1. Introduction

Human Herpes Simplex Virus 1 (HSV-1) stands as a testament to viral persistence and a formidable challenge to public health [

1,

2]. This ubiquitous pathogen has infected a majority of the global population, causing a wide spectrum of clinical diseases that extend far beyond simple cold sores [

1,

2]. Its manifestations include painful and recurrent oral lesions, potentially blinding herpetic keratitis, and life-threatening encephalitis, with particularly devastating outcomes in neonates and immunocompromised individuals [

3]. Beyond the physical symptoms, the virus imposes a significant psychological burden due to its lifelong persistence and the unpredictable nature of its reactivation [

4,

5]. At the core of this challenge is the virus's ability to establish a state of latency, hiding as a silent episome within the nuclei of sensory neurons, completely shielded from both the host immune system and current antiviral therapies [

6,

7].

The development of nucleoside analogs, with acyclovir as the prototype, marked a revolutionary advance in the management of HSV infections [

8,

9]. These drugs function as chain terminators for the viral DNA polymerase, effectively halting viral replication during active lytic cycles [

10,

11]. The clinical success of this drug class in controlling the severity and duration of recurrent episodes is undeniable. However, the acyclovir era has reached its therapeutic ceiling [

12,

13]. The fundamental limitation of these drugs is their complete inability to target the latent viral reservoir, meaning they can manage symptoms but can never provide a cure [

14,

15]. Furthermore, decades of clinical use have led to the inevitable emergence of drug-resistant viral strains, particularly in immunocompromised patients, where mutations in the viral thymidine kinase or DNA polymerase render the drugs ineffective [

16]. This combination of an inaccessible latent reservoir and growing drug resistance creates a clear and urgent unmet medical need for a new generation of anti-herpetic agents that operate through entirely novel mechanisms of action.

In recent years, the field of drug discovery has been transformed by the rise of Targeted Protein Degradation (TPD) [

17]. This innovative modality seeks not just to inhibit a target protein, but to eliminate it from the cell entirely [

17,

18]. The flagship technology of TPD is the Proteolysis-Targeting Chimera (PROTAC), a bifunctional molecule designed to hijack the cell's own quality control machinery, the Ubiquitin-Proteasome System (UPS) [

17,

19]. By simultaneously binding a Protein of Interest (POI) and a cellular E3 ubiquitin ligase—one of over 600 enzymes responsible for substrate recognition within the UPS—a PROTAC induces the formation of a temporary ternary complex [

19,

20]. This induced proximity enables the E3 ligase to tag the POI with a polyubiquitin chain, marking it for destruction by the proteasome. The catalytic nature of this process, where one PROTAC molecule can trigger the degradation of many target molecules, has established TPD as a powerful therapeutic strategy, with several PROTACs now advancing through clinical trials for cancer and other diseases [

17].

While TPD has proven its value against human protein targets, its application to infectious diseases, particularly virology, represents a new and exciting frontier. The concept of degrading an essential viral protein, rather than merely blocking its active site, is therapeutically compelling and could lead to more profound and durable antiviral effects [

21,

22]. This study aims to forge a path in this direction by targeting Infected Cell Protein 0 (ICP0) of HSV-1, a protein that can be justifiably described as the master saboteur of the host cell. As an immediate-early (IE) protein, ICP0 is one of the very first viral products to appear, and it immediately executes a multi-pronged assault to dismantle cellular defenses [

23,

24]. Its power is derived from its function as a C3HC4 RING finger E3 ubiquitin ligase, a molecular weapon it wields with devastating efficiency [

24,

25,

26]. ICP0's "hit list" comprises a strategic collection of proteins central to the host's antiviral response [

27,

28].

Given its absolute centrality to viral pathogenesis, ICP0 is an outstanding therapeutic target. This study puts forth a novel strategy to neutralize it: the design of a first-in-class homoPROTAC. This molecule is engineered with two distinct warheads designed to bind to two separate allosteric sites on the ICP0 protein. Our central hypothesis is that this bivalent binding will leverage the natural tendency of ICP0 to self-associate via its C-terminal dimerization domain [

23], inducing the formation of a stable ICP0–homoPROTAC–ICP0 ternary complex. Within this enforced dimer, the potent E3 ligase domain of one ICP0 molecule will be ideally positioned to catalyze the ubiquitination and subsequent degradation of its partner. This "viral self-destruction" paradigm is fundamentally different from conventional PROTACs as it obviates the need to recruit a host E3 ligase, promising exceptional specificity to infected cells. The objective of this work is to provide the first computational proof-of-concept for this strategy, employing a sophisticated pipeline of AI-driven drug design tools to rationally design and validate these novel antiviral agents.

2. Results

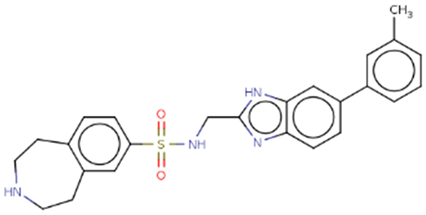

2.1. ICP0 Structural Analysis Reveals a Superior Druggable Pocket for Bivalent Ligand Design

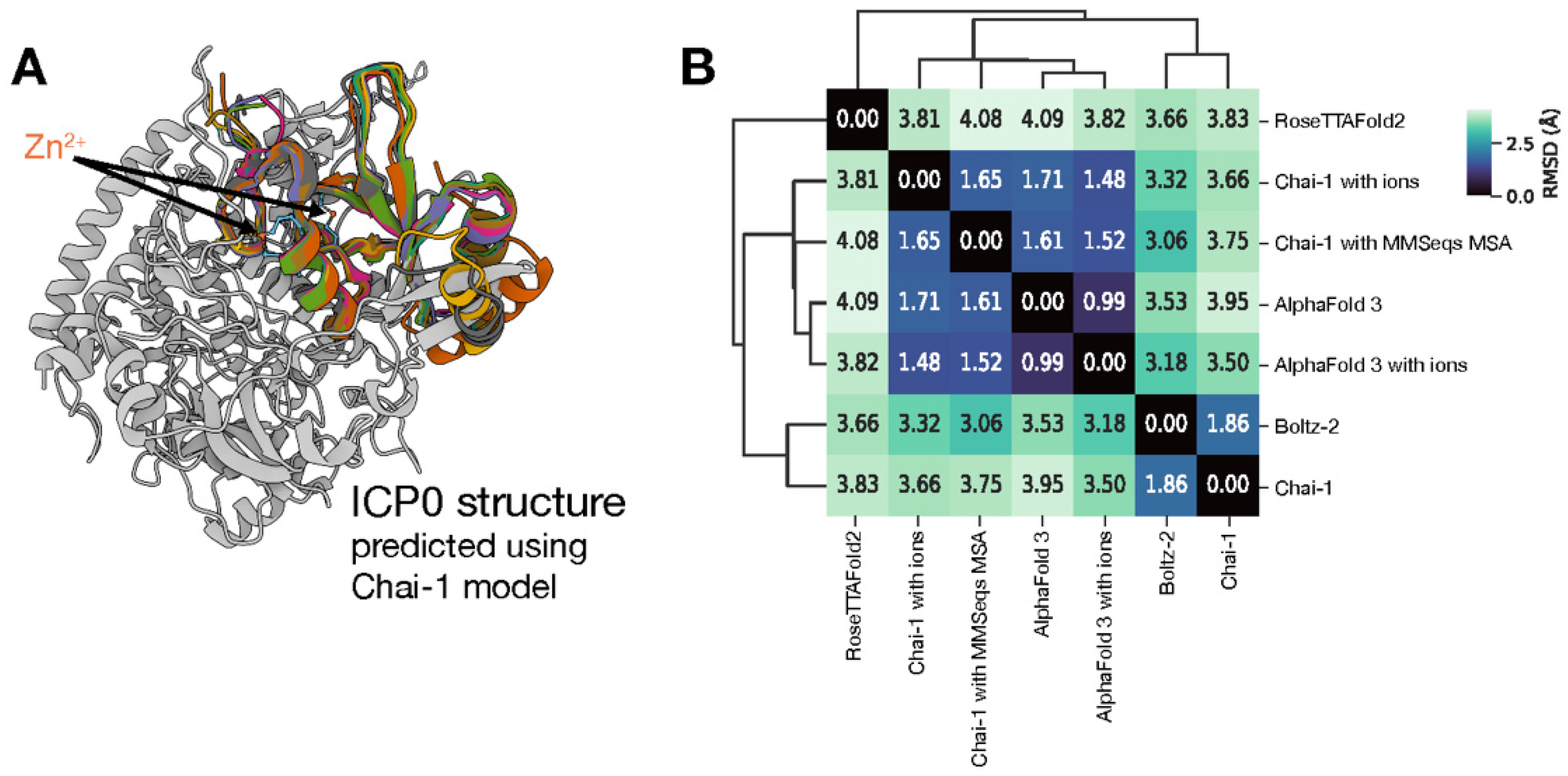

To establish a reliable three-dimensional structure for ICP0, a comparative analysis of models from multiple state-of-the-art AI platforms, including AlphaFold 3 and RoseTTAFold2, was performed (

Figure 1a). While these other tools were used for comparison and to build confidence in the overall fold, the Chai-1 model with an explicitly modeled zinc ion was selected as the definitive structure for all subsequent computational applications (

Figure 1b). The selected Chai-1 model yielded a predicted TM-score (pTM) of 0.26 and an interface pTM (ipTM) of 0.12. This low global confidence is largely attributable to the presence of extensive random coils, corresponding to predicted intrinsically disordered regions in the full-length protein. However, the functionally critical region encompassing the RING finger domain (residues 110-200) was consistently predicted with high local confidence across all models, validating its structural integrity for further analysis.

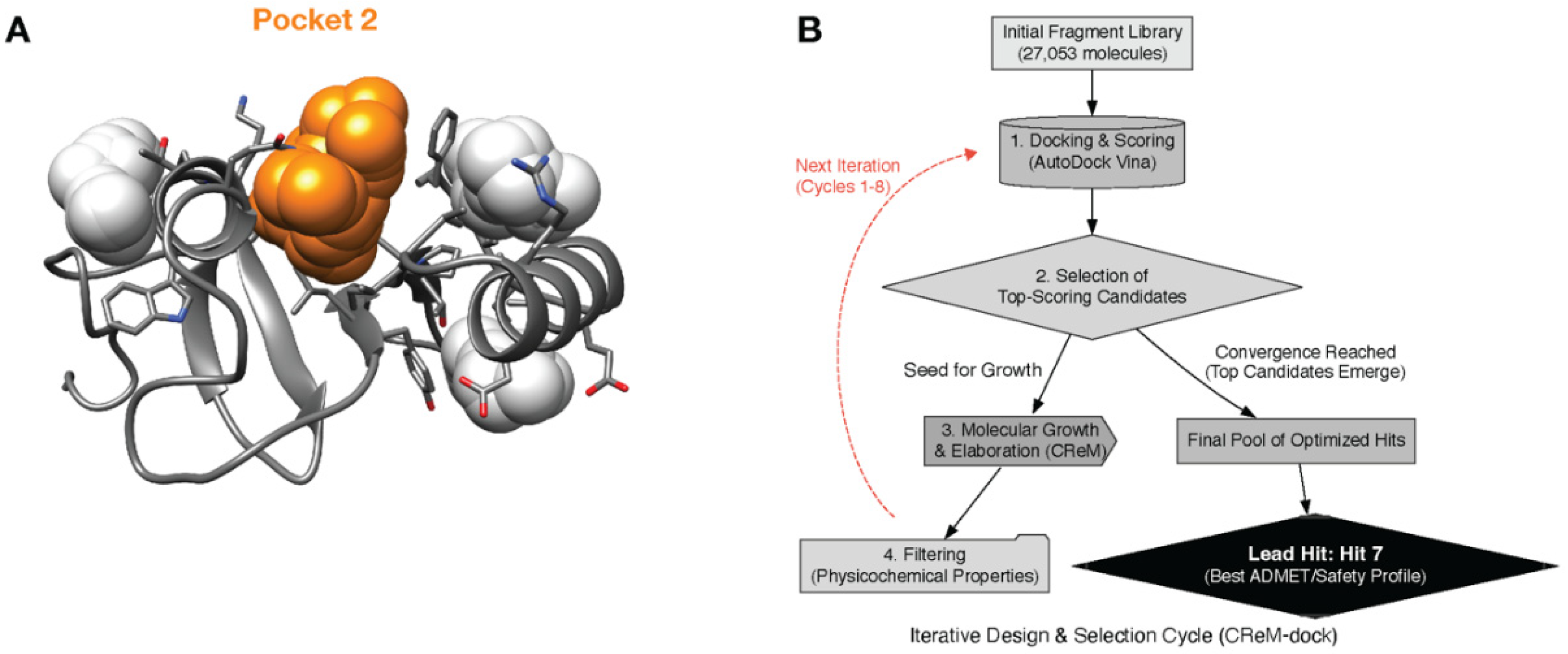

Subsequent druggability analysis performed on this Chai-1 model identified several potential binding cavities on the protein surface. A quantitative comparison revealed that one of these sites was vastly superior, exhibiting the highest druggability score (0.215) and the largest volume (617 ų) (

Table 1). This single, high-quality pocket, visualized in

Figure 2a, was consequently selected as the exclusive target for all subsequent hit generation and degrader design efforts.

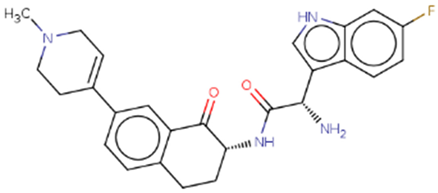

2.2. Fragment Screening Identifies High-Affinity Core Scaffolds

The de novo design of novel scaffolds was conducted using an iterative CReM-dock workflow that completed 8 cycles of molecular docking, generation, and filtering (

Figure 2b). The screening began with an initial library of 27,053 fragments. In the first iteration, this pool was docked, and the best candidates were elaborated, massively expanding the chemical space to over 124,000 new molecules that passed physicochemical filters.

Over the following seven iterations, the process computationally evaluated and refined this chemical space. The number of candidate molecules was progressively focused down, from the initial expansion to 26,793 candidates in iteration 2, then to 1,606 in iteration 3, and ultimately to a final pool of 73 molecules entering the last cycle. In total, approximately 182,000 unique docking calculations were performed throughout the campaign. The generative process automatically concluded after the eighth iteration when no further valid chemical elaborations could be produced from the remaining candidates, indicating that the algorithm had reached convergence.

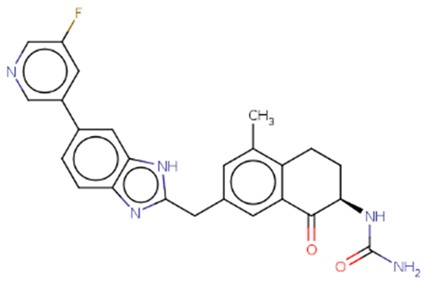

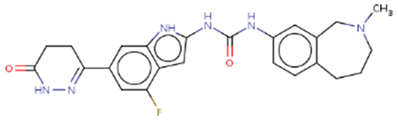

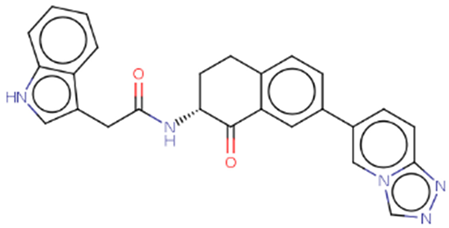

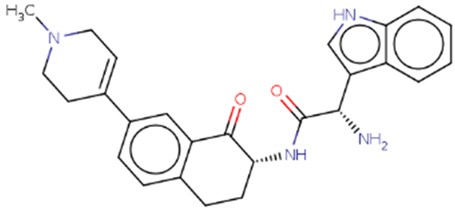

From the final pool of high-scoring molecules generated by this extensive campaign, the top candidates were subjected to a rigorous ADMET and physicochemical analysis to identify the single most promising scaffold for elaboration (

Table 2). Based on this comprehensive assessment, Hit 7 was selected as the lead scaffold, primarily due to its superior predicted aqueous solubility and its minimal predicted inhibition of cytochrome P450 enzymes.

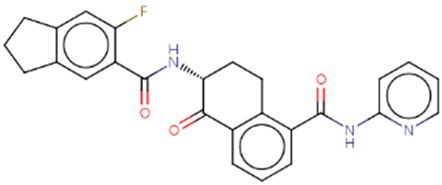

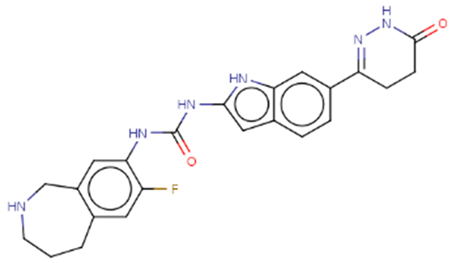

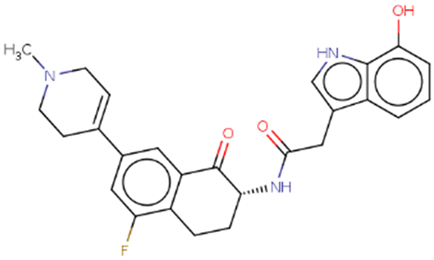

2.3. Rational Design of the Lead Bivalent Degrader ICP0-deg-01

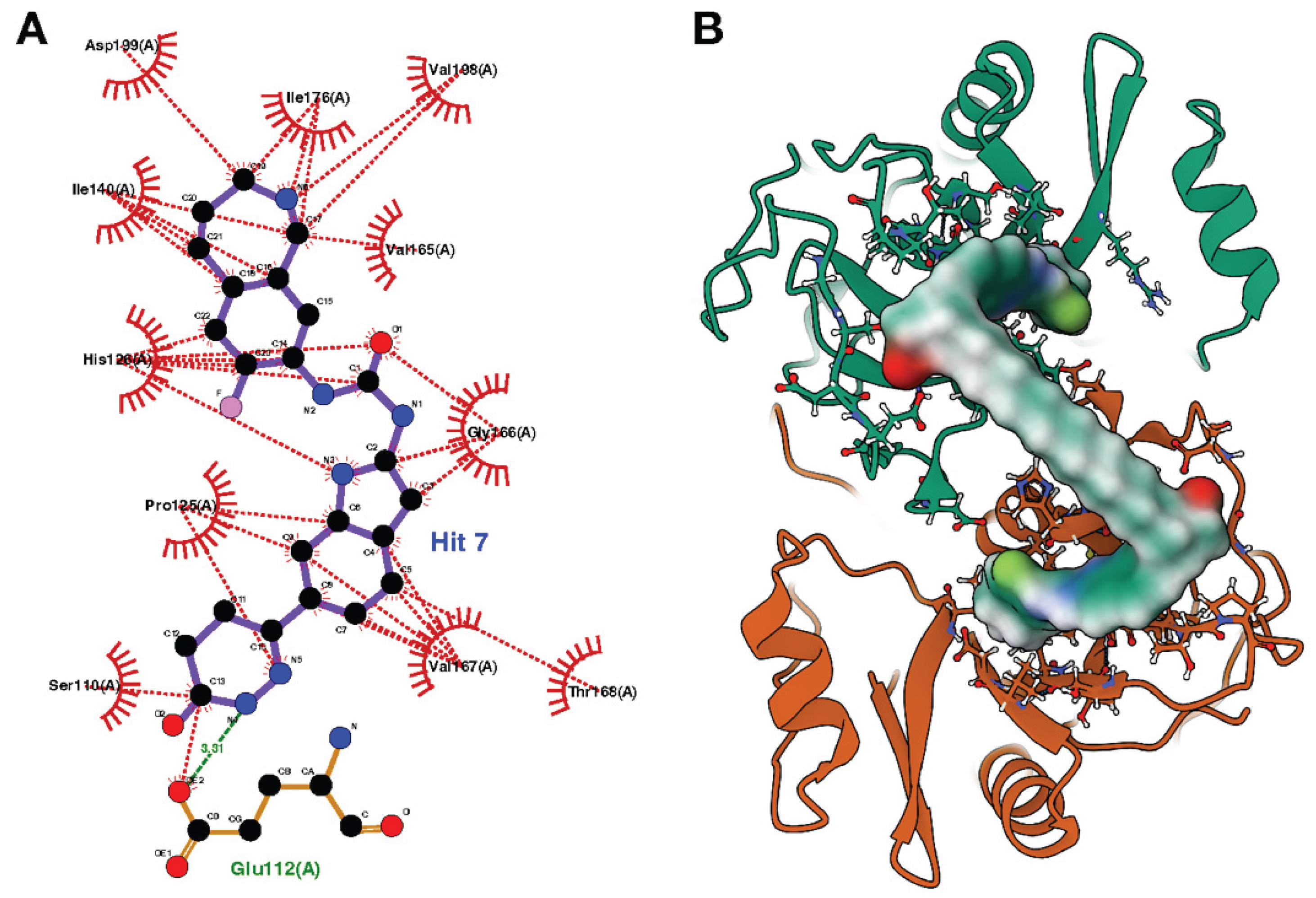

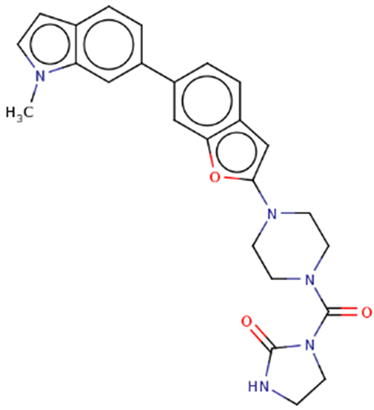

Using the lead scaffold Hit 7 as the exclusive "warhead," a single, final bivalent degrader—designated ICP0-deg-01—was rationally designed. This was achieved by docking two copies of the Hit 7 warhead into the identical target sites of the ICP0 dimer model and computationally connecting them with a 16-carbon alkyl linker.

The resulting ternary complex model shows how ICP0-deg-01 effectively bridges the two ICP0 protomers (colored orange and green) at the dimer interface. As shown in the detailed interaction map (

Figure 3a), each "Hit 7" warhead is deeply anchored within its respective pocket through a network of favorable interactions. These include key hydrogen bonds with the side chain of Glu112, as well as extensive hydrophobic contacts with residues such as Ile140, Val165, and Val167. The flexible 16-carbon linker successfully spans the distance between the two bound warheads, creating a stable, bridged structure evaluated as the lead candidate for this study (

Figure 3b).

3. Discussion

This in silico investigation has successfully delineated a rational computational strategy for the design of a first-in-class homoPROTAC against the essential HSV-1 protein, ICP0. By integrating state-of-the-art AI-driven structure prediction with a generative molecular design workflow, we identified a novel, superior druggable pocket on ICP0. This led to the identification of a lead hit scaffold, Hit 7, and the subsequent design of a single bivalent degrader candidate, ICP0-deg-01. Our structural model provides a robust, hypothesis-generating blueprint, predicting that ICP0-deg-01 can effectively bridge two ICP0 protomers, laying the groundwork for a new "viral self-destruction" therapeutic paradigm.

The strategic selection of ICP0 as the target is central to the therapeutic hypothesis. As a master regulator of the infectious cycle, the degradation of ICP0 would represent a catastrophic failure for the virus, crippling its ability to dismantle host defenses and replicate [

29]. A particularly profound implication of this strategy is its potential to address the challenge of viral latency. A growing body of evidence suggests that latency is a dynamic state maintained by low-level, intermittent ICP0 expression [

30]. Therefore, a therapeutic agent capable of eliminating the ICP0 protein could potentially extinguish the latent reservoir, preventing reactivation—a goal that has remained elusive for current antiviral therapies.

The "viral self-destruction" model itself offers significant advantages. By hijacking the viral E3 ligase to degrade itself, the mechanism is inherently specific to infected cells expressing ICP0, promising a wide therapeutic window. This novel mechanism of action is also critically important for combating the emergence of drug resistance that plagues current treatments like acyclovir. Our study moves beyond simple inhibition to propose a catalytic method of viral protein elimination.

Our computational workflow highlights the power of modern drug design tools. The iterative CReM-dock process was highly effective, exploring a vast chemical space through approximately 182,000 docking calculations over 8 iterations to identify novel scaffolds. The subsequent selection of Hit 7 was a deliberate, multi-parameter optimization, balancing a strong predicted binding affinity with a superior ADMET/safety profile. The final structural model of the ICP0-deg-01 ternary complex provides a detailed hypothesis for how this induced dimerization is achieved. The model predicts that the Hit 7 warheads are anchored by a network of specific hydrogen bonds and hydrophobic interactions, while the 16-carbon linker is of sufficient length to bridge the two protomers in an energetically favorable conformation.

While this study provides a strong computational proof-of-concept, its significant limitations must be clearly acknowledged. The most fundamental weakness is the study's reliance on an AI-generated structural model, particularly for the dimer interface that is central to the proposed mechanism. Furthermore, the absence of molecular dynamics simulations means that the stability and dynamic behavior of the final complex are purely hypothetical. The therapeutic design was also simplified, using only a single hit scaffold and a single, non-optimized 16-carbon linker where a more comprehensive study would have explored a wider chemical space. The entire study is computational, and all findings require rigorous experimental validation to be substantiated.

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. ICP0 Sequence Acquisition and AI-Driven Structural Prediction

The canonical protein sequence for Human Herpes Simplex Virus 1 (strain 17) ICP0 was acquired from the UniProt Knowledgebase (UniProt ID: P08393) [

31]. As no complete experimental structure exists, a comprehensive in silico modeling approach was undertaken. A diverse pool of three-dimensional (3D) models of the full-length 775-amino acid protein was generated using multiple state-of-the-art AI-driven protein structure prediction platforms: AlphaFold-3 [

32], Boltz-2 [

33], Chai-1 [

34], Protenix [

35], and RoseTTAFold2 [

36]. Notably, models from the AlphaFold Server and its derivatives were intentionally excluded from our workflow. This decision was made to ensure full compliance with its terms of use, which restricts the use of its output in conjunction with automated docking programs like AutoDock Vina, a key component of our study. From this pool, a final consensus model was selected by prioritizing models with both a high mean predicted Local Distance Difference Test (pLDDT) score and, critically, a chemically correct and functionally competent C3HC4 RING finger domain [

24]. This involved meticulous validation of the coordination geometry of the two explicitly modeled zinc (Zn2+) ions with the surrounding Cys/His residues. While the catalytic C3HC4 RING finger domain is defined as residues 116-156, we selected a larger fragment (residues 110-200) for all subsequent analyses. This expanded boundary was chosen to fully incorporate the functional domain and to account for the potential influence of adjacent, flexible regions on ligand accessibility and binding.

4.2. Druggability Analysis and Site Selection

To enable the bivalent degrader strategy, the selected ICP0 model was intensively analyzed to identify the most suitable druggable binding pocket. While initial interest was focused on the catalytic RING domain, analysis of the full-length model revealed more promising allosteric sites. The entire structure was subjected to a rigorous computational pipeline using three independent pocket detection algorithms: fpocket 4.0, P2Rank 2.3, and KVFinder 3.0. These algorithms generated quantitative metrics (e.g., Druggability Score, Volume, Polarity) for all potential cavities. Based on a consensus of these metrics, one particular pocket was identified as having a vastly superior druggability score and volume, making it the ideal candidate for binding a small molecule warhead and for mediating dimerization. This pocket was selected for the subsequent virtual screening.

4.3. Fragment Library Preparation

To construct a high-quality library suitable for fragment-based virtual screening, a comprehensive collection of small molecules was assembled and meticulously refined. The foundation of this library was built upon three distinct sources. The first was the entirety of the DrugBank database, which was initially filtered to retain all carbon-containing molecules with a molecular mass exceeding 50 Daltons. This was augmented with a curated set of sp3-rich fragments from the CReM database and a specialized subset of the ChEMBL database (version 22), which was pre-filtered for a low heavy atom count.

Following aggregation, this composite library was subjected to a rigorous computational filtering cascade designed to ensure the selection of synthetically feasible and medicinally relevant starting points. The chemical space was first constrained to molecules composed exclusively of common organic elements, namely carbon, nitrogen, oxygen, sulfur, phosphorus, and the halogens fluorine, chlorine, bromine, and iodine. To adhere to the principles of fragment-based design, a stringent upper limit of 12 heavy atoms per molecule was imposed. Furthermore, to prioritize compounds amenable to straightforward chemical synthesis, a maximum synthetic accessibility (SA) score of 2.5 was enforced. As a final quality control measure, the library was purified of known promiscuous binders, nuisance compounds, and reactive functionalities by removing any molecule that triggered an alert from a suite of well-established medicinal chemistry filters, including the BMS, Dundee, Glaxo, and Inpharmatica rules, as well as the Pan-Assay Interference Compounds (PAINS) filter set. The resulting curated fragment library therefore represented a collection of small, synthetically accessible, and medicinally relevant scaffolds poised for the subsequent virtual screening campaign.

4.4. Fragment Screening and Hit Identification

To identify novel and potent chemical scaffolds, a de novo design strategy was employed using the CReM-dock software in its "Hit generation" mode. The process was initiated with a library containing 27,802 chemical fragments. In a fully automated and iterative workflow, these fragments were first docked into the prioritized ICP0 target pocket using the AutoDock Vina algorithm. The protonation states of all molecules were assigned at a physiological pH using molgpka, and all docking parameters were specified in a dedicated Vina configuration file.

Following the initial docking, the most promising fragments were selected as seeds for chemical elaboration. The CReM-dock pipeline then systematically generated new, chemically reasonable molecules by growing and modifying these seeds in subsequent iterations. This generative process was guided by an objective function prioritizing docking efficiency, ensuring that each new generation of molecules was progressively optimized for binding. Throughout the campaign, defined thresholds for key physicochemical parameters were enforced to maintain drug-like properties in the generated compounds. This entire high-throughput process was executed in parallel on a 32-core system. The final output was a set of novel, optimized molecules, ranked by their predicted binding affinity (ΔG in kcal/mol), which served as high-quality "hits" for the subsequent design of bivalent degraders.

4.5. Hit Elaboration and Bivalent Degrader Design

Following the identification of novel chemical scaffolds, a focused, structure-based approach was employed to construct the final bivalent degrader. The single, top-ranked fragment hit from the generative design process was selected to serve as the "warhead" for the chimera. A structural model of a functionally critical ICP0 dimer, encompassing residues 1-388 and thus including both the RING finger and PML degradation domains, was generated using the Chai-1 AI-driven protein structure prediction platform. Two copies of the selected warhead were then docked into the two identical target pockets on this dimer model using AutoDock Vina to determine their optimal binding poses. To form the final bivalent degrader, these two optimally positioned warheads were computationally connected using a flexible 16-carbon alkyl linker. This procedure yielded a single, rationally designed bivalent degrader, and the resulting model of its ternary complex (ICP0–Degrader–ICP0) was advanced for further evaluation.

4.6. ADMET Prediction

To ensure the selection of a high-quality starting point and to characterize the final candidate, a multi-stage ADMET analysis was performed. First, the initial pool of generated fragment hits was evaluated for drug-like properties, allowing us to select the top-ranked scaffold for elaboration based on both its binding affinity and its favorable physicochemical characteristics.

Subsequently, the single, final bivalent degrader was assessed for its predicted ADMET (Absorption, Distribution, Metabolism, Excretion, and Toxicity) profile. This characterization was performed using the SwissADME and Deep-PK web servers. A comprehensive set of parameters was evaluated, including predicted aqueous solubility (LogS), blood-brain barrier permeability (LogBB), and potential toxicological flags like the AMES test. This final analysis served to characterize our sole lead candidate and confirm its suitability before proceeding with more rigorous validation.

4.7. Structural Visualization

Three-dimensional representations of proteins and complexes shown in the figures were visualized and rendered using UCSF Chimera v.1.19 [

37] and Mol* [

38]. Two-dimensional diagrams detailing protein-ligand interactions were generated using the LigPlot+ v.2.2 [

39] program.

5. Conclusions

This in silico investigation has described a scalable computational strategy for the rational design of the first-in-class homoPROTAC targeting the essential HSV-1 E3 ligase ICP0. Our workflow, which combines AI-driven structure prediction with an iterative generative design process, successfully identified a superior druggable pocket on ICP0 and yielded a lead candidate, ICP0-deg-01, with structural features that would cause the viral ICP0 to self-destruct. This work establishes a solid computational foundation for a new class of antiviral therapeutics designed to address the dual challenge of drug resistance and viral latency. In conclusion, this study is a demonstration of the convergence of molecular virology and modern computational chemistry. It proposes and provides a model for a paradigm of “viral self-destruction” that may be transferable to other persistent pathogens and heralds a new approach to rational antiviral design.

Author Contributions

L.S. conceived the study and designed the computational workflow; L.S., A.S., M.E.S., and Z.B.S. performed the virtual screening and docking calculations; O.A., L.S., F.H.K.B., and S.A. were responsible for data curation and analysis; M.G.K., S.A., and H.B. supervised the project and provided critical insights. All authors contributed to the writing and editing of the manuscript and have approved the final version.

Data Availability Statement

The data that supports the findings of this study, including the final protein model and docking results, are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| HSV-1 |

Human Herpes Simplex Virus 1 |

| TPD |

Targeted Protein Degradation |

| PROTAC |

Proteolysis-Targeting Chimera |

| UPS |

Ubiquitin-Proteasome System |

| ADMET |

Absorption, Distribution, Metabolism, Excretion, and Toxicity |

| RMSD |

Root Mean Square Deviation |

| ICP |

Infected Cell Protein |

References

- James, C.; Harfouche, M.; Welton, N.J.; Turner, K.M.; Abu-Raddad, L.J.; Gottlieb, S.L.; Looker, K.J. Herpes Simplex Virus: Global Infection Prevalence and Incidence Estimates, 2016. Bull. World Health Organ, 2020, 98, 315–329. [CrossRef]

- Su, D.; Han, Liping; Shi, Chengyu; Li, Yaoxin; Qian, Shaoju; Feng, Zhiwei; and Yu, L. An Updated Review of HSV-1 Infection-Associated Diseases and Treatment, Vaccine Development, and Vector Therapy Application. Virulence, 2024, 15, 2425744. [CrossRef]

- Riley, G.; Cloete, E.; Walls, T. Challenges of Timely Investigation and Treatment of Neonatal Herpes Simplex Virus Infection. J. Paediatr. Child Health, 2023, 59, 385–388. [CrossRef]

- Oh, J.J.; Jaggi, U.; Tormanen, K.; Wang, S.; Hirose, S.; Ghiasi, H. The Anti-Apoptotic Function of HSV-1 LAT in Neuronal Cell Cultures but Not Its Function during Reactivation Correlates with Expression of Two Small Non-Coding RNAs, sncRNA1&2. PLOS Pathog, 2024, 20, e1012307. [CrossRef]

- Dochnal, S.A.; Krakowiak, P.A.; Whitford, A.L.; Cliffe, A.R. Physiological Oxygen Concentration during Sympathetic Primary Neuron Culture Improves Neuronal Health and Reduces HSV-1 Reactivation. Microbiol. Spectr, 2024, 12, e02031-24. [CrossRef]

- Grams, T.R.; Edwards, T.G.; Bloom, D.C. A Viral lncRNA Tethers HSV-1 Genomes at the Nuclear Periphery to Establish Viral Latency. J. Virol, 2023, 97, e01438-23. [CrossRef]

- Bautista, L.; Sirimanotham, C.; Espinoza, J.; Cheng, D.; Tay, S.; Drayman, N. A Drug Repurposing Screen Identifies Decitabine as an HSV-1 Antiviral. Microbiol. Spectr, 2024, 12, e01754-24. [CrossRef]

- Gosavi, A.A.; Thorat, P.A.; Mulla, J.A.S. Formulation and Evaluation of Acyclovir Loaded Transferosomal Gel for Transdermal Drug Delivery. J. Drug Deliv. Ther, 2024, 14, 122–130. [CrossRef]

- Spataro, F.; Ria, R.; Choul, N.; Vacca, A.; Solimando, A.G.; Girolamo, A.D. Acyclovir Desensitization. A Case Report and a Review of Desensitization Strategies. J. Infect. Dev. Ctries, 2025, 19, 174–180. [CrossRef]

- Kawsar, S.M.A.; Munia, N.S.; Saha, S.; Ozeki, Y. In Silico Pharmacokinetics, Molecular Docking and Molecular Dynamics Simulation Studies of Nucleoside Analogs for Drug Discovery- A Mini Review. Mini-Rev. Med. Chem, 2024, 24, 1070–1088. [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.; Knafels, J.D.; Chang, J.S.; Waszak, G.A.; Baldwin, E.T.; Deibel, M.R.; Thomsen, D.R.; Homa, F.L.; Wells, P.A.; Tory, M.C.; et al. Crystal Structure of the Herpes Simplex Virus 1 DNA Polymerase. J. Biol. Chem, 2006, 281, 18193–18200. [CrossRef]

- Álvarez, D.M.; Castillo, E.; Duarte, L.F.; Arriagada, J.; Corrales, N.; Farías, M.A.; Henríquez, A.; Agurto-Muñoz, C.; González, P.A. Current Antivirals and Novel Botanical Molecules Interfering With Herpes Simplex Virus Infection. Front. Microbiol, 2020, 11. [CrossRef]

- Birkmann, A.; Bonsmann, S.; Kropeit, D.; Pfaff, T.; Rangaraju, M.; Sumner, M.; Timmler, B.; Zimmermann, H.; Buschmann, H.; Ruebsamen-Schaeff, H. Discovery, Chemistry, and Preclinical Development of Pritelivir, a Novel Treatment Option for Acyclovir-Resistant Herpes Simplex Virus Infections. J. Med. Chem, 2022, 65, 13614–13628. [CrossRef]

- Lv, W.; Zhou, L.; Wu, J.; Cheng, J.; Duan, Y.; Qian, W. Anti-HSV-1 Agents: An Update. Front. Pharmacol, 2025, 15. [CrossRef]

- Frejborg, F.; Kalke, K.; Hukkanen, V. Current Landscape in Antiviral Drug Development against Herpes Simplex Virus Infections. Smart Med, 2022, 1, e20220004. [CrossRef]

- Kuo, J.-Y.; Yeh, C.-S.; Wang, S.-M.; Chen, S.-H.; Wang, J.-R.; Chen, T.-Y.; Tsai, H.-P. Acyclovir-Resistant HSV-1 Isolates among Immunocompromised Patients in Southern Taiwan: Low Prevalence and Novel Mutations. J. Med. Virol, 2023, 95, e28985. [CrossRef]

- Zhong, G.; Chang, X.; Xie, W.; Zhou, X. Targeted Protein Degradation: Advances in Drug Discovery and Clinical Practice. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther, 2024, 9, 308. [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Liu, F.; Pal, S.; Hu, Q. Proteolysis-Targeting Drug Delivery System (ProDDS): Integrating Targeted Protein Degradation Concepts into Formulation Design. Chem. Soc. Rev, 2024, 53, 9582–9608. [CrossRef]

- Xue, Y.; Bolinger, Andrew A.; and Zhou, J. Novel Approaches to Targeted Protein Degradation Technologies in Drug Discovery. Expert Opin. Drug Discov, 2023, 18, 467–483. [CrossRef]

- Ambrozkiewicz, M.C.; Cuthill, K.J.; Harnett, D.; Kawabe, H.; Tarabykin, V. Molecular Evolution, Neurodevelopmental Roles and Clinical Significance of HECT-Type UBE3 E3 Ubiquitin Ligases. Cells, 2020, 9, 2455. [CrossRef]

- Pan, B.; Mountford, S.J.; Kiso, M.; Anderson, D.E.; Papadakis, G.; Jarman, K.E.; Tilmanis, D.R.; Maher, B.; Tran, T.; Shortt, J.; et al. Targeted Protein Degraders of SARS-CoV-2 Mpro Are More Active than Enzymatic Inhibition Alone with Activity against Nirmatrelvir Resistant Virus. Commun. Med, 2025, 5, 140. [CrossRef]

- Borges, P.H.O.; Ferreira, S.B.; Silva, F.P. Recent Advances on Targeting Proteases for Antiviral Development. Viruses, 2024, 16, 366. [CrossRef]

- McCloskey, E.; Kashipathy, M.; Cooper, A.; Gao, P.; Johnson, D.K.; Battaile, K.P.; Lovell, S.; Davido, D.J. HSV-1 ICP0 Dimer Domain Adopts a Novel β-Barrel Fold. Proteins, 2024, 92, 830–841. [CrossRef]

- Perusina Lanfranca, M.; van Loben Sels, J.M.; Ly, C.Y.; Grams, T.R.; Dhummakupt, A.; Bloom, D.C.; Davido, D.J. A 77 Amino Acid Region in the N-Terminal Half of the HSV-1 E3 Ubiquitin Ligase ICP0 Contributes to Counteracting an Established Type 1 Interferon Response. Microbiol. Spectr, 2022, 10, e00593-22. [CrossRef]

- Harrell, T.L.; Davido, D.J.; Bertke, A.S. Herpes Simplex Virus 1 (HSV-1) Infected Cell Protein 0 (ICP0) Targets of Ubiquitination during Productive Infection of Primary Adult Sensory Neurons. Int. J. Mol. Sci, 2023, 24, 2931. [CrossRef]

- Jan Fada, B.; Guha, U.; Zheng, Y.; Reward, E.; Kaadi, E.; Dourra, A.; Gu, H. A Novel Recognition by the E3 Ubiquitin Ligase of HSV-1 ICP0 Enhances the Degradation of PML Isoform I to Prevent ND10 Reformation in Late Infection. Viruses, 2023, 15, 1070. [CrossRef]

- Hou, F.; Sun, Z.; Deng, Y.; Chen, S.; Yang, X.; Ji, F.; Zhou, M.; Ren, K.; Pan, D. Interactome and Ubiquitinome Analyses Identify Functional Targets of Herpes Simplex Virus 1 Infected Cell Protein 0. Front. Microbiol, 2022, 13. [CrossRef]

- Das, R.; Hembram, D. The Viral SUMO-Targeted Ubiquitin Ligase ICP0 Is Phosphorylated and Activated by Host Kinase Chk2. FASEB J, 2021, 35. [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez, M.C.; Dybas, J.M.; Hughes, J.; Weitzman, M.D.; Boutell, C. The HSV-1 Ubiquitin Ligase ICP0: Modifying the Cellular Proteome to Promote Infection. Virus Res, 2020, 285, 198015. [CrossRef]

- Maillet, S.; Naas, T.; Crepin, S.; Roque-Afonso, A.-M.; Lafay, F.; Efstathiou, S.; Labetoulle, M. Herpes Simplex Virus Type 1 Latently Infected Neurons Differentially Express Latency-Associated and ICP0 Transcripts. J. Virol 2006, 80, 9310–9321. [CrossRef]

- The UniProt Consortium UniProt: The Universal Protein Knowledgebase in 2025. Nucleic Acids Res, 2025, 53, D609–D617. [CrossRef]

- Abramson, J.; Adler, J.; Dunger, J.; Evans, R.; Green, T.; Pritzel, A.; Ronneberger, O.; Willmore, L.; Ballard, A.J.; Bambrick, J.; et al. Accurate Structure Prediction of Biomolecular Interactions with AlphaFold 3. Nature, 2024, 630, 493–500. [CrossRef]

- Passaro, S.; Corso, G.; Wohlwend, J.; Reveiz, M.; Thaler, S.; Somnath, V.R.; Getz, N.; Portnoi, T.; Roy, J.; Stark, H.; et al. Boltz-2: Towards Accurate and Efficient Binding Affinity Prediction. BioRxiv, 2025, doi:2025.06.14.659707.

- Discovery, C.; Boitreaud, J.; Dent, J.; McPartlon, M.; Meier, J.; Reis, V.; Rogozhnikov, A.; Wu, K. Chai-1: Decoding the Molecular Interactions of Life. BioRxiv, 2024, doi:2024.10.10.615955.

- Team, B.A.A.; Chen, X.; Zhang, Y.; Lu, C.; Ma, W.; Guan, J.; Gong, C.; Yang, J.; Zhang, H.; Zhang, K.; et al. Protenix - Advancing Structure Prediction Through a Comprehensive AlphaFold3 Reproduction. BioRxiv, 2025, doi:2025.01.08.631967.

- Baek, M.; Anishchenko, I.; Humphreys, I.R.; Cong, Q.; Baker, D.; DiMaio, F. Efficient and Accurate Prediction of Protein Structure Using RoseTTAFold2. BioRxiv, 2023, doi:2023.05.24.542179.

- Pettersen, E.F.; Goddard, T.D.; Huang, C.C.; Couch, G.S.; Greenblatt, D.M.; Meng, E.C.; Ferrin, T.E. UCSF Chimera—A Visualization System for Exploratory Research and Analysis. J. Comput. Chem, 2004, 25, 1605–1612. [CrossRef]

- Sehnal, D.; Bittrich, S.; Deshpande, M.; Svobodová, R.; Berka, K.; Bazgier, V.; Velankar, S.; Burley, S.K.; Koča, J.; Rose, A.S. Mol* Viewer: Modern Web App for 3D Visualization and Analysis of Large Biomolecular Structures. Nucleic Acids Res, 2021, 49, W431–W437. [CrossRef]

- Laskowski, R.A.; Swindells, M.B. LigPlot+: Multiple Ligand–Protein Interaction Diagrams for Drug Discovery. J. Chem. Inf. Model, 2011, 51, 2778–2786. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).