2.1. Modeling Spiral Motion

In this section, we introduce a model for generating spiral motion in two dimensions. We assume that an object moves on a circle with a constant velocity B. Simultaneously, the radius of the circle increases over time at a constant rate V. To derive the equation of motion for this object, we first compute its angular velocity as follows:

where R(t) represents the radius of the circle as a function of time:

The angular displacement of the object can be obtained by integrating the angular velocity with respect to time, given by:

Utilizing Equations (

2.2) and (

2.3), we derive the parametric form of the object’s equations of motion as follows:

The polar equation for the golden spiral is as follows [

42]:

where

is the golden ratio. To facilitate a clearer comparison with equations (

2.4) and (

2.5), and to enable more effective plotting, we express equation (

2.6) in its parametric form:

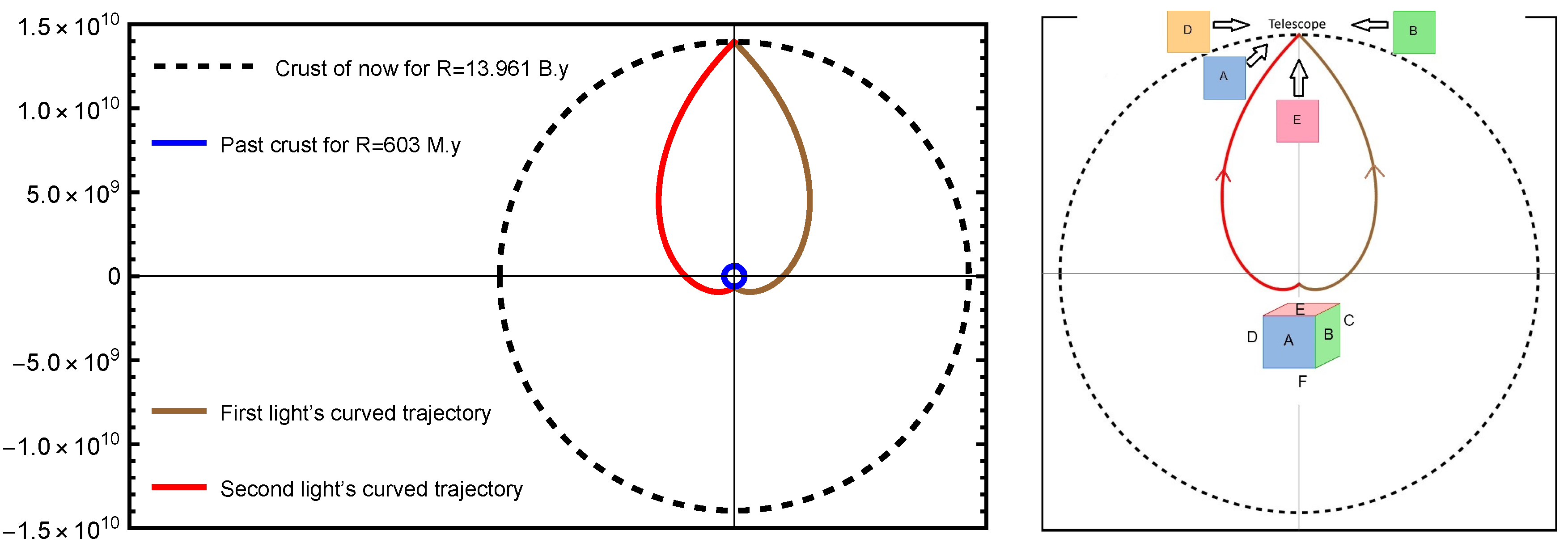

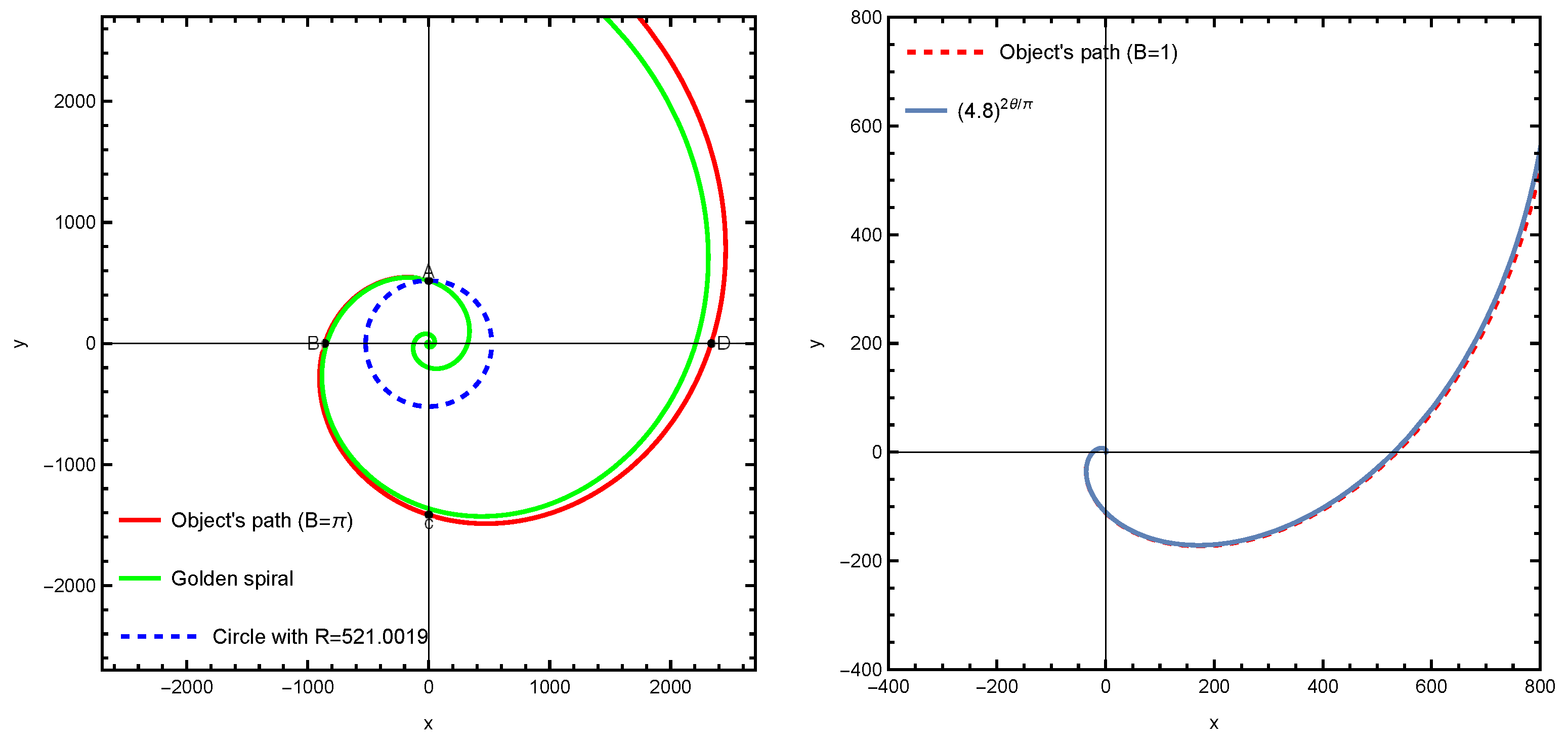

Now we present plots of the object’s equation of motion at a constant velocity V=1 across varying speeds of parameter B, compared to the golden spiral depicted in

Figure 1, as follows:

Figure 1 demonstrates that when the ratio of the velocity of B to V is equal to

, the resulting pattern closely approximates the Fibonacci golden spiral. Additionally, observing the diagrams from left to right in

Figure 1, it is evident that increasing the velocity of B results in a greater curvature in the object’s motion. The key condition to demonstrate that an equation of motion describes a golden spiral is as follows [

42]:

To verify condition (

2.9) for Equations (

2.4) and (

2.5) at

and

, we select the arbitrary points as illustrated in

Figure 2 (left). Also equation (

2.9) was analyzed for the case where B and V are both equal to one. In this scenario (B=V), the result of the equation (

2.9) is equal to 4.8. Consequently, for B=V=1, the equation of motion can be expressed in

Figure 2 (right):

The

Table 1 presents the specifications of the four selected points from

Figure 2 (left), which are located along the object’s path, along with an review of Condition (

2.9) as follows:

As shown in

Table 1, the ratios obtained from the points are close to the value of

. Therefore, in future calculations, we will employ Equations (

2.4) and (

2.5), using the velocity ratio

for calculation on the Golden Spiral.

In the following section, we will explore the mechanisms of time at both the quantum (small-scale) and cosmic (large-scale) levels.

2.2. The Mechanism of Time

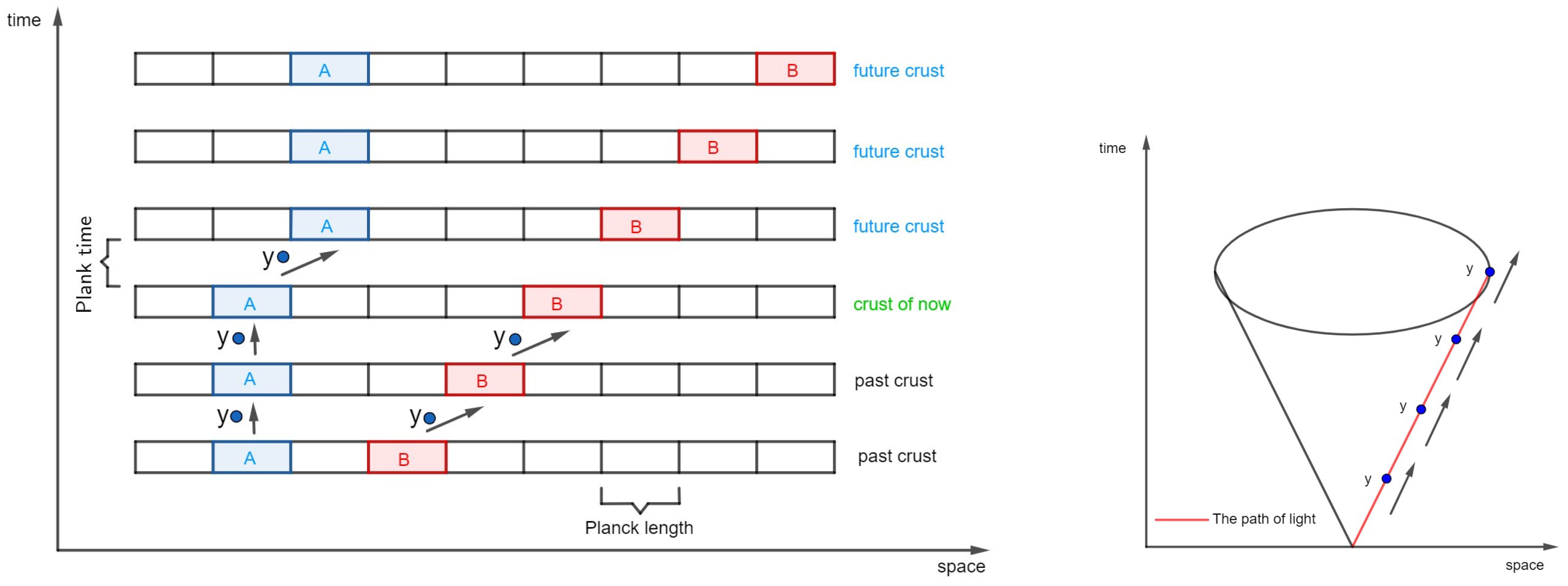

This section introduces a model for the nature of time. While the universe is typically described in three spatial dimensions, with time as the fourth perpendicular dimension, we simplify our discussion by considering space as one-dimensional for clarity.

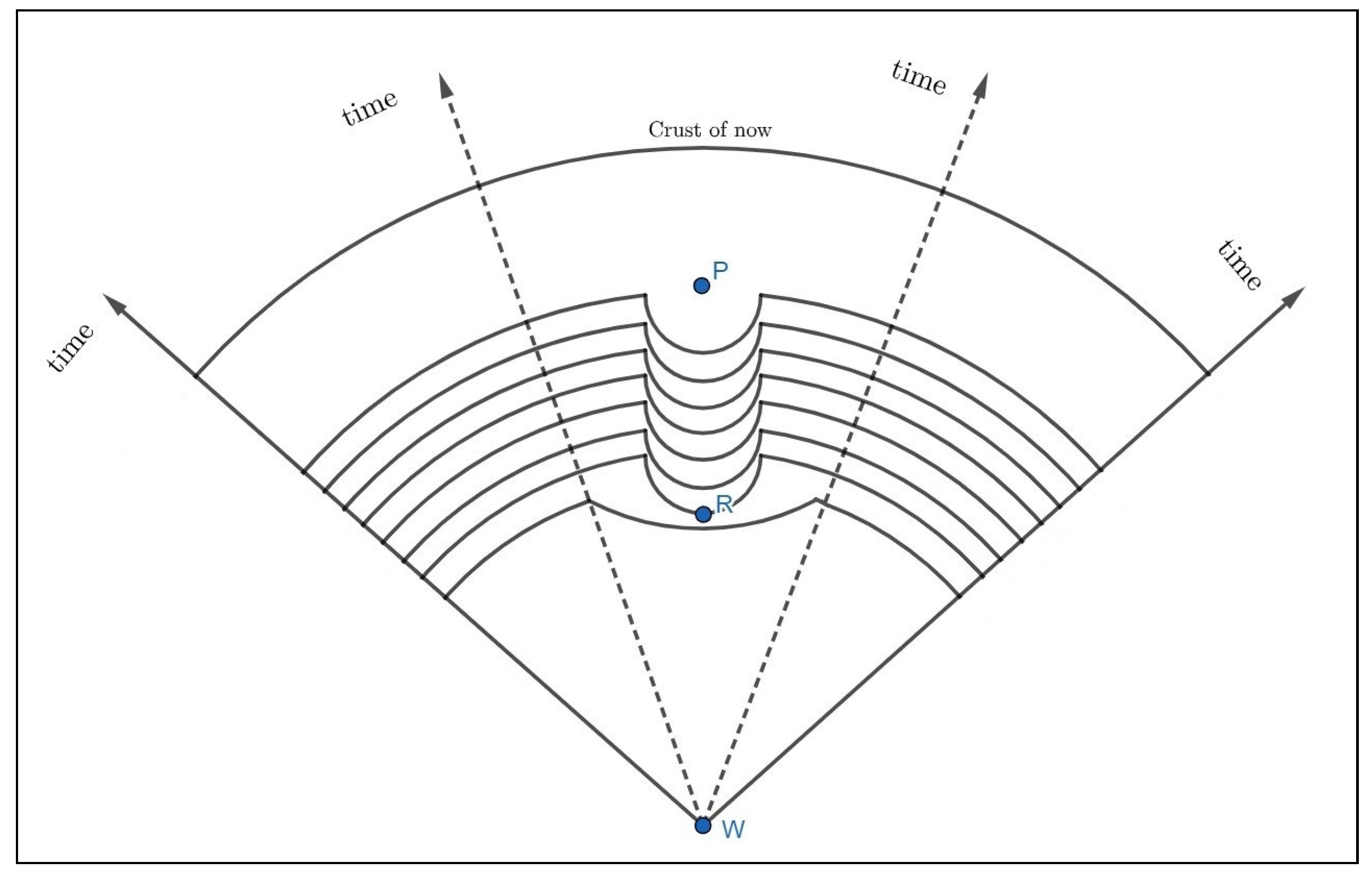

According to

Figure 3, consider two objects, A and B, moving through space. Object A moves at a slow velocity, while object B travels at the speed of light. Consequently, the smallest particles of object B cover a distance of one Planck length in each Planck time interval. In contrast, this is not the case for object A, whose particles move much more slowly.

As shown in

Figure 3, in this model, the crusts in the fourth dimension that are parallel to each other. The smallest volume in the universe is a cube with a side length of one Planck length. A quantum model for the nature of time is proposed, where the information of each cube at a given Planck time is transferred to the next crust via an intermediate particle, which we have named Y. When an object moves faster, its movement in the fourth dimension becomes more inclined because the information of each cube associated with that object is transferred to the neighboring cube in the subsequent crust. The oblique motion of light in the fourth dimension results from its extremely high speed. Consequently, the angle formed during this motion corresponds to the angle within Einstein’s light cone. Since no particle can travel faster than the speed of light, information from a cube in one crust cannot be transmitted to more distant cubes in the next crust. This limitation can be exemplified by the restricted interaction of the intermediate particle Y, similar to the asymptotic freedom observed in gluons. Just as a gluon transfers color charge between quarks, a hypothetical Y particle could transfer information between two parallel crust. This information can be considered the smallest unit of energy, with the arrangement of these fundamental units giving rise to various basic structures. It is possible that an object’s high kinetic energy can trigger the activation of oblique movement of the intermediate particle Y. The size of particle Y in

Figure 3 is hypothetical, and this particle functions as an intermediary between two parallel spaces, characterized by a metric distinct from that of conventional space.

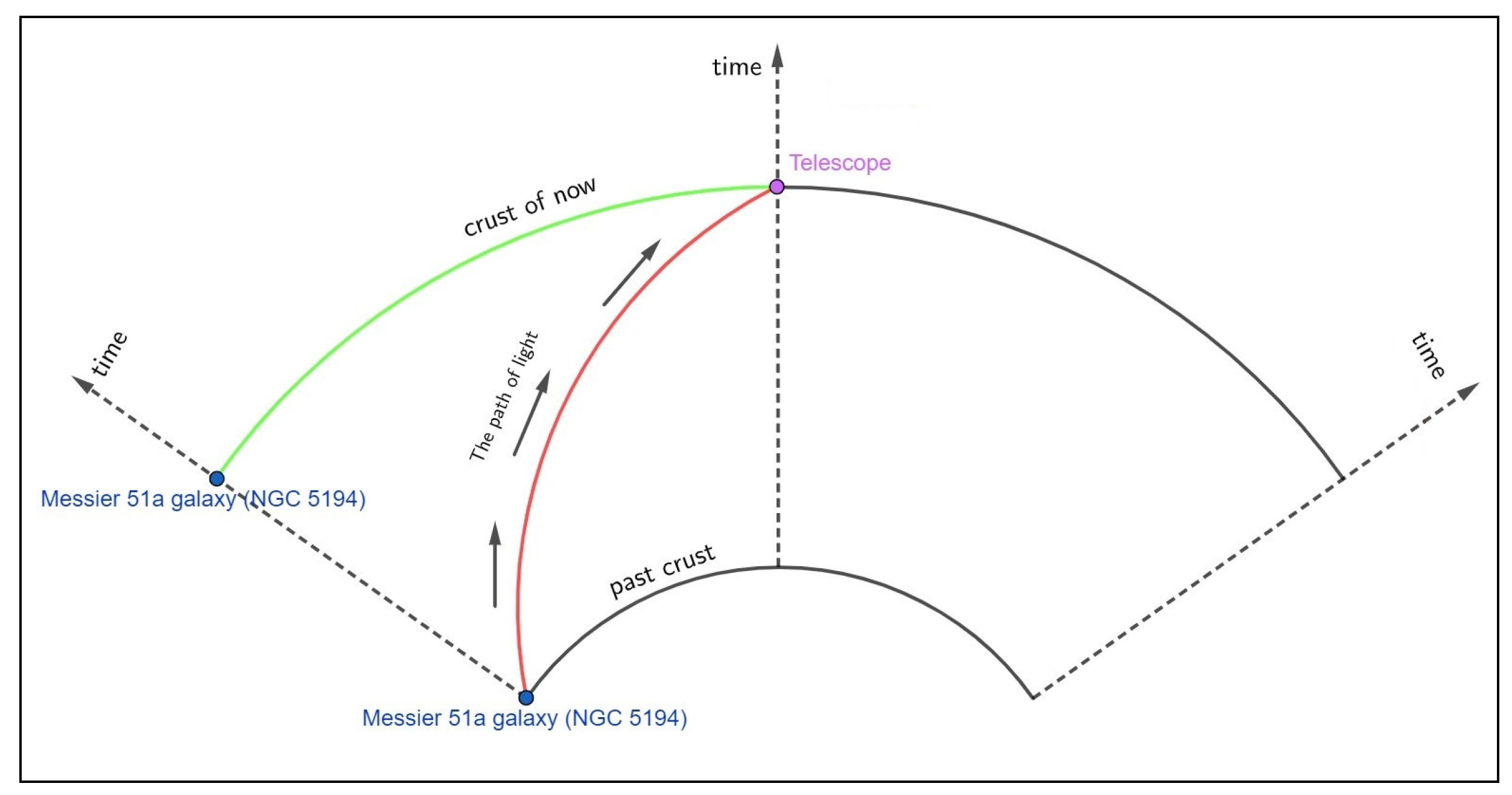

If the density of the universe exceeds from the critical density, then the universe is closed. In this case, the three-dimensional space of the universe can be thought of as a crust of four-dimensional sphere. Because

Figure 3 depicts a very small scale, this curvature is not readily apparent. However, in

Figure 4, which illustrates the universe on a larger scale, the curvature of this space crust is visible as part of the encompassing four-dimensional sphere.

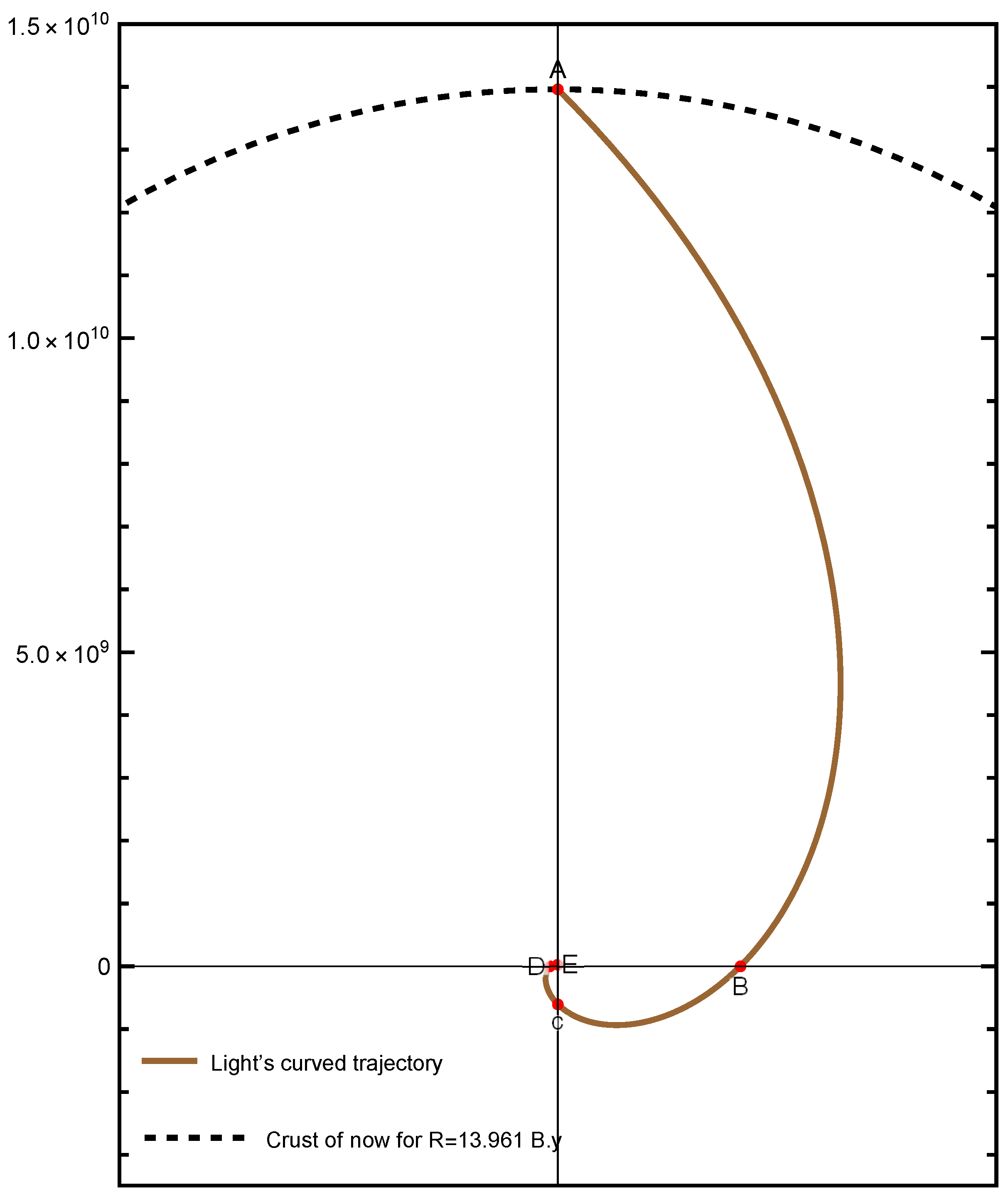

As illustrated in

Figure 4, the light traveling from a galaxy to Earth follows the curved path marked in red, rather than the green path.

Therefore, the oblique motion of light in the fourth dimension at the quantum scale results in a corresponding oblique motion of light at the cosmic scale.

2.4. Evaluating Light Curvature

In this section, the motion of light on the surface of a growing four-dimensional sphere is evaluated based on the equations obtained from the

Section 2.1. First, the current crust expansion rate is measured. So the arc length of a growing circle with radius

and central angle

is given by

. Therefore, the crust growth rate is calculated as follows:

therefore, the farther an object is from Earth, the greater its escape velocity, since it subtends a larger central angle. So if we equate this relationship with Hubble’s relationship, we can calculate the radius of the four-dimensional sphere. If we assume that an asteroid is located one light year from Earth, its escape velocity from Earth for

is given by the following equation:

Since the value of

is equal to one light year, we obtain the radius of the four-dimensional sphere by equating equations (

2.10) and (

2.11), as follows:

The radius of the universe’s four-dimensional sphere for different parameter changes are calculated, as illustrated in the table below:

In

Table 2, the

values are in (

). Also, the

pertains to the golden spiral described in

Section 2.1 and indicates the behavior of light traveling in the fourth dimension as modeled based on golden spiral. While the unit of R in

Table 2 is the light year, it represents the axis of the fourth dimension, which, as shown in

Figure 4, is perpendicular to space. Therefore, R effectively corresponds to a measure of time, with the unit of years. Therefore, the values in

Table 2 represent the age of the universe corresponding to various parameter changes. The green cell in the

Table 2 indicates the value closest to the measured age of the universe [

41].

There are points in the four-dimensional space-time sphere of the universe that have two properties: first, they have a phase difference with respect to the Earth equal to integer multiples of

, and second, if light emerges from the points of this spatial crust, it reaches Earth in current crust according to the path of the light spiral. To simplify notation, I have named these points "mirror points". For this reason, these points are named ’mirror points,’ because when a person stands between two mirrors, he can see both front and behind of himself simultaneously. In

Figure 6, we depict the position of the first mirror point relative to Earth, based on calculations performed with Mathematica.

In

Figure 6 (left), two light rays originating from a celestial body in the ancient crust (blue) are illustrated. The age of this crust is about 603 million years, determined from the universe’s age, which is indicated in green in

Table 2. In fact, a powerful space telescope capable of zooming this far could capture images of the celestial object from two different perspectives: one from the front and another from the behind of the celestial object.

In

Figure 6 (right), we have placed a hypothetical cube at a mirror point, on each face of this cube, the letters A, B, C, D, E and F are written. If a telescope in Earth’s orbit observes such a distance, depending on the telescope orientation position, it will see a different letter from this cube. In other words, by rotating the telescope around itself, it can see the image of the rotation of the cube.

Figure 6.

The position of the first mirror point relative to Earth within the four-dimensional sphere of the universe.

Figure 6.

The position of the first mirror point relative to Earth within the four-dimensional sphere of the universe.

Now we want to find the number of rotation of light within the four-dimensional sphere of the universe that it has traveled to reach us from one year after the Big Bang to the present.

In

Figure 7, points C and E are mirror points, while point A has a phase difference of

relative to point E. When zooming in graph, you’ll notice that the same shape is drawn inward from E point, creating a repeating pattern to inner. Using the plotting tool in Mathematica, The R ratios were calculated for the points in the

Figure 7 until the

approached 1. The corresponding values of these ratios are determined as follows:

The number of

cycles observed with the drawing tool in Mathematica ranged from 3 to 4 cycles. However, to precisely determine its value, we apply Equation (

2.13) as follows:

If we consider

to represent one year after the Big Bang, then the number of cycles for

become

=(3.722). Since the number of mirror points is twice the number of rotations (excluding point A itself), the total number of mirror points at these parameter values is 7.

In the following section, we determine the number of mirror points and their respective locations for various parameter values within the model.