Submitted:

07 July 2025

Posted:

11 July 2025

Read the latest preprint version here

Abstract

Keywords:

2. Results and Discussion

2.1. Oil Yield and Quality Parameters of Croatian Virgin Olive Oils

2.2. Lipoxygenase Activity and Composition of Volatile Compounds in Croatian Virgin Olive Oils

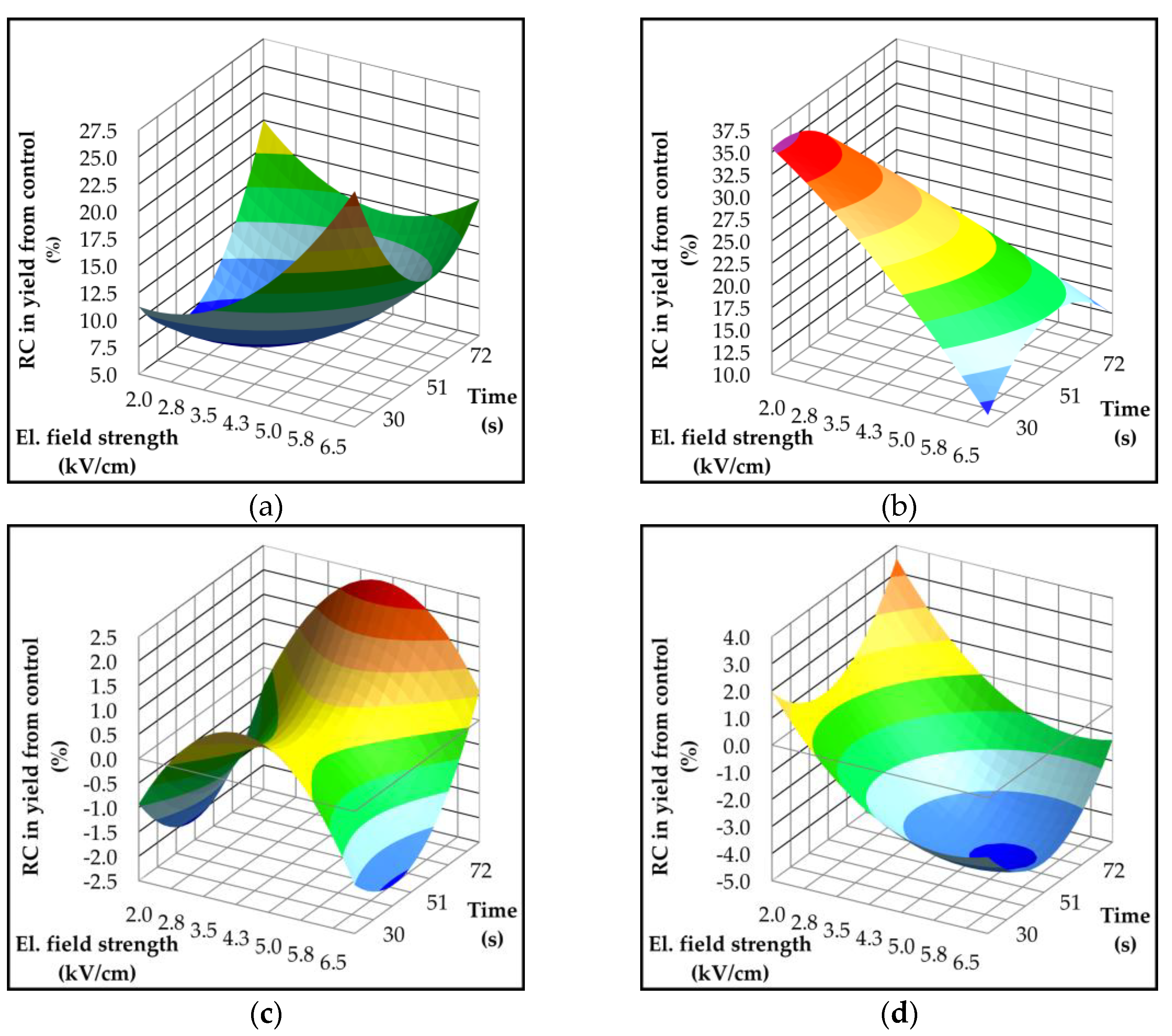

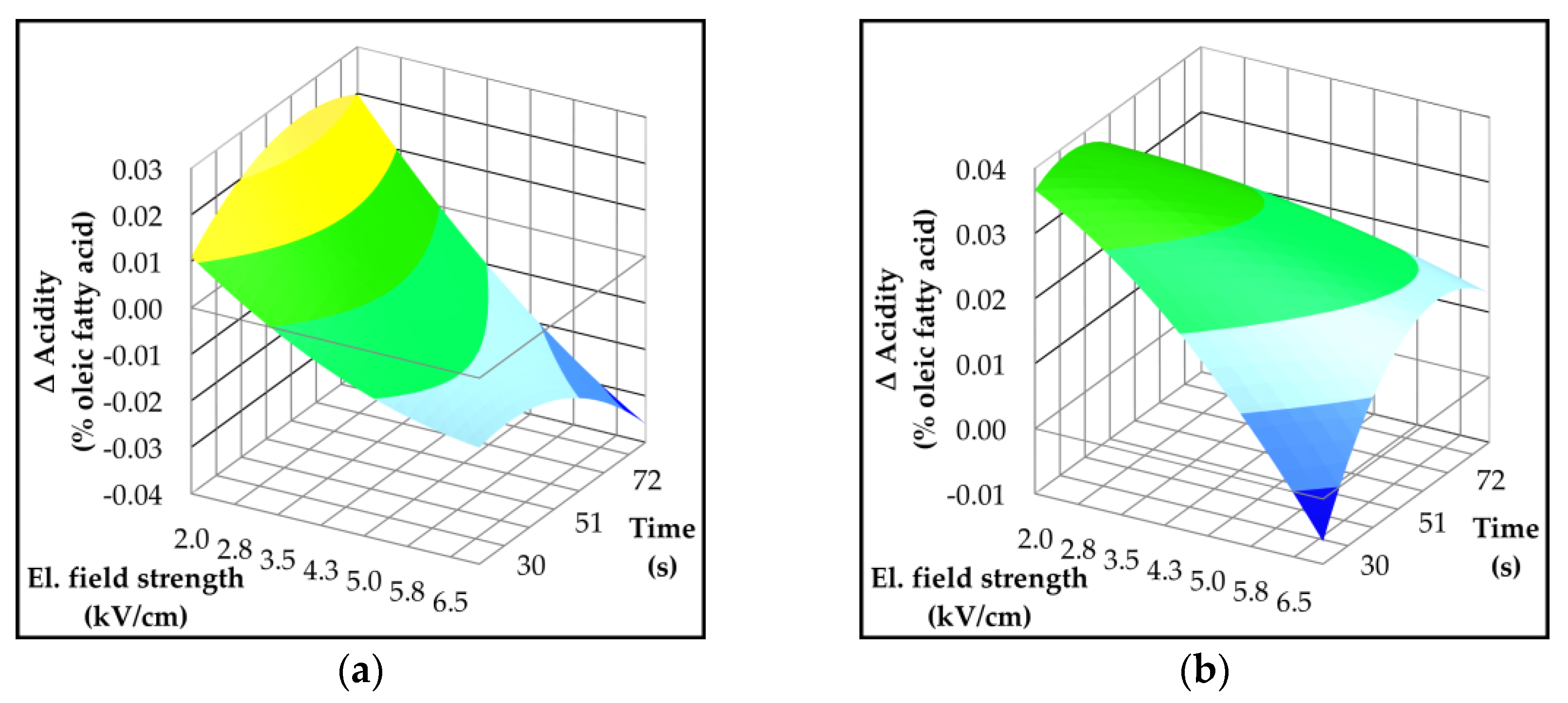

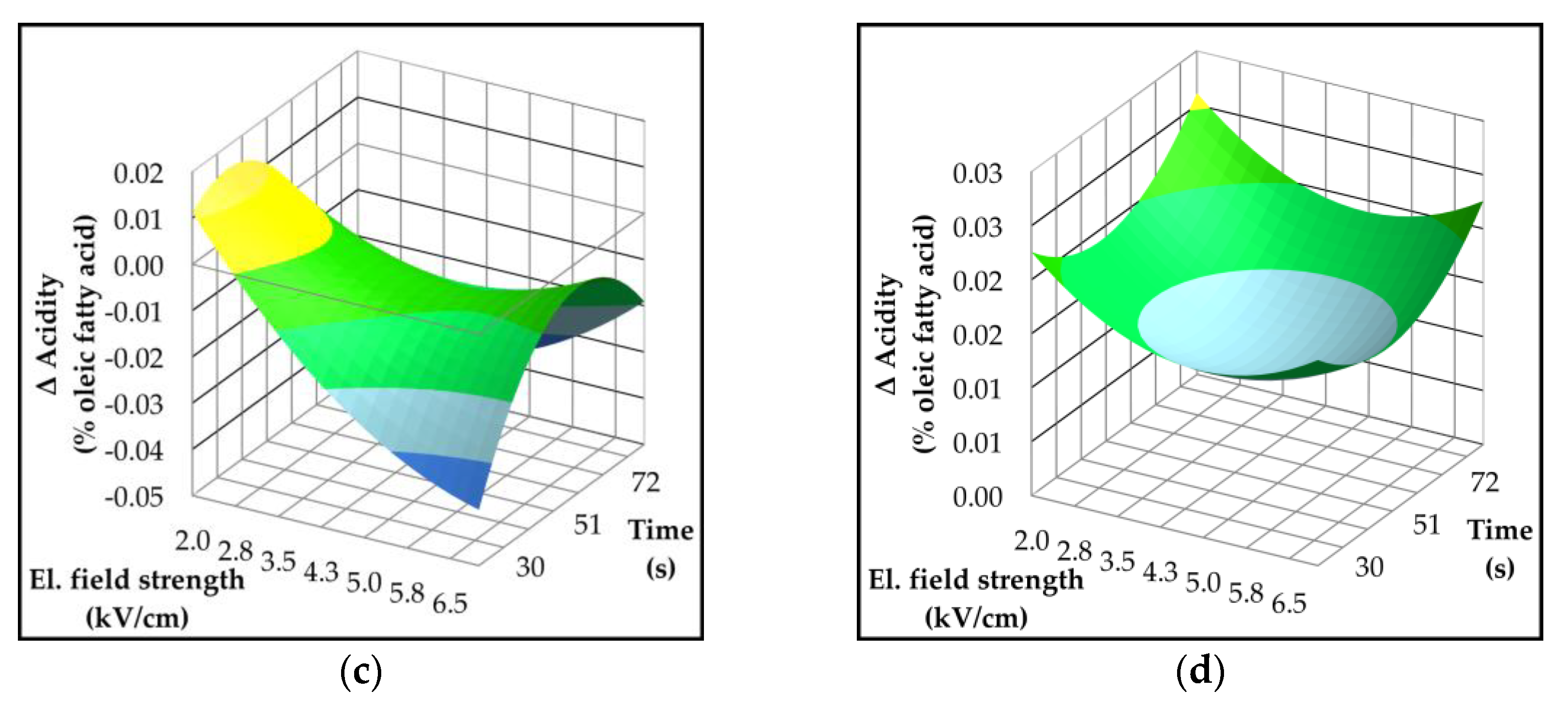

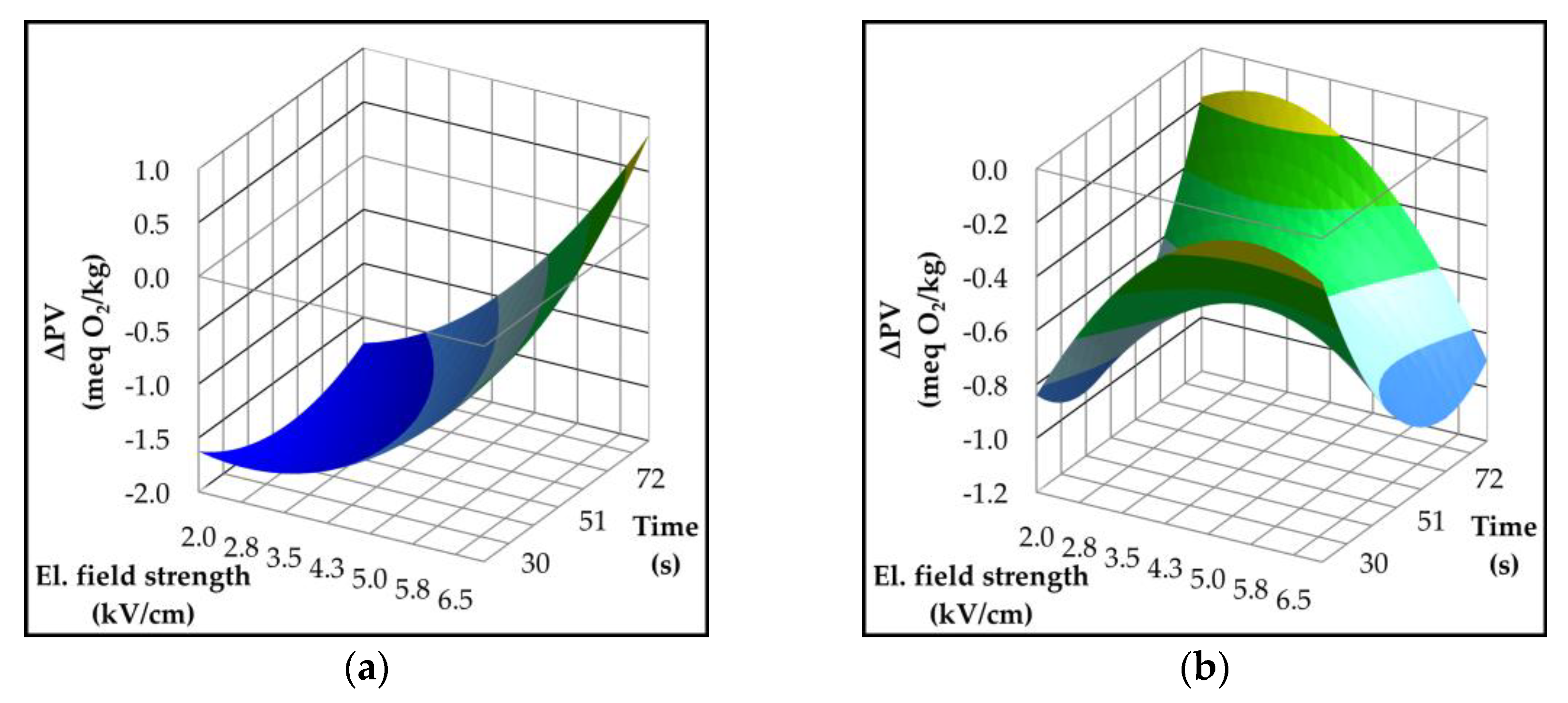

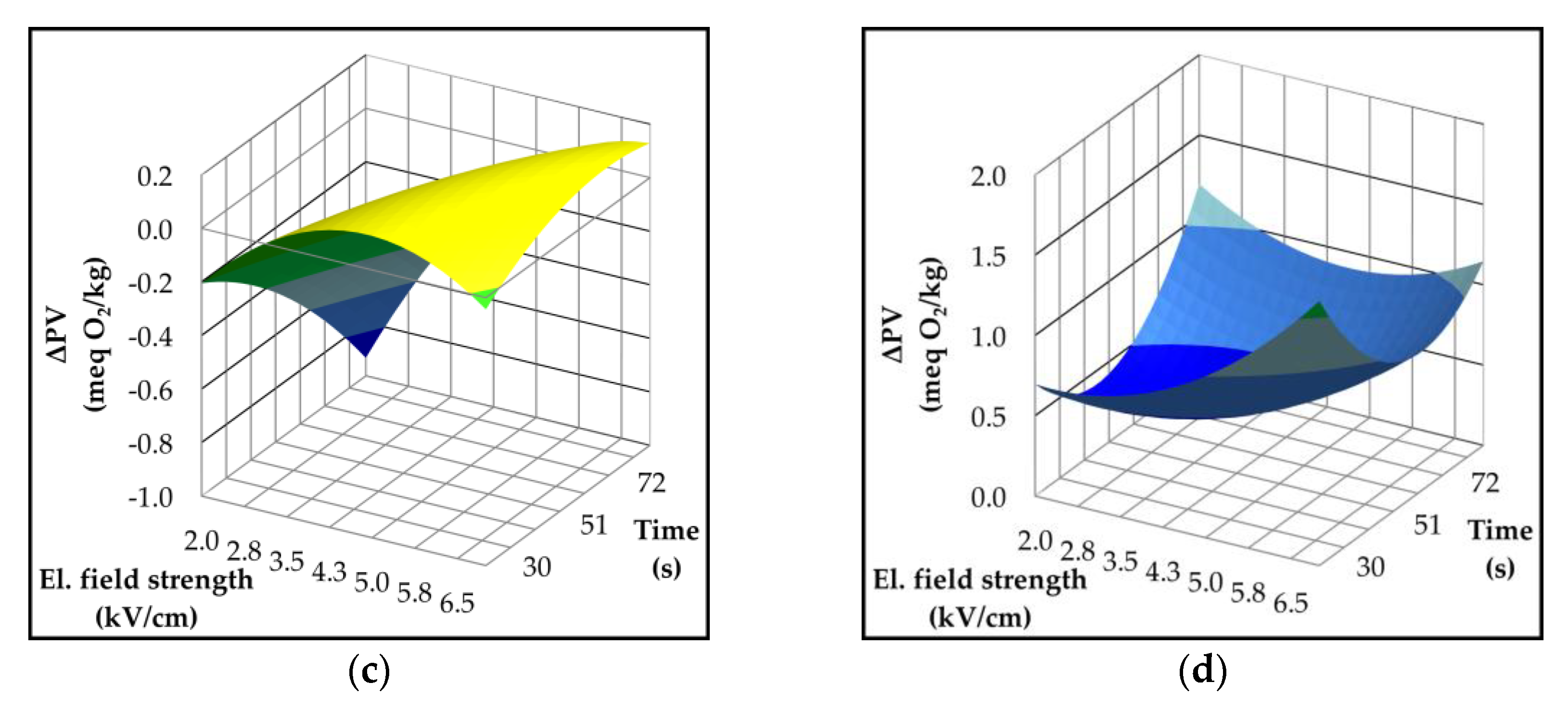

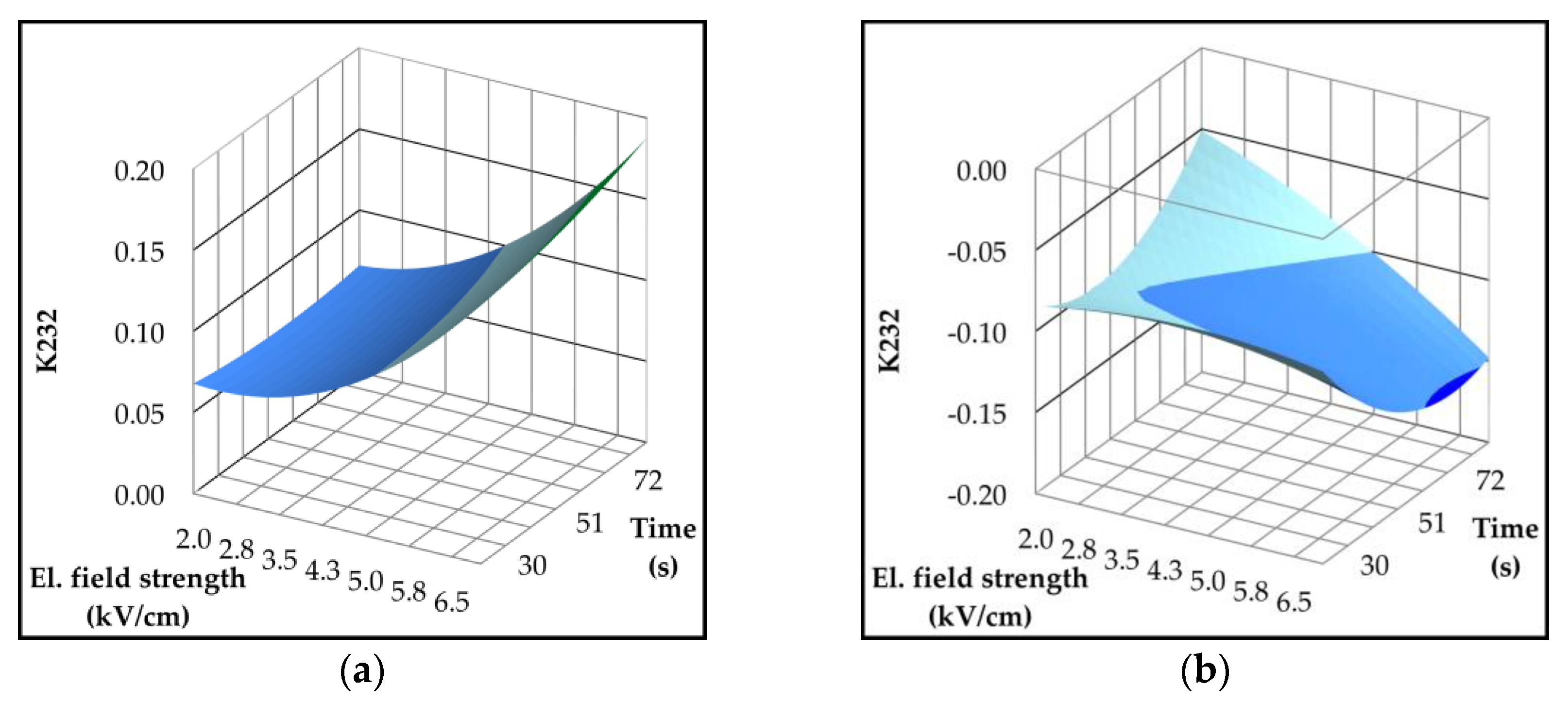

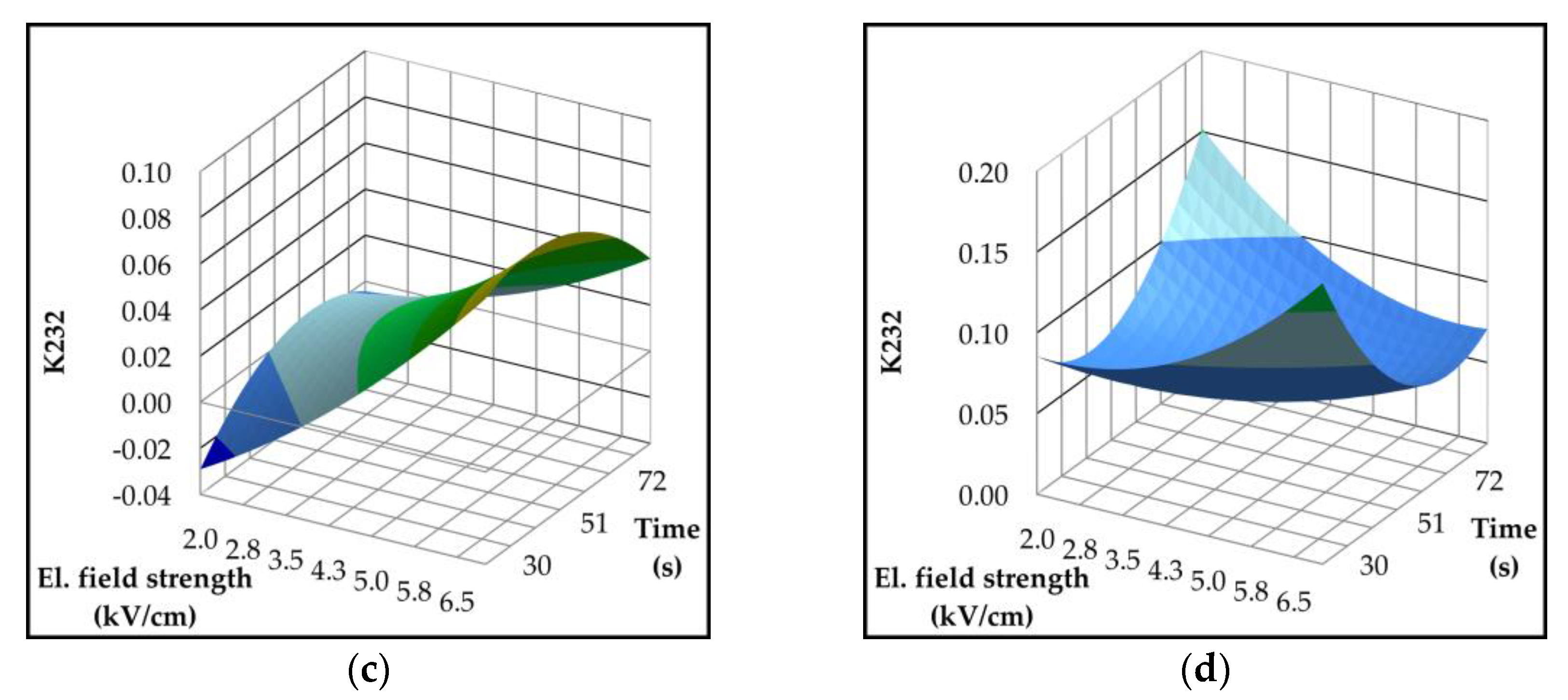

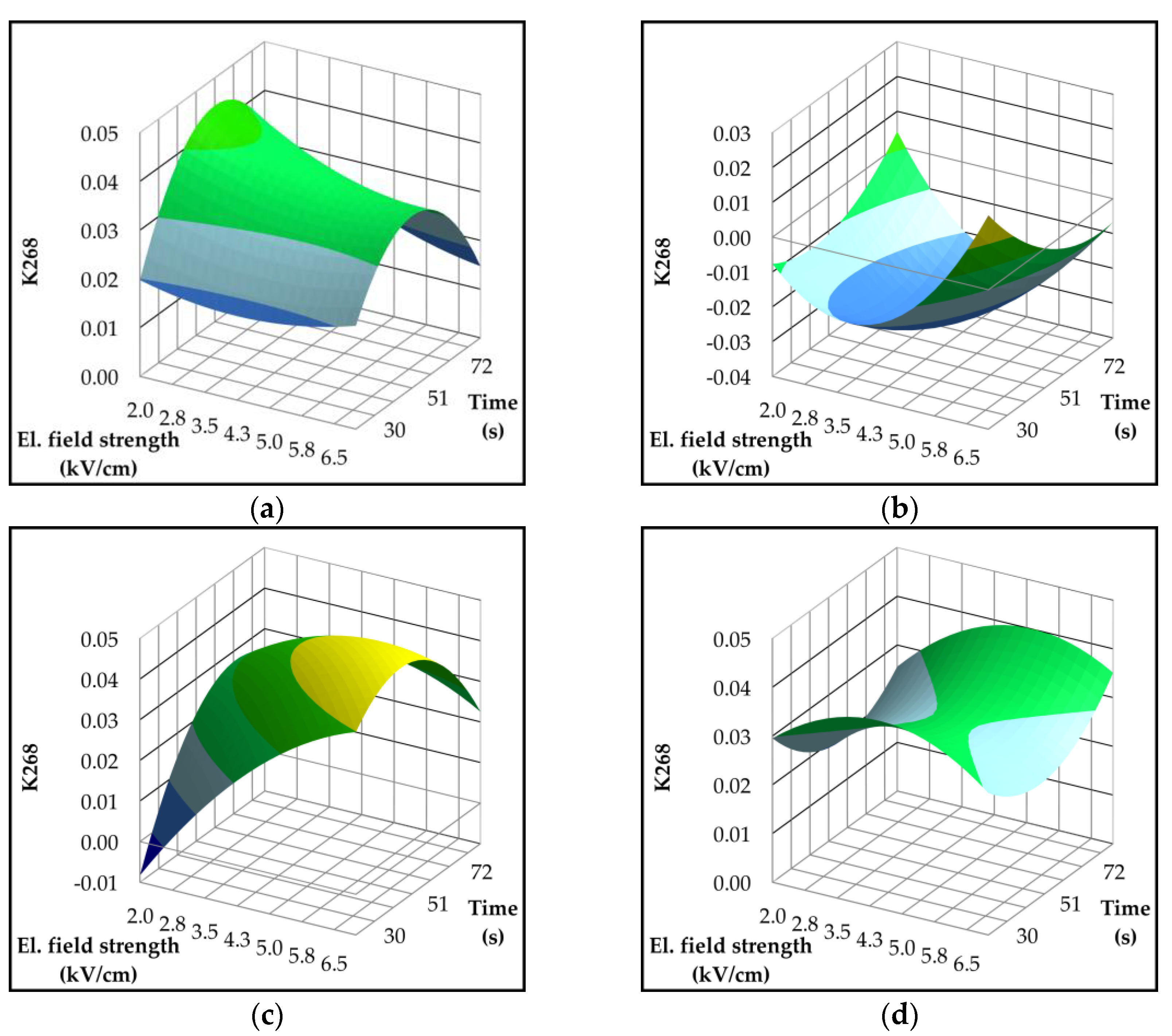

2.3. Effect of Pulsed Electric Field on Oil Yield and Quality Parameters

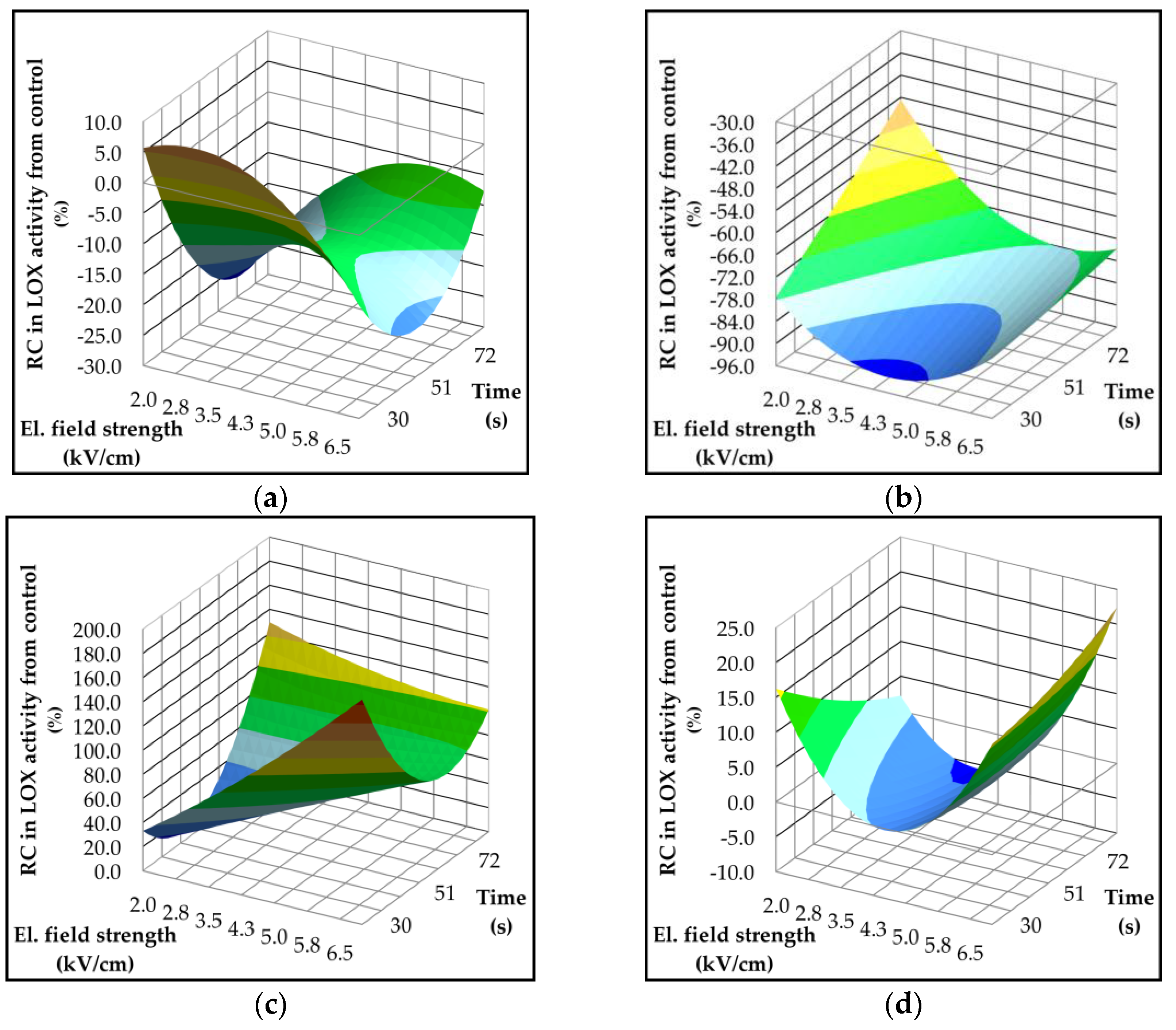

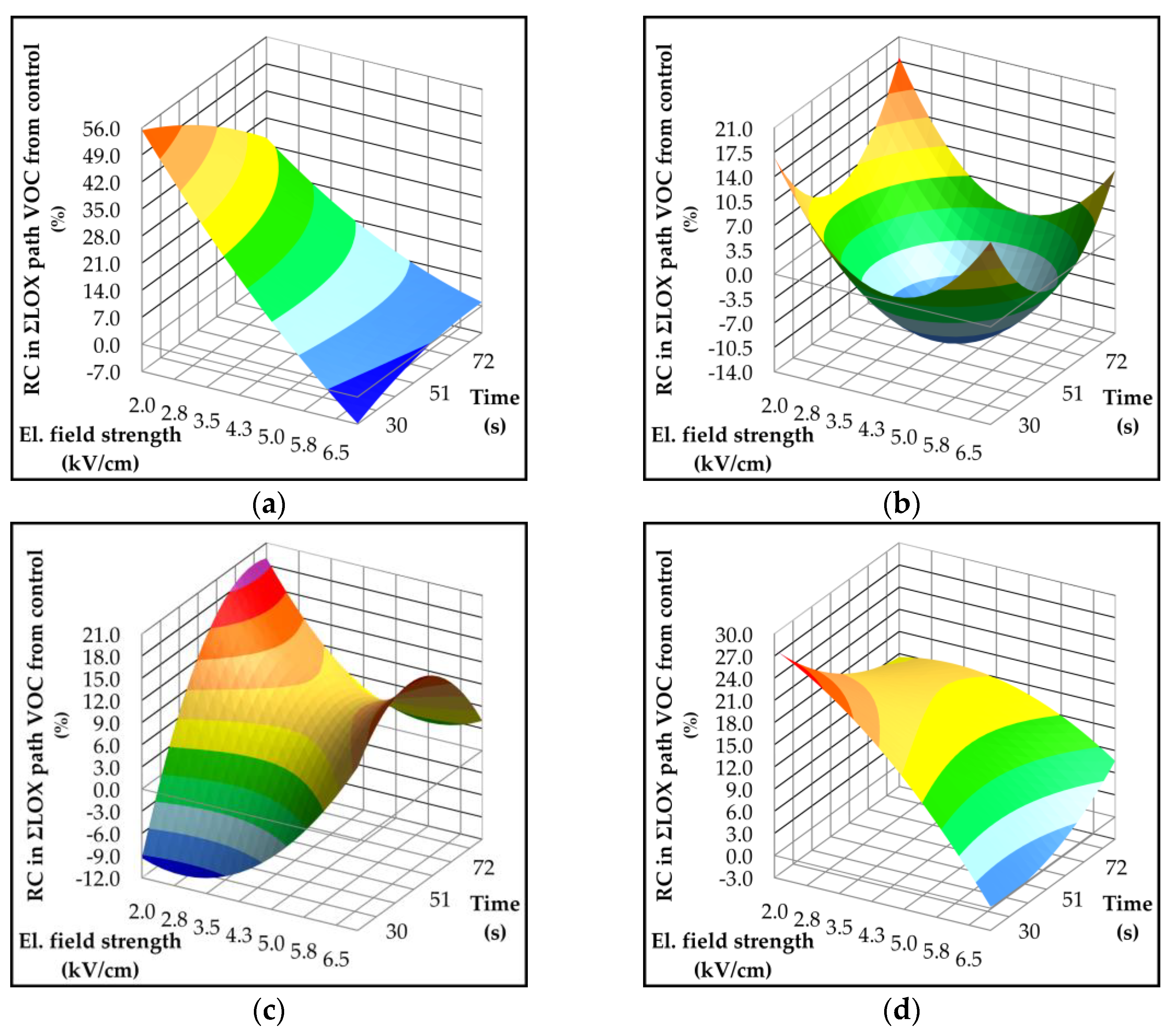

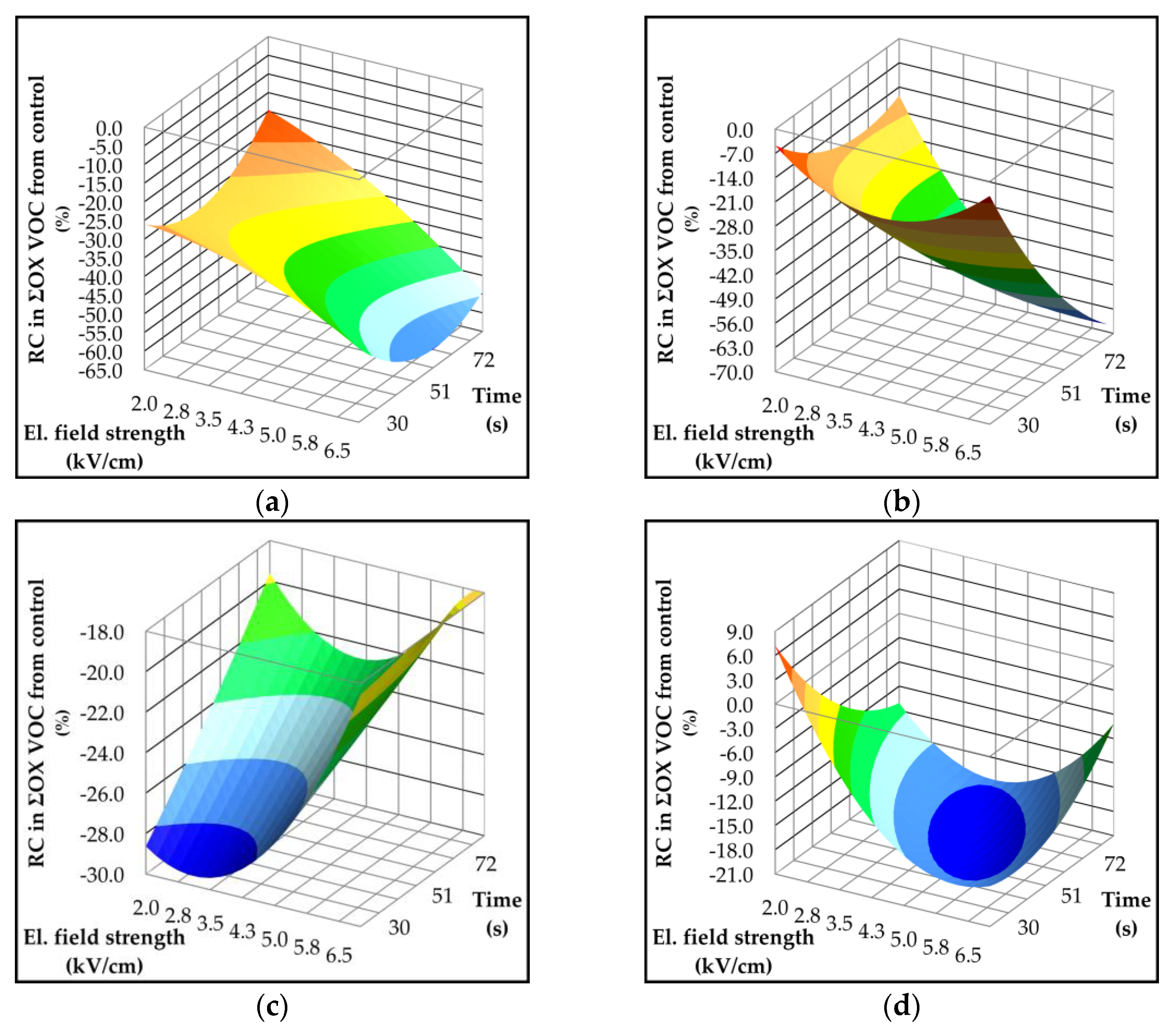

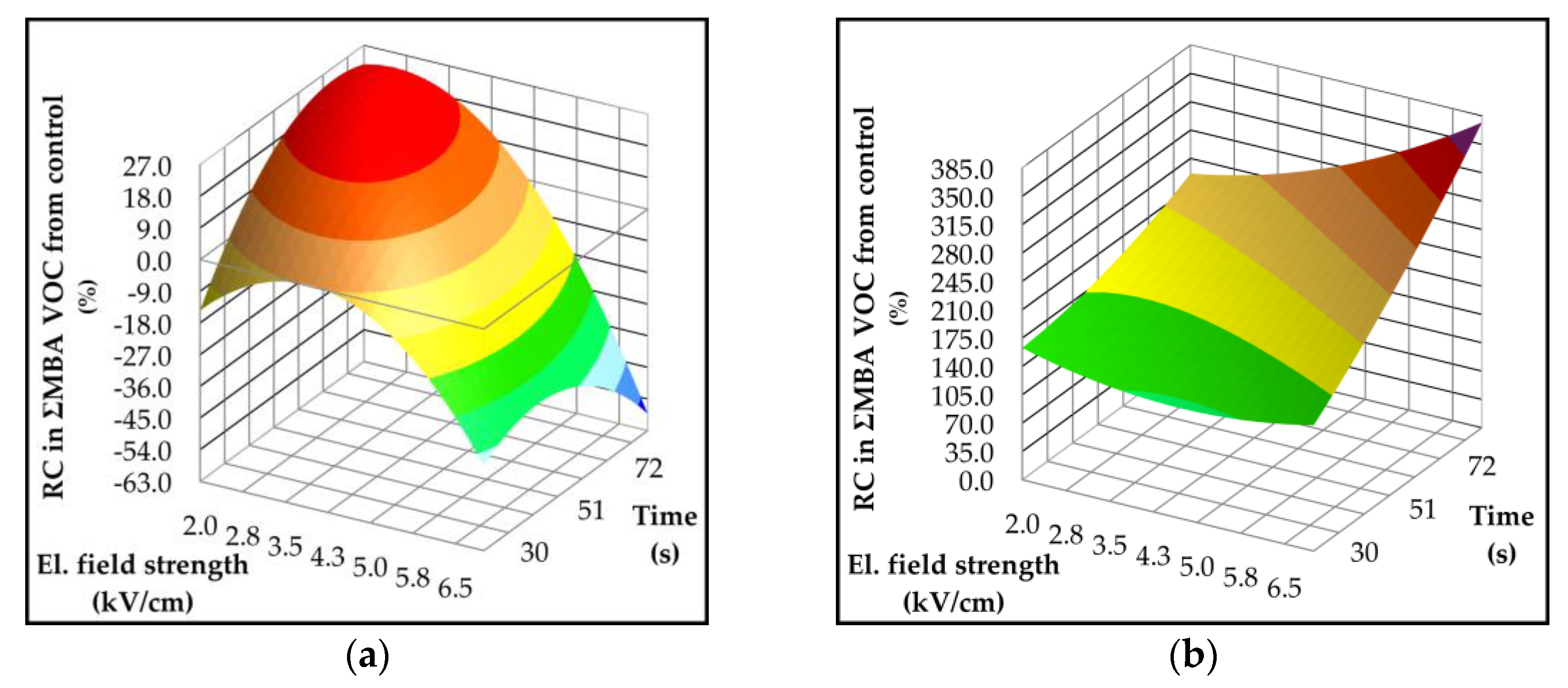

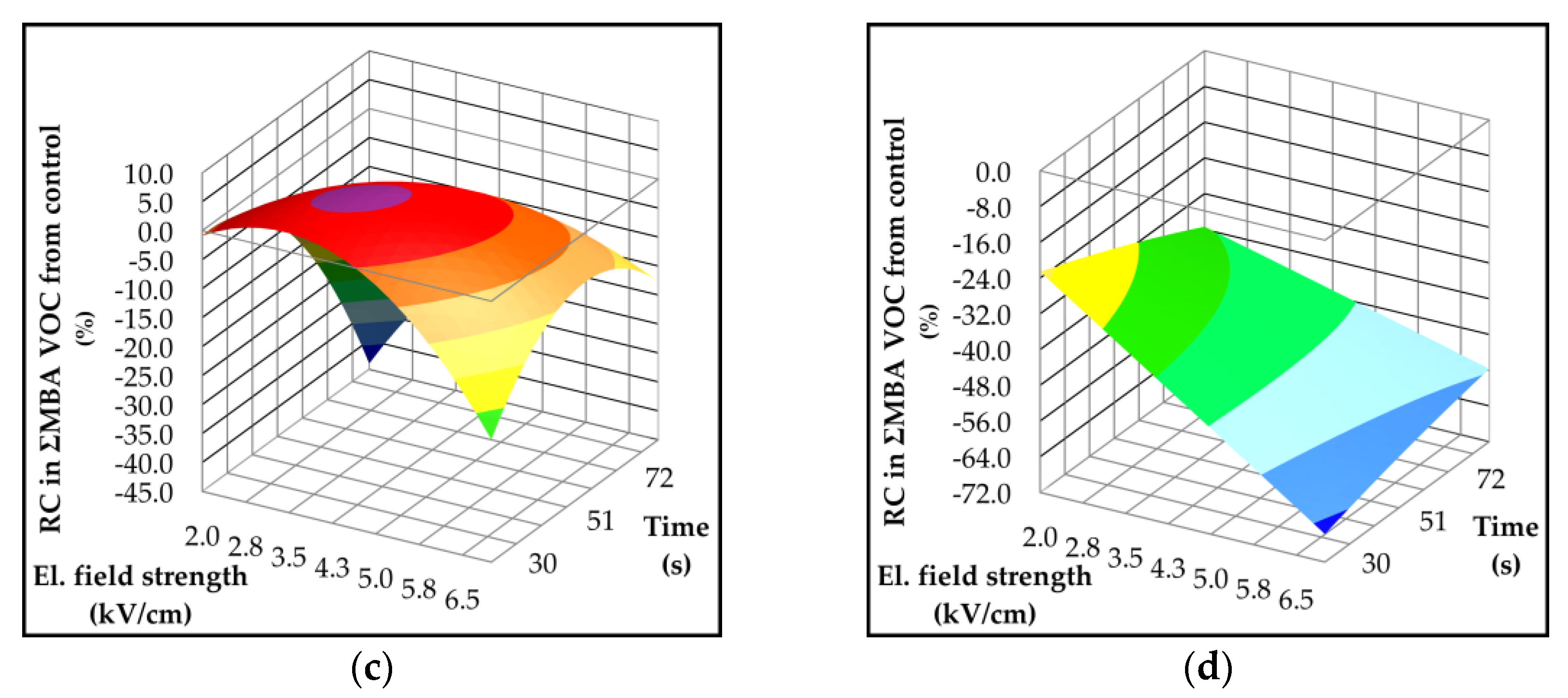

2.4. Effect of Pulsed Electric Field on Lipoxygenase Activity and Volatile Compounds

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Plant Material

3.2. Olive Oil Production

3.3. Oil Yield

3.4. Basic Quality Parameters

3.5. Lipoxygenase (LOX) Activity

3.6. Volatile Components

3.7. Statistical Analysis

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Abbreviations

| VOO | Virgin olive oil |

| PEF | Pulsed electric field |

| PV | Peroxide value |

| VOC | Volatile organic compounds |

| LOX | Lipoxygenase |

| HPOT | Hydroperoxy-octadecatrienoic acid |

| ADH | Alcohol dehydrogenase |

| AAT | Alcohol acetyl transferase (AAT) |

| OX | Oxidation |

| MBA | Microbiological activity |

| DAD | Diode array detector |

| ALA | α-linolenic acid |

References

- Yan, B.; Li, J.; Liang, Q.C.; Huang, Y.; Cao, S.L.; Wang, L.H.; Zeng, X.A. From Laboratory to Industry: The Evolution and Impact of Pulsed Electric Field Technology in Food Processing. Food Rev Int 2025, 41, 373–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nowosad, K.; Sujka, M.; Pankiewicz, U.; Kowalski, R. The Application of PEF Technology in Food Processing and Human Nutrition. J Food Sci Technol 2021, 58, 397–411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ohshima, T.; Tanino, T.; Guionet, A.; Takahashi, K.; Takaki, K. Mechanism of Pulsed Electric Field Enzyme Activity Change and Pulsed Discharge Permeabilization of Agricultural Products. Jpn J Appl Phys 2021, 60, 060501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, W.; Zhang, R.B.; Wang, L.M.; Chen, J.; Guan, Z.C. Conformation Changes of Polyphenol Oxidase and Lipoxygenase Induced by PEF Treatment. J Appl Electrochem 2010, 40, 295–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aguiló-Aguayo, I.; Sobrino-López, Á.; Soliva-Fortuny, R.; Martín-Belloso, O. Influence of High-Intensity Pulsed Electric Field Processing on Lipoxygenase and β-Glucosidase Activities in Strawberry Juice. Innov Food Sci Emerg Technol 2008, 9, 455–462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kraljić, K.; Balbino, S.; Filipan, K.; Herceg, Z.; Stuparević, I.; Ivanov, M.; Vukušić Pavičić, T.; Jakoliš, N.; Škevin, D. Innovative Approaches to Enhance Activity of Endogenous Olive Enzymes—A Model System Experiment: Part II—Non-Thermal Technique. Processes 2023, 11, 3283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cecchi, L.; Migliorini, M.; Mulinacci, N. Virgin Olive Oil Volatile Compounds: Composition, Sensory Characteristics, Analytical Approaches, Quality Control, and Authentication. J Agric Food Chem 2021, 69, 2013–2040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clodoveo, M.L.; Hachicha Hbaieb, R. Beyond the Traditional Virgin Olive Oil Extraction Systems: Searching Innovative and Sustainable Plant Engineering Solutions. Food Res Int 2013, 54, 1926–1933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aguilera, M.P.; Beltran, G.; Sanchez-Villasclaras, S.; Uceda, M.; Jimenez, A. Kneading Olive Paste from Unripe ‘Picual’ Fruits: I. Effect on Oil Process Yield. J Food Eng 2010, 97, 533–538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leone, A.; Tamborrino, A.; Esposto, S.; Berardi, A.; Servili, M. Investigation on the Effects of a Pulsed Electric Field (PEF) Continuous System Implemented in an Industrial Olive Oil Plant. Foods 2022, Vol. 11, Page 2758 2022, 11, 2758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Navarro, A.; Ruiz-Méndez, M.V.; Sanz, C.; Martínez, M.; Rego, D.; Pérez, A.G. Application of Pulsed Electric Fields to Pilot and Industrial Scale Virgin Olive Oil Extraction: Impact on Organoleptic and Functional Quality. Foods 2022, 11, 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tamborrino, A.; Urbani, S.; Servili, M.; Romaniello, R.; Perone, C.; Leone, A. Pulsed Electric Fields for the Treatment of Olive Pastes in the Oil Extraction Process. Appl Sci 2019, 10, 114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Puértolas, E.; Martínez de Marañón, I. Olive Oil Pilot-Production Assisted by Pulsed Electric Field: Impact on Extraction Yield, Chemical Parameters and Sensory Properties. Food Chem 2015, 167, 497–502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Veneziani, G.; Esposto, S.; Taticchi, A.; Selvaggini, R.; Sordini, B.; Lorefice, A.; Daidone, L.; Pagano, M.; Tomasone, R.; Servili, M. Extra-Virgin Olive Oil Extracted Using Pulsed Electric Field Technology: Cultivar Impact on Oil Yield and Quality. Front Nutr 2019, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brkić Bubola, K.; Lukić, M.; Novoselić, A.; Krapac, M.; Lukić, I. Olive Fruit Refrigeration during Prolonged Storage Preserves the Quality of Virgin Olive Oil Extracted Therefrom. Foods 2020, 9, 1445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marcelić, Š.; Vidović, N.; Pasković, I.; Lukić, M.; Špika, M.J.; Palčić, I.; Lukić, I.; Petek, M.; Pecina, M.; Herak Ćustić, M.; et al. Combined Sulfur and Nitrogen Foliar Application Increases Extra Virgin Olive Oil Quantity without Affecting Its Nutritional Quality. Horticulturae 2022, 8, 203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Majetić Germek, V.; Butinar, B.; Pizzale, L.; Bučar-Miklavčič, M.; Conte, L.S.; Koprivnjak, O. Phenols and Volatiles of Istarska Bjelica and Leccino Virgin Olive Oils Produced with Talc, NaCl and KCl as Processing Aids. J Am Oil Chem Soc 2016, 93, 1365–1372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Škevin, D.; Balbino, S.; Žanetić, M.; Jukić Špika, M.; Koprivnjak, O.; Filipan, K.; Obranović, M.; Žanetić, K.; Smajić, E.; Radić, M.; et al. Improvement of Oxidative Stability and Antioxidative Capacity of Virgin Olive Oil by Flash Thermal Pretreatment – Optimization Process. Foods 2025, submited. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Product-Specification-EXTRA-VIRGIN-OLIVE-OIL-OF-HERZEGOVINA. Available online: https://fsa.gov.ba/wp-content/uploads/2025/06/product-specification-extra-virgin-olive-oil-of-herzegovina.pdf (accessed on 20 May 2025).

- Žanetić, M.; Jukić Špika, M.; Ožić, M.M.; Brkić Bubola, K. Comparative Study of Volatile Compounds and Sensory Characteristics of Dalmatian Monovarietal Virgin Olive Oils. Plants 2021, 10, 1995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jukić Špika, M.; Žanetić, M.; Kraljić, K.; Pasković, I.; Škevin, D. Changes in Olive Fruit Characteristics and Oil Accumulation in ‘Oblica’ and ‘Leccino’ during Ripening. Acta Hortic 2018, 543–548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nissim, Y.; Shloberg, M.; Biton, I.; Many, Y.; Doron-Faigenboim, A.; Zemach, H.; Hovav, R.; Kerem, Z.; Avidan, B.; Ben-Ari, G. High Temperature Environment Reduces Olive Oil Yield and Quality. PLoS One 2020, 15, e0231956. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strikic, F.; Bandelj Mavsar, D.; Perica, S.; Cmelik, Z.; Satovic, Z.; Javornik, B. The Main Croatian Olive Cultivar, ‘Oblica’, Shows High Morphological but Low Molecular Diversity. J Hortic Sci Biotechnol 2009, 84, 345–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Žanetić, M.; Cerretani, L.; Del Carlo, M. Preliminary Characterisation of Monovarietal Extra-Virgin Olive Oils Obtained from Dif-Ferent Cultivars in Croatia. J Commod Sci Technol Qual 2007, 46, 79–94. [Google Scholar]

- Commission Delegated Regulation Commission Delegated Regulation (EU) 2022/2104 of 29 July 2022 Supplementing Regulation (EU) No 1308/2013 of the European Parliament and of the Council as Regards Marketing Standards for Olive Oil, and Repealing Commission Regulation (EEC) No 2568/91 and Commission Implementing Regulation (EU) No 29/2012. 2022.

- Sánchez-Ortiz, A.; Romero-Segura, C.; Sanz, C.; Pérez, A.G. Synthesis of Volatile Compounds of Virgin Olive Oil Is Limited by the Lipoxygenase Activity Load during the Oil Extraction Process. J Agric Food Chem 2012, 60, 812–822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salas, J.J.; Williams, M.; Harwood, J.L.; Sánchez, J. Lipoxygenase Activity in Olive (Olea Europaea) Fruit. J Am Oil Chem Soc 1999, 76, 1163–1168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tomé-Rodríguez, S.; Ledesma-Escobar, C.A.; Penco-Valenzuela, J.M.; Priego-Capote, F. Cultivar Influence on the Volatile Components of Olive Oil Formed in the Lipoxygenase Pathway. LWT-Food Sci Technol 2021, 147, 111485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luna, G.; Morales, M.T.; Aparicio, R. Characterisation of 39 Varietal Virgin Olive Oils by Their Volatile Compositions. Food Chem 2006, 98, 243–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Vico, L.; Belaj, A.; Sánchez-Ortiz, A.; Martínez-Rivas, J.M.; Pérez, A.G.; Sanz, C. Volatile Compound Profiling by HS-SPME/GC-MS-FID of a Core Olive Cultivar Collection as a Tool for Aroma Improvement of Virgin Olive Oil. Molecules 2017, 22, 141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kesen, S.; Kelebek, H.; Selli, S. Characterization of the Key Aroma Compounds in Turkish Olive Oils from Different Geographic Origins by Application of Aroma Extract Dilution Analysis (AEDA). J Agric Food Chem 2014, 62, 391–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lukić, I.; Lukić, M.; Žanetić, M.; Krapac, M.; Godena, S.; Bubola, K.B. Inter-Varietal Diversity of Typical Volatile and Phenolic Profiles of Croatian Extra Virgin Olive Oils as Revealed by GC-IT-MS and UPLC-DAD Analysis. Foods 2019, Vol. 8, Page 565 2019, 8, 565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soldo, B.; Jukić Špika, M.; Pasković, I.; Vuko, E.; Polić Pasković, M.; Ljubenkov, I. The Composition of Volatiles and the Role of Non-Traditional LOX on Target Metabolites in Virgin Olive Oil from Autochthonous Dalmatian Cultivars. Molecules 2024, 29, 1696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tura, D.; Failla, O.; Bassi, D.; Attilio, C.; Serraiocco, A. Regional and Cultivar Comparison of Italian Single Cultivar Olive Oils According to Flavor Profiling. Eur J Lipid Sci Technol 2013, 115, 196–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Padilla, M.N.; Hernández, M.L.; Sanz, C.; Martínez-Rivas, J.M. Stress-Dependent Regulation of 13-Lipoxygenases and 13-Hydroperoxide Lyase in Olive Fruit Mesocarp. Phytochem 2014, 102, 80–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Romero, N.; Saavedra, J.; Tapia, F.; Sepúlveda, B.; Aparicio, R. Influence of Agroclimatic Parameters on Phenolic and Volatile Compounds of Chilean Virgin Olive Oils and Characterization Based on Geographical Origin, Cultivar and Ripening Stage. J Sci Food Agric 2016, 96, 583–592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Inglese, P.; Famiani, F.; Galvano, F.; Servili, M.; Esposto, S.; Urbani, S. Factors Affecting Extra-Virgin Olive Oil Composition. In Horticultural Reviews, Editor Janick, J.; Publisher: John Wiley & Sons, Inc., Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2010; Volume 38, pp. 83–147. [Google Scholar]

- Brkić Bubola, K.; Koprivnjak, O.; Sladonja, B.; Lukić, I. Volatile Compounds and Sensory Profiles of Monovarietal Virgin Olive Oil from Buža, Črna and Rosinjola Cultivars in Istria (Croatia). Food Technol Biotechnol 2012, 50, 192–198. Available online: https://hrcak.srce.hr/83932 (accessed on 12 February 2025).

- Majetić Germek, V.; Butinar, B.; Pizzale, L.; Bučar-Miklavčič, M.; Conte, L.S.; Koprivnjak, O. Phenols and Volatiles of Istarska Bjelica and Leccino Virgin Olive Oils Produced with Talc, NaCl and KCl as Processing Aids. J Am Oil Chem Soc 2016, 93, 1365–1372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koprivnjak, O.; Majetić, V.; Brkić Bubola, K.; Kosić, U. Variability of Phenolic and Volatile Compounds in Virgin Olive Oil from Leccino and Istarska Bjelica Cultivars in Relation to Their Fruit Mixtures. Food Technol Biotechnol 2012, 50, 216–221. [Google Scholar]

- Šarolić, M.; Gugić, M.; Friganović, E.; Tuberoso, C.I.G.; Jerković, I. Phytochemicals and Other Characteristics of Croatian Monovarietal Extra Virgin Olive Oils from Oblica, Lastovka and Levantinka Varieties. Molecules 2015, Vol. 20, Pages 4395-4409 2015, 20, 4395–4409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahonen, E.; Damerau, A.; Suomela, J.P.; Kortesniemi, M.; Linderborg, K.M. Oxidative Stability, Oxidation Pattern and α-Tocopherol Response of Docosahexaenoic Acid (DHA, 22:6n–3)-Containing Triacylglycerols and Ethyl Esters. Food Chem 2022, 387, 132882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, S.; Li, S.; Li, G.; Li, C.; Li, W.; Bi, Y.; Wei, J. Pulsed Electric Field Treatment Improves the Oil Yield, Quality, and Antioxidant Activity of Virgin Olive Oil. Food Chem X 2024, 22, 101372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez-Beamonte, R.; Ripalda, M.; Herrero-Continente, T.; Barranquero, C.; Dávalos, A.; López de las Hazas, M.C.; Álvarez-Lanzarote, I.; Sánchez-Gimeno, A.C.; Raso, J.; Arnal, C.; et al. Pulsed Electric Field Increases the Extraction Yield of Extra Virgin Olive Oil without Loss of Its Biological Properties. Front Nutr 2022, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abenoza, M.; Benito, M.; Saldaña, G.; Álvarez, I.; Raso, J.; Sánchez-Gimeno, A.C. Effects of Pulsed Electric Field on Yield Extraction and Quality of Olive Oil. Food Bioproc Tech 2013, 6, 1367–1373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Töpfl, S. Pulsed Electric Fields (PEF) for Permeabilization of Cell Membranes in Food-and Bioprocessing: Applications, Process and Equipment Design and Cost Analysis. Doctoral thesis, Technical University of Berlin, Berlin, Germany, Date of Completion 22 September 2006.

- Taha, A.; Casanova, F.; Šimonis, P.; Stankevič, V.; Gomaa, M.A.E.; Stirkė, A. Pulsed Electric Field: Fundamentals and Effects on the Structural and Techno-Functional Properties of Dairy and Plant Proteins. Foods 2022, 11, 1556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ho, S.Y.; Mittal, G.S.; Cross, J.D. Effects of High Field Electric Pulses on the Activity of Selected Enzymes. J Food Eng 1997, 31, 69–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fakas, S.; Kefalogianni, I.; Makri, A.; Tsoumpeli, G.; Rouni, G.; Gardeli, C.; Papanikolaou, S.; Aggelis, G. Characterization of Olive Fruit Microflora and Its Effect on Olive Oil Volatile Compounds Biogenesis. Eur J Lipid Sci Technol 2010, 112, 1024–1032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saldaña, G.; Álvarez, I.; Condón, S.; Raso, J. Microbiological Aspects Related to the Feasibility of PEF Technology for Food Pasteurization. Crit Rev Food Sci Nutr 2014, 54, 1415–1426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez, J.M.; Delso, C.; Álvarez, I.; Raso, J. Pulsed Electric Field-Assisted Extraction of Valuable Compounds from Microorganisms. Compr Rev Food Sci Food Saf 2020, 19, 530–552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- COI/OH/Doc. No 1 2011 Guide for the determination of the characteristics of oil-olives. Available online: https://www.internationaloliveoil.org/what-we-do/chemistry-standardisation-unit/standards-and-methods/ (accessed on 5 December 2023).

- Clodoveo, M.L. Malaxation: Influence on Virgin Olive Oil Quality. Past, Present and Future e An Overview. Trends Food Sci Technol 2012, 25, 13–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ISO 3960:2017 - Animal and Vegetable Fats and Oils — Determination of Peroxide Value — Iodometric (Visual) Endpoint Determination. Available online: https://www.iso.org/standard/71268.html (accessed on 4 December 2023).

- COI/T.20/Doc. No 34/Rev. 1 2017 Method determination of free fatty acids, cold method. Available online: https://www.internationaloliveoil.org/what-we-do/chemistry-standardisation-unit/standards-and-methods/ (accessed on 5 December 2023).

- COI/T.20/Doc. No 19/Rev. 5 2019 Method of analysis spectrophotometric investigation in the ultraviolet. Available online: https://www.internationaloliveoil.org/what-we-do/chemistry-standardisation-unit/standards-and-methods/ (accessed on 4 December 2023).

- Luaces, P.; Sanz, C.; Pérez, A.G. Thermal Stability of Lipoxygenase and Hydroperoxide Lyase from Olive Fruit and Repercussion on Olive Oil Aroma Biosynthesis. J Agric Food Chem 2007, 55, 6309–6313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barbara, S.; Matilda, Š.; Gloria, M.; Maja, P.V.; Ljubenkov, I. Evaluation of Olive Fruit Lipoxygenase Extraction Protocols on 9- and 13-Z,E-HPODE Formation. Molecules 2016, Vol. 21, Page 506 2016, 21, 506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bradford, M.M. A Rapid and Sensitive Method for the Quantitation of Microgram Quantities of Protein Utilizing the Principle of Protein-Dye Binding. Anal Biochem 1976, 72, 248–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kraljić, K.; Stjepanović, T.; Obranović, M.; Pospišil, M.; Balbino, S.; Škevin, D. Influence of Conditioning Temperature on the Quality, Nutritional Properties and Volatile Profile of Virgin Rapeseed Oil. Food Technol Biotechnol 2018, 56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Parameter | p-value | Variety | ||||

| Istarska bjelica | Rosulja | Levantinka | Oblica | |||

| Yield (%) | p ≤ 0.001 | 5.31 + 0.65 c | 5.74 + 0.56 c | 16.12 + 0.19 a | 11.19 + 0.79 b | |

| Acidity (% oleic fatty acid) | p ≤ 0.001 | 0.29 + 0.02 b | 0.37 + 0.01 a | 0.31 + 0.01 b | 0.20 + 0.01 c | |

| PV (meq O2/kg) | p ≤ 0.05 | 4.7 + 1.4 a | 4.3 + 0.2 ab | 2.7 + 0.2 b | 4.4 + 0.4 ab | |

| K-values | K232 | p ≤ 0.001 | 1.77 + 0.11 a | 1.93 + 0.03 a | 1.42 + 0.04 b | 1,49 + 0,04 b |

| K268 | p ≤ 0.001 | 0.13 + 0.02 ab | 0.17 + 0.01 a | 0.11 + 0.03 bc | 0,07 + 0,01 c | |

| ΔK | p = 0.119 | 0.00 + 0.00 | -0.01 + 0.01 | -0.01 + 0.01 | 0,00 + 0,00 | |

| Parameter | p-value | Variety | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Istarska bjelica | Rosulja | Levantinka | Oblica | ||||

| LOX Activity (µmol HPOT*/mg protein) |

p ≤ 0.001 | 15.48 + 0.61 b | 23.46 + 0.67 a | 2.42 + 0.36 d | 9.88 + 0.48 c | ||

| Volatile compound (mg/kg) |

RID** | ||||||

| from LOX path | |||||||

| 2-pentenal | A | p ≤ 0.001 | 0.68 ± 0.07 a | 0.10 ± 0.09 b | nd*** b | nd b | |

| 2-methyl-4-pentenal + 3-hexenal |

B B |

p ≤ 0.001 | 16.91 ± 1.01 a | 4.50 ± 0.88 b | 0.34 ± 0.18 c | 4.38 ± 0.68 b | |

| 2-hexenal | A | p ≤ 0.001 | 39.39 ± 6.56 a | 40.34 ± 2.79 a | 2.29 ± 2.53 b | 1.35 ± 0.49 b | |

| 1-penten-3-ol | A | p ≤ 0.01 | 0.87 ± 0.09 ab | 0.64 ± 0.15 b | 0.97 ± 0.10 a | 0.59 ± 0.09 b | |

| (E)-2-penten-1-ol | B | p = 0.441 | nd | nd | 0.07 ± 0.12 | nd | |

| (Z)-2-penten-1-ol | B | p ≤ 0.001 | 2.29 ± 0.32 a | 1.12 ± 0.17 b | 1.23 ± 0.10 b | 0.76 ± 0.09 b | |

| hexan-1-ol | B | p ≤ 0.001 | 0.33 ± 0.10 b | 0.99 ± 1.25 b | 3.42 ± 2.49 b | 9.94 ± 0.98 a | |

| 2-hexen-1-ol | A | p = 0.363 | 0.64 ± 0.32 | 10.25 ± 5.93 | 12.48 ± 1.56 | 8.50 ± 2.06 | |

| (E)-3-hexen-1-ol | A | p ≤ 0.001 | nd b | nd b | 0.50 ± 0.44 b | 1.29 ± 0.19 a | |

| (Z)-3-hexen-1-ol | A | p ≤ 0.001 | 9.78 ± 1.55 b | 6.83 ± 2.63 b | 7.59 ± 0.97 b | 19.48 ± 0.69 a | |

| 1-penten-3-one | A | p ≤ 0.001 | 4.48 ± 0.52 a | 1.08 ± 0.57 b | 1.07 ± 0.63 b | 0.51 ± 0.11 b | |

| pentan-3-one | B | p = 0.441 | nd | 0.25 ± 0.43 | nd | nd | |

| hexyl acetate | B | p ≤ 0.001 | nd b | nd b | 1.47 ± 0.20 a | nd b | |

| 3-hexenyl acetate | A | p ≤ 0.001 | nd b | 0.38 ± 0.12 b | 2.11 ± 0.38 a | nd b | |

| Total | p ≤ 0.01 | 75.37 ± 7.84 a | 66.48 ± 16.76 ab | 33.54 ± 5.08 c | 46.8 ± 3.61 bc | ||

| from OX | |||||||

| pentanal | A | p ≤ 0.001 | 0.43 ± 0.09 b | 0.21 ± 0.2 b | 1.32 ± 0.06 a | 1.06 ± 0.15 a | |

| 2,4-hexadienal | A | p ≤ 0.001 | 2.99 ± 0.92 a | 0.77 ± 0.2 b | 0.11 ± 0.04 b | 0.10 ± 0.05 b | |

| 4-oxohex-2-enal | B | p ≤ 0.001 | 4.94 ± 0.38 a | 0.91 ± 0.26 b | 0.19 ± 0.19 c | 0.03 ± 0.05 c | |

| nonanal | B | p = 0.07 | 0.18 ± 0.08 | 0.27 ± 0.07 | 0.14 ± 0.03 | 0.15 ± 0.02 | |

| Total | p ≤ 0.001 | 8.53 ± 1.16 a | 2.16 ± 0.56 b | 1.77 ± 0.25 b | 1.33 ± 0.1 b | ||

| from MBA | |||||||

| 2-methylbutanal | C | p ≤ 0.001 | 0.53 ± 0.21 a | 0.06 ± 0.05 b | nd b | 0.01 ± 0.02 b | |

| 3-methylbutanal | B | p ≤ 0.001 | 0.35 ± 0.10 a | nd b | nd b | nd b | |

| pentan-1-ol | B | p ≤ 0.05 | nd b | 0.06 ± 0.10 b | 0.24 ± 0.07 ab | 0.43 ± 0.23 a | |

| Total | p ≤ 0.05 | 0.89 ± 0.32 a | 0.12 ± 0.14 b | 0.24 ± 0.07 b | 0.45 ± 0.26 ab | ||

| Volatile compound | RID* | p-value | Field strength (kV/cm) / Time (s) | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 / 60 | 2 / 30 | 2 / 90 | 4.5 / 18 | 4.5 / 60 | 4.5 / 102 | 7 / 30 | 7 / 90 | 8 / 60 | |||

| from LOX path | |||||||||||

| 2-pentenal | A | p ≤ 0.001 | -0.23 ± 0.10 a | -0.23 ± 0.07 a | -0.26 ± 0.04 a | -0.27 ± 0.07 a | -0.19 ± 0.08 a | -0.19 ± 0.12 a | -0.26 ± 0.14 a | -0.68 ± 0.00 b | -0.68 ± 0.00 b |

|

2-methyl-4-pentenal + 3-hexenal |

B B |

p = 0.129 | -7.54 ± 0.85 | -6.24 ± 0.71 | -6.17 ± 0.78 | -9.16 ± 1.17 | -9.64 ± 5.05 | -2.12 ± 4.08 | -4.88 ± 3.94 | -8.33 ± 0.23 | -14.51 ± 0.09 |

| 2-hexenal | A | p ≤ 0.001 | 45.82 ± 5.33 a | 47.44 ± 7.31 a | 45.22 ± 6.2 a | 39.08 ± 11.11 a | 24.77 ± 12.32 ab | -2.63 ± 9.54 bc | -5.58 ± 11.11 c | -25.91 ± 0.31 c | -37.61 ± 0.41 c |

| 1-penten-3-ol | A | p ≤ 0.01 | -0.07 ± 0.04 b | -0.07 ± 0.07 b | -0.02 ± 0.08 ab | -0.18 ± 0.07 b | -0.02 ± 0.15 ab | -0.04 ± 0.23 ab | -0.11 ± 0.24 b | 0.26 ± 0.05 ab | 0.40 ± 0.02 a |

| (E) -2-penten-1-ol | B | ** | 0.00 ± 0.00 | 0.00 ± 0.00 | 0.00 ± 0.00 | 0.00 ± 0.00 | 0.00 ± 0.00 | 0.00 ± 0.00 | 0.00 ± 0.00 | 0.32 ± 0.01 | 0.00 ± 0.00 |

| (Z) -2-penten-1-ol | B | p = 0.473 | -0.20 ± 0.09 | -0.22 ± 0.23 | -0.17 ± 0.17 | -0.57 ± 0.30 | -0.18 ± 0.35 | -0.27 ± 0.57 | -0.49 ± 0.56 | -0.06 ± 0.05 | 0.23 ± 0.12 |

| hexan-1-ol | B | p ≤ 0.001 | 0.18 ± 0.13 c | 0.06 ± 0.02 c | 0.03 ± 0.01 c | -0.04 ± 0.05 c | 0.04 ± 0.12 c | -0.17 ± 0.03 c | -0.16 ± 0.05 c | 2.91 ± 0.39 b | 5.56 ± 0.09 a |

| 2-hexen-1-ol | A | p ≤ 0.001 | 0.73 ± 0.12 c | 0.62 ± 0.11 cd | 0.52 ± 0.11 cd | 0.34 ± 0.14 cd | 0.36 ± 0.28 cd | -0.33 ± 0.08 d | -0.27 ± 0.12 cd | 21.18 ± 0.92 a | 18.97 ± 0.23 b |

| (Z) -3-hexen-1-ol | A | p ≤ 0.001 | -1.47 ± 0.75 b | -1.06 ± 0.72 b | -1.02 ± 0.49 b | -2.33 ± 1.18 b | -1.32 ± 1.36 b | -1.96 ± 1.96 b | -2.65 ± 2.36 b | 20.44 ± 0.94 a | 26.16 ± 4.21 a |

| 1-penten-3-one | A | p ≤ 0.001 | -1.38 ± 0.18 b | -1.14 ± 0.21 b | -1.14 ± 0.17 bc | -1.67 ± 0.30 b | -1.56 ± 0.46 b | -0.78 ± 0.86 b | -1.52 ± 1.05 b | -3.13 ± 0.09 c | 0.96 ± 0.03 a |

| from OX | |||||||||||

| pentanal | A | p ≤ 0.001 | -0.08 ± 0.13 b | -0.07 ± 0.02 b | -0.08 ± 0.01 b | -0.11 ± 0.04 b | -0.06 ± 0.13 b | -0.12 ± 0.01 b | -0.14 ± 0.14 b | 0.92 ± 0.05 a | 1.13 ± 0.05 a |

| 2,4-heksadienal | A | p ≤ 0.05 | -1.10 ± 0.96 ab | -0.12 ± 0.26 a | -0.09 ± 0.27 a | -1.59 ± 0.82 ab | -0.87 ± 0.81 ab | -0.94 ± 0.47 ab | -1.7 ± 0.27 ab | -1.84 ± 0.65 ab | -2.77 ± 0.03 b |

| 4-oxohex-2-enal | B | p ≤ 0.05 | -1.74 ± 0.85 a | -1.18 ± 0.07 a | -1.46 ± 0.38 a | -1.41 ± 0.72 a | -2.49 ± 1.48 a | -0.52 ± 1.43 a | -0.93 ± 1.34 a | -3.58 ± 0.18 a | -4.59 ± 0.05 a |

| nonanal | B | p = 0.109 | -0.05 ± 0.12 | 0.03 ± 0.01 | -0.18 ± 0.00 | 0.06 ± 0.03 | -0.07 ± 0.11 | -0.18 ± 0.00 | -0.13 ± 0.07 | -0.18 ± 0.00 | -0.09 ± 0.12 |

| from MBA | |||||||||||

| 2-methylbutanal | C | p ≤ 0.01 | 0.01 ± 0.07 abc | 0.07 ± 0.04 abc | 0.12 ± 0.07 ab | -0.23 ± 0.04 abc | 0.13 ± 0.19a | 0.02 ± 0.13 abc | -0.03 ± 0.19 abc | -0.28 ± 0.00 bc | -0.43 ± 0.01 c |

| 3-methylbutanal | B | p ≤ 0.01 | -0.02 ± 0.06 ab | -0.03 ± 0.01 ab | 0.02 ± 0.03 ab | -0.16 ± 0.03 abc | 0.04 ± 0.11 a | -0.02 ± 0.08 ab | -0.07 ± 0.10 abc | -0.19 ± 0.01 bc | -0.35 ± 0.00 c |

| Volatile compound | RID* | p-value | Field strength (kV/cm) / Time (s) | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 / 60 | 2 / 30 | 2 / 90 | 4.5 / 18 | 4.5 / 60 | 4.5 / 102 | 7 / 30 | 7 / 90 | 8 / 60 | |||

| from LOX path | |||||||||||

| 2-pentenal | A | p ≤ 0.01 | 0.07 ± 0.06 a | -0.10 ± 0.00 b | -0.01 ± 0.01 ab | 0.04 ± 0.02 ab | -0.02 ± 0.05 ab | 0.14 ± 0.01 a | 0.04 ± 0.01 ab | -0.04 ± 0.08 ab | 0.01 ± 0.00 ab |

|

2-methyl-4-pentenal + 3-hexenal |

B B |

p = 0.614 | 0.48 ± 0.25 | -1.25 ± 0.25 | -3.03 ± 0.18 | 0.46 ± 0.84 | -1.82 ± 2.46 | -2.40 ± 0.06 | 0.30 ± 0.86 | -3.20 ± 0.02 | -1.27 ± 0.15 |

| 2-hexenal | A | p = 0.096 | 20.09 ± 2.19 | -22.81 ± 2.18 | -29.38 ± 1.29 | 17.4 ± 6.26 | -14.85 ± 23.63 | 22.06 ± 1.40 | 18.36 ± 12.51 | -28.59 ± 0.10 | -18.71 ± 1.62 |

| 1-penten-3-ol | A | p = 0.554 | -0.04 ± 0.02 | 0.21 ± 0.03 | 0.29 ± 0.15 | 0.10 ± 0.05 | 0.20 ± 0.21 | 0.17 ± 0.03 | 0.02 ± 0.10 | 0.24 ± 0.00 | 0.23 ± 0.06 |

| (Z) -2-penten-1-ol | B | p = 0.101 | 0.10 ± 0.05 | 0.19 ± 0.12 | 0.32 ± 0.23 | 0.19 ± 0.16 | 0.11 ± 0.15 | 0.27 ± 0.04 | 0.19 ± 0.21 | 0.37 ± 0.02 | 0.37 ± 0.09 |

| hexan-1-ol | B | p ≤ 0.001 | -0.65 ± 0.01 b | 7.18 ± 0.67 a | 7.66 ± 1.13 a | -0.68 ± 0.00 b | 0.27 ± 1.34 b | -0.64 ± 0.07 b | -0.68 ± 0.06 b | 0.09 ± 1.37 b | 6.25 ± 0.36 a |

| 2-hexen-1-ol | A | p = 0.109 | -9.47 ± 0.03 | 19.95 ± 2.85 | 27.72 ± 4.97 | -9.16 ± 0.07 | 7.83 ± 16.68 | -8.95 ± 0.19 | -9.11 ± 0.24 | 31.14 ± 11.40 | 15.32 ± 1.72 |

| (Z) -3-hexen-1-ol | A | p ≤ 0.01 | -0.08 ± 0.74 abc | 8.80 ± 1.52 a | 7.76 ± 1.57 ab | -1.08 ± 0.45 bc | 1.39 ± 3.51 abc | -1.41 ± 0.14 bc | -1.17 ± 1.22 c | 3.73 ± 0.16 abc | 5.20 ± 0.75 abc |

| 1-penten-3-one | A | p = 0.153 | 0.43 ± 0.08 | -0.04 ± 0.17 | 0.11 ± 0.16 | 0.34 ± 0.06 | -0.52 ± 0.64 | 0.31 ± 0.08 | 0.17 ± 0.21 | -0.44 ± 0.00 | 0.24 ± 0.02 |

| pentan-3-on | B | p ≤ 0.01 | -0.08 ± 0.24 a | 0.67 ± 0.01 a | 0.93 ± 0.18 a | -0.25 ± 0.00 a | 0.28 ± 0.34 a | -0.25 ± 0.00 a | -0.25 ± 0.00 a | 0.92 ± 0.04 a | 0.95 ± 0.19 a |

| hexyl acetate | B | p ≤ 0.01 | 0.12 ± 0.01 a | 0.04 ± 0.06 ab | 0.00 ± 0.00 b | 0.00 ± 0.00 b | 0.01 ± 0.03 b | 0.00 ± 0.00 b | 0.00 ± 0.00 b | 0.00 ± 0.00 b | 0.00 ± 0.00 b |

| 3-hexenyl acetate | A | p ≤ 0.001 | 0.52 ± 0.15 a | 0.32 ± 0.14 a | -0.12 ± 0.06 bc | -0.26 ± 0.01 c | -0.26 ± 0.13 c | -0.26 ± 0.01 c | -0.13 ± 0.07 bc | -0.11 ± 0.02 bc | 0.19 ± 0.03 ab |

| from OX | |||||||||||

| pentanal | A | p = 0.149 | -0.03 ± 0.27 | -0.22 ± 0.00 | -0.22 ± 0.00 | 0.09 ± 0.31 | -0.16 ± 0.13 | 0.15 ± 0.01 | 0.16 ± 0.06 | -0.22 ± 0.00 | -0.22 ± 0.00 |

| 2,4-heksadienal | A | p = 0.778 | 0.46 ± 0.26 | -0.09 ± 0.27 | -0.36 ± 0.24 | 0.09 ± 0.22 | -0.21 ± 0.59 | 0.03 ± 0.08 | 0.19 ± 0.32 | -0.49 ± 0.01 | -0.29 ± 0.06 |

| 4-oxohex-2-enal | B | p = 0.077 | 0.52 ± 0.20 | -0.55 ± 0.17 | -0.79 ± 0.00 | -0.15 ± 0.14 | -0.51 ± 0.46 | -0.78 ± 0.00 | -0.08 ± 0.32 | -0.76 ± 0.06 | -0.68 ± 0.03 |

| nonanal | B | p ≤ 0.001 | 0.11 ± 0.01 a | 0.08 ± 0.05 ab | 0.01 ± 0.03 abc | 0.02 ± 0.02 abc | -0.11 ± 0.04 d | -0.02 ± 0.02 bcd | -0.04 ± 0.07 cd | -0.01 ± 0.02 abc | 0.04 ± 0.03 abc |

| from MBA | |||||||||||

| 2-methylbutanal | C | p ≤ 0.01 | 0.02 ± 0.00 ab | -0.06 ± 0.00 b | 0.00 ± 0.01 ab | 0.16 ± 0.03 a | 0.00 ± 0.00 b | 0.16 ± 0.00 a | 0.10 ± 0.03 ab | -0.03 ± 0.04 ab | 0.02 ± 0.00 ab |

| 3-methylbutanal | B | p ≤ 0.001 | 0.00 ± 0.00 b | 0.00 ± 0.00 b | 0.00 ± 0.00 b | 0.00 ± 0.00 b | 0.00 ± 0.00 b | 0.12 ± 0.00 a | 0.09 ± 0.02 ab | 0.00 ± 0.00 b | 0.00 ± 0.00 b |

| pentan-1-ol | B | p = 0.172 | -0.06 ± 0.00 | 0.43 ± 0.04 | 0.54 ± 0.08 | -0.06 ± 0.00 | 0.24 ± 0.32 | -0.06 ± 0.00 | -0.06 ± 0.00 | 0.51 ± 0.01 | 0.40 ± 0.04 |

| Volatile compound | RID* | p-value | Field strength (kV/cm) / Time (s) | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 / 60 | 2 / 30 | 2 / 90 | 4.5 / 18 | 4.5 / 60 | 4.5 / 102 | 7 / 30 | 7 / 90 | 8 / 60 | |||

| from LOX path | |||||||||||

| 2-pentenal | A | ** | 0.00 ± 0.00 | 0.00 ± 0.00 | 0.21 ± 0.02 | 0.00 ± 0.00 | 0.00 ± 0.00 | 0.00 ± 0.00 | 0.00 ± 0.00 | 0.00 ± 0.00 | 0.00 ± 0.00 |

|

2-methyl-4-pentenal + 3-hexenal |

B B |

p ≤ 0.001 | 0.07 ± 0.01 b | 0.23 ± 0.07 b | 2.14 ± 0.21 a | 0.05 ± 0.01 b | 0.20 ± 0.34 b | -0.14 ± 0.01 b | -0.22 ± 0.02 b | 0.08 ± 0.04 b | 1.49 ± 0.15 a |

| 2-hexenal | A | p ≤ 0.001 | -1.32 ± 0.19 c | -1.82 ± 0.07 c | 20.27 ± 2.10 a | -0.17 ± 0.45 c | 1.40 ± 2.64 c | -1.98 ± 0.02 c | -2.18 ± 0.01 c | 0.42 ± 0.29 c | 13.62 ± 0.95 b |

| 1-penten-3-ol | A | p = 0.079 | 0.04 ± 0.11 | 0.00 ± 0.12 | -0.09 ± 0.07 | -0.09 ± 0.01 | 0.10 ± 0.17 | 0.20 ± 0.06 | 0.24 ± 0.09 | 0.20 ± 0.13 | 0.00 ± 0.06 |

| (E) -2-penten-1-ol | B | p ≤ 0.01 | 0.19 ± 0.05 a | 0.10 ± 0.00 ab | -0.07 ± 0.00 b | 0.01 ± 0.11 ab | -0.03 ± 0.08 ab | 0.03 ± 0.09 ab | 0.16 ± 0.02 ab | 0.16 ± 0.03 ab | 0.00 ± 0.11 ab |

| (Z) -2-penten-1-ol | B | p = 0.079 | 0.20 ± 0.21 | 0.01 ± 0.07 | 0.17 ± 0.11 | -0.05 ± 0.03 | 0.01 ± 0.09 | -0.09 ± 0.05 | 0.03 ± 0.07 | 0.04 ± 0.16 | 0.11 ± 0.04 |

| hexan-1-ol | B | p ≤ 0.01 | -1.12 ± 0.61 ab | -0.16 ± 0.59 ab | -2.93 ± 0.04 b | -1.60 ± 0.00 ab | 1.88 ± 2.24 a | -1.21 ± 0.19 ab | -1.05 ± 0.10 ab | -1.89 ± 0.26 ab | 1.10 ± 0.33 ab |

| 2-hexen-1-ol | A | p ≤ 0.001 | 3.92 ± 2.80 a | -0.16 ± 1.47 a | -11.62 ± 0.01 b | -2.53 ± 0.02 a | -1.58 ± 2.80 a | 3.11 ± 1.29 a | 0.94 ± 0.76 a | -0.92 ± 1.31 a | -2.75 ± 0.67 a |

| (E) -3-hexen-1-ol | A | p ≤ 0.05 | 0.27 ± 0.08 a | 0.11 ± 0.09 a | -0.50 ± 0.00 a | -0.16 ± 0.49 a | -0.20 ± 0.34 a | 0.19 ± 0.07 a | 0.09 ± 0.04 a | -0.50 ± 0.00 a | -0.50 ± 0.00 a |

| (Z) -3-hexen-1-ol | A | p ≤ 0.001 | 1.37 ± 1.47 a | 0.16 ± 1.05 ab | -4.09 ± 0.28 d | -1.44 ± 0.05 bc | 0.78 ± 0.82 ab | 1.17 ± 0.65 a | 0.82 ± 0.41 ab | -2.5 ± 0.67 cd | 0.30 ± 0.44 ab |

| 1-penten-3-one | A | p ≤ 0.01 | -0.64 ± 0.01 a | 0.07 ± 0.11 a | 1.00 ± 0.14 a | 0.30 ± 0.05 a | 0.69 ± 0.88 a | -0.65 ± 0.01 a | -0.76 ± 0.04 a | -0.70 ± 0.07 a | 0.62 ± 0.07 a |

| hexyl acetate | B | p = 0.052 | 0.25 ± 0.37 | -0.02 ± 0.16 | 0.48 ± 0.18 | -0.13 ± 0.08 | 0.02 ± 0.24 | 0.44 ± 0.19 | 0.25 ± 0.16 | 0.15 ± 0.13 | 0.29 ± 0.15 |

| 3-hexenyl acetate | A | p ≤ 0.01 | 1.02 ± 0.58 abc | 0.52 ± 0.27 abc | 1.88 ± 0.44 a | 0.47 ± 0.04 abc | 0.08 ± 0.59 c | 1.19 ± 0.28 ab | 0.77 ± 0.13 abc | 0.84 ± 0.32 abc | 0.25 ± 0.16 bc |

| from OX | |||||||||||

| pentanal | A | p ≤ 0.001 | -0.1 ± 0.12 ab | -0.17 ± 0.13 ab | -0.91 ± 0.03 c | -0.29 ± 0.03 ab | -0.22 ± 0.09 ab | -0.03 ± 0.04 a | -0.02 ± 0.09 a | -0.08 ± 0.14 ab | -0.35 ± 0.13 b |

| 2,4-heksadienal | A | p ≤ 0.001 | -0.11 ± 0.00 c | -0.11 ± 0.00 c | 0.23 ± 0.11 a | -0.11 ± 0.00 c | -0.11 ± 0.00 c | -0.11 ± 0.00 c | -0.11 ± 0.00 c | -0.11 ± 0.00 c | 0.04 ± 0.00 b |

| 4-oxohex-2-enal | B | p ≤ 0.001 | -0.19 ± 0.00 c | -0.19 ± 0.00 c | 0.25 ± 0.14 a | -0.19 ± 0.00 c | -0.18 ± 0.03 c | -0.19 ± 0.00 c | -0.19 ± 0.00 c | -0.19 ± 0.00 c | 0.04 ± 0.01 b |

| nonanal | B | p = 757 | 0.02 ± 0.06 | 0.02 ± 0.02 | 0.04 ± 0.02 | 0.01 ± 0.01 | 0.04 ± 0.03 | 0.02 ± 0.02 | 0.04 ± 0.01 | 0.04 ± 0.02 | 0.05 ± 0.04 |

| from MBA | |||||||||||

| 2-methylbutanal | C | p ≤ 0.001 | 0.00 ± 0.00 c | 0.00 ± 0.00 c | 0.09 ± 0.00 a | 0.00 ± 0.00 c | 0.00 ± 0.00 c | 0.00 ± 0.00 c | 0.00 ± 0.00 c | 0.06 ± 0.00 b | 0.00 ± 0.00 c |

| pentan-1-ol | B | p ≤ 0.001 | -0.03 ± 0.03 a | 0.02 ± 0.04 a | -0.24 ± 0.00 b | -0.07 ± 0.00 ab | 0.03 ± 0.08 | -0.04 ± 0.01 a | 0.01 ± 0.02 a | -0.10 ± 0.02 ab | -0.09 ± 0.01 ab |

| Volatile compound | RID* | p-value | Field strength (kV/cm) / Time (s) | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 / 60 | 2 / 30 | 2 / 90 | 4.5 / 18 | 4.5 / 60 | 4.5 / 102 | 7 / 30 | 7 / 90 | 8 / 60 | |||

| from LOX path | |||||||||||

|

2-methyl-4-pentenal + 3-hexenal |

B B |

p = 0.370 | -0.09 ± 1.23 | -2.17 ± 1.23 | -1.4 ± 1.97 | 1.71 ± 0.76 | -1.89 ± 2.14 | -3.27 ± 1.34 | -1.21 ± 1.45 | -1.03 ± 2.92 | -2.06 ± 1.43 |

| 2-hexenal | A | p ≤ 0.001 | 0.19 ± 0.04 b | -0.36 ± 0.00 bc | 0.24 ± 0.20 b | 2.51 ± 0.14 a | 0.14 ± 0.31 b | -0.10 ± 0.10 bc | 0.13 ± 0.11 b | -0.33 ± 0.15 bc | -0.78 ± 0.01 c |

| 1-penten-3-ol | A | p = 0.688 | 0.01 ± 0.06 | 0.02 ± 0.01 | -0.05 ± 0.06 | -0.08 ± 0.16 | -0.06 ± 0.08 | -0.02 ± 0.05 | -0.10 ± 0.03 | 0.00 ± 0.07 | 0.00 ± 0.04 |

| (E) -2-penten-1-ol | B | p = 0.724 | 0.00 ± 0.00 | 0.00 ± 0.00 | 0.00 ± 0.00 | 0.08 ± 0.11 | 0.02 ± 0.04 | 0.08 ± 0.11 | 0.06 ± 0.08 | 0.05 ± 0.07 | 0.07 ± 0.09 |

| (Z) -2-penten-1-ol | B | p = 0.463 | 0.03 ± 0.05 | 0.07 ± 0.05 | -0.03 ± 0.12 | -0.10 ± 0.18 | -0.06 ± 0.16 | -0.15 ± 0.15 | -0.13 ± 0.04 | -0.01 ± 0.00 | -0.22 ± 0.01 |

| hexan-1-ol | B | p = 0.581 | 3.86 ± 0.84 | 3.75 ± 0.12 | 4.52 ± 1.07 | 3.85 ± 4.34 | -1.55 ± 7.33 | 1.53 ± 1.19 | 2.27 ± 1.17 | 5.07 ± 2.18 | -2.43 ± 0.46 |

| 2-hexen-1-ol | A | p = 0.997 | 6.37 ± 0.31 | 8.10 ± 0.20 | 3.53 ± 0.96 | 6.57 ± 4.80 | 7.65 ± 10.65 | 10.1 ± 1.60 | 7.73 ± 1.48 | 6.13 ± 2.40 | 5.88 ± 0.43 |

| (E) -3-hexen-1-ol | A | p = 0.550 | -0.94 ± 0.18 | 0.03 ± 0.01 | 0.13 ± 0.00 | -0.31 ± 1.39 | -0.28 ± 0.60 | 0.17 ± 0.13 | -0.15 ± 0.12 | 0.24 ± 0.20 | -0.10 ± 0.03 |

| (Z) -3-hexen-1-ol | A | p ≤ 0.05 | 1.52 ± 0.53 a | -0.52 ± 0.37 a | -0.19 ± 1.59 a | -2.91 ± 4.98 a | 3.33 ± 5.37 a | -4.59 ± 1.00 a | -6.97 ± 1.04 a | -1.54 ± 2.61 a | -7.73 ± 0.37 a |

| 1-penten-3-one | A | p = 0.179 | 0.48 ± 0.09 | 0.48 ± 0.02 | 0.45 ± 0.04 | 0.25 ± 0.24 | 0.35 ± 0.36 | 0.11 ± 0.02 | 0.13 ± 0.01 | 0.67 ± 0.16 | -0.10 ± 0.06 |

| from OX | |||||||||||

| pentanal | A | p = 0.415 | 0.14 ± 0.07 | 0.14 ± 0.04 | -0.08 ± 0.06 | 0.02 ± 0.34 | -0.10 ± 0.18 | 0.01 ± 0.07 | -0.13 ± 0.05 | -0.02 ± 0.12 | 0.09 ± 0.04 |

| 2,4-heksadienal | A | p ≤ 0.001 | -0.01 ± 0.01 a | -0.10 ± 0.00 c | -0.10 ± 0.00 c | -0.05 ± 0.02 b | -0.10 ± 0.00 c | -0.10 ± 0.01 c | -0.10 ± 0.02 c | -0.10 ± 0.03 c | -0.10 ± 0.04 c |

| nonanal | B | p = 0.893 | 0.03 ± 0.01 | 0.03 ± 0.02 | -0.01 ± 0.00 | 0.00 ± 0.04 | -0.02 ± 0.06 | -0.01 ± 0.01 | 0.00 ± 0.01 | 0.00 ± 0.02 | -0.03 ± 0.00 |

| from MBA | |||||||||||

| pentan-1-ol | B | p ≤ 0.01 | -0.16 ± 0.04 abc | -0.02 ± 0.02 a | -0.11 ± 0.08 ab | -0.26 ± 0.10 bc | -0.20 ± 0.07 abc | -0.25 ± 0.03 bc | -0.22 ± 0.03 abc | -0.18 ± 0.02 abc | -0.35 ± 0.00 c |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).