Submitted:

18 June 2025

Posted:

19 June 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Plant Material

2.2. Olive oil Production

2.3. Basic Quality Parameters

2.4. Oil Yield

2.5. Volatile Components

2.6. Phenolic Compounds

2.7. Tocopherol Content

2.8. Fatty Acid Composition

2.9. Oxidative Stability Index

2.10. Antioxidative Capacity

2.11. Statistical Analysis

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Basic Quality Parameters and Processing Yield

3.2. Volatile Compounds

3.3. Phenolic Compounds

3.4. Tocopherols

3.5. Oxidative Stability and Antioxidant Capacity

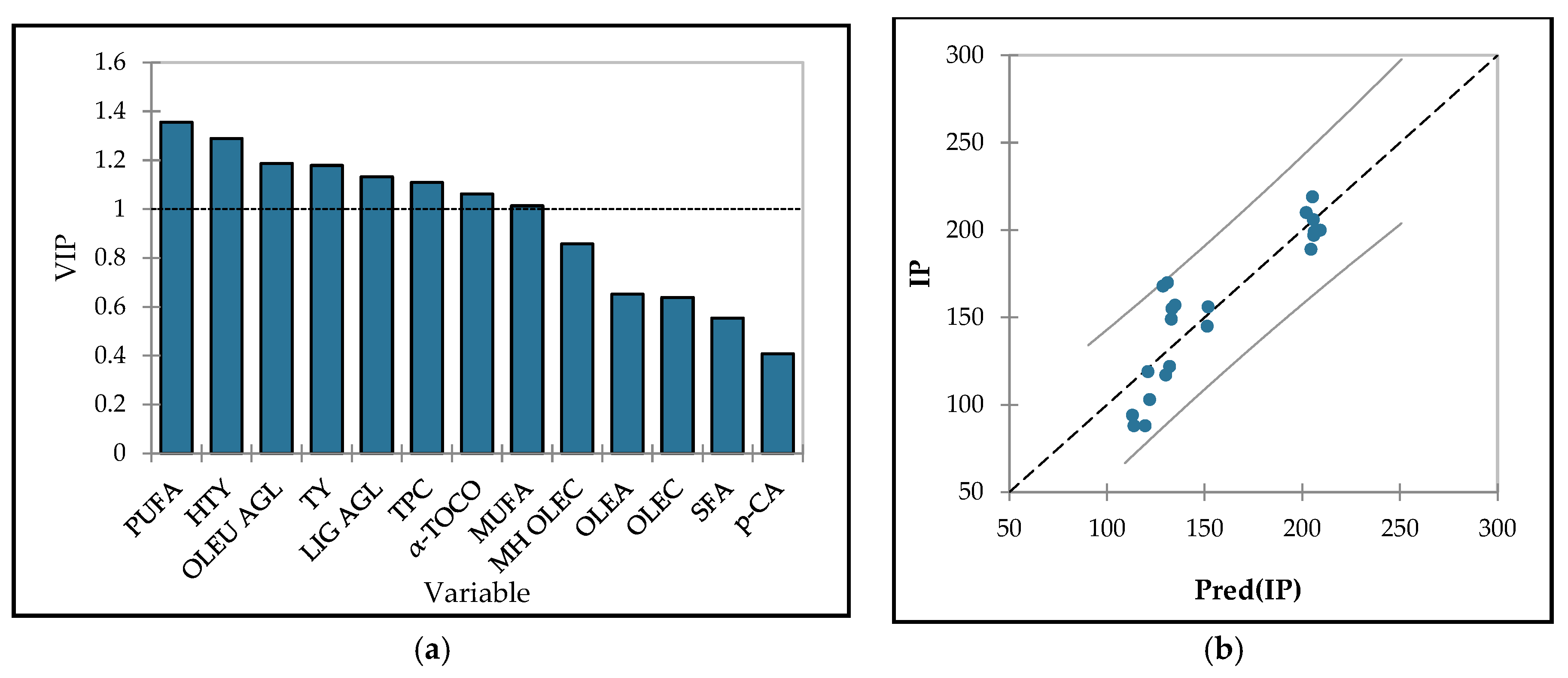

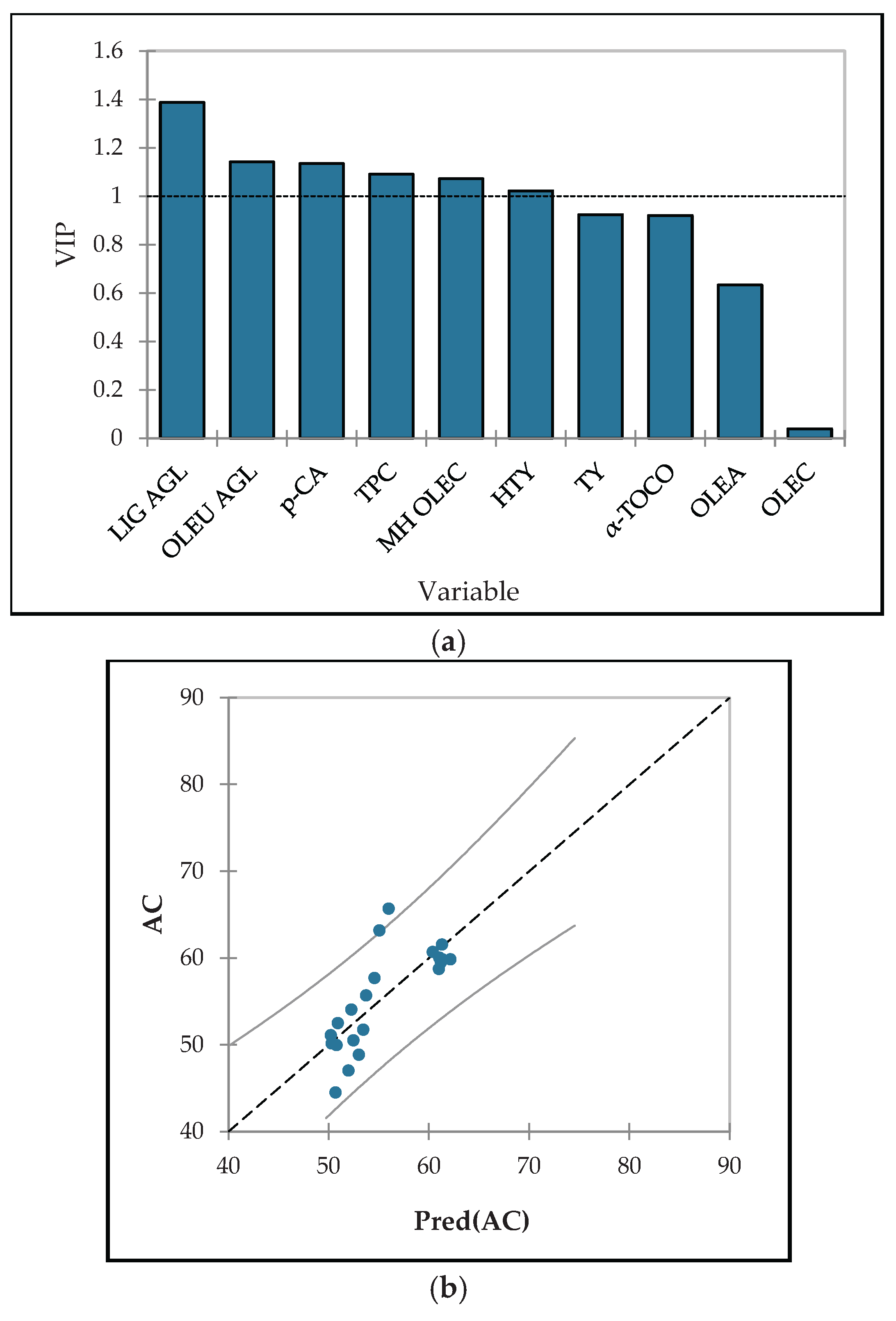

3.6. Optimization

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Marrero, A.D.; Quesada, A.R.; Martínez-Poveda, B.; Medina, M.Á. Anti-Cancer, Anti-Angiogenic, and Anti-Atherogenic Potential of Key Phenolic Compounds from Virgin Olive Oil. Nutrients 2024, 16, 1283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lu, Y.; Zhao, J.; Xin, Q.; Yuan, R.; Miao, Y.; Yang, M.; Mo, H.; Chen, K.; Cong, W. Protective Effects of Oleic Acid and Polyphenols in Extra Virgin Olive Oil on Cardiovascular Diseases. Food Sci Hum Well 2024, 13, 529–540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonçalves, M.; Vale, N.; Silva, P. Neuroprotective Effects of Olive Oil: A Comprehensive Review of Antioxidant Properties. Antioxidants 2024, 13, 762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsimihodimos, V.; Psoma, O. Extra Virgin Olive Oil and Metabolic Diseases. Int J Mol Sci 2024, 25, 8117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Obied, H.K.; Prenzler, P.D.; Ryan, D.; Servili, M.; Taticchi, A.; Esposto, S.; Robards, K. Biosynthesis and Biotransformations of Phenol-Conjugated Oleosidic Secoiridoids from Olea Europaea L. Nat Prod Rep 2008, 25, 1167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salas, J.J.; Sánchez, J. The Decrease of Virgin Olive Oil Flavor Produced by High Malaxation Temperature Is Due to Inactivation of Hydroperoxide. J Agric Food Chem 1999, 47, 809–812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sánchez-Ortiz, A.; Romero-Segura, C.; Sanz, C.; Pérez, A.G. Synthesis of Volatile Compounds of Virgin Olive Oil Is Limited by the Lipoxygenase Activity Load during the Oil Extraction Process. J Agric Food Chem 2012, 60, 812–822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kalua, C.M.; Bedgood, D.R.; Bishop, A.G.; Prenzler, P.D. Changes in Volatile and Phenolic Compounds with Malaxation Time and Temperature during Virgin Olive Oil Production. J Agric Food Chem 2006, 54, 7641–7651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalua, C.M.; Allen, M.S.; Bedgood, D.R.; Bishop, A.G.; Prenzler, P.D.; Robards, K. Olive Oil Volatile Compounds, Flavour Development and Quality: A Critical Review. Food Chem 2007, 100, 273–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bejaoui, M.A.; Sánchez-Ortiz, A.; Aguilera, M.P.; Ruiz-Moreno, M.J.; Sánchez, S.; Jiménez, A.; Beltrán, G. High Power Ultrasound Frequency for Olive Paste Conditioning: Effect on the Virgin Olive Oil Bioactive Compounds and Sensorial Characteristics. Innov Food Sci Emerg Technol 2018, 47, 136–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romero-Segura, C.; García-Rodríguez, R.; Sánchez-Ortiz, A.; Sanz, C.; Pérez, A.G. The Role of Olive β-Glucosidase in Shaping the Phenolic Profile of Virgin Olive Oil. Food Res Int 2012, 45, 191–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Veneziani, G.; Esposto, S.; Taticchi, A.; Selvaggini, R.; Urbani, S.; Di Maio, I.; Sordini, B.; Servili, M. Flash Thermal Conditioning of Olive Pastes during the Oil Mechanical Extraction Process: Cultivar Impact on the Phenolic and Volatile Composition of Virgin Olive Oil. J Agric Food Chem 2015, 63, 6066–6074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nardella, M.; Moscetti, R.; Bedini, G.; Bandiera, A.; Chakravartula, S.S.N.; Massantini, R. Impact of Traditional and Innovative Malaxation Techniques and Technologies on Nutritional and Sensory Quality of Virgin Olive Oil – A Review. Food Chem Adv 2023, 2, 100163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalogianni, E.P.; Georgiou, D.; Exarhopoulos, S. Olive Oil Droplet Coalescence during Malaxation. J Food Eng 2019, 240, 99–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clodoveo, M.L. Malaxation: Influence on Virgin Olive Oil Quality. Past, Present and Future - An Overview. Trends Food Sci Technol 2012, 25, 13–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leone, A.; Tamborrino, A.; Zagaria, R.; Sabella, E.; Romaniello, R. Plant Innovation in the Olive Oil Extraction Process: A Comparison of Efficiency and Energy Consumption between Microwave Treatment and Traditional Malaxation of Olive Pastes. J Food Eng 2015, 146, 44–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clodoveo, M.L. New Advances in the Development of Innovative Virgin Olive Oil Extraction Plants: Looking Back to See the Future. Food Res Int 2013, 54, 726–729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clodoveo, M.L.; Moramarco, V.; Paduano, A.; Sacchi, R.; Di Palmo, T.; Crupi, P.; Corbo, F.; Pesce, V.; Distaso, E.; Tamburrano, P. Engineering Design and Prototype Development of a Full Scale Ultrasound System for Virgin Olive Oil by Means of Numerical and Experimental Analysis. Ultrason Sonochem 2017, 37, 169–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andreou, V.; Dimopoulos, G.; Alexandrakis, Z.; Katsaros, G.; Oikonomou, D.; Toepfl, S.; Heinz, V.; Taoukis, P. Shelf-Life Evaluation of Virgin Olive Oil Extracted from Olives Subjected to Nonthermal Pretreatments for Yield Increase. Innovative Food Sci Emerg Technol 2017, 40, 52–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romaniello, R.; Tamborrino, A.; Leone, A. Use of Ultrasound and Pulsed Electric Fields Technologies Applied to the Olive Oil Extraction Process. Chem Eng Trans 2019, 75, 13–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amirante, P.; Clodoveo, M.L.; Dugo, G.; Leone, A.; Tamborrino, A. Advance Technology in Virgin Olive Oil Production from Traditional and De-Stoned Pastes: Influence of the Introduction of a Heat Exchanger on Oil Quality. Food Chem 2006, 98, 797–805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esposto, S.; Veneziani, G.; Taticchi, A.; Selvaggini, R.; Urbani, S.; Di Maio, I.; Sordini, B.; Minnocci, A.; Sebastiani, L.; Servili, M. Flash Thermal Conditioning of Olive Pastes during the Olive Oil Mechanical Extraction Process: Impact on the Structural Modifications of Pastes and Oil Quality. J Agric Food Chem 2013, 61, 4953–4960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leone, A.; Esposto, S.; Tamborrino, A.; Romaniello, R.; Taticchi, A.; Urbani, S.; Servili, M. Using a Tubular Heat Exchanger to Improve the Conditioning Process of the Olive Paste: Evaluation of Yield and Olive Oil Quality. Eur J Lipid Sci Technol 2016, 118, 308–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Veneziani, G.; Esposto, S.; Taticchi, A.; Urbani, S.; Selvaggini, R.; Di Maio, I.; Sordini, B.; Servili, M. Cooling Treatment of Olive Paste during the Oil Processing: Impact on the Yield and Extra Virgin Olive Oil Quality. Food Chem 2017, 221, 107–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Veneziani, G.; Esposto, S.; Taticchi, A.; Urbani, S.; Selvaggini, R.; Sordini, B.; Servili, M. Characterization of Phenolic and Volatile Composition of Extra Virgin Olive Oil Extracted from Six Italian Cultivars Using a Cooling Treatment of Olive Paste. LWT - Food Sci Technol 2018, 87, 523–528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Selvaggini, R.; Esposto, S.; Taticchi, A.; Urbani, S.; Veneziani, G.; Di Maio, I.; Sordini, B.; Servili, M. Optimization of the Temperature and Oxygen Concentration Conditions in the Malaxation during the Oil Mechanical Extraction Process of Four Italian Olive Cultivars. J Agric Food Chem 2014, 62, 3813–3822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Angerosa, F.; Servili, M.; Selvaggini, R.; Taticchi, A.; Esposto, S.; Montedoro, G. Volatile Compounds in Virgin Olive Oil: Occurrence and Their Relationship with the Quality. J Chromatogr A 2004, 1054, 17–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gómez-Rico, A.; Fregapane, G.; Salvador, M.D. Effect of Cultivar and Ripening on Minor Components in Spanish Olive Fruits and Their Corresponding Virgin Olive Oils. Food Res Int 2008, 41, 433–440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- International Olive Council, Madrid, Spain. Available online: https://www.internationaloliveoil.org/what-we-do/economic-affairs-promotion-unit/#figures (accessed on 10 May 2025).

- ISO 3960:2017 - Animal and Vegetable Fats and Oils — Determination of Peroxide Value — Iodometric (Visual) Endpoint Determination. Available online: https://www.iso.org/standard/71268.html (accessed on 4 December 2023).

- COI/T.20/Doc. No 34/Rev. 1 2017 Method determination of free fatty acids, cold method. Available online: https://www.internationaloliveoil.org/what-we-do/chemistry-standardisation-unit/standards-and-methods/ (accessed on 5 December 2023).

- COI/T.20/Doc. No 19/Rev. 5 2019 Method of analysis spectrophotometric investigation in the ultraviolet. Available online: https://www.internationaloliveoil.org/what-we-do/chemistry-standardisation-unit/standards-and-methods/ (accessed on 4 December 2023).

- Peres, F.; Martins, L.L.; Ferreira-Dias, S. Laboratory-scale Optimization of Olive Oil Extraction: Simultaneous Addition of Enzymes and Microtalc Improves the Yield. Eur J Lipid Sci Technol 2014, 116, 1054–1062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kraljić, K.; Stjepanović, T.; Obranović, M.; Pospišil, M.; Balbino, S.; Škevin, D. Influence of Conditioning Temperature on the Quality, Nutritional Properties and Volatile Profile of Virgin Rapeseed Oil. Food Technol Biotechnol 2018, 56, 562–572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- COI/T.20/Doc. No 29/Rev. 2 2022 Document to declare the use of IOC methods for phenolic compounds determination. Available online: https://www.internationaloliveoil.org/what-we-do/chemistry-standardisation-unit/standards-and-methods/ (accessed on 11 December 2023).

- ISO 9936:2016 - Animal and Vegetable Fats and Oils — Determination of Tocopherol and Tocotrienol Contents by High-Performance Liquid Chromatography Available online:. Available online: https://www.iso.org/standard/69595.html (accessed on 6 December 2023).

- ISO 12966-2:2017 - Animal and Vegetable Fats and Oils — Gas Chromatography of Fatty Acid Methyl Esters — Part 2: Preparation of Methyl Esters of Fatty Acids Available online:. Available online: https://www.iso.org/standard/72142.html (accessed on 6 December 2023).

- Taticchi, A.; Esposto, S.; Veneziani, G.; Urbani, S.; Selvaggini, R.; Servili, M. The Influence of the Malaxation Temperature on the Activity of Polyphenoloxidase and Peroxidase and on the Phenolic Composition of Virgin Olive Oil. Food Chem 2013, 136, 975–983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Inarejos-García, A.M.; Gómez-Rico, A.; Salvador, M.D.; Fregapane, G. Influence of Malaxation Conditions on Virgin Olive Oil Yield, Overall Quality and Composition. Eur Food Res Technol 2009, 228, 671–677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Veneziani, G.; Nucciarelli, D.; Taticchi, A.; Esposto, S.; Selvaggini, R.; Tomasone, R.; Pagano, M.; Servili, M. Application of Low Temperature during the Malaxation Phase of Virgin Olive Oil Mechanical Extraction Processes of Three Different Italian Cultivars. Foods 2021, 10, 1578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kraljić, K.; Balbino, S.; Filipan, K.; Herceg, Z.; Ivanov, M.; Vukušić Pavičić, T.; Stuparević, I.; Pavlić, K.; Škevin, D. Innovative Approaches to Enhance Activity of Endogenous Olive Enzymes—A Model System Experiment: Part I—Thermal Techniques. Processes 2023, 11, 1194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Commission Delegated Regulation Commission Delegated Regulation (EU) 2022/2104 of Supplementing Regulation (EU) No 1308/2013 of the European Parliament and of the Council as Regards Marketing Standards for Olive Oil, and Repealing Commission Regulation (EEC) No 2568/91 and Commission Implementing Regulation (EU) No 29/2012. 2022. 29 July.

- Panzanaro, S.; Nutricati, E.; Miceli, A.; De Bellis, L. Biochemical Characterization of a Lipase from Olive Fruit (Olea Europaea L.). Plant Physiol Biochem 2010, 48, 741–745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Olmo-Cunillera, A.; Lozano-Castellón, J.; Pérez, M.; Miliarakis, E.; Tresserra-Rimbau, A.; Ninot, A.; Romero-Aroca, A.; Lamuela-Raventós, R.M.; Vallverdú-Queralt, A. Optimizing the Malaxation Conditions to Produce an Arbequina EVOO with High Content of Bioactive Compounds. Antioxidants 2021, 10, 1819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marx, Í.M.G.; Rodrigues, N.; Veloso, A.C.A.; Casal, S.; Pereira, J.A.; Peres, A.M. Effect of Malaxation Temperature on the Physicochemical and Sensory Quality of Cv. Cobrançosa Olive Oil and Its Evaluation Using an Electronic Tongue. LWT - Food Sci Technol 2021, 137, 110426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Espínola, F.; Moya, M.; Fernández, D.G.; Castro, E. Improved Extraction of Virgin Olive Oil Using Calcium Carbonate as Coadjuvant Extractant. J Food Eng 2009, 92, 112–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leone, A.; Tamborrino, A.; Esposto, S.; Berardi, A.; Servili, M. Investigation on the Effects of a Pulsed Electric Field (PEF) Continuous System Implemented in an Industrial Olive Oil Plant. Foods 2022, 11, 2758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, S.; Li, S.; Li, G.; Li, C.; Li, W.; Bi, Y.; Wei, J. Pulsed Electric Field Treatment Improves the Oil Yield, Quality, and Antioxidant Activity of Virgin Olive Oil. Food Chem X 2024, 22, 101372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tamborrino, A.; Romaniello, R.; Caponio, F.; Squeo, G.; Leone, A. Combined Industrial Olive Oil Extraction Plant Using Ultrasounds, Microwave, and Heat Exchange: Impact on Olive Oil Quality and Yield. J Food Eng 2019, 245, 124–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andreou, V.; Psarianos, M.; Dimopoulos, G.; Tsimogiannis, D.; Taoukis, P. Effect of Pulsed Electric Fields and High Pressure on Improved Recovery of High-added-value Compounds from Olive Pomace. J Food Sci 2020, 85, 1500–1512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chemat, F.; Rombaut, N.; Sicaire, A.-G.; Meullemiestre, A.; Fabiano-Tixier, A.-S.; Abert-Vian, M. Ultrasound Assisted Extraction of Food and Natural Products. Mechanisms, Techniques, Combinations, Protocols and Applications. A Review. Ultrason Sonochem 2017, 34, 540–560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andreou, V.; Kourmbeti, E.; Dimopoulos, G.; Psarianos, M.; Katsaros, G.; Taoukis, P. Optimization of Virgin Olive Oil Yield and Quality Applying Nonthermal Processing. Food Bioproc Tech 2022, 15, 891–903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Juliano, P.; Gaber, M.A.F.M.; Romaniello, R.; Tamborrino, A.; Berardi, A.; Leone, A. Advances in Physical Technologies to Improve Virgin Olive Oil Extraction Efficiency in High-Throughput Production Plants. Food Eng Rev 2023, 15, 625–642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cecchi, L.; Migliorini, M.; Mulinacci, N. Virgin Olive Oil Volatile Compounds: Composition, Sensory Characteristics, Analytical Approaches, Quality Control, and Authentication. J Agric Food Chem 2021, 69, 2013–2040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mikrou, T.; Litsa, M.; Papantoni, A.; Kapsokefalou, M.; Gardeli, C.; Mallouchos, A. Effect of Cultivar and Geographical Origin on the Volatile Composition of Greek Monovarietal Extra Virgin Olive Oils. Chemosensors 2023, 11, 80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Germek, V.M.; Koprivnjak, O.; Butinar, B.; Pizzale, L.; Bučar-Miklavčič, M.; Conte, L.S. Influence of Phenols Mass Fraction in Olive (Olea Europaea L.) Paste on Volatile Compounds in Buža Cultivar Virgin Olive Oil. J Agric Food Chem 2013, 61, 5921–5927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lukić, I.; Lukić, M.; Žanetić, M.; Krapac, M.; Godena, S.; Brkić Bubola, K. Inter-Varietal Diversity of Typical Volatile and Phenolic Profiles of Croatian Extra Virgin Olive Oils as Revealed by GC-IT-MS and UPLC-DAD Analysis. Foods 2019, 8, 565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Žanetić, M.; Jukić Špika, M.; Ožić, M.M.; Brkić Bubola, K. Comparative Study of Volatile Compounds and Sensory Characteristics of Dalmatian Monovarietal Virgin Olive Oils. Plants 2021, 10, 1995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soldo, B.; Jukić Špika, M.; Pasković, I.; Vuko, E.; Polić Pasković, M.; Ljubenkov, I. The Composition of Volatiles and the Role of Non-Traditional LOX on Target Metabolites in Virgin Olive Oil from Autochthonous Dalmatian Cultivars. Molecules 2024, 29, 1696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Olmo-Cunillera, A.; Casadei, E.; Valli, E.; Lozano-Castellón, J.; Miliarakis, E.; Domínguez-López, I.; Ninot, A.; Romero-Aroca, A.; Lamuela-Raventós, R.M.; Pérez, M.; Vallverdú-Queralt, A.; Bendini, A. Aromatic, Sensory, and Fatty Acid Profiles of Arbequina Extra Virgin Olive Oils Produced Using Different Malaxation Conditions. Foods 2022, 11, 3446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Servili, M.; Taticchi, A.; Esposto, S.; Urbani, S.; Selvaggini, R.; Montedoro, G.F. Effect of Olive Stoning on the Volatile and Phenolic Composition of Virgin Olive Oil. J Agric Food Chem 2007, 55, 7028–7035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Finicelli, M.; Squillaro, T.; Di Cristo, F.; Di Salle, A.; Melone, M.A.B.; Galderisi, U.; Peluso, G. Metabolic Syndrome, Mediterranean Diet, and Polyphenols: Evidence and Perspectives. J Cell Physiol 2019, 234, 5807–5826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Emma, M.R.; Augello, G.; Di Stefano, V.; Azzolina, A.; Giannitrapani, L.; Montalto, G.; Cervello, M.; Cusimano, A. Potential Uses of Olive Oil Secoiridoids for the Prevention and Treatment of Cancer: A Narrative Review of Preclinical Studies. Int J Mol Sci 2021, 22, 1234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diamantakos, P.; Ioannidis, K.; Papanikolaou, C.; Tsolakou, A.; Rigakou, A.; Melliou, E.; Magiatis, P. A New Definition of the Term “High-Phenolic Olive Oil” Based on Large Scale Statistical Data of Greek Olive Oils Analyzed by QNMR. Molecules 2021, 26, 1115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lukić, I.; Horvat, I.; Godena, S.; Krapac, M.; Lukić, M.; Vrhovsek, U.; Brkić Bubola, K. Towards Understanding the Varietal Typicity of Virgin Olive Oil by Correlating Sensory and Compositional Analysis Data: A Case Study. Food Res Int 2018, 112, 78–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lukić, I.; Krapac, M.; Horvat, I.; Godena, S.; Kosić, U.; Brkić Bubola, K. Three-Factor Approach for Balancing the Concentrations of Phenols and Volatiles in Virgin Olive Oil from a Late-Ripening Olive Cultivar. LWT - Food Sci Technol 2018, 87, 194–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soldo, B.; Jukić Špika, M.; Pasković, I.; Vuko, E.; Polić Pasković, M.; Ljubenkov, I. The Composition of Volatiles and the Role of Non-Traditional LOX on Target Metabolites in Virgin Olive Oil from Autochthonous Dalmatian Cultivars. Molecules 2024, 29, 1696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jukić Špika, M.; Perica, S.; Žanetić, M.; Škevin, D. Virgin Olive Oil Phenols, Fatty Acid Composition and Sensory Profile: Can Cultivar Overpower Environmental and Ripening Effect? Antioxidants 2021, 10, 689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diamantakos, P.; Giannara, T.; Skarkou, M.; Melliou, E.; Magiatis, P. Influence of Harvest Time and Malaxation Conditions on the Concentration of Individual Phenols in Extra Virgin Olive Oil Related to Its Healthy Properties. Molecules 2020, 25, 2449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lukić, I.; Žanetić, M.; Jukić Špika, M.; Lukić, M.; Koprivnjak, O.; Brkić Bubola, K. Complex Interactive Effects of Ripening Degree, Malaxation Duration and Temperature on Oblica Cv. Virgin Olive Oil Phenols, Volatiles and Sensory Quality. Food Chem 2017, 232, 610–620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aguilera, M.P.; Jimenez, A.; Sanchez-Villasclaras, S.; Uceda, M.; Beltran, G. Modulation of Bitterness and Pungency in Virgin Olive Oil from Unripe “Picual” Fruits. Eur J Lipid Sci Technol 2015, 117, 1463–1472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stefanoudaki, E.; Koutsaftakis, A.; Harwood, J.L. Influence of Malaxation Conditions on Characteristic Qualities of Olive Oil. Food Chem 2011, 127, 1481–1486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amirante, R.; Cini, E.; Montel, G.L.; Pasqualone, A. Influence of Mixing and Extraction Parameters on Virgin Olive Oil Quality. Grasas y Aceites 2001, 52, 198–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Angerosa, F.; Mostallino, R.; Basti, C.; Vito, R. Influence of Malaxation Temperature and Time on the Quality of Virgin Olive Oils. Food Chem 2001, 72, 19–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parenti, A.; Spugnoli, P.; Masella, P.; Calamai, L. The Effect of Malaxation Temperature on the Virgin Olive Oil Phenolic Profile under Laboratory-scale Conditions. Eur J Lipid Sci Technol 2008, 110, 735–741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koprivnjak, O.; Kriško, A.; Valić, S.; Carić, D.; Krapac, M.; Poljuha, D. Antioxidants, Radical-Scavenging and Protein Carbonylation Inhibition Capacity of Six Monocultivar Virgin Olive Oils in Istria (Croatia). Acta Aliment 2016, 45, 427–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koprivnjak, O. , Vrhovnik, I., Hladnik, T., Prgomet, Ž., Hlevnjak, B., Majetić Germek, V. Characteristics of Nutritive Value of Virgin Olive Oils from Buža, Istarska Bjelica, Leccino and Rosulja Cultivars. Cro J Food Technol Biotechnol Nutr 2012, 7, 172–178. [Google Scholar]

- Pérez, A.G.; León, L.; Pascual, M.; de la Rosa, R.; Belaj, A.; Sanz, C. Analysis of Olive (Olea Europaea L.) Genetic Resources in Relation to the Content of Vitamin E in Virgin Olive Oil. Antioxidants 2019, 8, 242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Šarolić, M.; Gugić, M.; Friganović, E.; Tuberoso, C.; Jerković, I. Phytochemicals and Other Characteristics of Croatian Monovarietal Extra Virgin Olive Oils from Oblica, Lastovka and Levantinka Varieties. Molecules 2015, 20, 4395–4409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jukić Špika, M.; Kraljić, K.; Koprivnjak, O.; Škevin, D.; Žanetić, M.; Katalinić, M. Effect of Agronomical Factors and Storage Conditions on the Tocopherol Content of Oblica and Leccino Virgin Olive Oils. J Am Oil Chem Soc 2015, 92, 1293–1301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pazos, M.; Andersen, M.L.; Medina, I.; Skibsted, L.H. Efficiency of Natural Phenolic Compounds Regenerating α-Tocopherol from α-Tocopheroxyl Radical. J Agric Food Chem 2007, 55, 3661–3666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rastrelli, L.; Passi, S.; Ippolito, F.; Vacca, G.; De Simone, F. Rate of Degradation of α-Tocopherol, Squalene, Phenolics, and Polyunsaturated Fatty Acids in Olive Oil during Different Storage Conditions. J Agric Food Chem 2002, 50, 5566–5570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sánchez, J.; Harwood, J.L. Biosynthesis of Triacylglycerols and Volatiles in Olives. Eur J Lipid Sci Technol 2002, 104, 564–573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rondanini, D.P.; Castro, D.N.; Searles, P.S.; Rousseaux, M.C. Contrasting Patterns of Fatty Acid Composition and Oil Accumulation during Fruit Growth in Several Olive Varieties and Locations in a Non-Mediterranean Region. Eur J Agr 2014, 52, 237–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kiritsakis, A.; Shahidi, F. Olive Oil Quality and Its Relation to the Functional Bioactives and Their Properties. In Olives and Olive Oil as Functional Foods; Wiley, 2017; pp. 205–219.

- Špika Jukić, M.; Žanetić, M.; Pinatel, C.; Vitanović, E.; Strikić, F. Fatty Acid and Triacylgycerol Profile of Levantinka Virgin Olive Oil. In Proceedings of the 14th Ružička days: Today science – Tomorrow industry; Jukić, A., Ed.; Croatian Society of Chemical Engineers Faculty of Food Technology: Osijek, 2013; pp. 213–218. [Google Scholar]

- Jukić Špika, M.; Žanetić, M.; Kraljić, K.; Soldo, B.; Ljubenkov, I.; Politeo, O.; Škevin, D. Differentiation Between Unfiltered and Filtered Oblica and Leccino Cv. Virgin Olive Oils. J Food Sci 2019, 84, 877–885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jukić Špika, M.; Perica, S.; Žanetić, M.; Škevin, D. Virgin Olive Oil Phenols, Fatty Acid Composition and Sensory Profile: Can Cultivar Overpower Environmental and Ripening Effect? Antioxidants 2021, 10, 689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brkić Bubola, K.; Valenčič, V.; Bučar-Miklavčič, M.; Krapac, M.; Lukić, M.; Šetić, E.; Sladonja, B. Sterol, Triterpen Dialcohol and Fatty Acid Profile of Less- and Well-Known Istrian Monovarietal Olive Oil. Cro J Food Sci Technol 2018, 10, 118–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morales, M.T.; Przybylski, R. Olive Oil Oxidation. In Handbook of Olive Oil; Springer US: Boston, MA, 2013; pp. 479–522. [Google Scholar]

- Velasco, J.; Dobarganes, C. Oxidative Stability of Virgin Olive Oil. Eur J Lipid Sci Technol 2002, 104, 661–676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rubio, C.P.; Hernández-Ruiz, J.; Martinez-Subiela, S.; Tvarijonaviciute, A.; Arnao, M.B.; Ceron, J.J. Validation of Three Automated Assays for Total Antioxidant Capacity Determination in Canine Serum Samples. J Vet Diagn Invest 2016, 28, 693–698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Prior, R.L.; Wu, X.; Schaich, K. Standardized Methods for the Determination of Antioxidant Capacity and Phenolics in Foods and Dietary Supplements. J Agric Food Chem 2005, 53, 4290–4302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Visioli, F.; Bellomo, G.; Galli, C. Free Radical-Scavenging Properties of Olive Oil Polyphenols. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 1998, 247, 60–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Quirantes-Piné, R.; Lozano-Sánchez, J.; Herrero, M.; Ibáñez, E.; Segura-Carretero, A.; Fernández-Gutiérrez, A. HPLC–ESI–QTOF–MS as a Powerful Analytical Tool for Characterising Phenolic Compounds in Olive-leaf Extracts. Phytochem Anal 2013, 24, 213–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalogiouri, N.P.; Kritikou, E.; Martakos, I.C.; Lazarou, C.; Pentogennis, M.; Thomaidis, N.S. Characterization of the Phenolic Fingerprint of Kolovi Extra Virgin Olive Oils from Lesvos with Regard to Altitude and Farming System Analyzed by UHPLC-QTOF-MS. Molecules 2021, 26, 5634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kanakis, P.; Termentzi, A.; Michel, T.; Gikas, E.; Halabalaki, M.; Skaltsounis, A.-L. From Olive Drupes to Olive Oil. An HPLC-Orbitrap-Based Qualitative and Quantitative Exploration of Olive Key Metabolites. Planta Med 2013, 79, 1576–1587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sánchez de Medina, V.; Miho, H.; Melliou, E.; Magiatis, P.; Priego-Capote, F.; Luque de Castro, M.D. Quantitative Method for Determination of Oleocanthal and Oleacein in Virgin Olive Oils by Liquid Chromatography–Tandem Mass Spectrometry. Talanta 2017, 162, 24–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jerman Klen, T.; Golc Wondra, A.; Vrhovšek, U.; Mozetič Vodopivec, B. Phenolic Profiling of Olives and Olive Oil Process-Derived Matrices Using UPLC-DAD-ESI-QTOF-HRMS Analysis. J Agric Food Chem 2015, 63, 3859–3872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Source of variation |

Acidity (% oleic fatty acid) |

PV (meq O2/kg) |

K-values | Yield (%) | ||

| K232 | K268 | ΔK | ||||

| Variety* | p ≤ 0.001 | p ≤ 0.01 | p ≤ 0.001 | p ≤ 0.001 | p ≤ 0.001 | p ≤ 0.001 |

| Istarska Bjelica | 0.40 ± 0.00 a | 4.3 ± 0.1 b | 2.01 ± 0.02 a | 0.22 ± 0.01 a | -0.01 ± 0.00 c | 25.69 ± 0.15 a |

| Levantinka | 0.24 ± 0.00 c | 5.0 ± 0.3 ab | 1.68 ± 0.02 b | 0.13 ± 0.01 b | 0.00 ± 0.00 a | 12.52 ± 0.11 c |

| Oblica | 0.30 ± 0.00 b | 5.4 ± 0.2 a | 1.89 ± 0.11 ab | 0.18 ± 0.01 a | -0.01 ± 0.00 b | 13.36 ± 0.08 b |

| Temperature (°C) ** | p ≤ 0.001 | p ≤ 0.001 | p = 0.529 | p = 0.824 | p ≤ 0.001 | p ≤ 0.05 |

| Control | 0.32 ± 0.01 ab | 3.2 ± 0.1 b | 1.87 ± 0.04 | 0.18 ± 0.01 | -0.01 ± 0.00 a | 16.83 ± 0.26 ab |

| 15 | 0.30 ± 0.00 b | 5.4 ± 0.2 a | 1.83 ± 0.03 | 0.19 ± 0.02 | -0.01 ± 0.00 a | 16.81 ± 0.18 b |

| 20 | 0.31 ± 0.00 ab | 4.8 ± 0.3 a | 1.84 ± 0.02 | 0.18 ± 0.01 | 0.00 ± 0.00 a | 17.19 ± 0.15 ab |

| 25 | 0.29 ± 0.00 c | 4.7 ± 0.4 a | 1.83 ± 0.03 | 0.18 ± 0.01 | 0.00 ± 0.00 a | 17.21 ± 0.20 ab |

| 30 | 0.32 ± 0.00 ab | 5.2 ± 0.4 a | 1.95 ± 0.04 | 0.18 ± 0.02 | -0.01 ± 0.00 a | 17.30 ± 0.13 ab |

| 35 | 0.33 ± 0.00 a | 5.2 ± 0.5 a | 1.74 ± 0.25 | 0.16 ± 0.02 | -0.01 ± 0.00 b | 17.45 ± 0.17 ab |

| 40 | 0.33 ± 0.00 a | 5.8 ± 0.3 a | 1.96 ± 0.02 | 0.17 ± 0.01 | -0.01 ± 0.00 b | 17.56 ± 0.11 a |

| Variety × Temperature (°C) | p ≤ 0.001 | p ≤ 0.001 | p = 0.494 | p = 0.168 | p ≤ 0.001 | p ≤ 0.05 |

| Istarska Bjelica × Control | 0.42 ± 0.02 a | 2.9 ± 0.3 e | 1.92 ± 0.08 | 0.23 ± 0.02 | 0.00 ± 0.00 a | 24.70 ± 0.72 b |

| Istarska Bjelica × 15 | 0.38 ± 0.01 c | 4.8 ± 0.1 b-e | 1.89 ± 0.04 | 0.19 ± 0.01 | -0.01 ± 0.00 c | 25.18 ± 0.42 b |

| Istarska Bjelica × 20 | 0.39 ± 0.01 abc | 5.3 ± 0.1 a-e | 2.02 ± 0.00 | 0.23 ± 0.01 | -0.01 ± 0.00 bc | 25.72 ± 0.10 ab |

| Istarska Bjelica × 25 | 0.39 ± 0.00 bc | 6.0 ± 0.2 a-d | 2.00 ± 0.03 | 0.21 ± 0.01 | -0.01 ± 0.00 bc | 26.69 ± 0.41 a |

| Istarska Bjelica × 30 | 0.39 ± 0.01 abc | 4.5 ± 0.7 b-e | 2.06 ± 0.09 | 0.23 ± 0.06 | -0.01 ± 0.00 bc | 25.86 ± 0.21 ab |

| Istarska Bjelica × 35 | 0.42 ± 0.00 ab | 3.4 ± 0.6 de | 2.10 ± 0.05 | 0.25 ± 0.02 | -0.01 ± 0.00 bc | 25.98 ± 0.28 ab |

| Istarska Bjelica × 40 | 0.42 ± 0.01 ab | 3.4 ± 0.1 de | 2.07 ± 0.05 | 0.20 ± 0.02 | -0.01 ± 0.00 bc | 25.69 ± 0.19 ab |

| Levantinka × Control | 0.24 ± 0.01 fg | 3.3 ± 0.1 de | 1.70 ± 0.03 | 0.10 ± 0.00 | -0.01 ±0.0. abc | 12.22 ± 0.12 e |

| Levantinka × 15 | 0.24 ± 0.01 fg | 6.9 ± 0.6 ab | 1.67 ± 0.06 | 0.15 ± 0.03 | 0.00 ± 0.00 a | 12.44 ± 0.17 de |

| Levantinka × 20 | 0.25 ± 0.01 fg | 4.9 ± 0.7 b-e | 1.62 ± 0.02 | 0.12 ± 0.01 | 0.00 ± 0.00 a | 12.95 ± 0.34 cde |

| Levantinka × 25 | 0.22 ± 0.00 g | 3.9 ± 1.1 cde | 1.69 ± 0.04 | 0.16 ± 0.01 | 0.00 ± 0.00 a | 12.22 ± 0.41 e |

| Levantinka × 30 | 0.23 ± 0.01 g | 4.6 ± 1.1 b-e | 1.69 ± 0.06 | 0.13 ± 0.00 | 0.00 ± 0.00 a | 12.36 ± 0.19 de |

| Levantinka × 35 | 0.23 ± 0.01 fg | 5.3 ± 1.1 a-e | 1.66 ± 0.01 | 0.11 ± 0.01 | -0.01 ± 0.00 bc | 12.43 ± 0.40 de |

| Levantinka × 40 | 0.24 ± 0.00 fg | 6.3 ± 0.4 abc | 1.71 ± 0.02 | 0.12 ± 0.01 | -0.01 ± 0.00 bc | 13.03 ± 0.22 cde |

| Oblica × Control | 0.30 ± 0.01 d | 3.5 ± 0.1 de | 1.98 ± 0.06 | 0.20 ± 0.03 | -0.01 ± 0.00 bc | 13.58 ± 0.23 cd |

| Oblica × 15 | 0.30 ± 0.01 de | 4.5 ± 0.3 b-e | 1.93 ± 0.07 | 0.22 ± 0.05 | 0.00 ± 0.00 ab | 12.81 ± 0.28 cde |

| Oblica × 20 | 0.30 ± 0.00 d | 4.3 ± 0.5 b-e | 1.88 ± 0.04 | 0.19 ± 0.03 | 0.00 ± 0.00 a | 12.89 ± 0.26 cde |

| Oblica × 25 | 0.27 ± 0.01 ef | 4.3 ± 0.5 b-e | 1.80 ± 0.08 | 0.17 ± 0.03 | 0.00 ± 0.00 a | 12.71 ± 0.16 cde |

| Oblica × 30 | 0.32 ± 0.00 d | 6.5 ± 0.2 abc | 2.10 ± 0.04 | 0.19 ± 0.01 | -0.01 ± 0.00 bc | 13.67 ± 0.27 cd |

| Oblica × 35 | 0.33 ± 0.00 d | 6.8 ± 1.0 ab | 1.45 ± 0.76 | 0.12 ± 0.06 | -0.01 ± 0.00 bc | 13.93 ± 0.11 c |

| Oblica × 40 | 0.32 ± 0.00 d | 7.7 ± 0.9 a | 2.09 ± 0.01 | 0.19 ± 0.01 | -0.01 ± 0.00 bc | 13.94 ± 0.15 c |

| Source of variation |

VOC from LOX path (mg/kg) |

||||||||||||||

| 2-pentenal | 3-hexenal | 2-methyl-4-pentenal | 2-hexenal | 1-penten-3-ol | (E)2-penten-1-ol | (Z)2-penten-1-ol | 3-hexen-1-ol | ||||||||

| A | B | B | A | A | B | B | A | ||||||||

| Variety* | p ≤ 0.001 | p ≤ 0.001 | p ≤ 0.001 | p ≤ 0.001 | p = 0.171 | p = 0.699 | p = 0.948 | p = 0.180 | |||||||

| Istarska Bjelica | 0.17 ± 0.01 b | 2.24 ± 0.06 c | nd c | 6.37 ± 0.21 c | 1.99 ± 0.47 | 0.15 ± 0.01 | 1.49 ± 0.04 | 1.27 ± 0.07 | |||||||

| Levantinka | 0.32 ± 0.03 a | 6.23 ± 0.56 b | 1.81 ± 0.18 b | 21.92 ± 0.79 a | 1.46 ± 0.03 | 0.18 ± 0.03 | 1.53 ± 0.02 | 2.34 ± 0.72 | |||||||

| Oblica | 0.33 ± 0.02 a | 8.31 ± 0.49 a | 2.70 ± 0.14 a | 7.65 ± 0.27 b | 1.46 ± 0.03 | 0.16 ± 0.04 | 1.54 ± 0.23 | 1.94 ± 0.46 | |||||||

| Temperature (°C) ** | p = 0.071 | p ≤ 0.05 | p ≤ 0.01 | p ≤ 0.01 | p = 0.388 | p = 0.271 | p = 0.424 | p = 0.094 | |||||||

| Control | 0.32 ± 0.02 | 5.41 ± 0.62 a | 1.94 ± 0.23 a | 12.82 ± 0.46 ab | 1.60 ± 0.07 | 0.15 ± 0.01 | 1.54 ± 0.04 | 1.90 ± 0.25 | |||||||

| 15 | 0.29 ± 0.03 | 7.51 ± 0.81 a | 1.80 ± 0.17 a | 12.90 ± 0.27 ab | 2.41 ± 1.10 | 0.12 ± 0.00 | 1.48 ± 0.04 | 1.34 ± 0.22 | |||||||

| 20 | 0.23 ± 0.04 | 6.20 ± 1.15 a | 0.92 ± 0.27 a | 10.58 ± 0.45 b | 1.48 ± 0.09 | 0.24 ± 0.11 | 1.85 ± 0.54 | 1.38 ± 0.39 | |||||||

| 25 | 0.22 ± 0.06 | 5.03 ± 0.60 a | 1.64 ± 0.26 a | 13.56 ± 1.61 a | 1.62 ± 0.04 | 0.17 ± 0.02 | 1.60 ± 0.04 | 3.76 ± 1.89 | |||||||

| 30 | 0.31 ± 0.02 | 4.90 ± 0.30 a | 1.54 ± 0.06 a | 12.42 ± 0.15 ab | 1.55 ± 0.04 | 0.14 ± 0.00 | 1.48 ± 0.03 | 1.62 ± 0.16 | |||||||

| 35 | 0.24 ± 0.03 | 4.98 ± 0.39 a | 1.24 ± 0.23 a | 10.81 ± 0.86 b | 1.48 ± 0.03 | 0.19 ± 0.03 | 1.41 ± 0.03 | 1.41 ± 0.41 | |||||||

| 40 | 0.29 ± 0.02 | 5.11 ± 0.30 a | 1.44 ± 0.06 a | 10.78 ± 0.48 b | 1.31 ± 0.04 | 0.13 ± 0.00 | 1.31 ± 0.03 | 1.55 ± 0.10 | |||||||

| Variety × Temperature (°C) | p = 0.449 | p = 0.146 | p ≤ 0.05 | p ≤ 0.05 | p = 0.479 | p = 0.433 | p = 0.093 | p = 0.975 | |||||||

| Istarska Bjelica × Control | 0.20 ± 0.02 | 2.84 ± 0.12 | nd c | 6.77 ± 0.07 bcd | 1.88 ± 0.11 | 0.18 ± 0.01 | 1.81 ± 0.09 | 1.55 ± 0.16 | |||||||

| Istarska Bjelica × 15 | 0.12 ± 0.01 | 2.24 ± 0.11 | nd c | 5.28 ± 0.55 cd | 4.24 ± 3.29 | 0.12 ± 0.01 | 1.41 ± 0.12 | 1.10 ± 0.12 | |||||||

| Istarska Bjelica × 20 | 0.14 ± 0.04 | 1.85 ± 0.35 | nd c | 4.06 ± 0.59 d | 1.42 ± 0.22 | 0.12 ± 0.02 | 1.23 ± 0.21 | 0.95 ± 0.11 | |||||||

| Istarska Bjelica × 25 | 0.17 ± 0.05 | 2.23 ± 0.17 | nd c | 11.5 ± 1.06 b | 1.96 ± 0.09 | 0.21 ± 0.05 | 1.85 ± 0.07 | 1.76 ± 0.38 | |||||||

| Istarska Bjelica × 30 | 0.20 ± 0.00 | 2.21 ± 0.08 | nd c | 6.36 ± 0.15 bcd | 1.67 ± 0.01 | 0.16 ± 0.01 | 1.61 ± 0.04 | 1.42 ± 0.11 | |||||||

| Istarska Bjelica × 35 | 0.18 ± 0.02 | 1.94 ± 0.11 | nd c | 4.75 ± 0.37 cd | 1.42 ± 0.07 | 0.14 ± 0.01 | 1.30 ± 0.09 | 0.91 ± 0.08 | |||||||

| Istarska Bjelica × 40 | 0.19 ± 0.01 | 2.35 ± 0.07 | nd c | 5.87 ± 0.48 bcd | 1.32 ± 0.06 | 0.13 ± 0.00 | 1.26 ± 0.03 | 1.21 ± 0.03 | |||||||

| Levantinka × Control | 0.39 ± 0.01 | 5.33 ± 0.90 | 2.41 ± 0.12 ab | 23.91 ± 0.51 a | 1.50 ± 0.03 | 0.14 ± 0.01 | 1.52 ± 0.01 | 1.84 ± 0.36 | |||||||

| Levantinka × 15 | 0.41 ± 0.08 | 7.84 ± 2.23 | 2.14 ± 0.49 ab | 23.45 ± 0.54 a | 1.40 ± 0.05 | 0.13 ± 0.01 | 1.58 ± 0.03 | 1.62 ± 0.63 | |||||||

| Levantinka × 20 | 0.23 ± 0.09 | 7.57 ± 2.63 | 0.40 ± 0.46 c | 20.25 ± 1.14 a | 1.41 ± 0.12 | 0.24 ± 0.16 | 1.52 ± 0.07 | 1.54 ± 1.10 | |||||||

| Levantinka × 25 | 0.27 ± 0.16 | 5.85 ± 0.94 | 2.02 ± 0.76 ab | 21.40 ± 4.56 a | 1.51 ± 0.06 | 0.19 ± 0.05 | 1.67 ± 0.11 | 5.12 ± 4.69 | |||||||

| Levantinka × 30 | 0.39 ± 0.07 | 5.97 ± 0.30 | 2.30 ± 0.14 ab | 23.91 ± 0.41 a | 1.50 ± 0.07 | 0.13 ± 0.00 | 1.53 ± 0.07 | 1.86 ± 0.42 | |||||||

| Levantinka × 35 | 0.23 ± 0.09 | 4.92 ± 1.10 | 1.28 ± 0.70 bc | 20.59 ± 2.54 a | 1.60 ± 0.06 | 0.30 ± 0.10 | 1.53 ± 0.02 | 2.00 ± 1.20 | |||||||

| Levantinka × 40 | 0.31 ± 0.05 | 6.11 ± 0.79 | 2.10 ± 0.05 ab | 19.94 ± 1.26 a | 1.31 ± 0.09 | 0.12 ± 0.01 | 1.40 ± 0.07 | 2.41 ± 0.27 | |||||||

| Oblica × Control | 0.38 ± 0.05 | 8.07 ± 1.64 | 3.41 ± 0.67 a | 7.77 ± 1.28 bcd | 1.42 ± 0.18 | 0.14 ± 0.03 | 1.30 ± 0.05 | 2.32 ± 0.63 | |||||||

| Oblica × 15 | 0.34 ± 0.03 | 12.45 ± 0.98 | 3.25 ± 0.07 a | 9.98 ± 0.20 bc | 1.59 ± 0.05 | 0.12 ± 0.00 | 1.44 ± 0.02 | 1.30 ± 0.08 | |||||||

| Oblica × 20 | 0.32 ± 0.05 | 9.19 ± 2.22 | 2.37 ± 0.67 ab | 7.42 ± 0.41 bcd | 1.62 ± 0.08 | 0.35 ± 0.28 | 2.80 ± 1.61 | 1.64 ± 0.35 | |||||||

| Oblica × 25 | 0.23 ± 0.08 | 7.00 ± 1.53 | 2.89 ± 0.20 a | 7.8 ± 1.14 bcd | 1.40 ± 0.03 | 0.12 ± 0.01 | 1.29 ± 0.04 | 4.41 ± 3.14 | |||||||

| Oblica × 30 | 0.34 ± 0.03 | 6.52 ± 0.84 | 2.31 ± 0.11 ab | 7.00 ± 0.10 bcd | 1.48 ± 0.09 | 0.13 ± 0.00 | 1.30 ± 0.02 | 1.57 ± 0.16 | |||||||

| Oblica × 35 | 0.32 ± 0.02 | 8.08 ± 0.38 | 2.44 ± 0.06 ab | 7.10 ± 0.20 bcd | 1.42 ± 0.02 | 0.15 ± 0.00 | 1.40 ± 0.01 | 1.32 ± 0.27 | |||||||

| Oblica × 40 | 0.38 ± 0.02 | 6.87 ± 0.41 | 2.22 ± 0.17 ab | 6.53 ± 0.51 bcd | 1.31 ± 0.06 | 0.14 ± 0.01 | 1.27 ± 0.07 | 1.04 ± 0.09 | |||||||

| Source of variation |

VOC from LOX path (mg/kg) |

||||||||||||||

| 2-hexen-1-ol | 1-hexanol | 1-pente-3-one | hexyl acetate | 3-hexenyl acetate | 2-hexenyl acetate | Σ LOX | |||||||||

| A | B | A | B | A | A | ||||||||||

| Variety* | p ≤ 0.05 | p ≤ 0.001 | p ≤ 0.05 | p ≤ 0.001 | p ≤ 0.001 | p ≤ 0.05 | p ≤ 0.001 | ||||||||

| Istarska Bjelica | 0.08 ± 0.01 a | 0.49 ± 0.13 a | 4.64 ± 0.29 a | 1.62 ± 0.06 a | 4.30 ± 0.26 a | 0.05 ± 0.01 a | 24.87 ± 0.66 c | ||||||||

| Levantinka | 0.86 ± 0.51 a | 0.15 ± 0.05 b | 4.07 ± 0.19 a | 0.10 ± 0.01 b | 0.45 ± 0.17 b | 0.02 ± 0.03 ab | 41.44 ± 0.94 a | ||||||||

| Oblica | 0.05 ± 0.06 a | 0.08 ± 0.08 b | 4.62 ± 0.14 a | nd c | nd c | nd b | 28.86 ± 0.78 b | ||||||||

| Temperature (°C)** | p ≤ 0.01 | p = 0.162 | p ≤ 0.05 | p ≤ 0.05 | p ≤ 0.05 | p ≤ 0.05 | p ≤ 0.001 | ||||||||

| Control | 0.05 ± 0.01 a | 0.17 ± 0.01 | 5.08 ± 0.12 a | 0.69 ± 0.03 a | 1.84 ± 0.43 a | 0.09 ± 0.06 a | 33.61 ± 1.62 a | ||||||||

| 15 | 0.04 ± 0.01 a | 0.15 ± 0.01 | 3.84 ± 0.53 a | 0.56 ± 0.04 ab | 1.94 ± 0.28 a | 0.02 ± 0.01 ab | 34.39 ± 0.85 a | ||||||||

| 20 | 0.04 ± 0.01 a | 0.13 ± 0.03 | 4.24 ± 0.27 a | 0.53 ± 0.11 ab | 1.34 ± 0.30 a | nd b | 29.16 ± 2.20 b | ||||||||

| 25 | 0.14 ± 0.14 a | 0.53 ± 0.34 | 4.07 ± 0.52 a | 0.59 ± 0.01 ab | 1.22 ± 0.04 a | nd b | 34.16 ± 1.21 a | ||||||||

| 30 | 0.06 ± 0.01 a | 0.19 ± 0.01 | 4.82 ± 0.10 a | 0.62 ± 0.01 ab | 2.09 ± 0.29 a | 0.03 ± 0.00 ab | 31.77 ± 0.43 ab | ||||||||

| 35 | 1.93 ± 1.20 a | 0.33 ± 0.12 | 4.50 ± 0.27 a | 0.54 ± 0.05 ab | 1.44 ± 0.24 a | 0.02 ± 0.01 ab | 30.52 ± 0.49 ab | ||||||||

| 40 | 0.06 ± 0.00 a | 0.18 ± 0.02 | 4.56 ± 0.17 a | 0.50 ± 0.03 b | 1.22 ± 0.12 a | 0.01 ± 0.00 b | 28.46 ± 0.63 b | ||||||||

| Variety × Temperature (°C) | p ≤ 0.001 | p = 0.429 | p ≤ 0.05 | p ≤ 0.01 | p = 0.097 | p = 0.417 | p ≤ 0.01 | ||||||||

| Istarska Bjelica × Control | 0.10 ± 0.00 b | 0.48 ± 0.02 | 5.78 ± 0.24 a | 1.99 ± 0.09 a | 5.29 ± 1.27 | 0.13 ± 0.01 | 28.99 ± 1.55 c-g | ||||||||

| Istarska Bjelica × 15 | 0.08 ± 0.01 b | 0.35 ± 0.02 | 2.60 ± 1.57 b | 1.57 ± 0.10 bc | 4.90 ± 0.22 | 0.05 ± 0.04 | 24.05 ± 1.90 efg | ||||||||

| Istarska Bjelica × 20 | 0.08 ± 0.02 b | 0.31 ± 0.06 | 4.39 ± 0.66 ab | 1.45 ± 0.32 bc | 3.71 ± 0.90 | 0.01 ± 0.01 | 19.70 ± 3.44 g | ||||||||

| Istarska Bjelica × 25 | 0.05 ± 0.04 b | 1.11 ± 0.88 | 5.13 ± 0.95 a | 1.66 ± 0.01 abc | 3.34 ± 0.09 | nd | 30.96 ± 0.99 b-e | ||||||||

| Istarska Bjelica × 30 | 0.11 ± 0.00 b | 0.46 ± 0.02 | 5.12 ± 0.17 a | 1.81 ± 0.04 ab | 5.44 ± 0.26 | 0.10 ± 0.01 | 26.66 ± 0.46 d-g | ||||||||

| Istarska Bjelica × 35 | 0.09 ± 0.00 b | 0.35 ± 0.02 | 4.80 ± 0.30 ab | 1.52 ± 0.15 bc | 4.06 ± 0.73 | 0.05 ± 0.02 | 21.50 ± 1.21 fg | ||||||||

| Istarska Bjelica × 40 | 0.09 ± 0.01 b | 0.38 ± 0.03 | 4.67 ± 0.27 ab | 1.37 ± 0.09 c | 3.34 ± 0.37 | 0.02 ± 0.01 | 22.21 ± 0.77 efg | ||||||||

| Levantinka × Control | 0.04 ± 0.02 b | 0.02 ± 0.02 | 4.54 ± 0.07 ab | 0.08 ± 0.01 d | 0.24 ± 0.05 | 0.14 ± 0.18 | 42.10 ± 0.17 a | ||||||||

| Levantinka × 15 | 0.03 ± 0.02 b | 0.09 ± 0.01 | 4.37 ± 0.13 ab | 0.10 ± 0.02 d | 0.94 ± 0.82 | nd | 44.10 ± 1.42 a | ||||||||

| Levantinka × 20 | 0.06 ± 0.04 b | 0.10 ± 0.06 | 3.83 ± 0.43 ab | 0.13 ± 0.01 d | 0.31 ± 0.04 | nd | 37.58 ± 5.35 abc | ||||||||

| Levantinka × 25 | 0.04 ± 0.03 b | 0.06 ± 0.04 | 3.63 ± 0.91 ab | 0.11 ± 0.03 d | 0.30 ± 0.06 | nd | 42.16 ± 3.01 a | ||||||||

| Levantinka × 30 | 0.07 ± 0.03 b | 0.07 ± 0.00 | 4.50 ± 0.20 ab | 0.06 ± 0.02 d | 0.83 ± 0.82 | nd | 43.11 ± 0.82 a | ||||||||

| Levantinka × 35 | 5.70 ± 3.59 a | 0.60 ± 0.36 | 3.44 ± 0.72 ab | 0.10 ± 0.01 d | 0.25 ± 0.05 | nd | 42.53 ± 0.75 a | ||||||||

| Levantinka × 40 | 0.10 ± 0.01 b | 0.11 ± 0.02 | 4.16 ± 0.35 ab | 0.12 ± 0.03 d | 0.32 ± 0.08 | nd | 38.51 ± 1.51 ab | ||||||||

| Oblica × Control | nd b | nd | 4.92 ± 0.28 ab | nd d | nd | nd | 29.73 ± 4.61 b-f | ||||||||

| Oblica × 15 | nd b | nd | 4.56 ± 0.13 ab | nd d | nd | nd | 35.01 ± 0.95 a-d | ||||||||

| Oblica × 20 | nd b | nd | 4.50 ± 0.17 ab | nd d | nd | nd | 30.21 ± 1.78 b-f | ||||||||

| Oblica × 25 | 0.34 ± 0.42 b | 0.43 ± 0.52 | 3.44 ± 0.86 ab | nd d | nd | nd | 29.36 ± 1.74 b-f | ||||||||

| Oblica × 30 | nd b | 0.05 ± 0.03 | 4.83 ± 0.12 ab | nd d | nd | nd | 25.53 ± 0.87 efg | ||||||||

| Oblica × 35 | nd b | 0.05 ± 0.03 | 5.25 ± 0.20 a | nd d | nd | nd | 27.53 ± 0.31 d-g | ||||||||

| Oblica × 40 | nd b | 0.05 ± 0.03 | 4.86 ± 0.24 ab | nd d | nd | nd | 24.66 ± 0.81 efg | ||||||||

| Source of variation |

VOC from OX (mg/kg) |

VOC from MBA (mg/kg) |

|||||

| pentanal | 2,4-hexadienal | nonanal | Σ OX | 2-methylbutanal | 3-methylbutanal | Σ MBA | |

| A | A | B | C | B | |||

| Variety | p ≤ 0.05 | p ≤ 0.001 | p ≤ 0.01 | p ≤ 0.001 | p ≤ 0.001 | p ≤ 0.001 | p ≤ 0.001 |

| Istarska Bjelica | 0.75 ± 0.11 a | 0.59 ± 0.04 c | 0.16 ± 0.01 ab | 1.50 ± 0.11 c | 0.12 ± 0.00 a | 0.07 ± 0.01 a | 0.19 ± 0.01 a |

| Levantinka | 0.60 ± 0.12 ab | 2.39 ± 0.21 b | 0.18 ± 0.01 a | 3.16 ± 0.14 b | 0.04 ± 0.01 b | 0.03 ± 0.01 b | 0.08 ± 0.01 b |

| Oblica | 0.41 ± 0.06 b | 4.23 ± 0.16 a | 0.15 ± 0.01 b | 4.79 ± 0.14 a | 0.04 ± 0.01 b | 0.03 ± 0.00 b | 0.07 ± 0.01 b |

| Temperature (°C) | p ≤ 0.01 | p ≤ 0.01 | p ≤ 0.01 | p ≤ 0.01 | p ≤ 0.001 | p ≤ 0.001 | p ≤ 0.001 |

| Control | 0.48 ± 0.09 b | 2.98 ± 0.24 a | 0.15 ± 0.01 ab | 3.60 ± 0.26 a | 0.06 ± 0.01 b | 0.04 ± 0.01 b | 0.09 ± 0.01 b |

| 15 | 0.29 ± 0.02 b | 2.84 ± 0.14 ab | 0.15 ± 0.01 ab | 3.28 ± 0.14 a | 0.04 ± 0.01 b | 0.02 ± 0.01 b | 0.06 ± 0.02 b |

| 20 | 0.58 ± 0.19 ab | 2.43 ± 0.30 abc | 0.18 ± 0.01 a | 3.19 ± 0.16 a | 0.06 ± 0.01 b | 0.04 ± 0.01 b | 0.10 ± 0.02 b |

| 25 | 1.08 ± 0.32 a | 2.33 ± 0.30 abc | 0.13 ± 0.01 b | 3.54 ± 0.31 a | 0.14 ± 0.01 a | 0.09 ± 0.01 a | 0.23 ± 0.02 a |

| 30 | 0.47 ± 0.03 b | 2.27 ± 0.12 abc | 0.18 ± 0.01 a | 2.92 ± 0.13 a | 0.05 ± 0.01 b | 0.04 ± 0.01 b | 0.09 ± 0.01 b |

| 35 | 0.78 ± 0.14 ab | 1.85 ± 0.31 c | 0.17 ± 0.01 ab | 2.80 ± 0.20 a | 0.05 ± 0.01 b | 0.03 ± 0.01 b | 0.08 ± 0.01 b |

| 40 | 0.45 ± 0.05 b | 2.11 ± 0.11 bc | 0.18 ± 0.01 a | 2.73 ± 0.11 a | 0.06 ± 0.01 b | 0.04 ± 0.01 b | 0.10 ± 0.01 b |

| Variety × temperature (°C) | p = 0.070 | p ≤ 0.01 | p ≤ 0.05 | p ≤ 0.001 | p ≤ 0.001 | p ≤ 0.001 | p ≤ 0.001 |

| Istarska Bjelica × Control | 0.69 ± 0.17 | 0.75 ± 0.04 fghi | 0.15 ± 0.01 abc | 1.58 ± 0.14 fghi | 0.08 ± 0.01 bcdef | 0.04 ± 0.03 bcd | 0.12 ± 0.03 bcde |

| Istarska Bjelica × 15 | 0.36 ± 0.01 | 0.65 ± 0.03 ghi | 0.13 ± 0.01 abc | 1.14 ± 0.03 i | 0.05 ± 0.00 defghi | 0.01 ± 0.01 cd | 0.06 ± 0.01 ef |

| Istarska Bjelica × 20 | 0.54 ± 0.03 | 0.49 ± 0.14 i | 0.17 ± 0.03 abc | 1.20 ± 0.19 hi | 0.08 ± 0.01 bcdef | 0.04 ± 0.01 bcd | 0.12 ± 0.02 bcde |

| Istarska Bjelica × 25 | 1.92 ± 0.73 | 0.64 ± 0.09 ghi | 0.11 ± 0.01 c | 2.67 ± 0.64 efgh | 0.28 ± 0.01 a | 0.16 ± 0.01 a | 0.44 ± 0.01 a |

| Istarska Bjelica × 30 | 0.58 ± 0.07 | 0.55 ± 0.07 hi | 0.20 ± 0.03 ab | 1.34 ± 0.16 ghi | 0.11 ± 0.01 bcd | 0.07 ± 0.00 b | 0.18 ± 0.01 bcd |

| Istarska Bjelica × 35 | 0.70 ± 0.06 | 0.51 ± 0.15 i | 0.16 ± 0.01 abc | 1.37 ± 0.20 ghi | 0.11 ± 0.01 bcde | 0.07 ± 0.01 b | 0.17 ± 0.02 bcd |

| Istarska Bjelica × 40 | 0.49 ± 0.16 | 0.55 ± 0.10 hi | 0.19 ± 0.02 abc | 1.23 ± 0.15 hi | 0.13 ± 0.01 b | 0.08 ± 0.01 b | 0.21 ± 0.02 b |

| Levantinka × Control | 0.50 ± 0.21 | 2.84 ± 0.29 cde | 0.15 ± 0.01 abc | 3.49 ± 0.46 cde | 0.06 ± 0.00 cdefgh | 0.06 ± 0.01 b | 0.12 ± 0.01 bcde |

| Levantinka × 15 | 0.34 ± 0.04 | 2.41 ± 0.30 def | 0.19 ± 0.01 abc | 2.94 ± 0.33 def | 0.01 ± 0.01 hi | nd d | 0.01 ± 0.01 f |

| Levantinka × 20 | 0.79 ± 0.55 | 2.27 ± 0.86 defgh | 0.19 ± 0.01 abc | 3.25 ± 0.31 cde | 0.02 ± 0.02 ghi | 0.03 ± 0.02 bcd | 0.05 ± 0.03 ef |

| Levantinka × 25 | 0.70 ± 0.47 | 2.38 ± 0.60 defg | 0.13 ± 0.01 abc | 3.21 ± 0.41 de | 0.04 ± 0.03 fghi | 0.03 ± 0.02 bcd | 0.07 ± 0.04 def |

| Levantinka × 30 | 0.35 ± 0.05 | 2.62 ± 0.14 de | 0.18 ± 0.01 abc | 3.15 ± 0.10 de | 0.06 ± 0.02 defghi | 0.04 ± 0.02 bcd | 0.09 ± 0.04 cdef |

| Levantinka × 35 | 1.13 ± 0.42 | 1.45 ± 0.87 efghi | 0.20 ± 0.02 ab | 2.78 ± 0.51 defg | 0.05 ± 0.02 efghi | 0.03 ± 0.02 bcd | 0.08 ± 0.04 def |

| Levantinka × 40 | 0.39 ± 0.02 | 2.74 ± 0.25 de | 0.22 ± 0.03 a | 3.34 ± 0.25 cde | 0.06 ± 0.01 defgh | 0.05 ± 0.01 bc | 0.11 ± 0.03 bcdef |

| Oblica × Control | 0.24 ± 0.08 | 5.34 ± 0.65 ab | 0.15 ± 0.04 abc | 5.73 ± 0.60 a | 0.03 ± 0.02 fghi | 0.01 ± 0.01 cd | 0.04 ± 0.02 ef |

| Oblica × 15 | 0.17 ± 0.03 | 5.47 ± 0.28 a | 0.13 ± 0.04 abc | 5.76 ± 0.28 a | 0.07 ± 0.02 bcdefg | 0.04 ± 0.02 bcd | 0.11 ± 0.05 bcdef |

| Oblica × 20 | 0.4 ± 0.09 | 4.53 ± 0.22 abc | 0.19 ± 0.01 abc | 5.12 ± 0.31 ab | 0.07 ± 0.00 bcdefg | 0.05 ± 0.02 bcd | 0.12 ± 0.02 bcde |

| Oblica × 25 | 0.62 ± 0.43 | 3.96 ± 0.65 abcd | 0.15 ± 0.02 abc | 4.73 ± 0.53 abc | 0.12 ± 0.01 bc | 0.08 ± 0.01 b | 0.20 ± 0.02 bc |

| Oblica × 30 | 0.48 ± 0.00 | 3.65 ± 0.34 bcd | 0.15 ± 0.02 abc | 4.27 ± 0.35 abcd | nd i | nd d | nd f |

| Oblica × 35 | 0.50 ± 0.03 | 3.61 ± 0.26 bcd | 0.15 ± 0.00 abc | 4.26 ± 0.26 abcd | nd i | nd d | nd f |

| Oblica × 40 | 0.47 ± 0.03 | 3.04 ± 0.18 cde | 0.12 ± 0.00 bc | 3.63 ± 0.17 bcde | nd i | nd d | nd f |

| Source of variation | Phenolic compound (mg/kg) |

||||||||

| Hydroxytyrosol | Tyrosol | Oleacein | Oleocantal | Methyl hemiacetal of oleocanthal | Σ of oleorupein aglycons | Σ of ligstroside aglycons | p - Coumaric acid | Total phenolic content | |

| Variety | p ≤ 0.001 | p ≤ 0.001 | p ≤ 0.001 | p ≤ 0.001 | p ≤ 0.001 | p ≤ 0.001 | p ≤ 0.001 | p ≤ 0.001 | p ≤ 0.001 |

| Istarska Bjelica | 39 ± 1 a | 18 ± 1 a | 71 ± 3 b | 108 ± 2 a | 25 ± 1 a | 351 ± 6 a | 164 ± 2 a | 9 ± 0 b | 785 ± 8 a |

| Levantinka | 18 ± 3 b | 9 ± 2 b | 69 ± 6 b | 81 ± 3 b | 17 ± 2 b | 68 ± 3 c | 57 ± 2 c | 5 ± 0 c | 322 ± 8 c |

| Oblica | 17 ± 1 b | 9 ± 0 b | 88 ± 3 a | 83 ± 2 b | 18 ± 1 b | 117 ± 7 b | 80 ± 3 b | 10 ± 0 a | 422 ± 8 b |

| Temperature (°C) | p = 0.548 | p = 0.542 | p ≤ 0.001 | p ≤ 0.001 | p = 0.349 | p = 0.442 | p ≤ 0.001 | p ≤ 0.01 | p ≤ 0.05 |

| Control | 25 ± 1 | 11 ± 0 | 72 ± 4 bc | 84 ± 2 c | 22 ± 1 | 179 ± 11 | 110 ± 5 ab | 8 ± 0 ab | 510 ± 13 ab |

| 15 | 25 ± 1 | 11 ± 1 | 62 ± 4 c | 83 ± 2 c | 18 ± 2 | 184 ± 6 | 106 ± 3 abc | 8 ± 0 a | 498 ± 13 ab |

| 20 | 28 ± 4 | 14 ± 2 | 60 ± 6 c | 82 ± 3 c | 22 ± 2 | 186 ± 5 | 113 ± 2 a | 8 ± 0 ab | 513 ± 13 ab |

| 25 | 25 ± 3 | 13 ± 3 | 65 ± 9 bc | 85 ± 5 bc | 21 ± 3 | 169 ± 7 | 91 ± 4 cd | 8 ± 0 ab | 477 ± 13 b |

| 30 | 20 ± 1 | 10 ± 0 | 91 ± 5 ab | 98 ± 3 b | 19 ± 1 | 172 ± 7 | 96 ± 3 bcd | 7 ± 0 b | 513 ± 13 ab |

| 35 | 26 ± 6 | 13 ± 3 | 77 ± 10 abc | 93 ± 5 bc | 21 ± 4 | 172 ± 6 | 98 ± 2 bcd | 8 ± 0 b | 507 ± 13 ab |

| 40 | 26 ± 3 | 12 ± 1 | 104 ± 4 a | 111 ± 3 a | 17 ± 1 | 186 ± 15 | 87 ± 5 d | 8 ± 0 ab | 552 ± 13 a |

| Variety × Temperature (°C) | p = 0.425 | p = 0.587 | p ≤ 0.001 | p ≤ 0.001 | p = 0.255 | p = 0.135 | p ≤ 0.001 | p ≤ 0.001 | p = 0.543 |

| Istarska Bjelica × Control | 36 ± 3 | 16 ± 1 | 77 ± 9 bcd | 106 ± 5 abcde | 32 ± 3 | 330 ± 30 | 169 ± 11 a | 7 ± 0 d | 773 ± 22 |

| Istarska Bjelica × 15 | 39 ± 1 | 18 ± 1 | 70 ± 3 bcd | 107 ± 2 abcde | 24 ± 1 | 368 ± 12 | 163 ± 2 a | 8 ± 0 cd | 798 ± 22 |

| Istarska Bjelica × 20 | 41 ± 2 | 20 ± 1 | 57 ± 1 d | 102 ± 2 bcdef | 21 ± 0 | 360 ± 11 | 168 ± 5 a | 9 ± 1 cd | 778 ± 22 |

| Istarska Bjelica × 25 | 42 ± 4 | 21 ± 5 | 67 ± 17 bcd | 112 ± 8 ab | 29 ± 5 | 327 ± 14 | 156 ± 1 a | 10 ± 0 bc | 765 ± 22 |

| Istarska Bjelica × 30 | 38 ± 1 | 18 ± 1 | 79 ± 10 bcd | 111 ± 5 abc | 23 ± 2 | 344 ± 18 | 157 ± 5 a | 8 ± 0 cd | 775 ± 22 |

| Istarska Bjelica × 35 | 40 ± 2 | 19 ± 1 | 71 ± 3 bcd | 108 ± 1 abcd | 24 ± 0 | 360 ± 16 | 167 ± 4 a | 9 ± 1 cd | 798 ± 22 |

| Istarska Bjelica × 40 | 40 ± 1 | 18 ± 1 | 76 ± 1 bcd | 111 ± 1 ab | 24 ± 0 | 366 ± 6 | 165 ± 2 a | 9 ± 0 cd | 809 ± 22 |

| Levantinka × Control | 15 ± 1 | 5 ± 0 | 83 ± 5 bcd | 83 ± 3 defghi | 15 ± 1 | 69 ± 4 | 54 ± 3 def | 5 ± 0 e | 328 ± 22 |

| Levantinka × 15 | 16 ± 1 | 9 ± 3 | 60 ± 7 cd | 79 ± 2 fghi | 11 ± 7 | 62 ± 8 | 57 ± 8 def | 5 ± 0 e | 299 ± 22 |

| Levantinka × 20 | 24 ± 10 | 12 ± 7 | 60 ± 19 cd | 82 ± 9 efghi | 23 ± 6 | 83 ± 8 | 69 ± 2 d | 5 ± 1 e | 356 ± 22 |

| Levantinka × 25 | 16 ± 9 | 10 ± 7 | 63 ± 19 cd | 72 ± 12 ghi | 17 ± 8 | 52 ± 4 | 38 ± 9 ef | 4 ± 0 e | 273 ± 22 |

| Levantinka × 30 | 14 ± 1 | 5 ± 0 | 81 ± 3 bcd | 85 ± 1 cdefghi | 15 ± 1 | 70 ± 9 | 58 ± 2 def | 4 ± 0 e | 333 ± 22 |

| Levantinka × 35 | 27 ± 18 | 14 ± 10 | 54 ± 26 d | 74 ± 12 ghi | 22 ± 11 | 67 ± 7 | 57 ± 3 def | 4 ± 0 e | 318 ± 22 |

| Levantinka × 40 | 17 ± 1 | 7 ± 1 | 82 ± 7 bcd | 91 ± 1 bcdefgh | 13 ± 2 | 73 ± 5 | 63 ± 6 de | 5 ± 0 e | 351 ± 22 |

| Oblica × Control | 23 ± 1 | 12 ± 1 | 56 ± 9 d | 61 ± 4 i | 21 ± 3 | 138 ± 15 | 106 ± 7 b | 12 ± 0 a | 429 ± 22 |

| Oblica × 15 | 19 ± 1 | 8 ± 1 | 57 ± 8 d | 63 ± 4 i | 20 ± 1 | 123 ± 7 | 96 ± 2 bc | 12 ± 0 ab | 397 ± 22 |

| Oblica × 20 | 21 ± 1 | 9 ± 0 | 62 ± 2 cd | 62 ± 2 i | 22 ± 1 | 115 ± 3 | 103 ± 1 b | 10 ± 1 c | 405 ± 22 |

| Oblica × 25 | 17 ± 1 | 8 ± 1 | 65 ± 2 cd | 70 ± 0 hi | 17 ± 2 | 129 ± 13 | 80 ± 5 bcd | 10 ± 1 bc | 395 ± 22 |

| Oblica × 30 | 10 ± 3 | 6 ± 0 | 114 ± 10 ab | 97 ± 7 bcdefg | 18 ± 1 | 103 ± 3 | 74 ± 7 cd | 9 ± 0 cd | 430 ± 22 |

| Oblica × 35 | 10 ± 4 | 7 ± 0 | 106 ± 13 abc | 96 ± 9 bcdefgh | 16 ± 1 | 90 ± 5 | 71 ± 4 cd | 10 ± 0 bc | 405 ± 22 |

| Oblica × 40 | 21 ± 8 | 10 ± 2 | 154 ± 10 a | 132 ± 8 a | 14 ± 4 | 119 ± 45 | 33 ± 14 f | 9 ± 1 cd | 496 ± 22 |

| Source of variation | Tocopherols (mg/kg) |

|

| α-tocopherol | γ-tocopherol | |

| Variety* | p ≤ 0.001 | p ≤ 0.001 |

| Istarska Bjelica | 79 ± 1 c | nd c |

| Levantinka | 249 ± 2 a | 11 ± 0 a |

| Oblica | 222 ± 4 b | 8 ± 0 b |

| Temperature (°C) ** | p ≤ 0.001 | p ≤ 0.001 |

| Control | 198 ± 2 a | 7 ± 0 a |

| 15 | 201 ± 2 a | 7 ± 0 ab |

| 20 | 176 ± 9 bcd | 6 ± 0 bc |

| 25 | 188 ± 2 ab | 6 ± 0 b |

| 30 | 182 ± 2 bc | 6 ± 0 bc |

| 35 | 173 ± 2 cd | 6 ± 0 c |

| 40 | 167 ± 2 d | 6 ± 0 c |

| Variety × Temperature (°C) | p ≤ 0.001 | p ≤ 0.001 |

| Istarska Bjelica × Control | 75 ± 3 h | nd f |

| Istarska Bjelica × 15 | 73 ± 4 h | nd f |

| Istarska Bjelica × 20 | 83 ± 0 h | nd f |

| Istarska Bjelica × 25 | 78 ± 2 h | nd f |

| Istarska Bjelica × 30 | 76 ± 4 h | nd f |

| Istarska Bjelica × 35 | 85 ± 3 h | nd f |

| Istarska Bjelica × 40 | 82 ± 2 h | nd f |

| Levantinka × Control | 273 ± 5 ab | 12 ± 1 a |

| Levantinka × 15 | 237 ± 2 cdef | 11 ± 1 a |

| Levantinka × 20 | 232 ± 9 def | 11 ± 0 a |

| Levantinka × 25 | 264 ± 6 abc | 11 ± 0 ab |

| Levantinka × 30 | 258 ± 6 bcd | 11 ± 0 a |

| Levantinka × 35 | 248 ± 5 bcde | 11 ± 0 a |

| Levantinka × 40 | 232 ± 4 def | 11 ± 0 a |

| Oblica × Control | 244 ± 5 bcde | 11 ± 0 a |

| Oblica × 15 | 292 ± 2 a | 9 ± 0 bc |

| Oblica × 20 | 213 ± 25 fg | 7 ± 1 de |

| Oblica × 25 | 221 ± 2 ef | 8 ± 0 cd |

| Oblica × 30 | 211 ± 0 fg | 7 ± 0 de |

| Oblica × 35 | 185 ± 1 g | 6 ± 0 e |

| Oblica × 40 | 187 ± 1 g | 6 ± 0 e |

| Source of variation | Fatty acid (% of total) |

|||||||||

| C16:0 | C16:1 | C18:0 | C18:1 | C18:2 | C18:3 | C20:0 | Σ SFA | Σ MUFA | Σ PUFA | |

| Variety* | p ≤ 0.001 | p ≤ 0.001 | p ≤ 0.001 | p ≤ 0.001 | p ≤ 0.001 | *** | p ≤ 0.001 | p ≤ 0.001 | p ≤ 0.001 | p ≤ 0.001 |

| Istarska Bjelica | 13.0 ± 0.0 b | 1.2 ± 0.0 a | 3.4 ± 0.0 a | 73.2 ± 0.1 b | 6.0 ± 0.0 b | 0.4 ± 0.0 | 0.5 ± 0.0 ab | 16.9 ± 0.0 a | 74.5 ± 0.1 b | 6.4 ± 0.0 b |

| Levantinka | 11.6 ± 0.0 c | 0.6 ± 0.0 c | 3.0 ± 0.0 b | 76.3 ± 0.1 a | 5.5 ± 0.0 c | 0.6 ± 0.0 | 0.5 ± 0.0 a | 15.1 ± 0.0 c | 77.2 ± 0.1 a | 6.1 ± 0.0 c |

| Oblica | 13.4 ± 0.0 a | 0.7 ± 0.0 b | 2.4 ± 0.1 c | 69.2 ± 0.1 c | 11.4 ± 0.0 a | 0.6 ± 0.0 | 0.5 ± 0.0 b | 16.3 ± 0.1 b | 70.2 ± 0.1 c | 12.1 ± 0.1 a |

| Temperature (°C)** | p ≤ 0.001 | p ≤ 0.001 | p = 0.414 | p ≤ 0.001 | p = 0.067 | *** | p ≤ 0.001 | p = 0.006 | p ≤ 0.001 | p = 0.052 |

| Control | 12.7 ± 0.1 ab | 0.8 ± 0.0 c | 2.9 ± 0.0 | 72.8 ± 0.1 ab | 7.5 ± 0.0 | 0.5 ± 0.0 | 0.5 ± 0.0 ab | 16.1 ± 0.0 ab | 73.8 ± 0.1 bc | 8.1 ± 0.0 |

| 15 | 12.8 ± 0.0 a | 0.8 ± 0.0 b | 2.9 ± 0.0 | 72.8 ± 0.1 ab | 7.6 ± 0.0 | 0.6 ± 0.0 | 0.5 ± 0.0 a | 16.2 ± 0.02 a | 74.0 ± 0.1 bc | 8.2 ± 0.0 |

| 20 | 12.7 ± 0.0 ab | 0.8 ± 0.0 a | 3.0 ± 0.0 | 72.9 ± 0.1 ab | 7.6 ± 0.1 | 0.6 ± 0.0 | 0.5 ± 0.0 a | 16.2 ± 0.0 a | 74.0 ± 0.1 abc | 8.2 ± 0.1 |

| 25 | 12.8 ± 0.0 a | 0.9 ± 0.0 a | 3.0 ± 0.0 | 72.6 ± 0.1 b | 7.6 ± 0.0 | 0.6 ± 0.0 | 0.5 ± 0.0 a | 16.3 ± 0.0 a | 73.7 ± 0.1 c | 8.2 ± 0.0 |

| 30 | 12.5 ± 0.0 b | 0.8 ± 0.0 b | 2.7 ± 0.3 | 73.2 ± 0.1 a | 7.6 ± 0.0 | 0.5 ± 0.0 | 0.5 ± 0.0 a | 15.8 ± 0.3 b | 74.3 ± 0.1 a | 8.1 ± 0.1 |

| 35 | 12.6 ± 0.1 b | 0.8 ± 0.0 bc | 2.9 ± 0.0 | 73.0 ± 0.1 a | 7.7 ± 0.0 | 0.5 ± 0.0 | 0.5 ± 0.0 ab | 16.0 ± 0.0 ab | 74.1 ± 0.1 ab | 8.2 ± 0.0 |

| 40 | 12.6 ± 0.0 b | 0.8 ± 0.0 b | 2.9 ± 0.0 | 72.9 ± 0.1 ab | 7.7 ± 0.0 | 0.5 ± 0.0 | 0.5 ± 0.0 b | 16.0 ± 0.0 ab | 74.0 ± 0.1abc | 8.3 ± 0.0 |

| Variety × Temperature (°C) | p ≤ 0.001 | p ≤ 0.001 | p = 0.254 | p ≤ 0.001 | p = 0.035 | *** | p ≤ 0.001 | p ≤ 0.001 | p ≤ 0.001 | p = 0.099 |

| Istarska Bjelica × Control | 13.1 ± 0.1 de | 1.2 ± 0.0 ab | 3.3 ± 0.0 | 72.4 ± 0.4 d | 5.9 ± 0.0 bc | 0.4 ± 0.0 | 0.4 ± 0.0 b | 16.8 ± 0.1 ab | 73.8 ± 0.4 d | 6.3 ± 0.0 |

| Istarska Bjelica × 15 | 12.9 ± 0.0 e | 1.1 ± 0.0 b | 3.4 ± 0.0 | 73.7 ± 0.0 b | 6.0 ± 0.0 b | 0.4 ± 0.0 | 0.5 ± 0.0 a | 16.8 ± 0.0 abc | 75.0 ± 0.0 b | 6.4 ± 0.0 |

| Istarska Bjelica × 20 | 13.1 ± 0.1 de | 1.2 ± 0.0 a | 3.4 ± 0.0 | 73.1 ± 0.2bcd | 5.9 ± 0.0 bc | 0.4 ± 0.0 | 0.5 ± 0.0 a | 17.0 ± 0.1 a | 74.5 ± 0.2 bc | 6.3 ± 0.0 |

| Istarska Bjelica × 25 | 13.1 ± 0.0 de | 1.2 ± 0.0 a | 3.4 ± 0.0 | 72.8 ± 0.2 cd | 6.0 ± 0.0 b | 0.4 ± 0.0 | 0.5 ± 0.0 a | 17.0 ± 0.0 a | 74.2 ± 0.2 cd | 6.4 ± 0.0 |

| Istarska Bjelica × 30 | 13.0 ± 0.0 e | 1.2 ± 0.0 a | 3.4 ± 0.0 | 73.5 ± 0.1 bc | 6.0 ± 0.0 b | 0.4 ± 0.0 | 0.5 ± 0.0 a | 16.9 ± 0.0 a | 74.9 ± 0.1 bc | 6.4 ± 0.0 |

| Istarska Bjelica × 35 | 13.1 ± 0.0 de | 1.2 ± 0.0 a | 3.4 ± 0.0 | 73.4 ± 0.1 bc | 6.0 ± 0.1 b | 0.4 ± 0.0 | 0.5 ± 0.0 a | 17.0 ± 0.0 a | 74.8 ± 0.1 bc | 6.4 ± 0.1 |

| Istarska Bjelica × 40 | 13.1 ± 0.0 de | 1.2 ± 0.0 a | 3.4 ± 0.0 | 73.2 ± 0.1 bc | 6.0 ± 0.0 bc | 0.4 ± 0.0 | 0.5 ± 0.0 a | 17.0 ± 0.0 a | 74.6 ± 0.1 bc | 6.4 ± 0.0 |

| Levantinka × Control | 11.4 ± 0.0 g | 0.5 ± 0.0 f | 3.0 ± 0.0 | 76.7 ± 0.0 a | 5.3 ± 0.0 d | 0.6 ± 0.0 | 0.5 ± 0.0 a | 14.9 ± 0.0 e | 77.5 ± 0.0 a | 5.9 ± 0.0 |

| Levantinka × 15 | 11.6 ± 0.0 fg | 0.6 ± 0.0 e | 3.0 ± 0.0 | 76.2 ± 0.2 a | 5.5 ± 0.1 d | 0.6 ± 0.0 | 0.5 ± 0.0 a | 15.0 ± 0.0 e | 77.1 ± 0.2 a | 6.1 ± 0.1 |

| Levantinka × 20 | 11.7 ± 0.1 f | 0.6 ± 0.0 d | 3.0 ± 0.0 | 76.0 ± 0.2 a | 5.6 ± 0.0 bcd | 0.6 ± 0.0 | 0.5 ± 0.0 a | 15.2 ± 0.0 de | 76.9 ± 0.2 a | 6.2 ± 0.0 |

| Levantinka × 25 | 11.5 ± 0.0 fg | 0.6 ± 0.0 e | 3.0 ± 0.0 | 76.3 ± 0.1 a | 5.4 ± 0.1 d | 0.6 ± 0.0 | 0.5 ± 0.0 a | 15.0 ± 0.0 e | 77.2 ± 0.1 a | 6.0 ± 0.1 |

| Levantinka × 30 | 11.6 ± 0.0 fg | 0.6 ± 0.0 ef | 3.0 ± 0.0 | 76.5 ± 0.3 a | 5.3 ± 0.1 d | 0.6 ± 0.0 | 0.5 ± 0.0 a | 15.1 ± 0.0 de | 77.3 ± 0.3 a | 5.9 ± 0.1 |

| Levantinka × 35 | 11.6 ± 0.1 fg | 0.5 ± 0.0 ef | 3.0 ± 0.0 | 76.5 ± 0.3 a | 5.5 ± 0.1 d | 0.6 ± 0.0 | 0.5 ± 0.0 a | 15.0 ± 0.1 e | 77.3 ± 0.3 a | 6.1 ± 0.1 |

| Levantinka × 40 | 11.7 ± 0.0 f | 0.6 ± 0.0 d | 3.0 ± 0.0 | 76.2 ± 0.1 a | 5.6 ± 0.1 cd | 0.6 ± 0.0 | 0.5 ± 0.0 a | 15.2 ± 0.0 de | 77.1 ± 0.1 a | 6.2 ± 0.1 |

| Oblica × Control | 13.5 ± 0.0 bc | 0.7 ± 0.0 d | 2.5 ± 0.0 | 69.2 ± 0.2 efg | 11.4 ± 0.1 a | 0.6 ± 0.0 | 0.5 ± 0.0 a | 16.5 ± 0.0 abc | 70.2 ± 0.2 ef | 12.0 ± 0.1 |

| Oblica × 15 | 13.9 ± 0.0 a | 0.8 ± 0.0 c | 2.4 ± 0.0 | 68.7 ± 0.2 g | 11.4 ± 0.1 a | 0.7 ± 0.0 | 0.5 ± 0.0 a | 16.8 ± 0.0 ab | 69.8 ± 0.2 f | 12.1 ± 0.1 |

| Oblica × 20 | 13.3 ± 0.1 cd | 0.7 ± 0.0 d | 2.7 ± 0.0 | 69.5 ± 0.3 ef | 11.3 ± 0.3 a | 0.7 ± 0.0 | 0.5 ± 0.0 a | 16.5 ± 0.4 abc | 70.5 ± 0.3 ef | 12.0 ± 0.3 |

| Oblica × 25 | 13.8 ± 0.0 ab | 0.8 ± 0.0 c | 2.5 ± 0.0 | 68.8 ± 0.0 fg | 11.5 ± 0.0 a | 0.7 ± 0.0 | 0.5 ± 0.0 a | 16.8 ± 0.0 ab | 69.87 ± 0.04 f | 12.2 ± 0.0 |

| Oblica × 30 | 13.1 ± 0.1 de | 0.7 ± 0.0 d | 1.7 ± 0.9 | 69.7 ± 0.1 e | 11.5 ± 0.1 a | 0.6 ± 0.0 | 0.5 ± 0.0 a | 15.3 ± 0.9 de | 70.7 ± 0.1 e | 12.1 ± 0.1 |

| Oblica × 35 | 13.1 ± 0.0 de | 0.7 ± 0.0 d | 2.4 ± 0.0 | 69.3 ± 0.0 efg | 11.5 ± 0.0 a | 0.6 ± 0.0 | 0.4 ± 0.0 b | 15.9 ± 0.0 bcd | 70.3 ± 0.0 ef | 12.1 ± 0.0 |

| Oblica × 40 | 13.1 ± 0.0 de | 0.7 ± 0.0 d | 2.4 ± 0.0 | 69.1 ± 0.1 efg | 11.6 ± 0.1 a | 0.6 ± 0.0 | 0.4 ± 0.0 b | 15.9 ± 0.0 cde | 70.1 ± 0.1 ef | 12.2 ± 0.1 |

| Source of variation | IP (min) |

AC (% DPPH red.) *** |

| Variety* | p ≤ 0.001 | p ≤ 0.001 |

| Istarska Bjelica | 202 ± 2 a | 60.06 ± 0.38 a |

| Levantinka | 157 ± 3 b | 49.86 ± 0.29 c |

| Oblica | 104 ± 1 c | 56.29 ± 0.38 b |

| Temperature (°C)** | p ≤ 0.05 | p ≤ 0.001 |

| Control | 160 ± 4 a | 58.65 ± 0.55 a |

| 15 | 158 ± 2 a | 55.5 ± 0.42 b |

| 20 | 157 ± 3 ab | 58.85 ± 0.81 a |

| 25 | 152 ± 4 ab | 53.37 ± 0.56 bc |

| 30 | 160 ± 6 a | 55.31 ± 0.53 b |

| 35 | 144 ± 2 b | 53.09 ± 0.48 c |

| 40 | 155 ± 2 ab | 53.04 ± 0.33 c |

| Variety × Temperature (°C) | p ≤ 0.001 | p ≤ 0.001 |

| Istarska Bjelica × Control | 189 ± 6 bcd | 60.07 ± 0.18 bc |

| Istarska Bjelica × 15 | 206 ± 5 ab | 58.77 ± 0.54 cd |

| Istarska Bjelica × 20 | 197 ± 4 abc | 61.58 ± 2.1 abc |

| Istarska Bjelica × 25 | 200 ± 6 ab | 59.87 ± 0.72 bc |

| Istarska Bjelica × 30 | 210 ± 4 ab | 60.73 ± 1.09 bc |

| Istarska Bjelica × 35 | 199 ± 5 ab | 59.88 ± 0.78 bc |

| Istarska Bjelica × 40 | 219 ± 3 a | 59.53 ± 0.41 bcd |

| Levantinka × Control | 168 ± 8 de | 50.18 ± 0.94 ghi |

| Levantinka × 15 | 149 ± 3 ef | 50.00 ± 0.32 ghi |

| Levantinka × 20 | 156 ± 7 e | 51.77 ± 0.85 fgh |

| Levantinka × 25 | 155 ± 6 e | 44.53 ± 0.27 j |

| Levantinka × 30 | 170 ± 19 cde | 51.12 ± 1.03 ghi |

| Levantinka × 35 | 145 ± 3 efg | 48.87 ± 1.08 hi |

| Levantinka × 40 | 157 ± 5 e | 52.53 ± 0.47 fgh |

| Oblica × Control | 122 ± 4 fgh | 65.70 ± 1.35 a |

| Oblica × 15 | 118 ± 4 ghi | 57.73 ± 1.1 cde |

| Oblica × 20 | 117 ± 1 hi | 63.20 ± 0.83 ab |

| Oblica × 25 | 103 ± 6 hij | 55.70 ± 1.5 def |

| Oblica × 30 | 94 ± 1 ij | 54.07 ± 0.5 efg |

| Oblica × 35 | 88 ± 0 j | 50.53 ± 0.57 ghi |

| Oblica × 40 | 88 ± 2 j | 47.07 ± 0.78 ij |

| Variety | Parameters for optimization | ||||||

| IP min |

AC (% DPPH red.) |

ΣLOX mg/kg |

ΣOX mg/kg |

ΣMBA mg/kg |

|||

| Model * | y = a + b × T + c × T2 + d × T3 | ||||||

| Istarska bjelica* |

a | 237.017 | 54.088 | 5.761 | -1.755 | -0.593 | |

| b | -3.128 | 0.484 | 1.549 | 0.264 | 0.059 | ||

| c | 0.065 | -0.009 | 0.029 | -0.004 | -0.001 | ||

| p-Value | Model | 0.035 | 0.362 | 0.210 | 0.146 | 0.040 | |

| Lack of fit | 0.056 | 0.338 | 0.001 | 0.007 | <0.0001 | ||

| R2 | 0.361 | 0.127 | 0.189 | 0.227 | 0.350 | ||

| Optimal temperature | 18.9 | ||||||

| Desirability | 0.481 | ||||||

| Predicted values | 201 | 60.80 | 24.56 | 1.51 | 0.07 | ||

| Levantinka* | a | 119.932 | 62.511 | 39.282 | 3.009 | -0.133 | |

| b | 2.705 | -1.096 | 0.249 | 0.004 | 0.012 | ||

| c | -0.047 | 0.021 | -0.005 | -2.98E-05 | -1.54E-04 | ||

| p-Value | Model | 0.641 | 0.107 | 0.787 | 0.976 | 0.027 | |

| Lack of fit | 0.209 | ≤ 0.0001 | 0.138 | 0.458 | 0.924 | ||

| R2 | 0.058 | 0.258 | 0.031 | 0.003 | 0.383 | ||

| Optimal temperature | 15.4 | ||||||

| Desirability | 0.518 | ||||||

| Predicted values | 150 | 50.61 | 41.75 | 3.07 | 0.01 | ||

| Oblica | a | 50.898 | 1.54 | 48.997 | 7.564 | -1.316 | |

| b | 10.48 | 7.245 | -1.191 | -0.141 | 0.179 | ||

| c | -0.489 | -0.276 | 0.015 | -0.001 | -0.007 | ||

| d | 0.006 | 0.003 | 0** | 0** | 7.99E-05 | ||

| p-Value | Model | ≤ 0.0001 | ≤ 0.0001 | ≤ 0.0001 | ≤ 0.0001 | 0.001 | |

| Lack of fit | 0.513 | 0.001 | 0.110 | 0.764 | 0.001 | ||

| R2 | 0.908 | 0.864 | 0.772 | 0.736 | 0.659 | ||

| Optimal temperature | 15.5 | ||||||

| Desirability | 0.639 | ||||||

| Predicted values | 119 | 58.96 | 34.15 | 5.65 | 0.01 | ||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).