1. Introduction

The role of real time ROM technology along with hybrid and smart ML schemes have already revolutionized many industrial processes where digital twin and digital shadow concepts were developed for the process controlling and design optimizations. The introduction of process-data paradigm and the use of ML technologies have immensely modernized the process control concepts where the real-time predictions and corrections can be employed for the better control over the industrial processes. Furthermore, the use of hybrid and smart data-handling technologies can help to assess the performance of final parts for their service life scenarios. However, introduction of these new technologies has not made the use of conventional analytical, experimental and numerical modelling redundant, rather it made their employments smarter by integrating their results into the evolving database notion. Hence, dynamic and evolving databases can be accumulated for training of models using data generated from analytical, experimental and further off-line detailed numerical simulation studies [

1,

2,

3].

The systematic integration of these new technologies into AM processes can help to achieve faster and more accurate predictive models and avoid the long and expensive additional experimental and numerical efforts. Hence, appropriate ROM techniques are made to enhance the digital twin and digital shadow concepts [

4,

5,

6]. In this study, the combination of hybrid physical-data driven and ROM techniques along with ML modules have been employed for the WAAM deposition process. In addition, a numerical simulation framework has also been setup to provide enough data for the ROM and ML schemes. Furthermore, a snapshot matrix has been generated for the deposition process using variation of input variables (e.g., initial temperature, deposition speed, torch power) to examine their effects on the final component. To make the ROM predictive model works better, part of the data has been used to derive the reduced model (including its training) while rest of the data are used to validate the performance of the ROM.

2. Simulation of AM Processes—Methodology

Different modelling techniques have been employed for the simulation of AM processes where many inherent thermal and mechanical characteristics of these processes are considered. Although many different AM process technologies have been developed for metallic and non-metallic components, many of the process functionalities are similar in terms of the numerical modelling approaches. The Finite Element (FE) method have been extensively used for the simulation of processes like AM, where different approaches have been developed to deal with the dynamic nature of these processes [

7,

8,

9,

10]. As the AM parts are deposited and built-up layer by layer during the process, the conventional FE methods with their fixed domain size are only able to simulate the part final geometry without any consideration of the progress of layered structure. Although, many alternative FE techniques have been developed to alleviate these short comes by dynamic mesh generation, de-activation\activation and some hybrid techniques, the accurate modelling of deposition processes are still a cumbersome task [

11,

12,

13,

14].

2.1. Dynamic FE Techniques

The application of alternative FE methods for dynamic manufacturing processes like casting and AM have lately been promoted with an aim to simulate progressively generated parts using both fixed-size and variable-size numerical domains. Since these processes inherently involve multi-physical thermal, fluid and solid features and they might also have some multi-scale microstructural evolution phenomena, the proposed dynamic FE methods need to handle different physical and dimensionality aspects of these processes. This would inevitably raise challenges for the conventional FE method where geometries of domains are prepared and discretized at the start of simulation prior to solution phase and all system matrices are initially assembled to be able to calculate the full system responses. Hence, to alleviate this numerical complications, different simulation strategies including deactivation and activation methods and some more novel dynamic mesh generating frameworks have been proposed [

7,

15].

For the so-called Deactivation and Activation Technique (DAT) for AM process, the common practice is to deactivate almost all of the mesh related to the finished part at the start of simulation (except initial base elements) and re-activate them (layer by layer or block-wise) as the simulation of the dynamic process is proceeding [

14,

16,

17]. Although that would help to simulate the dynamic nature of the process using conventional FE method, the deactivation process would not remove elements from assembled matrices, rather it reduces their numerical impacts to very small values (e.g., using very small multipliers). In addition, any changes in the material properties and system boundaries during the process cannot be simulated since the system matrices are assembled at the start of simulation. That would also mean that the solver needs to solve full system matrices from the start of simulation which is computationally inefficient. Hence, the Dynamic Mesh Techniques (DMT) have recently been proposed to remove obstacles related to DAT by generating or splitting mesh during the simulation where new mesh blocks or layers can be adapted into mainstream FE techniques for AM applications [

4,

10]. These techniques would treat the progressive generation of AM parts during the simulation by generating and appending mesh blocks in a predefined or calculated manner which would be attached to the main numerical domain.

2.2. Evolving Domain Technique Ubsection

One of the recent DMT frameworks which has been proposed for AM processes are evolving domain technique where the transient nature of the numerical domain and its continuous expansion throughout the processing times are considered. The new technique along with its appending block-mesh scheme have been developed [

14] to ease the numerical issues associated with the domain expansion and dynamic discretization of evolving domains. The expansion of the numerical domain is considered using a dynamic zone where new layers of mesh (or mesh blocks) can be appended to the existing domain in tempo-spatial manner. The spatial directions for expansion of the numerical domain can be defined using a predefined path (e.g., material deposition direction) or by calculation of required growth during the transient simulation. The technique would eliminate a generation of steady-state mesh with birth and death features, and it also eradicates the need for the splitting of element layers at the deposition front.

For the AM process simulations, the continuous deposition processes at different spatial directions can be simulated using mesh evolution technique at the deposition front. In this research work, an in-house code has been developed to control and implement the dynamic mesh generation and insertion (in Phyton) as follows:

- ➢

First the initial geometry of necessary components including baseplate are generated and meshed.

- ➢

In the second step, the initial thermal and mechanical boundaries are considered, and the initial system matrices are assembled.

- ➢

The first time-steps\iterations are subsequently solved using a thermal-mechanical solver and the deposition front coordinates are updated.

- ➢

The domain geometry and mesh are later adapted by inserting a mesh block based on the deposition direction and speed.

- ➢

In the next step, the domain matrices are updated with new mesh entries and the extra input energy is disseminated amongst the domain using mapping technique.

- ➢

In the final step of the loop, after achieving thermal energy balance the previous converged solution is used as a first step for a newly updated domain and the simulation scheme continues with the new geometry\mesh till the next evolution step is triggered.

The computational performance of the technique for industrial casting applications have already been examined and extensive numerical investigations have revealed that the higher speed and accuracy can be achieved using evolving domain technique [

14].

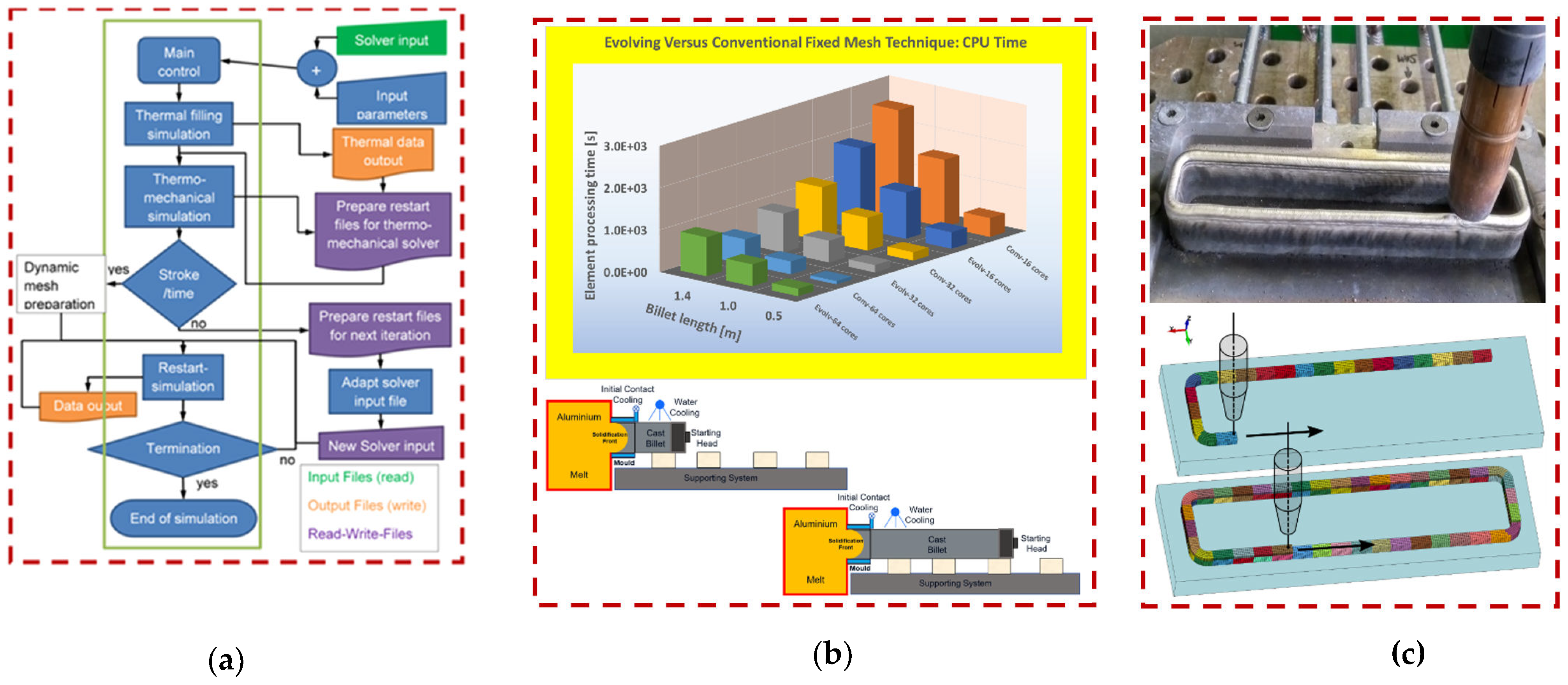

Figure 1a and

Figure 1b show the flowchart for the evolving algorithm along with the comparison study for numerical performance of the technique compared to conventional methods (for horizontal casting cases). While

Figure 1c shows the mesh insertion technique for the simulation of WAAM deposition process where new meshes are appended to the existing domain to match the material deposition process [

10]. More comprehensive discussions about the evolving domain technique can be found in [

18].

3. Methods for AM Reduced Models

Cyber-physical modelling along with the new concepts of digital twins and shadows have already found their ways into industrial processes where optimized design and control of these processes are revolutionized using digitalization schemes. The sensing technologies, data gathering, data filtering and data processing schemes along with ROM (for the fast predictive-corrective analyses) have created an important part of the digitalization framework for a process-data paradigm. The ROM technologies have also been going through rapid transformation to achieve fast and reliable predictions in the real-time using new analytical and mathematical concepts. Although conventional reduced modelling techniques have been employed in the last fifty years to limit the computational time and resources for detailed process simulations, they are unable to provide real-time predictions during processes. Hence, in recent years attentions have been paid to the new generation of ROMs where fast predictions and corrections can be made in the real-time during AM processes.

3.1. ROM Techniques for AM Processes

The increasing tendency towards real-time simulations of complex manufacturing processes has motivated many research activities to formulate fast ROMs where new mathematical and analytical concepts are used for a novel computational framework [

19,

20]. Although many different techniques have been exploited to create suitable ROMs for transient and steady state processes, the issues of accuracy, speed and solution stability have remained unresolved for many multi-physical aspects of industrial processes. Hence, many mathematical decomposition, projection and dimensional reduction techniques have been developed to reduce the long computational efforts for modelling of multi-physical nature of these processes. For the AM processes, the popular thermal-mechanical and\or fluid-thermal-mechanical detailed simulations are routinely performed for optimization of power, material delivery, deposition speed, heating and cooling. The reduced versions of these simulations are cumbersome since the transient nature of AM processes with their continuous domain expansion are difficult to predict using any simplification scheme.

The concepts of characteristic equation, eigenvalue analyses and matrix factorization have been employed in this research to create a fast ROM framework for the transient AM processes where real-time predictive and corrective measures can be performed using previously measured or calculated data. To start, let’s consider a conventional second order differential equation as;

where

,

and

are stiffness, mass and displacement matrices of the system. The simple solution along with eigen value model representation for the system can be written as;

where

and

A are eigen values (natural frequencies) and a constant multiplier, respectively. If the tempo-spatial characteristic of the system is decomposed, the characteristic equation of the system along with its solution for a point in space can then be written as;

where

are again the system natural frequencies and Fourier coefficients. Here, the characteristic equation of the system is calculated using the system properties including, geometry, material properties and boundaries. However, the computational time and efforts to solve the system equations using conventional time and frequency domain solvers are substantial. It makes the calculation of the system characteristics for engineering problems and processes long and costly and not suitable for the real-time digital twining. Hence, much research have recently been conducted to reduce the computational time and effort by developing special types of ROMs for industrial processes [

3,

6,

21,

22]. One of the interesting alternative techniques which have also been used in the current research work is to estimate the characteristic equation of the systems and processes instead of calculating them using smart data-driven techniques.

This ROM technology is initially based on the same mathematical eigenvalue and orthogonal eigenvector concepts to find the characteristic equation of the process. However, instead of using system properties to formulate the system matrices, it is based on calculated or measured responses of the system for the range of variables. Hence, if the responses of the system under varying parameters are known, a matrix of system responses under changing variables can be constructed which holds basic characteristic information about the system. The estimation of the system characteristic equation is then performed using mathematical decomposition techniques which have conventionally been used for eigenvalue analyses. To understand the basis of the mode decomposition technique for the estimation of characterization equation, let’s consider the governing equation for a vibrational problem as;

where

is called the dynamic stiffness matrix. Now consider the alternative governing equation for the response of the system as;

where

can be interpreted as desired response at specific values for variables,

is the estimated system characteristics (using data techniques) and

is the input values. In this research work the Singular Value Decomposition (SVD) is used to decompose the system response matrix which gives the optimal expansion of the matrix as;

where

U represents the spatial eigenvector decomposition, ∑ is the singular values diagonal matrix (e.g., eigenvalues) and

represent temporal decomposition for transient system responses. The SVD technique is a popular reduction technique based on linear algebra that can reduce the size of predictive models in terms of dimensions and time. The more mathematical description of the SVD method can be found in [

23,

24]. Using these reduced models, the transient responses of the system can be estimated using database of the previous responses in the real-time.

3.2. Hybrid ROM-ML Techniques

The advance of ROM techniques for industrial process simulations has confronted some challenges related to accuracy of data extrapolation and rate-dependency (e.g., for high cooling\heating rates). In many of these processes, the limited amount of available data along with the large number of influential parameters were promoting the use of some integrated ROM-ML hybrid schemes where further training of data can be performed. To help establish a ground for such a hybrid framework, appropriate ML and ROM techniques have to be employed to improve the predictive power of these models. Such a combined ROM-ML technique can allow the development of an agile and efficient fast models for the transient thermal-mechanical and\or fluid-thermal-mechanical WAAM process modelling.

For the data training in this research, a Neural Network (NN) ML scheme has been implemented using in-house code. For this NN scheme, both the Multi-Layer Perceptron (MLP) or the Back-Propagation Neural Networks (BPNN) might be employed for the training of system response data. For more data interpolation and extrapolation, the data extracted from experimental and detailed simulations were kept into a file where for each exemplar epoch a certain number of data were selected randomly without repetition of any learning vector. Since batching of concurrent inputs is computationally more efficient than sequential inputs, epochs and total computation of errors were used as follows;

where

tu , yu are desired and model outputs and the network error is computed based on RMS standard formulation where it is propagated into the network until convergence is reached. In the back propagating networks the modification of weights is proportional to error differential

with respect to weight

as;

After the data training, the resulting ROM-ML models can further update itself using the NN scheme where it can enhance the thermal and mechanical predictions for AM processes. Furthermore, these hybrid models can also be used for the modeling of sub-processes like heating and cooling during the AM processes [

4].

3.3. Case Study: Reduced Models for WAAM Process

Digital twin and cyber-physical modelling along with the concepts of the real-time predictions and corrections have already been employed for some AM industrial processes. The optimization of these processes along with active controlling are among the main goals for the twining technology where sensing technology, data generation and data processing schemes can be combined for the greener productions. For the case study here, attention is paid to the WAAM process which can be defined as a type of directed energy deposition (DED) scheme. In this manufacturing technique single or multiple plasma or electric arc torches are used to weld layers of wire feedstock on a pre-defined geometry. The heat generated by the moving torch is used to melt the wire where layers of materials can be built-up based on inter-layer fusion process.

Although, various sophisticated transient and steady-state numerical simulations of WAAM processes have already been developed, their employment for digital twining is restricted due to the substantial required computational time and resources. Hence, for the real-time predictions and corrections, the predictive power of ROM and ML can be employed. Consider the equation (6) for the prediction of temperature (and stress) responses during a WAAM process as;

where

are temperatures and stresses at process time

t and the snapshot results can be interpolated using radial basis function (RBF) or adaptive redial basis function (ARBF) as;

where

and

are the weighting coefficient for the RBF. Here the temperature at the any location can be predicted during the WAAM process using a sum of

k radial basis functions which are weighted by appropriate coefficients. For the RBF definition of WAAM processes with their high heating rate (passing of torch over measuring point), the artificial network architecture developed earlier can be employed where an input, hidden and an output layer can be defined as;

where

,

,

μ and

are temperature input vector, i

th neuron sample vector, i

th neuron bandwidth and i

th neuron output, respectively. The innovative combination of SVD and the neural network RBF for the implementation of WAAM reduced model can produce a fast and reliable predictions even in zones with high gradient data (e.g., high heating rates). To investigate the accuracy and reliability of the reduce technique, a WAAM case study has been carried out to simulate the welding of a single layer on top of a single thermal pre-conditioned wall. The wall has a dimension of 100mm x 50mm x 6mm and it is welded with aluminum 6061 alloy using plasma technique. For the initial verification study, experimental works have been conducted using thermo-couples to measure the temperature at selected locations. The results of these studies are then compared to thermal-mechanical FE simulations for verification and calibration. After completing the initial verification study, a snapshot matrix has been built using varying process parameters such as torch power, deposition speed and initial temperatures [

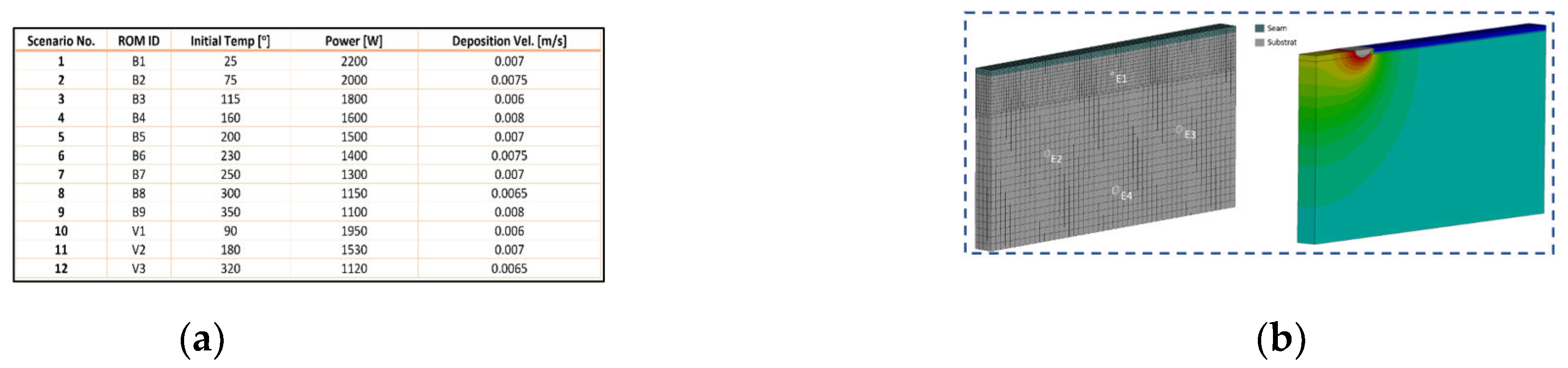

5]. A series of FE simulations are then performed using these scenarios to generate a database for the reduce model building. Nine scenarios have initially been used for buildings the model while three design of experiments (DOEs) cases have later been caried out for the validation of the reduced models.

Figure 2 shows the snapshot matrix along with the FE mesh and its typical temperature contour results during the torch passage.

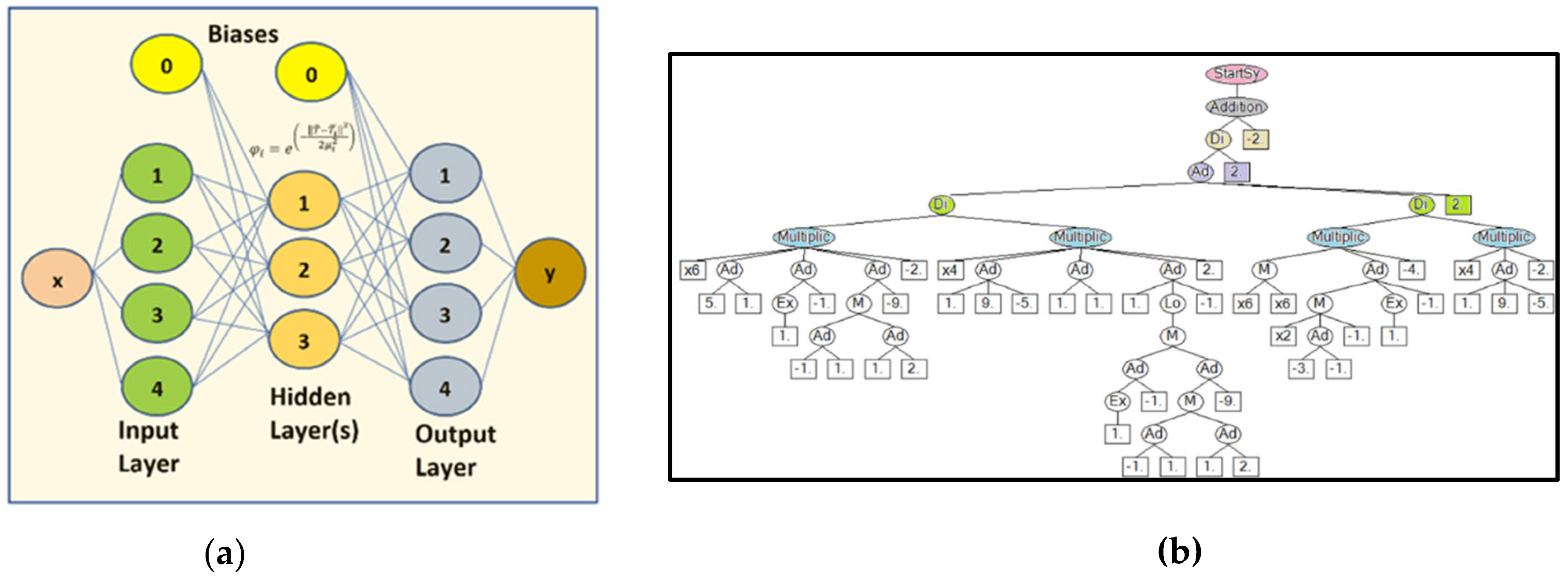

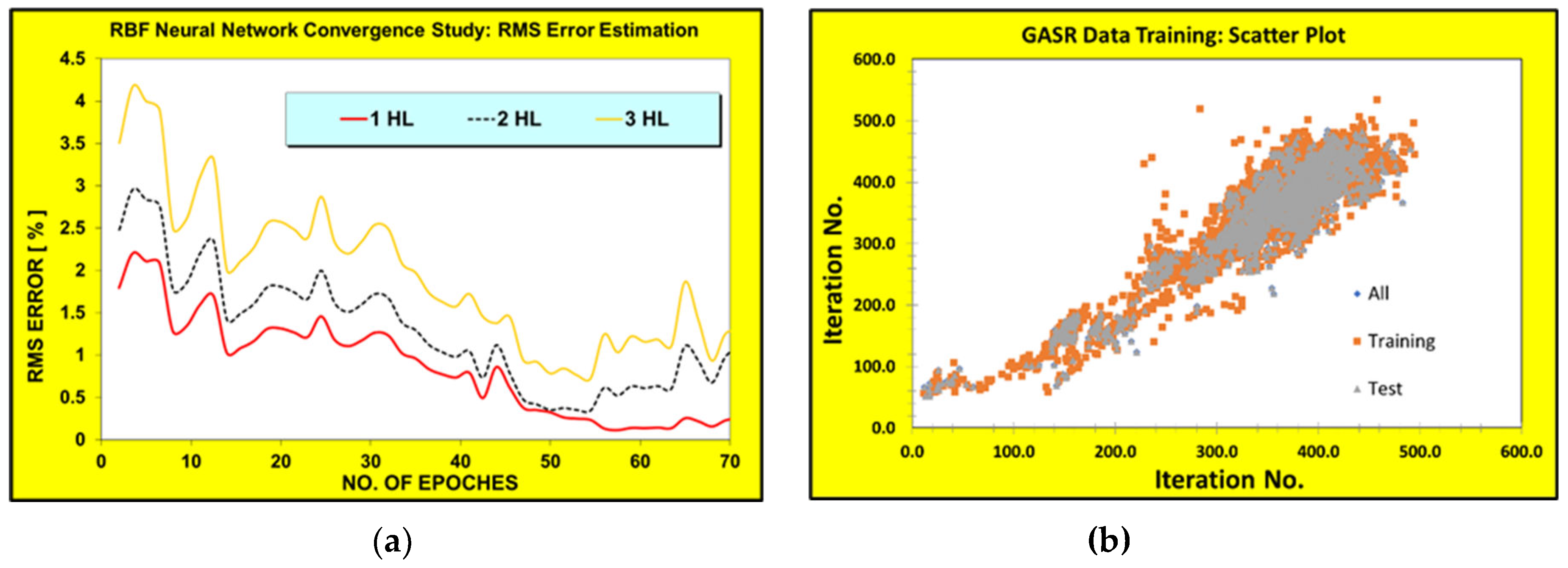

For data interpolation and training of the reduce models two different techniques are used, namely; genetic algorithm symbolic regression (GASR) and neural network. The GASR technique has capabilities for data processing, handling and fitting which can be carried out using available computer codes. In particular, the academic code HeuristicLab which is described in [

25] was used in this research work for the data handling and training. The GASR is a type of regression analysis that searches multi-dimensional space for mathematical expressions and operators using genetic algorithm to find the most suitable model. While, for the RBF neural network, the convergence of the networks is achieved using the dynamic node creation [

26] and some overlapping scheme for the test and training data. These techniques were carried out to increase the ability of the network near the search-space boundaries and even beyond (i.e., extrapolation). Since the RBF technique has been found more practical and yielded more accurate results for his study, the main basic reduce model has been built using the combination of SVD and RBF techniques.

Figure 3 shows the NN architecture and GASR tree-like diagram, while

Figure 4 shows their convergence and data training plots.

In the last part of the study, the performance of the SVD-RBF reduced model has been evaluated by comparing its results with other popular model building techniques. Five different techniques, namely; kriging, regression, support vector machine (SVM), clustering and inverse distance (InvD) were used to create alternative WAAM reduced models using the available data. The performances of these reduced models were then compared to trained SVD-RBF model for the three extra DOEs results. The temperature time histories for the deposition process have been collected for some specific nodes along the wall and the history results were composed for the whole simulation time. The performances of these reduced models have then been compared with the SVD-RBF model by calculating the normalized error histories.

4. Discussion

The development of an accurate and real-time reduced models for metallic and polymeric AM processes with their multi-physical aspects are challenging and careful considerations should be given to data training and testing. In this study, the eigen-based SVD technique has been enhanced with interpolation and training power of RBF and neural network to establish an efficient and accurate reduced model. The verifications of the proposed reduced model have shown that it can be reliably employed to produce real-time predictions of the time history temperature and stress\strain results. However, due to the lack of space for in-depth discussions only the temperature results were presented herein, and the mechanical deformations, stress and strain results were excluded. At the first glance on accuracy and reliability of these models, it can be presumed that they are fairly capable of predicting the responses even with small and limited size databases (and large range of variations for process parameters). However, there are still challenges in the generation and training of these type of reduced models which need to be overcome before they can solidly be employed within the digital twin concepts, namely;

- ➢

For WAAM processes with their thermal-mechanical and multi-physical aspects, reduced models need to be able to cope with rapidly changing data specially for high cooling and heating rate processes.

- ➢

The sizes and variation of data within snapshot matrix can considerably affect the prediction power of these models where different sampling techniques should be employed to cover the whole multi-dimensional search-space (e.g., Sobol, Latin Hypercube…).

- ➢

To carefully verify the performance of these models, it is required to setup a rigorous validation criterion where performance maps at internal, near boundary and extreme condition (extrapolation) of search space are examined.

- ➢

Although the use of Neural Network and GASR techniques can greatly increase the predictive power of reduce models, customized training schemes are required for the proper data interpolation and fitting.

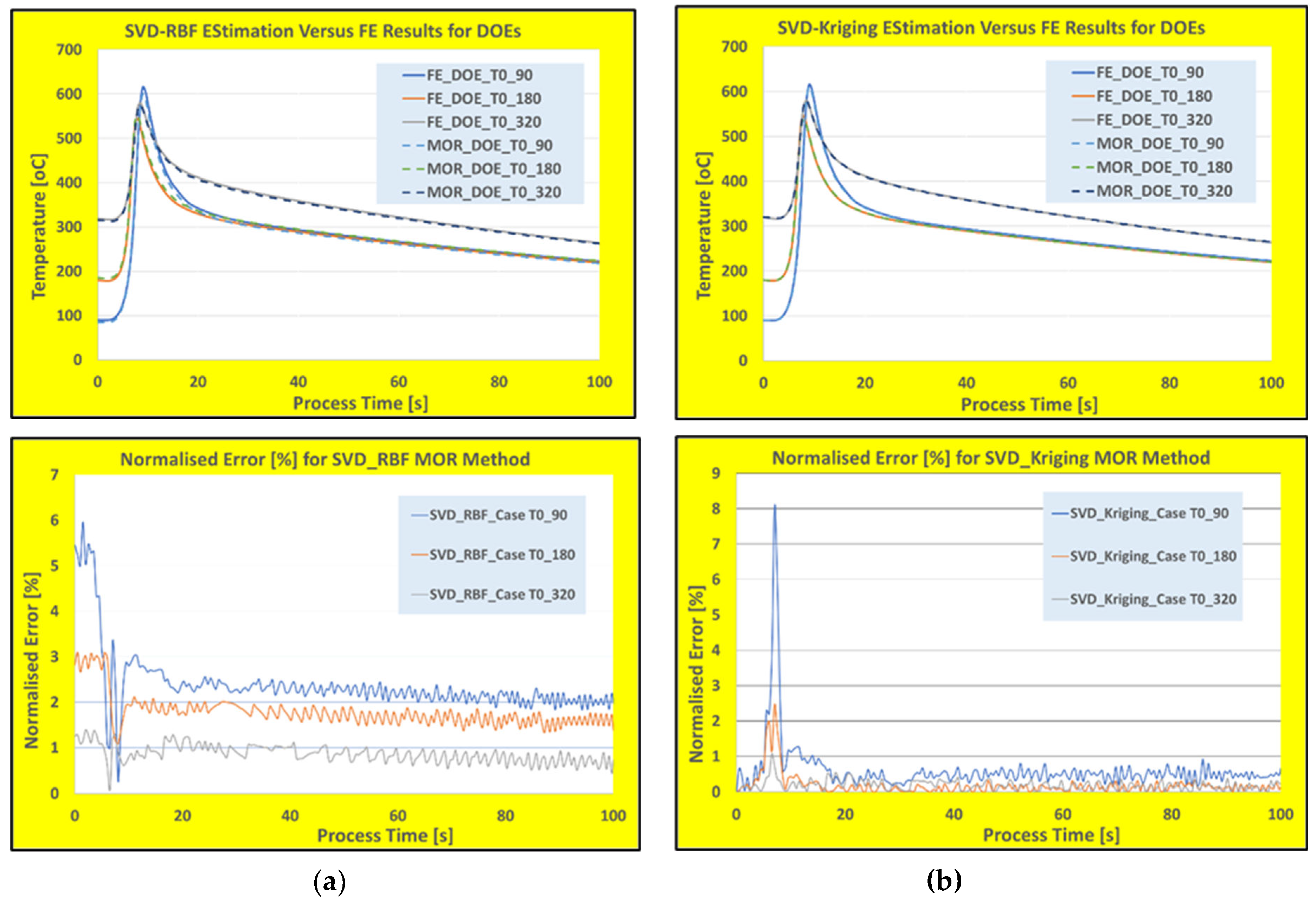

Figure 5 shows the estimation of time history temperature for a computational node along the deposited wall for the FE, trained SVD-RBF and SVD-Kriging reduced models. The computational time for the FE simulation is about 2880 seconds for every scenario (i.e., wall clock time), while it takes only about 0.72 second for the reduced models to estimate the time history responses.

Figure 5a shows the comparison of temperature predictions along with normalized error graphs (with respect to verified FE results) for the proposed SVD-RBF method for the three verifications DOEs. While the

Figure 5b shows these results for the popular SVD-Kriging reduced model. The Kriging method is one of the best interpolation methods which uses a limited set of sampled data points to evaluate the spatio-temporal variables over a continuous search space.

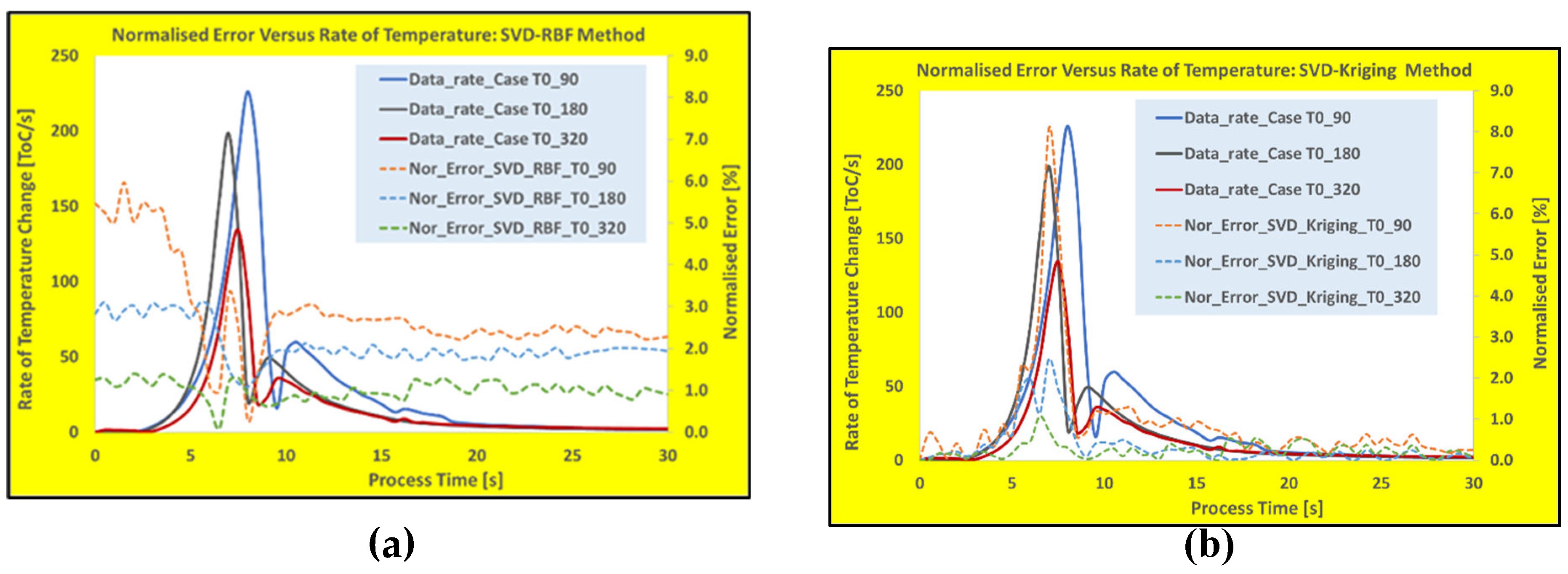

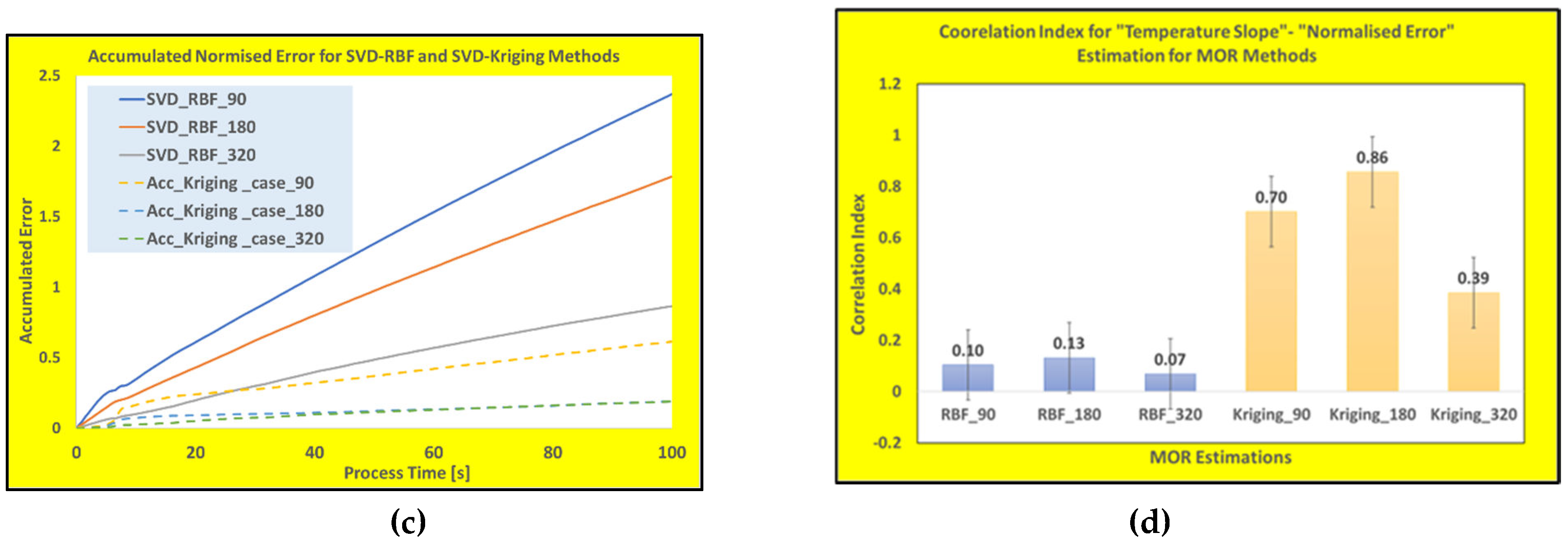

At the first glimpse on calculated errors, for the time when the heating rate is high (when the torch is passing over the measuring point), it can be observed that the proposed SVD-RBF trained model shows lower error margins (almost no data rate-dependency). While the popular SVD-Kriging shows a higher error margin for these times, but with a steady lower error margin along the rest of the time history results. Further investigation of the data rate-dependency for these two techniques were shown in

Figure 6a and

Figure 6b where the correlation of normalized error time histories with the rate of temperature changes (heating rate) were plotted for both techniques. Whereas

Figure 6c and

Figure 6d show the accumulated normalized error over the whole time-history and the Pearson correlation index for both techniques.

As it appears from these results, while the SVD-RBF model predictions are more accurate for high heating rate zone (i.e., almost rate-independent), the SVD-Kriging normalized error results show strong heating rate dependency. However, the latter technique produces about 1% lower error margin after the torch passage over the measuring point (better data fitting at low temperature changes). Hence, due to their effective sampling and interpolation schemes, both SVD-RBF and SVD-Kriging techniques are suitable for WAAM processes with moderate heating\cooling rates. For the high heating\cooling rate processes, it is recommended to use the trained SVD-RBF technique for the model building procedures. To prove the superiority of these techniques for the real-time modelling, the final part of the study has been devoted to show the performance of other popular reduced model techniques for WAAM processes.

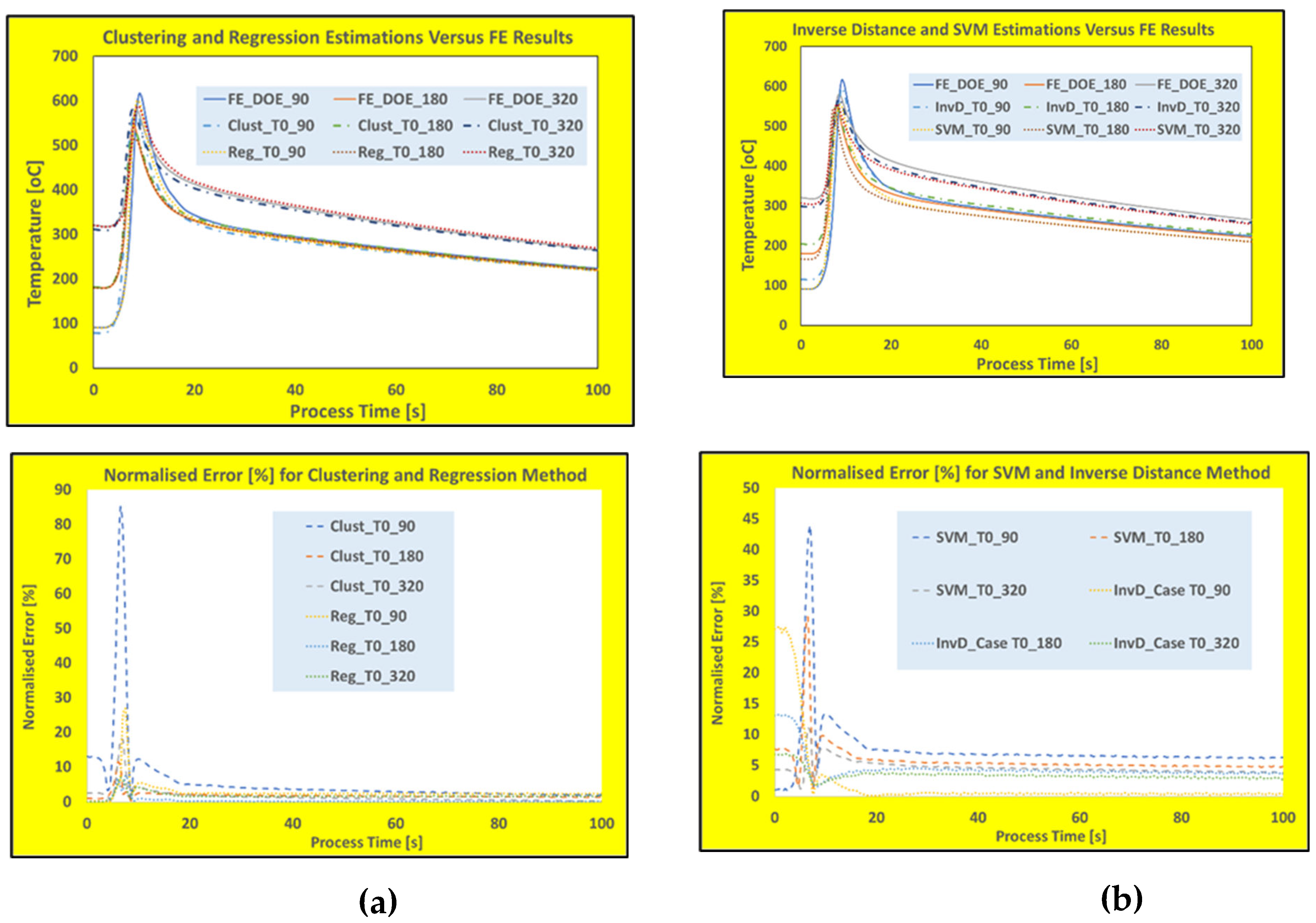

Figure 7 shows the time history temperature predictions along with normalized error plots for clustering, regression, InvD and SVM model building techniques.

As it is clearly demonstrated in

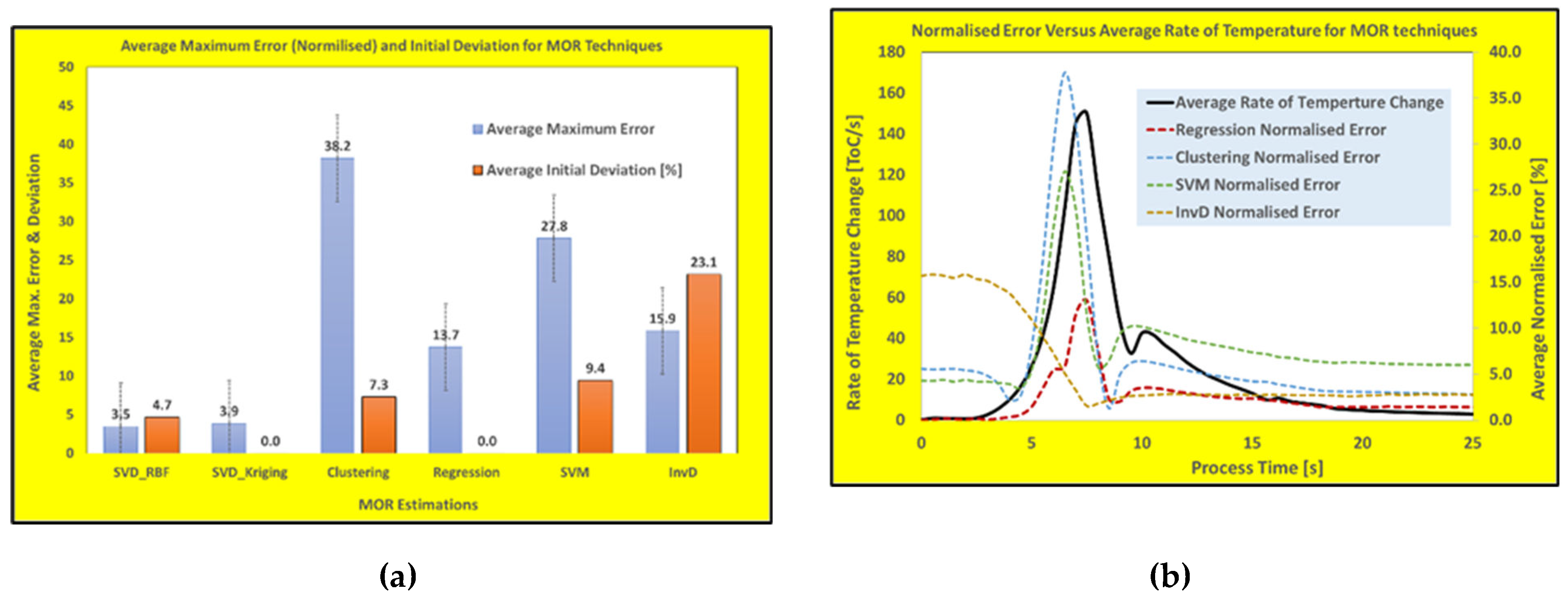

Figure 7, most of these popular reduced model techniques show either heating rate-dependency or inability to fit into the predefined initial conditions of the process (initial base temperature). The sampling rate for the thermal calculations of all these WAAM scenarios are half a second (2 Hz) with heating rate of up to 200 K/s which may increase the error margin for real-time predictions. Furthermore, the heating rate-dependency and deviation of initial temperatures are shown in

Figure 8a where average maximum errors (over three DOEs) and the deviation of initial conditions (in percentages) are plotted for all six methods (including trained SVD-RBF and SVD-Kriging methods). While

Figure 8b shows the time history of the average normalized errors (over three DOEs) with the calculated heating rates for the four popular model building techniques (for the first 25 seconds of the WAAM process).

As shown in these figures, the predictions based on these techniques show either some degree of heating rate-dependency or rather large deviation in predicting the initial thermal conditions. Both trained SVD-RBF and SVD-Kriging show superior overall performances with low maximum errors and limited or zero deviation at the initial thermal conditions. Besides these two techniques, the best performance can be gained by the regression method where relatively low rate-dependency and no deviation in the initial conditions were observed.

5. Conclusions

The reduced models and their fast and real-time prediction potentials can introduce an opportunity for further developments towards the digitalization of additive manufacturing processes. In this paper different reduced model building techniques have been examined to evaluate their performances for optimization and controlling of WAAM processes. At the start of the manuscript, a brief description of the numerical simulation techniques for these dynamic processes was presented and some technical aspects of the new evolving domain and dynamic mesh technique have shortly been elaborated. Furthermore, a brief mathematical description of the popular reduced model building techniques was presented and the impacts of hybrid ML-ROM trend on accuracy and reliability of the reduced models were discussed. In the following parts of the paper, ROM description of a practical case study for the WAAM process has been elaborated and its contagious concepts of accuracy, heat rate-dependency and thermal initial boundary conditions were examined.

At first sight, it can be observed that for the two developed SVD-RBF and SVD-Kriging methods, both the issues of heating\cooling rate-dependency and modelling of initial boundary conditions can to some degree be resolved. However, with further ML training (e.g., NN data training), it is also possible to achieve even better results for the high gradient heating\cooling processes where almost no rate-dependency can be observed in the predictions. Detailed investigations for the best performance “solver-interpolator” combinations have proved that some of the well-known solvers (e.g., SVD, POD, etc.) can produce more accurate results when they are employed with the right interpolating schemes. Furthermore, there is a possibility to use ML for training and improving data representations within the hybrid ML-ROM framework to achieve a superior accuracy and agility.

As a final statement, the intention in this paper is to encourage the use of ROM-ML schemes for the real-time modelling of dynamic material processes like WAAM. Although these hybrid reduced models are not intended to replace other experimental and\or detailed numerical process simulations, they can be valuable assets within the digitalization framework for controlling and optimizations. The opportunity to follow the hybrid modelling scheme for other multi-physical aspects of these processes like mechanical stress\strain and deformation\warping would be taken and this would be the subject for the future publications.

Funding

This research was funded by the Austrian Federal Ministry for Climate Action, Environment, Energy, Mobility, Innovation and Technology, the Austrian Research Promotion Agency (FFG) and the Austrian Institute of Technology under the UF2023 scheme.

Data Availability Statement

Sharing of data and reduced models generated in this research work may be considered upon request.

Acknowledgments

The author would like to thank the Austrian Federal Ministry for Climate Action, Environment, Energy, Mobility, Innovation and Technology, the Austrian Research Promotion Agency (FFG) and the Austrian Institute of Technology for the technical/financial support. The author would also like to thank, Hugo Drexler and Dr. Johannes Kronsteiner, both from LKR, Austrian Institute of Technology for their contributions in the research work.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflicts of interest.

References

- McBride, M.; Persson, N.; Reichmanis, E.; Grover, M.A. Solving Materials’ Small Data Problem with Dynamic Experimental Databases. Journal of Processes 2018, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perno, M.; Hvam, L.; Haug, A. Implementation of digital twins in the process industry: A systematic literature review of enablers and barriers. Computers in Industry 2022, 34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Favoretto, B.; de Hillerin, C.A.; Bettinotti, O.; Oancea, V.; Barbarulo, A. Reduced order modeling via PGD for highly transient thermal evolutions in additive manufacturing. Comp. Methods in App. Mech. and Eng. 2019, 349, 405–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horr, A.M. Optimization of Manufacturing Processes Using ML-Assisted Hybrid Technique. J. of Manuf. Letters 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horr, A.M.; Drexler, H. On Reduced and Detailed Simulations of Additive Manufacturing Processes. In Proceedings of the MAMC2022, Graz, Austria, 2022; https://submit.asmet.org/event/63/book-of-abstracts.pdf.

- Horr, A.M. Notes on New Physical & Hybrid Modelling Trends for Material Process Simulations. Journal of Physics: Conference Series 2020, 1603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baiges, J.; Chiumenti, M.; Moreira, C.A.; Cervera, M.; Codina, R. An adaptive Finite Element strategy for the numerical simulation of additive manufacturing processes. Additive Manufacturing 2021, 37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patil, N., Pal D., Stucker B., A New Finite Element Solver using Numerical Eigen Modes for Fast Simulation of Additive Manufacturing Processes, International Solid Freeform Fabrication Symposium, 2013. [CrossRef]

- Lindgren, L.E.; Lundbäck, A. Approaches in computational welding mechanics applied to additive manufacturing: Review and outlook. Comptes Rendus Mécanique 2018, 346, 1033–1042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brötz, S.; Horr, A.M. Framework for progressive adaption of FE mesh to simulate generative manufacturing processes. J. of Manuf. Letters 2020, 24, 52–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Setien, I.; Chiumenti, M.; Veen, S.; San Sebastian, M.; Garciandía, F.; Echeverría, A. Empirical methodology to determine inherent strains in additive manufacturing. Computers & Mathematics with Applications 2019, 78, 2282–2295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, H.; Ma, N.; Chen, J.; Feng, Z.; Murakawa, H. Toward large-scale simulation of residual stress and distortion in wire and arc additive manufacturing. Additive Manufacturing 2020, 34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michaleris, P. Modeling metal deposition in heat transfer analyses of additive manufacturing processes. Finite Elements in Analysis and Design 2014, 86, 51–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horr, A.M.; Kronsteiner, J. Dynamic material process simulations: Hybrid-evolving technique. Journal of Metals 2021, 11, 1884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Denlinger, E.R.; Irwin, J.; Michaleris, P. Thermomechanical Modeling of Additive manufacturing Large Parts. ASME. J. Manuf. Sci. Eng. 2014, 136, 061007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gouge, M.; Michaleris, P.; Denlinger, E.; Irwin, J. The Finite Element Method for the Thermo-Mechanical Modeling of Additive Manufacturing Processes. In Thermo-Mechanical Modeling of Additive Manufacturing; Gouge, M., Michaleris, P., Eds.; Butterworth-Heinemann, 2018; pp. 19–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Q.; Zhang, P.; Cheng, L.; Min, Z.; Chyu, M.; To, A.C. Finite element modeling and validation of thermomechanical behavior of Ti-6Al-4V in directed energy deposition additive manufacturing. Additive Manufacturing 2016, 12 Pt B, 169–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horr, A.M. Computational Evolving Technique for Casting Process of Alloys. Math. Prob. in Eng. 2019, 6164092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strobl, D.; Robens-Radermacher, A.; Ghnatios, C.; Pittner, A.; Rethmeier, M.; Unger, J.F. PGD model with domain mapping of Bead-on-Plate weld simulation for wire arc additive manufacturing. In Proceedings of the 8th Eur. Cong. on Comput. Methods in App. Sci. and Eng. (ECCOMAS), Oslo, Norway, 2022; https://opus4.kobv.de/opus4-bam/frontdoor/index/index/docId/55111.

- Quaranta, G. Efficient simulation tools for real-time monitoring and control using model order reduction and data-driven techniques. Tesi doctoral, UPC, Departament d'Enginyeria Civil Ambiental, 2019. https://hdl.handle.net/2117/168567.

- Lu, Y.; Jones, K.K.; Gan, Z.; Liu, W.K. Adaptive hyper reduction for additive manufacturing thermal fluid analysis. Comp. Methods in App. Mech. and Eng. 2020, 372, 113312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korneev, S.; Wang, Z.; Thiagarajan, V.; Nelaturi, S. Fabricated shape estimation for additive manufacturing processes with uncertainty. Computer-Aided Design 2020, 127, 102852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brunton, S.L.; Kutz, J.N. Data Driven Science & Engineering - Machine Learning, Dynamical Systems, and Control; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, England, 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, J.; Hu, F.; Liu, Y.; Witherell, P.; Wang, C.L.; Rosen, D.W.; Simpson, T.W.; Lu, Y.; Tang, Q. Research and application of machine learning for additive manufacturing. Additive Manufacturing 2022, 52, 102691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wagner, S.; Affenzeller, M. HeuristicLab: A generic and extensible optimization environment. In Proceedings of the Adaptive and Natural Computing Algorithms; Springer, 2005; p. 538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ash, T. Dynamic Node Creation in Backpropagation Networks. Connection Science 1989, 1, 365–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).