1. Introduction

System x

c- is a membrane transporter that plays a central role in the cellular antioxidant response [

1,

2], including protection from ferroptosis, an iron-dependent, non-apoptotic mechanism of cell death associated with numerous disease pathways [

3]. This membrane transporter exchanges intracellular glutamate for extracellular cystine, and the internalized cystine is rapidly reduced to cysteine which is required for the synthesis of the endogenous antioxidant glutathione. Given that cysteine is the rate limiting reagent for glutathione synthesis, the proper regulation of System x

c- is essential for the maintenance of glutathione levels and prevention of oxidative stress and ferroptosis [

3].

Recently, System x

c- has been shown to be acutely regulated by oxidant exposure [

1]. Within 10 min of exposure to physiologically relevant levels of hydrogen peroxide, System x

c- traffics to the plasma membrane, resulting in a doubling of transporter activity, recovery of cellular glutathione levels, and reestablishment of oxidative balance within the cell [

1]. Specifically, hydrogen peroxide appears to increase the transporter delivery rate to and decrease the internalization rate from the membrane, resulting in an overall increase in cell surface localization. But the mechanism by which hydrogen peroxide influences the trafficking of the transporter is not yet understood.

Examples of dynamic regulation of the trafficking of membrane proteins to and from the cell surface are as numerous as the signals that appear to regulate them [

4,

5,

6,

7,

8,

9,

10]. For example, G-protein coupled receptors exhibit downregulation after prolonged exposure to agonists which triggers an increase in receptor internalization [

11], and the epithelial sodium channel is activated by aldosterone [

12], leading to a reduction in the rate of internalization of the channel from the plasma membrane. In nearly all cases, these changes in trafficking result from signal-induced changes in post-translational modification (PTM) of trafficking motifs within the N- or C-terminus of the membrane protein. Ultimately, the shift in PTM status of the protein alters its interaction with trafficking proteins within the cell, directly impacting protein delivery and/or internalization rates.

While there have been numerous studies that have detailed the transcription factors that regulate the expression of System x

c- [

13,

14,

15,

16,

17,

18], there have been surprisingly few which examine the acute, reversible regulation and trafficking of this transporter. System x

c- belongs to the family of heterodimeric amino acid transport (HAAT) proteins (SLC7 gene family) that includes nine different members with unique amino acid substrate specificities (for review see [

19,

20,

21]). Like most members of the HAAT family, System x

c- is composed of two proteins, a 50 kD light chain protein xCT (SLC7A11) that is linked through a disulfide bond to a 98 kD type II glycosylated heavy chain protein 4F2HC (SLC3A2) [

22,

23]. Each member of the HAAT family has a unique light chain which confers substrate specificity, while the role of the heavy chain is not well understood [

24,

25,

26,

27].

Studies focused on identifying PTMs of xCT and 4F2HC are lacking, and to date, no definitive trafficking motifs within xCT have been identified. Serine 26 of xCT is phosphorylated by mammalian target of rapamycin 2 (mTORC2), leading to inhibition of transporter activity perhaps through changes in membrane localization [

28]. Very recently, xCT was reported to be palmitoylated at cysteine 327 which appears to increase the stability of the protein, perhaps by reducing its ubiquitination [

29]. Lastly, five phosphorylation sites were identified in the extracellular domain of 4F2HC, but these motifs appear to regulate cell-cell interactions [

30]. Thus, our understanding of the role PTMs play in the regulation of System x

c- is poor relative to other families of membrane proteins.

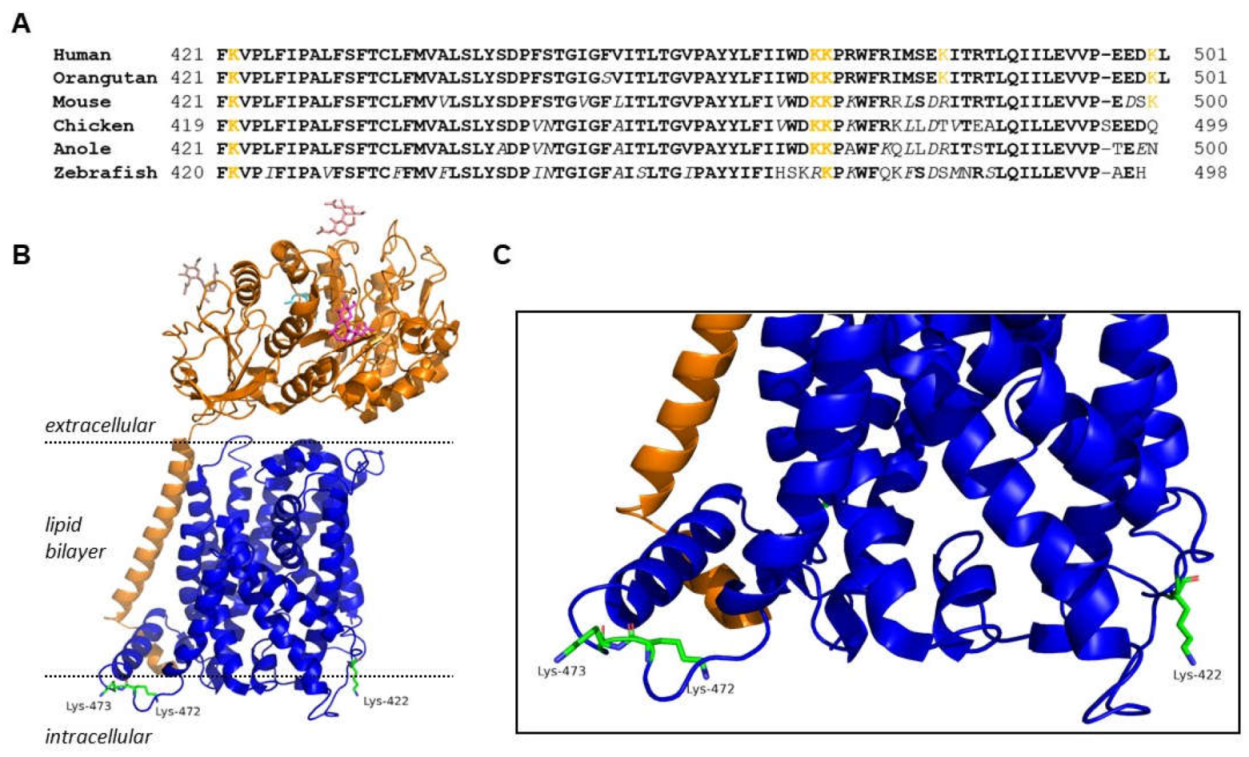

Therefore, the primary objective of this study was to use site-directed mutagenesis to identify trafficking motifs within xCT so that we can better understand its regulation. Since many trafficking motifs are typically found within the internal N- or C-terminus of proteins, we chose to focus on the C-terminus of xCT, given that it is more highly conserved across species relative to the N-terminus (Fig 1). We reasoned that the high degree of conservation increased our likelihood of identifying trafficking motifs. In addition, we chose to focus on lysine residues exclusively in this study. Lysine residues are common sites of PTM which are known to impact protein trafficking, including ubiquitination, neddylation, SUMOylation, and acetylation [

31,

32,

33,

34,

35]. xCT has numerous conserved lysine residues, and the C-terminus has three conserved lysine sites (K422, K472, and K473) that are positioned on the intracellular surface of xCT when located on the plasma membrane, suggesting they would allow for potential interaction with trafficking proteins within the intracellular compartment (

Figure 1). Therefore, in this study we sought to determine how site-directed mutagenesis of these C-terminal lysine residues affected the trafficking and activity of System x

c-. This work has led to the identification of a lysine residue, K473, that appears to regulate trafficking of xCT through the ER and Golgi, and ultimately, its maturation into a functional transporter.

3. Discussion

In this study we have identified a novel mechanism for the regulation of xCT trafficking through the secretory pathway and have identified K473 as a critical residue involved in this regulatory process. Specifically, we demonstrated that mutation of lysine 473 to arginine, an amino acid of similar size and charge which cannot be post-translationally modified, eliminates System x

c- activity as a result of diminished trafficking of xCT to the plasma membrane. Instead, this transporter is sequestered nearly completely within the ER. Interestingly, we discovered that this mutation also results in a 7.5 kD loss in the apparent molecular weight of xCT. While we originally postulated that this was a result of loss of ubiquitination or neddylation at K473, our results instead indicate that the K473R mutant lacks both N-and O-glycosylation, accounting for some, but not all, of the loss in molecular weight relative to WT. Since lysine is not a substrate for glycosylation, these results suggest that PTM of K473 may regulate the glycosylation of the transporter and its progression through the ER and ultimately prevent xCT from acquiring additionals PTMs. Such PTM crosstalk, in which PTMs on different residues within the same protein influence each other, is a common way to meticulously regulate a protein’s activity, localization, and stability[

46,

47,

48].

An example of such PTM crosstalk, ER acetylation is a relatively recent discovery that has been found to play a crucial role in the processing of proteins in the ER that follow the secretory pathway through the Golgi and ultimately become localized to the plasma membrane [

34]. In particular, ER lysine acetylation of some glycoproteins is essential for export of these proteins from the ER, proper N-glycan maturation in the Golgi, and subsequent post-Golgi trafficking [

49]. For example β-site APP cleaving enzyme 1 (BACE-1) and Prominin1 (CD133) undergo lysine acetylation in the ER lumen, a process which is necessary for their exit from the ER [

44,

50]. Subsequently, both proteins are deacetylated in the Golgi lumen once the protein is fully mature and trafficked to the plasma membrane. However, more recent studies have shown that at least 143 proteins are acetylated uniquely in the ER, including the System x

c- accessory protein, 4F2HC [

51].

Therefore, we tested the hypothesis that acetylation of K473 is necessary for xCT to transition appropriately through the secretory pathway by creating the structural acetylated lysine mimetic mutant, K473Q. Like K473R, we discovered that K473Q lacks transporter activity and exhibits decreased cell surface localization. Unlike K473R, however, we observed that K473Q is exported to the Golgi, supporting our hypothesis that acetylation of K473 may allow for ER export, but the acetylation mimic still prevents further progression out of the Golgi. Consistent with these findings, K473Q is 3.5 kD greater in molecular weight than K473R which we demonstrated results from its ability to be N- and O-glycosylated, similar to WT. Collectively, these data suggest that acetylation of K473 allows for both glycosylation of xCT as well as export to the Golgi. However, these data also suggest that deacetylation of K473 of xCT is necessary to transition out of the Golgi as has been noted for proteins which are acetylated in the ER [

50].

Our results also suggest that xCT is further post-translationally modified after being exported from the Golgi. Specifically, the fully glycosylated K473Q mutant remains nearly 4 kD less in molecular weight than WT xCT and does not traffic beyond the Golgi in the secretory pathway. In addition, treatment of WT xCT with PNGase-F and O-glycosidase (41 kD) results in a deglycoslyated protein that remains greater in molecular weight than K473R and K473Q. Thus, glycosylation represents only part of the basal post-translational modifications observed on xCT. Previous research has shown that xCT can be reversibly palmitoylated, phosphorylated, and O-GlcNAcylated [

28,

29], so other PTMs such as these may occur during post-Golgi trafficking of xCT and make up the extra approximately 3.5 kD that is not accounted for after WT is treated with both glycosidases.

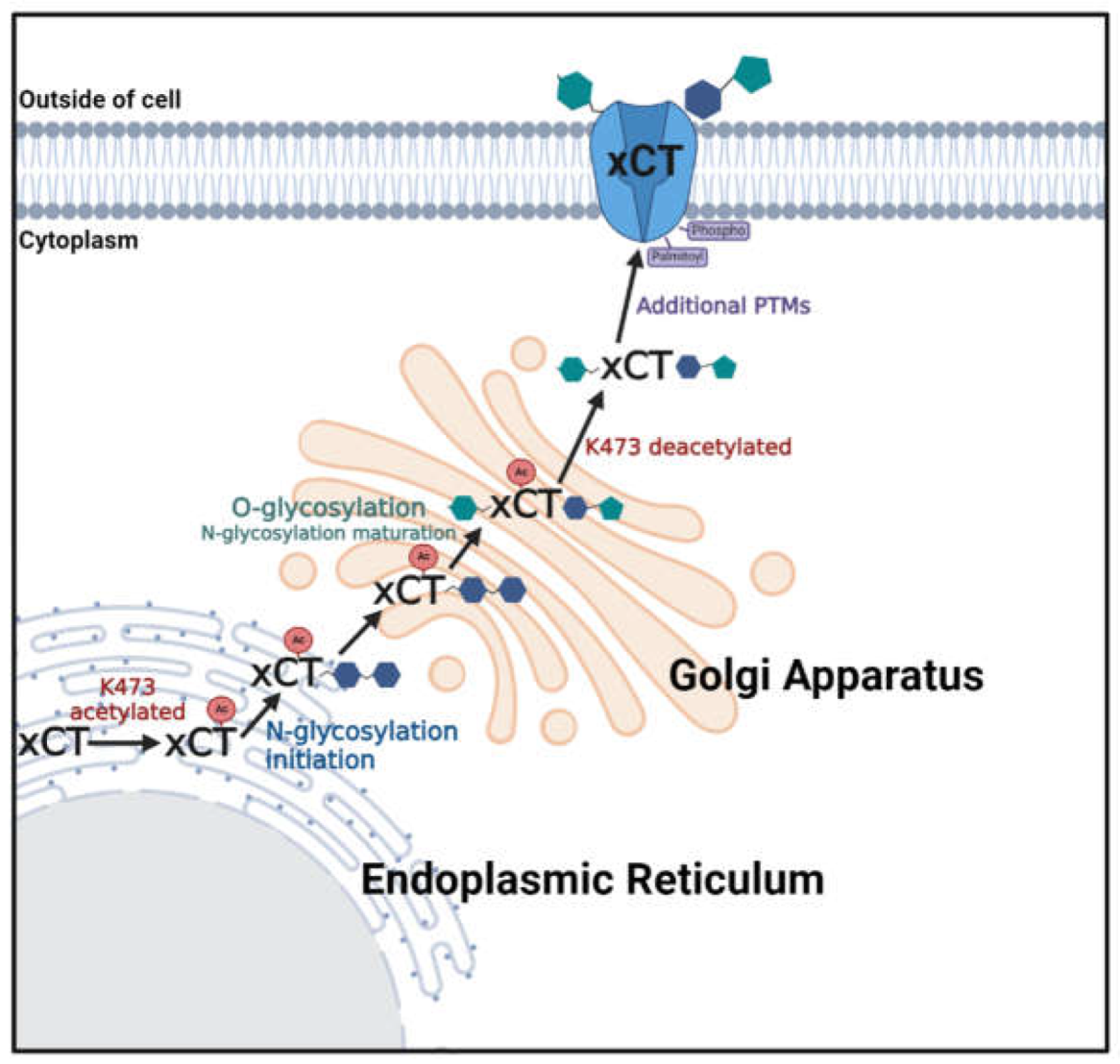

Based on these collective results, we have developed a hypothetical model for how K473 may serve as a site of regulation of xCT (

Figure 9) which is modeled after BACE1 processing. We suggest acetylation of K473 in the ER allows for the initiation of N- glycosylation and the subsequent export of xCT from the ER into the Golgi where it is O-glycosylated. Furthermore, we propose that xCT must be deacetylated at K473 in order to exit the Golgi, so that it can be further post-translationally modified and eventually trafficked to the plasma membrane. This model shares several similarities with other proteins that are known to be acetylated in the ER and deacetylated in the Golgi [

44,

50].

There are some important differences between the processing of xCT in the ER compared to the BACE1 and CD133, however, that must be acknowledged. 1) In the case of xCT, we find mutation of a single lysine is able to halt progression through the ER, whereas BACE acetylates seven lysines in the N-terminus prior to ER export. 2) In addition, K473 is found within a random coil that exists within the intracellular C-terminal tail. Thus, when synthesized in the ER, K473 of xCT faces the cytoplasmic compartment within the cisternae of the ER rather than the ER lumen. The acetylated lysines in BACE are localized to an extracellular region of the protein, thus are acetylated in the ER lumen. This distinction is important as it could mean that xCT is able to be acetylated by a greater array of acetylases that are localized in the cytoplasm relative to the ER. In addition, the acetylation of xCT would not be limited by ER lumenal acetyl CoA concentration as observed for BACE. 3) Finally, our data suggest that modification of K473 of xCT is necessary prior to xCT N-glycosylation while BACE is able to be glycosylated in the absence of lysine acetylation [

52]. This may suggest that unlike BACE1, lack of acetylation of K473 may be necessary for the recruitment of the oligosaccharyltransferase enzyme necessary for N-glycosylation of xCT.

Of course, we must acknowledge that more evidence is needed to develop full support for our proposed model. Most critically, we have yet to provide direct experimental evidence that K473 is acetylated

in vivo. Lysine can also be modified by many small molecule metabolites including formylation, succinylation, malonylation, butyrylation, propionylation, glutarylation, β-hydroxybutylation, 2-hydroxyisobutyryation, lactylation, benzoylation and crotonylation [

53], therefore, we are currently using a mass spectroscopy approach to address this question. However, the observation that the acetylation mutant K473Q is able to transition to the Golgi supports the hypothesis that K473 undergoes acetylation in the ER. In addition, the fact that the heterodimeric partner of xCT, 4F2HC, is also likely regulated by acetylation in the ER [

52] would allow for effective coordination of both xCT and 4F2HC translocation through the biosynthetic pathway.

In addition, identification of the acetylase/deacetylase enzymes which acetylate and deacetylate xCT will be critically important. Given that mutation of K473 alone is able to completely halt the translocation of xCT through the secretory pathway, identification of the acetylase that acts on K473 will allow us to understand how biosynthetic trafficking of this transporter is regulated at the cellular level. This idea is particularly intriguing given that acetylation is a key regulator of metabolism [

54], especially during instances of hypoxia/reperfusion and increased generation of reactive oxygen species [

55]. In other words, such a mechanism would allow for coordination of System x

c- activity and metabolic demands, allowing for increased capacity for cystine import and glutathione synthesis during times of increased vulnerability to oxidative stress. In addition, glutathione depletion increases lysine acetylation in astrocytes [

56], suggesting that xCT translocation through the biosynthetic pathway could be enabled in such conditions. Such a hypothesis is consistent with our previous observation that xCT exhibits an increased rate of trafficking to the plasma membrane during glutathione depletion[

1].

We also acknowledge the possibility that K473 may not be post-translationally modified in the ER and that the K473R mutation may instead disrupt protein folding to such an extent that the protein is sent immediately for degradation through the ERAD system, thus preventing it from becoming glycosylated. There is no question that K473 is highly conserved, and thus must be critical for xCT function or regulation. However, given that K473 is found in a region of the C-terminus that is less ordered and relatively far from the primary transporter transmembrane cluster which includes the cystine and glutamate translocation paths [

57], it is less likely that such a minor mutation would lead to significant unfolding. Moreover, given its location within a more peripheral random coiled structure is consistent with the hypothesis that this site is important for interaction with cell signaling or trafficking proteins [

58].

Further work must also be done to identify the site of xCT N-glycosylation that occurs in the ER. Based on our observation that treatment of xCT with PNGase-F led to a 2.5 kD reduction in molecular weight, there is likely only one N-glycosylation site on xCT. N-Acetylglucosamine (GlcNAc), mannose and the other monosaccharides typically found in N-linked oligosaccharides have molecular weights ranging from 0.18 to 0.22 kD/sugar. Therefore, a shift of 2.5 kD suggests between 11-14 sugars in the oligosaccharide which is the typical range observed for N-linked oligosaccharides in mammals. xCT has been predicted to be glycosylated at N314 [

59], this study is the first to provide experimental evidence that xCT is N-glycosylated

in vivo. However, given that the N314Q xCT mutant had the same molecular weight as WT and was sensitive to PNGaseF treatment, it is evident that N314 is not the site of N-glycosylation in this expression system. N314Q showed equivalent membrane localization as WT, despite exhibiting slightly reduced activity, suggesting that the mutation may have a modest impact on transporter function, but not localization.

Similarly, in this study we have provided the first evidence that xCT is also O-glycosylated. Neuraminidase and O-glycosidase cleave bonds between proteins and core 1 and 3 type oligosaccharides that are capped with sialic acid. Treatment of WT and K473Q xCT with these enzymes led to a 1.5 kD reduction in molecular weight which is consistent with the expected molecular weight of core 1 O-glycosylation structures which are most common in humans. For example, mass spectrometry analysis of the CD8β receptor has a single core 1 O-glycosylation site to which a 1.7 kD glycan is attached, suggesting that a core 1 glycan is likely attached to xCT [

60]. Thus future work will need to probe the functional role of O-glycosylation of xCT as well as identify the site of glycosylation.

In summary, we have identified a single, highly conserved lysine residue (K473) in an intracellular domain of the C-terminus of xCT that appears to regulate its progression through the ER and Golgi. Our results suggest that K473 may be transiently acetylated in the endoplasmic reticulum allowing for the glycosylation of xCT and its export to the Golgi. Once in the Golgi, K473 likely needs to be deacetylated to allow for complete post-translational modification of xCT and its export to the plasma membrane. Thus, this site may act as a molecular switch for rapidly regulating xCT trafficking and activity.

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Cell Culture

COS-7 cells were maintained in Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle Medium supplemented with 4 mM L-glutamine, 4500 mg/L glucose, 1 mM sodium pyruvate, 1500 mg/L NaCO3, 10% FBS and 1% penicillin/streptomycin in 100-mm dishes. Medium was changed every two to three days, and cultures were split 1:6 every 6-8 days. COS-7 cells were obtained from the American Type Culture Collection, and cells were not passaged over 15 times. Tissue culture media and chemicals were purchased from Thermo Fisher (Gibco).

4.2. Human myc-xCT and HA-4F2HC Constructs

Human xCT was subcloned into pCMV-3Tag-2A (Clonetech) vector at the EcoR1/HindIII site. Human CD98 was subcloned into pCMV-HA-N (Clonetech) at the EcoR1/NotI site [

1].

4.3. Creation of Mutants Using Site-Directed Mutagenesis

Several mutants, including K422R, K472R, K473R, K473Q, and N314Q, were created using the QuikChange Lightning Site-Directed Mutagenesis Kit (Agilent). The QuikChange Primer Design Program website was used to design optimal primers for mutagenesis. The primer sequences are given in

Table 1 All single-stranded primers were synthesized by IDT at the 25 nmol scale.

Stock primer solutions were created by resuspending each synthesized primer to a concentration of 1 mg/mL in DNase/RNase-free water. Next, working primer solutions (125 ng/µL) were prepared using the same nuclease free water. Reagents were combined in PCR tubes according to instructions detailed in the QuikChange Lightning Site-Directed Mutagenesis Kit Manual. The template DNA used in the sample reactions was the human xCT construct (section 4.2) purified from XL-10 Gold Competent Cells (Agilent). The PCR reactions were run in a thermocycler (Thermo Hybaid PX2) following the guidelines in the QuikChange manual. Next, DpnI digestion of the template DNA and transformation of XL10-Gold ultracompetent cells were performed according to the instructions in the QuikChange manual. The transformation reaction was placed on agar plates containing kanamycin (50 µg/mL) and incubated overnight. Insertion of the correct mutations was confirmed using DNA sequencing of the entire xCT gene (Eurofins).

4.4. Heterologous Expression of Human myc-xCT and HA-4F2HC in COS-7 Cells

Transfection quality cDNA was produced using the Pure Yield Plasmid Midi-prep system (Promega). myc-xCT (wildtype or mutant) and HA-4F2HC were co-transfected into COS-7 cells using FuGENE 6 (Promega) following manufacturer’s guidelines using a 3:1 ratio of FuGENE 6 to myc-xCT and a 3:1 ratio of FuGENE 6 to HA-4F2HC in antibiotic-free media. 18-24 hours later the media was replaced with growth medium which was maintained for 24 hours prior to the initiation of immunoprecipitation or cell surface biotinylation assays.

4.5. Glutamate Oxidase and HRP Assay for Measuring xCT Activity

Activity of xCT was measured using a high throughput glutamate release as outlined by [

61]. COS-7 cells grown and transiently transfected with myc-xCT (wt or mutant) and HA-4F2HC in a 96-well plates were washed twice with warm PBS (37

oC) and treated with 100 µL of warm cystine (80 µM) in Earle’s Balanced Salt Solution (mM: NaCl 116.4, NaHCO

3 26.2, NaH

2PO4 1.02, KCl 5.36, MgSO

4 0.81,CaCl

2 1.8 and Glucose 5.56, pH 7.4) and incubated for one hour at 37 °C. Enzyme solution (50 µL) consisting of Glutamate Oxidase (0.04 U/mL), Horseradish Peroxidase (0.125 U/mL), Amplex (50 µM), and 1x reaction buffer (100 mM Tris, pH 7.4) was added to each well. A plate reader was used to measure the fluorescence (530 nm excitation, 590 nm emission) in each well every 30 seconds for 5 minutes in order to obtain the initial rate of glutamate turnover. A standard curve of glutamate (0-20 µM) was used to convert rates of activity to concentration of glutamate released. Specific activity was determined by subtracting the average glutamate released (n=8) from untransfected cells from the glutamate released from transfected cells.

4.6. Immunoprecipitation for Isolating myc-xCT

COS-7 cells transiently transfected with myc-xCT (wildtype of mutant) and HA-4F2HC were grown to 90% confluence in 35 mM dishes. Plates were placed on ice and rinsed once with ice-cold phosphate buffered saline (PBS). Next, a cell lysis buffer (25 mM Tris, 0.15 M NaCl, 1 mM EDTA, 1% NP40, 5% glycerol; pH 7.4) containing protease inhibitor cocktail (Sigma G6521) was added to the plates. The plates were set on ice for 5 minutes and rocked.

The lysates were transferred to microcentrifuge tubes, centrifuged at 13,000 rpm for 10 minutes at room temperature, and the supernatant was transferred to new microcentrifuge tubes. Aliquots of lysate (250 μL) were added to equal volumes of Pierce Anti-c-Myc Magnetic Beads (25 μl) pre-washed with lysis buffer and incubated for 30 min at room temperature with gentle rocking.

The beads were then collected using a magnetic stand and the supernatants were transferred to new microcentrifuge tubes (unbound protein sample). The beads were washed three times with diluted 20X Mag c-Myc IP/Co-IP Buffer-2 (500 mM Tris, 3 M NaCl, 1% Tween-20 Detergent pH 7.5) and once with ultrapure water. The beads were resuspended using diluted 5X Non-reducing Sample Buffer (0.3 M Tris-HCl, pH 6.8, 5% SDS, 50% glycerol, lane marker tracking dye) and incubated for 10 minutes at 95 °C. The beads were collected using a magnetic stand and the supernatants were recovered (bound protein sample). All of the samples were stored and frozen at -20°C prior to Western blot analysis. Prior to electrophoresis, 1.3 µL of 30% SDS and 0.4 µL of β-mercaptoethanol were added to the immunoprecipitated samples to aid in xCT denaturation.

4.7. Biotinylation of Cell Surface Proteins

Biotinylation of cell surface proteins was performed using the method from Chase, et al. with the following modification [

1]. Transfected COS-7 were not serum-starved 24-hr prior to the experiment, and the avidin-lysate solution was rocked for 1 hour at room temperature.

4.8. PNGase F to Cleave N-Linked Oligosaccharides

The immunoprecipitation protocol was followed according to section 4.5 until resuspension of the beads. Instead of Non-Reducing Sample Buffer, the beads were resuspended in 1% RapiGest (Waters) in ddH2O. Aliquots of resuspended beads were transferred to new microcentrifuge tubes and heated at 95 °C for 10 minutes. Protease inhibitors, 10X GlycoBuffer 2, and PNGase F (New England Biolabs) were added to the beads. The reaction was incubated at 37 °C for 1 hour. The samples were taken for Western blot analysis and frozen at -20°C. To prepare the samples for electrophoresis, 4x Laemmli Sample Buffer (Bio-Rad) was added to the samples, as well as β-mercaptoethanol and 30% SDS in the same ratios as in the immunoprecipitated samples in section 4.6.

4.9. O-Glycosidase to Cleave O-Linked Oligosaccharides

The immunoprecipitation protocol was followed according to section 4.5 until resuspension of the beads. Instead of Non-Reducing Sample Buffer, the beads were resuspended in 1% RapiGest (Waters) in ddH2O. Aliquots of resuspended beads were transferred to new microcentrifuge tubes and heated at 95 °C for 10 minutes. Protease inhibitors, 10X GlycoBuffer 2,, α2-3,6,8 Neuraminidase, and O-Glycosidase (New England Biolabs) were added to the beads. The reaction was incubated at 37 °C for 3 hours. The samples were taken for Western blot analysis and frozen at -20°C. To prepare the samples for electrophoresis, 4x Laemmli Sample Buffer (Bio-Rad) was added to the samples, as well as β-mercaptoethanol and 30% SDS in the same ratios as in the immunoprecipitated samples in section 4.6.

4.10. Western Blot Analysis

Protein samples were electrophoresed at 200V on either 12% Mini-PROTEAN TGX Precast Protein Gels (Bio-Rad) or 10% Bolt Bis-Tris Plus Mini Protein Gels (Thermo Fisher) and transferred to a PVDF membrane (Millipore Immobilon-FL)) at 30 volts for 1 hour. The membranes were blocked with Intercept (TBS) Blocking Buffer (LI-COR 927-60001) for 1 hour at 4 °C. The membranes were probed with goat anti-myc (1:2500, Novus Biologicals NB600-335), rabbit anti-HA (1:1000, Cell Signaling #3724), rabbit anti-Ub (1:1000, Cell Signaling #43124) and/or rabbit anti-NEDD8 (1:1000, Cell Signaling #2754) in Intercept Blocking Buffer containing 0.2% Tween 20 overnight at 4 °C. The membranes were washed in TBS-T (0.1%) 3 times for 5 minutes each and incubated in the dark with donkey anti-goat IRDYE 680RD (LI-COR, 926-68074) and donkey anti-rabbit IRDYE 800CW (LI-COR, 926-32213), each diluted 1:15,000 in Intercept Blocking Buffer with 0.2% Tween 20 and 0.01% SDS. The membranes were washed 3 times for 5 minutes each in TBS-T (0.1%) and visualized using the Odyssey XF imaging system (LI-COR). Bands were analyzed also using the Image Studio software v 5.2.

4.11. Immunocytochemistry

COS-7 cells transiently transfected with myc-xCT (wildtype or mutant) and HA-4F2HC were grown on poly-L-lysine-coated coverslips (0.01%, Sigma P4707) placed in 6 well plates. Plates were removed, placed on ice and rinsed once with ice-cold PBS, fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde in PBS for 15 minutes. Cells were rinsed with PBS 3 times for 2 minutes each. Cells were then treated with ice-cold methanol for 10 minutes at -20 °C and washed with PBS one more time for 5 minutes. In preparation for immunostaining, cells were blocked by the addition of 5% donkey sera in PBS with 0.3% Tween-20 for 1 hour. Cells were incubated with with primary antibody for mouse anti-myc (1:100; SCBT #SC-40) or goat anti-myc (1:100; Novus), rabbit anti-protein disulfide isomerase (PDI) (1:100; Cell Signaling #3501T) or rabbit anti-GM130 (1:100; Cell Signaling #12480), and donkey anti-HA (1:100; ThermoFisher #190-138A) overnight at 4°C. Cells were washed 2 times with PBS and 1 time with dH2O for 10 minutes each and then incubated with Alexa-Fluor 488 conjugated donkey anti-mouse IgG, Rhodamine RedX conjugated donkey anti-rabbit IgG (1:100), and Alexa-Fluor 647 conjugated donkey-anti goat (JacksonImmuno) 1 hour at 4°C. The cells were washed 2 times with PBS and 1 time with H2O for 10 minutes each and the coverslips were mounted on slides with ProLong Diamond with DAPI (Thermoisher) and dried overnight in the dark. Slides were viewed using the Nikon A1R-si confocal microscope and imaged using NIS elements imaging software.

4.12. Immunocytochemistry Co-Localization Analysis

Manders co-localization analysis was performed using the open source software Fiji. Background was subtracted from each color channel of an image using the rolling ball method (radius 50 pixels). The cell was outlined to create a region of interest and the Colocalization Threshold macro was employed to determine the Manders coefficients for each cell. This macro uses the Costes, et al. method [

62] for determining threshold and calculating Mander’s coefficients. Significance of Manders coefficients for each cell marker and xCT were determined for mutants of xCT using One-Way ANOVA followed by a post-hoc Tukey test.

Figure 1.

(A) A cross-species amino acid sequence comparison of the C-terminus of xCT showing three highly conserved lysine residues (K422, K472, and K473). Lysine residues are highlighted in orange, bold type indicates fully conserved amino acids (identical across species), white italics indicate conservative amino acid substitutions. (B) Cryo-EM structure of System xc-. xCT is shown in blue and 4F2HC is shown in orange with K422, K472, and K473 side chains of xCT detailed on the intracellular surface. (C) Magnified view of intracellular interface of xCT and conserved lysines.

Figure 1.

(A) A cross-species amino acid sequence comparison of the C-terminus of xCT showing three highly conserved lysine residues (K422, K472, and K473). Lysine residues are highlighted in orange, bold type indicates fully conserved amino acids (identical across species), white italics indicate conservative amino acid substitutions. (B) Cryo-EM structure of System xc-. xCT is shown in blue and 4F2HC is shown in orange with K422, K472, and K473 side chains of xCT detailed on the intracellular surface. (C) Magnified view of intracellular interface of xCT and conserved lysines.

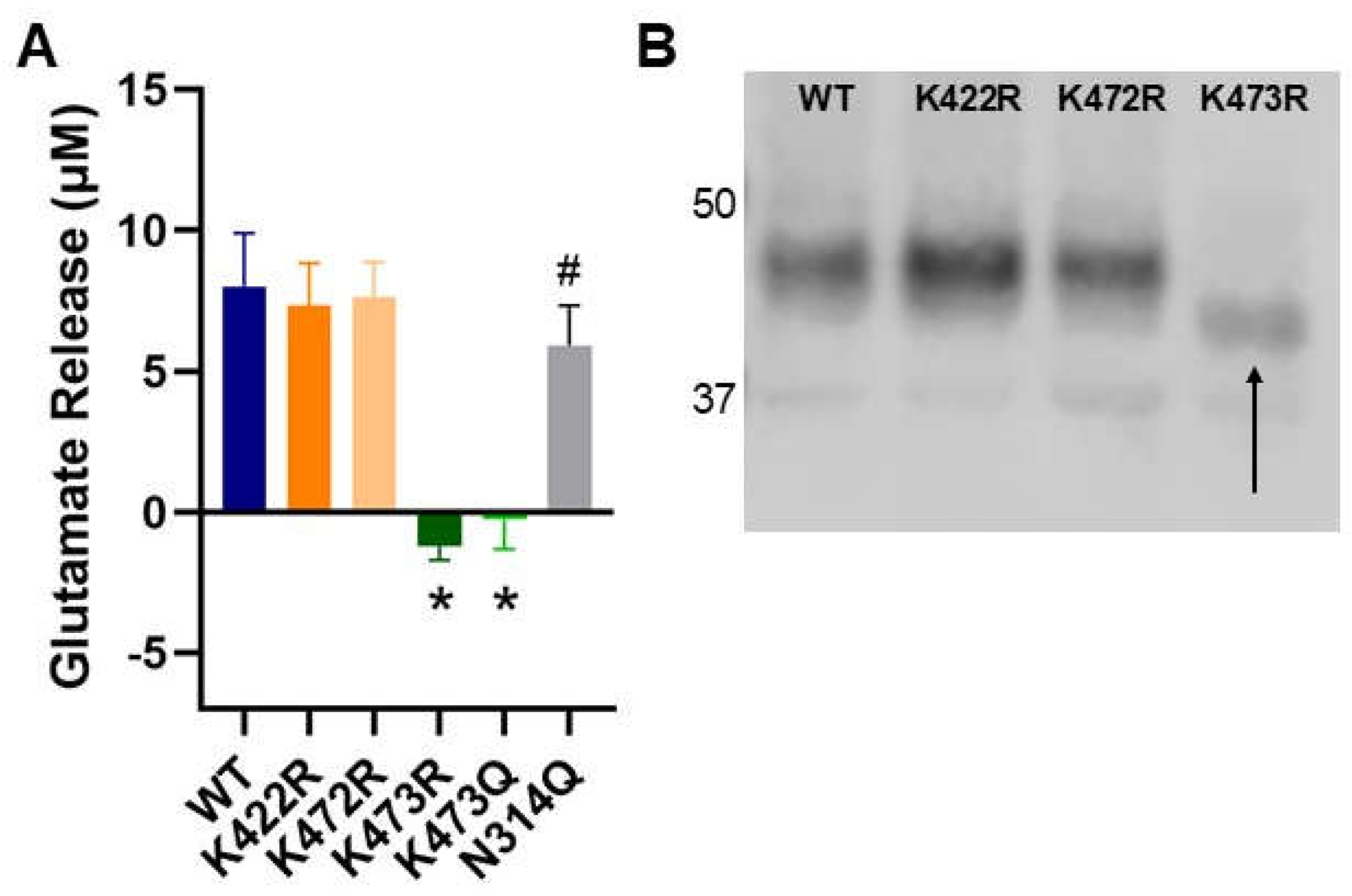

Figure 2.

(A) Activity of System xc- measured using a glutamate release assay. WT or mutant xCT were recombinantly coexpressed with 4F2HC in COS-7 cells. (n=8, *p<0.001 relative to WT, #p<0.05 relative to WT). (B) Molecular weight analysis of isolated WT and K→R xCT mutants. WT, K422R, and K472R appear to be the same molecular weight while K473R, as indicated with an arrow, is approximately 7.5 kD lower.

Figure 2.

(A) Activity of System xc- measured using a glutamate release assay. WT or mutant xCT were recombinantly coexpressed with 4F2HC in COS-7 cells. (n=8, *p<0.001 relative to WT, #p<0.05 relative to WT). (B) Molecular weight analysis of isolated WT and K→R xCT mutants. WT, K422R, and K472R appear to be the same molecular weight while K473R, as indicated with an arrow, is approximately 7.5 kD lower.

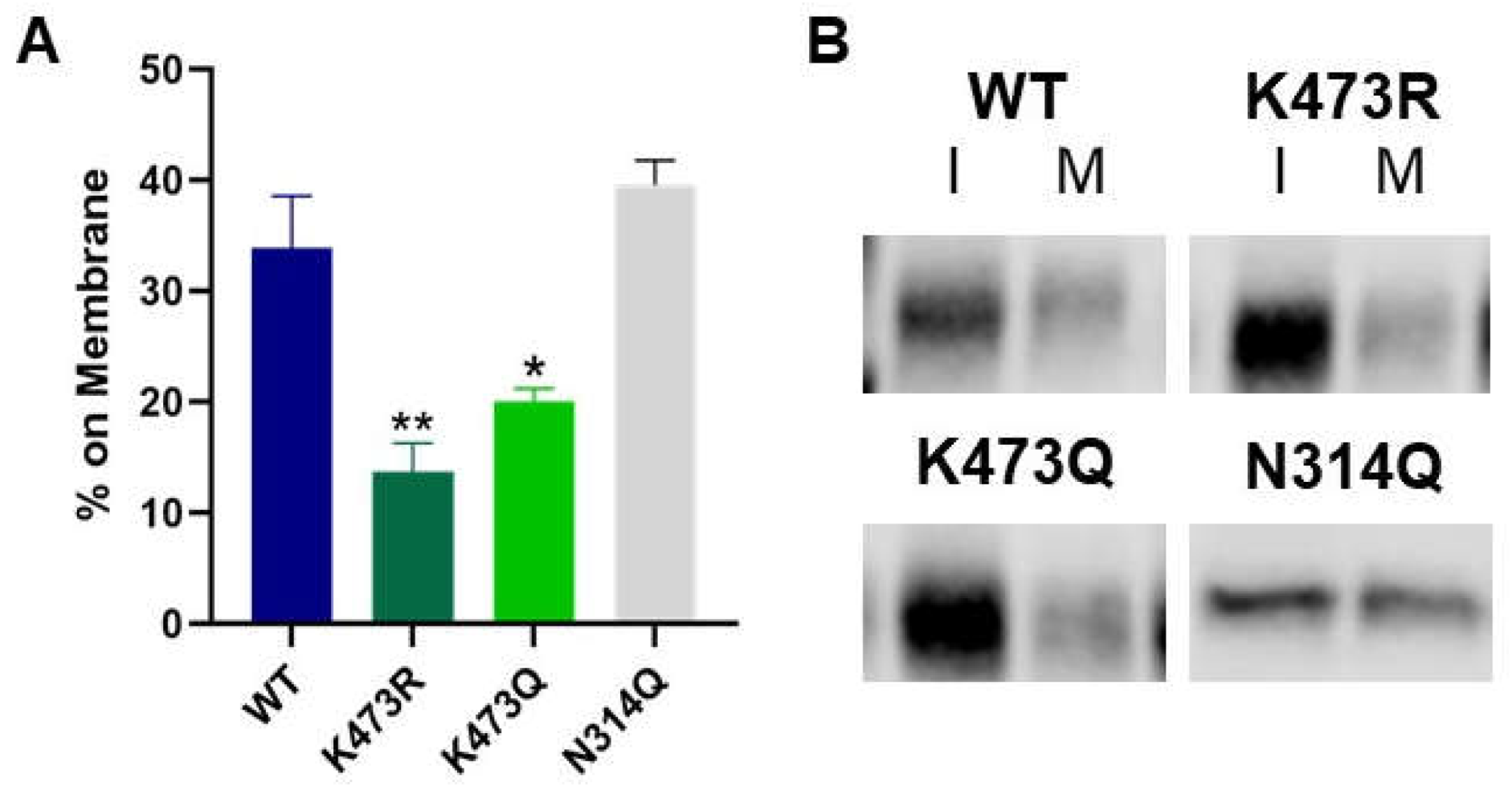

Figure 3.

(A) A cell surface biotinylation assay was performed followed by Western blot analysis to measure xCT in intracellular and membrane fractions. Average % on membrane values are plotted (n=6, *p<0.05, **p<0.001). (B) Representative intracellular (I) and membrane (M) bands of WT and xCT mutants from biotinylation assays. .

Figure 3.

(A) A cell surface biotinylation assay was performed followed by Western blot analysis to measure xCT in intracellular and membrane fractions. Average % on membrane values are plotted (n=6, *p<0.05, **p<0.001). (B) Representative intracellular (I) and membrane (M) bands of WT and xCT mutants from biotinylation assays. .

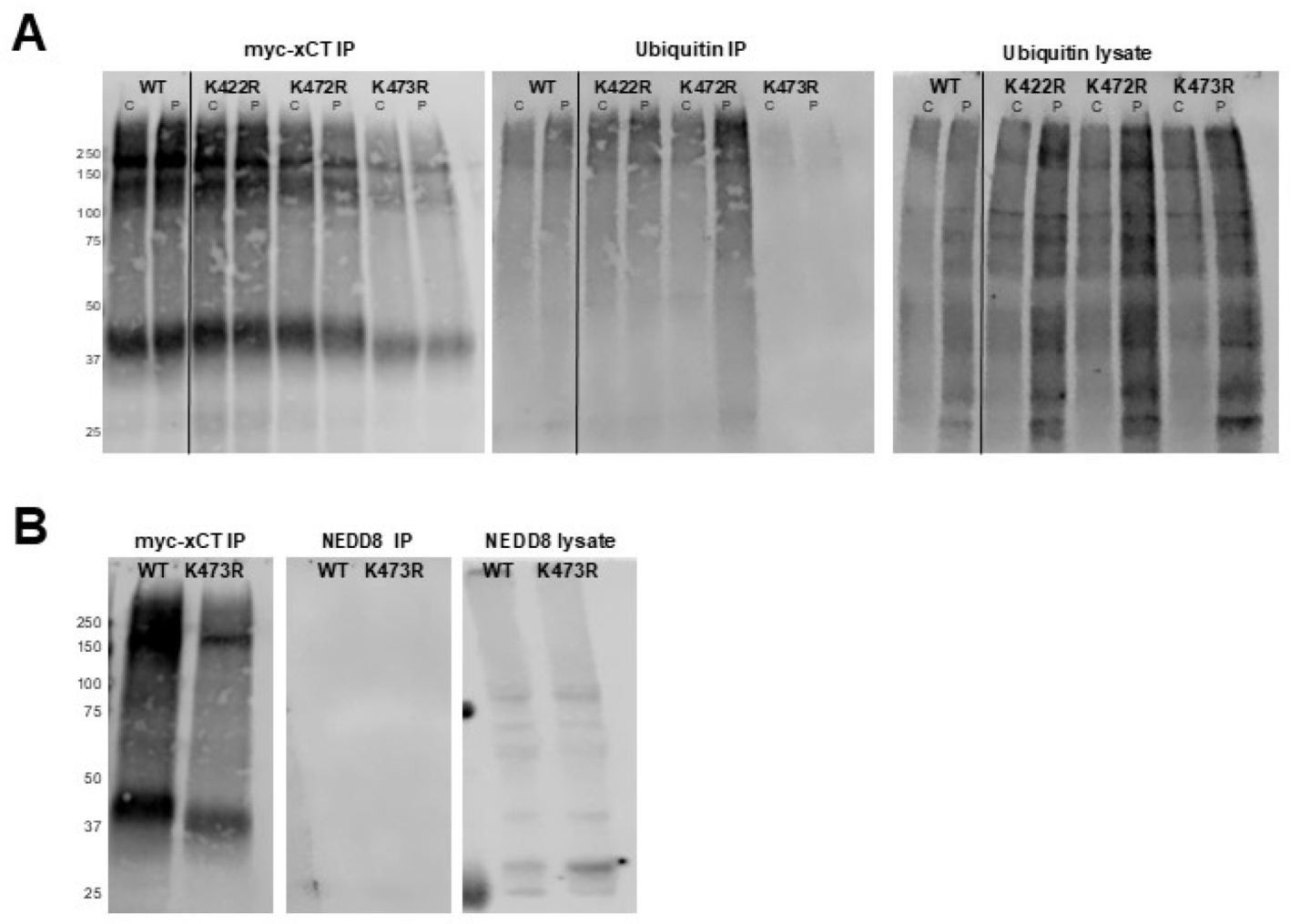

Figure 4.

(A) Assessment of the ubiquitination status of xCT. Western blots of immunoprecipitated myc-xCT were probed with anti-myc (left) or anti-ubiquitin (middle) antibodies. COS-7 cells were treated with 0.3 mM H2O2 (P) or vehicle (C) immediately prior to IP of myc-tagged proteins. The anti-ubiquitin signal in the original cell lysates (right) serves as a positive Ubiquitin antibody control. (B) Assessment of neddylation status of xCT. Western blots of immunoprecipitated myc-xCT were probed with anti-myc (left) and anti-NEDD8 (middle) antibodies. The anti-NEDD8 signal in the original cell lysates (right) serves as a positive NEDD8 antibody control.

Figure 4.

(A) Assessment of the ubiquitination status of xCT. Western blots of immunoprecipitated myc-xCT were probed with anti-myc (left) or anti-ubiquitin (middle) antibodies. COS-7 cells were treated with 0.3 mM H2O2 (P) or vehicle (C) immediately prior to IP of myc-tagged proteins. The anti-ubiquitin signal in the original cell lysates (right) serves as a positive Ubiquitin antibody control. (B) Assessment of neddylation status of xCT. Western blots of immunoprecipitated myc-xCT were probed with anti-myc (left) and anti-NEDD8 (middle) antibodies. The anti-NEDD8 signal in the original cell lysates (right) serves as a positive NEDD8 antibody control.

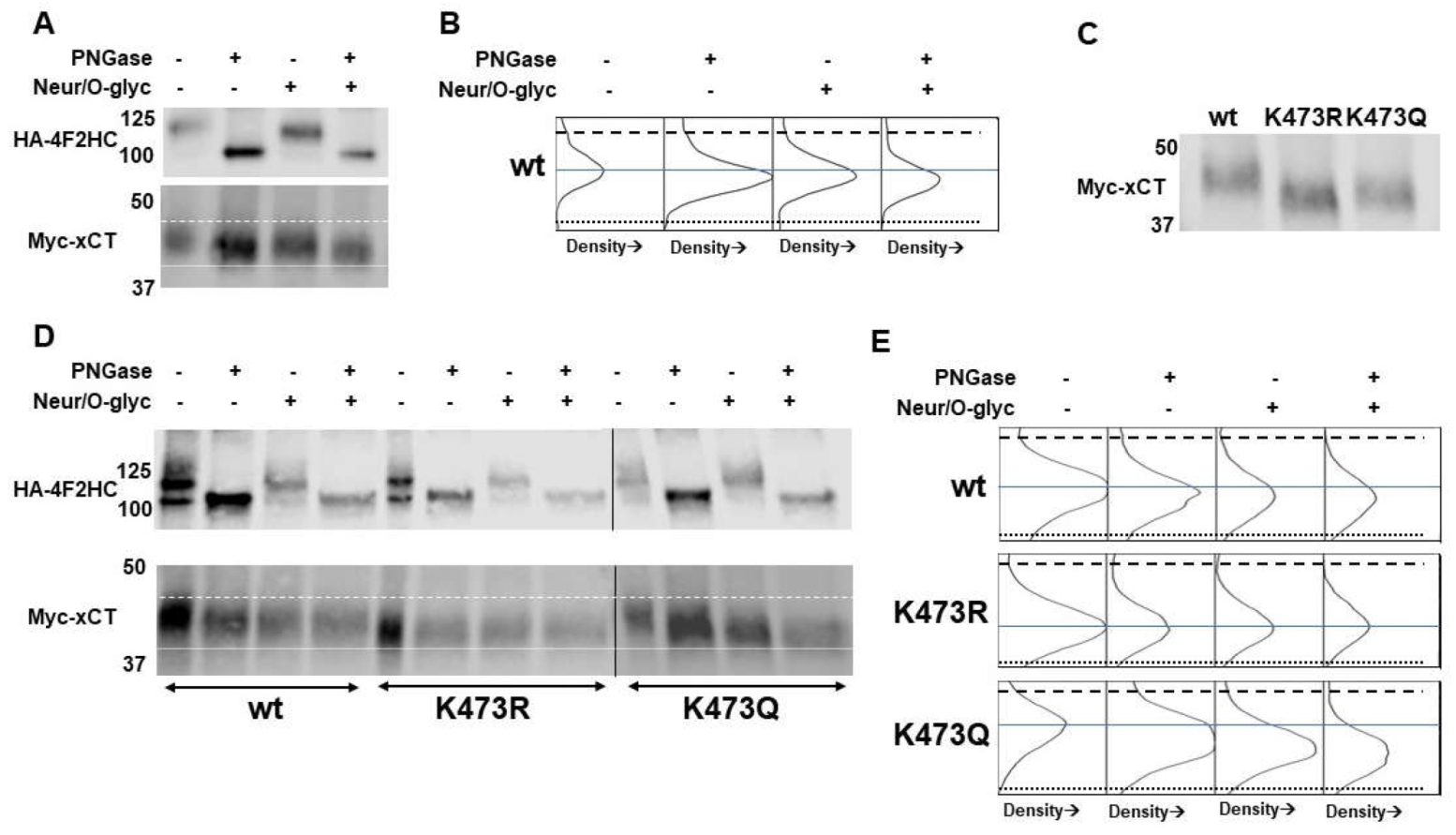

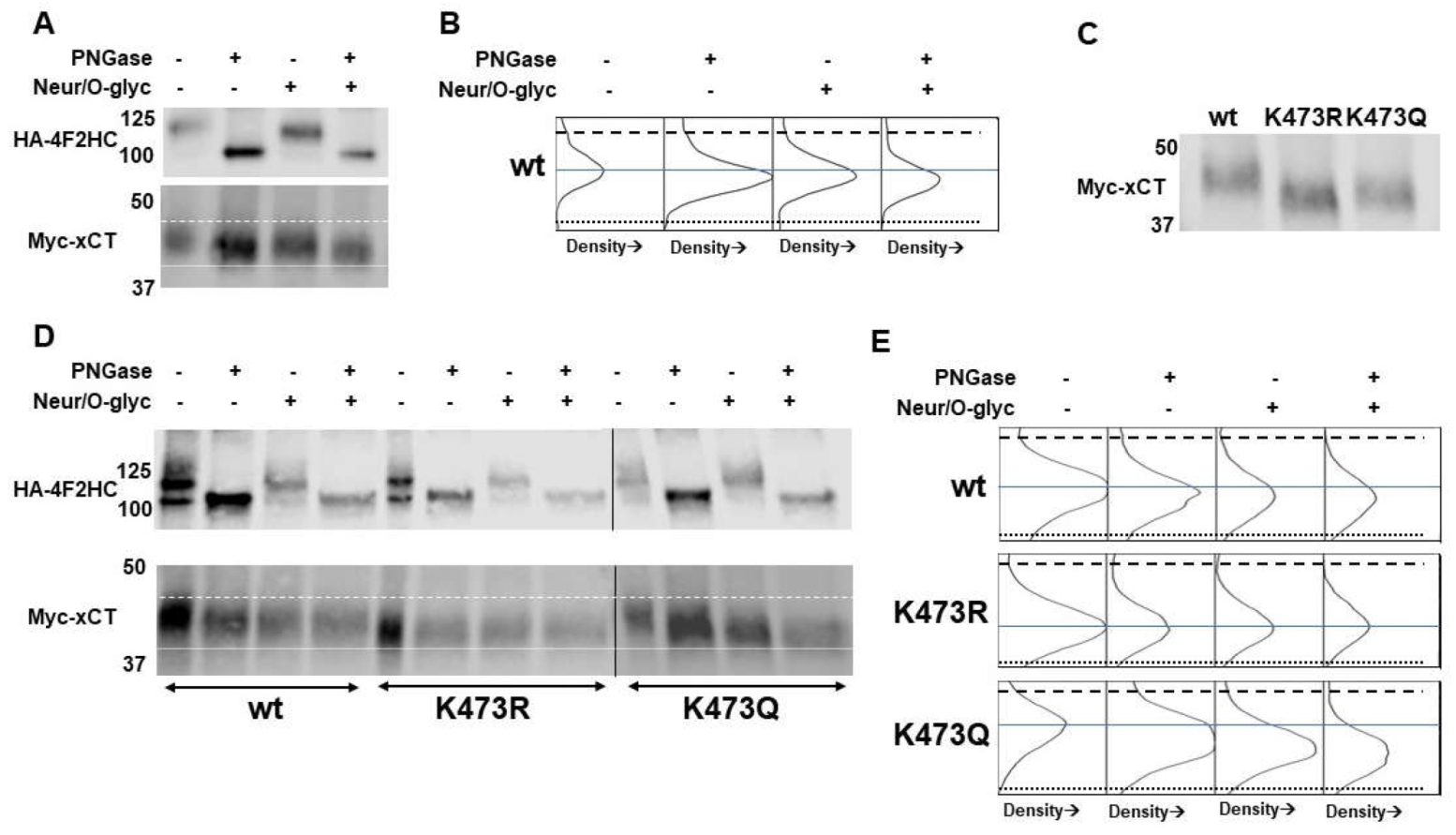

Figure 5.

(A) Immunoprecipitated WT myc-xCT treated with PNGase F, Neuraminidase/O-glycosidase (Neur/O-glyc), or all glycosidases. The monomer of xCT (bottom myc-xCT signal) shows molecular weight reductions of 2.5 kD, 1.5 kD, and 4 kD when treated with PNGase F, Neur/O-glyc, and all glycosidases, respectively. 4F2HC (top HA-4F2HC signal) serves as a positive control for PNGase F. Dashed line indicates position of the top of WT xCT band. Dotted line denotes position of the bottom of the WT xCT band treated with all glycosidases. (B) Density plots for the bands of the xCT monomer when treated with PNGase F, Neur/O-glyc, and both. Dashed and dotted lines from blot in A are added for reference. The solid blue line indicates the middle of the untreated WT band to aid in assessment of molecular weight shifts. (C) Molecular weight analysis of immunoprecipitated WT, K473R, and K473Q. (D) Immunoprecipitated WT, K473R, and K473Q treated with PNGase F, Neur/O-glyc, or all glycosidases. K473R shows no molecular weight changes with glycosidase treatment. K473Q shows molecular weight reductions when treated with PNGase F, Neur/O-glyc, and all glycosidases. Dashed line indicates position of top of the WT xCT band. Dotted line indicates the bottom of the K473R band. (E) Density plots for WT, K473R, and K473Q. Dashed and dotted lines from blot in D are added for reference. The solid blue line indicates the middle of the untreated xCT band for WT, K473R or K473Q to aid in assessment of molecular weight shifts.

Figure 5.

(A) Immunoprecipitated WT myc-xCT treated with PNGase F, Neuraminidase/O-glycosidase (Neur/O-glyc), or all glycosidases. The monomer of xCT (bottom myc-xCT signal) shows molecular weight reductions of 2.5 kD, 1.5 kD, and 4 kD when treated with PNGase F, Neur/O-glyc, and all glycosidases, respectively. 4F2HC (top HA-4F2HC signal) serves as a positive control for PNGase F. Dashed line indicates position of the top of WT xCT band. Dotted line denotes position of the bottom of the WT xCT band treated with all glycosidases. (B) Density plots for the bands of the xCT monomer when treated with PNGase F, Neur/O-glyc, and both. Dashed and dotted lines from blot in A are added for reference. The solid blue line indicates the middle of the untreated WT band to aid in assessment of molecular weight shifts. (C) Molecular weight analysis of immunoprecipitated WT, K473R, and K473Q. (D) Immunoprecipitated WT, K473R, and K473Q treated with PNGase F, Neur/O-glyc, or all glycosidases. K473R shows no molecular weight changes with glycosidase treatment. K473Q shows molecular weight reductions when treated with PNGase F, Neur/O-glyc, and all glycosidases. Dashed line indicates position of top of the WT xCT band. Dotted line indicates the bottom of the K473R band. (E) Density plots for WT, K473R, and K473Q. Dashed and dotted lines from blot in D are added for reference. The solid blue line indicates the middle of the untreated xCT band for WT, K473R or K473Q to aid in assessment of molecular weight shifts.

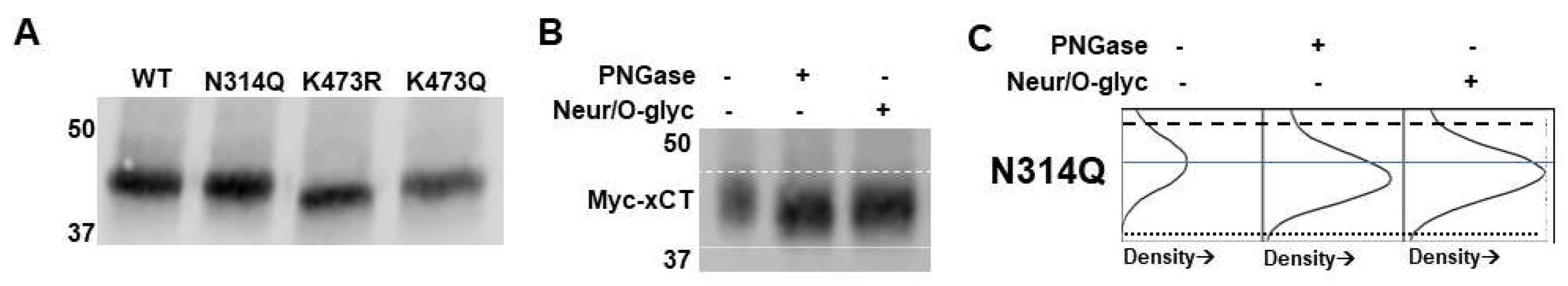

Figure 6.

(A) Molecular weight analysis of immunoprecipitated WT, N314Q, K473R, and K473Q. (B) N314Q shows molecular weight reductions when treated with PNGase F and Neur/O-glyc, similar to WT. The dashed line indicates the position of top of the N314Q band. The dotted line indicates the position of the bottom of the N314Q band treated with PNGaseF. (C) Density plots for the bands of N314Q when treated with PNGase F and Neur/O-glyc to more clearly show molecular weight shifts. Dashed and dotted lines from blot in D are added for reference. The solid blue line indicates the middle of the untreated N314Q xCT band to aid in assessment of molecular weight shifts.

Figure 6.

(A) Molecular weight analysis of immunoprecipitated WT, N314Q, K473R, and K473Q. (B) N314Q shows molecular weight reductions when treated with PNGase F and Neur/O-glyc, similar to WT. The dashed line indicates the position of top of the N314Q band. The dotted line indicates the position of the bottom of the N314Q band treated with PNGaseF. (C) Density plots for the bands of N314Q when treated with PNGase F and Neur/O-glyc to more clearly show molecular weight shifts. Dashed and dotted lines from blot in D are added for reference. The solid blue line indicates the middle of the untreated N314Q xCT band to aid in assessment of molecular weight shifts.

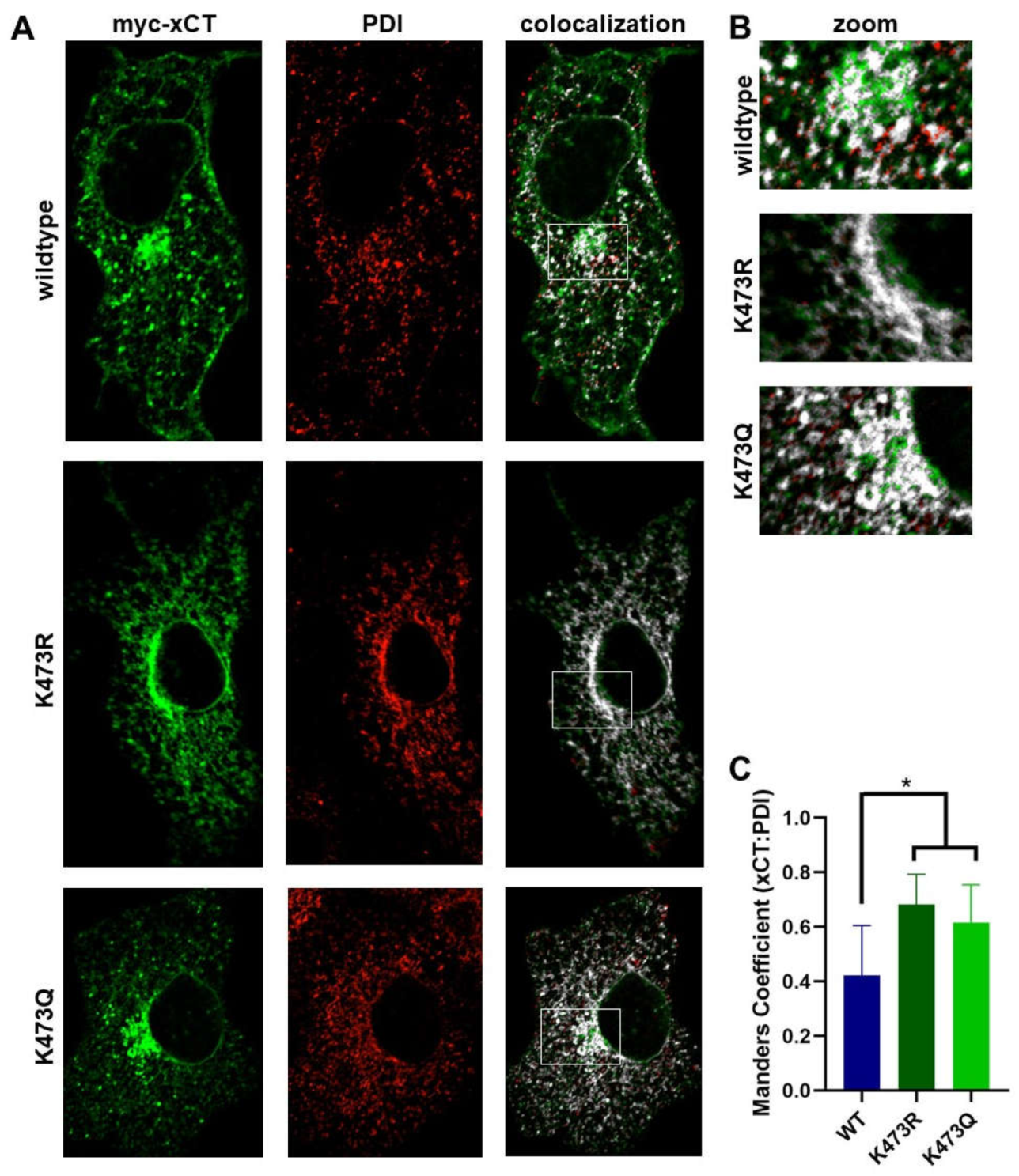

Figure 7.

(A) Immunocytochemistry coupled with confocal microscopy was used to examine the colocalization of WT, K473R and K473Q xCT with PDI, an ER marker. Confocal images show myc-xCT (green), PDI (red), and the Maders colocalization of xCT with PDI (white). (B) Zoom image of area of prominent ER density for each xCT construct indicated by white box in A. (C) Fraction of xCT signal that is colocalized with PDI was calculated by performing a Manders colocalization analysis (*p<0.01).

Figure 7.

(A) Immunocytochemistry coupled with confocal microscopy was used to examine the colocalization of WT, K473R and K473Q xCT with PDI, an ER marker. Confocal images show myc-xCT (green), PDI (red), and the Maders colocalization of xCT with PDI (white). (B) Zoom image of area of prominent ER density for each xCT construct indicated by white box in A. (C) Fraction of xCT signal that is colocalized with PDI was calculated by performing a Manders colocalization analysis (*p<0.01).

Figure 8.

(A) Immunocytochemistry coupled with confocal microscopy was used to examine the localization of WT, K473R and K473Q with GM130, a Golgi marker. Confocal images show myc-xCT (green), GM130 (red), and Manders colocalization of xCT with GM130 (white). (B) Zoom image of area of membrane at the cell surface with arrows showing areas of high xCT density. (C) Fraction of xCT signal that is colocalized with GM130 was calculated by performing a Manders colocalization analysis (*p<0.01).

Figure 8.

(A) Immunocytochemistry coupled with confocal microscopy was used to examine the localization of WT, K473R and K473Q with GM130, a Golgi marker. Confocal images show myc-xCT (green), GM130 (red), and Manders colocalization of xCT with GM130 (white). (B) Zoom image of area of membrane at the cell surface with arrows showing areas of high xCT density. (C) Fraction of xCT signal that is colocalized with GM130 was calculated by performing a Manders colocalization analysis (*p<0.01).

Figure 9.

Model of K473 regulated trafficking of xCT through the biosynthetic pathway.

Figure 9.

Model of K473 regulated trafficking of xCT through the biosynthetic pathway.

Table 1.

Forward and reverse primer sequences for the creation of xCT mutants.

Table 1.

Forward and reverse primer sequences for the creation of xCT mutants.

| Mutant |

Forward |

Reverse |

| K422R |

5’-aacagtggcaccctgaaaggacgatgcatatctggg-3’ |

5’-cccagatatgcatcgtcctttcagggtgccactgtt-3’ |

| K472R |

5’-ttatctctttattatatgggacaggaaacccaggtggtttagaataa-3’ |

5’-aatagagaaataatataccctgttctttgggtccaccaaatcttatt-3’ |

| K473R |

5’-tctaaaccacctgggtctcttgtcccatataataaagagataatac-3’ |

5’-gtattatctctttattatatgggacaagagacccaggtggtttaga-3’ |

| K473Q |

5’-tgacattattctaaaccacctgggctgcttgtcccatataataaagagata-3’ |

5’-tatctctttattatatgggacaagcagcccaggtggtttagaataatgtca-3’ |

| N314Q |

5’-cggaactgctaatgagaactgtcccagtagccgctcaga-3’ |

5’-tctgagcggctactgggacagttctcattagcagttccg-3’ |