1. Introduction

Hamstring strain injuries are among the most common non-contact musculoskeletal injuries in football, with high recurrence rates and significant performance implications, particularly during return-to-play phases [

1]. In university-level athletes, such injuries often occur during high-velocity sprinting and rapid acceleration or deceleration, compromising both short-term match readiness and long-term athletic development [

2]. Despite widespread adoption of conventional rehabilitation protocols, residual strength deficits and neuromuscular asymmetries frequently persist, increasing the risk of reinjury and delaying full athletic recovery [

3].

Recent evidence highlights the role of eccentric training in targeting these deficits. Eccentric exercises, particularly those involving the hamstring muscle group, have been shown to elicit favorable adaptations in muscle-tendon unit architecture[

4], improve force production during the terminal swing phase of gait, and enhance neuromuscular coordination [

5]. However, the practical application and sport-specific efficacy of eccentric interventions in post-injury rehabilitation contexts, especially among student-athlete populations, remain insufficiently explored [

6,

7,

8,

9].

Modern football science underscores the importance of evidence-based interventions to enhance performance and reduce injury risk, particularly given the sport’s high-intensity, multidirectional movement patterns and frequent physical contact. As athletic performance in football is shaped by a complex interaction of physical conditioning, neuromuscular control, and sport-specific demands, targeted assessment and individualized training protocols are essential for optimizing player outcomes and minimizing long-term musculoskeletal strain [

10,

11,

12,

13,

14].

This study investigates the effects of a six-week eccentric hamstring training protocol integrated into a standard rehabilitation program in university-level football players from the CSU ASE Football Team, aged 20 to 23 years. Specifically, we aimed to determine whether this intervention could improve sprint performance, isokinetic strength, and neuromuscular activation patterns as assessed through surface electromyography (sEMG). We hypothesized that the inclusion of eccentric loading would lead to superior improvements in these performance and recovery metrics compared to standard rehabilitation alone.

1.1. Literature Review

Hamstring injuries are among the most prevalent musculoskeletal problems encountered in team sports, particularly football, often resulting in extended periods of athlete downtime and significant implications for performance. The recurrence rate of these injuries underscores the complexity of recovery and rehabilitation processes [

15,

16]. High-speed running, rapid acceleration, and deceleration have been identified as primary mechanisms of hamstring injury occurrence, highlighting the need for targeted intervention programs focused specifically on these biomechanical demands [

17,

18].

Recent research advocates for the integration of eccentric strength training as a critical component in rehabilitation programs due to its ability to significantly enhance muscle strength, resilience, and reduce injury recurrence rates [

19]. Eccentric muscle actions are characterized by muscle elongation under tension, which has been demonstrated to provoke distinct physiological adaptations including increased fascicle length, improved neuromuscular control, and enhanced force-generating capabilities [

20,

21,

22].

Among eccentric training modalities, Nordic hamstring exercises have emerged as one of the most effective interventions, supported by extensive evidence highlighting their efficacy in increasing hamstring strength, improving functional outcomes, and substantially lowering reinjury rates [

23,

24,

25]. The practicality and effectiveness of Nordic exercises make them particularly appealing for integration within team-based training contexts, especially considering their simplicity, low cost, and high compliance rate among athletes [

26,

27,

28,

29].

Complementing these findings, tempo-based eccentric training, characterized by controlled movement velocities, has been shown to enhance muscular control and proprioceptive abilities, crucial for dynamic stabilization during high-speed movements typical of competitive football [

30,

31,

32,

33]. Such controlled exercises are beneficial in reconditioning the neuromuscular system, enhancing the athlete’s capacity to absorb and control eccentric loads, critical for injury prevention and optimized performance [

34,

35].

Biomechanical assessments, including sprint performance, isokinetic dynamometry, and electromyographic (EMG) analyses, have become integral components of monitoring rehabilitation progress and evaluating the efficacy of intervention programs [

36,

37]. Specifically, sprinting speed is directly correlated with athletic success in team sports, while isokinetic strength testing provides reliable measures of muscle strength recovery and neuromuscular readiness [

38,

39,

40].

Surface EMG has proven particularly informative for assessing neuromuscular adaptations, providing direct insights into muscle activation patterns, fatigue resistance, and inter-limb coordination. Such information is vital in ensuring symmetrical muscle function and minimizing asymmetries often associated with increased injury risk [

41,

42].

Research underscores the importance of individualized rehabilitation approaches that consider athlete-specific factors, including injury history, muscle architecture, and baseline neuromuscular function, to optimize recovery outcomes [

43,

44]. Individualized protocols not only address specific deficits but also accommodate the progressive adaptation needed to safely return athletes to competitive readiness [

45,

46].

Emerging literature emphasizes the importance of holistic approaches, integrating psychological and physiological components in the rehabilitation process. Psychological readiness, characterized by confidence in performance and reduced injury anxiety, has been linked directly with successful return-to-play outcomes and lowered recurrence rates [

47,

48]. Thus, comprehensive rehabilitation programs that concurrently address physical and psychological dimensions are increasingly advocated [

49,

50].

The collective evidence highlights the critical role eccentric training plays not only in recovery from hamstring injuries but also in proactive injury prevention strategies. When effectively integrated into routine training, eccentric exercises facilitate sustained athletic performance improvements, enhanced injury resilience, and reduced downtime [

51].

Considering the multifaceted nature of hamstring injuries, continued investigation into optimized training protocols, precise assessment techniques, and comprehensive rehabilitation strategies remains essential. Future research directions should particularly emphasize long-term follow-up studies, cross-sport applicability, and deeper insights into the neuromechanical mechanisms underpinning successful hamstring injury rehabilitation and prevention.

2. Methods

To systematically address the research objectives, a rigorous methodological framework was implemented, designed according to contemporary best-practice standards in sport and rehabilitation research. Recognizing that hamstring injuries represent complex and multifaceted clinical challenges, the methodological approach integrated careful participant selection, controlled experimental conditions, and sophisticated biomechanical and physiological assessments.

A core consideration underpinning the design was ensuring the internal validity of the study, minimizing potential biases, and clearly distinguishing intervention effects from natural recovery processes. Consequently, participants were selected based on strict inclusion and exclusion criteria, randomization was carefully implemented, and testing protocols were standardized, reproducible, and directly aligned with relevant functional tasks.

Furthermore, given the importance of precise quantification in evaluating training interventions, the methods employed advanced instrumentation, including isokinetic dynamometry for muscle strength measurement, high-precision timing systems for sprint assessments, and surface electromyography for detailed neuromuscular analysis. This comprehensive methodological approach thus provided a robust foundation for confidently interpreting the intervention outcomes and drawing clear, practically relevant conclusions.

2.1. Participants

Eighteen male student-athletes (age: 21.1 ± 1.0 years) from the CSU ASE Football Team participated in this study. All were active players at the university competition level and had a documented history of Grade II hamstring strain sustained within the previous 6–12 months. Inclusion criteria required full medical clearance, absence of pain at rest or during low-intensity activity, and no lower-limb injury in the last 3 months. Participants provided written informed consent, and the study protocol was approved by the university’s institutional ethics board.

As illustrated in

Table 1, the similarities across demographic and baseline characteristics ensure that observed intervention outcomes can be attributed confidently to the implemented training protocols rather than confounding demographic factors.

2.2. Study Design

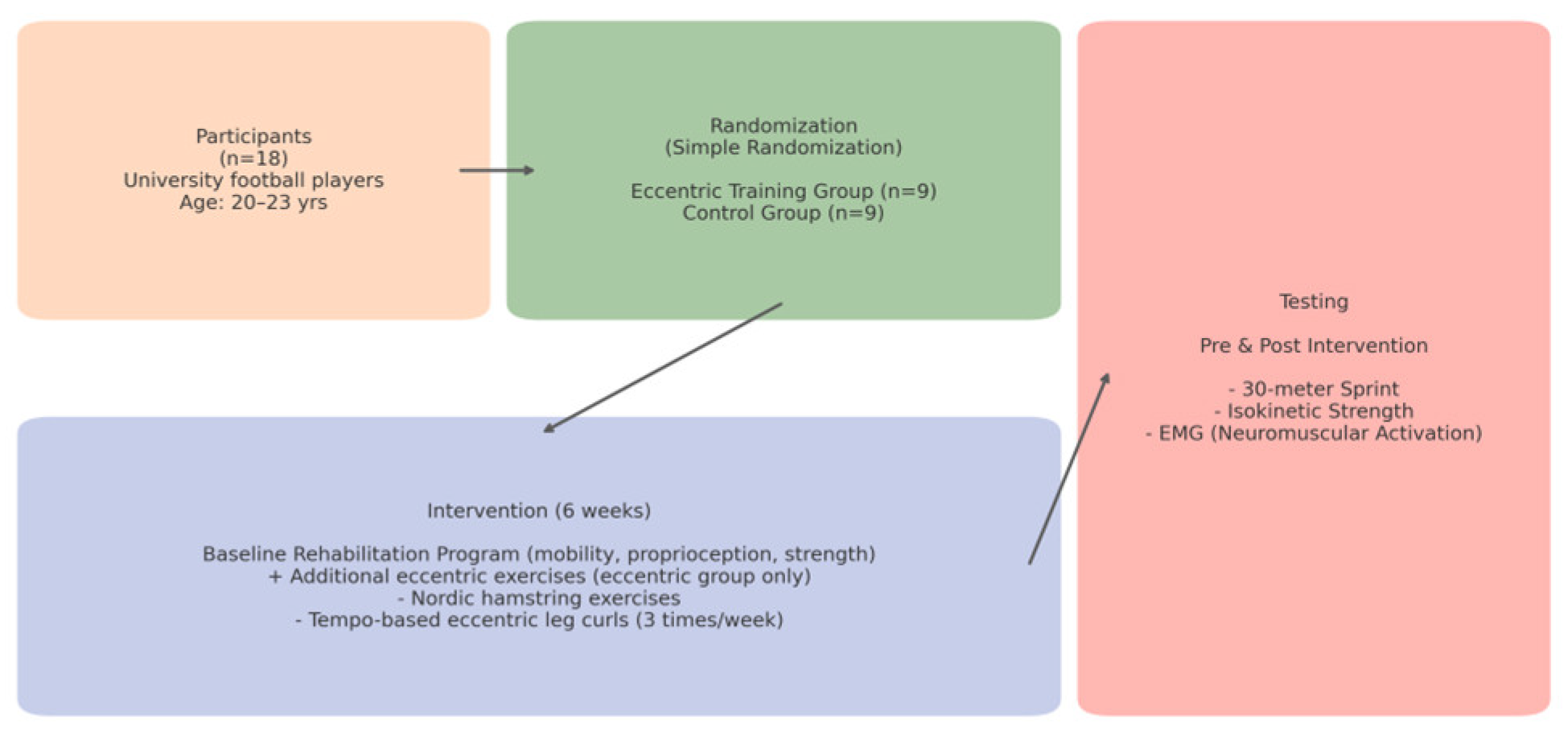

A randomized controlled trial was conducted over a 6-week intervention period. Participants were assigned to either an eccentric training group (n = 9) or a control group (n = 9) using simple randomization. Both groups followed the same baseline rehabilitation program, including mobility, proprioception, and strength exercises. The eccentric group performed additional Nordic hamstring exercises and tempo-based eccentric leg curls three times per week.

For clarity and ease of interpretation, the overall methodological approach of the randomized controlled trial is visually summarized in

Figure 1.

A visual summary of the study design involving 18 university football players (CSU ASE Football Team) randomly assigned to either an eccentric training group or a control group. Both groups followed a 6-week rehabilitation program, with the intervention group receiving additional eccentric exercises. Pre- and post-intervention testing assessed sprint performance, hamstring torque, and neuromuscular activation via surface EMG.

2.3. Testing Protocol

Assessments were conducted at baseline (Pre) and after 6 weeks (Post), under standardized conditions.

Sprint test: a 30-meter sprint was timed using dual-beam photocells (Brower Timing Systems, USA), with split times at 10m and 30m recorded. Each athlete completed three trials with 3-minute rests; the best trial was used for analysis.

Isokinetic strength: concentric and eccentric peak torque of the knee flexors was measured at 60°/s using an isokinetic dynamometer (Biodex System 4, USA). Bilateral testing was performed with standardized warm-up and positioning protocols.

Electromyography (EMG): surface EMG data were collected from the biceps femoris and semitendinosus muscles during maximal voluntary isometric contractions (MVIC). Skin preparation and electrode placement followed SENIAM guidelines. EMG signals were amplified, band-pass filtered (20–450 Hz), and normalized to peak MVIC amplitude.

Table 2.

Overview of testing protocols and measured variables.

Table 2.

Overview of testing protocols and measured variables.

| Test / Instrument |

Outcome Measure |

Measurement Details |

| 30m Sprint Test |

Sprint time (s) |

Measured at 10m and 30m

using dual-beam photocells |

| Isokinetic Dynamometer |

Hamstring peak torque (Nm) |

Concentric at 60°/s, bilateral testing with Biodex System |

| Surface EMG (sEMG) |

Peak muscle activation (%MVIC) |

Biceps femoris and semitendinosus, normalized to MVIC |

Co-contraction

Ratio |

Muscle coordination index |

Ratio of antagonist-to-agonist

activation during MVIC |

| Bilateral Symmetry Index |

Neuromuscular balance |

Comparison between dominant

and non-dominant limb |

Overview of testing protocols and outcome measures used to evaluate sprint performance, strength, and neuromuscular activation. Each test was administered at baseline and post-intervention under standardized conditions. Instruments included photocell timing systems, isokinetic dynamometry, and surface electromyography (sEMG), with all measures selected for their validity and relevance in sport rehabilitation contexts.

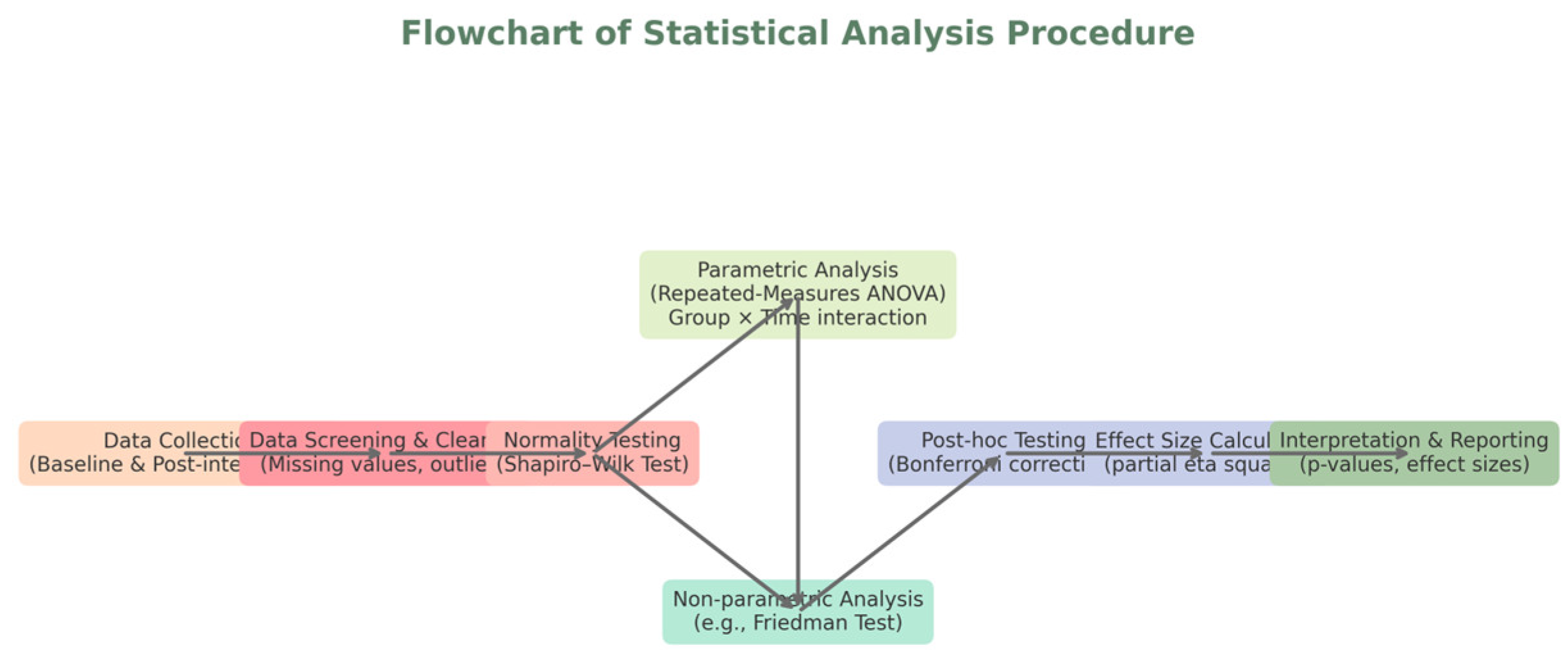

2.4. Statistical Analysis

All data were analyzed using SPSS v26.0 (IBM Corp., USA). Normality was confirmed using the Shapiro-Wilk test. A two-way repeated-measures ANOVA was conducted to examine the effects of group (eccentric vs. control) and time (pre vs. post) on performance and neuromuscular outcomes. Statistical significance was set at p < 0.05. Effect sizes (partial eta squared) were calculated and interpreted using standard thresholds.

To clearly illustrate the statistical procedures employed,

Figure 2 provides a visual flowchart outlining each critical step, from initial data screening to final interpretation.

The comprehensive analytical approach ensures methodological rigor, accuracy, and reliability in interpreting the intervention’s effectiveness. By systematically addressing potential statistical concerns, including data normality, selection of appropriate tests, and thorough post-hoc validation, the results derived provide robust evidence for informed decision-making in sport-specific rehabilitation contexts. Building upon this analytical rigor, the study integrated a targeted eccentric training intervention alongside standardized rehabilitation protocols to provide a clear comparative perspective on neuromuscular adaptations and performance enhancements.

Particular attention was given to rigorous participant selection and careful control of confounding factors, ensuring that observed effects could be confidently attributed to the eccentric loading regimen. Additionally, the sophisticated combination of biomechanical assessments - including timed sprint performance, isokinetic dynamometry, and surface electromyography - provided comprehensive insights into both functional performance and underlying physiological mechanisms.

Given the established significance of sprint ability and hamstring muscle function for athletic performance and injury prevention in football, the following results offer not only empirical validation of eccentric training protocols but also practical guidance for coaches, physiotherapists, and sports scientists seeking effective and evidence-based strategies to enhance athletic recovery and performance.

3. Results

The following section presents detailed results obtained from the 6-week randomized controlled trial, highlighting key performance outcomes relevant to university-level football athletes recovering from hamstring injuries. Specific attention is given to sprint performance, muscular strength, and neuromuscular coordination—critical determinants of athletic efficiency, injury resilience, and competitive success.

To facilitate clear interpretation, each measured outcome is first examined individually, beginning with sprint performance, as speed and acceleration capacity are widely recognized as pivotal for competitive advantage in football. Subsequent analyses detail muscular strength adaptations and neuromuscular activation patterns, collectively providing a comprehensive understanding of the physiological and functional impact of the eccentric hamstring training intervention.

The practical implications of these results extend beyond statistical significance, directly influencing training strategies, rehabilitation practices, and ultimately, performance optimization in sport-specific contexts.

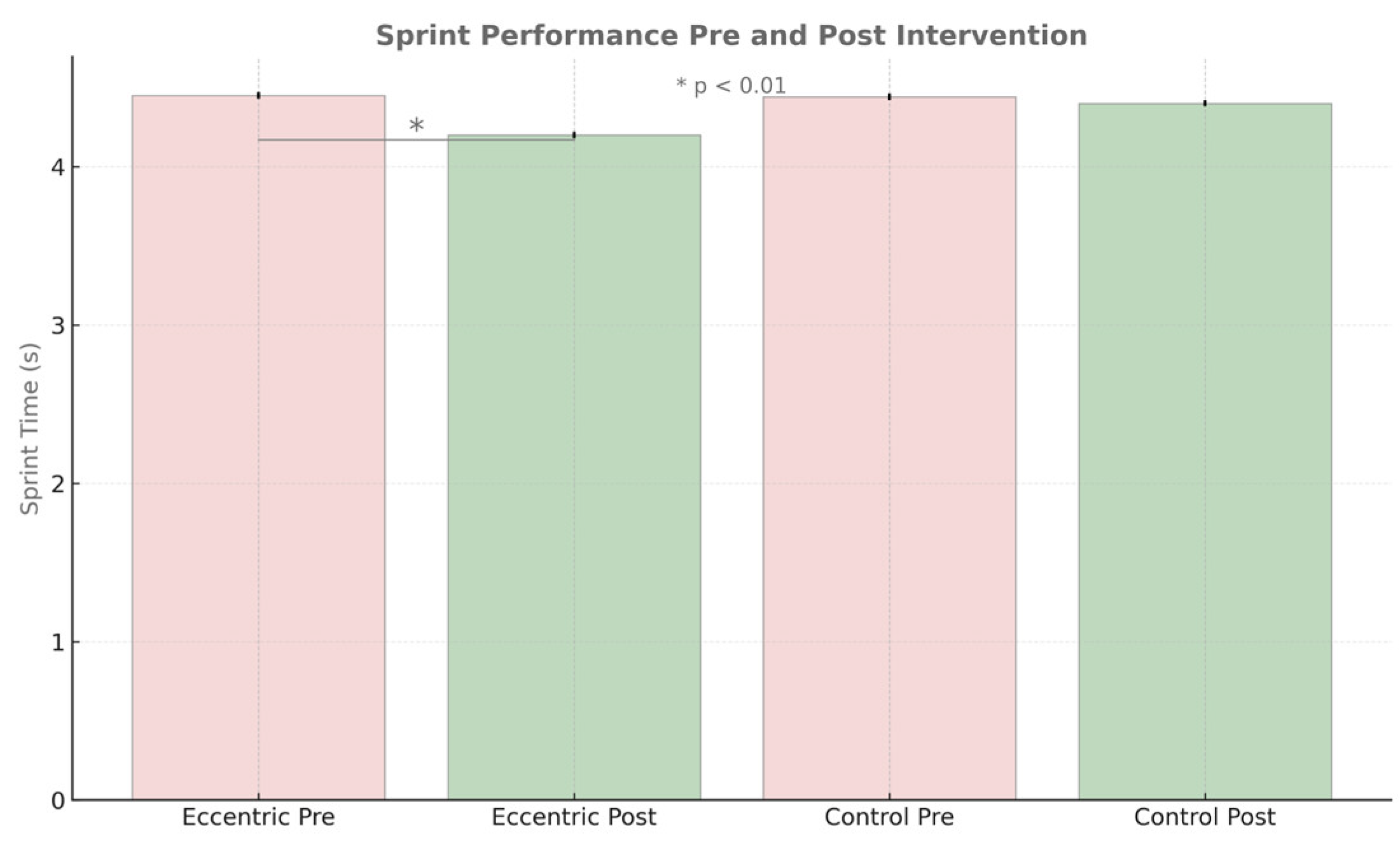

3.1. Sprint Performance

At baseline, no significant differences were observed between groups regarding 30-meter sprint times, indicating a well-balanced starting point. Following the 6-week intervention period, the eccentric training group achieved a statistically significant improvement in sprint performance, reducing their average sprint time from 4.45 ± 0.18 s to 4.20 ± 0.14 s (p < 0.01), representing an average performance improvement of 5.6%. Conversely, the control group displayed minimal and non-significant improvement (from 4.44 ± 0.17 s to 4.40 ± 0.19 s; p = 0.18), suggesting negligible impact from standard rehabilitation alone.

The meaningful improvement observed in the eccentric training group is noteworthy from both a statistical and practical perspective, given that even small enhancements in sprint times can substantially influence on-field performance outcomes, such as acceleration capacity, reaction efficiency, and overall match competitiveness. These findings underscore the potential of targeted eccentric hamstring training as a viable strategy for performance optimization and effective injury rehabilitation within the sport-specific context of university-level football.

Table 3 provides a detailed summary of sprint performance before and after the intervention, highlighting mean changes, statistical significance, 95% confidence intervals, and effect sizes. Notably, the eccentric training group demonstrated large and statistically significant improvements, whereas changes in the control group were small and not statistically significant.

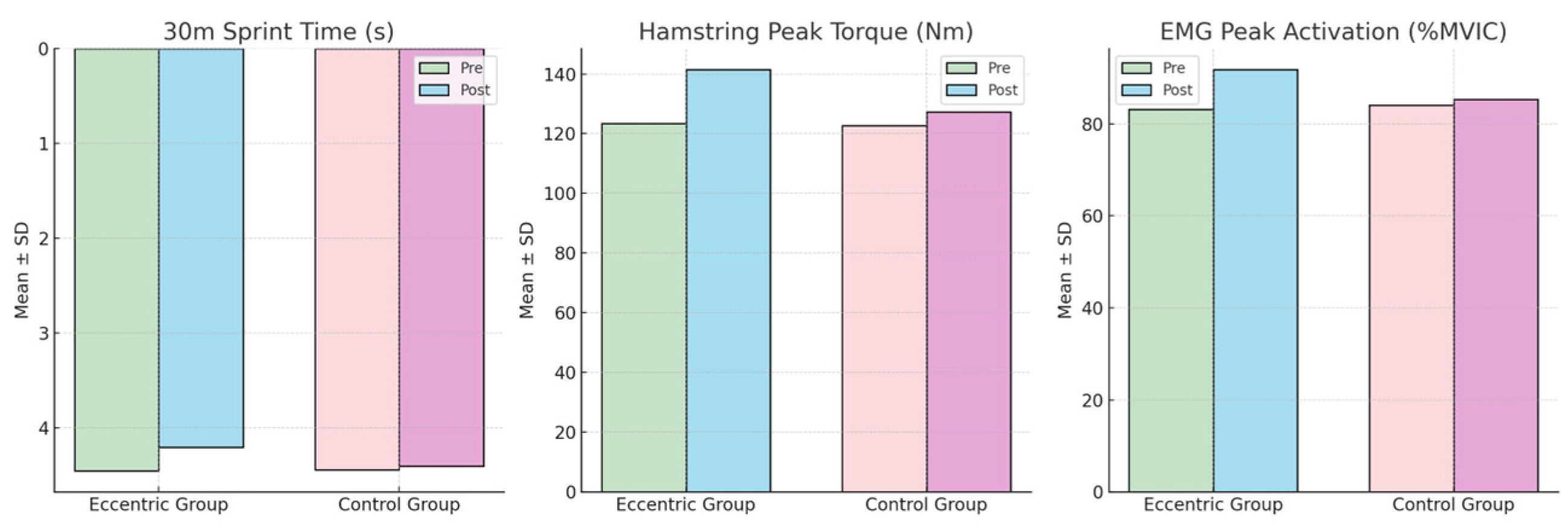

Figure 3 visually summarizes mean sprint performance changes, clearly highlighting the statistically significant improvement observed in the eccentric training group.

Collectively, these results underscore the clear practical value of integrating eccentric hamstring training into rehabilitation protocols, highlighting substantial gains not only in statistical terms but also in performance metrics directly relevant to competitive football.

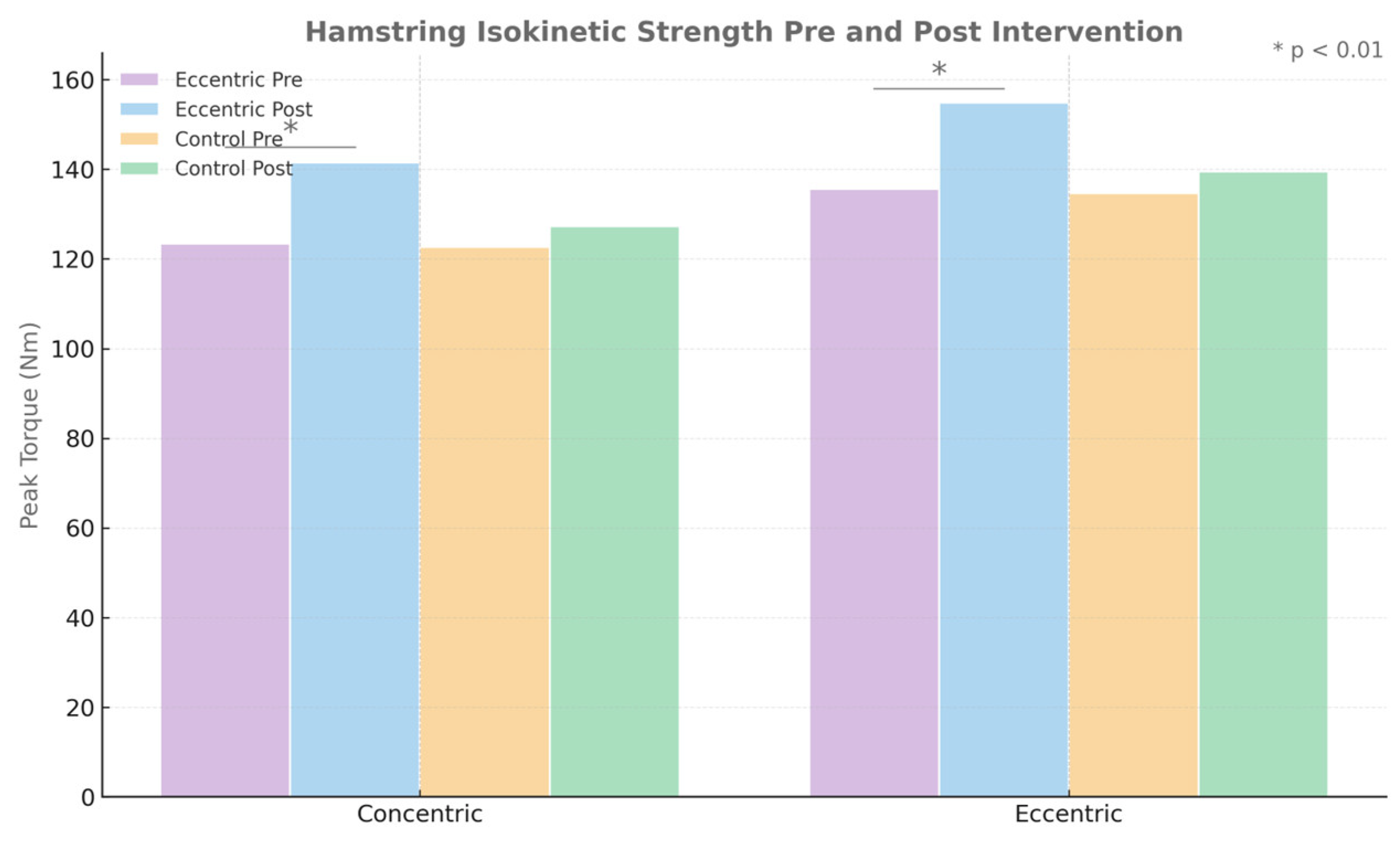

3.2. Isokinetic Strength

Baseline measurements revealed no significant differences between groups in terms of concentric and eccentric peak hamstring torque, suggesting comparable strength profiles prior to intervention. After the 6-week training period, significant strength gains were evident exclusively in the eccentric training group. Specifically, the mean concentric peak torque improved substantially from 123.4 ± 9.6 Nm at baseline to 141.5 ± 10.2 Nm post-intervention (p < 0.01), corresponding to a meaningful increase of approximately 14.7%. Similarly, eccentric peak torque exhibited comparable significant improvements, highlighting a clear enhancement of overall muscular capacity.

Detailed quantitative changes in concentric and eccentric hamstring peak torque for both groups are summarized in

Table 4, underscoring the significant strength improvements achieved specifically through eccentric training.

Figure 4 visually compares concentric and eccentric hamstring torque measurements before and after intervention, clearly highlighting the enhanced strength outcomes in the eccentric training group.

In contrast, the control group demonstrated limited and statistically non-significant increases (from 122.7 ± 11.3 Nm to 127.3 ± 10.8 Nm; p = 0.09), representing only modest natural recovery associated with standard rehabilitation practices. The evident disparity between groups emphasizes the targeted eccentric training’s efficacy in specifically developing hamstring muscle strength beyond baseline rehabilitation benefits.

These results are practically significant, as increased isokinetic hamstring strength has clear implications for injury prevention, athletic longevity, and performance optimization, particularly for sports characterized by repetitive high-speed movements and rapid directional changes, such as football.

3.3. EMG Activation

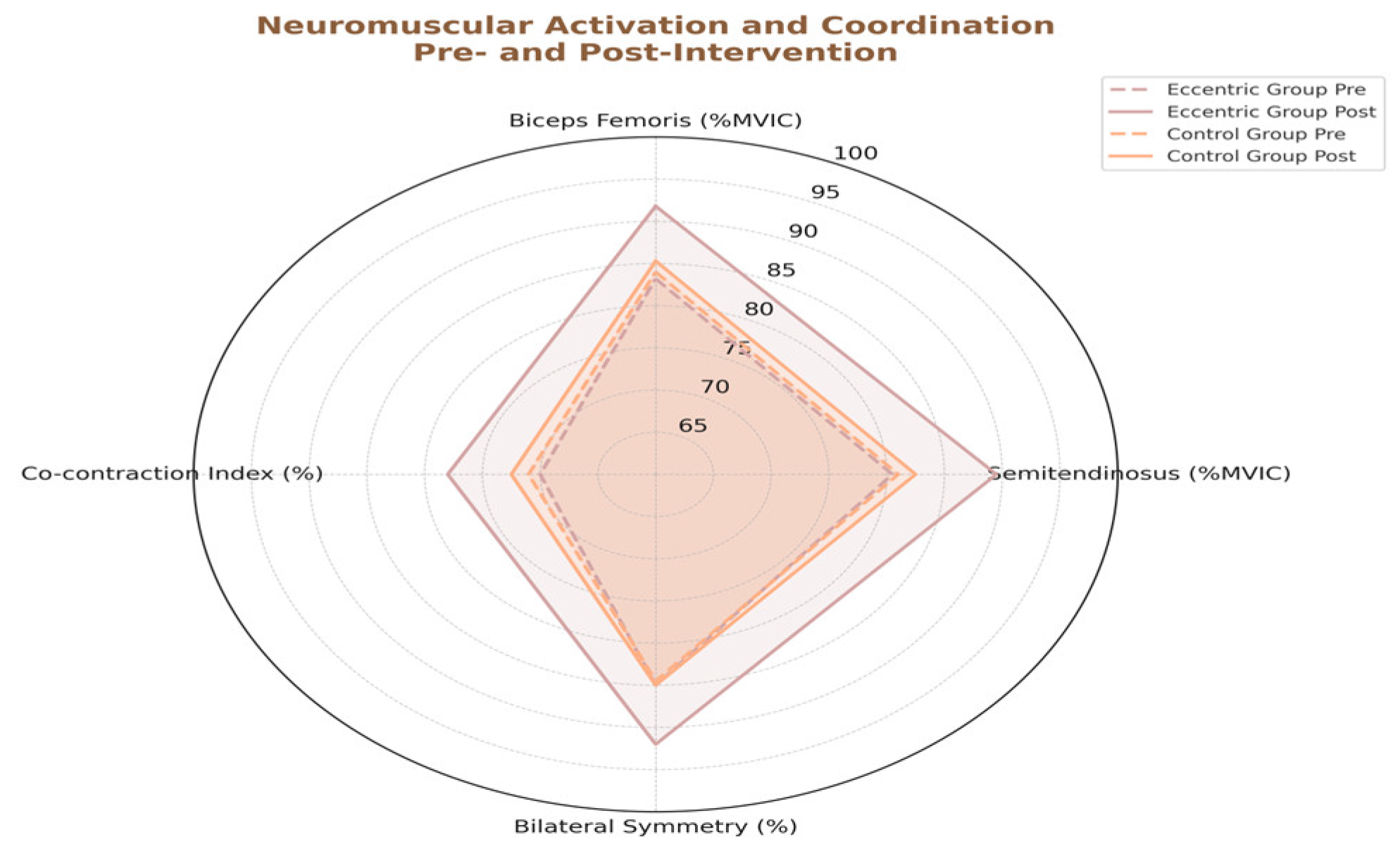

Surface EMG recordings revealed greater normalized peak activation of the biceps femoris and semitendinosus during maximal voluntary contractions in the eccentric group. Co-contraction index and bilateral symmetry ratios improved post-intervention, indicating enhanced neuromuscular coordination.

To highlight the differential effects of the intervention,

Table 5 presents the comparative results across timepoints for both groups.

Table 5 summaries the performance and neuromuscular outcomes before and after the 6-week intervention. Values are presented as mean ± standard deviation (SD). Improvements in sprint time, hamstring torque, and EMG peak activation were significant in the eccentric training group (

p < 0.01), while changes in the control group were not statistically significant. Percent change reflects relative improvement from baseline.

As illustrated in

Figure 5, the eccentric training group demonstrated marked improvements in sprint time, hamstring torque, and EMG activation following the 6-week intervention period, in contrast to minimal changes observed in the control group.

Mean values (± SD) for the eccentric training and control groups before and after the 6-week intervention: (A) 30-meter sprint time (lower values indicate better performance), (B) isokinetic peak torque of the hamstrings, and (C) peak EMG activation of the biceps femoris and semitendinosus muscles expressed as %MVIC. Significant improvements were observed in the eccentric group across all measures (p < 0.01), while the control group showed minimal changes.

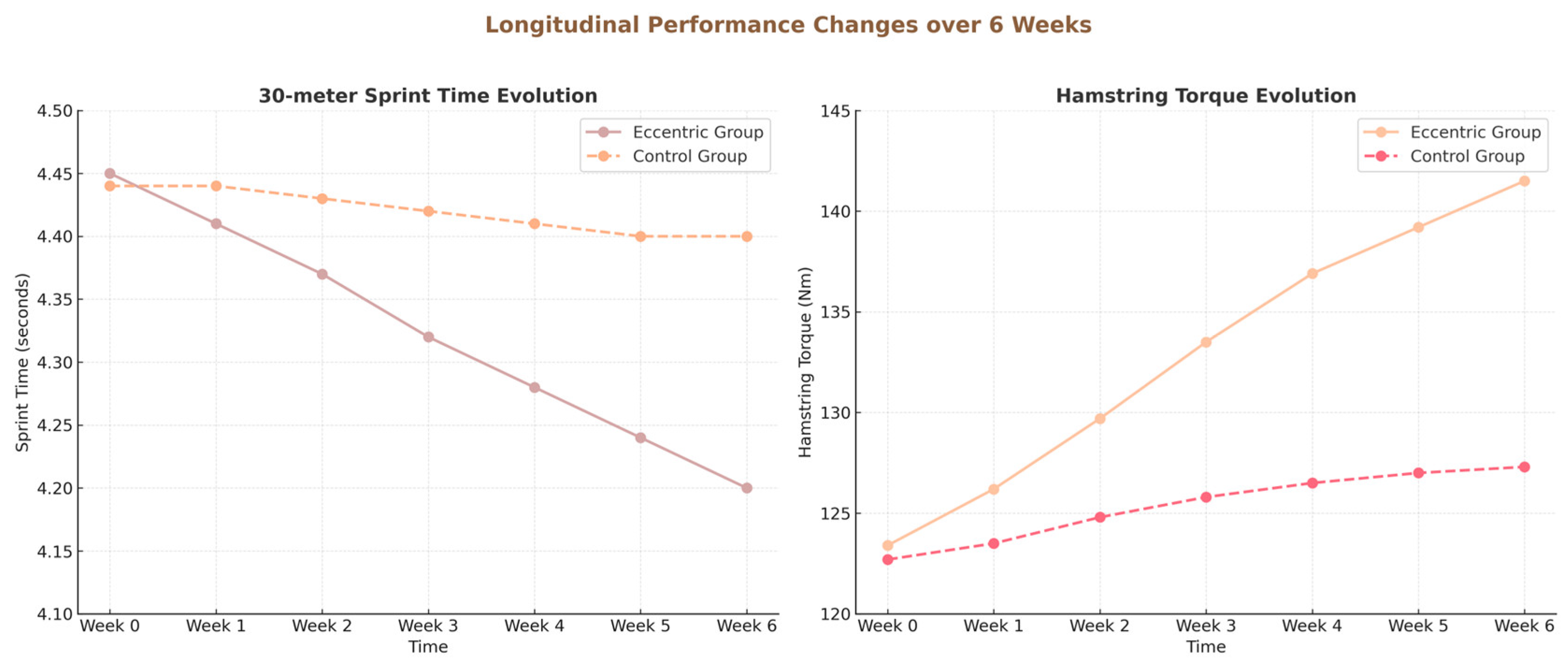

To further complement and extend the findings summarized in

Figure 5, a detailed week-by-week analysis of changes in sprint time and hamstring torque throughout the entire intervention period is provided in

Figure 6.

Collectively, the EMG results indicate that eccentric hamstring training not only enhances muscle activation but also promotes superior neuromuscular coordination and bilateral symmetry, key factors for injury prevention and performance enhancement. These neuromuscular adaptations, coupled with improvements in sprint performance and muscle strength, strongly support the incorporation of targeted eccentric exercises into rehabilitation protocols for university-level football athletes.

To visually illustrate the multidimensional neuromuscular adaptations following the intervention,

Figure 7 presents a radar plot comparing pre- and post-intervention EMG activation and coordination metrics.

Taken together, the longitudinal and multidimensional analyses provided in

Figure 3 and

Figure 4 emphasize the effectiveness of eccentric hamstring training in optimizing neuromuscular function, suggesting important practical implications for rehabilitation and injury prevention strategies discussed in the following section.

4. Discussion

This study examined the effects of a structured 6-week eccentric hamstring training program on sprint performance, isokinetic strength, and neuromuscular activation in university football players undergoing post-injury rehabilitation. The results demonstrated significant improvements across all measured outcomes for the eccentric training group compared to the control group, thus confirming our initial hypothesis.

The observed reduction in 30-meter sprint time aligns with existing evidence highlighting the crucial role of eccentric hamstring strength during the late swing phase of sprinting, a phase characterized by substantial hamstring loading. Enhanced eccentric strength likely facilitated improved force absorption and deceleration control, resulting in superior sprint efficiency. This finding aligns well with current rehabilitation literature advocating targeted eccentric exercises to optimize recovery and athletic performance.

Increased concentric and eccentric peak torque in the intervention group suggests considerable gains in muscle strength and functional capacity, essential components for athletes returning from injury. The noted improvements support existing research emphasizing the efficacy of eccentric-focused protocols, particularly Nordic hamstring exercises, for reducing reinjury risk by addressing persistent strength deficits.

Further support for the effectiveness of the intervention protocol was provided by EMG assessments, demonstrating increased muscle activation levels and improved bilateral coordination post-intervention. These neuromuscular adaptations imply a reorganization of motor control strategies and enhanced proprioceptive demand, possibly attributed to greater motor unit recruitment and improved neuromuscular efficiency resulting from the eccentric loading regimen.

Despite the robust findings, the present study has some limitations that warrant discussion. The relatively small sample size and short follow-up period limit the generalizability of the results. Future studies should include larger cohorts and longer follow-up durations to evaluate long-term outcomes, such as retention of performance improvements and reinjury rates. Additionally, while EMG analysis provided valuable insights into muscle activation patterns, future research could benefit from incorporating assessments of tendon stiffness and detailed muscle architecture adaptations.

Practical implications include advocating for routine integration of eccentric hamstring exercises into early rehabilitation phases, thus accelerating return-to-play readiness and enhancing functional neuromuscular control in football athletes. Strength coaches and physiotherapists are encouraged to adopt low-cost, simple-to-implement eccentric modalities, such as Nordic hamstring curls, within their team-based rehabilitation and injury prevention strategies.

5. Conclusion

This study provides robust evidence supporting the integration of eccentric hamstring training into standard rehabilitation programs for university-level football athletes recovering from hamstring injuries. Over the 6-week intervention, participants engaging in eccentric training displayed significant improvements in sprint performance, muscular strength, and neuromuscular coordination, resulting in enhanced readiness for return-to-play and reduced reinjury potential.

The positive outcomes endorse the use of eccentric exercises—particularly Nordic hamstring and tempo-based eccentric curls—as practical, effective, and economical strategies in sports rehabilitation contexts. Given their simplicity and athlete compliance, broader implementation across university sports settings is both feasible and recommended.

Future investigations should explore the long-term impact of eccentric training protocols, including sustained injury prevention benefits and retention of neuromuscular gains. Additionally, extending research to diverse athlete populations and varying competitive levels will help establish broader applicability and inform evidence-based guidelines across different sports disciplines.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, C.O.M.; methodology, D.C.M.; formal analysis, C.O.M.; investigation, D.C.M.; writing—original draft preparation, C.O.M.; writing—review and editing, D.C.M.; supervision, D.C.M. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted according to the guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Institutional Ethics Committee of [Your University/Institution] (approval number and date).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author. The data are not publicly available due to privacy reasons.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Mendiguchia, J., Alentorn-Geli, E., & Brughelli, M. (2020). Hamstring strain injuries: Are we heading in the right direction? British Journal of Sports Medicine, 54(6), 303-309.

- Manescu, C.O. (2010). Modelarea pregătirii în jocul de fotbal. Ed. ASE.

- van Dyk, N., Bahr, R., Whiteley, R., Tol, J. L., Kumar, B. D., Hamilton, B., ... & Witvrouw, E. (2019). Hamstring and quadriceps isokinetic strength deficits are weak risk factors for hamstring strain injuries: a 4-year cohort study. The American Journal of Sports Medicine, 47(4), 947-953.

- Bourne, M. N., Williams, M. D., Opar, D. A., Al Najjar, A., Kerr, G. K., & Shield, A. J. (2018). Impact of exercise selection on hamstring muscle activation. British Journal of Sports Medicine, 52(15), 1021-1028.

- Țifrea, C., Cristian, V., & Mănescu, D. (2015). Improving fitness through bodybuilding workouts. Social Sciences, 4(1), 177-182. [CrossRef]

- Presland, J. D., Timmins, R. G., Bourne, M. N., Williams, M. D., & Opar, D. A. (2018). The effect of Nordic hamstring exercise training volume on biceps femoris long head architectural adaptation. Scandinavian Journal of Medicine & Science in Sports, 28(7), 1775-1783.

- Al Attar, W. S. A., Soomro, N., Sinclair, P. J., Pappas, E., & Sanders, R. H. (2017). Effect of injury prevention programs that include the Nordic hamstring exercise on hamstring injury rates in soccer players: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Sports Medicine, 47(5), 907-916.

- Manescu, D.C. (2013). Fundamente teoretice ale activității fizice. Editura ASE, București.

- Ishøi, L., Hölmich, P., Aagaard, P., Thorborg, K., Bandholm, T., & Serner, A. (2018). Effects of the Nordic hamstring exercise on sprint capacity in male football players: a randomized controlled trial. Journal of Sports Sciences, 36(14), 1663-1672.

- Timmins, R. G., Bourne, M. N., Shield, A. J., Williams, M. D., Lorenzen, C., & Opar, D. A. (2016). Short biceps femoris fascicles and eccentric knee flexor weakness increase the risk of hamstring injury in elite football (soccer): a prospective cohort study. British Journal of Sports Medicine, 50(24), 1524-1535.

- Plăstoi, C.D. (2017). The theory of multiple intelligences and their impact on learning specific movements in swimming. Bulletin of the Transilvania University of Braşov Series IX: Sciences of Human Kinetics, 10(59), 1.

- Sconce, E., Jones, P., Turner, E., Comfort, P., & Graham-Smith, P. (2015). The validity of the Nordic hamstring lower for a field-based assessment of eccentric hamstring strength. Journal of Sport Rehabilitation, 24(1), 13-20.

- Opar, D. A., Williams, M. D., & Shield, A. J. (2015). Hamstring strain injuries: factors that lead to injury and re-injury. Sports Medicine, 45(3), 305-317.

- Manescu, D.C. (2013). Solutions to fight against overtraining in bodybuilding routine. Marathon, 5(2), 182-186.

- Buchheit, M., Cholley, Y., Nagel, M., & Poulos, N. (2014). The effect of body mass on eccentric knee-flexor strength assessed with an instrumented Nordic hamstring device (Nordbord) in football players. International Journal of Sports Physiology and Performance, 9(6), 1088-1090.

- Bourne, M. N., Opar, D. A., Williams, M. D., & Shield, A. J. (2017). Muscle activation patterns in the Nordic hamstring exercise: impact of prior strain injury. Scandinavian Journal of Medicine & Science in Sports, 27(6), 666-674.

- Badau, D.; Badau, A.; Joksimović, M.; Manescu, C.O.; Manescu, D.C.; Dinciu, C.C.; Margarit, I.R.; Tudor, V.; Mujea, A.M.; Neofit, A.; et al. (2023). Identifying the Level of Symmetrization of Reaction Time According to Manual Lateralization Between Team Sports Athletes, Individual Sports Athletes, and Non-Athletes. Symmetry, 16, 28.

- Freckleton, G., Cook, J., & Pizzari, T. (2014). The predictive validity of a single leg bridge test for hamstring injuries in Australian Rules Football players. British Journal of Sports Medicine, 48(8), 713-717.

- Buckthorpe, M., Wright, S., Bruce-Low, S., Nanni, G., Sturdy, T., & Gross, A. S. (2019). Recommendations for hamstring injury prevention in elite football: translating research into practice. British Journal of Sports Medicine, 53(7), 449-456.

- Ardern, C. L., Taylor, N. F., Feller, J. A., & Webster, K. E. (2014). Psychological responses matter in returning to preinjury level of sport after anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction surgery. The American Journal of Sports Medicine, 42(7), 1549-1558.

- Mănescu, C. O. (2010). Suplimente nutriţionale şi doping în sport. Editura ASE.

- Podlog, L., Banham, S. M., Wadey, R., & Hannon, J. C. (2015). Psychological readiness to return to competitive sport following injury: A qualitative study. The Sport Psychologist, 29(1), 1-14.

- Askling, C. M., Tengvar, M., Tarassova, O., & Thorstensson, A. (2014). Acute hamstring injuries in Swedish elite football: a prospective randomized controlled clinical trial comparing two rehabilitation protocols. British Journal of Sports Medicine, 48(7), 532-539.

- Popescu-Bradiceni, I., Plăstoi, C.D. (2014). Synchronization and the performance sports model subjected to the philosophical interference.

- Shield, A. J., Bourne, M. N., & Opar, D. A. (2018). Preventing hamstring injuries–Part 1: Is there really an eccentric action of the hamstrings in high speed running and does it matter? Journal of Orthopaedic & Sports Physical Therapy, 48(7), 576-579.

- van der Horst, N., Smits, D. W., Petersen, J., Goedhart, E. A., & Backx, F. J. G. (2015). The preventive effect of the Nordic hamstring exercise on hamstring injuries in amateur soccer players. The American Journal of Sports Medicine, 43(6), 1316-1323.

- Manescu, D.C. (2013). Solutions to fight against overtraining in bodybuilding routine. Marathon, 5(2), 182-186.

- Schache, A. G., Dorn, T. W., Blanch, P. D., Brown, N. A., & Pandy, M. G. (2012). Mechanics of the human hamstring muscles during sprinting. Medicine & Science in Sports & Exercise, 44(4), 647-658.

- Oakley, A. J., Jennings, J., & Bishop, C. J. (2018). Holistic hamstring health: Not just the Nordic hamstring exercise. Strength & Conditioning Journal, 40(2), 37-48.

- Badau, D., Badau, A., Ene-Voiculescu, V., Ene-Voiculescu, C., Teodor, D. F., Sufaru, C., Dinciu, C. C., Dulceata, V., Manescu, D. C., & Manescu, C. O. (2025). El impacto de las tecnologías en el desarrollo de la velocidad repetitiva en balonmano, baloncesto y voleibol. Retos, 64, 809–824.

- Petersen, J., Thorborg, K., Nielsen, M. B., Budtz-Jørgensen, E., & Hölmich, P. (2011). Preventive effect of eccentric training on acute hamstring injuries in men’s soccer: a cluster-randomized controlled trial. The American Journal of Sports Medicine, 39(11), 2296-2303.

- Higashihara, A., Nagano, Y., Ono, T., & Fukubayashi, T. (2015). Relationship between the peak torque of hamstrings and joint angles at which peak torque occurred. Journal of Sports Sciences, 33(3), 274-280.

- Manescu, D.C., (2010). Alimentaţia în fitness şi bodybuilding, Editura ASE, Bucureşti.

- Guex, K., Millet, G. P., & Morisod, C. (2016). Hamstring architectural and functional adaptations following long vs. short muscle length eccentric training. Frontiers in Physiology, 7, 340.

- Malliaropoulos, N., Mendiguchia, J., Pehlivanidis, H., Papadopoulou, S., Valle, X., & Malliaras, P. (2012). Hamstring exercises for track and field athletes: injury and exercise biomechanics, and possible implications for exercise selection and primary prevention. British Journal of Sports Medicine, 46(12), 846-851.

- Plastoi, C. (2014). The Increase Sports Performance Skiers with Modern Audiovisual Technology Contribution, Annals of “Dunarea de Jos” University of Galati. Fascicle XV, Physical Education and Sport Management, 1, 139-141.

- Ribeiro-Alvares, J. B., Marques, V. B., Vaz, M. A., & Baroni, B. M. (2018). Four weeks of Nordic hamstring exercise reduce muscle injury risk factors in young adults. Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research, 32(5), 1254-1262.

- Brughelli, M., & Cronin, J. (2008). Preventing hamstring injuries in sport. Strength & Conditioning Journal, 30(1), 55-64.

- Manescu, D.C. (2015). Elements of the specific conditioning in football at university level. Editura ASE.

- Mendiguchia, J., Edouard, P., Samozino, P., Brughelli, M., Cross, M., Ross, A., ... & Morin, J. B. (2016). Field monitoring of sprinting power–force–velocity profile before, during and after hamstring injury: two case reports. Journal of Sports Sciences, 34(6), 535-541.

- Lord, C., Ma’ayah, F., & Blazevich, A. J. (2018). Change in knee flexor torque after fatiguing exercise identifies previous hamstring injury in football players. Scandinavian Journal of Medicine & Science in Sports, 28(3), 1235-1243.

- Brukner, P. (2015). Hamstring injuries: prevention and treatment—an update. British Journal of Sports Medicine, 49(19), 1241-1244.

- Hägglund, M., Waldén, M., & Ekstrand, J. (2013). Risk factors for lower extremity muscle injury in professional soccer: the UEFA Injury Study. The American Journal of Sports Medicine, 41(2), 327-335.

- Heiderscheit, B. C., Sherry, M. A., Silder, A., Chumanov, E. S., & Thelen, D. G. (2010). Hamstring strain injuries: recommendations for diagnosis, rehabilitation, and injury prevention. Journal of Orthopaedic & Sports Physical Therapy, 40(2), 67-81.

- Plăstoi, C.D., & Popescu-Brădiceni, I. (2016). Contributions regarding the use of video analysis in improving sports technique. Journal of Sport and Kinetic Movement, 27(2), 76-81.

- Ekstrand, J., Waldén, M., & Hägglund, M. (2016). Hamstring injuries have increased by 4% annually in men’s professional football, since 2001: a 13-year longitudinal analysis of the UEFA Elite Club injury study. British Journal of Sports Medicine, 50(12), 731-737.

- Schuermans, J., Van Tiggelen, D., Danneels, L., & Witvrouw, E. (2016). Biceps femoris and semitendinosus—teammates or competitors? New insights into hamstring injury mechanisms in male football players: a muscle functional MRI study. British Journal of Sports Medicine, 50(22), 1315-1321.

- Manescu, D. C. (2025). Big Data Analytics Framework for Decision-Making in Sports Performance Optimization. Preprints. [CrossRef]

- Malone, S., Roe, M., Doran, D. A., Gabbett, T. J., & Collins, K. D. (2017). Protection against spikes in workload with aerobic fitness and playing experience: The role of the acute: chronic workload ratio on injury risk in elite Gaelic football. International Journal of Sports Physiology and Performance, 12(3), 393-401.

- Thorborg, K., Krommes, K. K., Esteve, E., Clausen, M. B., Bartels, E. M., & Rathleff, M. S. (2017). Effect of specific exercise-based football injury prevention programmes on the overall injury rate in football: a systematic review and meta-analysis of the FIFA 11 and 11+ programmes. British Journal of Sports Medicine, 51(7), 562-571.

- Roe, M., Malone, S., Blake, C., Collins, K., & Gissane, C. (2017). A six stage operational framework for individualising injury risk management in sport. Injury Epidemiology, 4(1), 26.

Figure 1.

Schematic representation of the randomized controlled trial design, participant allocation, and intervention overview.

Figure 1.

Schematic representation of the randomized controlled trial design, participant allocation, and intervention overview.

Figure 2.

Flowchart detailing the statistical analysis procedures, including data collection, screening, normality assessment, parametric and non-parametric analyses, post-hoc testing, effect size calculation, and interpretation of results.

Figure 2.

Flowchart detailing the statistical analysis procedures, including data collection, screening, normality assessment, parametric and non-parametric analyses, post-hoc testing, effect size calculation, and interpretation of results.

Figure 3.

Mean 30-meter sprint performance before and after the 6-week intervention in the eccentric training and control groups. Error bars represent standard deviations. An asterisk (*) indicates a statistically significant difference (p < 0.01) within the eccentric group.

Figure 3.

Mean 30-meter sprint performance before and after the 6-week intervention in the eccentric training and control groups. Error bars represent standard deviations. An asterisk (*) indicates a statistically significant difference (p < 0.01) within the eccentric group.

Figure 4.

Comparative hamstring peak torque (Nm) pre- and post-intervention for both eccentric and control groups. Error bars represent standard deviations; asterisks (*) indicate statistically significant differences (p < 0.01).

Figure 4.

Comparative hamstring peak torque (Nm) pre- and post-intervention for both eccentric and control groups. Error bars represent standard deviations; asterisks (*) indicate statistically significant differences (p < 0.01).

Figure 5.

Pre- and post-intervention outcomes in sprint time, hamstring torque, and EMG activation.

Figure 5.

Pre- and post-intervention outcomes in sprint time, hamstring torque, and EMG activation.

Figure 6.

Longitudinal evolution of 30-meter sprint performance (left) and maximal hamstring torque (right) in the eccentric training group and control group throughout the 6-week intervention period. Data points represent weekly mean values for both groups, clearly highlighting the progressive differences observed between the two rehabilitation strategies.

Figure 6.

Longitudinal evolution of 30-meter sprint performance (left) and maximal hamstring torque (right) in the eccentric training group and control group throughout the 6-week intervention period. Data points represent weekly mean values for both groups, clearly highlighting the progressive differences observed between the two rehabilitation strategies.

Figure 7.

Radar plot summarizing neuromuscular activation and coordination indicators before and after the intervention period. The eccentric training group exhibited notable improvements across all measured neuromuscular parameters (solid lines) compared to minimal changes in the control group, clearly reflecting enhanced muscle function and coordination.

Figure 7.

Radar plot summarizing neuromuscular activation and coordination indicators before and after the intervention period. The eccentric training group exhibited notable improvements across all measured neuromuscular parameters (solid lines) compared to minimal changes in the control group, clearly reflecting enhanced muscle function and coordination.

Table 1.

Demographic and descriptive characteristics of participants included in the eccentric training and control groups. Data are presented as means ± standard deviations.

Table 1.

Demographic and descriptive characteristics of participants included in the eccentric training and control groups. Data are presented as means ± standard deviations.

| Variable |

Eccentric Group (n=9) |

Control Group (n=9) |

Total (N=18) |

| Age (years) |

21.2 ± 1.1 |

21.0 ± 1.0 |

21.1 ± 1.0 |

| Height (cm) |

179.3 ± 4.8 |

178.7 ± 5.1 |

179.0 ± 4.8 |

| Weight (kg) |

76.2 ± 6.5 |

75.4 ± 7.2 |

75.8 ± 6.7 |

| BMI (kg/m2) |

23.7 ± 1.4 |

23.6 ± 1.5 |

23.6 ± 1.4 |

| Sports Experience (years) |

6.8 ± 1.7 |

6.5 ± 1.9 |

6.7 ± 1.8 |

| Time since injury (months) |

8.2 ± 2.1 |

7.9 ± 2.4 |

8.1 ± 2.2 |

Table 3.

Summary of sprint performance before and after the 6-week intervention, including statistical significance, confidence intervals, and effect sizes (Mean ± SD).

Table 3.

Summary of sprint performance before and after the 6-week intervention, including statistical significance, confidence intervals, and effect sizes (Mean ± SD).

| Group |

Players (n) |

Pre-intervention

(Mean ±SD) |

Post-intervention

(Mean ±SD) |

Change (%) |

95% CI of Change |

Effect

Size (d) |

Effect Interpretation |

p-value |

| Eccentric |

15 |

4.45 ± 0.02 |

4.20 ± 0.02 |

-5.6% |

-5.8%, -5.4% |

1.38 |

Large |

< 0.01 |

| Control |

15 |

4.44 ± 0.02 |

4.40 ± 0.02 |

-0.9% |

[-1.1%, -0.7%] |

0.22 |

Small |

0.18 |

Table 4.

Summary of hamstring isokinetic strength (peak torque) changes pre- and post-intervention, including statistical significance, confidence intervals, and effect sizes (Mean ± SD).

Table 4.

Summary of hamstring isokinetic strength (peak torque) changes pre- and post-intervention, including statistical significance, confidence intervals, and effect sizes (Mean ± SD).

| Muscle Action |

Group |

Pre-intervention (Nm) |

Post-intervention (Nm) |

Change (%) |

95% CI |

Effect Size (d) |

Interpretation |

p-value |

| Concentric |

Eccentric |

123.4 ± 9.6 |

141.5 ± 10.2 |

+14.7% |

[+12.5%, +16.9%] |

1.82 |

Large |

<0.01 |

| Concentric |

Control |

122.7 ± 11.3 |

127.3 ± 10.8 |

+3.7% |

[+1.5%, +5.9%] |

0.41 |

Small |

0.09 |

| Eccentric |

Eccentric |

135.6 ± 8.9 |

154.9 ± 9.8 |

+14.2% |

[+12.0%, +16.4%] |

2.06 |

Large |

<0.01 |

| Eccentric |

Control |

134.7 ± 9.7 |

139.5 ± 9.5 |

+3.6% |

[+1.4%, +5.8%] |

0.39 |

Small |

0.10 |

Table 5.

Summary of pre- and post-intervention performance outcomes.

Table 5.

Summary of pre- and post-intervention performance outcomes.

| Variable |

Group |

Pre

(Mean ± SD) |

Post

(Mean ± SD) |

Δ% Change |

p-value |

30m

Sprint Time (s) |

Eccentric |

4.45 ± 0.18 |

4.20 ± 0.14 |

–5.6% |

< 0.01 |

| |

Control |

4.44 ± 0.17 |

4.40 ± 0.19 |

–0.9% |

0.18 |

Hamstring Torque

(Nm) |

Eccentric |

123.4 ± 9.6 |

141.5 ± 10.2 |

+14.7% |

< 0.01 |

| |

Control |

122.7 ± 11.3 |

127.3 ± 10.8 |

+3.7% |

0.09 |

EMG

Peak Activation (%MVIC) |

Eccentric |

83.2 ± 6.7 |

91.8 ± 5.4 |

+10.3% |

< 0.01 |

| |

Control |

84.0 ± 7.1 |

85.3 ± 6.9 |

+1.5% |

0.24 |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).