Submitted:

07 July 2025

Posted:

09 July 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

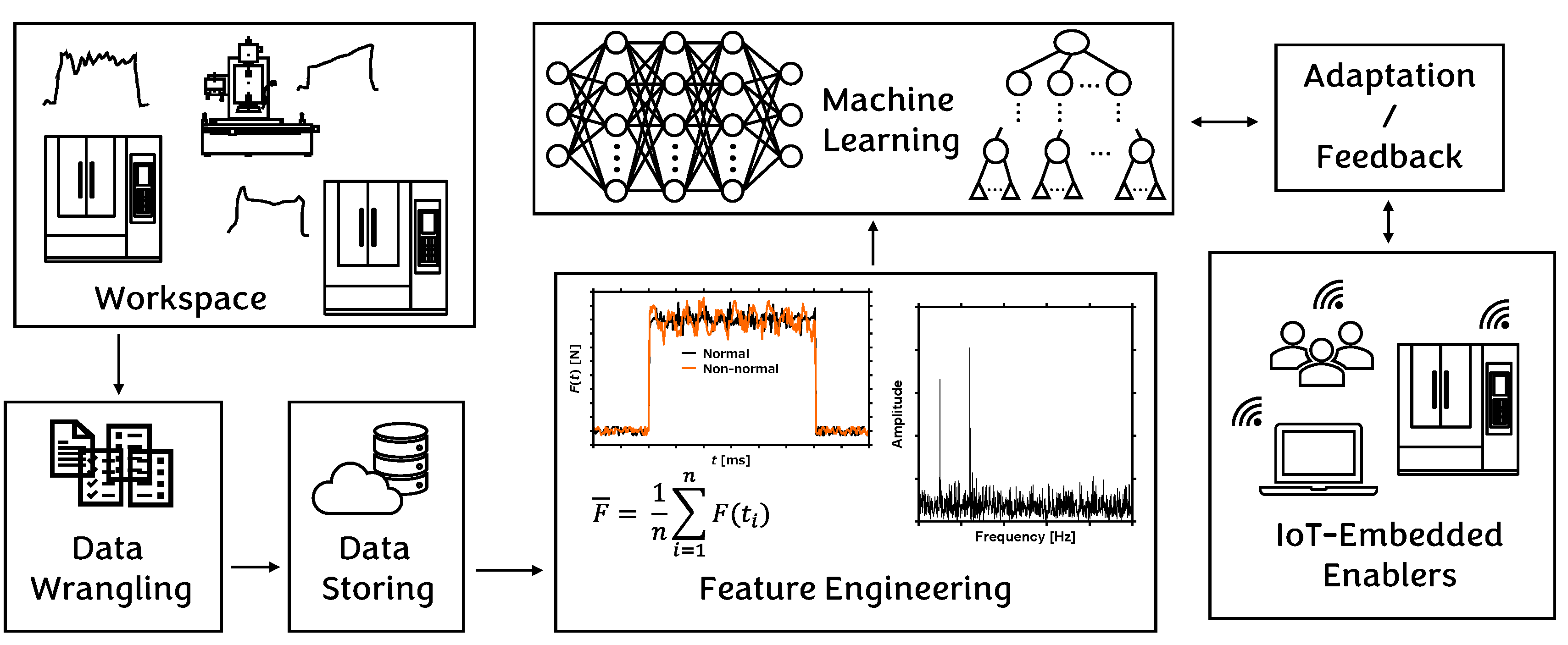

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

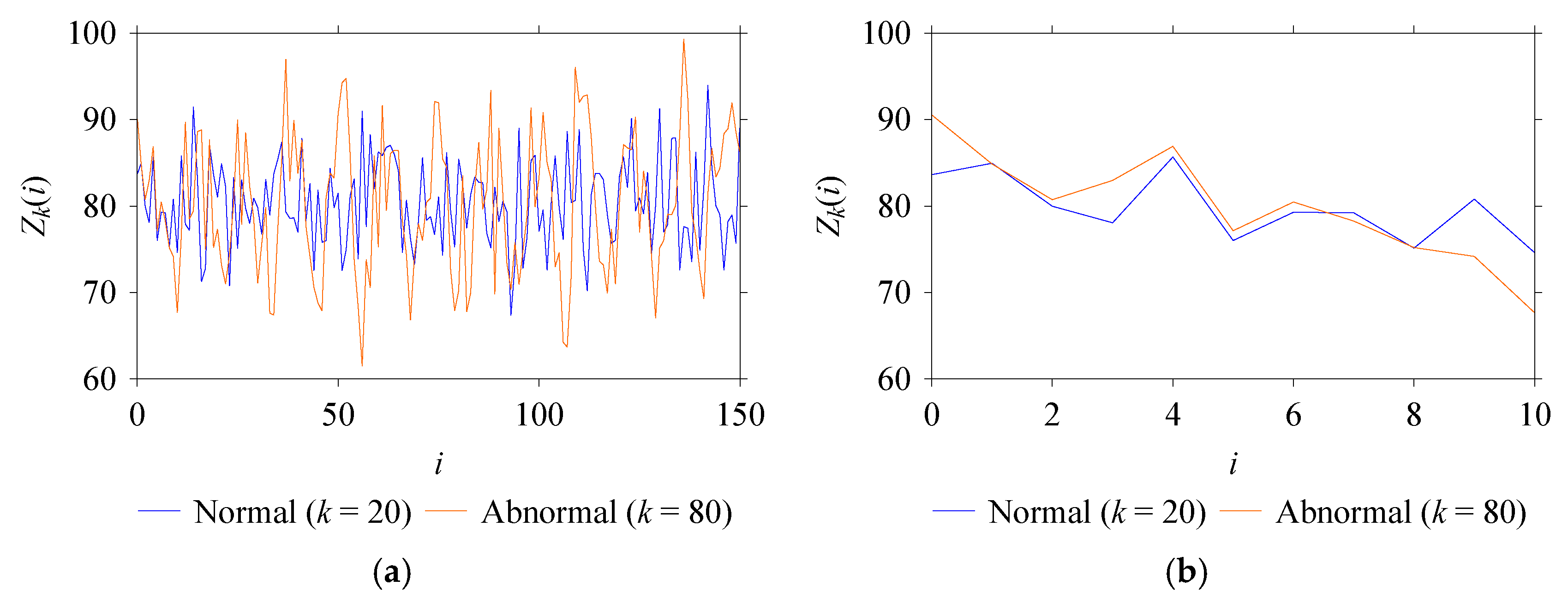

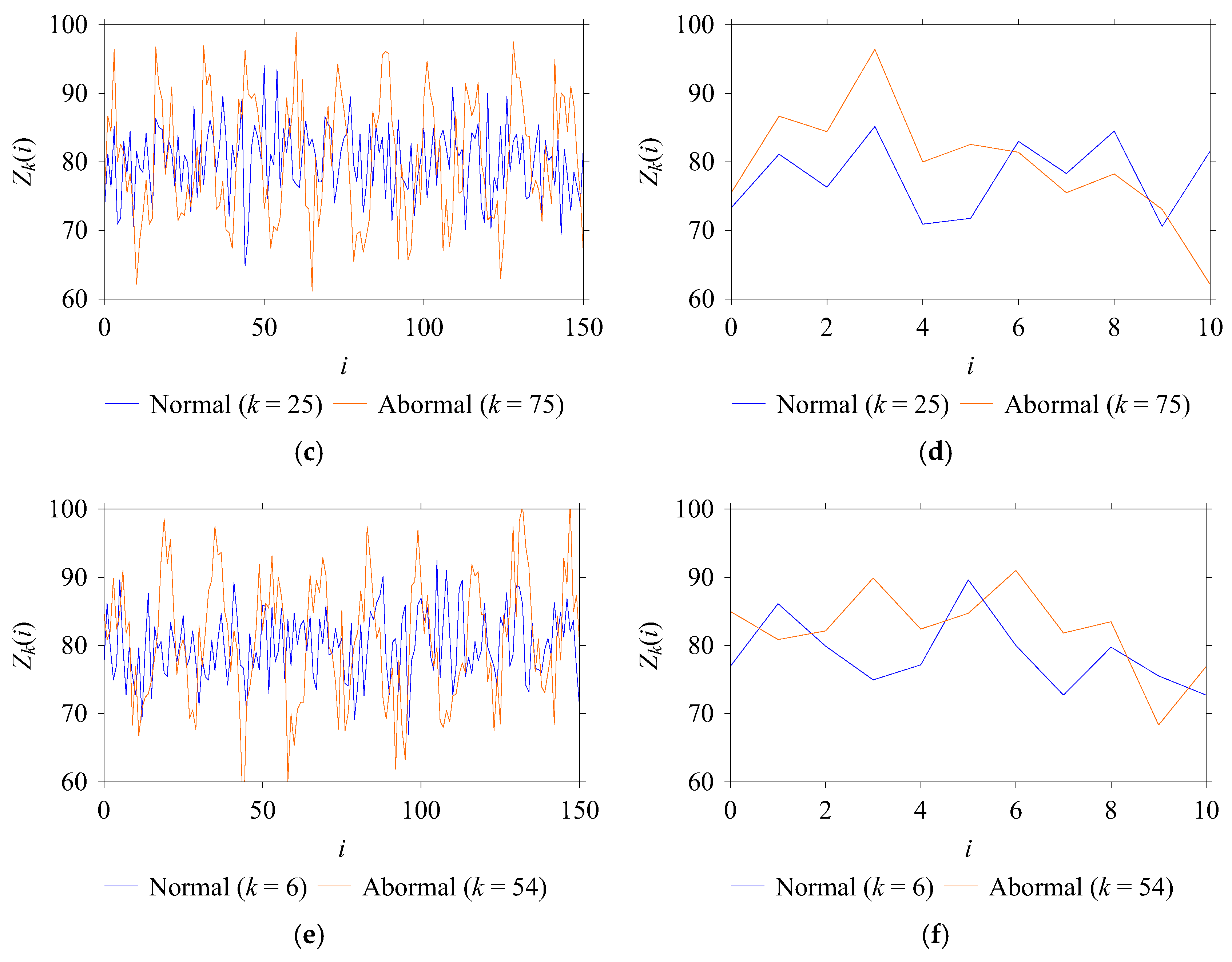

2.1. Studies Related to Analyzing the Role of Window Size

2.2. Studies Related to Using Long Window-Driven Data

3. Data Preparation

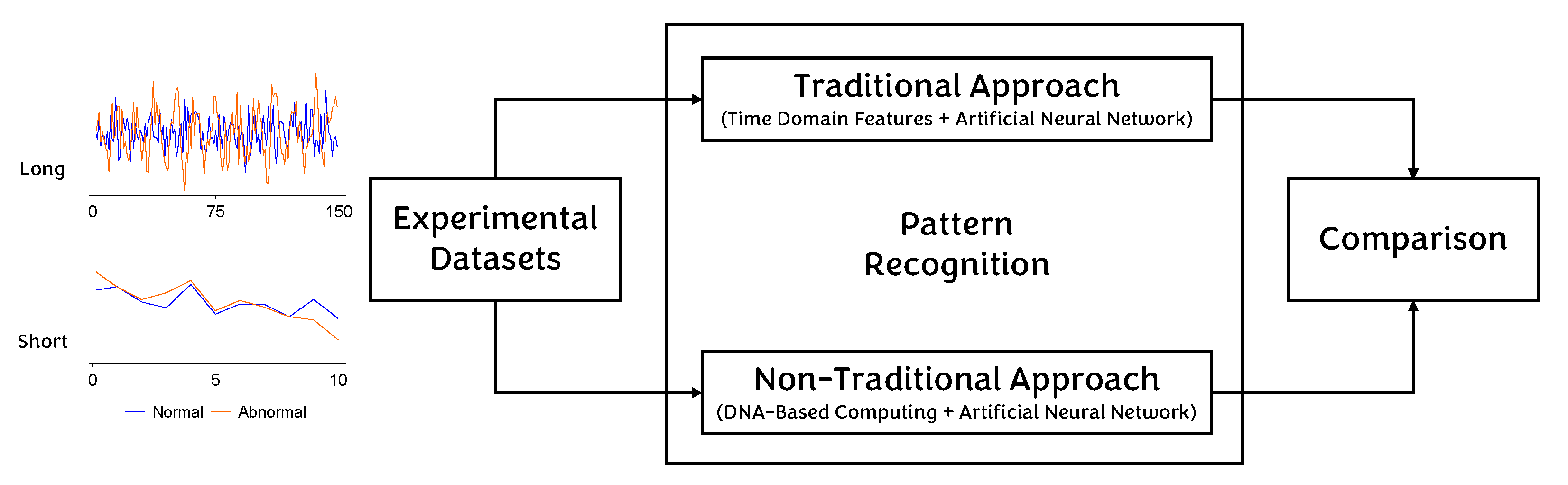

4. Methodology

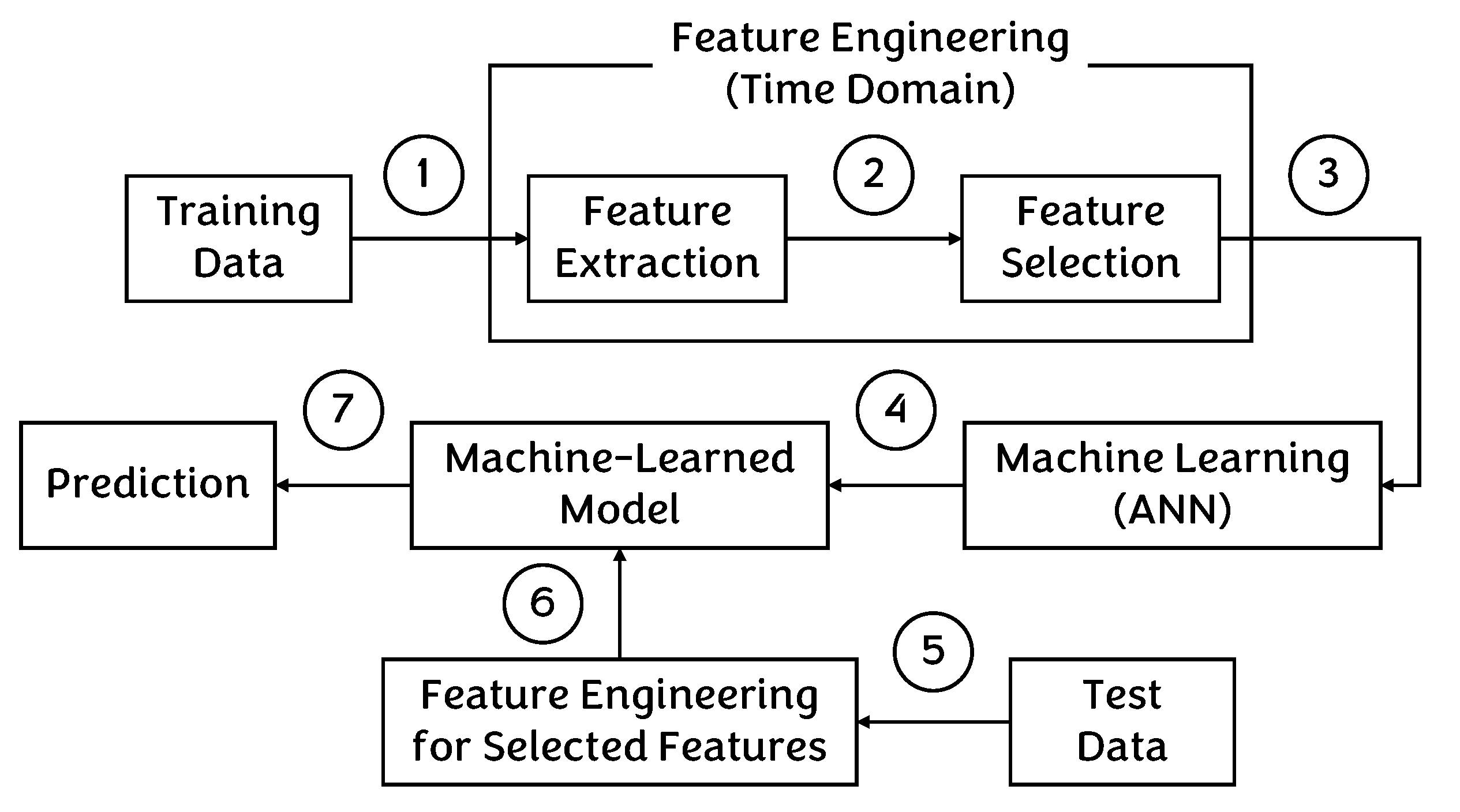

4.1. Traditional Approach

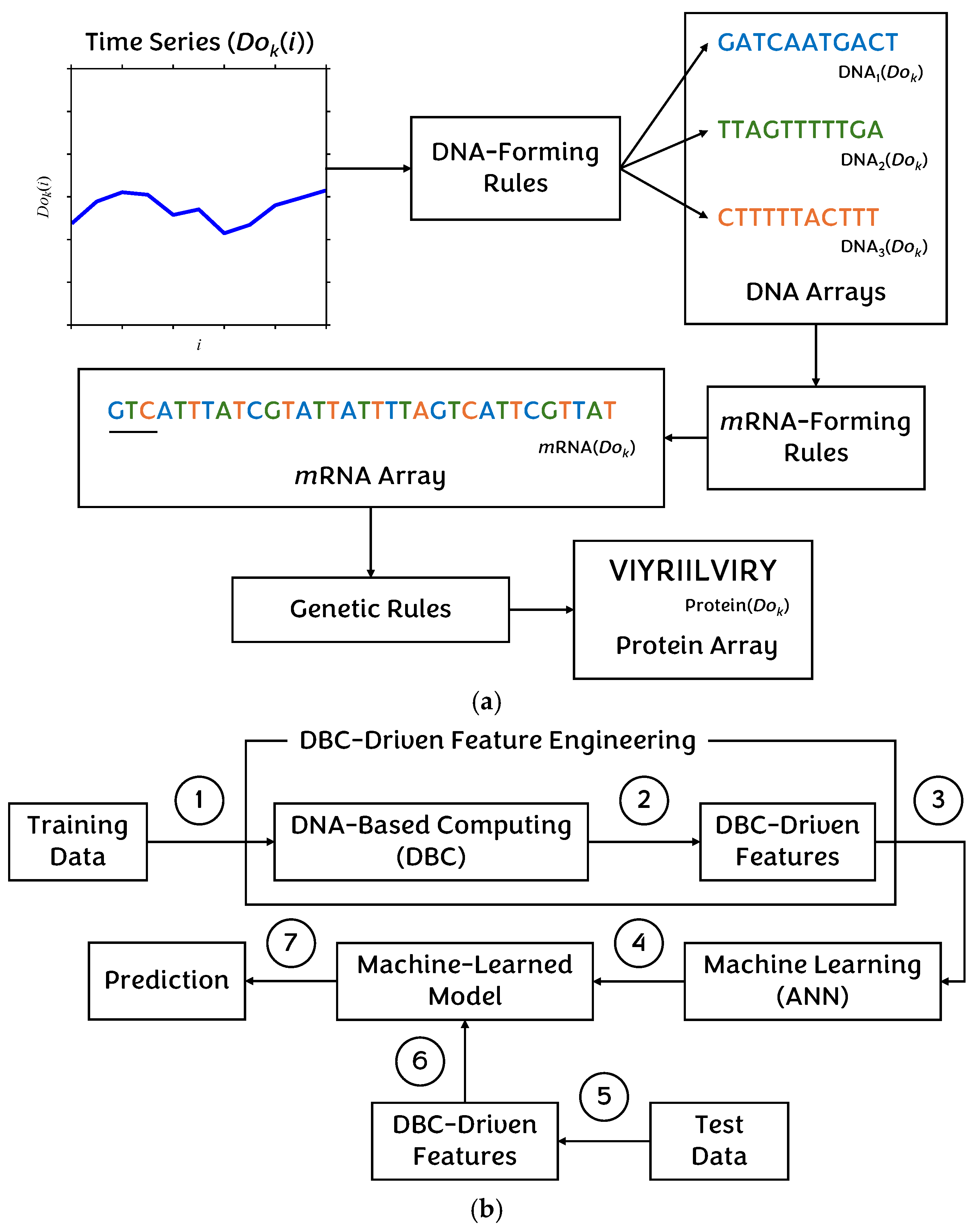

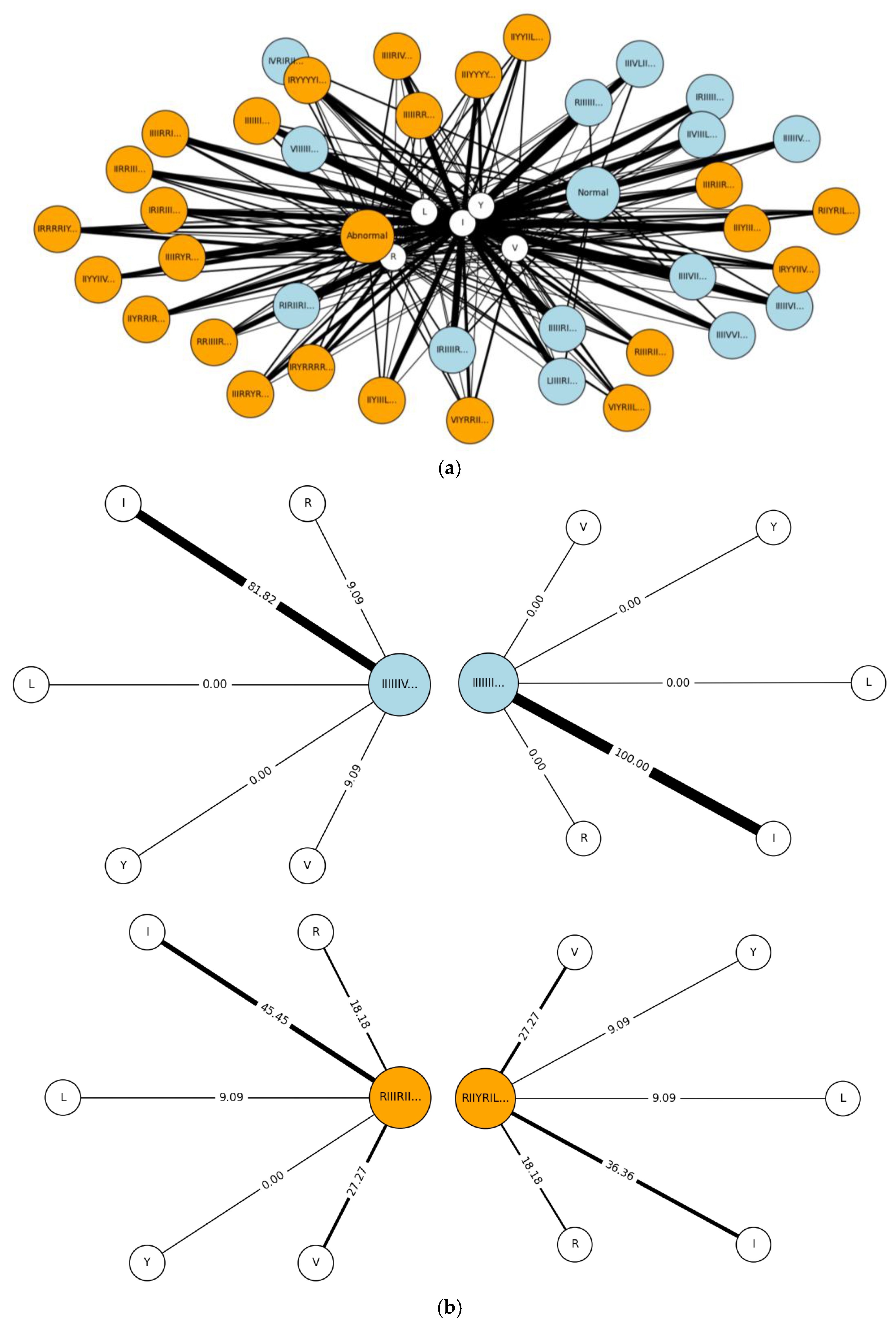

4.2. Non-Traditional Approach

5. Results

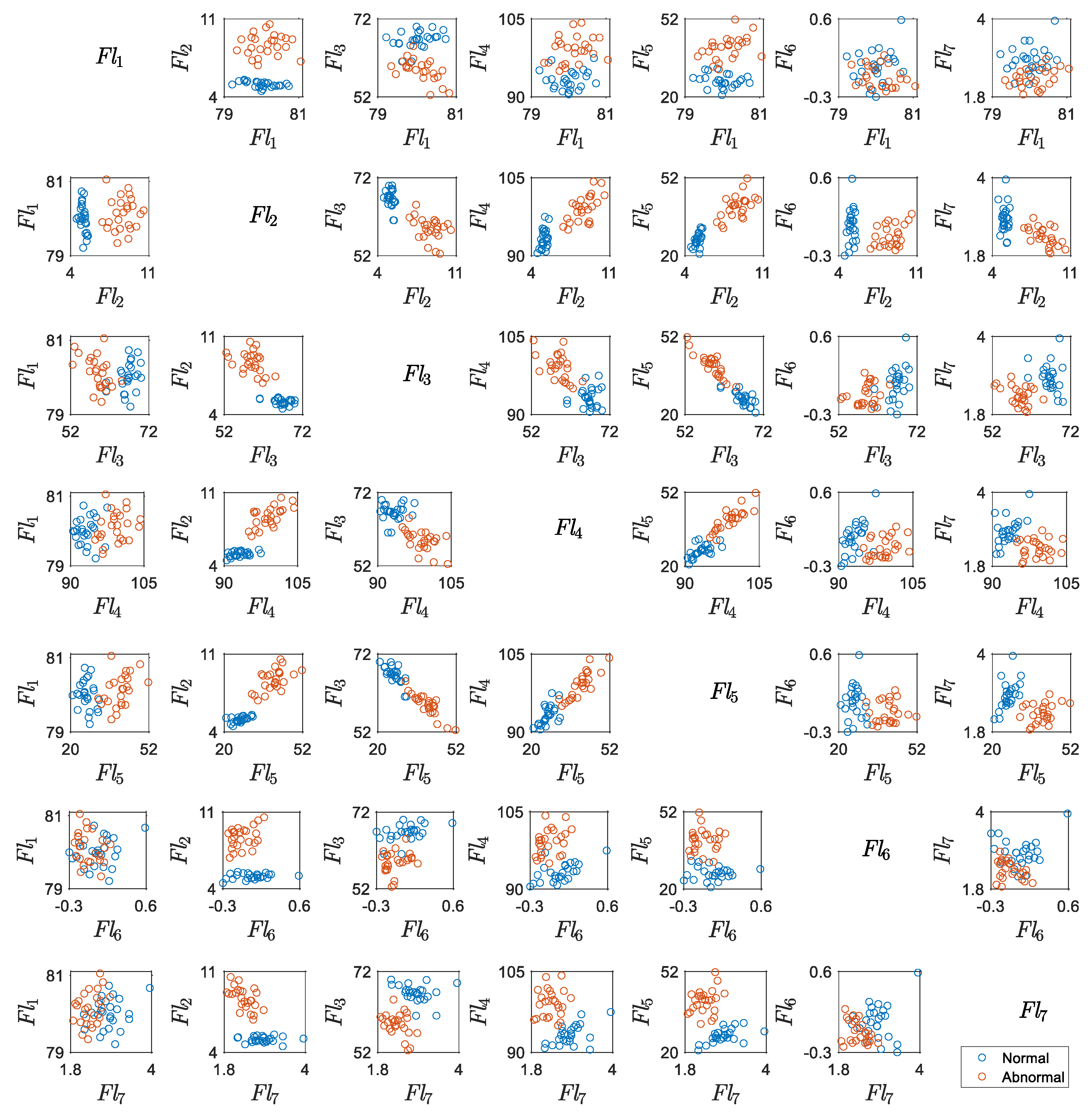

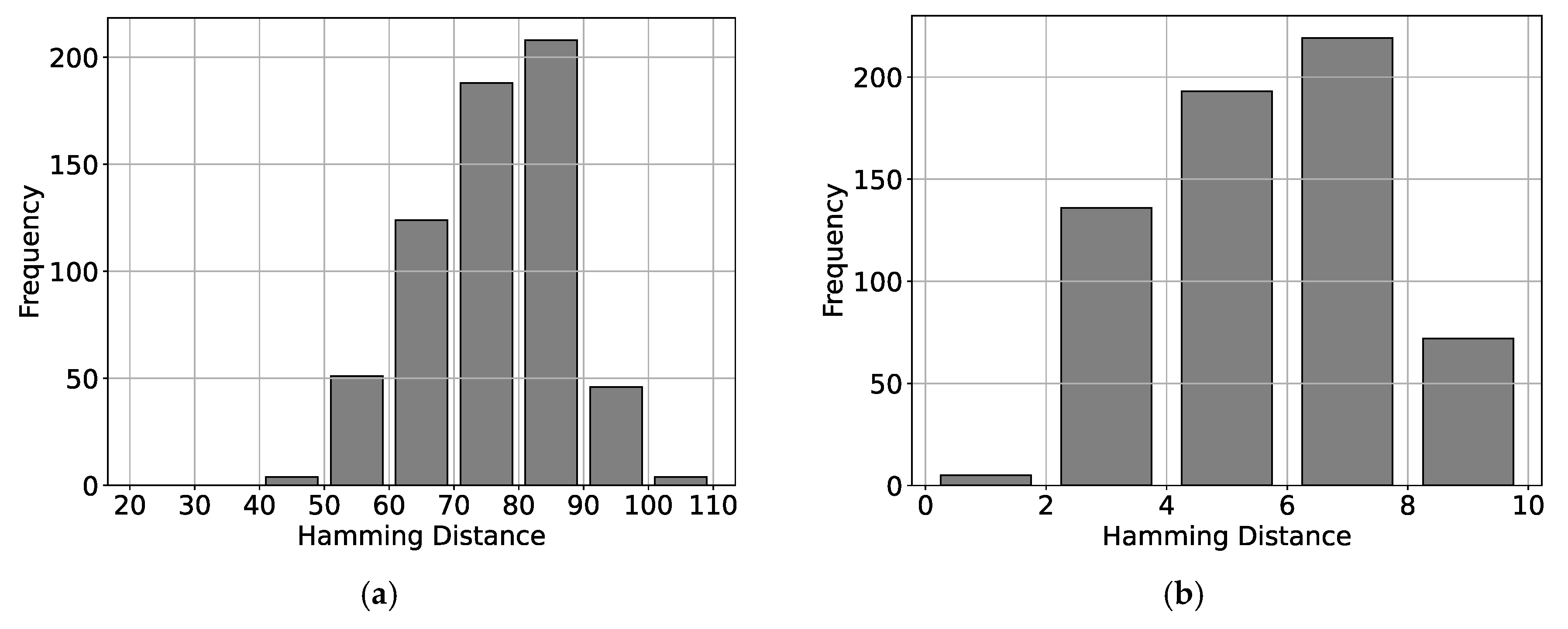

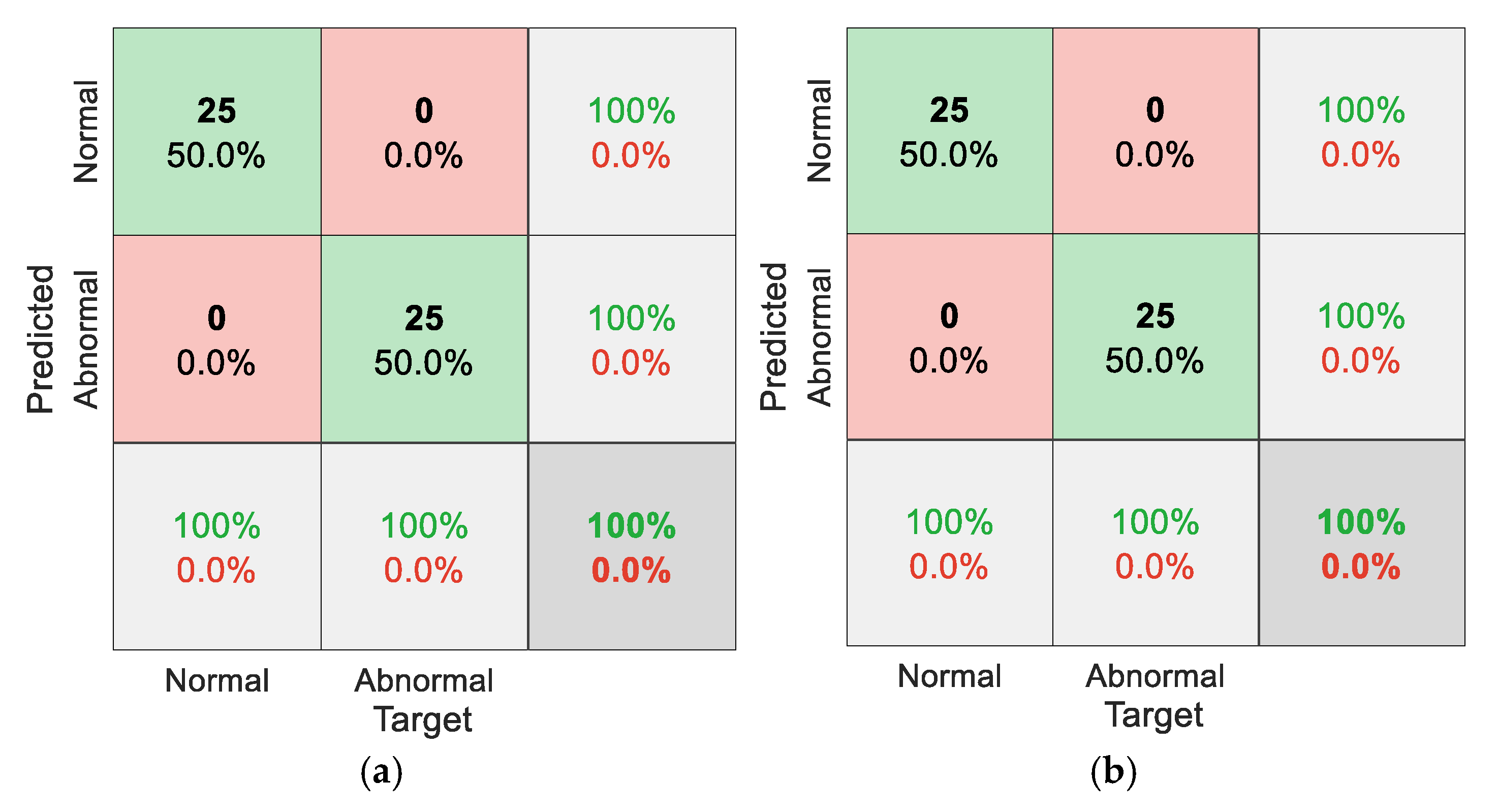

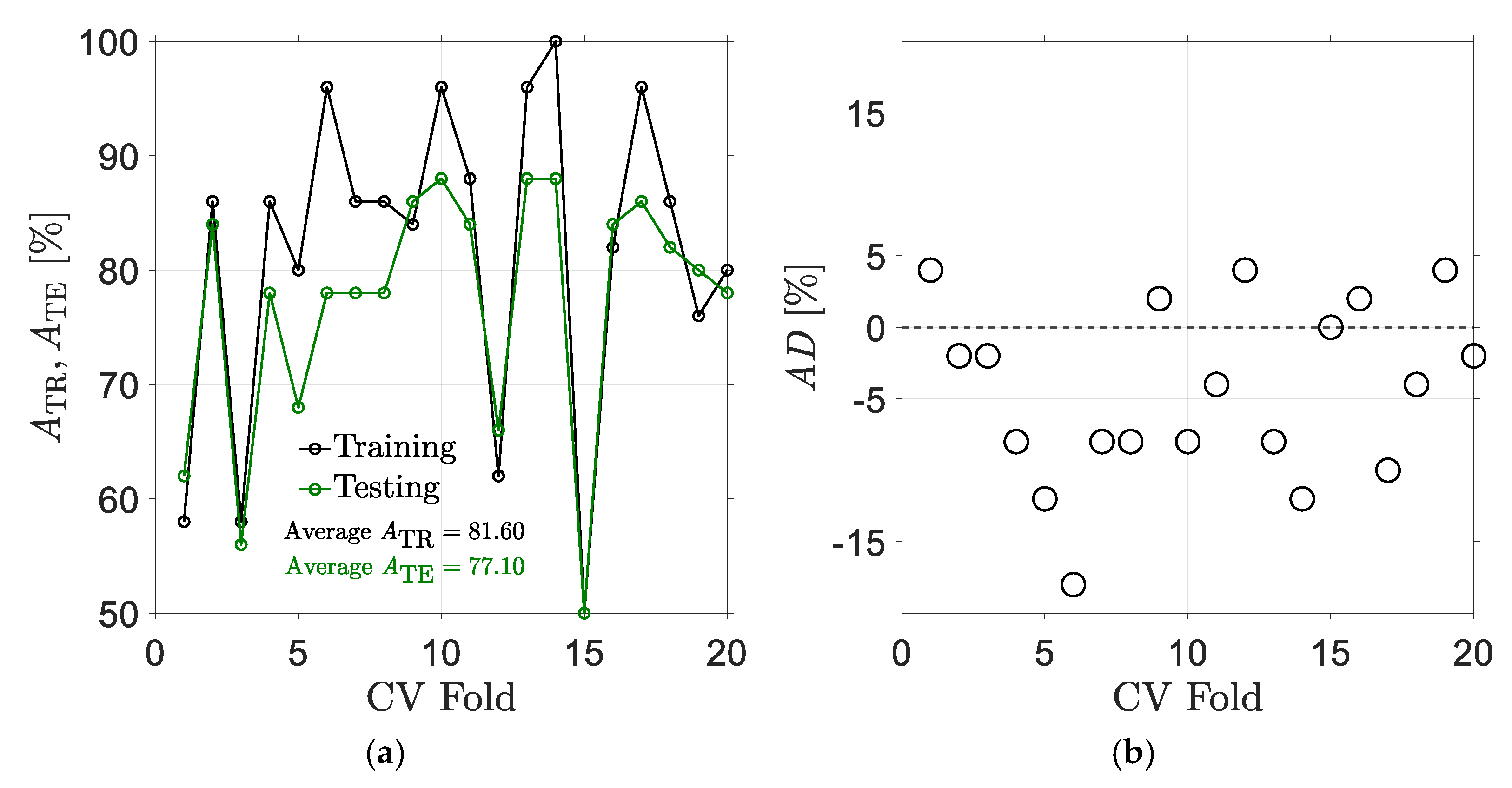

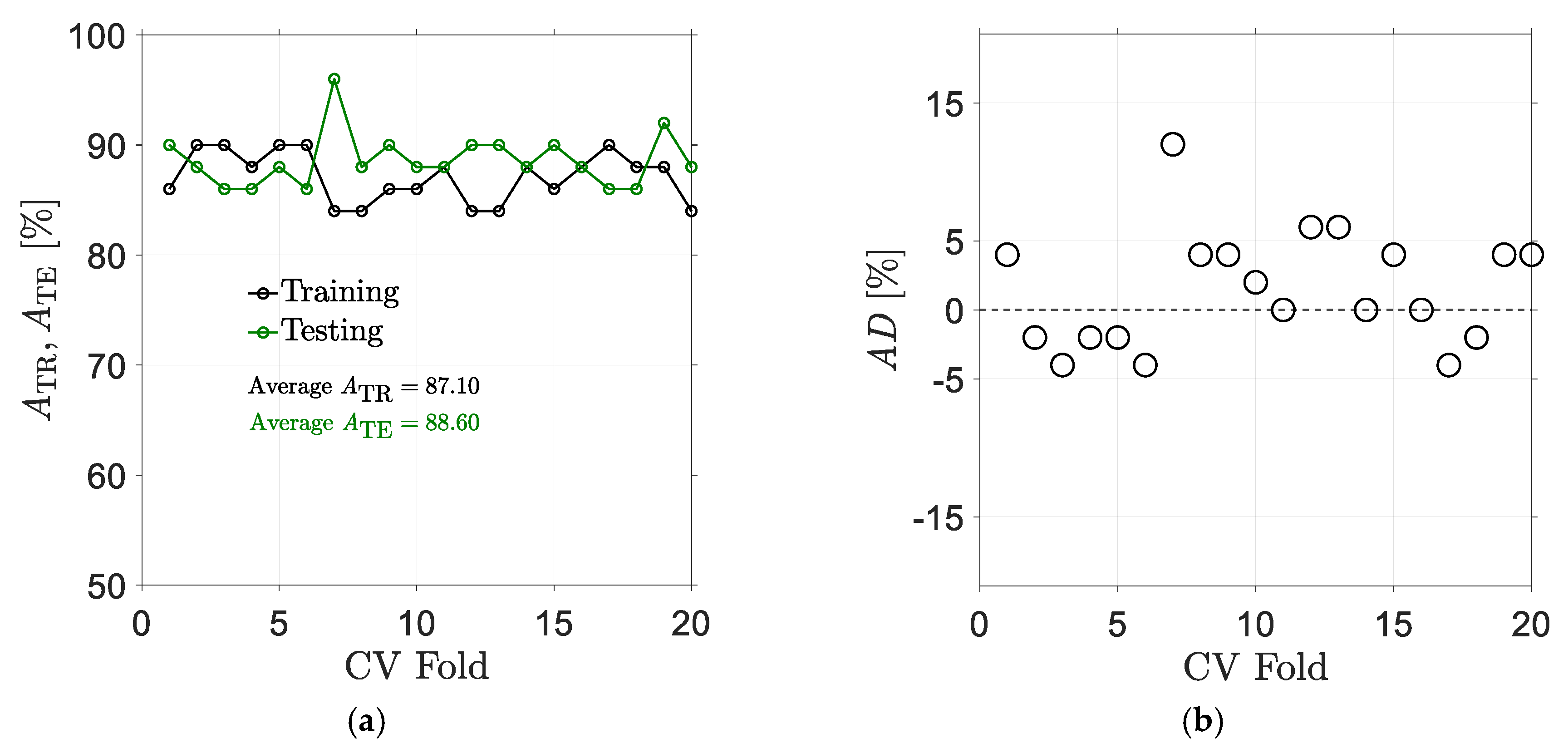

5.1. Results for Traditional Approach

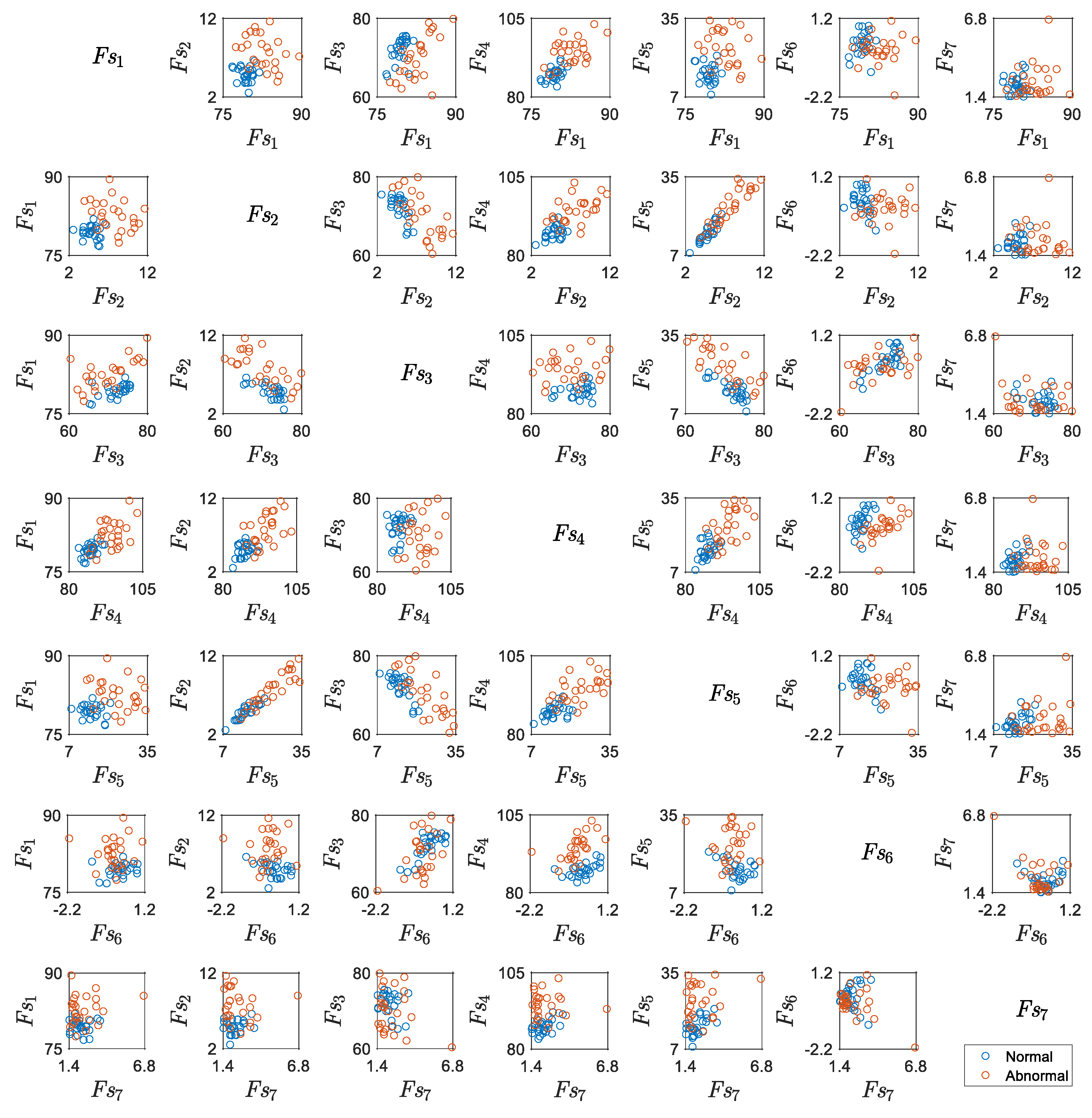

5.2. Results for Non-Traditional Approach

6. Conclusions

References

- Kusiak, A. Smart Manufacturing. Int. J. Prod. Res. 2018, 56, 508–517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oztemel, E.; Gursev, S. Literature Review of Industry 4.0 and Related Technologies. J. Intell. Manuf. 2020, 31, 127–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monostori, L.; Kádár, B.; Bauernhansl, T.; Kondoh, S.; Kumara, S.; Reinhart, G.; Sauer, O.; Schuh, G.; Sihn, W.; Ueda, K. Cyber-Physical Systems in Manufacturing. CIRP Ann. 2016, 65, 621–641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, X.; Zhou, J.; Lin, Y.; Li, Y.; Yu, H.; Liu, Y. Smart Manufacturing Based on Cyber-Physical Systems and Beyond. J. Intell. Manuf. 2019, 30, 2805–2817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, Y.; Cecil, J. An Internet of Things (IoT)-Based Collaborative Framework for Advanced Manufacturing. Int. J. Adv. Manuf. Technol. 2016, 84, 1141–1152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bi, Z.; Jin, Y.; Maropoulos, P.; Zhang, W.-J.; Wang, L. Internet of Things (IoT) and Big Data Analytics (BDA) for Digital Manufacturing (DM). Int. J. Prod. Res. 2023, 61, 4004–4021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghosh, A.K.; Fattahi, S.; Ura, S. Towards Developing Big Data Analytics for Machining Decision-Making. J. Manuf. Mater. Process. 2023, 7, 159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fattahi, S.; Okamoto, T.; Ura, S. Preparing Datasets of Surface Roughness for Constructing Big Data from the Context of Smart Manufacturing and Cognitive Computing. Big Data Cogn. Comput. 2021, 5, 58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iwata, T.; Ghosh, A.K.; Ura, S. Toward Big Data Analytics for Smart Manufacturing: A Case of Machining Experiment. Proc. Int. Conf. Des. Concurr. Eng. Manuf. Syst. Conf. 2023, 2023, 33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Segreto, T.; Teti, R. Machine Learning for In-Process End-Point Detection in Robot-Assisted Polishing Using Multiple Sensor Monitoring. Int. J. Adv. Manuf. Technol. 2019, 103, 4173–4187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aheleroff, S.; Xu, X.; Zhong, R.Y.; Lu, Y. Digital Twin as a Service (DTaaS) in Industry 4.0: An Architecture Reference Model. Adv. Eng. Inform. 2021, 47, 101225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghosh, A.K.; Ullah, A.S.; Teti, R.; Kubo, A. Developing Sensor Signal-Based Digital Twins for Intelligent Machine Tools. J. Ind. Inf. Integr. 2021, 24, 100242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bijami, E.; Farsangi, M.M. A Distributed Control Framework and Delay-Dependent Stability Analysis for Large-Scale Networked Control Systems with Non-Ideal Communication Network. Trans. Inst. Meas. Control 2018, 41, 768–779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ura, S.; Ghosh, A.K. Time Latency-Centric Signal Processing: A Perspective of Smart Manufacturing. Sensors 2021, 21, 7336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beckmann, B.; Giani, A.; Carbone, J.; Koudal, P.; Salvo, J.; Barkley, J. Developing the Digital Manufacturing Commons: A National Initiative for US Manufacturing Innovation. Procedia Manuf. 2016, 5, 182–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghosh, A.K.; Ullah, A.S. Delay Domain-Based Signal Processing for Intelligent Manufacturing Systems. In Proceedings of the 15th CIRP Conference on Intelligent Computation in Manufacturing Engineering (CIRP ICME’21); Elsevier: Gulf of Naples, Italy, 2021.

- Jauregui, J.C.; Resendiz, J.R.; Thenozhi, S.; Szalay, T.; Jacso, A.; Takacs, M. Frequency and Time-Frequency Analysis of Cutting Force and Vibration Signals for Tool Condition Monitoring. IEEE Access 2018, 6, 6400–6410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teti, R.; Segreto, T.; Caggiano, A.; Nele, L. Smart Multi-Sensor Monitoring in Drilling of CFRP/CFRP Composite Material Stacks for Aerospace Assembly Applications. Appl. Sci. 2020, 10, 758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Segreto, T.; Karam, S.; Teti, R. Signal Processing and Pattern Recognition for Surface Roughness Assessment in Multiple Sensor Monitoring of Robot-Assisted Polishing. Int. J. Adv. Manuf. Technol. 2017, 90, 1023–1033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hameed, S.; Junejo, F.; Amin, I.; Qureshi, A.K.; Tanoli, I.K. An Intelligent Deep Learning Technique for Predicting Hobbing Tool Wear Based on Gear Hobbing Using Real-Time Monitoring Data. Energies 2023, 16, 6143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, Y.; Zhou, P.; Yan, Y.; Agrawal, A.; Wang, Y.; Guo, D.; Goel, S. New Insights into the Methods for Predicting Ground Surface Roughness in the Age of Digitalisation. Precis. Eng. 2021, 67, 393–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Byrne, G.; Dimitrov, D.; Monostori, L.; Teti, R.; Van Houten, F.; Wertheim, R. Biologicalisation: Biological Transformation in Manufacturing. CIRP J. Manuf. Sci. Technol. 2018, 21, 1–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ura, S.; Zaman, L. Biologicalization of Smart Manufacturing Using DNA-Based Computing. Biomimetics 2023, 8, 620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wegener, K.; Damm, O.; Harst, S.; Ihlenfeldt, S.; Monostori, L.; Teti, R.; Wertheim, R.; Byrne, G. Biologicalisation in Manufacturing – Current State and Future Trends. CIRP Ann. 2023, 72, 781–807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murphy, K.P. Probabilistic Machine Learning: An Introduction; Adaptive computation and machine learning series; The MIT Press: Cambridge, Massachusetts, 2022; ISBN 978-0-262-04682-4. [Google Scholar]

- Wahid, M.F.; Tafreshi, R.; Langari, R. A Multi-Window Majority Voting Strategy to Improve Hand Gesture Recognition Accuracies Using Electromyography Signal. IEEE Trans. Neural Syst. Rehabil. Eng. 2020, 28, 427–436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kausar, F.; Mesbah, M.; Iqbal, W.; Ahmad, A.; Sayyed, I. Fall Detection in the Elderly Using Different Machine Learning Algorithms with Optimal Window Size. Mob. Netw. Appl. 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maged, A.; Xie, M. Recognition of Abnormal Patterns in Industrial Processes with Variable Window Size via Convolutional Neural Networks and AdaBoost. J. Intell. Manuf. 2023, 34, 1941–1963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haoua, A.A.; Rey, P.-A.; Cherif, M.; Abisset-Chavanne, E.; Yousfi, W. Material Recognition Method to Enable Adaptive Drilling of Multi-Material Aerospace Stacks. Int. J. Adv. Manuf. Technol. 2024, 131, 779–796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ullah, A.M.M.S. A DNA-Based Computing Method for Solving Control Chart Pattern Recognition Problems. CIRP J. Manuf. Sci. Technol. 2010, 3, 293–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Batool, S.; Khan, M.H.; Farid, M.S. An Ensemble Deep Learning Model for Human Activity Analysis Using Wearable Sensory Data. Appl. Soft Comput. 2024, 159, 111599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ullah, A.M.M.S.; D’Addona, D.; Arai, N. DNA Based Computing for Understanding Complex Shapes. Biosystems 2014, 117, 40–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alyammahi, H.; Liatsis, P. Non-Intrusive Appliance Identification Using Machine Learning and Time-Domain Features. In Proceedings of the 2022 29th International Conference on Systems, Signals and Image Processing (IWSSIP); IEEE: Sofia, Bulgaria, June 1 2022; pp. 1–5. [Google Scholar]

- Feiner, L.; Chamoulias, F.; Fottner, J. Real-Time Detection of Safety-Relevant Forklift Operating States Using Acceleration Data with a Windowing Approach. In Proceedings of the 2021 International Conference on Electrical, Computer, Communications and Mechatronics Engineering (ICECCME); IEEE: Mauritius, Mauritius, October 7 2021; pp. 1–6.

- Clerckx, B.; Huang, K.; Varshney, L.; Ulukus, S.; Alouini, M. Wireless Power Transfer for Future Networks: Signal Processing, Machine Learning, Computing, and Sensing. IEEE J. Sel. Top. Signal Process. 2021, 15, 1060–1094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cuentas, S.; García, E.; Peñabaena-Niebles, R. An SVM-GA Based Monitoring System for Pattern Recognition of Autocorrelated Processes. Soft Comput. 2022, 26, 5159–5178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Derakhshi, M.; Razzaghi, T. An Imbalance-Aware BiLSTM for Control Chart Patterns Early Detection. Expert Syst. Appl. 2024, 249, 123682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Addona, D.M.; Matarazzo, D.; Ullah, A.M.M.S.; Teti, R. Tool Wear Control through Cognitive Paradigms. Procedia CIRP 2015, 33, 221–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Addona, D.M.; Ullah, A.M.M.S.; Matarazzo, D. Tool-Wear Prediction and Pattern-Recognition Using Artificial Neural Network and DNA-Based Computing. J. Intell. Manuf. 2017, 28, 1285–1301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caggiano, A.; Nele, L.; Fraunhofer Joint Laboratory of Excellence on Advanced Production Technology (Fh-J_LEAPT UniNaples) P.le Tecchio 80, Naples 80125, Italy; Department of Industrial Engineering, University of Naples Federico II, Naples, Italy; Department of Chemical, Materials and Industrial Production Engineering, University of Naples Federico II, Naples, Italy Artificial Neural Networks for Tool Wear Prediction Based on Sensor Fusion Monitoring of CFRP/CFRP Stack Drilling. Int. J. Autom. Technol. 2018; 12, 275–281. [CrossRef]

- Guo, W.; Wu, C.; Ding, Z.; Zhou, Q. Prediction of Surface Roughness Based on a Hybrid Feature Selection Method and Long Short-Term Memory Network in Grinding. Int. J. Adv. Manuf. Technol. 2021, 112, 2853–2871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, W.J.; Mendis, G.P.; Triebe, M.J.; Sutherland, J.W. Monitoring of a Machining Process Using Kernel Principal Component Analysis and Kernel Density Estimation. J. Intell. Manuf. 2020, 31, 1175–1189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y.; Xue, W. A Multisensor Fusion Method for Tool Condition Monitoring in Milling. Sensors 2018, 18, 3866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bagga, P.J.; Makhesana, M.A.; Darji, P.P.; Patel, K.M.; Pimenov, D.Y.; Giasin, K.; Khanna, N. Tool Life Prognostics in CNC Turning of AISI 4140 Steel Using Neural Network Based on Computer Vision. Int. J. Adv. Manuf. Technol. 2022, 123, 3553–3570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crick, F. Central Dogma of Molecular Biology. Nature 1970, 227, 561–563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohammadi-Kambs, M.; Hölz, K.; Somoza, M.M.; Ott, A. Hamming Distance as a Concept in DNA Molecular Recognition. ACS Omega 2017, 2, 1302–1308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shan, G. Monte Carlo Cross-Validation for a Study with Binary Outcome and Limited Sample Size. BMC Med. Inform. Decis. Mak. 2022, 22, 270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Steps | Description | |

|---|---|---|

| Creation | 100 datasets are created, of which 50 are “Normal” and 50 are “Abnormal,” following the definitions in [30]. | |

| Splitting | Using stratified sampling, the created datasets are divided into a training set and a test set, each containing 50 datasets. | |

| Windowing | Long | The training and test sets are processed with a long window size of 150, resulting in long-windowed datasets. |

| Short | The training and test sets are processed with a short window size of 10, resulting in short-windowed datasets. | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).