Submitted:

03 July 2025

Posted:

04 July 2025

You are already at the latest version

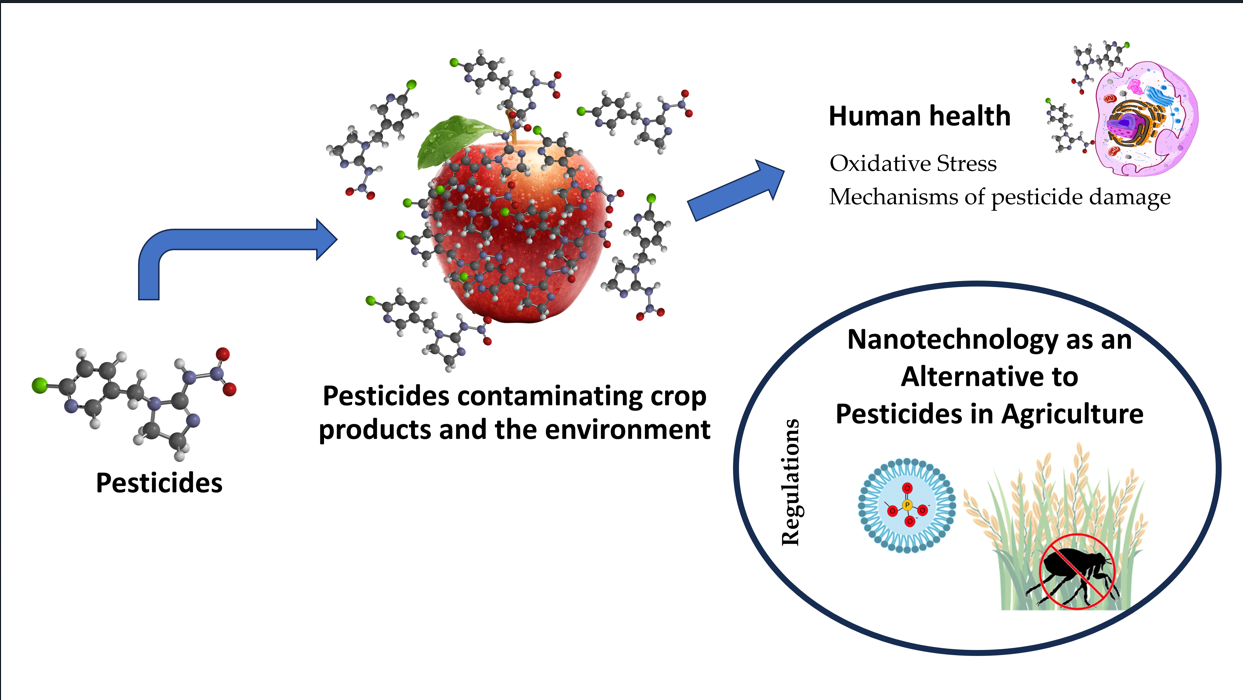

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

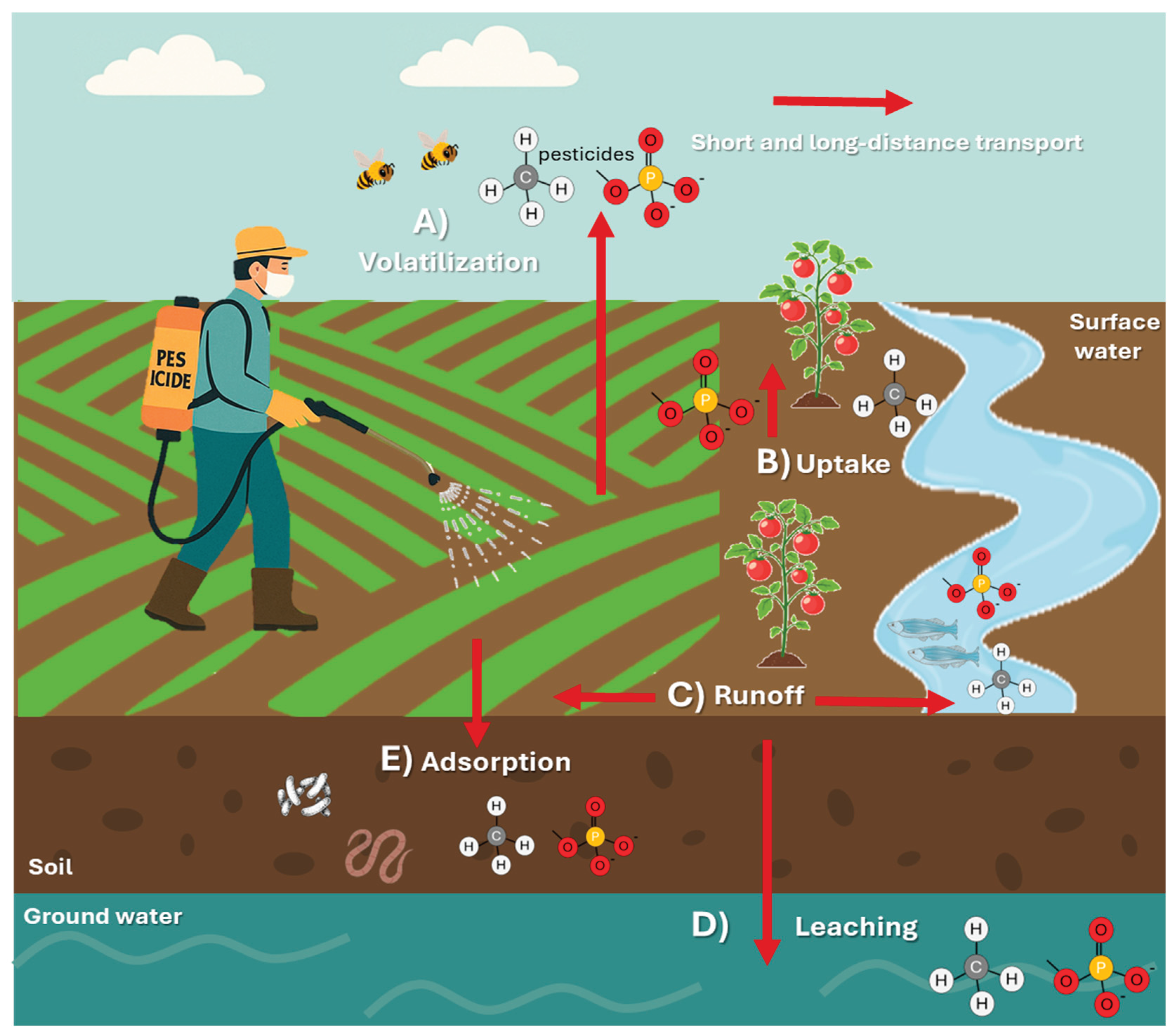

2. Environmental Impact of Conventional Pesticides

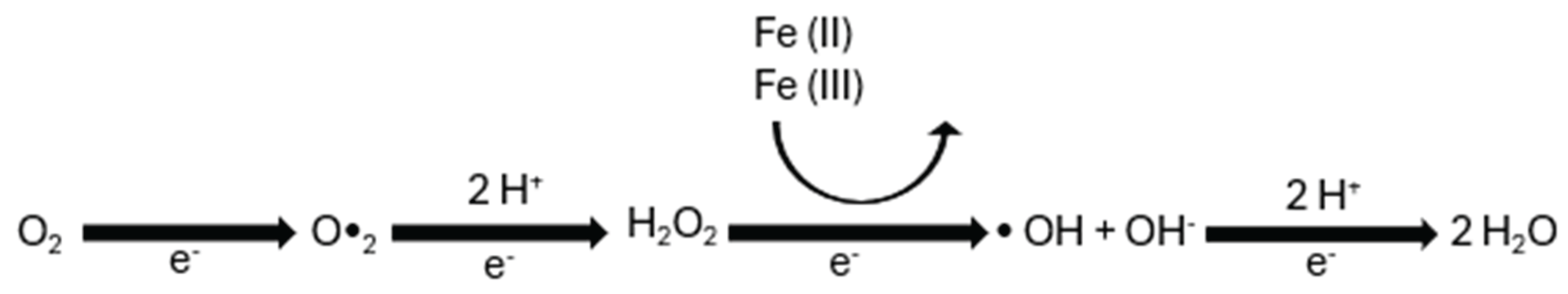

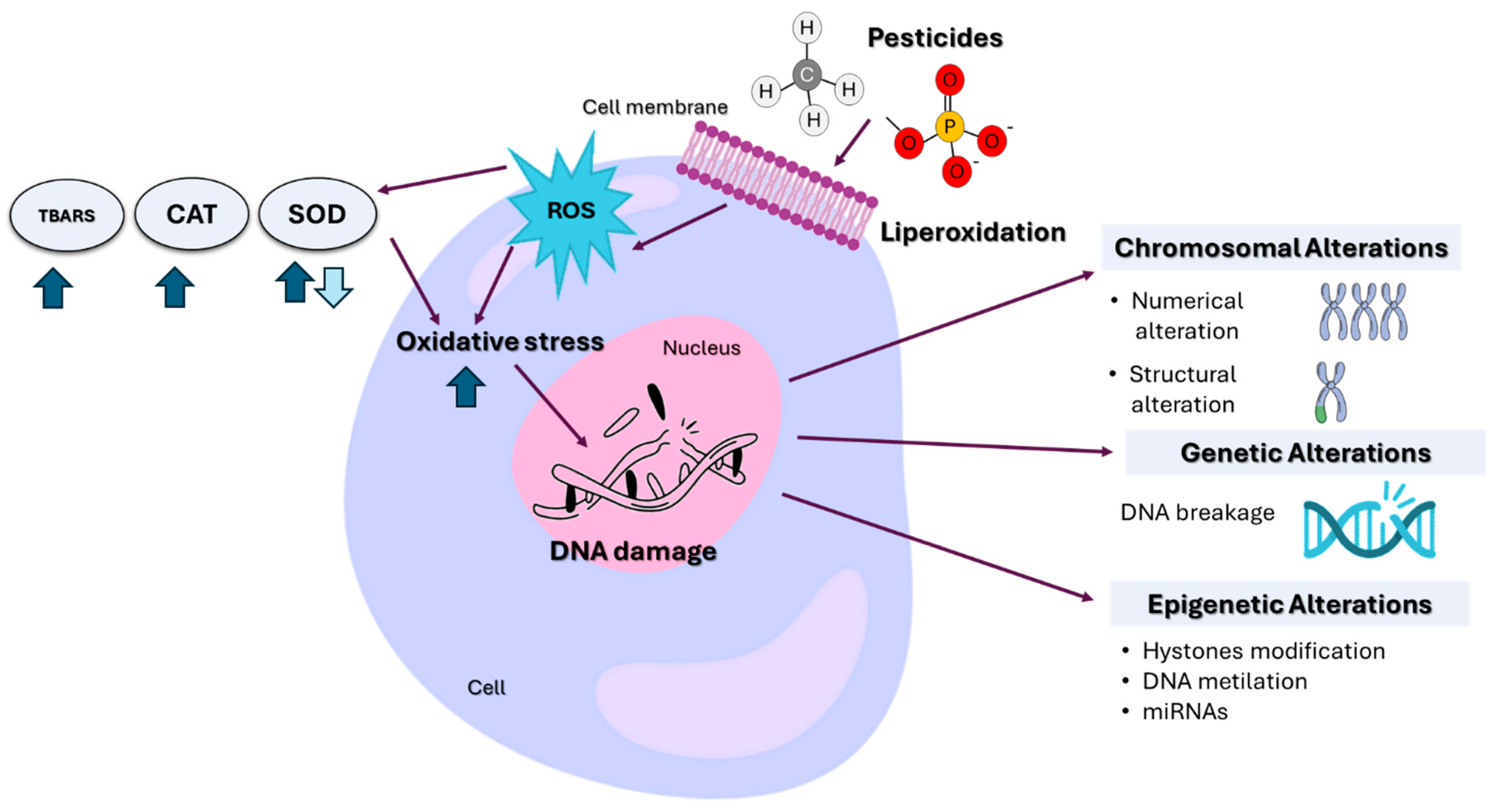

3. Oxidative Stress Risk Associated with Pesticide Exposure

4. Pesticides in Food and Their Effect on Human Health

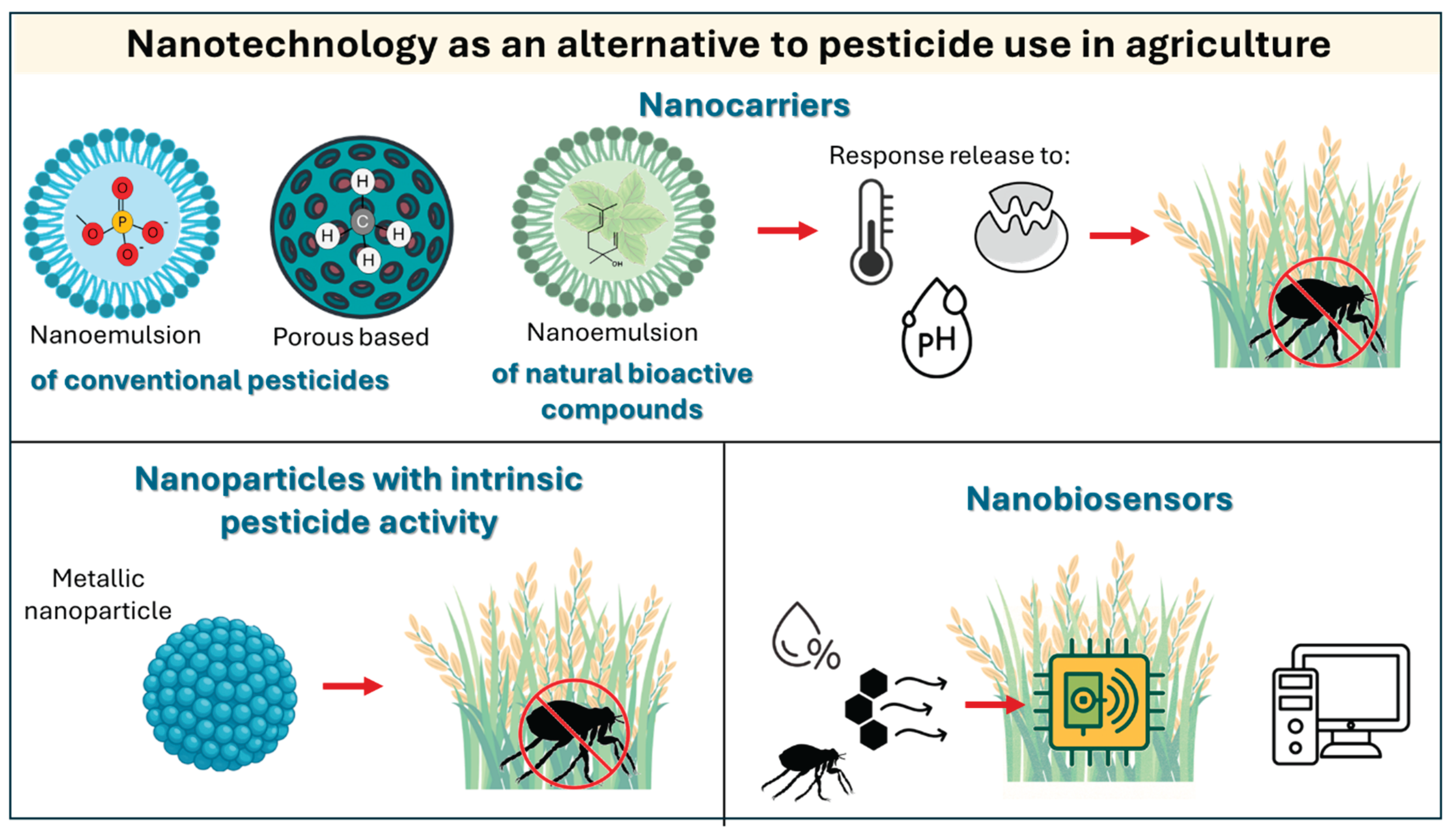

5. Nanotechnology as an Alternative to Pesticides in Agriculture

6. Regulations

7. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| 2,4-D | 2,4-Dichlorophenoxyacetic acid |

| 2,4-DDE | 2,4-Dichlorodiphenyldichloroethylene |

| 4,4-DDE | 4,4-Dichlorodiphenyldichloroethylene |

| b-BHC | Beta-hexachlorocyclohexane |

| CAT | catalase |

| DDT | dichlorodiphenyltrichloroethane |

| DDT | Dichlorodiphenyltrichloroethane |

| DEE | Diethyl ether |

| e-nose | Electronic nose |

| EPA | Environmental Protection Agency |

| FAO | Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations |

| FDA | Food and Drug Administration |

| e-tongue | Electronic tongue |

| g-BHC | Gamma-hexachlorocyclohexane (Lindane); |

| GPx | glutathione peroxidase |

| GST | glutathione-S-transferase |

| HCB | Hexachlorobenzene |

| LD50 | Median lethal dose |

| MRLs | Maximum Residue Limits. |

| MRLs | Maximum Residue Limits |

| RNS | Reactive nitrogen species |

| ROS | Reactive oxygen species |

| SOD | Superoxide dismutase |

| TBARS | Thiobarbituric acid reactive substances |

| UPLC-MS/MS | Ultra Performance Liquid Chromatography coupled with Tandem Mass Spectrometry |

| USDA | U.S. Department of Agriculture |

References

- Chamizo, J.A. La no neutralidad de la química vista desde la historia. Educación Química.

- López-Maldonado, V. Uso de la nanotecnología en los diferentes sistemas productivos. Milenaria, Ciencia y arte.

- Thorat, T.; Patle, B.; Wakchaure, M.; Parihar, L. Advancements in techniques used for identification of pesticide residue on crops. Journal of Natural Pesticide Research 2023, 4, 100031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaibor Zumba, M.D.; Saavedra Álava, M.I.; Gaibor Carpio, J.L. Impacto de una intervención educativa sobre la lactancia materna en madres adolescentes. Actas Médicas (Ecuador).

- Mostafalou, S.; Abdollahi, M. Pesticides: an update of human exposure and toxicity. Archives of Toxicology 2017, 91, 549–599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, W.; Li, M.; Achal, V. A comprehensive review on environmental and human health impacts of chemical pesticide usage. Emerging Contaminants 2024, 100410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tudi, M.; Daniel Ruan, H.; Wang, L.; Lyu, J.; Sadler, R.; Connell, D.; Chu, C.; Phung, D.T. Agriculture development, pesticide application and its impact on the environment. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 2021, 18, 1112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Padhiary, M.; Kumar, R. , Assessing the environmental impacts of agriculture, industrial operations, and mining on agro-ecosystems. In Smart Internet of Things for Environment and Healthcare, Springer: 2024; pp 107-126.

- Leskovac, A.; Petrović, S. Pesticide use and degradation strategies: food safety, challenges and perspectives. Foods 2023, 12, 2709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aswani, R.; Radhakrishnan, E.; Visakh, P. Nanoformulations for Agricultural Applications: State-of-the-Art, New Challenges, and Opportunities. Nanoformulations for Agricultural Applications 2025, 1–34. [Google Scholar]

- Khan, J.; Kaur, A.; Alam, M.A.; Yadav, A.; Paramanick, D.; Chaudhary, S. , Nanopesticides, Nanoherbicides, and Nanofertilizers: Risks and environmental acceptability. In Nanopesticides, Nanoherbicides, and Nanofertilizers, CRC Press: 2023; pp 94-113.

- Pathak, V.M.; Verma, V.K.; Rawat, B.S.; Kaur, B.; Babu, N.; Sharma, A.; Dewali, S.; Yadav, M.; Kumari, R.; Singh, S. Current status of pesticide effects on environment, human health and it’s eco-friendly management as bioremediation: A comprehensive review. Front Microbiol 2022, 13, 962619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gabriel Ortega, J.; Ávila Demera, J.; Ayón Villao, F.; Morán Morán, J.; Álvarez Plúa, A.; Flores Ramírez, H. Utilización de plaguicidas por agricultores en Puerto La Boca, Manabí. Una reflexión sobre sus posibles consecuencias. Journal of the Selva Andina Biosphere.

- Rangel-Ortiz, E.; Landa-Cansigno, O.; Páramo-Vargas, J.; Camarena-Pozos, D.A. Prácticas de manejo de plaguicidas y percepciones de impactos a la salud y al medio ambiente entre usuarios de la cuenca del Río Turbio, Guanajuato, México. Acta Universitaria 2023, 33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajmohan, K.; Chandrasekaran, R.; Varjani, S. A review on occurrence of pesticides in environment and current technologies for their remediation and management. Indian Journal of Microbiology 2020, 60, 125–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Streletskii, R.; Astaykina, A.; Krasnov, G.; Gorbatov, V. Changes in bacterial and fungal community of soil under treatment of pesticides. Agronomy 2022, 12, 124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Souza, R.M.; Seibert, D.; Quesada, H.B.; de Jesus Bassetti, F.; Fagundes-Klen, M.R.; Bergamasco, R. Occurrence, impacts and general aspects of pesticides in surface water: A review. Process Safety and Environmental Protection 2020, 135, 22–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajan, D.K.; Mohan, K.; Rajarajeswaran, J.; Divya, D.; Thanigaivel, S.; Zhang, S. Toxic effects of organophosphate pesticide monocrotophos in aquatic organisms: a review of challenges, regulations and future perspectives. Environmental Research 2024, 244, 117947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Chen, Q.; Chen, B.; Dong, T.; Chen, M. Toxic effects of pesticides on the marine microalga Skeletonema costatum and their biological degradation. Science China Earth Sciences 2023, 66, 663–674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, V.; Sharma, N.; Sharma, P.; Pasrija, R.; Kaur, K.; Umesh, M.; Thazeem, B. Toxicity analysis of endocrine disrupting pesticides on non-target organisms: A critical analysis on toxicity mechanisms. Toxicology and Applied Pharmacology 2023, 474, 116623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elhamalawy, O.; Bakr, A.; Eissa, F. Impact of pesticides on non-target invertebrates in agricultural ecosystems. Pesticide Biochemistry and Physiology 2024, 105974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nicolopoulou-Stamati, P.; Maipas, S.; Kotampasi, C.; Stamatis, P.; Hens, L. Chemical pesticides and human health: the urgent need for a new concept in agriculture. Frontiers in Public Health 2016, 4, 148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miranda, R.A.; Silva, B.S.; de Moura, E.G.; Lisboa, P.C. Pesticides as endocrine disruptors: programming for obesity and diabetes. Endocrine 2023, 79, 437–447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gea, M.; Zhang, C.; Tota, R.; Gilardi, G.; Di Nardo, G.; Schilirò, T. Assessment of five pesticides as endocrine-disrupting chemicals: effects on estrogen receptors and aromatase. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 2022, 19, 1959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cavalier, H.; Trasande, L.; Porta, M. Exposures to pesticides and risk of cancer: Evaluation of recent epidemiological evidence in humans and paths forward. International Journal of Cancer 2023, 152, 879–912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Djekkoun, N.; Lalau, J.-D.; Bach, V.; Depeint, F.; Khorsi-Cauet, H. Chronic oral exposure to pesticides and their consequences on metabolic regulation: Role of the microbiota. European Journal of Nutrition 2021, 60, 4131–4149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silveira-Gramont, M.I.; Aldana-Madrid, M.L.; Piri-Santana, J.; Valenzuela-Quintanar, A.I.; Jasa-Silveira, G.; Rodríguez-Olibarria, G. Plaguicidas agrícolas: un marco de referencia para evaluar riesgos a la salud en comunidades rurales en el estado de Sonora, México. Revista Internacional de Contaminación Ambiental.

- Ajiboye, T.O.; Oladoye, P.O.; Olanrewaju, C.A.; Akinsola, G.O. Organophosphorus pesticides: Impacts, detection and removal strategies. Environmental Nanotechnology, Monitoring and Management, 1006. [Google Scholar]

- Jayaraj, R.; Megha, P.; Sreedev, P. Organochlorine pesticides, their toxic effects on living organisms and their fate in the environment. Interdisciplinary Toxicology 2016, 9, 90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kamalesh, T.; Kumar, P.S.; Rangasamy, G. An insights of organochlorine pesticides categories, properties, eco-toxicity and new developments in bioremediation process. Environmental Pollution 2023, 333, 122114. [Google Scholar]

- Mdeni, N.L.; Adeniji, A.O.; Okoh, A.I.; Okoh, O.O. Analytical evaluation of carbamate and organophosphate pesticides in human and environmental matrices: a review. Molecules 2022, 27, 618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rezende-Teixeira, P.; Dusi, R.G.; Jimenez, P.C.; Espindola, L.S.; Costa-Lotufo, L.V. What can we learn from commercial insecticides? Efficacy, toxicity, environmental impacts, and future developments. Environmental Pollution 2022, 300, 118983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farag, M.R.; Alagawany, M.; Bilal, R.M.; Gewida, A.G.; Dhama, K.; Abdel-Latif, H.M.; Amer, M.S.; Rivero-Perez, N.; Zaragoza-Bastida, A.; Binnaser, Y.S. An overview on the potential hazards of pyrethroid insecticides in fish, with special emphasis on cypermethrin toxicity. Animals 2021, 11, 1880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacob, M.S.; Iyyadurai, R.; Jose, A.; Fleming, J.J.; Rebekah, G.; Zachariah, A.; Hansdak, S.G.; Alex, R.; Chandiraseharan, V.K.; Lenin, A. Clinical presentation of type 1 and type 2 pyrethroid poisoning in humans. Clinical Toxicology 2022, 60, 464–471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, T.; Chen, H.; Wang, A.; Yao, W.; Xu, Z.; Wang, B.; Wang, J.; Wu, Y. Methyl Parathion Exposure Induces Development Toxicity and Cardiotoxicity in Zebrafish Embryos. Toxics 2023, 11, 84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Urióstegui-Acosta, M.; Tello-Mora, P.; de Jesús Solís-Heredia, M.; Ortega-Olvera, J.M.; Piña-Guzmán, B.; Martín-Tapia, D.; González-Mariscal, L.; Quintanilla-Vega, B. Methyl parathion causes genetic damage in sperm and disrupts the permeability of the blood-testis barrier by an oxidant mechanism in mice. Toxicology 2020, 438, 152463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zuo, W.; Zhang, X.; Chang, J.B.; Ma, W.B.; Wei, J.J. Bromadiolone poisoning leading to subarachnoid haemorrhage: A case report and review of the literature. Journal of Clinical Pharmacy and Therapeutics 2019, 44, 958–962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, A.; Yuan, F.; Yao, Y.; Wen, W.; Lu, H.; Wu, S.; Wang, L. Reversible leukoencephalopathy caused by 2 rodenticides bromadiolone and fluroacetamide: a case report and literature review. Medicine 2021, 100, e25053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.F.; Zhang, Z.J.; You, C.J.; Chen, L. A case of bromadiolone poisoning leading to digestive tract, abdominal hemorrhage and secondary paralytic ileus. Zhonghua lao Dong wei Sheng zhi ye Bing za zhi= Zhonghua Laodong Weisheng Zhiyebing Zazhi= Chinese Journal of Industrial Hygiene and Occupational Diseases.

- Wu, J.; Chen, J. One case of bromadiolone poisoning leading to intestinal necrosis and severe coagulopathy. Zhonghua lao Dong wei Sheng zhi ye Bing za zhi= Zhonghua Laodong Weisheng Zhiyebing Zazhi= Chinese Journal of Industrial Hygiene and Occupational Diseases.

- Hossain, M.; Suchi, T.T.; Samiha, F.; Islam, M.M.; Tully, F.A.; Hasan, J.; Rahman, M.A.; Shill, M.C.; Bepari, A.K.; Rahman, G.S. Coenzyme Q10 ameliorates carbofuran induced hepatotoxicity and nephrotoxicity in wister rats. Heliyon 2023, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, J.; Li, R.-X.; Yang, C.-S.; Zhao, L.-L.; Liu, X.; Zhang, B. Clinical study and observation on the effect of hemoperfusion therapy treatment on central nervous system injury in patients with 2, 4-dichlorophenoxyacetic acid poisoning. European Review for Medical and Pharmacological Sciences 2021, 25. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, Q.; Guo, Y.; Lian, L.; Li, J.; Blatchley 3rd, E. CH 3 NCl 2 Formation from Chlorination of Carbamate Insecticides. Environmental Science and Technology 2019, 53, 13098–13106. [Google Scholar]

- Freitas, L.M.; Valadares, L.P.d.A.; Camozzi, M.G.M.; de Oliveira, P.G.; Ferreira Machado, M.R.; Lima, F.C. Animal models in the neurotoxicology of 2,4-D. Human & Experimental Toxicology, 1182. [Google Scholar]

- Chauhan, R.; Rawat, A.; Sama, S.; Goel, D.; Ahmad, S. A case series of 2, 4 diethylamine poisoning–what the future holds for us. Tropical Doctor 2023, 53, 389–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seven, B. ; Kültiğin; Çavuşoğlu; Yalçin, E.; Acar, A. Investigation of cypermethrin toxicity in Swiss albino mice with physiological, genetic and biochemical approaches. Scientific Reports, 1143. [Google Scholar]

- Xie, Y.; Gong, L.; Liu, S.; Yan, J.; Zhao, S.; Xia, C.; Li, K.; Liu, G.; Mazhar, M.W.; Zhao, J. Antioxidants improve β-cypermethrin degradation by alleviating oxidative damage and increasing bioavailability by Bacillus cereus GW-01. Environmental Research 2023, 236, 116680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richardson, J.R.; Fitsanakis, V.; Westerink, R.H.; Kanthasamy, A.G. Neurotoxicity of pesticides. Acta Neuropathologica 2019, 138, 343–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ha, M.; Dong, Z.; Li, L.; Wang, L.; Liu, C. Cypermethrin induced liver oxidative DNA damage via the JNK/c-Jun pathway. Wei Sheng yan jiu= Journal of Hygiene Research.

- Bhatta, O.P.; Chand, S.; Chand, H.; Poudel, R.C.; Lamichhane, R.P.; Singh, A.K.; Subedi, N. Imidacloprid poisoning in a young female: a case report. Journal of Medical Case Reports 2023, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sriapha, C.; Trakulsrichai, S.; Tongpoo, A.; Pradoo, A.; Rittilert, P.; Wananukul, W. Acute imidacloprid poisoning in Thailand. Therapeutics and Clinical Risk Management 2020, 1081–1088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sriapha, C.; Trakulsrichai, S.; Intaraprasong, P.; Wongvisawakorn, S.; Tongpoo, A.; Schimmel, J.; Wananukul, W. Imidacloprid poisoning case series: potential for liver injury. Clinical Toxicology 2020, 58, 136–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perananthan, V.; Mohamed, F.; Shahmy, S.; Gawarammana, I.; Dawson, A.; Buckley, N. The clinical toxicity of imidacloprid self-poisoning following the introduction of newer formulations. Clinical Toxicology 2021, 59, 347–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehtap, K.; Ezgi, Ö.; Tugce, B.; Fatma, K.E.; Gul, O. Benomyl induced oxidative stress related DNA damage and apoptosis in H9c2 cardiomyoblast cells. Toxicology In Vitro 2021, 75, 105180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kumar, S.; Baggi, T.R.; Zughaibi, T. Forensic toxicological and analytical aspects of carbamate poisoning–A review. Journal of Forensic and Legal Medicine 2022, 92, 102450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jiao, H.; Yuan, T.; Wang, X.; Zhou, X.; Ming, R.; Cui, H.; Hu, D.; Lu, P. Biochemical, histopathological and untargeted metabolomic analyses reveal hepatotoxic mechanism of acetamiprid to Xenopus laevis. Environmental Pollution 2023, 317, 120765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, Y.; Wu, T.; Han, B.; Yang, S.; Wang, X.; Wang, Q.; Gao, J.; Dai, P. Interaction of acetamiprid, Varroa destructor, and Nosema ceranae in honey bees. Journal of Hazardous Materials 2024, 471, 134380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, Y.-N.; Song, S.; Huang, Y.; Kannan, K.; Sun, H.; Zhang, T. Insights into free and conjugated forms of neonicotinoid insecticides in human serum and their association with oxidative stress. Environment and Health 2023, 1, 121–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costas-Ferreira, C.; Durán, R.; Faro, L.R.F. Toxic Effects of Glyphosate on the Nervous System: A Systematic Review. International Journal of Molecular Sciences 2022, 23, 4605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pirollo, K.F.; Moghe, M.; Guan, M.; Rait, A.S.; Wang, A.; Kim, S.-S.; Chang, E.H.; Harford, J.B. A pralidoxime nanocomplex formulation targeting transferrin receptors for reactivation of brain acetylcholinesterase after exposure of mice to an anticholinesterase organophosphate. International Journal of Nanomedicine 2024, 307–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forman, H.J.; Zhang, H. Targeting oxidative stress in disease: promise and limitations of antioxidant therapy. Nature Reviews Drug Discovery 2021, 20, 689–709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Shehri, S.S. Reactive oxygen and nitrogen species and innate immune response. Biochimie 2021, 181, 52–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Black, H.S. A synopsis of the associations of oxidative stress, ROS, and antioxidants with diabetes mellitus. Antioxidants 2022, 11, 2003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reddy, V.P. Oxidative stress in health and disease. Biomedicines 2023, 11, 2925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, T.; Sun, L.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, Y.; Zheng, J. Imbalanced GSH/ROS and sequential cell death. Journal of Biochemical and Molecular Toxicology 2022, 36, e22942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Valko, M.; Leibfritz, D.; Moncol, J.; Cronin, M.T.; Mazur, M.; Telser, J. Free radicals and antioxidants in normal physiological functions and human disease. The International Journal of Biochemistry and Cell Biology 2007, 39, 44–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valbuena, D.S.; Meléndez-Flórez, M.P.; Villegas, V.E.; Sánchez, M.C.; Rondón-Lagos, M. Daño celular y genético como determinantes de la toxicidad de los plaguicidas. Ciencia en Desarrollo 2020, 11, 25–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kiani, Z.; Asadikaram, G.; Faramarz, S.; Salimi, F.; Ebrahimi, H. Pesticide exposure and Alzheimer’s disease: a case-control Study. Current Alzheimer Research 2022, 19, 892–903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mazari, A.M.; Zhang, L.; Ye, Z.-W.; Zhang, J.; Tew, K.D.; Townsend, D.M. The multifaceted role of glutathione S-transferases in health and disease. Biomolecules 2023, 13, 688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Naseem, S.; Hussain, R.; Ghaffar, A.; Li, K.; Khan, A. Evaluation of DNA damage, biomarkers of oxidative stress, and status of antioxidant enzymes in freshwater fish (Labeo rohita) exposed to pyriproxyfen. Oxidative Medicine and Cellular Longevity 2022, 2022, 5859266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Selmi, S.; Rtibi, K.; Grami, D.; Sebai, H.; Marzouki, L. Malathion, an organophosphate insecticide, provokes metabolic, histopathologic and molecular disorders in liver and kidney in prepubertal male mice. Toxicology Reports 2018, 5, 189–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sukkar, D.; Wagner, L.; Bonnefoy, A.; Falla-Angel, J.; Laval-Gilly, P. Imidacloprid and amitraz differentially alter antioxidant enzymes in honeybee (Apis mellifera) hemocytes when exposed to microbial pathogen-associated molecular patterns. Science of The Total Environment 2025, 969, 178868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hilgert Jacobsen-Pereira, C.; dos Santos, C.R.; Troina Maraslis, F.; Pimentel, L.; Feijó, A.J.L.; Iomara Silva, C.; de Medeiros, G.d.S.; Costa Zeferino, R.; Curi Pedrosa, R.; Weidner Maluf, S. Markers of genotoxicity and oxidative stress in farmers exposed to pesticides. Ecotoxicology and Environmental Safety 2018, 148, 177–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, S.; Kumar, V.; Thakur, S.; Banerjee, B.D.; Rautela, R.S.; Grover, S.S.; Rawat, D.S.; Pasha, S.T.; Jain, S.K.; Ichhpujani, R.L. Paraoxonase-1 genetic polymorphisms and susceptibility to DNA damage in workers occupationally exposed to organophosphate pesticides. Toxicology and Applied Pharmacology 2011, 252, 130–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Andersen, H.R.; Wohlfahrt-Veje, C.; Dalgård, C.; Christiansen, L.; Main, K.M.; Nellemann, C.; Murata, K.; Jensen, T.K.; Skakkebæk, N.E.; Grandjean, P. Paraoxonase 1 polymorphism and prenatal pesticide exposure associated with adverse cardiovascular risk profiles at school age. PLoS One 2012, 7, e36830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Andersen, H.R.; Tinggaard, J.; Grandjean, P.; Jensen, T.K.; Dalgård, C.; Main, K.M. Prenatal pesticide exposure associated with glycated haemoglobin and markers of metabolic dysfunction in adolescents. Environmental Research 2018, 166, 71–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Development, O.f.E.C.-o.a. Test No. 451: Carcinogenicity Studies. https://www.oecd.org/en/publications/2018/06/test-no-451-carcinogenicity-studies_g1gh2955.

- Development, O.f.E.C.-o.a. Test No. 414: Prenatal Developmental Toxicity Study. https://www.oecd.org/en/publications/2018/06/test-no-414-prenatal-developmental-toxicity-study_g1gh293d.

- Development., O.f.E.C.-o.a. Development., O.f.E.C.-o.a. Test No. 416: Two-Generation Reproduction Toxicity. https://www.oecd.org/en/publications/test-no-416-two-generation-reproduction-toxicity_9789264070868-en.

- Ames, B.N.; McCann, J.; Yamasaki, E. Methods for detecting carcinogens and mutagens with the salmonella/mammalian-microsome mutagenicity test. Mutation Research/Environmental Mutagenesis and Related Subjects.

- Development, O.f.E.C.-o.a. Test No. 487: In Vitro Mammalian Cell Micronucleus Test. https://www.oecd.org/content/dam/oecd/en/publications/reports/2023/07/test-no-487-in-vitro-mammalian-cell-micronucleus-test_g1g6fb2a/9789264264861-en.

- Development, O.f.E.C.-o.a. Test No. 473: In Vitro Mammalian Chromosomal Aberration Test. https://www.oecd.org/env/test-no-473-in-vitro-mammalian-chromosomal-aberration-test-9789264264649-en.

- Collins, A.R. The Comet Assay for DNA Damage and Repair: Principles, Applications, and Limitations. Molecular Biotechnology 2004, 26, 249–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moser, V.C. Functional assays for neurotoxicity testing. Toxicologic Pathology 2011, 39, 36–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pope, C.N. Organophosphorus pesticides: do they all have the same mechanism of toxicity? Journal of Toxicology and Environmental Health Part B: Critical Reviews.

- Development, O.f.E.C.-o.a. Test No. 424: Neurotoxicity Study in Rodents. https://www.oecd.org/env/test-no-424-neurotoxicity-study-in-rodents-9789264071025-en.

- Nabi, S.U.; Ali, S.I.; Rather, M.A.; Sheikh, W.M.; Altaf, M.; Singh, H.; Mumtaz, P.T.; Mishra, N.C.; Nazir, S.U.; Bashir, S.M. Organoids: A new approach in toxicity testing of nanotherapeutics. Journal of Applied Toxicology,.

- Song, L.; Zan, C.; Liang, Z.; Chen, X.; Li, J.; Ren, N.; Shi, Y.; Zhang, M.; Lan, L.; Li, H. Potential value of FAPI PET/CT in the detection and treatment of fibrosing mediastinitis: preclinical and pilot clinical investigation. Molecular Pharmaceutics 2023, 20, 4307–4318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Yan, M.; Zhou, J.; Song, W.; Xiao, Y.; Cui, C.; Gao, W.; Ke, F.; Zhu, J.; Gu, Z. Delivery of acetamiprid to tea leaves enabled by porous silica nanoparticles: Efficiency, distribution and metabolism of acetamiprid in tea plants. BMC Plant Biology 2021, 21, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ireland, D.; Zhang, S.; Bochenek, V.; Hsieh, J.-H.; Rabeler, C.; Meyer, Z.; Collins, E.-M.S. Differences in neurotoxic outcomes of organophosphorus pesticides revealed via multi-dimensional screening in adult and regenerating planarians. Frontiers in Toxicology 2022, 4, 948455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kasteel, E.E.; Nijmeijer, S.M.; Darney, K.; Lautz, L.S.; Dorne, J.L.C.; Kramer, N.I.; Westerink, R.H. Acetylcholinesterase inhibition in electric eel and human donor blood: an in vitro approach to investigate interspecies differences and human variability in toxicodynamics. Archives of Toxicolog 2020, 94, 4055–4065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keresteš, O.; Pohanka, M. Affordable portable platform for classic photometry and low-cost determination of cholinesterase activity. Biosensors 2023, 13, 599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akiyama, H.; Iwasaki, Y.; Ito, R. Basic Principles for Setting MRLs for Pesticides in Food Commodities in Japan. Food Safety 2024, 12, 34–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tanaka, R. Setting of Maximum Residue Limits (MRLs) for Pesticides in Foods. Yakugaku zasshi: Journal of the Pharmaceutical Society of Japan.

- Díaz-Vallejo, J.; Barraza-Villarreal, A.; Yañez-Estrada, L.; Hernández-Cadena, L. Plaguicidas en alimentos: riesgo a la salud y marco regulatorio en Veracruz, México. Salud Pública de México.

- Jia, Q.; Liao, G.-q.; Chen, L.; Qian, Y.-z.; Yan, X.; Qiu, J. Pesticide residues in animal-derived food: Current state and perspectives. Food Chemistry 2024, 438, 137974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, S.; Yu, H.; Guo, Y.; Xie, Y.; Cheng, Y.; Qian, H.; Yao, W. Recent advance in probiotics for the elimination of pesticide residues in food and feed: mechanisms, product toxicity, and reinforcement strategies. Critical Reviews in Food Science and Nutrition 2024, 64, 12025–12039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arbo, M.D.; Garcia, S.C.; Sarpa, M.; Junior, F.M.D.S.; Nascimento, S.N.; Garcia, A.L.H.; Da Silva, J. Brazilian workers occupationally exposed to different toxic agents: A systematic review on DNA damage. Mutation Research/Genetic Toxicology and Environmental Mutagenesis, 5035. [Google Scholar]

- Scorza, F.A.; Finsterer, J.; Beltramim, L.; Bombardi, L.M.; de Almeida, A. TELOMERE LENGTH AND PESTICIDE RESIDUES IN FOOD-A CAUSAL LINK? Journal of the Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics, 2212. [Google Scholar]

- Rodríguez-López, A.; Mejía-Saucedo, R.; Calderón-Hernández, J.; Labrada-Martagón, V.; Yáñez-Estrada, L. Alteraciones del ciclo menstrual de adolescentes expuestas no ocupacionalmente a una mezcla de plaguicidas de una zona agrícola de San Luis Potosí, México. Estudio piloto. Revista Internacional de Contaminación Ambiental, 1010. [Google Scholar]

- de Andrade, J.C.; Galvan, D.; Kato, L.S.; Conte-Junior, C.A. Consumption of fruits and vegetables contaminated with pesticide residues in Brazil: A systematic review with health risk assessment. Chemosphere 2023, 322, 138244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, B.K.; Kwon, S.H.; Yeom, M.S.; Joo, K.S.; Heo, M.J. Detection of pesticide residues and risk assessment from the local fruits and vegetables in Incheon, Korea. Scientific Reports 2022, 12, 9613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qi, S.-Y.; Xu, X.-L.; Ma, W.-Z.; Deng, S.-L.; Lian, Z.-X.; Yu, K. Effects of organochlorine pesticide residues in maternal body on infants. Frontiers in Endocrinology 2022, 13, 890307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daisley, B.A.; Chernyshova, A.M.; Thompson, G.J.; Allen-Vercoe, E. Deteriorating microbiomes in agriculture - the unintended effects of pesticides on microbial life. Microbiome Research Reports 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arora, S.; Murmu, G.; Mukherjee, K.; Saha, S.; Maity, D. A comprehensive overview of nanotechnology in sustainable agriculture. Journal of Biotechnology 2022, 355, 21–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Usman, M.; Farooq, M.; Wakeel, A.; Nawaz, A.; Cheema, S.A.; ur Rehman, H.; Ashraf, I.; Sanaullah, M. Nanotechnology in agriculture: Current status, challenges and future opportunities. Science of The total Environment 2020, 721, 137778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kah, M.; Kookana, R.S.; Gogos, A.; Bucheli, T.D. A critical evaluation of nanopesticides and nanofertilizers against their conventional analogues. Nature Nanotechnology 2018, 13, 677–684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Münzel, T.; Kuntic, M.; Lelieveld, J.; Aschner, M.; Nieuwenhuijsen, M.J.; Landrigan, P.J.; Daiber, A. The links between soil and water pollution and cardiovascular disease. Atherosclerosis 2025, 119160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.; Shan, C.; Zhang, P.; Zhao, W.; Zhu, G.; Sun, Y.; Wang, Q.; Jiang, Y.; Shakoor, N.; Rui, Y. The combination of nanotechnology and potassium: applications in agriculture. Environmental Science and Pollution Research 2024, 31, 1890–1906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Monteiro, R.A.; Camara, M.C.; de Oliveira, J.L.; Campos, E.V.R.; Carvalho, L.B.; de Freitas Proenca, P.L.; Guilger-Casagrande, M.; Lima, R.; do Nascimento, J.; Gonçalves, K.C. Zein based-nanoparticles loaded botanical pesticides in pest control: An enzyme stimuli-responsive approach aiming sustainable agriculture. Journal of Hazardous Materials 2021, 417, 126004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ma, Y.; Li, L.; Zhao, R.; Sun, Z.; Wang, Y.; Yu, M.; Pan, S.; Guo, X.; Xu, Y.; Wang, H. Nanoencapsulation-based fabrication of eco-friendly pH-responsive pyraclostrobin formulations with enhanced photostability and adhesion to leaves. Journal of Environmental Chemical Engineering 2023, 11, 109688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.; Han, Y.; Gao, T.; Zhang, J.; Xu, D.-X.; Wāng, Y. Insecticidal activity of metallic nanopesticides synthesized from natural resources: A review. Environmental Chemistry Letters 2023, 21, 1141–1176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bueno, V.; Wang, P.; Harrisson, O.; Bayen, S.; Ghoshal, S. Impacts of a porous hollow silica nanoparticle-encapsulated pesticide applied to soils on plant growth and soil microbial community. Environmental Science: Nano, 1476. [Google Scholar]

- Agredo-Gomez, A.; Molano-Molano, J.; Portela-Patiño, M.; Rodríguez-Páez, J. Use of ZnO nanoparticles as a pesticide: In vitro evaluation of their effect on the phytophagous Puto barberi (mealybug). Nano-Structures and Nano-Objects.

- Badawy, A.A.; Abdelfattah, N.A.; Salem, S.S.; Awad, M.F.; Fouda, A. Efficacy assessment of biosynthesized copper oxide nanoparticles (CuO-NPs) on stored grain insects and their impacts on morphological and physiological traits of wheat (Triticum aestivum L.) plant. Biology.

- El-Ansary, M.S.M.; Hamouda, R.A.; Elshamy, M.M. Using biosynthesized zinc oxide nanoparticles as a pesticide to alleviate the toxicity on banana infested with parasitic-nematode. Waste and Biomass Valorization 2022, 13, 405–415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, R.; Malik, P.; Rani, R.; Solanki, R.; Ameta, R.K.; Malik, V.; Mukherjee, T.K. Recent progress on nanoemulsions mediated pesticides delivery: insights for agricultural sustainability. Plant Nano Biology 2024, 8, 100073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Zhang, Y.; Cao, C.; Zhao, P.; Huang, Q.; Cao, L. Optimization and characterization of pyraclostrobin nanoemulsion for pesticide delivery: Improving activity, reducing toxicity, and protecting ecological environment. Colloids and Surfaces A: Physicochemical and Engineering Aspects, 1340. [Google Scholar]

- Wei, N.; Hou, C.; Liu, Z.; Liang, Q.; Lv, Z.; Meng, X.; Feng, J. Preparation of fenpropathrin nanoemulsions for eco-friendly management of Helicoverpa armigera: Improved insecticidal activity and biocompatibility. Colloids and Surfaces A: Physicochemical and Engineering Aspects, 1304. [Google Scholar]

- Abdelaal, K.; Essawy, M.; Quraytam, A.; Abdallah, F.; Mostafa, H.; Shoueir, K.; Fouad, H.; Hassan, F.A.; Hafez, Y. Toxicity of essential oils nanoemulsion against Aphis craccivora and their inhibitory activity on insect enzymes. Processes 2021, 9, 624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zia, R.; Taj, A.; Younis, S.; Bukhari, S.Z.; Latif, F.; Feroz, Y.; Fatima, K.; Imran, A.; Bajwa, S.Z. , Application of nanosensors for pesticide detection. In Nanosensors for Smart Agriculture, Elsevier: 2022; pp 259-302.

- Beegum, S.; Das, S. , Nanosensors in agriculture. In Agricultural nanobiotechnology, Elsevier: 2022; pp 465-478.

- Wu, J.; Liu, H.; Chen, W.; Ma, B.; Ju, H. Device integration of electrochemical biosensors. Nature Reviews Bioengineering 2023, 1, 346–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, F.; Dwivedi, S.; Shaalan, N.M.; Kumar, S.; Arshi, N.; Alshoaibi, A.; Husain, F.M. Development of selenium nanoparticle based agriculture sensor for heavy metal toxicity detection. Agriculture 2020, 10, 610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, M.; Pang, J.; Wang, Y.; Bi, C.; Xu, Z.; Shen, Y.; Yang, J.; Wang, H.; Sun, Y. Nanobodies-based colloidal gold immunochromatographic assay for specific detection of parathion. Analytica Chimica Acta 2024, 1310, 342717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Furizal, F.; Ma'arif, A.; Firdaus, A.A.; Rahmaniar, W. Future potential of E-nose technology: A review. International Journal of Robotics and Control Systems 2023, 3, 449–469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, J.; Xu, J. Applications of electronic nose (e-nose) and electronic tongue (e-tongue) in food quality-related properties determination: A review. Artificial Intelligence in Agriculture 2020, 4, 104–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, M.M.; Hashim, N.; Abd Aziz, S.; Lasekan, O. Principles and recent advances in electronic nose for quality inspection of agricultural and food products. Trends in Food Science and Technology 2020, 99, 1–10. [Google Scholar]

- Moshayedi, A.J.; Sohail Khan, A.; Hu, J.; Nawaz, A.; Zhu, J. E-nose-driven advancements in ammonia gas detection: a comprehensive review from traditional to cutting-edge systems in indoor to outdoor agriculture. Sustainability 2023, 15, 11601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moo-Muñoz, A.J.; Azorín-Vega, E.P.; Ramírez-Durán, N.; Moreno-Pérez, M.P. Estado de la producción y consumo de plaguicidas en méxico†[state of the production and consumption of pesticides in México. Tropical and Subtropical Agroecosystems 2020, 23, 43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Institute for Agricultural and Food Research and Technology, I.; Molteni, R.; Alonso-Prados, J.L. National Institute for Agricultural and Food Research and Technology, I.; Molteni, R.; Alonso-Prados, J.L. Study of the different evaluation areas in the pesticide risk assessment process. EFSA Journal, 1811. [Google Scholar]

- Kudsk, P.; Mathiassen, S.K. Pesticide regulation in the European Union and the glyphosate controversy. Weed Science 2020, 68, 214–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- EPA, U.S.E.P.A. Federal Insecticide, Fungicide, and Rodenticide Act (FIFRA) and Federal Facilities. https://www.epa.

- Geissen, V.; Silva, V.; Lwanga, E.H.; Beriot, N.; Oostindie, K.; Bin, Z.; Pyne, E.; Busink, S.; Zomer, P.; Mol, H.; Ritsema, C.J. Cocktails of pesticide residues in conventional and organic farming systems in Europe – Legacy of the past and turning point for the future. Environmental Pollution 2021, 278, 116827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Union, E. Reglamento (ce) n o 1107/2009 del Parlamento Europeo y del Consejo de 21 de octubre de 2009 relativo a la comercialización de productos fitosanitarios y por el que se derogan las Directivas 79/117/CEE y 91/414/CEE del Consejo. https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/ES/TXT/? 3200. [Google Scholar]

- Bejarano González, F.; AguileraMárquez, D.; Álvarez Solís, J.D.; Arámbula Meraz, E.; Arellano Aguilar, O.; Bastidas Bastidas, P.d.J.; Beltrán Camacho, V.d.l.A.; Bernardino Hernández, H.U.; Betancourt Lozano, M.; Calderón Vázquez, C.L. Los plaguicidas altamente peligrosos en México. Texcoco: RAPAM.

| Pesticide | Type | Target Organism | Associate damage | DL50 | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Parathion /Methyl parathion | Organophosphate | Herbicide | In vivo studies have linked its use to the development of heart disease, an increase in CAT, TBARS, and GPx biomarkers, and a decrease in SOD, resulting in an overload of oxidative stress, alterations in acetylcholinesterase levels, and overstimulation of the central nervous system. | 6-14 mg/kg /2-30 mg/kg | [35,36] |

| Rotencidal | Coumarin | Bromadiolone | At low concentrations it has been linked to the appearance of oxidative stress in short exposures and the destabilization of biomolecules, at acute exposures bromadiolone has been linked to the inhibition of the carboxylation of vitamin K-dependent coagulation factors (II, VII, IX and X) making an anticoagulant effect, it is also widely related to the deterioration of the intestinal mucosa and bleeding in the digestive and urinary tract. There have been cases related to exposure to bromadiolone and the development of diseases of the central nervous system or conditions affecting the brain mass, such as leukoencephalopathy. | 1.125 mg/kg | [37,38,39,40] |

| Carbofuran | Carbamates | Herbicide and insecticide | After exposure to humans, a considerable increase in oxidative stress has been reported in several organs, including the liver, brain, kidney, and heart, which leads to the propagation of necrosis in hepatic and nephrotic cells. | 8-14 mg/kg | [41,42,43] |

| 2,4-D | Phenoxyacetic Acid | Herbicide | It is a widely used compound that causes significant damage to the environment and humans. In addition to the increase in oxidative stress and destabilization of biomolecules, it has been highly related to the inhibition of growth in cells and tissues; its effects have been studied in different in vivo models where they found a behavioral pattern in terms of neurotoxicity, a decrease in motor skills was observed, biochemically it showed a decrease in serotonin levels or a decrease in dopamine levels and its metabolites depending on the brain area analyzed. | 639-764 mg/kg | [44,45] |

| Cypermethrin | Pyrethroid | Acaracide | Often used in mixtures, its acute and subacute exposure causes clinical symptoms such as pneumonia, acute kidney injury, tearing, acute respiratory failure, and diarrhea. Cypermethrin primarily acts by delaying the closure of voltage-sensitive sodium channels. Most of the effects caused by poisoning with this pesticide are neurotoxic, particularly in the respiratory and gastrointestinal tracts. Cases of cardiotoxic conditions have been reported, but these are insufficient to associate them with cypermethrin poisoning. | 240-4123 mg/kg | [46,47,48,49] |

| Imidacloprid | Neonicotinoid | Insecticide | The most widely used neonicotinoid in the world is known to produce oxidative stress upon exposure. It has also been observed that, in the case of oral ingestion, the main symptoms and associated damage are gastrointestinal without corrosive lesions and neurological effects, such as dyspnea, coma, and diaphoresis. There is a particular relationship between imidacloprid poisoning and the development of various types of liver damage, which sometimes occurs late. | 450-650 mg/kg | [50,51,52,53] |

| Benomyl | Carbamates | Fungicide | Linked to the generation of systemic oxidative stress. In vitro studies in rat cardiomyoblasts (H9c2) demonstrated a 2-fold increase in ROS and glutathione levels measured in cells exposed to benomyl compared to controls. Exposure to benomyl has been shown to induce apoptosis, oxidative stress, and DNA damage. | >10000 mg/kg | [54,55] |

| Acetamiprid | Neonicotinoid | Insecticide | After the severe oxidative stress generated by this pesticide is linked to genotoxic damage and the formation of cleavages in tRNA due to the changes it generates in biomolecules, isolated cases have been reported where poisoning with acetamiprid triggered lactic acidosis, hyperglycemia, and intestinal obstruction. | 217 mg/kg | [56,57,58] |

| Glyphosate | Organophosphate | Herbicide | Exposure to pesticides during the early stages of development can severely disrupt normal cell growth by interfering with several critical signaling pathways, leading to significant changes in cell differentiation, neuronal development, and myelination. Furthermore, glyphosate appears to have a notable toxic effect on neurotransmission, generating oxidative stress, neuroinflammation, and mitochondrial dysfunction, which can result in neuronal death through mechanisms such as autophagy, necrosis, or apoptosis. These neurotoxic effects are also associated with the development of behavioral disorders and impaired motor skills. | 4320 mg/kg | [59,60] |

| Test name | Evaluated focus | Basis | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

|

Acute Toxicity Evaluation (Oral, dermal, inhalation) • LD50 • LC50 • Skin irritation test (Draize Skin Test) • Eye irritation test (Draize Eye Test) • Acute inhalation test (Exposure of animal models in chambers) |

Acute toxicity tests. | Designed to assess the immediate effects of exposure to different pesticides. Tests are classified by exposure routes and evaluated within 24 to 96 hours. | [77,78,79] |

|

Chronic Toxicity Evaluation • Carcinogenicity studies (OECD TG 451) • Prenatal developmental toxicity study (OECD TG 414) • Reproductive toxicity study (OECD TG 416) |

Chronic toxicity tests. | Chronic toxicity tests evaluate the effects of prolonged and repeated low-dose exposures. | [77,78,79] |

|

Genotoxicity Tests • Ames test • Micronucleus test (OECD TG 487) • Comet assay • Chromosomal aberration test (OECD TG 473) |

Toxicological studies based on the pesticide's ability to damage DNA and cause point mutations. | Due to the high reactivity of pesticides, they can induce mutations, chromosomal aberrations, or DNA strand breaks. These tests encompass the main mechanisms of DNA damage caused by pesticides. |

[80,81,82,83] |

|

Neurotoxicity Studies • Behavioral tests • Measurement of cholinesterase inhibition • Functional tests in rats or mice (Functional Observational Battery) |

Evaluation of pesticide effects on the central nervous system, especially those caused by organophosphates and carbamates. | By detecting inhibition of key enzymes in the central nervous system, it is possible to identify motor or behavioral alterations in animal models and relate them to cognitive impairment. |

[84,85,86] |

|

Toxicokinetic Assays • ADME tests (Absorption, Distribution, Metabolism, and Excretion) • Radio-labeled isotopes • In vitro models (Cell cultures simulating liver metabolism) |

General evaluation of the pesticide. | Analyzing ADME helps understand how long a pesticide can remain reactive in the body and where it might accumulate. | [87,88,89] |

|

Biochemical Tests • Cholinesterase inhibition (Ellman test) • Alterations in liver enzymes (Alanine transaminase and aspartate transaminase) |

Evaluation of alterations in enzymatic systems based on the central nervous system. | These tests assess the pesticide's effects on specific metabolic and enzymatic systems, usually in the liver or nervous system, depending on the pesticide's nature. | [90,91,92] |

| Pesticide | Study | Conclusion | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mixtures of organochlorine and organophosphate pesticides, most notably 2,4-DDE, 4,4-DDE, g-BHC, and b-BHC. | A group of 29 adolescents was studied, with 75% of them belonging to families of agricultural day laborers. Additionally, 43.7% had gardens at home, and 64.28% used pesticides. The study linked interactions with pesticides to menstrual cycle disruption. |

In serum levels of sexual hormones, more than 40% of adolescents presented alterations in their hormonal profile, and 96.9% of adolescents had detectable plasma levels of pesticides. However, some indications suggest a relationship between 4,4-DDE in plasma and alterations in the menstrual cycle; no statistically significant differences were found. This may be due to the group chosen and the time designated for the study. | [100] |

| More than 100 pesticides classified as carcinogenic by the EPA | Meta-analysis of the presence of pesticides in different fruits and vegetables | Within the study, various pesticides found in fruits and vegetables, including grapes, mangoes, tomatoes, strawberries, apples, and peppers, were compiled. These pesticides are widely linked to the development of chronic degenerative diseases, alterations in the endocrine system, and disruptions in reproductive health in both adults and children. | [101] |

| 91 samples were identified as exceeding the permitted MRLs in Korea, including Chlorfenapyr, Procymidone, Etofenprox, Pendimethalin and Fluopyram | 1,146 fruits and vegetables were collected from the Korean market and tested for 15 pesticides of interest. | Although the identified pesticides are related to damage to the central nervous system, endocrine system, and liver conditions, it is necessary to note that it was only 8.9% of the total samples, compared to other countries, where this percentage is lower. | [102] |

| Pesticides such as DEE, DDT, dieldrin, and HCB | The factors influencing the presence of organochlorine pesticides in breast milk and the resulting damage to children were addressed. | Organochlorine pesticides can act as endocrine disruptors, and estrogen-inducing pesticides can accumulate with exposure to water, soil, environmental exposure, or food. Levels of HCB or DDT residues have been linked to decreased birth weight and head circumference. The opposite effect can occur with certain OGC pesticides, thanks to lipogenesis. | [103] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).