1. Introduction

The application of blockchain technology in Enhanced Oil Recovery (EOR) processes has gained increasing attention in recent years, particularly in contexts where traceability, security, and trust between stakeholders are crucial. EOR techniques—such as CO2 injection, water flooding, and chemical injection—require accurate, real-time monitoring of subsurface dynamics and fluid flows to ensure technical efficiency and environmental compliance (Chen et al., 2024). However, traditional data management systems in EOR operations often suffer from fragmentation, limited interoperability, and vulnerability to manipulation or loss of critical records (Mohammadian et al., 2024). This limitation is particularly critical in offshore regions where the complexity of operations, remoteness of assets, and high safety standards require secure and reliable information infrastructures (Nassabeh et al., 2024). In this regard, blockchain-based architecture offers a decentralized and immutable framework to store and validate operational data, support compliance with Monitoring, Reporting, and Verification (MRV) protocols, and enhance automation through smart contracts (Woo et al., 2021a).

In Colombia, the Guajira Offshore basin has emerged as a strategic zone for energy development and decarbonization efforts, with a growing interest in leveraging its geological formations for CO2-EOR and potential storage (Suárez Bermúdez et al., 2025). The complex structural evolution of this basin, influenced by Caribbean and South American plate interactions, makes it a suitable candidate for deep injection and multiphase flow control, but also introduces high uncertainty in reservoir behavior (Rodríguez et al., 2021a). Despite this potential, the digital and operational infrastructure in the Guajira Offshore remains limited, hindering the implementation of advanced monitoring systems and real-time data integration across stakeholders. Moreover, current MRV processes in the Colombian oil and gas sector are often fragmented and rely on centralized databases with limited transparency, which affects the credibility of emission reports and injection traceability (Pourrahmani et al., 2025). These challenges underscore the need for a secure, decentralized, and intelligent framework capable of enhancing trust, interoperability, and real-time analytics in EOR operations within this sensitive marine ecosystem.

Internationally, efforts have been made to integrate blockchain into EOR workflows to improve data integrity, decision-making agility, and regulatory compliance across multiple jurisdictions. In countries such as China, the UAE, and Norway, hybrid architectures combining blockchain with digital twins, distributed sensors, and AI have been tested for offshore CO2 injection and hydrocarbon recovery operations (Chang et al., 2024; Sadri, 2025). These approaches enable immutable recording of pressure, temperature, and injected volumes, facilitating real-time auditing and event traceability via auto-executing smart contracts (Khattak et al., 2020). Offshore companies in the North Sea and the Persian Gulf have experimented with blockchain-IoT systems to manage multi-phase EOR workflows, including hydraulic fracturing and geo-chemical modeling (Fakhar et al., 2024; Pham & Halland, 2017). Integration with MRV standards such as ISO 14064 and IPCC guidelines has been achieved through authorized blockchain nodes validating events against pre-established protocols (Woo et al., 2021b). However, these solutions remain concentrated in digitally mature environments, limiting their applicability in under-connected regions like Latin America. Technical gaps remain in terms of data governance, cryptographic robustness under marine conditions, and energy efficiency of distributed consensus protocols (Valluri & Sharma, 2024).

Recent advances in the field have proposed frameworks where blockchain interacts with federated learning and edge computing systems to enable privacy-preserving monitoring in EOR operations (Parekh et al., 2025). These models train predictive algorithms locally on devices deployed in floating units or coastal stations, sharing only aggregated parameters on the blockchain for decentralized validation (S. Kumar & Barua, 2023; Umran et al., 2023). Sustainability-focused studies have explored the use of energy-efficient consensus algorithms—such as Proof of Authority or customized Byzantine Fault Tolerance—to reduce energy consumption in remote marine deployments (Parekh et al., 2025). Performance metrics evaluated include latency in data transmission, detection accuracy of injection anomalies, and fraud mitigation in CO2 injection reports (Davoodi et al., 2024; Woo et al., 2021a). These developments provide a valuable reference for adapting blockchain-enhanced architectures to underdeveloped contexts like the Guajira Offshore basin, where reliable, low-impact, and auditable systems are urgently needed.

Despite these global advancements, several knowledge gaps persist when it comes to applying blockchain technology in offshore EOR systems in underconnected or developing regions. First, literature lacks a comprehensive framework tailored to the specific operational, regulatory, and infrastructural conditions of offshore basins like Guajira. Second, there is insufficient integration between blockchain and MRV protocols for CO2 injection in tropical marine environments, where ecosystem fragility demands high transparency and traceability. Third, existing systems rarely consider the use of smart contracts for dynamic risk assessment and alert generation based on sensor data anomalies, which are crucial for preventing failures in injection or storage operations (Mahjour & Faroughi, 2023). Furthermore, decision-support platforms that incorporate distributed data consensus, machine learning insights, and secure audit trails for regulators and operators are still in nascent stages (Mao et al., 2022). These limitations point to an urgent need for applied research that bridges the technological and contextual divide in blockchain-enhanced EOR systems.

In light of these challenges, the present working paper (WP) seeks to address the following research question: How can blockchain-based architectures be designed and implemented to enhance traceability, data security, and operational efficiency in CO2-enhanced oil recovery operations in the Guajira Offshore basin, considering local technological constraints and regulatory requirements? To respond to this question, we propose a modular framework that integrates blockchain with artificial intelligence, digital sensors, and smart contracts for real-time MRV in offshore environments. Accordingly, this WP has three main objectives: (i) to model a decentralized digital traceability system for EOR operations in Guajira Offshore; (ii) to validate its functionality through realistic simulations of data flows and interactions among actors (operators, verifiers, regulators); and (iii) to assess its potential impact on monitoring efficiency, transaction costs, and operational transparency. This approach contributes to the global discussion on blockchain’s role in the energy transition and enables Colombia to position itself as a regional leader in climate-related traceability innovation.

This WP is structured as follows:

Section 2 provides a literature review of blockchain applications in EOR and MRV systems, with emphasis on offshore contexts.

Section 3 presents the methodology adopted for the conceptual and technical design of the proposed architecture.

Section 4 introduces the main results and system components, including use cases and operational workflows tailored to the Guajira Offshore basin.

Section 5 discusses the potential benefits, risks, and limitations of the proposed solution. Finally,

Section 6 outlines the conclusions and future research directions necessary to scale and validate the model in real-world conditions.

2. Literature review

The convergence of blockchain technology with Enhanced Oil Recovery (EOR) processes has emerged as a novel interdisciplinary frontier, especially in response to increasing demands for operational transparency, data security, and regulatory compliance in carbon-intensive industries. Recent technological advancements in digitalization, automation, and data-driven analytics have laid the foundation for integrating decentralized architectures into critical energy infrastructures (N. Kumar et al., 2025; R. L. Kumar et al., 2022). This section presents a comprehensive review of the literature on the intersection of blockchain, CO2-based EOR operations, MRV systems, and digital innovations relevant to offshore applications.

While EOR technologies have been widely studied from the perspectives of fluid mechanics, reservoir simulation, and carbon utilization, relatively few works have explored the implications of integrating blockchain and distributed ledger technologies into the operational, logistical, and regulatory dimensions of EOR (Yang et al., 2024). Moreover, the emergence of carbon capture, utilization, and storage (CCUS) as a pivotal strategy for climate mitigation has shifted focus toward verifiable and auditable reporting mechanisms, for which blockchain offers a robust technological substrate (Liang et al., 2024).

This literature review is structured to address five interlinked thematic areas. First, it explores the technical and environmental challenges associated with offshore EOR operations. Second, it examines the critical role of Measurement, Reporting, and Verification (MRV) systems in carbon accounting and EOR monitoring. Third, it reviews the applications of blockchain in industrial traceability and energy governance. Fourth, it analyzes the integration of blockchain with artificial intelligence (AI), digital twins, and IoT technologies to enhance decision-making and resilience in EOR. Lastly, the review highlights current gaps in knowledge, particularly in the context of Latin America and Colombia’s Guajira Offshore Basin, where infrastructure constraints and regulatory uncertainties persist (Rodríguez et al., 2021).

Through this structured approach, the review aims to synthesize existing knowledge, identify emerging trends, and reveal unresolved challenges that inform the architecture proposed in this Working Paper. The review serves as a theoretical foundation to support the research question: How can blockchain-based architectures improve the traceability, data security, and operational efficiency of offshore EOR processes in Colombia, with a specific focus on CO2 injection and MRV compliance?

2.1. Enhanced Oil Recovery (EOR) and Its Challenges in Offshore Environments

Enhanced Oil Recovery (EOR) remains a critical technique to improve the extraction efficiency of mature oil fields, particularly in offshore environments where conventional recovery yields are typically low (Arroyave et al., 2020; Bao et al., 2023). Offshore EOR operations face multiple logistical and operational barriers, including complex reservoir heterogeneity, high implementation costs, and the need for real-time monitoring under extreme environmental conditions (Li et al., 2024). CO2 injection methods—recognized for their dual benefit in enhanced recovery and carbon sequestration—pose additional technical requirements, such as continuous surveillance of injection rates, geochemical interactions, and pressure stabilization (Franco et al., 2017; Yang et al., 2024).

Several modeling frameworks have been developed to simulate CO2 injection behavior in fractured offshore reservoirs, incorporating nanoconfinement effects and advanced compositional analysis (Gao et al., 2024; Liu et al., 2025). However, these simulations often suffer from data scarcity and delayed feedback, limiting their responsiveness to unexpected operational anomalies. Additionally, offshore EOR must align with environmental regulations and carbon reduction commitments, which demand high standards in Measurement, Reporting, and Verification (MRV) systems (Davoodi et al., 2024; Mahjour & Faroughi, 2023).

Recent studies emphasize the integration of digital technologies to overcome these challenges. For example, intelligent hydrogels and smart materials have been proposed to improve injection responsiveness and conformance control in deep reservoirs (Fang et al., 2025). Furthermore, spatiotemporal models have been developed to predict EOR performance across dynamic geological contexts, aiding in real-time reservoir management (Younis et al., 2023). Yet, many of these innovations are limited to experimental or pilot scales and lack scalable mechanisms for secure data governance, especially when involving multiple operators and regulatory stakeholders.

2.2. Measurement, Reporting and Verification (MRV) Systems and CO2 Traceability

Accurate measurement, transparent reporting, and verifiable tracking of CO2 flows are central pillars of any Enhanced Oil Recovery (EOR) operation aligned with carbon management objectives. MRV systems, historically developed for regulatory compliance in emission-intensive sectors, have evolved into complex digital infrastructures capable of monitoring injection rates, storage permanence, and reservoir behavior over time (Zhang et al., 2023). In the context of offshore EOR, particularly in geologically dynamic regions such as the Guajira Basin, the need for real-time, tamper-proof, and interoperable MRV solutions is increasingly critical (Rodríguez et al., 2021).

Traditional MRV approaches rely on centralized data collection and manual validation protocols, which are vulnerable to data manipulation, system inefficiencies, and lack of interoperability across institutional boundaries (Chen et al., 2025). These limitations become particularly acute in remote offshore environments, where harsh conditions and limited infrastructure impede continuous sensor monitoring and high-fidelity data transmission (Delgado et al., 2020). In such contexts, ensuring the integrity and auditability of CO2 flow data across injection wells, storage formations, and pipeline systems remains a technological and institutional challenge.

Recent advances in blockchain-based architecture offer transformative possibilities for MRV systems. By embedding time-stamped records, distributed validation mechanisms, and immutable data ledgers, blockchain enables the creation of verifiable and transparent chains of custody for CO2 captured, transported, injected, and stored (Abdellatif et al., 2025; Ressi et al., 2024). Smart contracts, for example, can automate regulatory reporting based on predefined thresholds of CO2 injection, while oracles linked to real-time sensors ensure that off-chain measurements are securely integrated into the blockchain registry (Shinde et al., 2021).

In addition to improving trust and auditability, blockchain enhances the scalability and resilience of MRV systems. Decentralized consensus protocols mitigate the risks of single-point failure and unauthorized data alteration, which are especially problematic in complex CCUS networks spanning multiple stakeholders (Krishnaraj et al., 2025; N. Kumar et al., 2025). Furthermore, integrating blockchain with AI-driven anomaly detection systems has been shown to improve the identification of operational faults or data inconsistencies in CO2 injection profiles, increasing both the robustness and responsiveness of MRV frameworks (Jovanovic et al., 2024).

Despite these promising developments, the application of blockchain-based MRV systems in real-world EOR projects remains limited. Most pilot implementations have been confined to energy trading or supply chain transparency initiatives in the power sector, with few operational case studies in hydrocarbon recovery (Al-Rbeawi, 2023). Moreover, no known deployment of blockchain-integrated MRV systems has been reported for EOR in the Colombian offshore context, where regulatory, geological, and institutional uncertainties persist (Suárez Bermúdez et al., 2025).

This gap highlights the need for tailored architectures that account for the unique spatial, technical, and legal constraints of offshore CO2-EOR in regions like Guajira. A well-designed blockchain-enabled MRV system could not only ensure the environmental integrity of CO2 storage but also unlock new financial mechanisms such as verified carbon credits or performance-based subsidies(Al-Rbeawi, 2023; Shinde et al., 2021) (Davoodi et al., 2024; Pinedo-López et al., 2024). These benefits make MRV innovation a key enabler of sustainable, scalable, and socially accepted EOR deployments.

In this Working Paper, we argue that integrating blockchain into the MRV layer of EOR systems offers not only operational transparency but also an essential mechanism for building trust among regulators, industry actors, and local communities. The following sections explore how this digital infrastructure can be designed, validated, and deployed for pilot-scale applications in the Guajira Offshore Basin.

2.3. International Advances in Blockchain Applications for Enhanced Oil Recovery (EOR)

Over the past decade, there has been a growing global interest in leveraging blockchain technologies to enhance transparency, operational efficiency, and environmental accountability in oil and gas value chains. Within this broader digitalization trend, specific applications of blockchain in Enhanced Oil Recovery (EOR) are beginning to emerge, although still at a nascent stage compared to other sectors such as energy trading or logistics (Al-Rbeawi, 2023; Shinde et al., 2021). These initiatives typically seek to integrate blockchain with advanced sensor networks, Internet of Things (IoT) systems, and artificial intelligence (AI) tools to enable real-time monitoring and decentralized decision-making in EOR operations.

Pilot projects in North America, the Middle East, and parts of Asia have explored blockchain-based frameworks to secure and validate the performance of CO2 injection processes, streamline well operation logs, and reduce the administrative burden of regulatory compliance (Jovanovic et al., 2024; Parekh et al., 2025). For instance, blockchain-integrated supervisory systems have been proposed to register high-frequency injection parameters—such as pressure, temperature, and flow rate—into immutable ledgers that can be audited by external stakeholders, including environmental agencies and carbon credit registries (N. Kumar et al., 2025; Yang et al., 2024).

Several studies highlight the synergies between blockchain and distributed learning algorithms, especially federated learning frameworks that enable the secure sharing of EOR performance data across geographically dispersed assets (Sadri, 2025). These architectures ensure that sensitive data never leaves its point of origin while still contributing to model training for operational optimization or predictive maintenance, thus respecting both data privacy and regulatory compliance. Blockchain’s role in smart contract implementation has also gained attention in EOR systems. Automated contracts triggered by subsurface sensor readings can enable performance-based payments between oil operators and service providers, particularly for CO2 injection services or equipment leasing (Krishnaraj et al., 2025). This contractual automation reduces transactional friction and enhances accountability while promoting financial innovation in the EOR ecosystem. Moreover, tokenization of verified CO2 storage volumes has been proposed as a mechanism to link EOR activities to voluntary carbon markets, thereby monetizing environmental performance in blockchain-compatible registries (Alyousef et al., 2025).

Despite these innovations, the global adoption of blockchain in EOR remains fragmented. Technical challenges include high energy consumption of traditional blockchain consensus mechanisms, limited sensor interoperability, and the need for robust digital infrastructure in remote EOR fields (Franco et al., 2017; Yuan et al., 2024). Institutional resistance and uncertainty over legal recognition of blockchain-registered emissions data further hinder its deployment in high-stakes regulatory environments, particularly in jurisdictions with underdeveloped digital governance frameworks (Delgado et al., 2020).

Nevertheless, the momentum is building. The integration of blockchain into EOR workflows is increasingly viewed not merely as a technological upgrade, but as a foundational element of next-generation CCUS ecosystems. It offers the means to digitize and democratize access to operational data, improve inter-organizational coordination, and strengthen the credibility of CO2 storage reporting (Zeinolabedini et al., 2025; Zhang et al., 2023). These functions are particularly critical in light of emerging global standards for MRV systems under Article 6 of the Paris Agreement and voluntary market protocols.

This Working Paper builds upon these international developments and contextualizes them within the operational and regulatory particularities of the Guajira Offshore Basin. In doing so, it proposes a blockchain-based framework specifically tailored to address the traceability, security, and coordination gaps in CO2-EOR operations in Colombia.

2.4. State of the Art in Blockchain for Traceability and MRV in Energy Systems

The convergence of blockchain technologies and Monitoring, Reporting, and Verification (MRV) systems in energy domains has led to significant advancements in how data integrity, auditability, and accountability are achieved across decentralized infrastructures. In the context of climate-oriented energy transitions, particularly in systems involving carbon-intensive operations, blockchain offers the potential to overcome historical limitations of centralized MRV protocols by providing immutable, time-stamped, and interoperable records of environmental and operational data (Shinde et al., 2021; Shorya & Jagwani, 2025).

In electricity and renewable energy systems, blockchain-based traceability solutions have matured considerably. Platforms have been developed to record and verify renewable energy generation, match supply with demand in peer-to-peer trading networks, and issue digital certificates for green energy transactions (Abdellatif et al., 2025; N. Kumar et al., 2025). These systems utilize smart contracts to automatically validate energy provenance, reduce administrative complexity, and foster trust between decentralized actors. Such advances are supported by low-energy consensus algorithms (e.g., Proof of Authority, Delegated Proof of Stake) that address the energy inefficiencies of earlier blockchain iterations (Krishnaraj et al., 2025). MRV systems for carbon emissions and storage are increasingly integrating blockchain to enhance the credibility of carbon claims in voluntary and compliance markets. For example, novel architectures link sensor-based CO2 capture and injection data to blockchain ledgers that feed directly into emission inventories or carbon registries (Fang et al., 2025). These architectures are critical in preventing double-counting, ensuring temporal consistency of data, and promoting transparency in carbon offset transactions.

In the context of oil and gas, blockchain’s integration into MRV systems is still emergent but promising. Several pilot initiatives have demonstrated how blockchain can register real-time data streams from flow meters, injection sensors, and storage facilities, enabling automated verification and auditable logging of CO2-EOR activities (Cirac et al., 2025; Zhang et al., 2023). These systems not only enhance compliance with environmental regulations but also support the development of market mechanisms where verified storage volumes or emissions reductions become tradable assets. A key area of innovation involves the use of digital twins synchronized with blockchain to monitor operational deviations and detect anomalies in near real-time. These systems combine AI-based predictive analytics with decentralized ledger recording to create trustworthy digital representations of physical EOR infrastructure, thereby strengthening risk detection and integrity assessment protocols (Hussain et al., 2024; Sadri, 2025). Integration with satellite imaging, drone surveillance, and distributed IoT further enhances the granularity and reliability of MRV data, particularly in remote or offshore contexts.

Despite the technological promise, challenges persist in achieving full traceability in MRV applications. Sensor calibration, data interoperability, latency in distributed networks, and the need for standardized data ontologies are recurring limitations (Mahjour & Faroughi, 2023; Pradhan et al., 2024). Moreover, the legal and institutional frameworks required to accept blockchain-verified MRV records as regulatory evidence are still under development in many jurisdictions, particularly in Latin America. The potential of blockchain to transform MRV into energy systems lies in its capacity to establish an auditable, tamper-proof, and decentralized digital infrastructure that enables data sovereignty, facilitates stakeholder coordination, and enhances the environmental credibility of industrial operations. For countries like Colombia, and particularly for emerging CCUS regions such as the Guajira Offshore Basin, adopting these architectures offers a strategic advantage in aligning national decarbonization goals with international transparency standards and carbon market requirements (Delgado et al., 2020; Pinedo-López et al., 2024).

2.5. Technological and Operational Barriers to Blockchain Implementation in CCUS and EOR

Despite the increasing attention given to blockchain-enabled traceability systems in energy and carbon management, several technological and operational barriers persist that hinder their widespread adoption in Enhanced Oil Recovery (EOR) and Carbon Capture, Utilization, and Storage (CCUS) applications. These limitations span hardware constraints, system integration challenges, regulatory gaps, and organizational resistance to technological transformation, especially in offshore oil and gas environments such as the Guajira Basin.

One of the most critical barriers is the limited digital infrastructure in many oil-producing regions, particularly in offshore contexts where telemetry networks and data transmission capabilities are often underdeveloped (Ramzey et al., 2024). Implementing blockchain-based MRV systems requires continuous and secure data flows from sensors, controllers, and monitoring devices to distribute ledgers, a process that may be hindered by connectivity issues, harsh environmental conditions, and power limitations on floating or subsea infrastructure (Krishnaraj et al., 2025; Pradhan et al., 2024). Another major challenge lies in data standardization and interoperability across legacy systems and blockchain platforms. Existing supervisory control and data acquisition (SCADA) systems were not designed with interoperability in mind and may require substantial retrofitting to enable integration with blockchain architecture. The lack of a common data ontology and standardized data exchange protocols creates friction in aligning on-chain and off-chain systems, which is vital for accurate and trustworthy MRV reporting (Sun et al., 2024).

The computational cost and latency of consensus mechanisms also limit real-time applications in high-frequency monitoring scenarios such as CO2 injection dynamics or pressure transients in EOR wells. While energy-efficient consensus algorithms such as Proof of Authority (PoA) offer improvements over Proof of Work (PoW), the trade-offs between decentralization, latency, and scalability remain unresolved in mission-critical applications (N. Kumar et al., 2025; Shinde et al., 2021). Moreover, cybersecurity vulnerabilities in blockchain-enabled systems remain a significant concern. Although blockchains are designed to be tamper-resistant, the broader ecosystem—including smart contracts, oracles, and external interfaces—is susceptible to attacks, particularly when deployed in complex operational environments with limited human oversight (Jovanovic et al., 2024; Yong et al., 2020). These concerns are amplified in CCUS projects involving high-pressure injection processes and subsurface uncertainties, where data integrity is crucial for safety and environmental compliance.

Institutional inertia and resistance to innovation further complicate deployment. Many oil and gas operators are still in the early stages of digital transformation, lacking in-house blockchain expertise or established governance models for decentralized information systems. In contexts like Colombia, limited access to funding for technological upgrades and fragmented stakeholder ecosystems also delay adoption (Delgado et al., 2020; Pinedo-López et al., 2024). Furthermore, the legal recognition of blockchain-verified records as admissible evidence in regulatory or financial proceedings is still underdeveloped in most Latin American jurisdictions. This uncertainty restricts the potential for blockchain-based MRV systems to replace conventional third-party audit mechanisms or serve as formal inputs in emissions trading or carbon tax schemes (Khudhair Mohammed & Farzaneh, 2024; Suárez Bermúdez et al., 2025). Lastly, human and organizational factors—such as resistance to transparency, fear of liability exposure, and lack of training—represent soft barriers that may limit implementation even in technically feasible scenarios. Blockchain imposes new responsibilities related to data entry accuracy, immutable logging, and decentralized validation, which may not align with the established operational culture of oil and gas enterprises accustomed to centralized control and minimal external scrutiny (Al-Rbeawi, 2023; Hanga & Kovalchuk, 2019).

These technological and operational challenges highlight the need for context-sensitive strategies to facilitate the integration of blockchain in CCUS and EOR workflows. Such strategies should involve public–private collaboration, regulatory modernization, and investments in digital infrastructure and human capital development, particularly in strategically relevant basins such as Guajira Offshore.

2.6. Research Gaps and Strategic Opportunities for Blockchain Adoption in Guajira Offshore

While global advancements in blockchain applications for energy and carbon-intensive industries are accelerating, there remains a significant research and implementation gap in the specific context of the Guajira Offshore Basin. The region’s potential for enhanced oil recovery (EOR) operations and geological CO2 storage has been well documented (Rodríguez et al., 2021; Suárez Bermúdez et al., 2025), yet little has been done to integrate advanced digital technologies such as blockchain into its operational and regulatory framework. One of the most prominent research gaps is the absence of real-world pilot projects or testbeds that evaluate blockchain-enabled MRV in offshore EOR settings under the specific environmental and institutional constraints of the Colombian Caribbean. Although blockchain-based MRV has demonstrated potential in onshore and industrial settings (Abdellatif et al., 2025; Sadri, 2025), its practical viability in remote offshore assets—where latency, connectivity, and trust-building among stakeholders are critical—remains underexplored.

Moreover, there is limited understanding of how blockchain can be used to enforce traceability and accountability in complex multiparty operations involving national oil companies (NOCs), private contractors, regulatory bodies, and indigenous or environmental interest groups. The fragmented governance landscape in Colombia, combined with underdeveloped digital infrastructure in the Caribbean region, presents unique constraints and requires tailored architectures for permissioned blockchain systems and identity management layers (Delgado et al., 2020; Pinedo-López et al., 2024). In addition, existing research has largely neglected the integration of blockchain with other emerging technologies critical for offshore operations, such as AI-based reservoir modeling, digital twins, edge computing, and smart sensor networks. While there is a growing body of work exploring the synergy between blockchain and machine learning in energy systems (Farag & Aly, 2024; Zeinolabedini et al., 2025), its specific implementation in CO2-EOR systems offshore—where real-time adaptability is paramount—remains conceptual rather than operational. Furthermore, current literature does not adequately address how blockchain systems might support compliance with evolving climate accountability standards, such as ISO 14064-2 or regional emissions trading schemes, particularly in Latin American jurisdictions. Without a robust digital MRV infrastructure, Colombia risks lagging in international carbon markets and failing to align its decarbonization strategies with emerging global expectations (Khudhair Mohammed & Farzaneh, 2024).

Strategically, the Guajira Offshore Basin represents an ideal testing ground for blockchain-enhanced EOR-MRV systems due to its geological potential, political importance, and position within Colombia’s decarbonization roadmap. Deploying such technologies here would not only improve operational transparency and efficiency but also position Colombia as a regional leader in digital innovation for carbon mitigation (Alyousef et al., 2025; Hosseinifard et al., 2025). The development of modular and adaptive blockchain architecture, co-designed with local stakeholders and calibrated to the specific geophysical, legal, and economic conditions of the Guajira Basin, emerges as a critical research opportunity. It would enable decentralized tracking of injected CO2 volumes, automate verification routines via smart contracts, and provide immutable logs for stakeholder auditing and policy evaluation.

This Working Paper directly addresses these research gaps by proposing a blockchain-based digital framework for EOR operations in Guajira Offshore, aligned with national policy priorities, resilient to regional technical limitations, and designed to integrate seamlessly with advanced data analytics and MRV workflows. Through a multidisciplinary synthesis of global experiences and regional needs, this initiative seeks to operationalize blockchain as a strategic enabler for Colombia’s energy transition.

4. Results

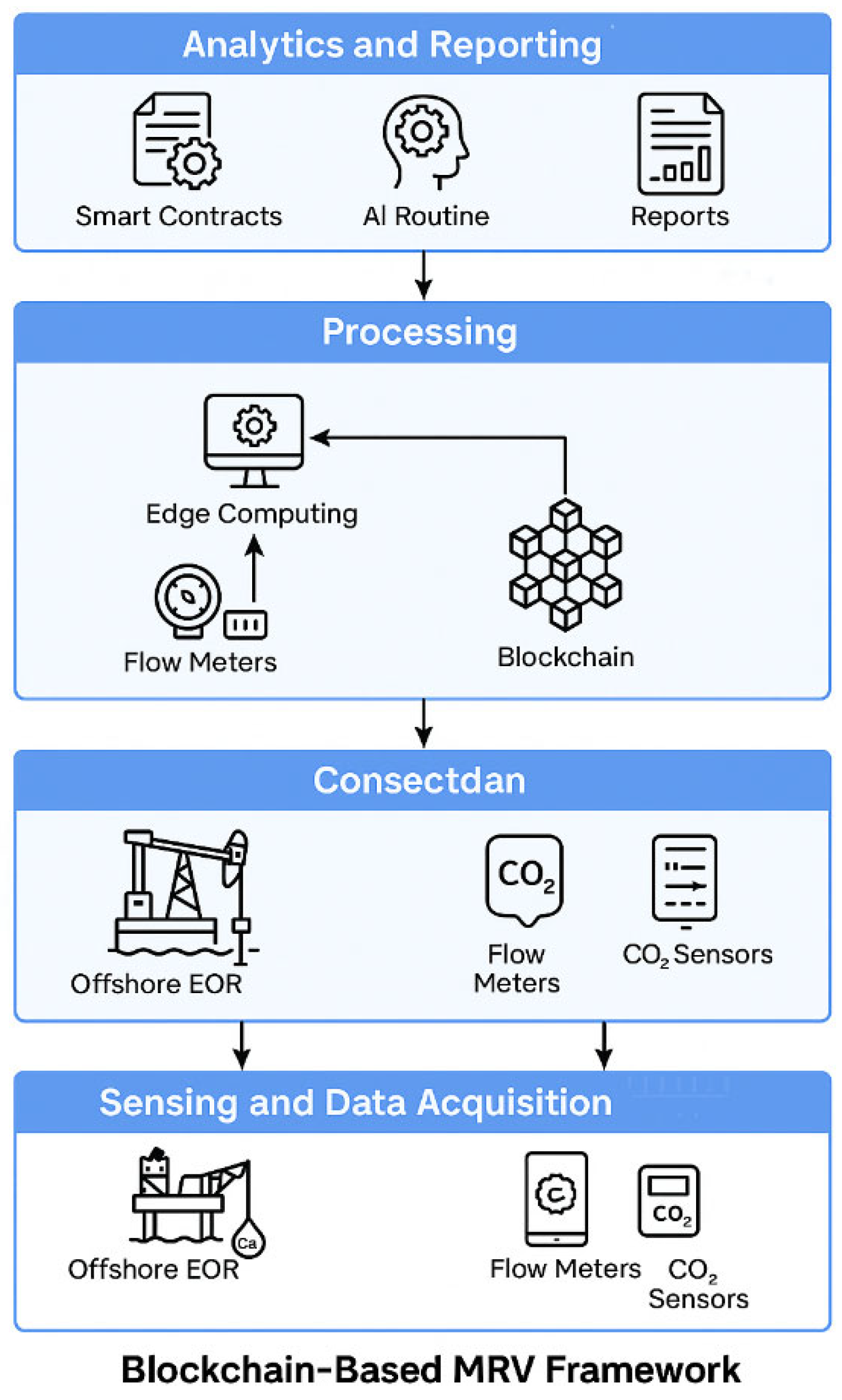

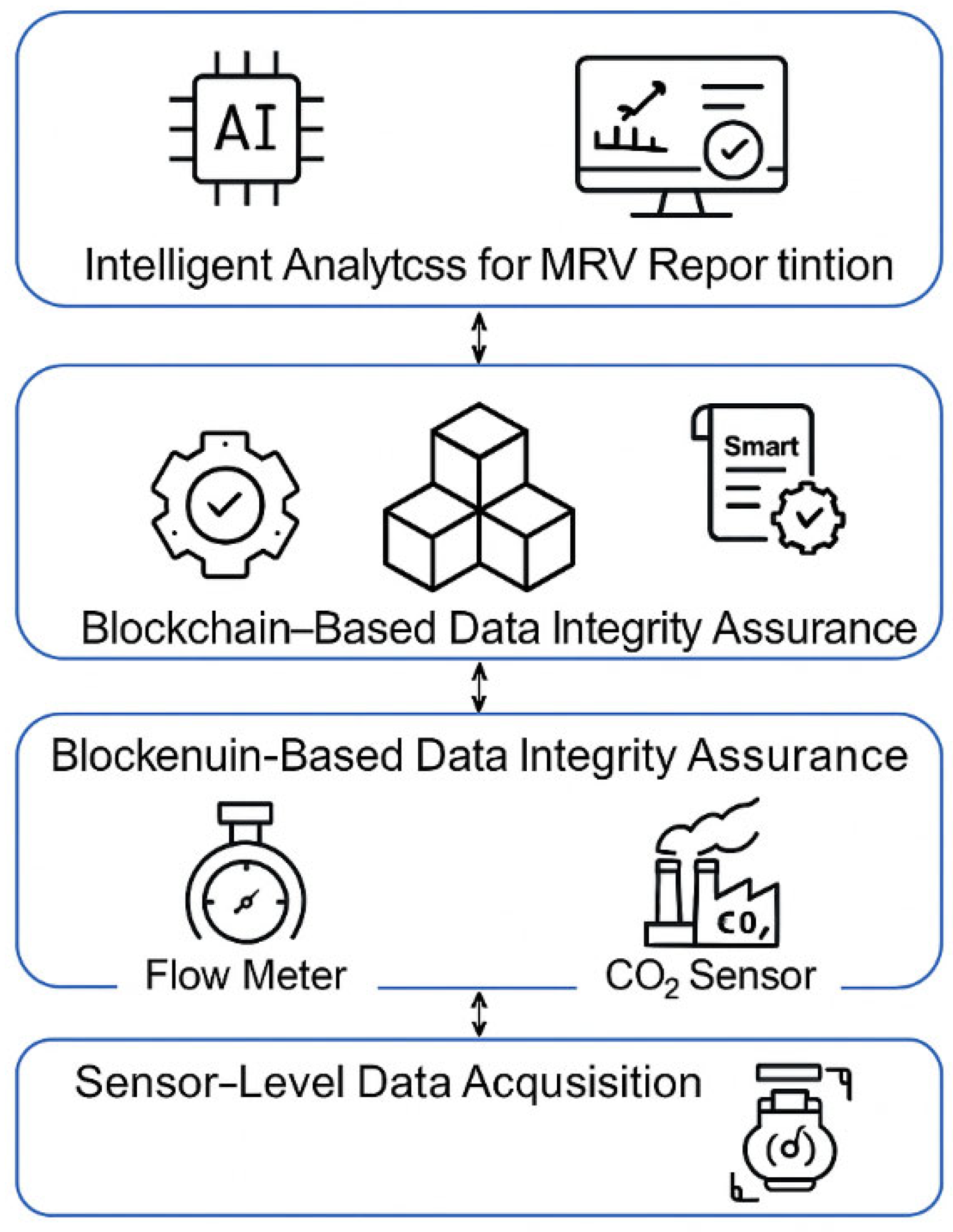

The proposed blockchain-based architecture was conceptualized to respond to the operational, regulatory, and technological gaps identified in current Enhanced Oil Recovery (EOR) workflows, especially in offshore regions such as the Guajira Basin in northern Colombia. Through the integration of decentralized ledger technologies, smart contracts, and AI-enhanced monitoring systems, the model addresses persistent challenges related to data fragmentation, lack of transparency, and the inefficiency of traditional MRV mechanisms. Each component of the layered framework (

Figure 2) was mapped to specific pain points encountered in CO

2 injection processes, including real-time validation of flow rates, injection pressures, and CO

2 purity metrics, as reported in similar studies across the energy sector (Abdellatif et al., 2025; Yang et al., 2024).

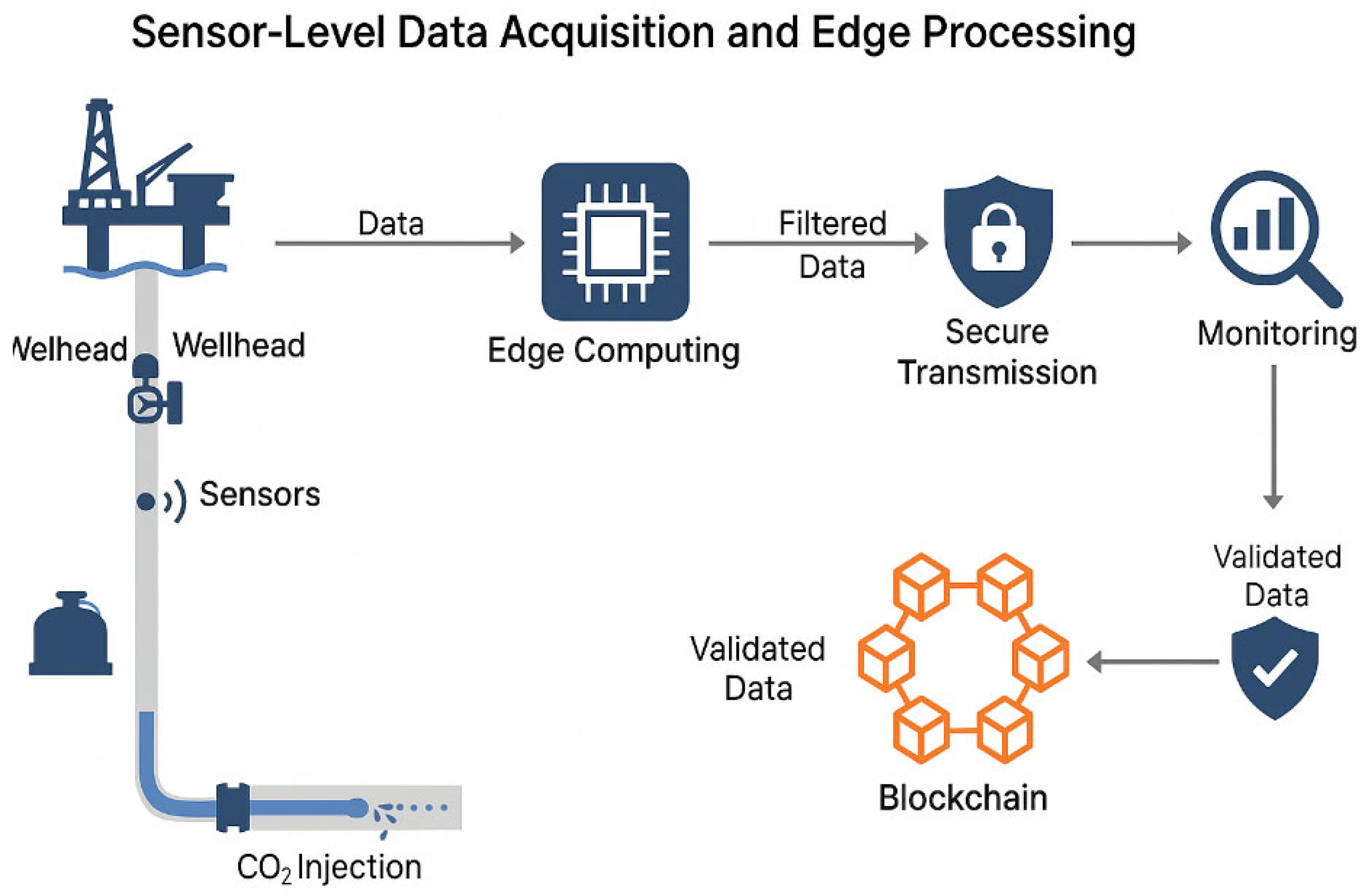

4.1. Sensor-Level Data Acquisition and CO2 Injection Monitoring

The first layer of the architecture is responsible for capturing high-resolution data directly from the physical environment of offshore CO2-EOR operations. In the specific context of the Guajira Offshore Basin, the remoteness and oceanic dynamics require a robust network of intelligent sensors capable of withstanding extreme conditions while continuously recording key variables such as injection pressure, flow rate, temperature, and CO2 purity. These sensors are strategically deployed at injection wells, monitoring stations, and flow lines to ensure full traceability of injected volumes and physical behavior throughout the reservoir. This level of instrumentation aligns with prior developments in smart field technologies and Industry 4.0 integration into oil and gas operations (Yang et al., 2024; Zeinolabedini et al., 2025).

The relevance of this layer lies in its ability to transform physical observations into digital assets that can be securely transferred to upper layers of the system. As shown in

Figure 3, the sensor network operates as the foundational infrastructure for real-time monitoring and early anomaly detection, supporting proactive management strategies. Each data point is labeled with time and geolocation metadata, enabling high-frequency spatial-temporal analyses essential for verifying CO

2 permanence and identifying leakage risks. Furthermore, data collected at this level feeds into edge processing modules and blockchain-based validation routines, ensuring that sensor manipulations or false data injections are detected and discarded before propagating through the system.

This layer also enables advanced diagnostic applications, such as automated fault detection and pattern recognition via machine learning algorithms deployed in adjacent modules. The synergy between robust sensor infrastructure and AI-assisted edge computing enhances the responsiveness of MRV systems, especially under uncertain offshore conditions. When combined with immutable storage mechanisms such as blockchain, this real-time, georeferenced sensing infrastructure ensures compliance with international carbon reporting standards while fostering trust among regulators, operators, and third-party verifiers (Hussain et al., 2024).

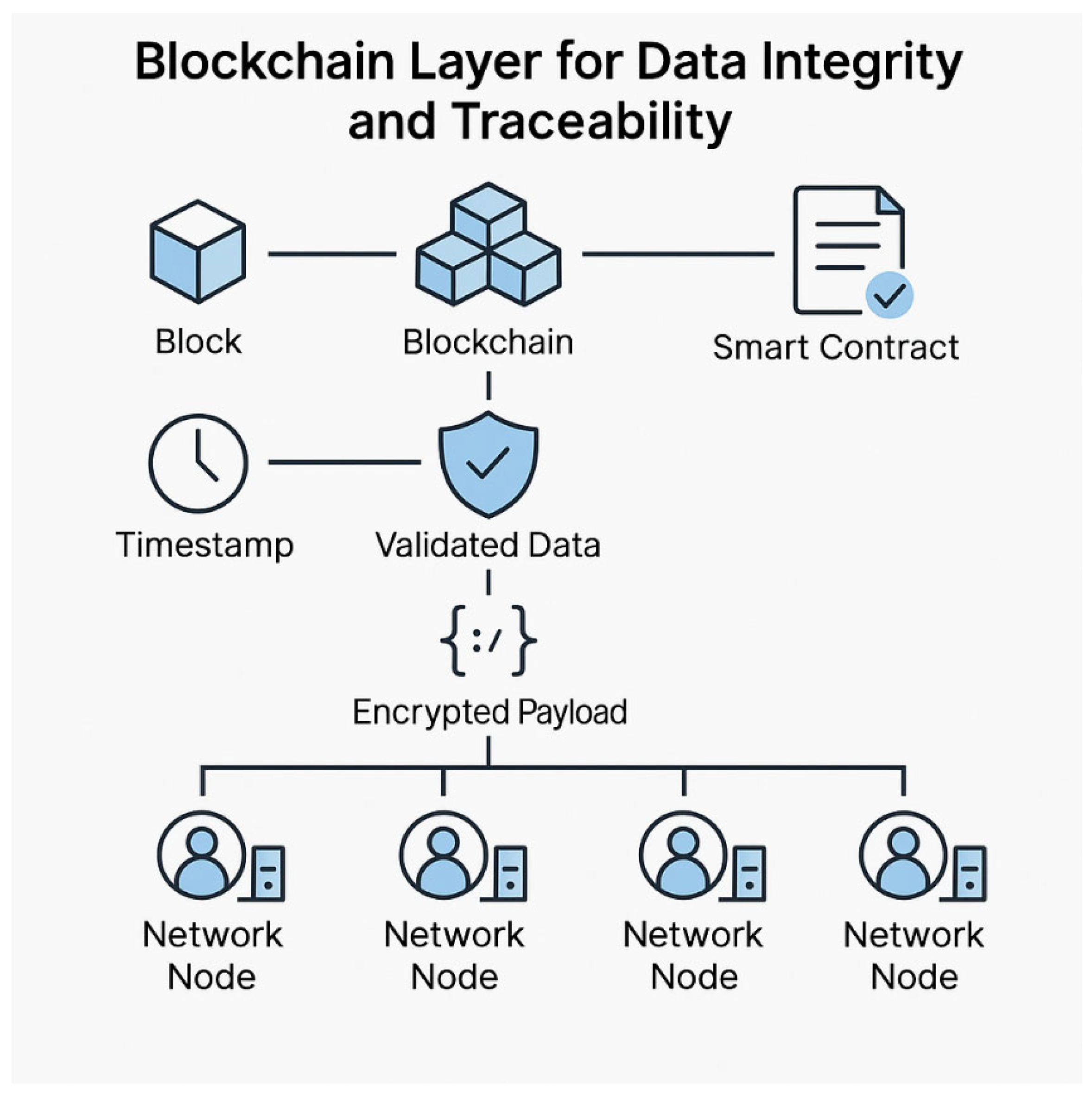

4.2. Blockchain Layer for Data Integrity and Traceability

The blockchain layer acts as the secure backbone of the architecture, ensuring that all data originating from sensor networks and intermediate analytical processes are recorded immutably, transparently, and with full traceability. In Enhanced Oil Recovery (EOR) workflows, particularly under offshore conditions like those in the Guajira Basin, ensuring that injection volumes, CO2 purity, and reservoir responses are accurately documented is critical for regulatory compliance and operational safety. Blockchain enables each data packet—whether originating from flow sensors, CO2 analyzers, or satellite telemetry—to be timestamped and hashed into blocks that form a distributed ledger across participating nodes. These nodes may include operators, environmental agencies, service companies, and auditors, creating a decentralized structure of accountability (Ressi et al., 2024).

A key advantage of this layer is its resistance to tampering and the ability to trace data lineage across the entire lifecycle of the CO2 injection and storage process. In contrast to traditional SCADA-based systems, which are often vulnerable to single-point failures or internal manipulation, blockchain ensures that once data is recorded, it cannot be retroactively altered without consensus from the network. Furthermore, the use of smart contracts enables automated triggering of validations, alerts, and compliance checks. For instance, if the injection pressure exceeds a regulatory threshold, a pre-coded smart contract can notify supervisory agents and pause injection activities until compliance is verified—ensuring real-time enforcement of MRV protocols (Jovanovic et al., 2024; N. Kumar et al., 2025).

This layer also supports data sharing under strict permissioned conditions through private or consortium-based blockchain configurations, balancing the need for transparency with confidentiality in competitive offshore EOR environments. Each transaction or event is cryptographically signed and auditable, significantly reducing disputes in measurement verification and reducing costs associated with manual data reconciliation. In highly regulated jurisdictions such as Colombia, where emerging carbon markets and international monitoring obligations are expanding, the ability to offer verifiable and immutable MRV records provides a competitive advantage and aligns with broader decarbonization objectives (Delgado et al., 2020; Suárez Bermúdez et al., 2025).

Figure 4 illustrates the interactions between blockchain nodes and smart contracts that enable this layer to function as a secure and intelligent registry of operational integrity.

4.3. Smart Contracts and AI-Based Anomaly Detection

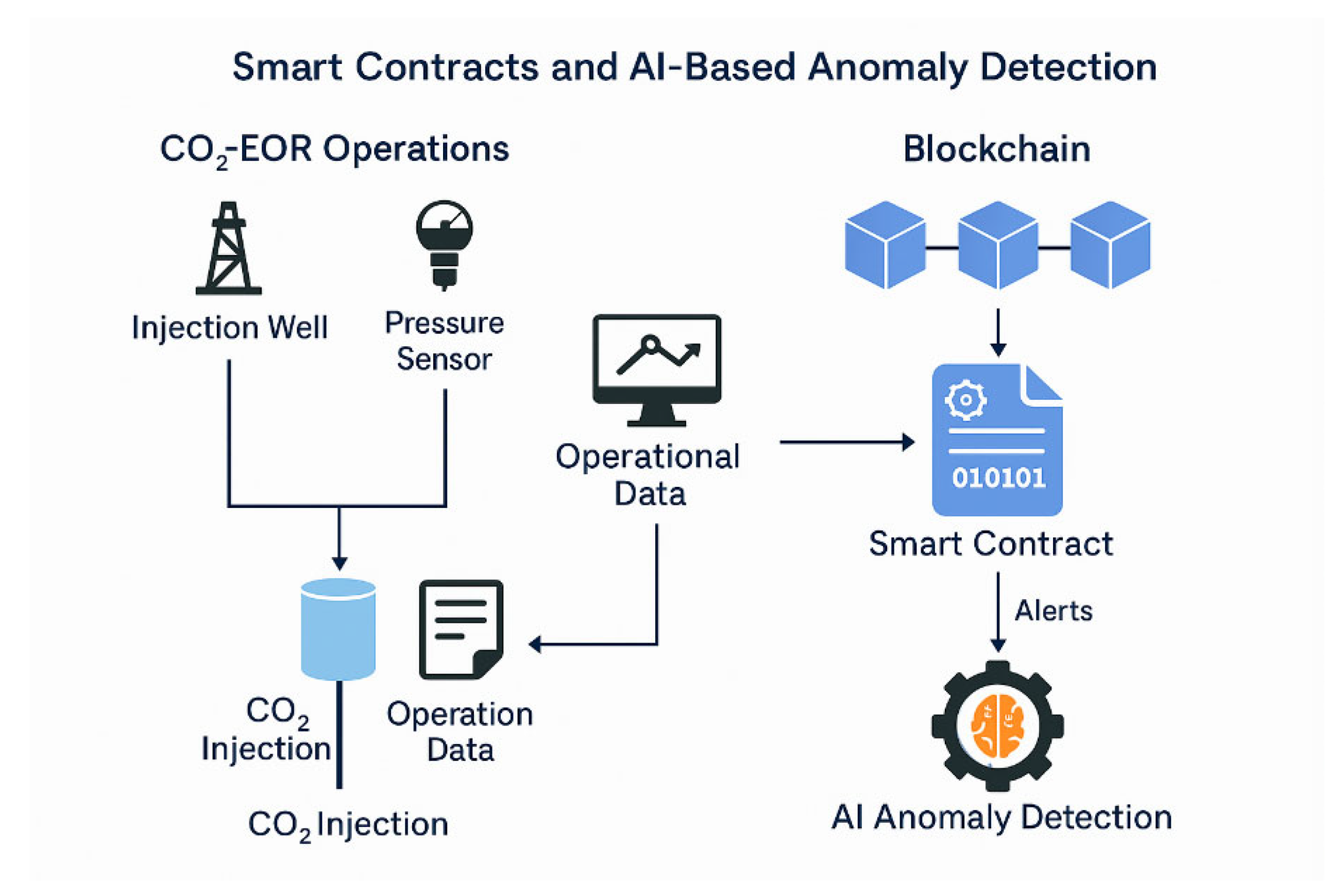

The integration of smart contracts into Enhanced Oil Recovery (EOR) systems presents a paradigm shift in the automation and governance of key operational processes (

Figure 5). In the context of offshore operations like those in the Guajira Basin, smart contracts can enforce rules associated with CO

2 injection thresholds, compliance with environmental limits, and financial transactions between stakeholders in a transparent and immutable manner. These contracts operate autonomously within the blockchain, reducing dependence on intermediaries and minimizing delays in decision-making. For example, if a CO

2 injection well surpasses a critical pressure limit, a pre-coded smart contract can automatically trigger a halt command or alert regulatory authorities (Yong et al., 2020). This embedded governance capability not only ensures real-time responsiveness but also bolsters regulatory adherence in regions with complex operational oversight.

Simultaneously, the use of artificial intelligence (AI)-based anomaly detection algorithms enhances the predictive and diagnostic capabilities of the EOR monitoring infrastructure. AI models trained on historical and real-time data can identify subtle deviations in operational parameters—such as temperature gradients, seismic responses, or fluid compositions—that might indicate equipment malfunction, reservoir integrity issues, or pipeline leaks (Farag & Aly, 2024; Hussain et al., 2024). When coupled with smart contracts, these AI insights can trigger predefined remediation protocols, such as automated shutoffs or reallocation of operational resources. This dual integration not only augments situational awareness but also significantly reduces the time between incident detection and corrective action, which is critical in high-risk offshore settings.

Moreover, smart contracts contribute to improved data accountability in Measurement, Reporting, and Verification schemes. Every recorded anomaly, intervention, or operational decision can be immutably documented on the blockchain through an automated contract execution. This ledger-based accountability fosters trust among stakeholders—including operators, regulators, and financiers—by ensuring that all corrective and preventive measures are verifiable and tamper-proof (Jovanovic et al., 2024). Importantly, the combination of AI and blockchain not only enhances security but also facilitates forensic analyses and continuous improvement loops within EOR workflows, which are especially necessary in geologically complex and environmentally sensitive zones like Guajira Offshore.

Finally, the integration of federated learning with blockchain and smart contracts has emerged as a promising approach to balance data privacy and model accuracy in collaborative anomaly detection systems. In offshore environments where data-sharing across multiple platforms and jurisdictions is common, federated models allow AI agents to learn from distributed datasets without transferring sensitive raw data (Yong et al., 2020). When governed by smart contracts, this learning process becomes verifiable and traceable, ensuring that each stakeholder adheres to agreed-upon data use policies. Such architectures are well suited for cross-organizational monitoring of EOR operations, where equipment suppliers, field operators, and environmental agencies may contribute heterogeneous data under strict confidentiality and auditability requirements.

4.4. MRV Reporting and Regulatory Interface

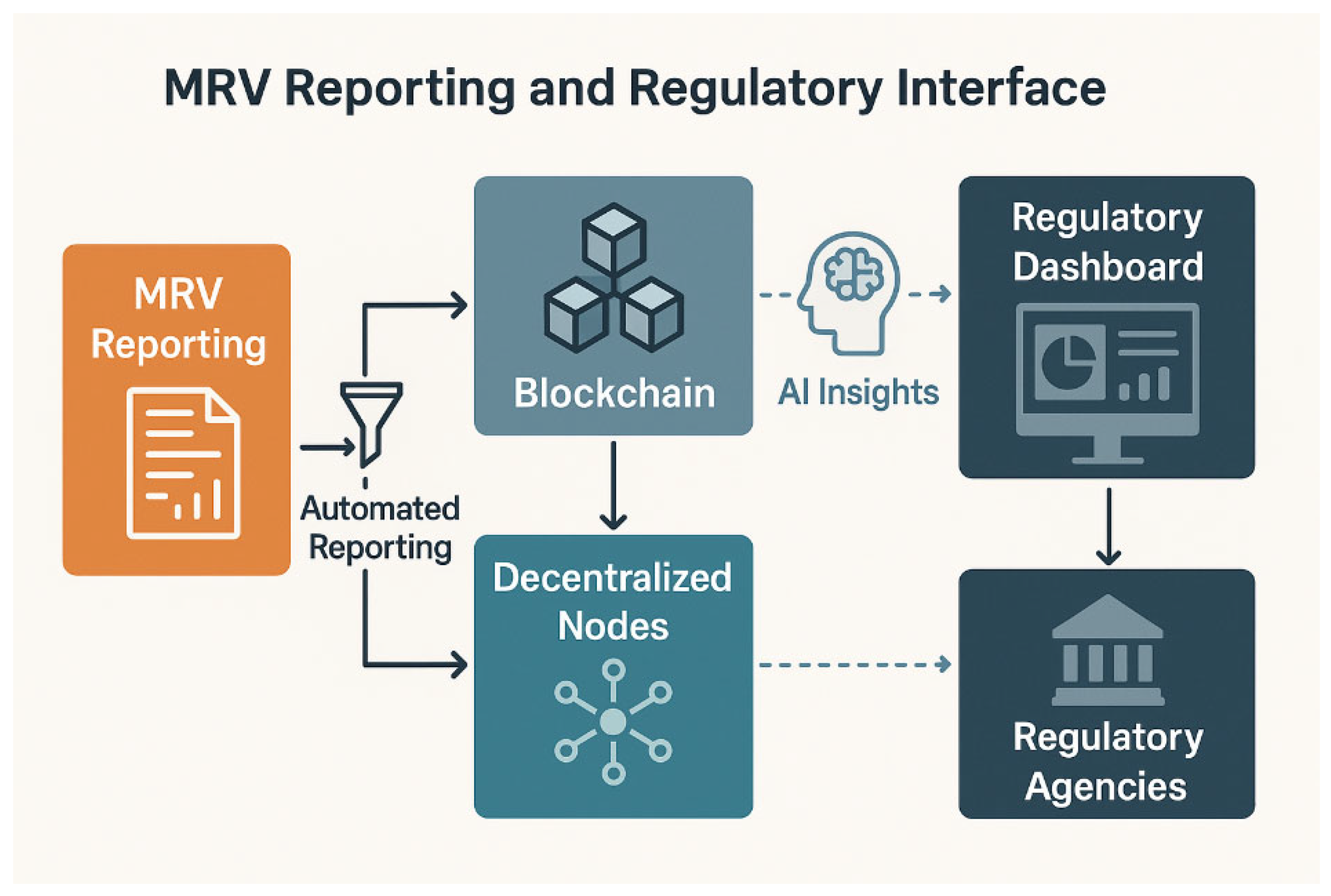

MRV layer represents the critical interface between the operational data generated within Enhanced Oil Recovery (EOR) systems and the regulatory bodies responsible for environmental oversight and compliance. In the context of CO

2-EOR projects, particularly in sensitive offshore environments like the Guajira Basin, this interface must guarantee accuracy, immutability, and timeliness in reporting carbon injection volumes, retention rates, and potential leakages. Traditional MRV systems often rely on siloed databases, manual reporting protocols, and retrospective audits that delay action and obscure accountability (Yang et al., 2024). The blockchain-based MRV framework addresses these limitations by embedding smart rules that automatically log, timestamp, and relay verified operational data to authorized parties via decentralized node (

Figure 6).

This framework supports a multilayered reporting mechanism in which data is validated at the sensor and process control levels before being packaged into structured blocks. These blocks are cryptographically hashed and linked in an immutable sequence, ensuring that the reported metrics are tamper-proof and auditable by design (Abdellatif et al., 2025). Through integration with federated identity management and role-based access controls, regulatory institutions such as the Colombian Ministry of Mines and Energy or ANH (Agencia Nacional de Hidrocarburos) can securely access live dashboards and compliance records without direct access to proprietary infrastructure. This architecture guarantees transparency and operational sovereignty simultaneously—two features seldom coexisting in traditional energy regulatory systems.

In terms of compliance workflows, the MRV interface facilitates dynamic and continuous reporting aligned with evolving carbon market schemes and CO2 tax regulations. As Colombia moves toward its national decarbonization commitments (Delgado et al., 2020), the ability to demonstrate permanent CO2 sequestration in offshore formations will be essential for accessing credits in voluntary or mandatory carbon markets. The architecture accommodates this by linking each MRV event to certified geolocation data, injection conditions, and geological models (Suárez Bermúdez et al., 2025). Smart contracts can even trigger predefined alerts or automated compliance filings when anomalous behaviors are detected—such as injection anomalies, plume migration beyond containment zones, or threshold breaches in storage pressure.

A notable feature of the MRV system is its auditability in both technical and regulatory domains. Auditors can reconstruct injections and monitor events across time without relying on third-party data consolidators or manual verification. Furthermore, machine-readable regulatory templates ensure compatibility with international MRV standards, including ISO 14064-2 for greenhouse gas projects and specific Colombian environmental licenses. These digital templates can be updated via decentralized governance mechanisms, allowing for adaptation to future policy evolutions or offshore-specific EOR rulesets. Ultimately, this MRV framework not only fulfills legal requirements but enhances stakeholder trust, supports climate finance instruments, and improves the resilience of CO2-EOR operations in frontier regions. Its design is particularly advantageous for the Guajira Offshore context, where logistical remoteness, high environmental stakes, and political oversight converge. By fusing blockchain transparency, AI-enhanced anomaly detection, and robust reporting protocols, the MRV layer becomes a cornerstone of credible, science-based carbon management in Colombia’s energy transition roadmap.

6. Conclusions and Future Work

This study proposed and conceptualized a blockchain-based digital architecture designed to improve transparency, efficiency, and regulatory compliance in offshore EOR projects, with a particular focus on the Guajira Offshore Basin in Colombia. By integrating sensor-level monitoring, decentralized data storage, smart contracts, AI-powered anomaly detection, and regulatory interfaces into a modular framework, architecture aims to overcome longstanding challenges in MRV systems. The design directly addresses pain points such as data opacity, inconsistent reporting, and weak traceability, which have hindered the credibility of CO2 injection operations across the EOR industry.

The layered architecture, validated through schematic modeling and aligned with recent developments in blockchain, CCUS, and AI technologies, represents a novel contribution to the digitalization of oilfield operations. The results demonstrate that blockchain technology, when properly configured with smart sensors and AI algorithms, can enable secure, real-time, and auditable data flows for offshore MRV. This approach is particularly relevant for jurisdictions aiming to participate in emerging carbon markets, offering a digital backbone that supports the issuance of verifiable carbon credits based on CO2 sequestration metrics. In addition to technical benefits, the proposed system holds significant implications for public trust, investor confidence, and international accountability. The ability to trace injected CO2 volumes, validate operational integrity, and interface with regulatory authorities through immutable digital records represents a step forward in the governance of carbon-intensive industries. As nations like Colombia move toward mid-century decarbonization goals, digital infrastructures such as the one proposed here will be essential for aligning industrial activity with climate commitments and economic incentives (Delgado et al., 2020).

Nevertheless, real-world deployment will require addressing several limitations. These include the need for offshore digital infrastructure, legal frameworks to support blockchain-enabled compliance, and robust protocols for AI validation under uncertain reservoir conditions. Moreover, the integration with existing SCADA systems, cybersecurity protections, and interoperability with carbon registries must be further studied and tested under pilot-scale conditions.

Future work will begin with the implementation of the proposed architecture in a simulation environment using real or synthetic operational data from offshore EOR wells. This initial stage will serve to validate the logic of smart contracts, test interoperability modules, and assess the responsiveness of the anomaly detection algorithms under controlled conditions. Additional research will explore the integration of quantum-resistant blockchain algorithms, federated learning models for decentralized intelligence, and adaptive smart contracts that evolve in response to changing operational thresholds. Field testing in selected offshore assets in the Guajira Basin—supported by stakeholder engagement and regulatory sandboxing—will be crucial to validate the model’s readiness for full-scale deployment. In the short to medium term, a functional prototype will be developed using edge-compatible hardware (e.g., Raspberry Pi or ruggedized offshore IoT nodes) and integrated into a permissioned blockchain network such as Hyperledger Fabric or a consortium-based Ethereum implementation. This setup will enable proof-of-concept testing for sensor-level data acquisition, real-time anomaly detection, and automated alert systems triggered by smart contracts. Concurrently, synthetic datasets simulating CO2 injection rates, downhole pressure variations, and gas purity fluctuations will be used to train and validate the AI modules, ensuring traceability and compatibility with regulatory audit trails and carbon offset registries.

Furthermore, the architecture will be enhanced to support seamless interoperability with national and international MRV systems, particularly those aligned with ISO 14064 standards and methodologies recognized by the Verified Carbon Standard (VCS) and Gold Standard. The system will be designed to automatically generate standardized MRV reports (e.g., in XML or JSON formats) compatible with digital climate registries, thereby reducing administrative overhead and enhancing data transparency. An additional research avenue involves the incorporation of zero-knowledge proof (ZKP) cryptographic techniques, which allow for the confidential validation of critical metrics (e.g., CO2 volumes injected) without exposing sensitive operational data—a valuable feature in offshore settings involving multiple operators.

In the long term, the proposed framework will evolve into a multi-agent and federated blockchain ecosystem that enables secure collaboration across diverse stakeholders such as operators, regulators, and third-party verifiers. The system’s resilience will be tested under a variety of disruption scenarios—including sensor failure, communication latency, and cybersecurity breaches—to ensure robustness and fault tolerance. Finally, future studies will focus on aligning the architecture with evolving carbon pricing mechanisms and legal frameworks in Colombia and Latin America, guaranteeing that the system remains policy-compliant and technologically sustainable in dynamic geopolitical and environmental contexts.