1. Introduction

Environmental, Social, and Governance (ESG) investing has gained considerable momentum in global capital markets over the past two decades, reshaping the way financial actors assess firm performance and long-term value creation. ESG factors—ranging from carbon emissions and labor practices to executive compensation and board transparency—have emerged as critical dimensions of corporate evaluation beyond traditional financial metrics [

1,

2]. This shift reflects a growing recognition that sustainable business practices are not only ethically and socially desirable but can also influence firm risk profiles, access to capital, and valuation over time [

3,

4].

The increasing institutional attention to ESG arises in part from the dual pressures of regulatory development and stakeholder expectations. Asset managers, pension funds, and sovereign wealth funds have begun integrating ESG criteria into their investment decisions, both to fulfill fiduciary duties and to manage reputational and long-term financial risks [

5,

6]. Parallel to this, global sustainability initiatives and climate-related financial disclosures have added urgency and structure to corporate ESG reporting. Despite this rapid uptake, the debate continues: Does ESG performance tangibly influence market capitalization, or is it primarily a reflection of shifting investor sentiment and signaling dynamics [

23]?

This review addresses the central research question: To what extent does ESG performance correlate with a firm’s market capitalization? While some scholars argue that high ESG ratings improve investor confidence and reduce the cost of capital [

7,

8], others caution that rating inconsistencies, regulatory fragmentation, and greenwashing undermine the predictive power of ESG indicators [

9,

10]. Moreover, the impact of ESG factors appears to vary widely across sectors and geographies, suggesting that the relationship between sustainability and firm valuation is complex and context-dependent [

11,

12].

To clarify these divergent perspectives, the present study conducts a systematic review of empirical findings using the PRISMA 2020 framework [

13]. Drawing from peer-reviewed literature published between 2020 and 2025, we identify and synthesize the results of ten rigorous quantitative studies that explore the relationship between ESG metrics and firm value. By analyzing methodological choices, sectoral focus, regional settings, and reported outcomes, this review aims to offer an integrated understanding of how ESG performance is linked to market capitalization, and under what conditions.

The findings indicate that while ESG generally exerts a positive influence on firm valuation—particularly in highly regulated or capital-intensive industries—the strength and stability of this effect vary based on regulatory clarity, investor behavior, and data transparency. This review thus contributes to the academic discourse by clarifying the boundaries and mechanisms through which ESG matters to financial performance and provides policy and managerial recommendations to improve ESG integration and standardization in financial decision-making.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Review Design

This study adopts a systematic literature review (SLR) approach, following the PRISMA 2020 (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses) guidelines [

14]. PRISMA was selected for its rigor, transparency, and replicability, which are crucial in structuring a review that synthesizes evidence across empirical studies. The purpose of this review is to consolidate and analyze peer-reviewed literature that investigates the relationship between Environmental, Social, and Governance (ESG) performance and firm market capitalization, providing clarity on the extent, direction, and variation of this association.

The SLR methodology ensures that the process of identifying, screening, and selecting studies is both systematic and unbiased. This review does not involve primary data collection or meta-analysis but instead focuses on synthesizing recent empirical research based on quantitative data. The approach aims to answer the guiding question: Does ESG performance have a statistically significant impact on a firm’s market capitalization across sectors and geographies?

To achieve this, the following steps were implemented:

Formulation of research objectives and eligibility criteria.

Comprehensive search across selected academic databases.

Application of inclusion/exclusion filters.

Assessment of study quality and extraction of key variables.

Synthesis and narrative analysis of findings.

2.2. Databases Searched

The literature search was conducted across four major and reputable academic databases, chosen for their breadth and coverage of finance, economics, and sustainability-related publications:

These platforms provide comprehensive access to peer-reviewed journal articles, conference proceedings, and high-quality working papers in the fields of financial economics, corporate governance, sustainability studies, and business analytics. The search targeted documents published between January 2020 and February 2025, ensuring that the evidence base reflects contemporary perspectives, regulatory developments, and ESG methodologies relevant to current investment practices.

2.3. Search Strategy and Keywords

A structured and replicable search strategy was employed to identify relevant studies. Search terms were developed through preliminary scoping, incorporating terminology used in key ESG-investing literature and aligning with the central research question. Boolean operators (AND/OR) were used to combine thematic areas and refine the search.

The following search string was applied (with slight adaptations depending on database syntax):

(“Environmental, Social, and Governance” OR “ESG investment” OR “sustainability investing”)

AND (“market capitalization” OR “firm value” OR “financial performance”)

AND (“quantitative study” OR “empirical analysis” OR “financial correlation”)

Each term was searched within titles, abstracts, and keywords. Where possible, filters were applied to restrict results to peer-reviewed articles and exclude opinion pieces, editorials, or purely theoretical works.

Initial search results yielded:

Scopus: 150 records

Web of Science: 130 records

ScienceDirect: 120 records

SSRN: 100 records

Other sources (e.g., working paper repositories): 50 records

This led to a total of 550 records initially identified for screening.

2.4. Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

To ensure relevance and quality, the following criteria were used:

2.4.1. Inclusion Criteria

Empirical studies examining the relationship between ESG performance and firm market capitalization.

Use of quantitative methods, including regression analysis, panel data models, and financial correlation techniques.

Published in peer-reviewed journals or high-impact working paper series.

Coverage of regional and sectoral data to ensure heterogeneity in results.

Articles in English.

2.4.2. Exclusion Criteria

Conceptual or theoretical papers without empirical financial analysis.

Studies focusing solely on ESG disclosure, perception, or policy frameworks, without testing a link to market capitalization.

Meta-analyses or review papers (to avoid redundancy).

Duplicate records or inaccessible full texts.

Non-English publications.

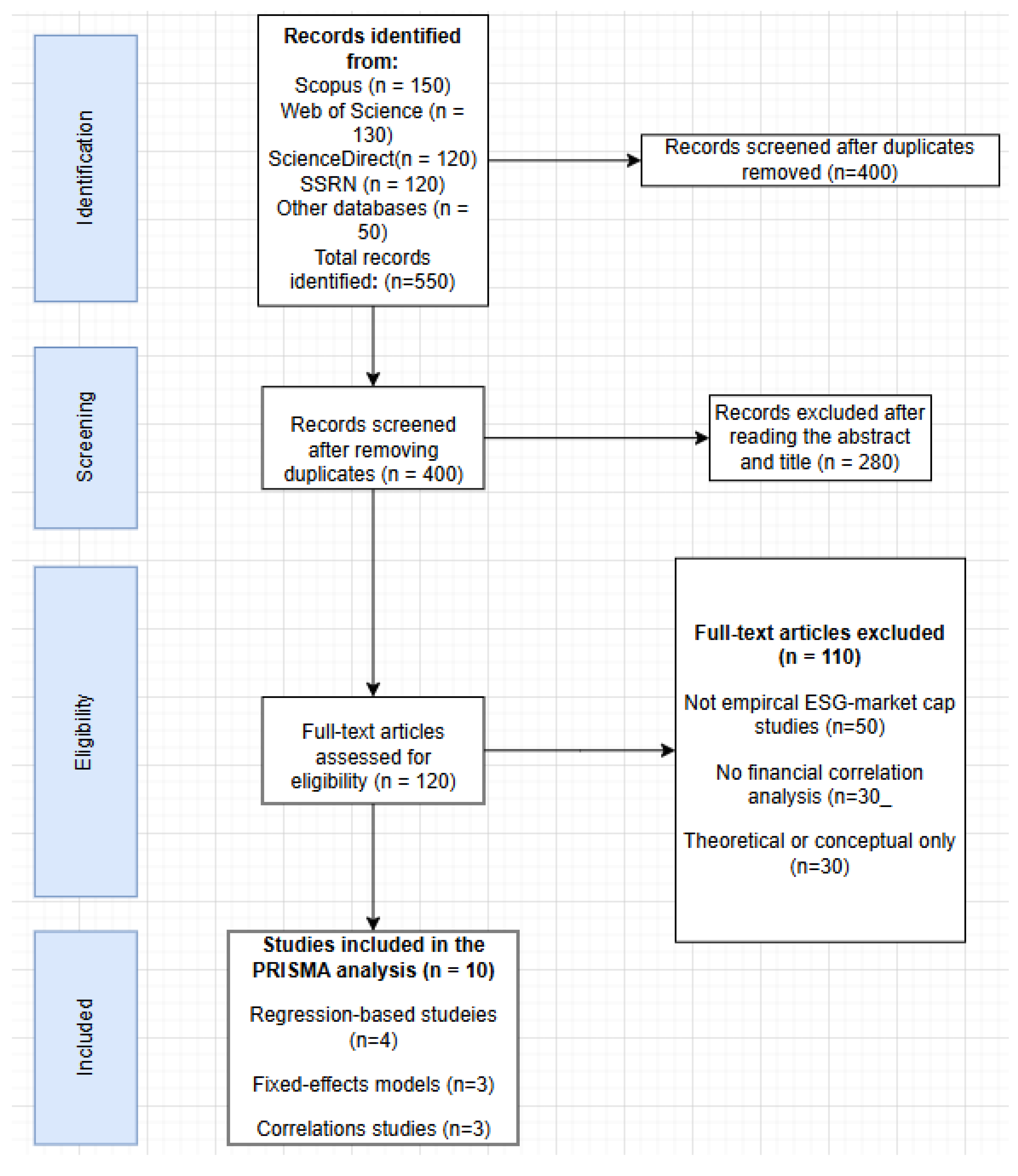

Applying these filters removed 400 records (150 duplicates and 250 irrelevant based on abstract/title screening), leaving 150 full-text articles for eligibility assessment. Of these, 10 studies met all criteria and were included in the final synthesis.

2.5. Study Selection Process

The PRISMA 2020 four-phase flow diagram was used to illustrate the study selection process [

14]:

Identification: 550 records retrieved from databases and other sources.

Screening: 150 duplicates removed; 400 titles/abstracts screened.

Eligibility: 150 full-text articles assessed.

110 excluded due to being non-empirical, irrelevant focus, or lacking market capitalization outcome.

Included: Final selection of 10 empirical studies used in analysis.

Each selected study was independently reviewed for methodological soundness, relevance to the research question, and financial modeling quality.

2.6. Data Extraction and Synthesis

For each of the ten included studies, a structured data extraction framework was applied to ensure methodological consistency and comparability. The framework captured information on the specific ESG performance metrics employed, such as ESG scores provided by agencies like MSCI and Sustainalytics [

22]. It also included details on the financial indicators analyzed, including measures such as market capitalization, cost of capital, and stock price performance. Additionally, the statistical methods utilized in each study were recorded, encompassing approaches such as ordinary least squares (OLS) regression, fixed effects models, and event study analysis. The extraction process further identified the sectoral focus of each study—for instance, whether the analysis concentrated on energy, finance, or technology firms—and the geographical context, distinguishing between developed and emerging market settings. Finally, the key findings of each study were summarized, with attention paid to the direction and magnitude of the reported effects. This structured approach enabled a coherent synthesis of the empirical evidence, facilitating the identification of patterns, divergences, and sector- or region-specific dynamics in the relationship between ESG performance and firm valuation.

2.7. Limitations

While the systematic review methodology enhances the reliability and transparency of the findings, several limitations must be acknowledged. First, the review is subject to potential publication bias, as only published and peer-reviewed studies were included in the final analysis, potentially excluding relevant but unpublished work. Second, inconsistencies in ESG rating methodologies present a challenge, as the studies reviewed employed different ESG data providers, each using distinct criteria and scoring frameworks, which complicates direct comparison and synthesis [

9]. Third, there is a notable sectoral and regional imbalance, with limited representation of firms and financial systems from emerging markets, which may constrain the generalizability of the findings. Lastly, due to methodological heterogeneity across the selected studies—particularly in terms of statistical models, ESG indicators, and financial outcomes—a formal meta-analysis was not feasible, and the synthesis was conducted through a narrative, qualitative approach.

Figure 1.

The PRISMA flowchart.

Figure 1.

The PRISMA flowchart.

4. Discussion

4.1. Interpretation of Results: Support for Stakeholder Theory and Signaling Theory

The consistent positive association between ESG performance and market capitalization across the reviewed studies can be meaningfully interpreted through the lenses of stakeholder theory and signaling theory, two foundational frameworks in corporate governance and finance.

Stakeholder theory, originally developed by Freeman [

19], posits that the long-term success and value of a firm are not determined solely by shareholder wealth maximization, but by the effective management of relationships with a broader set of stakeholders—including employees, customers, suppliers, regulators, and communities. Firms that demonstrate strong environmental stewardship, social responsibility, and ethical governance are perceived as more legitimate, trustworthy, and sustainable. These attributes, in turn, foster stakeholder loyalty, reduce conflict and regulatory risk, and enhance reputational capital—factors that contribute directly to firm valuation.

The findings of Liu, Nemoto, and Lu [

12] provide empirical support for this theoretical perspective. During the COVID-19 crisis, firms with high ESG ratings experienced less volatility and stronger liquidity, suggesting that their stakeholder-focused strategies offered protection amid uncertainty. Similarly, the study by Yi and Yang [

6] shows that Chinese firms with transparent ESG reporting attracted more institutional investors, a form of stakeholder alignment that supports long-term capital stability. These outcomes affirm the stakeholder theory’s core assertion: that firms managing for multiple constituencies build resilience and value over time.

Moreover, the sectoral differences observed in the literature further reinforce stakeholder theory. In highly regulated or publicly scrutinized industries—such as energy, finance, and infrastructure—stakeholders play a particularly influential role in determining access to capital, license to operate, and brand equity. Studies such as Moolkham [

4] and Vochenko et al. [

15] confirm that ESG strategies in these sectors yield significant valuation benefits, precisely because these firms operate under high stakeholder dependency and ESG-related scrutiny.

While stakeholder theory explains the internal and relational mechanisms of ESG-driven value creation, signaling theory complements this perspective by focusing on the external communication dynamics between firms and capital markets. Rooted in the economics of information asymmetry, signaling theory [

20] suggests that firms use observable actions or disclosures to convey otherwise unobservable qualities to investors. In the ESG context, high-quality sustainability disclosures and ratings serve as credible signals of management quality, risk control, and future cash flow reliability.

This signaling function is particularly relevant in markets where non-financial performance is difficult to quantify or verify. Feldhütter and Pedersen [

3] find that financial institutions issuing ESG-linked instruments (such as green bonds or sustainability loans) send strong signals to the market about their commitment to responsible finance. These signals are often rewarded through higher investor demand and favorable capital terms. Likewise, Berg, Heeb, and Kölbel [

16] demonstrate that ESG rating changes prompt immediate market reactions: downgrades are punished by sell-offs, while upgrades lead to more measured but positive valuation adjustments. This behavior illustrates how ESG ratings operate as signals of firm quality that investors actively interpret and act upon.

Moreover, the effectiveness of ESG as a signal is shaped by its perceived credibility. Studies focusing on emerging markets, such as Huang and Zhou [

10], show that the transparency of ESG disclosures—rather than the raw score alone—plays a critical role in attracting investor interest. This aligns with signaling theory’s emphasis on the costliness and authenticity of signals: credible ESG information, especially when third-party verified or mandated by regulation, is more likely to influence valuation than superficial or boilerplate disclosures.

In summary, the observed ESG–market capitalization relationship aligns well with the theoretical predictions of both stakeholder and signaling theory. Stakeholder theory explains how ESG strategies improve firm value by strengthening stakeholder relationships and long-term performance capacity. Signaling theory highlights how ESG disclosures reduce information asymmetry and provide investors with meaningful indicators of firm quality [

26]. Together, these frameworks offer a robust theoretical foundation for interpreting why ESG performance, particularly when credible and context-specific, contributes positively to firm valuation in diverse market conditions.

4.2. ESG as a Resilience Factor in Downturns

An increasingly prominent theme in the literature on sustainable finance is the proposition that ESG performance enhances a firm’s resilience during economic downturns. This resilience is not merely symbolic or reputational—it reflects material advantages such as improved risk management, stakeholder loyalty, and operational adaptability that help firms weather systemic shocks more effectively than their lower-ESG counterparts. The COVID-19 pandemic provided a real-world stress test that has amplified the relevance of ESG as a protective mechanism under crisis conditions.

Multiple studies in the review confirm that firms with strong ESG credentials outperformed their peers during the COVID-19 downturn, both in terms of stock price stability and liquidity. For example, Liu, Nemoto, and Lu [

12] examine Japanese companies and find that those with high ESG ratings experienced significantly lower stock volatility and narrower bid-ask spreads during the height of the crisis. These firms were also more liquid, suggesting that investors considered ESG as a proxy for stability when reallocating capital in uncertain conditions. This reinforces the idea that ESG is not simply a “nice-to-have” feature during economic booms but a strategic asset that contributes to risk mitigation and operational robustness when markets are under stress.

The resilience effect is further demonstrated in Vochenko et al. [

15], whose global sample shows that ESG leaders exhibited faster recovery in market capitalization following the initial COVID-19 shock. The study highlights that high-ESG firms were better able to maintain workforce continuity, adapt supply chains, and communicate transparently with investors—all actions that fostered trust and attracted capital during a period of elevated risk aversion. These findings align with the resource-based view of the firm, which posits that intangible assets like reputation, employee engagement, and governance quality can serve as competitive advantages, especially when conventional strategies are disrupted.

From a theoretical standpoint, this resilience can be explained through stakeholder theory, which emphasizes that firms managing for the long-term interests of diverse stakeholders are more likely to cultivate loyalty and support when conditions deteriorate [

19]. High-ESG firms are often those that invest in employee well-being, supplier partnerships, and community relations—investments that may appear costly during growth phases but yield dividends in terms of flexibility and support during downturns. For instance, firms with strong social policies were better positioned to implement remote work transitions and maintain labor productivity under pandemic constraints [

12].

Signaling theory also supports ESG’s role in resilience, as strong ESG disclosures during crises act as credible signals of managerial competence and preparedness. Berg, Heeb, and Kölbel [

16] show that during the COVID-19 period, ESG downgrades were met with immediate and significant negative stock reactions, while firms maintaining high ESG ratings experienced more muted losses. This asymmetric response suggests that investors view ESG strength as a buffer against risk, while ESG weakness is treated as a red flag, particularly when economic conditions deteriorate.

Additionally, the financial sector plays an amplifying role in reinforcing ESG-driven resilience. Moolkham [

17] reports that in the Thai market, banks were more willing to extend favorable credit terms to ESG-compliant firms during the crisis. This suggests that financial institutions, faced with tightening credit markets and higher default risk, used ESG scores as part of their risk assessment process. As a result, ESG-aligned firms enjoyed better financing conditions when liquidity was scarce, further strengthening their market position.

However, the resilience benefits of ESG are not universal. In emerging markets where ESG disclosures lack standardization or enforcement, the perceived credibility of ESG claims can limit their value during crises. Cho [

18] observes that in several developing countries, the market’s response to ESG during the pandemic was mixed, often reflecting skepticism toward the quality of sustainability data. This points to the importance of regulatory frameworks and third-party validation in maximizing ESG’s resilience benefits.

Overall, the empirical evidence strongly supports the view that ESG is a material risk factor that contributes to firm resilience during economic downturns. Whether through stronger stakeholder support, better risk governance, or favorable access to capital, ESG-performing firms have demonstrated superior performance when market conditions deteriorate. As global financial markets become increasingly volatile due to climate change, geopolitical tensions, and health crises, the strategic value of ESG as a resilience factor is likely to intensify.

4.3. The Gap Between ESG Disclosure and Real Sustainability Practices: Greenwashing Risks

Despite the growing emphasis on ESG performance as a determinant of firm valuation, a persistent concern across both academic and practitioner communities is the disconnect between disclosed ESG information and actual sustainability practices. This discrepancy—often referred to as greenwashing—represents a critical limitation to the credibility and effectiveness of ESG frameworks. It not only undermines the transparency and comparability of ESG ratings but also poses reputational and financial risks for firms and investors alike.

Greenwashing can be broadly defined as the practice of overstating or misrepresenting a firm’s environmental or social credentials, either through selective disclosure, vague sustainability claims, or symbolic compliance with ESG norms without substantial operational change. Berg, Koelbel, and Rigobon [

9] provide compelling evidence of this phenomenon, highlighting that ESG scores often reflect disclosure quantity rather than quality. Their comparative study of major ESG rating providers finds that firms with extensive but non-substantive sustainability reporting may score higher than those engaged in genuine but less publicized ESG initiatives. This creates a situation where form is rewarded over substance, distorting market signals and potentially misleading stakeholders.

Empirical studies have shown that market capitalization can temporarily benefit from enhanced ESG disclosures, even when these disclosures do not correspond to meaningful performance improvements. Yi and Yang [

6], for example, document that Chinese firms with high ESG visibility receive increased institutional investment, but the actual correlation between disclosed ESG actions and underlying operational change remains ambiguous. This suggests that investors, especially in markets with limited regulatory oversight, may rely on superficial ESG signals, inadvertently incentivizing greenwashing behavior.

The problem is particularly acute in emerging markets, where ESG disclosure standards are often fragmented, voluntary, or weakly enforced. Cho [

18] argues that in such contexts, ESG reporting may be adopted strategically to gain access to international capital or satisfy nominal compliance requirements, rather than to reflect a genuine commitment to sustainability. As a result, ESG scores may be inflated or manipulated, creating information asymmetry that erodes investor trust over time.

Even in developed markets, where ESG integration is more mature, regulatory loopholes and inconsistent auditing practices allow firms to promote green initiatives without aligning their core strategies or resource allocations with sustainability goals. Feldhütter and Pedersen [

3] note that some financial institutions issue ESG-linked bonds without materially changing their lending practices or portfolio structures. These instruments may attract ESG-conscious investors, but the underlying impact is often negligible—a pattern that has sparked increased regulatory scrutiny in the EU and the U.S.

This credibility gap between ESG disclosure and real sustainability action has several implications. First, it weakens the observed correlation between ESG scores and market capitalization, as inflated or non-informative scores dilute the financial materiality of true ESG performance. Vochenko et al. [

15] suggest that variations in the strength of ESG–valuation relationships across sectors and regions may partially stem from the degree to which ESG disclosures reflect genuine operational realities. Second, greenwashing introduces ethical and reputational risks, as firms that are later exposed for misleading ESG claims can face public backlash, regulatory penalties, and devaluation. Third, it undermines the development of evidence-based ESG investing, as researchers and asset managers must account for unreliable or biased data.

To address these challenges, several scholars advocate for standardized, audited, and third-party verified ESG disclosures. Friede, Busch, and Bassen [

1] argue that improved comparability and enforcement are essential to closing the gap between reported and actual sustainability performance. Moreover, they recommend shifting the focus from static ESG scores to impact-based and forward-looking metrics, such as carbon intensity reductions, diversity targets, or sustainable supply chain traceability.

In summary, while ESG disclosures play a central role in signaling sustainability performance, there is substantial evidence that greenwashing undermines the integrity of these signals, particularly when disclosure is not accompanied by genuine behavioral change. Bridging this gap is essential not only for ensuring the financial relevance of ESG ratings but also for aligning capital markets with the broader goals of corporate responsibility and long-term sustainability.

4.4. Implications for Investors: ESG as a Signal for Long-Term Value

The cumulative evidence reviewed in this study strongly suggests that Environmental, Social, and Governance (ESG) performance provides investors with a reliable signal of long-term firm value. Unlike traditional financial metrics that often capture short-term profitability or operational efficiency, ESG indicators reflect a company’s strategic orientation toward long-term risk management, stakeholder alignment, and sustainable growth. As such, ESG considerations are becoming increasingly integral to institutional investment strategies, particularly among long-horizon investors such as pension funds, sovereign wealth funds, and endowments.

From a theoretical standpoint, signaling theory provides the most direct framework for understanding the informational role of ESG. In markets characterized by information asymmetry, firms that invest in high-quality ESG practices—and transparently report them—are able to differentiate themselves from competitors with less credible or opaque sustainability strategies. These signals of ESG strength are interpreted by investors as proxies for lower non-diversifiable risk, stronger internal controls, and a forward-looking management culture. Berg, Heeb, and Kölbel [

16] confirm this perspective by showing that changes in ESG ratings—especially downgrades—trigger measurable reactions in firm valuation, implying that investors actively respond to ESG-related news as material information.

In this context, ESG does not merely reflect ethical or reputational factors but is increasingly used by investors as an input in assessing firm resilience, particularly under conditions of systemic stress or macroeconomic uncertainty. For instance, during the COVID-19 crisis, investors reallocated capital toward firms with robust ESG performance, viewing them as better positioned to navigate supply chain disruptions, labor instability, and regulatory scrutiny. Liu, Nemoto, and Lu [

12] demonstrate that firms with higher ESG scores exhibited lower stock price volatility and tighter liquidity spreads, both of which are key indicators of investor confidence in a firm’s long-term stability.

Moreover, the predictive power of ESG becomes particularly salient in the context of climate-related and social risks, which are increasingly priced into financial markets. Investors are recognizing that firms with poor environmental records face heightened regulatory, reputational, and litigation risks, while those with weak governance structures are more vulnerable to fraud, inefficiency, or misalignment with shareholder interests. Friede, Busch, and Bassen [

1], in their meta-analysis of over 2,000 empirical studies, conclude that the majority show a positive relationship between ESG performance and financial returns, particularly over long investment horizons.

From a portfolio construction perspective, ESG is also being employed as a tool for risk-adjusted asset allocation. Large asset managers such as BlackRock and Vanguard have integrated ESG criteria into their investment screening processes, arguing that sustainability risks have become financial risks. Feldhütter and Pedersen [

3] find that firms with high ESG scores benefit from lower cost of capital and greater investor demand, suggesting that capital markets reward perceived sustainability leadership. These dynamics are especially important for fixed-income investors, where downside protection and default risk are core concerns.

Importantly, the credibility of ESG as a signal depends heavily on the quality and transparency of disclosure. Investors are increasingly wary of greenwashing and have begun to rely not only on ESG scores from rating agencies, but also on primary sustainability reports, third-party audits, and regulatory disclosures. Huang and Zhou [

10] emphasize that ESG transparency, rather than the score itself, plays a more decisive role in driving investor confidence in emerging markets. This indicates a shift toward data-driven ESG integration, where investors scrutinize the underlying metrics and methodologies rather than accepting ratings at face value.

The implications for investors are thus twofold. First, ESG performance offers material, decision-relevant information about a firm’s strategic orientation, risk exposure, and stakeholder management, all of which contribute to long-term valuation. Second, the integration of ESG factors into investment decisions is no longer peripheral but increasingly mainstream, as empirical evidence accumulates in support of its financial materiality. As regulatory frameworks evolve (e.g., EU Sustainable Finance Disclosure Regulation), the investment community will likely face increasing pressure to demonstrate how ESG factors are embedded in risk-return assessments and portfolio strategies.

In conclusion, the reviewed literature provides strong support for the idea that ESG functions as a forward-looking signal of firm quality and resilience, enabling investors to better align their capital with long-term value creation. Far from being a niche or values-based consideration, ESG is becoming a core component of modern investment strategy, particularly as financial markets adapt to the growing importance of sustainability-related risks and opportunities.

4.5. Implications for Firms: ESG Integration and Valuation in Policy-Sensitive Industries

For corporate managers and executives, the findings of this review have important strategic implications: ESG integration is no longer peripheral but a potentially material determinant of firm valuation, especially in industries that are heavily regulated or exposed to public scrutiny. Companies operating in sectors such as energy, finance, utilities, and transportation face mounting expectations from investors, regulators, and civil society to demonstrate sustainable behavior—not only for ethical or reputational purposes, but as a condition for accessing capital, mitigating risk, and maintaining long-term competitiveness.

The literature reviewed provides robust evidence that ESG performance positively correlates with market capitalization, particularly when ESG factors are embedded into core business operations and strategic decision-making. Vochenko et al. [

15] find that ESG leadership contributes to higher firm value across global markets, but the relationship is especially strong in sectors with regulatory dependencies such as energy and finance. These industries are directly affected by climate regulation, emissions standards, labor practices, and governance codes, meaning that failure to comply—or to appear responsive—can result in penalties, litigation, or reputational loss.

In emerging economies, firms in policy-sensitive sectors face additional challenges due to evolving regulatory frameworks and uneven enforcement. Moolkham [

17] demonstrates that in Thailand’s energy and infrastructure sectors, firms with strong ESG disclosure and performance received preferential treatment in capital markets, including more favorable credit terms and equity valuation. This suggests that ESG acts not only as a compliance signal but as a differentiator, helping firms secure investor trust and policy alignment in complex regulatory environments.

Beyond compliance, ESG integration increasingly functions as a strategic asset that enables firms to respond to stakeholder expectations, anticipate regulatory trends, and innovate in ways that create long-term value. In the financial sector, Feldhütter and Pedersen [

3] show that ESG integration into capital structure decisions—such as issuing green bonds or aligning lending policies with sustainability criteria—can lower firms’ cost of capital and attract a broader investor base. For banks and insurers, ESG is becoming central to risk modeling and portfolio resilience, particularly under climate-related stress testing scenarios.

From a governance perspective, ESG integration can also serve as a mechanism for internal improvement, enhancing board oversight, risk management systems, and corporate culture. Berg, Heeb, and Kölbel [

16] find that firms receiving ESG rating upgrades were rewarded by the market, particularly when the upgrades followed genuine structural changes, such as board diversity reform or adoption of science-based emissions targets [

25]. These improvements were especially valued in industries where stakeholder activism and regulatory oversight are high, reinforcing the link between ESG substance and firm valuation.

However, the benefits of ESG integration are not automatic. Firms must be mindful of ESG credibility and authenticity, especially in sectors prone to greenwashing scrutiny. Inconsistent ESG reporting, lack of third-party verification, or misalignment between disclosed policies and operational practices can damage reputation and reverse valuation gains. Huang and Zhou [

10] emphasize that in China, ESG transparency—not just performance—is what truly affects investor decisions and capital market outcomes, particularly in regulated industries where information asymmetry is high.

Firms must also recognize that policy-sensitive industries are often the focus of targeted ESG regulation. For example, under the European Union’s Sustainable Finance Disclosure Regulation (SFDR) and forthcoming Corporate Sustainability Reporting Directive (CSRD), firms in energy, finance, and manufacturing will be required to disclose standardized, audited ESG metrics. These regulations not only enforce compliance but also raise the baseline expectations for ESG transparency and performance, increasing the valuation differential between leaders and laggards.

In sum, for firms—especially those in policy-sensitive industries—integrating ESG into corporate strategy is both a defensive necessity and a competitive opportunity. Firms that treat ESG as a compliance box-ticking exercise may miss the valuation benefits observed in their more proactive peers. By contrast, firms that align ESG with material risks and value creation strategies are more likely to enhance market capitalization, attract long-term investors, and build resilience in a rapidly evolving regulatory and market environment.

4.6. Implications for Policymakers: The Need for Standardized, Transparent ESG Metrics and Ratings

As ESG investing becomes increasingly mainstream, the absence of uniform, transparent, and reliable ESG standards presents a critical challenge not just for firms and investors, but also for policymakers. The findings of this review highlight the substantial divergence in ESG ratings across providers and the lack of consistent disclosure practices, which together undermine the effective allocation of capital to genuinely sustainable firms. Policymakers thus have a pivotal role to play in establishing clear regulatory frameworks and harmonized standards to improve the credibility, comparability, and utility of ESG information in financial markets.

The inconsistency of ESG ratings across agencies has emerged as a fundamental obstacle to ESG integration. Berg, Koelbel, and Rigobon [

9] show that correlations between ESG scores from major providers are often surprisingly low, partly due to differences in scope, weightings, and methodologies. As a result, firms may receive widely different ratings depending on the provider, even when their actual sustainability practices are stable. This variance reduces confidence among investors and encourages opportunistic disclosure or greenwashing, particularly in markets lacking oversight. Inconsistent ratings also limit the effectiveness of ESG-based policy instruments such as tax incentives, subsidies, or capital requirements.

To address these gaps, policymakers are increasingly being called upon to establish clear ESG disclosure mandates. The European Union has taken early leadership through initiatives such as the Sustainable Finance Disclosure Regulation (SFDR) and the Corporate Sustainability Reporting Directive (CSRD). These frameworks require asset managers and firms to report standardized ESG information using taxonomy-aligned indicators and third-party assurance. Huang and Zhou [

10] note that in jurisdictions with stronger disclosure requirements, such as the EU or select East Asian economies, ESG transparency is more likely to translate into capital market rewards. Regulatory consistency is therefore essential not only for market fairness but also for incentivizing genuine sustainability efforts.

The COVID-19 crisis reinforced the urgency of standardizing ESG disclosures. Liu, Nemoto, and Lu [

12] demonstrate that firms with high ESG scores fared better during the pandemic, but the strength of this relationship was conditional on data reliability and disclosure quality. In the absence of standardized metrics, many firms were able to appear resilient based on self-reported or non-comparable indicators. This highlights the risk that without regulatory intervention, ESG signals may mislead rather than inform, creating systemic vulnerabilities in both equity and debt markets.

Beyond disclosure, policymakers should also consider regulating the ESG rating industry itself, much like credit rating agencies. Friede, Busch, and Bassen [

1] argue that third-party ESG ratings exert substantial influence over investment decisions, yet often lack transparency in methodology or accountability mechanisms. This opacity can distort market perceptions and allow ratings to be gamed by firms with superior disclosure capacity rather than superior sustainability performance. Establishing oversight standards, methodological transparency requirements, and conflict-of-interest rules for ESG rating agencies would enhance trust and prevent manipulation.

At the international level, coordination is crucial. While some progress has been made—e.g., the International Sustainability Standards Board (ISSB) and the Task Force on Climate-related Financial Disclosures (TCFD)—much of the global ESG landscape remains fragmented and voluntary. Cho [

18] emphasizes that in emerging markets, ESG frameworks often lack both enforcement and interoperability, making it difficult for investors to compare firms across borders or to assess systemic risks. International collaboration is thus needed to create globally accepted ESG definitions, sectoral benchmarks, and disclosure templates, particularly for climate risk, labor rights, and governance practices.

In conclusion, the literature provides clear evidence that the effectiveness of ESG as a financial and policy tool depends heavily on the regulatory infrastructure that surrounds it. Without standardized and transparent metrics, ESG risks becoming a symbolic rather than substantive driver of sustainability. For ESG to fulfill its potential as a lever of capital market transformation, policymakers must move beyond voluntary guidelines toward mandatory, verifiable, and globally coordinated disclosure and rating regimes. This will not only enhance investor confidence and protect against greenwashing, but also enable ESG-aligned firms to be properly recognized and rewarded in financial markets.

5. Conclusions

This review has demonstrated that ESG investments exert measurable but context-dependent effects on firm market capitalization, confirming the growing body of empirical evidence that sustainability considerations are material to financial performance. Across the ten systematically selected studies, a general trend emerges: firms with stronger ESG performance tend to command higher market valuations, particularly when ESG integration is strategic, transparent, and verifiable. This association holds in both developed and emerging markets, though its magnitude and consistency vary depending on sectoral characteristics, regional regulatory environments, and the methodological choices of the underlying studies.

Several mechanisms underpin this relationship. From a theoretical standpoint, stakeholder theory explains how firms that invest in ESG build stronger stakeholder relations, reduce reputational and regulatory risks, and foster long-term resilience—qualities valued by investors. At the same time, signaling theory highlights that ESG disclosures can serve as credible indicators of management quality and risk governance, especially under information asymmetry. Empirical studies confirm these insights: Vochenko et al. [

15] and Liu et al. [

12] find that ESG strength correlates with higher valuation and lower volatility, particularly in regulated or crisis-prone contexts.

However, the review also finds that the impact of ESG on market capitalization is not uniform. It varies by industry, with greater effects in policy-sensitive sectors like energy and finance, where regulatory oversight and public scrutiny are heightened. Regional disparities are also evident: firms in jurisdictions with robust ESG regulations and enforcement mechanisms tend to benefit more from ESG integration, as illustrated by Huang and Zhou [

10]. Moreover, the quality and credibility of ESG disclosures critically shape investor response. Greenwashing or inconsistent reporting, as discussed by Berg, Koelbel, and Rigobon [

9], can weaken or even reverse the positive valuation effects of ESG.

Ultimately, the findings support the conclusion that ESG performance is financially relevant, but its impact is conditional on context-specific factors—including data quality, regulatory frameworks, industry norms, and market expectations. For firms, this implies that ESG should not be treated as a symbolic or generic compliance tool, but as a strategically aligned and operationally embedded element of value creation. For investors and policymakers, it emphasizes the need for rigorous ESG evaluation criteria and harmonized disclosure standards to ensure that ESG-related capital flows are based on reliable and comparable information.

As financial markets continue to evolve under the pressures of climate risk, social inequality, and governance challenges, ESG considerations are poised to become even more central to corporate valuation. Understanding and addressing the contextual factors that shape ESG impacts will be essential for advancing both market efficiency and sustainable development goals.

The growing body of evidence linking ESG performance with firm market capitalization offers encouraging insights, but it also exposes structural gaps in the current ESG ecosystem that require urgent attention. Drawing on findings from this review, three principal areas emerge where concerted action by researchers, regulators, and market actors is most needed: standardization of ESG rating methodologies, longitudinal research, and greater transparency and regulatory enforcement to prevent greenwashing.

One of the most pressing challenges is the lack of methodological consistency among ESG rating providers, which results in low inter-rater reliability and contradictory firm evaluations. Berg, Koelbel, and Rigobon [

9] demonstrate that ESG scores from leading agencies often diverge significantly due to differences in data sources, indicator selection, weighting schemes, and aggregation techniques. This “aggregate confusion” undermines the comparability and credibility of ESG data, distorts market signals, and opens the door for firms to selectively report favorable metrics.

Standardization would benefit all actors in the ESG value chain. For investors, it would improve confidence in ESG assessments and reduce due diligence costs. For firms, it would clarify disclosure expectations and prevent the need to tailor reports to multiple rating frameworks. For regulators, standardized ESG data would facilitate oversight and policy enforcement. International efforts—such as the International Sustainability Standards Board (ISSB) and the European Union’s CSRD—represent critical first steps, but global coordination remains limited. Calls for a harmonized, auditable ESG reporting framework, aligned with sector-specific materiality thresholds, are increasingly urgent.

While cross-sectional studies reveal important correlations between ESG performance and firm valuation, there is a lack of longitudinal research that traces the persistence and evolution of ESG effects over time. Many of the studies in this review, including those by Vochenko et al. [

15] and Liu et al. [

12], capture short- to medium-term impacts—such as resilience during COVID-19 or capital market reactions to ESG upgrades—but do not explore whether these effects sustain, amplify, or diminish across economic cycles.

Future studies should apply panel data, time-series models, and causal inference techniques to examine the durability of ESG advantages. Key questions include: Does the value premium associated with ESG grow as firms mature in their sustainability journey? Are ESG benefits temporary reputational boosts, or do they yield lasting improvements in capital access, risk management, and stakeholder trust? More nuanced, longitudinal analysis could help distinguish between symbolic and substantive ESG, and better inform both investor strategy and public policy.

The risk of greenwashing—the exaggeration or misrepresentation of ESG performance—remains a critical threat to the integrity of ESG investing [

21]. Several studies reviewed, including those by Huang and Zhou [

10] and Yi and Yang [

6], underscore the divergence between ESG disclosure and actual corporate behavior, especially in regions with weak enforcement or voluntary compliance regimes. Greenwashing distorts capital flows, rewards superficial disclosure over genuine impact, and erodes stakeholder trust.

To combat this, there is a clear call for enhanced transparency, third-party auditing, and regulatory oversight. Just as financial statements are subject to independent verification, ESG reports should adhere to auditable standards and be monitored for accuracy and completeness. Regulatory frameworks like the SFDR in the EU and the SEC’s proposed climate disclosure rules in the U.S. represent early moves in this direction, but enforcement capacity and international harmonization remain limited.

Moreover, regulators should consider penalties for misleading ESG claims, support for capacity-building in emerging markets, and incentives for firms to adopt impact-oriented metrics (e.g., GHG emissions reductions, workforce diversity ratios, board independence). Transparent labeling of ESG financial products—along with clear definitions of what constitutes sustainable investment—would also help mitigate risks to investors and improve accountability in ESG markets.