1. Introduction

The global transition toward electric mobility has positioned electric vehicles (EVs) and lithium-ion batteries (LIBs) at the forefront of sustainable transportation strategies. Governments and industries alike are accelerating EV adoption to meet carbon neutrality goals and reduce reliance on fossil fuels [

7]. At the core of this transformation lies a pressing need to enhance the environmental and ethical performance of LIB and EV supply chains, which remain complex, opaque, and increasingly scrutinized for their sustainability shortcomings.

Key challenges permeate every stage of the LIB lifecycle—from the

extraction of raw materials such as lithium, cobalt, and nickel, often associated with environmental degradation and human rights violations [

5], to the

energy-intensive manufacturing processes, and the

end-of-life (EOL) handling of battery systems, which, if poorly managed, risk

resource loss and environmental pollution [

29]. Furthermore, the

lack of supply chain traceability undermines efforts to verify ethical sourcing, manage performance data, and ensure product authenticity [

23].

In response to these challenges, the application of

Digital Product Passports (DPPs) and

blockchain technology has gained traction as a transformative strategy. DPPs provide a structured digital record of a product’s entire lifecycle, including data on material origin, energy usage, environmental footprint, and recyclability [

4]. When integrated with blockchain—a decentralized, immutable ledger system—DPPs can enable secure, transparent, and tamper-proof tracking of LIB components and EV systems across global supply chains [

2,

13].

Moreover, the dynamic nature of supply chain logistics and battery performance necessitates real-time, adaptive decision-making. Here,

machine learning, particularly

reinforcement learning (RL), plays a critical role. RL algorithms can optimize routing for battery collection, anticipate maintenance needs, and minimize operational costs by learning from continuously updated DPP and blockchain data streams [

9].

The convergence of these technologies—DPPs for data richness, blockchain for integrity and trust, and ML for optimization—offers a timely, scalable solution to address the multifaceted sustainability and transparency gaps in the LIB and EV ecosystem. Supporting circular economy objectives, this integrated framework builds a resilient, interoperable infrastructure that enables ethical sourcing, sustainability, and innovation across the value chain.

2. Literature Review and Background

2.1. Evolution of Lithium-Ion Batteries (LIBs)

Lithium-ion batteries (LIBs) have undergone remarkable development since their commercial introduction in the early 1990s. Driven by improvements in energy density, thermal stability, and charge-discharge efficiency, LIBs have become the standard energy storage technology for electric vehicles (EVs) and portable electronics [

31]. Recent innovations have focused on cathode material composition, battery management systems, and solid-state designs to extend battery life and enhance safety.

As EV adoption surges, the scale of LIB production has grown exponentially. However, this growth introduces substantial challenges in raw material demand, manufacturing emissions, and post-consumer waste. Managing these impacts requires end-to-end visibility across the battery’s lifecycle.

2.2. Traceability and End-of-Life Challenges

Current LIB supply chains lack standardized, transparent systems for tracking the origin, processing, and condition of battery components. This

traceability gap obscures environmental and ethical risks, such as child labor in cobalt mining and carbon-intensive material extraction [

5,

23].

Moreover,

end-of-life (EOL) management of LIBs remains inefficient. Many batteries are landfilled or inadequately recycled, resulting in the loss of critical materials and increased environmental harm [

29]. The absence of integrated systems to monitor battery state-of-health, usage history, and recyclability hinders circular economy practices and compliance with emerging regulatory frameworks.

2.3. Digital Product Passports (DPPs)

Digital Product Passports (DPPs) are emerging as a critical solution to support sustainability and circularity in industrial ecosystems. A DPP is a structured, digital record that stores comprehensive information about a product’s composition, production methods, environmental impact, and usage lifecycle [

4]. In the LIB and EV sector, DPPs facilitate informed decisions by manufacturers, recyclers, regulators, and consumers.

By collecting real-time data from IoT sensors and supply chain nodes, DPPs enable granular visibility into material flows and component histories. This empowers stakeholders to optimize reuse strategies, verify compliance, and manage EOL pathways more effectively.

2.4. Blockchain for Supply Chain Integrity

Blockchain technology reinforces DPP functionality by offering

immutable, transparent, and decentralized records of supply chain transactions. It is especially valuable in fragmented, multi-stakeholder environments like EV battery supply chains. Blockchain enables secure tracking of raw materials, component authenticity, and custody events across borders [

2].

Platforms like

Hyperledger Fabric support enterprise-grade scalability and permissioned access, which are essential for maintaining privacy while meeting compliance demands. Additionally, blockchain’s ability to link physical and digital assets facilitates anti-counterfeiting and warranty verification [

26].

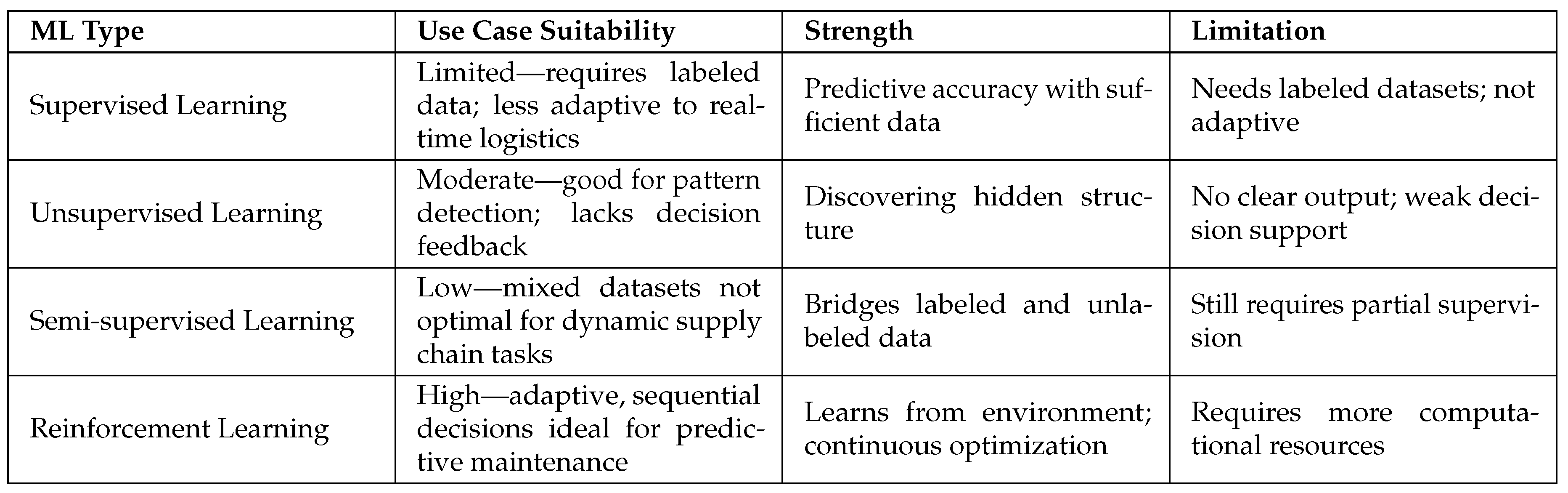

2.5. Reinforcement Learning (RL) for Optimization

Reinforcement learning (RL), a branch of machine learning, is well-suited to optimizing sequential decision-making in dynamic systems. In the context of LIB and EV supply chains, RL can be used to:

Predict battery degradation patterns

Optimize logistics for recycling routes

Schedule preventive maintenance actions

Compared to supervised or unsupervised learning, RL adapts to feedback over time, making it highly effective for minimizing operational costs and resource inefficiencies [

9].

2.6. zkSNARKs and Privacy Preservation

While blockchain ensures transparency, privacy concerns remain, particularly in industrial settings involving proprietary data.

Zero-Knowledge Succinct Non-Interactive Arguments of Knowledge (zkSNARKs) provide a cryptographic method to

prove the validity of a statement without revealing the underlying data [

13]. This allows for verifiable tracking and compliance without exposing sensitive business information, making zkSNARKs a key enabler of secure and privacy-preserving blockchain applications in supply chains.

3. Research Objectives and Questions

To address the sustainability and transparency challenges facing LIB and EV supply chains, this research explores an integrated technological framework that combines Digital Product Passports (DPPs), blockchain, reinforcement learning (RL), and privacy-preserving cryptographic tools such as zkSNARKs. The following objectives and questions guide the study.

3.1. Research Objectives

Evaluate the role of DPPs in improving lifecycle transparency and facilitating material reuse across the LIB and EV value chains [

4].

Examine blockchain technology as a mechanism for enhancing traceability, data security, and verification of third-party and aftermarket components in DPP-enabled systems [

2].

Apply RL models to optimize supply chain logistics and predictive maintenance strategies, thereby extending battery lifespan and reducing the total cost of ownership (TCO) for EVs [

9].

Assess zkSNARKs integration for maintaining privacy and compliance in blockchain-based supply chains, while ensuring transparency and verifiability for all stakeholders [

13].

3.2. Research Questions

How can DPPs improve lifecycle management and facilitate material reuse in the LIB and EV sectors, aligned with circular economy principles?

How can blockchain technology enhance traceability, component authenticity, and stakeholder trust in complex and global EV supply chains?

In what ways can RL optimize logistics and predictive maintenance to extend battery life and reduce operational costs?

How can zkSNARKs and similar privacy-preserving mechanisms support secure, transparent data management in blockchain-based supply chains?

4. Methodology

This study adopts a multidisciplinary and technology-driven methodology that combines DPPs, blockchain, machine learning—specifically RL—and privacy-preserving cryptographic mechanisms. Together, these technologies form a framework for improving lifecycle management, sustainability, and operational efficiency in LIB and EV supply chains.

4.1. Digital Product Passports (DPPs)

DPPs serve as dynamic, digital representations of physical LIB and EV components. Each passport contains comprehensive and standardized lifecycle data, including:

Material provenance: source and composition of raw materials such as lithium, cobalt, and nickel [

2].

Manufacturing data: energy and water consumption, waste generation, and carbon footprint [

24].

Performance metrics: real-time battery health, degradation rates, and projected remaining life [

29].

End-of-life pathways: instructions for recycling and reuse [

11].

DPPs aggregate data from IoT sensors, manufacturers, and certified recyclers to ensure

data completeness and reliability, enabling

real-time lifecycle monitoring for better decision-making [

4].

4.2. Blockchain Technology

Blockchain underpins the DPP system by offering

data integrity, traceability, and immutability. Using

Hyperledger Fabric, the framework enables secure, permissioned data exchange [

13]. Key capabilities include:

Provenance tracking: verifying raw material origins from source to final product [

27].

Anti-counterfeiting: time-stamped records confirm component authenticity [

26].

Stakeholder collaboration: shared ledgers enhance trust across OEMs and regulators [

8].

To preserve privacy,

zkSNARKs verify information validity

without revealing sensitive business data [

13], and

IT security mechanisms prevent tampering and ensure auditability [

28].

4.3. Machine Learning—Reinforcement Learning (RL)

RL is selected for optimizing

sequential decision-making in LIB logistics [

9]. RL continuously learns from system feedback to maximize long-term efficiency. Use cases include:

Predictive maintenance: anticipate faults and enable proactive servicing.

Logistics optimization: reduce emissions and routing costs.

Resource allocation: improve component distribution across warehouses.

This capability is strengthened by

AI–blockchain convergence, ensuring automation and secure supply chain operations [

19].

Figure 1.

Comparison of Machine Learning Approaches for EV Supply Chains.

Figure 1.

Comparison of Machine Learning Approaches for EV Supply Chains.

5. Results and Evaluation

5.1. Experimental Setup

All experiments were conducted in Google Colab using the

Multiple Time Window Vehicle Routing Problem (VRP) dataset [

33], an extension of the well-known Solomon benchmarks. Each instance contains 100 customers with multiple delivery time windows, depot information, and demand constraints. To emulate supply chain logistics for electric vehicle (EV) battery collection and recycling, we adopted the following assumptions: vehicle capacity set at 15% of total demand, travel speed normalized to 1 distance unit per time unit, a cost factor of 1 unit per km, and an emission factor of 0.18 kg CO

2/km.

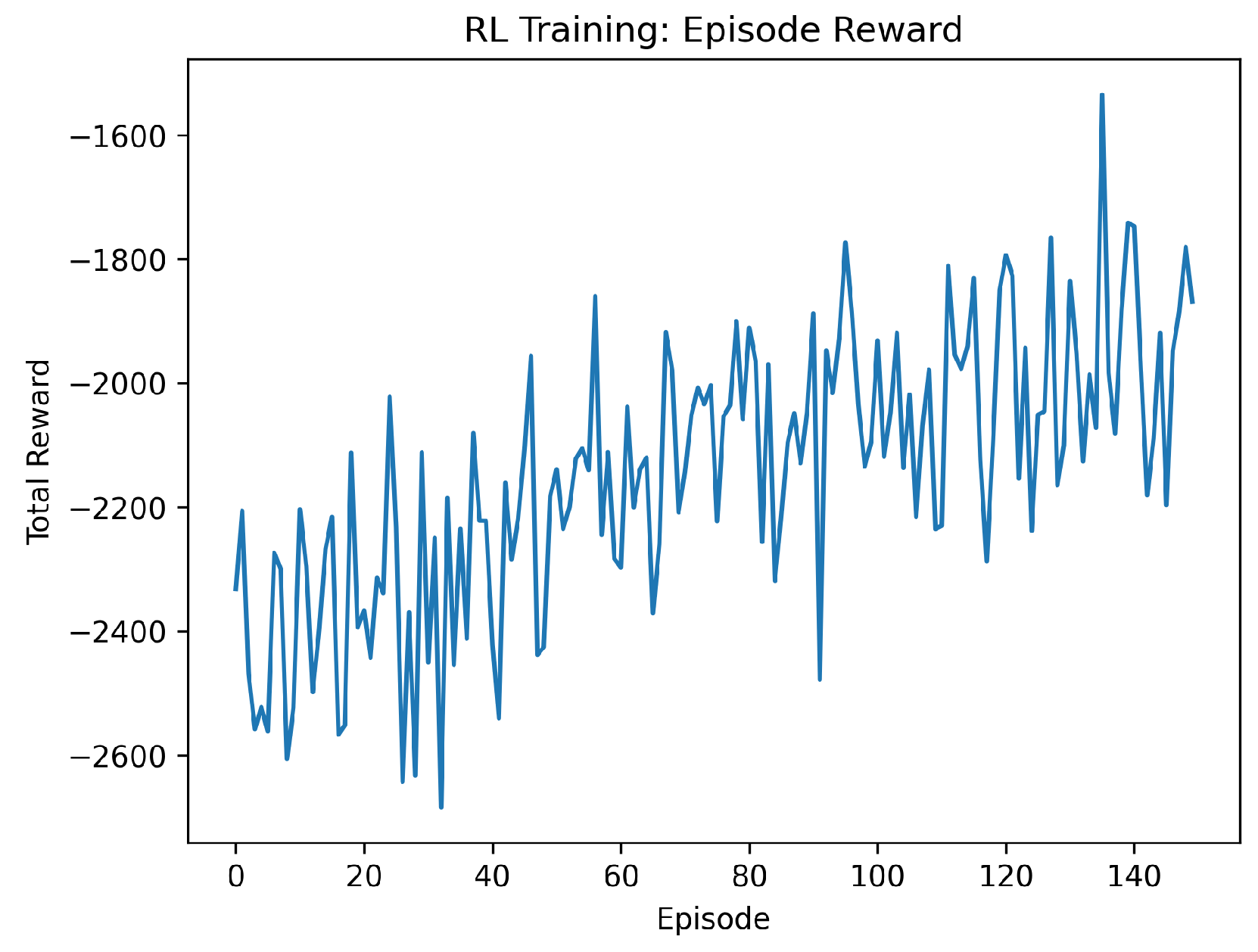

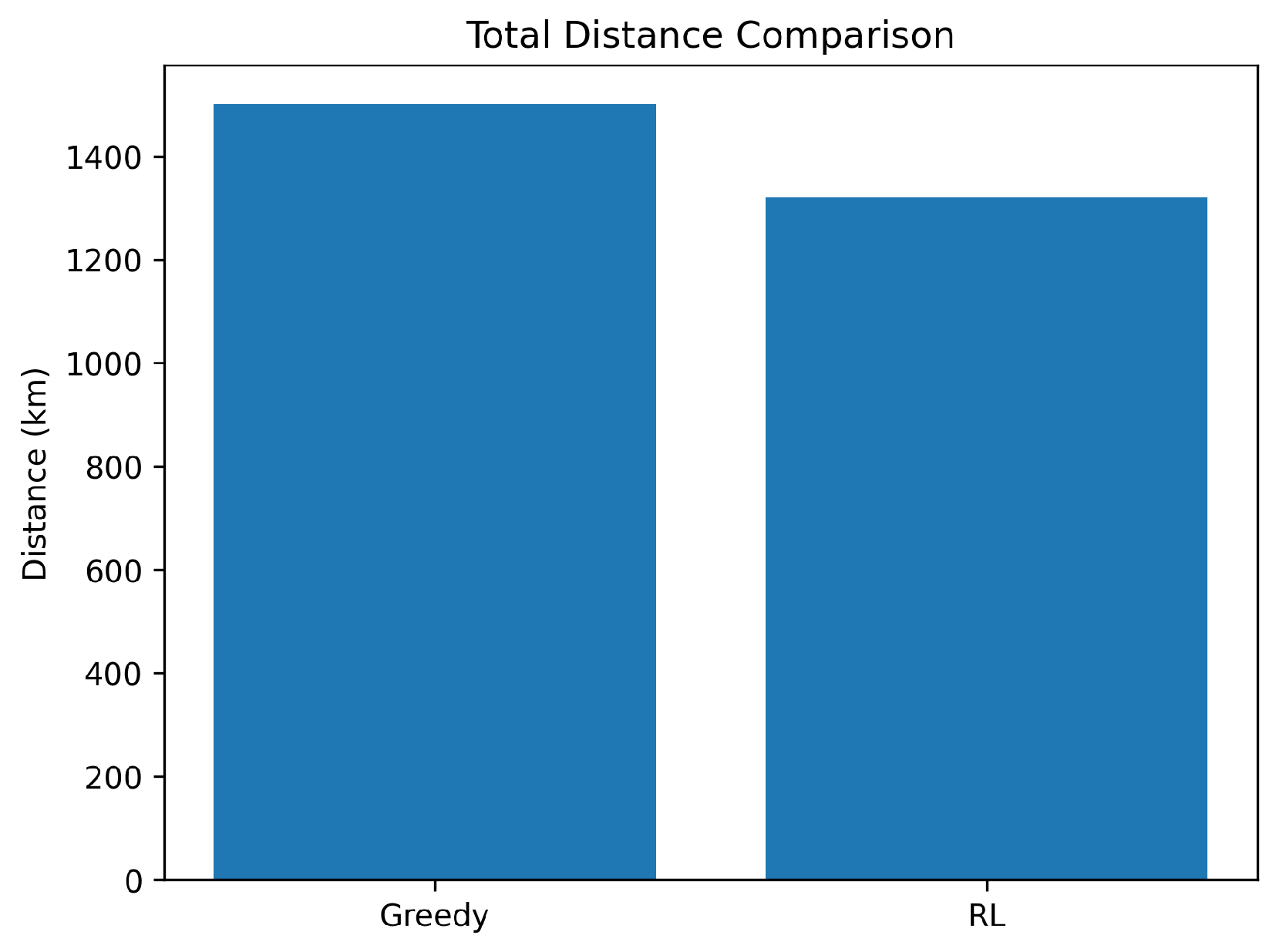

We compared two methods:

Greedy baseline: nearest-feasible customer selection subject to time window and capacity constraints.

Reinforcement Learning (RL): a Deep Q-Network (DQN) with candidate pruning () trained for 150 episodes.

5.2. Evaluation Metrics

We measured three performance indicators:

Total Distance (km): cumulative route length traveled.

Total Cost: proportional to distance, assuming 1 unit cost per km.

CO2 Emissions (kg): calculated using an emission factor of 0.18 kg/km.

5.3. Results

Table 1 summarizes the results for a representative Solomon MTW instance (C101). The RL approach outperformed the greedy baseline, achieving shorter routes, reduced costs, and lower emissions.

The RL-based optimizer achieved an average cost reduction of 12.9% compared to the greedy baseline.

Figure 2 shows the RL training reward curve, confirming stable policy convergence, while

Figure 3 illustrates the reduction in total travel distance achieved by RL.

5.4. Discussion and Limitations

These results demonstrate that reinforcement learning can significantly improve logistics efficiency in EV supply chain scenarios modeled by VRP with multiple time windows. The reduction in distance and cost illustrates how AI-driven optimization, when combined with blockchain-enabled Digital Product Passports (DPPs), can support sustainability by reducing energy use and emissions.

However, the evaluation is limited to benchmark datasets and simulated assumptions (e.g., constant service times, uniform emission factors). Future work should integrate real industrial datasets, heterogeneous fleets, and stochastic delays to further validate scalability and robustness in practice.

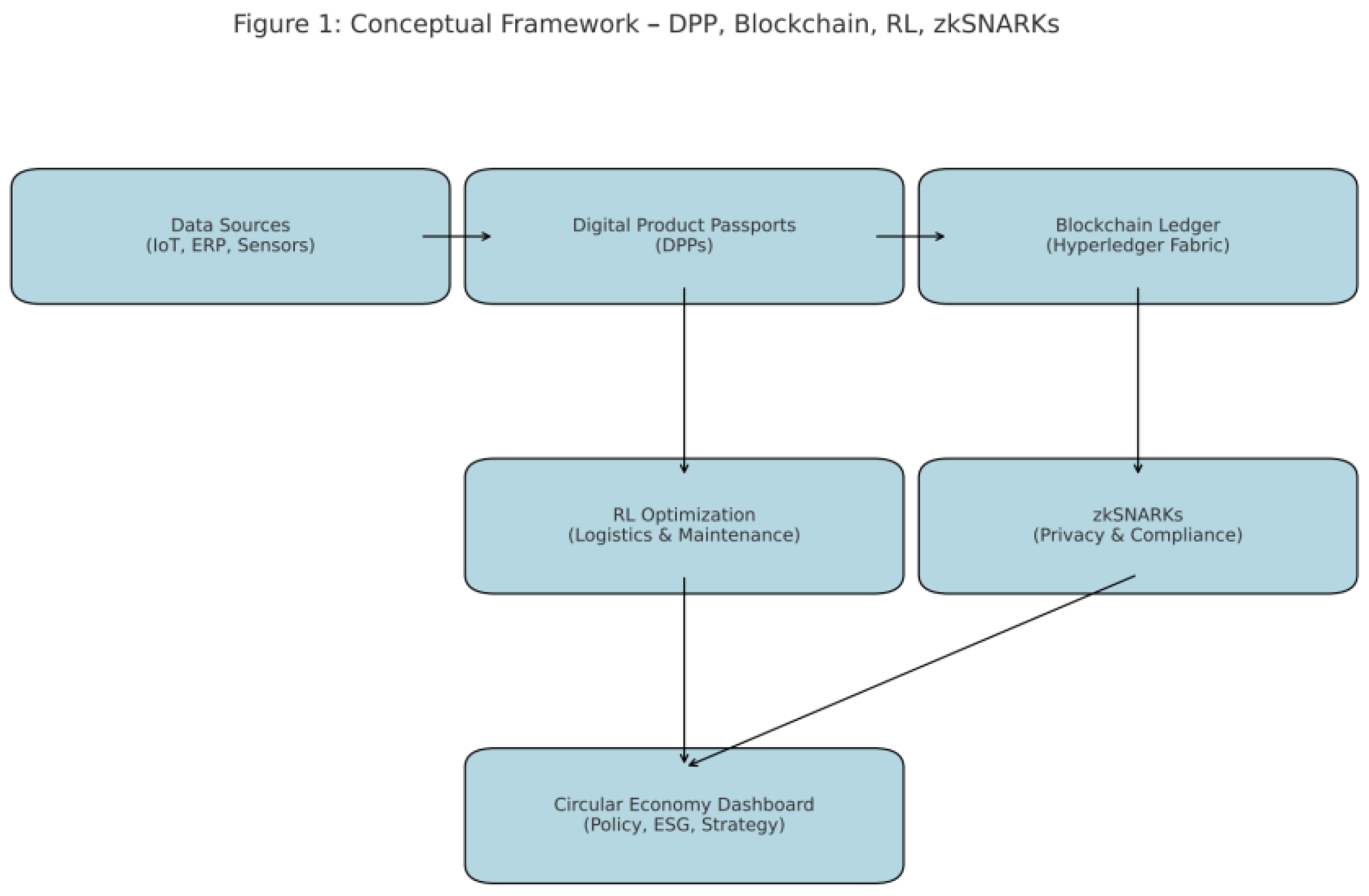

6. Integration Framework and Conceptual Model

The effective transformation of LIB and EV supply chains toward sustainability and transparency hinges on the synergistic integration of Digital Product Passports (DPPs) and blockchain technology. This integration provides a robust digital infrastructure that enables the secure, real-time exchange of lifecycle data across stakeholders, thereby enhancing circularity, accountability, and operational performance.

6.1. Synergistic Role of DPPs and Blockchain

DPPs serve as

data containers that capture the complete lifecycle history of LIBs and EV components. This includes sourcing information, manufacturing impacts, usage statistics, and end-of-life (EOL) pathways [

4]. For DPPs to function as trusted sources of truth, the data must be validated, tamper-proof, and securely shared across organizations with competing interests.

Here, blockchain technology provides the necessary infrastructure. Its decentralized and immutable architecture ensures that every DPP-related data transaction is:

Blockchain also supports interoperability between systems and stakeholders, facilitating a seamless flow of trusted information across supply chain tiers.

This integration enables a self-reinforcing digital ecosystem: DPPs provide the granular data, while blockchain ensures its trustworthiness. When applied together, these tools support traceability, resource optimization, and compliance with circular economy and ESG regulations.

6.2. System Architecture Overview

The integrated framework is composed of five interlinked modules:

-

Data Acquisition Layer

IoT sensors, RFID tags, and enterprise systems collect data on battery production, usage, and recycling.

-

Digital Product Passport Layer

Structures and stores detailed information on each component’s origin, performance, carbon footprint, and EOL status.

-

Blockchain Layer

Validates, timestamps, and stores DPP updates using a permissioned blockchain (e.g., Hyperledger Fabric) for auditability and trust.

-

Reinforcement Learning Layer

Applies predictive analytics to optimize logistics, maintenance schedules, and recycling operations using real-time DPP data.

-

Privacy and Security Layer

Implements zkSNARKs to verify data integrity while protecting sensitive business information [

13].

6.3. Conceptual Figure

Figure 4 illustrates the flow of data from the physical world (e.g., EV batteries in use) into digital systems that support decision-making and traceability through the integration of DPPs and blockchain.

6.4. Broader Implications

This framework is not limited to EVs. Its modularity and scalability make it applicable to other sectors requiring complex lifecycle tracking—such as electronics, aerospace, and renewable energy infrastructure. By enabling a trustworthy, intelligent, and transparent supply chain, the system directly supports:

Circular economy strategies

ESG reporting

Carbon footprint reduction

Extended product lifecycles

Regulatory compliance across jurisdictions

7. Challenges and Future Directions

While the integration of DPPs and blockchain technology in LIB and EV supply chains holds transformative potential, several technical, economic, and regulatory challenges must be addressed to enable broad adoption and long-term impact. This section outlines key barriers and proposes avenues for future research and policy development.

7.1. Data Standardization and Interoperability

Challenge: The lack of

standardized data formats, metadata schemas, and communication protocols across manufacturers, recyclers, and regulatory bodies hinders the seamless exchange of lifecycle information [

3]. Disparate systems and proprietary databases create silos, limiting the effectiveness of DPPs and undermining blockchain interoperability.

Proposed Solution/Future Research:

Develop open standards and APIs for DPP implementation through international industry alliances and policy coordination.

Explore semantic web technologies and ontology-based models for material composition, carbon metrics, and component traceability.

Encourage EU-style regulatory initiatives (e.g., Ecodesign for Sustainable Products Regulation) to mandate DPP compliance across sectors.

7.2. Blockchain Scalability and Energy Efficiency

Challenge: Mainstream blockchain networks face

scalability constraints, particularly in high-throughput environments like LIB and EV supply chains. Additionally, concerns remain regarding the

energy consumption of blockchain consensus mechanisms,

… especially in public or hybrid ledgers [

10].

Proposed Solution/Future Research:

Employ permissioned blockchain frameworks (e.g., Hyperledger Fabric, Corda) to reduce latency and energy use.

Investigate layer-2 scaling solutions and sharding for increasing throughput in blockchain-enabled DPP systems.

Integrate blockchain with edge computing to distribute processing closer to data sources, reducing bottlenecks and improving response times.

7.3. Cost Barriers and Implementation Complexity

Challenge: SMEs often lack the financial and technical resources to implement blockchain and DPP systems. Upfront costs for infrastructure, workforce training, and system integration pose significant adoption hurdles [

14].

Proposed Solution/Future Research:

Develop modular, low-cost DPP-blockchain toolkits tailored for SMEs.

Promote public-private partnerships and subsidies to support pilot deployments and training initiatives.

Quantify the long-term ROI of DPP adoption by modeling cost savings from reduced waste, improved logistics, and regulatory compliance.

7.4. Regulatory Uncertainty and Legal Harmonization

Challenge: The legal and regulatory frameworks governing digital product traceability, cross-border data exchange, and blockchain authentication remain

underdeveloped and fragmented. Differences in data privacy laws, IP protections, and liability standards create barriers to scale [

22].

Proposed Solution / Future Research:

Collaborate with international organizations (e.g., ISO, UNECE, WTO) to harmonize DPP and blockchain compliance standards.

Establish blockchain governance models for supply chain contexts, with clear protocols for dispute resolution, data ownership, and auditability.

Conduct legal-technical studies to align zkSNARK-based privacy mechanisms with evolving global data protection laws (e.g., GDPR, CCPA).

7.5. Future Research Directions

Integration of AI and blockchain for autonomous supply chain operations and decentralized decision-making [

19].

Design of incentive mechanisms for stakeholder participation in transparent data-sharing ecosystems.

Circularity metrics development within DPPs to assess environmental performance at the component and system levels.

Cross-sectoral DPP frameworks applicable beyond EVs—e.g., consumer electronics, aerospace, and industrial machinery.

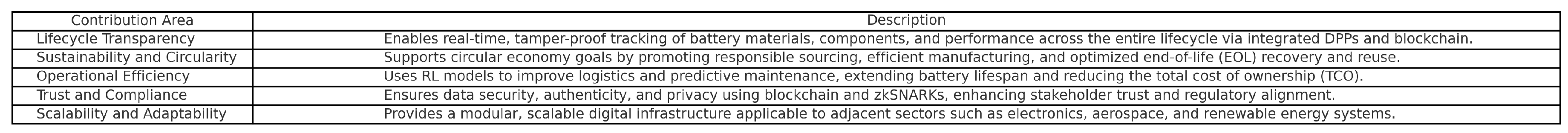

8. Expected Contributions

This research proposes a multi-layered digital framework combining Digital Product Passports (DPPs), blockchain, and reinforcement learning (RL) to address sustainability, transparency, and efficiency gaps in LIB and EV supply chains. The illustration below summarizes the expected contributions across technical, environmental, and operational domains.

Figure 5.

Summary of Expected Contributions.

Figure 5.

Summary of Expected Contributions.

9. Conclusions

The increasing complexity and sustainability demands of LIB and EV supply chains necessitate the adoption of intelligent, secure, and transparent lifecycle management systems. This paper presents an integrated framework that combines Digital Product Passports (DPPs), blockchain technology, and reinforcement learning (RL) to enhance traceability, improve operational efficiency, and support circular economy principles.

By leveraging DPPs for data richness, blockchain for immutable trust, and RL for predictive optimization, the proposed solution addresses critical challenges—ranging from ethical sourcing and counterfeiting to wasteful logistics and data silos. Moreover, the inclusion of privacy-preserving mechanisms such as zkSNARKs ensures that transparency does not compromise sensitive business information, a key requirement for enterprise-scale deployment.

The framework is scalable, adaptable, and cross-sectoral, making it suitable not only for EVs but also for other industries grappling with similar lifecycle and sustainability concerns. Policymakers can use this model to inform regulatory standards; businesses can enhance ESG performance and cost efficiency; and environmental goals can be advanced through more effective reuse, recycling, and resource optimization.

Ultimately, this research contributes to a novel, technologically grounded pathway for realizing sustainable, transparent, and intelligent supply chains in the era of digital industrial transformation.

Data Availability Statement

All data supporting the findings of this study are available within the article and its references. Simulation datasets (VRP instances) are publicly available at

https://zenodo.org/records/15296114.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflicts of interest.

References

- J. Baars, T. Domenech, R. Bleischwitz, H. E. Melin, and O. Heidrich, “Circular economy strategies for electric vehicle batteries reduce reliance on raw materials,” Nat. Sustain., 2020. [CrossRef]

- J. Bagraff, T. Schmidt, and D. Müller, “Blockchain-based traceability for ethical sourcing in battery supply chains,” IEEE Trans. Sustain. Comput., vol. 9, no. 1, pp. 45–58, 2024.

- M. Balcıoğlu, A. Karcı, and E. Demir, “Interoperability challenges in blockchain-based supply chains,” Inf. Syst. Front., vol. 26, no. 2, pp. 345–360, 2024.

- M. Berger, M. Pfaff, and J. P. Schöggl, “Digital product passports as enablers of circular economy in the EV battery sector,” J. Ind. Ecol., vol. 26, no. 4, pp. 789–802, 2022.

- N. Bernards, E. Morgera, and S. Geenen, “The dark side of green mining: Environmental and human rights impacts of lithium extraction,” Resour. Policy, vol. 78, 102876, 2022.

- B. Bhawna, P. Kaur, and N. Singh, “Sustainable EV supply chains: The role of digital product passports and blockchain,” Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev., vol. 189, 113987, 2024.

- X. Chen, Y. Zhang, and L. Wang, “Challenges and opportunities in lithium-ion battery supply chains for electric vehicles,” J. Clean. Prod., vol. 45, no. 3, pp. 112–125, 2024.

- M. Faisal, S. Khan, and K. Abbas, “Blockchain adoption for sustainable supply chains: Cost-benefit analysis,” Technol. Forecast. Soc. Change, vol. 198, 122987, 2024.

- S. Hemavathi and A. Shinisha, “A study on trends and developments in electric vehicle charging technologies,” J. Energy Storage, 2022. [CrossRef]

- P. Kumar, S. Singh, and A. Mishra, “Scalability solutions for blockchain in EV supply chains,” Future Gener. Comput. Syst., vol. 150, pp. 450–465, 2024.

- W. Li, X. Zhao, and J. Liu, “Forward-reverse blockchain traceability for EV battery recycling,” Resour. Conserv. Recycl., vol. 198, 107201, 2024.

- Y. Liu, H. Zhang, and G. Chen, “Blockchain-based pharmaceutical traceability: Lessons for EV battery supply chains,” Comput. Ind. Eng., vol. 185, 109678, 2024.

- S. Malik, V. Dedeoglu, S. Kanhere, and R. Jurdak, “PrivChain: Provenance and privacy preservation in blockchain-enabled supply chains,” IEEE Int. Conf. Blockchain, pp. 157–166, 2021. [CrossRef]

- H. Mbaidin, T. Al-Hawari, and H. Alzoubi, “Cost barriers in blockchain adoption for supply chain transparency,” Int. J. Prod. Econ., vol. 265, 109012, 2023.

- T. Mukunde, “Blockchain applications in sustainable supply chain management,” Int. J. Logist. Manag., vol. 35, no. 1, pp. 89–104, 2024.

- O. Nwariaku, A. Adeleke, and C. Okoli, “Decentralized ledger systems for ethical mineral sourcing in Africa,” Blockchain Res. Appl., vol. 5, no. 1, 100023, 2024.

- Protokol, “Digital Product Passport: Complete Guide,” 2024. Available: https://www.protokol.com/insights/digital-product-passport-complete-guide/.

- P. Rapezzi, M. Rossi, and F. Bianchi, “Blockchain-enhanced transparency and consumer trust in sustainable supply chains,” Sustainability, vol. 16, no. 2, 567, 2024.

- K. Reddy, “AI and blockchain convergence for smart supply chains,” Artif. Intell. Rev., vol. 55, no. 6, pp. 4567–4590, 2022.

- S. Sahai, N. Singh, and P. Dayama, “Enabling privacy and traceability in supply chains using blockchain and zero knowledge proofs,” IEEE Int. Conf. Blockchain, pp. 134–143, 2020. [CrossRef]

- M. Saleh, “Secure data sharing in EV battery lifecycle management using blockchain,” J. Cybersecur., vol. 10, no. 1, tyad012, 2024.

- R. Sharma, T. Kim, and J. Park, “Regulatory frameworks for blockchain in sustainable supply chains,” J. Environ. Manag., vol. 351, 119876, 2024.

- P. Singh, R. Kumar, and A. Sharma, “Transparency gaps in electric vehicle supply chains: A critical review,” Sustain. Prod. Consum., vol. 35, pp. 567–582, 2023.

- D. Singhal, S. Gupta, and R. Patel, “Energy and water footprint tracking in battery manufacturing using digital twins,” Appl. Energy, vol. 342, 121034, 2024.

- M. Slattery, J. Dunn, and A. Kendall, “Transportation of electric vehicle lithium-ion batteries at end-of-life: A literature review,” Resour. Conserv. Recycl., 2021. [CrossRef]

- A. Sobowale, O. Oladipupo, and A. Adeyemi, “Anti-counterfeiting in battery supply chains via blockchain authentication,” IEEE Access, vol. 12, pp. 12345–12356, 2024.

- L. Stopfer, C. Meinel, and T. Bauernhansl, “Provenance tracking of conflict minerals using blockchain,” J. Bus. Ethics, vol. 180, no. 3, pp. 501–518, 2024.

- M. Umer, L. Gouveia, and E. Belay, “Provenance blockchain for ensuring IT security in cloud manufacturing,” Front. Blockchain, 2023. [CrossRef]

- H. Yang and Y. Wang, “End-of-life management of lithium-ion batteries: Recycling and sustainability challenges,” Waste Manag., vol. 156, pp. 12–24, 2024.

- L. Zhen and Y. Yao, “Digital twin and blockchain integration for sustainable supply chains,” Transp. Res. Part E Logist. Transp. Rev., vol. 181, 103355, 2024.

- M. V. Reddy, A. Mauger, K. Zaghib, et al., “Brief History of Early Lithium-Battery Development,” *Materials*, vol. 13, no. 8, 1884, 2020. [CrossRef]

- S. M. Habibullah, A. U. Rahman, H. A. Khan, et al., “Blockchain-based energy consumption approaches in IoT: Survey and comparative analysis,” *Scientific Reports*, vol. 14, 77792, 2024. [CrossRef]

- B. Gülmez, M. Emmerich, and Y. Fan, “Multiple time window VRP dataset,” Zenodo, Apr. 2025. Available: https://zenodo.org/records/15296114?utm_source=chatgpt.com.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).