1. Introduction

In daily family life, a teenager interacts with his parents in various dyadic, triadic, and polyadic relational configurations: with the mother only, with the father only, with one parent in the presence of the other parent, with both parents at the same time, or simply witnessing a discussion between the parents. Amongst these various relational configurations, researchers have first focused on the mother–child dyad, before broadening their focus onto the father-child dyad, mutual influences between family dyads, coparenting (i.e., the coordination and teamwork between two adults regarding childrearing), and polyadic family relationships [

1]. Family-level processes, i.e., processes involving both parents and the child(ren), have shown to represent a level of analysis of its own right in the complex study of family processes, and to predict unique proportions of variance in children’s and adolescents’ psychological outcomes as compared to parenting-related variables [

2,

3,

4].

Observation of families “in action” has shown to be a useful method for assessing the quality of family relationships [

5]. When looking at the existing observational tools to assess family-level processes during family interactions, coding systems focus on various aspects of family functioning, such as family competence or cohesion [

6,

7]. Nevertheless, these tools entail two main issues. First, they are not designed for the assessment of many of the relational configurations that can be found in daily family life, such as when a parent and a teen discuss in the presence of the other parent. However, including these configurations might inform researchers about the organization and hierarchy in family systems [

1,

8]. Second, the tasks and coding systems generally focus on coparenting in families with younger children [

9] and do not specifically allow the assessment of coparenting in families with adolescents, although it has been found to be relevant to characterize family-level relationships and predict various developmental outcomes in adolescents [

10].

The family alliance (FA) model provides a theoretical framework that has been developed to study triadic family interactions with infants, including all possible relational configurations and the coparenting relationship. FA can be defined as the coordination between family members when they perform a joint activity such as playing, sharing a meal, or discussing [

1,

11,

12]. FA assessment is based on a macroanalysis of several verbal and non-verbal cues, such as postures, gaze orientation, interferences, turn-taking, adaptiveness of child stimulation, and mutual smiles [

13]. Historically, triadic interactions have been systematically evaluated in the laboratory with the Lausanne Trilogue Play (LTP), a standardized observational situation where two parents are asked to play with their infant following a four-part scenario, with each part reflecting one of the four relational configurations that are possible within a triad: First, one parent is asked to play with the child, while the other parent is asked to remain “simply present”; parents switch roles; all three family members play together; and finally, parents discuss while the child is left on her own for a little while. The assessment distinguishes three types of FA: cooperative, conflicted, and disordered. Cooperative FA refers to family interactions in which all family members coordinate and share positive affects. Conflicted FA refers to family interactions in which a coparenting or marital conflict overtly or covertly prevents the triad from sharing a genuine moment of quality. Disordered FA refers to family interactions where (self-)exclusion prevails, which typically prevents the triad from coordinating and sharing positive affects. Most importantly, the latter two types of FA have been found to predict increased rates of psycho-functional disorders in infants, toddlers, and preschoolers and are thus considered as “problematic” [

14,

15]. In a longitudinal study, the evolution pattern of FA in early childhood was also found to predict the level of social cognition skills of 15-year-old adolescents [

3].

Although the FA model has been developed for early family interactions, it has also been used in an exploratory way for assessing families with adolescents in both clinical and research contexts. The LTP situation has been used as a diagnostic and therapeutic tool in family therapy, and links between the quality of family interactions during the LTP situation have been associated with adolescent psychopathology [

16]. Nonetheless, despite numerous preliminary studies using the LTP situation for families with adolescents, FA assessment has yet to be properly validated in the context of families with adolescents.

For the assessment of FA in adolescence, we decided to use a conflict discussion task [

17] instead of a cooperative task for the assessment of FA in infancy and childhood. Indeed, family conflict might serve as a suitable process for evaluating the observed quality of family relationships. On the one hand, it is a central family-level process in adolescence [

18] and a normative mechanism of change as adolescents grow toward autonomy [

19]. On the other hand, when conflicts are intense and frequent or when conflict management is steeped in hostility (i.e., destructive instead of constructive conflict) [

20], it might be linked to potentially harmful effects on adolescent adjustment and health [

21]. This rationale led us to design the Lausanne Trilogue Play – Conflict Discussion Task (LTP–CDT), an observational situation that aims to elicit conflict interactions and negotiation in the mother–father–adolescent triad.

To assess interactions occurring during the LTP–CDT, we developed the Family Conflict and Alliance Assessment Scales – with adolescents (FCAAS) [

22]. The FCAAS is a macro-analytical observational coding system based on the Family Alliance Assessment Scales (FAAS) [

13], the validated instrument used to assess the quality of FA in infancy. However, we needed to adapt the FAAS for obvious reasons. First, family interactions with adolescents may differ from those with infants in terms of the child’s contribution to the interaction, since adolescents may be more verbally active (i.e., they can use language), which can lead them to interact in ways other than infants, including being defensive, critical, or sarcastic. Second, as both tasks differ (play vs discussion), they will elicit different behaviors. For example, assessing cooperation during a play might be based on coordination of attention or actions, whereas assessing coordination during a discussion might be based on verbal cues. In addition to these adaptations linked to the targeted age and the nature of the task, the literature in the fields of adolescent development and parent–adolescent communication was screened to find constructs and scales that could be relevant for the assessment of the quality of family interactions during a triadic conflict discussion task. Several FCAAS scales were inspired by this literature and adapted to meet the complexity of triadic family interaction patterns.

In the present study, we introduce the Lausanne Trilogue Play – Conflict Discussion Task (LTP–CDT) and the Family Conflict and Alliance Assessment Scales – with adolescents (FCAAS). Our hypothesis is that the LTP–CDT will elicit typical interactions (i.e., representative of interactions outside the laboratory) that are relevant to assess family functioning, and that the FCAAS scales will show good psychometric indices of reliability (i.e., inter-rater reliability) and validity (i.e., construct and criterion validity). This study aims to validate and showcase this new research tool for assessing families with adolescents.

2. Materials and Methods

Sample characteristics

A sample of N = 87 non-referred mother–father–adolescent triads was recruited in 2022 from the general population in the area of Lausanne, Switzerland. Flyers were posted in the medical offices of pediatricians and general practitioners, and on the hospital’s website. The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and with the Swiss Federal Human Research Ordinance (HRO), and approved by the Cantonal Commission on Ethics in Human Research of the State of Vaud (CER-VD; Project n. 2021-01859, 2021/10/25). Inclusion criteria were as follows: families had to have adolescents aged between 10 and 13 years and to be fluent in French (the language of the questionnaires). Families were included only if none of the members had a known psychopathological diagnosis. Five families out of the initial 87 were excluded because of missing observational data. The final sample of adolescents was n = 33 girls and n = 49 boys with a mean age of 12.04 years (SD = .94). Mothers’ ages ranged from 34 to 60 years with a mean age of 44.04 years (SD = 4.21). Fathers’ ages ranged from 33 to 59 years with a mean age of 45.99 years (SD = 4.97). None of the families were in the lower socioeconomic class, 3.7% were in the lower-middle class, 9.8% were in the middle class, 17.1% were in the upper-middle class, and 69.5% were in the upper class. Parents were separated in four families and divorced in one family (this triad was measured with the stepfather). The adolescent was a single child in 12.2% of cases, and there were 30.5% of youngest, 11.0% of middle, and 46.3% of eldest children. All family interactions were in French, except for two in English and one in Spanish. These three families were fluent in French and could complete the questionnaires; however, they were asked to discuss in their usual language so that interactions would be as typical as possible.

Procedure

Families visited the laboratory after having given their written consent. Family interactions were filmed during the Lausanne Trilogue Play – Conflict Discussion Task (LTP–CDT). Directly after the interaction, each family member was given a paper-and-pencil questionnaire to assess their perception of the typicality of the interaction. In the following two weeks, each parent and the adolescents were asked to complete online questionnaires using the REDCap electronic data capture tools [

23].

The LTP–CDT procedure is a standardized observational situation that can occur in the laboratory or at home. The three family members are seated on chairs, each positioned approximately 120 cm from the other two chairs (measured from the center of one chair to the center of the other), to create an equilateral interactive triangle. This arrangement serves 1) to place family members relatively close to each other and encourage dialog, and 2) to ensure that they are equidistant from each other.

The instructions occur in three parts. First, instructions are given to select the “hottest” topic of conflict within the family. The experimenter mentions several potential subjects and explains that the family can select a conflict occurring between the teenager and one parent, between the teenager and both parents, between the parents about the teenager’s education, or between all three family members. Second, the rest of the instructions are given regarding the four-part scenario of the LTP–CDT (i.e., one parent discusses with the adolescent while the other parent remains simply present, then parents switch roles, then parents discuss together while adolescent remains simply present, and all three discuss together). Finally, family members are given the opportunity to ask any questions they might have. Once the family is ready, the experimenter leaves the room and gives an audio signal from the control room to indicate the start of the family interaction as well as the transitions to the next part of the LTP–CDT scenario. Each part of this scenario lasts for exactly 3 min. Detailed instructions given to LTP–CDT’s participants can be found in

Supplementary File S1.

In this validation study, interactions were filmed using two cameras positioned opposite each other. The order of the first two LTP–CDT parts was randomized and counterbalanced, meaning that half of the families started with the mother–adolescent (+father) configuration, while the remaining families started with the father–adolescent (+mother) configuration. Regarding the selected conflictual subjects, families in our study discussed the following: screen time and use (n = 24), school and homework (n = 13), relationship with siblings and parental management of conflicts between siblings (mostly parental unfairness; n = 11), compliance with the rules and setting of new rules (n = 10), parent–adolescent relationship regarding communication and conflict (n = 9), storage and cleaning at home (n = 7), and other (n = 9).

Measures

Family Conflict and Alliance Assessment Scales – with adolescents (FCAAS)

The FCAAS comprises 10 scales: Postures & gazes, turn-taking, mutual respect for coparenting roles, conflict resolution, affective climate, mentalization, role reversal, coparenting support, autonomy promotion, and adolescent autonomy. They are summarized in

Table 1, and a more thorough description can be found in

Supplementary File S2.

The first author used the FCAAS to assess the quality of family interactions in the complete sample. To test for inter-rater reliability, a second coder (third author) was trained for 8 hours by the first author and independently coded a random selection of families (n = 28, 34.15% of the sample).

Relationship Assessment Scale

The Relationship Assessment Scale (RAS) [

24] is a 7-item questionnaire that assesses the degree of marital satisfaction in a romantic relationship. It has been adapted and validated in French [

25]. It includes questions such as “How well does your partner meet your needs?” or “In general, how satisfied are you with your relationship?” Each item is rated on a 5-point Likert scale with scores ranging from 1 (low satisfaction) to 5 (high satisfaction). A total score is obtained by computing the sum of the items, with a higher score indicating higher marital satisfaction. Both parents filled in the RAS separately (Cronbach’s α = .81 for mothers and α = .75 for fathers). A positive correlation was expected, with higher scores of marital satisfaction being linked with higher scores on the FCAAS instrument.

Coparenting Inventory for Parents and Adolescents

The Coparenting Inventory for Parents and Adolescents (CIPA) [

26,

27] is a self-report questionnaire that assesses coparenting based on 25 items ranging along three dimensions (cooperation, conflict, and triangulation), each measured with three different targets (mothers’ and fathers’ contribution to coparenting, as well as coparenting in the parental dyad). Agreement with the affirmations ranged from 0 (not at all true) to 4 (completely true), and a mean score was computed for each dimension. High scores corresponded to a high presence of the given phenomenon, i.e., high cooperation or high conflict. To maintain parsimony in the models, we decided to only perform analyses on the target of the parental dyad (leaving aside the specific contribution of each parent). Each dimension at the dyadic level consisted of 4 items, with a total of 12 items for the three dimensions (mothers: Cronbach’s α = .84 for cooperation, α = .68 for conflict, α = .74 for triangulation; fathers: α = .63 for cooperation, α = .67 for conflict, α = .66 for triangulation). Each parent answered the questions separately. We expected the FCAAS instrument to correlate positively with coparenting cooperation, and negatively with coparenting conflict and triangulation.

Typicality questionnaire

To assess the ecological validity of family interactions during the LTP–CDT, we operationalized ecological validity in terms of typicality, that is, the extent to which each member of the triad assesses the situation and the behaviors of all partners as representative of everyday life [

28]. We adapted the questionnaire from Favez et al. [

28] for use with the LTP–CDT and we developed a comparable but shorter adolescent version. The questionnaire was completed by each family member after the end of the LTP–CDT. For parents, the questionnaire comprised 13 five-point Likert items, with answers ranging from 1 (not at all or never) to 5 (completely or always). The first item focused on parents’ general perception of typicality compared with daily interactions in the family. The remaining 12 items focused on the extent to which each family member behaved in a “normal” way during each of the four parts of the LTP–CDT scenario. For adolescents, the questionnaire comprised four five-point Likert items similar to those of the parents, except that the normality of behaviors was assessed only for the interaction as a whole and not regarding each part of the LTP–CDT scenario. An average typicality score was computed for each family member. We expected that interactions would be representative of everyday interactions [

28].

Statistical analyses

First, we computed a set of descriptive statistics and bivariate correlations for all study variables. Second, inter-rater reliability was investigated according to the recommendations of Ten-Hove and colleagues [

29] to estimate intraclass correlation coefficients (ICCs) in a way that allows for variance due to differing numbers of raters per subject, (i.e., incomplete or unbalanced designs). Using the absolute agreement between raters to test for inter-rater reliability, we calculated the ICCs (A, khat) [

29] and variance terms with maximum likelihood estimation (MLE). Here and for all analyses, average ratings were used for double-coded family interactions and single ratings of the first author were used for the remaining family interactions. Third, we used confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) to assess the factor structure of the scale within a structural equation modelling (SEM) framework. On the basis of on the unidimensionality of the FA model in infancy [

13], we started with the assumption that this would also be the case for families with adolescents. Because the results of this first CFA model (see “construct validity” in the “results” section) were unsatisfactory, we used modification indices (MI) to refine our model and test an alternative model with two factors (FA and coparenting). Fourth, we assessed the links between the FCAAS and a set of control variables using the two-factor structure of the FCAAS. The selected control variables were age and gender of the adolescent, family socioeconomic status, family situation (parents together vs not together), the conflictual subject chosen for the LTP–CDT, and the scenario of the LTP–CDT (which parent starts in the first part of the LTP–CDT). Because the conflictual subject chosen for the LTP–CDT is a nominal variable, we tested whether there were differences regarding the FCAAS scores with one-way ANOVAs (one for each factor of the FCAAS). Fifth, we assessed the criterion validity of the FCAAS by investigating the links between fathers’ and mothers’ marital satisfaction (RAS scores) and the two-factor structure of the FCAAS. Mothers’ and fathers’ RAS scores were added as covariates in the two-factor CFA model of the FCAAS, with freely estimated covariance paths between the FCAAS factors and the RAS scores, as well as between both parents’ RAS scores. Then, similar to the fifth step, we used the two-factor model and investigated the links between fathers’ and mothers’ perceptions of coparenting (CIPA scores) and the factor structure of the FCAAS, with the aim of assessing the construct validity of the FCAAS. The six CIPA scores were added as covariates in the FCAAS two-factor CFA model. The model was specified with freely estimated covariances between all these variables, including the covariances between all included variables of the CIPA. Finally, we assessed the reported typicality of family interactions during the LTP–CDT. Mean scores were computed for the perceptions of each family member, and internal consistency was assessed using Cronbach’s alpha.

Descriptive statistics and bivariate correlations were performed with IBM SPSS 29, whereas inter-rater reliability indices were calculated in R using the scripts made available by Ten-Hove and colleagues [

29] on the Open Science Framework (

https://osf.io/8j26u/). Mplus (version 8.9) was used for confirmatory factor analyses [

30]. To assess the fit of the SEM models, we used the chi-square test, confirmatory fit index (CFI), Tucker-Lewis index (TLI), root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA), and standardized root mean squared residual (SRMR). Indicators for good-fitting models are a non-significant chi-square, a CFI and TLI above .95 for excellent fit (at least above .90 for acceptable fit), an RMSEA below .06 (at least below .08 for acceptable fit), and an SRMR below .08 [

31]. Modification indices are considered significant above the 3.84 threshold and when indices of the fully standardized expected parameter change (stdYX EPC) are above the cutoff criterion of .20 [

32]. We handled the missing data with pairwise correction.

3. Results

Descriptive statistics and bivariate correlations

Descriptive statistics and bivariate correlations between all study variables are presented in

Supplementary Table S3.

Inter-rater reliability

The results of inter-rater reliability are presented in

Table 2. Reliability was excellent for the scales “Conflict resolution” and “Role reversal” (ICCs = .90), good for the scales “Turn-taking”, “Mutual respect for coparenting roles”, “Affective climate”, “Mentalization”, “Coparenting support”, “Autonomy promotion”, and “Adolescent autonomy” (ICCs > .81), and lower but still in the moderately acceptable range for the scale “Postures & gazes” (ICC = .64).

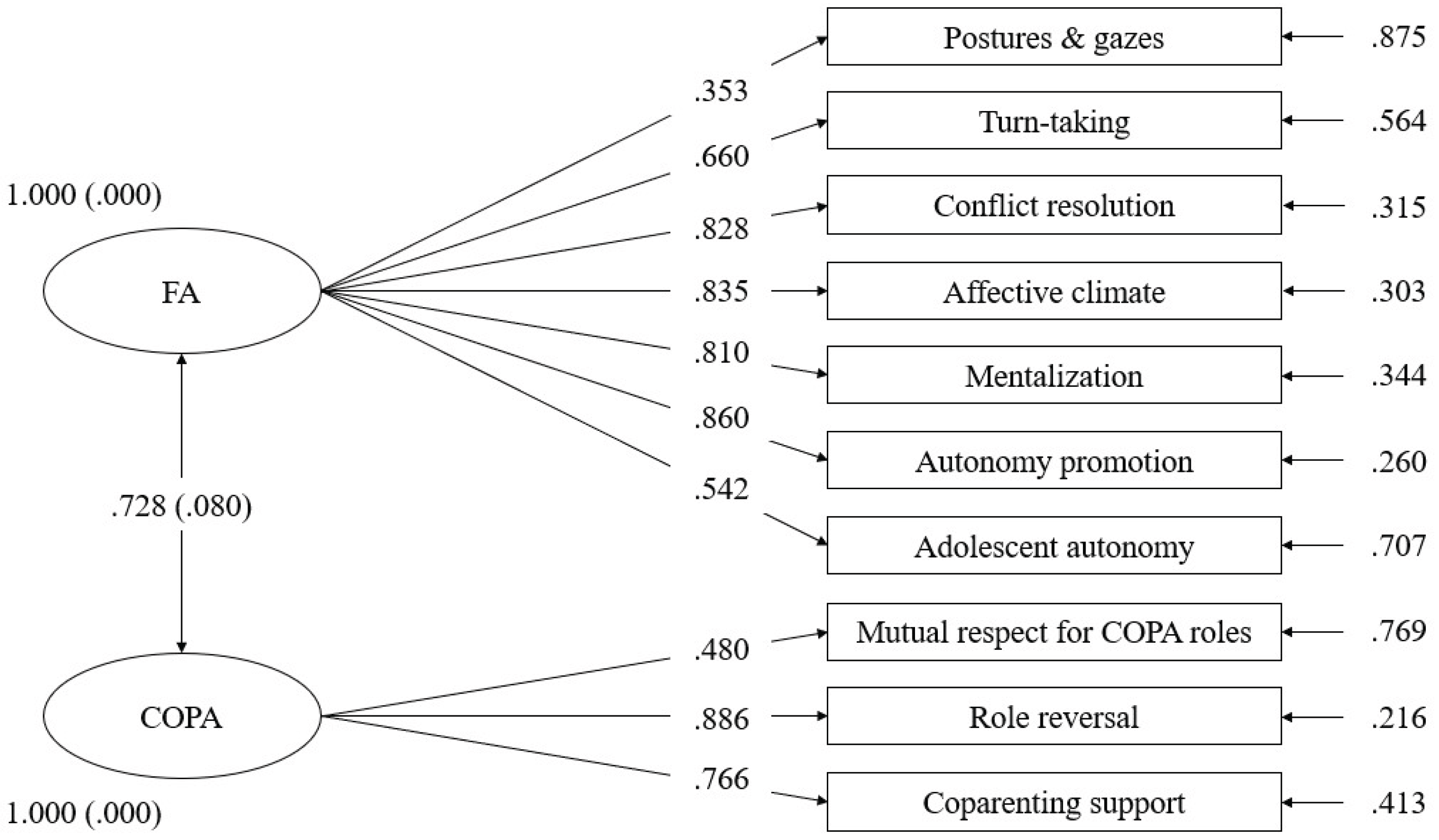

Factor structure validity

The results of the CFA for the one-factor model indicated only a moderate adjustment of the model to the data: Chi-square (χ

2) = 79.866, degrees of freedom (df) = 35,

p < .001, CFI = .873, TLI = .837, SRMR = .083, RMSEA = .125, 90% CI [.089, .161]. MI requested on this one-factor model indicated that there could be a significant fit improvement if covariances were added on the residuals of the scales “Mutual respect for coparenting roles” and “Role reversal” (MI = 16.799; fully standardized expected parameter change (stdYX EPC) = .486), as well as on the residuals of the scales “Role reversal” and “Coparenting support” (MI = 13.233; stdYX EPC = .450). These results suggested that the three scales “Mutual respect for coparenting roles”, “Role reversal”, and “Coparenting support”, might constitute a separate factor, which made sense from a theoretical point of view, since these three scales all relate to the concept of coparenting. Coparenting is a construct that is theoretically close to—albeit distinct from—FA because it refers to the cooperation, coordination, and support between both parents in the education of children [

13]. From an assessment perspective, observed coparenting refers to coordinated behaviors and mutual support shown by the parents toward the child(ren) during mother–father–child(ren) interactions, whereas FA refers to the coordination of all family members involved in the interactions. Since the suggestions of the modification indices made much theoretical sense, we ran a two-factor model with one FA factor (using the following scales as indicators: “Postures & gazes”, “Turn-taking”, “Conflict resolution”, “Affective climate”, “Mentalization”, “Autonomy promotion”, and “Adolescent autonomy”), and one coparenting factor (using the following scales as indicators: “Mutual Respect for coparenting roles”, “Role reversal”, and “coparenting support”). This model showed a better adjustment to the data: χ

2 = 54.806, df = 34,

p = .013, CFI = .941, TLI = .922, SRMR = .078, RMSEA = .086, 90% CI [.040, .127]. The CFI and TLI values indicated an adequate (albeit not excellent) fit, while the SRMR value indicated a good fit. In contrast, the chi-square test was significant, and the RMSEA value was slightly above the cutoff for acceptable fit. This last result might be due to our small sample size [

31,

33]. Considering its theoretical relevance and its adequate fit on average, the two-factor model was deemed satisfactory. As shown in

Figure 1, the factor loadings ranged from .353 to .860 for the FA factor and from .480 to .886 for the coparenting factor, with all standardized estimates being significant (all p-values < .002). The estimation of the correlation between the two factors was high,

r = .73,

p < .001). Given these results, we computed total scores for the FA and coparenting dimensions, which both showed good internal consistency (respectively α = .87 and α = .75).

Control variables

The results of the estimation of the model showed a poor fit (χ2 = 111.483, df = 74, p = .003, CFI = .903, TLI = .876, SRMR = .084, RMSEA = .079, 90% CI [.046, .107]), as only the CFI and RMSEA indices were acceptable. Such a poor fit makes sense given that the correlations of all control variables with the FA and the coparenting factors ranged from -.077 to .214 and were not significant, except for the correlation regarding the FA factor and adolescent gender (r = .27, p = .011; higher means on the FA factor in families with boys) and the correlation regarding the coparenting factor and family situation (r = -.21, p = .027; higher means on the coparenting factor in families in which parents are together compared to the one in which parents are separated or divorced). Regarding the conflictual subject discussed during the LTP-CDT, scores at the FA factor significantly differed, F(6,75) = 2.61, p = .023, and so did the scores at the coparenting factor, F(6,75) = 2.91, p = .012. Post hoc tests (Bonferroni) showed that FA scores were significantly lower (p = .010) when families discussed the parent–adolescent relationship (M = 19.39, SD = 5.36) than when they discussed the relationship with siblings and parental management of conflicts between siblings (M = 28.91, SD = 4.39). In addition, coparenting scores were significantly lower when families discussed the parent-adolescent relationship (M = 8.83, SD = 3.02) than when they discussed the sibling relationship (M = 12.73, SD = 1.69), p = .049, or the subject of school and homework (M = 13.04, SD = 2.15), p = .015.

Criterion validity: Marital satisfaction

The results of the estimation of the model showed an acceptable fit (χ2 = 75.659, df = 50, p = .011, CFI = .933, TLI = .912, SRMR = .071, RMSEA = .078, 90% CI [.038, .112]). Although the chi-square test was significant, the CFI, TLI, SRMR, and RMSEA values were still in the acceptable range. In this model, the FA factor significantly correlated with fathers’ RAS scores (r = .34, p = .002), whereas it did not significantly correlate with mothers’ RAS scores (r = .18, p = .103). The coparenting factor correlated significantly with fathers’ RAS scores (r = .33, p = .003), and with mothers’ RAS scores (r = .36, p = .015). Mothers’ and fathers’ marital satisfaction correlated positively and significantly (r = .31, p = .009).

Construct validity: Coparenting

Estimation of the model revealed an acceptable fit (χ2 = 117.099, df = 82, p = .007, CFI = .939, TLI = .911, SRMR = .065, RMSEA = .070, 90% CI [.038, .098]). Although the chi-square test was significant, the CFI, TLI, SRMR, and RMSEA values were acceptable. In this model, the FA factor significantly correlated with fathers’ perceptions of coparenting cooperation (r = .39, p = .001), conflict (r = -.29, p = .010), and triangulation (r = -.34, p = .005), and with mothers’ perceptions of coparenting cooperation (r = .34, p = .001), conflict (r = -.34, p = .002), and triangulation (r = -.27, p = .036). The coparenting factor significantly correlated with perceptions of coparenting cooperation by fathers (r = .49, p < .001) and mothers (r = .40, p = .002). It also correlated significantly with fathers’ and mothers’ perceptions of coparenting conflict (r = -.28, p = .027; r = -.28, p = .019, respectively) and triangulation (r = -.36, p = .009; r = -.47, p < .001, respectively).

Ecological validity

Internal consistency was low for the adolescent mean score (Cronbach’s α = .66), but excellent for the parental mean score (Cronbach’s α = .92 for mothers and α = .90 for fathers). Scores ranged between 1 and 5, with a relatively high mean (mothers: M = 3.92, SD = .76; fathers: M = 4.00, SD = .71; adolescents: M = 3.92, SD = .78).

4. Discussion

This paper presents a new procedure that combines an observational situation, the LTP–CDT, and its coding system, the FCAAS. This procedure extends the FA model from early childhood to adolescence and allows researchers in the field of family psychology to assess the quality of interactions in mother–father–adolescent triads. The description of the assessment and rating procedures was followed by a study that provided convincing evidence for the reliability and validity of the FCAAS, as well as for the ecological validity of the LTP–CDT.

First, this validation study achieved inter-rater reliability for the rating scales, which was good to excellent for nine of ten rating scales. This result supports the high reliability of the FCAAS instrument, especially since we used a strict criterion (absolute agreement between raters) to assess it. Regarding the scale “Postures & Gazes”, the reliability was in the moderate range, which indicates that clarification of criteria and specification of coding rules might be required. Future studies may indicate whether this scale is meaningful and potentially more reliable with additional training. Should the opposite occur, it might be eliminated from the coding system to improve its precision and time consumption.

Second, the results of the CFA showed that the factor structure of the FCAAS seemed to comprise two factors referred to as “Family Alliance” and “coparenting”. This result was surprising at first, given that theory and available data on family triads with infants have pointed to the one-dimensionality of FA- and coparenting-related behavioral indicators in the FAAS [

13]. One explanation for this differentiation could be that coparenting-related and family processes are independent because they exist at two different hierarchical levels, with the family pertaining to the system level and coparenting to the subsystem level [

34]. Another explanation for the differentiation between FA and coparenting might be that an adolescent child is much more autonomous and active than a baby in social interaction. Therefore, the parental dyad might progressively differentiate itself from whole-family functioning as the family transitions from childhood to adolescence. Indeed, family functioning might shift from a “mother–father–child” configuration in early childhood to a “mother–father + adolescent” configuration in adolescence.

Third, total scores on the FA and coparenting dimensions were not related to adolescent age, family socioeconomic status, or the scenario of the LTP–CDT, whereas they were related to adolescent gender, family situation, or the conflictual subject of the LTP–CDT. Regarding adolescent gender, there was a surprising effect according to which families with boys scored higher on the FA factor. We imagine that such an effect might stem from differences in parenting and coparenting according to the child’s gender [

10], and therefore, future research should most certainly include this control variable in analyses. Regarding family situation, scores at the coparenting factor were lower in families in which the parents were divorced or separated, which seems logical given the links between marital and coparenting functioning [

35]. Regarding the subject that was selected for the LTP–CDT, families discussing the parent–adolescent relationship displayed lower FA or coparenting scores than when discussing other subjects. Such differences can be explained by the fact that some conflictual subjects may be more concrete or easier to solve than others. In addition, the family’s subject selection (i.e., the type, difficulty, or intensity of conflict) might thus be indicative of the quality of family relationships.

Fourth, the two-factor structure of the FCAAS showed adequate criterion validity, as several significant associations between the FCAAS factors and marital satisfaction appeared. For the coparenting factor of the FCAAS, better observed functioning of the coparenting relationship was related to higher marital satisfaction for both parents, which is in line with the literature [

35]. For the FA factor of the FCAAS, better-quality family interactions were related to fathers’ higher marital satisfaction, whereas there were no significant associations with mothers’ marital satisfaction. This gender difference might suggest that while marital satisfaction and coparenting might be inseparable for both fathers and mothers, marital satisfaction and the quality of family relationships might be more disconnected in mothers than in fathers. Moreover, gender differences in marital satisfaction might be absent or small in terms of quantity (i.e., level of satisfaction) but exist in terms of quality. Indeed, husbands and wives might differ regarding their reasons behind marital (in)satisfaction or regarding the links with other variables within or outside the couple and the family [

36].

Fifth, the two-factor structure of the FCAAS showed adequate construct validity, which was tested using a self-report measure of coparenting. Indeed, FA and observed coparenting scores correlated significantly with all scores of fathers’ and mothers’ perceptions of coparenting. All correlations between FA or observed coparenting scores and reported coparenting went in the expected direction, meaning that better scores on our observational rating scales were related to better scores in coparenting cooperation, or lower scores in coparenting conflict or triangulation. These results show that the FCAAS instrument has good construct validity, and that lower scores on the instrument might indicate actual difficulties in the coparenting relationship.

Sixth, participants reported that family interactions performed during the LTP-CDT were highly typical, which supports the ecological validity of this new observational situation. The LTP-CDT seems to be prone to generate behaviors in the laboratory that are representative of daily behaviors in the family. This is in line with the fact that patterns of communication in families with adolescents have been repeated for many years, which makes interactional patterns, behaviors, and attitudes very instinctive and hard to control. Additionally, the fact that the conflict to solve was chosen by the family probably added to the impression of the family members that they were in a real-life discussion. Therefore, our results indicate that family interactions during the LTP–CDT may not be sensitive to social desirability.

There were several limitations to this study. The first limitation was the small sample size although it was still acceptable for this type of research. We aim to compensate in the future with further investigations on new samples of families. The second limitation is the high homogeneity of our sample, given that two-thirds of the families were in the upper-middle or upper socioeconomic class and less than 15% of the families belonged to lower classes. The third limitation of our validation study is that our sample was limited to preadolescents (aged between 10 and 13). However, the age of adolescents in our sample was not linked to the scores on the FCAAS scales (see analyses of the control variables), which suggests that the use of the LTP–CDT and the FCAAS might be extended to adolescents older than 13 years. Future studies should confirm our results for the entire adolescent developmental period. The last limitation is that the coefficients of internal reliability for some CIPA scores were at the lowest values in the acceptability range, i.e., slightly below .70. Therefore, although they showed strong associations with other study variables that were consistent with what could be expected, results including these CIPA scores should be interpreted with caution. Based on these few limitations, the next stage in this line of research would be to test the LTP–CDT and FCAAS in larger samples and with populations different from the sample in this study, such as families with older adolescents, low-income families, or families with a referred member. Such endeavors may also allow testing for the known-group validity of the FCAAS. In addition, the LTP–CDT and FCAAS could be tested in families with same-sex parents so that our assessment tool may be considered more generally, as targeting parent–parent–adolescent interactions (instead of only mother–father–adolescent interactions).

Finally, a topic of future research might be the use of the LTP–CDT and FCAAS in the clinical setting. Potentially, our task and coding system could provide clinicians with a standardized way to assess communication problems that could be worked upon to improve the quality of family relationships and ultimately the adolescent prognosis. For instance, the LTP–CDT could be used at the beginning and end of family therapy and thus provide a measure of the evolution of the family. Importantly, the use of this instrument with referred families may require several adaptations. For instance, the clinician might want to moderate the instruction concerning the selection of the “hottest” topic for the LTP–CDT but might instead suggest a recurring topic based on prior therapeutic sessions with the family. We would nevertheless strongly recommend against the use of the LTP–CDT with families where there is a risk of violence. Also, another potential use of the LTP–CDT and FCAAS might be to use it as an intervention tool by providing video-feedback to the family, i.e., watching the video-recorded family interaction with the family and discussing meaningful excerpts with the aim of supporting the family by emphasizing their multiple resources [

37]. Finally, although the use of this research tool might be difficult to implement in day-to-day clinical practice (e.g., time consumption), the benefits may outweigh the costs. The next steps might include a dialog with clinicians and empirical investigations regarding the utility and effectiveness of using the LTP–CDT for clinical purposes.

In conclusion, the present study introduced a new observational tool that could help researchers to further investigate the quality of mother–father–adolescent interactions. The evidence presented here suggests that the designed rating scales provide for various indicators and behaviors that seem to achieve the necessary reliability and validity. With this article, we hope to stimulate more research on family triads beyond the mother–child dyad. Indeed, the extension of the FA model to adolescence might lead to the possibility of studying families with a more complete perspective, for example, by following birth cohorts from infancy to adolescence within a given framework that allows for a family-level perspective.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on

Preprints.org, Document S1: Instructions for the LTP-CDT task; Document S2: Detailed description of the FCAAS scales; Table S3. Spearman correlations between all study and control variables.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.R., N.F., and H.T.; methodology, M.R. and H.T.; software, M.R. and H.T.; formal analysis, M.R. and H.T.; investigation, M.R., A.F., A.B., A.M., and M.S.; data curation, M.R., A.F., A.B., A.M., and M.S; writing—original draft preparation, M.R., N.F., and H.T.; writing—review and editing, M.R., N.F., A.F., A.B., A.M., M.S., and H.T.; supervision, M.R., N.F., and H.T.; project administration, M.R., N.F., and H.T.;. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Cantonal Commission on Ethics in Human Research of the State of Vaud (CER-VD; Project n. 2021-01859, 2021/10/25).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| CER-VD |

Commission cantonale d’éthique du canton de Vaud [Cantonal Commission on Ethics in Human Research of the State of Vaud] |

| CFA |

Confirmatory factor analysis |

| CFI |

Comparative fit index |

| CIPA |

Coparenting inventory for parents and adolescents |

| FA |

Family alliance |

| FAAS |

Family alliance assessment scales |

| FCAAS |

Family conflict and alliance assessment scales |

| HRO |

Human research ordinance |

| ICC |

Intraclass correlation coefficient |

| LTP |

Lausanne trilogue play |

| LTP-CDT |

Lausanne trilogue play – conflict discussion task |

| RAS |

Relationship assessment scale |

| RMSEA |

Root mean square error of approximation |

| SEM |

Structural equation modeling |

| SRMR |

Standardized root mean square residual |

| TLI |

Tucker-Lewis Index |

References

- Favez, N.; Frascarolo, F.; Tissot, H. The family alliance model: A way to study and characterize early family interactions. Frontiers in Psychology 2017, 8. [CrossRef]

- Paley, B.; Hajal, N.J. Conceptualizing Emotion Regulation and Coregulation as Family-Level Phenomena. Clinical Child and Family Psychology Review 2022, 25, 19-43. [CrossRef]

- Tissot, H.; Lapalus, N.; Frascarolo, F.; Despland, J.-N.; Favez, N. Family Alliance in Infancy and Toddlerhood Predicts Social Cognition in Adolescence. Journal of Child and Family Studies 2022, 31, 1338–1349. [CrossRef]

- Teubert, D.; Pinquart, M. The Association Between Coparenting and Child Adjustment: A Meta-Analysis. Parenting 2010, 10, 286-307. [CrossRef]

- Kerig, P.K.; Lindahl, K.M. Family observational coding systems: Resources for systemic research; Psychology Press: 2000.

- Grotevant, H.D.; Carlson, C.I. Family interaction coding systems: A descriptive review. Family Process 1987, 26, 49-74. [CrossRef]

- Hampson, R.B.; Beavers, W.R.; Hulgus, Y.F. Insiders' and outsiders' views of family: The assessment of family competence and style. Journal of Family Psychology 1989, 3, 118–136. [CrossRef]

- Romet, M.; Favez, N.; De Vasconcelos, S.; Haueter, C.; Malassagne, M.; Rosselet Amoussou, J.; Urben, S.; Tissot, H. Association between the quality of observed parent–adolescent interactions and physiological emotion regulation in adolescents: A systematic review. 2023.

- Mollà Cusí, L.; Günther-Bel, C.; Vilaregut Puigdesens, A.; Campreciós Orriols, M.; Matalí Costa, J.L. Instruments for the Assessment of Coparenting: A Systematic Review. Journal of Child and Family Studies 2020, 29, 2487-2506. [CrossRef]

- Baril, M.E.; Crouter, A.C.; McHale, S.M. Processes linking adolescent well-being, marital love, and coparenting. Journal of Family Psychology 2007, 21, 645-654. [CrossRef]

- Fivaz-Depeursinge, E.; Corboz-Warnery, A. The primary triangle: A developmental systems view of mothers, fathers, and infants; Basic Books: New York, NY, 1999.

- Tissot, H.; Favez, N. The Lausanne Trilogue Play: bringing together developmental and systemic perspectives in clinical settings. Australian and New Zealand Journal of Family Therapy 2023, 44, 511–520. [CrossRef]

- Favez, N.; Scaiola, C.L.; Tissot, H.; Darwiche, J.; Frascarolo, F. The Family Alliance Assessment Scales: Steps Toward Validity and Reliability of an Observational Assessment Tool for Early Family Interactions. Journal of Child and Family Studies 2011, 20, 23-37. [CrossRef]

- Favez, N.; Lopes, F.; Bernard, M.; Frascarolo, F.; Lavanchy Scaiola, C.; Corboz-Warnery, A.; Fivaz-Depeursinge, E. The development of family alliance from pregnancy to toddlerhood and child outcomes at 5 years. Family process 2012, 51, 542–556. [CrossRef]

- Favez, N.; Frascarolo, F.; Carneiro, C.; Montfort, V.; Corboz-Warnery, A.; Fivaz-Depeursinge, E. The development of the family alliance from pregnancy to toddlerhood and children outcomes at 18 months. Infant and Child Development 2006, 15, 59-73. [CrossRef]

- Mensi, M.M.; Orlandi, M.; Rogantini, C.; Provenzi, L.; Chiappedi, M.; Criscuolo, M.; Castiglioni, M.C.; Zanna, V.; Borgatti, R. Assessing Family Functioning Before and After an Integrated Multidisciplinary Family Treatment for Adolescents With Restrictive Eating Disorders. Frontiers in psychiatry 2021, 12. [CrossRef]

- Gottman, J.M.; Notarius, C.I. Decade review: Observing marital interaction. Journal of Marriage and the Family 2000, 62, 927-947. [CrossRef]

- Persram, R.J.; Scirocco, A.; Della Porta, S.; Howe, N. Moving beyond the dyad: Broadening our understanding of family conflict. Human Development 2019, 63, 38-70. [CrossRef]

- Branje, S. Development of parent–adolescent relationships: Conflict interactions as a mechanism of change. Child development perspectives 2018, 12, 171-176. [CrossRef]

- Warmuth, K.A.; Cummings, E.M.; Davies, P.T. Constructive and destructive interparental conflict, problematic parenting practices, and children’s symptoms of psychopathology. Journal of Family Psychology 2020, 34, 301-311. [CrossRef]

- Weymouth, B.B.; Buehler, C.; Zhou, N.; Henson, R.A. A Meta-Analysis of Parent–Adolescent Conflict: Disagreement, Hostility, and Youth Maladjustment. Journal of Family Theory & Review 2016, 8, 95-112. [CrossRef]

- Romet, M.; Favez, N.; Tissot, H. Family conflict and alliance assessment scales - with adolescents (FCAAS). 2023.

- Harris, P.A.; Taylor, R.; Thielke, R.; Payne, J.; Gonzalez, N.; Conde, J.G. Research electronic data capture (REDCap)—a metadata-driven methodology and workflow process for providing translational research informatics support. Journal of biomedical informatics 2009, 42, 377-381. [CrossRef]

- Hendrick, S.S. A Generic Measure of Relationship Satisfaction. Journal of Marriage and Family 1988, 50, 93-98. [CrossRef]

- Saramago, M.; Lemétayer, F.; Gana, K. Adaptation et validation de la version française de l’échelle d’évaluation de la relation. Psychologie Française 2021, 66, 333-343. [CrossRef]

- Teubert, D.; Pinquart, M. The Coparenting Inventory for Parents and Adolescents (CI-PA): Reliability and validity. European Journal of Psychological Assessment 2011, 27, 206-215. [CrossRef]

- Zimmermann, G.; Antonietti, J.-P.; Sznitman, G.A.; Petegem, S.V.; Darwiche, J. The French version of the coparenting inventory for parents and adolescents (CI-PA): psychometric properties and a cluster analytic approach. Journal of Family Studies 2020, 28, 652-677. [CrossRef]

- Favez, N.; Tissot, H.; Frascarolo, F. Is it typical? The ecological validity of the observation of mother-father-infant interactions in the Lausanne Trilogue Play. European Journal of Developmental Psychology 2019, 16, 113–121. [CrossRef]

- Ten Hove, D.; Jorgensen, T.D.; van der Ark, L.A. Updated guidelines on selecting an intraclass correlation coefficient for interrater reliability, with applications to incomplete observational designs. Psychological methods 2022. [CrossRef]

- Muthén, L.K.; Muthén, B.O. Mplus User's Guide, 8th ed.; Muthén & Muthén: Los Angeles, CA, 1998-2023.

- Hu, L.-t.; Bentler, P.M. Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Structural Equation Modeling: A Multidisciplinary Journal 1999, 6, 1–55. [CrossRef]

- Whittaker, T.A. Using the Modification Index and Standardized Expected Parameter Change for Model Modification. The Journal of Experimental Education 2012, 80, 26-44. [CrossRef]

- Golay, P.; Lecerf, T. Taille d’échantillon et risque de rejet erroné du modèle en analyse factorielle confirmatoire: une étude Monte-Carlo. In Proceedings of the XXe Journées internationales de Psychologie Différentielle, Rennes: université Rennes, 2012; pp. 26-29.

- Minuchin, S. Families & family therapy; Harvard University Press: Boston, MA, 1974.

- Ece, C.; Gürmen, M.S.; Acar, İ.H.; Buyukcan-Tetik, A. Examining the dyadic association between marital satisfaction and coparenting of parents with young children. Current Psychology 2023, 43, 1473–1482. [CrossRef]

- Beam, C.R.; Marcus, K.; Turkheimer, E.; Emery, R.E. Gender differences in the structure of marital quality. Behavior genetics 2018, 48, 209-223. [CrossRef]

- McHale, J.; Tissot, H.; Mazzoni, S.; Hedenbro, M.; Salman-Engin, S.; Philipp, D.A.; Darwiche, J.; Keren, M.; Collins, R.; Coates, E.; et al. Framing the work: A coparenting model for guiding infant mental health engagement with families. Infant Mental Health Journal 2023, 44, 638-650. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).