Submitted:

04 July 2025

Posted:

04 July 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Bacterial and Cell Culture

2.2. Molecular Cloning of vapD and Chloramphenicol Resistance Cassette

2.2.1. Molecular Cloning of vapD (HP0315) Gene

2.2.2. Molecular Cloning of Chloramphenicol Resistance Cassette (Cmr)

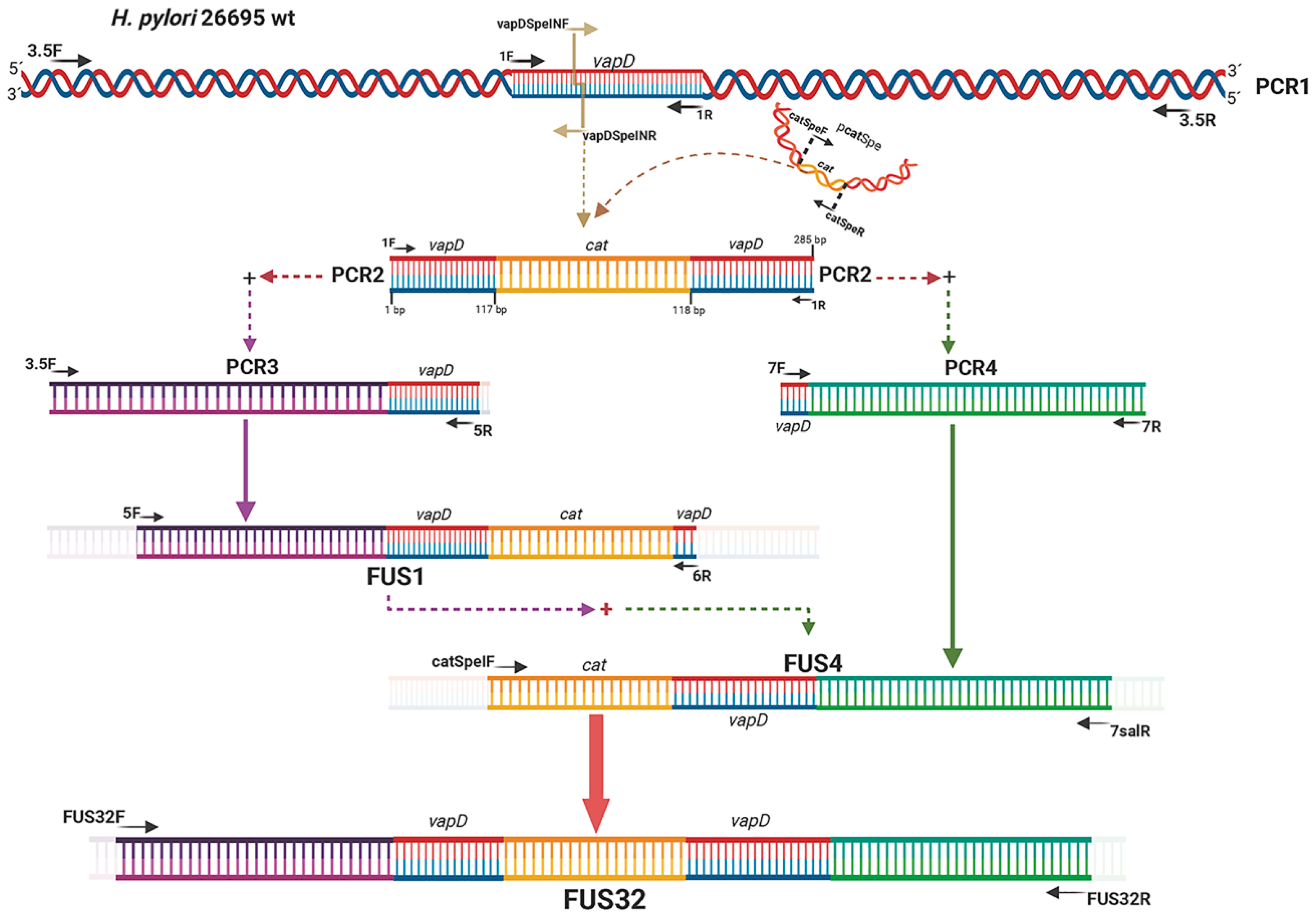

2.3. Construction of vapD (HP0315) Knockout Mutant

2.3.1. Site Directed Mutagenesis in vapD Gene

2.3.2. Introduction of Homologous Flanking Regions by Overlap Extension PCR

2.4. Electrotransformation and Homologous Recombination

2.4.1. Preparation of Recipient H. pylori Cells

2.4.2. Transformation and recombination

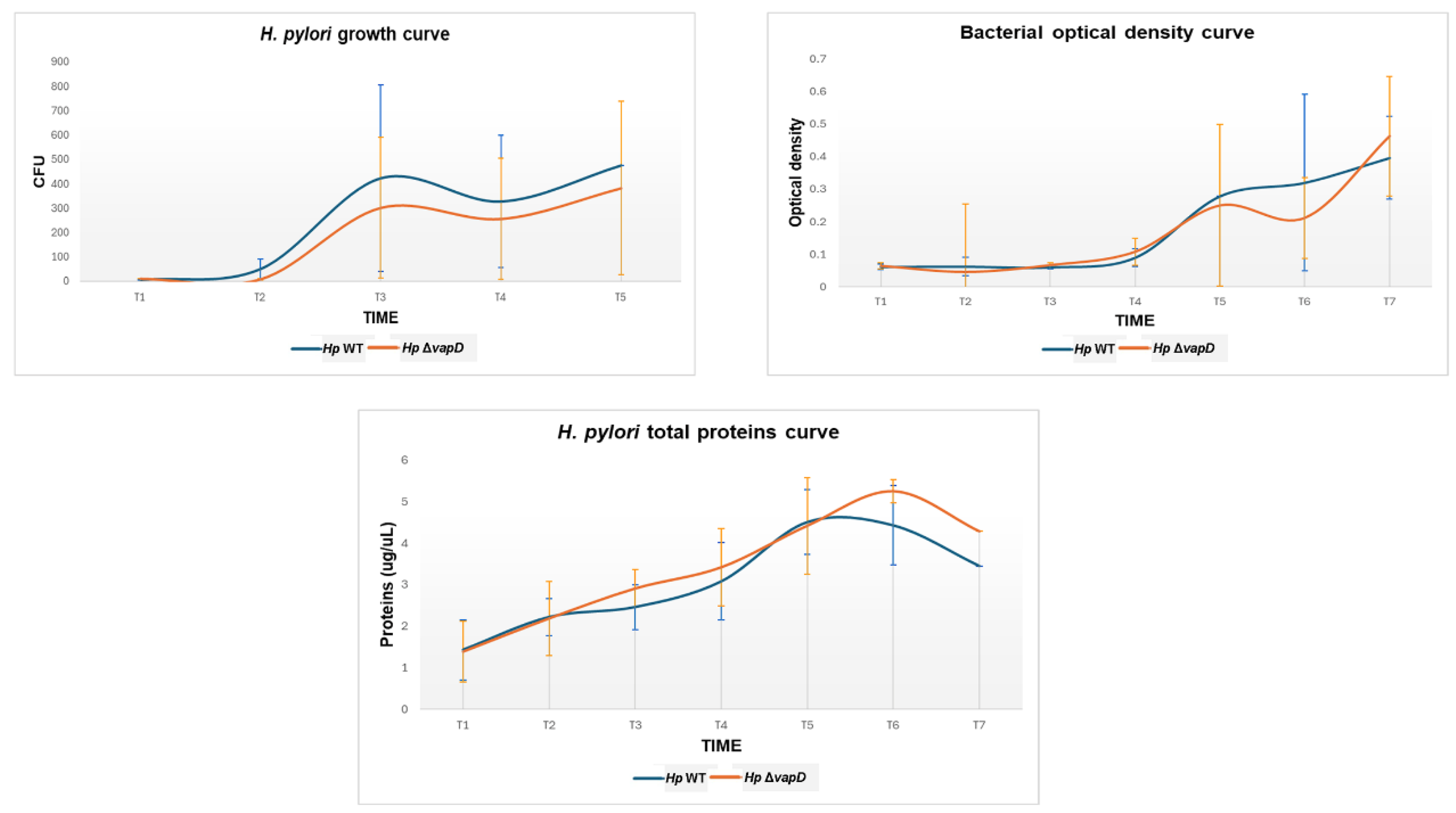

2.5. Bacterial Growth Curves Comparison

2.5.1. Bacterial Culture and Inoculation of Growth Curve

2.5.2. Total Protein Extraction

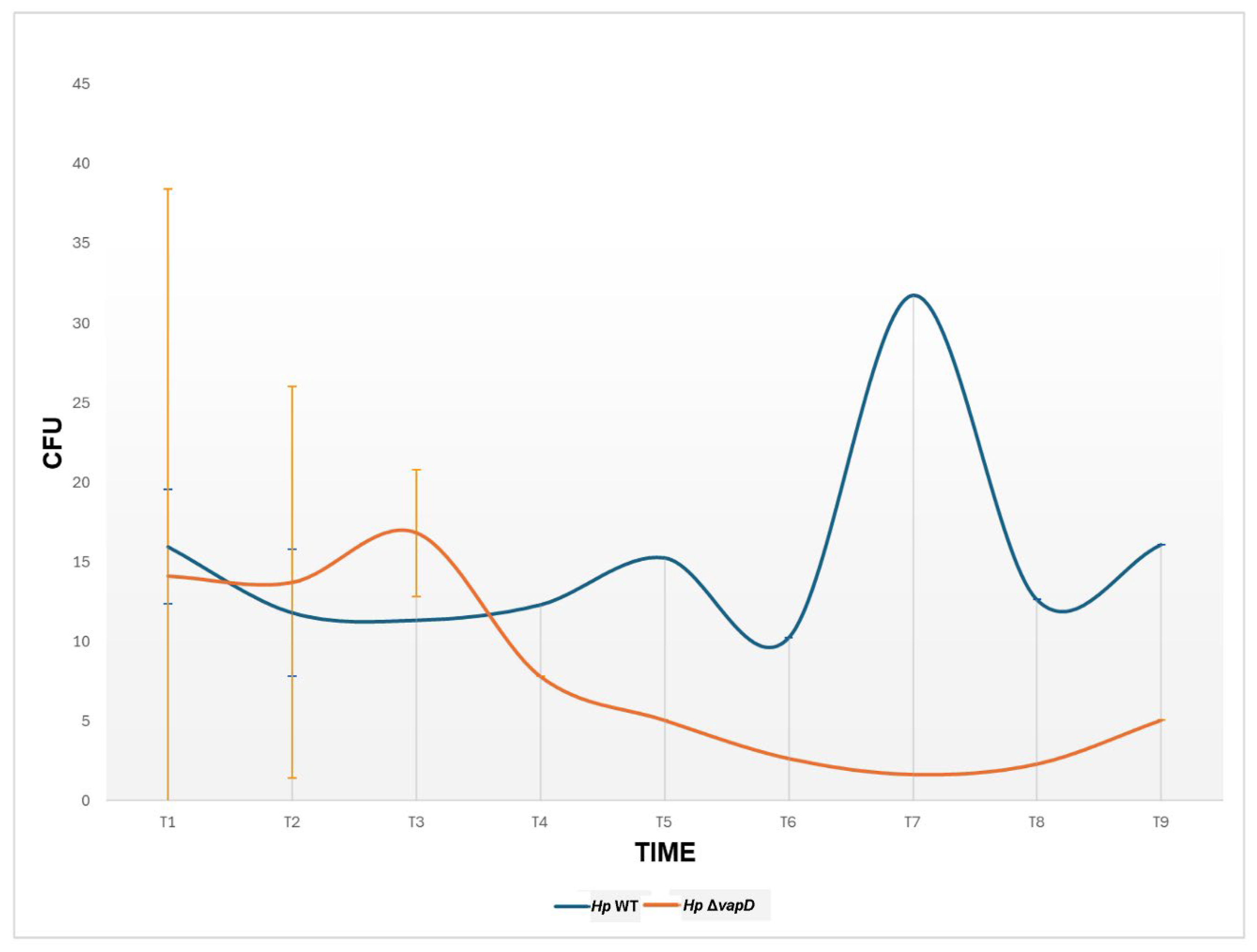

2.6. H. pylori 26695 wt-AGS Cells and H. pylori 26695 ΔvapD-AGS Cells Co-Cultures

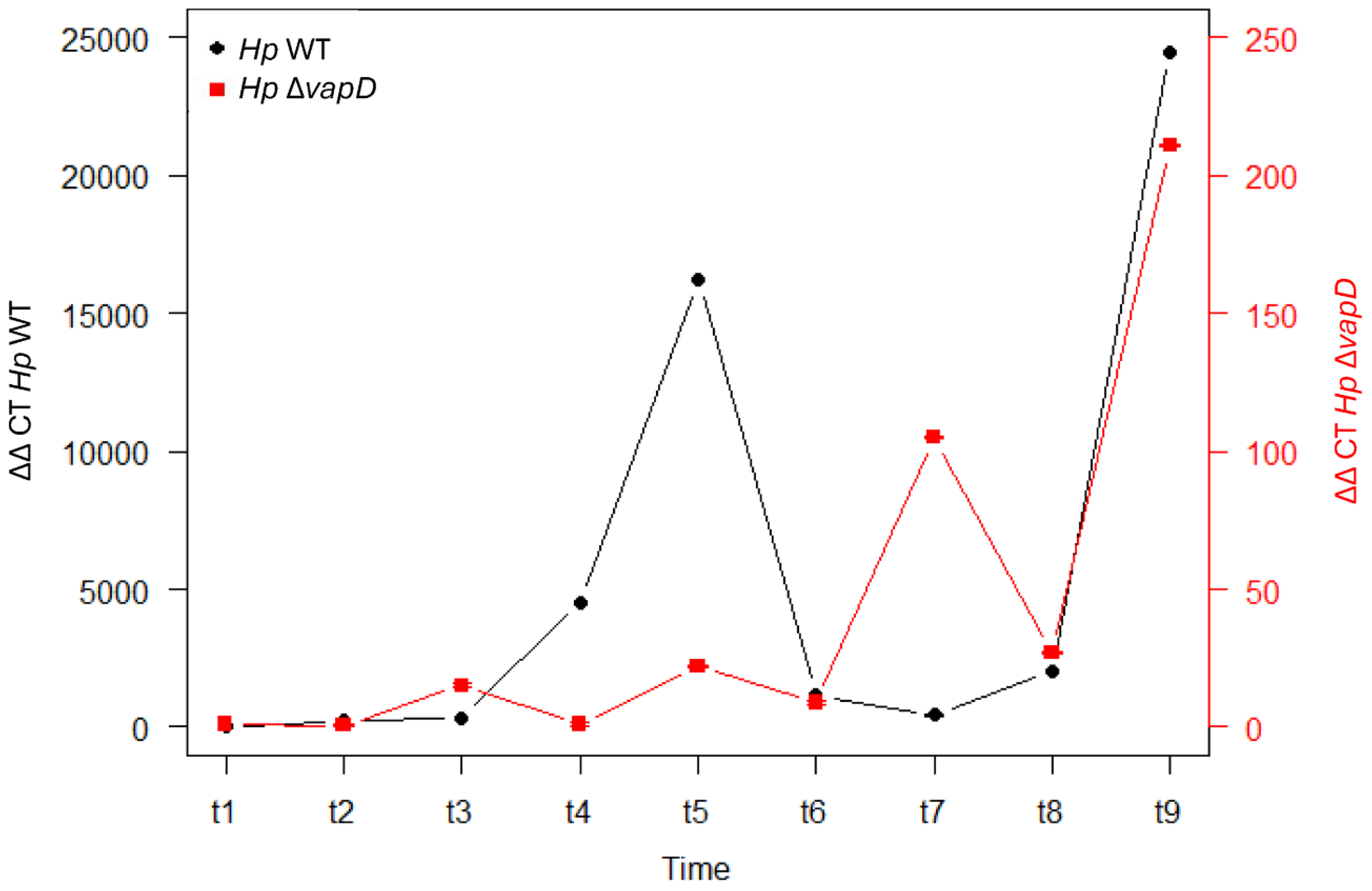

2.6.1. Total RNA Extraction and Detection of vacA, vapD, ureA, 16s Hp and GAPDH Genes’ Transcription Levels by qRT-PCR from Intracellular H. pylori 26695 wt-AGS Cells and H. pylori 26695 ΔvapD-AGS Cells

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Funding

Acknowledgments

References

- Falush, D.; Wirth, T.; Linz, B.; Pritchard, J.K.; Stephens, M.; Kidd, M.; Blaser, M.J.; Graham, D.Y.; Vacher, S.; Perez-Perez, G.I.; et al. Traces of Human Migrations in Helicobacter pylori Populations. Science. 2003, 299, 1582–1585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagasawa, S.; Motani-Saitoh, H.; Inoue, H.; Iwase, H. Geographic Diversity of Helicobacter pylori in Cadavers: Forensic Estimation of Geographical Origin. Forensic Sci. Int. 2013, 229, 7–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kersulyte, D.; Mukhopadhyay, A.K.; Velapatiño, B.; Su, W.; Pan, Z.; Garcia, C.; Hernandez, V.; Valdez, Y.; Mistry, R.S.; Gilman, R.H.; et al. Differences in Genotypes of Helicobacter pylori from Different Human Populations. J. Bacteriol. 2000, 182, 3210–3218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, W.L.; Yeh, Y.C.; Sheu, B.S. The Impacts of H. pylori Virulence Factors on the Development of Gastroduodenal Diseases. J. Biomed. Sci. 2018, 25, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blaser, M.J.; Atherton, J.C. Helicobacter pylori Persistence: Biology and Disease. J. Clin. Invest. 2004, 113, 321–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allen, L.A.H. Phagocytosis and Persistence of Helicobacter pylori. Cell. Microbiol. 2007, 9, 817–828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morales-Espinosa, R.; Delgado, G.; Serrano, L.R.; Castillo, E.; Santiago, C.A.; Hernández-Castro, R.; Gonzalez-Pedraza, A.; Mendez, J.L.; Mundo-Gallardo, L.F.; Manzo-Merino, J.; et al. High Expression of Helicobacter pylori VapD in Both the Intracellular Environment and Biopsies from Gastric Patients with Severity. PLoS One 2020, 15, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwon, A.R.; Kim, J.H.; Park, S.J.; Lee, K.Y.; Min, Y.H.; Im, H.; Lee, I.; Lee, K.Y.; Lee, B.J. Structural and Biochemical Characterization of HP0315 from Helicobacter pylori as a VapD Protein with an Endoribonuclease Activity. Nucleic Acids Res. 2012, 40, 4216–4228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benoit, S.; Benachour, A.; Taouji, S.; Auffray, Y.; Hartke, A. Induction of vap Genes Encoded by the Virulence Plasmid of Rhodococcus equi during Acid Tolerance Response. Res. Microbiol. 2001, 152, 439–449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benoit, S.; Benachour, A.; Taouji, S.; Auffray, Y.; Hartke, A. H(2)O(2), Which Causes Macrophage-Related Stress, Triggers Induction of Expression of Virulence-Associated Plasmid Determinants in Rhodococcus equi. Infect. Immun. 2002, 70, 3768–3776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, D.; Walker, A.N.; Daines, D.A. Toxin-Antitoxin Loci vapBC-1 and vapXD Contribute to Survival and Virulence in Nontypeable Haemophilus influenzae. BMC Microbiol. 2012, 12, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katz, M.E.; Strugnell, R.A.; Rood, J.I. Molecular Characterization of a Genomic Region Associated with Virulence in Dichelobacter nodosus. Infect. Immun. 1992, 60, 4586–4592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weng, S.C.; Lin, W.H.; Chang, Y.F.; Chang, C.F. Identification of a Virulence-Associated Protein Homolog Gene and ISRa1 in a Plasmid of Riemerella anatipestifer. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 1999, 179, 11–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, P.; Cover, T.L. High-Level Genetic Diversity in the VapD Chromosomal Region of Helicobacter pylori. J. Bacteriol. 1997, 179, 2852–2856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Livak, K.J.; Schmittgen, T.D. Analysis of Relative Gene Expression Data Using Real-Time Quantitative PCR and the 2(-Delta Delta C(T)) Method. Methods 2001, 25, 402–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morales-Espinosa, R.; González-Valencia, G.; Delgado, G.; Luis, J.; Torres, J.; Cravioto, A. Frequency and Characterization of vapD Gene in Helicobacter pylori Strains of Different vacA and cag-PAI Genotype. Bioquimia 2008, 33, 43–50. [Google Scholar]

- Delgado-Sapién, G.; Cerritos-Flores, R.; Flores-Alanis, A.; Méndez, J.L.; Cravioto, A.; Morales-Espinosa, R. Evolutionary Dynamics of vapD Gene in Helicobacter pylori and Its Wide Distribution among Bacterial Phyla. SOJ Microbiol Infect Dis 2020, 8, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flores-Alanis, A.; Delgado, G.; Santiago-Olivares, C.; Luna-Pineda, V.M.; Cruz-Rangel, A.; Guerrero-Mejia, D.; Escobar-Sanchez, M.L.; Torres-Ramirez, N.; Morales-Espinosa, R. Effective policlonal antibodies against the virulence-associated protein (VapD) of Helicobacter pylori, obtained drom recombinant VapD. PLoS ONE, 20, (4), e0321455. [CrossRef]

- Graham, J.E.; Peek, R.M.; Krishna, U.; Cover, T.L. Global Analysis of Helicobacter pylori Gene Expression in Human Gastric Mucosa. Gastroenterology 2002, 123, 1637–1648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Semino-Mora, C.; Doi, S.Q.; Marty, A.; Simko, V.; Carlstedt, I.; Dubois, A. Intracellular and Interstitial Expression of Helicobacter pylori Virulence Genes in Gastric Precancerous Intestinal Metaplasia and Adenocarcinoma. J. Infect. Dis. 2003, 187, 1165–1177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De la Cruz, M.A.; Ares, M.A.; Bargen, K. Von; Panunzi, L.G.; Martínez-Cruz, J.; Valdez-Salazar, H.A.; Jiménez-Galicia, C.; Torres, J. Gene Expression Profiling of Transcription Factors of Helicobacter pylori under Different Environmental Conditions. Front. Microbiol. 2017, 8, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Omotade Titilayo O; R, R. C. Manipulation of Host Cell Organelles by Intracellular Pathogens. Microbiol. Spectr. 2019, 7, 10.1128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faherty, C.S.; Maurelli, A.T. Staying Alive: Bacterial Inhibition of Apoptosis during Infection. Trends Microbiol. 2008, 16, 173–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhavsar, A.P.; Guttman, J.A.; Finlay, B.B. Manipulation of Host-Cell Pathways by Bacterial Pathogens. Nature 2007, 449, 827–834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dubois, A.; Borén, T. Helicobacter pylori Is Invasive and It May Be a Facultative Intracellular Organism. Cell. Microbiol. 2007, 9, 1108–1116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y.; Wang, Q.; Cheng, D.; Xu, W.; Lu, N. Adhesion and Invasion of Gastric Mucosa Epithelial Cells by Helicobacter pylori. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 2016, 6, 159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ko, G.H.; Kang, S.M.; Kim, Y.K.; Lee, J.H.; Park, C.K.; Youn, H.S.; Baik, S.C.; Cho, M.; Lee, W.K.; Rhee, K.H. Invasiveness of Helicobacter pylori into Human Gastric Mucosa. Helicobacter 1999, 4, 77–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwok, T.; Backert, S.; Schwarz, H.; Berger, J.; Meyer, T.F. Specific Entry of Helicobacter pylori into Cultured Gastric Epithelial Cells via a Zipper-like Mechanism. Infect. Immun. 2002, 70, 2108–2120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Terebiznik, M.R.; Vazquez, C.L.; Torbicki, K.; Banks, D.; Wang, T.; Hong, W.; Blanke, S.R.; Colombo, M.I.; Jones, N.L. Helicobacter pylori VacA Toxin Promotes Bacterial Intracellular Survival in Gastric Epithelial Cells. Infect. Immun. 2006, 74, 6599–6614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Primers | Forward | Reverse | MW | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 F/R | 5’ATGTATGCTTTAGCGTTTG 3’ | 5’GGATTTCACAATCTCAGTAA 3’ | 285 bp | Ping Cao |

| catSpeI F/R | 5’GTTGATCGACTAGTAAGAGGTTC 3’ | 5’GCCATTCAACTAGTTATTATCACT 3’ | 900 bp | This study |

| vapDSpeIN F/R | 5’TGACTAGTCTCAAGGGAG 3’ | 5’GAGACTAGTCAAACCCTAATAG 3’ | This study | |

| 3.5 F/R | 5’AAACGCGCAAAATCAAAACAACTT 3’ | 5’CGCGCAAGAAATGAGCAATAA 3’ | 3.5 Kb | This study |

| 5 F/R | 5’ATCGCTCACTTTGGCACTCA 3’ | 5’TAGGCTTTATTGTAGGGTTCTCCG 3’ | 1.9 Kb | This study |

| 6 F/R | 5’ACGCGCAAAATCAAAACAA 3’ | 5’TAAACGCTCTAATATCCCTAACAG 3’ | 3.2 Kb | This study |

| 7 F/R | 5’GACTTTAGCGATTTTACTGAGATT 3’ | 5’GCCATTTAGAGCGTGAA 3’ | 1.7 Kb | This study |

| 7 salR | 5’GGATTTTCGTCGACATCAAGGGTT 3’ | This study | ||

| PCR3 (3.5F/5R) | 5’AAACGCGCAAAATCAAAACAACTT 3’ | 5’TAGGCTTTATTGTAGGGTTCTCCG 3’ | 2.2 Kb | This study |

| PCR4 (7F/7R) | 5’GACTTTAGCGATTTTACTGAGATT 3’ | 5’GACTTTAGCGATTTTACTGAGATT 3’ | 1.7 Kb | This study |

| FUS1 (5F/6R) | 5’ATCGCTCACTTTGGCACTCA 3’ | 5’TAAACGCTCTAATATCCCTAACAG 3’ | 2.9 Kb | This study |

| FUS4 (catSpeIF/7salR) | 5’GTTGATCGACTAGTAAGAGGTTC 3’ | 5’GGATTTTCGTCGACATCAAGGGTT 3’ | 2.6 Kb | This study |

| FUS32 F/R | 5’ACCACCGCGCTCTCCAAAGTC 3’ | 5’AACGCCAGATCCAAAGCCAAAAGA 3’ | 3.6 Kb | This study |

| FUS32 R5’F/R | 5’ACACAAAATACAGCGAAAAACAGC | 5’ATCAGGCGGGCAAGAATG 3’ | 754 bp | This study |

| FUS32 RM F/R | 5’AGAATACGGAGAACCCTACAATAA | 5’CCAGCGGCATCAGCACCTT 3’ | 727 bp | This study |

| FUS32 R3’F/R | 5’CAAGGCGACAAGGTGCTGATGC | 5’CCCCACGATTGAATGAAAAAGAGT 3’ | 714 bp | This study |

| qPCR Primers | Forward | Reverse | ||

| ureAF/R | 5’AGTTCCTGGTGAGTTGTTCTT 3’ | 5’TGGAAGTGTGAGCCGATTT 3’ | 120 bp | This study |

| vacAF/R | 5’ATGGAAATACAACAAACACACC 3’ | 5’CCAACAATGGCTGGAATGA 3 | 137 bp | This study |

| vapDF/R | 5’ATGTATGCTTTAGCGTTTG 3’ | 5’GGATTTCACAATCTCAGTAA 3’ | 285 bp | Ping Cao |

| 16sHp F/R | 5’GCAAGCGTTACTCGGAATCA 3’ | 5’ACCTACCTCTCCCACACTCTA 3’ | 126 bp | This study |

| TaqMan probes | MGB Probe | |||

| ureA | NED-TGAAGACATCACTATCAACGAAGGCA | 26 bp | This study | |

| vacA | VIC-ACTTTGTTGCGGTGTGATGCTGAC | 24 bp | This study | |

| vapD | FAM-AGAGCGTTTAAGGTAGAGGACTTTAGCGA | 29 bp | This study | |

| 16sHp | NED-TAGGCGGGATAGTCAGTCAGGTGT | 24 bp | This study | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).