify the performance of each reconstruction approach concerning maximum deviation constraints and overall accuracy, the study employs two key metrics: the minimum maximum relative error (Minimum Maximum Relative Error, MRE) and the minimum average relative error (Minimum Average Relative Error, MARE), defined mathematically by equations (25) and (26):

where n represents the total number of samples; the reconstruction value for the i-th temperature measurement point is represented as

; and the actual value for the i-th temperature measurement point is represented as

.

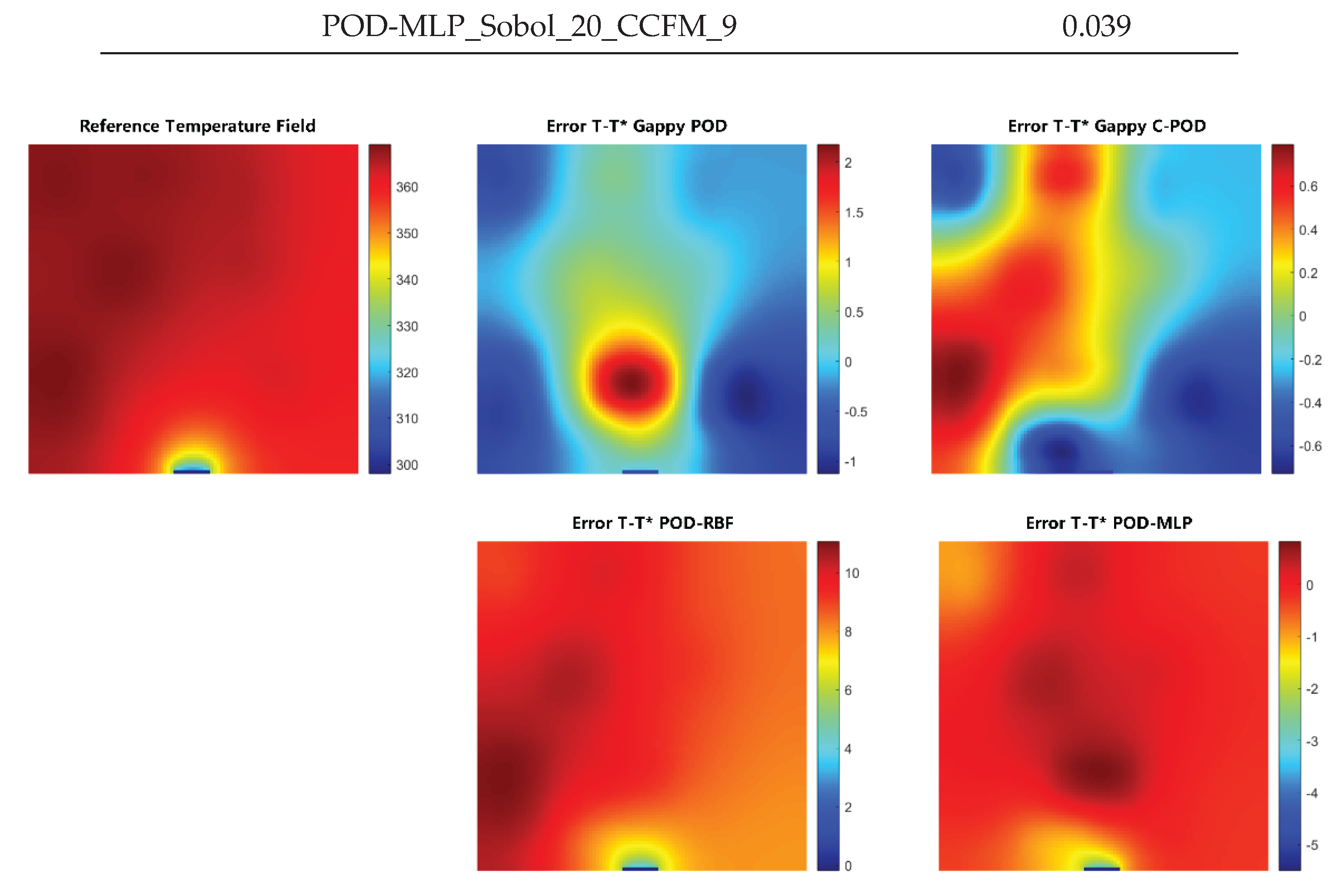

The reconstruction approach is denoted as x_y_z_m, where x indicates the reconstruction method (Gappy POD, Gappy C-POD, POD-RBF, POD-MLP), y refers to the database size (5, 10, 20, 30, 40, 50 times the number of independent variables), z denotes the point selection strategy (CCFM, S-OPT, Random, Uniform), and m indicates the number of selected points (4, 5, 16, 25, 36, 49).

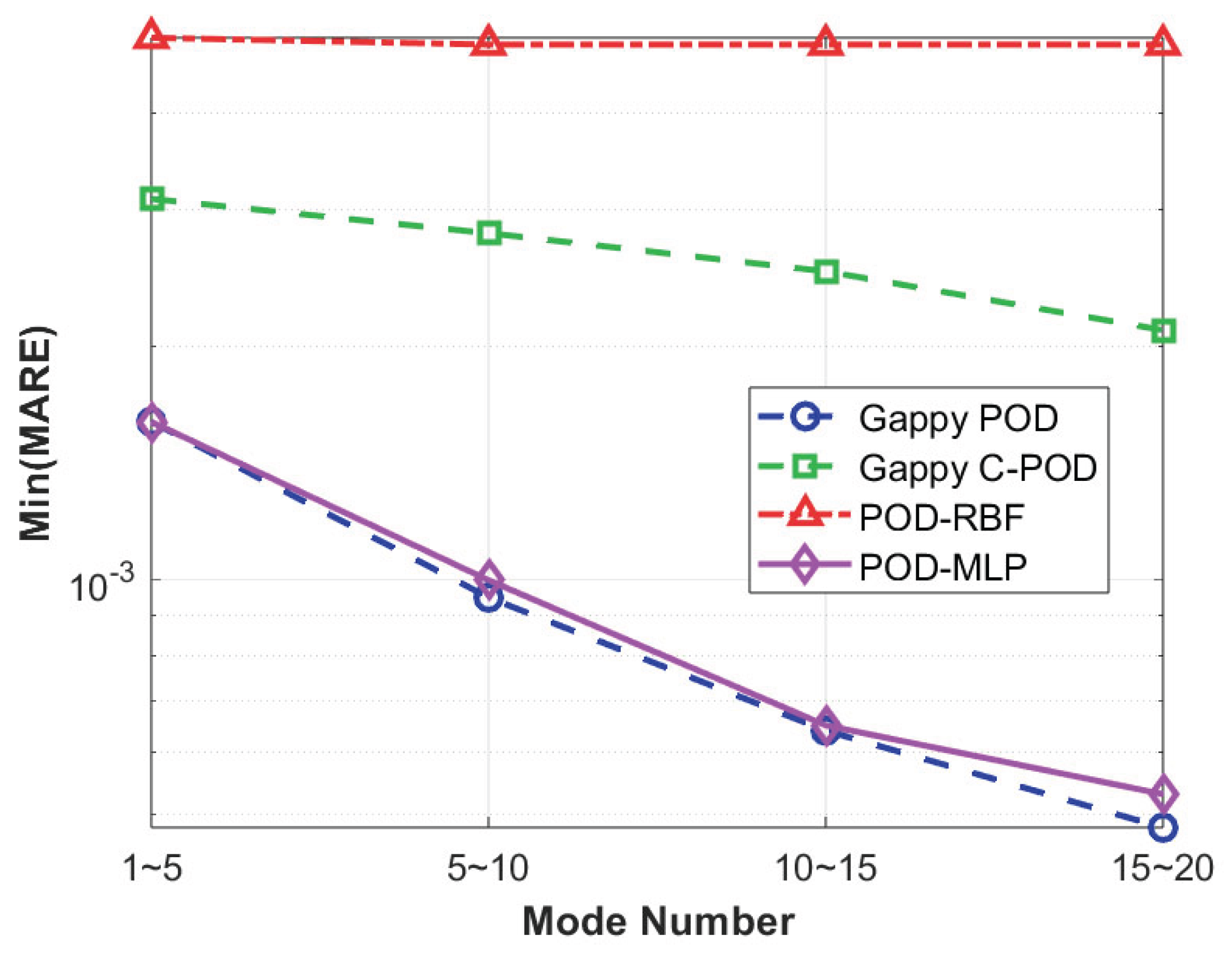

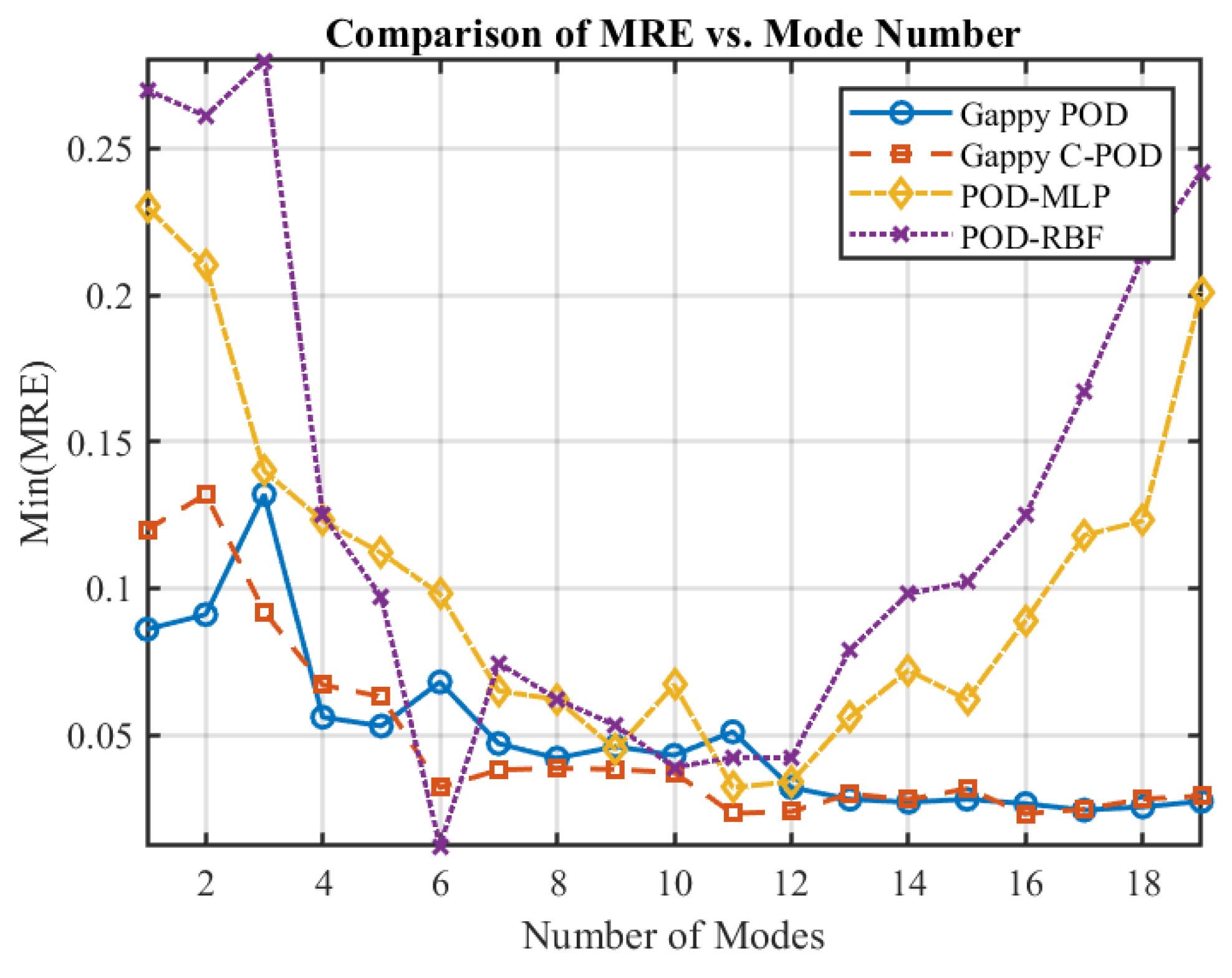

3.6. Analysis of Optimal Reconstruction Approaches for Different Modal Counts

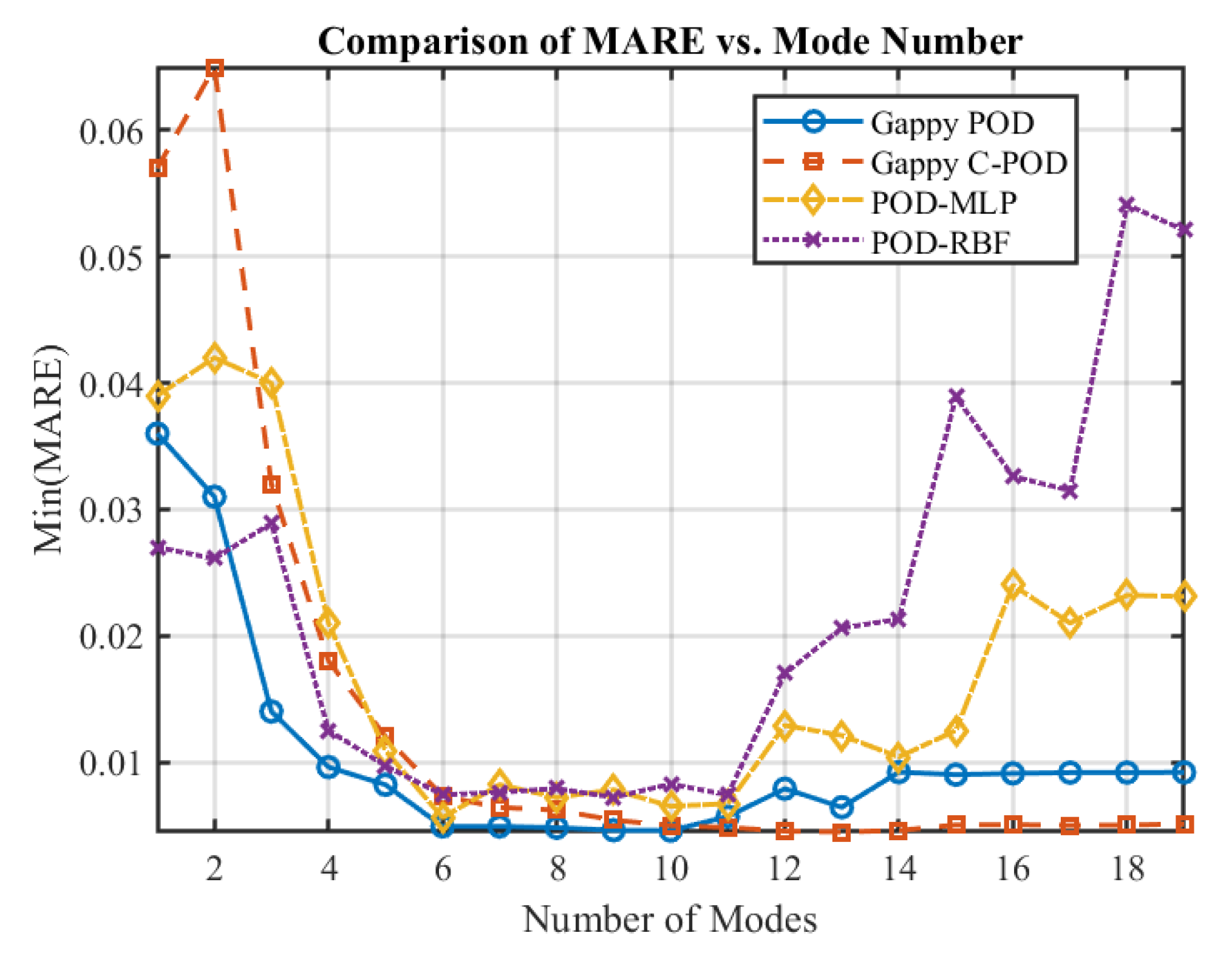

To analyze the performance variations of different reconstruction methods within varying modal ranges, this study collects data on the minimum maximum relative error (Min(MRE)) and minimum average relative error (Min(MARE)) for modes ranging from 1 to 5, 5 to 10, 10 to 15, and 15 to 20. A smaller Min(MRE) indicates a superior capability of the reconstruction scheme in limiting reconstruction deviation within the corresponding mode range (i.e., higher stability), while a smaller Min(MARE) reflects greater overall reconstruction accuracy. The results indicate that the Min(MRE) for all methods does not decrease with an increase in modal count. Notably, at the 15th modal count, all methods achieved the strongest capacity for limiting reconstruction deviation.

Table 2 presents the optimal implementation paths and corresponding error values for each reconstruction method when reaching Min(MRE) within the 15-mode range. It is evident from the table that the approach Gappy C-POD_Maximum_50_CCFM_49 demonstrates the most effective deviation control, suggesting that this scheme is less prone to significant errors during the reconstruction process.

Further observations reveal that under the condition of achieving minimal reconstruction error, the optimal point selection strategy employed by all reconstruction methods is the Correlation Coefficient Filtering Method (CCFM). An analysis combining

Figure 1 and

Figure 3 suggests that the CCFM method exhibits a higher concentration of selected points in the heat source distribution area, thereby enhancing its ability to capture critical physical features and improving overall reconstruction quality. Additionally, in scenarios with a limited number of modes, the POD-MLP method effectively suppresses deviations even when relying on a small-scale database (20 times the number of independent variables) and a minimal number of sensor points (9). This finding further indicates that utilizing Maximum distance sampling and Sobol sequence sampling for database construction under these conditions yields superior results.

Figure 4 illustrates the distribution of absolute reconstruction errors across various methods on the validation set when the Gappy C-POD_Maximum_50_CCFM_49 approach achieves Min(MRE). It is evident from the figure that the maximum reconstruction error of the Gappy C-POD method is less than 0.72°C, significantly outperforming the other three reconstruction methods, thereby reaffirming its superiority in low-order modes.

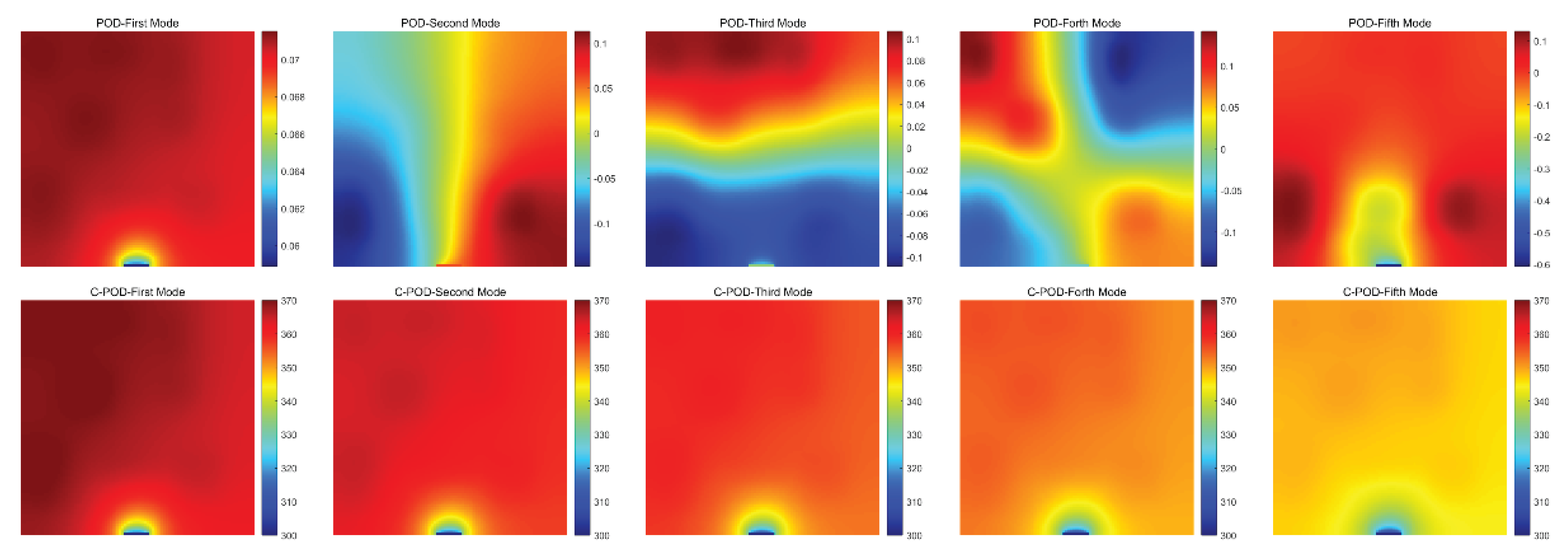

The temperature field modes obtained through the dimensionality reduction techniques of POD and C-POD are illustrated in

Figure 5. This figure displays the characteristic modal structures extracted from temperature field samples using both POD and C-POD methodologies. The upper section of the figure presents the first to nth modes extracted via the POD approach, while the lower section showcases the corresponding clustered modes generated by the C-POD method.

From the observations in

Figure 5, the following conclusions can be drawn:

(1) The POD modes (upper section) exhibit commendable spatial smoothness and energy concentration, with the lower-order modes primarily reflecting the temperature gradient variations aligned with the main direction of the heat sources, thereby encapsulating the overall characteristics of the temperature field. In contrast, the higher-order modes contain more detailed local perturbation information, although their physical interpretability is comparatively limited;

(2) The C-POD modes (lower section) display a greater complexity in spatial structure, highlighting pronounced local features that enable precise focus on areas of intense heat source concentration or significant temperature fluctuations. Particularly under complex boundary conditions or irregular heat source distributions, the C-POD modes demonstrate enhanced regional adaptability, with modal shapes more closely resembling the nonlinear distribution of actual physical fields.

From the perspective of modal structural characteristics, the POD approach is more effective for extracting dominant global features, benefitting from strong mathematical orthogonality and energy spectral decay properties. Conversely, the C-POD modes exhibit superior capabilities in local feature extraction and nonlinear pattern recognition. This distinction is further corroborated in subsequent comparative analyses, which indicate that under conditions of low modal counts, the C-POD method significantly outperforms traditional POD in terms of reconstruction error management and stability, making it particularly suited for the reconstruction of non-uniform temperature fields in scenarios with sparse sensor configurations.

The trend of Min(MARE) values for different reconstruction methods, as the number of modes increases, is illustrated in

Figure 6. It is evident from this figure that the Min(MARE) values decrease progressively with an increasing number of modes. The overall reconstruction accuracy can be ranked from lowest to highest as follows: POD-RBF, Gappy C-POD, POD-MLP, and Gappy POD. Notably, both the Gappy POD and POD-MLP methods demonstrate superior overall reconstruction accuracy.

Table 3 summarizes the pathways through which the various methods achieve their Min(MARE) values when the number of modes is between 15 and 20. According to the table, the Gappy POD_Maximum_50_Uniform_9 approach attains the optimal overall reconstruction accuracy. However, it is important to note that the datasets for the Gappy POD, POD-RBF, and POD-MLP methods are considerably larger, each reaching a scale of 50 times the number of independent variables. In contrast, the Gappy C-POD method achieves high precision in field reconstruction with a dataset only five times the size of the independent variables and relies on 25 sparse sensors, making it more suitable for engineering applications. Furthermore, while the machine-learning-based POD-MLP and POD-RBF methods show potential in terms of accuracy, their performance is heavily reliant on the quality and size of the dataset. The stability and generalization capabilities of these models still require further validation in scenarios with limited samples.

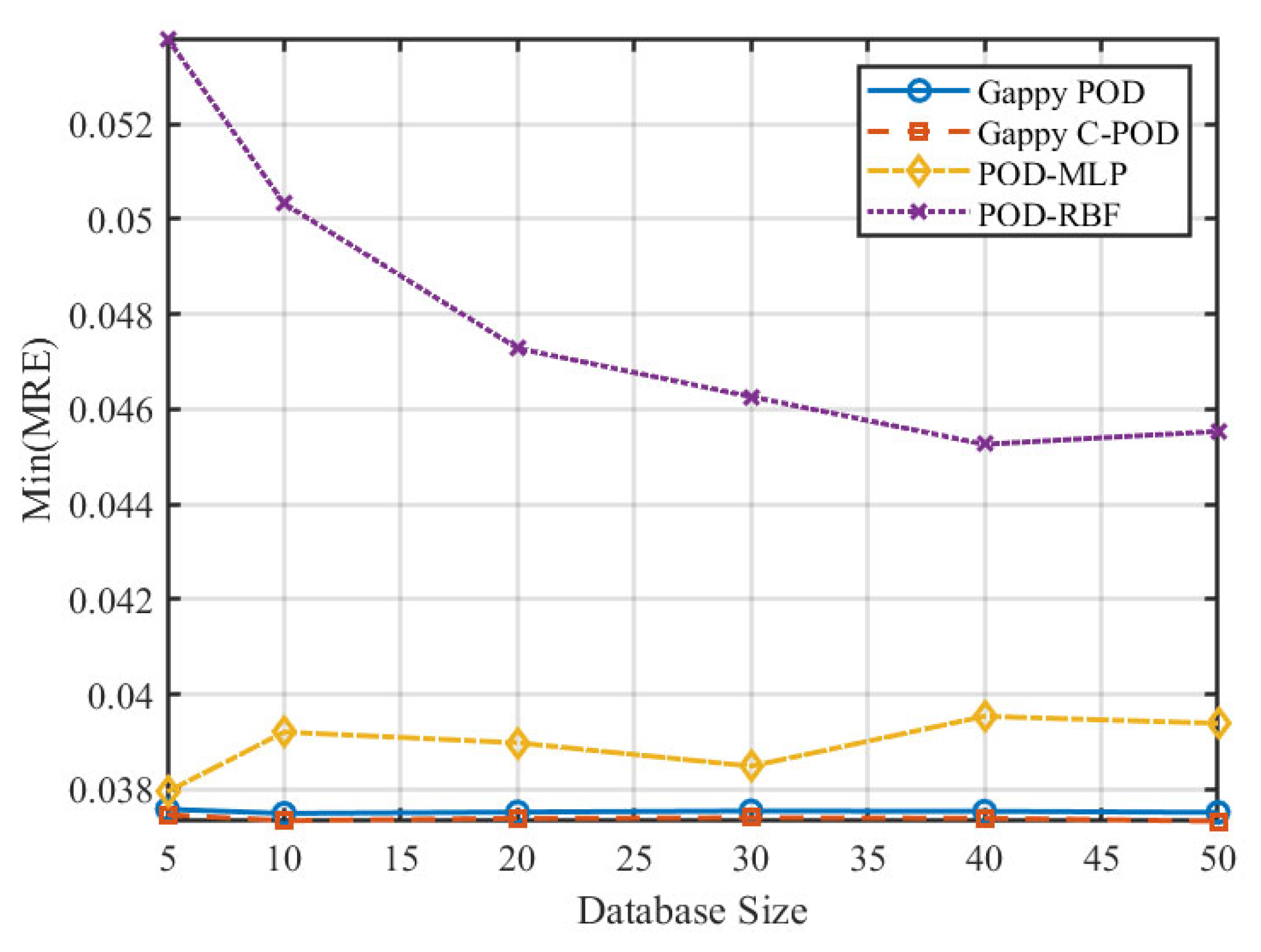

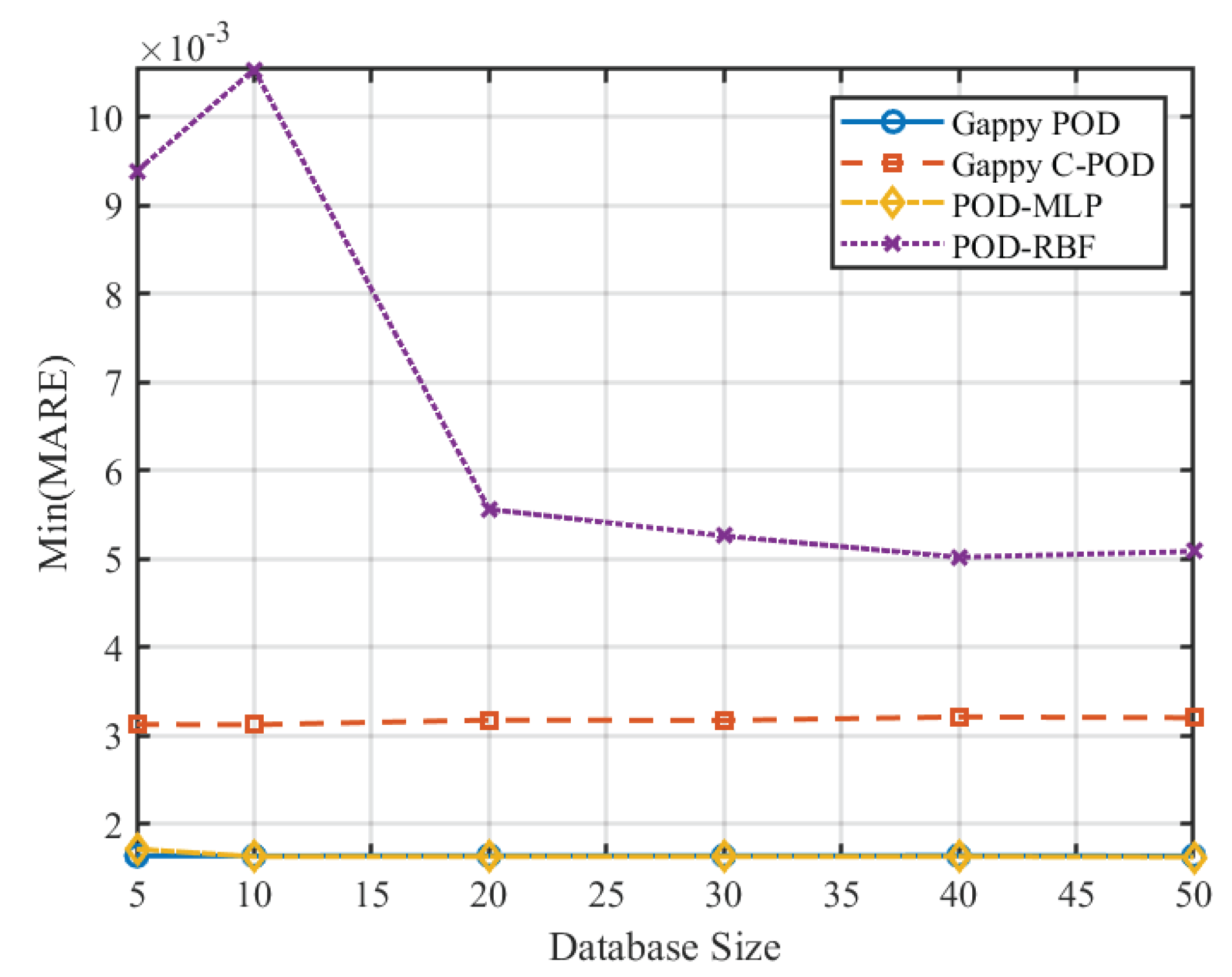

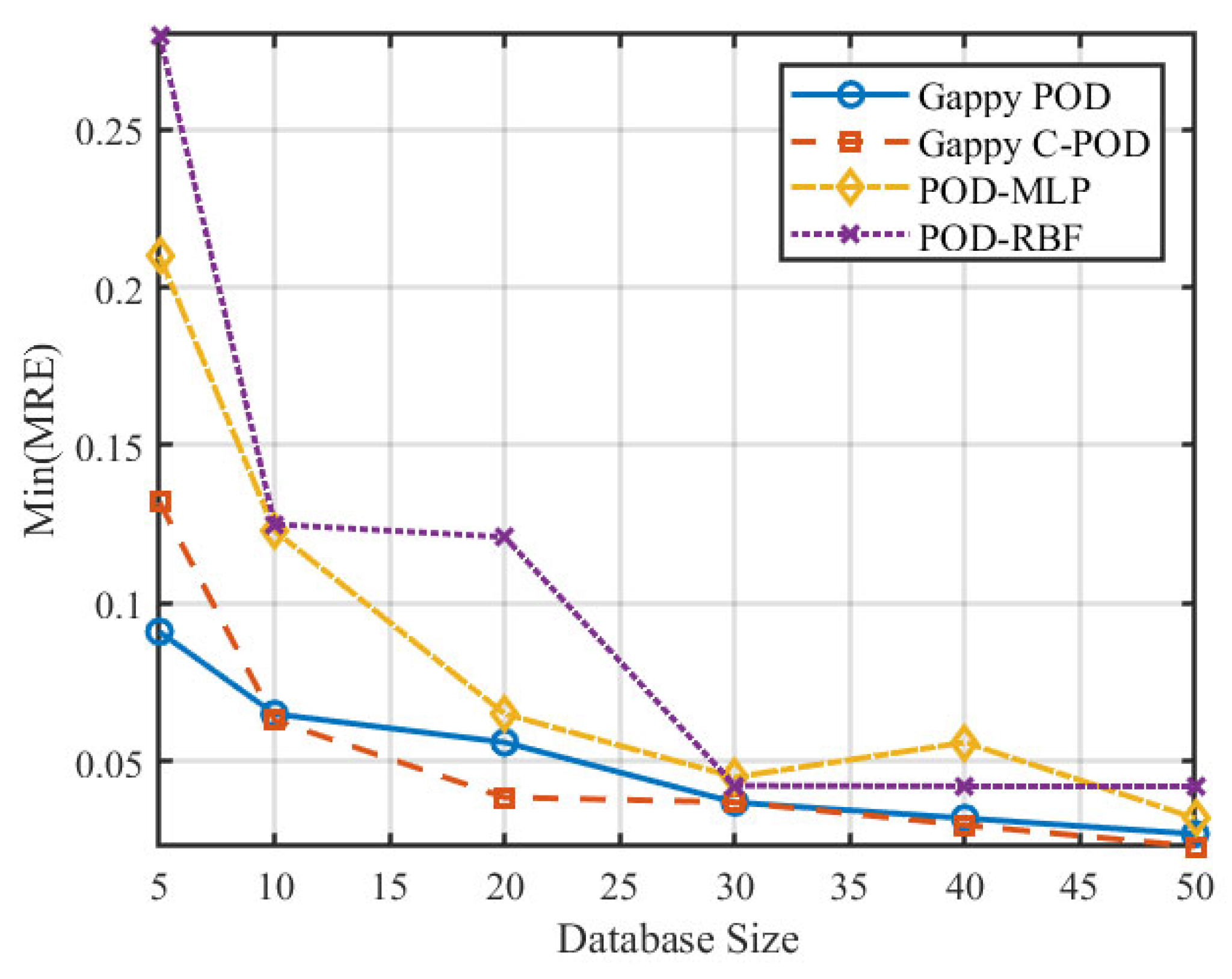

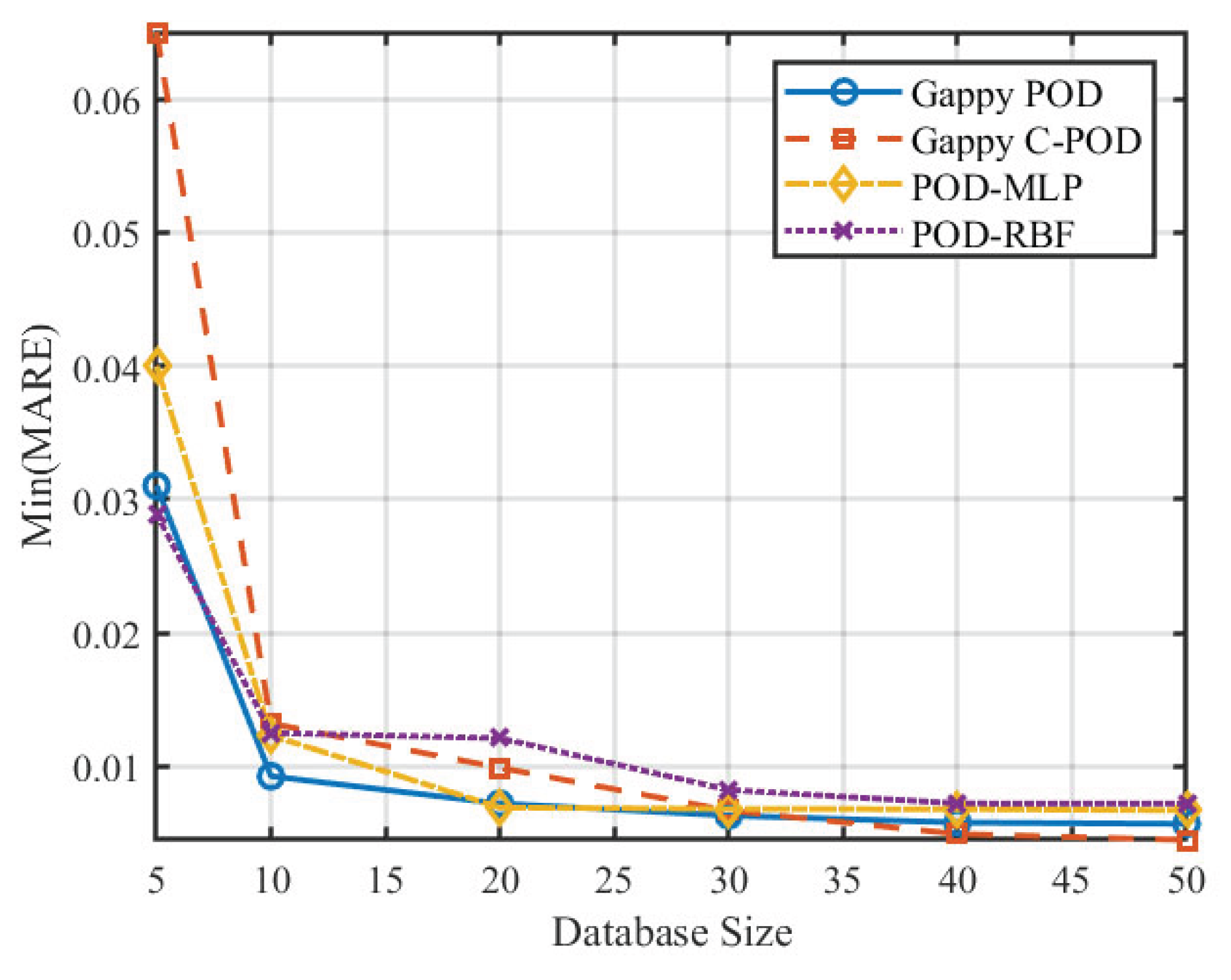

3.7. Analysis of the Impact of Database Size on the Reconstruction Capability of the Temperature Field Inverse Problem

This section investigates the effect of database size on the performance of inverse problem reconstruction by treating "database size" as the sole independent variable. Under varying sample sizes, a comprehensive consideration is given to all modal truncation numbers, diverse sparse sensor layout strategies (including Gappy POD, Gappy C-POD, POD-MLP, and POD-RBF), as well as multiple configurations of selected point quantities. The optimal combination for each database size will be identified to represent its superior reconstruction capability.

Figure 7 and

Figure 8 illustrate the variations of the minimum Mean Relative Error (Min MRE) and the minimum Mean Absolute Relative Error (Min MARE) across different database sizes. The data reveal a significant trend of performance enhancement among various reconstruction methods with optimal configurations as the database size increases. Notably, the POD-RBF method demonstrates a remarkable improvement, with its optimal MARE decreasing from 0.00939 at 50 samples to 0.00508 at 500 samples, underscoring the strong dependence of the RBF kernel function model on sample density. Conversely, both Gappy POD and Gappy C-POD reach a performance plateau within a relatively moderate database size range of approximately 200 to 300 samples, indicating efficient data utilisation. The POD-MLP method, constrained by its requirements for network parameter convergence, exhibits instability under smaller sample sizes but tends to stabilise when the sample size increases to 500.

6. Conclusions

This study addresses the precise reconstruction requirements of temperature field inverse problems in two-dimensional steady-state and transient heat conduction scenarios. A systematic investigation was conducted into various data-driven field reconstruction methods, evaluating their applicability and performance across different database sizes, modal truncation numbers, and sparse sensor layout strategies. The primary conclusions are as follows:

For steady-state heat conduction problems:

(1) In low modal conditions (1-5 modes), all reconstruction methods demonstrated a strong capability for constrained reconstruction deviation. Notably, the Gappy C-POD method, when combined with the CCFM point selection strategy and maximum distance sampling approach, attained the minimum maximum relative error (Min(MRE) = 0.0373) with a configuration of 49 sensors, displaying optimal reconstruction stability.

(2) Under high modal conditions (15-20 modes), the Gappy POD method achieved the lowest mean relative error (Min(MARE) = 0.00048) with a uniform layout and a sample size of 50 times, illustrating excellent overall reconstruction accuracy.

(3) Considering reconstruction error, data utilisation efficiency, and deployment complexity, the Gappy C-POD method achieves a performance plateau with medium database sizes (200-300 cases), making it particularly suitable for engineering applications. Although the POD-MLP method shows significant potential for overall accuracy, it is sensitive to the quality and size of the database, thus more suited to scenarios with abundant data and nonlinear modelling requirements.

For transient heat conduction problems:

(1) The accuracy and stability of various reconstruction methods exhibit significant variability with changes in modal truncation numbers. The Gappy POD and Gappy C-POD methods achieve rapid and stable convergence within the modal range of 6-11, showcasing greater robustness. In contrast, the POD-RBF and POD-MLP methods experience marked performance fluctuations, making them less adaptable to low or high modal conditions.

(2) The scale of the dataset has a pronounced impact on reconstruction performance. Beyond 30 times the number of independent variables, improvements in reconstruction accuracy tend to plateau. Under this condition, the Gappy C-POD method, in conjunction with CCFM point selection and 16 sensors, achieves the minimum maximum error (Min(MRE) = 0.0371), while also attaining the minimum mean error (Min(MARE) = 0.00456) with just 9 sensors.

(3) Compared to steady-state problems, transient issues exhibit heightened sensitivity of methods to data density and modal truncation. When selecting modal numbers and sample sizes, a careful balance between computational cost and model accuracy is recommended.

(4) The POD-RBF method can achieve moderate accuracy under conditions of ample samples and reasonable sensor layout, although its overall stability remains inferior to Gappy methods. Conversely, the POD-MLP method shows some adaptability with smaller sensor configurations, making it suited for rapid prediction needs in resource-constrained scenarios.

In summary, the Gappy C-POD method stands out for its excellent error constraint capabilities and robustness in both steady-state and transient heat conduction problems, making it an optimal choice for solving temperature field inverse problems in engineering applications. The Gappy POD method excels in high-accuracy reconstruction tasks, particularly where stringent overall accuracy requirements are essential. Machine learning-based methods can serve as supplementary strategies, particularly applicable in data-rich environments that demand rapid iterative predictions.

Figure 1.

Two-dimensional steady-state heat conduction problem.

Figure 1.

Two-dimensional steady-state heat conduction problem.

Figure 3.

Layouts of four types of sparse sensors: (a) Random point selection; (b) S-OPT method; (c) CCFM method; (d) Uniform point selection.

Figure 3.

Layouts of four types of sparse sensors: (a) Random point selection; (b) S-OPT method; (c) CCFM method; (d) Uniform point selection.

Figure 4.

Distribution of reconstruction errors for each method on the validation set.

Figure 4.

Distribution of reconstruction errors for each method on the validation set.

Figure 5.

POD and C-POD reduced-order modes of each order.

Figure 5.

POD and C-POD reduced-order modes of each order.

Figure 6.

Variation of the minimum mean absolute relative error (MARE) values corresponding to different numbers of modalities.

Figure 6.

Variation of the minimum mean absolute relative error (MARE) values corresponding to different numbers of modalities.

Figure 7.

Variation of Min(MRE) for four reconstruction methods under different database scale conditions.

Figure 7.

Variation of Min(MRE) for four reconstruction methods under different database scale conditions.

Figure 8.

Variation of Min(MARE) for four reconstruction methods under different database scale conditions.

Figure 8.

Variation of Min(MARE) for four reconstruction methods under different database scale conditions.

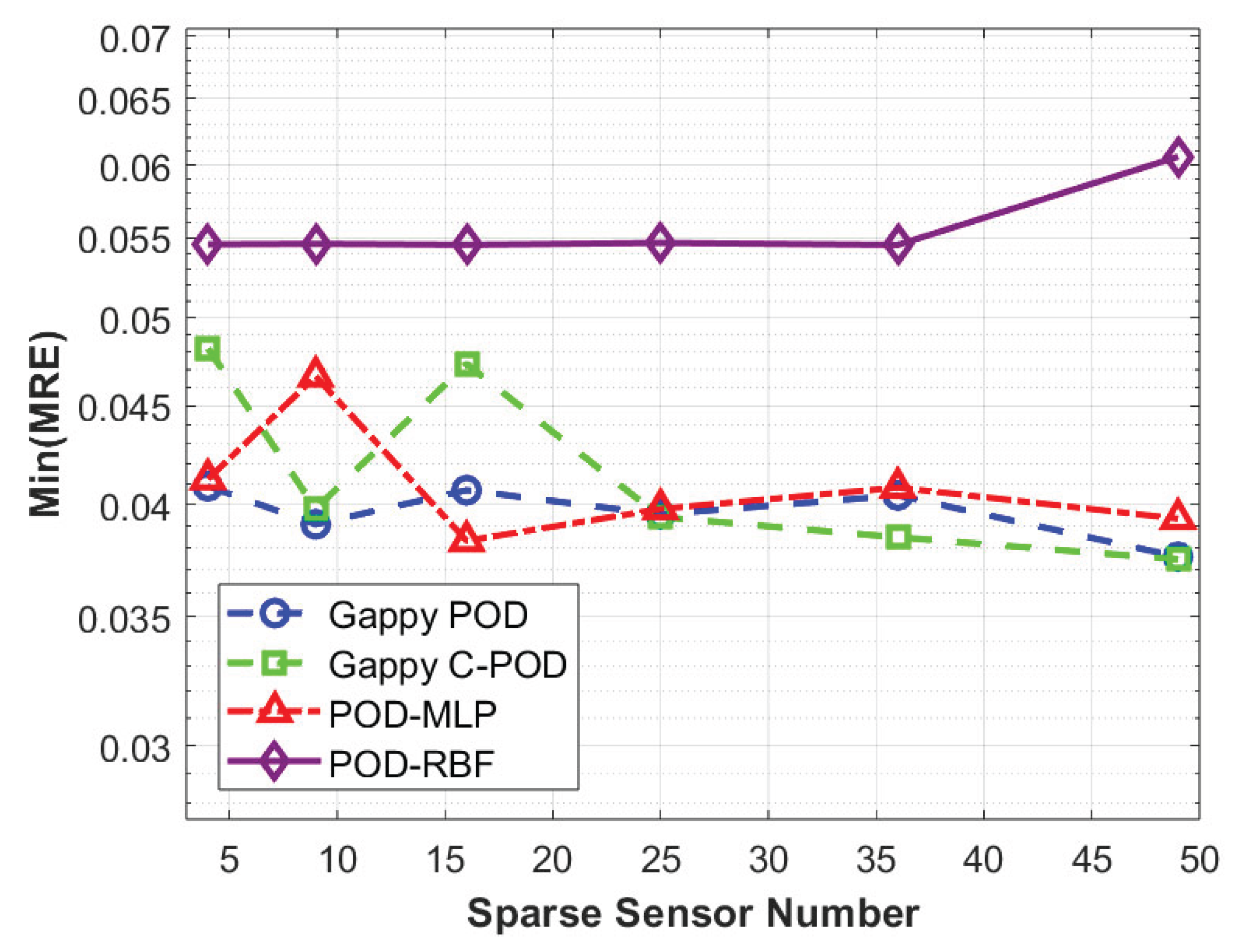

Figure 9.

Variation of Min(MRE) values with the number of sensors under four reconstruction methods.

Figure 9.

Variation of Min(MRE) values with the number of sensors under four reconstruction methods.

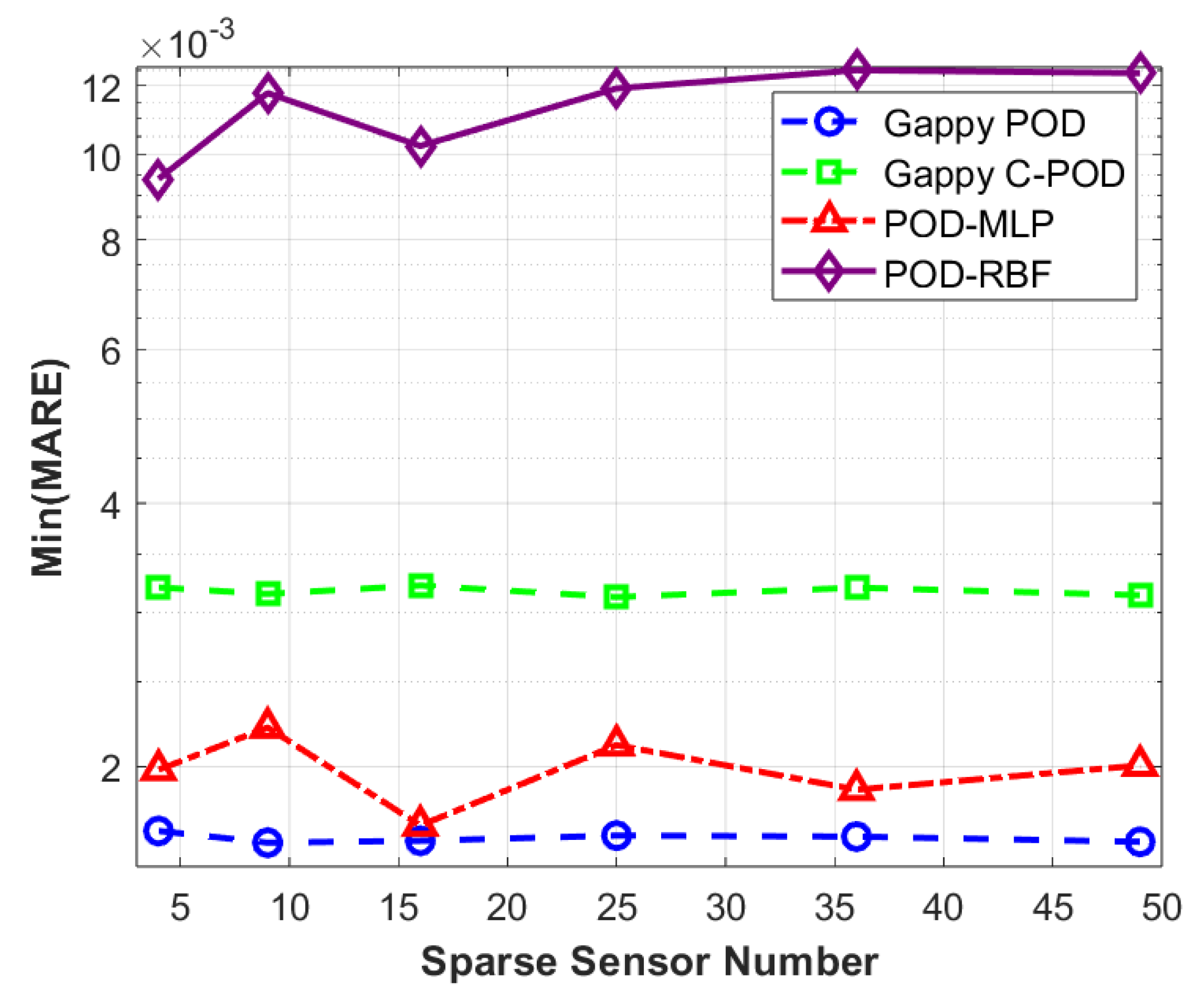

Figure 10.

Variation of Min(MARE) values with the number of sensors under four reconstruction methods.

Figure 10.

Variation of Min(MARE) values with the number of sensors under four reconstruction methods.

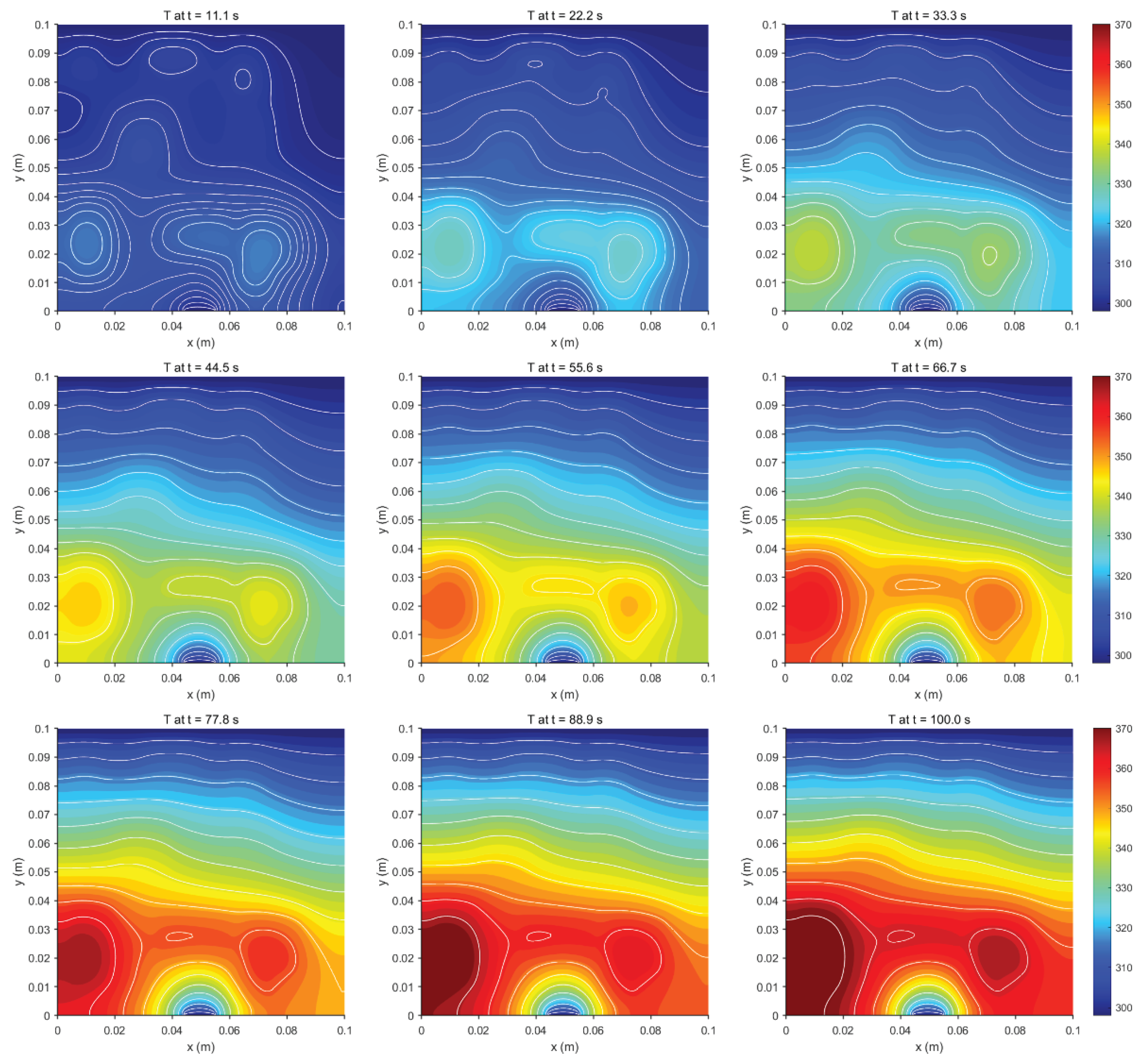

Figure 11.

Schematic diagram of the evolution of the transient thermal conductivity temperature field distribution.

Figure 11.

Schematic diagram of the evolution of the transient thermal conductivity temperature field distribution.

Figure 12.

The Min(MRE) values achievable by various reconstruction methods under different conditions of sparse sensor quantities.

Figure 12.

The Min(MRE) values achievable by various reconstruction methods under different conditions of sparse sensor quantities.

Figure 13.

The Min(MARE) values achievable by various reconstruction methods under different conditions of sparse sensor quantities.

Figure 13.

The Min(MARE) values achievable by various reconstruction methods under different conditions of sparse sensor quantities.

Figure 14.

Variation of Min(MRE) values for different reconstruction methods under different dataset scale conditions.

Figure 14.

Variation of Min(MRE) values for different reconstruction methods under different dataset scale conditions.

Figure 15.

Variation of Min(MARE) values for different reconstruction methods under different dataset scale conditions.

Figure 15.

Variation of Min(MARE) values for different reconstruction methods under different dataset scale conditions.

Table 1.

Properties and intensity parameters of heat sources.

Table 1.

Properties and intensity parameters of heat sources.

| Heat source identification number |

Starting position |

Dimensions |

Intensity

ϕ (W/m²)

|

| 1 |

(0.005, 0.005) |

(0.010, 0.015) |

0.5×10⁵~2.0×10⁵ |

| 2 |

(0.030, 0.005) |

(0.020, 0.010) |

| 3 |

(0.060, 0.005) |

(0.012, 0.020) |

| 4 |

(0.020, 0.030) |

(0.020, 0.020) |

| 5 |

(0.060, 0.030) |

(0.015, 0.015) |

| 6 |

(0.005, 0.060) |

(0.015, 0.030) |

| 7 |

(0.035, 0.065) |

(0.025, 0.015) |

| 8 |

(0.065, 0.065) |

(0.020, 0.020) |

| 9 |

(0.025, 0.085) |

(0.020, 0.010) |

| 10 |

(0.060, 0.085) |

(0.015, 0.010) |

Table 2.

Minimum MRE values achieved by various reconstruction methods under low-order modal conditions.

Table 2.

Minimum MRE values achieved by various reconstruction methods under low-order modal conditions.

| Implementation strategies |

Min(MRE) |

| Gappy POD_Maximum_10_CCFM_49 |

0.0375 |

| Gappy C-POD_Maximum_50_CCFM_49 |

0.0373 |

| POD-RBF_Sobol_50_CCFM_25 |

0.0455 |

| POD-MLP_Sobol_20_CCFM_9 |

0.039 |

Table 3.

Approaches for achieving minimum MARE values with various reconstruction methods under high-order modal conditions.

Table 3.

Approaches for achieving minimum MARE values with various reconstruction methods under high-order modal conditions.

| Implementation strategies |

Min(MARE) |

| Gappy POD_Maximum_50_Uniform_9 |

0.00048 |

| Gappy C-POD_Maximum_5_CCFM_25 |

0.0021 |

| POD-RBF_Sobol_50_CCFM_25 |

0.0049 |

| POD-MLP_Maximum_50_SOPT_49 |

0.00053 |

Table 4.

Changes in Min(MRE) and Min(MARE) values with varying numbers of sparse sensors.

Table 4.

Changes in Min(MRE) and Min(MARE) values with varying numbers of sparse sensors.

| Number of Sparse Sensors |

Gappy POD |

|

Gappy C-POD |

|

POD-MLP |

|

POD-RBF |

| Min(MRE) |

Min(MARE) |

|

Min(MRE) |

Min(MARE) |

|

Min(MRE) |

Min(MARE) |

|

Min(MRE) |

Min(MARE) |

| 4 |

0.0408 |

0.0016 |

|

0.0482 |

0.0032 |

|

0.0412 |

0.0019 |

|

0.0545 |

0.0093 |

| 9 |

0.0390 |

0.0016 |

|

0.0398 |

0.0031 |

|

0.0466 |

0.0022 |

|

0.0546 |

0.0117 |

| 16 |

0.0406 |

0.0016 |

|

0.0473 |

0.0032 |

|

0.0383 |

0.0017 |

|

0.0545 |

0.0102 |

| 25 |

0.0395 |

0.0016 |

|

0.0394 |

0.0031 |

|

0.0397 |

0.0021 |

|

0.0546 |

0.0119 |

| 36 |

0.0404 |

0.0016 |

|

0.0384 |

0.0032 |

|

0.040 |

0.0018 |

|

0.0545 |

0.0125 |

| 49 |

0.0375 |

0.0016 |

|

0.0374 |

0.0031 |

|

0.039 |

0.0020 |

|

0.0606 |

0.0124 |

Table 5.

Sampling methods and layout methods used by each approach when achieving Min(MRE) under different sensor quantity conditions.

Table 5.

Sampling methods and layout methods used by each approach when achieving Min(MRE) under different sensor quantity conditions.

| Number of sparse sensors |

Gappy POD |

|

Gappy C-POD |

|

POD-MLP |

|

POD-RBF |

| Sampling method |

Layout method |

|

Sampling method |

Layout method |

|

Sampling method |

Layout method |

|

Sampling method |

Layout method |

| 4 |

Sobol |

Uniform |

|

Latin |

CCFM |

|

Latin |

CCFM |

|

Latin |

SOPT |

| 9 |

Latin |

SOPT |

|

Sobol |

SOPT |

|

Sobol |

Uniform |

|

Latin |

CCFM |

| 16 |

Sobol |

SOPT |

|

Latin |

CCFM |

|

Latin |

Uniform |

|

Maximum |

CCFM |

| 25 |

Latin |

SOPT |

|

Latin |

SOPT |

|

Maximum |

Uniform |

|

Latin |

CCFM |

| 36 |

Sobol |

Uniform |

|

Latin |

CCFM |

|

Maximum |

Uniform |

|

Latin |

SOPT |

| 49 |

Latin |

CCFM |

|

Latin |

CCFM |

|

Sobol |

SOPT |

|

Latin |

CCFM |

Table 6.

Sampling methods and layout methods used by each approach when achieving Min(MARE) under different sensor quantity conditions.

Table 6.

Sampling methods and layout methods used by each approach when achieving Min(MARE) under different sensor quantity conditions.

| Number of sparse sensors |

Gappy POD |

|

Gappy C-POD |

|

POD-MLP |

|

POD-RBF |

| Sampling method |

Layout method |

|

Sampling method |

Layout method |

|

Sampling method |

Layout method |

|

Sampling method |

Layout method |

| 4 |

Maximum |

SOPT |

|

Sobol |

SOPT |

|

Maximum |

SOPT |

|

Maximum |

CCFM |

| 9 |

Sobol |

Uniform |

|

Sobol |

Uniform |

|

Sobol |

Uniform |

|

Latin |

CCFM |

| 16 |

Sobol |

Uniform |

|

Sobol |

Uniform |

|

Maximum |

SOPT |

|

Sobol |

CCFM |

| 25 |

Maximum |

Random |

|

Sobol |

Uniform |

|

Maximum |

SOPT |

|

Latin |

CCFM |

| 36 |

Sobol |

Uniform |

|

Sobol |

Uniform |

|

Sobol |

SOPT |

|

Sobol |

CCFM |

| 49 |

Sobol |

Uniform |

|

Sobol |

Uniform |

|

Sobol |

SOPT |

|

Latin |

CCFM |

Table 8.

Achieving Min(MRE) under different reconstruction methods, point selection methods, and point selection quantities.

Table 8.

Achieving Min(MRE) under different reconstruction methods, point selection methods, and point selection quantities.

| Reconstruction methods |

Selection method |

Number |

Min(MRE) |

| Gappy POD |

S-OPT |

16 |

0.0462 |

| Gappy C-POD |

CCFM |

16 |

0.0371 |

| POD-MLP |

Uniform |

9 |

0.0487 |

| POD-RBF |

CCFM |

9 |

0.0561 |

Table 9.

Achieving Min(MARE) under different reconstruction methods, point selection methods, and point quantity conditions.

Table 9.

Achieving Min(MARE) under different reconstruction methods, point selection methods, and point quantity conditions.

| Reconstruction methods |

Selection method |

Number |

Min(MRE) |

| Gappy POD |

S-OPT |

9 |

0.00462 |

| Gappy C-POD |

CCFM |

9 |

0.00456 |

| POD-MLP |

S-OPT |

4 |

0.00726 |

| POD-RBF |

CCFM |

4 |

0.00823 |