1. Introduction

Idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis (IPF) is a chronic and progressive fibrotic interstitial lung disease of unknown etiology, which primarily affects adults over 50 years of age. Histologically, it is characterized by the pattern of usual interstitial pneumonia, which leads to irreversible architectural distortion of the lung, decreased pulmonary compliance and impaired gas exchange [

1]. The hallmark clinical manifestations are exertional dyspnea and non-productive cough, which typically have an insidious onset and gradually worsen. The global incidence of IPF is estimated to be between 6.8 and 16.3 per 100,000 people per year, with a significantly higher prevalence in men than in women [

2]. The median survival after diagnosis is approximately three to five years, making IPF one of the most severe forms of interstitial lung diseases in terms of prognosis [

3]. Implicated risk factors include cigarette smoking, environmental exposures (e.g., metal and wood dust), gastroesophageal reflux, and genetic mutations involving telomere biology and surfactant proteins [

4]. Pathophysiologically, IPF is no longer considered to be primarily in inflammatory condition. Instead, it is thought to result from repeated micro-injuries to the alveolar epithelium in genetically predisposed individuals. These injuries trigger abnormal epithelial–mesenchymal interactions and the activation of fibroblasts and myofibroblasts. These cells then deposit extracellular matrix components, leading to lung fibrosis [

5]. This process is perpetuated by an altered wound-healing response and chronic fibrotic cycles involving minimal inflammation. Studies have also emphasized the role of AEC2 cell dysfunction, epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition and abnormal activation of developmental signaling pathways (e.g. Wnt/β-catenin and TGF-β) in disease progression [

3].

Pulmonary rehabilitation (PR) is a comprehensive intervention based on individualized assessment, incorporating exercise training, education and behavioral change. The aim is to improve the physical and psychological condition of people with chronic respiratory disease and to promote long-term adherence to health-enhancing behaviors [

6]. In IPF, PR has emerged as a critical adjunctive therapy to pharmacological treatment. Several clinical trials and meta-analyses have demonstrated that PR significantly improves functional exercise capacity, reduces breathlessness, and enhances health-related quality of life (QoL) in patients with IPF [

7]. The six-minute walk test (6MWT), a standard outcome measure, has shown meaningful improvements after PR, with average gains exceeding the minimal clinically important difference of 30 meters [

8]. Improvements in oxygen uptake, ventilatory efficiency, and heart rate recovery also reflect the physiological benefits of structured exercise training [

9]. Psychosocial benefits are equally important. Patients undergoing PR report reductions in depression and anxiety scores (HADS), improvements in fatigue, and better coping with the burden of disease [

10].

Moreover, high levels of outdoor activity have also been shown to improve survival rates in hypoxemic patients (e.g. those with COPD) [

11]. Maintaining physical activity after rehabilitation has also been associated with improved long-term survival in individuals with chronic respiratory diseases, including IPF [

12]. Despite these advantages, access to PR remains low due to geographical, logistical and institutional barriers. Tele-exercise rehabilitation schemes and home-based interventions can overcome these constraints, particularly for individuals in remote locations [

13]. Evidence suggests that distant interventions can produce effects equivalent to those of centre-based PR in terms of exercise tolerance and quality of life improvement, provided they are properly organised and supervised [

14]. Current guidelines published by the American Thoracic Society and the European Respiratory Society state that chronic respiratory disease patients must be referred for face-to-face or tele-pulmonary rehabilitation, regardless of disease severity, as it is an integral part of care [

15].

This study aims to evaluate the effect of a supervised, structured tele-exercise rehabilitation program on patients with IPF. Due to the progressive nature of the disease and the limited pharmacological treatment options available, it is crucial to maximize exercise capacity, physical function, and quality of life to ensure daily functioning and independence. Although conventional pulmonary rehabilitation has been reported to be highly beneficial for patients with IPF, there is a lack of robust evidence supporting the efficacy of tele-rehabilitation or home-based exercise programs for this patient group. Although some initial studies have demonstrated the potential of such interventions and their short-term outcomes, there are currently no standardized protocols or information on long-term results [

7]. This emphasizes the urgent need to investigate the effective, safe and reliable delivery of tele-exercise in actual clinical settings. To address this challenge, we have developed a visionary pilot program incorporating tele-exercise rehabilitation protocols to mitigate the shortcomings and clinical needs of IPF patients. This pilot study aims to investigate the program’s impact on several clinical outcomes. The main endpoints are an increase in anaerobic capacity and ratings on validated quality-of-life scales. Secondary endpoints include dyspnea severity, arterial oxygen saturation, and mental well-being. This study's value lies in its potential to provide the evidence needed to justify the inclusion of tele-exercise rehabilitation in IPF clinical practice.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants

This prospective, interventional, single-arm trial was designed to evaluate the effectiveness of a home-based tele-exercise rehabilitation program in IPF patients. Eight weeks was the study duration, consisting of four weeks of supervised tele-exercise rehabilitation and four weeks of detraining (no exercise treatment). A priori estimation of sample size was done using G*Power software (version 3.1.9.7, Düsseldorf, Germany) to check if there would be sufficient statistical power to detect differences between the subjects at the three measurement points. This was against a re-peated-measures analysis of variance (ANOVA) model with one group and three measures (pre, post-intervention and post-detraining). As a result of the presence of a moderate effect size (f = 0.30), a significance level of 0.05 and statistical power (1 − β) of 0.80, the minimum sample size needed was found to be 12 participants. This was calculated with a moderate correlation of 0.5 between repeated measures while accounting for non-sphericity correction. Thirteen participants were deemed to be sufficient to detect clinically significant differences in the main outcomes with low risk of type II error. Ethical approval was provided by the University of Thessaly Institutional Ethics Committee (514/6-11-2023) and written informed consent was provided by all the study participants as per the Helsinki Declaration and personal data as per the European Parliament and Council of the European Union [

16].

2.2. Inclusion Criteria

Participants were eligible for inclusion in the study if they were aged between 50 and 80 years, had a confirmed diagnosis of IPF based on high-resolution computed tomography and a multidisciplinary clinical evaluation, and met the criteria set out in the international diagnostic guidelines [

1]. All participants were clinically stable, with no exacerbations or hospitalizations in the previous six weeks. All participants had to be able to walk independently (with or without assistive devices) and have no contraindications to cardiopulmonary exercise testing [

17], and without the presence of severe resting hypoxemia (SpO₂ <85%). They also had to have access to new technologies and the internet [

18]. Participants were also excluded if they had recently participated in a structured exercise or rehabilitation program in the last three months. All participants had to provide written medical approval from their attending physician to participate.

2.3. Measurements

The anthropometric characteristics and body mass of all participants were recorded, and the body surface area (BSA)

and body mass index (BMI)

The six-minute walk test (6MWT) was used to assess functional capacity [

19]. Specific measurements included: i) oxygen saturation (SpO₂, Nonin 9590 Onyx Vantage, USA) and heart rate (HR, chest belt with Bluetooth and ANT+ technology) at baseline and at one-minute intervals during the test and during the first minute of recovery [

20]; (ii) cardiopulmonary parameters (Cosmed Quark CPET, Italy), blood pressure (Mac, Japan), and Borg scales (dyspnea and leg fatigue, CR-10), which were recorded before, immediately after, and during the first minute of recovery following the 6MWT [

2][]. We calculated the mean arterial blood pressure (MAP, mmHg)

, the oxygen breath

, breathing reserve (

, and the pulse respiration quotient

[

22,

23,

24].

Prior to the 6MWT, all participants performed a handgrip strength test using an electronic dynamometer (Camry EH101, South El Monte, CA, USA), as previously described [

25] and, prior to the physical fitness tests, all subjects completed the 36-item Short Form Survey Instrument to assess self-reported health-related quality of life (SF-36) [

26], as well as a self-rating questionnaire to measure anxiety and depression (HADS) [

27].

2.4. Intervention Program

The intervention consisted of a structured tele-exercise pulmonary rehabilitation program delivered via secure video conferencing software. Developed and implemented with the scientific and technical support of the USTEP Team (

www.ustep.gr), it was designed to be feasible at home and require non-specific equipment. The aim was to promote long-term behavioral engagement with physical activity. Supervised remotely, this personalized program took place three days per week, and each 30–40 minute exercise session comprised a combination of aerobic training (approximately 40% of each session: stationary walking at a moderate intensity, reaching 40–60% of the maximal heart rate at the end of the 6MWT and/or a Borg dyspnea rating of 4–6 out of 10) and resistance exercises (approximately 30% of each session: Strengthening exercises using bodyweight, focusing on major muscle groups, with an intensity RPE scale rating of 11–15 out of 20, and breathing techniques exercise (approximately 30% of each session: diaphragmatic exercises to support ventilatory control). Safety protocols included self-monitoring of SpO₂ and HR before, during, and after sessions. Weekly video consultations allowed the training load to be adjusted, adherence to be reinforced, and symptoms to be documented. All sessions were led by exercise specialists who were certified to work with clinical populations and overseen by a clinical exercise physiologist.

2.5. Statistical Analysis

Normality of the data was tested by the Shapiro–Wilk test. Data is presented as percentage for qualitative variables, mean (M) ± standard deviation (SD) for parametric variables, and median with 25

th and 75

th percentiles for non-parametric variables. Because the design of the study was three time-points of repeated measurements (baseline, post 4 weeks of tele-exercise training and post 4-week detraining) in a single group, Friedman test was used to compare differences over time. In those variables where statistically significant Friedman test results were seen, pairwise comparisons with the Wilcoxon signed-rank test were performed with the Bonferroni adjustment for multiple tests on significance values. In addition, Cohen's d was also calculated to estimate the effect size of within-subject change through the formula:

Kendall's W was used to record the effect size for the Friedman test and 0.1, 0.3 and 0.5 were used to represent small, moderate and large effects, respectively. It was computed with the formula: , where S is the sum of squared deviations of ranks, k is the number of conditions and n is the number of subjects. For parametric data, the 95% confidence intervals (95% CI) for the mean were calculated to reflect the precision of the estimates according to the formula: CI95% = CI95% = ± t (α/2,df) ⋅, where represents the sample mean, SD is the standard deviation, n is the number of samples, and t(α/2, df) represents the critical value of the Student's t-distribution. All statistical analyses were conducted using the IBM SPSS 21 statistical software package (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA), and statistical significance was set at p < 0.05.

3. Results

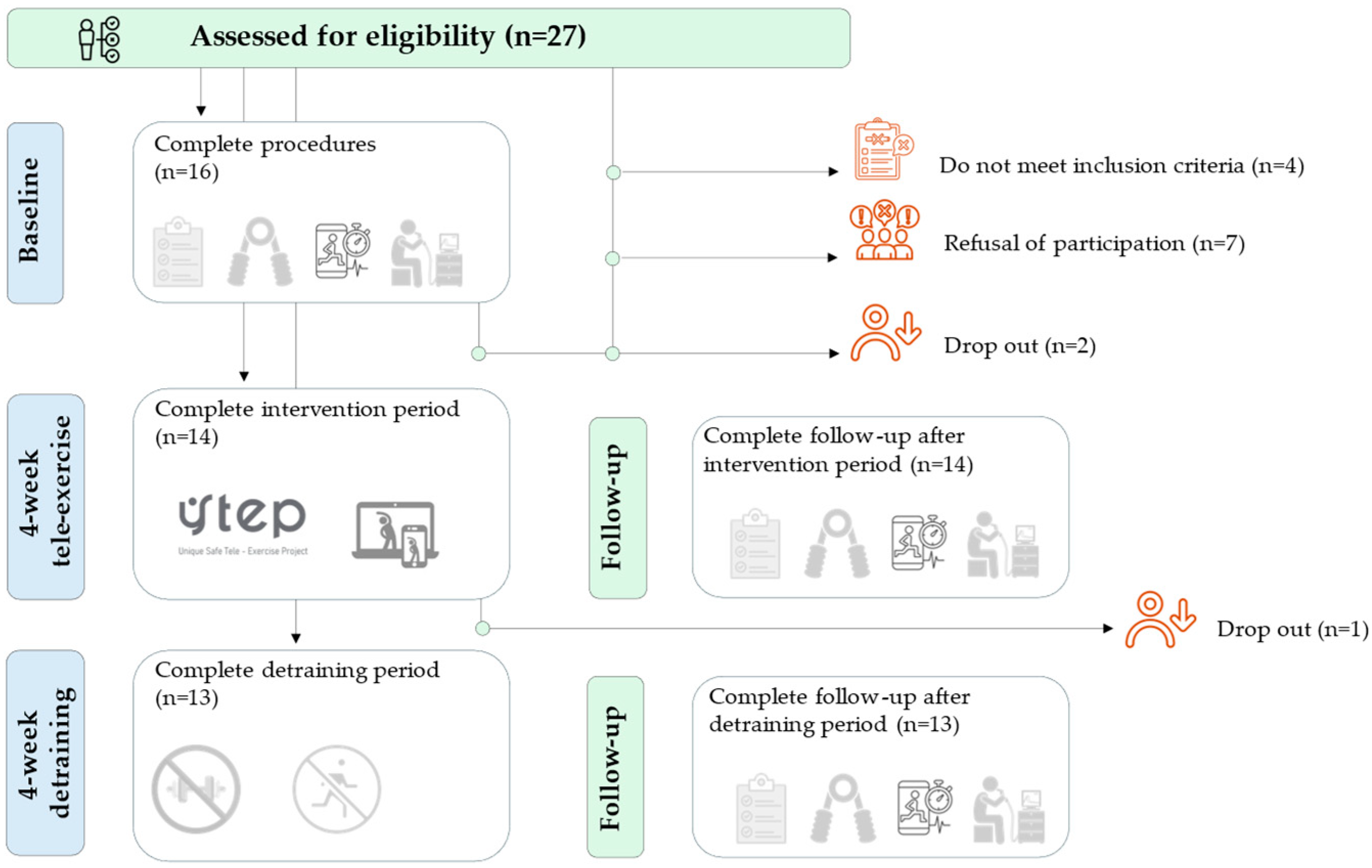

Thirteen of the 27 individuals assessed for eligibility were included in the study (

Figure 1). Program adherence was 92%, as recorded by connection and weekly attendance. All participants responded to each video and reported no problems with adherence to the program.

Table 1 shows the changes in anthropometric and morphologic characteristics before and after the four-week intervention period and subsequent four-week detraining period. The results for quality of life across the three timepoints are presented in

Table 2. The results of the cardio-pulmonary-metabolic-hemodynamic parameters are presented in

Table 3.

Table 4 presents the correlation results between physical fitness parameters, anxiety – depression and quality of life.

The HADS score revealed statistically significant differences at the three time points (χ²(2) = 8.38, p = 0.015), with a medium effect size of 0.35. (Baseline: M = 12.9 ± 2.4, 95% CI [11.5, 14.4]; after the intervention program: M = 12.5 ± 1.9, 95% CI [11.3, 13.6] and after the detraining period: M = 12.6 ± 2.2, 95% CI [11.3, 13.9]). However, pairwise comparisons did not reveal any statistically significant differences between the three timepoints (p > 0.05) following Bonferroni adjustment. Cohen's d was 0.70 for baseline-to-post-intervention program comparisons and 0.64 for baseline-to-detraining-period comparisons, indicating a moderate effect size. A small effect size was observed in the comparison between the post-intervention program and detraining periods (d = –0.41).

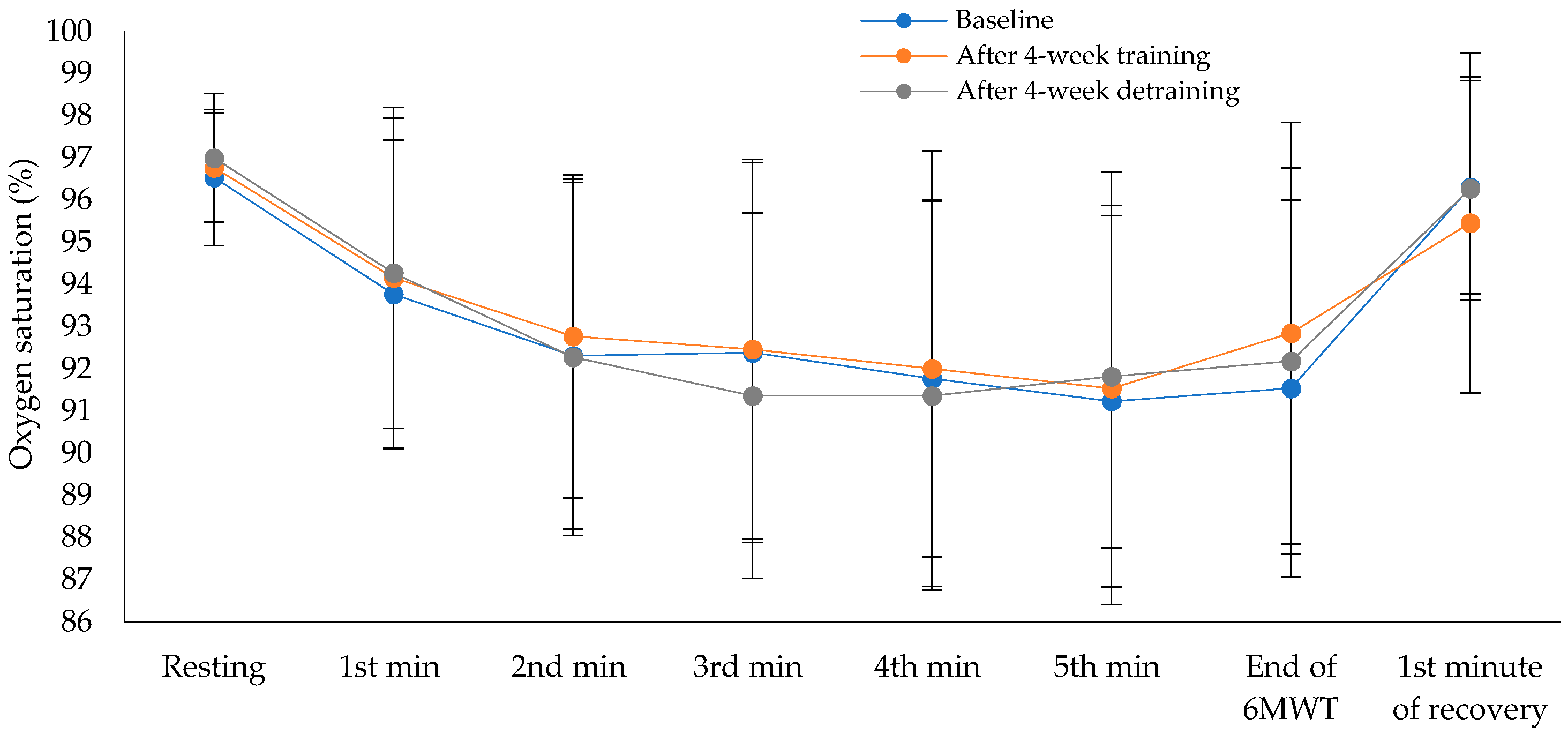

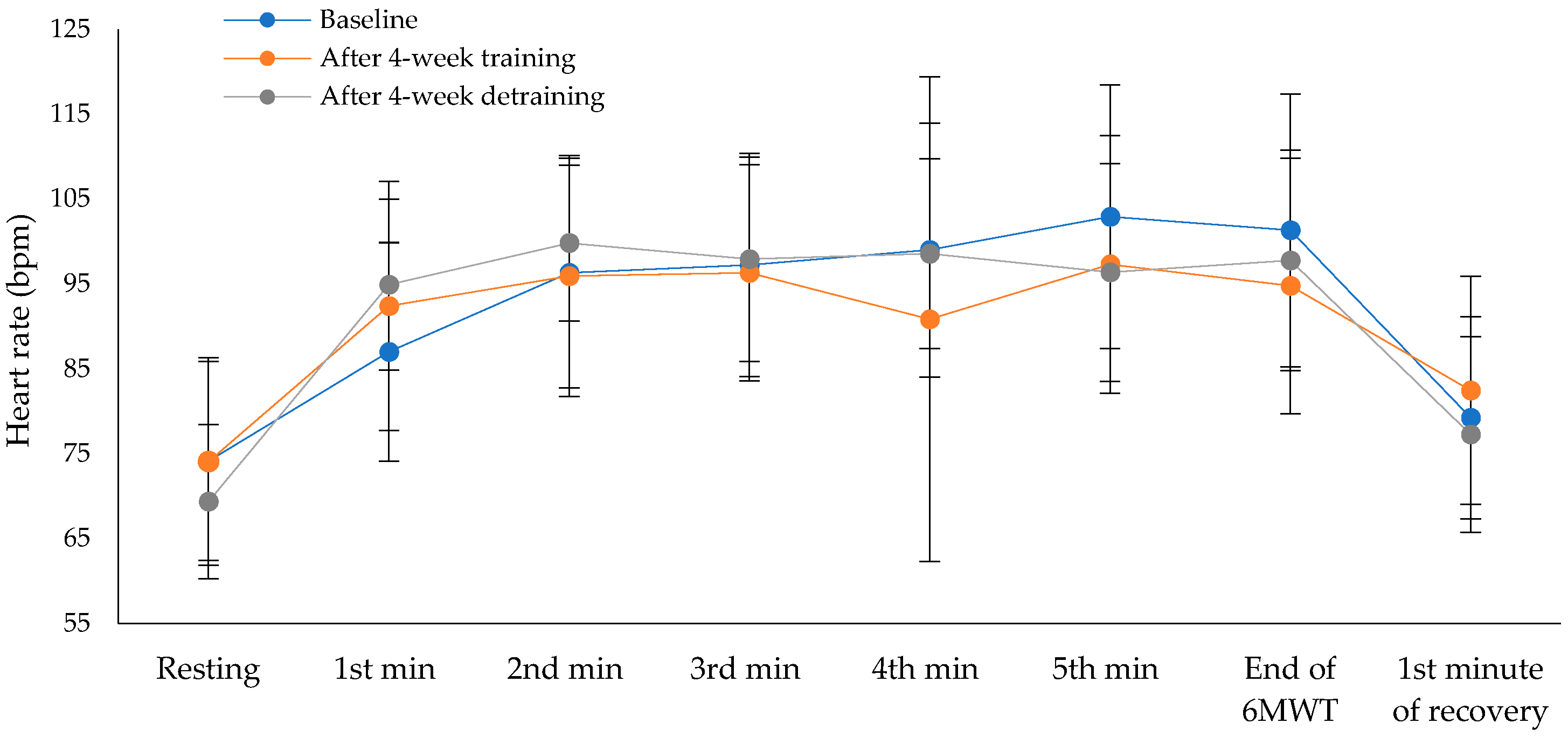

Exercise capacity showed statistically significant difference across the three time points (χ²(2) = 12.13, p = 0.002), with a moderate to large effect size of 0.47 (Baseline: M = 520.8 ± 84.8 m, 95% CI [469.6, 572.0]; after the intervention program: M = 564.6 ± 101.6 m, 95% CI [503.2, 626.0]; after the detraining period: M = 530.0 ± 111.4 m, 95% CI [462.7, 597.3]). Pairwise comparisons revealed statistically significant differences between baseline and after the intervention program (p = 0.004), and between after the intervention program and after the detraining period (p = 0.056), while no significant difference was observed between baseline and after the detraining period (p = 1.00), after applying Bonferroni correction. Cohen’s d for paired comparisons showed a large effect between baseline and after the intervention program (d = –1.15), a moderate effect between after the intervention program and the detraining period (d = 0.80), and a small effect between baseline and detraining period (d = –0.19). The percentage of predicted values in the 6MWT also differed significantly over time (χ²(2) = 9.18, p = 0.010), with a moderate effect size of 0.35 (Baseline: M = 111.2 ± 18.3%, 95% CI [100.1, 122.3]; after the intervention program: M = 119.9 ± 17.1%, 95% CI [109.6, 130.2]; after the detraining period: M = 112.5 ± 21.1%, 95% CI [99.7, 125.3]). Pairwise comparisons revealed statistically significant differences between baseline and after 4-week training (p = 0.004), and between after the intervention program and after the detraining period (p = 0.056), while no significant difference was observed between baseline and after 4-week detraining (p = 1.00), after applying Bonferroni correction. Cohen’s d showed a moderate effect between baseline and post-intervention (d = –0.50), a moderate effect between post-intervention program and detraining period (d = 0.63), and a small effect between baseline and detraining period (d = –0.14). There were no statistically significant differences in oxygen saturation (

Figure 2) or heart rate (

Figure 3) across the three time points during the 6MWT. There were no statistically significant differences in dyspnea across the three time points at the end of the 6MWT (χ²(2) = 3.50, p = 0.174, Baseline: M = 0.73 ± 1.27, 95% CI [-0.13, 1.58]; after the intervention program: M = 0.27 ± 0.90, 95% CI [-0.33, 0.88]; and after the detraining period: M = 0.09 ± 0.30, 95% CI [–0.11, 0.29]). There were also no significant differences in leg fatigue (χ²(2) = 0.80, p = 0.670, Baseline: M = 0.45 ± 1.21, 95% CI [–0.36, 1.27]; after the intervention program: M = 0.55 ± 1.21, 95% CI [–0.27, 1.36]; and after the detraining period: M = 0.36 ± 0.92, 95% CI [–0.26, 0.98]).

The handgrip strength test revealed no statistically significant differences between the three time points (χ²(2) = 4.32, p = 0.115), with a small effect size of 0.17 (Baseline: M = 29.9 ± 7.9, 95% CI [25.6, 34.2]; after the intervention program: M = 29.9 ± 8.5, 95% CI [25.3, 34.5]; after the detraining period: M = 29.4 ± 8.2, 95% CI [25.0, 33.9]).

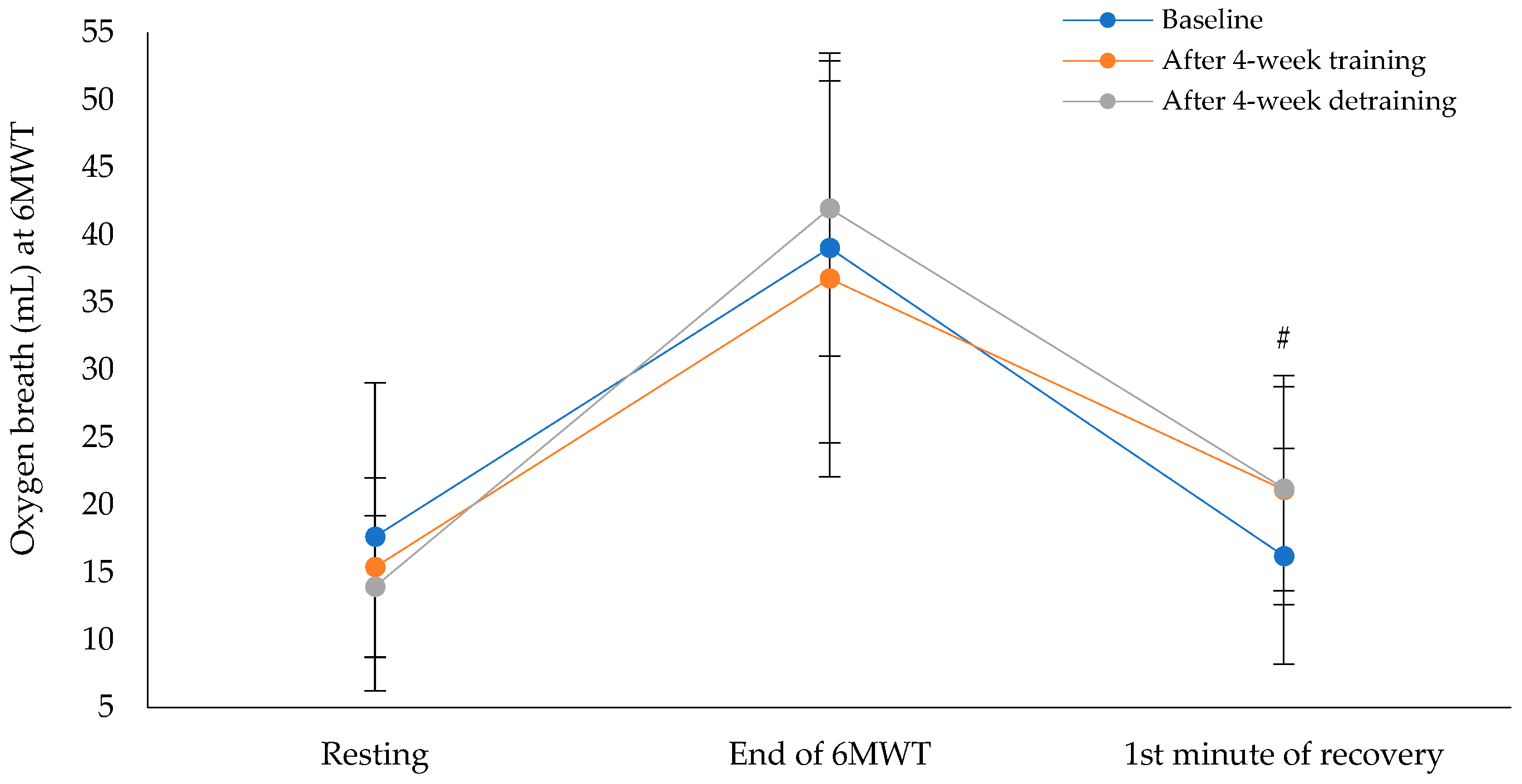

Figure 4 shows that the oxygen breath at the first minute of recovery after the 6MWT showed a statistically significant difference across the three time points (χ²(2) = 6.17, p = 0.046), with a moderate effect size of 0.29 (Baseline: M = 16.3 ± 7.9, 95% CI [12.0, 20.6], and after the intervention program: M = 21.1 ± 8.6, 95% CI [16.4, 25.7]; after the detraining period: M = 21.2 ± 7.5, 95% CI [17.1, 25.3]). Pairwise comparisons, after applying Bonferroni correction, revealed no statistically significant differences between baseline and after the intervention program (p = 0.148), between baseline and after the detraining period (p = 0.144), or between after the intervention program and after the detraining period (p = 1.000). Cohen's d for the paired comparisons showed moderate effects: between baseline and post-intervention (d = −0.49), between post-intervention and detraining (d = −0.03), and between baseline and detraining (d = −0.58).

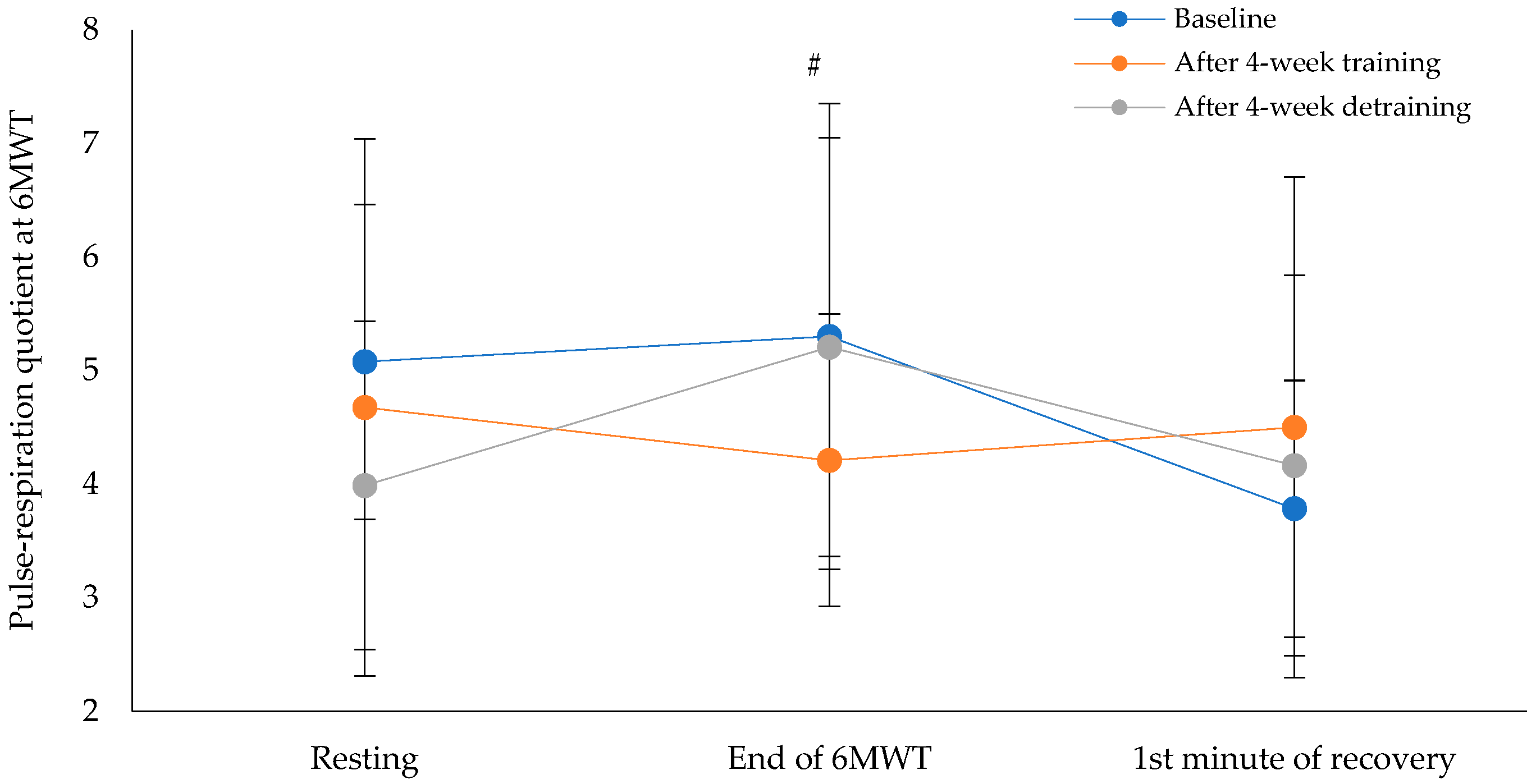

Figure 5 shows the pulse-respiration quotient at the end of the 6MWT. This parameter showed a statistically significant difference across the three time points (χ²(2) = 8.60, p = 0.014), with a moderate effect size of 0.31 (Baseline: M = 5.2 ± 2.2, 95% CI [4.1, 6.4], the intervention program: M = 4.2 ± 1.3, 95% CI [3.4, 4.9] and after the detraining period: M = 5.3 ± 1.8, 95% CI [4.3, 6.3]). Pairwise comparisons revealed no statistically significant differences between baseline and the intervention program (p = 0.041, Bonferroni-adjusted p = 0.122) or between baseline and after the detraining period (p = 0.905, Bonferroni-adjusted p = 1.000). However, a statistically significant difference was found between the intervention program and detraining period (p = 0.007, Bonferroni-adjusted p = 0.022). Cohen's d for paired comparisons showed a moderate effect size between baseline and post-intervention (d = 0.61), a negligible effect size between baseline and detraining (d = −0.04), and a large effect size between post-intervention and detraining (d = −1.08).

4. Discussion

To our knowledge, this is the first study to investigate any differences physical fitness, quality of life and anxiety and depression in patients with IPF after four weeks of tele-exercise rehabilitation program and four weeks of detraining. Our findings showed different adjustments between the three timepoints in physical fitness (χ²(2) = 12.13, p = 0.002), quality of life score (χ²(2) = 11.79, p = 0.003) and anxiety and depression score (χ²(2) = 8.38, p = 0.015).

Our results showed that 4-week tele-exercise rehabilitation program improved the as recorded distance covered 6MWT. On average, the patients in our study had a maximal oxygen uptake of 45.2 ± 13.0% of the predicted value at three timepoints, a ventilatory ratio to maximal ventilation volume of approximately 27%, and a SpO₂ nadir of 6.0 ± 3.6% during the 6MWT. In people with IPF, gas exchange is greatly inhibited because of the changes to the alveolar-capillary membrane. The thickening and fibrosis of the interstitium impacts the diffusion of oxygen from the alveoli into pulmonary capillaries, resulting in reduced diffusing capacity [

28]. This restriction is most pronounced during physical activity when there is an increase in demand for oxygen, but the damaged membrane is unable to provide sufficient support. Consequently, patients often experience exertional hypoxemia with increased alveolar-arterial oxygen gradient (A–a PO₂) and diminished hypoxemia. Moreover, ventilation-perfusion (V̇A/Q̇) mismatch caused by fibrotic regions that are poorly ventilated but adequately perfused stagnates the already present hypoxemia [

28]. These impairments result in insufficient arterial oxygenation, causing severe shortness of breath during low-intensity exertion and intolerance to physical activity or exercise of any kind. Our results showed no significant changes in the dyspnoea response at any of the three timepoints after the 6MWT. The frequent hypoxia status in IPF patients due to ventilation-perfusion (V̇A/Q̇) mismatch, causes increase in on tissue-level oxidative metabolism and the supply of oxygen in the circulation, the shift to dominant-energy pathways via an-aerobic metabolism is delayed, while ventilatory response amplified metabolic demands and stress. Our results showed no significant changes in hemodynamic parameters at any of the three timepoints. Moreover, due to frequent hypoxia and inactivity status, structural limitations are observed. According to Bueno et al. [

29], mitochondrial dysfunction plays a pivotal role in both disease progression and exercise intolerance in IPF. Repeated epithelial injury and chronic oxidative stress impair mitochondrial homeostasis in alveolar type II cells and skeletal muscle fibers [

29]. This dysfunction is characterized by altered mitochondrial biogenesis, reduced ATP production, increased reactive oxygen species generation, and impaired mitophagy [

30]. In skeletal muscle, mitochondrial inefficiency compromises aerobic energy production, contributing to early onset of muscular fatigue, decreased oxygen utilization, and increased lactate accumulation during physical activity [

12]. This peripheral limitation amplifies the sensation of dyspnea and further limits exercise tolerance [

31]. Systematic exercise training has been shown to reduce the perception of dyspnea in patients with chronic respiratory disease. A previous study has shown that the desensitization of central neural networks involved in dyspnea perception, such as the insular cortex, anterior cingulate cortex and limbic system [

32] affected by repeated exposure to controlled exertional stress (e.g. exercise) desensitizes the afferent signaling pathways from respiratory mechanoreceptors and chemoreceptors, resulting in a reduced central response to a given level of ventilatory effort. In addition, exercise increases skeletal muscle oxidative capacity and mitochondrial efficiency, delaying the onset of peripheral muscle fatigue [

33], increase resistance to peripheral muscle fatigue, and reduced accumulation of metabolic by-products such as lactate acid and therefore less afferent input to the brainstem and dyspnea centers [

34].

As reported by Stavrou et al. [

21], physical exercise enhances functional capacity during submaximal effort and improves autonomic regulation. These benefits are closely tied to mechanisms involving the respiratory metaboreflex. Strengthening the respiratory muscles through training can raise the activation threshold of this reflex, mitigating key limiting factors such as dyspnea and peripheral fatigue. This, in turn, improves physical performance. Furthermore, exercise-induced adaptations influence autonomic reflex pathways, particularly those involving baroreceptors and chemoreceptors. This aligns with the concept of competitive resource distribution between the diaphragm and locomotor muscles, such as the quadriceps. In the current study, the intervention period consisted of four weeks of training three days per week, with each session lasting approximately 35 minutes and involving submaximal interval exercise. Our results showed a relationship between HADS scores and performance, quality of life subdomains, and cardiorespiratory parameters and performance. However, the positive effects observed during the intervention period diminished or became negative during the detraining period (see

Table 4).

Our findings also revealed temporal variations in oxygen breath efficiency, as well as in the PRQ, at the three testing points. Oxygen breath measurement is an indicator of respiratory adequacy and represents the metabolic return of individual breaths. In patients with IPF, tidal volume is a significant parameter that tends to adjust as a compensatory phenomenon to provide adequate ventilation. These adjustments most likely reflect systemic changes in breathing patterns designed to maximize endurance during physical exertion. Failure to make appropriate alterations to these mechanisms during exercise may lead to impaired performance. Systematic breathing therapy in IPF patients, particularly when combined with exercise training, has been associated with increased vagal tone, resulting in more stable autonomic regulation. Enhanced parasympathetic drive improves respiratory efficiency and oxygenation, which can minimize symptoms such as breathlessness and optimize respiratory mechanics during exertion. Patients therefore experience increased ease of breathing and greater exercise tolerance [

35]. Additionally, the PRQ is an overall index of cardiopulmonary synchrony that has been correlated with physiological conditions such as anxiety, respiratory illness and cardiovascular insufficiency. As PRQ indexes the effect of vagal activity, it provides insight into the balance of autonomic activity in these systems. In IPF patients, exercise can improve vagus nerve function by increasing parasympathetic output to enhance vagal tone. This supports the idea of a more universal interaction between autonomic function and respiratory dynamics via vagally mediated respiratory rhythms [

35]. Furthermore, breathing patterns play a key role in controlling cardiac vagal activity, as the respiratory control system is influenced by both voluntary and automatic breathing commands. Variables such as respiratory cycle duration and heart rate variability influence this integration [

21]. Finally, vagus nerve stimulation through slow, deep breathing has been demonstrated to alleviate anxiety and augment vagal outflow, prompting physiological and psychobiological responses that bolster parasympathetic dominance [

36].

4.1. Limitations and Strengths

One of the greatest strengths of the present study is that, to our knowledge, it is the first study to examine the impact of an organized, home-based tele-exercise program on cardiopulmonary and autonomic indices in patients with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis (IPF). The study's prospective design, combined with the use of objective physiological parameters such as the pulse-respiration quotient and oxygen breath, makes the findings new and clinically relevant. The addition of a detraining phase also provides evidence regarding the persistence of short-term, exercise-related adaptations. Furthermore, the use of validated tools to assess fatigue, dyspnea, anxiety and functional capacity enhances the methodological rigour of the assessment. However, this study has some limitations. The limited sample size and the absence of a control group restrict statistical power and generalizability. The short duration of the training and detraining periods themselves cannot span the full scope of changes in physiological or behavioral status over time. Additionally, all participants were clinically stable and technologically knowledgeable, which represents a limitation of selection bias. While there was improvement in fatigue and some functional parameters, others did not improve, potentially due to the limited duration or participant baseline stability.

5. Conclusions

Tele-exercise appears to be a highly promising, patient-centered and convenient approach for patients with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis (IPF). This study demonstrates that even brief remote training sessions can improve fatigue and functional status, suggesting that tele-exercise could be integrated into daily pulmonary management. As a cost-effective and scalable alternative to conventional rehabilitation, tele-exercise offers valuable opportunities to improve access to care and ensure its continuity for IPF patients, particularly those with mobility limitations, geographic limitations, and/or infection risk.

Author Contributions

V.T.S. conceived the idea and designed the study. Z.D and E.K. performed patient recruitment. V.T.S., K.K. and G.T. performed data collection. V.T.S. and G.T. designed the tele-exercise rehabilitation program. V.T.S. contributed to data analysis. V.T.S. contributed to drafting and editing the paper. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Institutional Review Board/Ethics Committee of the Medical School of the University of Thessaly (514/6-11-2023).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available from the corresponding author upon request. The data are not publicly available for privacy reasons.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to express their sincere appreciation to the patients who participated in this study for their invaluable cooperation. They would also like to thank the USTEP company for their invaluable assistance in developing the tele exercise rehabilitation programs and supporting the project.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Raghu G, Collard HR, Egan JJ, Martinez FJ, Behr J, Brown KK, Colby TV, Cordier JF, Flaherty KR, Lasky JA, Lynch DA, Ryu JH, Swigris JJ, Wells AU, Ancochea J, Bouros D, Carvalho C, Costabel U, Ebina M, Hansell DM, Johkoh T, Kim DS, King TE Jr, Kondoh Y, Myers J, Müller NL, Nicholson AG, Richeldi L, Selman M, Dudden RF, Griss BS, Protzko SL, Schünemann HJ; ATS/ERS/JRS/ALAT Committee on Idiopathic Pulmonary Fibrosis. An official ATS/ERS/JRS/ALAT statement: idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis: evidence-based guidelines for diagnosis and management. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2011, 183, 788–824.

- Sankari A, Chapman K, Ullah S. Idiopathic Pulmonary Fibrosis. 2024 Apr 23. In: StatPearls. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2025.

- Richeldi L, Collard HR, Jones MG. Idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Lancet 2017, 389, 1941–1952.

- Barratt SL, Creamer A, Hayton C, Chaudhuri N. Idiopathic Pulmonary Fibrosis (IPF): An Overview. J Clin Med. 2018, 7, 201.

- King TE Jr, Bradford WZ, Castro-Bernardini S, et al. A phase 3 trial of pirfenidone in patients with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. N Engl J Med. 2014, 370, 2083–2092.

- Spruit MA, Singh SJ, Garvey C, ZuWallack R, Nici L, Rochester C, Hill K, Holland AE, Lareau SC, Man WD, Pitta F, Sewell L, Raskin J, Bourbeau J, Crouch R, Franssen FM, Casaburi R, Vercoulen JH, Vogiatzis I, Gosselink R, Clini EM, Effing TW, Maltais F, van der Palen J, Troosters T, Janssen DJ, Collins E, Garcia-Aymerich J, Brooks D, Fahy BF, Puhan MA, Hoogendoorn M, Garrod R, Schols AM, Carlin B, Benzo R, Meek P, Morgan M, Rutten-van Mölken MP, Ries AL, Make B, Goldstein RS, Dowson CA, Brozek JL, Donner CF, Wouters EF; ATS/ERS Task Force on Pulmonary Rehabilitation. An official American Thoracic Society/European Respiratory Society statement: key concepts and advances in pulmonary rehabilitation. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2013, 188, e13–e64.

- Cox IA, Borchers Arriagada N, de Graaff B, Corte TJ, Glaspole I, Lartey S, Walters EH, Palmer AJ. Health-related quality of life of patients with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur Respir Rev 2020, 29, 200154.

- Gloeckl R, Teschler S, Jarosch I, Christle JW, Hitzl W, Kenn K. Comparison of two- and six-minute walk tests in detecting oxygen desaturation in patients with severe chronic obstructive pulmonary disease - A randomized crossover trial. Chron Respir Dis 2016, 13, 256–263.

- Vainshelboim, B. Exercise training in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis: is it of benefit? Breathe (Sheff) 2016, 12, 130–138. [Google Scholar]

- Edwards GD, Polgar O, Patel S, Barker RE, Walsh JA, Harvey J, Man WD, Nolan CM. Mood disorder in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis: response to pulmonary rehabilitation. ERJ Open Res 2023, 9, 00585-2022.

- Ringbaek TJ, Lange P. Outdoor activity and performance status as predictors of survival in hypoxaemic chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD). Clin Rehabil 2005, 19, 331–338.

- Vainshelboim B, Kramer MR, Izhakian S, Lima RM, Oliveira J. Physical activity and exertional desaturation are associated with mortality in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. J Clin Med 2016, 5, 73.

- Stavrou VT, Vavougios GD, Astara K, Mysiris DS, Tsirimona G, Papayianni E, Boutlas S, Daniil Z, Hadjigeorgiou G, Bargiotas P, Gourgoulianis KI. The Impact of Different Exercise Modes in Fitness and Cognitive Indicators: Hybrid versus Tele-Exercise in Patients with Long Post-COVID-19 Syndrome. Brain Sci. 2024, 14, 693.

- Zamparelli SS, Lombardi C, Candia C, Iovine PR, Rea G, Vitacca M, Ambrosino P, Bocchino M, Maniscalco M. The Beneficial Impact of Pulmonary Rehabilitation in Idiopathic Pulmonary Fibrosis: A Review of the Current Literature. J Clin Med 2024, 13, 2026.

- Holland AE, Cox NS, Houchen-Wolloff L, Rochester CL, Garvey C, ZuWallack R, Nici L, Limberg T, Lareau SC, Yawn BP, Galwicki M, Troosters T, Steiner M, Casaburi R, Clini E, Goldstein RS, Singh SJ. Defining Modern Pulmonary Rehabilitation. An Official American Thoracic Society Workshop Report. Ann Am Thorac Soc. 2021, 18, e12–e29.

- Resneck, J.S. Revisions to the Declaration of Helsinki on Its 60th Anniversary: A Modernized Set of Ethical Principles to Promote and Ensure Respect for Participants in a Rapidly Innovating Medical Research Ecosystem. JAMA 2025, 333, 15–17. [Google Scholar]

- Razvi Y, Ladie DE. Cardiopulmonary Exercise Testing. 2023. In: StatPearls. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2025.

- Stavrou VT, Astara K, Ioannidis P, Vavougios GD, Daniil Z, Gourgoulianis KI. Tele-Exercise in Non-Hospitalized versus Hospitalized Post-COVID-19 Patients. Sports (Basel) 2022, 10, 179.

- ATS Committee on Proficiency Standards for Clinical Pulmonary Function Laboratories. ATS statement: Guidelines for the six-minute walk test. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2002, 166, 111–117.

- Stavrou, V.T.; Vavougios, G.D.; Astara, K.; Siachpazidou, D.I.; Papayianni, E.; Gourgoulianis, K.I. The 6-minute walk test and anthropometric characteristics as assessment tools in patients with Obstructive Sleep Apnea Syndrome. A preliminary report during the pandemic. J. Pers. Med. 2021, 11, 563. [Google Scholar]

- Stavrou VT, Vavougyios GD, Tsirimona G, Boutlas S, Santo M, Hadjigeorgiou G, Bargiotas P, Gourgoulianis KI. The Effects of 4-Week Respiratory Muscle Training on Cardiopulmonary Parameters and Cognitive Function in Male Patients with OSA. Applied Sciences 2025, 15, 2532.

- DeMers, D.; Wachs, D. Physiology, Mean Arterial Pressure. In StatPearls; StatPearls Publishing: Treasure Island, FL, USA, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Stavrou, V.T.; Karetsi, E.; Gourgoulianis, K.I. The Effect of Growth and Body Surface Area on Cardiopulmonary Exercise Testing: A Cohort Study in Preadolescent Female Swimmers. Children 2023, 10, 1608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scholkmann, F.; Wolf, U. The Pulse-Respiration Quotient: A Powerful but Untapped Parameter for Modern Studies About Human Physiology and Pathophysiology. Front. Physiol. 2019, 10, 371. [Google Scholar]

- Stavrou V., Vavougios G.D., Bardaka F., Karetsi E., Daniil Z., Gourgoulianis K.I., 'The effect of exercise training on the quality of sleep in national-level adolescent finswimmers'. Sports Med. Open 2015, 5, 34.

- Pappa E, Kontodimopoulos N, Niakas D. Validating and norming of the Greek SF-36 Health Survey. Qual Life Res. 2005, 14, 1433–1438.

- Michopoulos I, Douzenis A, Kalkavoura C, Christodoulou C, Michalopoulou P, Kalemi G, Fineti K, Patapis P, Protopapas K, Lykouras L. Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS): validation in a Greek general hospital sample. Ann Gen Psychiatry 2008, 7, 4.

- Plantier L, Cazes A, Dinh-Xuan AT, Bancal C, Marchand-Adam S, Crestani B. Physiology of the lung in idiopathic pulmo-nary fibrosis. Eur Respir Rev 2018, 27, 170062.

- Bueno M, Calyeca J, Rojas M, Mora AL. Mitochondria dysfunction and metabolic reprogramming as drivers of idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Redox Biol 2020, 33, 101509.

- Kinnula VL, Myllärniemi M. Oxidant-antioxidant imbalance as a potential contributor to the progression of human pulmonary fibrosis. Antioxid Redox Signal 2008, 10, 727–738.

- Stendardi L, Grazzini M, Gigliotti F, Lotti P, Scano G. Dyspnea and leg effort during exercise. Respir Med 2005, 99, 933–942.

- Herigstad M, Hayen A, Evans E, Hardinge FM, Davies RJ, Wiech K, Pattinson KTS. Dyspnea-related cues engage the prefrontal cortex: evidence from functional brain imaging in COPD. Chest 2015, 148, 953–961.

- Maltais F, Simard AA, Simard C, Jobin J, Desgagnés P, LeBlanc P. Oxidative capacity of the skeletal muscle and lactic acid kinetics during exercise in normal subjects and in patients with COPD. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 1996, 153, 288–293.

- Amann M, Romer LM, Subudhi AW, Pegelow DF, Dempsey JA. Severity of arterial hypoxaemia affects the relative contributions of peripheral muscle fatigue to exercise performance in healthy humans. J Physiol 2007, 581 (Pt 1), 389–403.

- Kadura, S. , Purkayastha, S., Benditt, J., Anand, A., Collins, B., De Quadros, M., Hobson, M., Biswas, M. J., Ho, L., Spino, C., & Raghu, G. (2025). Yoga Effect on Quality-of-Life Study Among Patients with Idiopathic Pulmonary Fibrosis (YES-IPF) [Preprint]. medRxiv. [CrossRef]

- Magnon, V.; Dutheil, F.; Vallet, G.T. Benefits from one session of deep and slow breathing on vagal tone and anxiety in young and older adults. Sci. Rep 2021, 11, 19267. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).