1. Introduction

Helicobacter pylori (H. pylori) infection is seen in more than half of the world’s population and is the primary cause of acute and chronic gastritis, ulcers, and gastric cancer by colonizing the antrum and corpus of the human stomach. H. pylori is a spiral-structured, microaerophilic, gram-negative bacterium that moves via flagella, and the prevalence of H. pylori varies regionally and is lower in socioeconomically developed countries.

The specific properties of bacteria that are effective in reaching the gastric epithelium, surviving in the acidic environment, and adhering to the epithelial surface by avoiding the peristaltic movements of the stomach are called virulence factors. Virulence factors play an active role in the bacteria’s reaching the gastric epithelium, attachment, and initiation of colonization. While the urease activity of the bacteria supports its survival in the stomach’s acidic environment, the virulence factors CagA and VacA have been shown to play an active role in the development of pathogen-related diseases [

1,

2]. Bacterial outer membrane proteins interact with cellular receptors to protect the bacteria from mechanisms like acidic pH, mucus, and exfoliation of the stomach [

3,

4].

In the presence of AlpA, AlpB, and BabA proteins, an increased inflammatory response was observed [

5,

6], and BabB and HopQ proteins were found to support the formation of gastric lesions [

7,

8]. In addition, the presence of BabA, SabA, and OipA proteins was evaluated as a biomarker for gastric cancer [

9]. Although it is known that the outer membrane proteins of the bacteria are very effective in the pathogenesis of the bacteria, it has not yet been clarified which mechanisms they affect in the development of diseases.

Pyroptosis is a lytic, inflammatory programmed cell death programmed against intracellular microbial pathogens however, this beneficial mechanism can cause tissue damage by causing autoimmune and auto-inflammatory responses. NOD-like receptor family pyrin domain-containing 3 (NLRP3), Apoptosis-associated speck-like protein (ASC), Caspase-1, Gasdermin D, IL-1β, and IL-18 are the key molecules involved in pyroptosis. These molecules drive the pyroptotic process by leading to cell lysis and inflammation.

NLRP3 acts as a sensor, detecting cellular stress and damage, and is a key part of the inflammasome. ASC Functions as an adaptor, linking NLRP3 to Caspase-1. Caspase-1 is an enzyme activated by the inflammasome, it cleaves pro-inflammatory cytokines and Gasdermin D. Gasdermin D forms pores in the cell membrane, leading to pyroptosis. IL-1β and IL-18 are pro-inflammatory cytokines released during pyroptosis, amplifying the immune response. In the mechanism of pyroptosis, pathogen-associated molecular patterns (PAMP) cause NLRP3 inflammasome formation. Caspase-1, activated by this inflammasome, causes the differentiation of IL-1β and IL-18 from the pro-form to the active form, thus splitting the GSDMD protein into two. The GSDMD-N terminal integrates into the cell membrane and forms pores. Inflammatory cytokines are released from the pores on the cell surface into the surrounding environment, and osmotic lysis occurs due to the entry of fluid into the cell.

Moreover, it was observed that the expression of pyroptosis markers was higher in patients with gastric cancer infected with

H. pylori [

10]. In a study by Zhang, it was shown that

H. pylori CagA virulence factor activates the NLRP3 inflammasome to promote gastric cancer cell migration and invasion. At the same time, in infection experiments using CagA+ and CagA-

H. pylori strain in 2021, the expression levels of NLRP3, ASC, IL-1β and IL-18 were higher as a result of CagA+

H. pylori infection compared to CagA- strains. Similarly, infection with CagA+ strains has been shown to increase the NLRP3 inflammatory response and increase the potential for cancer and cell migration in the stomach by stimulating ROS generation [

11]. Despite these, no studies have specifically explored the association between pyroptosis and

H. pylori outer membrane proteins concerning pathogen-related diseases. To this end, this study seeks to address this gap in the existing literature.

2. Materials and Methods

Obtaining Patient Gastric Tissue Samples

The number of samples to be included in the study was determined using statistical power analysis, suggesting that tissue collection from 22 gastritis and 22 ulcer patients and a control group not infected with H. pylori (5 gastritis patients, 5 ulcer patients, and 5 patients with normal histology) was necessary for the study to be meaningful. In the a priori power analysis for single factor ANOVA, the type 1 error was taken as 0.05 and the type 2 error as 0.20. Based on studies of similar effects in the literature, a medium-sized effect was determined as f = 0.4. The analysis made for 3 independent groups calculated how many individuals should be taken per group for 80% power.

The research permit required to continue the study was obtained from Acıbadem Mehmet Ali Aydınlar University and Acıbadem Healthcare Institutions Medical Research Ethics Committee (ATADEK). Gastric tissue samples to be included in the study were obtained from volunteer patients at Acıbadem Maslak Hospital, Gastroenterology Clinic in Istanbul who underwent an endoscope because of gastroduodenal diseases. A total of 121 patients were chosen based on specific criteria for enrollment in the study. These criteria include being under 18 years old, over 65 years old with an active infection, having cancer or inflammatory disease, experiencing gastrointestinal bleeding in the past month, having previous gastrointestinal surgery, diagnosed with chronic liver failure or renal failure, being diabetic, pregnant, previously treated for H. pylori infection, receiving immunosuppressive therapy or steroids, using NSAIDs or antibiotics in the last three weeks, taking antisecretory medication in the last two weeks, or refusing to sign the informed consent form voluntarily. In tissue samples, H. pylori infection was determined by pathology report.

Tissue samples taken from the antrum region of the stomach during gastroscopy were taken into 400 µl of stabilizer solution (SIGMA-ALDRICH), for stabilization of DNA, RNA, and protein in tissue extracts and stored at -80°C. With the help of the unique composition of stabilizer solution, the isolation of proteins with functional activity while preserving the integrity of nucleic acids is available. H. pylori-negative individuals with gastritis and ulcers and also H. pylori-negative healthy patients were included in the study as a control group.

Isolation of DNA, RNA, and protein from patient tissue samples

H. pylori-infected 22 gastritis patients and 22 ulcer patients were selected from the collected tissues. As the control group, 5 gastritis and 5 ulcer patients, and 5 volunteers with normal histological features without bacterial infection were selected. Tissue samples were fragmented using a homogenizer (BioSpec) through metal beads. DNA and RNA isolation were performed as specified in the protocol of the Duet DNA/RNA MiniPrep Plus kit (Zymo Research), and acetone precipitate was continued for protein isolation. During the protein isolation period, four times the volume of cold acetone was added to the lysate expressing the protein content and incubated at -20°C for one hour after vortexing. After centrifugation at 13.000 g for 10 minutes, the supernatant was removed, and the protein-containing pellet was left to dry for 30 minutes under a hood to remove the remaining acetone. The resulting pellets were dissolved by vortexing in 250 µl, 160 mM Tris hydrochloride Tris-HCl (pH = 6.8) containing 2% SDS. The concentrations of the obtained DNAs and RNAs were measured in the nanodrop device and the BCA protein assay kit (Pierce,) was used to determine the concentration of protein samples.

Investigation of the Presence of Bacterial Virulence Genes by Conventional PCR

The presence of

ureA, ureB, cagA, vacA m and

s alleles and

alpA, alpB, sabA, sabB, hopQ, hopZ, oipA, labA, babA2, babB, and

babC genes in

H. pylori-infected patient groups was investigated by PCR reaction. The genomic DNA of the

H. pylori G27 strain, which is known to express all virulence genes of the bacteria, was used as a positive control in the study. All primers used in the study are given in

Table 1 together with their annealing temperatures. After the PCR reaction, the samples were run in 1.5% agarose gel and stained with EtBr and the presence/absence of virulence genes was detected by ChemiDoc (Biorad) instrument.

Investigation of the Expression of NLRP3 and ASC Levels by Real-Time PCR

Using the obtained cDNA products, the expression levels of NLRP3 and ASC in patient samples were investigated at the RNA level. GAPDH gene-specific primer was used as housekeeping in the experiments, and normalization was done according to the GAPDH expression of patient samples. Primers used in RT-PCR experiments can be seen in

Table 1.

Evaluation of Expressions of GSDMD Caspase-1 IL-18 and IL-1β by Western Blot

To compare the expression levels of the markers known to be activated in the pyroptosis process, protein samples belonging to different patient groups were run on 12% SDS-PAGE and PVDF membrane by the wet transfer method. The membrane was blotted with GSDMD (1:750, St John’s,), caspase-1 (1:1000, St John’s,), IL18 (1:1000 St John’s,), and IL1β (1:2000, St John’s,), which can detect pro and active forms of target markers. After the target bands were detected with ChemiDoc (BioRad,), the membrane was stripped bound antibodies were removed and the membrane was reblotted with β-actin (1:1000, Cell Signaling) for normalization. For the stripping, the membrane was washed three times with strip buffer (1-liter strip buffer components (pH=2,2): 15 g glycine, 1 g SDS, 10 ml Tween-20.) for 10 minutes. Afterward, the membrane was washed twice with PBS and once with TBS-T buffer for 10 minutes.

Statistical Analysis

To examine the effects of bacterial virulence gene and pyroptosis marker expression on pathogen-related diseases, we analyzed the experimental data using GraphPad Prism (9.0.0). The distribution of virulence genes in gastritis and ulcer patients was evaluated using the Chi-square test, and associated risk factors were calculated. The relationship between ASC, NLRP3, and both forms of GSDMD, caspase-1, IL-18, and IL-1β expression levels was assessed using the Kruskal-Wallis test for each patient.

Based on qRT-PCR and Western Blot results, a correlation matrix was generated for each patient group to examine the relationship between the marker expression levels. To investigate the frequency of co-expression, Pearson correlation coefficients and p-values were calculated. Additionally, scatter plots were used to explore the relationship between pro and active forms of target markers in each patient group. In patients with increased pyroptosis responses, p values were calculated to assess the presence of bacterial virulence genes. For each virulence gene, patients expressing the gene were selected from the population, and the data was analyzed using the Kruskal-Wallis test. The significance value was set to 0.05 for all analyses.

3. Results

A total of 121 patient tissues were collected. Among these, 50 tissues were detected to be infected with

H. pylori (41.2%). Tissues from 22 gastritis and 22 ulcer patients were selected from the collected tissues, and 5 uninfected gastritis patients, 5 uninfected ulcer patients, and 5 volunteers with normal histology were included in the study as controls. Gender and age distributions of these patients were given in

Table 2.

The presence of virulence genes of

H. pylori in DNA samples isolated from patient tissues was investigated by conventional PCR. The frequency of virulence genes in patient groups and the

p values and relative risks calculated using Pearson’s Chi-square Fisher’s Exact test are given in

Table 3. While the

ureB, hopZ, hopQ, and

alpA genes were seen in all ulcer patients, the

ureA gene was found in all gastritis and ulcer patients infected with

H. pylori. No variability was found in the incidence of the

sabB gene in patients with gastritis and ulcers. The

babA2, babB, babC, and

labA genes were more common in gastritis patients than ulcer patients

. ureB, cagA, oipA, sabA, alpA, alpB, hopZ, and

hopQ genes were seen more frequently in ulcer patients than in gastritis patients. Alleles of the

vacA gene are frequently seen in

s1 and

m2 alleles in ulcer patients, while the opposite is true for gastritis patients. Chi-square Fisher’s Exact test was performed using GraphPad Prism (9.0.0) to examine the distribution of virulence genes of bacteria in different patient groups.

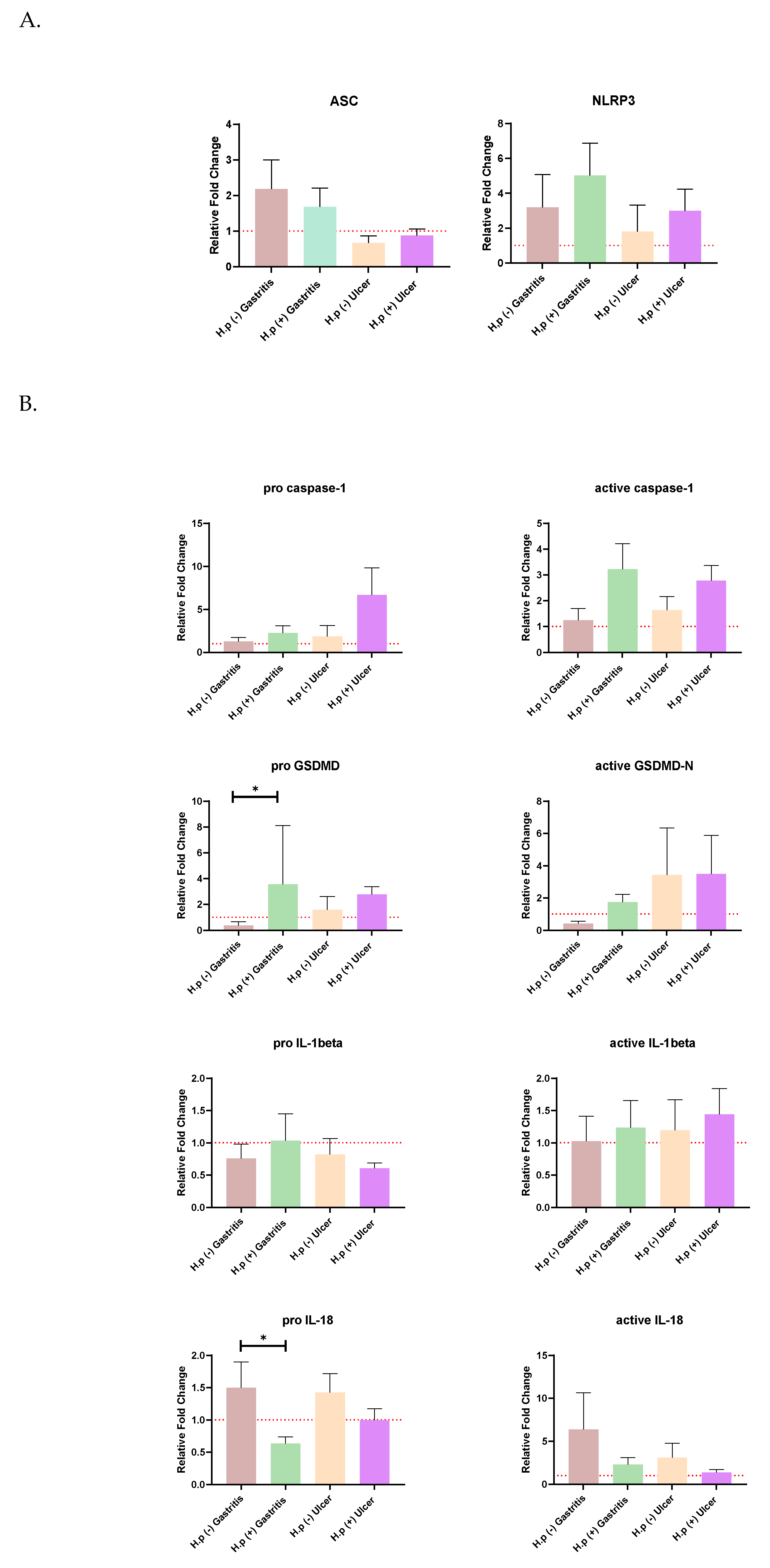

The distribution of relative fold change ratios of the ASC and NRLP3 genes and, both forms of GSDMD, caspase-1, IL-18, and IL-1β expression levels in different patient groups is given in

Figure 1. The Kruskal-Wallis test was used to test the significance of the mean ratio of target markers to housekeeping markers expression in four different patient groups by using GraphPad Prism (9.0.0). The alpha value of 0.05 was chosen. It was found to be statistically significant when

p <0.05 and this is indicated by an asterisk sign. The graphs were prepared according to the mean with SEM value.

Changes in ASC and NLRP3 expressions were not significant for any patient group (

Figure 1A). It has been observed that the ASC gene is expressed more in gastritis patients than in ulcer patients. In addition,

H. pylori infection increased the expression levels of both ASC and NLRP3 in ulcer patients.

When the expression of the pro and active forms of Caspase-1 was examined,

H. pylori infection increased the expression in both gastritis and ulcer patients. A similar relationship was also seen for pro-GSDMD expression, and the pro-GSDMD variation between uninfected gastritis and infected gastritis expression levels was statistically significant. Expression of the pro and mature forms of IL-18 is decreased with

H. pylori infection, especially the amount of pro-IL18, which is significantly higher in uninfected gastritis patients than in infected patients. Mature Il-1β was upregulated in the presence of ulcers in both control and infected patients (

Figure 1B).

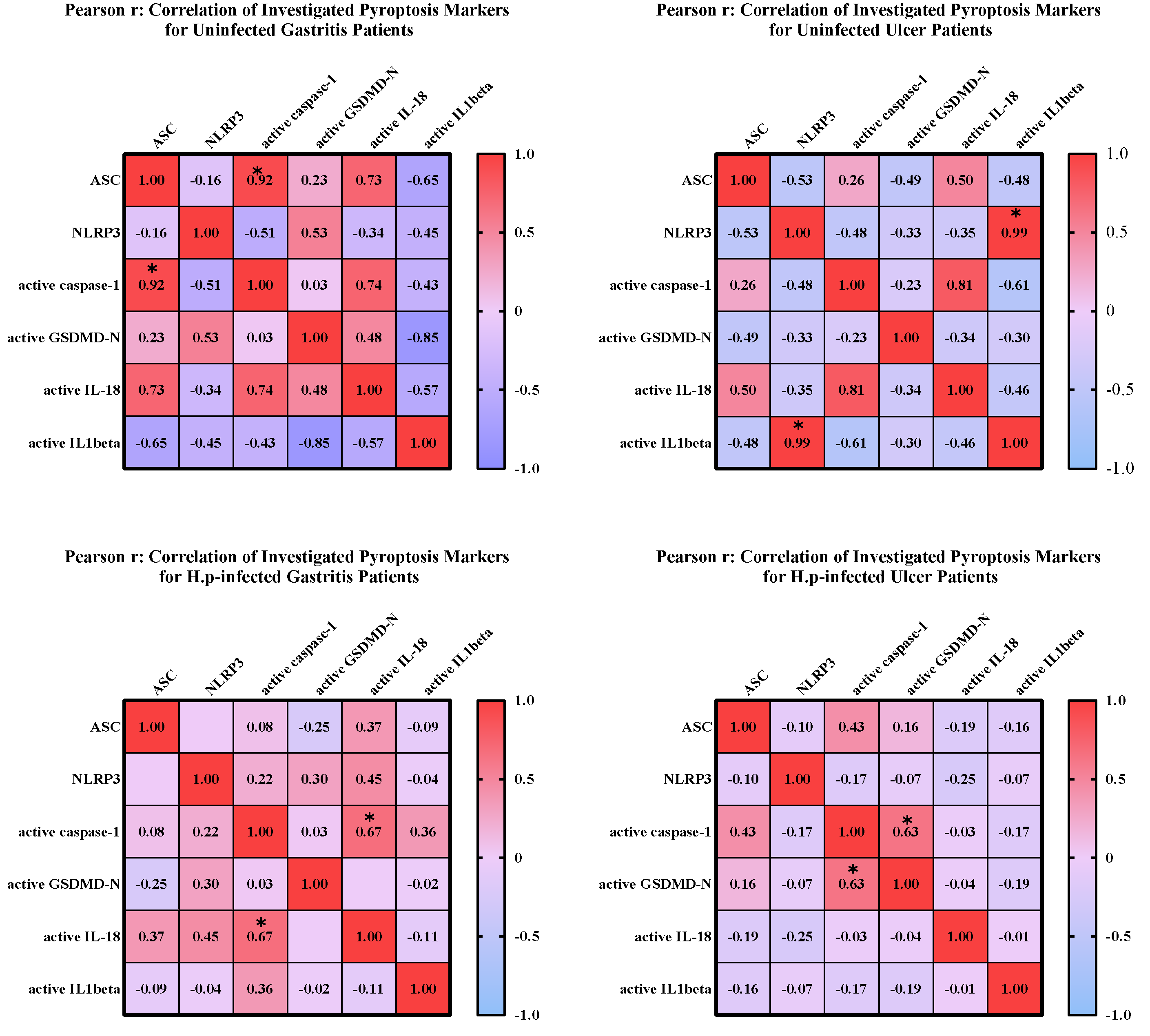

To investigate the relationship between mature and pro-forms of target markers, correlation matrices were created, and the linearity and strength of the relationship between pro and active forms were evaluated. Heatmaps were created using GraphPad Prism (9.0.0) (

Figure 2).

In uninfected ulcer patients, a significant correlation was seen between NLRP3 expression and IL-1β expression. Similarly, there is a relationship between the active forms of caspase-1 and IL-18. Besides, a negative correlation was observed between the expression levels of NLRP3 and ASC genes. The correlation between expression levels of mature caspase-1 and mature-IL18 was significant in patients with gastritis infected with

H. pylori. No relationship was found between other markers in this patient group. Similarly, active caspase-1 and GSDMD-N levels were found to be significantly correlated in

H. pylori-infected ulcer patients (

Figure 2).

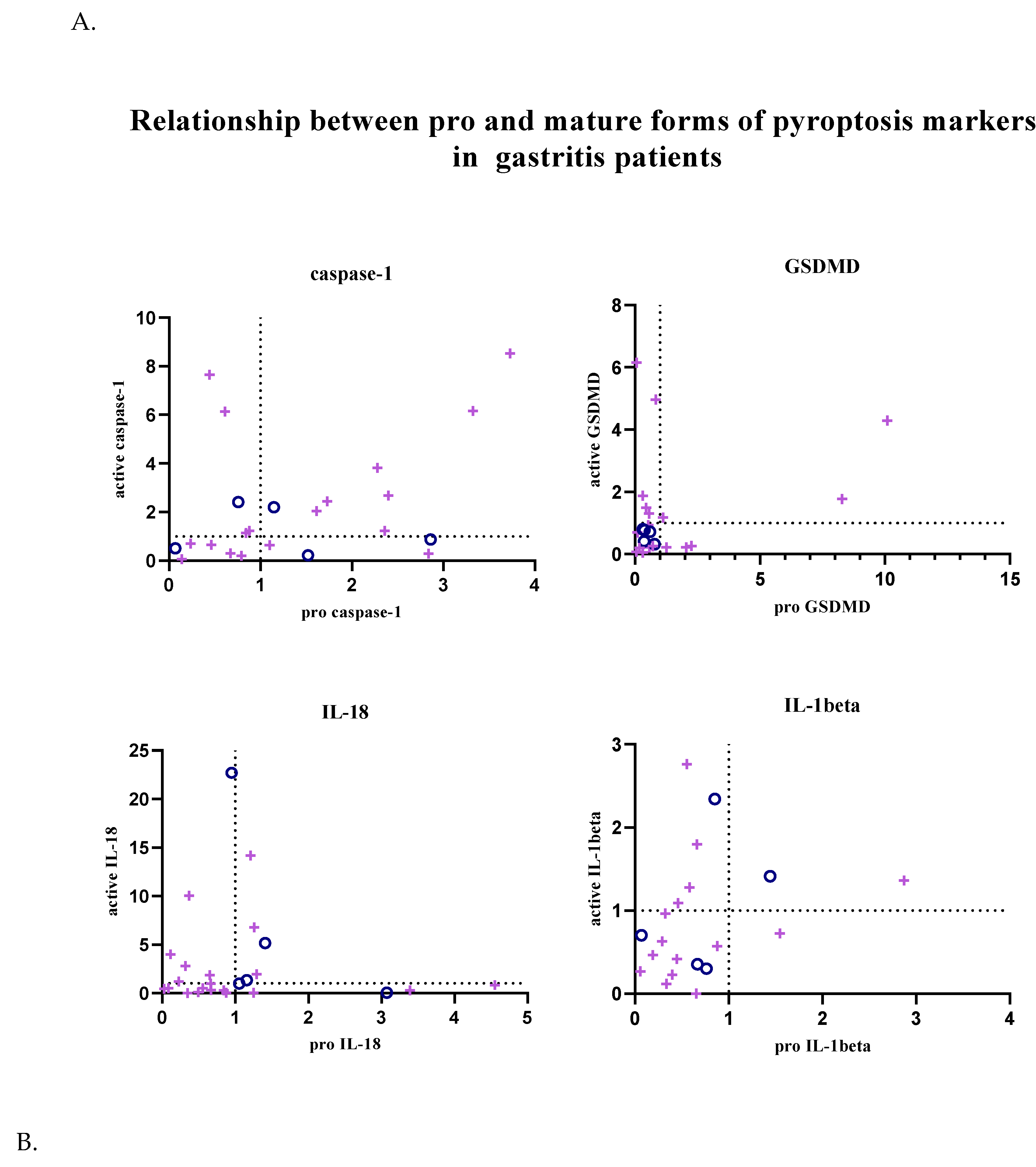

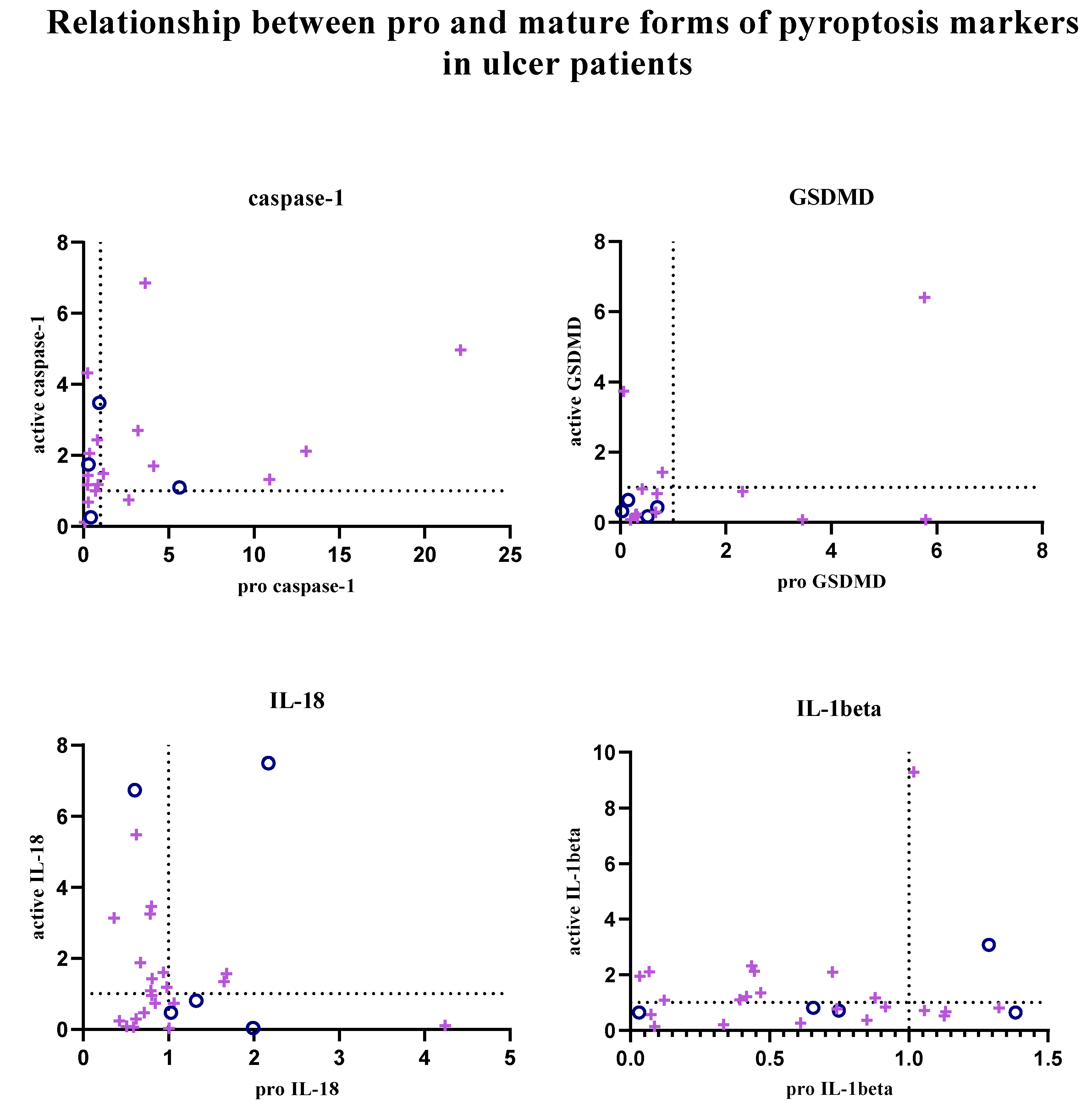

In addition, the relationship between pro and active forms of target markers was examined; graphs showing the balance between active and pro forms of target markers in each patient sample are given in

Figure 3. Graphs were created using GraphPad Prism (9.0.0).

In patients with gastritis (72.2%) and ulcers (84.6%) infected with H. pylori, concomitance between pro and active forms of caspase-1 is more common than in patients with gastritis (40%) and ulcers (50%) without infection. While the expression of pro and mature forms of caspase-1 is increased in 44.4% of infected gastritis patients compared to the control group, the incidence of this situation in infected ulcer patients is 41.2%. In addition to all these, in 4 infected gastritis patients (22.2% of the population) and 6 infected ulcer patients (35.3% of the population), caspase-1 expression was lower in the pro-form compared to the control group, while the expression level was increased in the active form (Figure 3A-B).

The expression of the active and pro-forms of GSDMD was generally decreased compared to the control group, and the relationship between the pro and active forms was completely simultaneous in uninfected gastritis and ulcer patients (Figure 3A-B). In the infected patient groups, GSDMD expression changed simultaneously in 66.7% of the population in the presence of gastritis and synchronously in 80% of ulcer patients. Expression of both forms of GSDMD was decreased in 38.9% of infected gastritis patients, but this was seen in 70% of infected ulcer patients. Uninfected patients did not show highly mature GSDMD-N and less pro-GSDMD expression, as was the case in 27.8% of infected gastritis patients and 10% of infected ulcer patients.

IL-18 expression is frequently altered simultaneously in infected gastritis patients (60%). Relative fold change values were found to be less than 1 in 45% of this patient group. In patients with pathogen-infected ulcers, this ratio is 38.1%. Also, increased mature IL-18 expression and low pro-IL-18 levels were the most common in the infected ulcer population (42.9% of the population). Similarly, while mature IL-18 was upregulated, infected gastritis patients in whom the pro form was downregulated (20% of the population) were more common than when the two forms were upregulated together (Figure 3A-B).

Expression of IL-1β tended to be simultaneous when down-regulated in uninfected patient groups, but expression of IL-1β was not commonly found in infected patient groups. Simultaneity was observed in 66.7% of infected gastritis patients, whereas only 36.4% of infected ulcer patients were similarly identified. In H. pylori-infected ulcer patients, upregulation of active IL-1β and downregulation of pro-IL-1β was seen in 45.5% of the population, compared with 26.7% of infected gastritis patients (Figure 3A-B).

To examine the relationship between the increased expression of pyroptosis markers and the virulence factors of

H. pylori, the presence of virulence factors in patient tissues where each marker was upregulated was investigated by GraphPad Prism (9.0.0) and Pearson r values and relative risk factors are given in

Table 4. When the presence of the

alpA gene was examined in patients with increased GSDMD expression, it was found to be statistically significant.

The patient population was divided into two groups based on the presence of virulence genes. Kruskal Wallis analysis was performed to compare the expression levels of pyroptosis markers across these groups. The significance level was set to 0.05. Statistically significant results were indicated by an asterisk (*p <0.05). The graphs in supplementary data show mean and SEM values.

In gastritis patients, the presence of the

vacA m2 allele, the ASC gene was significantly downregulated compared to the uninfected gastritis patient group. When infected ulcer patients were examined, it was observed that the presence of

babA, GSDMD-N expression was found to be significantly upregulated compared to its absence of these genes. In particular, the expression of the ASC gene was significantly increased compared to uninfected ulcer patients (

Table 4).

4. Discussion

Virulence factors play an active role in H. pylori’s reaching the gastric epithelium, attachment, and initiation of colonization. Also, the presence of specific virulence genes, such as vacA and cagA, are important for the development of H. pylori-related gastric disease and may have an immediate impact on clinical results. CagA-positive strains, for instance, have been linked to peptic ulcers, more severe stomach inflammation, and even a higher risk of gastric cancer. Clinicians may be able to classify patients according to the possible severity of the infection by identifying the strain-specific virulence factors. More aggressive treatment strategies may be guided by this categorization, especially when patients are infected with extremely virulent strains of the bacteri, like those that possess the cagA gene. VacA, a noteworthy virulence factor, is recognized for its capacity to trigger cell vacuolation and death, exacerbating mucosal injury. Gaining insight into the distribution of vacA alleles may help anticipate the course of the disease and enable customized treatment. One of the most important virulence factors the outer membrane proteins (OMPs) of H. pylori play crucial roles in the bacterium’s ability to colonize the stomach, interact with host cells, and evade the immune system. These proteins are essential for H. pylori’s pathogenicity, contributing to its ability to establish chronic infections. Although the significant role of the outer membrane proteins of H. pylori in bacterial infection, the precise mechanisms by which these factors influence pyroptosis, a form of programmed cell death and bacterial infection triggered mechanism associated with inflammation, remains unclear and the activation or modulation of this pathway has not yet been fully elucidated.

In this study, our molecular analysis of bacterial virulence factors and pyroptosis markers in a single tissue biopsy allowed us to investigate the relationship between pathogen characteristics and controlled cell death in H. pylori-associated diseases.

A previous study indicated that the prevalence of H. pylori in Turkey exceeded 80% [

20]. However, in this study, the prevalence of

H. pylori was determined to be 41.2% among the patients evaluated. Given that the prevalence of

H. pylori is known to decline with socioeconomic development, the selection of a private hospital in Istanbul may account for the observed lower prevalence of the pathogen.

In this study, it was observed that babA2, babC, and labA genes were more common in gastritis patients than in ulcer patients. Additionally, ureB, cagA, oipA, sabA, alpA, alpB, hopZ, and hopQ genes were more frequently reported in ulcer patients than in gastritis patients. In addition, s1 and m2 alleles of the vacA gene were found to be more common in ulcer patients. H. pyloriThe relative risk values for ureB, cagA, vacA s1 and m1, sabA, sabB, hopQ, hopZ, alpA, alpB, and, oipA, which are highly expressed in ulcer patients, were higher than 1, implying a contributory impact of these genes to ulcer development. These findings align with the literature, which indicates that the expressions of oipA, sabA, hopQ, cagA, and vacA s1 and m2 alleles are associated with gastric ulcer development (21-23). However, the direction of the relationship between these other virulence genes and H. pylori-associated ulcers has not been examined until this study.

When investigating the ASC and NLRP3 expressions, the ASC gene was found to be relatively more expressed in gastritis patients than in ulcer patients, and higher expression was observed in

H. pylori-infected ulcer patients compared to uninfected ulcer patients. This is consistent with ın a clinical study published in the literature in 2023 [

24]. Also,

H. pylori infection increased NLRP3 expression in both gastritis and ulcer patients. The active and pro form of caspase-1 expression was found to increase with

H. pylori infection. The amount of pro-GSDMD was significantly increased in infected gastritis patients compared to uninfected patients. A similar relationship is also valid for active GSDMD, but it was not found to be statistically significant. There is no study in the literature examining the expression of GSDMD in patient samples. Expression of Pro-IL-1β was increased in patients with gastritis in the presence of infection and decreased in patients with ulcers, but its active form was found to be expressed at a higher rate in both infected gastritis and infected ulcer patients. In the literature, a clinical study conducted by Milic et al., higher IL-1β levels were detected in infected ulcer patients than in uninfected patients [

25]. This situation suggested that

H. pylori infection stimulates IL-1β at the beginning of infection and may be effective in its activation in pathogen-related diseases. Significant higher IL-18 expression was seen in uninfected gastritis patients compared to infected gastritis patients. Presence of

H. pylori infection and expression of IL-18 varied inversely. It has previously been shown that IL-18 expression is increased in the case of

H. pylori infection, which is inconsistent with the data obtained in this study [

26]. However, in a study conducted on Mongolian gerbils, IL-18 and IL-1beta expressions were increased in the gastric mucosa in the first month of

H. pylori infection, but the expression level decreased to the baseline level at the sixth month of infection [

27]. This suggested that the expressions of these inflammasome markers may vary depending on the duration of infection. In addition, since the inflammation starts from the antrum region of the stomach and spreads to other parts, the increase in this region does not allow a generalization in terms of the whole stomach.

A statistically significant positive correlation was reported between the mature caspase-1 and ASC expressions in patients with uninfected gastritis. Furthermore, higher ASC expression was linked to increased IL-18 and caspase-1 expression. On the other hand, IL-1 expression was shown to be negatively correlated with ASC, GSDMD-N, and IL-18 expression. NLRP3 and caspase-1 expressions showed a similar negative association. There was a significant association between NLRP3 expression and IL-1 expression in uninfected ulcer patients. Similarly, there is an association between caspase-1 and IL-18 active forms. Furthermore, a negative correlation was found between the expression of the NLRP3 and ASC genes. The correlation between the expression levels of mature caspase-1 and mature-IL 18 was the only significant association detected in H. pylori-infected gastritis patients. Similarly, in H. pylori-infected ulcer patients, activated caspase-1 levels was significantly associated with GSDMD-N. Particularly, GSDMD-N and active forms of IL-18 and IL-1beta increased following the activation of caspase-1 in the canonical pyroptosis pathway REF. Hence, the significant relationship between the expression levels of caspase-1 and these genes shows the competency of our analysis to detect pyroptosis.

The relationship between the regulation of the pro and mature forms of the target markers in the patient groups whose fold change values of the expression levels were calculated compared to the control patient group was examined. Significant data could not be obtained in non-infected patient groups due to the size of the population. In

H. pylori-infected patient groups, upregulation of active and pro-forms of caspase-1 was commonly seen to be simultaneous; however, in GSDMD, IL-18, and IL-1β, synchrony between forms was found to be more common in the down-regulation condition. This indicated that there were patient samples in which the target marker was not synthesized and could not be activated naturally. However, for caspase-1, IL-18, and IL-1β, a significant portion of the population was found to have an upregulated mature form and a downregulated pro-form. It was thought that down-regulation of pro-forms was observed in some patients due to activation after expression, and up-regulation of the mature form was increased as described in the canonical pyroptosis pathway [

28].

When the incidence of bacterial virulence genes in patient groups with upregulated pyroptosis markers is examined, the incidence of

cagA and

babB genes and

vacA s1 alleles tends to increase, and the opposite is true for

oipA, ureB, sabA, and

vacA s2 alleles. It is very important to detect such a relationship between the increase in the presence of the

cagA and

vacA s1 alleles, which are known to support ulceration [

29] and are the most important features of the virulence of the bacteria, and the pyroptosis response. In the literature, the presence of OipA [

30] and SabA [

31] has been associated with the development of peptic ulcers, but in this study, it was seen that the expression of these proteins at the gene level was inversely proportional to the increased pyroptosis response. OipA and SabA proteins can be produced specifically with (“on” status) or without (“off” status) functionality [

32,

33], so the existence of these virulence genes at the gene level may not mean that they can be produced functionally, so looking at their expression at the gene level may have been insufficient to examine their effects on pyroptosis. While the

babA2 gene is more common with increased pyroptotic response in gastritis patients, its incidence is decreased in ulcer patients. On the other hand, the production of BabA has been associated with the development of peptic ulcers and gastric cancer in the literature [

34,

35].

The Kruskal-Wallis test was used to compare the levels of the virulence genes of

H. pylori in patient groups in which pyroptosis markers were upregulated. Especially in the presence of

hopQ and

sabA genes, pyroptosis markers were more frequently upregulated than in uninfected control patient groups. Since

hopQ [

8] and

sabA [

31] expressions were previously associated with ulcer development in the literature, these results suggested that they may have induced pyroptosis while stimulating tissue damage caused by infection. While the incidence of the

sabA gene decreased in patients with pyroptosis-induced, an increased pyroptosis response was observed in patients expressing the

sabA gene, suggesting that this gene is not seen frequently, but if it is present, it plays an active role in pyroptosis. The small size of the population has been a limiting factor in better understanding this relationship.

In addition, GSDMD-N expression is significantly higher in infected ulcer patients in whom the babB gene is expressed than in patients who do not express this gene. Moreover, in gastritis patients without the labA gene, the expression of the ASC gene was significantly decreased compared to the control group. Although there is not much information about labA and babB in the literature, the relationship between these genes and increased pyroptosis response should be examined in more detail.

The changes in the amount of ASC due to the absence of the vacA m2 allele in infected gastritis patients and the presence of the same allele in infected ulcer patients were found to be statistically significant. This showed that the vacA m2 allele, which is known to have an active effect on ulcer development, may support the ulceration potential by increasing the amount of ASC. This situation suggested that pyroptosis might be the effective mechanism in bacterial gastric ulcer formation and that the vacA m2 allele might play an active role in the process.

Combining the data, the vacA m2 allele, which elicits an opposite and significant ASC response in patients with gastritis and ulcer, and the babB gene, with its increased incidence, and upregulation of GSDMD in ulcer disease, emerged as two important candidates for future studies.

Although the infection in the stomach generally starts in the antrum region, the inflammatory response in tissue samples taken only from the antrum region may be insufficient to express the general stomach. Moreover, the periodic increase and decrease of markers during pyroptosis, instead of showing a linear increase, was another limiting factor encountered in the study. In addition to these disadvantages, this study is very valuable as the relationship between bacterial virulence genes and pyroptosis has been examined for the first time in this study. It has been observed that the pathogen is effective in pyroptosis, and two virulence factors whose functions have not been fully determined in H. pylori-related pathology have the potential to be directly associated with pyroptosis as a result of more extensive studies. Future studies should continue to examine the relationship between the virulence characteristics of bacteria and pyroptosis in H. pylori-related diseases.

In conclusion, it was observed that H. pylori infection caused changes in the expression levels of ASC, NLRP3, caspase-1, GSDMD, IL-18, and IL-1β, and it was determined that there was a correlation between pyroptosis markers and pathogen-related diseases. The statistically significant change in the relationship between the increase in the amounts of target markers and active caspase-1 in different patient groups showed that the detection of pyroptosis was successful. The expression of the vacA m2 allele was significantly decreased in gastritis patients, while it was significantly increased in ulcer patients. GSDMD upregulation in ulcer disease and the babB gene are prominent for understanding the relationship between the virulence factors of H. pylori and pyroptosis in bacteria-associated diseases. These data shed light on a deficiency in the literature. This study presents some limitations, including the relatively small group sizes for both the gastritis and ulcer patients. For future aspects, it would be meaningful to expand the study to larger patient populations and include other bacterial-associated patient groups, such as patients with gastric cancer.