Submitted:

19 February 2025

Posted:

20 February 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants

2.2. Settings and Researchers

2.3. Assessment Instruments

2.3.1. Standardized Assessment Measures

2.3.1.1. Family Functioning

2.3.1.2. Family Rituals

2.3.1.3. Family Burden

2.3.2. Qualitative Assessment

2.3.2.1. Semi-Structured Interview

2.4. Design and Procedure

2.5. Data Collection and Analysis

2.5.1. Quantitative Analysis

2.5.2. Qualitative Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Quantitative Outcomes

3.1.1. Family Assessment Device

3.1.2. Family Rituals Scale (FRS) and Family Burden Scale (FBS)

3.2. Qualitative Analysis of Parents’ Self-Reports

3.2.1. Knowledge About ASD

3.2.1.1. Understanding of the Causes of ASD

3.2.1.2. Symptomatology of ASD

3.2.1.3. Treatment of ASD

3.2.2. Stigma Management

3.2.2.1. Social Stigma Management

3.2.2.2. Self-Stigma Management

4. Discussion

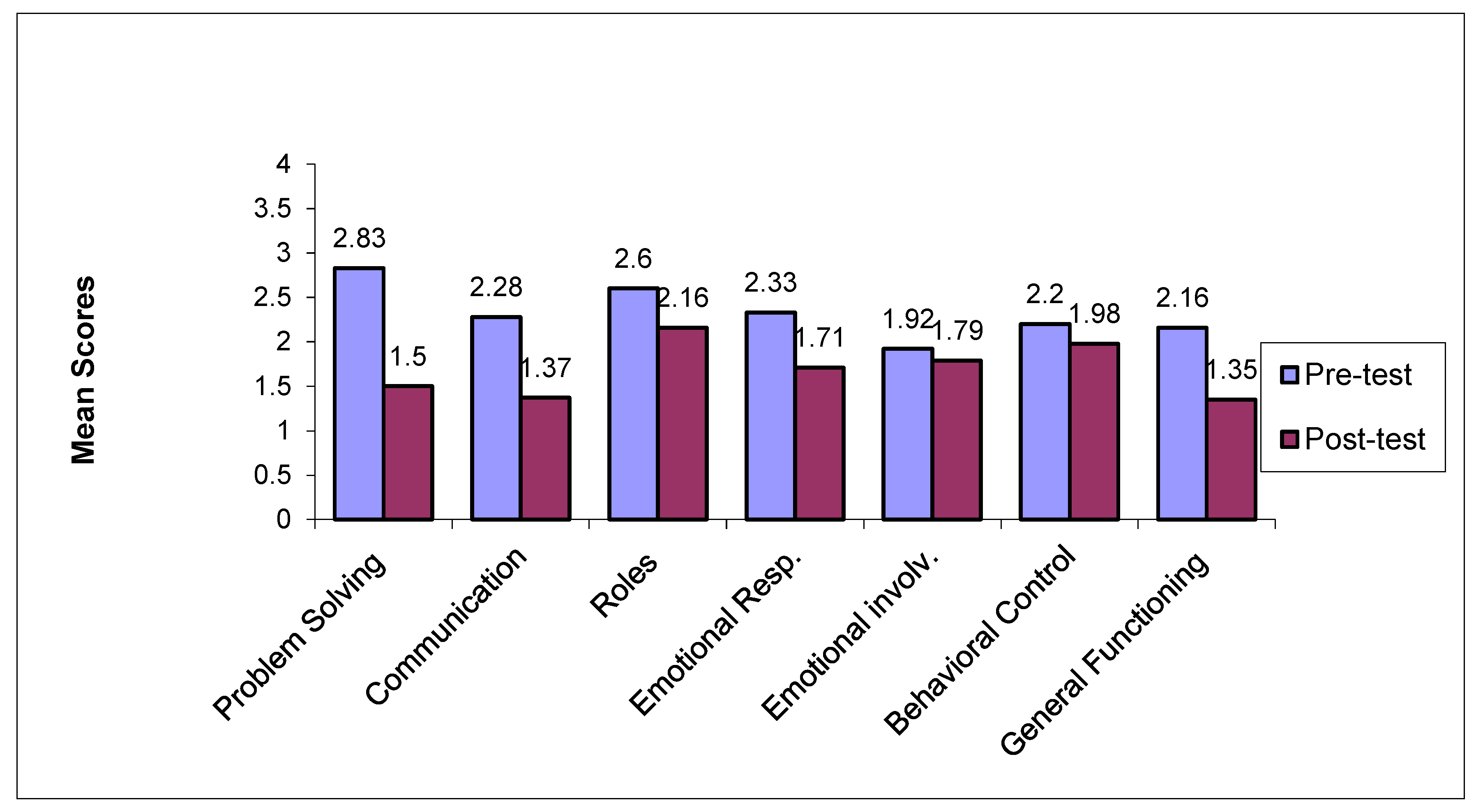

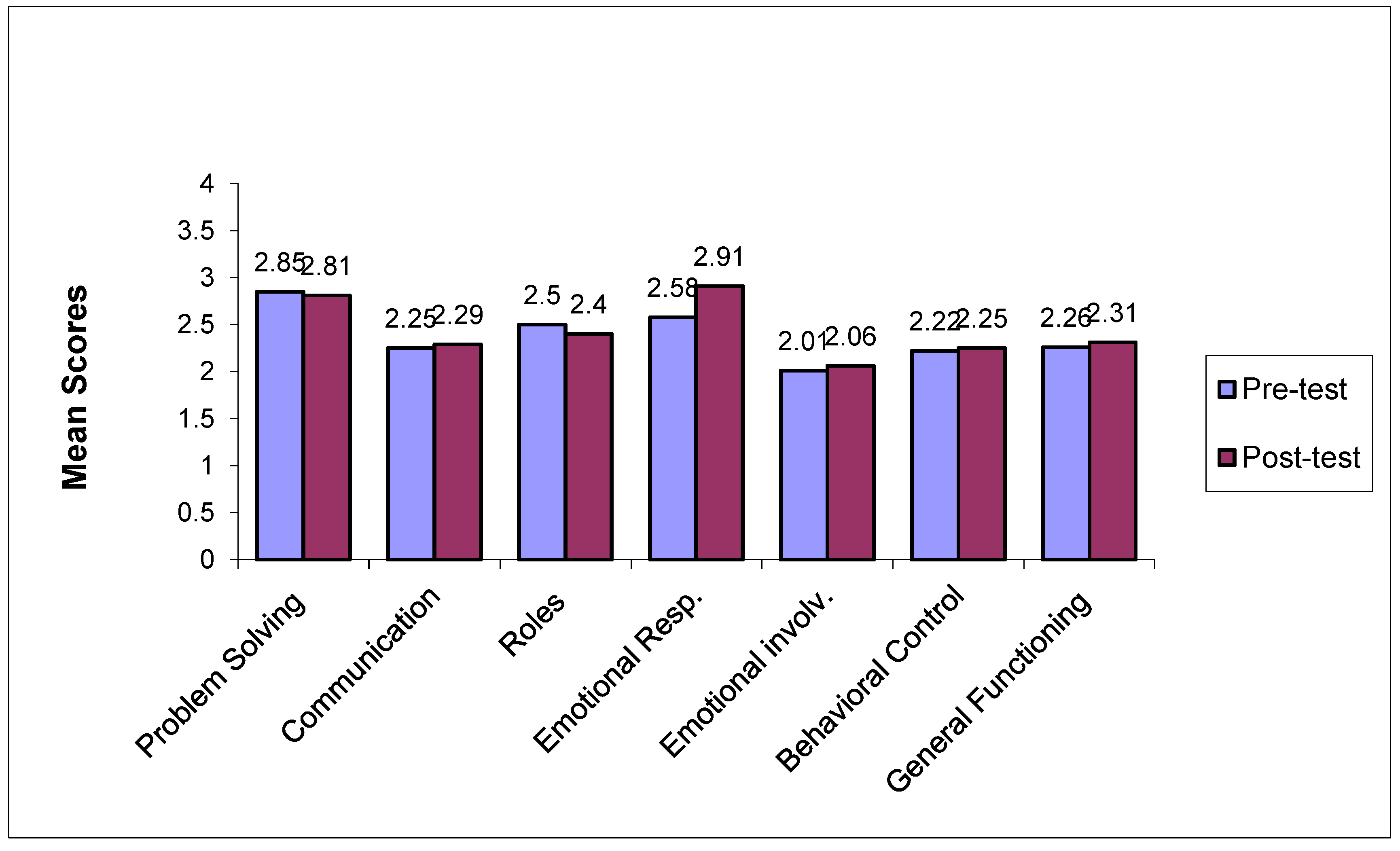

- On the FAD, prior to intervention, the scores obtained place family functioning within pathological levels in six out of seven family function subscales for both groups. These results are consistent with findings of previous studies that report high stress levels, negative emotional intensity and marital communication and problem-solving difficulties in parents of children with ASD [6,10,17,18,19,28,33]. Following intervention, scores within normal range were obtained on the six aforementioned sub-scales only for the treatment group. Specifically, the following areas were improved: emotional responsiveness, communication, behavior control and allocating roles and responsibilities, and problem solving. To our knowledge, this is the first study that demonstrates improved communication and problem-solving skills in parents of children with ASD, following the application of a psychoeducational treatment program, in contrast to prior findings [6,63,64]. As pointed out, lack of improvement in those two domains may have been attributed to the short duration of the psychoeducational intervention applied in earlier studies. The effectiveness of the present psychoeducational model may be attributed to its duration (long-term application) and to the fact that it included group psychological counselling and social support among group members [64,66].

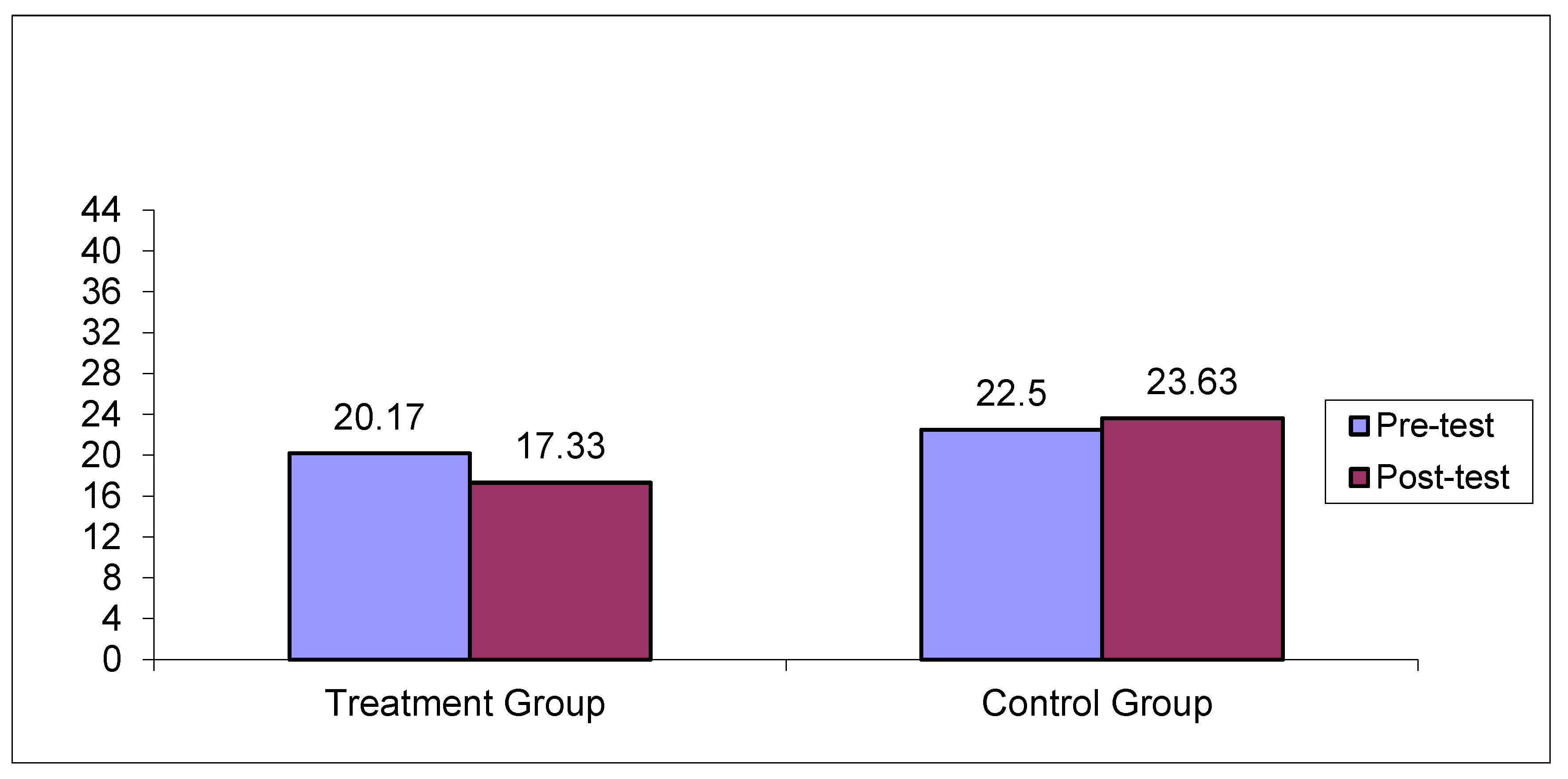

- On the FRS, prior to intervention, the scores obtained indicated serious disruption in family rituals and routines. These findings were anticipated, since the FRS assesses engagement of family members in activities, such as family traditions or religious holidays, family celebrations and trips, and patterned routines (e.g., eating together on Sundays, cooking special meals, going out on weekends) – areas in which most families with a child with ASD encounter great disruption [50]. Following intervention, statistically significant improvements were noted in all the aforementioned areas. These findings are consistent with prior findings pertaining to psychoeducational therapeutic programs applied to families of other clinical populations [25,30].

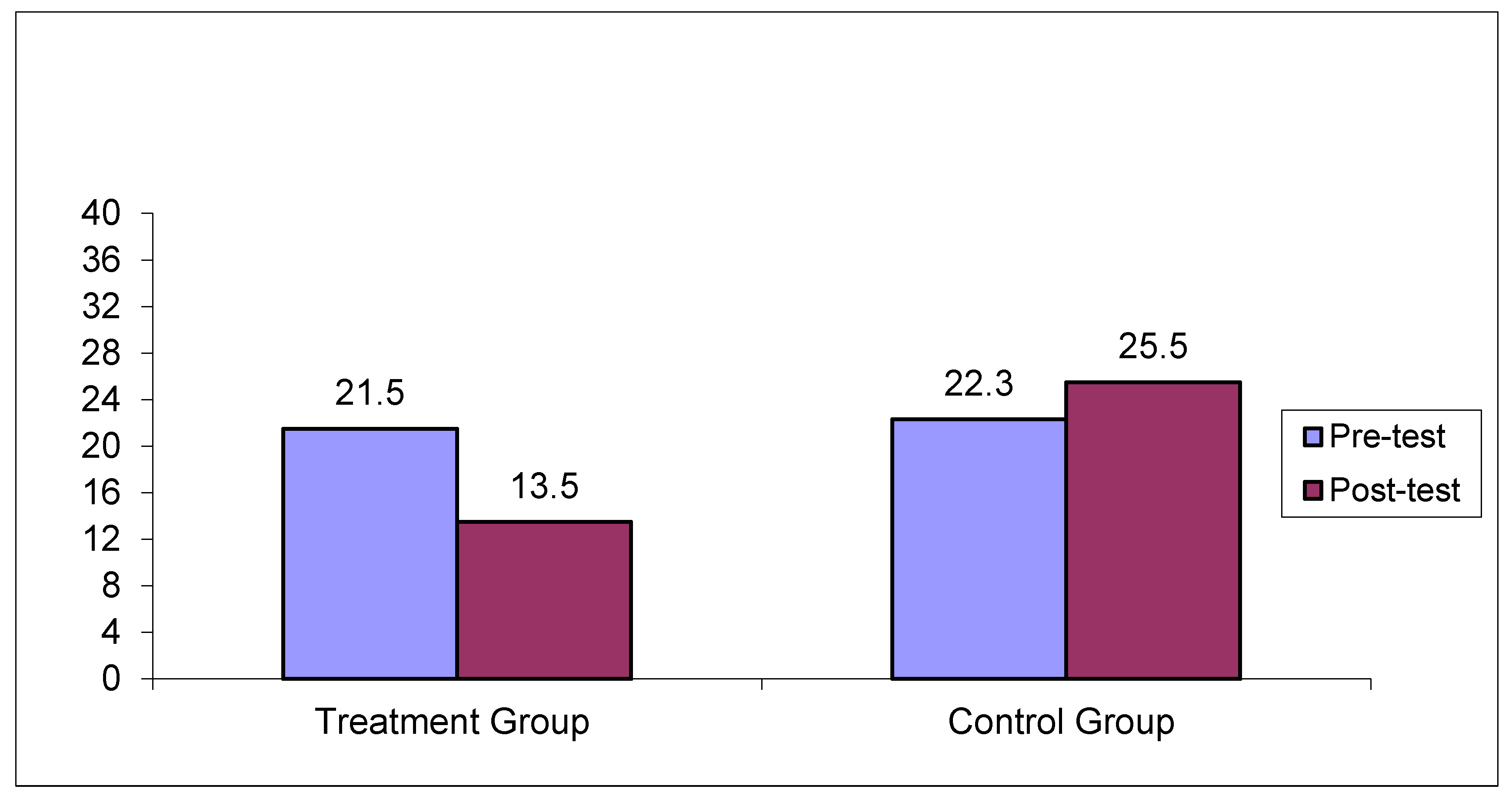

- On the FBS, which assesses subjective and objective burden, it is worth noting that prior to treatment parental burden was within marginal normal range (slightly below the cutoff point). This finding was unexpected, in light of the relevant literature worldwide that underlines high levels of family burden due to the strain associated with raising a child with ASD [10,14,67,68,69]. This finding may be attributed to the fact that the children of all families who participated had been receiving behavior analytic treatment for several years. Thus, service needs of the children of those families were met to a satisfactory degree, which, according to empirical findings, is an important factor for reducing family burden[70]. Additional tentative explanations relate to culturally bound differences, since anecdotal data suggest that Mediterranean parents, and particularly mothers, refuse to perceive or to admit that their offspring with a handicap is a “burden” [24,30]. Following intervention, statistically significant reductions were noted by all parents in (a) family social isolation, (b) behavior outbursts of the child with ASD, and (c) the emergence of psychosomatic health issues as a result of extending provision of care. This is a crucial finding since there is limited evidence about the effectiveness of group psychoeducation programs in decreasing objective and subjective burden of families with a member with ASD [33,68,71].

- Parents reported more accurate information about the etiology and the characteristics of ASD and appreciated the importance of early intervention and of parent training in behavior management and in problem-solving with the aim to achieve optimal outcomes. Those findings are consistent with the existing literature related to the benefits of psychoeducation and parent training on parental skills and knowledge pertaining to ASD [33,72,73].

- Thematic analysis of parental reports reflected major improvements on social- and on self-stigma management. Namely, parents shifted from parental social withdrawal, avoidance of public places, shame, and embarrassment for their child’s behavior to active social networking with other group members and relatives and a proactive tendency to inform other people about their offspring’s disability, mainly by organizing outdoor activities and by participating actively in public events. Pertaining to self-stigma, parents shifted from self-blame, a sense of failure in the parental role, fear of social judgement and social rejection to a sense of efficacy in the parental role and a sense of pride for being a parent of a child with ASD. Those shifts may work as a buffer against cultural reactions to aberrant behavior (e.g., staring, rude comments, or avoiding interaction), since having a more accurate understanding of ASD is identified as one of the critical factors for empowering families against stigma [33,72,73].

4.1. Study Limitations and Implications for Future Research

5. Conclusion

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| ASD | Autism spectrum disorder |

| ISBA | Institute of systemic behavior analysis |

| DCH II | Day Center Hara II |

| FAD | Family assessment device |

| FRS | Family ritual scale |

| FBS | Family burden scale |

| NKUA | National and kapodistrian university of Athens |

References

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders-DSM-5-TR. 5th ed.; American Psychiatric Publishing, Washington DC., 2022; pp.125-132. [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. Autism spectrum disorders. Available online: https://communitymedicine4asses.wordpress.com/2023/03/31/who-updates-fact-sheet- on-autism-29-march-2023/ (accessed on 29 October 2024).

- Zhou, H.; Xu, X.; Yan, W.; Zou, X.; Wu, L.; Luo, X. & LATENT-NHC Study Team. Prevalence of autism spectrum disorder in China: a nationwide multi-center population- based study among children aged 6 to 12 years. Neuroscience Bulletin 2020, 36, 961–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maenner, M.J.; Warren, Z.; Williams, A.R.; Amoakohene, E.; Bakian, A.V.; Bilder, D.A.; Durkin, M.S.; Fitzgerald, R.T.; Furnier, S.M.; Hughes, M.M.; Ladd-Acosta, C.M.; McArthur, D.; Pas, E.T.; Salinas, A.; Vehorn, A.; Williams, S.; Esler, A.; Grzybowski, A.; Hall-Lande, J.; Nguyen, R.H.N.; … Shaw, K.A. Prevalence and Characteristics of Autism Spectrum Disorder Among Children Aged 8 Years - Autism and Developmental Disabilities Monitoring Network, 11 Sites, United States, 2020. Morbidity and mortality weekly report. Surveillance summaries Washington, D.C. 2002, 72, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fenning, R.M.; & Butter, E.M. ; Johnson, E.M. Butter, & L. Scahill (Eds.), Parent training for autism spectrum disorder. In C. R.; Johnson, E.M. Butter, & L. Scahill (Eds.), Parent training for autism spectrum disorder: Improving the quality of life for children and their families. American Psychological Association, 2020; Johnson, E.M. Butter, &. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DaWalt, L.S.; Greenberg, J.S.; & Mailick, M.R. ; & Mailick, M. R. Transitioning Together: A Multi-family Group Psychoeducation Program for Adolescents with ASD and Their Parents. Journal of autism and developmental disorders, 2018, 48, 251–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pillay, M.; Alderson-Day, B.; Wright, B.; Williams, C.; Urwin, B. Autism Spectrum Conditions--enhancing Nurture and Development (ASCEND): an evaluation of intervention support groups for parents. Clinical child psychology and psychiatry 2011, 16, 5–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rivard, M.; Terroux, A.; Parent-Boursier, C.; Mercier, C. Determinants of stress in parents of children with autism spectrum disorders. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders 2014, 44, 1609–1620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bishop-Fitzpatrick, L.; Mazefsky, C.A.; Minshew, N.J.; Eack, S.M. The Relationship Between Stress and Social Functioning in Adults With Autism Spectrum Disorder and Without Intellectual Disability. Autism Res, 2015, 8:164-173. [CrossRef]

- Gena, A.; Balamotis, G. H Oikogeneia tou Paidiou me Aftismo. Tomos A΄. Oi Goneis. Gutenberg, Athens, Greece, 2013; 124-127.

- Hayes, S.A.; Watson, S.L. The impact of parenting stress: a meta-analysis of studies comparing the experience of parenting stress in parents of children with and without autism spectrum disorder. Journal of autism and developmental disorders 2013, 43, 629–642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruiz-Robledillo, N.; Moya-Albiol, L. Lower electrodermal activity to acute stress in caregivers of people with autism spectrum disorder: an adaptive habituation to stress. Journal of autism and developmental disorders 2015, 45, 576–588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gau, S.S.F.; Chou, M.C.; Chiang, H.L.; Lee, J.C.; Wong, C.C.; Chou, W.J.; Wu, Y.Y. Parental adjustment, marital relationship, and family function in families of children with autism. Research in Autism spectrum disorders 2011, 6, 263–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lavelle, T.A.; Weinstein, M.C.; Newhouse, J.P.; Munir, K.; Kuhlthau, K.A.; Prosser, L.A. Economic burden of childhood autism spectrum disorders. Pediatrics 2011, 133, e520–e529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kavaliotis, P. Accurate Diagnosis of the Syndrome in Children with Autism Spectrum Disorders and Parents’ Resilience. Journal of Educational and Developmental Psychology 2017, 7, 218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piro-Gambetti, B.; Greenlee, J.; Hickey, E.J.; Putney, J.M.; Lorang, E.; Hartley, S.L. Parental Depression Symptoms and Internalizing Mental Health Problems in Autistic Children. Journal of autism and developmental disorders 2023, 53, 2373–2383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baker, J.K.; Seltzer, M.M.; & Greenberg, J.S. ;& Greenberg, J. S. Longitudinal effects of adaptability on behavior problems and maternal depression in families of adolescents with autism. Journal of Family Psychology 2011, 25, 601–609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greenberg, L.S.; Pascual-Leone, A. Emotion in psychotherapy: A practice-friendly research review. J. Clin. Psychol. 2006, 62: 611-630. [CrossRef]

- Hastings, R.P.; Lloyd, T. (Expressed emotion in families of children and adults with intellectual disabilities. Ment. Retard. Dev. Disabil. Res. Rev. 2007, 13: 339-345. [CrossRef]

- Woodman, A.C.; Smith, L.E.; Greenberg, J.S.; Mailick, M.R. Contextual Factors Predict Patterns of Change in Functioning over 10 Years Among Adolescents and Adults with Autism Spectrum Disorders. Journal of autism and developmental disorders 2016, 46, 176–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jungbauer, J.; Wittmund, B.; Dietrich, S.; Angermeyer, M.C. Subjective burden over 12 months in parents of patients with schizophrenia. Archives of psychiatric nursing 2003, 17, 126–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lauber, C.; Nordt, C.; Falcato, L.; Rössler, W. Do people recognize mental illness? Factors influencing mental health literacy. European archives of psychiatry and clinical neuroscience 2003, 253, 248–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magliano, L.; Fiorillo, A.; De Rosa, C.; Maj, M.; Family burden and social network in schizophrenia, vs. physical diseases: preliminary results from an Italian national study. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica 2006, 113: 60-63. [CrossRef]

- Grandón, P.; Jenaro, C.; Lemos, S. Primary caregivers of schizophrenia outpatients: burden and predictor variables. Psychiatry research 2008, 158, 335–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madianos, M.; Economou, M.; Dafni, O.; Koukia, E.; Palli, A.; Rogakou, E. (Family disruption, economic hardship and psychological distress in schizophrenia: can they be measured? . European psychiatry : the journal of the Association of European Psychiatrists 2004, 19, 408–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nasr, T.; Kausar, R. Psychoeducation and the family burden in schizophrenia: a randomized controlled trial. Annals of general psychiatry 2009, 8, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ağırkan, M.; Koç, M.; Avcı, Ö.H. How effective are group-based psychoeducation programs for parents of children with ASD in Turkey? A systematic review and meta-analysis. Research in Developmental Disabilities 2023, 139, 104554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, A.; Singhal, N. Psychosocial support for families of children with autism. Asia Pacific Disability Rehabilitation Journal 2005, 16, 62–83. [Google Scholar]

- Epstein, N.B.; Baldwin, L.M.; Bishop, D.S. The McMaster family assessment device. Journal of marital and family therapy 1983, 9, 171–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsiouri, I.; Gena, A.; Economou, M.P.; Bonotis, K.S.; Mouzas, O. Does Long-Term Group Psychoeducation of Parents of Individuals with Schizophrenia Help the Family as a System? A Quasi-Experimental Study. International Journal of Mental Health 2015, 44, 316–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsujita, M.; Homma, M.; Kumagaya, S.I.; Nagai, Y. (Comprehensive intervention for reducing stigma of autism spectrum disorders: Incorporating the experience of simulated autistic perception and social contact. PloS one 2023, 18, e0288586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dubreucq, J.; Plasse, J.; Franck, N. Self-stigma in Serious Mental Illness: A Systematic Review of Frequency, Correlates, and Consequences. Schizophrenia bulletin 2021, 47, 1261–1287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kollia, S.E.; Tsirempolou, E.; Gena, A. Encouraging the efforts of the family system: A psychoeducational therapeutic intervention for parents of children with Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD). Cogn.-Behav. Res. Ther 2020, 6, 47–51. [Google Scholar]

- Lopez, J.; Crespo, M.; Zarit, S. (Assessment of the Efficacy of a Stress Management Program for Informal Caregivers of Dependent Older Adults. The Gerontologist 2007, 47, 205–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sorrell, J.M. Moving beyond caregiver burden: identifying helpful interventions for family caregivers. Journal of psychosocial nursing and mental health services 2014, 52, 15–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Mierlo, L.D.; Van der Roest, H.G.; Meiland, F.J.; Dröes, R.M. Personalized dementia care: proven effectiveness of psychosocial interventions in subgroups. Ageing research reviews 2010, 9, 163–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Falloon, I.R.; Liberman, R.P. Interactions between drug and psychosocial therapy in schizophrenia. Schizophrenia bulletin 1983, 9, 543–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Falloon, I.R. Family interventions for mental disorders: efficacy and effectiveness. World psychiatry : official journal of the World Psychiatric Association (WPA) 2003, 2, 20–28. [Google Scholar]

- Yu, Y.; McGrew, J.H.; Boloor, J. Effects of caregiver-focused programs on psychosocial outcomes in caregivers of individuals with ASD: A meta-analysis. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders 2019, 49, 4761–4779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anderson, C.M.; Hogarty, G.E.; Reiss, D.J. Family treatment of adult schizophrenic patients: A psycho-educational approach. Schizophrenia Bulletin 1980, 6, 490–505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Falloon, I.R.H.; McGill, C.W.; Boyd, J.L.; Pederson, J. Family management in the prevention of morbidity of schizophrenia: social outcome of a two-year longitudinal study. Psychological Medicine 1987, 17, 59–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lucksted, A.; McFarlane, W.; Downing, D.; Dixon, L. Recent Developments in Family Psychoeducation as an Evidence-Based Practice. Journal of Marital and Family Therapy 2012, 38: 101-121. [CrossRef]

- Tessier, A.; Roger, K.; Gregoire, A.; Desnavailles, P.; Misdrahi, D. Family psychoeducation to improve outcome in caregivers and patients with schizophrenia: a randomized clinical trial. Frontiers in psychiatry 2023, 14, 1171661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bäuml, J.; Froböse, T.; Kraemer, S.; Rentrop, M.; & Pitschel-Walz, G. Psychoeducation: a basic psychotherapeutic intervention for patients with schizophrenia and their families. Schizophrenia bulletin 2006, 32(suppl_1), S1-S9. [CrossRef]

- Chiquelho, R.; Neves, S.; Mendes, A.; Relvas, A.P.; Sousa, L. ProFamilies: a psycho-educational multi-family group intervention for cancer patients and their families. European journal of cancer care 2011, 20, 337–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McFarlane, W.R.; Dixon, L.; Lukens, E.; Lucksted, A. Family psychoeducation and schizophrenia: a review of the literature. Journal of marital and family therapy, 2003, 29, 223–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Motlova, L.; Dragomirecka, E.; Spaniel, F. Relapse prevention in schizophrenia: does group family psychoeducation matter? One-year prospective follow-up field study. Int J Psychiatry Clin Pract. 2006, 10:38-44. [CrossRef]

- Pilling, S.; Bebbington, P.; Kuipers, E. Psychological treatments in schizophrenia: Meta-analysis of family intervention and cognitive behaviour therapy. Psychol Med. 2002, 32:763-782. [CrossRef]

- Rummel-Kluge, C.; Kissling, W. Psychoeducation in schizophrenia: new developments and approaches in the field. Current opinion in psychiatry 2008, 21, 168–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Solomon, A.H.; Chung, B. Understanding autism: how family therapists can support parents of children withautism spectrum disorders. Family process 2012, 51, 250–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanrıverdi, D.; Ekinci, M. The effect psychoeducation intervention has on the caregiving burden of caregivers for schizophrenic patients in Turkey. International Journal of Nursing Practice 2012, 18: 281-288. [CrossRef]

- Young, M.E.; Fristad, M.A. Evidence based treatments for bipolar disorder in children and adolescents. Journal of Contemporary Psychotherapy: On the Cutting Edge of Modern Developments in Psychotherapy 2007, 37, 157–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Young, D.K.; Ng, P.Y.; & Cheng, D. ; & Cheng, D. Psychoeducation Group on Improving Quality of Life of Mild Cognitive Impaired Elderly. Research on Social Work Practice 2019, 29, 303–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bearss, K.; Johnson, C.; Smith, T.; Lecavalier, L.; Swiezy, N.; Aman, M.; Scahill, L. Effect of parent training vs parent education on behavioral problems in children with autism spectrum disorder: A randomized clinical trial. Jama 2015, 313, 1524–1533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madianos, M.; Economou, M. Schizophrenia and family rituals: measuring family rituals among schizophrenics and “normals. ” European Psychiatry 1994, 9, 45–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Statharou, A.; Papathanasiou, I.; Gouva, M. ; Masdrakis,V. Interdisciplinary Health Care 2011, 3(2), 59–69. [Google Scholar]

- DeWinter, J., (2013) “Using the Student's t-test with extremely small sample sizes”, Practical Assessment, Research, and Evaluation 18: 10.

- Falloon IRH.; Boyd JL.; McGill CW.. Family Management in the Prevention of Morbidity of Schizophrenia: Clinical Outcome of a Two-Year Longitudinal Study. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1985, 42:887–896. [CrossRef]

- Falloon, I.R.; McGill, C.W.; Matthews, S.M.; Keith, S.J.; & Schooler, N.R. ; & Schooler, N. R. Family treatment for schizophrenia : the design and research application of therapist training models. The Journal of psychotherapy practice and research( 1996, 5, 45–56. [Google Scholar]

- Dieleman, L.M.; Moyson, T.; De Pauw, S.S.W.; Prinzie, P.; Soenens, B. Parents' Need-related Experiences and Behaviors When Raising a Child With Autism Spectrum Disorder. Journal of pediatric nursing 2018, 42, e26–e37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DePape, A.M.; Lindsay, S. Parents' experiences of caring for a child with autism spectrum disorder. Qualitative health research 2015, 25, 569–583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonis, S. Stress and Parents of Children with Autism: A Review of Literature. Issues in Mental Health Nursing 2016, 37, 153–3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scholtz, S.E.; de Klerk, W.; de Beer, L.T. The Use of Research Methods in Psychological Research: A Systematised Review. Frontiers in research metrics and analytics 2020, 5, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ardic, A.; Cavkaytar, A. The effect of the psychoeducational group family education program for families of children with ASD on parents: A pilot study. International Journal of Early Childhood Special Education 2019, 11, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Güler, G.; Bedel, A. The Effect of Group Guidance Program on Family Stress and Burnout Levels for Parents of Children with Special Needs. Psycho-Educational Research Reviews 2024, 13, 77–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dixon, L.; Adams, C. ; & Lucksted, AUpdate on family psychoeducation for schizophrenia. Schizophrenia bulletin 2000, 26, 5–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bhuiyan, M.R. ; Islam, M. Z. Coping Strategies for Financial Burden of Family for the Children with Autism Spectrum Disorder. Bangladesh Armed Forces Medical Journal 2024, 56, 56, 38–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.; Lu, F.; Wang, X.; Luo, Y.; Zhang, R.; He, P.; Zheng, X. The economic burden of autism spectrum disorder with and without intellectual disability in China: A nationwide cost-of-illness study. Asian journal of psychiatry 2024, 92, 103877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Picardi, A.; Gigantesco, A.; Tarolla, E.; Stoppioni, V.; Cerbo, R.; Cremonte, M.; Alessandri, G.; Lega, I.; Nardocci, F. Parental Burden and its Correlates in Families of Children with Autism Spectrum Disorder: A Multicentre Study with Two Comparison Groups. Clinical practice and epidemiology in mental health: CP&EMH 2018, 14, 143–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montenegro, M.C.; Abdul-Chani, M.; Valdez, D.; Rosoli, A.; Garrido, G.; Cukier, S.; Paula, C.S.; Garcia, R.; Rattazzi, A.; Montiel-Nava, C. Perceived Stigma and Barriers to Accessing Services: Experience of Caregivers of Autistic Children Residing in Latin America. Research in developmental disabilities 2022, 120, 104123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaçan, H.; Gümüş, F.; Bayram Değer, V. Effect of individual psychoeducation for primary caregivers of children with autism on internalized stigma and care burden: a randomized controlled trial. International Journal of Developmental Disabilities 2023, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McAleese, A.; Lavery, C.; & Dyer, K.F. ; & Dyer, K. F. Evaluating a psychoeducational, therapeutic group for parents of children with autism spectrum disorder. Child Care in Practice 2014, 20, 162–181. [Google Scholar]

- O'Donovan, K.L.; Armitage, S.; Featherstone, J.; McQuillin, L.; Longley, S.; Pollard, N. Group-based parent training interventions for parents of children with autism spectrum disorders: A literature review. Review Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders 2019, 6, 85–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deguchi, N.K.; Asakura, T.; Omiya, T. Self-Stigma of Families of Persons with Autism Spectrum Disorder: a Scoping Review. Rev J Autism Dev Disor. 2021, 8, 373–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salleh, N.S.; Abdullah, K.L.; Yoong, T.L.; Jayanath, S.; Husain, M. Parents' Experiences of Affiliate Stigma when Caring for a Child with Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD): A Meta-Synthesis of Qualitative Studies. Journal of pediatric nursing 2020, 55, 174–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Treatment Group N = 6 |

Control Group N = 6 |

Total Sample N = 12 |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Sociodemographic Characteristics Parents |

M, or N | SD, or % | M, or N | SD, or % | M, or N | SD, or % |

| Fathers | 3 | 50% | 3 | 50% | 6 | 50% |

| Mothers | 3 | 50% | 3 | 50% | 6 | 50% |

| Age (M ± SD) | 40.83 | ±3.66 | 41.17 | ±4.6 | 41.00 | ±3.9 |

| Years of formal education (M ± SD) |

14.67 | ±4.0 | 13.33 | ±2.8 | 14.00 | ±3.3 |

|

Sociodemographic Characteristics of offsprings with ASD |

||||||

| Age (M ± SD) |

7.34 | ±2.55 | 6.45 | ±3.4 | 7.11 | ±3.2 |

| Years since initial diagnosis (M ± SD) |

5.00 | ±0.8 | 4.33 | ±1.3 | 4.67 | ±1.1 |

| Received specialized treatment services | ISBA | DCH II | ||||

| Intensity of treatment | < 3 hours per day | <3 hours per day | ||||

| Topics per session | Sessions |

|---|---|

| A. Pre-test assessment | |

Individualized semi-structured interviews with each member of group to assess:

|

1 session per participant |

| Treatment group psychoeducational therapeutic program |

Duration (in 90 minute sessions) |

|

1 group session |

|

1 group session |

|

3 group sessions |

|

3 group session s |

|

10 group sessions |

|

5 group sessions |

|

1 group session |

| Total numberof treatment sessions | 23 group sessions |

| Post-test assessment | |

Individualized semi-structured interviews with each member of the group to assess

|

1 session per participant |

| Treatment Group (N=6) |

Control Group (N=6) |

Average Rank Between the two groups comparisons** |

||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| FAD subscales |

Pre-test Mean (±SD) |

Post-test Mean (±SD) |

z value* (p<.05) |

Pre-test Mean(±SD) |

Post-test Mean(± SD) |

z value* (p<.05) |

Treatment Group (N=6) |

Control Group (N=6) |

P |

|

|

Problem solving Cut-off=2.20 |

2.83 (0.37) | 1.50 ( 0.18) | -2.22 (p=.011) |

2.85 (0.4) | 2.81 (0.23) | –1.83 (p = 0.08) |

Pre | 8.39 | 8.61 | 0.668 |

| Post | 5.50 | 12.50 | 0.001 | |||||||

|

Communication Cut-off=2.20 |

2.28 (0.52) | 1.37 (0.29) | –2.21 (p = .017) |

2.25 (0.5) | 2.29 (0.3) | –0.61 (p = 0.32) |

Pre | 7.21 | 7.65 | 0.773 |

| Post | 3.50 | 11.20 | 0.01 | |||||||

|

Roles Cut-off=2.30 |

2.6 (0.3) | 2.16 (0.3) | –2.20 (p =0.011) |

2.5 (0.3) | 2.4 (0.3) | –0.41 (p = 0.43) |

Pre | 9.56 | 7.44 | 0.342 |

| Post | 8.42 | 8.58 | 0.08 | |||||||

|

Emotional response Cut-off =2.20 |

2.33 (0.7) | 1.71 (0.5) | –1.68 (p = .011) |

2.58 (0.3) | 2.91 (0.4) | –1.73 (p = 0.16) |

Pre | 8.44 | 8.56 | 0.923 |

| Post | 4.81 | 8.19 | 0.001 | |||||||

|

Emotional involvement Cut-off =2.10 |

1.92 (0.2) | 1.79 (0.1) | –2.03 (p = .611) |

2.01 (0.3) | 2.06 (0.4) | –1.41 (p = 0.72) |

Pre | 9.63 | 9.38 | 0.382 |

| Post | 5.00 | 9.12 | 0.002 | |||||||

|

Behavioral control Cut-off =1.90 |

2.20 (0.2) | 1.98 (0.1) | –1.92 (p = 0.04) |

2.22 (0.2) | 2.25 (0.2) | –0.32 (p = 0.12) |

Pre | 8.38 | 8.14 | 0.959 |

| Post | 6.15 | 8.08 | 0.05 | |||||||

|

General Functioning Cut-off =2.00 |

2.16 (0.3) | 1.35 (0.2) | –2.03 (p =0.012) |

2.26 (0.3) | 2.31 (0.3) | –0.08 (p = 0.33) |

Pre | 8.18 | 8.13 | 0.738 |

| Post | 5.44 | 8.56 | 0.007 | |||||||

|

Scales |

Treatment Group (N=6) |

Control Group (N=6) |

Average Rank Between the two groups comparisons** |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pre-test Mean (±SD) | Post-test Mean (±SD) |

z value* (p<.05) |

Pre-test Mean (±SD) |

Post-test Mean (± SD) |

z value* (p<.05) |

Treatment Group (N=6) |

Control Group (N=6) |

P | ||

|

FRS Total Cut off score=18 |

20.17 (2.56) | 17.33 (2.16) | –2.27 (p = 0.027) |

22.50 (4.2) | 23.63 (4.2) | –1.61 (p = 0.08) |

Pre | 6.89 | 6.43 | 0.77 |

| Post | 4.38 | 12.23 | 0.01 | |||||||

|

FBS Total Cut off score=24 |

21.50 (5.11) | 13.5 (4.03) |

–2.22 (p = 0.026) |

22.30 (3.2) | 25.55 (3.6) | –1.02 (p = 0.06) |

Pre | 7.23 | 8.09 | 0.65 |

| Post | 6.62 | 11.94 | 0.02 | |||||||

| FBS Social life |

8.7 0(2.7) | 6.63 (3.9) | –2.73 (p = 0.03) |

9.53 (2.3) | 10.20 (2.2) | –0.33 (p = 0.14) |

Pre | 7.01 | 7.19 | 0.89 |

| Post | 6.19 | 10.31 | 0.04 | |||||||

| FBS Aggres/ness |

3.30 (2.7) | 2.37 (1.8) | –2.6 (p = 0.04) |

3.47 (4.2) | 3.80 (2.6) | –0.15 (p = 0.52) |

Pre | 6.54 | 6.76 | 0.89 |

| Post | 5.10 | 11.00 | 0.01 | |||||||

| FBS Health |

7.25 (2.1) | 3.13 (2.5) | –2.7 (p = 0.011) |

7.63 (3.5) | 8.00 (2.6) | –0.82 (p = 0.14) |

Pre | 8.55 | 8.14 | 0.83 |

| Post | 5.04 | 10.54 | 0.01 | |||||||

| FBS Financial |

2.25 (1.5) | 1.87 (1.3) | –1.4 (p > 0.05) |

2.37 (1.3) | 2.55 (1.3) | –0.34 (p = 0.53) |

Pre |

7.79 | 8.01 | 0.92 |

| Post | 7.12 | 8.31 | 0.69 | |||||||

| 1.Knowledge about ASD | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Before N=12 (common themes for both treatment and control group) |

After N=6 (only treatment group/no pattern shift for control group) |

|||

| Areas | Themes | Example Quotes | Themes | Example Quotes |

| 1.1. Causes | -Psychological-Environmental | “I was stressed out during pregnancy, because of my father’s death”. “I spent too much time on the internet” “I was working long hours”: |

-Neurobiological -Genetic nature |

“Genetic disorder of a very complex nature” “It is a brain dysfunction that happened before birth” “ It is a metabolic disorder –an infection of the brain” |

| -Confusion -Luck or destiny |

“For me it is a confusing disorder that I find hard to understand” “Nobody knows, it was meant to happen to us” |

|||

| 1.2. Symptoms | Personality traits | “My child is an introvert person” “He is very self-absorbed” “He is very immature” “He is very stubborn” “He does not take no for an answer” |

Neurodevelopmental characteristics | “It is a developmental disorder that affects behavior at many levels (communication, emotional expression, play skills, social relations, self-help skills” “It is a neurological health issue. My daughter cannot communicate what she wants and this is why she has a lot of behavior issues”. |

| 1.3. Treatment | -Medical solution -Miracle |

“I hope for a miracle cure” “I pray to God, every day, for him to get well” |

-Psychoeductional programs for the child and the family | “I believe in intensive structured educational programs” “I believe in structure and everyday routines in conjunction with a supportive family atmosphere “ |

| 2. Stigma management | ||||

| 2.1. Social stigma | -Social withdrawal -Shame, anger, guilt |

”I avoid going to the playground with my child” “We are not invited anymore by relatives during the holidays” “I often feel embarrassed when I am in public places with my child “I feel that other people feel sorry for me” “I get really angry when people are staring at us! “ |

-Social networking within the group -Family activities -Social networking with the community and relatives -Need to educate community about ASD |

“I really enjoyed spending the holidays with one of the other families that I met during the group program“ “We are planning a family summer vacation” “We have invited my brother’s family over for Christmas” “I now believe that people understand how difficult raising a child with ASD might be and that they respect me” “I believe that ignorance is the reason for social stigma and that we should inform people about our child’s ASD” |

| 2.2. Self-stigma | -Sense of failure as a parent - Self-blame, self-pity -Increased parental stress |

“I believe that god is punishing me.” “I constantly feel guilty for not doing enough for my child” “I feel that everything is lost” “I feel stressed, wondering whether there is anything else I can do for my child that I cannot financially afford.” “I really don’t know how to handle his behaviors” “I am really worried about the future” |

-Empowerment -Need for advocacy |

“I am very proud that I have a special child, and I think that my son is proud of his parents too” “I really don’t care how other people see us. I just want my child to be happy” |

| -Satisfaction from the parental role | “I feel that we make one small step forward, everyday” “As a father I feel that I respond more and more to my child’s needs. “ |

|||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).