Submitted:

12 March 2025

Posted:

13 March 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results

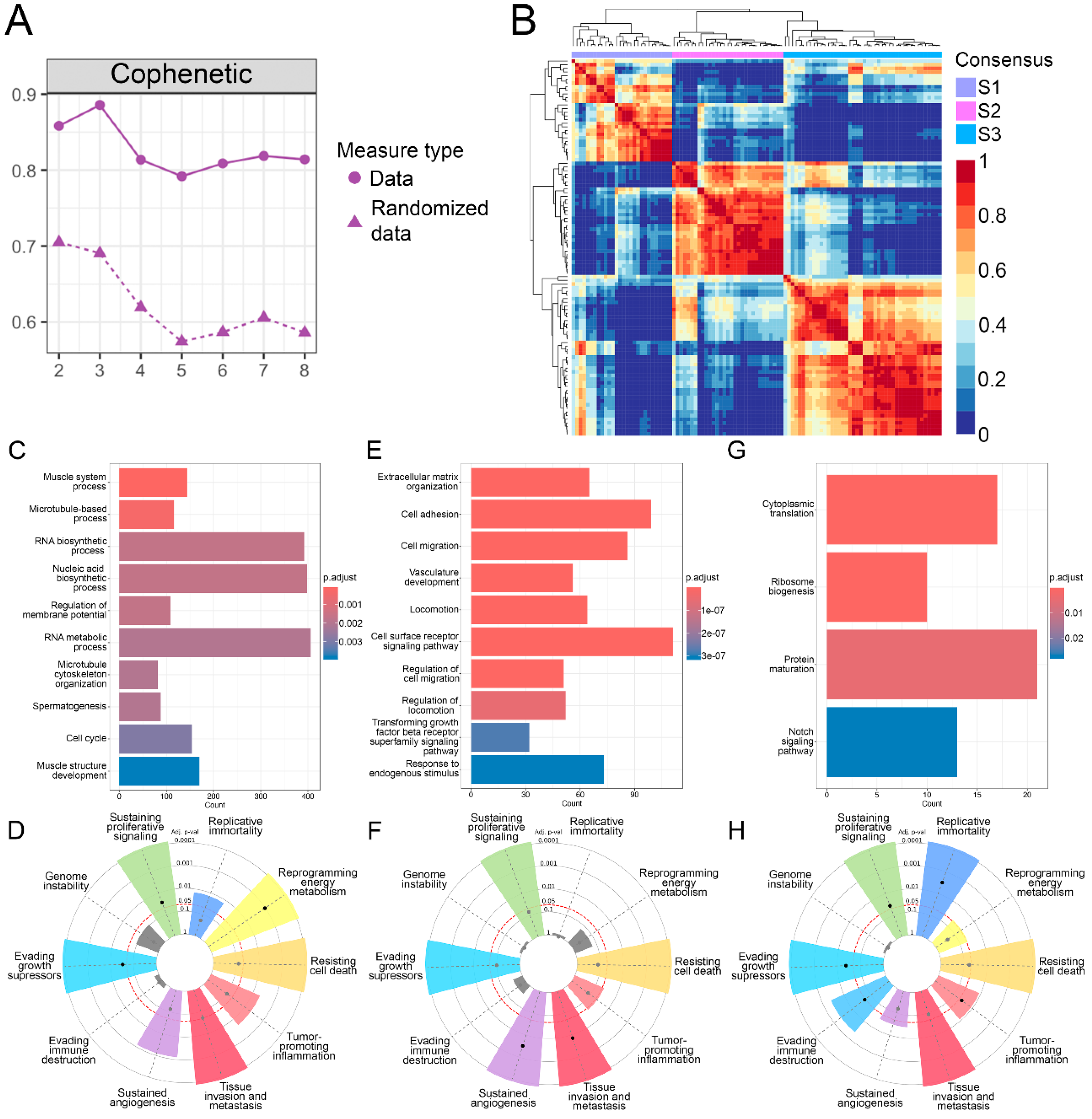

3.1. Identification of Three OS Molecular Subtypes with Distinct Biological and Cancer Hallmark Enrichment Profiles

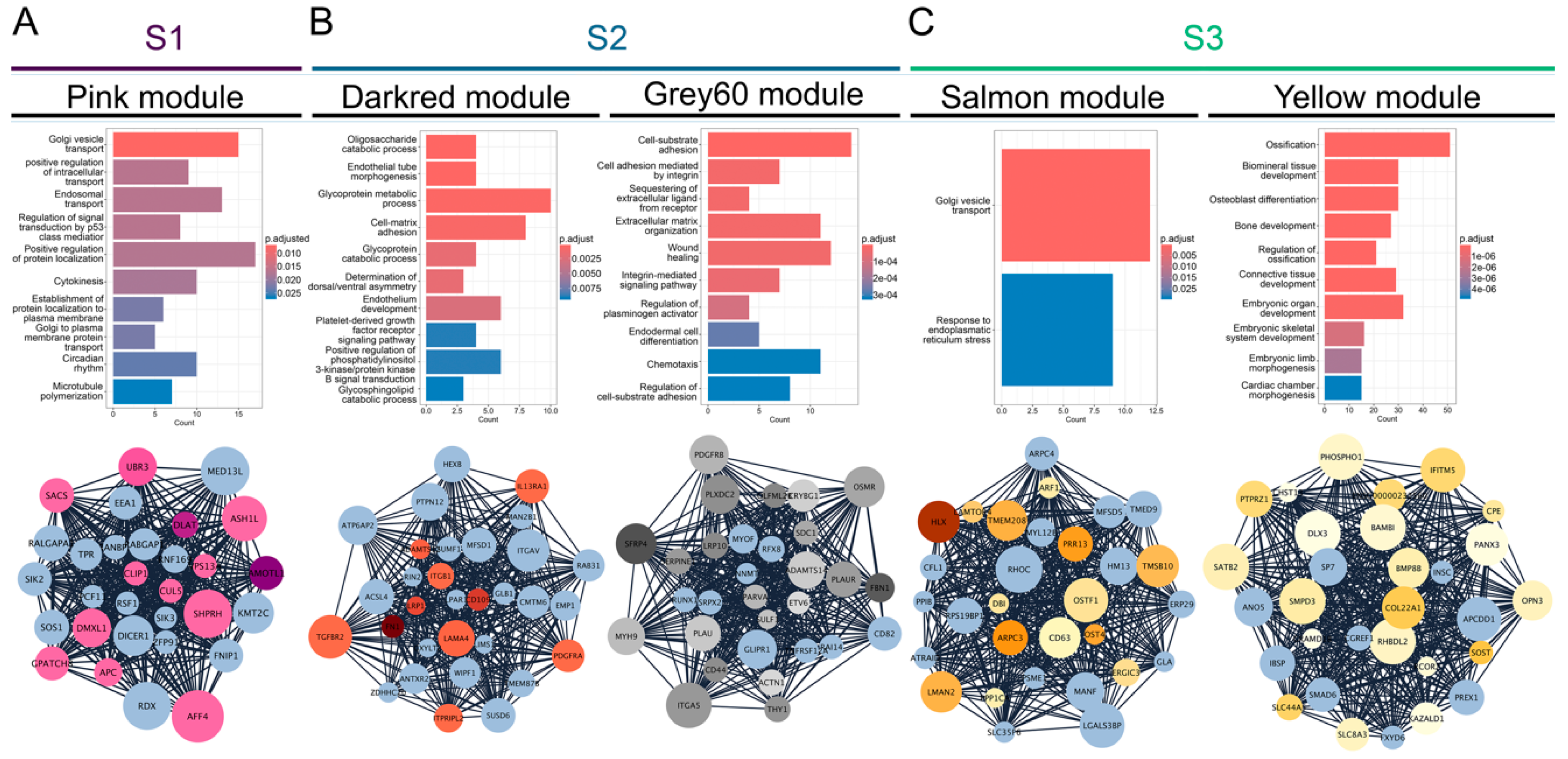

3.2. Gene Co-Expression Networks Reveal Subtype-Specific Functional Enrichment in OS

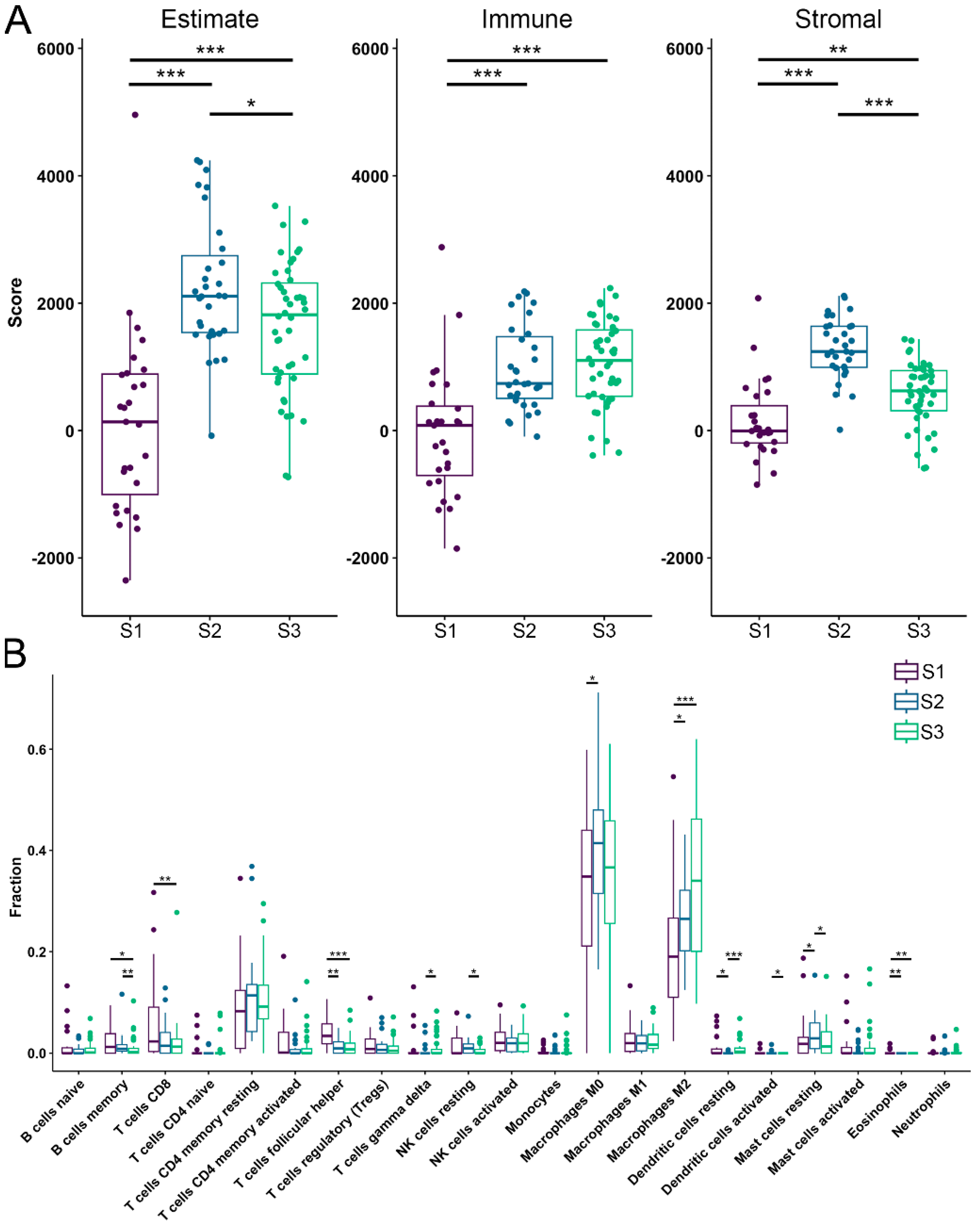

3.3. TME Analysis Reveals Subtype-Specific Immune Infiltration and Prognostic Implications

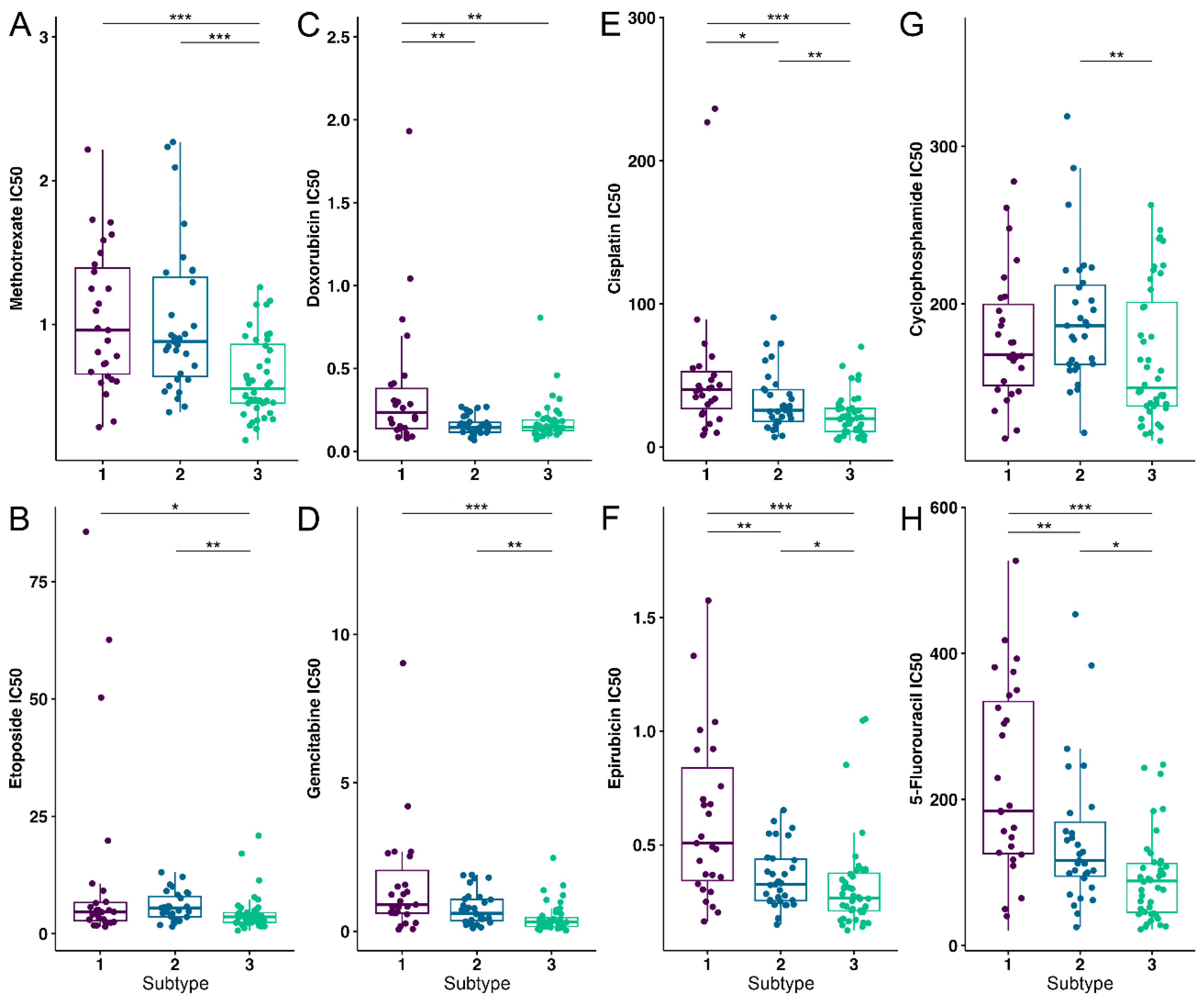

3.4. OS Drug Sensitivity

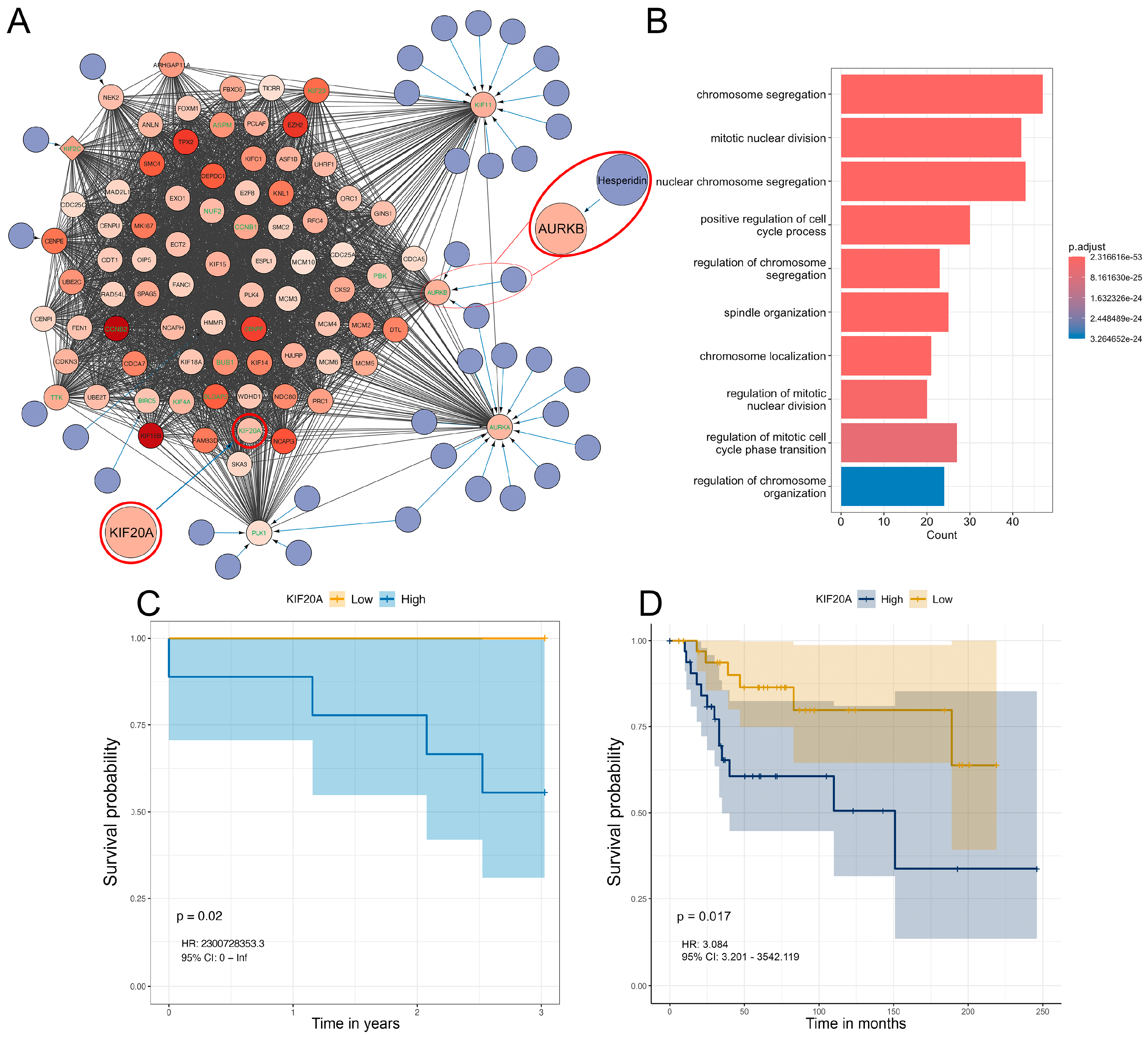

3.5. Differential Gene Expression, Drug Targeting and Functional Enrichment

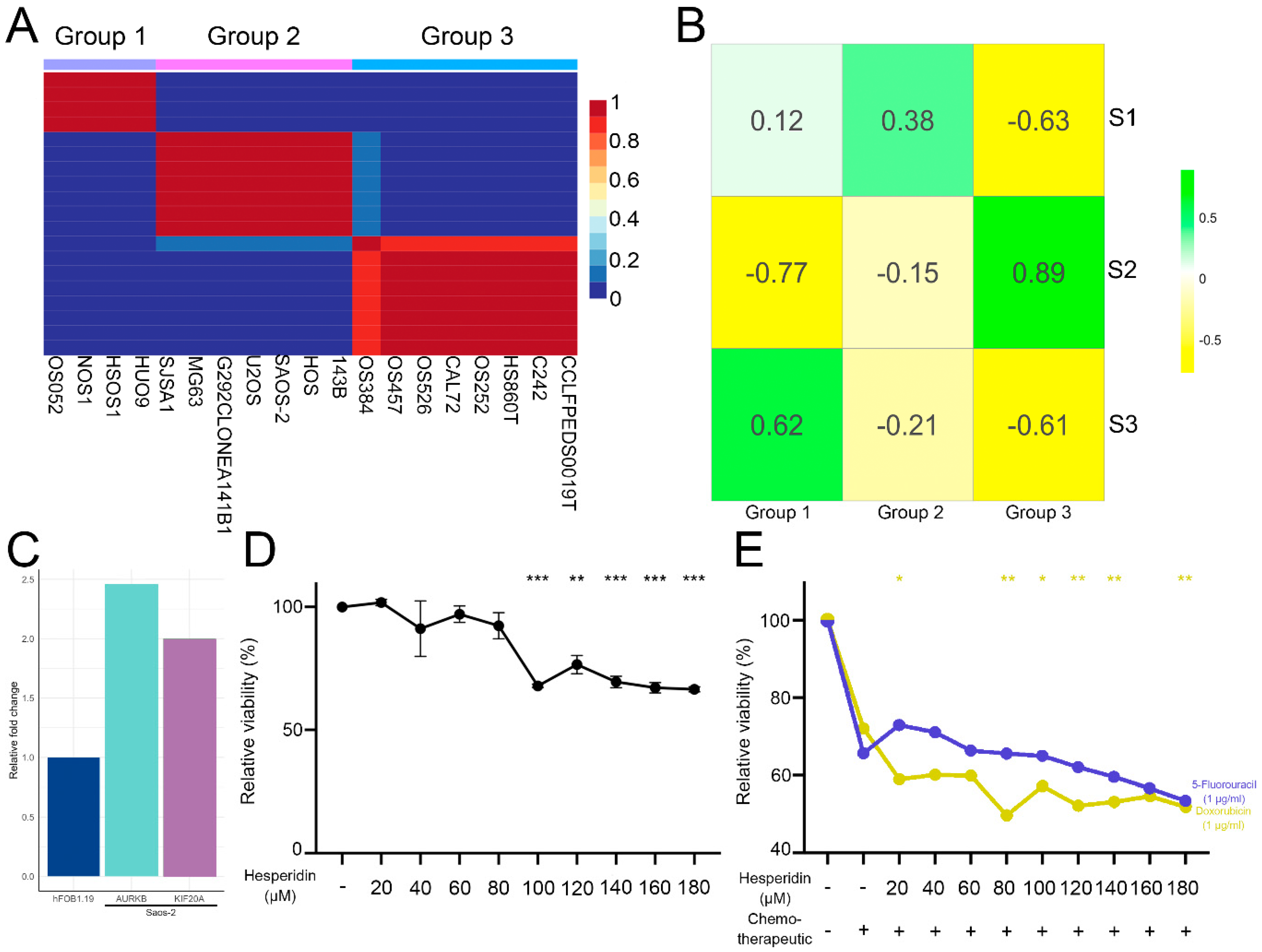

3.6. Analysis of Hesperidins Effect on SAOS-2 Cell Line

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| OS | Osteosarcoma |

| NMF | Non-negative matrix factorization |

| GEO | Gene expression omnibus |

| TCGA | The cancer genome atlas |

| TME | Tumor microenvironment |

| AURKB | Aurora kinase B |

| KIF20A | Kinesin family member 20A |

| WGCNA | Weighted gene co-expression network analysis |

| MAD | Mean absolute deviation |

| PPI | Protein-protein interaction |

| CDI | Coefficient of drug interaction |

References

- NCCR*Explorer: An interactive website for NCCR cancer statistics [Internet]. National Cancer Institute; 2023 Sep 7. [updated: 2023 Sep 8; cited 2024 Aug 8]. Available from: https://nccrexplorer.ccdi.cancer.gov.

- Dharanikota, A.; Arjunan, R.; Dasappa, A. Factors Affecting Prognosis and Survival in Extremity Osteosarcoma. Indian J Surg Oncol 2021, 12, 199–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sayles, L.C.; Breese, M.R.; Koehne, A.L.; Leung, S.G.; Lee, A.G.; Liu, H.Y.; Spillinger, A.; Shah, A.T.; Tanasa, B.; Straessler, K.; et al. Genome-Informed Targeted Therapy for Osteosarcoma. Cancer Discov 2019, 9, 46–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hong, W.; Yuan, H.; Gu, Y.; Liu, M.; Ji, Y.; Huang, Z.; Yang, J.; Ma, L. Immune-related prognosis biomarkers associated with osteosarcoma microenvironment. Cancer Cell Int 2020, 20, 83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, Z.-Y.; Liu, J.-B.; Wang, X.-F.; Ma, Y.-S.; Fu, D. Current Status and Prospects of Clinical Treatment of Osteosarcoma. Technology in Cancer Research & Treatment 2022, 21, 15330338221124696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rathore, R.; Van Tine, B.A. Pathogenesis and Current Treatment of Osteosarcoma: Perspectives for Future Therapies. J Clin Med 2021, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Society, A.C. Chemotherapy and Other Drugs for Osteosarcoma. Availabe online: https://www.cancer.org/cancer/types/osteosarcoma/treating/chemotherapy.html (accessed on 11.02.2025). (accessed on 11.02.2025).

- van den Boogaard, W.M.C.; Komninos, D.S.J.; Vermeij, W.P. Chemotherapy Side-Effects: Not All DNA Damage Is Equal. Cancers (Basel) 2022, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thatishetty, A.V.; Agresti, N.; O'Brien, C.B. Chemotherapy-Induced Hepatotoxicity. Clinics in Liver Disease 2013, 17, 671–686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos, M.L.C.; de Brito, B.B.; da Silva, F.A.F.; Botelho, A.; de Melo, F.F. Nephrotoxicity in cancer treatment: An overview. World J Clin Oncol 2020, 11, 190–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malyszko, J.; Kozlowska, K.; Kozlowski, L.; Malyszko, J. Nephrotoxicity of anticancer treatment. Nephrol Dial Transplant 2017, 32, 924–936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lokich, J.J. Managing Chemotherapy-Induced Bone Marrow Suppression in Cancer. Hospital Practice 1976, 11, 61–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hirotaka, F.; Ryuichi, F.; Hideo, Y.; Tatsuo, Y.; Akira, H.; Masatoshi, K. Anti-Cancer Agent-Induced Nephrotoxicity. Anti-Cancer Agents in Medicinal Chemistry 2014, 14, 921–927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grigorian, A.; O'Brien, C.B. Hepatotoxicity Secondary to Chemotherapy. J Clin Transl Hepatol 2014, 2, 95–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Emadi, A.; Jones, R.J.; Brodsky, R.A. Cyclophosphamide and cancer: golden anniversary. Nature Reviews Clinical Oncology 2009, 6, 638–647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taillibert, S.; Le Rhun, E.; Chamberlain, M.C. Chemotherapy-Related Neurotoxicity. Current Neurology and Neuroscience Reports 2016, 16, 81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Magge, R.S.; DeAngelis, L.M. The double-edged sword: Neurotoxicity of chemotherapy. Blood Reviews 2015, 29, 93–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yeh, E.T.H. Cardiotoxicity Induced by Chemotherapy and Antibody Therapy. Annual Review of Medicine 2006, 57, 485–498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pai, V.B.; Nahata, M.C. Cardiotoxicity of Chemotherapeutic Agents. Drug Safety 2000, 22, 263–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oun, R.; Moussa, Y.E.; Wheate, N.J. The side effects of platinum-based chemotherapy drugs: a review for chemists. Dalton Transactions 2018, 47, 6645–6653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coradini, P.P.; Cigana, L.; Selistre, S.G.A.; Rosito, L.S.; Brunetto, A.L. Ototoxicity From Cisplatin Therapy in Childhood Cancer. Journal of Pediatric Hematology/Oncology 2007, 29, 355–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitchell, E.P. Gastrointestinal Toxicity of Chemotherapeutic Agents. Seminars in Oncology 2006, 33, 106–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boekelheide, K. Mechanisms of Toxic Damage to Spermatogenesis. JNCI Monographs 2005, 2005, 6–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roness, H.; Kashi, O.; Meirow, D. Prevention of chemotherapy-induced ovarian damage. Fertility and Sterility 2016, 105, 20–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van den Boogaard, W.M.C.; Komninos, D.S.J.; Vermeij, W.P. Chemotherapy Side-Effects: Not All DNA Damage Is Equal. Cancers 2022, 14, 627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoeben, A.; Joosten, E.A.J.; van den Beuken-van Everdingen, M.H.J. Personalized Medicine: Recent Progress in Cancer Therapy. Cancers 2021, 13, 242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rothzerg, E.; Xu, J.; Wood, D. Different Subtypes of Osteosarcoma: Histopathological Patterns and Clinical Behaviour. Journal of Molecular Pathology 2023, 4, 99–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Southekal, S.; Shakyawar, S.K.; Bajpai, P.; Elkholy, A.; Manne, U.; Mishra, N.K.; Guda, C. Molecular Subtyping and Survival Analysis of Osteosarcoma Reveals Prognostic Biomarkers and Key Canonical Pathways. Cancers (Basel) 2023, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jiang, Y.; Wang, J.; Sun, M.; Zuo, D.; Wang, H.; Shen, J.; Jiang, W.; Mu, H.; Ma, X.; Yin, F.; et al. Multi-omics analysis identifies osteosarcoma subtypes with distinct prognosis indicating stratified treatment. Nature Communications 2022, 13, 7207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Liu, H.; Wang, L.; Xu, S.; Pi, H.; Cheng, Z. Subtype Classification and Prognosis Signature Construction of Osteosarcoma Based on Cellular Senescence-Related Genes. Journal of Oncology 2022, 2022, 4421952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, X.; Zhang, J.; Liu, J.; Chen, Q.; Cai, C.; Miao, X.; Wu, T.; Cheng, X. Identification of mitochondrial-related signature and molecular subtype for the prognosis of osteosarcoma. Aging (Albany NY) 2023, 15, 12794–12816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Llaneza-Lago, S.; Fraser, W.D.; Green, D. Bayesian unsupervised clustering identifies clinically relevant osteosarcoma subtypes. Briefings in Bioinformatics 2024, 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wan, Y.; Qu, N.; Yang, Y.; Ma, J.; Li, Z.; Zhang, Z. Identification of a 3-gene signature based on differentially expressed invasion genes related to cancer molecular subtypes to predict the prognosis of osteosarcoma patients. Bioengineered 2021, 12, 5916–5931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zheng, K.; Hou, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, F.; Sun, A.; Yang, D. Molecular features and predictive models identify the most lethal subtype and a therapeutic target for osteosarcoma. Front Oncol 2023, 13, 1111570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Team, R.C. R: a language and environment for statistical computing. Availabe online: https://www.R-project.

- Zhang, Y.; Parmigiani, G.; Johnson, W.E. ComBat-seq: batch effect adjustment for RNA-seq count data. NAR Genomics and Bioinformatics 2020, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaujoux, R.; Seoighe, C. A flexible R package for nonnegative matrix factorization. BMC Bioinformatics 2010, 11, 367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoshihara, K.; Shahmoradgoli, M.; Martínez, E.; Vegesna, R.; Kim, H.; Torres-Garcia, W.; Treviño, V.; Shen, H.; Laird, P.W.; Levine, D.A.; et al. Inferring tumour purity and stromal and immune cell admixture from expression data. Nat Commun 2013, 4, 2612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, B.; Khodadoust, M.S.; Liu, C.L.; Newman, A.M.; Alizadeh, A.A. Profiling Tumor Infiltrating Immune Cells with CIBERSORT. Methods Mol Biol 2018, 1711, 243–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maeser, D.; Gruener, R.F.; Huang, R.S. oncoPredict: an R package for predicting in vivo or cancer patient drug response and biomarkers from cell line screening data. Briefings in Bioinformatics 2021, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Therneau, T.M.; Grambsch, P.M. Modeling Survival Data: Extending the Cox Model; Springer New York: 2013.

- Therneau, T.M. A Package for Survival Analysis in R. Availabe online: https://CRAN.R-project.

- Kassambara A, K.M. , Biecek P survminer: Drawing Survival Curves using 'ggplot2'. Availabe online: https://CRAN.R-project.

- Wickham, H. ggplot2: Elegant Graphics for Data Analysis. Availabe online: https://ggplot2.tidyverse.

- Cox, D.R. Regression Models and Life-Tables. Journal of the Royal Statistical Society: Series B (Methodological) 1972, 34, 187–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Menyhart, O.; Kothalawala, W.J.; Győrffy, B. A gene set enrichment analysis for the cancer hallmarks. Journal of Pharmaceutical Analysis 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pingping, B.; Yuhong, Z.; Weiqi, L.; Chunxiao, W.; Chunfang, W.; Yuanjue, S.; Chenping, Z.; Jianru, X.; Jiade, L.; Lin, K.; et al. Incidence and Mortality of Sarcomas in Shanghai, China, During 2002–2014. Frontiers in Oncology 2019, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, S.; Gao, X.; Zhou, K.; Kang, Y.; Ji, L.; Zhong, X.; Lv, J. Exploration of metastasis-related signatures in osteosarcoma based on tumor microenvironment by integrated bioinformatic analysis. Heliyon 2025, 11, e41358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Li, J.; Li, X. Construction and validation of an oxidative-stress-related risk model for predicting the prognosis of osteosarcoma. Aging (Albany NY) 2023, 15, 4820–4843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gu, Z.; Zhou, Y.; Cao, C.; Wang, X.; Wu, L.; Ye, Z. TFAP2C-mediated LINC00922 signaling underpins doxorubicin-resistant osteosarcoma. Biomed Pharmacother 2020, 129, 110363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wippel, B.; Gundle, K.R.; Dang, T.; Paxton, J.; Bubalo, J.; Stork, L.; Fu, R.; Ryan, C.W.; Davis, L.E. Safety and efficacy of high-dose methotrexate for osteosarcoma in adolescents compared with young adults. Cancer Medicine 2019, 8, 111–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, D.; Xu, T.; Fan, L.; Liu, K.; Li, G. microRNA-216b enhances cisplatin-induced apoptosis in osteosarcoma MG63 and SaOS-2 cells by binding to JMJD2C and regulating the HIF1α/HES1 signaling axis. J Exp Clin Cancer Res 2020, 39, 201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, Z.; Jin, G.; Yao, K.; Liu, K.; Liu, F.; Chen, H.; Wang, K.; Gorja, D.R.; Reddy, K.; Bode, A.M.; et al. Aurora B kinase as a novel molecular target for inhibition the growth of osteosarcoma. Mol Carcinog 2019, 58, 1056–1067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, X.; Liu, J.-m.; Song, H.-h.; Yang, Q.-k.; Ying, H.; Tong, W.-l.; Zhou, Y.; Liu, Z.-l. Aurora-B knockdown inhibits osteosarcoma metastasis by inducing autophagy via the mTOR/ULK1 pathway. Cancer Cell International 2020, 20, 575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhong, Y.; Liu, Y.; Tong, W.; Xie, X.; Nie, J.; Yang, F.; Liu, Z.; Liu, J. [High expression of AURKB promotes malignant phenotype of osteosarcoma cells by activating nuclear factor-κB signaling via DHX9]. Nan Fang Yi Ke Da Xue Xue Bao 2024, 44, 2308–2316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- B, D. DepMap 24Q4 Public. (: Availabe online.

- Inc., P. Inc., P. Doxorubicin Clinical Pharmacology. Availabe online: https://www.pfizermedicalinformation.com/doxorubicin/clinical-pharmacology (accessed on 06.02.). (accessed on 06.02.).

- Zheng, J.F.; Wang, H.D. 5-Fluorouracil concentration in blood, liver and tumor tissues and apoptosis of tumor cells after preoperative oral 5'-deoxy-5-fluorouridine in patients with hepatocellular carcinoma. World J Gastroenterol 2005, 11, 3944–3947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foucquier, J.; Guedj, M. Analysis of drug combinations: current methodological landscape. Pharmacol Res Perspect 2015, 3, e00149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, Y.J.; Xu, Y.; Deng, C.; Zhu, X.; Fu, J.; Chen, H.; Lu, J.; Xu, H.; Song, G.; Tang, Q.; et al. Gene Expression Classifier Reveals Prognostic Osteosarcoma Microenvironment Molecular Subtypes. Front Immunol 2021, 12, 623762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, L.; Yan, T.; Guo, W.; Niu, J.; Wang, W.; Ren, T.; Huang, Y.; Xu, J.; Wang, B. Molecular subtypes of osteosarcoma classified by cancer stem cell related genes define immunological cell infiltration and patient survival. Front Immunol 2022, 13, 986785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shu, Y.; Peng, J.; Feng, Z.; Hu, K.; Li, T.; Zhu, P.; Cheng, T.; Hao, L. Osteosarcoma subtypes based on platelet-related genes and tumor microenvironment characteristics. Front Oncol 2022, 12, 941724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pan, R.; Pan, F.; Zeng, Z.; Lei, S.; Yang, Y.; Yang, Y.; Hu, C.; Chen, H.; Tian, X. A novel immune cell signature for predicting osteosarcoma prognosis and guiding therapy. Front Immunol 2022, 13, 1017120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W.B.; Han, F.M.; Liu, L.M.; Jin, H.B.; Yuan, X.Y.; Shang, H.S. Characterizing the critical role of metabolism in osteosarcoma based on establishing novel molecular subtypes. Eur Rev Med Pharmacol Sci 2022, 26, 2926–2943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, Z.; Zhang, L.; Zhong, Y. Characterization of osteosarcoma subtypes mediated by macrophage-related genes and creation and validation of a risk score system to quantitatively assess the prognosis of osteosarcoma and reflect the tumor microenvironment. Ann Transl Med 2022, 10, 1318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, D.; Yang, K.; Chen, X.; Li, Y.; Chen, Y. Analysis of Immune-Stromal Score-Based Gene Signature and Molecular Subtypes in Osteosarcoma: Implications for Prognosis and Tumor Immune Microenvironment. Front Genet 2021, 12, 699385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Liu, J.; Ding, R.; Miao, X.; Deng, J.; Zhao, X.; Wu, T.; Cheng, X. Molecular characterization of Golgi apparatus-related genes indicates prognosis and immune infiltration in osteosarcoma. Aging (Albany NY) 2024, 16, 5249–5263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, W.-Q.; Zou, C.-D.; Wu, D.; Fu, H.-X.; Wang, X.-D.; Yao, F. Construction of molecular subtype model of osteosarcoma based on endoplasmic reticulum stress and tumor metastasis-related genes. Heliyon 2024, 10, e25691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, C.; Sun, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Qin, B.; Lei, T. Construction of Molecular Subtype and Prognosis Prediction Model of Osteosarcoma Based on Aging-Related Genes. J Oncol 2022, 2022, 8177948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, X.; Fu, R. Construction of a 5-gene prognostic signature based on oxidative stress related genes for predicting prognosis in osteosarcoma. PLoS One 2023, 18, e0295364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sneeggen, M.; Guadagno, N.A.; Progida, C. Intracellular Transport in Cancer Metabolic Reprogramming. Frontiers in Cell and Developmental Biology 2020, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pompili, S.; Vetuschi, A.; Sferra, R.; Cappariello, A. Extracellular Vesicles and Resistance to Anticancer Drugs: A Tumor Skeleton Key for Unhinging Chemotherapies. Frontiers in Oncology 2022, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, H.; Wu, Y.; Chen, J.; Hu, X.; Wang, X.; Xu, G. Exosomes and osteosarcoma drug resistance. Front Oncol 2023, 13, 1133726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, Y.; Lin, Y.; Mi, C. Cisplatin-resistant osteosarcoma cell-derived exosomes confer cisplatin resistance to recipient cells in an exosomal circ_103801-dependent manner. Cell Biol Int 2021, 45, 858–868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, C.; Xu, Y.; Fu, J.; Zhu, X.; Chen, H.; Xu, H.; Wang, G.; Song, Y.; Song, G.; Lu, J.; et al. Reprograming the tumor immunologic microenvironment using neoadjuvant chemotherapy in osteosarcoma. Cancer Sci 2020, 111, 1899–1909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, X.; Zhang, W.; Xu, P. NK cell and macrophages confer prognosis and reflect immune status in osteosarcoma. J Cell Biochem 2019, 120, 8792–8797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gutiérrez-Melo, N.; Baumjohann, D. T follicular helper cells in cancer. Trends in Cancer 2023, 9, 309–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, J.; Kang, X.; Wang, Z.; Zhao, G.; Jiang, B. The activity level of follicular helper T cells in the peripheral blood of osteosarcoma patients is associated with poor prognosis. Bioengineered 2022, 13, 3751–3759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, Z.; Peng, F.; Zhang, C.; Tao, S.; Xu, D.; Zhu, Z. Expression, regulating mechanism and therapeutic target of KIF20A in multiple cancer. Heliyon 2023, 9, e13195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Z.; Jin, Z.; Zhang, H.; Zhang, M.; Sun, D. Knockdown of <i>Kif20a</i> inhibits growth of tumors in soft tissue sarcoma <i>in vitro</i> and <i>in vivo</i>. Journal of Cancer 2020, 11, 5088–5098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, J.; Bai, Y.; Zhang, H.; Chen, T.; Shang, G. Single-cell RNA sequencing reveals the communications between tumor microenvironment components and tumor metastasis in osteosarcoma. Frontiers in Immunology 2024, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Groth-Pedersen, L.; Aits, S.; Corcelle-Termeau, E.; Petersen, N.H.T.; Nylandsted, J.; Jäättelä, M. Identification of Cytoskeleton-Associated Proteins Essential for Lysosomal Stability and Survival of Human Cancer Cells. PLOS ONE 2012, 7, e45381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shi, Y.; Yue, X.; Luo, Q. Metabolic reprogramming in osteosarcoma. Pediatric Discovery 2023, 1, e18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ducat, D.; Zheng, Y. Aurora kinases in spindle assembly and chromosome segregation. Exp Cell Res 2004, 301, 60–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Li, D.; Liu, Z.; Zhou, K.; Li, W.; Yang, Y.; Sun, R.; Li, Y. AURKB affects the proliferation of clear cell renal cell carcinoma by regulating fatty acid metabolism. Discover Oncology 2025, 16, 91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aggarwal, V.; Tuli, H.S.; Thakral, F.; Singhal, P.; Aggarwal, D.; Srivastava, S.; Pandey, A.; Sak, K.; Varol, M.; Khan, M.A.; et al. Molecular mechanisms of action of hesperidin in cancer: Recent trends and advancements. Exp Biol Med (Maywood) 2020, 245, 486–497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahmani, A.H.; Babiker, A.Y.; Anwar, S. Hesperidin, a Bioflavonoid in Cancer Therapy: A Review for a Mechanism of Action through the Modulation of Cell Signaling Pathways. Molecules 2023, 28, 5152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shakiba, E.; Bazi, A.; Ghasemi, H.; Eshaghi-Gorji, R.; Mehdipour, S.A.; Nikfar, B.; Rashidi, M.; Mirzaei, S. Hesperidin suppressed metastasis, angiogenesis and tumour growth in Balb/c mice model of breast cancer. J Cell Mol Med 2023, 27, 2756–2769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kong, W.; Ling, X.; Chen, Y.; Wu, X.; Zhao, Z.; Wang, W.; Wang, S.; Lai, G.; Yu, Z. Hesperetin reverses P-glycoprotein-mediated cisplatin resistance in DDP-resistant human lung cancer cells via modulation of the nuclear factor-κB signaling pathway. Int J Mol Med 2020, 45, 1213–1224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coutinho, L.; Oliveira, H.; Pacheco, A.R.; Almeida, L.; Pimentel, F.; Santos, C.; Ferreira de Oliveira, J.M.P. Hesperetin-etoposide combinations induce cytotoxicity in U2OS cells: Implications on therapeutic developments for osteosarcoma. DNA Repair 2017, 50, 36–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, S.; Li, Z.; Liu, W.; Wei, G.; Yu, N.; Ji, G. Neohesperidin Induces Cell Cycle Arrest, Apoptosis, and Autophagy via the ROS/JNK Signaling Pathway in Human Osteosarcoma Cells. The American Journal of Chinese Medicine 2021, 49, 1251–1274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).