1. Introduction

Supersulfides are sulfur species with catenated sulfur atoms, which include hydropersulfides (RSSHs) and polysulfide species (RSSnR; n > 1, R = hydrogen, and alkyl or cyclic sulfurs) [

1,

2]. They have strong nucleophilic and antioxidant properties, surpassing those of thiols and thereby acting as redox-signaling molecules [

3,

4,

5,

6]. They also serve as electron acceptors, with cysteine hydropersulfide being reduced to H

2S in the mitochondrial electron transport chain. This process is closely associated with energy metabolism and lifespan [

4,

7]. In mammals, endogenous cysteine hydropersulfide can be synthesized by the pyridoxal 5′-phosphate (PLP)-dependent activity of cysteinyl-tRNA synthetase using cysteine as a substrate [

4,

8]. Cysteine is synthesized via the transsulfuration pathway involving the PLP-dependent enzymes, cystathionine β-synthase (CBS) and cystathionine γ-lyase (CSE), where CSE catalyzes the conversion of cystathionine, produced by CBS, into cysteine.

CSE has also been reported as another enzyme that generates cysteine hydropersulfide using cystine—instead of cysteine—as a substrate in oxidative stress conditions [

5] and produces H

2S using ergothioneine, a dietary thione/thiol that improves the health and lifespan of aged animals [

9]. CSE was upregulated in response to short-term 50% dietary restriction, contributing to oxidative stress resistance under sulfur amino acid restriction in mice [

10]. Thus, CSE may serve as a simple molecular biomarker associated with longevity [

11]. CSE can be regulated by post-translational modifications. Specific phosphorylation sites have been identified, resulting in either enhanced or reduced CSE activity under hypoxic conditions in endothelial cells [

12] or normoxic conditions in the carotid body [

13], respectively. CSE has also been identified as a cysteine-based redox-sensitive enzyme, as the endogenous

S-nitrosylation of CSE at Cys136/171 has been reported in mouse liver [

14]. In human aortic vascular smooth muscle cells, H

2O

2-triggered stable disulfide bond formation between Cys252 and Cys255 enhances the H

2S-producing activity of CSE [

15]. CSE nitration and polysulfidation have also been reported, although the significance of these site-specific modifications has yet to be fully investigated [

16,

17]. It was also shown that the physiological NO donor, S-nitrosoglutathione (GSNO), suppresses the H

2S-generating activity of human CSE from cysteine through

S-nitrosylation at Cys137 (equivalent to Cys136 in mice and rats) [

18]. We recently reported that CSE self-inactivates through polysulfidation at the Cys136 residue during cystine metabolism [

19].

Therefore, our initial objective was to determine whether GSNO can directly affect the cysteine hydropersulfide-producing activity of CSE, given that cysteine hydropersulfide can be synthesized by CSE independently of H

2S [

2,

20]. Experiments were also performed to analyze whether L-

S-nitrosocysteine (L-CysNO) affects the cysteine hydropersulfide-producing activity of CSE in the presence or absence of PLP, since L-CysNO—but not GSNO—altered this activity. We propose that L-CysNO is an endogenous CSE substrate and suggest that the reaction products, rather than acting as NO donors, are the main factors responsible for decreased CSE hydropersulfide-producing activity.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials

The cDNA for rat liver CSE was a generous gift from Dr. Nozomu Nishi [

21] (Life Science Research Center, Kagawa University, Kagawa, Japan). The anti-CSE antibody was prepared as described previously [

22]. Sulfane sulfur probe 4 (SSP4) was obtained from Dojindo laboratories (Kumamoto, Japan). All other materials and reagents were of the highest quality available from commercial suppliers.

2.2. Plasmid Construction

The rat CSE mutants C136V, 171V, or C136V/C171V (i.e., a mutant bearing both Cys136 and Cys171 replacement with Val residues) were subcloned into a pME18S vector. The nucleotide sequences of each mutant were confirmed by DNA sequencing.

2.3. CSE Purification

Recombinant rat CSE was expressed in E. coli (DH5α) using pGEX-6P and purified by using GSH accept (Nacalai Tesque, Kyoto, Japan). Protein concentrations were determined by the Bradford method, using BSA as the protein standard.

2.4. Measurement of CSE Activity

The Cys-SSH produced by CSE, with cystine as a substrate, was measured by using SSP4. We initially performed an enzyme titration curve and a time course for SSP4 assay. The experiment was performed with a cystine substrate concentration of 1 mM. The velocity was obtained from the slope of the linear part of the curve. Thus, an enzyme concentration of 50 μg/mL and assay time of 20 min were selected for the assay. Recombinant CSEs (50 μg/mL) were incubated in 20 mM Hepes (pH 7.5), containing 50 μM PLP with buffer alone or 1 mM cystine for 20 min at 37 °C. Samples of interest were reacted with 10 μM SSP4 in 20 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.4) in the presence of 1 mM cetyltrimethylammonium bromide in the dark for 10 min at room temperature. The fluorescence intensities of the resultant solutions were determined using a microplate reader (BioTek Synergy HTX Multimode Reader, Agilent Technologies, Inc., Santa Clara, CA, U.S.A.) with excitation and emission wavelengths of 485/20 nm and 528/20 nm, respectively. In some studies, it was necessary to remove the polysulfide donor which reacts with SSP4 and reducing agent, which decomposes Cys-SSH produced by CSE to cysteine. Thus, we established an immobilized CSE assay. GST-CSE was expressed for use in E. coli (DH5α) using pGEX-6P, which was subsequently immobilized with GSH-agarose. Cys-SSH and Na2S4 treatments and reducing agents were removed by centrifugation, and immobilized CSE was washed three times with 50 mM Hepes (pH 7.5), followed by incubation with 50 µM PLP, as well as 1 mM cystine, at 37 °C for 20 min. The Cys-SSH contents in the samples of interest were analyzed, as described above. The cysteine produced by CSE from cystathionine was measured by DTNB assay. Briefly, purified CSEs (30 μg/mL) were incubated with 1 mM cystathionine in 40 mM borate buffer (pH 8.2), containing 50 µM PLP and 1 mM DTNB at 30 °C for 10 min. We measured the absorption development at 412 nm due to the formation of the nitrobenzene thiolate anion.

2.5. HSNO Measurement Using TAP-1

The HSNO produced by CSE from CSNO as a substrate was measured by using TAP-1 [

23]. The experiment was performed with a substrate concentration of 1 mM CSNO. Thus, an enzyme concentration of 50 μg/mL and assay time of 20 min were selected for the assay. Recombinant CSEs (50 μg/mL) were incubated in 20 mM Hepes (pH 7.5), containing 50 μM PLP with buffer alone or 1 mM cystine for 20 min at 37 °C. Samples of interest were reacted with 10 μM TAP-1 in 20 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.4) in the presence of 1 mM cetyltrimethylammonium bromide in the dark for 10 min at room temperature. The fluorescence intensities of the resultant solutions were determined using a microplate reader (BioTek Synergy HTX Multimode Reader, Agilent Technologies, Inc., Santa Clara, CA, U.S.A.) with excitation and emission wavelengths of 485/20 nm and 528/20 nm, respectively.

2.6. Live-Cell Fluorescence Imaging of Cys-SSH

COS-7 cells were cultured in Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle Medium (DMEM) supplemented with 10% fetal calf serum (FBS) and 1% penicillin–streptomycin, under humidified conditions at 37 °C. Cells were initially plated onto 6 cm dishes at a density of 5 × 10⁵ cells per dish. Transient transfection was carried out using Lipofectamine 3000 (Thermo Fisher Scientific). In brief, 1 µg of plasmid DNA was mixed with 2 µL of P3000 reagent and 3 µL of Lipofectamine 3000 in Opti-MEM, which was then added to the cells. After 24 hours of incubation, transfected COS-7 cells were re-plated for imaging and protein analysis: 5 × 10⁴ cells per well in an eight-well chamber slide (µ-Slide 8 Well High, ibidi GmbH, Gräfelfing, Germany) for microscopy, and 5 × 10⁵ cells per 6 cm dish for Western blotting. Following an additional 48-hour incubation, the cells were rinsed once with serum-free DMEM, then incubated for 15 minutes at 37 °C with 20 µM SSP4 in serum-free DMEM containing 500 µM cetyltrimethylammonium bromide. Excess probe was removed by washing the cells with HBSS. Fluorescence imaging was performed using a Nikon A1R+ confocal laser scanning microscope mounted on an ECLIPSE Ti-E inverted microscope equipped with a 20× objective lens. The excitation wavelength was set to 488 nm and emission was detected at 500/50 nm. Image fluorescence intensity was quantified using NIS-Elements software (Nikon, Tokyo, Japan).

3. Results

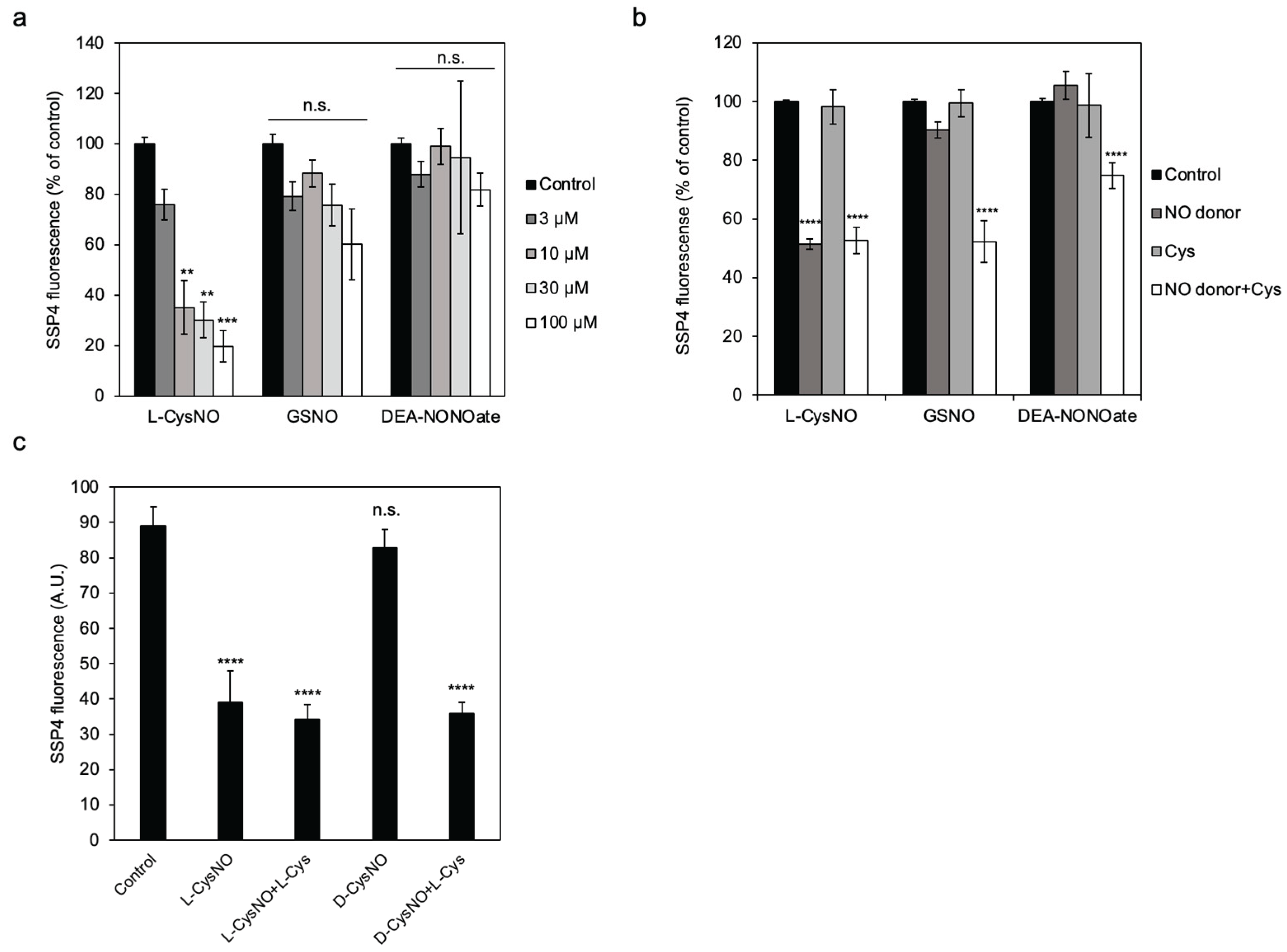

3.1. L-CysNO, but Not Other NO Donors, Inhibits CSE’s Cysteine Hydropersulfide-Producing Activity

It was shown that CSE-mediated H

2S production was inhibited by either diethylamine (DEA)-NONOate or GSNO when cysteine was used as a substrate [

18,

24]. Therefore, we first evaluated the ability of these NO-donors, along with L-CysNO, to inhibit the cysteine hydropersulfide-producing activity of CSE; this was achieved using cystine as a substrate and a sulfur-specific fluorescent probe, SSP4. When we tested the effect of various concentrations of L-CysNO on CSE activity, suppression was shown to occur in a dose-dependent manner, with an apparent IC

50 value of 10 µM (

Figure 1a). Although DEA-NONOate or GSNO alone did not inhibit CSE activity, the co-incubation of these NO-donors with L-cysteine resulted in attenuated CSE activity (

Figure 1b). Next, we determined whether D-CysNO, a stereoisomer of L-CysNO, could also inhibit CSE activity. Although equal amounts of D-CysNO and L-CysNO produced a similar amount of NO (data not shown), L-CysNO alone inhibited CSE activity, whereas D-CysNO inhibited it only in the presence of L-Cys (

Figure 1c).

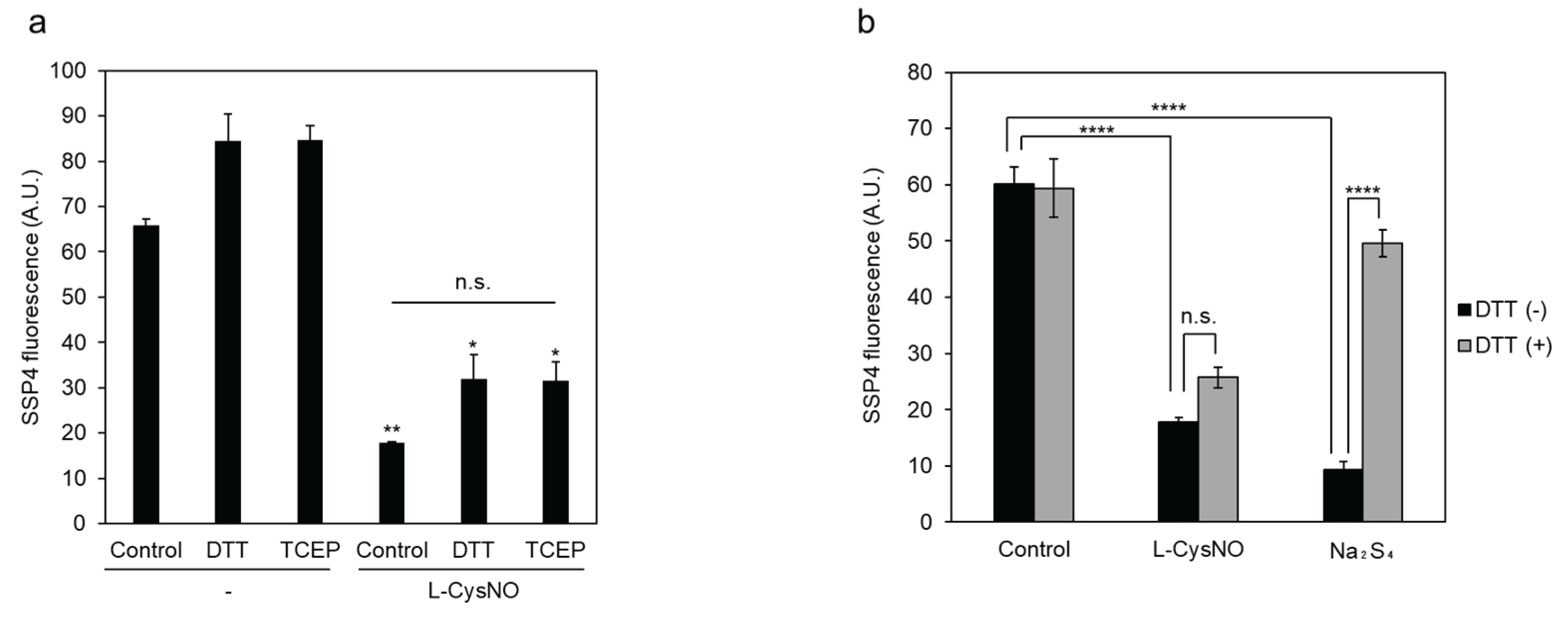

Since both protein

S-nitrosylation and polysulfidation have been described as reversible post-translational modifications, immobilized CSE/L-CysNO treatment coupled with reducing agents was performed to check the reversibility of CSE inhibition by L-CysNO. L-CysNO-induced CSE inhibition was not restored by post-addition of either a thiol-containing reducing agent dithiothreitol (DTT) or a thiol-free reducing agent Tris (2-carboxyethyl) phosphine (TCEP) (

Figure 2a). As noted in our earlier study, immobilized CSE pretreatment with 10 μM Na

2S

4 resulted in suppressed β-lyase activity toward cystine via polysulfidation, which was restored upon DTT addition (

Figure 2b). These results suggest that the formation of L-CysNO, rather than the NO-donors themselves, is required to irreversibly suppress CSE activity when cystine is used as a substrate.

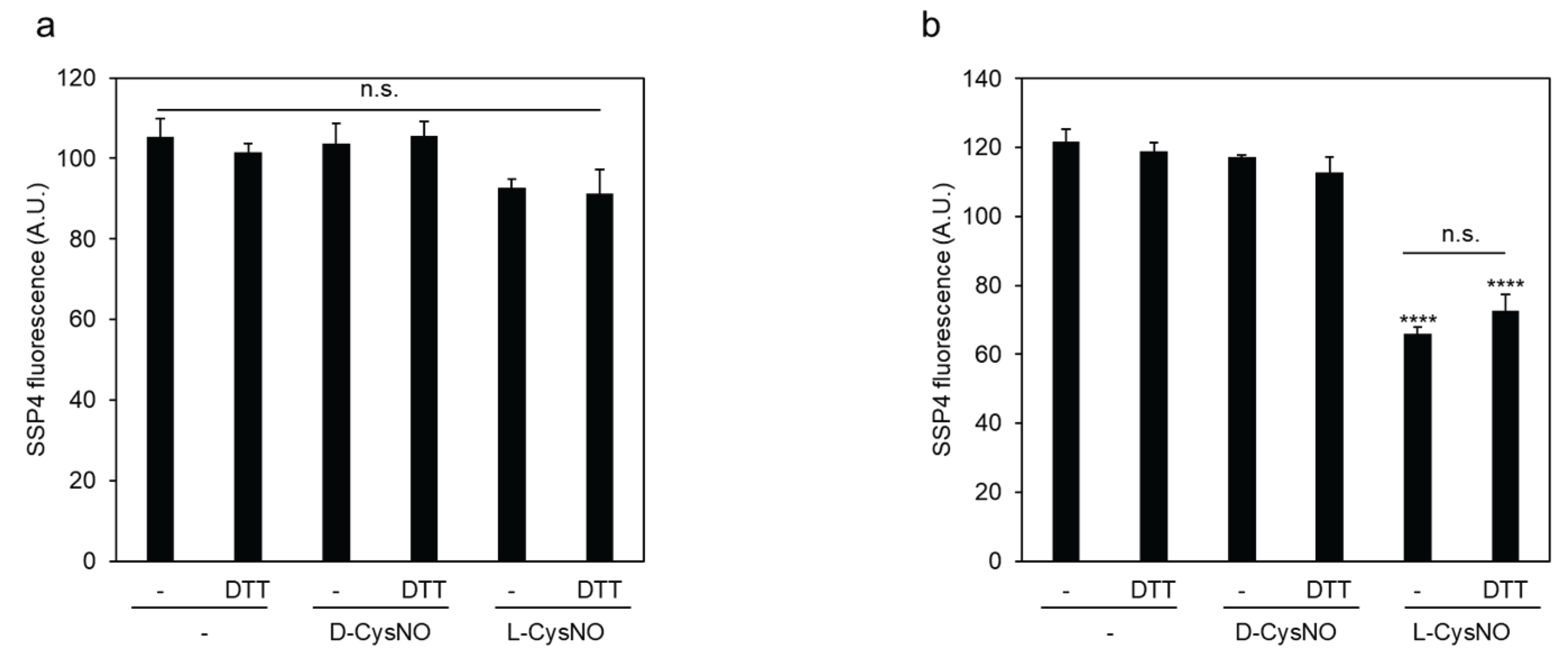

3.2. CSE Activity Inhibition by L-CysNO Requires the Presence of PLP.

The above data suggest a causal role of L-CysNO-derived metabolites in the subsequent inhibition of CSE activity. To further investigate this concept, we examined whether L-CysNO could inhibit this activity in the absence of PLP, which is an essential cofactor for CSE. CSE pretreatment with L-CysNO in the absence of PLP failed to inhibit enzyme activity (

Figure 3), indicating that CSE metabolizes L-CysNO and its metabolites inactivate the enzyme.

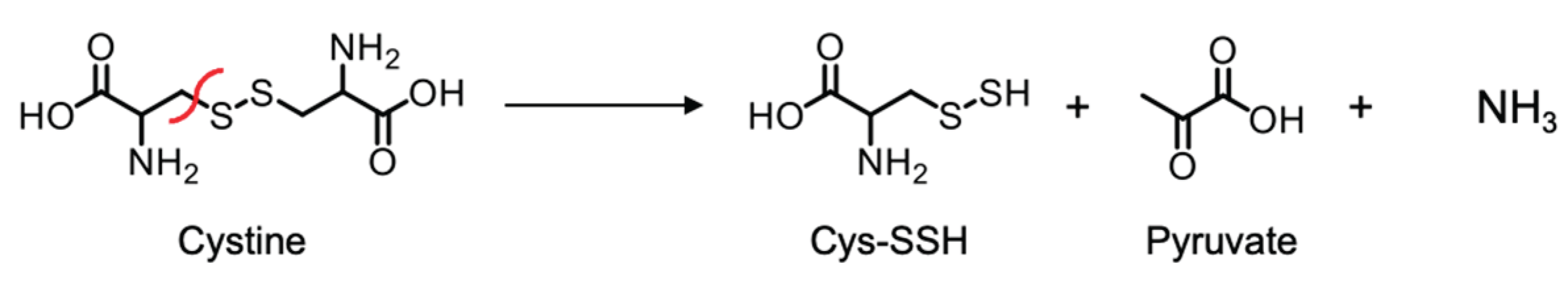

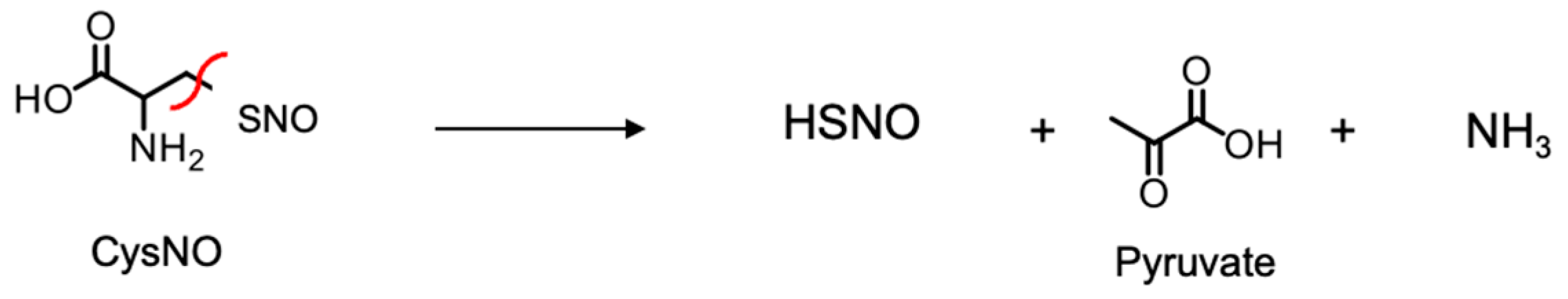

Since CSE shows β-lyase activity toward cystine—an oxidized derivative of Cys—in producing cysteine hydropersulfide and pyruvate (

Scheme 1), it could also exhibit β-lyase activity toward L-CysNO, producing thionitrous acid (HSNO) and pyruvate as the primary products (

Scheme 2).

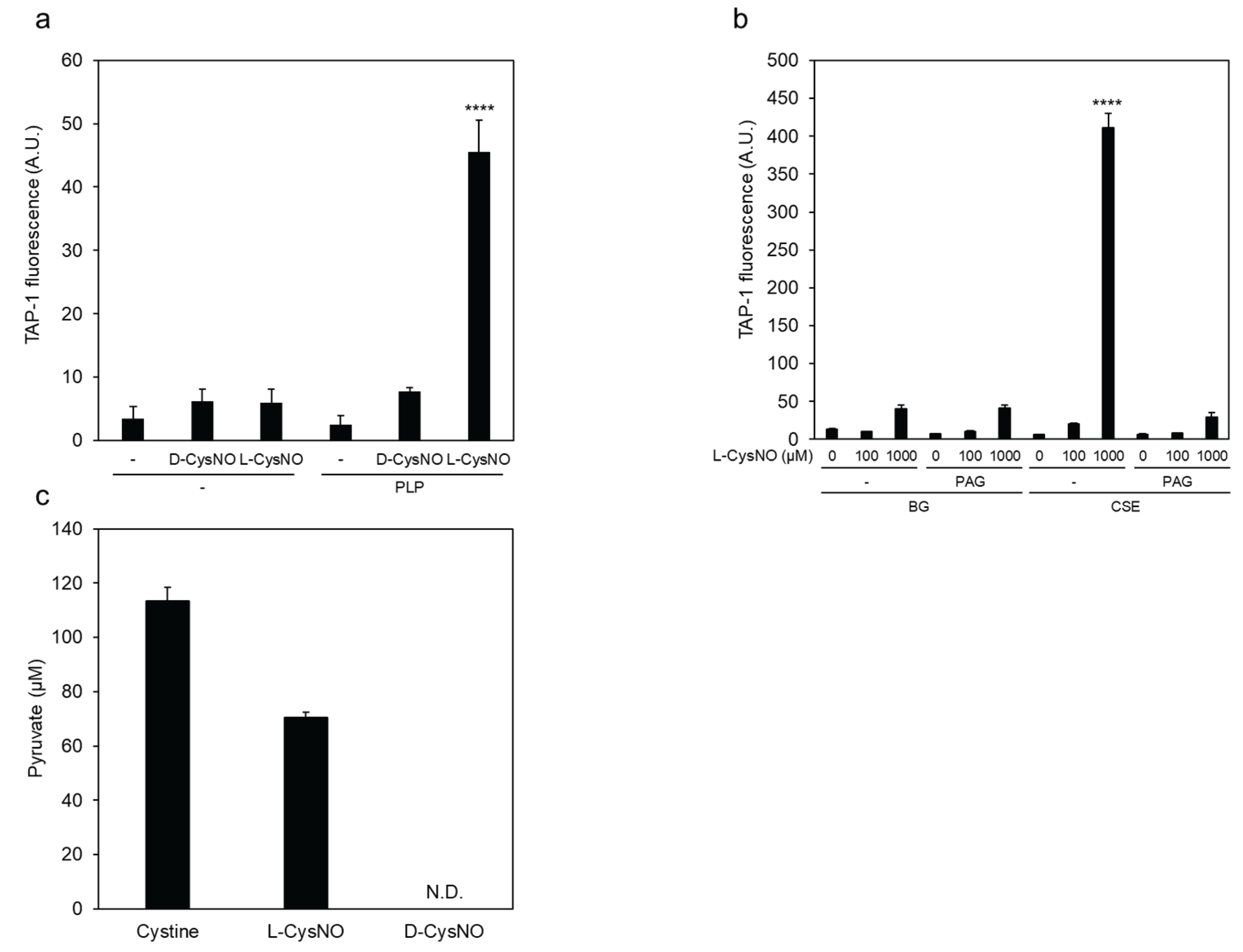

We analyzed CSE/L-CysNO reaction products using the fluorescent probe TAP-1 for HSNO detection [

23]; we also used a fluorescent probe for detecting the hydrogen peroxide produced by pyruvate/pyruvate oxidase in order to quantify pyruvate, following the manufacturer’s instructions. The PLP-dependent β-lyase activity of CSE toward L-CysNO—but not D-CysNO—in producing HSNO was evident, and this was dampened by DL-propargylglycine (PAG) pretreatment, a CSE inhibitor (

Figure 4a and b). Pyruvate production was also observed when CSE was treated with L-CysNO, but not with D-CysNO (

Figure 4c). These results suggest HSNO and pyruvate are the primary products of the CSE/L-CysNO reaction, and these metabolites might be involved in irreversible CSE inhibition.

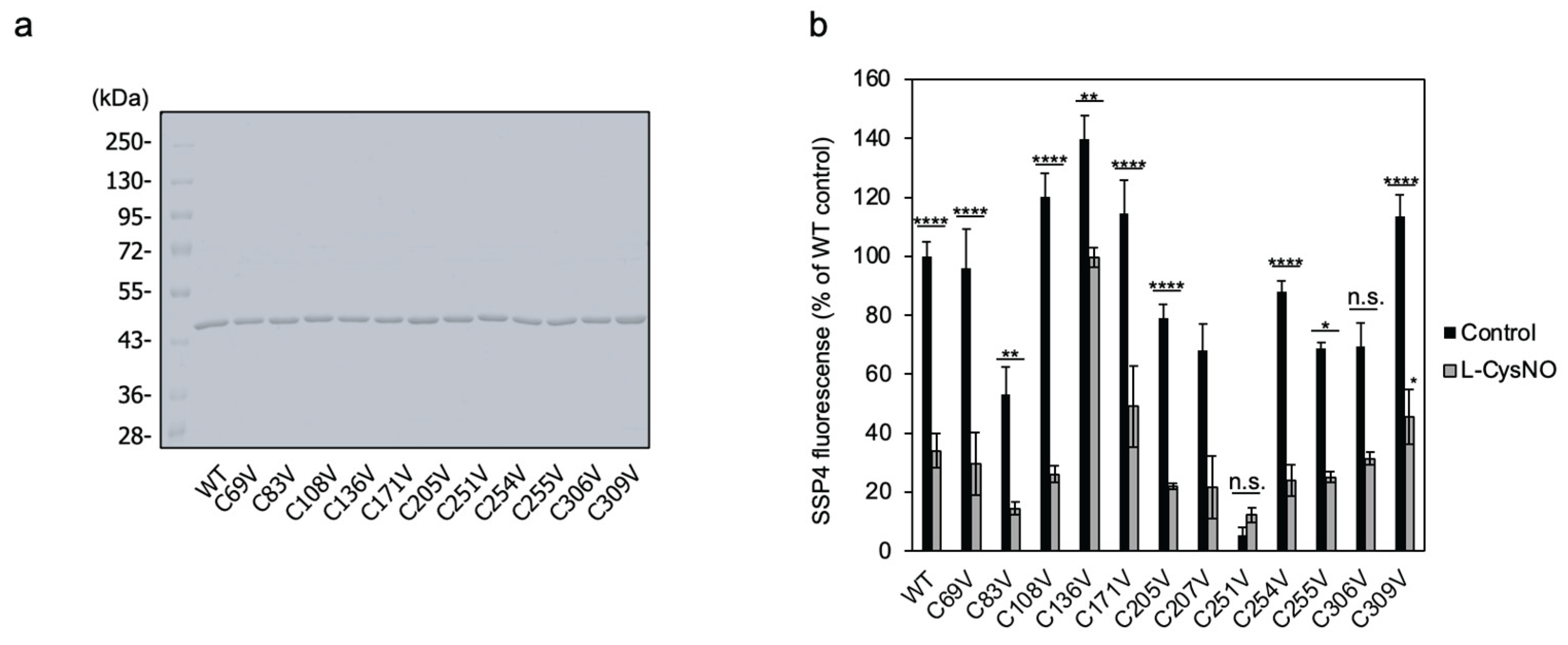

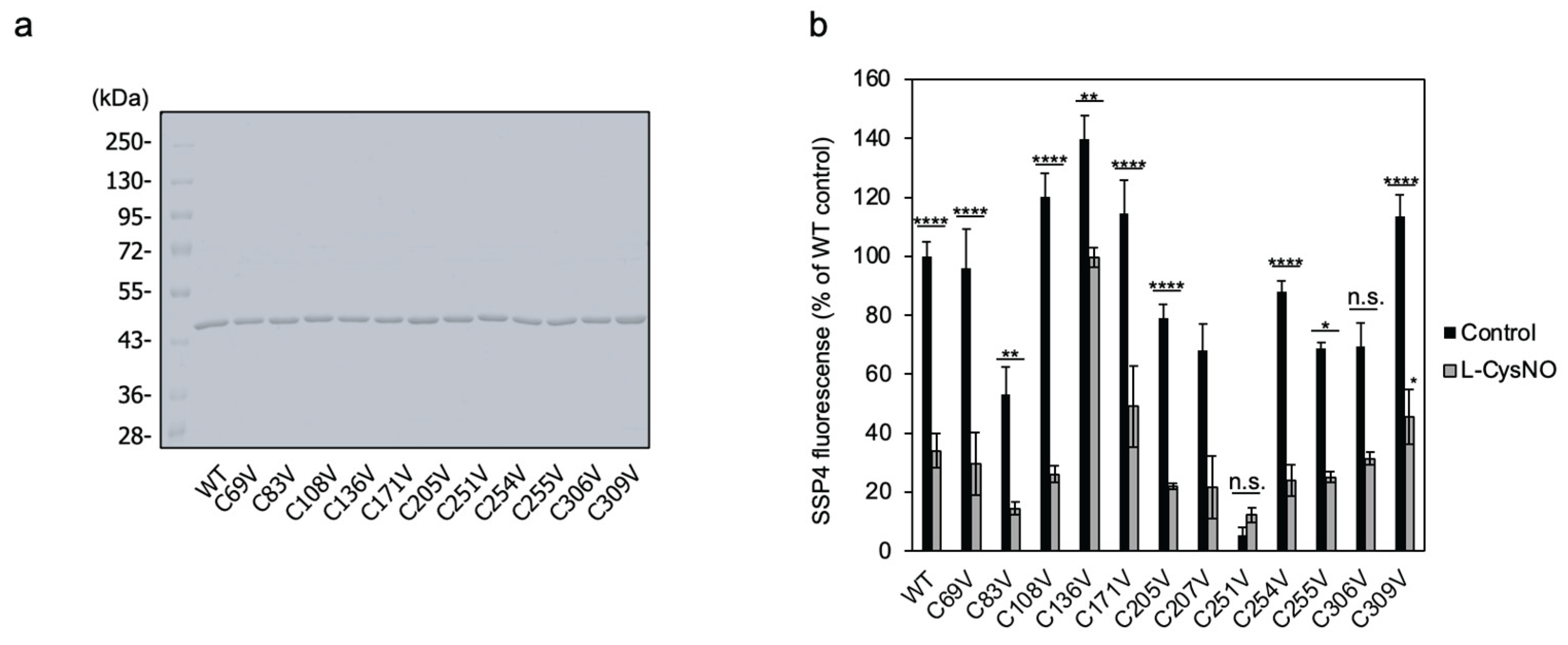

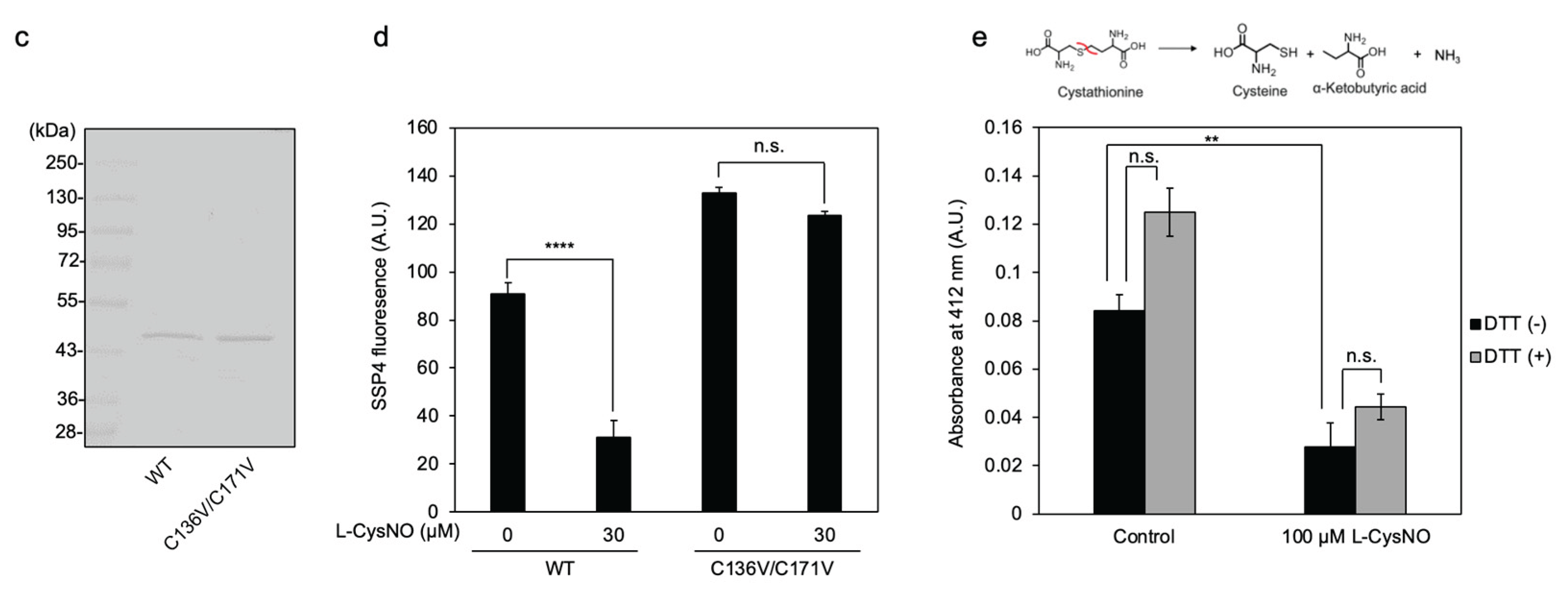

3.3. Cys136 and/or Cys171 Are CSE Sensors of L-CysNO-Induced Enzyme Inhibition

We previously reported that Cys136 is a CSE redox sensor during β-lyase activity toward cystine, generating cysteine hydropersulfide [

19]. In human CSE, the Cys137 residue (corresponding to Cys136 in mice and rats) has been found to play a key role in S-nitrosoglutathione-induced CSE activity inhibition in producing H

2S from cysteine [

18]. Therefore, we tested whether Cys136 is a critical residue for L-CysNO-induced CSE inhibition. The rat liver CSE enzyme comprises twelve cysteine residues. To identify which of these are susceptible to CysNO-induced CSE inactivation, we created rat CSE mutants in which each cysteine was individually substituted with valine. Rat CSE was expressed with a GST tag in pGEX-6P vectors, followed by site-specific GST removal and purification. All purified CSE variants achieved at least 90% purity, displaying a primary band at approximately 45 kDa on SDS-PAGE, visualized with Coomassie Brilliant Blue staining (

Figure 5a). The activity of the wild-type enzyme was suppressed upon exposure to 100 μM L-CysNO. In contrast, the CSE mutant C136V exhibited partial resistance to L-CysNO. Other CSE mutants, including C69V, C83V, C108V, C171V, C205V, C207V, C251V, C254V, C255V, C306V, and C309V, showed no significant changes (

Figure 5b). Studies have indicated that endogenous CSE undergoes S-nitrosylation at Cys171 and Cys136/Cys171 in the kidney and liver of wild-type mice, respectively [

14]. Therefore, a double mutant CSE (C136V/C171V) was expressed and purified using identical pGEX-6P vectors. The recombinant protein achieved a purity level exceeding 90% and appeared as a prominent 45 kDa band on SDS-PAGE following Coomassie Brilliant Blue staining (

Figure 5c). Notably, the C136V/C171V CSE mutant was unaffected by L-CysNO, whereas the wild-type enzyme displayed significant inactivation (

Figure 5d). We employed an in vitro kinase assay to assess whether the CSE γ-lyase activity toward cystathionine when generating cysteine may also be inhibited by L-CysNO. Preincubation with 100 μM L-CysNO resulted in wild-type enzyme inhibition, but not the C136V/C171V CSE mutant (

Figure 5e).

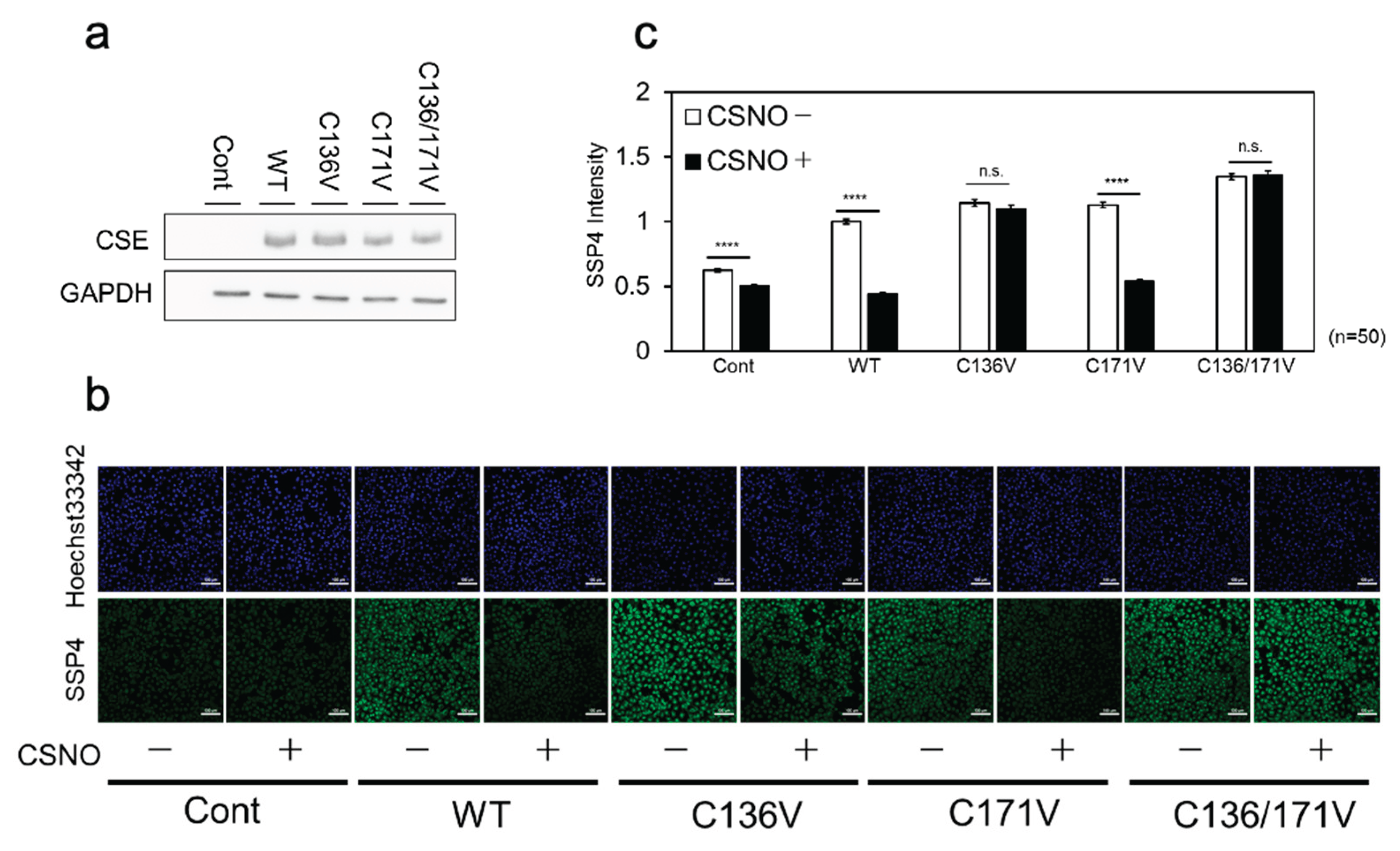

We previously demonstrated that sulfane sulfur levels increased in CSE-overexpressing cells, as detected using the fluorescence probe SSP4 [

19,

25]. For further investigation, we assessed β-lyase activity toward cystine in producing Cys-SSH in COS-7 cells expressing either wild-type CSE or its variants (C136V, C171V, or C136V/C171V). Western blot analysis using an anti-CSE antibody (

Figure 6a) confirmed that all CSE-overexpressing cells exhibited comparable CSE protein levels. A significant increase in SSP4 fluorescence was observed in COS-7 cells expressing wild-type or mutant CSEs compared to those transfected with the empty vector (

Figure 6b, c). Treating cells expressing wild-type or C171V CSE with L-CysNO (100 μM) led to reduced enzyme activity. In contrast, the C136V and C136V/C171V CSE mutants exhibited near-complete resistance to L-CysNO-induced inactivation (

Figure 6B, C). Although the endogenous CSE expression level was negligible compared to that of overexpressed rat CSEs, a detectable SSP4 fluorescence signal was observed in empty vector-transfected cells. This fluorescence was reduced upon L-CysNO treatment, suggesting the lower immunoreactivity of the antibody used in this study toward monkey-derived CSE.

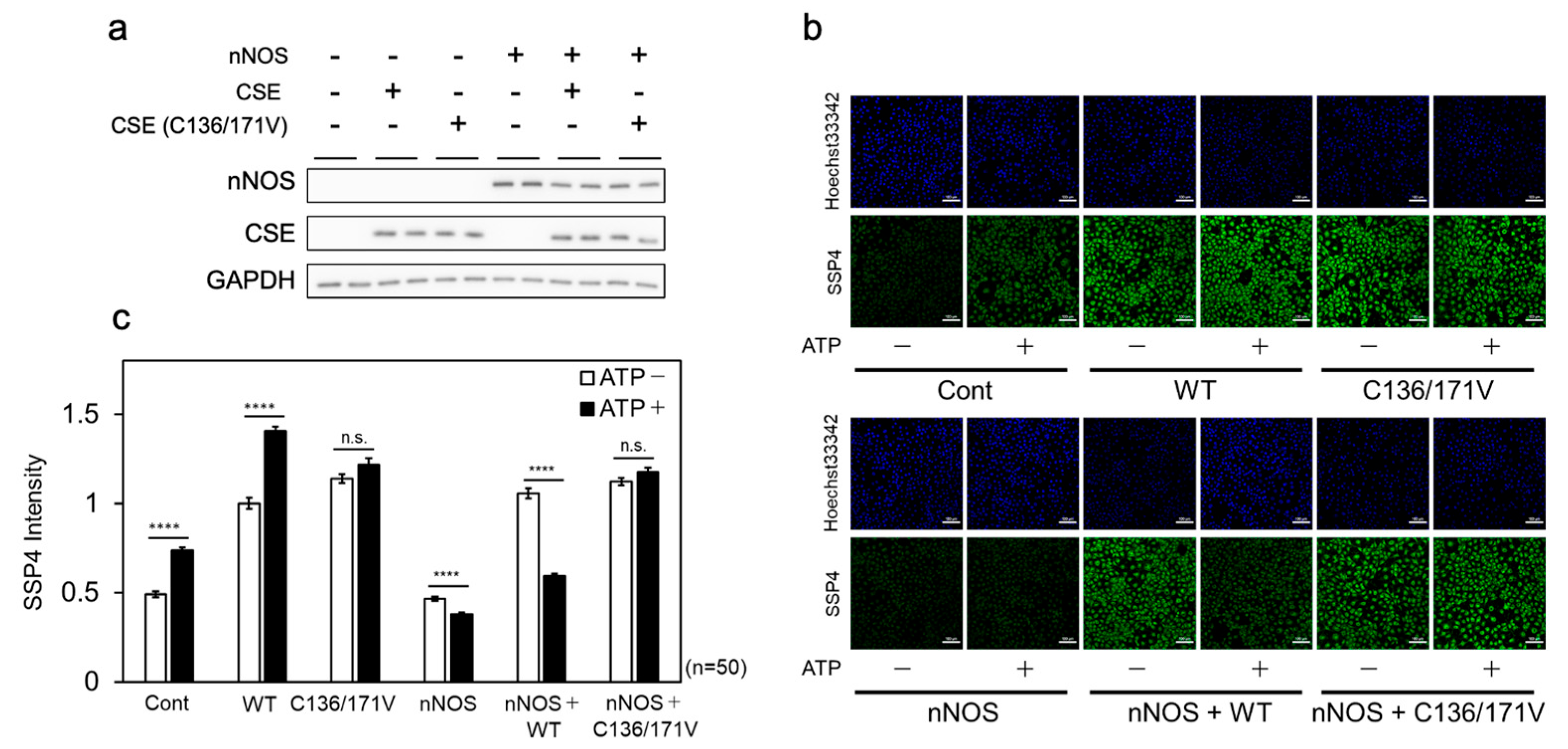

To further examine the effect of NOS-derived NO on cellular CSE β-lyase activity, wild-type or C136V/C171V mutant CSE was co-expressed with nNOS in COS-7 cells. β-lyase activity was then evaluated following ATP stimulation, which elevates intracellular Ca²⁺ levels through P2X purinergic receptor activation. Immunoblot analysis confirmed that nNOS and CSE (wild-type or C136V/C171V) were expressed at comparable levels under all conditions (

Figure 7a). The overexpression of either wild-type or C136V/C171V CSE alone significantly increased SSP4 fluorescence, with ATP stimulation further enhancing fluorescence in wild-type CSE-expressing cells (

Figure 7b, c). When co-expressed with nNOS, wild-type CSE overexpression led to an increase in SSP4 fluorescence, which was subsequently diminished by ATP stimulation. In contrast, C136V/C171V CSE overexpression exhibited a similar increase in SSP4 fluorescence to that of wild-type CSE, but this remained unchanged upon ATP stimulation (

Figure 7 b, c). These findings suggest that NOS-derived NO is converted to L-CysNO, which acts as a substrate for CSE. The resulting metabolites suppress the cysteine hydropersulfide-producing activity of CSE through modifications at Cys136 and/or Cys171 within cells.

4. Discussion

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study to identify L-CysNO as a substrate for CSE. Previous reports have shown that NO donors inhibit the H₂S-producing activity of CSE via S-nitrosylation at Cys136 [

18,

24]. However, our results indicate that NO donors—excluding L-CysNO—do not inhibit cysteine hydropersulfide-producing activity through modification at Cys136 and/or Cys171. This discrepancy is likely due to differences in the experimental substrates used, namely cysteine versus cystine. Since other NO donors can suppress this activity only when co-incubated with L-cysteine (

Figure 1b), it is plausible that their inhibitory effects are primarily mediated through L-CysNO formation. Although protein S-nitrosylation is generally considered to be fully reversible by reducing agents, Fernandes et al. reported that, when L-cysteine is used as a substrate, the GSNO-induced modification of CSE results in only partial inhibition reversal [

18]. In our current study, we found that the L-CysNO-induced inactivation of CSE’s cysteine hydropersulfide-producing activity is not reversed by either thiol-containing or -free reducing agents (

Figure 2). Since L-CysNO can be formed through the reaction between GSNO and L-cysteine, these findings suggest that GSNO-induced CSE modification in the presence of L-cysteine may interfere with CSE activity through a mechanism similar to that involved in the CSE/L-CysNO reaction.

Furthermore, L-CysNO-induced CSE inhibition was evident in the presence of PLP (

Figure 3), suggesting that CSE metabolizes L-CysNO to generate HSNO as an initial product (

Figure 4). This implies that CSE/L-CysNO metabolites contribute to CSE activity suppression. Notably, when immobilized CSE was incubated with the reaction products of CSE and L-CysNO, a significant inhibitory and irreversible effect was observed (data not shown). However, since any residual L-CysNO in the reaction mixture is expected to undergo further metabolism by CSE, we investigated whether its metabolites could also inhibit Ca²⁺/CaM-dependent protein kinase II (CaMKII), a redox-sensitive enzyme regulated via cysteine thiols [

26,

27]. As shown in

Supplementary Figure S1, L-CysNO alone inhibited CaMKII activity, likely via S-nitrosylation, and this inhibition was fully reversed by DTT, consistent with previous findings [

27]. Importantly, its inhibition becomes stronger and irreversible when CSE is co-treated with L-CysNO, indicating that CSE metabolizes L-CysNO and that its metabolites inactivate CaMKII through a novel modification, in addition to S-nitrosylation.

Although the smallest S-nitrosothiol, HSNO, was identified as a primary product of the CSE/L-CysNO reaction, it is expected to exhibit lower stability in solution compared to other RSNO compounds [

28]. To further characterize the reaction products, we utilized SSP-4 for sulfane sulfur detection and the fluorescent probe P-Rhod for HNO detection [

29]. The β-lyase activity of CSE toward L-CysNO, leading to sulfane sulfur generation, was evident; it was suppressed by pretreatment with PAG, a CSE inhibitor (

Supplementary Figure S2a). Additionally, HNO production was detected upon CSE treatment with L-CysNO, but not with D-CysNO (

Supplementary Figure S2b). These findings suggest that sulfane sulfur and HNO, in addition to HSNO, are metabolic products of the CSE/L-CysNO reaction. We previously demonstrated that sulfane sulfur compounds reversibly inhibit CSE's cysteine hydropersulfide-producing activity [

19]. To investigate the potential involvement of HNO in the observed inhibition, we examined the effect of Angeli’s salt, an HNO donor, on CSE activity. Angeli’s salt inhibited this CSE activity, and like the effect of Na

2S

4, this inhibition was reversed in the presence of thiols (

Supplementary Figure S3). Furthermore, when PLP was present in the premix, this inhibition was not obvious, even in the effect of Na

2S

4. These findings suggest that PLP-dependent irreversible CSE inhibition by L-CysNO may not be mediated solely by sulfane sulfur compounds or HNO. To elucidate the specific inhibitory modifications at Cys136 and/or Cys171, we are currently performing a mass spectrometric analysis of synthetic peptides corresponding to CSE 127-145 (FGLKISFVDC136SKTKLLEAA: 2070 Da) and CSE 162-180 (TLKLADIKAC171AQIVHKHKD: 2132 Da) following exposure to CSE/L-CysNO reaction products. Preliminary results indicate the presence of mass spectra peaks at 2131 (2070 + 61) Da and 2161 (2132 + 29) Da, potentially corresponding to CSE127-145-SSNO (SN(S)O, [

30]) and CSE162-180-SNO, respectively (data not shown). Further studies are necessary to confirm these findings.

In summary, our results highlight the critical role of CSE, a pro-longevity gene product [

11], in generating HSNO, which has been proposed as a key intermediate in intracellular sulfur and nitrogen signaling. Although further investigation is required to fully elucidate the mechanism underlying L-CysNO-induced irreversible CSE inhibition at Cys136 and/or Cys171, our findings suggest that CSE metabolizes L-CysNO, leading to enzyme inactivation. This phenomenon may have physiological significance if the irreversible inhibition observed in this study is also present under (patho)physiological conditions.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on Preprints.org.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, S.A., T.T, Y.T. and Y.W.; methodology, S.K, H.I, H.N, and T.A.; validation, Y.T. and Y.W.; formal analysis, S.A. and Y.T; investigation, S.A., S.Y., and Y.T.; resources, T.A.; data curation, S.A. and Y.T.; writing—original draft preparation, S.A. and Y.W.; writing—review and editing, Y.T. and T.A.; visualization, S.A. and Y.T.; supervision, Y.W., S.K., H.I., H.N. and T.A.; project administration, Y.T. and Y.W.; funding acquisition, S.A., S.Y., T.T., T.A., and Y.T. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded in part by Transformative Research Areas, International Leading Re-search, Scientific Research [(S), (B), (C), Challenging Exploratory Research, Early-Career Scien-tists] from the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology (MEXT), Japan, to T. A. (18H05277, 21H05258, 21H05263, 22K19397 23K20040 and 24H00063), Y. T. (21H05262), T. T. (23K06094) and S. A. (24K18280); by Japan Science and Technology Agency, Japan, CREST Grant Number JPMJCR2024, to T. A.; by a grant from the Japan Agency for Medical Research and Development (AMED) to T. A. (JP21zf0127001); and by Grant-in-Aid for Young Scientists of Showa Pharmaceutical University to S.Y.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Acknowledgments

We thank Marie Nakamura, Takumi Matsumoto, Aya Kubota, Aya Hasemi, Hiroto Kenmei, Hayato Nakamura and Kazuya Kuribara for their technical assistance.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

CBS

CSE

CysSSH

D-CysNO

L-CysNO

DTT

GSNO

NO

PAGE

PLP

SSP4 |

cystathionine

β-synthase

cystathionine-γ-lyase

cysteine hydropersulfide

D-S-nitrosocysteine

L-S-nitrosocystein

dithiothreitol

S-nitrosoglutathione

nitric oxide

polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis

pyridoxal 5’-phosphate

sulfane sulfur probe 4 |

References

- Barayeu, U.; Sawa, T.; Nishida, M.; Wei, F. Y.; Motohashi, H.; Akaike, T. , Supersulfide biology and translational medicine for disease control. Br. J. Pharmacol. 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Akaike, T.; Morita, M.; Ogata, S.; Yoshitake, J.; Jung, M.; Sekine, H.; Motohashi, H.; Barayeu, U.; Matsunaga, T. , New aspects of redox signaling mediated by supersulfides in health and disease. Free Radic Biol Med 2024, 222, 539–551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fukuto, J. M.; Ignarro, L. J.; Nagy, P.; Wink, D. A.; Kevil, C. G.; Feelisch, M.; Cortese-Krott, M. M.; Bianco, C. L.; Kumagai, Y.; Hobbs, A. J.; Lin, J.; Ida, T.; Akaike, T. , Biological hydropersulfides and related polysulfides - a new concept and perspective in redox biology. FEBS Lett. 2018, 592, 2140–2152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Akaike, T.; Ida, T.; Wei, F. Y.; Nishida, M.; Kumagai, Y.; Alam, M. M.; Ihara, H.; Sawa, T.; Matsunaga, T.; Kasamatsu, S.; Nishimura, A.; Morita, M.; Tomizawa, K.; Nishimura, A.; Watanabe, S.; Inaba, K.; Shima, H.; Tanuma, N.; Jung, M.; Fujii, S.; Watanabe, Y.; Ohmuraya, M.; Nagy, P.; Feelisch, M.; Fukuto, J. M.; Motohashi, H. , Cysteinyl-tRNA synthetase governs cysteine polysulfidation and mitochondrial bioenergetics. Nat Commun 2017, 8, 1177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ida, T.; Sawa, T.; Ihara, H.; Tsuchiya, Y.; Watanabe, Y.; Kumagai, Y.; Suematsu, M.; Motohashi, H.; Fujii, S.; Matsunaga, T.; Yamamoto, M.; Ono, K.; Devarie-Baez, N. O.; Xian, M.; Fukuto, J. M.; Akaike, T. , Reactive cysteine persulfides and S-polythiolation regulate oxidative stress and redox signaling. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2014, 111, 7606–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kasamatsu, S.; Nishimura, A.; Morita, M.; Matsunaga, T.; Abdul Hamid, H.; Akaike, T. , Redox Signaling Regulated by Cysteine Persulfide and Protein Polysulfidation. Molecules 2016, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nishimura, A.; Yoon, S.; Matsunaga, T.; Ida, T.; Jung, M.; Ogata, S.; Morita, M.; Yoshitake, J.; Unno, Y.; Barayeu, U.; Takata, T.; Takagi, H.; Motohashi, H.; van der Vliet, A.; Akaike, T. , Longevity control by supersulfide-mediated mitochondrial respiration and regulation of protein quality. Redox Biol 2024, 69, 103018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ogata, S.; Matsunaga, T.; Jung, M.; Barayeu, U.; Morita, M.; Akaike, T. , Persulfide Biosynthesis Conserved Evolutionarily in All Organisms. Antioxid. Redox Signal. 2023, 39, 983–999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petrovic, D.; Slade, L.; Paikopoulos, Y.; D'Andrea, D.; Savic, N.; Stancic, A.; Miljkovic, J. L.; Vignane, T.; Drekolia, M. K.; Mladenovic, D.; Sutulovic, N.; Refeyton, A.; Kolakovic, M.; Jovanovic, V. M.; Zivanovic, J.; Miler, M.; Vellecco, V.; Brancaleone, V.; Bucci, M.; Casey, A. M.; Yu, C.; Kasarla, S. S.; Smith, K. W.; Kalfe-Yildiz, A.; Stenzel, M.; Miranda-Vizuete, A.; Hergenröder, R.; Phapale, P.; Stanojlovic, O.; Ivanovic-Burmazovic, I.; Vlaski-Lafarge, M.; Bibli, S. I.; Murphy, M. P.; Otasevic, V.; Filipovic, M. R. , Ergothioneine improves healthspan of aged animals by enhancing cGPDH activity through CSE-dependent persulfidation. Cell Metab 2025, 37, 542–556.e14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hine, C.; Harputlugil, E.; Zhang, Y.; Ruckenstuhl, C.; Lee, B. C.; Brace, L.; Longchamp, A.; Treviño-Villarreal, J. H.; Mejia, P.; Ozaki, C. K.; Wang, R.; Gladyshev, V. N.; Madeo, F.; Mair, W. B.; Mitchell, J. R. , Endogenous hydrogen sulfide production is essential for dietary restriction benefits. Cell 2015, 160, 132–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tyshkovskiy, A.; Bozaykut, P.; Borodinova, A. A.; Gerashchenko, M. V.; Ables, G. P.; Garratt, M.; Khaitovich, P.; Clish, C. B.; Miller, R. A.; Gladyshev, V. N. , Identification and Application of Gene Expression Signatures Associated with Lifespan Extension. Cell Metab 2019, 30, 573–593.e8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alam, S.; Pardue, S.; Shen, X.; Glawe, J. D.; Yagi, T.; Bhuiyan, M. A. N.; Patel, R. P.; Dominic, P. S.; Virk, C. S.; Bhuiyan, M. S.; Orr, A. W.; Petit, C.; Kolluru, G. K.; Kevil, C. G. , Hypoxia increases persulfide and polysulfide formation by AMP kinase dependent cystathionine gamma lyase phosphorylation. Redox Biol 2023, 68, 102949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yuan, G.; Vasavda, C.; Peng, Y. J.; Makarenko, V. V.; Raghuraman, G.; Nanduri, J.; Gadalla, M. M.; Semenza, G. L.; Kumar, G. K.; Snyder, S. H.; Prabhakar, N. R. , Protein kinase G-regulated production of H2S governs oxygen sensing. Sci Signal 2015, 8, ra37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Doulias, P. T.; Tenopoulou, M.; Greene, J. L.; Raju, K.; Ischiropoulos, H. , Nitric oxide regulates mitochondrial fatty acid metabolism through reversible protein S-nitrosylation. Sci Signal 2013, 6, rs1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Jia, G.; Li, H.; Yan, S.; Qian, J.; Guo, X.; Li, G.; Qi, H.; Zhu, Z.; Wu, Y.; He, W.; Niu, W. , H(2)O(2)-Mediated Oxidative Stress Enhances Cystathionine γ-Lyase-Derived H(2)S Synthesis via a Sulfenic Acid Intermediate. Antioxidants (Basel) 2021, 10. [Google Scholar]

- Luo, C.; Ji, D.; Li, Y.; Cao, Y.; Zhang, S.; Yan, W.; Xue, K.; Chai, J.; Wu, Y.; Liu, H.; Wang, W. , Abnormal nitration and S-sulfhydration modification of Sp1-CSE-H(2)S pathway trap the progress of hyperhomocysteinemia into a vicious cycle. Free Radic Biol Med 2021, 164, 20–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mustafa, A. K.; Gadalla, M. M.; Sen, N.; Kim, S.; Mu, W.; Gazi, S. K.; Barrow, R. K.; Yang, G.; Wang, R.; Snyder, S. H. , H2S signals through protein S-sulfhydration. Sci Signal 2009, 2, ra72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernandes, D. G. F.; Nunes, J.; Tomé, C. S.; Zuhra, K.; Costa, J. M. F.; Antunes, A. M. M.; Giuffrè, A.; Vicente, J. B. , Human Cystathionine γ-Lyase Is Inhibited by s-Nitrosation: A New Crosstalk Mechanism between NO and H(2)S. Antioxidants (Basel) 2021, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Araki, S.; Takata, T.; Ono, K.; Sawa, T.; Kasamatsu, S.; Ihara, H.; Kumagai, Y.; Akaike, T.; Watanabe, Y.; Tsuchiya, Y. , Cystathionine γ-Lyase Self-Inactivates by Polysulfidation during Cystine Metabolism. Int J Mol Sci 2023, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zainol Abidin, Q. H.; Ida, T.; Morita, M.; Matsunaga, T.; Nishimura, A.; Jung, M.; Hassan, N.; Takata, T.; Ishii, I.; Kruger, W.; Wang, R.; Motohashi, H.; Tsutsui, M.; Akaike, T. , Synthesis of Sulfides and Persulfides Is Not Impeded by Disruption of Three Canonical Enzymes in Sulfur Metabolism. Antioxidants (Basel) 2023, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nishi, N.; Tanabe, H.; Oya, H.; Urushihara, M.; Miyanaka, H.; Wada, F. , Identification of probasin-related antigen as cystathionine gamma-lyase by molecular cloning. J. Biol. Chem. 1994, 269, 1015–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shinkai, Y.; Masuda, A.; Akiyama, M.; Xian, M.; Kumagai, Y. , Cadmium-Mediated Activation of the HSP90/HSF1 Pathway Regulated by Reactive Persulfides/Polysulfides. Toxicol. Sci. 2017, 156, 412–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, W.; Matsunaga, T.; Neill, D. L.; Yang, C. T.; Akaike, T.; Xian, M. , Rational Design of a Dual-Reactivity-Based Fluorescent Probe for Visualizing Intracellular HSNO. Angew Chem Int Ed Engl 2019, 58, 16067–16070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Asimakopoulou, A.; Panopoulos, P.; Chasapis, C. T.; Coletta, C.; Zhou, Z.; Cirino, G.; Giannis, A.; Szabo, C.; Spyroulias, G. A.; Papapetropoulos, A. , Selectivity of commonly used pharmacological inhibitors for cystathionine β synthase (CBS) and cystathionine γ lyase (CSE). Br. J. Pharmacol. 2013, 169, 922–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shieh, M.; Ni, X.; Xu, S.; Lindahl, S. P.; Yang, M.; Matsunaga, T.; Flaumenhaft, R.; Akaike, T.; Xian, M. , Shining a light on SSP4: A comprehensive analysis and biological applications for the detection of sulfane sulfurs. Redox Biol 2022, 56, 102433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Araki, S.; Takata, T.; Tsuchiya, Y.; Watanabe, Y. , Reactive sulfur species impair Ca(2+)/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase II via polysulfidation. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2019, 508, 550–555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, T.; Hatano, N.; Kambe, T.; Miyamoto, Y.; Ihara, H.; Yamamoto, H.; Sugimoto, K.; Kume, K.; Yamaguchi, F.; Tokuda, M.; Watanabe, Y. , Nitric oxide-mediated modulation of calcium/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase II. Biochem. J. 2008, 412, 223–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nava, M.; Martin-Drumel, M. A.; Lopez, C. A.; Crabtree, K. N.; Womack, C. C.; Nguyen, T. L.; Thorwirth, S.; Cummins, C. C.; Stanton, J. F.; McCarthy, M. C. , Spontaneous and Selective Formation of HSNO, a Crucial Intermediate Linking H2S and Nitroso Chemistries. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2016, 138, 11441–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kawai, K.; Ieda, N.; Aizawa, K.; Suzuki, T.; Miyata, N.; Nakagawa, H. , A reductant-resistant and metal-free fluorescent probe for nitroxyl applicable to living cells. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2013, 135, 12690–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wedmann, R.; Zahl, A.; Shubina, T. E.; Dürr, M.; Heinemann, F. W.; Bugenhagen, B. E. C.; Burger, P.; Ivanovic-Burmazovic, I.; Filipovic, M. R. , Does Perthionitrite (SSNO–) Account for Sustained Bioactivity of NO? A (Bio)chemical Characterization. Inorg. Chem. 2015, 54, 9367–9380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Figure 1.

Effect of NO donors on CSE activity. (a) Concentration-dependent inhibition of CSE activity by incubation with L-CysNO. Purified CSE (50 μg/mL) was incubated at 30 °C for 30 min with varying concentrations of NO donor compounds in a buffer containing 50 mM Hepes/NaOH (pH 7.5) and 50 μM PLP. Enzyme activity was subsequently measured by adding 1 mM cystine, and the resulting Cys-SSH levels were quantified using the SSP4 probe. (b)(c) Effect of cysteine on NO donor-mediated modulation of CSE activity. Purified CSE (50 μg/mL) was incubated at 30 °C for 30 min with 10 μM NO donor compounds in the same buffer, in the presence or absence of 10 μM cysteine. Results are the mean ± SE of four independent experiments. **** p < 0.0001, *** p < 0.001, ** p < 0.01, and * p < 0.05, unless otherwise indicated in the figure, compared with the controls of each sample. n.s.: not significant.

Figure 1.

Effect of NO donors on CSE activity. (a) Concentration-dependent inhibition of CSE activity by incubation with L-CysNO. Purified CSE (50 μg/mL) was incubated at 30 °C for 30 min with varying concentrations of NO donor compounds in a buffer containing 50 mM Hepes/NaOH (pH 7.5) and 50 μM PLP. Enzyme activity was subsequently measured by adding 1 mM cystine, and the resulting Cys-SSH levels were quantified using the SSP4 probe. (b)(c) Effect of cysteine on NO donor-mediated modulation of CSE activity. Purified CSE (50 μg/mL) was incubated at 30 °C for 30 min with 10 μM NO donor compounds in the same buffer, in the presence or absence of 10 μM cysteine. Results are the mean ± SE of four independent experiments. **** p < 0.0001, *** p < 0.001, ** p < 0.01, and * p < 0.05, unless otherwise indicated in the figure, compared with the controls of each sample. n.s.: not significant.

Figure 2.

Effect of DTT and TCEP on the reversibility of CSE inhibition by either L-CysNO or Na2S4. Immobilized GST-CSE was preincubated with either 100 μM L-CysNO (a, b) or 10 μM Na2S4 (b) in the presence of 50 µM PLP at 30 °C for 10 min. After centrifugation to remove residual L-CysNO or Na2S4, CSE activity was assessed in a reaction mixture containing 50 μM PLP and 1 mM cystine. The production of CysSSH was then detected using the SSP4 fluorescent probe. For the DTT (a, b) and TCEP (a) conditions, samples were additionally incubated with 10 mM DTT and 10 mM TCEP at 30 °C for 10 min, followed by centrifugation prior to assessment. Results are the mean ± SE of four independent experiments. **** p < 0.0001, ** p < 0.01, and * p < 0.05, unless otherwise indicated in the figure, compared with the controls of each sample. n.s.: not significant.

Figure 2.

Effect of DTT and TCEP on the reversibility of CSE inhibition by either L-CysNO or Na2S4. Immobilized GST-CSE was preincubated with either 100 μM L-CysNO (a, b) or 10 μM Na2S4 (b) in the presence of 50 µM PLP at 30 °C for 10 min. After centrifugation to remove residual L-CysNO or Na2S4, CSE activity was assessed in a reaction mixture containing 50 μM PLP and 1 mM cystine. The production of CysSSH was then detected using the SSP4 fluorescent probe. For the DTT (a, b) and TCEP (a) conditions, samples were additionally incubated with 10 mM DTT and 10 mM TCEP at 30 °C for 10 min, followed by centrifugation prior to assessment. Results are the mean ± SE of four independent experiments. **** p < 0.0001, ** p < 0.01, and * p < 0.05, unless otherwise indicated in the figure, compared with the controls of each sample. n.s.: not significant.

Figure 3.

Effect of PLP on L-CysNO-induced inhibition of CSE activity. Immobilized GST-CSE was preincubated with 10 μM D- or L-CysNO at 30 °C for 10 min, either without (a) or with (b) 50 μM PLP. The enzymatic activity of CSE in each reaction mixture was then measured in the presence of 50 μM PLP and 1 mM cystine, following the procedure described in

Figure 2. Results are the mean ± SE of four independent experiments. **** p < 0.0001, unless otherwise indicated in the figure, compared with the controls of each sample. n.s.: not significant.

Figure 3.

Effect of PLP on L-CysNO-induced inhibition of CSE activity. Immobilized GST-CSE was preincubated with 10 μM D- or L-CysNO at 30 °C for 10 min, either without (a) or with (b) 50 μM PLP. The enzymatic activity of CSE in each reaction mixture was then measured in the presence of 50 μM PLP and 1 mM cystine, following the procedure described in

Figure 2. Results are the mean ± SE of four independent experiments. **** p < 0.0001, unless otherwise indicated in the figure, compared with the controls of each sample. n.s.: not significant.

Scheme 1.

CSE β-lyase activity toward cystine in generating Cys-SSH.

Scheme 1.

CSE β-lyase activity toward cystine in generating Cys-SSH.

Scheme 2.

CSE β-lyase activity toward L-CysNO in generating HSNO.

Scheme 2.

CSE β-lyase activity toward L-CysNO in generating HSNO.

Figure 4.

Product analysis of CSE with L-CysNO. (a, b) HSNO production. Purified CSE (50 μg/mL) was incubated at 30 °C for 30 min with 100 μM D- or L-CysNO, either without or with 50 μM PLP (a), or with the indicated concentrations of L-CysNO and 50 μM PLP, in the absence or presence of 1mM PAG (b), in a buffer containing 50 mM Hepes/NaOH (pH 7.5) and 50 μM PLP. HSNO levels were quantified using the TAP-1 probe. (c) Pyruvate production. Purified CSE (50 μg/mL) was incubated at 30 °C for 30 min with 1 mM cystine or D- or L-CysNO in the presence of 50 μM PLP in the same buffer. Pyruvate production was measured using a fluorescent probe specific for hydrogen peroxide. Results are the mean ± SE of four independent experiments. **** p < 0.0001 when compared with the controls of each sample.

Figure 4.

Product analysis of CSE with L-CysNO. (a, b) HSNO production. Purified CSE (50 μg/mL) was incubated at 30 °C for 30 min with 100 μM D- or L-CysNO, either without or with 50 μM PLP (a), or with the indicated concentrations of L-CysNO and 50 μM PLP, in the absence or presence of 1mM PAG (b), in a buffer containing 50 mM Hepes/NaOH (pH 7.5) and 50 μM PLP. HSNO levels were quantified using the TAP-1 probe. (c) Pyruvate production. Purified CSE (50 μg/mL) was incubated at 30 °C for 30 min with 1 mM cystine or D- or L-CysNO in the presence of 50 μM PLP in the same buffer. Pyruvate production was measured using a fluorescent probe specific for hydrogen peroxide. Results are the mean ± SE of four independent experiments. **** p < 0.0001 when compared with the controls of each sample.

Figure 5.

Cysteine residues involved in L-CysNO-induced CSE activity inhibition. (a) Preparation of purified recombinant CSEs used in this study. Equal amounts (1 μg) of GST-cleaved wild-type CSE (WT) and the indicated mutants expressed in E. coli were separated by 10% SDS-PAGE and stained with Coomassie Brilliant Blue. (b) Purified wild-type CSE and the indicated cysteine-to-valine mutants (50 μg/mL) were incubated at 30 °C for 30 min either in the absence or presence of 100 μM L-CysNO and 50 μM PLP. Enzyme activity was assessed by adding 1 mM cystine, following the protocol described in

Figure 1A. (c) Equal amounts (0.5 μg) of purified WT and the C136V/C171V double mutant expressed in E. coli were analyzed by 10% SDS-PAGE and stained with Coomassie Brilliant Blue. (d) Purified WT and the indicated CSE mutants (50 μg/mL) were incubated at 30 °C for 30 min with or without 30 μM L-CysNO and 50 μM PLP. Enzyme activity was then evaluated by introducing 1 mM cystine, as described in

Figure 1A. (e) Effect of the C136V/C171V mutation on the γ-lyase activity of CSE toward cystathionine in generating cysteine (see inset). WT or C136V/C171V mutant CSE was incubated with 50 μM PLP, 1 mM DTNB, and 1 mM cystathionine at 30 °C for 10 min, followed by absorbance measurement at 412 nm, as described in the Materials and Methods section. Results are the mean ± SE of four independent experiments. **** p < 0.0001, ** p < 0.01, and * p < 0.05, unless otherwise indicated in the figure, compared with the controls of each sample. n.s.: not significant.

Figure 5.

Cysteine residues involved in L-CysNO-induced CSE activity inhibition. (a) Preparation of purified recombinant CSEs used in this study. Equal amounts (1 μg) of GST-cleaved wild-type CSE (WT) and the indicated mutants expressed in E. coli were separated by 10% SDS-PAGE and stained with Coomassie Brilliant Blue. (b) Purified wild-type CSE and the indicated cysteine-to-valine mutants (50 μg/mL) were incubated at 30 °C for 30 min either in the absence or presence of 100 μM L-CysNO and 50 μM PLP. Enzyme activity was assessed by adding 1 mM cystine, following the protocol described in

Figure 1A. (c) Equal amounts (0.5 μg) of purified WT and the C136V/C171V double mutant expressed in E. coli were analyzed by 10% SDS-PAGE and stained with Coomassie Brilliant Blue. (d) Purified WT and the indicated CSE mutants (50 μg/mL) were incubated at 30 °C for 30 min with or without 30 μM L-CysNO and 50 μM PLP. Enzyme activity was then evaluated by introducing 1 mM cystine, as described in

Figure 1A. (e) Effect of the C136V/C171V mutation on the γ-lyase activity of CSE toward cystathionine in generating cysteine (see inset). WT or C136V/C171V mutant CSE was incubated with 50 μM PLP, 1 mM DTNB, and 1 mM cystathionine at 30 °C for 10 min, followed by absorbance measurement at 412 nm, as described in the Materials and Methods section. Results are the mean ± SE of four independent experiments. **** p < 0.0001, ** p < 0.01, and * p < 0.05, unless otherwise indicated in the figure, compared with the controls of each sample. n.s.: not significant.

Figure 6.

CSE β-lyase activity toward cystine in cells. (a) COS-7 cells were transfected with wild-type (WT) CSE cDNA, the indicated CSE mutant cDNAs, or an empty vector (Cont), and subjected to Western blot analysis using anti-CSE and anti-GAPDH antibodies. (b) Live-cell fluorescence imaging of Cys-SSH production was performed using SSP4 in COS-7 cells transfected with either WT CSE or the indicated mutants. (c) Relative Cys-SSH levels were quantified based on SSP4 fluorescence intensity in each sample shown in panel (b). Data are presented as mean ± SE. ****p < 0.0001 vs. control, as indicated; n.s., not significant.

Figure 6.

CSE β-lyase activity toward cystine in cells. (a) COS-7 cells were transfected with wild-type (WT) CSE cDNA, the indicated CSE mutant cDNAs, or an empty vector (Cont), and subjected to Western blot analysis using anti-CSE and anti-GAPDH antibodies. (b) Live-cell fluorescence imaging of Cys-SSH production was performed using SSP4 in COS-7 cells transfected with either WT CSE or the indicated mutants. (c) Relative Cys-SSH levels were quantified based on SSP4 fluorescence intensity in each sample shown in panel (b). Data are presented as mean ± SE. ****p < 0.0001 vs. control, as indicated; n.s., not significant.

Figure 7.

Effect of ATP-induced NOS activation on CSE β-lyase activity in cells. (a) Wild-type (CSE) or mutant (C136V/C171V) CSE cDNA was co-transfected into COS-7 cells along with either an empty vector (nNOS−) or nNOS cDNA (nNOS+), followed by Western blot analysis using anti-CSE and anti-nNOS antibodies. (b) Live-cell fluorescence imaging of Cys-SSH production was performed using SSP4 in COS-7 cells co-transfected with the indicated combinations of cDNAs, with or without ATP stimulation. (c) Relative Cys-SSH levels were quantified based on SSP4 fluorescence intensity in each sample shown in panel (b). Data are presented as mean ± SE. ****p < 0.0001 vs. control, as indicated; n.s., not significant.

Figure 7.

Effect of ATP-induced NOS activation on CSE β-lyase activity in cells. (a) Wild-type (CSE) or mutant (C136V/C171V) CSE cDNA was co-transfected into COS-7 cells along with either an empty vector (nNOS−) or nNOS cDNA (nNOS+), followed by Western blot analysis using anti-CSE and anti-nNOS antibodies. (b) Live-cell fluorescence imaging of Cys-SSH production was performed using SSP4 in COS-7 cells co-transfected with the indicated combinations of cDNAs, with or without ATP stimulation. (c) Relative Cys-SSH levels were quantified based on SSP4 fluorescence intensity in each sample shown in panel (b). Data are presented as mean ± SE. ****p < 0.0001 vs. control, as indicated; n.s., not significant.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).