1. Introduction

The prevalent method employed in mining, quarrying, and civil engineering projects to break down rocks is blasting. Only around 20-30% of the energy produced is utilised for the desired rock fragmentation, while the remaining energy is wasted on ground vibration, airblast, noise, flyrock, and backbreak. [

1,

2,

3,

4,

5,

6]. The severity of these undesirable effects results in human discomfort, endangers human safety, and destroys nearby structures and equipment within the blast zone. [

7,

8,

9]. Achieving an appropriate rock size is advantageous for reducing costs associated with loading, hauling, crushing, and grinding operations [

10,

11,

12,

13,

14]. Consequently, accurate forecasting of rock fragmentation and ground vibration plays a vital role in the mining industry. This enables the optimisation of the particle size distribution of the blasted rock and minimises the environmental impact caused by ground vibration.

Several methods are used for measuring fragmentation including sieve analysis, shovel loading rate, oversize boulder count and image analysis. Strain waves from a blast propagating as elastic waves at ground level are known as ground vibrations. Ground vibration is evaluated based on its frequency, acceleration, displacement, and peak particle velocity (PPV) [

15].

Blast impacts are typically influenced by two factors: controllable and uncontrollable parameters. Controllable parameters can be adjusted, such as blast design and explosive parameters. On the other hand, uncontrollable parameters cannot be modified, such as the geological and geotechnical properties of the rock [

16,

17,

18]. Researchers have developed various empirical methods to estimate rock fragmentation and ground vibration [

19,

20,

21,

22,

23,

24]. These models, however, face limitations due to their inability to incorporate the effects of additional parameters comprehensively. Typically, empirical methods rely on a limited set of input variables and produce a single output, resulting in reduced accuracy. This approach makes it challenging to simultaneously consider all the relevant parameters, especially given the complex and non-linear interrelationships among them.

As a result, various artificial intelligence methodologies have been adopted in numerous engineering studies, including blasting, to address the shortcomings associated with traditional empirical approaches [

25,

26,

27,

28,

29,

30,

31,

32,

33,

34]. Zhou et al.[

35] estimated the particle size distribution resulting from blasting operations by analysing 88 blasting datasets from two quarries located in Iran. They utilised several computational techniques, namely an adaptive neuro-fuzzy inference system (ANFIS) optimised with the firefly algorithm (FFA), genetic algorithm (GA), support vector regression (SVR), and artificial neural network (ANN). Among these models, the ANFIS-GA demonstrated superior predictive capabilities, achieving the highest coefficient of determination (

) value of 0.989 and the lowest root mean square error (RMSE) value of 0.974. Furthermore, Fang et al.[

36] proposed an approach for predicting rock fragmentation outcomes by combining the boosted generalised additive model (BGAM) with the firefly algorithm (FFA). This integrated FFA-BGAM framework was benchmarked against other soft computing approaches, including FFA-ANN, FFA-ANFIS, support vector machine (SVM), Gaussian process regression (GPR), and k-nearest neighbors (k-NN). The comparative analysis indicated that the FFA-BGAM method provided superior performance in forecasting rock fragmentation compared to the alternative models.

Huang et al. [

37] predicted rock fragmentation using auto-tuning model, called cat swarm optimisation (CSO) and particle swarm optimisation (PSO) algorithm. The input parameters considered for the study were spacing, burden, stemming, maximum charge per delay, rock mass rating, and specific charge. The CSO algorithm outperformed the PSO algorithm in estimating rock fragmentation with a RMSE of 0.847. Sensitivity analysis from the same study revealed that stemming had the most influence on fragmentation.

Amiri et al. [

38] introduced an integrated approach combining artificial neural network (ANN) and k-nearest neighbours (k-NN) algorithms for the simultaneous prediction of blast-induced ground vibrations and air overpressure. They evaluated the performance of this combined ANN-kNN framework against an individual ANN model and two conventional empirical formulas established by the United States Bureau of Mines (USBM). Their findings revealed that the proposed ANN-kNN hybrid model delivered enhanced predictive accuracy for both ground vibration and airblast, outperforming the other tested approaches. Zhou et al. [

39] employed Bayesian network (BN) and random forest (RF) methodologies to estimate ground vibrations induced by blasting, utilising data from 102 blasting operations. To enhance predictive accuracy by reducing the dataset dimensionality, a feature selection (FS) method was implemented, initially comprising eleven parameters. Subsequently, the FS approach identified five critical parameters, power factor, hole depth, maximum charge per delay, stemming, and distance from the blast face, as essential for accurate ground vibration predictions. Comparative analysis indicated that the RF model exhibited greater precision in forecasting ground vibrations than the BN model.

Yang et al. [

40] employed an adaptive neuro-fuzzy inference system (ANFIS) optimised by genetic algorithm (GA) and particle swarm optimisation (PSO) for predicting ground vibration. Their findings indicated that the ANFIS-GA variant achieved superior predictive performance, resulting in a significant 61% reduction in root mean square error (RMSE) and a 10% improvement in the coefficient of determination (

), compared to the conventional ANFIS approach.

Chandrahas et al.[

41] simultaneously predicted rock fragmentation and blast-induced ground vibrations utilising a dataset comprising 152 blast instances from Opencast mine I located at Ramagundam III Area of Singareni Collieries Company Limited, Telangana, India. They implemented several machine learning algorithms, including extreme gradient boosting (XGBoost),

k-nearest neighbors (

k-NN), and random forest (RF). Their study indicated that XGBoost outperformed the other models, demonstrating optimal values of mean absolute percentage error (MAPE) (22.5), RMSE (3.873), and

(0.9125) for fragmentation prediction, as well as MAPE (18.4), RMSE (2.8890), and

(0.9125) for ground vibration estimation. The inputs they analysed included spacing to burden ratio, maximum charge per delay, total explosive quantity, firing pattern, and joint angle degree. To the best of our knowledge, Chandrahas et al. [

41] is the only researcher who has made a simultaneous prediction of rock fragmentation and ground vibration. This work is closely compared with his, as it also considers the simultaneous prediction of blast-induced rock fragmentation and ground vibration. Therefore the main contributions of this paper are the following:

The research gathered a dataset comprising 120 blasting events, sourced from the blast records of the Jwaneng Diamond Mine in Botswana.

This work takes into account ten input variables, which include parameters related to blast design, explosive properties, and rock mass characteristics.

Three data-driven models are proposed for the simultaneous prediction of blast-induced rock fragmentation and ground vibration. These models are random forest (RF), ANN, and the ensemble ANN-RF.

We optimise the architecture of the best-performing machine learning model using the Monte Carlo method. And create a solution surface from the optimised machine-learning model.

Optimisation of input parameters to maximise fragmentation and minimise ground vibration is conducted using the gradient descent method from the created solution surface. The solution surface can be used for prediction, optimisation and finding the inverse solution by setting the desired value of fragmentation and ground vibration and searching in the solution space for the values of the corresponding input parameters.

Feature importance analysis is performed using the optimised random forest model and the results are confirmed from the created solution space.

2. Materials and Methods

This section explores the materials and methodologies employed in this study, focusing on the datasets collected from the Jwaneng Diamond Mine, the machine learning techniques applied, the feature importance analysis conducted, and the optimisation processes implemented.

2.1. Materials

A compilation of 120 blast datasets sourced from the mining records in Jwaneng has been used to train and test the models proposed in this research.

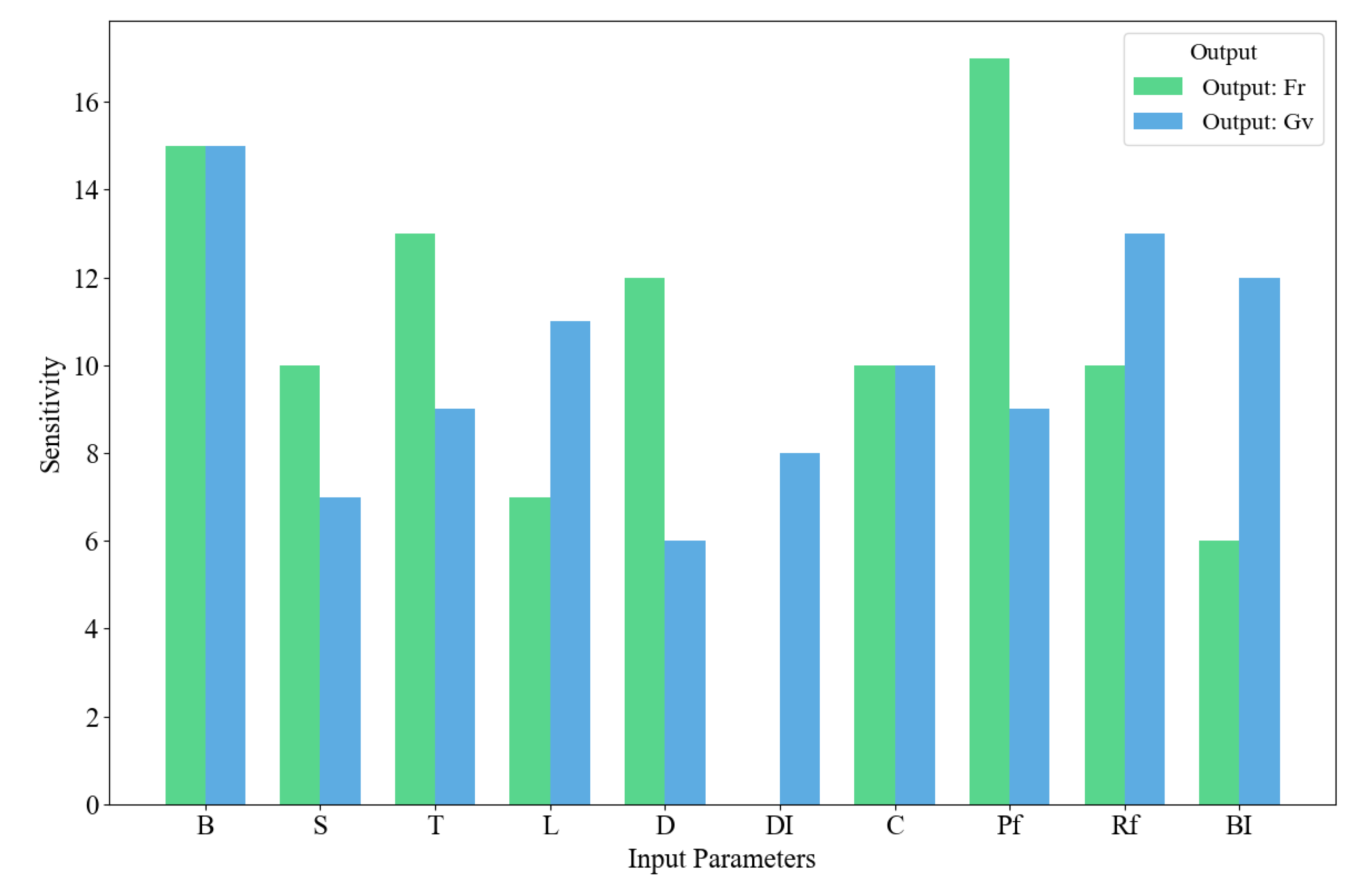

Figure 1 shows data collected from fragmentation images and seismographs. Split Desktop software was used to analyse the muckpile images captured with a digital camera, as shown in

Figure 1a, and to generate the particle size distribution (PSD) curve for fragmentation. The resulting PSD curve is presented in

Figure 1b. The quality of fragmentation at the mine is assessed based on 80% passing the 150 mm sieve size, less than 50 mm is considered undersize while above 150 mm is considered oversize. Ground vibration data in this study were recorded using seismographs placed at five different locations from the blast sources as shown in

Figure 1c. The seismographs measured ground vibrations in three orthogonal components: radial, transverse, and vertical.

Figure 1d shows a sample siesmograph report. The radial component captures vibrations in the direction of wave propagation from the blast source, the transverse component measures vibrations perpendicular to this direction within the horizontal plane, and the vertical component records vibrations in the up-and-down direction. Together, these three components provide a complete three-dimensional representation of ground motion, enabling accurate assessment of vibration intensity and directionality. The data used in the study span the period from 2017 to 2024, covering all blasting conditions and potential biases in these seven years. The parameters under consideration, along with their respective ranges, are outlined in

Table 1. The data was preprocessed which included data cleaning and normalisation. The dataset was then divided into a training set (80%) and a testing set (20%).

2.2. Methods

According to the literature, there is a consensus among researchers that ANNs are effective for predicting blast-induced impacts. However, Yan et al. [

42] highlighted their prolonged training times, while Jadav et al. [

43] emphasised their susceptibility to local minima. To address these challenges and enhance prediction accuracy, this study proposes am ensemble ANN-RF model. Additionally, standalone ANN and RF models are utilised for comparison purposes. The model assessment was conducted using RMSE and R2 as performance indices. Sensitivity analysis was performed using the network weights of the best-performing model. The gradient descent method was used to optimise the outputs, and the Monte Carlo method was applied to find the optimal architecture of the best-performing model.

2.2.1. ANN

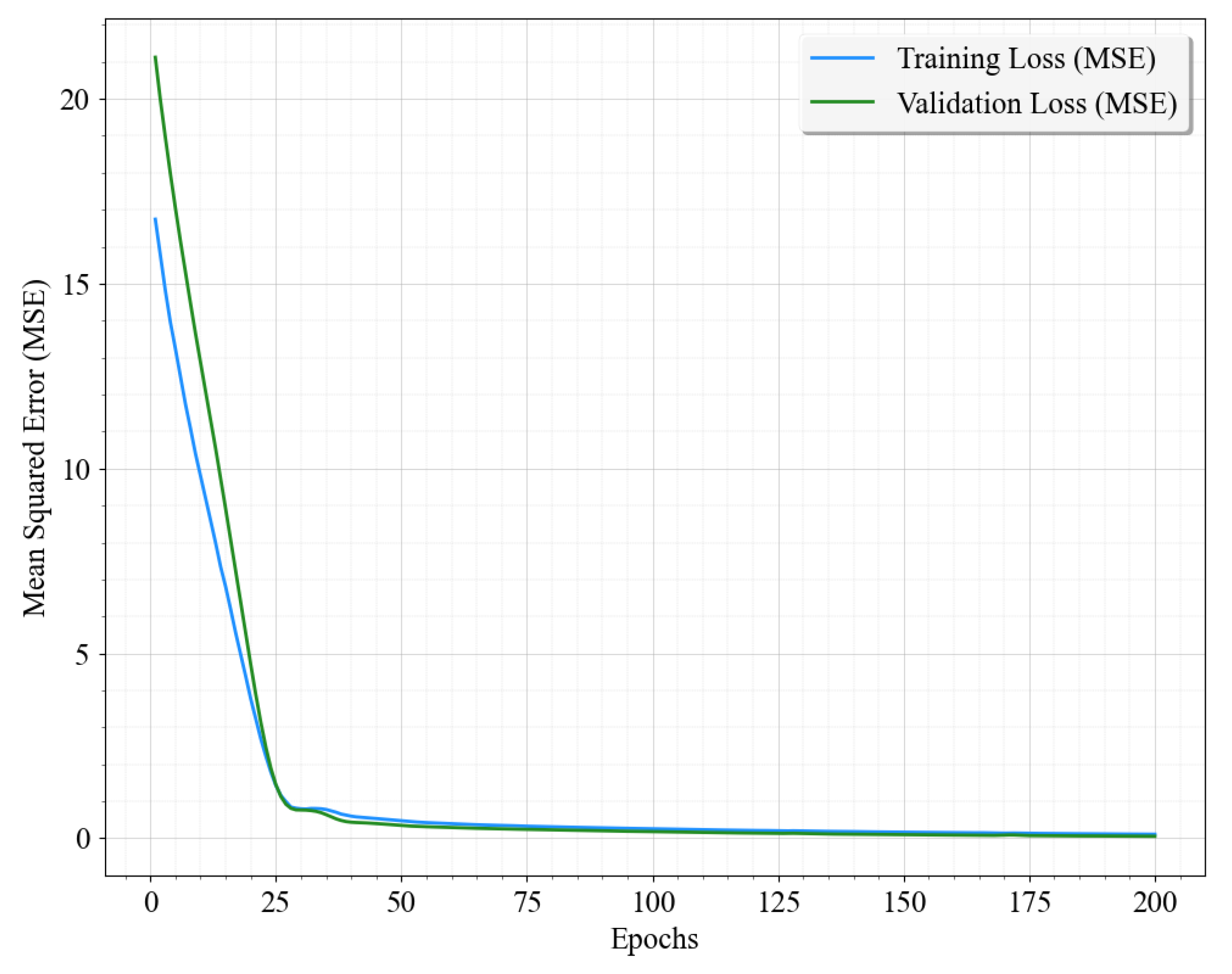

In this research, hyperparameters for an artificial neural network (ANN) model were optimised using the grid search technique. Hyperparameters selected for evaluation comprised learning rate values (0.001, 0.01, 0.1), configurations of hidden layers (20, 32, 64, 100, (50 50), (65 100), (25 75)), activation functions (rectified linear unit (RELU), hyperbolic tangent (tanh), sigmoid), batch sizes (32, 64), optimisers (Adam (adaptive moment estimation), stochastic gradient descent), and epoch counts (100, 200, 300). To facilitate adaptive ANN architectures capable of adjusting to varied hyperparameter combinations, a dynamic model generation function was created. The grid search was carried out utilising the GridSearchCV module from Scikit-learn, systematically testing all possible hyperparameter combinations. The dataset was partitioned into an 80% training set and a 20% testing set. For every hyperparameter set, the ANN was trained on the training subset and its predictive accuracy was validated against the testing subset to ensure robustness and generalisability. Model effectiveness was measured through loss metrics, and the hyperparameter combination that delivered the highest accuracy on the testing set was chosen as optimal. The loss trajectory for the optimal ANN configuration is presented in

Figure 2. It shows stable convergence behaviour, confirming effective learning without overfitting, as indicated by the close alignment of validation loss with training loss, demonstrating strong generalisation capabilities to new data.

2.2.2. RF

In this research, hyperparameter tuning of the random forest (RF) algorithm was carried out employing a random grid search method to enhance its predictive performance. The hyperparameters considered included the number of estimators (50, 100, 200, 300), maximum tree depth (10, 20, 30, None), the minimum number of samples needed to split a node (2, 5, 10), the minimum number of samples required at each leaf node (1, 2, 4), and the bootstrap sampling approach (bootstrap: True, False). A randomised combination of these hyperparameters was utilised, which allowed for computationally efficient parameter exploration compared to exhaustive grid search methods.

The RandomizedSearchCV functionality from Scikit-learn was implemented to execute this randomised search across 100 iterations. The dataset was divided into an 80% training subset and a 20% testing subset. Each hyperparameter combination was used to train the RF model on the training subset, and its predictive accuracy was assessed using the testing subset. Model evaluation was conducted using root mean squared error (RMSE) and the coefficient of determination (

) as performance criteria. The optimal hyperparameter set was identified based on achieving the lowest RMSE and the highest

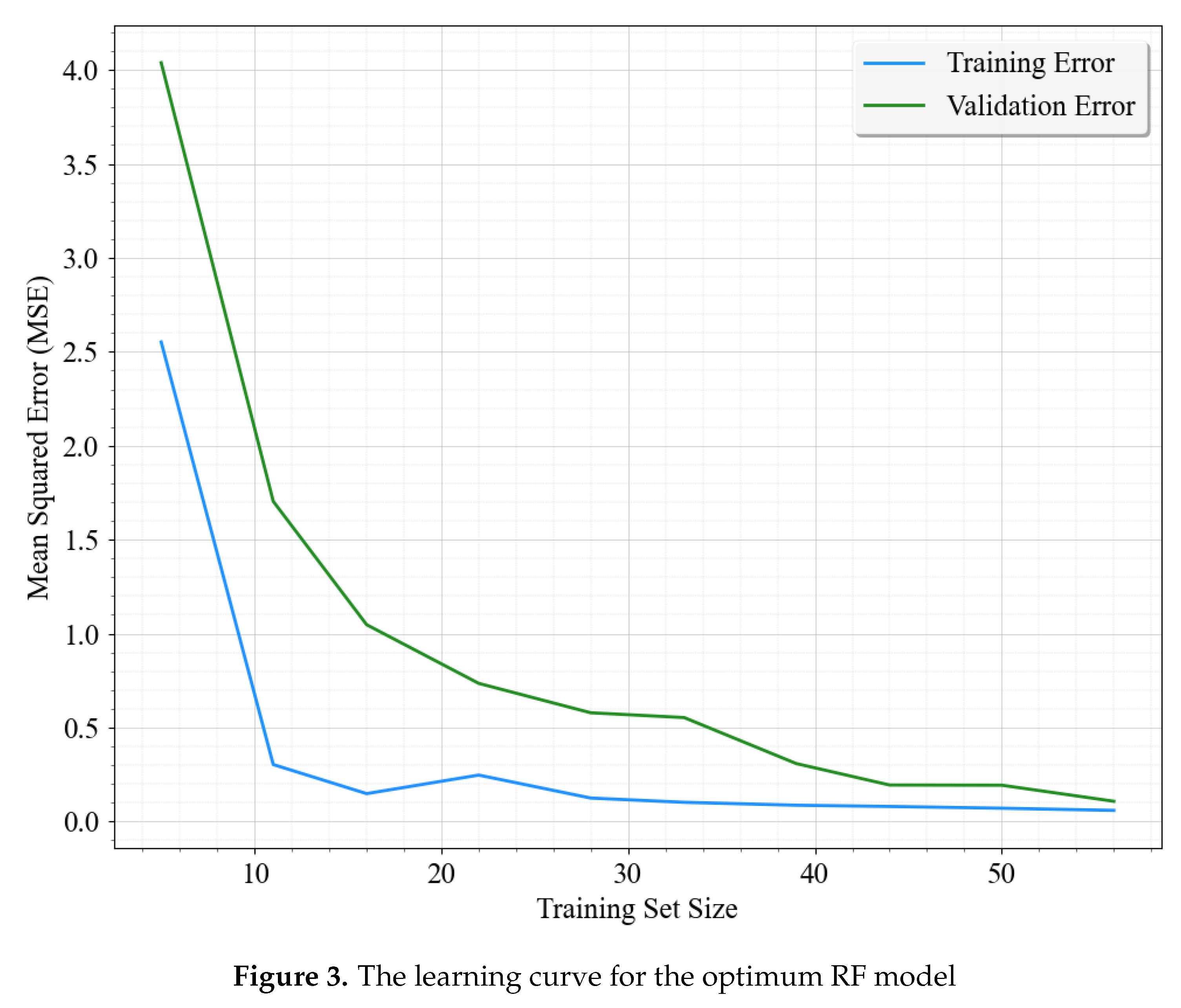

value on the test data. This strategy effectively balanced computational efficiency and thorough hyperparameter optimisation. The learning curve of the optimal RF configuration is depicted in

Figure 3, illustrating a distinct reduction in training and validation errors as the size of the training set increased. This trend confirms that augmenting the data volume enhances the predictive accuracy of the model. Additionally, the validation loss closely mirrors the decrease in training loss, signifying robust model generalisation.

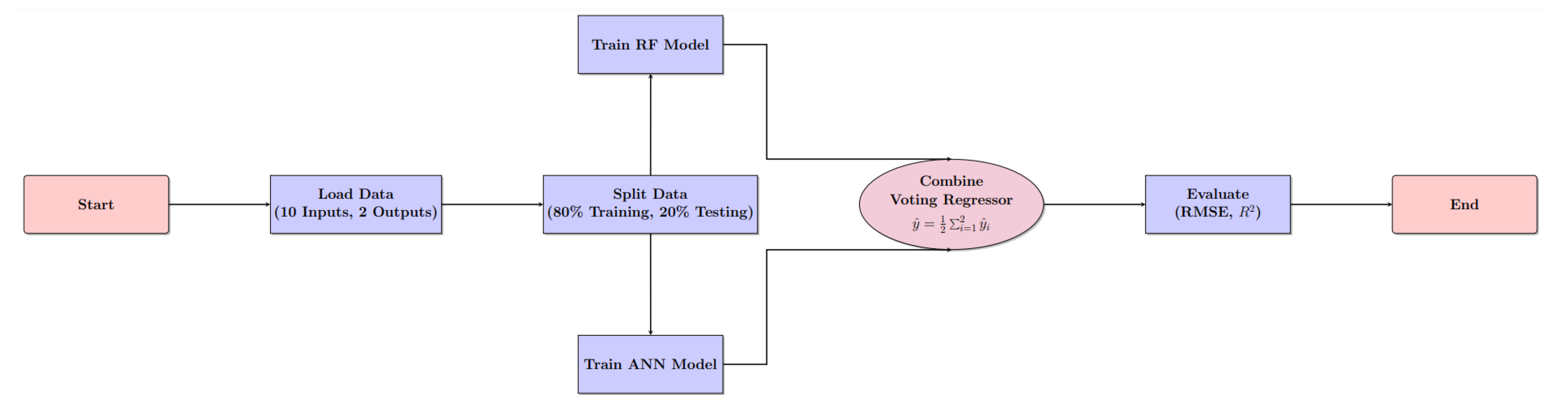

2.2.3. ANN-RF

In this study, an ensemble approach combining an ANN and RF was implemented, utilising the optimal parameters identified during independent hyperparameter tuning of the ANN and RF models. The optimal parameters for the ANN were the learning rate (0.01), number of neurons (64), activation function (RELU), batch size (32), optimiser (Adam), and the number of epochs (200). The optimal parameters for the RF model were the number of estimators (100), maximum depth (20), minimum samples required to split a node (5), minimum samples required to be at a leaf node (2), and the bootstrap method for sampling (bootstrap: True). Using the best parameters from both methods, an ensemble ANN-RF model was constructed. The ANN and RF models were trained separately, with their predictions combined using a voting regressor to achieve optimised regression outcomes. This approach leverages the strengths of both algorithms, with the voting regressor integrating their outputs to improve overall predictive performance. The combined model was trained on the training dataset, comprising 80% of the data, and evaluated on the testing dataset, comprising the remaining 20%. Model performance was assessed using RMSE and the R2 as performance metrics. The ensemble model leveraged the complementary strengths of the ANN for capturing complex feature representations and the RF for robust decision-making. The flowchart illustrating the ANN-RF method is shown in

Figure 4.

2.2.4. Feature Importance

In this study, a feature importance analysis was conducted to quantify the influence of each input parameter on the model outputs, namely ground vibration and rock fragmentation. The optimal RF model was employed due to its robustness, ability to capture nonlinear relationships, and inherent support for feature importance evaluation. Feature importance was computed using the mean decrease in impurity (MDI) method, which measures the average reduction in impurity, that is, the variance for regression introduced by each feature across all trees in the ensemble. The general formulation for computing the MDI-based feature importance

of input feature

is expressed in (

1):

In Equation (

1),

T denotes the total number of trees in the forest, and

represents the set of internal nodes in tree

t where feature

is used to split.

is the number of training samples reaching node

n, and

N is the total number of samples. The term

refers to the impurity reduction achieved by the split at node

n.

For regression problems, impurity is typically measured using variance. The impurity reduction

at a node can therefore be calculated as shown in (

2):

Here,

is the variance of the target variable at the parent node, while

and

are the variances of the left and right child nodes, respectively.

,

, and

represent the number of samples at the parent, left, and right nodes. This equation quantifies how much the split at a given node reduces the variance in the target variable, thereby contributing to the overall importance of the feature used in that split.

To enhance interpretability, the computed feature importances were normalised such that their values sum to 1. This allows each importance value to be expressed as a percentage of the total, enabling a clearer comparison of the relative contribution of each feature. Formally, the normalised feature importance

for feature

is computed as:

where

K is the total number of input features, and

is the raw feature importance obtained from Equation (

1). The normalised importances

sum to 100, making them suitable for percentage-based sensitivity comparisons, as illustrated in

Figure 6. This approach provides an intuitive and computationally efficient way to rank input variables based on their contribution to reducing prediction uncertainty. The resulting feature importances were used to interpret the model and guide further analysis.

2.2.5. Gradient Descent Optimisation

This study utilises gradient descent optimisation to determine the optimal values for fragmentation and ground vibration, along with their corresponding input parameters. The Monte Carlo method was applied to find the optimal model architecture, which was determined to be 10-60-45-2. The gradient descent method was employed to navigate the solution surface, maximising fragmentation while minimising ground vibration, thereby identifying the optimal input parameters. The specific technique employed for gradient descent is shown in (

4):

In this equation, represents the updated parameter at iteration , while is the current parameter value at iteration k. The term denotes the parameter value from the previous iteration. The learning rate is represented as . The function ANN−RF represents the ANN-RF model.

3. Results and Discussion

To check the performance of all the predictive models RMSE and R2 were utilised as performance indices. These are expressed by Equations (

5) and (

6):

where

y and

are the measured and predicted values, respectively;

and

are the mean measured and mean predicted values, respectively.

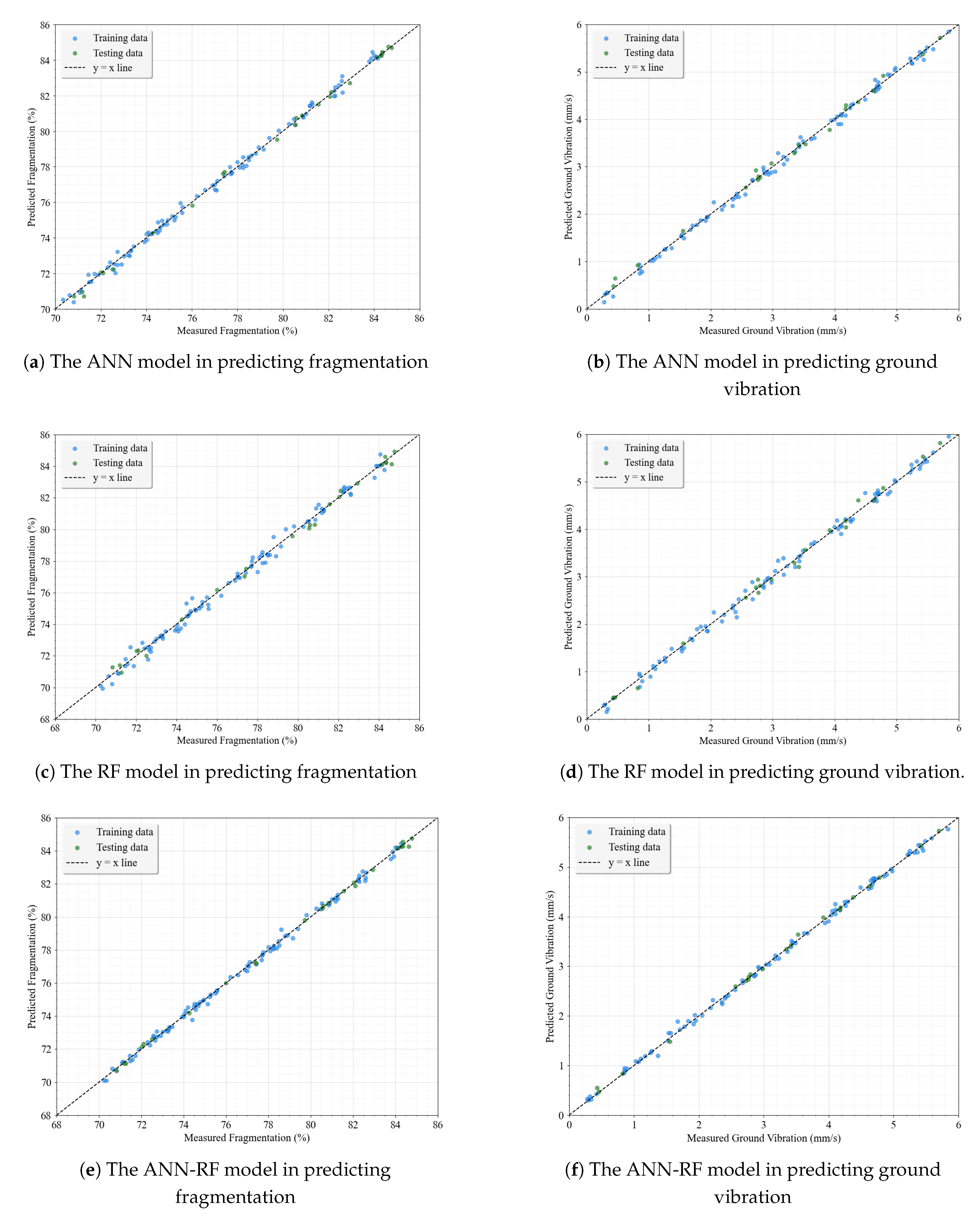

Results from the chosen models (ANN, RF, and ANN-RF) for estimating fragmentation and ground vibration, along with their performance indices, are outlined in tab-training,tab-testing for the training and testing set, respectively. The high accuracy and low error of the models in

Table 2 show that they have learned the data well, especially the ANN-RF model. Furthermore, the performance achieved on the test datasets, as presented in

Table 3, suggests that the developed models are well generalised. The ANN-RF model demonstrates superior performance on the testing set as well, as indicated by the following R2 values: 0.956 for fragmentation, and 0.930 for ground vibration. Additionally, the RMSE values are 0.315 for fragmentation, and 0.380 for ground vibration. These results suggest that the ANN-RF model achieves a lower system error and higher accuracy in simultaneously modelling fragmentation and ground vibration than all the other implemented models.

Figure 5a,f depict the predicted versus actual values of fragmentation and ground vibration for the models used in this study within the testing datasets. Generally, all the models demonstrate a high predictive accuracy, but

Figure 5e,f for ANN-RF model shows that the predicted values closely match the measured ones, following the ideal y:x line, which shows a strong correlation compared to other models. This confirms the effectiveness of the ANN-RF model in accurately predicting these outcomes. The superior performance of the ANN-RF hybrid model can be attributed to the complementary strengths of its components. The ANN (see

Figure 5a,b) outperformed the RF (see

Figure 5c,d) due to their ability to capture non-linear relationships and extract complex features through their layered architecture, which is particularly effective for datasets with intricate variable interactions like the dataset considered in this study. However, ANNs are prone to overfitting and lack interpretability, while RF excels in generalisation by handling structured patterns and mitigating overfitting through ensemble learning. The hybrid model leverages these advantages by using the ANN for feature extraction and the RF for robust decision-making, resulting in improved predictive accuracy. This enables the hybrid approach to address the limitations of each standalone model and achieve superior performance and robustness.

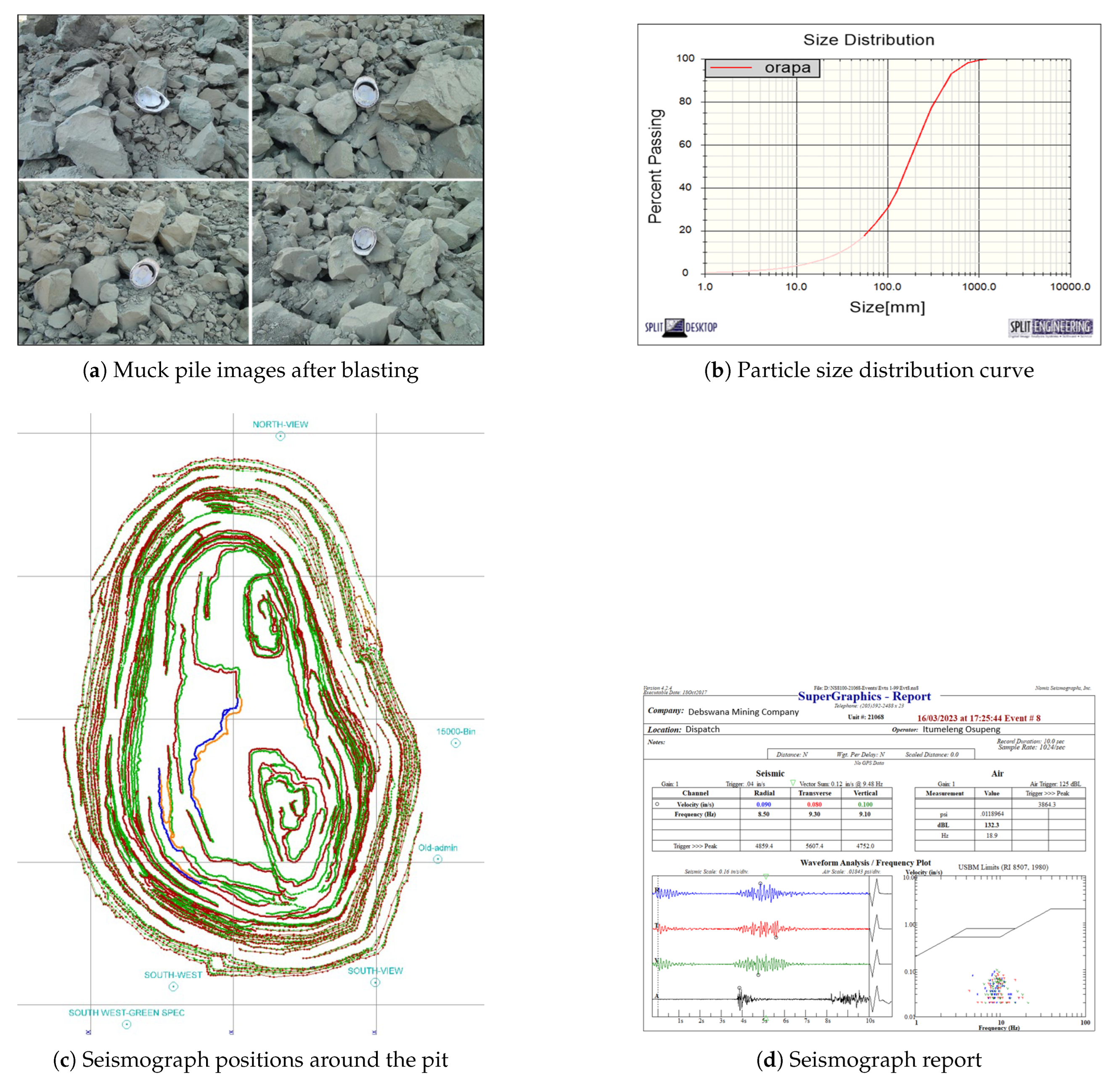

3.1. Feature Importance Analysis

Figure 6 illustrates the results of the sensitivity analysis conducted for both fragmentation and ground vibration. For fragmentation, powder factor (17%) emerges as the most influential input parameter. This finding underscores its critical role in determining the energy applied per unit volume of rock, which directly impacts the extent of breakage during blasting. Burden (15%) follows closely, reaffirming its importance in controlling the confinement and direction of explosive energy, both of which influence fragmentation outcomes. Other notably contributing factors include stemming and rock factor, indicating that both explosive confinement and rock mass characteristics significantly affect fragmentation. On the contrary, the blastability index, with a contribution of only 6%, was found to be the least influential parameter for fragmentation. This suggests that, within the context of this dataset, rock breakability characteristics play a secondary role compared to design-driven variables.

For ground vibration, the analysis identifies burden (15%) as the most impactful parameter. This highlights the burden’s key function in moderating explosive energy dissipation, where larger burdens can absorb more energy, thereby reducing the intensity of vibrations transmitted through the ground. Hole diameter (6%) is observed to have the least effect on ground vibration, indicating that either its variation is limited across the blast designs, or that its contribution is indirect and less significant compared to other parameters. Parameters such as maximum charge per delay, powder factor, and stemming also demonstrated moderate influence, suggesting their relevance across both performance metrics.

These results demonstrate that certain parameters, particularly powder factor and burden are critically influential in controlling both fragmentation and ground vibration, making them essential targets in blast design optimisation. In contrast, parameters such as blastability index and hole diameter may be of lesser priority, particularly under consistent geological conditions. These observations are consistent with findings from previous studies [

39,

44,

45,

46,

47,

48], which similarly report the dominant effects of explosive energy distribution and confinement on blast-induced outcomes.

Figure 6.

Sensitivity analysis results

Figure 6.

Sensitivity analysis results

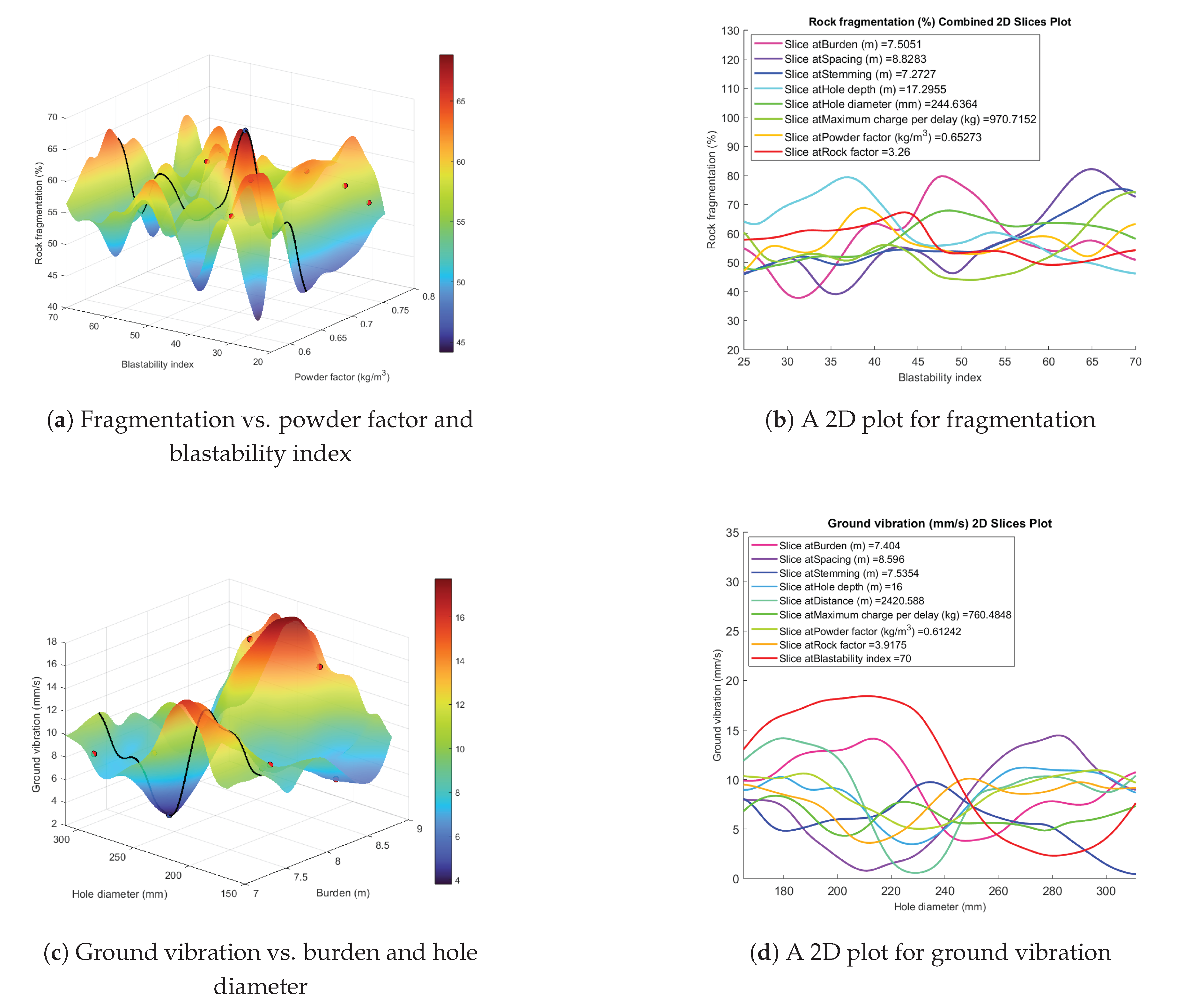

3.2. Analysis of the Optimisation Results

Figure 7a,b display the results of the optimisation procedure. In each figure, the red dots represent the randomly selected initial points, with seven such points chosen. Applying the gradient descent method to each initial point led to convergence at the optimal solution, depicted by the blue dot. The optimised values for fragmentation and ground vibration are approximately 84% and 0 mm/s, respectively.

Table 4 shows the optimised input parameters. Variations in optimised parameters are influenced by the model’s complexity, random initialisation, and interpolation errors. The model’s inherent complexity, with numerous interdependent variables and non-linear relationships, makes it sensitive to initial conditions, causing fluctuations in outcomes. Additionally, the random initialisation of network weights results in different starting points for each training run, leading to varied convergence paths and optimised parameters. Furthermore, interpolation errors arise from the grid resolution used to identify optimal points; the grid is not sufficiently fine, hence it misses more precise locations, resulting in inaccuracies in the final parameters.

From the sensitivity analysis, blastability index and hole diameter are the least influential input parameters on fragmentation and ground vibration, respectively. Because of this, we compare these parameters versus all the other input parameters kept constant, to observe the variations in the values of the output parameter in a two dimensional plot. We assign blastability index and hole diameter to be the x-axis, while ground vibration is assigned as the y-axis.

In

Figure 7a, when the powder factor increases while the blastability index is fixed, rock fragmentation value increases towards an optimal value then decreases with fluctuations. In

Figure 7c, increasing the hole diameter while keeping the burden fixed results in ground vibrations initially increasing then decreases to an optimal value before increasing again.

The solution space also confirms the results of the feature importance analysis. As can be seen in

Figure 7b, generated by varying blastability index which is the least influential input parameter on fragmentation and fixing all the other parameters, and taking a slice through the lowest, optimised point in the solution space. Powder factor is the most influential input parameter on fragmentation, and exhibits significant fluctuations over the blastability index range compared to other parameters.

Figure 7d, shows that burden has the most significant variations compared to other parameters, suggesting a higher sensitivity to ground vibration.

This multi-output optimisation of fragmentation and ground vibration has significant practical applications. It allows for the simultaneous consideration of these critical factors, enabling a balanced approach to blasting that enhances operational efficiency while minimising environmental impacts. By optimising fragmentation, mining operations can achieve the desired material size, which improves the efficiency of downstream processes like loading, hauling, and milling. At the same time, controlling ground vibration helps to reduce the risk of damage to nearby structures, ensures compliance with regulatory standards, and mitigates the environmental impact of blasting activities. This approach leads to more efficient and safer mining operations, ultimately contributing to cost savings, improved productivity, and reduced environmental footprint.

4. Conclusions

This study demonstrates the successful application of a hybrid machine learning technique to simultaneously predict and optimise blast-induced rock fragmentation and ground vibrations. The method was applied at the Debswana Jwaneng Diamond open-pit mine, utilising 10 input parameters. The evaluated models included ANN, RF, and the ensemble ANN-RF. Among these, the ANN-RF model proved to be the most effective, achieving the highest predictive accuracy on the test set, with values of 0.956 for fragmentation, 0.930 for ground vibration. Correspondingly, the RMSE values were 0.315 for fragmentation, 0.380 for ground vibration. The architecture of the ANN-RF model was optimised using the Monte Carlo method, resulting in an architecture with two hidden layers containing 60 and 45 neurons, respectively. The model was further refined using the gradient descent method to simultaneously minimise ground vibration (approximately 0 ) while maximising fragmentation (84%). Feature importance analysis revealed that powder factor (17%) was the most influential parameter for fragmentation, whereas the blastability index (6%) had the least impact. For ground vibration, burden (15%) emerged as the most significant factor, while hole diameter (6%) was the least influential. While this study focuses on the Jwaneng Diamond Mine, the methods used are scalable and adaptable to other mining operations. With site-specific data and model retraining, the approach can be applied to mines with varying topographical, geological, and operational conditions.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, O.S., and R.S.J.J.; methodology, O.S. and R.S.J.J.; software, O.S.; validation, O.S. and R.S.J.J.; formal analysis, O.S. and R.S.J.J.; writing—original draft preparation, O.S.; writing—review and editing, O.S., R.S.S., R.S.J.J., and O.M.; project; supervision, R.S.S., R.S.J.J., and O.M.; project administration, R.S.J.J.; funding acquisition, R.S.J.J. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by Debswana Diamond Company with grant number P00064. The APC was funded by Debswana.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets analysed during this study are not available to the public because of a non-disclosure agreement signed with Debswana Mining Company.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Jwaneng Diamond Mine for supplying the data for this research. Special appreciation is extended to Thuso Mogotsi, Chite Joe Matenga and Ethna Kasitiko for their valuable contributions to this work.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- An, H.; Song, Y.; Liu, H.; Han, H. Combined finite-discrete element modelling of dynamic rock fracture and fragmentation during mining production process by blast. Shock and Vibration 2021, 2021, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, Z.; Shi, X.; Zhou, J.; Chen, X.; Qiu, X. Effective assessment of blast-induced ground vibration using an optimized random forest model based on a Harris hawks optimization algorithm. Applied Sciences 2020, 10, 1403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keshtegar, B.; Hasanipanah, M.; Bakhshayeshi, I.; Sarafraz, M.E. A novel nonlinear modeling for the prediction of blast-induced airblast using a modified conjugate FR method. Measurement 2019, 131, 35–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Temeng, V.A.; Ziggah, Y.Y.; Arthur, C.K. Blast-induced noise level prediction model based on brain inspired emotional neural network. Journal of Sustainable Mining 2021, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trivedi, R.; Singh, T.; Gupta, N. Prediction of blast-induced flyrock in opencast mines using ANN and ANFIS. Geotechnical and Geological Engineering 2015, 33, 875–891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shirani Faradonbeh, R.; Monjezi, M.; Jahed Armaghani, D. Genetic programing and non-linear multiple regression techniques to predict backbreak in blasting operation. Engineering with computers 2016, 32, 123–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khandelwal, M.; Singh, T. Evaluation of blast-induced ground vibration predictors. Soil Dynamics and Earthquake Engineering 2007, 27, 116–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nateghi, R.; Kiany, M.; Gholipouri, O. Control negative effects of blasting waves on concrete of the structures by analyzing of parameters of ground vibration. Tunnelling and Underground Space Technology 2009, 24, 608–616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hajihassani, M.; Armaghani, D.J.; Sohaei, H.; Mohamad, E.T.; Marto, A. Prediction of airblast-overpressure induced by blasting using a hybrid artificial neural network and particle swarm optimization. Applied Acoustics 2014, 80, 57–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jahed Armaghani, D.; Hasanipanah, M.; Tonnizam Mohamad, E. A combination of the ICA-ANN model to predict air-overpressure resulting from blasting. Engineering with Computers 2016, 32, 155–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monjezi, M.; Rezaei, M.; Varjani, A.Y. Prediction of rock fragmentation due to blasting in Gol-E-Gohar iron mine using fuzzy logic. International Journal of Rock Mechanics and Mining Sciences 2009, 46, 1273–1280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karami, A.; Afiuni-Zadeh, S. Sizing of rock fragmentation modeling due to bench blasting using adaptive neuro-fuzzy inference system and radial basis function. International Journal of Mining Science and Technology 2012, 22, 459–463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shams, S.; Monjezi, M.; Majd, V.J.; Armaghani, D.J. Application of fuzzy inference system for prediction of rock fragmentation induced by blasting. Arabian Journal of Geosciences 2015, 8, 10819–10832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bahrami, A.; Monjezi, M.; Goshtasbi, K.; Ghazvinian, A. Prediction of rock fragmentation due to blasting using artificial neural network. Engineering with computers 2011, 27, 177–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dumakor-Dupey, N.K.; Arya, S.; Jha, A. Advances in blast-induced impact prediction—A review of machine learning applications. Minerals 2021, 11, 601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khandelwal, M.; Kankar, P. Prediction of blast-induced air overpressure using support vector machine. Arabian Journal of Geosciences 2011, 4, 427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, T.; Dontha, L.; Bhardwaj, V. Study into blast vibration and frequency using ANFIS and MVRA. Mining Technology 2008, 117, 116–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khandelwal, M.; Singh, T. Application of an expert system to predict maximum explosive charge used per delay in surface mining. Rock mechanics and rock engineering 2013, 46, 1551–1558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Persson, P.A.; Holmberg, R.; Lee, J. Rock Blasting and Explosives Engineering; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Mishnaevsky, L.; Schmauder, S. Analysis of rock fragmentation with the use of the theory of fuzzy sets. In Proceedings of the ISRM International Symposium-EUROCK 96. OnePetro; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Ragam, P.; Nimaje, D. Assessment of blast-induced ground vibration using different predictor approaches-a comparison. Chemical Engineering Transactions 2018, 66, 487–492. [Google Scholar]

- Hustrulid, W.A. Blasting Principles for Open Pit Mining, Volume 1: General Design Concepts; A.A. Balkema: Rotterdam, Netherlands, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Ghosh, A.; Daemen, J.J. A simple new blast vibration predictor (based on wave propagation laws). In

Proceedings of the ARMA US Rock Mechanics/Geomechanics Symposium. ARMA, 1983, pp. ARMA–83.

- Langefors, U.; Kihlström, B. The Modern Technique of Rock Blasting; John Wiley and Sons: New York, 1963. [Google Scholar]

- Kaklis, K.; Saubi, O.; Jamisola, R.; Agioutantis, Z. Machine Learning Prediction of the Load Evolution in Three-Point Bending Tests of Marble. Mining, Metallurgy & Exploration 2022, 39, 2037–2045. [Google Scholar]

- Kaklis, K.; Saubi, O.; Jamisola, R.; Agioutantis, Z. A preliminary application of a machine learning model for the prediction of the load variation in three-point bending tests based on acoustic emission signals. Procedia Structural Integrity 2021, 33, 251–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saubi, O.; Gaopale, K.; Jamisola, R.S.; Suglo, R.S.; Matsebe, O. Enhancing Blast Design Efficiency for Rock Fragmentation with Gradient Descent and Artificial Neural Networks: An Optimization Study. In Proceedings of the 2023 4th International Conference on Computers and Artificial Intelligence Technology (CAIT). IEEE; 2023; pp. 1–5. [Google Scholar]

- Saubi, O.; Jamisola Jr, R.S.; Gaopale, K.; Suglo, R.S.; Matsebe, O. A Solution Surface in Nine-Dimensional Space to Optimise Ground Vibration Effects Through Artificial Intelligence in Open-Pit Mine Blasting. Mining 2025, 5, 40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petso, T.; Jamisola Jr, R.S.; Mpoeleng, D.; Bennitt, E.; Mmereki, W. Automatic animal identification from drone camera based on point pattern analysis of herd behaviour. Ecological Informatics 2021, 66, 101485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xue, X.; Yang, X.; Li, P. Evaluation of ground vibration due to blasting using fuzzy logic. Geotechnical and Geological Engineering 2017, 35, 1231–1237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bamford, T.; Esmaeili, K.; Schoellig, A.P. A deep learning approach for rock fragmentation analysis. International Journal of Rock Mechanics and Mining Sciences 2021, 145, 104839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monjezi, M.; Bahrami, A.; Varjani, A.Y. Simultaneous prediction of fragmentation and flyrock in blasting operation using artificial neural networks. International journal of rock mechanics and mining sciences 2010, 47, 476–480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sayadi, A.; Monjezi, M.; Talebi, N.; Khandelwal, M. A comparative study on the application of various artificial neural networks to simultaneous prediction of rock fragmentation and backbreak. Journal of Rock Mechanics and Geotechnical Engineering 2013, 5, 318–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zihan, Z.; Xiaosheng, L.; Lijun, W.; Guangqiu, H. Prediction of Blast-induced Ground Vibration using Eight New Intelligent Models. IAENG International Journal of Computer Science 2024, 51. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, J.; Li, C.; Arslan, C.A.; Hasanipanah, M.; Bakhshandeh Amnieh, H. Performance evaluation of hybrid FFA-ANFIS and GA-ANFIS models to predict particle size distribution of a muck-pile after blasting. Engineering with computers 2021, 37, 265–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, Q.; Nguyen, H.; Bui, X.N.; Nguyen-Thoi, T.; Zhou, J. Modeling of rock fragmentation by firefly optimization algorithm and boosted generalized additive model. Neural Computing and Applications 2021, 33, 3503–3519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, J.; Asteris, P.G.; Manafi Khajeh Pasha, S.; Mohammed, A.S.; Hasanipanah, M. A new auto-tuning model for predicting the rock fragmentation: a cat swarm optimization algorithm. Engineering with Computers 2020, pp. 1–12. [Google Scholar]

- Amiri, M.; Bakhshandeh Amnieh, H.; Hasanipanah, M.; Mohammad Khanli, L. A new combination of artificial neural network and K-nearest neighbors models to predict blast-induced ground vibration and air-overpressure. Engineering with Computers 2016, 32, 631–644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, J.; Asteris, P.G.; Armaghani, D.J.; Pham, B.T. Prediction of ground vibration induced by blasting operations through the use of the Bayesian Network and random forest models. Soil Dynamics and Earthquake Engineering 2020, 139, 106390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, H.; Hasanipanah, M.; Tahir, M.; Bui, D.T. Intelligent prediction of blasting-induced ground vibration using ANFIS optimized by GA and PSO. Natural Resources Research 2020, 29, 739–750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chandrahas, N.S.; Choudhary, B.S.; Teja, M.V.; Venkataramayya, M.; Prasad, N.K. XG boost algorithm to simultaneous prediction of rock fragmentation and induced ground vibration using unique blast data. Applied Sciences 2022, 12, 5269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, Y.; Hou, X.; Fei, H. Review of predicting the blast-induced ground vibrations to reduce impacts on ambient urban communities. Journal of cleaner production 2020, 260, 121135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jadav, K.; Panchal, M. Optimizing weights of artificial neural networks using genetic algorithms. Int J Adv Res Comput Sci Electron Eng 2012, 1, 47–51. [Google Scholar]

- Qiu, Y.; Zhou, J.; Khandelwal, M.; Yang, H.; Yang, P.; Li, C. Performance evaluation of hybrid WOA-XGBoost, GWO-XGBoost and BO-XGBoost models to predict blast-induced ground vibration. Engineering with Computers 2021, pp. 1–18. [Google Scholar]

- Tiile, R.N. Artificial Neural Network Approach to Predict Blast-induced Ground Vibration, Airblast and Rock Fragmentation. Master’s thesis, Missouri University of Science and Technology, Rolla, Missouri, 2016.

- Monjezi, M.; Amiri, H.; Farrokhi, A.; Goshtasbi, K. Prediction of rock fragmentation due to blasting in Sarcheshmeh copper mine using artificial neural networks. Geotechnical and Geological Engineering 2010, 28, 423–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monjezi, M.; Mohamadi, H.A.; Barati, B.; Khandelwal, M. Application of soft computing in predicting rock fragmentation to reduce environmental blasting side effects. Arabian Journal of Geosciences 2014, 7, 505–511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, J.; Asteris, P.G.; Manafi Khajeh Pasha, S.; Mohammed, A.S.; Hasanipanah, M. A new auto-tuning model for predicting the rock fragmentation: a cat swarm optimization algorithm. Engineering with Computers 2022, pp. 1–12. [Google Scholar]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).