4.2. Carbon Capture Simulation

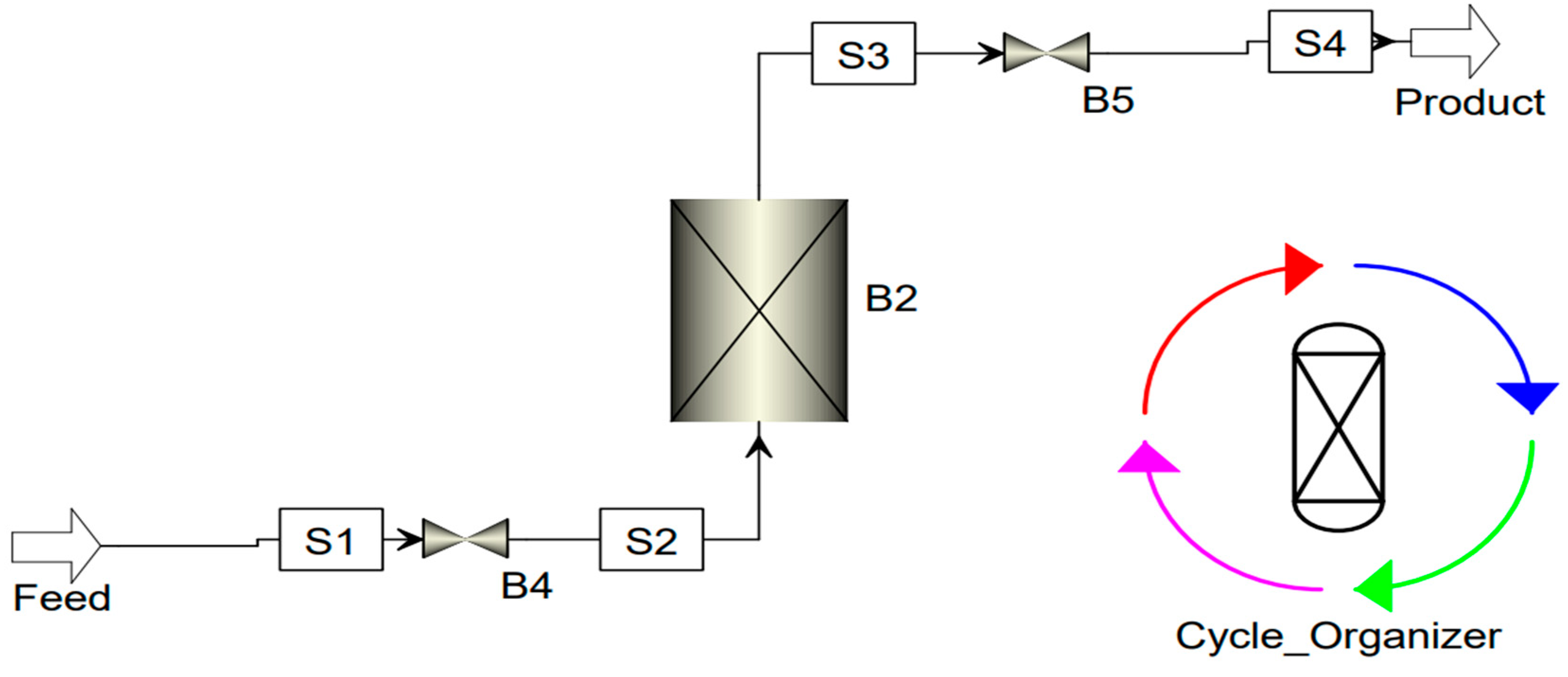

After settling all the parameters in the adsorption software, different specifications were made for the different steps in the cycle organizer in order to control the cycle. The simulation was run after putting all the inputs and making all the specifications to make a maximum of three cycles. Later on, two analyses were made together with a sensitivity analysis. Analysis of the adsorption bed performances and analysis of the composition of outlet stream.

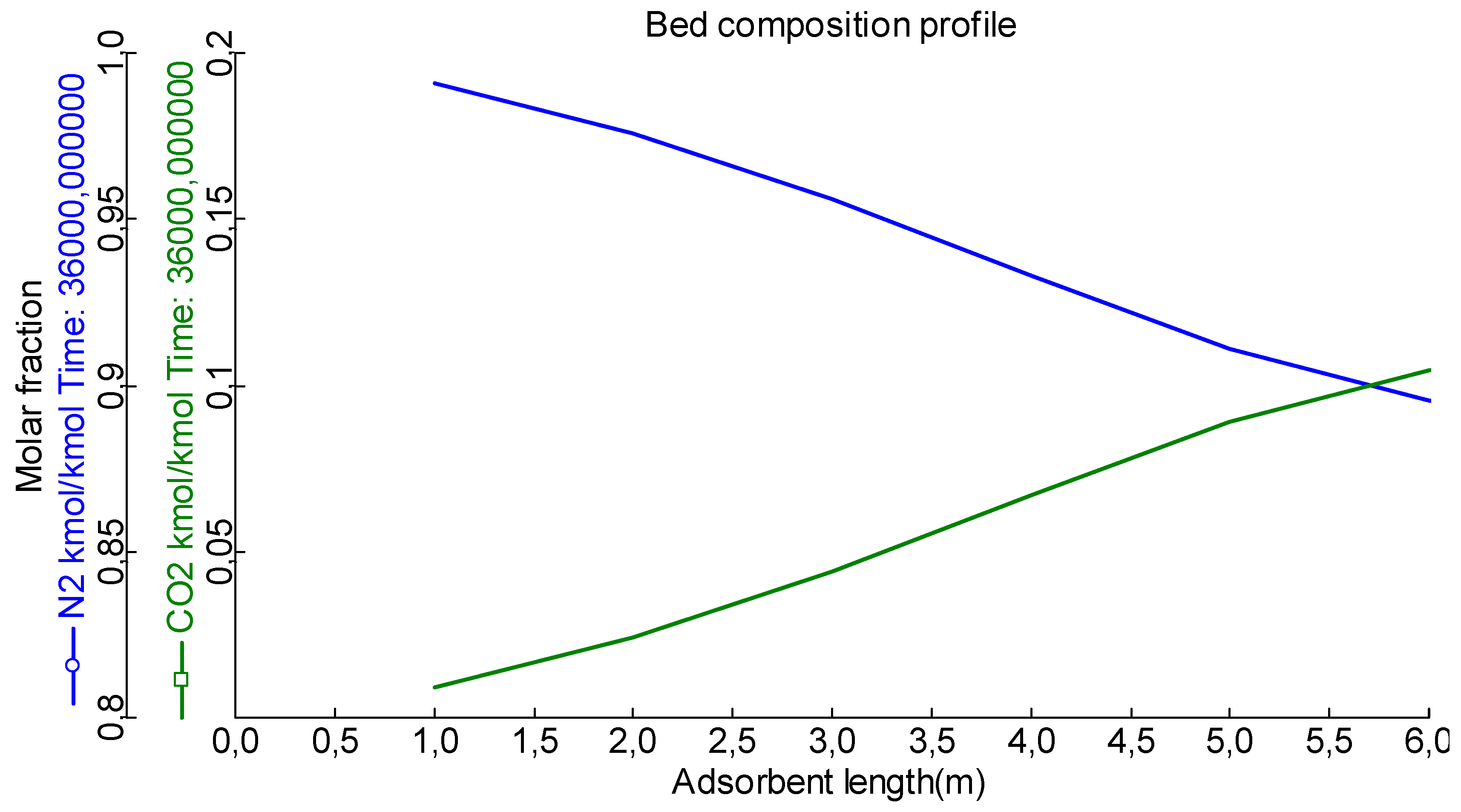

Analysing the breakthrough curve, it is possible to conclude that, the adsorption bed is capable of performing a continuous adsorption procedure for CO2 capture. This means that as the CO2-containing gas stream passes over the bed material, the CO2 molecules are preferentially captured and retained. The bed can continuously adsorb CO2 over an extended period of time without requiring frequent regeneration or replacement of the adsorbent material. This continuous adsorption process enables the efficient and continuous removal of CO2 from the gas stream, making the adsorption bed a viable solution for carbon capture and storage applications or other CO2 removal operations.

Figure 4.

Breakthrough curve.

Figure 4.

Breakthrough curve.

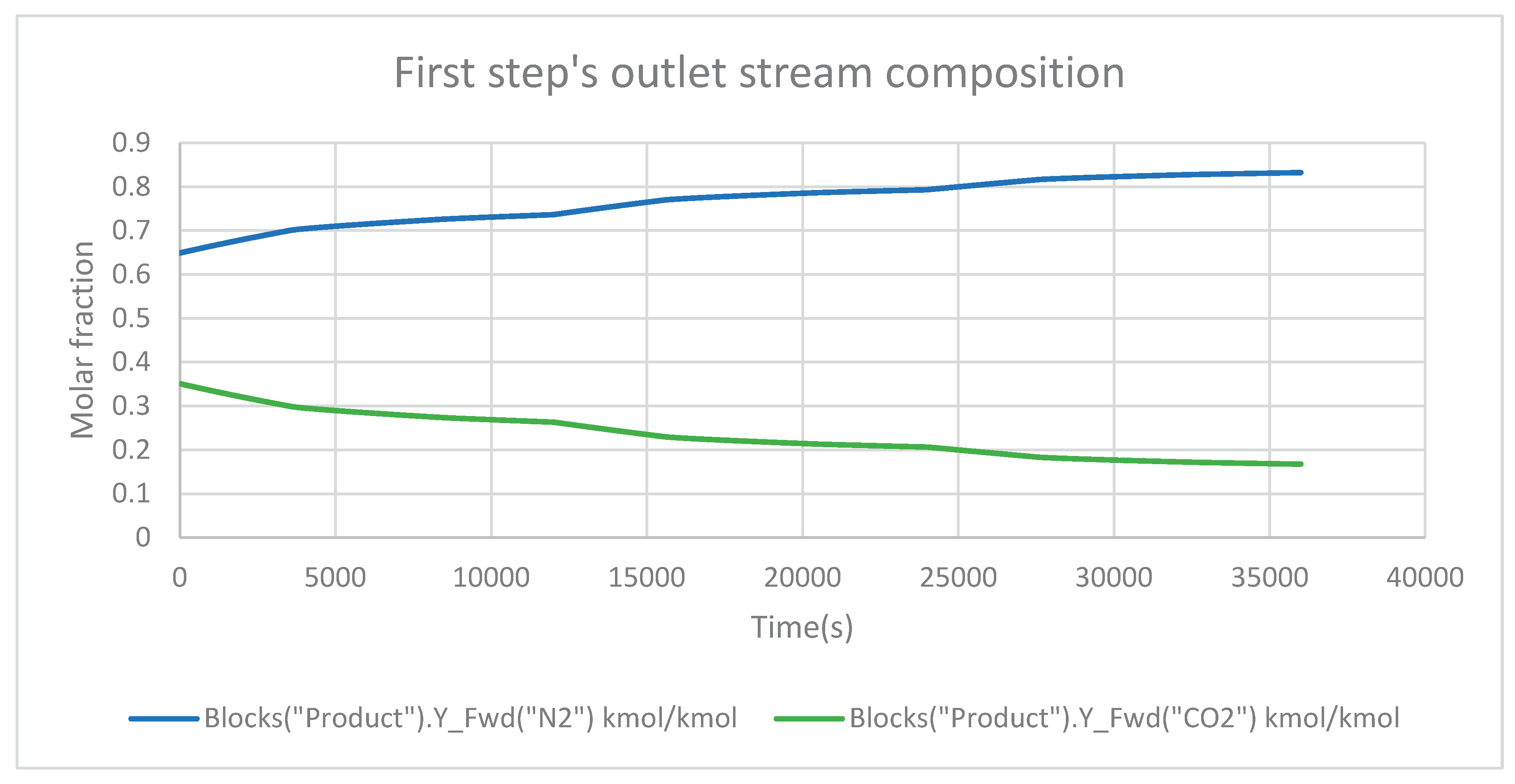

In

Figure 5, is shown the outlet stream composition of the first step (adsorption) of the cycle. Due to the effective adsorption process occurring within the bed, the mole fraction of CO

2 in the outlet stream gas is unusually low. The adsorption bed material selectively absorbs and holds CO

2 molecules as the gas stream passes through it, effectively eliminating them from the gas phase. Because of this excellent adsorption mechanism, only a tiny quantity of CO

2 molecules remains in the outflow stream. The bed maximizes separation efficiency through the continuous adsorption process by selectively adsorbing CO

2 while allowing other gases to pass through relatively unimpeded. This selectivity reduces the concentration of CO

2 in the outflow stream significantly, resulting in a very small mole fraction.

Unlike the relatively small mole fraction of CO2 in the outflow stream, the mole fraction of the remaining gas components increases continuously. This phenomenon results from selective CO2 adsorption within the bed, resulting in a relative enrichment of non-CO2 gases in the exit stream. As the CO2 molecules are selectively captured and retained by the adsorption bed, the gas stream that exits the bed contains a higher proportion of non-CO2 components. While the CO2 is successfully removed by the bed, the remaining gases flow through relatively un-adsorbed. This causes a progressive accumulation of non-CO2 gases, resulting in a rising mole fraction in the exit stream.

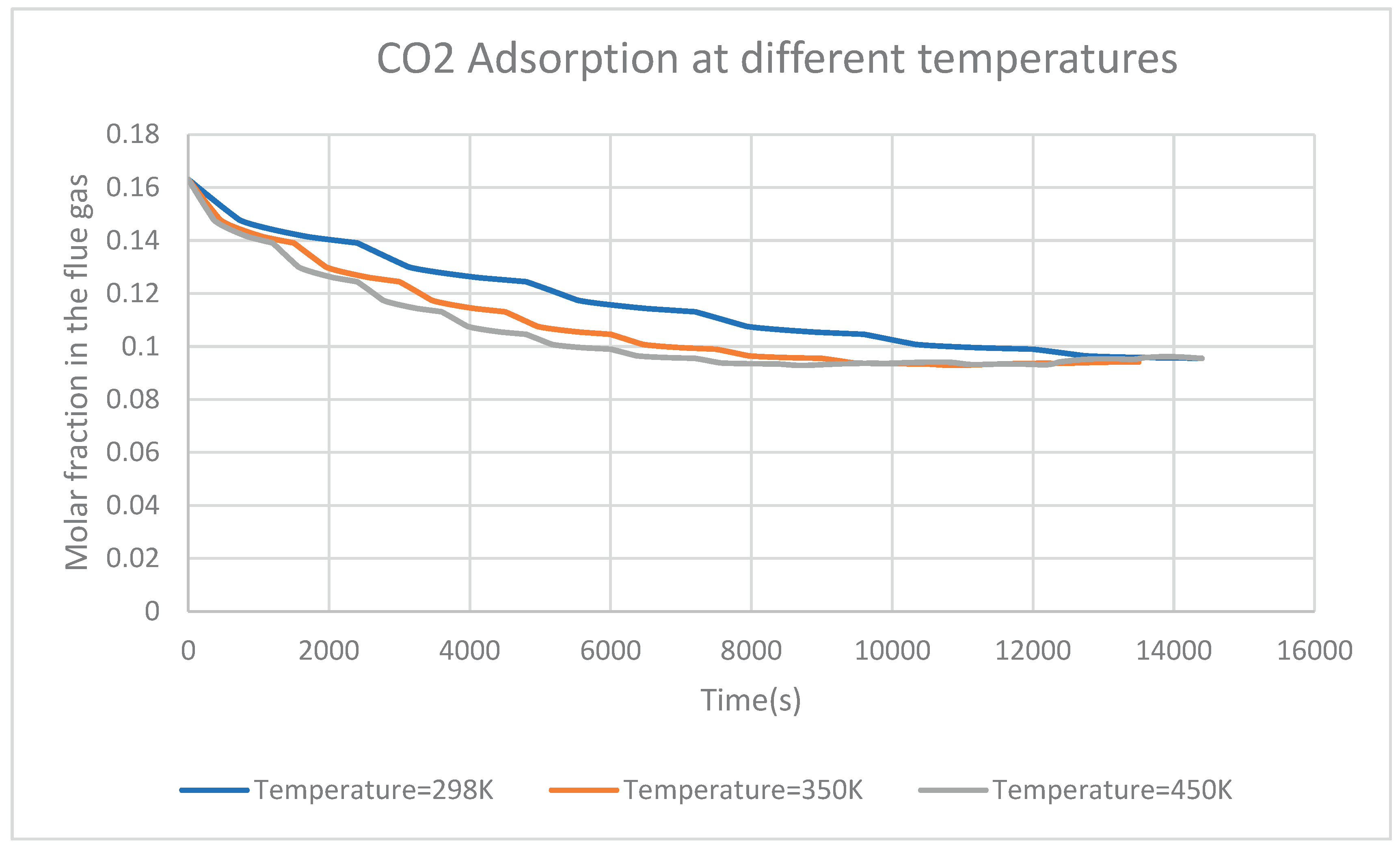

A sensitivity analysis was also made to see the effect of varying some parameters such as flue gas temperature, adsorption bed height and the flue gas flow rate. The initial temperature, flow rate of flue gas and bed height were respectively as follows: 298K, 8e-7kmol/s and 0.6m.

Figure 6 shows the CO

2 adsorption from the flue gas at three different temperatures. It may be observed that, increasing flue gas temperature results in an increase in CO

2 adsorption at a short time as the molar fraction of CO

2 decreases in the flue gas. Adsorption of CO

2 contained in a flue gas at high temperatures has the advantage of reducing time to reach the maximum of adsorption. With a temperature of 450K and 350K, the maximum adsorption is reached at about 9500 seconds while with a temperature of 298K, the maximum adsorption is reached at around 12400 seconds. Higher temperatures increase the kinetic energy of molecules, which can speed up adsorption. When a rapid adsorption process is needed, this can be advantageous. It is crucial to remember, however, that extremely high temperatures might cause desorption or thermal breakdown of the adsorbate, which can reduce overall adsorption effectiveness.

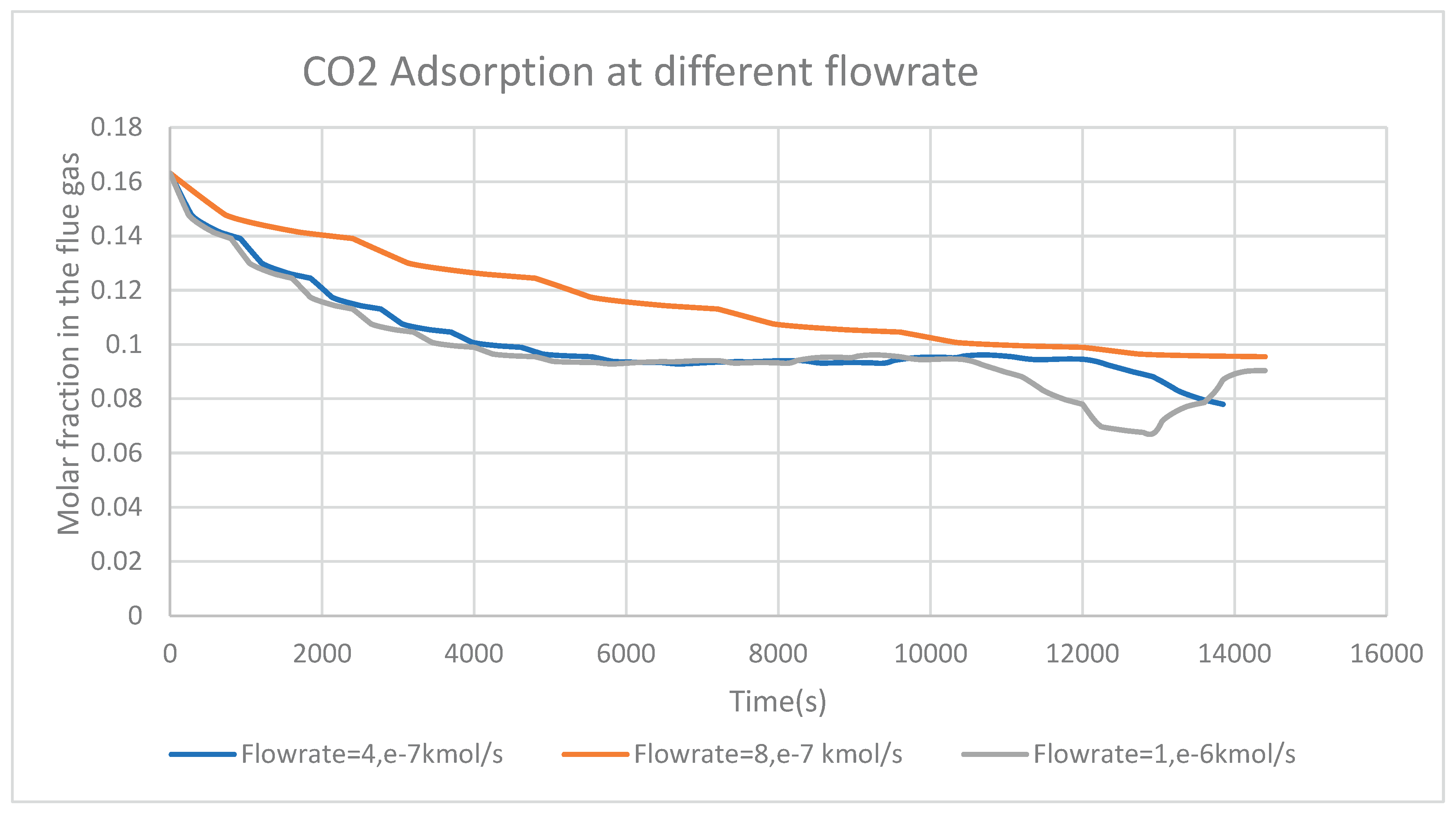

The flow rate of flue gas is also another parameter to consider.

Figure 7 demonstrates the adsorption of CO

2 at three different flue gas flow rates. In the considered figure, the two graphs corresponding to the adsorption of CO

2 from the flue gas at 4e-7kmol/s and 1e-6kmol/s are decreasing. This means that, there is more CO

2 adsorption at a flow rate of 4e-7 kmol/s and 1e-6 kmol/s compared to the remaining considered flow rate. In conclusion, at a temperature of 298K and an adsorption bed height of 0.6m (remember in this case, temperature and bed height were kept constant), the flow rates of 4e-7kmol/s and 1e-6kmol/s are more suitable for an effective rapid CO

2 in adsorption.

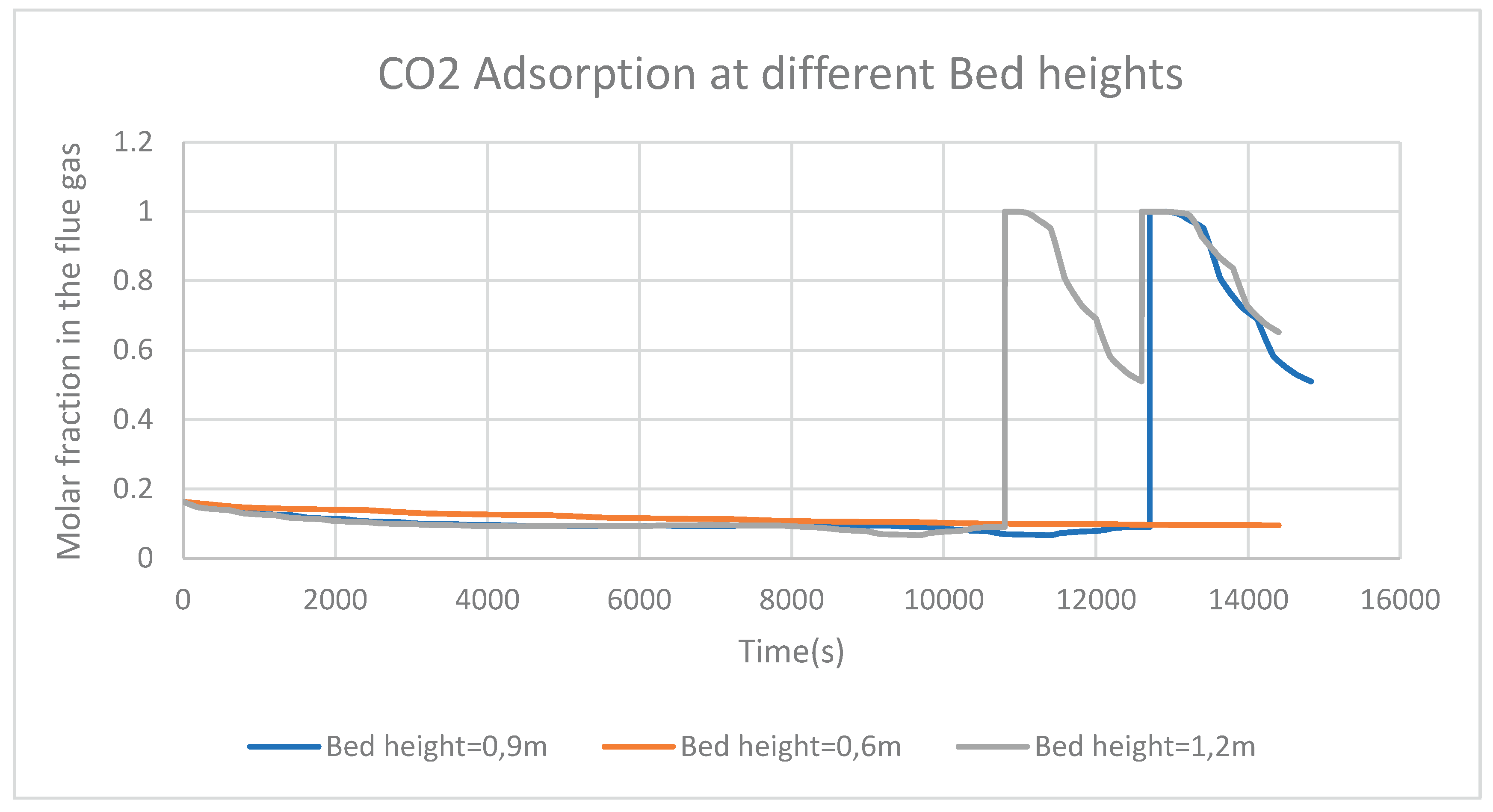

Figure 8 represents the CO

2 adsorption phenomenon at three different heights of the adsorption bed. It can be understood from the figure that, the height of the adsorption bed does not impact in general, the adsorption process for a short time process. However, when the flue gas takes more time in the adsorption column, it may be seen on the figure that, at a bed height of 0.9 meter and 1.2 meter, a sudden high rate of CO

2 adsorption takes place from time to time.

[

17] has found that decreasing the flow rate of input increases the time taken to achieve the maximum adsorption, increasing temperature decreases the time taken to reach the maximum value of adsorption and increasing the bed height increases also the time taken to achieve the maximum adsorption. As well, in this work, it was found that, increasing temperature reduces the time taken for maximum adsorption. However, an increase in flow rate does not have any relation with adsorption time, and the bed height variation also does not have effect on adsorption time. The similarity observed here is due to the fact that the temperature is more related to the reaction not generally to the input, adsorbent and adsorption column characteristics. It is common that, increasing temperature augments the reaction rate. The differences noticed may be due to the difference in adsorbate and adsorbent used in both cases.