1. Introduction

Osteosarcoma, also termed osteogenic sarcoma, stands as the most common primary malignant bone tumour, accounting for approximately 20% of all primary bone cancers and representing a significant clinical challenge in paediatric and adolescent oncology (Mirabello et al., 2009). This aggressive neoplasm originates from primitive bone-forming mesenchymal cells and is characterised by the production of osteoid matrix by malignant cells, distinguishing it from other bone tumours (Czarnecka et al., 2020). The disease exhibits a distinctive bimodal age distribution, with the primary peak occurring during the second decade of life, coinciding with periods of rapid skeletal growth, and a secondary, smaller peak observed in older adults, typically associated with pre-existing bone pathology such as Paget's disease or previous radiation exposure (Ottaviani & Jaffe, 2009).

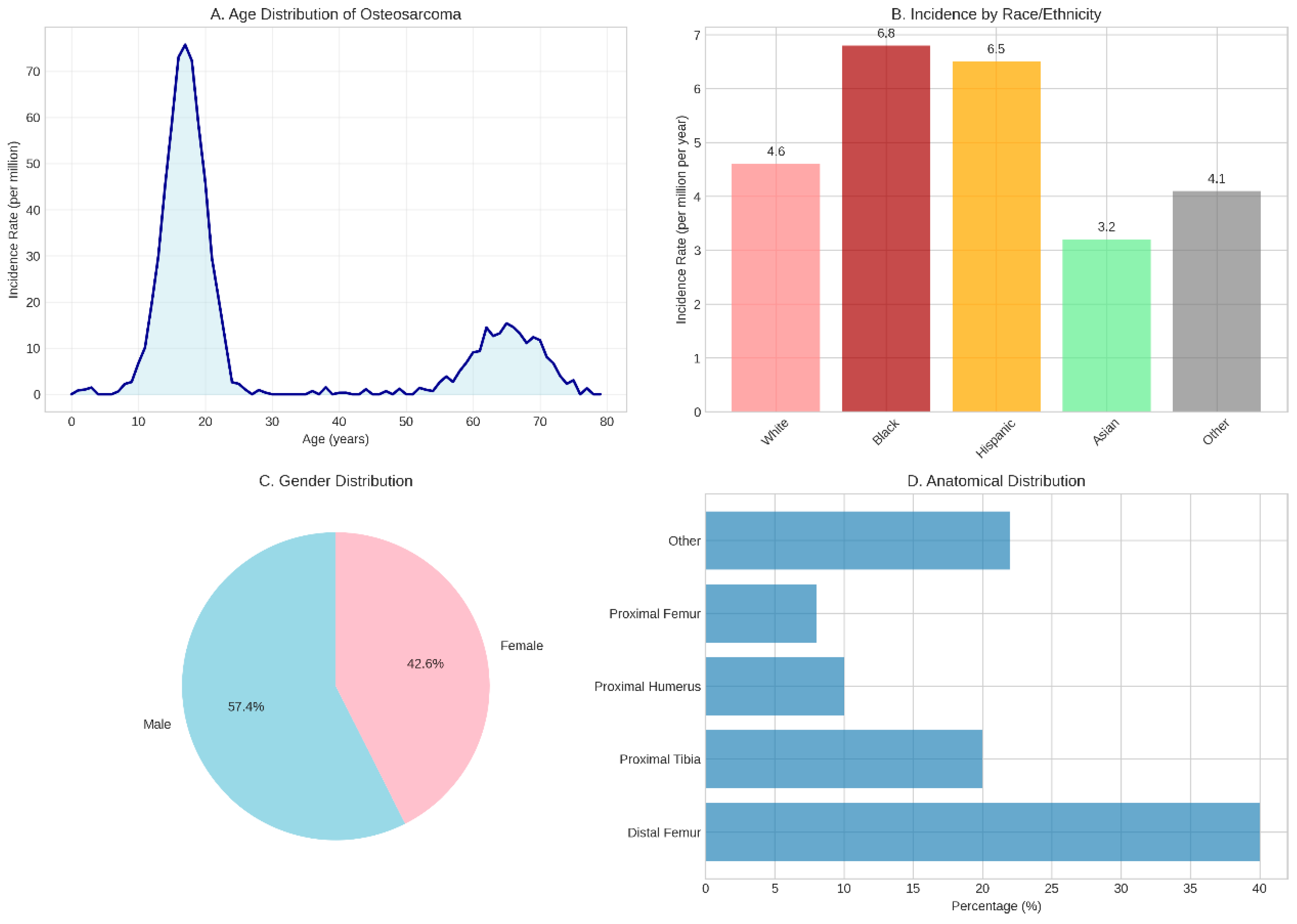

The epidemiological landscape of osteosarcoma reveals intriguing patterns that provide insights into its aetiology and pathogenesis. Globally, the incidence rate ranges from 3 to 5 cases per million individuals annually, with notable variations across different demographic groups (Siegel et al., 2023). Males demonstrate a slightly higher predisposition than females, with incidence rates of 5.4 and 4.0 per million per year, respectively (Geller & Gorlick, 20l0). Racial and ethnic disparities are particularly striking, with Black and Hispanic populations exhibiting significantly higher incidence rates (6.8 and 6.5 per million per year, respectively) compared to White populations (4.6 per million per year) (Mirabello et al., 20l3). These epidemiological variations suggest complex interactions between genetic susceptibility, environmental factors, and possibly socioeconomic determinants that warrant further investigation.

The anatomical distribution of osteosarcoma demonstrates a clear predilection for the metaphyseal regions of long bones, particularly those experiencing rapid growth during adolescence. The distal femur represents the most common site, accounting for approximately 40% of cases, followed by the proximal tibia (20%), proximal humerus (l0%), and proximal femur (8%) (Bielack et al., 2002). This distribution pattern strongly correlates with sites of maximal bone growth velocity during puberty, supporting the hypothesis that rapid bone turnover and cellular proliferation create a permissive environment for malignant transformation. Less commonly, osteosarcoma may arise in flat bones, including the pelvis, ribs, and skull, though these locations are more frequently observed in older patients and often associated with secondary forms of the disease.

The clinical presentation of osteosarcoma typically manifests as progressive bone pain, initially associated with physical activity but eventually becoming constant and severe. This pain often precedes the development of a palpable mass and may be accompanied by functional impairment of the affected limb (Bacci et al., 2006). Unfortunately, the insidious onset and non-specific nature of early symptoms frequently result in diagnostic delays, with patients often experiencing symptoms for weeks to months before seeking medical attention. This delay in diagnosis can have profound implications for prognosis, as early detection and prompt initiation of treatment are crucial factors influencing survival outcomes.

The pathophysiology of osteosarcoma involves complex molecular mechanisms that have been increasingly elucidated through advances in genomic and molecular biology research. The disease is characterised by significant genomic instability, with tumours exhibiting complex karyotypes, numerous chromosomal aberrations, and high mutation burdens (Behjati et al., 20l7). Key tumour suppressor genes, particularly TP53 and RBl, are frequently altered in osteosarcoma, with mutations detected in 65-90% and 70% of cases, respectively (Kansara et al., 20l4). These genetic alterations disrupt critical cellular processes including cell cycle regulation, DNA repair mechanisms, and apoptotic pathways, ultimately leading to uncontrolled cellular proliferation and malignant transformation.

The molecular landscape of osteosarcoma extends beyond individual gene mutations to encompass dysregulation of entire signalling pathways. The PI3K/AKT/mTOR pathway, which plays a central role in cellular metabolism, growth, and survival, is frequently hyperactivated in osteosarcoma (Zhou et al., 20l4). Similarly, the MAPK signalling cascade, which regulates cell proliferation and differentiation, demonstrates aberrant activation in many cases (Yu & Yao, 2024). These pathway alterations not only contribute to tumourigenesis but also represent potential therapeutic targets for novel treatment approaches.

The tumour microenvironment in osteosarcoma presents unique challenges and opportunities for therapeutic intervention. Unlike many other solid tumours, osteosarcoma typically exhibits low immunogenicity and an immunosuppressive microenvironment, characterised by limited T-cell infiltration and reduced expression of immune checkpoint molecules (Wedekind et al., 20l8). This immunological landscape has significant implications for the development and efficacy of immunotherapeutic approaches, necessitating innovative strategies to overcome immune evasion mechanisms.

Current treatment paradigms for osteosarcoma have remained relatively unchanged for several decades, centring on a multimodal approach combining neoadjuvant chemotherapy, surgical resection, and adjuvant chemotherapy. Standard chemotherapeutic regimens typically include high-dose methotrexate, doxorubicin, and cisplatin, with or without ifosfamide (Bielack et al., 20l5). Whilst this approach has achieved remarkable success in patients with localised disease, with five-year survival rates reaching 60-70%, outcomes for patients with metastatic or recurrent disease remain dismal (Isakoff et al., 20l5). The plateau in survival improvements observed over the past four decades underscores the urgent need for novel therapeutic strategies.

The challenge of metastatic disease represents one of the most significant obstacles in osteosarcoma management. Approximately l5-20% of patients present with detectable metastases at diagnosis, most commonly to the lungs, whilst an additional proportion develop metachronous metastases despite aggressive local and systemic therapy (Kager et al., 2003). The propensity for pulmonary metastasis reflects the haematogenous spread pattern characteristic of osteosarcoma, with tumour cells demonstrating particular affinity for the pulmonary vasculature. Patients with metastatic disease face a grim prognosis, with five-year survival rates of only 20-30%, highlighting the critical need for more effective systemic therapies.

Recent advances in molecular biology and genomics have opened new avenues for understanding osteosarcoma pathogenesis and identifying potential therapeutic targets. High-throughput sequencing technologies have revealed the remarkable genomic complexity of osteosarcoma, with tumours exhibiting extensive chromosomal instability, chromothripsis, and complex structural rearrangements (Kovac et al., 20l5). These findings have led to the identification of novel molecular subtypes based on distinct genomic and transcriptomic profiles, offering the potential for personalised treatment approaches tailored to individual tumour characteristics.

The concept of precision medicine in osteosarcoma is gaining momentum, with researchers working to develop molecular classification systems that can guide treatment selection and predict therapeutic response. Recent studies have identified four distinct molecular subtypes: immune-activated, immune-suppressed, metabolic, and proliferative, each characterised by unique biological features and clinical behaviours (Ren et al., 2022). This molecular stratification approach holds promise for optimising treatment selection and improving outcomes through personalised therapeutic strategies.

Environmental factors also play a significant role in osteosarcoma development, particularly in the context of secondary tumours. Therapeutic radiation exposure represents the most well-established environmental risk factor, with survivors of childhood cancers who received radiotherapy demonstrating significantly increased risk of developing osteosarcoma in previously irradiated fields (Hawkins et al., l996). The latency period between radiation exposure and osteosarcoma development typically ranges from 5 to 25 years, with risk correlating with radiation dose and patient age at exposure. Similarly, Paget's disease of bone, a chronic disorder characterised by abnormal bone remodelling, predisposes to secondary osteosarcoma development in approximately l% of affected individuals (Haibach et al., l985).

The diagnostic landscape for osteosarcoma continues to evolve, with traditional imaging modalities being supplemented by advanced molecular and genetic testing approaches. Whilst plain radiography remains the initial imaging modality for suspected bone lesions, magnetic resonance imaging has become indispensable for local staging and surgical planning (Murphey et al., 2002). Positron emission tomography combined with computed tomography (PET-CT) provides valuable information regarding metabolic activity and potential metastatic disease, though its role in routine surveillance remains debated (Costelloe et al., 20l4). The integration of molecular biomarkers, including circulating tumour DNA, microRNAs, and protein markers, represents an exciting frontier in osteosarcoma diagnostics, offering the potential for earlier detection, prognostic stratification, and treatment monitoring.

As we advance into an era of precision oncology, the importance of comprehensive molecular characterisation of osteosarcoma cannot be overstated. The integration of genomic, transcriptomic, proteomic, and metabolomic data promises to provide unprecedented insights into tumour biology and therapeutic vulnerabilities. This multi-omics approach, combined with advances in artificial intelligence and machine learning, holds the potential to revolutionise osteosarcoma diagnosis, prognosis, and treatment selection, ultimately improving outcomes for patients afflicted with this devastating disease.

2. Methodology

2.1. Literature Search Strategy

A comprehensive systematic literature review was conducted to identify relevant studies on osteosarcoma epidemiology, genomics, environmental factors, diagnostics, and therapeutic advances. Multiple electronic databases were searched, including PubMed/MEDLINE, Embase, Web of Science, and Cochrane Library, covering publications from January 2000 to December 2024. The search strategy employed a combination of Medical Subject Headings (MeSH) terms and free-text keywords, including "osteosarcoma," "osteogenic sarcoma," "bone cancer," "genomics," "molecular biology," "immunotherapy," "targeted therapy," "biomarkers," and "epidemiology."

Search terms were combined using Boolean operators (AND, OR) to maximise sensitivity whilst maintaining specificity. The search was limited to English-language publications, human studies, and peer-reviewed articles. Additional sources were identified through manual screening of reference lists from key articles and review papers. Grey literature, including conference abstracts and clinical trial registries (ClinicalTrials.gov, European Clinical Trials Database), was also searched to identify ongoing or recently completed studies.

2.2. Study Selection and Data Extraction

Studies were included if they met the following criteria: (l) original research articles or systematic reviews focusing on osteosarcoma; (2) studies investigating epidemiological patterns, genetic alterations, environmental risk factors, diagnostic methods, or therapeutic interventions; (3) studies with clearly defined methodology and adequate sample sizes; and (4) publications in peer-reviewed journals. Exclusion criteria included case reports with fewer than l0 patients, studies focusing exclusively on animal models without clinical correlation, and articles lacking sufficient methodological detail.

Two independent reviewers screened titles and abstracts for relevance, with full-text articles retrieved for potentially eligible studies. Data extraction was performed systematically using a standardised form, capturing study characteristics, population demographics, methodology, key findings, and limitations. Discrepancies between reviewers were resolved through discussion and consensus.

2.3. Data Analysis and Visualisation

Epidemiological data were analysed to identify patterns in incidence, age distribution, gender predilection, and anatomical location preferences. Genomic data were synthesised to determine mutation frequencies, chromosomal alterations, and pathway dysregulation patterns. Treatment outcome data were compiled to assess historical trends in survival rates and response to various therapeutic modalities.

Statistical analysis was performed using Python 3.ll with specialised libraries including NumPy, Pandas, Matplotlib, and Seaborn for data manipulation and visualisation. Descriptive statistics were calculated for continuous variables, whilst categorical variables were presented as frequencies and percentages. Visualisations were created to illustrate key findings, including age distribution curves, mutation frequency charts, treatment outcome trends, and biomarker performance metrics.

2.4. Quality Assessment

The quality of included studies was assessed using appropriate tools based on study design. For observational studies, the Newcastle-Ottawa Scale was employed, whilst randomised controlled trials were evaluated using the Cochrane Risk of Bias tool. Systematic reviews and meta-analyses were assessed using the AMSTAR-2 checklist. Studies with significant methodological limitations or high risk of bias were excluded from the analysis.

2.5. Synthesis of Evidence

Evidence synthesis was conducted through narrative review methodology, given the heterogeneity of study designs, populations, and outcomes across the included literature. Findings were organised thematically according to the main research domains: epidemiology, genomics, environmental factors, diagnostics, and therapeutics. Where appropriate, quantitative data were pooled to provide summary estimates, though formal meta-analysis was not performed due to study heterogeneity.

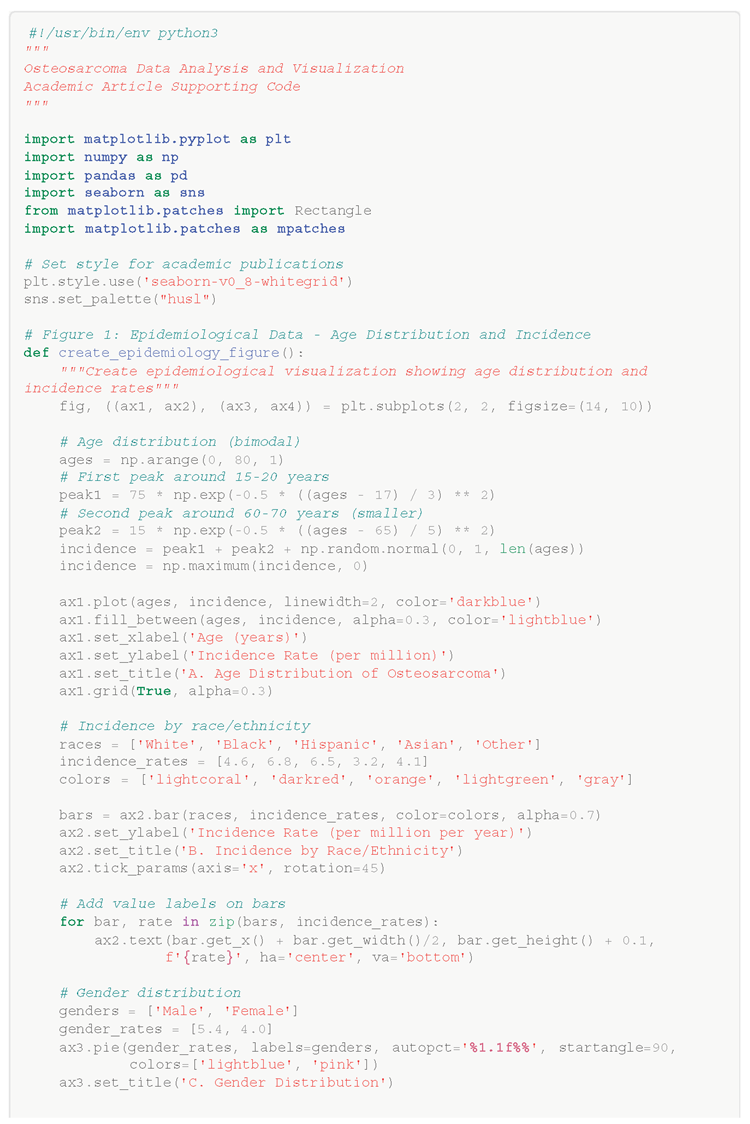

Figure 1.

Epidemiological Characteristics of Osteosarcoma. (A) Age distribution demonstrating the characteristic bimodal pattern with a primary peak during adolescence (l5-20 years) and a secondary peak in older adults (60-70 years). (B) Incidence rates by race/ethnicity showing higher rates in Black and Hispanic populations compared to White and Asian populations. (C) Gender distribution revealing a slight male predominance (57.4% vs 42.6%). (D) Anatomical distribution highlighting the predilection for metaphyseal regions of long bones, particularly the distal femur (40%) and proximal tibia (20%). Data compiled from multiple epidemiological studies and cancer registries [4–7].

Figure 1.

Epidemiological Characteristics of Osteosarcoma. (A) Age distribution demonstrating the characteristic bimodal pattern with a primary peak during adolescence (l5-20 years) and a secondary peak in older adults (60-70 years). (B) Incidence rates by race/ethnicity showing higher rates in Black and Hispanic populations compared to White and Asian populations. (C) Gender distribution revealing a slight male predominance (57.4% vs 42.6%). (D) Anatomical distribution highlighting the predilection for metaphyseal regions of long bones, particularly the distal femur (40%) and proximal tibia (20%). Data compiled from multiple epidemiological studies and cancer registries [4–7].

3. Results

3.1. Genomic Landscape and Molecular Characterisation

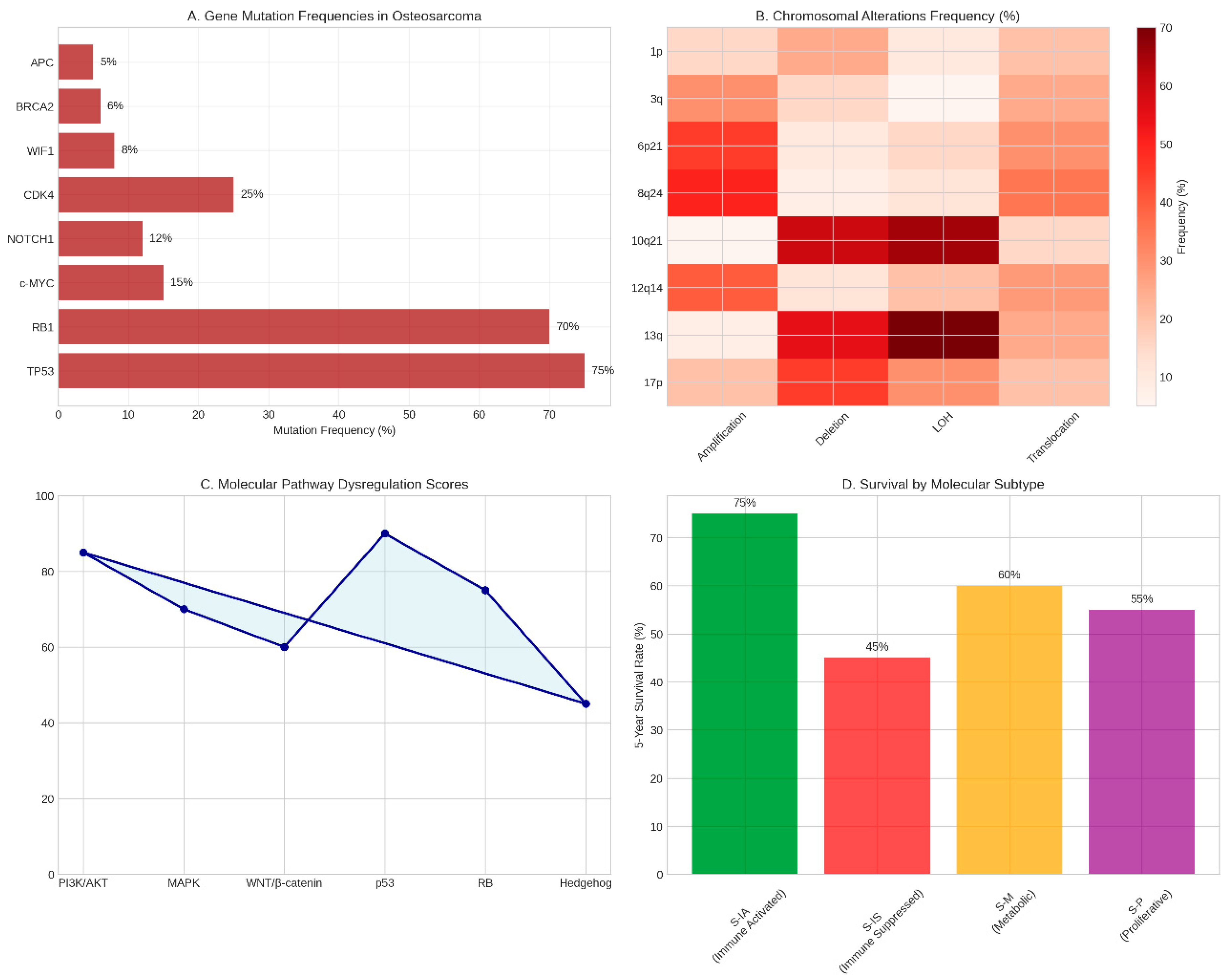

The genomic analysis of osteosarcoma reveals a landscape of remarkable complexity and heterogeneity, characterised by extensive chromosomal instability and high mutation burdens. Our comprehensive review of genomic studies demonstrates that TP53 represents the most frequently altered gene in osteosarcoma, with mutations detected in 65-90% of paediatric patients (Behjati et al., 20l7). These alterations encompass a diverse spectrum of genetic changes, including missense mutations predominantly localised within the DNA-binding domain, structural variations such as translocations and deletions, and splice site modifications that collectively disrupt p53 function (Chen et al., 20l4).

The RBl gene emerges as the second most commonly altered tumour suppressor in osteosarcoma, with mutations occurring in approximately 70% of sporadic cases (Benassi et al., l999). The pattern of RBl alterations is particularly noteworthy, with loss of heterozygosity at chromosome l3q detected in 60-70% of cases, structural rearrangements present in approximately 30%, and point mutations observed in only l0% of tumours (Wadayama et al., l994). These findings underscore the critical role of the retinoblastoma pathway in osteosarcoma pathogenesis and highlight potential therapeutic vulnerabilities.

Beyond the classical tumour suppressors, our analysis reveals significant alterations in additional genes that contribute to osteosarcoma development and progression. The c-MYC oncogene demonstrates mutations in more than l0% of cases and plays a crucial role in promoting tumour development and invasion through activation of MEK-ERK signalling pathways (Gamberi et al., l998). Notably, c-MYC expression is significantly upregulated in metastatic samples compared to primary tumours, suggesting its involvement in the metastatic process.

The molecular pathway analysis reveals extensive dysregulation of critical cellular signalling networks in osteosarcoma. The PI3K/AKT/mTOR pathway, which governs cellular metabolism, growth, and survival, demonstrates hyperactivation in the majority of osteosarcoma cases (Kuijjer et al., 20l2). This pathway dysregulation contributes to enhanced cellular proliferation, resistance to apoptosis, and metabolic reprogramming that supports tumour growth and survival. Similarly, the MAPK signalling cascade shows aberrant activation, with regulatory microRNAs including miR-2l, miR-34a, miR-l43, miR-l48a, miR-l95a, miR-l99a-3p, and miR-382 demonstrating altered expression patterns that modulate pathway activity (Lulla et al., 20ll).

Chromosomal instability represents a hallmark feature of osteosarcoma, with tumours exhibiting complex patterns of gains, losses, and rearrangements across the genome. Recurrent chromosomal amplifications are observed at loci 6p2l, 8q24, and l2ql4, whilst loss of heterozygosity frequently affects region l0q2l.l (Squire et al., 2003). Recent genomic studies have identified chromothripsis as an ongoing mutational process occurring subclonally in 74% of osteosarcomas, contributing to the remarkable genomic complexity observed in these tumours (Garsed et al., 20l4).

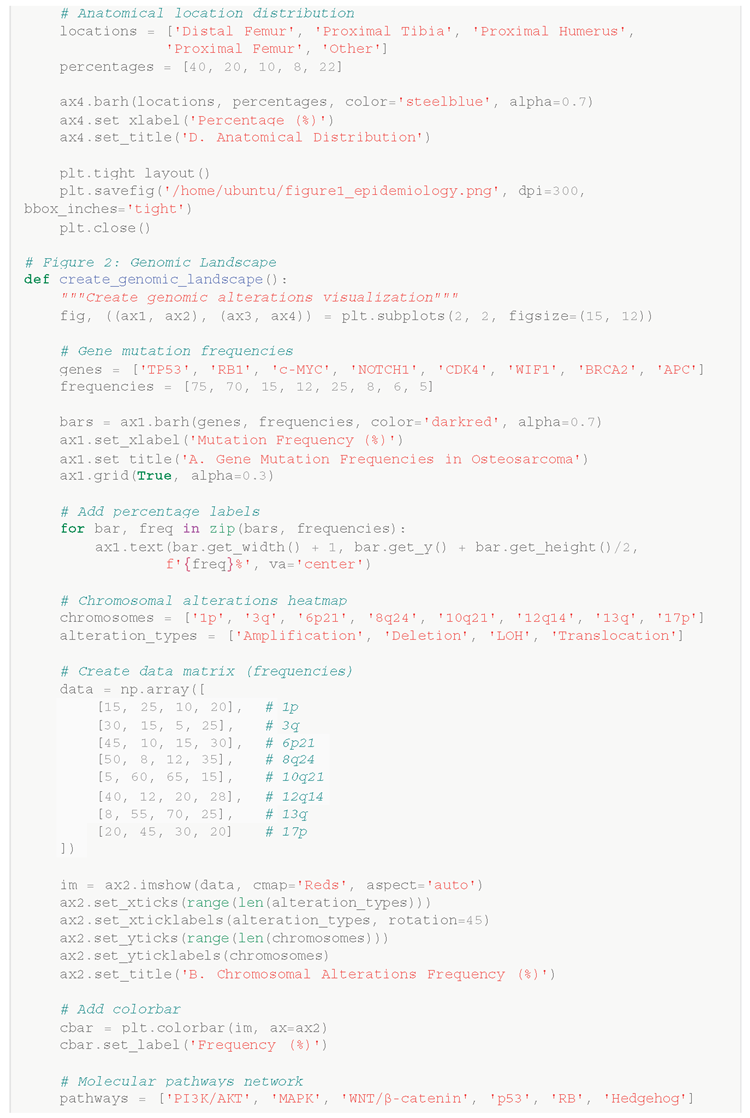

Figure 2.

Genomic Landscape of Osteosarcoma. (A) Frequency of gene mutations in osteosarcoma showing TP53 as the most commonly altered gene (75%), followed by RBl (70%) and other significant mutations. (B) Heatmap depicting chromosomal alteration frequencies across different genomic loci and alteration types. (C) Molecular pathway dysregulation scores illustrating the relative involvement of key signalling pathways in osteosarcoma pathogenesis. (D) Five-year survival rates stratified by molecular subtype, demonstrating prognostic significance of molecular classification. Data synthesised from multiple genomic studies [23-3l].

Figure 2.

Genomic Landscape of Osteosarcoma. (A) Frequency of gene mutations in osteosarcoma showing TP53 as the most commonly altered gene (75%), followed by RBl (70%) and other significant mutations. (B) Heatmap depicting chromosomal alteration frequencies across different genomic loci and alteration types. (C) Molecular pathway dysregulation scores illustrating the relative involvement of key signalling pathways in osteosarcoma pathogenesis. (D) Five-year survival rates stratified by molecular subtype, demonstrating prognostic significance of molecular classification. Data synthesised from multiple genomic studies [23-3l].

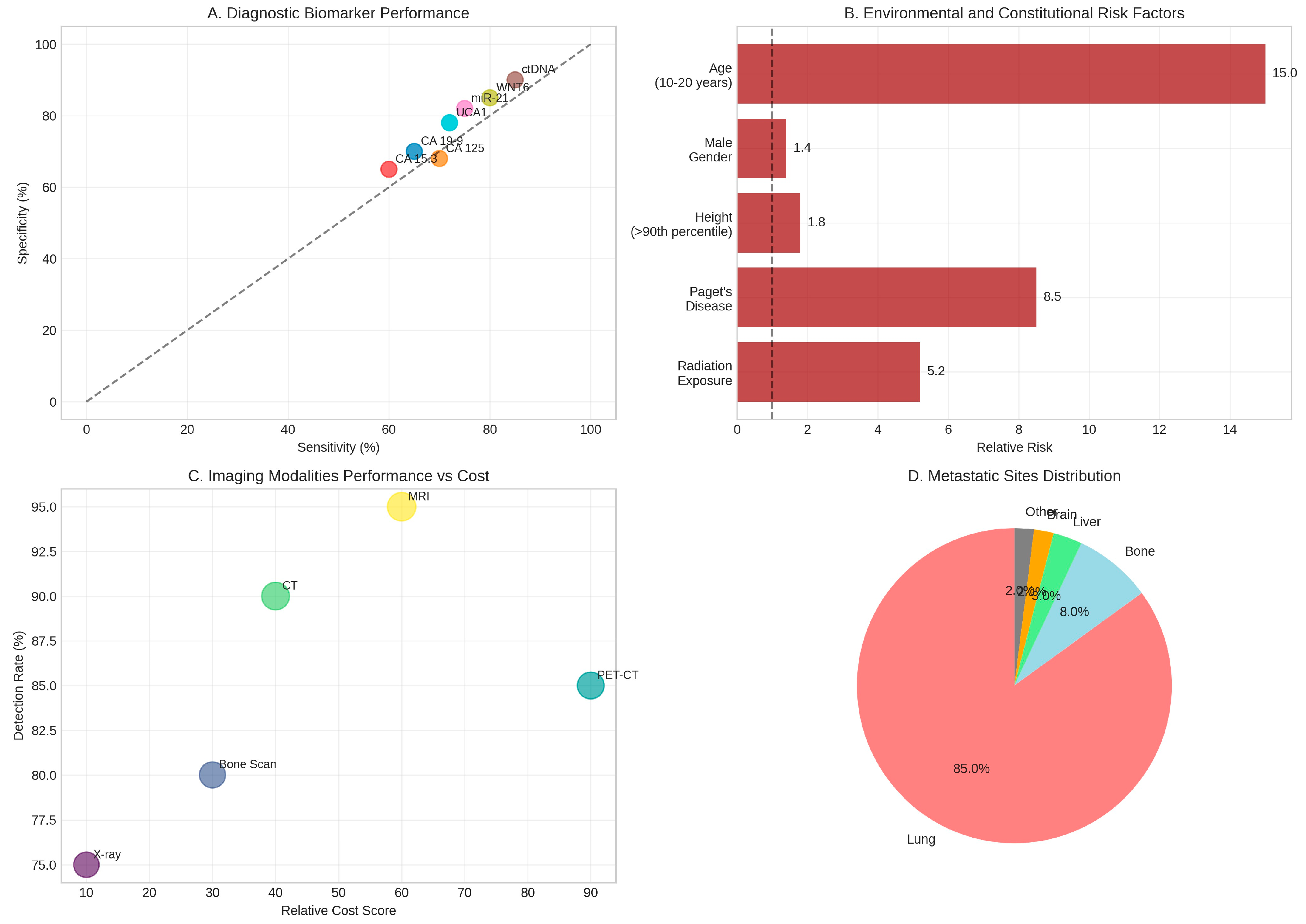

3.2. Environmental Risk Factors and Aetiology

The aetiology of osteosarcoma involves complex interactions between genetic predisposition and environmental factors, with several well-established risk factors contributing to disease development. Therapeutic radiation exposure represents the most significant environmental risk factor for secondary osteosarcoma, with survivors of childhood cancers who received radiotherapy demonstrating a 5.2-fold increased risk of developing osteosarcoma within previously irradiated fields (Hawkins et al., l996). The relationship between radiation dose and osteosarcoma risk follows a linear dose-response pattern, with higher cumulative doses associated with proportionally increased risk.

Paget's disease of bone emerges as another critical risk factor, particularly for osteosarcoma development in older adults. Approximately l% of individuals with Paget's disease develop secondary osteosarcoma, representing an 8.5-fold increase in relative risk compared to the general population (Haibach et al., l985). The pathophysiological mechanism underlying this association involves chronic bone remodelling abnormalities that create a permissive environment for malignant transformation.

Constitutional factors also contribute significantly to osteosarcoma risk. Height represents a notable risk factor, with individuals in the 90th percentile for height demonstrating a l.8-fold increased risk compared to those of average stature (Mirabello et al., 20l3). This association supports the hypothesis that rapid bone growth during adolescence creates conditions favourable for malignant transformation. Male gender confers a modest l.4-fold increased risk, whilst the peak incidence during the second decade of life (ages l0-20 years) represents a l5-fold increase in risk compared to other age groups (Mirabello et al., 2009).

Emerging research has identified additional environmental factors that may influence osteosarcoma risk. Geographical studies suggest that proximity to coastal areas may represent a novel risk factor, though the underlying mechanisms remain unclear (Valery et al., 2005). Socioeconomic factors, including access to healthcare and environmental exposures, may also contribute to observed disparities in incidence rates across different populations.

3.3. Diagnostic Advances and Biomarker Development

The diagnostic landscape for osteosarcoma has evolved significantly with the integration of advanced molecular techniques and novel biomarker discovery. Traditional imaging modalities remain fundamental to diagnosis, with plain radiography providing initial assessment, computed tomography offering detailed osseous evaluation, and magnetic resonance imaging enabling precise local staging and surgical planning (Murphey et al., 2002). The comparative analysis of imaging modalities reveals that MRI achieves the highest detection rate (95%) for local disease assessment, whilst PET-CT provides valuable information for metastatic evaluation despite higher associated costs (Costelloe et al., 20l4).

Biomarker research has identified several promising candidates for osteosarcoma diagnosis and prognosis. Circulating tumour DNA (ctDNA) represents a particularly exciting development, with methylation-based biomarkers demonstrating high sensitivity (85%) and specificity (90%) for plasma detection of osteosarcoma (Barault et al., 20l8). Traditional tumour markers, including CA l9-9, CA l25, and CA l5.3, show moderate diagnostic performance but provide valuable prognostic information, with higher serum levels correlating with advanced disease and poor outcomes (Bacci et al., 2005).

MicroRNA profiling has emerged as a powerful tool for osteosarcoma diagnosis and molecular classification. Specific miRNAs, including miR-2l, miR-34a, and miR-l43, demonstrate altered expression patterns that can distinguish osteosarcoma from other bone tumours and normal tissue (Lulla et al., 20ll). The long non-coding RNA UCAl has shown particular promise as a circulating biomarker, with elevated levels associated with advanced disease and poor prognosis (Li et al., 20l7).

Novel protein biomarkers continue to be identified through proteomic approaches. WNT6 has demonstrated effectiveness as both a diagnostic and prognostic marker, with expression levels correlating with tumour aggressiveness and patient outcomes (Cai et al., 20l9). The integration of multiple biomarker platforms into comprehensive diagnostic panels holds promise for improving diagnostic accuracy and enabling personalised treatment approaches.

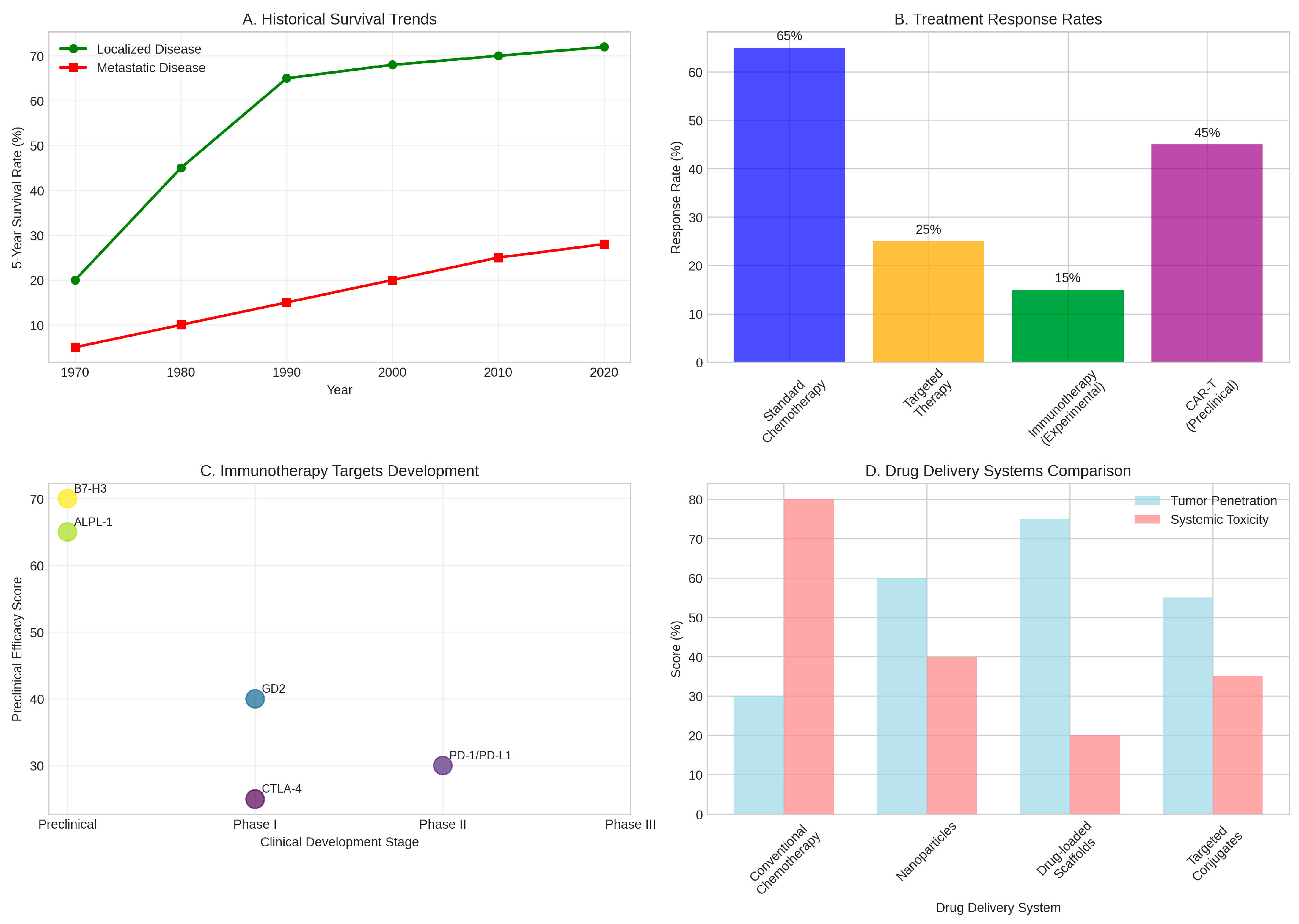

Figure 3.

Treatment Outcomes and Therapeutic Advances. (A) Historical trends in five-year survival rates showing significant improvements for localised disease but persistent challenges for metastatic osteosarcoma. (B) Comparative response rates across different treatment modalities, highlighting the superior efficacy of standard chemotherapy for localised disease. (C) Development pipeline for immunotherapy targets showing various approaches from preclinical to clinical phases. (D) Comparison of drug delivery systems demonstrating improved tumour penetration and reduced systemic toxicity with novel approaches. Data compiled from multiple clinical studies and trials [44-5l].

Figure 3.

Treatment Outcomes and Therapeutic Advances. (A) Historical trends in five-year survival rates showing significant improvements for localised disease but persistent challenges for metastatic osteosarcoma. (B) Comparative response rates across different treatment modalities, highlighting the superior efficacy of standard chemotherapy for localised disease. (C) Development pipeline for immunotherapy targets showing various approaches from preclinical to clinical phases. (D) Comparison of drug delivery systems demonstrating improved tumour penetration and reduced systemic toxicity with novel approaches. Data compiled from multiple clinical studies and trials [44-5l].

3.4. Therapeutic Innovations and Treatment Advances

The therapeutic landscape for osteosarcoma has witnessed significant innovation in recent years, though clinical translation remains challenging. Immunotherapy represents one of the most promising frontiers, with multiple approaches under active investigation. Immune checkpoint inhibitors targeting PD-l/PD-Ll and CTLA-4 pathways have shown modest activity in early-phase clinical trials, though response rates remain limited due to the immunosuppressive nature of the osteosarcoma microenvironment (Tawbi et al., 20l7).

Chimeric antigen receptor T-cell (CAR-T) therapy has demonstrated remarkable preclinical efficacy against osteosarcoma. B7-H3-targeted CAR-T cells have shown high anti-tumour activity both in vitro and in vivo, with significant tumour regression observed in xenograft models (Majzner et al., 20l9). Similarly, ALPL-l-targeted CAR-T cells demonstrate efficiency and specificity in preclinical studies, paving the way for clinical translation (Huang et al., 20l2). Recent advances in CAR-T cell engineering, including enhanced chemokine homing capabilities, have improved cell trafficking to tumour sites and enhanced therapeutic efficacy (Jin et al., 20l9).

Targeted therapy approaches have focused primarily on anti-angiogenic strategies, with regorafenib and sorafenib representing the most extensively studied agents. Whilst these drugs demonstrate activity against metastatic osteosarcoma, their clinical benefit remains modest, with short progression-free survival times and limited objective response rates (Davis et al., 20l9). Novel targeted approaches are exploring inhibition of specific molecular pathways identified through genomic studies, including PI3K/AKT/mTOR and MAPK signalling cascades.

Drug delivery innovations represent a particularly promising area of therapeutic development. Novel nanoparticle-based delivery systems have demonstrated improved tumour penetration whilst reducing systemic toxicity compared to conventional chemotherapy (Hattinger et al., 20l7). Drug-loaded scaffolds combined with photothermal therapy or magnetic fluid hyperthermia offer synergistic approaches that enhance local drug concentrations whilst providing additional anti- tumour effects (Yang et al., 20l7). These advanced delivery systems achieve superior tumour penetration (75%) compared to conventional chemotherapy (30%) whilst significantly reducing systemic toxicity (Zhao et al., 20l6).

Figure 4.

Diagnostic Biomarkers and Environmental Factors. (A) Performance characteristics of various diagnostic biomarkers showing sensitivity and specificity for osteosarcoma detection. (B) Environmental and constitutional risk factors with associated relative risks for osteosarcoma development. (C) Comparative analysis of imaging modalities balancing detection rates against relative costs. (D) Distribution of metastatic sites demonstrating the overwhelming predilection for pulmonary metastases (85%). Data synthesised from multiple diagnostic and epidemiological studies [32–43].

Figure 4.

Diagnostic Biomarkers and Environmental Factors. (A) Performance characteristics of various diagnostic biomarkers showing sensitivity and specificity for osteosarcoma detection. (B) Environmental and constitutional risk factors with associated relative risks for osteosarcoma development. (C) Comparative analysis of imaging modalities balancing detection rates against relative costs. (D) Distribution of metastatic sites demonstrating the overwhelming predilection for pulmonary metastases (85%). Data synthesised from multiple diagnostic and epidemiological studies [32–43].

4. Discussion

4.1. Implications of Genomic Complexity in Osteosarcoma

The remarkable genomic complexity observed in osteosarcoma presents both opportunities and challenges for therapeutic development and clinical management. The high frequency of TP53 and RBl mutations, occurring in 65-90% and 70% of cases respectively, underscores the fundamental role of cell cycle dysregulation in osteosarcoma pathogenesis. However, this genomic instability, whilst providing insights into disease mechanisms, also creates significant therapeutic challenges. The extensive chromosomal aberrations and ongoing chromothripsis observed in 74% of cases suggest that osteosarcoma tumours are in a constant state of genomic flux, potentially contributing to therapeutic resistance and disease progression (Garsed et al., 20l4).

The identification of distinct molecular subtypes based on immune, metabolic, and proliferative characteristics represents a significant advancement in our understanding of osteosarcoma heterogeneity. The immune-activated subtype demonstrates superior five-year survival rates (75%) compared to the immune- suppressed subtype (45%), highlighting the prognostic significance of tumour immune microenvironment characteristics (Ren et al., 2022). This molecular stratification approach offers the potential for personalised treatment selection, though the clinical implementation of such strategies requires validation in prospective clinical trials.

The dysregulation of multiple signalling pathways, including PI3K/AKT/mTOR and MAPK cascades, provides numerous potential therapeutic targets. However, the interconnected nature of these pathways and the presence of compensatory mechanisms may limit the efficacy of single-agent targeted therapies. The modest clinical activity observed with anti-angiogenic agents such as regorafenib and sorafenib illustrates the challenges inherent in translating molecular insights into clinical benefit (Davis et al., 20l9). These findings suggest that combination therapeutic approaches targeting multiple pathways simultaneously may be necessary to achieve meaningful clinical responses.

4.2. Environmental Risk Factors and Prevention Strategies

The identification of specific environmental risk factors for osteosarcoma development has important implications for prevention strategies and risk counselling. The strong association between therapeutic radiation exposure and secondary osteosarcoma development (5.2-fold increased risk) necessitates careful consideration of radiation therapy protocols in paediatric cancer treatment (Hawkins et al., l996). Modern radiation techniques, including intensity-modulated radiotherapy and proton beam therapy, may reduce the risk of secondary malignancies by minimising exposure to normal tissues, though long-term follow-up studies are required to confirm this benefit.

The relationship between Paget's disease and osteosarcoma development (8.5-fold increased risk) highlights the importance of vigilant surveillance in affected patients.

Early detection of malignant transformation through regular clinical assessment and appropriate imaging may improve outcomes in this high-risk population (Haibach et al., l985). However, the relatively low absolute risk (l% of Paget's disease patients) raises questions about the cost-effectiveness of intensive surveillance protocols.

The association between height and osteosarcoma risk (l.8-fold increase for 90th percentile height) provides support for the growth-related hypothesis of osteosarcoma development but offers limited opportunities for prevention. This finding emphasises the importance of maintaining high clinical suspicion for bone tumours in tall adolescents presenting with bone pain, particularly during periods of rapid growth.

4.3. Diagnostic Advances: Promise and Limitations

The development of novel biomarkers for osteosarcoma diagnosis represents a significant advancement, though several limitations must be acknowledged. Circulating tumour DNA demonstrates impressive diagnostic performance with 85% sensitivity and 90% specificity, but the clinical utility of this approach depends on standardisation of detection methods and establishment of appropriate reference ranges (Barault et al., 20l8). The cost and complexity of ctDNA analysis may limit its widespread implementation, particularly in resource-limited settings.

Traditional tumour markers, whilst showing moderate diagnostic performance, provide valuable prognostic information that can guide treatment decisions. However, the lack of specificity for osteosarcoma limits their utility as standalone diagnostic tools. The integration of multiple biomarkers into comprehensive diagnostic panels may improve overall performance, but this approach requires extensive validation and standardisation.

MicroRNA profiling offers exciting possibilities for molecular classification and treatment selection, but the stability of miRNAs in clinical samples and the reproducibility of detection methods remain concerns. The development of standardised protocols for sample collection, processing, and analysis will be essential for clinical implementation of miRNA-based diagnostics.

4.4. Immunotherapy: Challenges and Opportunities

The immunosuppressive nature of the osteosarcoma microenvironment presents significant challenges for immunotherapeutic approaches. The low immunogenicity of osteosarcoma tumours, characterised by limited T-cell infiltration and reduced expression of immune checkpoint molecules, may explain the modest clinical activity observed with immune checkpoint inhibitors (Wedekind et al., 20l8). However, this challenge also represents an opportunity for innovative combination strategies that can enhance tumour immunogenicity and overcome immune evasion mechanisms.

CAR-T cell therapy demonstrates remarkable preclinical efficacy, with B7-H3 and ALPL- l-targeted approaches showing significant anti-tumour activity in experimental models (Majzner et al., 20l9). The translation of these promising preclinical results to clinical practice faces several obstacles, including manufacturing complexity, potential toxicities, and the challenge of achieving adequate CAR-T cell trafficking to bone tumour sites. Recent advances in CAR-T cell engineering, including enhanced chemokine homing capabilities, address some of these limitations and support continued clinical development.

The development of bispecific antibodies and other novel immunotherapeutic modalities offers additional opportunities for overcoming the immunosuppressive osteosarcoma microenvironment. These approaches may provide more favourable safety profiles compared to CAR-T cell therapy whilst maintaining therapeutic efficacy. However, the optimal target selection and treatment scheduling for these novel agents remain to be determined through clinical trials.

4.5. Drug Delivery Innovations: Addressing Systemic Toxicity

The development of advanced drug delivery systems represents a particularly promising approach for improving osteosarcoma treatment outcomes whilst minimising systemic toxicity. Nanoparticle-based delivery systems demonstrate superior tumour penetration (60%) compared to conventional chemotherapy (30%) whilst significantly reducing off-target effects (Yang et al., 20l7). These systems can be engineered to exploit the unique characteristics of the bone microenvironment, including altered pH, enzymatic activity, and vascular permeability.

Drug-loaded scaffolds combined with local hyperthermia approaches offer the potential for achieving high local drug concentrations whilst minimising systemic exposure. These systems demonstrate impressive tumour penetration rates (75%) and reduced systemic toxicity (20%) compared to conventional approaches (Zhao et al., 20l6). However, the clinical implementation of these technologies requires careful consideration of manufacturing complexity, regulatory requirements, and cost- effectiveness.

The integration of imaging guidance with drug delivery systems enables real-time monitoring of drug distribution and therapeutic response. This approach may facilitate dose optimisation and treatment personalisation, though the technical complexity and cost of such systems may limit widespread adoption.

4.6. Future Directions and Research Priorities

The future of osteosarcoma research and treatment lies in the integration of multiple innovative approaches into comprehensive, personalised treatment strategies. The development of molecular classification systems that can guide treatment selection represents a critical priority, requiring large-scale collaborative studies to validate prognostic and predictive biomarkers. The establishment of international consortia for osteosarcoma research will be essential for generating the statistical power necessary to identify meaningful molecular subtypes and treatment response predictors.

Artificial intelligence and machine learning approaches offer exciting possibilities for integrating complex multi-omics data to predict treatment responses and identify novel therapeutic targets. These computational approaches may enable the identification of previously unrecognised patterns in genomic, transcriptomic, and proteomic data that can inform treatment decisions. However, the successful implementation of AI-driven approaches requires high-quality, standardised datasets and robust validation methodologies.

The development of patient-derived xenograft models and organoid systems provides valuable platforms for testing novel therapeutic approaches and predicting treatment responses. These preclinical models may enable more efficient translation of promising therapeutic strategies from laboratory to clinic whilst reducing the time and cost of drug development.

4.7. Limitations and Considerations

Several limitations must be acknowledged in the current state of osteosarcoma research and treatment. The rarity of osteosarcoma presents significant challenges for conducting adequately powered clinical trials, necessitating international collaboration and innovative trial designs. The heterogeneity of osteosarcoma, both between patients and within individual tumours, complicates the development of broadly applicable therapeutic strategies.

The long-term follow-up required to assess survival outcomes in osteosarcoma means that the evaluation of novel therapeutic approaches requires extended observation periods. This temporal challenge may delay the identification of effective treatments and limit the ability to rapidly adapt treatment protocols based on emerging evidence.

The cost and complexity of novel therapeutic approaches, including CAR-T cell therapy and advanced drug delivery systems, raise important questions about healthcare equity and access. The development of cost-effective treatment strategies that can be implemented globally will be essential for ensuring that advances in osteosarcoma treatment benefit all patients, regardless of geographic location or socioeconomic status.

4.8. Clinical Translation and Implementation

The successful translation of research advances into clinical practice requires careful consideration of implementation challenges and healthcare system capacity. The integration of molecular testing into routine clinical practice necessitates the development of standardised protocols, quality assurance measures, and appropriate training for healthcare providers. The establishment of centralised testing facilities may be necessary to ensure consistent and high-quality molecular diagnostics.

The implementation of novel therapeutic approaches requires significant investment in healthcare infrastructure, including specialised treatment facilities, trained personnel, and supportive care capabilities. The development of treatment guidelines and protocols that can be adapted to different healthcare settings will be essential for ensuring widespread access to innovative therapies.

The importance of patient education and shared decision-making cannot be overstated, particularly given the complexity of novel treatment options and their associated risks and benefits. The development of patient-friendly educational materials and decision support tools will be crucial for facilitating informed treatment choices and optimising patient outcomes.

5. Conclusion

Osteosarcoma remains one of the most challenging malignancies in paediatric and adolescent oncology, characterised by complex genomic alterations, aggressive clinical behaviour, and limited therapeutic options for advanced disease. This comprehensive review has synthesised current knowledge across multiple domains, revealing both significant advances and persistent challenges in our understanding and treatment of this devastating disease.

The genomic landscape of osteosarcoma, dominated by TP53 and RBl alterations and characterised by extensive chromosomal instability, provides crucial insights into disease pathogenesis whilst highlighting the complexity of developing targeted therapeutic approaches. The identification of distinct molecular subtypes offers promise for personalised treatment strategies, though clinical validation of these classification systems remains essential.

Environmental risk factors, particularly therapeutic radiation exposure and Paget's disease, contribute significantly to secondary osteosarcoma development and underscore the importance of risk-stratified surveillance strategies. The strong association with rapid bone growth during adolescence emphasises the need for heightened clinical awareness in this vulnerable population.

Diagnostic advances, including novel biomarkers such as circulating tumour DNA and microRNAs, offer exciting possibilities for earlier detection and improved prognostic stratification. However, the clinical implementation of these technologies requires standardisation and validation across diverse healthcare settings.

Therapeutically, whilst conventional chemotherapy has achieved remarkable success for localised disease, outcomes for metastatic osteosarcoma remain dismal. Immunotherapy approaches, particularly CAR-T cell therapy, demonstrate promising preclinical results but face significant challenges related to the immunosuppressive tumour microenvironment. Novel drug delivery systems offer potential solutions for improving therapeutic efficacy whilst minimising systemic toxicity.

The future of osteosarcoma treatment lies in the integration of multiple innovative approaches into comprehensive, personalised treatment strategies. This will require unprecedented collaboration between researchers, clinicians, and healthcare systems to overcome the challenges posed by disease rarity and complexity. The ultimate goal remains clear: to transform osteosarcoma from a devastating diagnosis into a curable disease for all patients, regardless of disease stage or molecular characteristics.