Submitted:

04 July 2025

Posted:

07 July 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Population and Sample Definition

2.2. Data Collection

2.3. Cardiovascular and Atherosclerotic Risk Assessment

2.4. Biochemical and Metabolic Assessments

2.5. Ultrasound Examination

2.6. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Patient Clinical Characteristics

3.2. Cardiovascular Risk Assessment and Metabolic Indices

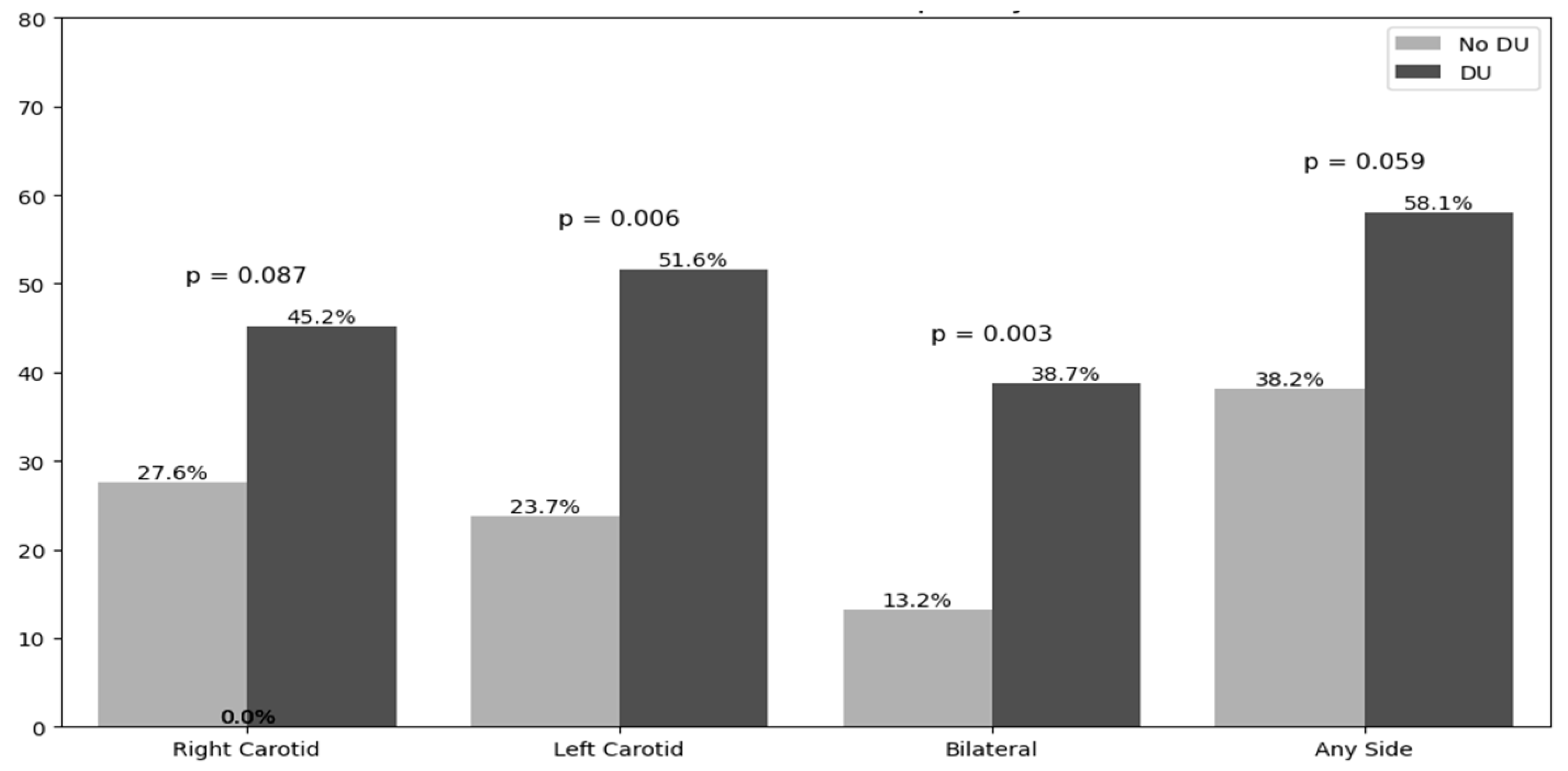

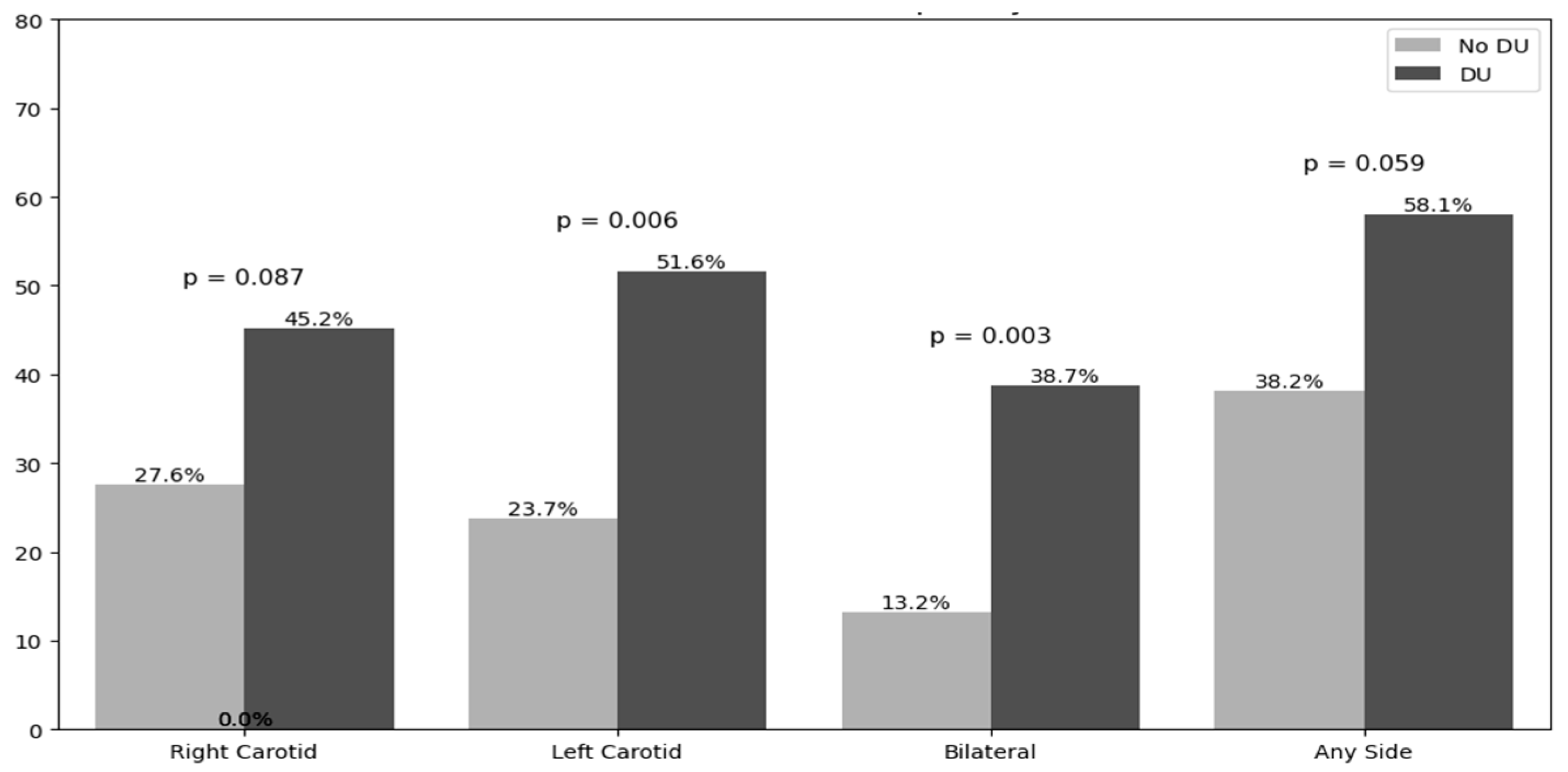

3.3. Carotid Ultrasound Findings

3.4. Doppler Hemodynamic Parameters

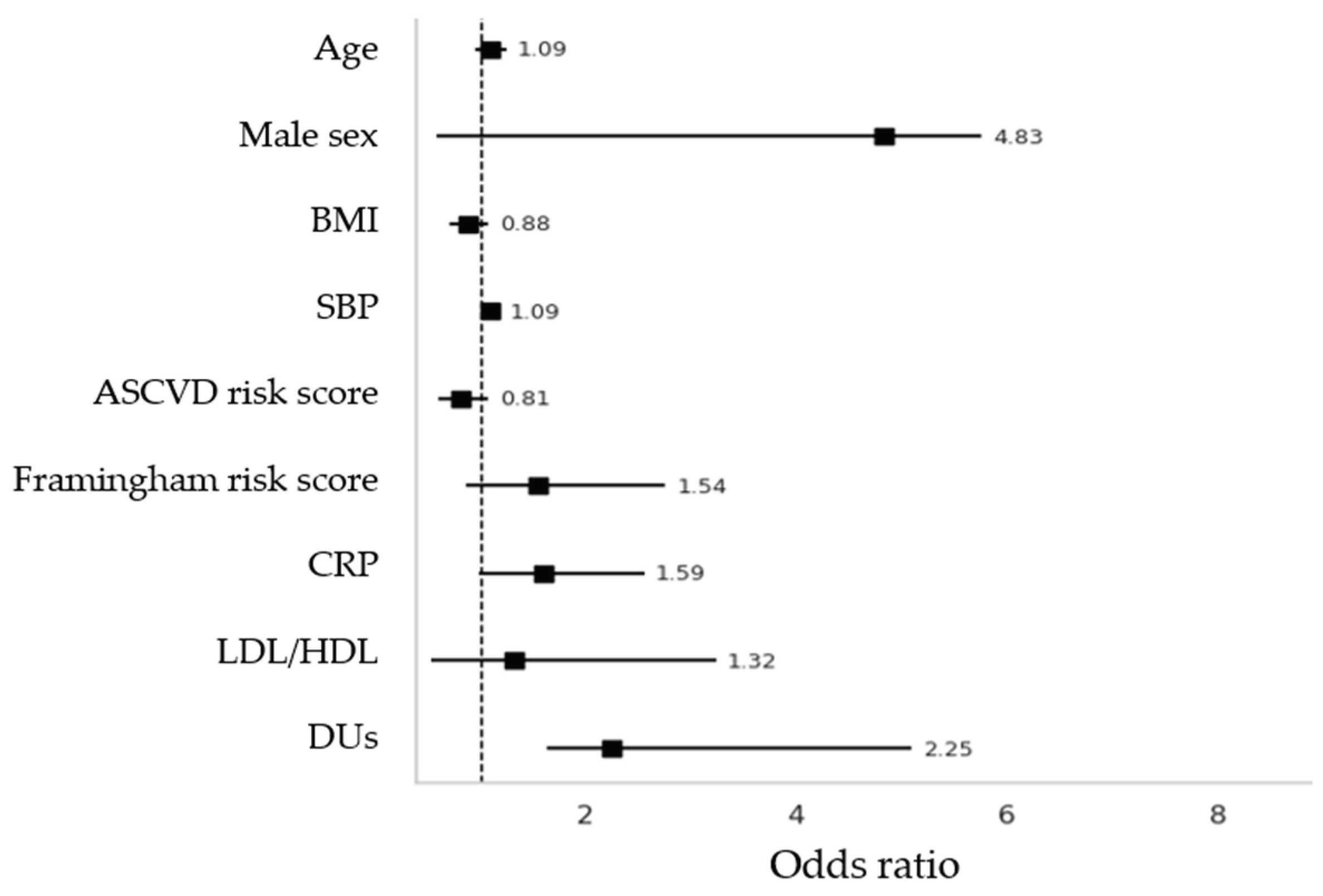

3.5. Regression Analyses

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| 95%CI | 95% Confidence Interval |

| ACA | Anti-Centromere Antibodies |

| ACC/AHA | American College of Cardiology / American Heart Association |

| ACEis | Angiotensin-Converting Enzyme Inhibitors |

| ACR/EULAR | American College of Rheumatology / European League Against Rheumatism |

| AIP | Atherogenic Index of Plasma |

| ARA | Anti-RNA Polimerase III Antibodies |

| ARBs | Angiotensin II Receptor Blockers |

| ASCVD | Atherosclerotic Cardiovascular Disease |

| ASST | Azienda Socio-Sanitaria Territoriale |

| β-coeff. | Beta Coefficient |

| β-stand | Standardized Beta Coefficient |

| BMI | Body Mass Index |

| BSA | Body Surface Area |

| CCA | Common Carotid Artery |

| CCBs | Calcium Channel Blockers |

| cIMT | Carotid Intima-Media Thickness |

| cMRI | Cardiac Magnetic Resonance Imaging |

| CRP | C-Reactive Protein |

| DBP | Diastolic Blood Pressure |

| DUs | Digital Ulcers |

| ECA | External Carotid Artery |

| EDV | End-Diastolic Velocity |

| ERAs | Endothelin Receptor Antagonists |

| GIRRCS | Gruppo Italiano per la Ricerca e la Ricerca Clinica sulla Sclerodermia |

| HDL | High-Density Lipoprotein |

| HOMA-IR | Homeostatic Model Assessment of Insulin Resistance |

| HR | Heart Rate |

| HRCT | High-Resolution Computed Tomography |

| hs-TnT | High-Sensitivity Troponin T |

| ICA | Internal Carotid Artery |

| ILD | Interstitial Lung Disease |

| IMT | Intima-Media Thickness |

| IQR | Interquartile Range |

| LDL | Low-Density Lipoprotein |

| mRSS | Modified Rodnan Skin Score |

| NASCET | North American Symptomatic Carotid Endarterectomy Trial |

| NT-proBNP | N-terminal pro Brain Natriuretic Peptide |

| NVC | Nailfold Videocapillaroscopy |

| PAH | Pulmonary Arterial Hypertension |

| PDE5i | Phosphodiesterase Type 5 Inhibitors |

| PSV | Peak Systolic Velocity |

| RI | Resistive Index |

| RP | Raynaud’s Phenomenon |

| SBP | Systolic Blood Pressure |

| Scl-70 | Anti-Topoisomerase I Antibodies |

| SSc | Systemic Sclerosis |

| TG | Triglycerides |

| Tyg | Triglyceride-Glucose Index |

| VEDOSS | Very Early Diagnosis of Systemic Sclerosis |

References

- Mok, M.Y.; Lau, C.S. The burden and measurement of cardiovascular disease in SSc. Nat. Rev. Rheumatol. 2010, 6, 430–434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Keret, S.; Rimar, D.; Lansiaux, P.; Feldman, E.; Lescoat, A.; Milman, N.; Farge, D.; MATHEC working group. Differentially expressed genes in systemic sclerosis: Towards predictive medicine with new molecular tools for clinicians. Autoimmun. Rev. 2023, 22, 103314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bandini, G.; Randone, S.B.; Manetti, M.; Dagna, L.; Cerinic, M.M.; Pignone, A.M. Endotheliopathy in systemic sclerosis: from endothelium-dependent vasodilation to the dysfunction of the vascular reserve, is the paradise lost? Arthritis Res. Ther. 2025, 27, 107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lescoat, A. Very Early Diagnosis of Systemic Sclerosis: Deciphering the heterogeneity of systemic sclerosis in the very early stages of the disease. J. Scleroderma Relat. Disord. 2023, 8, 3–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, D.; Li, M.-T.; Hou, Y.; Wang, Q.; Hu, C.-J.; Song, N.; Zhao, J.-L.; Zeng, X.-F.; Zhang, F.-C. Clinical characteristics of systemic sclerosis patients with digital ulcers in China. Clin Exp Rheumatol. 2013, 31, 46–9. [Google Scholar]

- Mouthon, L.; Mestre-Stanislas, C.; Bérezné, A.; Rannou, F.; Guilpain, P.; Revel, M.; Pagnoux, C.; Guillevin, L.; Fermanian, J.; Poiraudeau, S. Impact of digital ulcers on disability and health-related quality of life in systemic sclerosis. Ann. Rheum. Dis. 2010, 69, 214–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mihai, C.; Distler, O.; Gheorghiu, A.M.; I Constantin, P.; Dobrota, R.; Jordan, S.; Smith, V.; Hachulla, E.; Henes, J.; Siegert, E.; et al. Incidence and risk factors for gangrene in patients with systemic sclerosis from the EUSTAR cohort. Rheumatology 2019, 59, 2016–2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patnaik, E.; Lyons, M.; Tran, K.; Pattanaik, D. Endothelial Dysfunction in Systemic Sclerosis. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 14385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McMahan ZH, Wigley FM. Raynaud's phenomenon and digital ischemia: a practical approach to risk stratification, diagnosis and management. Int J Clin Rheumtol. 2010, 5, 355–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edjlali-Goujon, M.; Alison, D.; Technologique, C.H.R.E.U.T.C.D. Acute Digital Ischaemia – What the Radiologist Needs to Know. Eur. Cardiol. Rev. 2011, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pahwa R, Jialal I. Atherosclerosis. StatPearls Publishing. 2025.

- Rollando, D.; Bezante, G.P.; Sulli, A.; Balbi, M.; Panico, N.; Pizzorni, C.; Negrini, S.; Brunelli, C.; Barsotti, A.; Cutolo, M.; et al. Brachial Artery Endothelial-dependent Flow-mediated Dilation Identifies Early-stage Endothelial Dysfunction in Systemic Sclerosis and Correlates with Nailfold Microvascular Impairment. J. Rheumatol. 2010, 37, 1168–1173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liakouli, V.; Verde, I.; Ruscitti, P.; Di Vico, C.; Ruggiero, A.; Mauro, D.; Forte, G.; Navarini, L.; Di Donato, S.; Bearzi, P.; et al. Clinical and subclinical atherosclerosis in patients with systemic sclerosis: an observational, multicentre study of GIRRCS (Gruppo Italiano di Ricerca in Reumatologia Clinica e Sperimentale). Clin. Exp. Rheumatol. 2024, 42, 1645–1655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bedi, R.; Nagra, A.; Fukumoto, T.; Lynum, S.; Sengupta, P.; Aw, J.; Mefford, I.; Panwar, S.R.; Bansal, N.; Insaan, P.; et al. Detection of Subclinical Atherosclerosis in Peripheral Arterial Beds With B-Mode Ultrasound: A Proposal for Guiding the Decision for Medical Intervention and an Artifact-Corrected Volumetric Scoring Index. Glob. Hear. 2014, 9, 367–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen LY, Leening MJ, Norby FL, Roetker NS, Hofman A, Franco OH, Pan W, Polak JF, Witteman JC, Kronmal RA, Folsom AR, Nazarian S, Stricker BH, Heckbert SR, Alonso A. Carotid Intima-Media Thickness and Arterial Stiffness and the Risk of Atrial Fibrillation: The Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities (ARIC) Study, Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis (MESA), and the Rotterdam Study. J Am Heart Assoc. 2016 ;5(5):e002907.

- Bill, O.; Mazya, M.V.; Michel, P.; Moreira, T.P.; Lambrou, D.; Meyer, I.A.; Hirt, L. Intima-Media Thickness and Pulsatility Index of Common Carotid Arteries in Acute Ischaemic Stroke Patients with Diabetes Mellitus. J. Clin. Med. 2022, 12, 246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morales, M.M.; Anacleto, A.; Filho, C.M.; Ledesma, S.; Aldrovani, M.; Wolosker, N. Peak Systolic Velocity for Calcified Plaques Fails to Estimate Carotid Stenosis Degree. Ann. Vasc. Surg. 2019, 59, 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alexandrov, A.V.; Tsivgoulis, G.; Rubiera, M.; Vadikolias, K.; Stamboulis, E.; Molina, C.A. End-Diastolic Velocity Increase Predicts Recanalization and Neurological Improvement in Patients With Ischemic Stroke With Proximal Arterial Occlusions Receiving Reperfusion Therapies. Stroke 2010, 41, 948–952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delong C, Sharma S. Physiology, Peripheral Vascular Resistance. StatPearls Publishing; 2025 Jan.

- van den Hoogen F, Khanna D, Fransen J, Johnson SR, Baron M, Tyndall A, Matucci-Cerinic M, Naden RP, Medsger TA Jr, Carreira PE, Riemekasten G, Clements PJ, Denton CP, Distler O, Allanore Y, Furst DE, Gabrielli A, Mayes MD, van Laar JM, Seibold JR, Czirjak L, Steen VD, Inanc M, Kowal-Bielecka O, Müller-Ladner U, Valentini G, Veale DJ, Vonk MC, Walker UA, Chung L, Collier DH, Ellen Csuka M, Fessler BJ, Guiducci S, Herrick A, Hsu VM, Jimenez S, Kahaleh B, Merkel PA, Sierakowski S, Silver RM, Simms RW, Varga J, Pope JE. 2013 classification criteria for systemic sclerosis: an American college of rheumatology/European league against rheumatism collaborative initiative. Ann Rheum Dis. 2013 Nov;72(11):1747-55.

- Khanna, D.; Furst, D.E.; Clements, P.J.; Allanore, Y.; Baron, M.; Czirjak, L.; Distler, O.; Foeldvari, I.; Kuwana, M.; Matucci-Cerinic, M.; et al. Standardization of the Modified Rodnan Skin Score for Use in Clinical Trials of Systemic Sclerosis. J. Scleroderma Relat. Disord. 2017, 2, 11–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cutolo, M.; Cerinic, M.M. Nailfold capillaroscopy and classification criteria for systemic sclerosis. Clin Exp Rheumatol. 2007 Sep-Oct;25(5):663-5.

- Rehman S, Hashmi MF. Blood Pressure Measurement. StatPearls Publishing; 2025 Jan.

- Hemann, B.A.; Bimson, W.F.; Taylor, A.J. The Framingham Risk Score: An Appraisal of Its Benefits and Limitations. Am. Hear. Hosp. J. 2007, 5, 91–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duttagupta, S.; Thachathodiyl, R.; Rameshan, A.; Venkatachalam, A.; Georgy, S.; Ts, D.; Menon, J. Effectiveness of Framingham and ASCVD Risk Scores in Predicting Coronary Artery Disease - A Comparative Study with Syntax Score. . 2022, 69, 11–12. [Google Scholar]

- Heidenreich, P.A.; Bozkurt, B.; Aguilar, D.; Allen, L.A.; Byun, J.J.; Colvin, M.M.; Deswal, A.; Drazner, M.H.; Dunlay, S.M.; Evers, L.R.; et al. 2022 AHA/ACC/HFSA Guideline for the Management of Heart Failure: A Report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Joint Committee on Clinical Practice Guidelines. Circulation 2023, 147, e674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y.; Ji, H.; Sun, W.; An, X.; Lian, F. Triglyceride glucose (TyG) index: A promising biomarker for diagnosis and treatment of different diseases. Eur. J. Intern. Med. 2024, 131, 3–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Millán J, Pintó X, Muñoz A, Zúñiga M, Rubiés-Prat J, Pallardo LF, Masana L, Mangas A, Hernández-Mijares A, González-Santos P, Ascaso JF, Pedro-Botet J. Lipoprotein ratios: Physiological significance and clinical usefulness in cardiovascular prevention. Vasc Health Risk Manag. 2009;5:757-65. Epub 2009 Sep 18. PMID: 19774217; PMCID: PMC2747394. [PubMed]

- Babic, N.; Valjevac, A.; Zaciragic, A.; Avdagic, N.; Zukic, S.; Hasic, S. The Triglyceride/HDL Ratio and Triglyceride Glucose Index as Predictors of Glycemic Control in Patients with Diabetes Mellitus Type 2. Med Arch. 2019, 73, 163–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Onat A, Can G, Kaya H, Hergenç G. "Atherogenic index of plasma" (log10 triglyceride/high-density lipoprotein-cholesterol) predicts high blood pressure, diabetes, and vascular events. J Clin Lipidol. 2010 Mar-Apr;4(2):89-98.

- Majid, H.; Masood, Q.; Khan, A.H. Homeostatic Model Assessment for Insulin Resistance (HOMA-IR): A Better Marker for Evaluating Insulin Resistance Than Fasting Insulin in Women with Polycystic Ovarian Syndrome. . 2017, 27, 123–126. [Google Scholar]

- Seekircher, L.; Tschiderer, L.; Lind, L.; Safarova, M.S.; Kavousi, M.; Ikram, M.A.; Lonn, E.; Yusuf, S.; E Grobbee, D.; Kastelein, J.J.P.; et al. Intima-media thickness at the near or far wall of the common carotid artery in cardiovascular risk assessment. Eur. Hear. J. Open 2023, 3, oead089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Touboul, P.-J.; Hennerici, M.G.; Meairs, S.; Adams, H.; Amarenco, P.; Bornstein, N.; Csiba, L.; Desvarieux, M.; Ebrahim, S.; Hernandez, R.H.; et al. Mannheim Carotid Intima-Media Thickness and Plaque Consensus (2004–2006–2011). Cerebrovasc. Dis. 2012, 34, 290–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valaikiene, J.; Schuierer, G.; Ziemus, B.; Dietrich, J.; Bogdahn, U.; Schlachetzki, F. Transcranial Color-Coded Duplex Sonography for Detection of Distal Internal Carotid Artery Stenosis. Am. J. Neuroradiol. 2008, 29, 347–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- North American Symptomatic Carotid Endarterectomy Trial Collaborators; Barnett HJM, Taylor DW, Haynes RB, Sackett DL, Peerless SJ, Ferguson GG, Fox AJ, Rankin RN, Hachinski VC, Wiebers DO, Eliasziw M. Beneficial effect of carotid endarterectomy in symptomatic patients with high-grade carotid stenosis. N Engl J Med. 1991 Aug 15;325(7):445-53.

- Grant, E.G.; Benson, C.B.; Moneta, G.L.; Alexandrov, A.V.; Baker, J.D.; Bluth, E.I.; Carroll, B.A.; Eliasziw, M.; Gocke, J.; Hertzberg, B.S.; et al. Carotid Artery Stenosis: Gray-Scale and Doppler US Diagnosis—Society of Radiologists in Ultrasound Consensus Conference. Radiology 2003, 229, 340–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jones, X.M.; Bottini, N.; Boin, F.; Marbán, E. Cardiac involvement in systemic sclerosis: A critical review of knowledge gaps and opportunities. J. Scleroderma Relat. Disord. 2025, 10, 91–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Capparelli, E.; Zaccara, E.; Suardi, I.; Laria, A.; Castelnovo, L.; Mauric, E.; Bompane, D.; Tamburello, A.; Iacovantuono, M.; Chimenti, M.S.; et al. Uncovering Subclinical Cardiac Involvement in VEDOSS: An Echocardiographic Driven Study. Sclerosis 2025, 3, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sherif, A.A.; Gilvaz, V.J.; Abraham, S.; Saji, A.M.; Mathew, D.; Isath, A.; Rajendran, A.; Contreras, J.; Lanier, G.M.; Reginato, A.M. Systemic sclerosis is associated with increased in-patient mortality in patients hospitalized for heart failure. ESC Hear. Fail. 2024, 11, 1900–1910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tyndall, A.J.; Bannert, B.; Vonk, M.; Airò, P.; Cozzi, F.; Carreira, P.E.; Bancel, D.F.; Allanore, Y.; Müller-Ladner, U.; Distler, O.; et al. Causes and risk factors for death in systemic sclerosis: a study from the EULAR Scleroderma Trials and Research (EUSTAR) database. Ann. Rheum. Dis. 2010, 69, 1809–1815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Györfi, A.; Filla, T.; Polzin, A.; Tascilar, K.; Buch, M.; Tröbs, M.; Matei, A.; Airo, P.; Balbir-Gurman, A.; Kuwert, F.; et al. Evaluation of Systemic Sclerosis Primary Heart Involvement and Chronic Heart Failure in the European Scleroderma Trials and Research Cohort. J. Am. Hear. Assoc. 2025, 14, e036730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Caimmi, C.; De Marchi, S.; Bosello, S.L.; Giuggioli, D.; Caramaschi, P.; Di Giorgio, A.; Spinella, A.; Astorino, G.; Canestrari, G.; Cocchiara, E.; et al. Ultrasonography involvement of carotid, upper and lower limb arteries in a large cohort of systemic sclerosis patients. Int. J. Rheum. Dis. 2020, 23, 681–692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Motegi, S.; Toki, S.; Hattori, T.; Yamada, K.; Uchiyama, A.; Ishikawa, O. No association of atherosclerosis with digital ulcers in Japanese patients with systemic sclerosis: Evaluation of carotid intima-media thickness and plaque characteristics. J. Dermatol. 2014, 41, 604–608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sayan M, Raaj KB, Hooijenga P, Cassidy S, Nova A, De Ciutiis I, Wang T, Kroeger CM, Stamatakis E, Masedunskas A, De Caterina R, Cagigas ML, Fontana L, Carotid intima-media thickness, cardiovascular disease, and risk factors in 29,000 UK Biobank adults, American Journal of Preventive Cardiology. 2025. Volume 22.

- Bartoli, F.; Blagojevic, J.; Bacci, M.; Fiori, G.; Tempestini, A.; Conforti, M.L.; Guiducci, S.; Miniati, I.; DI Chicco, M.; DEL Rosso, A.; et al. Flow-Mediated Vasodilation and Carotid Intima-Media Thickness in Systemic Sclerosis. Ann. New York Acad. Sci. 2007, 1108, 283–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sedky Abdou MM, El Desouky SM, Helmy El Kaffas KM, Ahmed Hassan AM. Premature atherosclerosis in systemic sclerosis patients: Its relation to disease parameters and to traditional risk factors. Int J Rheum Dis. 2017 Mar;20(3):383-389.

- Soltész, P.; Kerekes, G.; Dér, H.; Szücs, G.; Szántó, S.; Kiss, E.; Bodolay, E.; Zeher, M.; Timár, O.; Szodoray, P.; et al. Comparative assessment of vascular function in autoimmune rheumatic diseases: Considerations of prevention and treatment. Autoimmun. Rev. 2011, 10, 416–425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frerix, M.; Stegbauer, J.; Kreuter, A.; Weiner, S.M. Atherosclerotic plaques occur in absence of intima-media thickening in both systemic sclerosis and systemic lupus erythematosus: a duplexsonography study of carotid and femoral arteries and follow-up for cardiovascular events. Arthritis Res. Ther. 2014, 16, R54–R54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schiopu, E.; Au, K.M.; McMahon, M.A.; Kaplan, M.J.; Divekar, A.; Singh, R.R.; Furst, D.E.; Clements, P.J.; Ragvendra, N.; Zhao, W.; et al. Prevalence of subclinical atherosclerosis is increased in systemic sclerosis and is associated with serum proteins: a cross-sectional, controlled study of carotid ultrasound. Rheumatology 2014, 53, 704–713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strosberg DS, Haurani MJ, Satiani B, Go MR. Common carotid artery end-diastolic velocity and acceleration time can predict degree of internal carotid artery stenosis. J Vasc Surg. 2017 Jul;66(1):226-231.

- Cannarile F, Valentini V, Mirabelli G, Alunno A, Terenzi R, Luccioli F, Gerli R, Bartoloni E. Cardiovascular disease in systemic sclerosis. Ann Transl Med. 2015 Jan;3(1):8.

- Oreska, S.; Tomcik, M. Atherosclerosis and Cardiovascular Risk in Systemic Sclerosis. Systemic Sclerosis. InTech; 2017.

- Sanz Pérez I, Martínez Valle F, Guillén-Del-Castillo A, Roque Pérez A, Cuéllar Calàbria H, Pizzi MN, Fernández Codina A, Callejas-Moraga E, Orozco Gálvez O, Fonollosa Pla V, Simeón Aznar CP. Subclinical cardiovascular disease and Systemic Sclerosis: A comparison between risk charts, quantification of coronary calcium and carotid ultrasonography. Autoimmun Rev. 2018 Sep;17(9):900-905.

| Non-DUs n=76 |

DUs n=31 |

p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Female, n/% | 73 / 96.1 | 22 / 71 | <0.001 |

| Age at enrollment, mean±SD | 61.85±12.4 | 58.8±12.7 | 0.254 |

| Age at diagnosis, mean±SD | 49.9±13.2 | 43.4±15.2 | 0.041 |

| Disease Duration, mean±SD | 68.4±335.6 | 15.0±9 | 0.396 |

| Body Mass Index, (Kg/m2), mean±SD | 23.1±4.7 | 23.4±4.2 | 0.813 |

| Body Surface Area, (m2), mean±SD | 1.64±0.18 | 1.69±0.21 | 0.204 |

| Anti-centromere, n/% | 42 / 55.3 | 12 / 38.7 | 0.138 |

| Anti-Scl70, n/% | 6 / 7.9 | 11 / 35.5 | 0.001 |

| Anti-RNA polimerase III, n/% | 1 / 1.3 | 2 / 6.5 | 0.144 |

| Current Smokers, n/% | 17 / 22.4 | 8 / 25.8 | 0.703 |

| mRSS at last follow up, mean±SD | 2.1±2.3 | 8.5±8.4 | <0.001 |

| LEROY CLASSIFICATION, n/% | |||

| Sine scleroderma | 26 / 34.2 | 2 / 6.5 | 0.001 |

| Limitate | 49 / 64.5 | 17 / 54.8 | 0.001 |

| Diffuse | 1 / 1.3 | 12 / 38.7 | 0.001 |

| NVC pattern, n/% | |||

| Early/active | 58 / 76.3 | 14 / 45.2 | 0.002 |

| Late | 18 / 23.7 | 17 / 54.8 | 0.002 |

| Clinical Manifestations, n/% | |||

| Puffy hands | 60 / 78.9 | 16 / 51.6 | 0.005 |

| Current Digital Ulcers | 0 | 6 / 20 | <0.001 |

| Teleangctasias | 30 / 39.5 | 23 / 74.2 | 0.001 |

| Pitting scars | 16 / 21.1 | 25 / 80.6 | <0.001 |

| Sclerodactily | 33 / 43.4 | 26 / 83.9 | 0.001 |

| Clacinosis | 10 / 13.2 | 12 / 38.7 | 0.003 |

| Friction Rubs | 0 | 4 / 12.9 | 0.001 |

| Arthritis | 24 / 31.6 | 12 / 38.7 | 0.479 |

| Upper GI Involvement | 43 / 56.6 | 25 / 80.6 | 0.019 |

| Lower GI Involvement | 17 / 22.7 | 8 / 25.8 | 0.729 |

| Microstomia | 15 / 19.7 | 17 / 54.8 | <0.001 |

| Scleroderma Renal Crisis | 1 / 1.3 | 1 / 3.2 | 0.508 |

| Cardiomyopathy | 0 | 1 / 3.2 | 0.116 |

| Pulmonary Arterial Hypertension | 1 / 1.3 | 1 / 3.2 | 0.508 |

| Interstitial Lung Disease | 9 / 11.8 | 15 / 48.4 | <0.001 |

| Non-DUs n=76 |

DUs n=31 |

p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cardiovascular symptoms and related comorbidities | |||

| Angina pectoris, n/% | 4 / 5.3 | 6 / 19.4 | 0.023 |

| Dyspnoea, n/% | 10 / 13.6 | 6 / 19.4 | 0.415 |

| Cardiopalmus, n/% | 7 / 9.2 | 4 / 12.9 | 0.568 |

| Arrhytmias, n/% | 19 / 25 | 13 / 41.9 | 0.083 |

| Systemic Arterial Hypertension, n/% | 22 / 28.9 | 13 / 41.9 | 0.194 |

| Dyslipidemia, n/% | 15 / 19.7 | 9 / 29 | 0.296 |

| Type 2 Diabetes, n/% | 2 / 2.6 | 2 / 6.5 | 0.345 |

| Hyperuricemia, n/% | 1 / 1.3 | 5 / 16.1 | 0.003 |

| Metabolic Assessment, mean±SD | |||

| Total Cholesterol (mg/dl) | 188.3±41.6 | 187.4±39.1 | 0.922 |

| HDL-Cholesterol (mg/dl) | 63.9±16.5 | 60.5±16.2 | 0.342 |

| LDL-Cholesterol (mg/dl) | 115.8±31.5 | 113.3±33.8 | 0.735 |

| Tryglicerides (mg/dl) | 96.9±43.6 | 100.3±48.1 | 0.748 |

| Fasting Glucose (mg/dl) | 91.6±15.8 | 92.9±29.1 | 0.773 |

| Insulin | 17.7±26.8 | 10.9±8.8 | 0.344 |

| TyG index | 8.3±0.5 | 8.1±1.4 | 0.361 |

| c-LDL/c-HDL ratio | 2.04±1.81 | 1.94±0.69 | 0.786 |

| TG/c-HDL ratio | 1.78±1.54 | 1.73±1.09 | 0.891 |

| Atherogenic Index of Plasma | 0.16±0.27 | 0.14±0.37 | 0.712 |

| HOMA-IR Index | 3.8±8.1 | 0.8±0.7 | 0.171 |

| hs-TnT (ng/ml) | 7.9±5.9 | 10.1±11.2 | 0.325 |

| C-Reactive Protein (mg/L) | 1.8±2.2 | 2.7±2.5 | 0.068 |

| NT-proBNP, (pg/ml) | 109.3±106.6 | 139.9±122.5 | 0.202 |

| Uric Acid, (mg/dl) | 4.4±1.1 | 4.5±1.3 | 0.678 |

| 1st SBP (mmHg) | 118.02±16.4 | 121.8±14.1 | 0.334 |

| 1st DBP (mmHg) | 78.8±9.4 | 74.5±13.0 | 0.094 |

| 1st HR (bpm) | 78.9±11.9 | 75.2±10.6 | 0.203 |

| 2nd SBP (mmHg) | 122.3±17.1 | 123.1±20.4 | 0.851 |

| 2nd DBP (mmHg) | 79.8±11.3 | 76.2±9.1 | 0.194 |

| 2nd HR (bpm) | 77.6±9.8 | 75.8±15.7 | 0.541 |

| Familial CV events, n/% | 19 / 25.3 | 9 /29 | 0.694 |

| Personal CV events, n/% | 3 /4.0 | 2 / 6.5 | 0.588 |

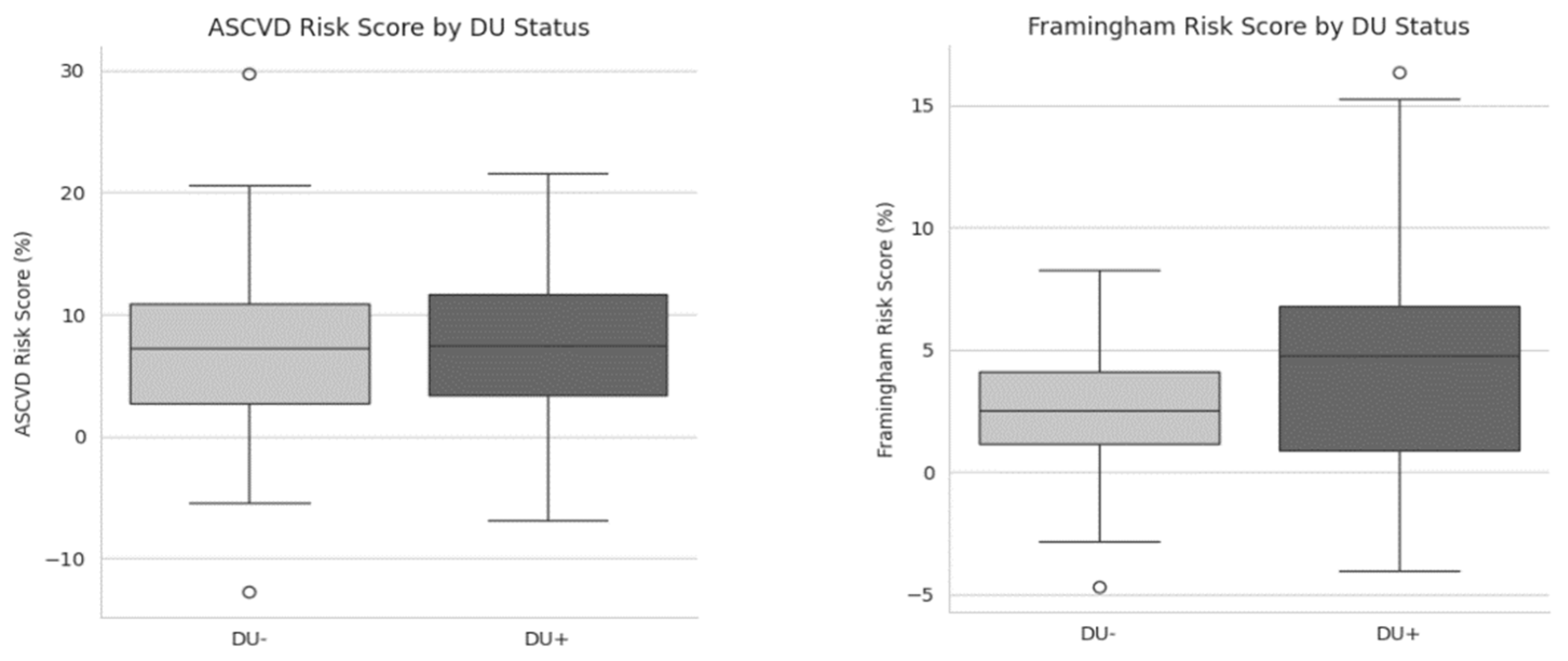

| Framingham risk score, mean±SD | 2.9±2.9 | 4.4±4.4 | 0.048 |

| ASCVD risk score, mean±SD | 6.7±6.0 | 7.1±6.6 | 0.787 |

| Right scanning | Left Scanning | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Carotid-Vertebral US measurements | Non-DUs | DUs | p-value | Non-DUs | DUs | p-value |

| cIMT, mean±SD | 1.17±3.03 | 0.82±0.19 | 0.991 | 0.79±0.19 | 0.85±0.14 | 0.170 |

| Common Carotid Arteries, mean±SD | ||||||

| Peak Systolic Velocity | 56.7±18.8 | 62.5±16.9 | 0.172 | 58.7±20.3 | 64.6±21.0 | 0.205 |

| End Diastolic Velocity | 15.9±6.2 | 16.1±7.1 | 0.973 | 17.1±7.79 | 18.4±7.9 | 0.482 |

| Resistive Index | 0.72±0.06 | 0.74±0.08 | 0.070 | 0.71±0.08 | 0.72±0.06 | 0.887 |

| Internal Carotid Artery, mean±SD | ||||||

| Peak Systolic Velocity | 64.2±20.5 | 86.9±67.9 | 0.010 | 63.4±18.2 | 78.9±29.6 | 0.002 |

| End Diastolic Velocity | 21.2±8.0 | 22.4±10.4 | 0.544 | 23.2±8.5 | 28.2±23.7 | 0.129 |

| Resistive Index | 0.67±0.07 | 0.71±0.09 | 0.021 | 0.63±0.07 | 0.61±0.49 | 0.676 |

| External Carotid Artery, mean±SD | ||||||

| Peak Systolic Velocity | 75.0±24.2 | 87.7±25.3 | 0.002 | 71.7±20.1 | 86.1±24.1 | 0.003 |

| End Diastolic Velocity | 16.5±7.6 | 19.8±12.8 | 0.113 | 14.9±6.2 | 18.6±8.3 | 0.143 |

| Resistive Index | 0.77±0.08 | 0.68±0.65 | 0.654 | 0.79±0.06 | 0.79±0.07 | 0.808 |

| Vertebral Artery, mean±SD | ||||||

| Peak Systolic Velocity | 38.1±11.9 | 42.6±12.1 | 0.218 | 39.5±14.1 | 43.9±13.9 | 0.277 |

| End Diastolic Velocity | 11.6±4.9 | 12.9±5.5 | 0.230 | 13.2±8.4 | 13.6±6.4 | 0.394 |

| Resistive Index | 0.65±0.36 | 0.71±0.08 | 0.627 | 0.64±0.37 | 0.70±0.09 | 0.339 |

| Carotid Stenosis percentage, mean±SD | 25.7±14.3 | 35.6±14.9 | 0.133 | 25.0±011.1 | 27.8±15.7 | 0.547 |

| PSV ICA/CCA, mean±SD | 1.16±0.33 | 1.48±1.21 | 0.043 | 1.13±0.31 | 1.25±0.47 | 0.171 |

| Mean PSV at ICA (dependent variable) | Mean PSV at ECA (dependent variable) | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| β-Coeff. | β-stand. (95% CI) | p | β-Coeff. | β -stand. (95% CI) | p | ||||

| Constant | 120.83 | -15.75 to 257.42 | 0.082 | 142.58 | 33.16 to 252.01) | 0.012 | |||

| Age | -1.30 | -0.43 (-2.75 to 0.14) | 0.077 | -1.370 | -0.61 (-2.52 to -0.21) | 0.022 | |||

| Sex (Female) | 16.11 | 0.16 (-19.51 to 51.73) | 0.367 | 0.18 | 0.003 (-28.35 to 28.72) | 0.990 | |||

| BMI (Kg/m2) | -0.62 | -0.08 (-2.76 to 1.51) | 0.562 | -0.21 | -0,041 (-1.93 to 1.49) | 0.799 | |||

| SBP (mmHg) | 0.14 | 0.06 (-0.49 to 0.77) | 0.659 | 0.02 | 0.01 (-0.48 to 0.53) | 0.931 | |||

| CRP (mg/L) | -1.19 | -0.05 (-8.43 to 6.03) | 0.740 | 3.55 | 0.22 (-2.24 to 9.35) | 0.223 | |||

| AIP ratio | 11.32 | 0.08 (-31.48 to 54.14) | 0.597 | 5.22 | 0.05 (-29.07 to 39.52) | 0.760 | |||

| LDL/HDL ratio | 1.56 | 0.04 (-11.32 to 14.45) | 0.808 | 0.42 | 0.01 (-9.90 to 10.75) | 0.935 | |||

| Digital Ulcers | 33.71 | 0.48 (13.62 to 53.81) | 0.002 | 7.75 | 0.15 (-8.34 to 23.85) | 0.337 | |||

| Framingham Risk Score | -3.36 | -0.31 (-8.63 to 1.90) | 0.205 | -1.73 | -0.22 (-5.95 to 2.48) | 0.411 | |||

| ASCVD Risk Score | 1.63 | 0.31 (-1.25 to 4.53) | 0.261 | 2.22 | 0.58 (-0.09 to 4.54) | 0.060 | |||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).