Submitted:

08 July 2025

Posted:

09 July 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

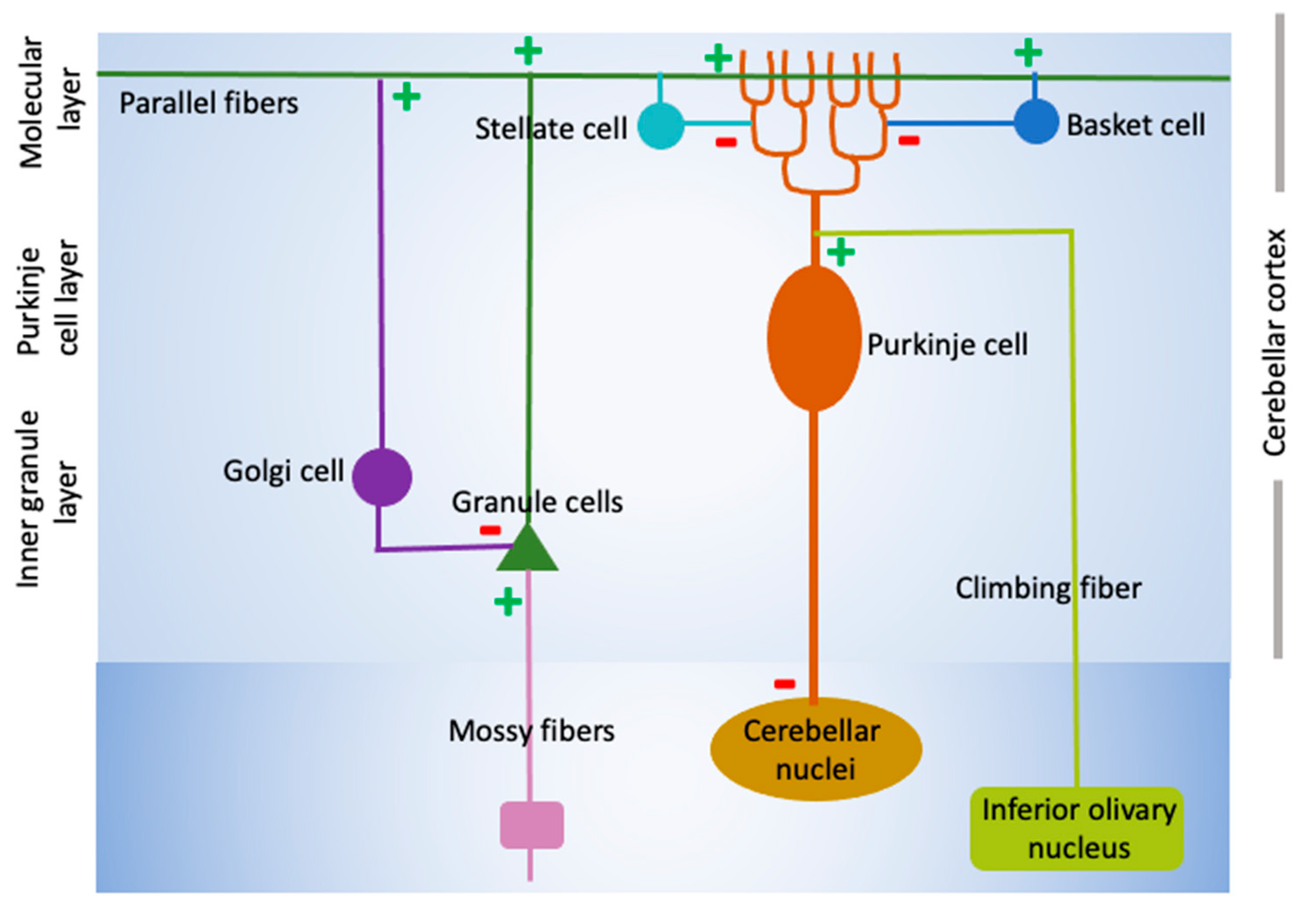

Cerebellar Structure and Function

Cerebellum in Human Studies of Autism

Cerebellar Development in ASD

The Genetic Basis of ASD

- I.

- Candidate Gene Approach

- Protein Regulating Synaptic Function and Neurotransmission

- B.

- Proteins Involved in Cerebellar Development and Other Cellular Functions:

- C.

- Whole Genome Analyses

Conclusion

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Abbasy, S.; Shahraki, F.; Haghighatfard, A.; Qazvini, M.G.; Rafiei, S.T.; Noshadirad, E.; et al. Neuregulin1 types mRNA level changes in autism spectrum disorder, and is associated with deficit in executive functions. EBioMedicine 2018, 37, 483–488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abdul, F.; Sreenivas, N.; Kommu, J.V.S.; Banerjee, M.; Berk, M.; Maes, M.; et al. Disruption of circadian rhythm and risk of autism spectrum disorder: role of immune-inflammatory, oxidative stress, metabolic and neurotransmitter pathways. Rev Neurosci 2022, 33, 93–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abreu, N.J.; Siemon, A.E.; Baylis, A.L.; Kirschner, R.E.; Pfau, R.B.; Ho, M.-L.; et al. Novel truncating variant in KMT2E associated with cerebellar hypoplasia and velopharyngeal dysfunction. Clin Case Rep 2022, 10, e05277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agarwal, M.; Johnston, M.V.; Stafstrom, C.E. SYNGAP1 mutations: Clinical, genetic, and pathophysiological features. Int J Dev Neurosci 2019, 78, 65–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Ali, Z.; Yasseen, A.A.; Al-Dujailli, A.; Al-Karaqully, A.J.; McAllister, K.A.; Jumaah, A.S. The oxytocin receptor gene polymorphism rs2268491 and serum oxytocin alterations are indicative of autism spectrum disorder: A case-control paediatric study in Iraq with personalized medicine implications. PLoS One 2022, 17, e0265217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albrecht, U.; Sutcliffe, J.S.; Cattanach, B.M.; Beechey, C.V.; Armstrong, D.; Eichele, G.; et al. Imprinted expression of the murine Angelman syndrome gene, Ube3a, in hippocampal and Purkinje neurons. Nat Genet 1997, 17, 75–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alho, J.; Samuelsson, J.G.; Khan, S.; Mamashli, F.; Bharadwaj, H.; Losh, A.; et al. Both stronger and weaker cerebro-cerebellar functional connectivity patterns during processing of spoken sentences in autism spectrum disorder. Hum Brain Mapp 2023, 44, 5810–5827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, H.; Marth, L.; Krueger-Burg, D. Neuroligin-2 as a central organizer of inhibitory synapses in health and disease. Sci Signal 2020, 13, eabd8379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alnak, A.; Kuşcu Özücer, İ.; Okay Çağlayan, A.; Coşkun, M. Peripheral Expression of MACROD2 Gene Is Reduced Among a Sample of Turkish Children with Autism Spectrum Disorder. Psychiatry Clin Psychopharmacol 2021, 31, 261–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alonso-Gonzalez, A.; Calaza, M.; Rodriguez-Fontenla, C.; Carracedo, A. Novel Gene-Based Analysis of ASD GWAS: Insight Into the Biological Role of Associated Genes. Front Genet 2019, 10, 733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alsaqati, M.; Heine, V.M.; Harwood, A.J. Pharmacological intervention to restore connectivity deficits of neuronal networks derived from ASD patient iPSC with a TSC2 mutation. Mol Autism 2020, 11, 80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anderson, G.R.; Galfin, T.; Xu, W.; Aoto, J.; Malenka, R.C.; Südhof, T.C. Candidate autism gene screen identifies critical role for cell-adhesion molecule CASPR2 in dendritic arborization and spine development. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2012, 109, 18120–18125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Andrade, C. Maternal Cannabis Use in Pregnancy and Autism Spectrum Disorder or Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder in Offspring. J Clin Psychiatry 2024, 86, 24f15717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andrade-Talavera, Y.; Pérez-Rodríguez, M.; Prius-Mengual, J.; Rodríguez-Moreno, A. Neuronal and astrocyte determinants of critical periods of plasticity. Trends Neurosci 2023, 46, 566–580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

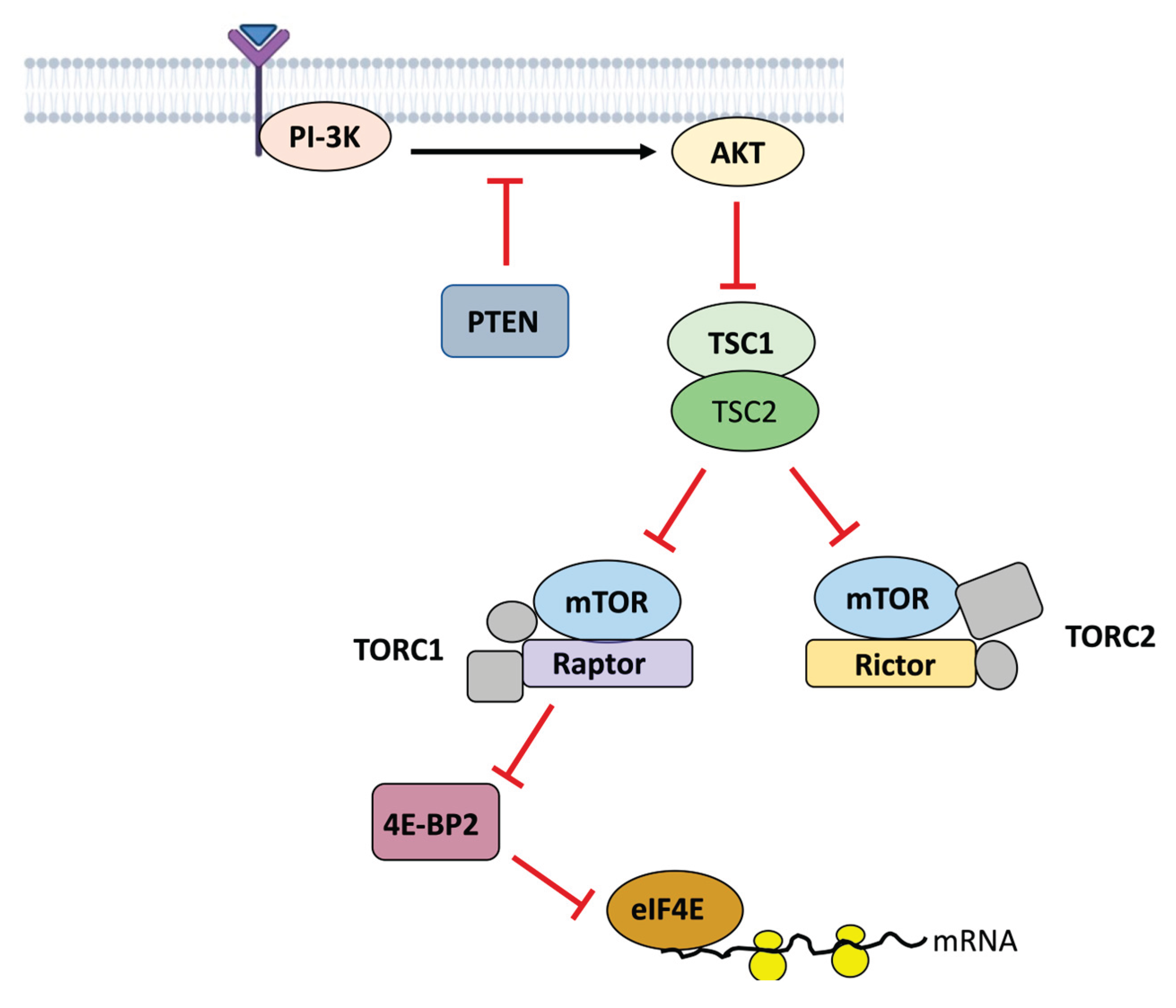

- Angliker, N.; Burri, M.; Zaichuk, M.; Fritschy, J.-M.; Rüegg, M.A. mTORC1 and mTORC2 have largely distinct functions in Purkinje cells. Eur J Neurosci 2015, 42, 2595–2612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Angrand, L.; Masson, J.-D.; Rubio-Casillas, A.; Nosten-Bertrand, M.; Crépeaux, G. Inflammation and Autophagy: A Convergent Point between Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD)-Related Genetic and Environmental Factors: Focus on Aluminum Adjuvants. Toxics 2022, 10, 518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aoto, J.; Földy, C.; Ilcus, S.M.C.; Tabuchi, K.; Südhof, T.C. Distinct circuit-dependent functions of presynaptic neurexin-3 at GABAergic and glutamatergic synapses. Nat Neurosci 2015, 18, 997–1007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Argent, L.; Winter, F.; Prickett, I.; Carrasquero-Ordaz, M.; Olsen, A.L.; Kramer, H.; et al. Caspr2 interacts with type 1 inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate receptor in the developing cerebellum and regulates Purkinje cell morphology. J Biol Chem 2020, 295, 12716–12726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aristidou, C.; Koufaris, C.; Theodosiou, A.; Bak, M.; Mehrjouy, M.M.; Behjati, F.; et al. Accurate Breakpoint Mapping in Apparently Balanced Translocation Families with Discordant Phenotypes Using Whole Genome Mate-Pair Sequencing. PLoS One 2017, 12, e0169935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arking, D.E.; Cutler, D.J.; Brune, C.W.; Teslovich, T.M.; West, K.; Ikeda, M.; et al. A common genetic variant in the neurexin superfamily member CNTNAP2 increases familial risk of autism. Am J Hum Genet 2008, 82, 160–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Armstrong, C.L.; Duffin, C.A.; McFarland, R.; Vogel, M.W. Mechanisms of compartmental purkinje cell death and survival in the lurcher mutant mouse. Cerebellum 2011, 10, 504–514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Armstrong, E.C.; Caruso, A.; Servadio, M.; Andreae, L.C.; Trezza, V.; Scattoni, M.L.; et al. Assessing the developmental trajectory of mouse models of neurodevelopmental disorders: Social and communication deficits in mice with Neurexin 1α deletion. Genes Brain Behav 2020, 19, e12630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arndt, K.; Nakagawa, S.; Takeichi, M.; Redies, C. Cadherin-Defined Segments and Parasagittal Cell Ribbons in the Developing Chicken Cerebellum. Mol Cell Neurosci 1998, 10, 211–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Autism Spectrum Disorders Working Group of The Psychiatric Genomics Consortium Meta-analysis of GWAS of over 16,000 individuals with autism spectrum disorder highlights a novel locus at 10q24.32 and a significant overlap with schizophrenia. Mol Autism 2017, 8, 21. [CrossRef]

- Bacchelli, E.; Cameli, C.; Viggiano, M.; Igliozzi, R.; Mancini, A.; Tancredi, R.; et al. An integrated analysis of rare CNV and exome variation in Autism Spectrum Disorder using the Infinium PsychArray. Sci Rep 2020, 10, 3198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bai, D.; Yip, B.H.K.; Windham, G.C.; Sourander, A.; Francis, R.; Yoffe, R.; et al. Association of Genetic and Environmental Factors With Autism in a 5-Country Cohort. JAMA Psychiatry 2019, 76, 1035–1043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bailey, A.; Luthert, P.; Dean, A.; Harding, B.; Janota, I.; Montgomery, M.; et al. A clinicopathological study of autism. Brain 1998, 121 Pt 5, 889–905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baio, J.; Wiggins, L.; Christensen, D.L.; Maenner, M.J.; Daniels, J.; Warren, Z.; et al. Prevalence of Autism Spectrum Disorder Among Children Aged 8 Years - Autism and Developmental Disabilities Monitoring Network, 11 Sites, United States, 2014. MMWR Surveill Summ 2018, 67, 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baizer, J.S. Neuroanatomy of autism: what is the role of the cerebellum? Cereb Cortex 2024, 34, 94–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakkaloglu, B.; O’Roak, B.J.; Louvi, A.; Gupta, A.R.; Abelson, J.F.; Morgan, T.M.; et al. Molecular cytogenetic analysis and resequencing of contactin associated protein-like 2 in autism spectrum disorders. Am J Hum Genet 2008, 82, 165–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banko, J.L.; Merhav, M.; Stern, E.; Sonenberg, N.; Rosenblum, K.; Klann, E. Behavioral alterations in mice lacking the translation repressor 4E-BP2. Neurobiol Learn Mem 2007, 87, 248–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banko, J.L.; Poulin, F.; Hou, L.; DeMaria, C.T.; Sonenberg, N.; Klann, E. The translation repressor 4E-BP2 is critical for eIF4F complex formation, synaptic plasticity, and memory in the hippocampus. J Neurosci 2005, 25, 9581–9590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Basu, R.; Taylor, M.R.; Williams, M.E. The classic cadherins in synaptic specificity. Cell Adh Migr 2015, 9, 193–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Battaglioni, S.; Benjamin, D.; Wälchli, M.; Maier, T.; Hall, M.N. mTOR substrate phosphorylation in growth control. Cell 2022, 185, 1814–1836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bauman, M.; Kemper, T.L. Histoanatomic observations of the brain in early infantile autism. Neurology 1985, 35, 866–874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Becker, E.B.E.; Stoodley, C.J. Autism spectrum disorder and the cerebellum. Int Rev Neurobiol 2013, 113, 1–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Behesti, H.; Fore, T.R.; Wu, P.; Horn, Z.; Leppert, M.; Hull, C.; et al. ASTN2 modulates synaptic strength by trafficking and degradation of surface proteins. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2018, 115, E9717–E9726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bellamy, T.C. Interactions between Purkinje neurones and Bergmann glia. Cerebellum 2006, 5, 116–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ben Haim, L.; Rowitch, D.H. Functional diversity of astrocytes in neural circuit regulation. Nat Rev Neurosci 2017, 18, 31–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benayed, R.; Choi, J.; Matteson, P.G.; Gharani, N.; Kamdar, S.; Brzustowicz, L.M.; et al. Autism-associated haplotype affects the regulation of the homeobox gene, ENGRAILED 2. Biol Psychiatry 2009, 66, 911–917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benayed, R.; Gharani, N.; Rossman, I.; Mancuso, V.; Lazar, G.; Kamdar, S.; et al. Support for the homeobox transcription factor gene ENGRAILED 2 as an autism spectrum disorder susceptibility locus. Am J Hum Genet 2005, 77, 851–868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bering, T.; Hertz, H.; Rath, M.F. The Circadian Oscillator of the Cerebellum: Triiodothyronine Regulates Clock Gene Expression in Granule Cells in vitro and in the Cerebellum of Neonatal Rats in vivo. Front. Physiol. 2021, 12, 706433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Betancur, C.; Sakurai, T.; Buxbaum, J.D. The emerging role of synaptic cell-adhesion pathways in the pathogenesis of autism spectrum disorders. Trends Neurosci 2009, 32, 402–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beversdorf, D.Q.; Stevens, H.E.; Jones, K.L. Prenatal Stress, Maternal Immune Dysregulation, and Their Association With Autism Spectrum Disorders. Curr Psychiatry Rep 2018, 20, 76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bi, W.; Yan, J.; Shi, X.; Yuva-Paylor, L.A.; Antalffy, B.A.; Goldman, A.; et al. Rai1 deficiency in mice causes learning impairment and motor dysfunction, whereas Rai1 heterozygous mice display minimal behavioral phenotypes. Hum Mol Genet 2007, 16, 1802–1813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bilinovich, S.M.; Lewis, K.; Grepo, N.; Campbell, D.B. The Long Noncoding RNA RPS10P2-AS1 Is Implicated in Autism Spectrum Disorder Risk and Modulates Gene Expression in Human Neuronal Progenitor Cells. Front. Genet. 2019, 10, 970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Birtele, M.; Del Dosso, A.; Xu, T.; Nguyen, T.; Wilkinson, B.; Hosseini, N.; et al. Non-synaptic function of the autism spectrum disorder-associated gene SYNGAP1 in cortical neurogenesis. Nat Neurosci 2023, 26, 2090–2103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blundell, J.; Blaiss, C.A.; Etherton, M.R.; Espinosa, F.; Tabuchi, K.; Walz, C.; et al. Neuroligin-1 deletion results in impaired spatial memory and increased repetitive behavior. J Neurosci 2010, 30, 2115–2129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Blundell, J.; Tabuchi, K.; Bolliger, M.F.; Blaiss, C.A.; Brose, N.; Liu, X.; et al. Increased anxiety-like behavior in mice lacking the inhibitory synapse cell adhesion molecule neuroligin 2. Genes Brain Behav 2009, 8, 114–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boccuto, L.; Lauri, M.; Sarasua, S.M.; Skinner, C.D.; Buccella, D.; Dwivedi, A.; et al. Prevalence of SHANK3 variants in patients with different subtypes of autism spectrum disorders. Eur J Hum Genet 2013, 21, 310–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Böckers, T.M.; Segger-Junius, M.; Iglauer, P.; Bockmann, J.; Gundelfinger, E.D.; Kreutz, M.R.; et al. Differential expression and dendritic transcript localization of Shank family members: identification of a dendritic targeting element in the 3’ untranslated region of Shank1 mRNA. Mol Cell Neurosci 2004, 26, 182–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boer, K.; Troost, D.; Jansen, F.; Nellist, M.; van den Ouweland, A.M.W.; Geurts, J.J.G.; et al. Clinicopathological and immunohistochemical findings in an autopsy case of tuberous sclerosis complex. Neuropathology 2008, 28, 577–590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bolliger, M.F.; Pei, J.; Maxeiner, S.; Boucard, A.A.; Grishin, N.V.; Südhof, T.C. Unusually rapid evolution of Neuroligin-4 in mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2008, 105, 6421–6426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bonora, E.; Graziano, C.; Minopoli, F.; Bacchelli, E.; Magini, P.; Diquigiovanni, C.; et al. Maternally inherited genetic variants of CADPS2 are present in autism spectrum disorders and intellectual disability patients. EMBO Mol Med 2014, 6, 795–809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Born, G.; Grayton, H.M.; Langhorst, H.; Dudanova, I.; Rohlmann, A.; Woodward, B.W.; et al. Genetic targeting of NRXN2 in mice unveils role in excitatory cortical synapse function and social behaviors. Front Synaptic Neurosci 2015, 7, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boucherie, C.; Boutin, C.; Jossin, Y.; Schakman, O.; Goffinet, A.M.; Ris, L.; et al. Neural progenitor fate decision defects, cortical hypoplasia and behavioral impairment in Celsr1-deficient mice. Mol Psychiatry 2018, 23, 723–734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boukhtouche, F.; Doulazmi, M.; Frederic, F.; Dusart, I.; Brugg, B.; Mariani, J. RORalpha, a pivotal nuclear receptor for Purkinje neuron survival and differentiation: from development to ageing. Cerebellum 2006, 5, 97–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boukhtouche, F.; Janmaat, S.; Vodjdani, G.; Gautheron, V.; Mallet, J.; Dusart, I.; et al. Retinoid-related orphan receptor alpha controls the early steps of Purkinje cell dendritic differentiation. J Neurosci 2006, 26, 1531–1538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bourgeron, T. From the genetic architecture to synaptic plasticity in autism spectrum disorder. Nat Rev Neurosci 2015, 16, 551–563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bowling, H.; Klann, E. Shaping dendritic spines in autism spectrum disorder: mTORC1-dependent macroautophagy. Neuron 2014, 83, 994–996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brandenburg, C.; Griswold, A.J.; Van Booven, D.J.; Kilander, M.B.C.; Frei, J.A.; Nestor, M.W.; et al. Transcriptomic analysis of isolated and pooled human postmortem cerebellar Purkinje cells in autism spectrum disorders. Front Genet 2022, 13, 944837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brielmaier, J.; Matteson, P.G.; Silverman, J.L.; Senerth, J.M.; Kelly, S.; Genestine, M.; et al. Autism-relevant social abnormalities and cognitive deficits in engrailed-2 knockout mice. PLoS One 2012, 7, e40914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bromley, R.L.; Mawer, G.E.; Briggs, M.; Cheyne, C.; Clayton-Smith, J.; García-Fiñana, M.; et al. The prevalence of neurodevelopmental disorders in children prenatally exposed to antiepileptic drugs. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 2013, 84, 637–643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brown, D.J.; Lin, B.; Holguin, B. Expression of neuregulin 1, a member of the epidermal growth factor family, is expressed as multiple splice variants in the adult human cornea. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 2004, 45, 3021–3029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bruinsma, C.F.; Schonewille, M.; Gao, Z.; Aronica, E.M.A.; Judson, M.C.; Philpot, B.D.; et al. Dissociation of locomotor and cerebellar deficits in a murine Angelman syndrome model. J Clin Invest 2015, 125, 4305–4315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bruno, L.P.; Doddato, G.; Valentino, F.; Baldassarri, M.; Tita, R.; Fallerini, C.; et al. New Candidates for Autism/Intellectual Disability Identified by Whole-Exome Sequencing. Int J Mol Sci 2021, 22, 13439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Busfield, S.J.; Michnick, D.A.; Chickering, T.W.; Revett, T.L.; Ma, J.; Woolf, E.A.; et al. Characterization of a neuregulin-related gene, Don-1, that is highly expressed in restricted regions of the cerebellum and hippocampus. Mol Cell Biol 1997, 17, 4007–4014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Butler, M.G.; Dasouki, M.J.; Zhou, X.-P.; Talebizadeh, Z.; Brown, M.; Takahashi, T.N.; et al. Subset of individuals with autism spectrum disorders and extreme macrocephaly associated with germline PTEN tumour suppressor gene mutations. J Med Genet 2005, 42, 318–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buxbaum, J.D.; Cai, G.; Chaste, P.; Nygren, G.; Goldsmith, J.; Reichert, J.; et al. Mutation screening of the PTEN gene in patients with autism spectrum disorders and macrocephaly. Am J Med Genet B Neuropsychiatr Genet 2007, 144B, 484–491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- C, P.; Ad, K.; G, G.; Hk, T.; H, N.; K, H.; et al. Cerebellar plasticity and motor learning deficits in a copy-number variation mouse model of autism. Nature communications 2014, 5, 5586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caballero, M.; Satterstrom, F.K.; Buxbaum, J.D.; Mahjani, B. Identification of moderate effect size genes in autism spectrum disorder through a novel gene pairing approach. medRxiv 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, X.-Y.; Wang, X.-T.; Guo, J.-W.; Xu, F.-X.; Ma, K.-Y.; Wang, Z.-X.; et al. Aberrant outputs of cerebellar nuclei and targeted rescue of social deficits in an autism mouse model. Protein Cell 2024, 15, pwae040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cakar, M.E.; Okada, N.J.; Cummings, K.K.; Jung, J.; Bookheimer, S.Y.; Dapretto, M.; et al. Functional connectivity of the sensorimotor cerebellum in autism: associations with sensory over-responsivity. Front. Psychiatry 2024, 15, 1337921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cantando, I.; Centofanti, C.; D’Alessandro, G.; Limatola, C.; Bezzi, P. Metabolic dynamics in astrocytes and microglia during post-natal development and their implications for autism spectrum disorders. Front Cell Neurosci 2024, 18, 1354259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, L.; Molina, J.; Abad, C.; Carmona-Mora, P.; Cárdenas Oyarzo, A.; Young, J.I.; et al. Correct developmental expression level of Rai1 in forebrain neurons is required for control of body weight, activity levels and learning and memory. Hum Mol Genet 2014, 23, 1771–1782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Capal, J.K.; Jeste, S.S. Autism and Epilepsy. Pediatr Clin North Am 2024, 71, 241–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carrión-Castillo, A.; Boeckx, C. Insights into the genetic architecture of cerebellar lobules derived from the UK Biobank. Sci Rep 2024, 14, 9488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carta, I.; Chen, C.H.; Schott, A.L.; Dorizan, S.; Khodakhah, K. Cerebellar modulation of the reward circuitry and social behavior. Science 2019, 363, eaav0581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carter, C.S.; Kenkel, W.M.; MacLean, E.L.; Wilson, S.R.; Perkeybile, A.M.; Yee, J.R.; et al. Is Oxytocin “Nature’s Medicine”? Pharmacol Rev 2020, 72, 829–861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cast, T.P.; Boesch, D.J.; Smyth, K.; Shaw, A.E.; Ghebrial, M.; Chanda, S. An Autism-Associated Mutation Impairs Neuroligin-4 Glycosylation and Enhances Excitatory Synaptic Transmission in Human Neurons. J Neurosci 2021, 41, 392–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cendelin, J. From mice to men: lessons from mutant ataxic mice. Cerebellum Ataxias 2014, 1, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chabrol, F.P.; Blot, A.; Mrsic-Flogel, T.D. Cerebellar Contribution to Preparatory Activity in Motor Neocortex. Neuron 2019, 103, 506–519.e4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chahrour, M.; O’Roak, B.J.; Santini, E.; Samaco, R.C.; Kleiman, R.J.; Manzini, M.C. Current Perspectives in Autism Spectrum Disorder: From Genes to Therapy. J Neurosci 2016, 36, 11402–11410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chalkiadaki, K.; Statoulla, E.; Zafeiri, M.; Haji, N.; Lacaille, J.-C.; Powell, C.M.; et al. Reversal of memory and autism-related phenotypes in Tsc2+/- mice via inhibition of Nlgn1. Front Cell Dev Biol 2023, 11, 1205112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chambers, T.; Escott-Price, V.; Legge, S.; Baker, E.; Singh, K.D.; Walters, J.T.R.; et al. Genetic common variants associated with cerebellar volume and their overlap with mental disorders: a study on 33,265 individuals from the UK-Biobank. Mol Psychiatry 2022, 27, 2282–2290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chanda, S.; Aoto, J.; Lee, S.-J.; Wernig, M.; Südhof, T.C. Pathogenic mechanism of an autism-associated neuroligin mutation involves altered AMPA-receptor trafficking. Mol Psychiatry 2016, 21, 169–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, Y.-T.; Kowalczyk, M.; Fogerson, P.M.; Lee, Y.-J.; Haque, M.; Adams, E.L.; et al. Loss of Rai1 enhances hippocampal excitability and epileptogenesis in mouse models of Smith-Magenis syndrome. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2022, 119, e2210122119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chapman, N.H.; Estes, A.; Munson, J.; Bernier, R.; Webb, S.J.; Rothstein, J.H.; et al. Genome-scan for IQ discrepancy in autism: evidence for loci on chromosomes 10 and 16. Hum Genet 2011, 129, 59–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheh, M.A.; Millonig, J.H.; Roselli, L.M.; Ming, X.; Jacobsen, E.; Kamdar, S.; et al. En2 knockout mice display neurobehavioral and neurochemical alterations relevant to autism spectrum disorder. Brain Res 2006, 1116, 166–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.J.; Rojas-Soto, M.; Oguni, A.; Kennedy, M.B. A synaptic Ras-GTPase activating protein (p135 SynGAP) inhibited by CaM kinase II. Neuron 1998, 20, 895–904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Yu, S.; Fu, Y.; Li, X. Synaptic proteins and receptors defects in autism spectrum disorders. Front Cell Neurosci 2014, 8, 276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Chen, T.; Dong, C.; Chen, H.; Dong, X.; Yang, L.; et al. Deletion of CHD8 in cerebellar granule neuron progenitors leads to severe cerebellar hypoplasia, ataxia, and psychiatric behavior in mice. J Genet Genomics 2022, 49, 859–869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Du, Y.; Broussard, G.J.; Kislin, M.; Yuede, C.M.; Zhang, S.; et al. Transcriptomic mapping uncovers Purkinje neuron plasticity driving learning. Nature 2022, 605, 722–727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, X.R.; Heck, N.; Lohof, A.M.; Rochefort, C.; Morel, M.-P.; Wehrlé, R.; et al. Mature Purkinje cells require the retinoic acid-related orphan receptor-α (RORα) to maintain climbing fiber mono-innervation and other adult characteristics. J Neurosci 2013, 33, 9546–9562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, Y.; Sudarov, A.; Szulc, K.U.; Sgaier, S.K.; Stephen, D.; Turnbull, D.H.; et al. The Engrailed homeobox genes determine the different foliation patterns in the vermis and hemispheres of the mammalian cerebellum. Development 2010, 137, 519–529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chernikova, M.A.; Flores, G.D.; Kilroy, E.; Labus, J.S.; Mayer, E.A.; Aziz-Zadeh, L. The Brain-Gut-Microbiome System: Pathways and Implications for Autism Spectrum Disorder. Nutrients 2021, 13, 4497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cheron, G.; Márquez-Ruiz, J.; Kishino, T.; Dan, B. Disruption of the LTD dialogue between the cerebellum and the cortex in Angelman syndrome model: a timing hypothesis. Front Syst Neurosci 2014, 8, 221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheroni, C.; Caporale, N.; Testa, G. Autism spectrum disorder at the crossroad between genes and environment: contributions, convergences, and interactions in ASD developmental pathophysiology. Mol Autism 2020, 11, 69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheung, C.; Chua, S.E.; Cheung, V.; Khong, P.L.; Tai, K.S.; Wong, T.K.W.; et al. White matter fractional anisotrophy differences and correlates of diagnostic symptoms in autism. J Child Psychol Psychiatry 2009, 50, 1102–1112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chien, W.-H.; Chen, C.-H.; Cheng, M.-C.; Wu, Y.-Y.; Gau, S.S.-F. Neuregulin 2 Is a Candidate Gene for Autism Spectrum Disorder. International Journal of Molecular Sciences 2024, 25, 5547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chih, B.; Engelman, H.; Scheiffele, P. Control of excitatory and inhibitory synapse formation by neuroligins. Science 2005, 307, 1324–1328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chih, B.; Engelman, H.; Scheiffele, P. Control of excitatory and inhibitory synapse formation by neuroligins. Science 2005, 307, 1324–1328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiocchetti, A.G.; Kopp, M.; Waltes, R.; Haslinger, D.; Duketis, E.; Jarczok, T.A.; et al. Variants of the CNTNAP2 5’ promoter as risk factors for autism spectrum disorders: a genetic and functional approach. Mol Psychiatry 2015, 20, 839–849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choe, K.Y.; Bethlehem, R.A.I.; Safrin, M.; Dong, H.; Salman, E.; Li, Y.; et al. Oxytocin normalizes altered circuit connectivity for social rescue of the Cntnap2 knockout mouse. Neuron 2022, 110, 795–808.e6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, J.; Ababon, M.R.; Soliman, M.; Lin, Y.; Brzustowicz, L.M.; Matteson, P.G.; et al. Autism associated gene, engrailed2, and flanking gene levels are altered in post-mortem cerebellum. PLoS One 2014, 9, e87208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christensen, Z.P.; Freedman, E.G.; Foxe, J.J. Autism is associated with in vivo changes in gray matter neurite architecture. Autism Res 2024, 17, 2261–2277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chrobak, A.A.; Soltys, Z. Bergmann Glia, Long-Term Depression, and Autism Spectrum Disorder. Mol Neurobiol 2017, 54, 1156–1166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ciricugno, A.; Ferrari, C.; Battelli, L.; Cattaneo, Z. A chronometric study of the posterior cerebellum’s function in emotional processing. Curr Biol 2024, 34, 1844–1852.e3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Clayton-Smith, J.; Donnai, D. Fetal valproate syndrome. J Med Genet 1995, 32, 724–727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cooper, J.N.; Mittal, J.; Sangadi, A.; Klassen, D.L.; King, A.M.; Zalta, M.; et al. Landscape of NRXN1 Gene Variants in Phenotypic Manifestations of Autism Spectrum Disorder: A Systematic Review. J Clin Med 2024, 13, 2067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costa, C.I.S.; da Silva Montenegro, E.M.; Zarrei, M.; de Sá Moreira, E.; Silva, I.M.W.; de Oliveira Scliar, M.; et al. Copy number variations in a Brazilian cohort with autism spectrum disorders highlight the contribution of cell adhesion genes. Clin Genet 2022, 101, 134–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Courchesne, E. Neuroanatomic imaging in autism. Pediatrics 1991, 87, 781–790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Courchesne, E.; Mouton, P.R.; Calhoun, M.E.; Semendeferi, K.; Ahrens-Barbeau, C.; Hallet, M.J.; et al. Neuron number and size in prefrontal cortex of children with autism. JAMA 2011, 306, 2001–2010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Courchesne, E.; Pramparo, T.; Gazestani, V.H.; Lombardo, M.V.; Pierce, K.; Lewis, N.E. The ASD Living Biology: from cell proliferation to clinical phenotype. Mol Psychiatry 2019, 24, 88–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Craig, A.M.; Kang, Y. Neurexin-neuroligin signaling in synapse development. Curr Opin Neurobiol 2007m 17, 43–52. [CrossRef]

- Crawley, J.N. Mouse behavioral assays relevant to the symptoms of autism. Brain Pathol 2007, 17, 448–459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crepel, A.; De Wolf, V.; Brison, N.; Ceulemans, B.; Walleghem, D.; Peuteman, G.; et al. Association of CDH11 with non-syndromic ASD. Am J Med Genet B Neuropsychiatr Genet 2014, 165B, 391–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cukier, H.N.; Dueker, N.D.; Slifer, S.H.; Lee, J.M.; Whitehead, P.L.; Lalanne, E.; et al. Exome sequencing of extended families with autism reveals genes shared across neurodevelopmental and neuropsychiatric disorders. Mol Autism 2014, 5, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cupolillo, D.; Hoxha, E.; Faralli, A.; De Luca, A.; Rossi, F.; Tempia, F.; et al. Autistic-Like Traits and Cerebellar Dysfunction in Purkinje Cell PTEN Knock-Out Mice. Neuropsychopharmacology 2016, 41, 1457–1466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cusmano, D.M.; Mong, J.A. In utero exposure to valproic acid changes sleep in juvenile rats: a model for sleep disturbances in autism. Sleep 2014, 37, 1489–1499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dahlhaus, R.; El-Husseini, A. Altered neuroligin expression is involved in social deficits in a mouse model of the fragile X syndrome. Behav Brain Res 2010, 208, 96–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Angelo, E. Physiology of the cerebellum. Handb Clin Neurol 2018, 154, 85–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Daskalakis, Z.J.; Christensen, B.K.; Fitzgerald, P.B.; Fountain, S.I.; Chen, R. Reduced cerebellar inhibition in schizophrenia: a preliminary study. Am J Psychiatry 2005, 162, 1203–1205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de Agustín-Durán, D.; Mateos-White, I.; Fabra-Beser, J.; Gil-Sanz, C. Stick around: Cell-Cell Adhesion Molecules during Neocortical Development. Cells 2021, 10, 118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Rubeis, S.; He, X.; Goldberg, A.P.; Poultney, C.S.; Samocha, K.; Cicek, A.E.; et al. Synaptic, transcriptional and chromatin genes disrupted in autism. Nature 2014, 515, 209–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Deciphering Developmental Disorders Study Prevalence and architecture of de novo mutations in developmental disorders. Nature 2017, 542, 433–438. [CrossRef]

- Deng, Y.; Ma, L.; Du, Z.; Ma, H.; Xia, Y.; Ping, L.; et al. The Notch1/Hes1 pathway regulates Neuregulin 1/ErbB4 and participates in microglial activation in rats with VPA-induced autism. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry 2024, 131, 110947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deverett, B.; Kislin, M.; Tank, D.W.; Wang, S.S.-H. Cerebellar disruption impairs working memory during evidence accumulation. Nat Commun 2019, 10, 3128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeWitt, J.J.; Grepo, N.; Wilkinson, B.; Evgrafov, O.V.; Knowles, J.A.; Campbell, D.B. Impact of the Autism-Associated Long Noncoding RNA MSNP1AS on Neuronal Architecture and Gene Expression in Human Neural Progenitor Cells. Genes (Basel) 2016, 7, 76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeWitt, J.J.; Hecht, P.M.; Grepo, N.; Wilkinson, B.; Evgrafov, O.V.; Morris, K.V.; et al. Transcriptional Gene Silencing of the Autism-Associated Long Noncoding RNA MSNP1AS in Human Neural Progenitor Cells. Dev Neurosci 2016, 38, 375–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dibner, C.; Schibler, U.; Albrecht, U. The mammalian circadian timing system: organization and coordination of central and peripheral clocks. Annu Rev Physiol 2010, 72, 517–549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dickinson, A.; Varcin, K.J.; Sahin, M.; Nelson, C.A.; Jeste, S.S. Early patterns of functional brain development associated with autism spectrum disorder in tuberous sclerosis complex. Autism Res 2019, 12, 1758–1773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dickson, P.E.; Cairns, J.; Goldowitz, D.; Mittleman, G. Cerebellar contribution to higher and lower order rule learning and cognitive flexibility in mice. Neuroscience 2017, 345, 99–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- DiLiberti, J.H.; Farndon, P.A.; Dennis, N.R.; Curry, C.J. The fetal valproate syndrome. Am J Med Genet 1984, 19, 473–481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Incal, C.; Van Dijck, A.; Ibrahim, J.; De Man, K.; Bastini, L.; Konings, A.; et al. ADNP dysregulates methylation and mitochondrial gene expression in the cerebellum of a Helsmoortel-Van der Aa syndrome autopsy case. Acta Neuropathol Commun 2024, 12, 62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dindot, S.V.; Antalffy, B.A.; Bhattacharjee, M.B.; Beaudet, A.L. The Angelman syndrome ubiquitin ligase localizes to the synapse and nucleus, and maternal deficiency results in abnormal dendritic spine morphology. Hum Mol Genet 2008, 17, 111–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, C.-Y.; Ding, Y.-T.; Ji, H.; Wang, Y.-Y.; Zhang, X.; Yin, D.-M. Genetic labeling reveals spatial and cellular expression pattern of neuregulin 1 in mouse brain. Cell Biosci 2023, 13, 79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Mello, A.M.; Moore, D.M.; Crocetti, D.; Mostofsky, S.H.; Stoodley, C.J. Cerebellar gray matter differentiates children with early language delay in autism. Autism Res 2016, 9, 1191–1204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Mello, A.M.; Stoodley, C.J. Cerebro-cerebellar circuits in autism spectrum disorder. Front Neurosci 2015, 9, 408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Mello, A.M.; Stoodley, C.J. Cerebro-cerebellar circuits in autism spectrum disorder. Front Neurosci 2015, 9, 408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- d’Oleire Uquillas, F.; Sefik, E.; Li, B.; Trotter, M.A.; Steele, K.A.; Seidlitz, J.; et al. Multimodal evidence for cerebellar influence on cortical development in autism: structural growth amidst functional disruption. Mol Psychiatry 2025, 30, 1558–1572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dong, D.; Zielke, H.R.; Yeh, D.; Yang, P. Cellular stress and apoptosis contribute to the pathogenesis of autism spectrum disorder. Autism Res 2018, 11, 1076–1090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doulazmi, M.; Frédéric, F.; Capone, F.; Becker-André, M.; Delhaye-Bouchaud, N.; Mariani, J. A comparative study of Purkinje cells in two RORalpha gene mutant mice: staggerer and RORalpha(-/-). Brain Res Dev Brain Res 2001, 127, 165–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Durand, C.M.; Betancur, C.; Boeckers, T.M.; Bockmann, J.; Chaste, P.; Fauchereau, F.; et al. Mutations in the gene encoding the synaptic scaffolding protein SHANK3 are associated with autism spectrum disorders. Nat Genet 2007, 39, 25–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Durand, C.M.; Perroy, J.; Loll, F.; Perrais, D.; Fagni, L.; Bourgeron, T.; et al. SHANK3 mutations identified in autism lead to modification of dendritic spine morphology via an actin-dependent mechanism. Mol Psychiatry 2012, 17, 71–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dusart, I.; Guenet, J.L.; Sotelo, C. Purkinje cell death: differences between developmental cell death and neurodegenerative death in mutant mice. Cerebellum 2006, 5, 163–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edmonson, C.; Ziats, M.N.; Rennert, O.M. Altered glial marker expression in autistic post-mortem prefrontal cortex and cerebellum. Mol Autism 2014, 5, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Kordi, A.; Winkler, D.; Hammerschmidt, K.; Kästner, A.; Krueger, D.; Ronnenberg, A.; et al. Development of an autism severity score for mice using Nlgn4 null mutants as a construct-valid model of heritable monogenic autism. Behav Brain Res 2013, 251, 41–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ellegood, J.; Crawley, J.N. Behavioral and Neuroanatomical Phenotypes in Mouse Models of Autism. Neurotherapeutics 2015, 12, 521–533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ellegood, J.; Lerch, J.P.; Henkelman, R.M. Brain abnormalities in a Neuroligin3 R451C knockin mouse model associated with autism. Autism Res 2011, 4, 368–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esnafoglu, E. Levels of peripheral Neuregulin 1 are increased in non-medicated autism spectrum disorder patients. J Clin Neurosci 2018, 57, 43–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esper, R.M.; Pankonin, M.S.; Loeb, J.A. Neuregulins: versatile growth and differentiation factors in nervous system development and human disease. Brain Res Rev 2006, 51, 161–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Etherton, M.; Földy, C.; Sharma, M.; Tabuchi, K.; Liu, X.; Shamloo, M.; et al. Autism-linked neuroligin-3 R451C mutation differentially alters hippocampal and cortical synaptic function. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2011, 108, 13764–13769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Etherton, M.R.; Blaiss, C.A.; Powell, C.M.; Südhof, T.C. Mouse neurexin-1alpha deletion causes correlated electrophysiological and behavioral changes consistent with cognitive impairments. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2009, 106, 17998–18003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, P.; Lev-Lehman, E.; Tsai, T.F.; Matsuura, T.; Benton, C.S.; Sutcliffe, J.S.; et al. The spectrum of mutations in UBE3A causing Angelman syndrome. Hum Mol Genet 1999, 8, 129–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farhy-Tselnicker, I.; Allen, N.J. Astrocytes, neurons, synapses: a tripartite view on cortical circuit development. Neural Dev 2018, 13, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Farini, D.; Cesari, E.; Weatheritt, R.J.; La Sala, G.; Naro, C.; Pagliarini, V.; et al. A Dynamic Splicing Program Ensures Proper Synaptic Connections in the Developing Cerebellum. Cell Rep 2020, 31, 107703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farini, D.; Marazziti, D.; Geloso, M.C.; Sette, C. Transcriptome programs involved in the development and structure of the cerebellum. Cell Mol Life Sci 2021, 78, 6431–6451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fatemi, S.H.; Aldinger, K.A.; Ashwood, P.; Bauman, M.L.; Blaha, C.D.; Blatt, G.J.; et al. Consensus paper: pathological role of the cerebellum in autism. Cerebellum 2012, 11, 777–807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fatemi, S.H.; Halt, A.R.; Realmuto, G.; Earle, J.; Kist, D.A.; Thuras, P.; et al. Purkinje cell size is reduced in cerebellum of patients with autism. Cell Mol Neurobiol 2002, 22, 171–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fatemi, S.H.; Halt, A.R.; Stary, J.M.; Kanodia, R.; Schulz, S.C.; Realmuto, G.R. Glutamic acid decarboxylase 65 and 67 kDa proteins are reduced in autistic parietal and cerebellar cortices. Biol Psychiatry 2002, 52, 805–810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fattorusso, A.; Di Genova, L.; Dell’Isola, G.B.; Mencaroni, E.; Esposito, S. Autism Spectrum Disorders and the Gut Microbiota. Nutrients 2019, 11, 521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ferguson, J.N.; Young, L.J.; Hearn, E.F.; Matzuk, M.M.; Insel, T.R.; Winslow, J.T. Social amnesia in mice lacking the oxytocin gene. Nat Genet 2000, 25, 284–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fernández, M.; Sánchez-León, C.A.; Llorente, J.; Sierra-Arregui, T.; Knafo, S.; Márquez-Ruiz, J.; et al. Altered Cerebellar Response to Somatosensory Stimuli in the Cntnap2 Mouse Model of Autism. eNeuro 2021, 8, ENEURO. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fernández Santoro, E.M.; Karim, A.; Warnaar, P.; De Zeeuw, C.I.; Badura, A.; Negrello, M. Purkinje cell models: past, present and future. Front Comput Neurosci 2024, 18, 1426653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ferraro, S.; de Zavalia, N.; Belforte, N.; Amir, S. In utero Exposure to Valproic-Acid Alters Circadian Organisation and Clock-Gene Expression: Implications for Autism Spectrum Disorders. Front Behav Neurosci 2021, 15, 711549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Floris, C.; Rassu, S.; Boccone, L.; Gasperini, D.; Cao, A.; Crisponi, L. Two patients with balanced translocations and autistic disorder: CSMD3 as a candidate gene for autism found in their common 8q23 breakpoint area. Eur J Hum Genet 2008, 16, 696–704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fragoso, Y.D.; Stoney, P.N.; Shearer, K.D.; Sementilli, A.; Nanescu, S.E.; Sementilli, P.; et al. Expression in the human brain of retinoic acid induced 1, a protein associated with neurobehavioural disorders. Brain Struct Funct 2015, 220, 1195–1203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frazier, T.W.; Embacher, R.; Tilot, A.K.; Koenig, K.; Mester, J.; Eng, C. Molecular and phenotypic abnormalities in individuals with germline heterozygous PTEN mutations and autism. Mol Psychiatry 2015, 20, 1132–1138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frei, J.A.; Brandenburg, C.; Nestor, J.E.; Hodzic, D.M.; Plachez, C.; McNeill, H.; et al. Postnatal expression profiles of atypical cadherin FAT1 suggest its role in autism. Biol Open 2021, 10, bio056457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frei, J.A.; Niescier, R.F.; Bridi, M.S.; Durens, M.; Nestor, J.E.; Kilander, M.B.C.; et al. Regulation of Neural Circuit Development by Cadherin-11 Provides Implications for Autism. eNeuro 2021, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Froemke, R.C.; Young, L.J. Oxytocin, Neural Plasticity, and Social Behavior. Annu Rev Neurosci 2021, 44, 359–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Frosch, I.R.; Mittal, V.A.; D’Mello, A.M. Cerebellar Contributions to Social Cognition in ASD: A Predictive Processing Framework. Front Integr Neurosci 2022, 16, 810425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, J.M.; Satterstrom, F.K.; Peng, M.; Brand, H.; Collins, R.L.; Dong, S.; et al. Rare coding variation provides insight into the genetic architecture and phenotypic context of autism. Nat Genet 2022, 54, 1320–1331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fujima, S.; Yamaga, R.; Minami, H.; Mizuno, S.; Shinoda, Y.; Sadakata, T.; et al. CAPS2 Deficiency Impairs the Release of the Social Peptide Oxytocin, as Well as Oxytocin-Associated Social Behavior. J Neurosci 2021, 41, 4524–4535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gambini, D.; Ferrero, S.; Bulfamante, G.; Pisani, L.; Corbo, M.; Kuhn, E. Cerebellar phenotypes in germline PTEN mutation carriers. Neuropathol Appl Neurobiol 2024, 50, e12970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, R.; Penzes, P. Common mechanisms of excitatory and inhibitory imbalance in schizophrenia and autism spectrum disorders. Curr Mol Med 2015, 15, 146–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garber, K. Neuroscience. Autism’s cause may reside in abnormalities at the synapse. Science 2007, 317, 190–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gardner, Z.; Holbrook, O.; Tian, Y.; Odamah, K.; Man, H.-Y. The role of glia in the dysregulation of neuronal spinogenesis in Ube3a-dependent ASD. Exp Neurol 2024, 376, 114756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaubitz, C.; Prouteau, M.; Kusmider, B.; Loewith, R. TORC2 Structure and Function. Trends Biochem Sci 2016, 41, 532–545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gauthier, J.; Siddiqui, T.J.; Huashan, P.; Yokomaku, D.; Hamdan, F.F.; Champagne, N.; et al. Truncating mutations in NRXN2 and NRXN1 in autism spectrum disorders and schizophrenia. Hum Genet 2011, 130, 563–573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Genovese, A.; Butler, M.G. The Autism Spectrum: Behavioral, Psychiatric and Genetic Associations. Genes (Basel) 2023, 14, 677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Geoffray, M.-M.; Nicolas, A.; Speranza, M.; Georgieff, N. Are circadian rhythms new pathways to understand Autism Spectrum Disorder? J Physiol Paris 2016, 110, 434–438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gerhant, A.; Olajossy, M.; Olajossy-Hilkesberger, L. [Neuroanatomical, genetic and neurochemical aspects of infantile autism]. Psychiatr Pol 2013, 47, 1101–1111. [Google Scholar]

- Gerik-Celebi, H.B.; Bolat, H.; Unsel-Bolat, G. Rare heterozygous genetic variants of NRXN and NLGN gene families involved in synaptic function and their association with neurodevelopmental disorders. Dev Neurobiol 2024, 84, 158–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Getz, S.A.; DeSpenza, T.; Li, M.; Luikart, B.W. Rapamycin prevents, but does not reverse, aberrant migration in Pten knockout neurons. Neurobiol Dis 2016, 93, 12–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Getz, S.A.; Tariq, K.; Marchand, D.H.; Dickson, C.R.; Howe Vi, J.R.; Skelton, P.D.; et al. PTEN Regulates Dendritic Arborization by Decreasing Microtubule Polymerization Rate. J Neurosci 2022, 42, 1945–1957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gharani, N.; Benayed, R.; Mancuso, V.; Brzustowicz, L.M.; Millonig, J.H. Association of the homeobox transcription factor, ENGRAILED 2, 3, with autism spectrum disorder. Mol Psychiatry 2004, 9, 474–484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gkogkas, C.G.; Khoutorsky, A.; Ran, I.; Rampakakis, E.; Nevarko, T.; Weatherill, D.B.; et al. Autism-related deficits via dysregulated eIF4E-dependent translational control. Nature 2013, 493, 371–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gkogkas, C.G.; Khoutorsky, A.; Ran, I.; Rampakakis, E.; Nevarko, T.; Weatherill, D.B.; et al. Autism-related deficits via dysregulated eIF4E-dependent translational control. Nature 2013, 493, 371–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glickstein, M.; Doron, K. Cerebellum: Connections and Functions. Cerebellum 2008, 7, 589–594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goffinet, A.M.; Tissir, F. Seven pass Cadherins CELSR1-3. Semin Cell Dev Biol 2017, 69, 102–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gong, X.; Wang, H. SHANK1 and autism spectrum disorders. Sci China Life Sci 2015, 58, 985–990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonzalo-Ruiz, A.; Leichnetz, G.R.; Hardy, S.G. Projections of the medial cerebellar nucleus to oculomotor-related midbrain areas in the rat: an anterograde and retrograde HRP study. J Comp Neurol 1990, 296, 427–436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goorden, S.M.I.; van Woerden, G.M.; van der Weerd, L.; Cheadle, J.P.; Elgersma, Y. Cognitive deficits in Tsc1+/- mice in the absence of cerebral lesions and seizures. Ann Neurol 2007, 62, 648–655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gordon, A.; Salomon, D.; Barak, N.; Pen, Y.; Tsoory, M.; Kimchi, T.; et al. Expression of Cntnap2 (Caspr2) in multiple levels of sensory systems. Mol Cell Neurosci 2016, 70, 42–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gould, E.; Kim, J.H. SCN2A contributes to oligodendroglia excitability and development in the mammalian brain. Cell Rep 2021, 36, 109653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gozes, I.; Bassan, M.; Zamostiano, R.; Pinhasov, A.; Davidson, A.; Giladi, E.; et al. A novel signaling molecule for neuropeptide action: activity-dependent neuroprotective protein. Ann N Y Acad Sci 1999, 897, 125–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grasselli, G.; Boele, H.-J.; Titley, H.K.; Bradford, N.; van Beers, L.; Jay, L.; et al. SK2 channels in cerebellar Purkinje cells contribute to excitability modulation in motor-learning-specific memory traces. PLoS Biol 2020, 18, e3000596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grasselli, G.; He, Q.; Wan, V.; Adelman, J.P.; Ohtsuki, G.; Hansel, C. Activity-Dependent Plasticity of Spike Pauses in Cerebellar Purkinje Cells. Cell Rep 2016, 14, 2546–2553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grayton, H.M.; Missler, M.; Collier, D.A.; Fernandes, C. Altered social behaviours in neurexin 1α knockout mice resemble core symptoms in neurodevelopmental disorders. PLoS One 2013, 8, e67114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Greer, J.M.; Wynshaw-Boris, A. Pten and the brain: sizing up social interaction. Neuron 2006, 50, 343–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grove, J.; Ripke, S.; Als, T.D.; Mattheisen, M.; Walters, R.K.; Won, H.; et al. Identification of common genetic risk variants for autism spectrum disorder. Nat Genet 2019, 51, 431–444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guerra, M.; Medici, V.; Weatheritt, R.; Corvino, V.; Palacios, D.; Geloso, M.C.; et al. Fetal exposure to valproic acid dysregulates the expression of autism-linked genes in the developing cerebellum. Transl Psychiatry 2023, 13, 114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guerrero-Morín, J.G.; Santillán, M. Crosstalk dynamics between the circadian clock and the mTORC1 pathway. J Theor Biol 2020, 501, 110360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guissart, C.; Latypova, X.; Rollier, P.; Khan, T.N.; Stamberger, H.; McWalter, K.; et al. Dual Molecular Effects of Dominant RORA Mutations Cause Two Variants of Syndromic Intellectual Disability with Either Autism or Cerebellar Ataxia. Am J Hum Genet 2018, 102, 744–759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gustin, R.M.; Bichell, T.J.; Bubser, M.; Daily, J.; Filonova, I.; Mrelashvili, D.; et al. Tissue-specific variation of Ube3a protein expression in rodents and in a mouse model of Angelman syndrome. Neurobiol Dis 2010, 39, 283–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gzielo, K.; Nikiforuk, A. Astroglia in Autism Spectrum Disorder. Int J Mol Sci 2021, 22, 11544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- H, X.; Y, Y.; X, T.; M, Z.; F, L.; P, X.; et al. Bergmann glia function in granule cell migration during cerebellum development. Molecular neurobiology 2013, 47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hampson, D.R.; Blatt, G.J. Autism spectrum disorders and neuropathology of the cerebellum. Front Neurosci 2015, 9, 420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, V.X.; Patel, S.; Jones, H.F.; Dale, R.C. Maternal immune activation and neuroinflammation in human neurodevelopmental disorders. Nat Rev Neurol 2021, 17, 564–579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanzel, M.; Fernando, K.; Maloney, S.E.; Horn, Z.; Gong, S.; Mätlik, K.; et al. Mice lacking Astn2 have ASD-like behaviors and altered cerebellar circuit properties. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2024, 121, e2405901121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hao, X.; Sun, J.; Zhong, L.; Baudry, M.; Bi, X. UBE3A deficiency-induced autophagy is associated with activation of AMPK-ULK1 and p53 pathways. Exp Neurol 2023, 363, 114358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harkin, L.F.; Lindsay, S.J.; Xu, Y.; Alzu’bi, A.; Ferrara, A.; Gullon, E.A.; et al. Neurexins 1-3 Each Have a Distinct Pattern of Expression in the Early Developing Human Cerebral Cortex. Cereb Cortex 2017, 27, 216–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Harrison, A.J.; Gamsiz, E.D.; Berkowitz, I.C.; Nagpal, S.; Jerskey, B.A. Genetic variation in the oxytocin receptor gene is associated with a social phenotype in autism spectrum disorders. Am J Med Genet B Neuropsychiatr Genet 2015, 168, 720–729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hatten, M.E. Adding cognitive connections to the cerebellum. Science 2020, 370, 1411–1412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Havdahl, A.; Niarchou, M.; Starnawska, A.; Uddin, M.; van der Merwe, C.; Warrier, V. Genetic contributions to autism spectrum disorder. Psychol Med 2021, 51, 2260–2273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haws, M.E.; Jaramillo, T.C.; Espinosa, F.; Widman, A.J.; Stuber, G.D.; Sparta, D.R.; et al. PTEN knockdown alters dendritic spine/protrusion morphology, not density. J Comp Neurol 2014, 522, 1171–1190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, X.; Sanders, S.J.; Liu, L.; De Rubeis, S.; Lim, E.T.; Sutcliffe, J.S.; et al. Integrated model of de novo and inherited genetic variants yields greater power to identify risk genes. PLoS Genet 2013, 9, e1003671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herman, G.E.; Butter, E.; Enrile, B.; Pastore, M.; Prior, T.W.; Sommer, A. Increasing knowledge of PTEN germline mutations: Two additional patients with autism and macrocephaly. Am J Med Genet A 2007, 143A, 589–593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ho, A.; Towheed, A.; Luong, S.; Zucker, S.; Fethke, E. Clinical Discordance in Monozygotic Twins With Autism Spectrum Disorder. Cureus 2022, 14, e24813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hoon, M.; Soykan, T.; Falkenburger, B.; Hammer, M.; Patrizi, A.; Schmidt, K.-F.; et al. Neuroligin-4 is localized to glycinergic postsynapses and regulates inhibition in the retina. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2011, 108, 3053–3058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hooshmandi, M.; Truong, V.T.; Fields, E.; Thomas, R.E.; Wong, C.; Sharma, V.; et al. 4E-BP2-dependent translation in cerebellar Purkinje cells controls spatial memory but not autism-like behaviors. Cell Rep 2021, 35, 109036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hörnberg, H.; Pérez-Garci, E.; Schreiner, D.; Hatstatt-Burklé, L.; Magara, F.; Baudouin, S.; et al. Rescue of oxytocin response and social behaviour in a mouse model of autism. Nature 2020, 584, 252–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, V.W.; Sarachana, T.; Kim, K.S.; Nguyen, A.; Kulkarni, S.; Steinberg, M.E.; et al. Gene expression profiling differentiates autism case-controls and phenotypic variants of autism spectrum disorders: evidence for circadian rhythm dysfunction in severe autism. Autism Res 2009, 2, 78–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, V.W.; Sarachana, T.; Sherrard, R.M.; Kocher, K.M. Investigation of sex differences in the expression of RORA and its transcriptional targets in the brain as a potential contributor to the sex bias in autism. Mol Autism 2015, 6, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hughes, H.K.; R J Moreno, null, and Ashwood, P. Innate immune dysfunction and neuroinflammation in autism spectrum disorder (ASD). Brain Behav Immun 2023, 108, 245–254. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huntley, G.W.; Gil, O.; Bozdagi, O. The cadherin family of cell adhesion molecules: multiple roles in synaptic plasticity. Neuroscientist 2002, 8, 221–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hussman, J.P.; Chung, R.-H.; Griswold, A.J.; Jaworski, J.M.; Salyakina, D.; Ma, D.; et al. A noise-reduction GWAS analysis implicates altered regulation of neurite outgrowth and guidance in autism. Molecular Autism 2011, 2, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Igarashi, A.; Itoh, K.; Yamada, T.; Adachi, Y.; Kato, T.; Murata, D.; et al. Nuclear PTEN deficiency causes microcephaly with decreased neuronal soma size and increased seizure susceptibility. J Biol Chem 2018, 293, 9292–9300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ikawa, D.; Makinodan, M.; Iwata, K.; Ohgidani, M.; Kato, T.A.; Yamashita, Y.; et al. Microglia-derived neuregulin expression in psychiatric disorders. Brain Behav Immun 2017, 61, 375–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Inutsuka, A.; Hattori, A.; Yoshida, M.; Takayanagi, Y.; Onaka, T. Cerebellar damage with inflammation upregulates oxytocin receptor expression in Bergmann Glia. Molecular Brain 2024, 17, 41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iweka, C.A.; Seigneur, E.; Hernandez, A.L.; Paredes, S.H.; Cabrera, M.; Blacher, E.; et al. Myeloid deficiency of the intrinsic clock protein BMAL1 accelerates cognitive aging by disrupting microglial synaptic pruning. J Neuroinflammation 2023, 20, 48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- J, L.; C, C.; S, H.; D, L.; Dy, K.; H, K.; et al. Shank3-mutant mice lacking exon 9 show altered excitation/inhibition balance, enhanced rearing, and spatial memory deficit. Frontiers in cellular neuroscience 2015, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaber, M. Genetic and environmental mouse models of autism reproduce the spectrum of the disease. J Neural Transm (Vienna) 2023, 130, 425–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacot-Descombes, S.; Keshav, N.U.; Dickstein, D.L.; Wicinski, B.; Janssen, W.G.M.; Hiester, L.L.; et al. Altered synaptic ultrastructure in the prefrontal cortex of Shank3-deficient rats. Mol Autism 2020, 11, 89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jamain, S.; Quach, H.; Betancur, C.; Råstam, M.; Colineaux, C.; Gillberg, I.C.; et al. Mutations of the X-linked genes encoding neuroligins NLGN3 and NLGN4 are associated with autism. Nat Genet 2003, 34, 27–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jamain, S.; Radyushkin, K.; Hammerschmidt, K.; Granon, S.; Boretius, S.; Varoqueaux, F.; et al. Reduced social interaction and ultrasonic communication in a mouse model of monogenic heritable autism. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2008, 105, 1710–1715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- James, S.J.; Shpyleva, S.; Melnyk, S.; Pavliv, O.; Pogribny, I.P. Complex epigenetic regulation of engrailed-2 (EN-2) homeobox gene in the autism cerebellum. Transl Psychiatry 2013, 3, e232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- James, S.J.; Shpyleva, S.; Melnyk, S.; Pavliv, O.; Pogribny, I.P. Elevated 5-hydroxymethylcytosine in the Engrailed-2 (EN-2) promoter is associated with increased gene expression and decreased MeCP2 binding in autism cerebellum. Transl Psychiatry 2014, 4, e460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jameson, C.; Boulton, K.A.; Silove, N.; Guastella, A.J. Eczema and related atopic diseases are associated with increased symptom severity in children with autism spectrum disorder. Transl Psychiatry 2022, 12, 415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jankowski, J.; Holst, M.I.; Liebig, C.; Oberdick, J.; Baader, S.L. Engrailed-2 negatively regulates the onset of perinatal Purkinje cell differentiation. J Comp Neurol 2004, 472, 87–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaramillo, T.C.; Escamilla, C.O.; Liu, S.; Peca, L.; Birnbaum, S.G.; Powell, C.M. Genetic background effects in Neuroligin-3 mutant mice: Minimal behavioral abnormalities on C57 background. Autism Res 2018, 11, 234–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jarvis, C.I.; Staels, B.; Brugg, B.; Lemaigre-Dubreuil, Y.; Tedgui, A.; Mariani, J. Age-related phenotypes in the staggerer mouse expand the RORα nuclear receptor’s role beyond the cerebellum. Molecular and Cellular Endocrinology 2002, 186, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, N.; Burkard, M.E. MACROD2, an Original Cause of CIN? Cancer Discovery 2018, 8, 921–923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, X.; Simmons, S.K.; Guo, A.; Shetty, A.S.; Ko, M.; Nguyen, L.; et al. In vivo Perturb-Seq reveals neuronal and glial abnormalities associated with autism risk genes. Science 2020, 370, eaaz6063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jobson, K.R.; Hoffman, L.J.; Metoki, A.; Popal, H.; Dick, A.S.; Reilly, J.; et al. Language and the Cerebellum: Structural Connectivity to the Eloquent Brain. Neurobiol Lang (Camb) 2024, 5, 652–675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, K.P.; Zarrinnegar, P. Autism Spectrum Disorder and Sleep. Psychiatr Clin North Am 2024, 47, 199–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jones, C.; Barrera, I.; Brothers, S.; Ring, R.; Wahlestedt, C. Oxytocin and social functioning. Dialogues Clin Neurosci 2017, 19, 193–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, R.M.; Cadby, G.; Blangero, J.; Abraham, L.J.; Whitehouse, A.J.O.; Moses, E.K. MACROD2 gene associated with autistic-like traits in a general population sample. Psychiatr Genet 2014, 24, 241–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Journiac, N.; Jolly, S.; Jarvis, C.; Gautheron, V.; Rogard, M.; Trembleau, A.; et al. The nuclear receptor ROR(alpha) exerts a bi-directional regulation of IL-6 in resting and reactive astrocytes. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2009, 106, 21365–21370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joyner, A.L.; Herrup, K.; Auerbach, B.A.; Davis, C.A.; Rossant, J. Subtle cerebellar phenotype in mice homozygous for a targeted deletion of the En-2 homeobox. Science 1991, 251, 1239–1243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kanner, L.; Lesser, L.I. Early infantile autism. Pediatr Clin North Am 1958, 5, 711–730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kaplanis, J.; Samocha, K.E.; Wiel, L.; Zhang, Z.; Arvai, K.J.; Eberhardt, R.Y.; et al. Evidence for 28 genetic disorders discovered by combining healthcare and research data. Nature 2020, 586, 757–762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kareklas, K.; Teles, M.C.; Dreosti, E.; Oliveira, R.F. Autism-associated gene shank3 is necessary for social contagion in zebrafish. Mol Autism 2023, 14, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kasah, S.; Oddy, C.; Basson, M.A. Autism-linked CHD gene expression patterns during development predict multi-organ disease phenotypes. J Anat 2018, 233, 755–769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kasem, E.; Kurihara, T.; Tabuchi, K. Neurexins and neuropsychiatric disorders. Neurosci Res 2018, 127, 53–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kashii, H.; Kasai, S.; Sato, A.; Hagino, Y.; Nishito, Y.; Kobayashi, T.; et al. Tsc2 mutation rather than Tsc1 mutation dominantly causes a social deficit in a mouse model of tuberous sclerosis complex. Hum Genomics 2023, 17, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kawamura, A.; Katayama, Y.; Kakegawa, W.; Ino, D.; Nishiyama, M.; Yuzaki, M.; et al. The autism-associated protein CHD8 is required for cerebellar development and motor function. Cell Rep 2021, 35, 108932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kebschull, J.M.; Richman, E.B.; Ringach, N.; Friedmann, D.; Albarran, E.; Kolluru, S.S.; et al. Cerebellar nuclei evolved by repeatedly duplicating a conserved cell-type set. Science 2020, 370, eabd5059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kelly, E.; Meng, F.; Fujita, H.; Morgado, F.; Kazemi, Y.; Rice, L.C.; et al. Regulation of autism-relevant behaviors by cerebellar-prefrontal cortical circuits. Nat Neurosci 2020, 23, 1102–1110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kern, J.K.; Geier, D.A.; Audhya, T.; King, P.G.; Sykes, L.K.; Geier, M.R. Evidence of parallels between mercury intoxication and the brain pathology in autism. Acta Neurobiol Exp (Wars) 2012, 72, 113–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, A.J.; Nair, A.; Keown, C.L.; Datko, M.C.; Lincoln, A.J.; Müller, R.-A. Cerebro-cerebellar Resting-State Functional Connectivity in Children and Adolescents with Autism Spectrum Disorder. Biol Psychiatry 2015, 78, 625–634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khoja, S.; Haile, M.T.; Chen, L.Y. Advances in neurexin studies and the emerging role of neurexin-2 in autism spectrum disorder. Front Mol Neurosci 2023, 16, 1125087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.-J.; Cho, M.-H.; Shim, W.H.; Kim, J.K.; Jeon, E.-Y.; Kim, D.-H.; et al. Deficient autophagy in microglia impairs synaptic pruning and causes social behavioral defects. Mol Psychiatry 2017, 22, 1576–1584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, J.H.; Liao, D.; Lau, L.F.; Huganir, R.L. SynGAP: a synaptic RasGAP that associates with the PSD-95/SAP90 protein family. Neuron 1998, 20, 683–691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- King, M.; Hernandez-Castillo, C.R.; Poldrack, R.A.; Ivry, R.B.; Diedrichsen, J. Functional boundaries in the human cerebellum revealed by a multi-domain task battery. Nat Neurosci 2019, 22, 1371–1378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kiser, D.P.; Popp, S.; Schmitt-Böhrer, A.G.; Strekalova, T.; van den Hove, D.L.; Lesch, K.-P.; et al. Early-life stress impairs developmental programming in Cadherin 13 (CDH13)-deficient mice. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry 2019, 89, 158–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kloth, A.D.; Badura, A.; Li, A.; Cherskov, A.; Connolly, S.G.; Giovannucci, A.; et al. Cerebellar associative sensory learning defects in five mouse autism models. Elife 2015, 4, e06085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koehnke, J.; Katsamba, P.S.; Ahlsen, G.; Bahna, F.; Vendome, J.; Honig, B.; et al. Splice form dependence of beta-neurexin/neuroligin binding interactions. Neuron 2010, 67, 61–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koyama, R.; Ikegaya, Y. Microglia in the pathogenesis of autism spectrum disorders. Neurosci Res 2015, 100, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Krishnamurthy, A.; Lee, A.S.; Bayin, N.S.; Stephen, D.N.; Nasef, O.; Lao, Z.; et al. Engrailed transcription factors direct excitatory cerebellar neuron diversity and survival. Development 2024, 151, dev202502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kshetri, R.; Beavers, J.O.; Hyde, R.; Ewa, R.; Schwertman, A.; Porcayo, S.; et al. Behavioral decline in Shank3Δex4-22 mice during early adulthood parallels cerebellar granule cell glutamatergic synaptic changes. Mol Autism 2024, 15, 52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kuemerle, B.; Zanjani, H.; Joyner, A.; Herrup, K. Pattern deformities and cell loss in Engrailed-2 mutant mice suggest two separate patterning events during cerebellar development. J Neurosci 1997, 17, 7881–7889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kumar, A.; LaVoie, H.A.; DiPette, D.J.; Singh, U.S. Ethanol neurotoxicity in the developing cerebellum: underlying mechanisms and implications. Brain Sci 2013, 3, 941–963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, R.A.; Christian, S.L. Genetics of autism spectrum disorders. Curr Neurol Neurosci Rep 2009, 9, 188–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kútna, V.; O’Leary, V.B.; Hoschl, C.; Ovsepian, S.V. Cerebellar demyelination and neurodegeneration associated with mTORC1 hyperactivity may contribute to the developmental onset of autism-like neurobehavioral phenotype in a rat model. Autism Res 2022, 15, 791–805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwon, C.H.; Zhu, X.; Zhang, J.; Knoop, L.L.; Tharp, R.; Smeyne, R.J.; et al. Pten regulates neuronal soma size: a mouse model of Lhermitte-Duclos disease. Nat Genet 2001, 29, 404–411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwon, C.-H.; Luikart, B.W.; Powell, C.M.; Zhou, J.; Matheny, S.A.; Zhang, W.; et al. Pten regulates neuronal arborization and social interaction in mice. Neuron 2006, 50, 377–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwon, H.-K.; Choi, G.B.; Huh, J.R. Maternal inflammation and its ramifications on fetal neurodevelopment. Trends Immunol 2022, 43, 230–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lai, E.S.K.; Nakayama, H.; Miyazaki, T.; Nakazawa, T.; Tabuchi, K.; Hashimoto, K.; et al. An Autism-Associated Neuroligin-3 Mutation Affects Developmental Synapse Elimination in the Cerebellum. Front Neural Circuits 2021, 15, 676891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lainhart, J.E.; Bigler, E.D.; Bocian, M.; Coon, H.; Dinh, E.; Dawson, G.; et al. Head circumference and height in autism: a study by the Collaborative Program of Excellence in Autism. Am J Med Genet A 2006, 140, 2257–2274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lazzarini, G.; Gatta, A.; Miragliotta, V.; Vaglini, F.; Viaggi, C.; Pirone, A. Glial cells are affected more than interneurons by the loss of Engrailed 2 gene in the mouse cerebellum. J Anat 2024, 244, 667–675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leblond, C.S.; Nava, C.; Polge, A.; Gauthier, J.; Huguet, G.; Lumbroso, S.; et al. Meta-analysis of SHANK Mutations in Autism Spectrum Disorders: a gradient of severity in cognitive impairments. PLoS Genet 2014, 10, e1004580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ledonne, A.; Mercuri, N.B. On the Modulatory Roles of Neuregulins/ErbB Signaling on Synaptic Plasticity. Int J Mol Sci 2019, 21, 275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lemke, G. Neuregulins in development. Mol Cell Neurosci 1996, 7, 247–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leto, K.; Arancillo, M.; Becker, E.B.E.; Buffo, A.; Chiang, C.; Ding, B.; et al. Consensus Paper: Cerebellar Development. Cerebellum 2016, 15, 789–828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levy, S.E.; Mandell, D.S.; Schultz, R.T. Autism. Lancet 2009, 374, 1627–1638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, E.; Li, X.; Huang, J.; Xu, C.; Liang, Q.; Ren, K.; et al. BMAL1 regulates mitochondrial fission and mitophagy through mitochondrial protein BNIP3 and is critical in the development of dilated cardiomyopathy. Protein Cell 2020, 11, 661–679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Fan, L.; Luo, R.; Yang, Z.; Yuan, M.; Zhang, J.; et al. Case Report: De novo Variants of KMT2E Cause O’Donnell-Luria-Rodan Syndrome: Additional Cases and Literature Review. Front Pediatr 2021, 9, 641841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.-J.; Li, C.-Y.; Li, C.-Y.; Hu, D.-X.; Xv, Z.-B.; Zhang, S.-H.; et al. KMT2E Haploinsufficiency Manifests Autism-Like Behaviors and Amygdala Neuronal Development Dysfunction in Mice. Mol Neurobiol 2023, 60, 1609–1625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Licatalosi, D.D.; Yano, M.; Fak, J.J.; Mele, A.; Grabinski, S.E.; Zhang, C.; et al. Ptbp2 represses adult-specific splicing to regulate the generation of neuronal precursors in the embryonic brain. Genes Dev 2012, 26, 1626–1642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lichtenstein, P.; Carlström, E.; Råstam, M.; Gillberg, C.; Anckarsäter, H. The genetics of autism spectrum disorders and related neuropsychiatric disorders in childhood. Am J Psychiatry 2010, 167, 1357–1363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin, Y.-C.; Frei, J.A.; Kilander, M.B.C.; Shen, W.; Blatt, G.J. A Subset of Autism-Associated Genes Regulate the Structural Stability of Neurons. Front Cell Neurosci 2016, 10, 263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Linnerbauer, M.; Wheeler, M.A.; Quintana, F.J. Astrocyte Crosstalk in CNS Inflammation. Neuron 2020, 108, 608–622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lionel, A.C.; Tammimies, K.; Vaags, A.K.; Rosenfeld, J.A.; Ahn, J.W.; Merico, D.; et al. Disruption of the ASTN2/TRIM32 locus at 9q33.1 is a risk factor in males for autism spectrum disorders, ADHD and other neurodevelopmental phenotypes. Hum Mol Genet 2014, 23, 2752–2768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lipton, J.O.; Boyle, L.M.; Yuan, E.D.; Hochstrasser, K.J.; Chifamba, F.F.; Nathan, A.; et al. Aberrant Proteostasis of BMAL1 Underlies Circadian Abnormalities in a Paradigmatic mTOR-opathy. Cell Rep 2017, 20, 868–880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, D.; Nanclares, C.; Simbriger, K.; Fang, K.; Lorsung, E.; Le, N.; et al. Autistic-like behavior and cerebellar dysfunction in Bmal1 mutant mice ameliorated by mTORC1 inhibition. Mol Psychiatry 2023, 28, 3727–3738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, W.-W.; Wei, S.-Z.; Huang, G.-D.; Liu, L.-B.; Gu, C.; Shen, Y.; et al. BMAL1 regulation of microglia-mediated neuroinflammation in MPTP-induced Parkinson’s disease mouse model. FASEB J 2020, 34, 6570–6581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Long, J.; Dang, H.; Su, W.; Moneruzzaman, M.; Zhang, H. Interactions between circulating inflammatory factors and autism spectrum disorder: a bidirectional Mendelian randomization study in European population. Front. Immunol. 2024, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Longart, M.; Liu, Y.; Karavanova, I.; Buonanno, A. Neuregulin-2 is developmentally regulated and targeted to dendrites of central neurons. J Comp Neurol 2004, 472, 156–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- LoParo, D.; Waldman, I.D. The oxytocin receptor gene (OXTR) is associated with autism spectrum disorder: a meta-analysis. Mol Psychiatry 2015, 20, 640–646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lord, C.; Brugha, T.S.; Charman, T.; Cusack, J.; Dumas, G.; Frazier, T.; et al. Autism spectrum disorder. Nat Rev Dis Primers 2020, 6, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lordkipanidze, T.; Dunaevsky, A. Purkinje cell dendrites grow in alignment with Bergmann glia. Glia 2005, 51, 229–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luikart, B.W.; Schnell, E.; Washburn, E.K.; Bensen, A.L.; Tovar, K.R.; Westbrook, G.L. Pten knockdown in vivo increases excitatory drive onto dentate granule cells. J Neurosci 2011, 31, 4345–4354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Luo, J.; Treubert-Zimmermann, U.; Redies, C. Cadherins guide migrating Purkinje cells to specific parasagittal domains during cerebellar development. Mol Cell Neurosci 2004, 25, 138–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, S.Y.; Kwan, K.M. Size anomaly and alteration of GABAergic enzymes expressions in cerebellum of a valproic acid mouse model of autism. Behav Brain Res 2022, 428, 113896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maden, M. Retinoic acid in the development, regeneration and maintenance of the nervous system. Nat Rev Neurosci 2007, 8, 755–765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maden, M.; Holder, N. The involvement of retinoic acid in the development of the vertebrate central nervous system. Dev Suppl 1991, Suppl 2, 87–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maden, M.; Holder, N. Retinoic acid and development of the central nervous system. Bioessays 1992, 14, 431–438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Man, M.-Q.; Yang, S.; Mauro, T.M.; Zhang, G.; Zhu, T. Link between the skin and autism spectrum disorder. Front Psychiatry 2023, 14, 1265472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marco, E.J.; Hinkley, L.B.N.; Hill, S.S.; Nagarajan, S.S. Sensory processing in autism: a review of neurophysiologic findings. Pediatr Res 2011, 69, 48R–54R. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marino, S.; Krimpenfort, P.; Leung, C.; van der Korput, H.A.G.M.; Trapman, J.; Camenisch, I.; et al. PTEN is essential for cell migration but not for fate determination and tumourigenesis in the cerebellum. Development 2002, 129, 3513–3522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marro, S.G.; Chanda, S.; Yang, N.; Janas, J.A.; Valperga, G.; Trotter, J.; et al. Neuroligin-4 Regulates Excitatory Synaptic Transmission in Human Neurons. Neuron 2019, 103, 617–626.e6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, L.A.; Goldowitz, D.; Mittleman, G. Repetitive behavior and increased activity in mice with Purkinje cell loss: a model for understanding the role of cerebellar pathology in autism. Eur J Neurosci 2010, 31, 544–555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mashayekhi, F.; Mizban, N.; Bidabadi, E.; Salehi, Z. The association of SHANK3 gene polymorphism and autism. Minerva Pediatr (Torino) 2021, 73, 251–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masi, A.; DeMayo, M.M.; Glozier, N.; Guastella, A.J. An Overview of Autism Spectrum Disorder, Heterogeneity and Treatment Options. Neurosci Bull 2017, 33, 183–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masini, E.; Loi, E.; Vega-Benedetti, A.F.; Carta, M.; Doneddu, G.; Fadda, R.; et al. An Overview of the Main Genetic, Epigenetic and Environmental Factors Involved in Autism Spectrum Disorder Focusing on Synaptic Activity. Int J Mol Sci 2020, 21, 8290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Matta, S.M.; Hill-Yardin, E.L.; Crack, P.J. The influence of neuroinflammation in Autism Spectrum Disorder. Brain Behav Immun 2019, 79, 75–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McDonald, N.M.; Varcin, K.J.; Bhatt, R.; Wu, J.Y.; Sahin, M.; Nelson, C.A.; et al. Early autism symptoms in infants with tuberous sclerosis complex. Autism Res 2017, 10, 1981–1990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McKee, C.A.; Polino, A.J.; King, M.W.; Musiek, E.S. Circadian clock protein BMAL1 broadly influences autophagy and endolysosomal function in astrocytes. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2023, 120, e2220551120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McKinney, W.S.; Kelly, S.E.; Unruh, K.E.; Shafer, R.L.; Sweeney, J.A.; Styner, M.; et al. Cerebellar Volumes and Sensorimotor Behavior in Autism Spectrum Disorder. Front Integr Neurosci 2022, 16, 821109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McPartland, J.; Volkmar, F.R. Autism and related disorders. Handb Clin Neurol 2012, 106, 407–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mendoza, J.; Pévet, P.; Felder-Schmittbuhl, M.-P.; Bailly, Y.; Challet, E. The cerebellum harbors a circadian oscillator involved in food anticipation. J Neurosci 2010, 30, 1894–1904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Middleton, F.A.; Strick, P.L. Cerebellar projections to the prefrontal cortex of the primate. J Neurosci 2001, 21, 700–712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Minami, T.; Miyata, E.; Sakamoto, Y.; Yamazaki, H.; Ichida, S. Induction of metallothionein in mouse cerebellum and cerebrum with low-dose thimerosal injection. Cell Biol Toxicol 2010, 26, 143–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Missler, M.; Fernandez-Chacon, R.; Südhof, T.C. The making of neurexins. J Neurochem 1998, 71, 1339–1347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitoma, H.; Manto, M.; Shaikh, A.G. Alcohol Toxicity in the Developing Cerebellum. Diagnostics (Basel) 2024, 14, 1415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitz, A.R.; Boccuto, L.; Thurm, A. Evidence for common mechanisms of pathology between SHANK3 and other genes of Phelan-McDermid syndrome. Clin Genet 2024, 105, 459–469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mizukami, T.; Kohno, T.; Hattori, M. CUB and Sushi multiple domains 3 regulates dendrite development. Neurosci Res 2016, 110, 11–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Modabbernia, A.; Velthorst, E.; Reichenberg, A. Environmental risk factors for autism: an evidence-based review of systematic reviews and meta-analyses. Mol Autism 2017, 8, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moessner, R.; Marshall, C.R.; Sutcliffe, J.S.; Skaug, J.; Pinto, D.; Vincent, J.; et al. Contribution of SHANK3 mutations to autism spectrum disorder. Am J Hum Genet 2007, 81, 1289–1297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monteiro, P.; Feng, G. SHANK proteins: roles at the synapse and in autism spectrum disorder. Nat Rev Neurosci 2017, 18, 147–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morabito, S.; Reese, F.; Rahimzadeh, N.; Miyoshi, E.; Swarup, V. hdWGCNA identifies co-expression networks in high-dimensional transcriptomics data. Cell Rep Method s 2023, 3, 100498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moramarco, F.; McCaffery, P. Retinoic acid regulation of homoeostatic synaptic plasticity and its relationship to cognitive disorders. J Mol Endocrinol 2024, 72, e220177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mordel, J.; Karnas, D.; Pévet, P.; Isope, P.; Challet, E.; Meissl, H. The Output Signal of Purkinje Cells of the Cerebellum and Circadian Rhythmicity. PLOS ONE 2013, 8, e58457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moss, J.; Howlin, P. Autism spectrum disorders in genetic syndromes: implications for diagnosis, intervention and understanding the wider autism spectrum disorder population. J Intellect Disabil Res 2009, 53, 852–873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muhammad, T.; Pastore, S.F.; Good, K.; Ausió, J.; Vincent, J.B. Chromatin gatekeeper and modifier CHD proteins in development, and in autism and other neurological disorders. Psychiatr Genet 2023, 33, 213–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muratori, F.; Tonacci, A.; Billeci, L.; Catalucci, T.; Igliozzi, R.; Calderoni, S.; et al. Olfactory Processing in Male Children with Autism: Atypical Odor Threshold and Identification. J Autism Dev Disord 2017, 47, 3243–3251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murray, M.; Martindale, J.M.; Otallah, S.I. SCN2A- Associated Episodic and Persistent Ataxia with Cerebellar Atrophy: A Case Report. Child Neurol Open 2023, 10, 2329048X231163944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mw, V.; Z, J.; K, M.; Al, J. The Engrailed-2 homeobox gene and patterning of spinocerebellar mossy fiber afferents. Brain research. Developmental brain research 1996, 96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagappan-Chettiar, S.; Yasuda, M.; Johnson-Venkatesh, E.M.; Umemori, H. The molecular signals that regulate activity-dependent synapse refinement in the brain. Curr Opin Neurobiol 2023, 79, 102692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nakanishi, H.; Ni, J.; Nonaka, S.; Hayashi, Y. Microglial circadian clock regulation of microglial structural complexity, dendritic spine density and inflammatory response. Neurochem Int 2021, 142, 104905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakanishi, M.; Nomura, J.; Ji, X.; Tamada, K.; Arai, T.; Takahashi, E.; et al. Functional significance of rare neuroligin 1 variants found in autism. PLoS Genet 2017, 13, e1006940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]