1. Introduction

The inherent complexity of biological systems—characterized by interconnected subsystems and nonlinear dynamics— presents enduring challenges for effective bioprocess monitoring and control. Mathematical modeling offers a powerful means to capture and manage this complexity [

1]. Over the past few decades, such models have become indispensable in understanding and optimizing bioprocesses, benefiting from advances in computational capabilities and analytical tools. This progress has led to the adoption of advanced modeling approaches, such as genome-scale metabolic models and computational fluid dynamics simulations [

2,

3]. With the advent of Industry 4.0, modeling has taken on an even more prominent role in the digital transformation of biomanufacturing [

4]. However, the limitations of mechanistic models—particularly their reliance on complete system knowledge—have prompted interest in alternative strategies. As a result, machine learning techniques are gaining traction, offering flexible, data-driven alternatives that can extract insights without relying on fully defined system knowledge—supporting next-generation bioprocess digitalization [

5,

6,

7,

8].

To bridge this gap, hybrid neural network (HNN) models have emerged as a compelling solution, integrating domain knowledge with data-driven flexibility [

9,

10,

11,

12,

13,

14]. These models combine the structure of mechanistic frameworks (e.g., mass or energy balances) with the flexibility of data-driven components such as ANNs, effectively leveraging both physical laws and empirical data [

15,

16]. A typical use case involves modeling unknown or complex kinetics using neural networks within a differential equation-based framework. Compared to purely nonparametric models, hybrid approaches often yield more accurate, generalizable, and interpretable results—leading to more robust bioprocess operation and control [

17]. The recent surge in deep learning methodologies has further enhanced hybrid modeling by enabling neural networks to approximate intricate biological functions, as deep neural networks (DNNs) with multiple hidden layers have demonstrated superior capacity for learning hierarchical and compositional functions with fewer parameters and reduced sample complexity compared to shallow architectures [

9,

10,

18]. As such, hybrid deep learning models are emerging as a powerful tool in the development of digital twins and advanced bioprocess monitoring systems.

In parallel, deep learning developments have expanded modeling capabilities across bioprocess applications. DNNs, through their multilayered architectures, enable the extraction of hierarchical and compositional features, allowing for the accurate approximation of highly nonlinear biological dynamics [

18,

19]. These models have demonstrated strong performance across a range of bioprocessing tasks, including soft sensing, anomaly detection, forecasting, and system identification, particularly when applied to high-resolution data streams generated by modern process analytical technologies (PAT). Long Short-Term Memory (LSTM) networks, designed to retain temporal context over extended time horizons, have proven especially valuable for modeling dynamic bioreactor cultivations. When coupled with mechanistic models, LSTMs form powerful hybrid frameworks capable of accurately capturing both short-term variability and long-term process trends [

11]. Critical to the effective training of such deep architectures are modern optimization and activation strategies: the rectified linear unit (ReLU) activation function addresses vanishing gradient problems, while the Adaptive Moment Estimation (Adam) optimizer accelerates convergence and enhances generalization through adaptive learning rate adjustments [

10,

20]. Collectively, these innovations position deep hybrid modeling as a central enabler of next-generation digital twins for real-time monitoring, control, and optimization in biomanufacturing.

However, training deep models requires extensive, high-frequency datasets that are often unavailable in bioprocessing due to high costs, long cultivation times, and sensor limitations [

21]. In early-stage bioprocess development or pilot-scale operations, datasets typically contain only a small number of replicates per condition, resulting in limited coverage of the process space and insufficient diversity to support generalizable deep models [

22]. Bioprocess data is typically noisy, heterogeneous, and expensive to generate, posing a major bottleneck for training deep architectures. Such data limitations have accelerated the adoption of hybrid modeling frameworks, which leverage both prior process knowledge and empirical data. The promising approach of integrating historical process data through transfer learning frameworks can significantly improve prediction accuracy and reduce the need for extensive new experimental data [

23,

24].

Transfer learning (TL) in deep neural networks involves repurposing a model trained on a source task to enhance learning on a related target task, especially when labeled data are scarce. By leveraging pre-trained models—often developed on large, generic datasets—TL facilitates improved convergence speed, generalization, and computational efficiency compared to training from scratch [

25,

26]. In bioprocess engineering, TL enables the adaptation of models trained on well-characterized systems to predict dynamics in novel or data-limited processes. For instance, TL has been successfully applied to model microalgal bioprocess dynamics using limited time-series data, achieving high accuracy in forecasting process behavior [

27] and for the quantification and identification of cellular phenotypes from high-content microscopy images [

28].

Despite its advantages, TL poses challenges such as negative transfer, which occurs when source and target domains are insufficiently aligned, and catastrophic forgetting during fine-tuning [

29]. Effective transfer requires careful selection of source models, layer-freezing strategies, and learning rate tuning to preserve useful features while adapting to the new task. In bioprocess applications, these considerations are critical due to the heterogeneity of biological systems and the frequent lack of large annotated datasets. Nevertheless, TL remains a promising strategy—especially when combined with hybrid modeling approaches that integrate mechanistic insights with data-driven learning [

30].

Deep neural network architecture screening typically involves systematic strategies to identify optimal model configurations and hyperparameters. Common methods include grid search, which exhaustively evaluates combinations within a predefined parameter grid [

31]. While easy to implement and parallelize, grid search becomes computationally expensive as the number of hyperparameters increases. Random search improves efficiency by sampling configurations at random, often outperforming grid search in high-dimensional spaces where only a few parameters significantly affect performance [

31]. A more advanced and efficient approach is Bayesian optimization, which builds a probabilistic surrogate model (e.g., Gaussian Process) to predict performance and selects promising configurations using acquisition functions like Expected Improvement [

32]. This strategy significantly reduces the number of required evaluations and is especially valuable when model training is computationally costly. Several studies confirm that Bayesian optimization typically outperforms traditional approaches in terms of sample efficiency and final model performance [

31,

32].

As the dominant production mode, fed-batch fermentation remains widely used due to its robustness and high product yields, with most biotherapeutics in clinical and commercial use produced using this mode [

33,

34]. However, maintaining optimal substrate feeding remains a major challenge, requiring precise control to ensure consistent performance. Model Predictive Control (MPC) has emerged as a powerful strategy to address this, leveraging predictive models to optimize feeding decisions in real time [

35,

36]. Yet, the nonlinear and dynamic nature of high cell density fermentations often limits the accuracy of purely mechanistic models, as parameter estimation and unforeseen biological interactions degrade model reliability [

33,

37]. Hybrid modeling strategies help mitigate these challenges by improving parameter adaptability, accounting for process nonlinearities, and enhancing real-time prediction accuracy [

38]. Integrating hybrid bioreactor process models with MPC enhances the optimization and control of bioprocesses, particularly in complex systems like high cell density fermentations, resulting in improved modelling accuracy, increased adaptability to changing process conditions and real-time feed-back for increased process stability [

39,

40,

41].

The selection of an appropriate expression system is a critical factor in recombinant protein production, as it directly influences yield, functionality, and downstream processing. Among the various platforms available, the methylotrophic yeast

Pichia pastoris has emerged as a preferred host over the past two to three decades for both research and industrial applications. It offers several advantages, including ease of genetic manipulation, high transformation efficiency, and the ability to achieve high protein titers both intracellularly and extracellularly [

42,

43]. Furthermore,

P. pastoris supports essential eukaryotic post-translational modifications such as glycosylation, disulfide bond formation, and proteolytic processing, making it well-suited for producing complex proteins. Its minimal native protein secretion simplifies purification, and its capacity for rapid growth in defined media, along with robust genetic tools and stable expression over extended cultivation periods, strengthens its suitability for scalable production. These characteristics along with growing interest in digital bioprocessing, make

P. pastoris a strong candidate for hybrid model development and advanced biomanufacturing strategies [

44,

45].

The Qβ coat protein virus-like particles (VLPs) are self-assembling, non-infectious nanostructures derived from the bacteriophage Qβ. These VLPs have garnered significant attention in biomedicine due to their uniform size, stability, and ability to present antigens in a repetitive, high-density manner, which is highly effective in eliciting strong immune responses. Notably, Qβ VLPs have been successfully utilized in vaccine development [

46,

47]. Furthermore, their versatility allows for the encapsulation of various cargos, making them valuable in drug delivery and nanotechnological applications. Qβ VLPs can be efficiently produced in

P. pastoris, a widely used yeast expression system, which offers high-yield, cost-effective recombinant protein production with proper protein folding and scalability for biopharmaceutical applications [

48].

Recent work has explored hybrid modeling in recombinant

P. pastoris cultivations, demonstrating performance gains in process control, generalization, and scalability. Ferreira

et al. used a serial HNN, consisting of a three-layer feedforward neural network (FFNN) combined with material balance equations, for dynamic modeling of

P. pastoris GS115 expressing scFv in a 50 L pilot bioreactor. This hybrid model was then applied for iterative batch-to-batch control, resulting in a 4-fold increase in titer after four optimization cycles [

12]. Pinto

et al. revisited the general bioreactor hybrid model and introduced deep learning techniques. Multi-layer networks with varying depths were combined with First Principles equations to form deep hybrid models. Techniques like ADAM, stochastic regularization, and depth-dependent weight initialization were evaluated in this context. The methods were applied to a synthetic

E. coli dataset and a 50 L Mut

+ P. pastoris process expressing a single-chain antibody fragment. Results showed significant improvements in generalization, with an 18.4% increase in prediction accuracy and a 43.4% reduction in CPU time compared to shallow models [

10]. In another study, Pinto

et al. developed a hybrid deep modeling method with state-space reduction, applied to a

P. pastoris GS115 Mut

+ strain expressing scFv. Deep FFNNs of varying depths were combined with bioreactor material balance equations and trained using ADAM, semidirect sensitivity equations, and stochastic regularization. A state-space reduction method, based on principal component analysis (PCA) of the cumulative reacted amount, reduced model complexity by 60% and improved predictive accuracy by 18.5%. Validation with data from nine fed-batch

P. pastoris 50 L cultivations highlighted optimization opportunities, with potential increases in scFv titer of 30% and 80% by optimizing methanol feed and inorganic elements, respectively [

9].

This study presents a hybrid deep learning model tailored to recombinant P. pastoris fermentations, trained using a transfer-learning approach of historical and newly acquired batch data, incorporating both at-line and in-line biomass measurements. The model architecture integrates mechanistic knowledge with data-driven components to effectively capture the complex dynamics of the fermentation process. The resulting model is integrated into a novel Model Predictive Control framework, enabling adaptive feeding strategies and dynamic trajectory tracking. We validate the approach through an experimental fermentation run, showcasing improved control precision and enhanced process stability.

2. Materials and Methods

Experimental conditions

Cultivations were performed using a recombinant

Pichia pastoris X-33 wild-type strain producing Qβ coat protein VLPs. The construction of the expression vector and the selection of clones for this specific producer are described in detail elsewhere [

48].

The batch and feed media formulations were prepared following the “Pichia Fermentation Process Guidelines” provided by Invitrogen Corporation [

49]: 1.9 L of Basal Salts Medium (26.7 mL·L

−1 H

3PO

4 85%, 0.93 g·L

−1 CaSO

4, 18.2 g·L

−1 K

2SO

4, 14.9 g·L

−1 MgSO

4·7H

2O, 4.13 g·L

−1 KOH, 40.0 g·L

−1 glycerol and 4.35 mL·L

-1 PTM

1 trace element solution (0.02 g·L

−1 H

3BO

4, 5 mL·L

−1 H

2SO

4 98%, 6.0 g·L

−1 CuSO

4·5H

2O, 0.08 g·L

−1 NaI, 3.0 g·L

−1 MnSO

4·H

2O, 0.2 g·L

−1 Na

2MoO

4·2H

2O, 0.5 g·L

−1 Ca

2SO

4·2H

2O, 20.0 g·L

−1 ZnCl

2, 65.0 g·L

−1 FeSO

4·7H

2O, 0.2 g·L

-1 biotin)), was inoculated with 100 mL of inoculum grown in BMGY medium (10.0 g·L

-1 yeast extract, 20.0 g·L

-1 peptone, 100 mM potassium phosphate buffer, pH 6.0, 13.4 g·L

-1 yeast nitrogen base, 10.0 g·L

-1 glycerol, 0.0004 g·L

-1 biotin) at 30°C for 18-22 h in a shake flask at 250 RPM. Two feeding solutions were used: a glycerol feed consisting of 50% v/v glycerol and 12 mL·L⁻¹ PTM1, and a methanol fed-batch solution composed of 100% methanol with 12 mL·L⁻¹ PTM1.

The bioreactor vessel was filled with distilled water and sterilized at 121 °C for 30 minutes. BSM, BMGY, and the glycerol fed-batch solutions were autoclaved separately under the same conditions. The PTM1 trace element solution was sterilized by filtration using a 0.2 µm membrane filter.

Fermentations were carried out in a 5 L bench-top bioreactor (Bioreactors.net, EDF-5.4/BIO-4, Latvia) with a working volume of 2–4 L, as illustrated in

Figure 2. The pH was continuously monitored using a calibrated pH probe (Hamilton, EasyFerm Bio, Switzerland) and adjusted to 5.0 ± 0.1 with a 28% NH₄OH solution prior to inoculation, then maintained at this value throughout the process. Temperature was regulated at 30.0 ± 0.1 °C using a temperature sensor and jacketed vessel control. A thermostatic circulator (LKB Bromma, Multitemp II, Sweden) maintained the cooling water at a preset temperature of 6 °C during experiments.

Dissolved oxygen (DO) levels were measured using a DO sensor (Hamilton, Oxyferm Bio, Switzerland) and maintained above 30 ± 5% via a dual cascade strategy: adjusting the stirrer speed between 200–1000 RPM (Cascade 1), and supplementing the inlet air with pure O₂ when necessary (Cascade 2). A constant airflow or air/oxygen mixture at 3.0 slpm was sustained throughout the fermentation. A condenser was employed to capture moisture from exhaust gases, and Antifoam 204 (Sigma) was added as needed to suppress excessive foam formation. Substrate feeding was controlled with a high-precision peristaltic pump (Longer-Pump, BT100–2J, China).

The cultivations began with a glycerol batch phase. After 18–20 hours, once the batch glycerol was depleted, a glycerol fed-batch phase was initiated by feeding the reactor with a glycerol solution at a rate of 0.61 mL·min⁻¹ for 4 hours, or until an optical density (OD) of 100–120 was reached. Following a short feeding pause of 5–20 minutes—allowing the cells to consume any residual glycerol—the substrate was switched to methanol. Methanol feeding proceeded in three phases: initially at 0.12 mL·min⁻¹ for 5 hours, then at 0.24 mL·min⁻¹ for 2 hours, and finally at 0.36 mL·min⁻¹, which continued either until the end of the experiment or for 2–3 hours until the hybrid MPC control was activated.

In experiments where real-time biomass concentration was monitored using an

in-situ turbidity probe (Optek-Danulat, ASD19-EB-01, Germany), the turbidity signal was correlated with biomass concentration using an exponential calibration equation reported previously [

50]. To enhance signal reliability, an algorithm was implemented to correct for abrupt spikes caused by sudden process disturbances. The details of this algorithm are provided in a separate publication [

51].

Although the cultivation conditions were generally similar across all historical experiments, some minor differences were present. For detailed information on these variations, as well as the construction of the expression vectors and clone selection, we refer the reader to the original publications [

44,

52].

Downstream processing of Qβ VLPs

4.0 g of wet cells were resuspended in 20 mL of lysis buffer (20 mM Tris 8.0, 100 mM NaCl) and disrupted by French press (4x 10,000 psi). The suspension was then centrifuged for 30 min at 18,500 g (4°C). Ammonium sulfate was added to the supernatant to 40% saturation and proteins precipitated at 4°C for 60 minutes. The suspension was then centrifuged for 20 min at 18,500 g (4°C) and the supernatant discarded. Precipitate was dissolved in 20 mM Tris 8.0 buffer and loaded onto Sepharose 4 Fast Flow size-exclusion column (12 mL volume) in lysis buffer at 0.3 mL/min. Peak fractions were pooled and loaded onto anion-exchange Fractogel DEAE (M) column (5 mL volume) in lysis buffer and eluted with a linear gradient of 20 mM Tris-HCl, 1 M NaCl pH 8.0 at 2 mL/min.

Analytical measurements

Cell growth was observed by off-line measurements of dry cell weight (DCW), determined gravimetrically. Biomass samples were placed in pre-weighted Eppendorf

® tubes and centrifuged at 15’500 g for 5 minutes. Afterwards, the supernatant was discarded and the remaining wet cell biomass weighted. DCW was calculated using a previously determined correlation coefficient

Protein samples taken during cultivation were analysed using sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS–PAGE), with a 5% stacking and 15% separating polyacrylamide gel (PAAG), according to standard protocols. To visualize the separated protein bands, the gels were stained with 0.4% Coomassie Brilliant Blue G-250 dye.

Dataset for hybrid model training

The characteristics of the dataset of

P. pastoris fermentation data used for the hybrid model training is compiled in

Table 1.

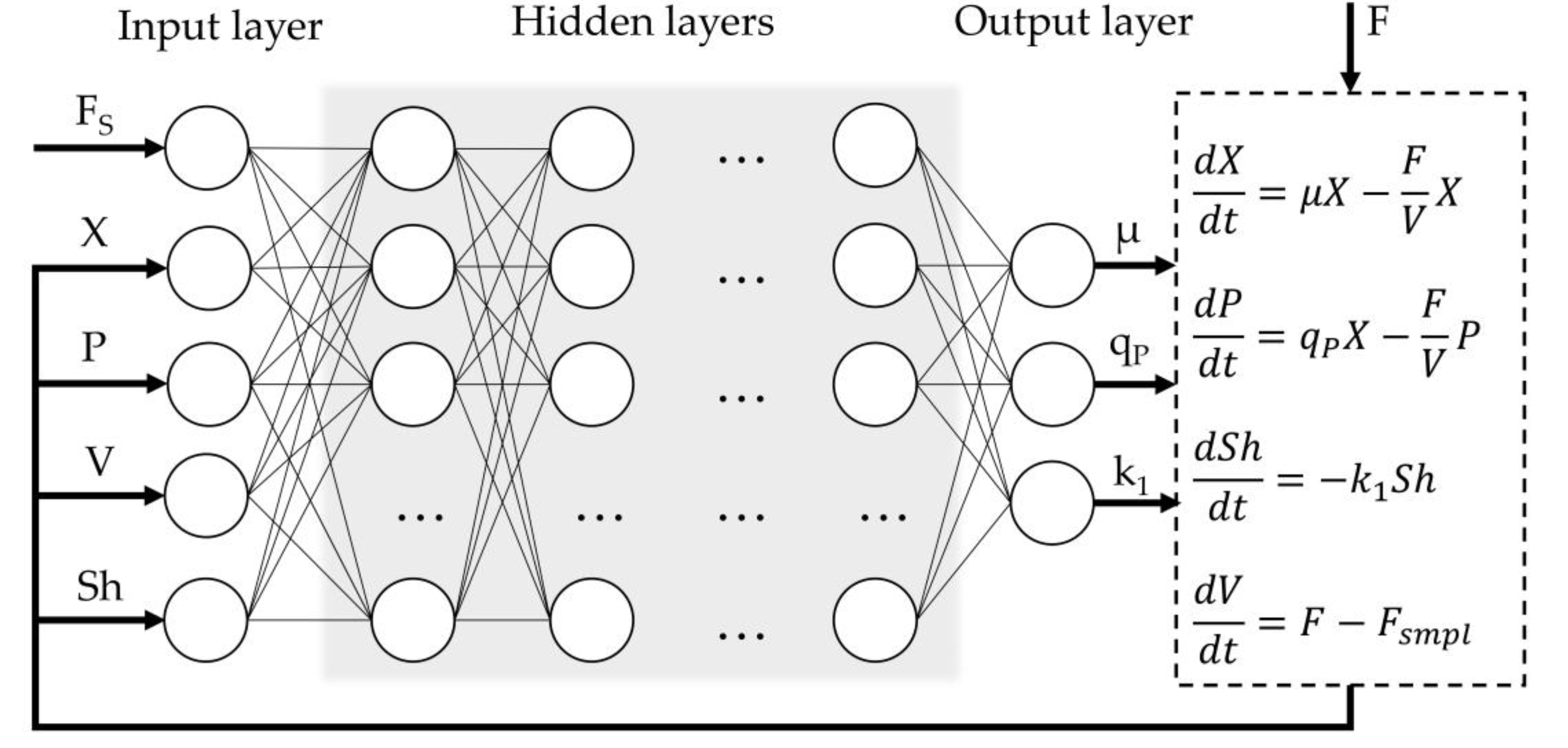

Hybrid process model structure and training

The general structure of the hybrid process model is illustrated in

Figure 1. The input layer comprises five variables: substrate feed rate (Fs, mL·min⁻¹), dry cell biomass concentration (X, g·L⁻¹), product concentration (P, mg·L⁻¹), culture medium volume (V, L), and an empirical shock factor (Sh) representing the cumulative toxic effect of methanol on the cells. To enhance model training efficiency and convergence, the sequence input layer incorporates normalization of the input features by scaling each sequence sample to the [0, 1] range using the minimum and maximum values computed over the entire dataset The output layer provides three variables: the specific cell growth rate (µ, h⁻¹), production rate (q

P, h⁻¹), and the rate of change of the shock factor (k₁). The optimal composition of hidden layer structure was investigated in further steps.

The outputs of the non-parametric model are then passed to the parametric component, which captures the dynamics of the state variables using a system of ordinary differential equations (ODEs) derived from macroscopic and/or intracellular material balances, as well as other relevant physical assumptions. The only external inputs to the model are the aforementioned substrate feed rate (Fs) and the volumetric flow rate (F), which is calculated by the following equation

where F

b and F

AF are the added base and antifoam solution flow rates (mL·min⁻¹) and F

evp is the determined culture evaporation rate (0.11 mL·min⁻¹).

The loss function was defined as normalized root mean square error (NRMSE):

where

n is the number of training samples,

yi represents the measured values,

yi* is the corresponding predicted variables, and

ymin and

ymax denote the minimum and maximum values for the dataset, respectively.

To fully utilize the real-time cell biomass sensor data, each process dataset was segmented into 60 equally spaced batches using an interleaved batching approach. Given a time-series dataset consisting of N total time points {

t1, t2, …, tN} and a chosen number of segments

k = 60, each batch

Bj (for

j = 1, 2, …, 60) was constructed by selecting every

k-th time point starting from offset

j. This can be expressed mathematically as:

This approach ensures that each batch contains a temporally distributed subset of the full dataset, preserving temporal variability and aiding in model generalization. For instance, Batch 1 contains {t1, t61, t121, …}, Batch 2 includes {t2, t62, t122, …} and so on, up to Batch 60. Because time-series data were recorded at one-minute intervals, this batching scheme effectively introduced a consistent 60-minute gap between successive data points within each batch. As a result, it enabled the estimation of average dynamic rates (e.g., biomass growth or product formation) on an hourly basis—an appropriate timescale for bioprocess interpretation and modeling. This method is particularly suitable for sequence-based machine learning models, as it ensures a diverse temporal representation in each training segment.

In experiments where only sparse experimental measurements were available, interpolation was necessary to ensure that each segmented batch contained the corresponding measurement values at the correct time points. To achieve this, piecewise cubic Hermite interpolating polynomial (PCHIP) interpolation was applied to the time-series data. This approach generated estimated values at all necessary time points, thereby ensuring that each batch contained a continuous and temporally consistent signal aligned with the original, sparsely sampled experimental measurements. Importantly, to preserve the integrity of model evaluation, NRMSE was computed only at the original measurement time points, ensuring that model performance was assessed strictly against experimentally observed data rather than interpolated estimates.

Prior to model training, a validation dataset was created by randomly selecting 10% of the original time-series data. Specifically, six batches were sampled from each fermentation experiment to form the validation partition. This subset was held out during training and used exclusively to monitor model performance, assess generalization to unseen data and as an early-stopping criterion for training.

The hybrid process model was trained using the Adaptive Moment Estimation (ADAM) optimization algorithm, which combines the advantages of both momentum-based and adaptive learning rate methods [

20]. The optimizer was configured with standard recommended parameters: an initial learning rate

α0 = 0.001, first moment decay rate

β1 = 0.9, second moment decay rate

β2 = 0.999, and a small numerical stability constant

ε = 10

−8. To facilitate stable convergence and mitigate overfitting, an exponential learning rate decay strategy was employed, where the learning rate was gradually decreased every 100 epochs from 0.001 to 0.0001 by a calculated decay factor over the course of training, as per the formula:

where,

α(t) is the learning rate at epoch

t and the learning rate decay factor γ = 0.9007.

This gradual decay enabled the model to make larger updates early in training and finer adjustments in later stages, facilitating both rapid convergence and precise parameter tuning. Each epoch, the training dataset was randomly shuffled and divided into six minibatches to support optimization using the ADAM algorithm. This randomization reduced the risk of learning spurious temporal or sequential dependencies and enhanced generalization. The use of minibatches, combined with ADAM’s adaptive learning rate mechanism further improved training efficiency and convergence reliability.

Hybrid model training was performed using a custom training script developed in the MATLAB environment (MathWorks, R2024b, USA), leveraging the Deep Learning Toolbox. Training was conducted on a personal computer equipped with an Intel i5-6600 CPU (3.30–3.90 GHz) and 16 GB of RAM. The training script was parallelized to enable simultaneous training of multiple networks. For parallel training tasks, the High-Performance Computing (HPC) cluster of Riga Technical University (RTU) was utilized in conjunction with the personal computer.

Hybrid model architecture screening

To efficiently identify the optimal hidden layer architecture for the hybrid model, a multi-step strategy was implemented. First, a Bayesian optimization approach was employed. This method systematically explores the hyperparameter space by building a probabilistic model of the objective function, enabling informed and efficient searches for the best-performing network configurations with fewer training iterations compared to traditional grid or random search methods.

To accelerate the screening process, networks were trained in parallel for a limited duration of 10 epochs (corresponding to 90 iterations) using an elevated initial learning rate of

α0 = 0.01. This higher learning rate was chosen to promote faster convergence during early training, enabling quicker identification of promising model architectures without the need for extensive training. Only historical experimental data (Exps. 1-17) was used in this step, to ensure the model adapted its parameters based on well-established process dynamics before being fine-tuned with the new Qβ dataset, thereby improving generalization and robustness during transfer learning. Validation loss was used as the primary performance criterion during the grid search, as it provides a more reliable measure of the model’s ability to generalize to unseen data and helps prevent the selection of overfitted architectures. Corrected Akaike information criterion (AICc) was used alongside validation loss as a performance criterion to account for model complexity, ensuring that selected architectures not only fit the data well but also avoid overparameterization, which can hinder generalization:

where

k is the number of model parameters,

L is the loss function value (NRMSE, %), and

n is the number of observations (sample size).

For the initial optimization phase, several key hyperparameters were selected to systematically investigate their impact on model performance. These included the choice of the first hidden layer type—either LSTM or fully connected (FC). The number of subsequent fully connected layers was varied between one and two to assess the effect of network depth. Additionally, the activation functions within the fully connected layers were optimized, considering options such as ReLU, Leaky ReLU(0.01), Tanh, or no activation, to evaluate how different nonlinearities affect learning. Finally, the number of hidden units or nodes in each layer was explored within a range of 1 to 5, enabling fine-grained control over model capacity and complexity. This amounts to 8,000 possible parameter combinations. The Bayesian optimization algorithm was executed 10 times, each run consisting of 200 iterations. The best-performing model architecture with the lowest validation loss from each run was saved for further evaluation.

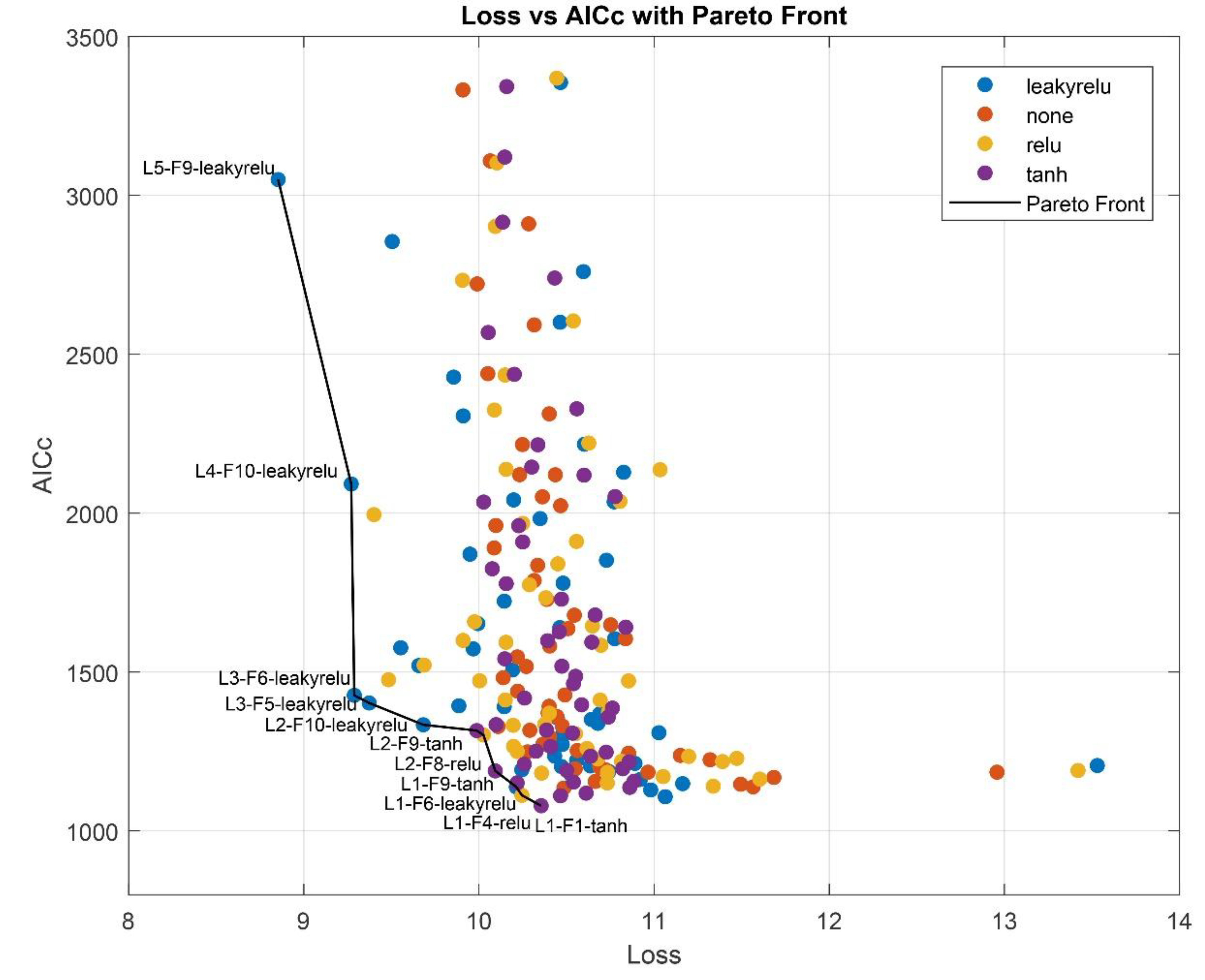

In the second step, the scope of the parameter search was narrowed to focus on the activation function (ReLU, Leaky ReLU, Tanh, or none), the number of LSTM hidden units (ranging from 1 to 5), and the number of fully connected layer nodes (ranging from 1 to 10). The upper limit for LSTM hidden units was intentionally kept low to prevent overparameterization, as each additional LSTM unit substantially increases the total number of trainable parameters. In contrast, the number of FC layer nodes was expanded up to 10 based on favorable results observed in the previous optimization step, where larger FC layers contributed to improved model performance without incurring excessive computational cost. With only 200 possible combinations, a full grid search was conducted during the second screening step. Each network architecture was evaluated across 10 training runs, and only the best-performing candidate was retained for each parameter combination. To balance validation loss with model complexity and mitigate overparameterization, a loss vs. AICc plot was generated to identify the Pareto front (

Figure A1). From this front, five network architectures that best balanced low validation loss and favorable AICc values were selected for further evaluation.

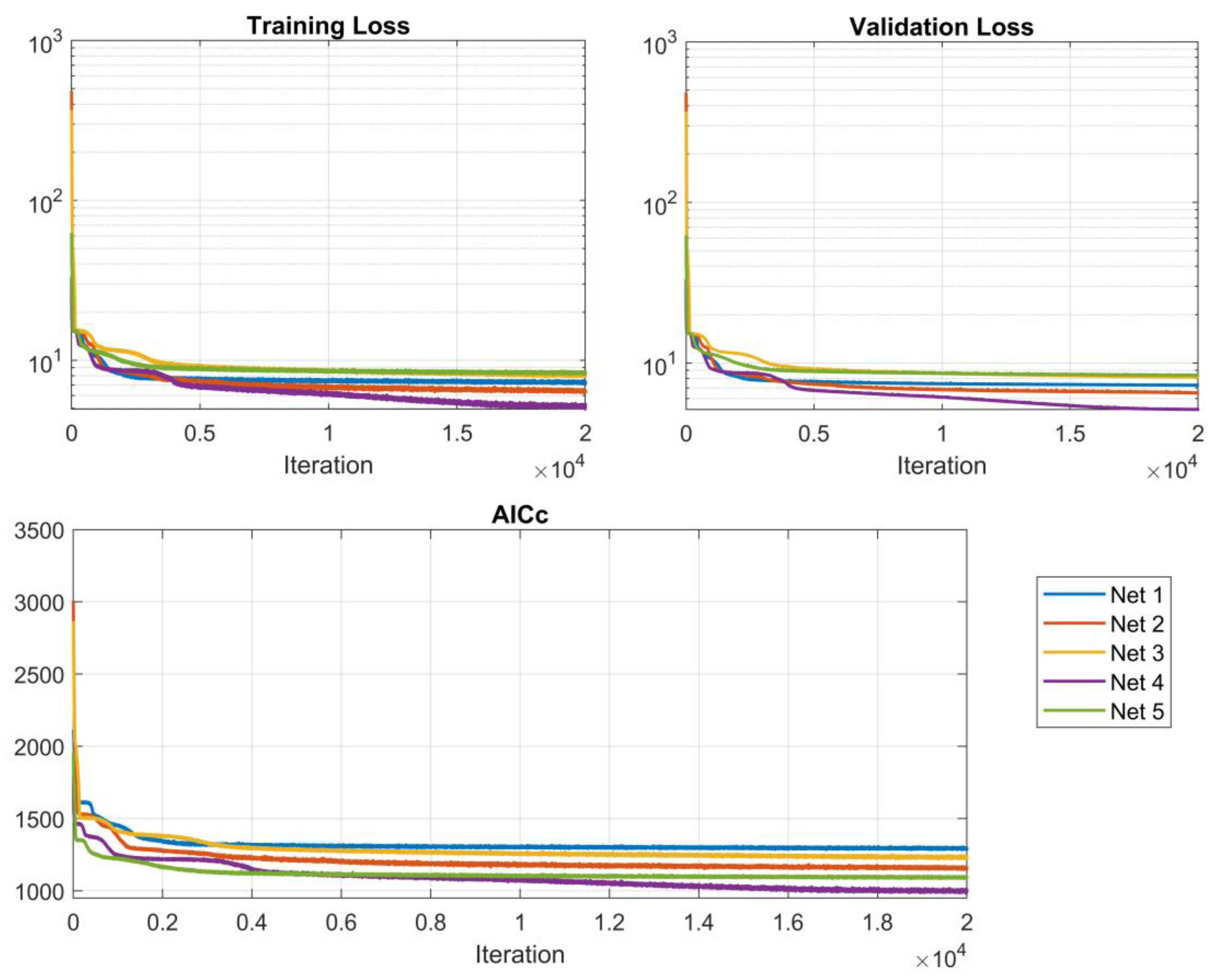

In the third step, the selected models were trained in full for 20,000 iterations, and their predictive performance was assessed using validation loss. The best-performing model was chosen as the optimal network configuration for the specific hybrid process model. Finally, the impact of incorporating a dropout layer within the finalized hybrid model architecture was thoroughly investigated to assess its effect on model robustness and generalization performance.

Hybrid model transfer learning

To leverage the selected trained hybrid model for a new experimental dataset involving Qβ production, a transfer learning approach was applied. The previously optimized model architecture, trained on the historical dataset, served as the starting point. All model weights were initialized from this pre-trained network to retain learned temporal and process dynamics. To adapt the model to the Qβ dataset, only the final fully connected layer was unfrozen and fine-tuned using the new data, while the LSTM unit—capturing general process behavior—was kept fixed. This strategy allows the model to efficiently adapt to the specific characteristics of the Qβ process while preserving useful generalizations from the original training, thereby reducing training time and improving predictive accuracy with limited new data. Experiment 20 was used for testing loss calculation.

Model Predictive Control (MPC) architecture

A comprehensive model predictive control framework was developed and implemented, leveraging the advanced hybrid process model. The main task of the MPC controller was to track a pre-selected growth trajectory close to the maximum specific growth rate of the cells.

The MPC algorithm was implemented to dynamically estimate the optimal substrate feed rate,

Fₛ(t), required to maintain a desired specific growth rate,

μₛₑₜ(t). In the developed hybrid modeling framework, the substrate feed rate served as an input, while the specific growth rate was one of the predicted outputs. Due to the non-invertible structure of the hybrid model, analytical inversion to compute

Fₛ(t) from a given

μₛₑₜ(t) was not feasible. Consequently, a numerical optimization approach was employed at each control step using MATLAB’s bounded nonlinear optimization function

fminbnd, which searched for the optimal feed rate within specified operational constraints. The optimization problem at each time step was formulated as:

subject to the hybrid model dynamics:

where

x(k) is the vector of the state variables, and

μ(k) is the predicted specific growth rate at step

k. The control horizon was set to

Nc = 1 hour and the prediction horizon to

Np = 12 hours. The hybrid model itself was simulated with a finer sampling time of 1 minute to ensure accurate forward predictions, while the MPC made decisions on an hourly basis.

To improve model accuracy and adaptability, the hybrid model was retrained after each sampling (approx. three times per day). Each time, the newly measured biomass concentration, Xmeas(t), was appended to the training dataset, and the model parameters were updated to reflect the latest process dynamics.

The MPC framework was experimentally validated in a

P. pastoris fed-batch fermentation under the methanol-inducible AOX1 promoter. Real-time process data, including substrate feed rate, base and antifoam addition, were integrated into MATLAB via an OPC server, enabling seamless bidirectional communication with the SCADA system. A more technical description is available elsewhere [

33]. This real-time data integration allowed the MPC to adjust the substrate feed rate based on actual process conditions.

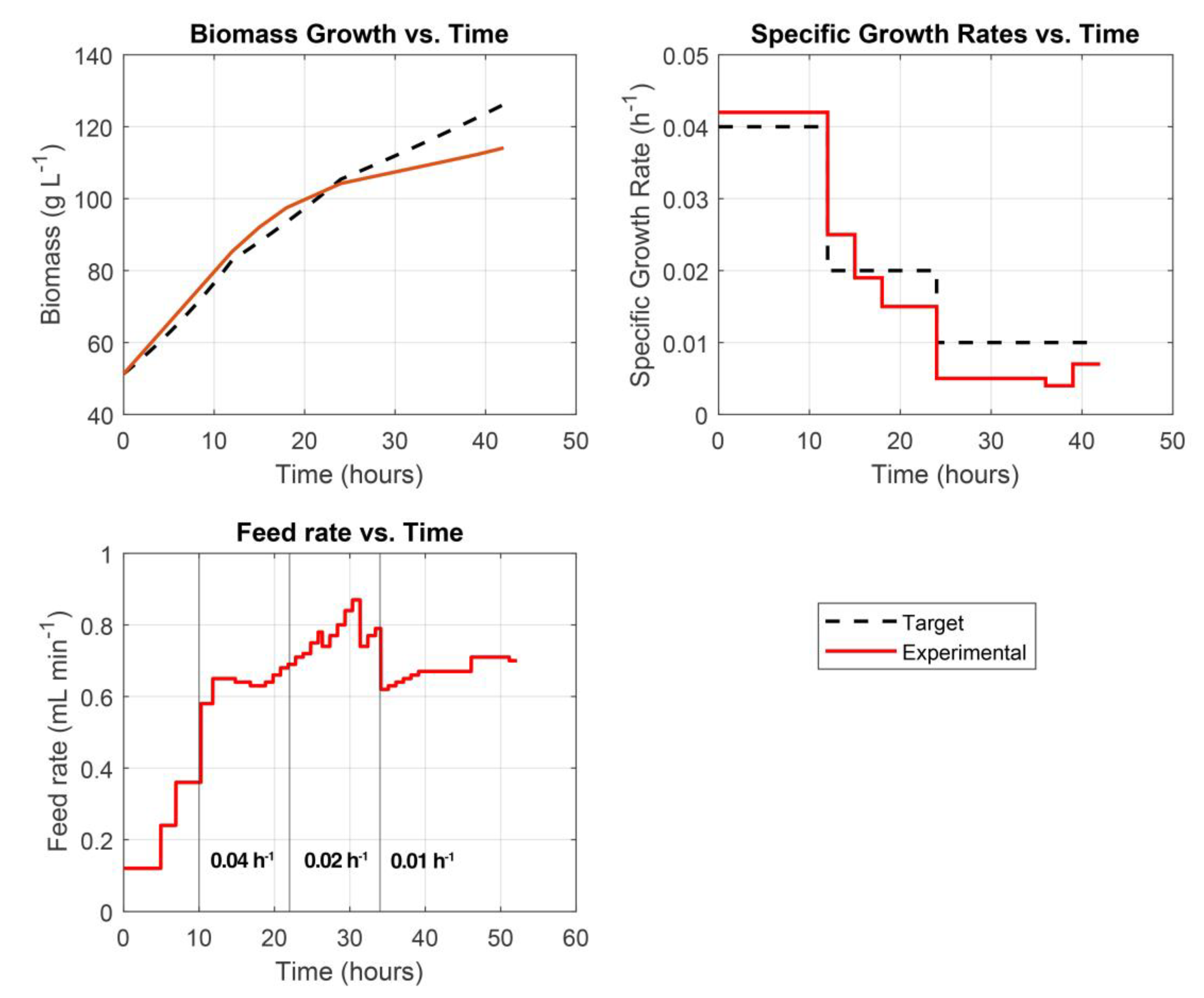

MPC was initiated after methanol adaptation, typically 8–10 hours after inoculation. The growth rate setpoint μₛₑₜ(t) was scheduled in a step-wise fashion to reflect the physiological limits of the cells: an initial value of 0.04 h⁻¹ was maintained for the first 12 hours, followed by reductions to 0.02 h⁻¹ and 0.01 h⁻¹ at 12-hour intervals. This trajectory was selected to optimize productivity while preventing metabolic overload during prolonged methanol feeding.

4. Discussion

This study highlights the efficiency of Bayesian optimization in identifying high-performing hybrid neural network architectures for dynamic bioprocess modeling. By concentrating on the most promising regions of the hyperparameter space, as demonstrated in neural architecture search literature [

53], Bayesian optimization substantially reduces the number of candidate configurations compared to exhaustive strategies like grid or random search. A consistent architectural pattern emerged among the top models: an LSTM layer followed by one or more fully connected (FC) layers. This aligns with findings that temporal feature extraction via LSTM is critical in sequence modeling, especially in bioprocess contexts [

54]. The FC layers then effectively map these temporal representations into nonlinear predictive outputs.

The grid search extended this exploration and employed AICc alongside validation loss to avoid overfitting. This Pareto front strategy is known to balance model complexity and accuracy [

31]. Selecting architectures from the mid-section of the Pareto front ensured efficient, generalizable models without unnecessary computational burden.

Robustness was confirmed through repeated training of the selected architectures, mitigating variability from random initialization. The best-performing model—a minimal architecture with 2 LSTM units and 8 FC nodes—achieved the lowest validation loss and AICc, illustrating that compact models can deliver strong performance. This has practical implications for real-time applications, where computational efficiency and stability are critical. Interestingly, dropout regularization consistently worsened performance, in contrast to its typical use in neural networks [

55]. This suggests that for relatively clean and small datasets, additional noise can lead to underfitting rather than preventing overfitting, corroborating findings in Bayesian LSTM studies [

56].

In summary, the structured workflow—combining Bayesian optimization, exhaustive grid search, and performance validation—successfully identified robust and efficient hybrid models. These findings offer valuable guidance for developing data-driven models in bioprocessing, particularly where data is limited and interpretability and computational efficiency are priorities.

The application of transfer learning significantly enhanced predictive modeling in Qβ fermentation. By freezing the pretrained LSTM layer, the model effectively retained temporal feature representations learned from the original fermentation dataset—an approach aligned with known benefits of sequential inductive transfer learning, where pretrained layers serve as robust feature extractors.

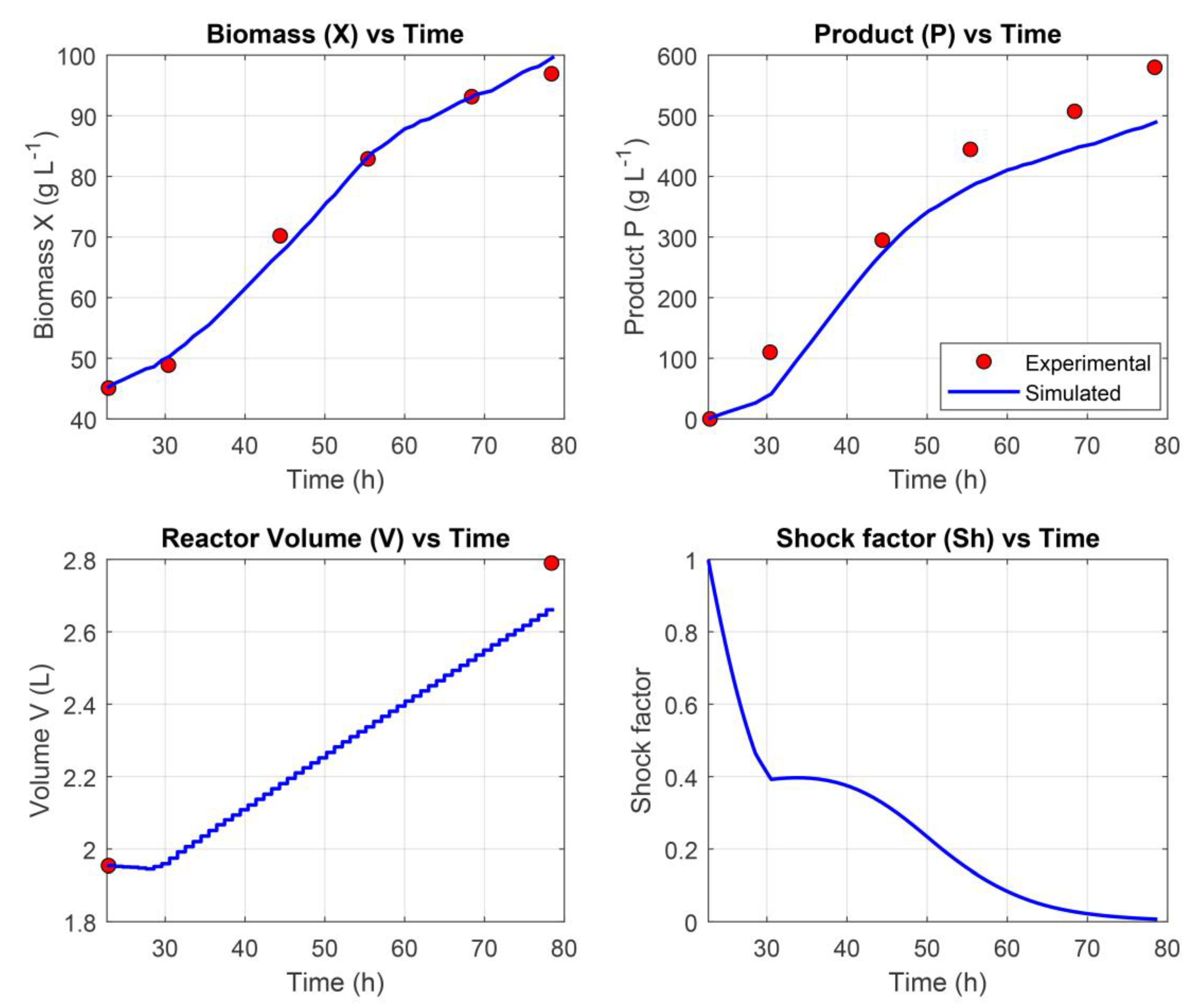

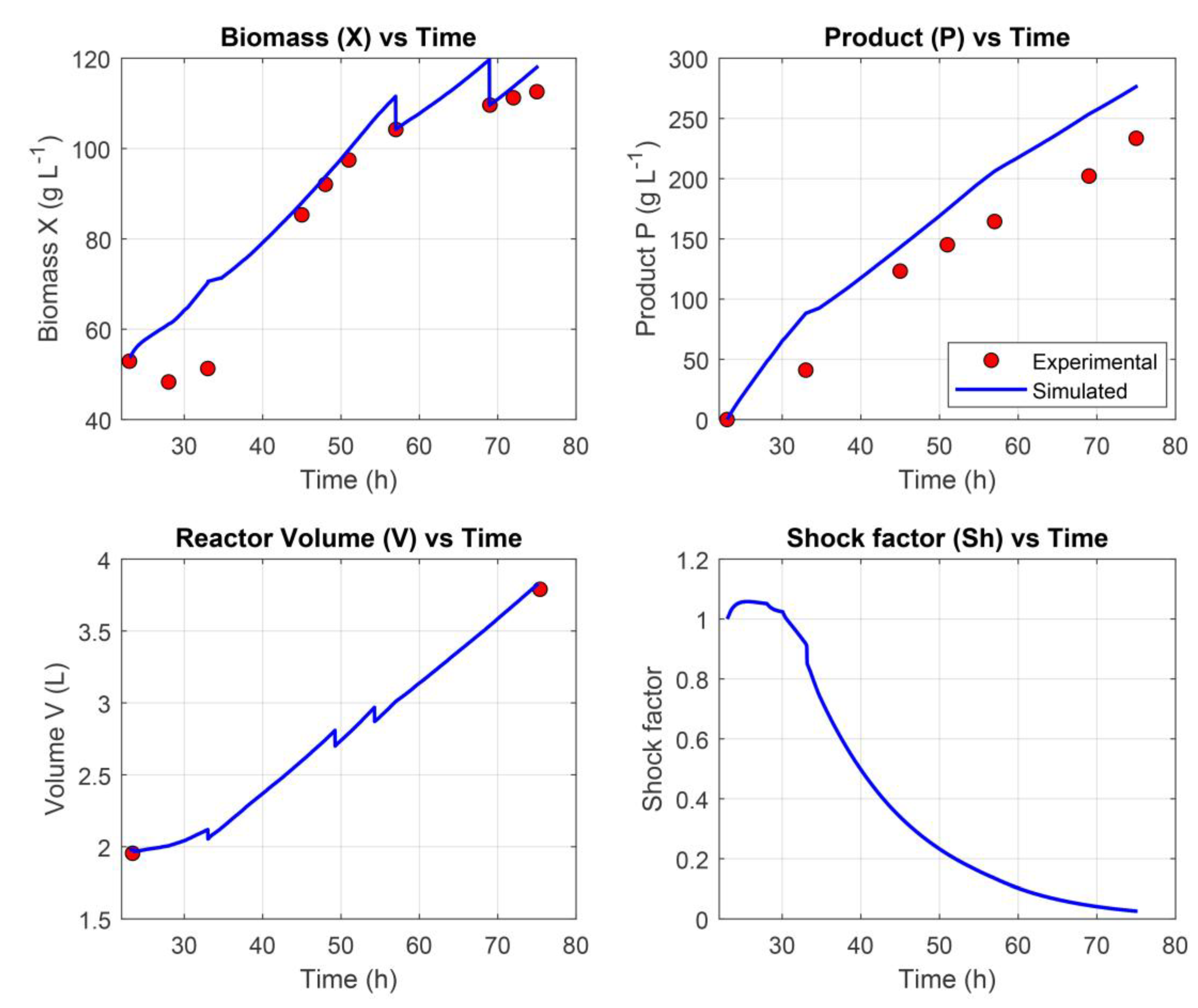

Performance metrics indicate robust predictive capability: training loss of 3.18%, validation loss of 3.53%, and testing loss of 5.61%, alongside an AICc value of 856. These figures suggest the model strikes a favorable balance between complexity and fit, as AICc penalizes excessive parameters. Figure 3 illustrates that the hybrid model accurately tracks the dynamic behavior of key process variables throughout the fermentation. Notably, the NRMSE of 1.68% for biomass (X) reflects excellent predictive accuracy, while a 9.54% NRMSE for product concentration (P) indicates reliable estimation of recombinant protein output—performance consistent with successful domain adaptation observed in bioprocess transfer learning studies.

Overall, these results highlight that freezing the LSTM backbone preserves essential time-series features, enabling efficient adaptation to new but related bioprocesses. This echoes broader evidence that transfer learning, particularly with LSTM architectures, reliably enhances performance in data-constrained scenarios [

27]. The Qβ model's strong performance, with an experimental dataset of only 3 fermentation runs, underscores the hybrid model's generalizability, positioning this approach as a promising strategy for rapid deployment in diverse fermentation contexts.

To assess the practical utility of the hybrid MPC framework, a real-time control experiment was conducted involving feed rate adjustment in an actual P. pastoris fermentation (Figure 4). This exercise evaluated the framework’s ability to predict and regulate critical bioprocess variables during active operation. The hybrid model achieved a biomass NRMSE of 6.51%, indicative of moderate accuracy. However, the model struggled during the 8–12 hour adaptation phase following methanol induction, consistently overestimating X—likely due to the challenge of capturing initial physiological delays. During later stages, persistent biomass overestimation required offline-informed manual corrections, a common issue in MPC applications where adaptation lags affect real-time feedback control. Again, the model tended to overpredict P, with an average NRMSE of 14.65%, revealing moderate accuracy in tracking recombinant protein dynamics.

Despite prediction inaccuracies, the hybrid MPC effectively maintained the target specific growth rate (µ) via robust feed profiles (Figure 5). This demonstrates the framework’s resilience and ability to meet control objectives even under prediction uncertainty. However, in the final 12 hours—particularly after µ dropped to 0.001 h⁻¹—deviations emerged. These were likely driven by methanol-induced cytotoxicity, which reduced cellular metabolism and hindered biomass formation.

The hybrid MPC system showed strong real-time control capabilities, effectively regulating substrate feed to meet specific growth objectives throughout most of the fermentation. Prediction errors were manageable and did not significantly impair overall control performance. The observed late-stage deviations underscore the importance of incorporating biological stress factors—such as methanol toxicity—into model formulations.

This validation confirms that hybrid MPC, built on data-driven hybrid models, is a viable strategy for real-world bioprocess control. Future work should focus on refining model representations—possibly by including toxicity effects—and improving early-stage adaptation dynamics. Doing so would further enhance both predictive fidelity and control reliability, supporting broader application in fermentation-based production workflows. Also, a reliable estimator for recombinant protein concentration should be included in the MPC framework to provide accurate and reliable estimations to use for hybrid model re-training during operation.

5. Conclusions

This study presents a comprehensive framework for hybrid modeling and control of P. pastoris fed-batch fermentations, integrating deep learning with model predictive control (MPC). The use of Bayesian optimization proved effective in identifying efficient and accurate hybrid neural network architectures, with consistent structural trends—namely, the inclusion of an LSTM layer followed by fully connected layers—emerging among top-performing models. A complementary grid search, guided by AICc and validation loss, enabled the selection of models that balance accuracy with computational simplicity.

Transfer learning was successfully employed to adapt the optimal hybrid model to Qβ fermentation data, achieving strong predictive performance while preserving generalizable temporal features. This highlights the model's flexibility and potential for rapid adaptation to new, yet related, bioprocesses—an important capability in multiproduct biomanufacturing environments.

Experimental validation of the hybrid MPC framework demonstrated reliable real-time control of the fermentation process, despite moderate prediction errors in biomass and product concentration. Notably, the system maintained accurate regulation of the specific growth rate throughout most of the process, underscoring its practical robustness.

In summary, this work establishes a robust, adaptable, and computationally efficient hybrid modeling approach for model predictive bioprocess control. The combination of automated architecture search, transfer learning, and MPC provides a scalable methodology for accelerating digital twin deployment in industrial biotechnology. Future work should aim to enhance biological realism and expand generalizability across strains and production conditions.