Submitted:

13 February 2025

Posted:

17 February 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

Aims and Scope

2. Methods and Materials

2.1. Literature Current State of PFAS Contamination in Europe

2.1.1. Sources of Contamination

2.1.2. Industrial Emissions

2.1.3. Agricultural Practices

2.1.4. Waste Mismanagement

Regulatory Landscape

The European Green Deal

The REACH Regulation

Policy Gaps and Opportunities

Extent of Contamination

Geographic Hotspots

Bioaccumulation in Crops and Water Sources

2.2. Methodology

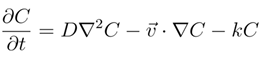

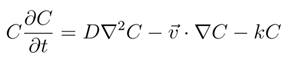

Innovative Mathematical Modeling for PFAS Spread

- ○

- C = PFAS concentration,

- ○

- D = diffusion coefficient,

- ○

= advection velocity (water flow),

= advection velocity (water flow),- ○

- k = degradation rate (assumed negligible for PFAS due to persistence).

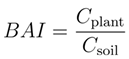

- ○

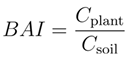

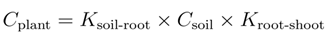

- Cplant = PFAS concentration in plant tissues,

- ○

- Csoil = PFAS concentration in soil.

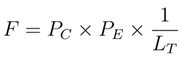

- ○

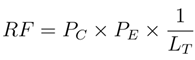

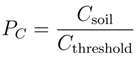

- PC = contamination probability,

- ○

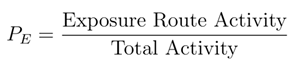

- PE = exposure likelihood (human or ecological),

- ○

- LT = latency threshold for health effects.

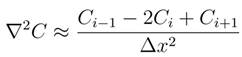

Detailed Modeling Approach

- C(x, y, z, t): PFAS concentration in soil or water at location (x, y, z) and time t,

- D: Diffusion coefficient (m2/s),

: Laplacian operator describing diffusion,

: Laplacian operator describing diffusion, : Advection velocity vector (m/s),

: Advection velocity vector (m/s),- k: Decay constant (/s)

- Surface Boundary (z=0z = 0): PFAS concentration is highest at the source. C(x, y, 0, t) = Csourcee−t/trelease where trelease is the time for PFAS release.

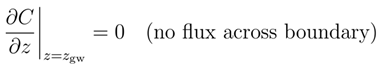

- Groundwater Interaction (z = zgw): PFAS mixing with groundwater..

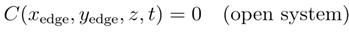

- Domain Edges (x,yx, y boundaries)Domain Edges (x,yx, y boundaries):

.

.

- Cplant: PFAS concentration in plant tissue,

- Csoil: PFAS concentration in the root zone.

- Leafy vegetables: High Kroot-shoot,

- Root vegetables: High Ksoil-root.

- PC: Probability of contamination,

- PE: Exposure probability,

- LT4: Latency threshold (time before observable health impacts).

- PC: Based on contamination levels from transport models:

Where Cthreshold is the regulatory limit for PFAS in soil.

Where Cthreshold is the regulatory limit for PFAS in soil. - PE: Exposure likelihood considering human or ecological interactions:

- LT: Estimated from toxicological studies of PFAS.

-

Diffusion Coefficient (D):

- ○

- Range: 10−6 to 10−9 m2/s,

- ○

- Impact: Faster or slower PFAS spread.

-

Advection Velocity (

):

):- ○

- Range: 0.01 to 1.0 m/s

- ○

- Impact: Directional PFAS migration.

-

Uptake Coefficients (Ksoil-root, Kroot-shoot):

- ○

- Adjust for crop type and soil conditions.

-

Transport Simulation:

- ○

- Define spatial domain (Lx, Ly, Lz) and grid resolution (Nx, Ny, Nz).

- ○

- Apply FDM for spatial derivatives.

-

Bioaccumulation Prediction:

- ○

- Link Csoil from transport model to tCplant.

-

Risk Mapping:

- ○

- Use GIS tools to visualize RFRF spatially.

- Validation data from European farmlands (e.g., PFAS hotspots in Belgium and Italy).

- Compare modeled concentrations (Csoil, Cplant) with measured values.

- Use case studies to refine parameters and verify accuracy.

Case Studies, Tools and Applications

Phytoremediation Success in Denmark

- Objective: Mitigate PFAS contamination in soils irrigated with PFAS-laden wastewater.

-

Methodology:

- ○

- Willows (Salix spp.) and poplars (Populus spp.) were planted on contaminated sites.

- ○

-

The trees were monitored for PFAS uptake in roots, shoots, and leaves.Outcomes:

-

- ○

- PFAS accumulation rates in plant tissues averaged 15% for perfluorooctane sulfonate (PFOS) and 10% for perfluorooctanoic acid (PFOA) over two growing seasons.

- ○

- Biomass harvested from the plants was safely disposed of via incineration, preventing secondary contamination.

- ○

- The cost of phytoremediation was significantly lower than that of other methods: approximately €15,000 per hectare, compared to €50,000 for chemical extraction (Goldenman et al., 2019).

- Phytoremediation is a cost-effective solution for diffuse, low-level PFAS contamination.

- The approach is eco-friendly and enhances soil health over time.

Comparative Analyses Across Europe

- Soil Type Suitability: Effective in sandy and loamy soils, where PFAS mobility is higher.

- Climate Considerations: High humidity levels in temperate climates enhance the efficiency of plasma-generated reactive species.

- Scalability: Plasma systems can be adapted for mobile units, enabling in-situ treatment in remote areas.

- Soil Type Suitability: Performs well in organic-rich soils, which support robust plant growth.

-

Long-Term Benefits:

- ○

- Restores soil ecosystems while reducing PFAS levels.

- ○

- Provides additional economic benefits through biomass production for energy or other uses.

- A pilot project in Lombardy, Italy, used hybrid approaches combining phytoremediation and bioaugmentation. Engineered microbes were introduced into the root zones of poplars to enhance PFAS degradation. Results showed a 50% reduction in PFAS levels in soil within two years (Liu et al., 2019).

Challenges and Recommendations

- Scalability: Adapting these technologies for large-scale contamination requires significant investment.

- Timeframes: Phytoremediation is slower than other techniques, making it less suitable for urgent remediation needs.

- Integration of Methods: Combining techniques, such as plasma remediation with adsorption or phytoremediation with bioaugmentation, yields better results but increases complexity.

- Expand pilot projects to regions with different soil and climate conditions, such as Southern Europe.

- Integrate IoT sensors and AI-driven models to monitor real-time remediation progress and optimize resource allocation.

- Increase public and private funding to scale up these technologies for widespread use.

3. Results

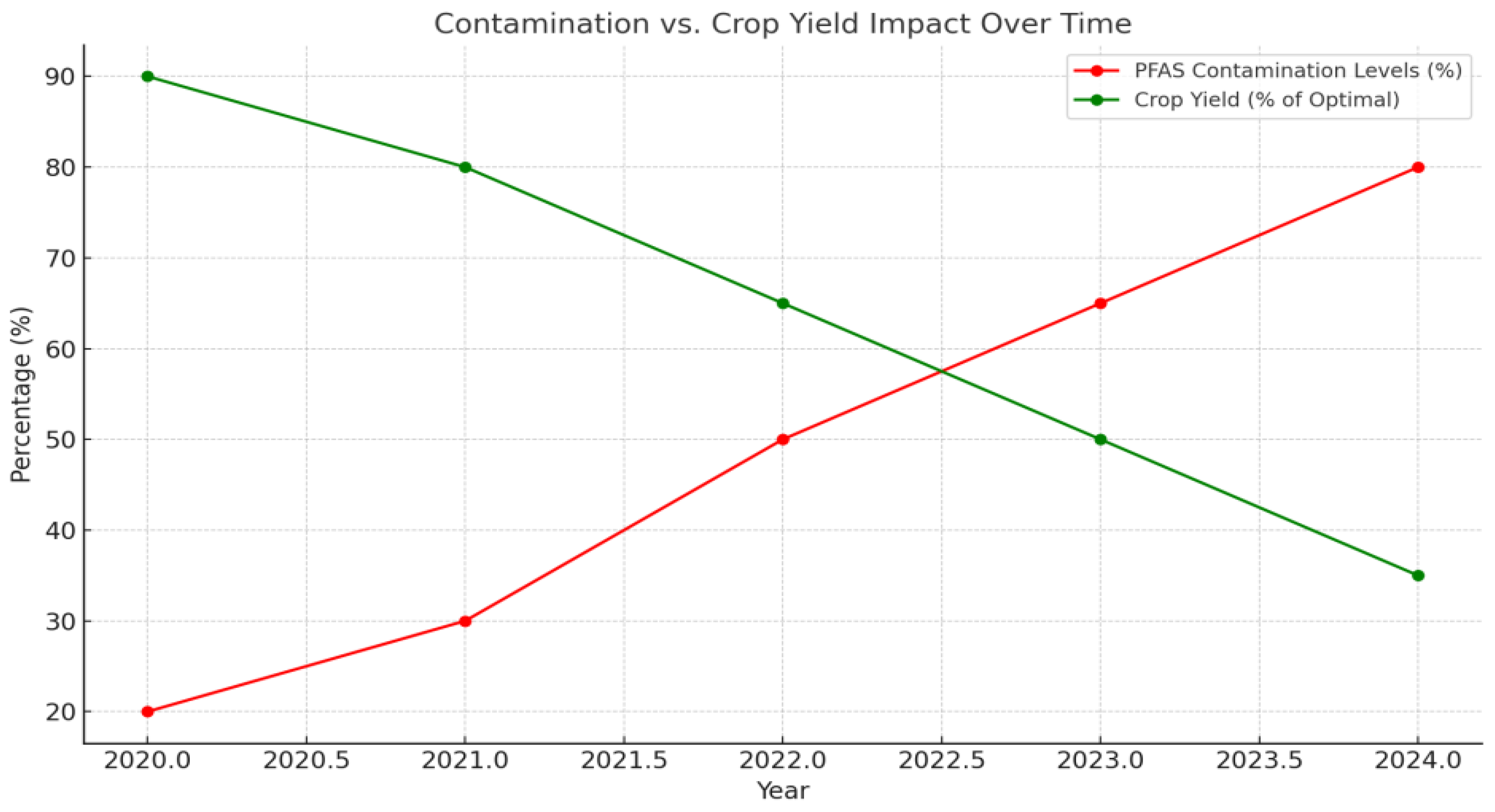

3.1. Impact on the Future Food Supply

Bioaccumulation in Crops

Mechanisms of PFAS Uptake:

Livestock Contamination

- ○

- Lower crop yields due to PFAS-induced growth inhibition.

- ○

- Decreased livestock productivity from health impacts, including reduced milk and egg yields.

- ○

- Farmers face high costs to remediate contaminated soils and water sources.

- ○

- Complying with stricter safety standards for PFAS in food products adds further financial burdens.

- ○

- Increased public health costs arise from exposure to PFAS-contaminated food linked to conditions such as cancer, thyroid disorders, and developmental issues (Goldenman et al., 2019).

| Category | PFAS Uptake Pathways | Impacts on Yield/Quality | Economic Impact |

| Crops | Soil-to-root transfer; irrigation water | Reduced grain size (20%), lower protein content | Loss of income from reduced yield |

| Dairy | Contaminated feed and water | Elevated PFAS levels in milk; export restrictions | Market losses from unsellable products |

| Meat | Feed and water contamination | Muscle tissue contamination; health risks to consumers | Decreased market demand |

| Eggs | PFAS in poultry feed | High PFAS concentration in eggs | Regulatory non-compliance fines |

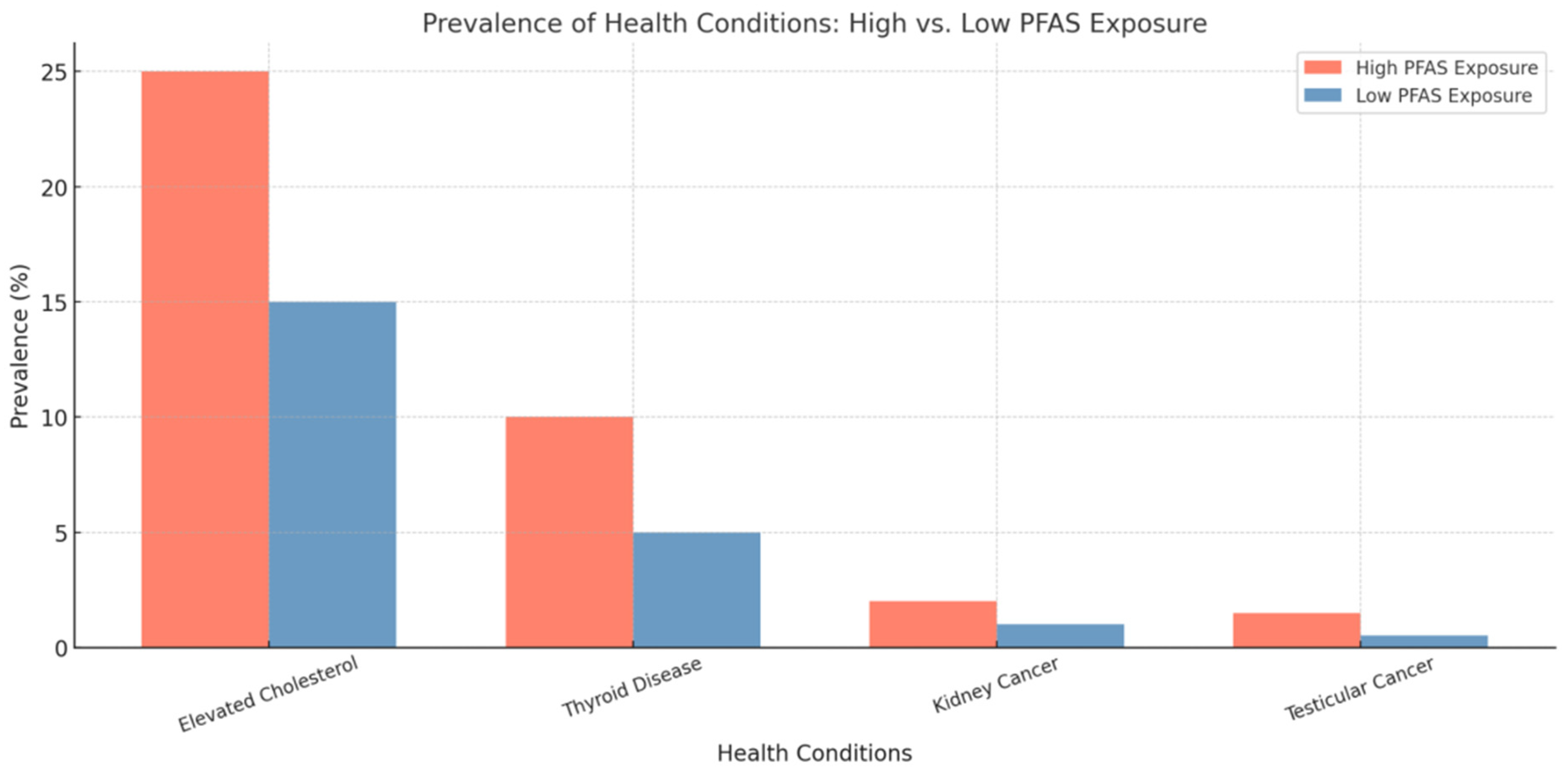

| Health Condition | High Exposure (%) | Low Exposure (%) |

| Elevated Cholesterol | 25 | 15 |

| Thyroid Disease | 10 | 5 |

| Kidney Cancer | 2 | 1 |

| Testicular Cancer | 1.5 | 0.5 |

- ○

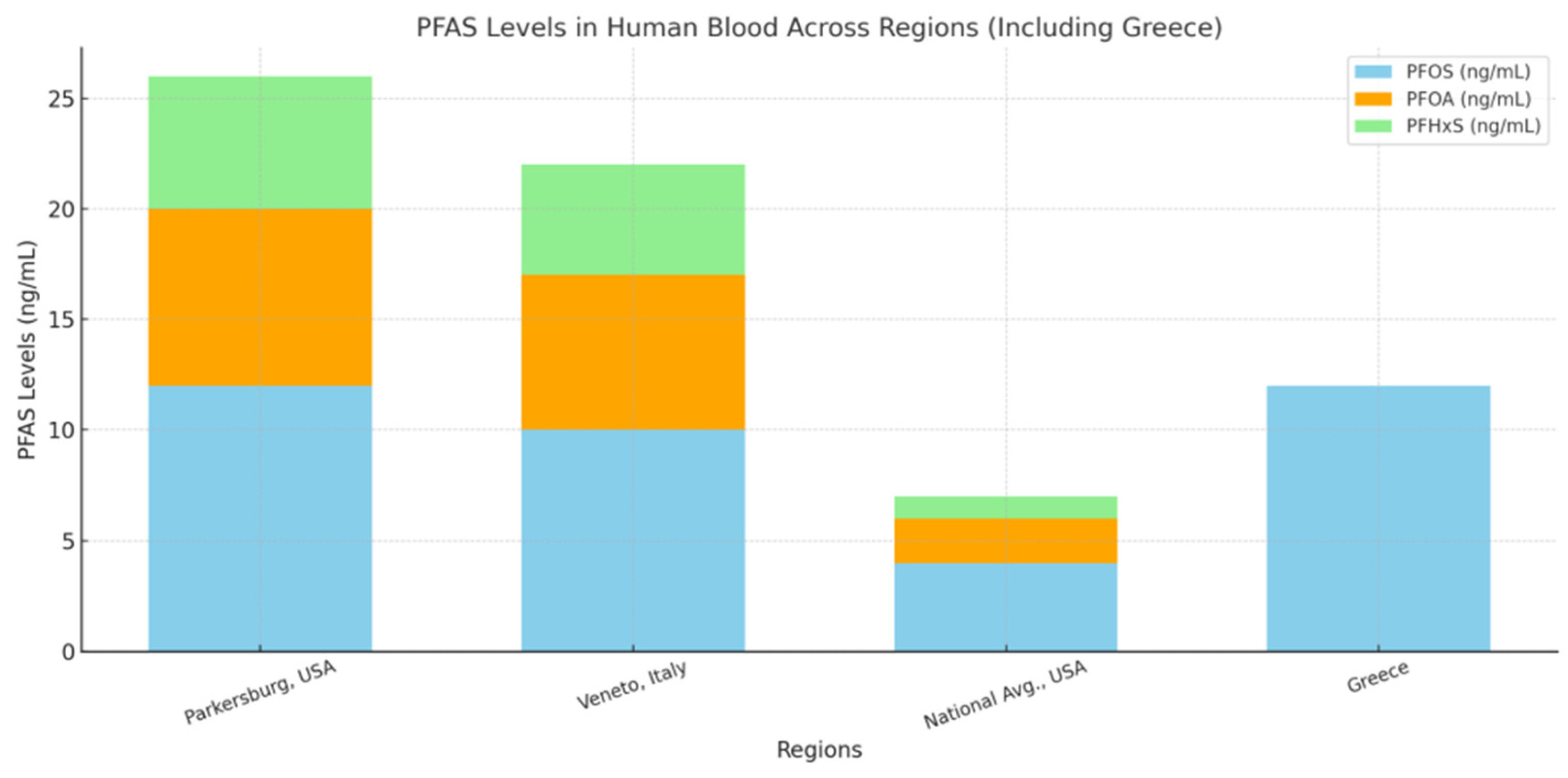

- Conducted PFAS exposure assessments in highly contaminated regions across the USA, such as Parkersburg, West Virginia, where chemical manufacturing facilities have operated for decades.

- ○

- Focused on the Veneto region, known for widespread PFAS contamination due to industrial discharges into water systems.

- ○

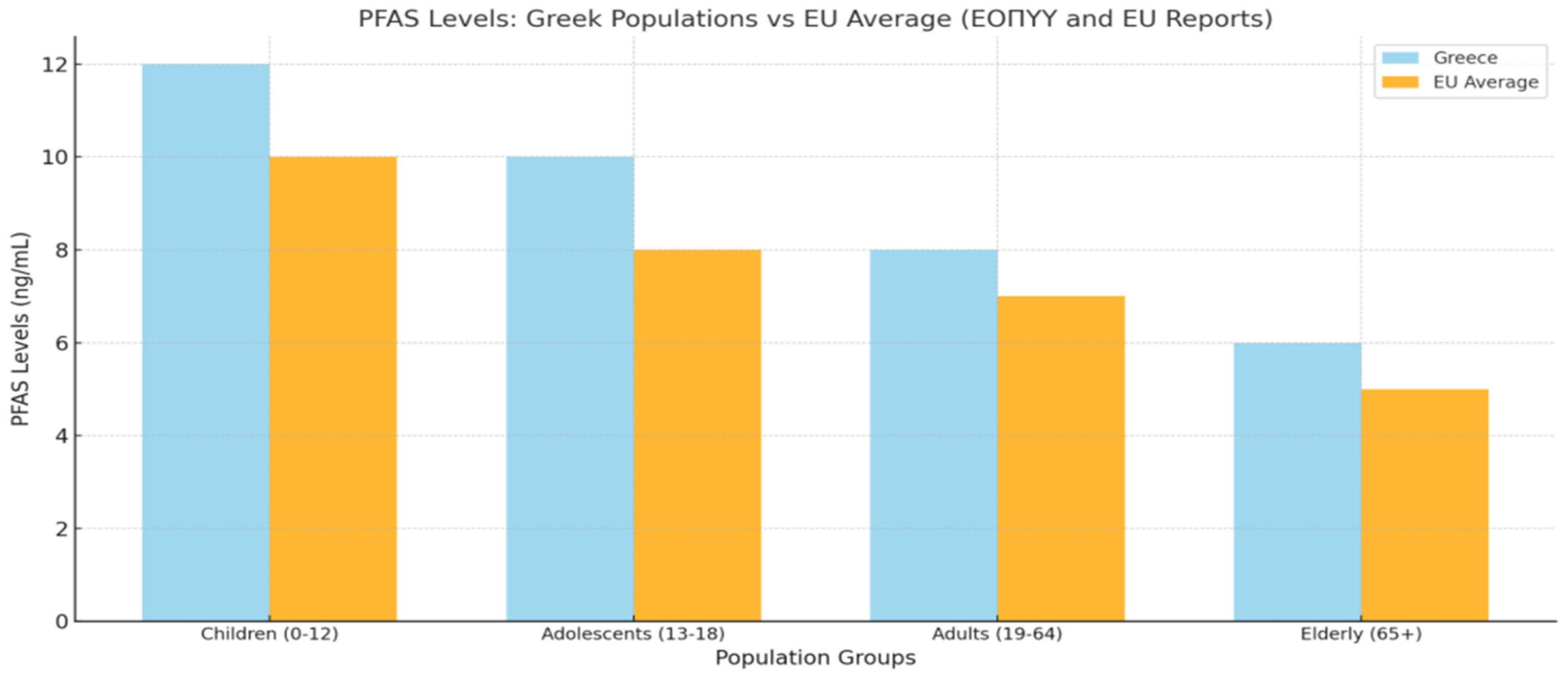

- Reported elevated PFAS levels among Greek populations, identifying age-specific vulnerabilities in children, adolescents, adults, and the elderly.

| Region | PFOS (ng/mL) | PFOA (ng/mL) | PFHxS (ng/mL) |

| Parkersburg, USA | 12 | 8 | 6 |

| Veneto, Italy | 10 | 7 | 5 |

| National Avg., USA | 4 | 2 | 1 |

| Greek Avg. (ΕOPΥΥ) | 12 | Not Reported | Not Reported |

-

PFOS (Perfluorooctane Sulfonate):

- ○

- Found in high concentrations in industrial regions due to its use in surface treatments, firefighting foams, and coatings.

- ○

- Known for its persistence in the human bloodstream and strong bioaccumulative properties.

-

PFOA (Perfluorooctanoic Acid):

- ○

- Historically linked to nonstick cookware and waterproof clothing. Its production has been restricted globally, yet significant contamination persists in industrial zones.

-

PFHxS (Perfluorohexane Sulfonate):

- ○

- A less well-known compound but prevalent in firefighting foams. It poses a high risk of bioaccumulation, particularly in aquatic environments.

-

Parkersburg, USA:

- ○

- Proximity to chemical manufacturing facilities (e.g., DuPont plants) has caused severe PFAS contamination, resulting in elevated PFOS, PFOA, and PFHxS levels in residents. Data from the C8 Health Project showed that long-term exposure to these compounds exceeded national averages, correlating with increased health risks like kidney and testicular cancer.

-

Veneto, Italy:

- ○

- Industrial discharges into local waterways have led to high PFAS levels in groundwater, significantly impacting drinking water supplies. Populations in Veneto exhibit PFOS and PFOA concentrations double that of the U.S. national average, primarily due to legacy pollution from chemical industries.

-

National Average, USA:

- ○

- Lower PFAS concentrations reflect areas without direct contamination sources. Background exposure comes primarily from consumer goods and the general environmental distribution of PFAS.

-

Greek Avg. (ΕOPΥΥ):

- ○

- Although PFOS levels in Greek populations align with hotspots like Parkersburg, no substantial data is available for PFOA or PFHxS. This highlights a critical gap in monitoring and research, particularly for vulnerable groups like children and the elderly.

- Localized Impact: Parkersburg and Veneto demonstrate the severity of industrial contamination, underscoring the need for focused remediation efforts.

- Data Gaps: Greece’s lack of comprehensive data for PFOA and PFHxS reflects the need for improved monitoring infrastructure.

- Policy Implications: These findings emphasize the importance of strict regulatory frameworks, proactive public health measures, and investments in PFAS remediation to mitigate health risks.

-

It specifies that the data represents populations within Greece:

- ○

- Children (0-12): 12 ng/mL

- ○

- Adolescents (13-18): 10 ng/mL

- ○

- Adults (19-64): 8 ng/mL

- ○

- Elderly (65+): 6 ng/mL

-

Greek Data (ΕOΠΥΥ Analysis):

- ○

- Children (0-12): 12 ng/mL

- ○

- Adolescents (13-18): 10 ng/mL

- ○

- Adults (19-64): 8 ng/mL

- ○

- Elderly (65+): 6 ng/mL

-

EU Average:

- ○

- Children (0-12): 10 ng/mL

- ○

- Adolescents (13-18): 8 ng/mL

- ○

- Adults (19-64): 7 ng/mL

- ○

- Elderly (65+): 5 ng/mL

-

High PFAS Exposure:

- ○

- Elevated Cholesterol: 25%

- ○

- Thyroid Disease: 10%

- ○

- Kidney Cancer: 2%

- ○

- Testicular Cancer: 1.5%

-

Low PFAS Exposure:

- ○

- Elevated Cholesterol: 15%

- ○

- Thyroid Disease: 5%

- ○

- Kidney Cancer: 1%

- ○

- Testicular Cancer: 0.5%

- Parkersburg, USA: 12 ng/mL

- Veneto, Italy: 10 ng/mL

- National Average, USA: 4 ng/mL

- Greece: 12 ng/mL

- Parkersburg, USA: 8 ng/mL

- Veneto, Italy: 7 ng/mL

- National Average, USA: 2 ng/mL

- Greece: No reported data

- Parkersburg, USA: 6 ng/mL

- Veneto, Italy: 5 ng/mL

- National Average, USA: 1 ng/mL

- Greece: No reported data

-

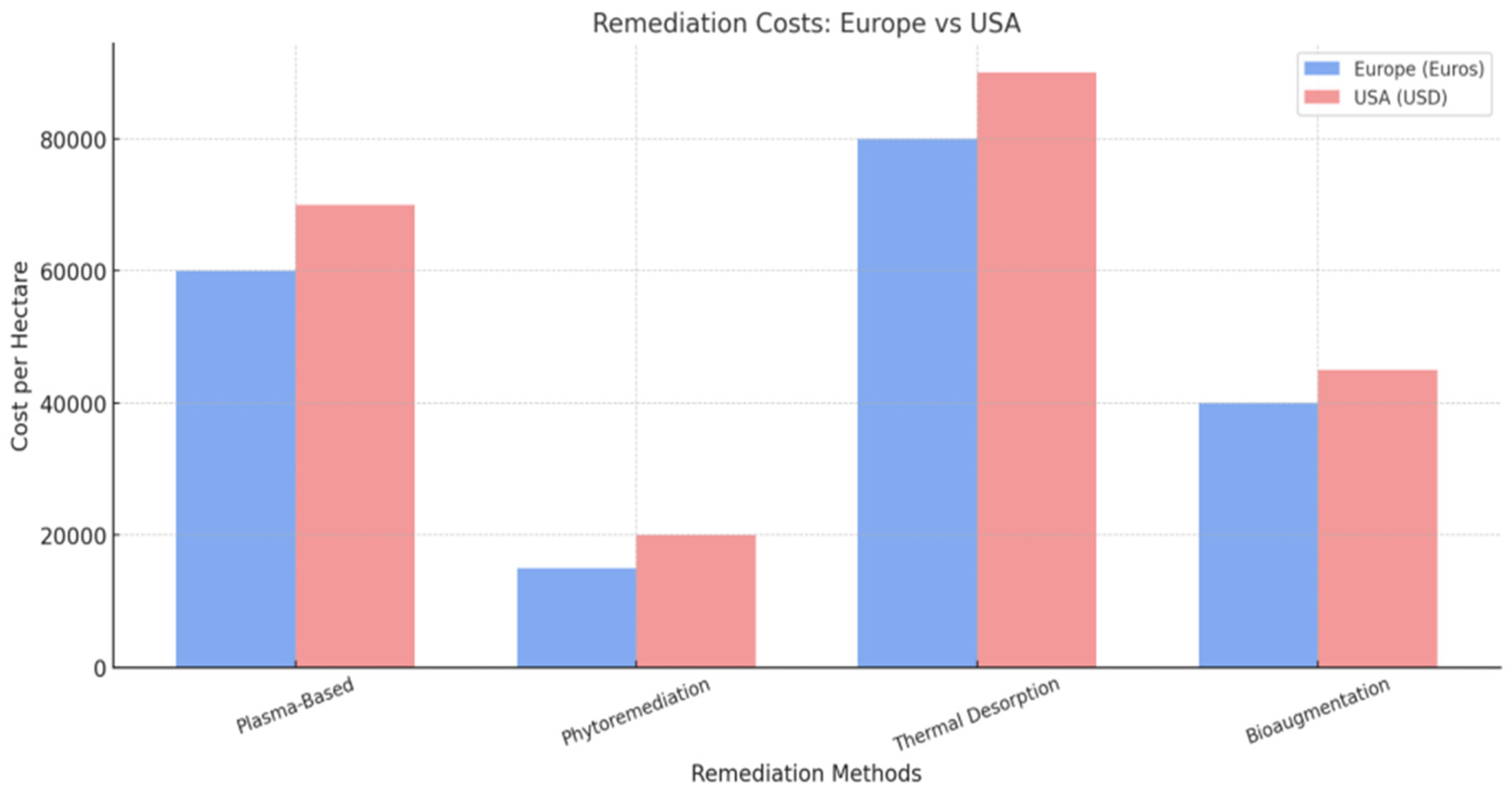

Europe (in Euros):

- ○

- Plasma-Based: €60,000 per hectare

- ○

- Phytoremediation: €15,000 per hectare

- ○

- Thermal Desorption: €80,000 per hectare

- ○

- Bioaugmentation: €40,000 per hectare

-

USA (in USD):

- ○

- Plasma-Based: $70,000 per hectare

- ○

- Phytoremediation: $20,000 per hectare

- ○

- Thermal Desorption: $90,000 per hectare

- ○

- Bioaugmentation: $45,000 per hectare

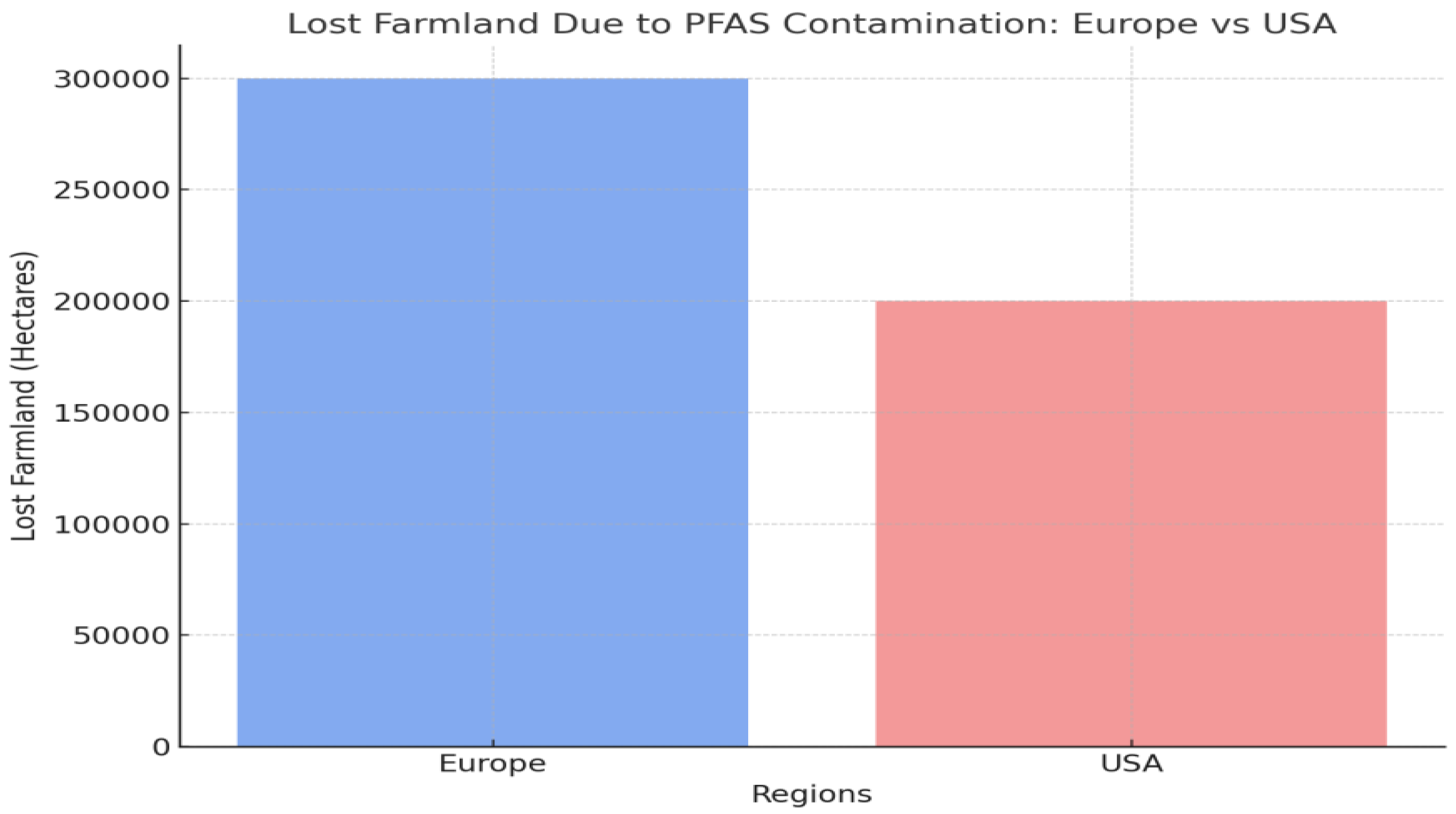

- Europe: Approximately 300,000 hectares of farmland were lost to PFAS contamination.

- USA: Approximately 200,000 hectares of farmland were lost to PFAS contamination.

-

Europe:

- ○

- Starting at 300,000 hectares, increasing to 550,000 hectares over 25 years.

-

USA:

- ○

- Starting at 200,000 hectares, increasing to 400,000 hectares over 25 years.

-

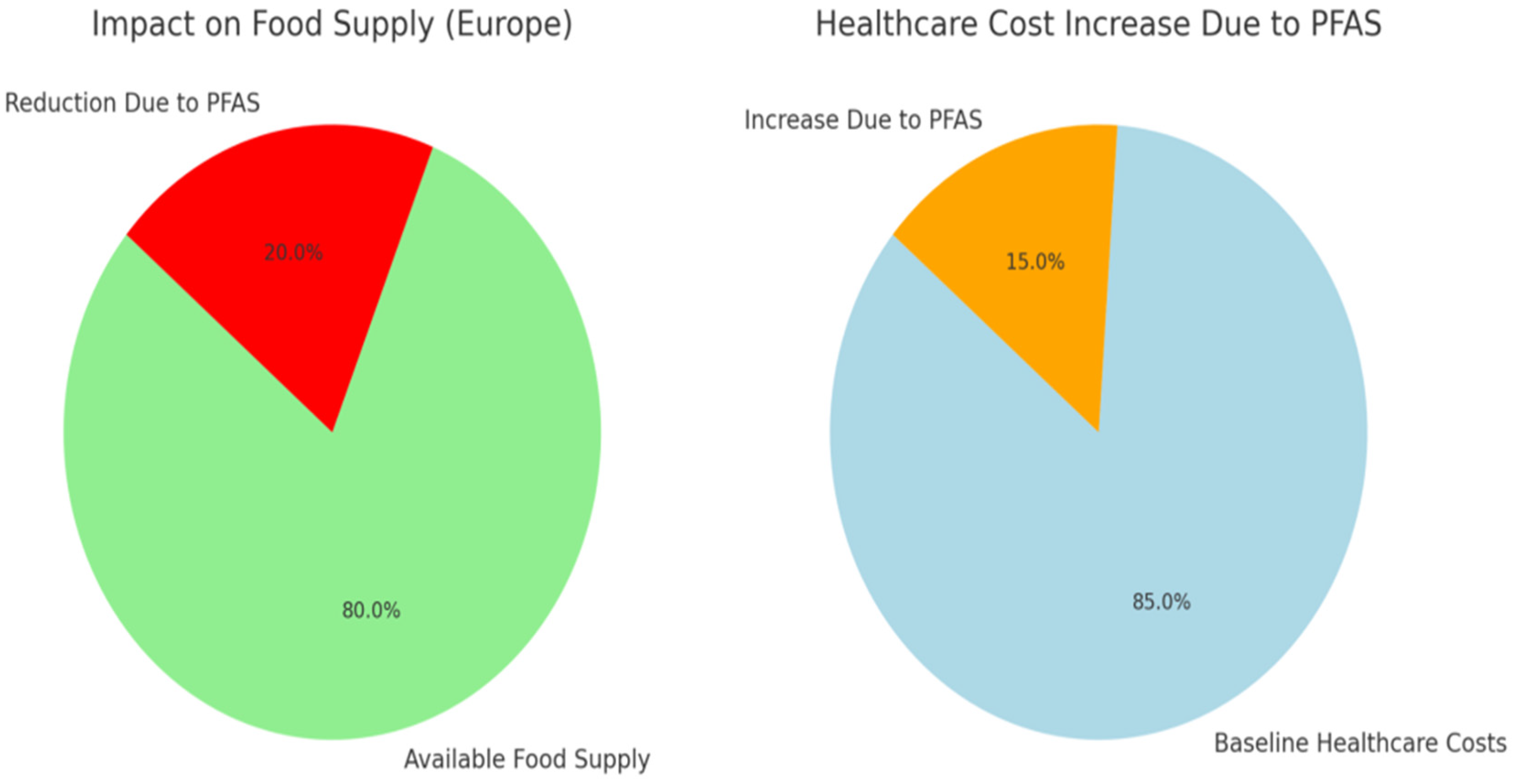

Impact on Food Supply (Europe):

- ○

- 80% of the food supply remains available.

- ○

- 20% is lost due to farmland contamination over 25 years.

-

Healthcare Cost Increase Due to PFAS:

- ○

- 85% represents baseline healthcare costs.

- ○

- 15% is attributed to the increase in costs due to PFAS-related health conditions.

- Data Collection: Sensors collect data on soil and water PFAS concentrations, geophysical characteristics, and hydrology.

- Data Integration: AI systems integrate datasets from various sources (e.g., remote sensing, ground-based sensors).

- Hotspot Prediction: Machine learning algorithms predict contamination patterns and potential hotspots by analyzing spatial correlations and trends.

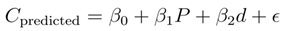

- Regression Models: Predict PFAS concentrations based on input variables such as soil permeability (PP) and distance to contamination source (d):where:

- ○

- Cpredicted: Predicted PFAS concentration,

- ○

- β0, β1, β2: Regression coefficients,

- ○

: Error term.

: Error term.

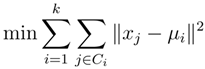

- Spatial Clustering (K-Means): Identify clusters of high PFAS concentrations:where:

- ○

- k: Number of clusters,

- ○

- Ci: Data points in cluster i,

- ○

- Xj: Position of data point j,

- ○

- μi: Centroid of cluster ii.

- Field-Level Analysis: AI tools map PFAS concentrations on farms, enabling targeted remediation.

- Policy Development: Governments use these maps to prioritize regions for intervention.

-

Engineering Microorganisms:

- ○

- Genes responsible for producing fluorescent proteins (e.g., green fluorescent protein, GFP) are inserted into microbes.

- ○

- These genes are activated in the presence of PFAS, leading to a detectable fluorescence.

-

Detection Process:

- ○

- Microbes are introduced into soil or water samples.

- ○

- Fluorescence intensity correlates with PFAS concentration.

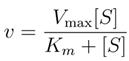

- v: Fluorescence intensity,

- Vmax: Maximum fluorescence response,

- Km: PFAS concentration at half-maximal fluorescence,

- [S]: PFAS concentration in the sample.

- Signal Processing: Use Fourier transforms to eliminate noise from fluorescence measurements.

- Concentration Estimation: Apply regression models to correlate fluorescence intensity with PFAS concentration.

- Nanofiltration membranes use pore sizes between 0.001 and 0.01 microns to block PFAS, particularly long-chain molecules.

- Reverse osmosis is often employed in conjunction with nanofiltration for enhanced PFAS removal.

- High efficiency, with removal rates exceeding 99% for long-chain PFAS.

- Versatility in treating both water and leachate.

- Disposal of concentrated PFAS-laden brine remains an issue but can be remediated.

- Membrane fouling can reduce efficiency over time (Rahman et al., 2014).

- Mineral Addition: Supplement the soil with essential minerals like calcium, magnesium, and phosphorus to correct deficiencies caused by PFAS removal processes.

- Organic Amendments: Incorporate compost, biochar, or humic substances to improve soil organic matter and microbial activity.

- Enhances water retention and aeration.

- Promotes healthy root growth and plant productivity.

- Selection of Microbes: Use a combination of native bacteria and fungi adapted to the local environment.

- Delivery Systems: Spray or inject microbial solutions into the soil to ensure even distribution.

- Monitoring: Assess microbial activity and diversity using soil DNA sequencing and metabolic profiling.

- Promotes nutrient cycling and organic matter decomposition.

- Reduces soil compaction and improves plant-microbe interactions.

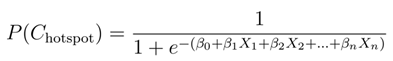

- P(Chotspot): Probability of a contamination hotspot.

- X1, X2, …, Xn: Predictor variables (e.g., soil PFAS levels, pH, rainfall).

- β1, β2, …, βn: Regression coefficients.

3.2. Findings the Challenges and Opportunities in PFAS Remediation

High Costs of Advanced Remediation Technologies

Knowledge Gaps in PFAS Degradation Pathways and Long-Term Impacts

Global

The United States

Europe

Greece and Mediterranean Countries

Opportunities in PFAS Remediation

Leveraging EU Green Deal Initiatives

Collaboration Between Stakeholders

- Facilitate knowledge sharing and reduce technological barriers.

- Enable large-scale deployment of innovative solutions, such as plasma-based systems or hybrid remediation methods.

4. Discussion

Recommendations

Future Directions

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Adamopoulos, I. P., Frantzana, A. A., & Syrou, N. F. (2023b). Epidemiological surveillance and environmental hygiene, SARS-CoV-2 infection in the community, urban wastewater control in Cyprus, and water reuse. Journal of Contemporary Studies in Epidemiology and Public Health, 4(1), ep23003. [CrossRef]

- Adamopoulos, I. P., Lamnisos, D., Syrou, N. F., & Boustras, G. (2022). Public health and work safety pilot study: Inspection of job risks, burn out syndrome and job satisfaction of public health inspectors in Greece. Safety Science, 147, Article 105592. [CrossRef]

- Adamopoulos, I. P., Syrou, N. F., & Adamopoulou, J. P. (2024a). Greece’s current water and wastewater regulations and the risks they pose to environmental hygiene and public health, as recommended by the European Union Commission. European Journal of Sustainable Development Research, 8(2), em0251. [CrossRef]

- Adamopoulos, I., & Syrou, N. (2023a). Occupational Hazards Associated with the Quality and Training Needs of Public Health Inspectors in Greece. Medical Sciences Forum, 19(1), 2. [CrossRef]

- Adamopoulos, I., Frantzana, A., & Syrou, N. (2024b). Climate Crises Associated with Epidemiological, Environmental, and Ecosystem Effects of a Storm: Flooding, Landslides, and Damage to Urban and Rural Areas (Extreme Weather Events of Storm Daniel in Thessaly, Greece). Medical Sciences Forum, 25(1), 7. [CrossRef]

- Adamopoulos, I., Frantzana, A., Adamopoulou, J., & Syrou, N. (2023c). Climate Change and Adverse Public Health Impacts on Human Health and Water Resources. Environmental Sciences Proceedings, 26(1), 178. [CrossRef]

- Adamopoulou, J. P., Frantzana, A. A., & Adamopoulos, I. P. (2023d). Addressing water resource management challenges in the context of climate change and human influence. European Journal of Sustainable Development Research, 7(3), em0223. [CrossRef]

- Agency for Toxic Substances and Disease Registry (ATSDR). (2020). PFAS Exposure Assessments Final Report. Accessed [21-1-2025] Source: https://www.atsdr.cdc.gov/pfas.

- Ahrens, L., & Bundschuh, M. (2014). Fate and effects of poly- and perfluoroalkyl substances in the aquatic environment: A review. Environmental Toxicology and Chemistry, 33(9), 1921–1929. [CrossRef]

- Bibri, S. E., Krogstie, J., Kaboli, A., & Alahi, A. (2024). Smarter eco-cities and their leading-edge artificial intelligence of things solutions for environmental sustainability: A comprehensive systematic review. Environmental Science and Ecotechnology, 19, 100330. [CrossRef]

- Bolan, N., Sarkar, B., Yan, Y., Li, Q., Wijesekara, H., Kannan, K., ... & Rinklebe, J. (2021). Remediation of poly-and perfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS) contaminated soils–to mobilize or to immobilize or to degrade?. Journal of Hazardous Materials, 401, 123892. [CrossRef]

- Breitmeyer, S. E., Williams, A. M., Conlon, M. D., Wertz, T. A., Heflin, B. C., Shull, D. R., & Duris, J. W. (2024). Predicted Potential for Aquatic Exposure Effects of Per-and Polyfluorinated Alkyl Substances (PFAS) in Pennsylvania’s Statewide Network of Streams. Toxics, 12(12), 921. [CrossRef]

- C8 Health Project. (2013). Community exposure studies in Parkersburg, West Virginia. Accessed [27-1-2025] https://www.c8sciencepanel.org.

- Chen, L., Chen, Z., Zhang, Y., Liu, Y., Osman, A. I., Farghali, M., ... & Yap, P. S. (2023). Artificial intelligence-based solutions for climate change: a review. Environmental Chemistry Letters, 21(5), 2525-2557. [CrossRef]

- Cousins, I. T., et al. (2016). The concept of essential use for determining when uses of PFASs can be phased out. Environmental Science: Processes & Impacts, 21(11), 1803–1815. [CrossRef]

- Dauvergne, P. (2022). Is artificial intelligence greening global supply chains? Exposing the political economy of environmental costs. Review of International Political Economy. [CrossRef]

- Di Nisio, A., Pannella, M., Vogiatzis, S., Sut, S., Dall’Acqua, S., Santa Rocca, M., ... & Foresta, C. (2022). Impairment of human dopaminergic neurons at different developmental stages by perfluoro-octanoic acid (PFOA) and differential human brain areas accumulation of perfluoroalkyl chemicals. Environment International, 158, 106982. [CrossRef]

- Ditria, E. M., Buelow, C. A., Gonzalez-Rivero, M., & Connolly, R. M. (2022). Artificial intelligence and automated monitoring for assisting conservation of marine ecosystems: A perspective. Frontiers in Marine Science, 9, 918104. [CrossRef]

- Draghi, S., Curone, G., Risoluti, R., Materazzi, S., Gullifa, G., Amoresano, A., ... & Arioli, F. (2024). Comparative analysis of PFASs concentrations in fur, muscle, and liver of wild roe deer as biomonitoring matrices. Frontiers in Veterinary Science, 11, 1500651. [CrossRef]

- EPA PFAS Roadmap. (2021). Environmental Protection Agency’s strategic plan for addressing PFAS. Accessed [23-1-2025] https://www.epa.gov/pfas.

- European Chemicals Agency (ECHA). (2020). Annex XV restriction report: Proposal for a restriction on per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS). Accessed [2-1-2025] https://echa.europa.eu/.

- European Commission. (2020). Chemicals strategy for sustainability. https://ec.europa.eu/.

- European Food Safety Authority (EFSA). (2020). Risk assessment of PFAS in the food chain. Accessed [1-2-2025] https://www.efsa.europa.eu.

- Falandysz, J., Liu, G., & Rutkowska, M. (2024). Analytical progress on emerging pollutants in the environment: An overview of the topics. TrAC Trends in Analytical Chemistry. [CrossRef]

- Feinstein, J., Sivaraman, G., Picel, K., Peters, B., Vázquez-Mayagoitia, Á., Ramanathan, A., MacDonell, M., Foster, I., & Yan, E. (2021). Uncertainty-informed deep transfer learning of perfluoroalkyl and polyfluoroalkyl substance toxicity. Journal of Chemical Information and Modeling, 61(12), 5793–5803. [CrossRef]

- Gerardu, T., Dijkstra, J., Beeltje, H., van Duivenbode, A. V. R., & Griffioen, J. (2023). Accumulation and transport of atmospherically deposited PFOA and PFOS in undisturbed soils downwind from a fluoropolymers factory. Environmental Advances, 11, 100332. [CrossRef]

- Ghisi, R., Vamerali, T., & Manzetti, S. (2019). Accumulation of perfluorinated alkyl substances (PFAS) in agricultural plants: A review. Environmental Research, 169, 326–341. [CrossRef]

- Giesy, J. P., & Kannan, K. (2001). Global distribution of perfluorooctane sulfonate in wildlife. Environmental Science & Technology, 35(7), 1339–1342. [CrossRef]

- Gill, A. S. & Germann, S. (2022). Conceptual and normative approaches to AI governance for a global digital ecosystem supportive of the UN Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). AI and Ethics. [CrossRef]

- Göckener, B., et al. (2020). Transfer of per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS) from feed into milk: Approaching a worst-case scenario. Chemosphere, 249, 126111. [CrossRef]

- Goldenman, G., et al. (2019). The cost of inaction: A socioeconomic analysis of environmental and health impacts linked to exposure to PFAS. Nordic Council of Ministers. [CrossRef]

- Han, B. C., Liu, J. S., Bizimana, A., Zhang, B. X., Kateryna, S., Zhao, Z., ... & Meng, X. Z. (2023). Identifying priority PBT-like compounds from emerging PFAS by nontargeted analysis and machine learning models. Environmental Pollution, 122663. [CrossRef]

- Hu, X. C., Dai, M., Sun, J. M., & Sunderland, E. M. (2023). The utility of machine learning models for predicting chemical contaminants in drinking water: Promise, challenges, and opportunities. Current Environmental Health Reports, 10(1), 45–60. [CrossRef]

- Iulini, M., Russo, G., Crispino, E., Paini, A., Fragki, S., Corsini, E., & Pappalardo, F. (2024). Advancing PFAS risk assessment: Integrative approaches using agent-based modelling and physiologically-based kinetic for environmental and health safety. Computational and Structural Biotechnology Journal, 23, 2763-2778. [CrossRef]

- Jeong, N., Park, S., Mahajan, S., Zhou, J., Blotevogel, J., Li, Y., ... & Chen, Y. (2024). Elucidating governing factors of PFAS removal by polyamide membranes using machine learning and molecular simulations. Nature Communications, 15(1), 10918. [CrossRef]

- Karbassiyazdi, E., Fattahi, F., Yousefi, N., Tahmassebi, A., Taromi, A. A., Manzari, J. Z., ... & Razmjou, A. (2022). XGBoost model as an efficient machine learning approach for PFAS removal: Effects of material characteristics and operation conditions. Environmental Research, 215, 114286. [CrossRef]

- Kibbey, T. C. G., Jabrzemski, R., & O’Carroll, D. M. (2021). Predicting the relationship between PFAS component signatures in water and non-water phases through mathematical transformation: Application to machine learning. Chemosphere, 272, 129870. [CrossRef]

- Kotthoff, M., Müller, J., Jürling, H., Schlummer, M., & Fiedler, D. (2015). Perfluoroalkyl and polyfluoroalkyl substances in consumer products. Environmental Science and Pollution Research, 22(19), 14546–14559. [CrossRef]

- Koulini, G. V., Vinayagam, V., Nambi, I. M., & Krishna, R. R. (2024). Per-and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS) in Indian environment: Prevalence, impacts and solutions. Journal of Water Process Engineering, 66, 105988. [CrossRef]

- Lazova-Borisova, İ., & Adamopoulos, I. (2024). COMPLIANCE OF CARMINIC ACID APPLICATION WITH EUROPEAN LEGISLATION FOR FOOD SAFETY AND PUBLIC HEALTH. [CrossRef]

- Lei, L., Pang, R., Han, Z., Wu, D., Xie, B., & Su, Y. (2023). Current applications and future impact of machine learning in emerging contaminants: A review. Critical Reviews in Environmental Science and Technology, 53(20), 1817-1835. [CrossRef]

- Li, R. & MacDonald Gibson, J. (2022). Predicting the occurrence of short-chain PFAS in groundwater using machine-learned Bayesian networks. Frontiers in Environmental Science. [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y., D’Agostino, L. A., Qu, G., Jiang, G., & Martin, J. W. (2019). High-resolution mass spectrometry (HRMS) methods for nontarget discovery and characterization of poly- and perfluoroalkyl substances (PFASs) in environmental and human samples. Trends in Analytical Chemistry, 121, 115420. [CrossRef]

- Machine learning Helps in Quickly Diagnosis Cases of “New Corona” (M. M. Mijwil, I. Adamopoulos, & P. Pudasaini , Trans.). (2024). Mesopotamian Journal of Artificial Intelligence in Healthcare, 2024, 16-19. [CrossRef]

- Navidpour, A. H., Hosseinzadeh, A., Huang, Z., Li, D., & Zhou, J. L. (2024). Application of machine learning algorithms in predicting the photocatalytic degradation of perfluorooctanoic acid. Catalysis Reviews, 66(2), 687-712. [CrossRef]

- OECD. (2021). OECD principles on per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS): Towards a framework for global action. Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development. Accessed [21-12-2024] Retrieved from https://www.oecd.org/.

- Peritore, A. F., Gugliandolo, E., Cuzzocrea, S., Crupi, R., & Britti, D. (2023). Current review of increasing animal health threat of per-and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS): Harms, limitations, and alternatives to manage their toxicity. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 24(14), 11707. [CrossRef]

- Prasad, M. N. V. & Elchuri, S. V. (2023). Environmental contaminants of emerging concern: occurrence and remediation. Chemistry-Didactics-Ecology-Metrology. [CrossRef]

- Rahman, M. F., Peldszus, S., & Anderson, W. B. (2014). Behaviour and fate of perfluoroalkyl and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFASs) in drinking water treatment: A review. Water Research, 50, 318–340. [CrossRef]

- Ross, I., et al. (2018). A review of emerging technologies for remediation of PFASs. Remediation Journal, 28(2), 101–126. [CrossRef]

- Said, T. O., & El Zokm, G. M. (2024). Fate, Bioaccumulation, Remediation, and Prevention of POPs in Aquatic Systems Regarding Future Orientation. In Persistent Organic Pollutants in Aquatic Systems: Classification, Toxicity, Remediation and Future (pp. 115-148). Cham: Springer Nature Switzerland. [CrossRef]

- Scheringer, M., et al. (2014). Helsingør statement on poly- and perfluorinated alkyl substances (PFASs). Chemosphere, 114, 337–339. [CrossRef]

- Shivaprakash, K. N., Swami, N., Mysorekar, S., Arora, R., Gangadharan, A., Vohra, K., ... & Kiesecker, J. M. (2022). Potential for artificial intelligence (AI) and machine learning (ML) applications in biodiversity conservation, managing forests, and related services in India. Sustainability, 14(12), 7154. [CrossRef]

- Sivagami, K., Sharma, P., Karim, A. V., Mohanakrishna, G., Karthika, S., Divyapriya, G., ... & Kumar, A. N. (2023). Electrochemical-based approaches for the treatment of forever chemicals: removal of perfluoroalkyl and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS) from wastewater. Science of the Total Environment, 861, 160440. [CrossRef]

- Stahl, B. C. (2021). Artificial intelligence for a better future: an ecosystem perspective on the ethics of AI and emerging digital technologies. [CrossRef]

- Stensson, N., Lignell, S., Freeman, D., Jordan, F., Helmfrid, I., Karlsson, H., & Ljunggren, S. (2023). PFAS and Lipoproteomics in Swedish Adolescents. SSRN. [CrossRef]

- Su, A., Cheng, Y., Zhang, C., Yang, Y. F., She, Y. B., & Rajan, K. (2024). An artificial intelligence platform for automated PFAS subgroup classification: A discovery tool for PFAS screening. Science of The Total Environment, 921, 171229. [CrossRef]

- Tao, L., Tang, W., Xia, Z., Wu, B., Liu, H., Fu, J., ... & Huang, Y. (2024). Machine learning predicts the serum PFOA and PFOS levels in pregnant women: Enhancement of fatty acid status on model performance. Environment International, 108837. [CrossRef]

- Tatarinov, K., Ambos, T. C., & Tschang, F. T. (2022). Scaling digital solutions for wicked problems: Ecosystem versatility. Journal of International Business Studies, 54(4), 631. [CrossRef]

- Tokranov, A. K., Ransom, K. M., Bexfield, L. M., Lindsey, B. D., Watson, E., Dupuy, D. I., ... & Bradley, P. M. (2024). Predictions of groundwater PFAS occurrence at drinking water supply depths in the United States. Science, 386(6723), 748-755. [CrossRef]

- Valamontes, A. (2024). Accessible research papers for individuals with dyslexia and autism spectrum disorders. [CrossRef]

- Vierke, L., et al. (2012). Perfluorooctanoic acid (PFOA)—A new kid on the block in the EU legislation for chemicals. Environmental Sciences Europe, 24(1), 1–11. [CrossRef]

- Winchell, L. J., Ross, J. J., Wells, M. J., Fonoll, X., Norton Jr, J. W., & Bell, K. Y. (2021). Per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances thermal destruction at water resource recovery facilities: A state of the science review. Water Environment Research, 93(6), 826-843. [CrossRef]

- Winchell, L. J., Wells, M. J., Ross, J. J., Fonoll, X., Norton Jr, J. W., Kuplicki, S., ... & Bell, K. Y. (2022). Per-and polyfluoroalkyl substances presence, pathways, and cycling through drinking water and wastewater treatment. Journal of Environmental Engineering, 148(1), 03121003. [CrossRef]

- Yigitcanlar, T., Mehmood, R., & Corchado, J. M. (2021). Green artificial intelligence: Towards an efficient, sustainable and equitable technology for smart cities and futures. Sustainability. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, K. & Zhang, H. (2022). Machine learning modeling of environmentally relevant chemical reactions for organic compounds. ACS ES&T Water, 2(5), 745-754. [CrossRef]

- Zhao, L., et al. (2018). Adsorption of perfluoroalkyl substances (PFASs) in water by carbonaceous adsorbents: A review. Critical Reviews in Environmental Science and Technology, 48(11), 1042–1083. [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).