The application of US in VOO production has received growing attention as a technology potentially capable of enhancing the release of intracellular components and improving oil functionality [

16]. In this study, the effects of US pretreatment in the production of VOO in laboratory conditions were evaluated across four Croatian olive varieties, focusing on both compositional changes and biochemical responses. All samples, regardless of treatment, met the official criteria for extra virgin olive oil under EU regulations [

38]. Peroxide values ranged from 1.0 to 3.0 meq O₂/kg, free fatty acids from 0.19 to 0.42% oleic acid, and UV absorption indices (K

232, K

268, ∆K) remained within acceptable limits. As in previous studies on both industrial and laboratory scale [

9,

10,

15,

16,

17], no significant differences were observed between control and US-treated samples for these basic quality parameters. Therefore, they are not further discussed in this paper, allowing greater emphasis on the more sensitive indicators of oil quality and technological response. Furthermore, given that olive variety strongly determines the chemical composition, phenolic content, and antioxidant capacity of VOO, and thus its specific response to US-assisted extraction [

39], it is essential to first discuss the intrinsic differences among the studied varieties.

3.2. Influence of Ultrasound

It was previously reported in several studies that US affected Y, OSI, AC, phenolic and tocopherol content [

9,

10,

12,

15,

16,

17,

73,

74,

75]. However, negligible effect of US on volatile compounds has been reported [

14,

15,

17,

76] or that it led to a slight decrease [

9,

16,

17], which was explained by the increase in temperature and the inactivation of enzymes of the LOX pathway by acoustic cavitation. In addition, Yahyaoui et al. [

18] reported no significant impact of US on LOX activity, while β-GLU showed a slight decrease in its activity. On the other hand, US significantly affected PPO and POX activities [

2,

3]. Mild or short US stimulated activity due to heat and micro-mixing effects, while higher power decreased enzyme activity or inhibited the enzyme. These results highlight the complexity of the effects of US technology on both the production yield and the quality of virgin olive oil.

To better understand the effects of US treatment on key quality and compositional parameters of VOO produced from Croatian olive varieties, RSM was employed. This statistical tool enables the evaluation of multiple variables and their interactions simultaneously, offering an efficient approach to model complex systems such as olive paste processing. In this study, a two-factor interaction (2FI) models were developed to describe the influence of US power (256 – 640 W) and treatment time (3 – 17 min). Results in

Table 6 present model parameters for Y, OSI, AC, phenolic and tocopherol content, and linoleic acid concentration. The models for other parameters investigated were also developed, but were not significant, which is why they are not presented and discussed further here.

Table 6.

Two-factor interaction model parameters (regression coefficients, p-value, coefficient of determination (R2) and lack of fit) for oil yield (Y), oxidative stability index (OSI), antioxidant capacity (AC), content of linoleic acid, total phenolic compounds and α-tocopherol content affected by US treatment duration (min), power (W) and olive variety.

Table 6.

Two-factor interaction model parameters (regression coefficients, p-value, coefficient of determination (R2) and lack of fit) for oil yield (Y), oxidative stability index (OSI), antioxidant capacity (AC), content of linoleic acid, total phenolic compounds and α-tocopherol content affected by US treatment duration (min), power (W) and olive variety.

| Model parameter |

Y (%) |

OSI (min) |

AC (% of DPPH˙ reduction) |

Linoleic acid (mg/g) |

TPC (mg/kg) |

α-tocopherol (mg/kg) |

| Intercept |

12.923 |

130.94 |

53.037 |

93.6 |

296.586 |

287.106 |

| p-value |

<0,0001 |

<0,0001 |

<0,0001 |

<0,0001 |

<0,0001 |

<0,0001 |

| Time |

0.159 |

-3.908 |

-2.012 |

-0.166 |

-12.653 |

-2.557 |

| p-value |

0.093 |

0.004 |

<0,0001 |

0.603 |

0.000 |

0.375 |

| Power |

0.105 |

-0.879 |

-0.453 |

-0.649 |

-3.305 |

-0.228 |

| p-value |

0.247 |

0.477 |

0.272 |

0.037 |

0.275 |

0.935 |

| Variety-Istarska Bjelica |

-2.167 |

24.252 |

8.156 |

-9.462 |

147.029 |

13.317 |

| p-value |

<0,0001 |

<0,0001 |

<0,0001 |

<0,0001 |

<0,0001 |

0.001 |

| Variety-Levantinka |

7.05 |

7.46 |

-3.413 |

-27.823 |

-41.035 |

35.01 |

| p-value |

<0,0001 |

<0,0001 |

<0,0001 |

<0,0001 |

<0,0001 |

<0,0001 |

| Variety-Oblica |

0.9 |

-92.602 |

-22.275 |

68.004 |

-179.161 |

-33.683 |

| p-value |

<0,0001 |

<0,0001 |

<0,0001 |

<0,0001 |

<0,0001 |

<0,0001 |

| Variety-Rosulja |

-5.783 |

60.89 |

17.533 |

-30.719 |

73.168 |

-14.644 |

| p-value |

<0,0001 |

<0,0001 |

<0,0001 |

<0,0001 |

<0,0001 |

0 |

| Time *Power |

-0.184 |

-1.325 |

0.4 |

1.066 |

-3.992 |

16.688 |

| p-value |

0.164 |

0.462 |

0.505 |

0.019 |

0.365 |

<0,0001 |

| Time *Variety-Istarska Bjelica |

0.217 |

-1.066 |

-0.403 |

0.053 |

12.657 |

-6.509 |

| p-value |

0.182 |

0.63 |

0.585 |

0.923 |

0.021 |

0.193 |

| Time *Variety-Levantinka |

0.064 |

-1.879 |

-1.322 |

0.191 |

-8.421 |

-5.966 |

| p-value |

0.691 |

0.398 |

0.076 |

0.729 |

0.122 |

0.233 |

| Time *Variety-Oblica |

-0.131 |

1.542 |

-0.204 |

-1.087 |

-0.853 |

1.509 |

| p-value |

0.419 |

0.487 |

0.783 |

0.051 |

0.875 |

0.762 |

| Time *Variety-Rosulja |

-0.151 |

1.403 |

1.929 |

0.842 |

-3.382 |

10.966 |

| p-value |

0.352 |

0.527 |

0.01 |

0.129 |

0.532 |

0.03 |

| Power *Variety-Istarska Bjelica |

-0.276 |

-7.309 |

-2.812 |

0.493 |

-15.387 |

0.169 |

| p-value |

0.082 |

0.001 |

0 |

0.356 |

0.004 |

0.972 |

| Power *Variety-Levantinka |

0.115 |

5.803 |

1.782 |

1.131 |

8.789 |

-11.743 |

| p-value |

0.461 |

0.009 |

0.014 |

0.036 |

0.095 |

0.016 |

| Power *Variety-Oblica |

0.363 |

3.574 |

2.376 |

-3.343 |

9.826 |

-1.184 |

| p-value |

0.024 |

0.1 |

0.001 |

<0,0001 |

0.062 |

0.806 |

| Power *Variety-Rosulja |

-0.202 |

-2.068 |

-1.347 |

1.719 |

-3.229 |

12.757 |

| p-value |

0.199 |

0.336 |

0.061 |

0.002 |

0.537 |

0.009 |

| R2 |

0.991 |

0.988 |

0.958 |

0.997 |

0.966 |

0.653 |

| R2 adjusted |

0.988 |

0.985 |

0.952 |

0.996 |

0.962 |

0.607 |

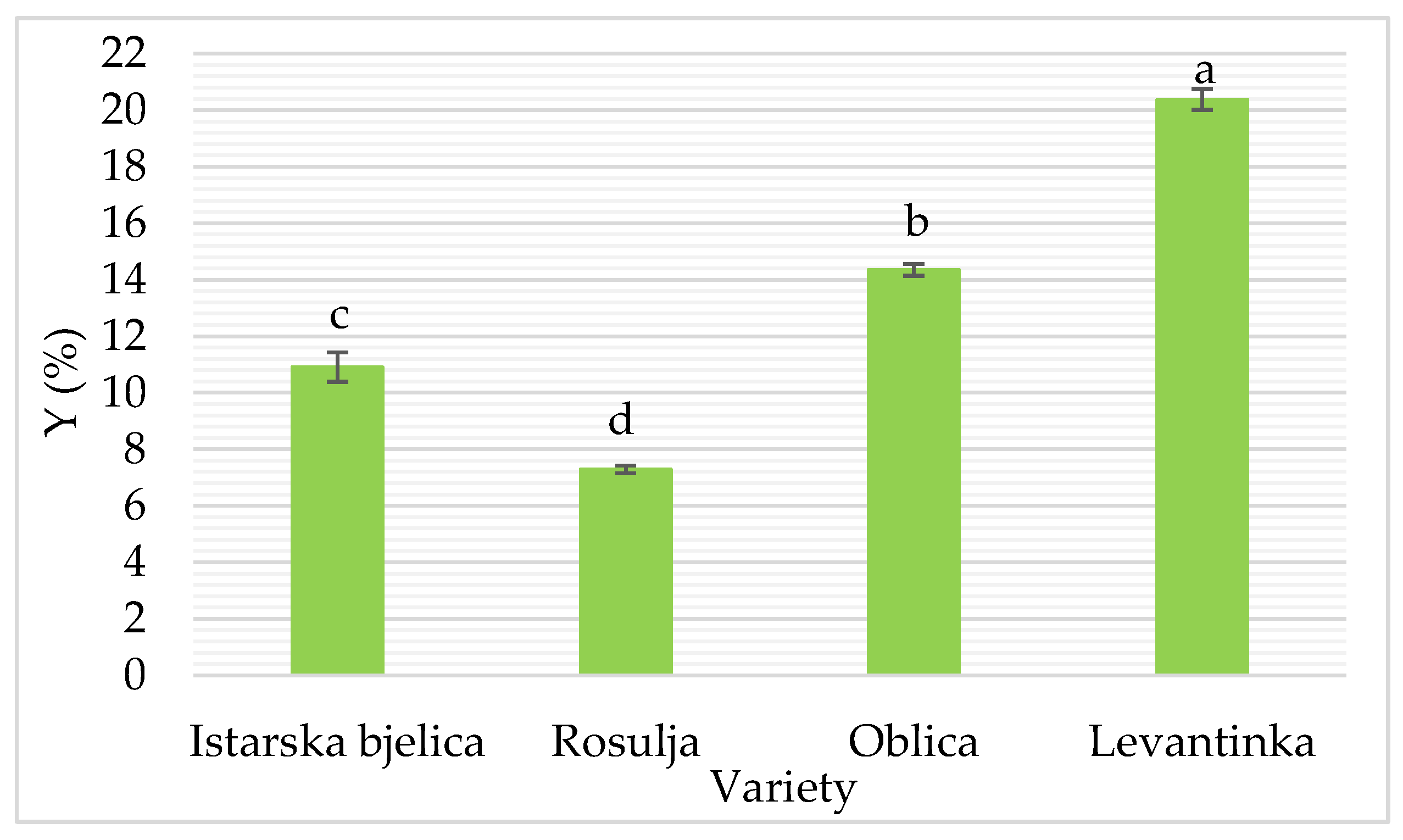

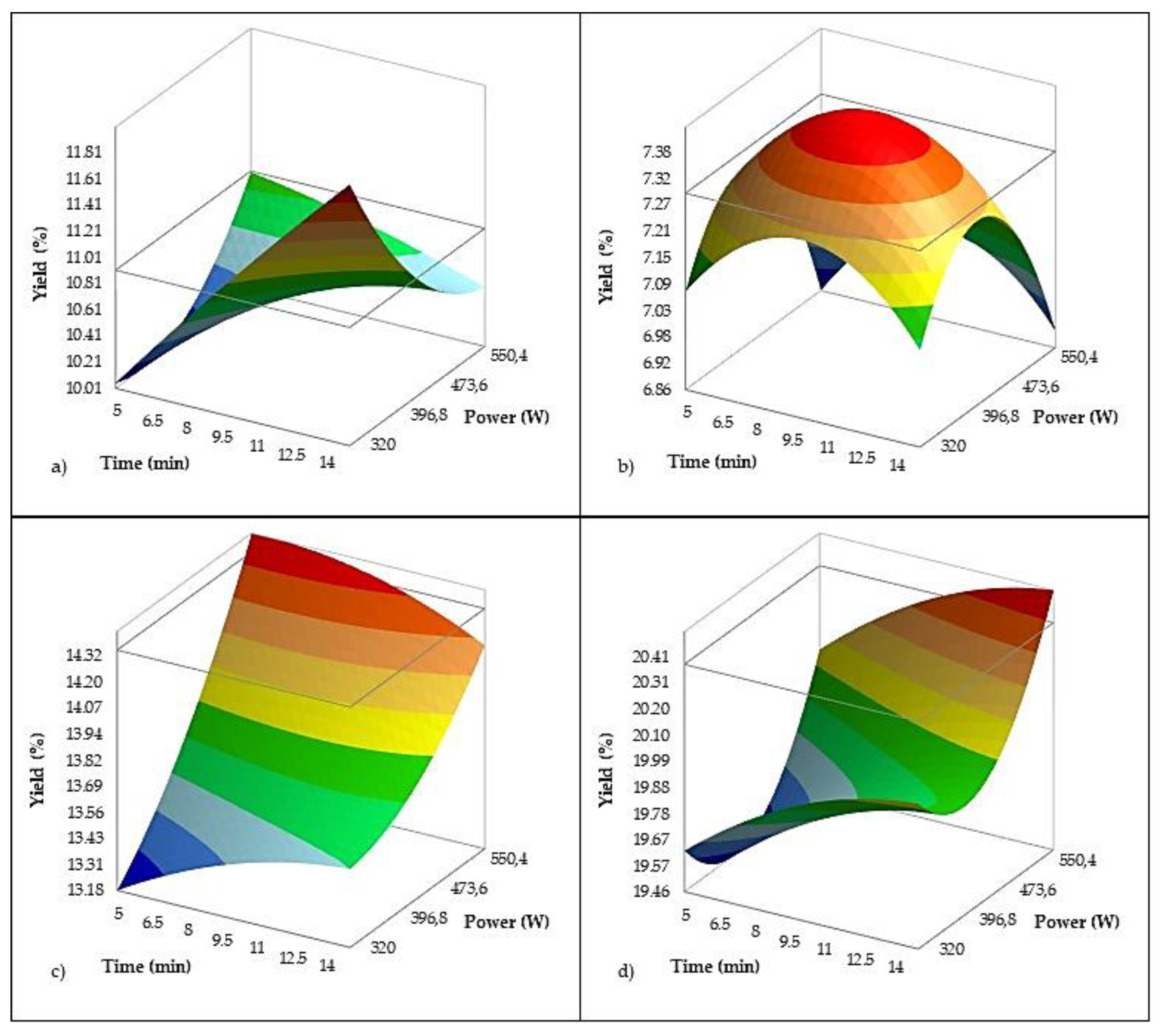

As mentioned earlier, Y was primarily influenced by olive variety. Although a slight increase in Y was observed with longer pretreatment times, neither treatment time (p = 0.093) nor power (p = 0.247) had a statistically significant main effect on Y (

Table 6,

Figure 4), suggesting that US treatment alone did not consistently enhance oil recovery across all conditions. However, a significant interaction between US power and the Oblica variety suggests that applying US can moderately enhance oil recovery in specific varieties, most likely by promoting cell wall disruption and facilitating oil release. Compared to the control, the application of 640 W US power for 10 min increased Y from Oblica by about 4%. These findings are consistent with previous reports emphasizing that varietal differences in cell structure and moisture or oil content play a dominant role in extractability [

77]. Similar improvements in Y have been reported in other varieties subjected to US pretreatment before malaxation under industrial conditions, such as a 3.4% increase in Ogliarola Garganica with a maturity index of 2.82 [

16], and increases of 4.4% and 4.6% in Nocellara and Coratina, respectively [

15]. Additionally, a 4.3% increase was observed in Chemlali after a 10-minute US treatment [

73].

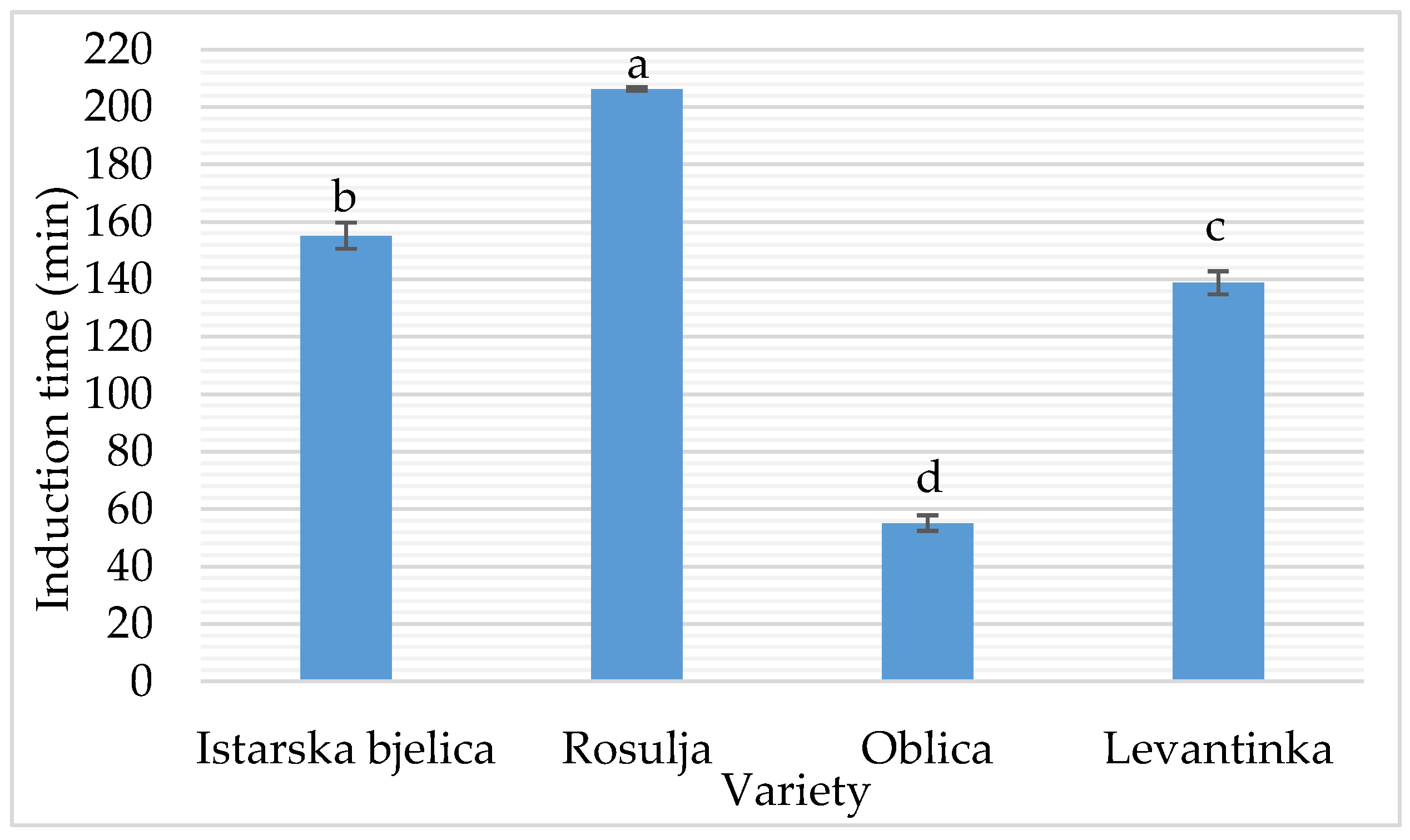

The oxidative stability index (OSI) is a critical parameter reflecting the resistance of VOO to lipid oxidation and serves as a strong predictor of shelf life. The model (

Table 6 and

Figure 5) developed for oxidative stability index (OSI) exhibited a high level of predictive accuracy (R² = 0.988; adjusted R² = 0.985), indicating that the combined effects of US parameters and olive variety explain nearly all the observed variability in OSI. Among the US factors, treatment time had a statistically significant negative effect on OSI (p = 0.004), suggesting that prolonged sonication promotes oxidative degradation. This aligns with previous reports demonstrating that acoustic cavitation during US processing can induce localized heating and the formation of reactive oxygen species, accelerating oxidative processes [

78]. In contrast, US power alone did not have a significant effect (p = 0.477), indicating that the duration of exposure is a more critical factor for oxidative damage than power intensity. These findings are supported by Iqdiam et al. [

12], who observed a significant decrease in OSI after 8 and 10 minutes of both direct and indirect high-power US treatment compared to shorter exposure times (0–6 min), for two different olive varieties. They reported that 10 minutes of direct high-power US caused an approximate 8% reduction in induction time, with no significant changes observed for shorter durations (p > 0.05). This indicates that US begins to compromise oxidative stability only beyond a critical exposure threshold.

However, the negative interaction of power in Istarska Bjelica observed (

Figure 5a) here suggests that even phenolic-rich cultivars [

79] may be susceptible to oxidation when exposed to excessive US energy, confirming the narrow margin between beneficial extraction and detrimental degradation. Interestingly, the interaction of US power in Levantinka (

Figure 5d) was significant and positive, suggesting that in this variety, moderate US energy may help release more antioxidants without causing substantial oxidative stress. This agrees with results from Servili et al. [

15], who reported that under optimized conditions, in their case increased pressure, US can selectively enhance antioxidant extraction and improve oil quality. Together, these findings underscore the importance of variety-specific optimization of US parameters. Short to moderate treatment durations may offer benefits, while prolonged sonication appears to pose a risk to oxidative stability, particularly in more sensitive varieties.

The regression model for the content of linoleic acid (

Table 6,

Figure 6), displayed excellent predictive power (R² = 0.997; adjusted R² = 0.996). The models were created with mass fractions in mg/g of oil (not in percentages) so that small changes in concentration can be recognized and a higher precision and resolution of the model is achieved. US power emerged as a significant negative factor (p = 0.037), indicating that higher sonication intensity reduces linoleic acid levels, likely through oxidative degradation triggered by cavitation-generated radicals. In contrast, treatment time did not have a statistically significant main effect (p = 0.603), suggesting that long exposures alone may not significantly alter linoleic acid content unless combined with high power. This aligns with the observed decline in OSI, suggesting that US-induced oxidation may target unsaturated lipids like linoleic acid.

Interestingly, in the Oblica variety (

Figure 6c), treatment with high-power ultrasound (p < 0.001) resulted in a significant decrease in linoleic acid content. This finding is not unexpected, as Oblica typically contains at least twice the amount of linoleic acid compared to the other varieties studied (

Table 2). Linoleic acid is considerably more susceptible to oxidation than oleic acid, and high-power ultrasound (20 kHz, 150 W) has been shown to accelerate oxidative processes in oils. As reported by Chemat et al. [

80], sonication of refined sunflower oil for just 2 minutes increased peroxide values from 5.38 to 6.33 meq O₂/kg, indicating the onset of oxidation. Although there were no significant immediate changes in fatty acid composition, the volatile profile in their study showed the formation of hexanal and limonene resulting from sonication.

The regression model for total phenolic compounds (

Table 6,

Figure 7) showed a strong fit (R² = 0.966; adjusted R² = 0.962), confirming that besides variety, US processing influences the phenolic profile of VOO. Among US parameters, treatment duration had a highly significant negative effect (–12.653 mg/kg per minute, p < 0.001), while US power was not a significant predictor. However, the interaction between sonication time and the variety Istarska Bjelica was significant and positive (p = 0.021), suggesting that this variety is less sensitive to phenolic losses at longer treatment times. Reports on US implementation in VOO production show that its effect can be highly dependent on the variety and treatment conditions. Several authors have also reported a significant increase in phenolic compounds following US treatment which was specific to chemical structure. Tamborrino et al. [

9] observed a 41 % increase in TPC and 68 % increase in oleacein in the Peranzana variety, while oleocanthal increased only slightly (~10 %), and phenolic alcohols decreased. Oils extracted with the application of US from Ogliarola garganica variety analyzed by Taticchi et al. [

16] showed TPC increase of 10 % which was related to oleuropein aglycon species. Servilli et al. [

15] reported a 28 % increase in TPC in the Nocellara variety and notable increases in oleocanthal in both Nocellara and Coratina varieties (39 % and 19 %, respectively), along with increases in ligstroside and tyrosol. Conversely, Gila et al. [

17] found that phenolic content was generally not affected by US treatment and even observed a slight decrease in Arbequina oils, which was attributed to moderate temperature rises during treatment.

On the other hand, Iqdiam et al. [

12] reported that after 10 minutes of direct high-power US treatment, total polyphenol levels were significantly reduced, by approximately 19% in Arbequina and 22% in Frantoio, indicating a substantial loss of antioxidants under extended sonication. This is consistent with the findings of Jiménez et al. [

74], who reported that US exposure can induce phenolic degradation. These differing findings can be explained by the dual role of US. On one hand, US enhances the extraction of phenolic compounds by disrupting cellular structures and facilitating the release of bound phenolics [

3]. On the other hand, it may simultaneously promote oxidative processes, leading to the consumption of these compounds as they act as primary antioxidants to neutralize US-induced free radicals [

81]. This mechanism is supported by the observed decreases in OSI and linoleic acid content, suggesting a coupled degradation pathway whereby phenolics are depleted to counteract oxidation, subsequently facilitating the degradation of unsaturated fatty acids and reducing overall oil stability. The results in Istarska Bjelica imply that brief US treatments can still effectively enhance phenolic content without triggering significant oxidative losses, underscoring the importance of carefully optimizing sonication duration to balance these competing effects.

The regression model for α-tocopherol content (

Table 6,

Figure 8) (R² = 0.653; adjusted R² = 0.607) explained a moderate proportion of the variability, reflecting the complex behavior of tocopherols under US processing. Treatment time and US power alone were not significant, but their interaction was highly significant (p < 0.0001), indicating that the combination of higher US intensity and longer exposure can strongly affect tocopherol levels probably due to enhanced release from cellular matrices, as observed in Rosulja (24% increase). Taticchi et al. [

16] and Pagano et al. [

10] also observed an increase in α-tocopherol concentration (11%) in Ogliarola garganica, while Gila et al. [

17] reported no effect of sonication process on tocopherol content. In present study, US showed declined α-tocopherol content in all investigated varieties except aforementioned Rosulja (

Figure 8).

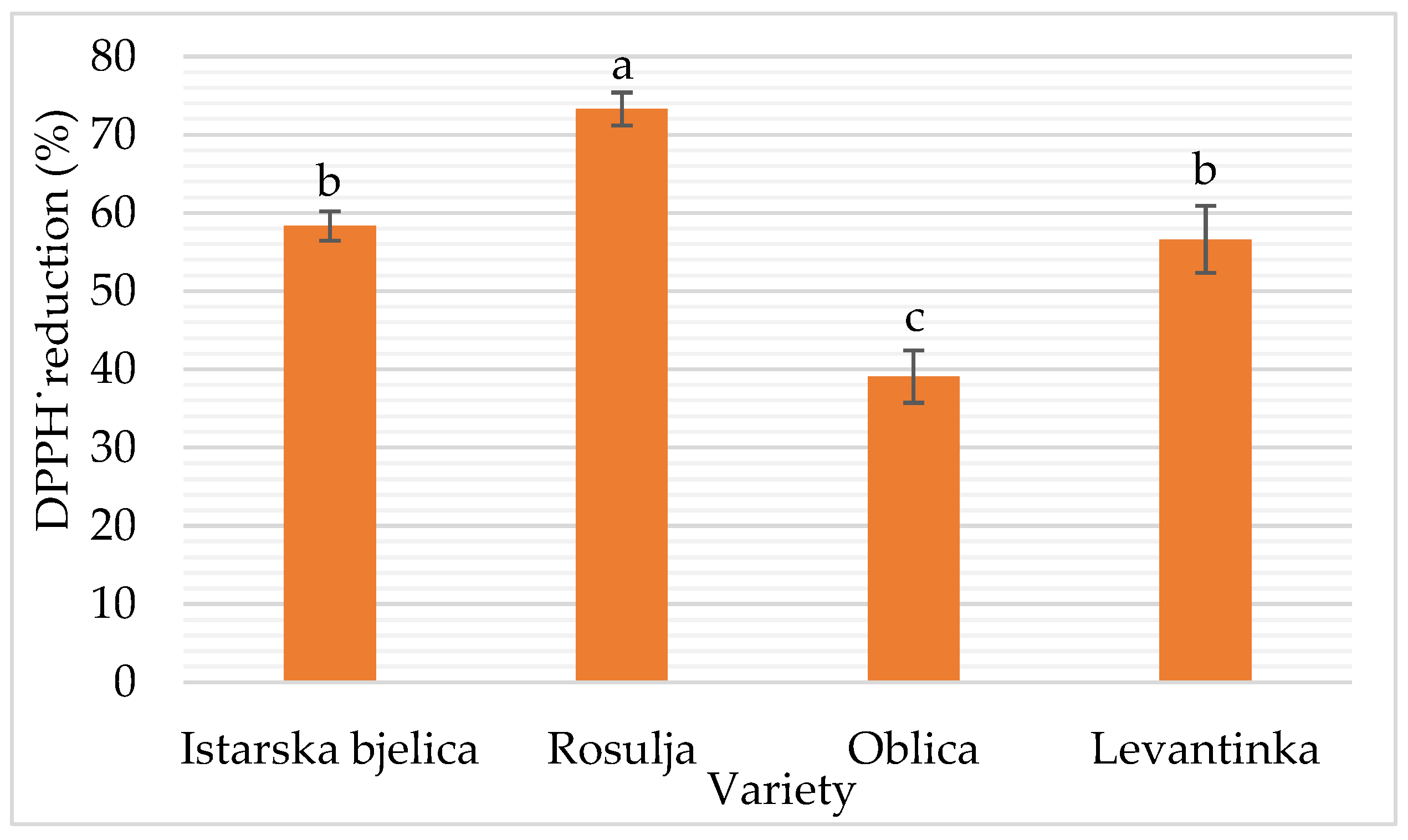

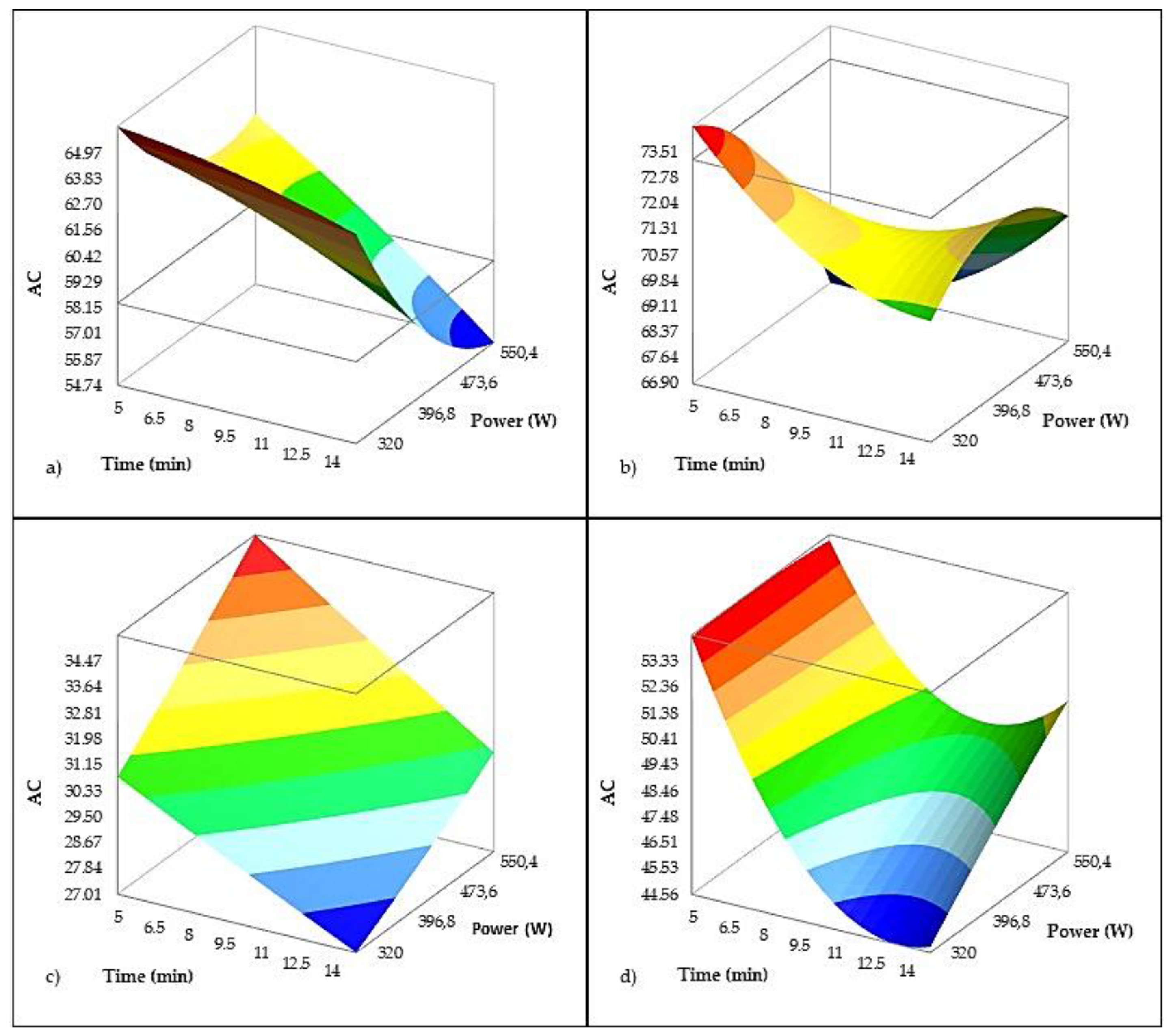

The regression model for antioxidant capacity (AC), expressed as % DPPH radical reduction (

Table 6 and

Figure 9), demonstrated strong explanatory power (R² = 0.958; adjusted R² = 0.952). Time had a highly significant negative effect (p < 0.0001), indicating that longer ultrasound (US) exposure reduced AC. This effect is likely due to temperature increases during sonication, which can lead to the degradation of antioxidant compounds [

17]. In contrast, ultrasound power alone did not have a statistically significant effect (p = 0.272). However, the interaction between power and the Istarska Bjelica variety showed a significant negative influence (p < 0.001), suggesting that higher US power reduces AC in this specific cultivar. These findings align well with the observed effects of US parameters on total phenolic content (TPC), the primary antioxidants in virgin olive oil (VOO). Similarly, Aydar et al. [

75] reported a decrease in AC with prolonged US treatment in the Edremit cultivar, attributing this to a reduction in TPC. Conversely, in the Rosulja variety, the interaction with treatment time had a significant positive effect on AC, potentially linked to an increase in α-tocopherol content observed with extended US exposure.