1. Introduction

It is a universal phenomenon in modern society that people feel negative emotions such as anxiety and fear toward mathematics. According to the results of the 2022 PISA (Programme for International Student Assessment) survey conducted by the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD), 59.8% of 15-year-olds in OECD member countries and 68.8% in Japan responded “completely agree” or “agree” to the statement “I often worry that it will be difficult for me in mathematics classes” (OECD, 2024). Additionally, 64.9% of 15-year-olds in OECD member countries and 68.6% in Japan responded “completely agree” or “agree” to the statement “I worry that I will get poor marks in mathematics” (OECD, 2024). These findings suggest that anxiety and fear toward mathematics are widespread and culturally pervasive.

Such negative emotions have long been a central focus of affective research in mathematics, beginning with Gough’s (1954) study on “mathemaphobia” and Dreger & Aiken’s (1957) work on “number anxiety” (Batchelor et al., 2019). These constructs have since evolved into what is now widely recognized as “math anxiety,” a psychological phenomenon extensively studied in educational psychology.

Math anxiety is defined as feelings of tension and apprehension that interfere with the manipulation of numbers and the solving of mathematical problems in a wide variety of contexts, including daily life and academic settings (Ramirez et al., 2018). While math anxiety shares similarities with general anxiety and test anxiety, it is considered a distinct construct. This distinction is supported by research showing a relatively low contribution from shared genetic factors (approximately 9%) and non-shared environmental factors (approximately 4%) in comparison to other types of anxiety (Wang et al., 2014), as well as unique correlation patterns with external criterion variables (Hembree, 1990).

The negative association between math anxiety and math learning and performance is one of the most robust and well-replicated findings in the field. Meta-analyses have consistently shown that math anxiety is significantly negatively correlated with learning motivation (Li et al., 2021), the extent of high school math learning (Hembree, 1990), and math performance (Barroso et al., 2021). Furthermore, longitudinal and panel data studies have demonstrated that math anxiety negatively predicts math learning and performance over time (Ahmed et al., 2012; Gunderson et al., 2018). These findings underscore the importance of identifying instructional practices that can alleviate math anxiety, thereby promoting more positive learning outcomes.

One such instructional practice is cognitive activation by math teachers, which has emerged as a significant factor in reducing math anxiety. Cognitive activation refers to instructional strategies that promote constructive, reflective, and higher-order thinking in learners (Baumert et al., 2010). In mathematics lessons, this often involves encouraging students to reflect on problem-solving processes and providing them with tasks that require extended reasoning (Burge et al., 2015). The core components of cognitive activation include: (1) activating prior knowledge and fostering conceptual understanding, (2) posing problems that engage learners in higher-order thinking, and (3) facilitating meaningful participation in classroom discourse (Lipowsky et al., 2009). These practices align with constructivist learning theories, such as Piaget’s and Vygotsky’s, and emphasize the active, constructive, and interactive modes of learning in the ICAP framework (Chi, 2009).

Empirical research has indicated that cognitive activation can reduce math anxiety. For example, Zuo et al. (2024) used structural equation modeling on data from 17,112 eighth-grade students in China and found that cognitive activation was negatively associated with math anxiety, both directly and indirectly via self-efficacy. Similarly, Liu et al. (2022) conducted a multilevel analysis on 3,088 fourth-grade students and 57 teachers in China and found a direct negative relationship between cognitive activation and math anxiety. Burge et al. (2015), using PISA 2012 data from England, also reported that cognitive activation was negatively associated with math anxiety. However, given that instructional effectiveness often varies by cultural and national context (e.g., Liu et al., 2022), the extent to which these findings generalize to Japanese students remains unclear.

Notably, most previous studies have focused on linear associations between cognitive activation and math anxiety. However, some evidence suggests a curvilinear (inverted U-shaped) relationship between cognitive activation and math performance: moderate levels of cognitive activation optimize performance, while very low or very high levels may impair it (Caro et al., 2016; Nachbauer, 2024). Given the strong link between math anxiety and performance, it is plausible to hypothesize a similar nonlinear relationship with math anxiety—that is, math anxiety may be lowest at moderate levels of cognitive activation, but higher at both low and excessive levels.

In addition, this relationship may be moderated by socioeconomic status (SES). SES reflects access to various resources—economic, social, cultural, and human—that affect educational outcomes (National Centre for Education Statistics, 2012). Burge et al. (2015) found that the negative relationship between cognitive activation and math anxiety was significant only among students with medium to high levels of economic, social, and cultural capital. Although their study focused on England, similar patterns have been observed in other outcomes. For example, Caro et al. (2016) found that cognitive activation had a greater positive impact on academic achievement for students with higher SES. These findings suggest that the effectiveness of cognitive activation may depend on students’ SES, with diminished effects among students with lower SES.

Moreover, it is important to consider both individual-level (Student SES) and contextual-level (School SES) factors. School SES reflects the average SES of the school’s student body and shapes the educational environment through access to material and human resources (Chiu & Khoo, 2005), teacher quality, peer effects (Van Ewijk & Sleegers, 2010), and classroom discipline (Willms, 2010). High-SES schools are generally better equipped to support academic achievement (Perry et al., 2022). In Japan, the school system further stratifies students into academically ranked high schools, often in line with socioeconomic background (Takashiro, 2024; Matsuoka, 2015). Thus, School SES may also moderate the link between cognitive activation and math anxiety, beyond the effects of Student SES alone.

Self-efficacy—students’ belief in their ability to perform specific tasks—may be another moderating factor. According to Bandura’s (1986) social cognitive theory, self-efficacy influences motivation, learning engagement, and emotional responses. Students with low self-efficacy may be less responsive to cognitively demanding instruction, potentially limiting the anxiety-reducing benefits of cognitive activation (Shimizu, 2025). In contrast, students with high self-efficacy are more likely to engage with cognitively activating tasks, which may reduce their math anxiety. Although prior studies have not directly tested this interaction, research on disciplinary climate in math classrooms has shown that the positive effect of a structured environment on achievement is contingent on students’ level of self-efficacy (Cheema & Kitsantas, 2014).

Based on this theoretical and empirical background, the present study aims to investigate: (1) the curvilinear effect of cognitive activation on math anxiety and (2) the moderating effects of Student SES, School SES, and self-efficacy on this relationship.

Hypothesis 1. Cognitive activation has a negative relationship with math anxiety.

Hypothesis 2. Cognitive activation has a negative curvilinear relationship with math anxiety.

Hypothesis 3. Student SES moderates the negative relationship between cognitive activation and math anxiety.

3-a. When Student SES is high, the negative relationship between cognitive activation and math anxiety becomes stronger.

3-b. When Student SES is low, the negative relationship between cognitive activation and math anxiety becomes weaker.

Hypothesis 4. School SES moderates the negative relationship between cognitive activation and math anxiety.

4-a. When school SES is high, the negative relationship between cognitive activation and math anxiety becomes stronger.

4-b. When school SES is low, the negative relationship between cognitive activation and math anxiety becomes weaker.

Hypothesis 5. Self-efficacy moderates the negative relationship between cognitive activation and math anxiety.

5-a. When self-efficacy is high, the negative relationship between cognitive activation and math anxiety becomes stronger.

5-b. When self-efficacy is low, the negative relationship between cognitive activation and math anxiety becomes weaker.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Data

In this study, I used the data from students in Japan (valid responses: 182 schools [departments], 5760 students) from the PISA 2022 dataset published by the OECD. This large-scale international survey, conducted every three years, targets 15-year-old learners to assess their proficiency in essential academic domains. Beyond the core evaluations in reading, mathematics, and science, PISA integrates multi-actor questionnaires involving students, caregivers, educators, and school administrators to explore how diverse contextual and individual attributes relate to academic literacy outcomes (OECD, 2023). The 2022 iteration engaged nearly 690,000 participants, representing a global cohort of 15-year-olds.

2.2. Measures

2.2.1. Math Anxiety

As an indicator of math anxiety, I used the math anxiety score (ANXMAT) developed by the OECD (2023). This score was calculated using item response theory (IRT) based on students’ responses to six items related to math anxiety (e.g., “I often worry that it will be difficult for me in math class.”). The items were measured on a four-point Likert scale ranging from Strongly agree (1) to Strongly disagree (4). The responses were scaled using the Partial Credit Model (PCM) to ensure comparability with previous PISA cycles. The resulting score was standardised so that the OECD average was 0 with a standard deviation of 1, where higher values indicate greater math anxiety.

2.2.2. Cognitive Activation

Cognitive activation in mathematics lessons was measured using two scales developed by the OECD (2023): the Cognitive Activation for Fostering Reasoning (COGACRCO) and Cognitive Activation for Encouraging Mathematical Thinking (COGACMCO). These scores were calculated using IRT based on responses to 18 items designed to assess the extent to which students are exposed to cognitively demanding instructional practices.

The COGACRCO scale captures how frequently students are encouraged to articulate their thought processes and solve complex problems independently. Sample items include “The teacher asks us to decide on our own procedures for solving complex problems” and “The teacher asks us to explain how we solved a problem.”

The COGACMCO scale reflects how often students are prompted to reflect deeply on problems and engage in extended reasoning. Sample items include “The teacher asks questions that make us reflect on the problem” and “The teacher presents problems that require us to think for an extended time.”

Both scales used a four-point Likert scale ranging from Never or hardly ever (1) to In all or nearly all lessons (4). Responses were scaled using the PCM and standardised across OECD countries (M = 0, SD = 1). Higher scores indicate greater exposure to cognitively activating teaching practices.

In this study, cognitive activation was treated as a school-level variable by calculating the school-mean values of COGACRCO and COGACMCO, centered on the overall sample mean.

2.2.3. SES

Student SES was measured using the ESCS (Economic, Social and Cultural Status) index. This composite score is derived from students’ reports on their parents’ years of education, occupational status, and household possessions. The ESCS score was standardised to have a mean of 0 and a standard deviation of 1 across OECD countries, with higher scores indicating greater socioeconomic advantage.

School SES was calculated as the average of student SES scores at the school level, centered on the overall sample mean.

2.2.4. Math Self-Efficacy

Math self-efficacy was measured using the MATHEFF score developed by the OECD (2023), based on nine items assessing students’ confidence in handling formal and applied mathematical tasks (e.g., “Calculating how much more expensive a computer would be after adding tax”). Items were rated on a four-point scale from Not at all confident (1) to Very confident (4). Responses were scaled using the PCM and standardised (M = 0, SD = 1) across OECD countries, with higher scores reflecting greater self-efficacy in mathematics.

2.2.5. Gender

Gender was included as a control variable based on the item ST004Q01, in which students self-identified as female (1) or male (2). For this study, a male dummy variable was created, assigning 0 to females and 1 to males.

2.3. Analysis Strategies

The following analyses were conducted. First, I performed descriptive statistics (means and standard deviations) to understand overall trends in the variables used in this study. Second, to examine the curvilinear relationship between cognitive activation and math anxiety, and the moderating roles of SES and math self-efficacy, I conducted multilevel regression analyses using student and school-level weights (W_FSTUWT and W_SCHGRNRABWT, respectively). All models used random intercepts, as the estimated random slopes were zero or negative. The following four models were estimated:

Model 1 (Baseline Model): Included the male dummy variable (control), cognitive activation (linear and squared terms), student SES, school SES, and math self-efficacy as predictors, with math anxiety as the outcome.

Model 2: To examine the moderating effect of student SES, I added interaction terms between student SES and both the linear and squared terms of cognitive activation.

Model 3: To examine the moderating effect of school SES, I added interaction terms between school SES and both the linear and squared terms of cognitive activation.

Model 4: To examine the moderating effect of math self-efficacy, I added interaction terms between self-efficacy and both the linear and squared terms of cognitive activation.

3. Results

3.1. Descriptive Statistics

Table 1 presents the descriptive statistics for the variables used in this study. For student-level variables, the mean value for math anxiety was positive, and the mean value for math self-efficacy was negative. This indicates that, relative to the OECD average, 15-year-old students in Japan tend to experience higher math anxiety and lower self-efficacy.

Regarding school-level variables, the mean value of cognitive activation for fostering reasoning was approximately zero, while the mean value of cognitive activation for encouraging mathematical thinking was negative. These results suggest that, on average, Japanese math teachers implement cognitive activation strategies that foster reasoning at a level comparable to the OECD average, but make less frequent use of cognitive activation practices designed to promote extended mathematical thinking.

3.2. Relationship Between Cognitive Activation and Math Anxiety

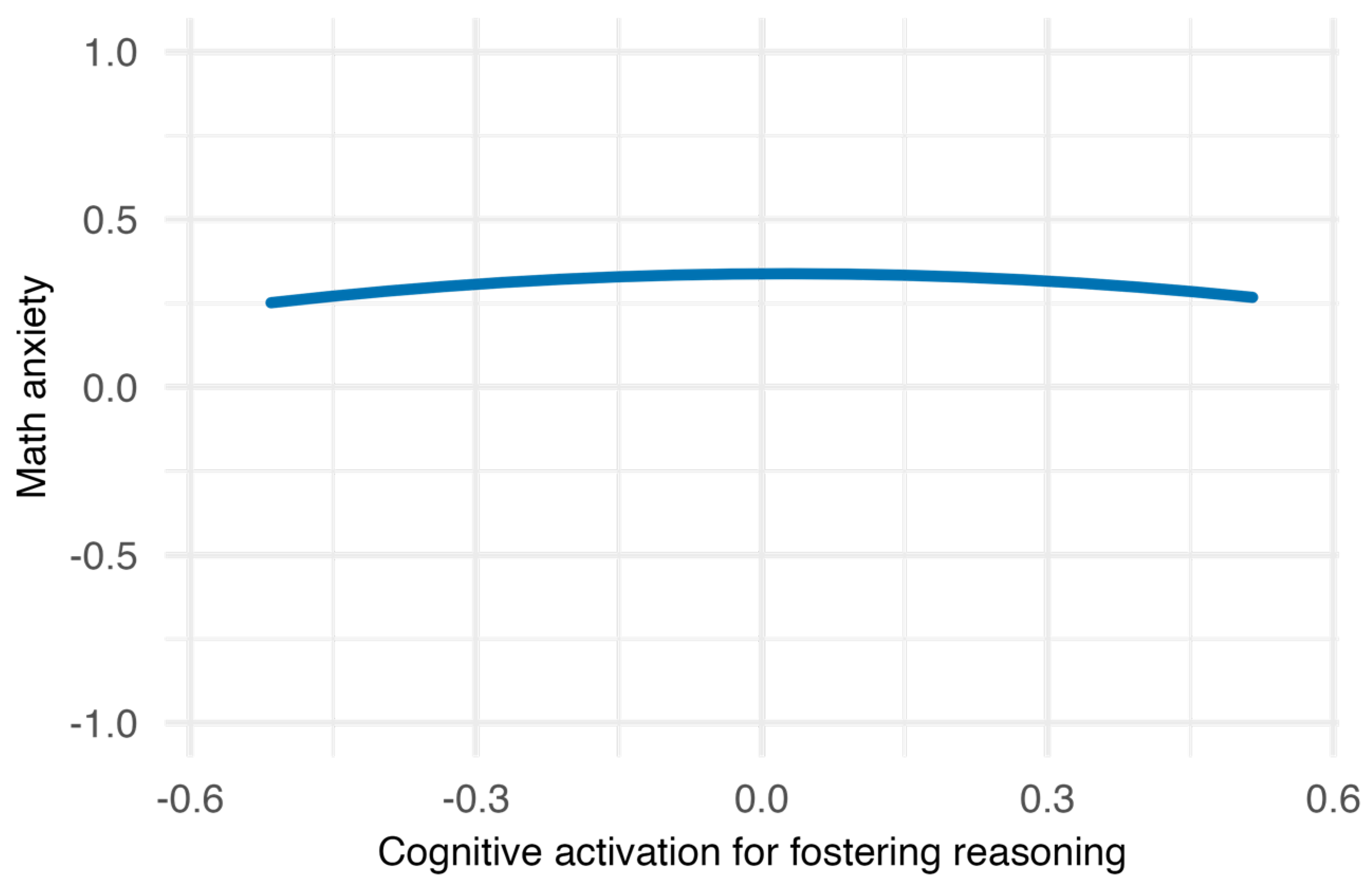

Table 2 shows the results of Model 1. When controlling for gender, self-efficacy, and SES, the squared term of cognitive activation for fostering reasoning was significantly negative in predicting math anxiety.

Figure 1, which visualizes the relationship over the 2.5th to 97.5th percentile range of cognitive activation for fostering reasoning, indicates a negative quadratic effect. However, the effect size was small, and the curve was nearly flat, suggesting that math anxiety remained nearly constant regardless of the level of cognitive activation for fostering reasoning.

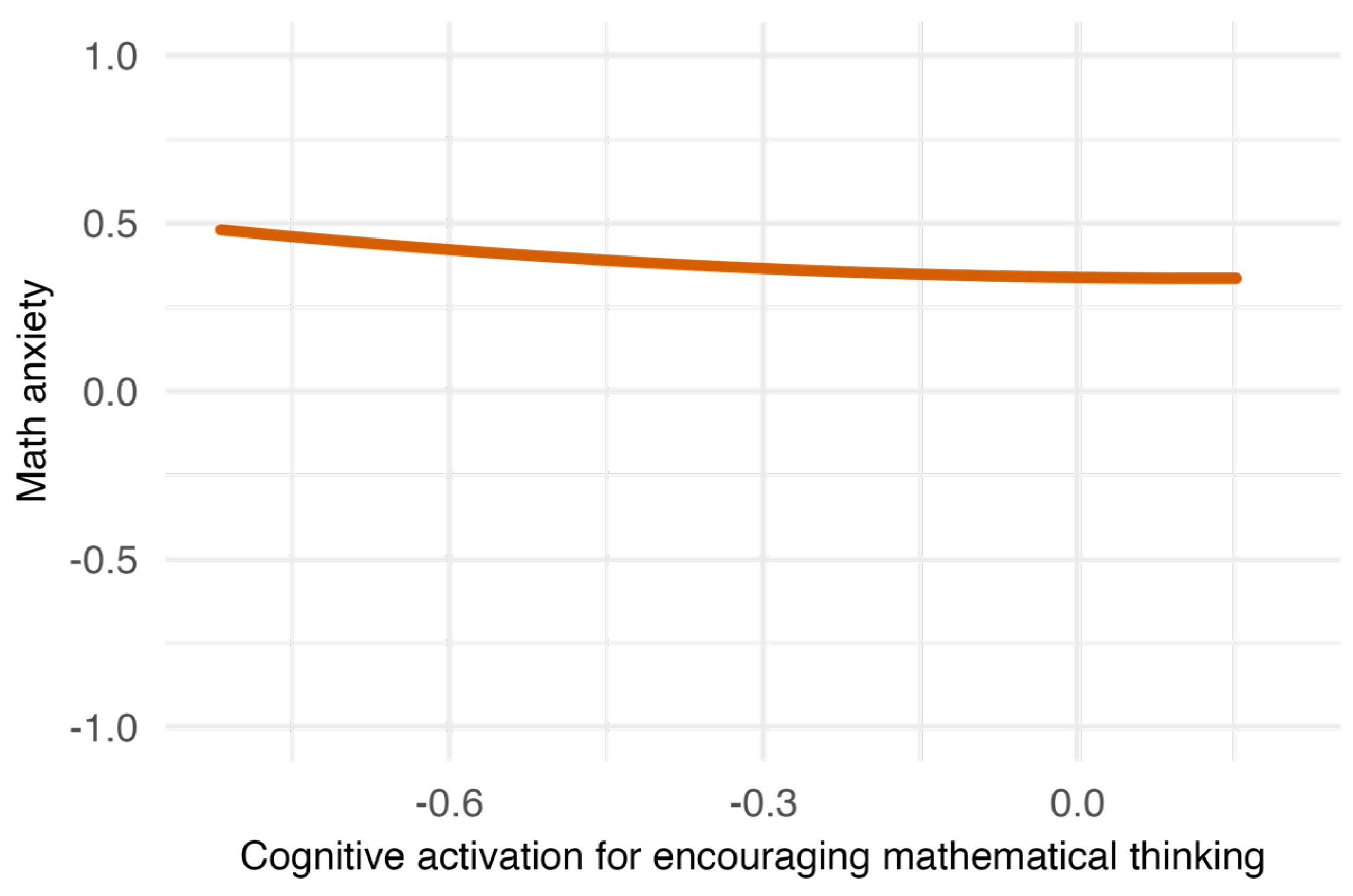

In contrast, the squared term of cognitive activation for encouraging mathematical thinking was significantly positive.

Figure 2 shows that math anxiety initially decreased as cognitive activation increased, but eventually plateaued. This implies that greater use of cognitive activation for encouraging mathematical thinking is associated with lower math anxiety, up to a point, beyond which additional activation no longer reduces anxiety.

Therefore, Hypotheses 1 and 2 were partially supported.

3.3. Moderating Effect of Student SES on the Relationship Between Cognitive Activation and Math Anxiety

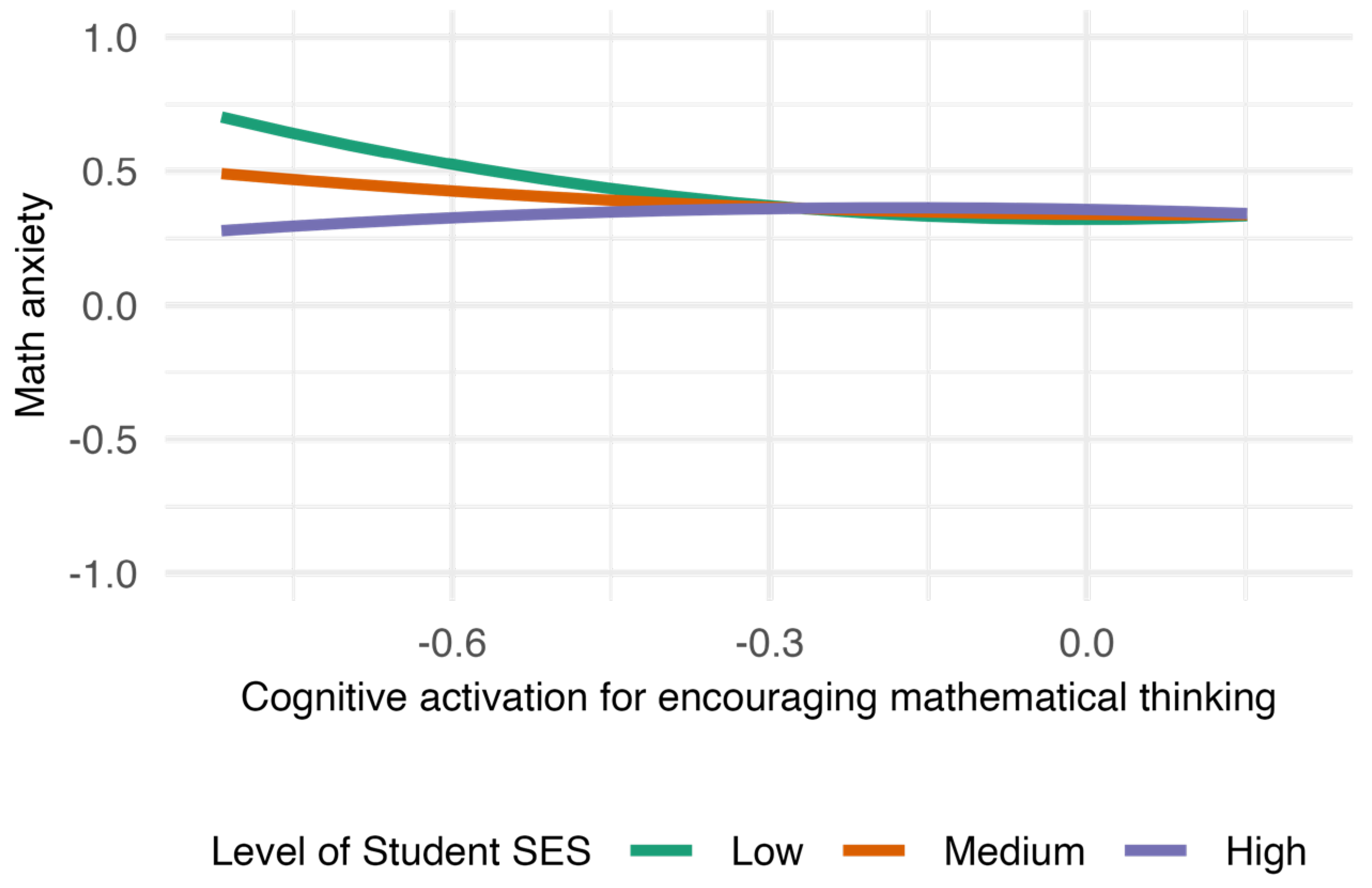

The results of Model 2 in

Table 2 show that the interaction between student SES and the squared term of cognitive activation for encouraging mathematical thinking was significantly negative.

Figure 3 visualizes this interaction.When student SES was low, increased cognitive activation initially reduced math anxiety, then leveled off. In contrast, when student SES was high, math anxiety remained relatively stable regardless of cognitive activation level. Therefore, Hypotheses 3-a and 3-b were not supported.

3.4. Moderating Effect of School SES on the Relationship Between Cognitive Activation and Math Anxiety

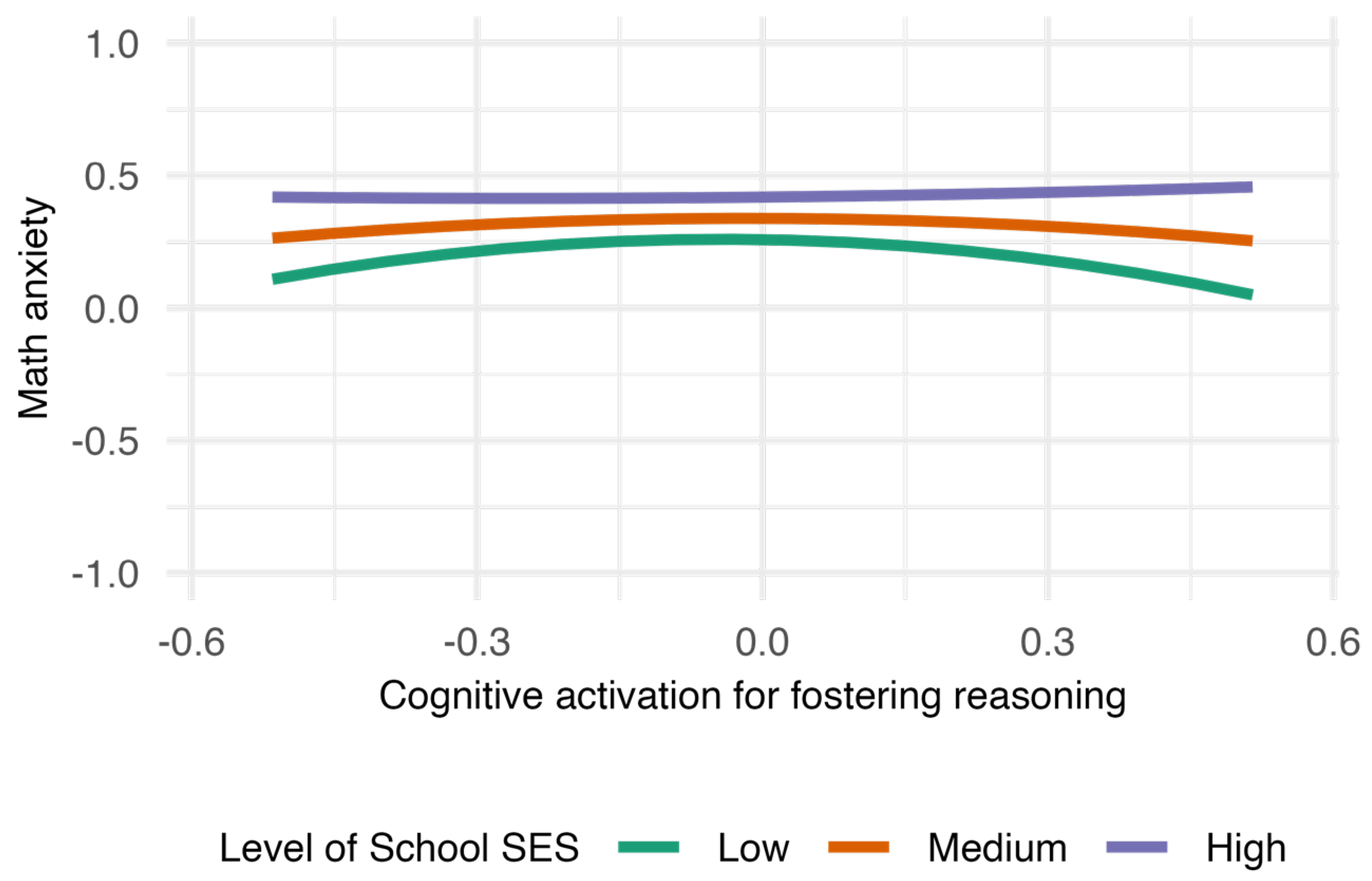

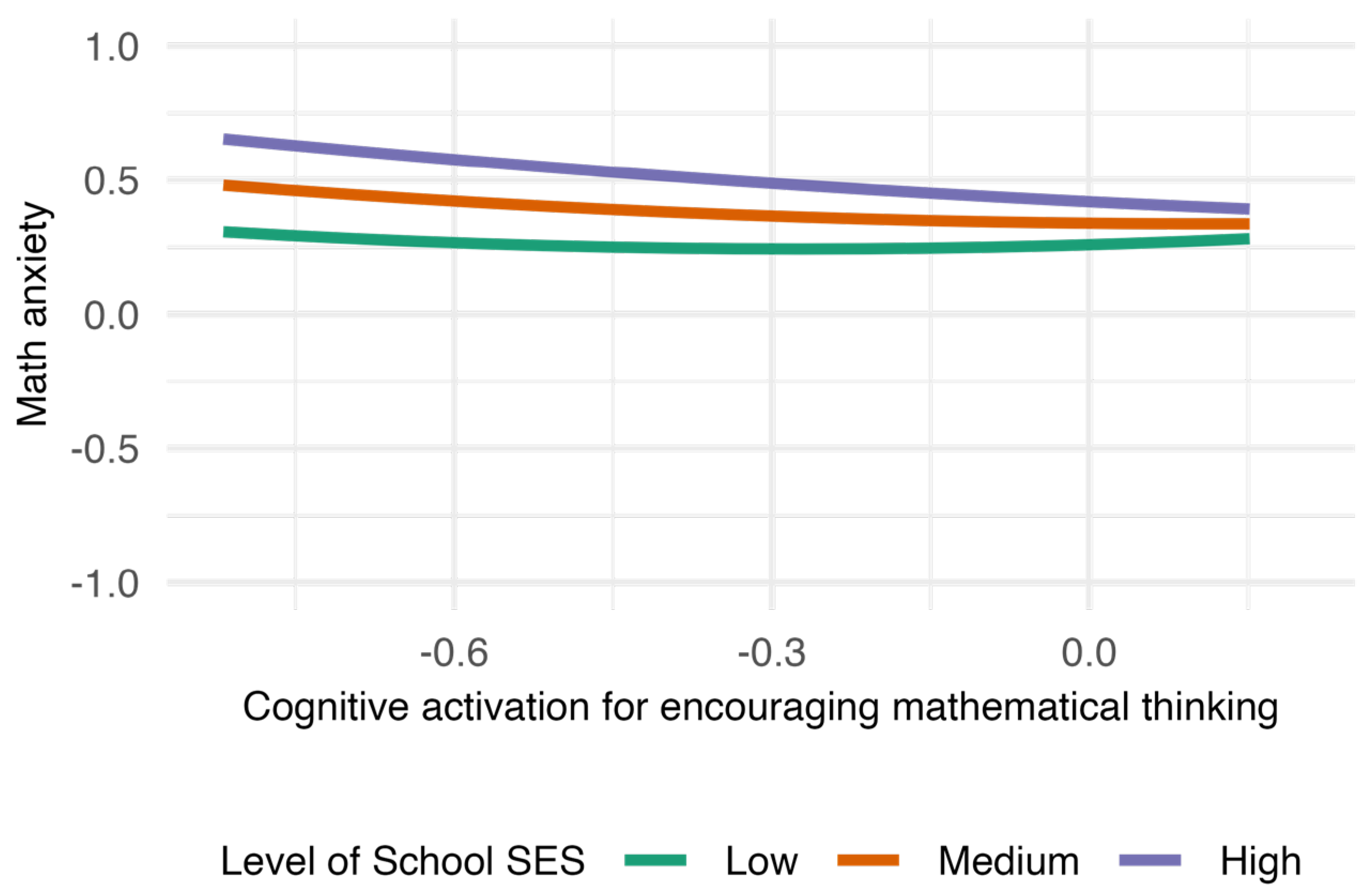

Model 3 results (

Table 2) indicate that the interaction between school SES and the squared term of cognitive activation for fostering reasoning was significantly positive, while the interaction between school SES and cognitive activation for encouraging mathematical thinking was significantly negative.

Figure 4 and

Figure 5 depict these results.

Figure 4 shows that in low-SES schools, both low and high levels of cognitive activation for fostering reasoning were associated with lower math anxiety, whereas moderate levels were associated with higher anxiety. In high-SES schools, math anxiety remained largely stable regardless of activation level.

Figure 5 illustrates that in high-SES schools, increased cognitive activation for encouraging mathematical thinking was associated with lower math anxiety. In contrast, in low-SES schools, the decline in anxiety with increasing activation was less pronounced, narrowing the gap between high- and low-SES schools at higher levels of activation.

Therefore, Hypothesis 4-a was partially supported, while Hypothesis 4-b was not supported.

3.5. Moderating Effect of Math Self-Efficacy on the Relationship Between Cognitive Activation and Math Anxiety

The results of Model 4 in

Table 2 indicate that math self-efficacy did not significantly moderate the relationship between either type of cognitive activation and math anxiety. Therefore, Hypothesis 5 was not supported.

4. Discussion

This study investigated the curvilinear effect of cognitive activation on math anxiety and the moderating effects of SES and self-efficacy, using the Japanese dataset from PISA 2022 and multilevel regression analysis (

Table 2,

Figure 1,

Figure 2,

Figure 3,

Figure 4 and

Figure 5). The results indicated that cognitive activation for fostering reasoning exhibited a negative curvilinear relationship with math anxiety; however, the magnitude of the effect was small, and the overall pattern was essentially flat. In contrast, cognitive activation for encouraging mathematical thinking was initially associated with a reduction in math anxiety, but this effect gradually plateaued. Therefore, Hypotheses 1 and 2 were partially supported.

Student SES negatively moderated the relationship between cognitive activation for encouraging mathematical thinking and math anxiety. Specifically, when student SES was low, increased cognitive activation was initially associated with lower math anxiety, but the effect diminished over time. Consequently, Hypotheses 3-a and 3-b were not supported. However, this trend contributed to a narrowing of the math anxiety gap between high- and low-SES school groups.

School SES moderated the relationship between cognitive activation and math anxiety. When school SES was low, both low and high frequencies of cognitive activation for fostering reasoning were associated with reduced math anxiety, whereas moderate levels were associated with higher anxiety. Conversely, in high-SES schools, increased cognitive activation for encouraging mathematical thinking was linked to reduced math anxiety, and the difference between high- and low-SES groups converged. Thus, Hypothesis 4-a was partially supported, while Hypothesis 4-b was not. Self-efficacy did not significantly moderate the relationship between cognitive activation and math anxiety, and Hypothesis 5 was not supported.

4.1. The Relationship Between Cognitive Activation and Math Anxiety

The present findings extend prior research on the link between cognitively demanding instruction and students’ emotional responses in mathematics. While previous studies (e.g., Zuo et al., 2024; Liu et al., 2022) found a linear negative association between cognitive activation and math anxiety, the present study revealed a nonlinear (curvilinear) relationship.

Specifically, the results suggest that greater use of cognitive activation strategies that encourage mathematical thinking initially reduces math anxiety but eventually plateaus. This pattern is consistent with earlier studies that identified beneficial effects of cognitive activation (Zuo et al., 2024; Liu et al., 2022), while also highlighting a limit to its effectiveness. One possible explanation is that increased cognitive activation promotes student engagement, thereby enhancing motivation and reducing anxiety. However, overuse without sufficient support or instructional scaffolding may lead to diminishing returns. Furthermore, as shown in

Table 1, Japanese math teachers tend to use these strategies less frequently than their international counterparts, which may reflect both cultural norms and gaps in teacher training or instructional design quality, potentially explaining the observed plateau.

In contrast, the relationship between cognitive activation for fostering reasoning and math anxiety was curvilinear but practically negligible. Visual inspection (

Figure 1) revealed a nearly flat pattern, suggesting that this form of activation may have limited influence on students’ emotional experiences. These findings imply that, for the purpose of reducing math anxiety, instructional strategies that promote mathematical thinking may be more effective than those aimed solely at fostering reasoning.

4.2. The Moderating Effect of SES on the Relationship Between Cognitive Activation and Math Anxiety

Contrary to the original hypothesis, the results revealed that when student SES was low, increased use of cognitive activation for encouraging mathematical thinking initially reduced math anxiety, though the effect faded at higher activation levels. Interestingly, this pattern contributed to closing the gap in math anxiety between high- and low-SES students. This suggests that cognitive activation may function as a compensatory strategy for students with fewer educational resources outside school.

This aligns with the idea that cognitively demanding teaching may provide low-SES students with opportunities to engage more deeply in math learning, compensating for the lack of informal learning experiences or support at home.

At the school level, in high-SES schools, frequent use of cognitive activation for encouraging mathematical thinking was consistently associated with reduced math anxiety. This is consistent with prior research (Perry et al., 2022) suggesting that high-SES schools often provide supportive environments and instructional resources that facilitate effective teaching. In Japan, teachers in high-SES schools also report higher instructional efficacy and job satisfaction (Matsuoka, 2015b), which may enable them to implement cognitively demanding practices more effectively.

In low-SES schools, an intriguing pattern emerged: math anxiety was lower when cognitive activation for fostering reasoning was used either infrequently or frequently, but higher when it was used moderately. This non-monotonic pattern may reflect the instability of instructional quality in under-resourced settings. For example, insufficiently scaffolded reasoning activities may overwhelm students, while minimal exposure may reduce anxiety simply by reducing academic challenge. These findings point to the need for improving instructional capacity in low-SES schools, so that cognitive activation can be used effectively to reduce anxiety and enhance learning outcomes.

4.3. The Moderating Effect of Math Self-Efficacy on the Relationship Between Cognitive Activation and Math Anxiety

Contrary to expectations, math self-efficacy did not significantly moderate the relationship between cognitive activation and math anxiety. Two potential explanations can be proposed. First, math self-efficacy may act as a mediator, rather than a moderator. Indeed, prior research (Zuo et al., 2024) has shown that cognitive activation enhances self-efficacy, which in turn reduces math anxiety. Second, the measure of math self-efficacy (MATHEFF) used in this study may not have fully captured the context-specific nature of self-efficacy relevant to instructional practices. That is, there may be a misalignment between students’ confidence in solving formal/applied problems and their emotional responses to cognitively activating instruction, especially when such instruction is inconsistent or poorly implemented.

4.4. Practical Implications

The findings of this study offer important implications for mathematics education. First, the results suggest that, regardless of gender, SES, or self-efficacy levels, using cognitive activation strategies that encourage mathematical thinking rather than fostering reasoning may be most effective in reducing math anxiety. Therefore, it is important for math teachers in high schools in Japan to actively use cognitive activation to encourage mathematical thinking, regardless of the characteristics of the school, teachers, or students, in order to reduce math anxiety and improve the quality and outcomes of math learning. Second, it was suggested that math teachers' active use of these strategies could reduce math anxiety among low-SES students, who tend to have limited access to math learning resources outside of school, thereby narrowing the gap with high-SES students. It is important for math teachers to actively use cognitive activation to encourage mathematical thinking as compensatory educational support for low-SES students who are behind in the quality and outcomes of their learning. Third, it was suggested that math teachers could reduce math anxiety by actively using cognitive activation to foster reasoning in low SES schools, where students have inadequate learning environments and teachers have insufficient competence. This suggests that cognitive activation can function as a compensatory instructional strategy that promotes fairness in math education, even when educational resources are limited. Finally, to address the tendency of Japanese mathematics teachers to utilise cognitive activation less than their international counterparts (see

Table 1), it is important to strengthen the introduction of cognitive activation in teacher training and teacher education curricula.

4.5. Limitations

This study has several limitations that should be acknowledged. First, the PISA 2022 dataset is cross-sectional, which precludes strong causal inference. Future studies should adopt longitudinal panel designs that track changes in cognitive activation and math anxiety over time. Second, due to data constraints, cognitive activation was analyzed as a school-level aggregate rather than a classroom-level variable. This may reduce the ecological validity of the findings. Future research should seek to obtain classroom-specific identifiers to enable finer-grained analysis. Third, the study focused exclusively on 15-year-old students in Japan. As such, the generalizability of the findings to younger or older age groups remains uncertain. Future studies should investigate whether the relationships observed here vary by developmental stage, particularly among elementary and lower secondary students.

5. Conclusions

This study examined the curvilinear effect of cognitive activation on math anxiety and the moderating roles of student SES, school SES, and math self-efficacy using data from 15-year-old students in Japan. The findings revealed that while cognitive activation for encouraging mathematical thinking was generally effective in reducing math anxiety, its benefits diminished at higher levels. Moreover, student SES and school SES moderated this relationship in complex ways, suggesting that cognitive activation may function as a compensatory tool to support students from disadvantaged backgrounds. Contrary to expectations, self-efficacy did not moderate the relationship, indicating the need for further investigation into its role.

Overall, this study contributes to understanding how cognitively demanding instruction can shape students’ emotional responses to mathematics. It emphasizes the importance of implementing cognitive activation strategies that encourage deep thinking, especially in educational contexts marked by socioeconomic disparities. Future research should build on these findings using longitudinal and classroom-level data to further clarify the mechanisms by which instructional practices influence math anxiety across developmental stages.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The present study used data from the PISA 2022 cycle. Therefore, it was presumed that the OECD had obtained the necessary ethical approvals from all participants. As this was a secondary analysis of publicly available data, further ethical approval was not applicable. The study adhered to the ethical principles of the Committee on Publication Ethics (COPE) and was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

This article is a revised and expanded version of a paper originally written in Japanese, entitled “数学教師の認知的活性化は数学不安を低減しうるか?” (“Can Cognitive Activation by Math Teachers Reduce Math Anxiety?”), published in Shoto Kyoiku Ronshu: The Japanese Journal of Primary Education, Vol. 26, pp. 38–47, by The Primary Education Society, Kokushikan University.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflicts of interest.

References

- Ahmed, W., Minnaert, A., Kuyper, H., & Van Der Werf, G. (2012). Reciprocal relationships between math self-concept and math anxiety. Learning and Individual Differences, 22(3), 385–389. [CrossRef]

- Bandura, A. (1986). Social foundations of thought and action: A social cognitive theory. Prentice-Hall, Inc.

- Barroso, C., Ganley, C. M., McGraw, A. L., Geer, E. A., Hart, S. A., & Daucourt, M. C. (2021). A meta-analysis of the relation between math anxiety and math achievement. Psychological Bulletin, 147(2), 134–168. [CrossRef]

- Batchelor, S., Torbeyns, J., & Verschaffel, L. (2019). Affect and mathematics in young children: An introduction. Educational Studies in Mathematics, 100(3), 201–209. [CrossRef]

- Baumert, J., Kunter, M., Blum, W., Brunner, M., Voss, T., Jordan, A., Klusmann, U., Krauss, S., Neubrand, M., & Tsai, Y.-M. (2010). Teachers’ Mathematical Knowledge, Cognitive Activation in the Classroom, and Student Progress. American Educational Research Journal, 47(1), 133–180. [CrossRef]

- Burge, B., Lenkeit, J., & Sizmur, J. (2015). PISA in practice. Cognitive activation in maths: How to use it in the classroom. National Foundation for Educational Research.

- Caro, D. H., Lenkeit, J., & Kyriakides, L. (2016). Teaching strategies and differential effectiveness across learning contexts: Evidence from PISA 2012. Studies in Educational Evaluation, 49, 30–41. [CrossRef]

- Cheema, J. R., & Kitsantas, A. (2014). Influences of disciplinary classroom climate on high school student self-efficacy and mathematics achievement: A look at gender and racial–ethnic differences. International Journal of Science and Mathematics Education, 12(5), 1261–1279. [CrossRef]

- Chi, M. T. H. (2009). Active-Constructive-Interactive: A conceptual framework for differentiating learning activities. Topics in Cognitive Science, 1(1), 73–105. [CrossRef]

- Chiu, M. M., & Khoo, L. (2005). Effects of resources, inequality, and privilege bias on achievement: Country, school, and student level analyses. American Educational Research Journal, 42(4), 575–603. [CrossRef]

- Dreger, R. M., & Aiken, L. R. (1957). The identification of number anxiety in a college population. Journal of Educational Psychology, 48(6), 344–351. [CrossRef]

- Gough, M. F. (1954). Why failures in mathematics? Mathemaphobia: Causes and treatments. The Clearing House, 28(5), 290–294.

- Gunderson, E. A., Park, D., Maloney, E. A., Beilock, S. L., & Levine, S. C. (2018). Reciprocal relations among motivational frameworks, math anxiety, and math achievement in early elementary school. Journal of Cognition and Development, 19(1), 21–46. [CrossRef]

- Hembree, R. (1990). The nature, effects, and relief of mathematics anxiety. Journal for Research in Mathematics Education, 21(1), 33–46. [CrossRef]

- Li, Q., Cho, H., Cosso, J., & Maeda, Y. (2021). Relations between students’ mathematics anxiety and motivation to learn mathematics: A meta-analysis. Educational Psychology Review, 33(3), 1017–1049. [CrossRef]

- Lipowsky, F., Rakoczy, K., Pauli, C., Drollinger-Vetter, B., Klieme, E., & Reusser, K. (2009). Quality of geometry instruction and its short-term impact on students’ understanding of the Pythagorean Theorem. Learning and Instruction, 19(6), 527–537. [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y., Wang, C., Liu, J., & Liu, H. (2022). The role of cognitive activation in predicting mathematics self-efficacy and anxiety among internal migrant and local children. Educational Psychology, 42(1), 83–107. [CrossRef]

- Matsuoka, R. (2015a). School socioeconomic compositional effect on shadow education participation: Evidence from Japan. British Journal of Sociology of Education, 36(2), 270–290. [CrossRef]

- Matsuoka, R. (2015b). School socioeconomic context and teacher job satisfaction in Japanese compulsory education. Educational Studies in Japan, 9, 41–54. [CrossRef]

- Nachbauer, M. (2024). How schools affect equity in education: Teaching factors and extended day programs associated with average achievement and socioeconomic achievement gaps. Studies in Educational Evaluation, 82, 101367. [CrossRef]

- National Center for Education Statistics. (2012). Improving the measurement of socioeconomic status for the national assessment of educational progress: A theoretical foundation. National Center for Education Statistics. https://nces.ed.gov/nationsreportcard/pdf/researchcenter/socioeconomic_factors.pdf.

- OECD. (2023). PISA 2022 Results (Volume I): The state of learning and equity in education. OECD Publishing. [CrossRef]

- OECD. (2024). PISA 2022 Results (Volume V): Learning strategies and attitudes for life. OECD Publishing. [CrossRef]

- Perry, L. B., Saatcioglu, A., & Mickelson, R. A. (2022). Does school SES matter less for high-performing students than for their lower-performing peers? A quantile regression analysis of PISA 2018 Australia. Large-Scale Assessments in Education, 10(1), 17. [CrossRef]

- Ramirez, G., Shaw, S. T., & Maloney, E. A. (2018). Math anxiety: Past research, promising interventions, and a new interpretation framework. Educational Psychologist, 53(3), 145–164. [CrossRef]

- Shimizu, Y. (2025). Relation between mathematics self-efficacy, mathematics anxiety, behavioural engagement, and mathematics achievement in Japan. Psychology International, 7(2), 36. [CrossRef]

- Takashiro, N. (2024). Educational inequality and low SES in Japan: A literature review. In The Palgrave Handbook of Global Social Problems (pp. 1–19). Springer International Publishing. [CrossRef]

- Van Ewijk, R., & Sleegers, P. (2010). The effect of peer socioeconomic status on student achievement: A meta-analysis. Educational Research Review, 5(2), 134–150. [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z., Hart, S. A., Kovas, Y., Lukowski, S., Soden, B., Thompson, L. A., Plomin, R., McLoughlin, G., Bartlett, C. W., Lyons, I. M., & Petrill, S. A. (2014). Who is afraid of math? Two sources of genetic variance for mathematical anxiety. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 55(9), 1056–1064. [CrossRef]

- Willms, J. D. (2010). School composition and contextual effects on student outcomes. Teachers College Record: The Voice of Scholarship in Education, 112(4), 1008–1037. [CrossRef]

- Zuo, S., Huang, Q., & Qi, C. (2024). The relationship between cognitive activation and mathematics achievement: Mediating roles of self-efficacy and mathematics anxiety. Current Psychology, 43(39), 30794–30805. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).