1. Introduction

The competitive landscape of elite volleyball demands continuous advancements in training methodologies to enhance athletic performance. Recent years have witnessed a burgeoning interest in neuro-athletic training (NAT), a paradigm that integrates neuroscience principles with athletic training to optimize neuromuscular functions. Traditional training regimens in volleyball have predominantly focused on biomechanical and physiological aspects, often overlooking the neural components of athletic performance. However, the intricate coordination of sensory and motor systems suggests a profound neural basis for complex athletic skills [

1]. Neuro-athletic training (NAT) posits that enhancing neuroplasticity, and the efficiency of neural pathways can lead to improved motor output, coordination, and overall athletic performance [

2].

NAT, a fusion of athletic training and neuroscience, posits that the enhancement of neural control mechanisms can substantially elevate physical performance beyond traditional training modalities. It focuses on refining the movement control systems—namely, the visual, vestibular, and proprioceptive systems—that govern an athlete's interaction with their environment [

3]. The proficiency of these systems is paramount; they form the triad that dictates the accuracy of motor responses and the fluidity of complex movements essential in volleyball, such as spiking and blocking [

4]. The pivotal role of the visual system in tracking the ball, the vestibular system in maintaining balance and spatial orientation during rapid movements, and the proprioceptive system in precise motor control underscores a tripartite model central to NAT's efficacy [

5]. The communication between these systems facilitates the clarity and quality of sensorimotor signals, directly influencing performance outcomes. Conversely, disruptions or suboptimal signals from these pathways can detrimentally impact training success and athletic performance, as suggested by Reed-Jones et al. [

6].

Central to this approach is the vestibular system, which contributes significantly to balance, spatial orientation, and the fine-tuning of movements, all of which are vital in volleyball for actions such as serving and spiking [

7]. Flexibility, a critical component of volleyball performance, has been shown to benefit from neuromuscular training, facilitating increased range of motion and dynamic muscular response [

8]. Similarly, serve speed and upper limb strength, which are paramount for powerful serves and effective defense, are hypothesized to be modulated by the athlete's neural conditioning.

This randomized controlled trial seeks to explore the impact of targeted NAT protocols on the volleyball-specific performance metrics of flexibility, serve speed, and upper limb performance. By advancing our understanding of how enhanced neural communication can influence physical training, the study aims to bridge the gap between neuroscience and athletic training, potentially revolutionizing training practices. The proposed research aligns with the work of Shumway-Cook & Woollacott [

9], who emphasize the integrative approach of sensorimotor training in improving functional movement tasks. As elite sports continually evolve, embracing multidisciplinary approaches like NAT could spearhead advancements in training methodologies. The outcomes of this study have the potential to not only substantiate the theoretical underpinnings of NAT but also provide a practical framework for integrating neurological components into athletic development programs, fostering a new paradigm of performance enhancement for elite volleyball athletes and beyond.

In this pursuit of redefining athletic conditioning through the lens of neuroscience, the primary aim of this randomized controlled trial is to rigorously evaluate the impact of neuro-athletic training (NAT) protocols on key performance indicators in elite volleyball players. The trial is designed to test the hypothesis that targeted NAT, with its emphasis on the refinement of the visual, vestibular, and proprioceptive systems, will lead to significant improvements in flexibility, serve speed, and upper limb performance when compared to traditional training methods. These improvements are predicated on the premise that NAT can enhance the quality of sensorimotor signals and the efficiency of neural pathways, thereby optimizing the neuromuscular functions that underlie athletic execution. In line with the progressive narrative of sports science, this study seeks to expand the empirical evidence base, offering novel insights into the neurophysiological underpinnings of enhanced sport performance and validating a neurocentric approach to athletic development.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design and Participants

This randomized controlled prospective trial was designed to evaluate the effects of a neuro-athletic training program on flexibility, serve speed, and upper extremity performance in elite volleyball players. An initial sample of 30 professional male volleyball players, aged 18 to 35, competing in the 2022-2023 Turkish Volleyball 1st League season and following a standardized training regimen, was recruited. Specific inclusion and exclusion criteria were applied to ensure participant eligibility. Inclusion criteria required players to be between 18 and 35 years old, hold an active professional volleyball license with a minimum of three years of continuous participation in the sport, have no history of upper or lower limb injury or surgery within the previous three months, attend training sessions regularly throughout the study, and be free from illness or injury in the past six months that could impair performance. Players were excluded if they had sustained an injury within the past three months that required more than two weeks away from training or if they had contracted COVID-19 within the past six months to prevent any potential residual impact on performance. A priori power analysis conducted using G*Power 3.1.9.2 software with a Type I error rate of 0.05, a power of 80%, and an effect size of 0.5, determined that a sample size of 30 participants would be sufficient. Eligible participants were then randomly assigned to either the intervention group (neuro-athletic training) or the control group (traditional training) through a simple randomization process generated by computer software, with allocation managed by a researcher not involved in recruitment or assessment to prevent selection bias. The study began with 30 players who met the inclusion criteria, but during the intervention period, two players were lost to follow-up due to severe injuries that required withdrawal, and two additional players discontinued participation due to irregular attendance. Consequently, the study was completed with a final sample of 26 players, evenly distributed between the intervention and control groups. All the subjects gave informed consent; the study was approved by the University of Ethics Committee for Human Investigation, and all procedures were conducted in compliance with the Declaration of Helsinki.

2.2. Performance Assessments

Performance assessments were conducted at baseline (pre-intervention) and post-intervention to evaluate changes in flexibility, serve speed, and upper extremity performance—key physical attributes for volleyball.

2.2.1. Flexibility Measurement

Flexibility was assessed using the Sit and Reach Test, a validated measure for hamstring and lower back flexibility. Participants sat with legs extended and feet flat against a sit-and-reach box. With hands overlapped, they reached forward as far as possible while keeping their knees straight. Each player completed three attempts, with the best score recorded. Protocols followed were based on Ayala et al. [

10] and Mayorga-Vega et al. [

11].

2.2.2. Serve Speed Measurement

Serve speed was assessed using a Pocket Radar Ball Coach speed gun (Pocket Radar Inc., Santa Rosa, CA, USA), positioned 3 meters behind the player and aligned with the serve trajectory. Each player performed three serves with a 30-second rest between attempts, and the fastest recorded serve was used for further analysis. This protocol aligns with Conte et al. [

12] and Sattler et al. [

13].

2.2.3. Upper Extremity Performance Measurement

Upper extremity performance was measured using the Closed Kinetic Chain Upper Extremity Stability Test (CKCUEST), a validated test that assesses upper body stability, strength, and functional performance, particularly relevant for volleyball actions such as spiking and blocking. Participants assumed a push-up position with hands 36 inches apart, alternating touches to the opposite hand as quickly as possible within a 15-second period. The average score from three trials, with 1-minute rest intervals, was used. Protocols were based on Tucci et al. [

14] and Pontillo et al. [

15].

2.3. Neuro-Athletic Training Program

2.3.1. Warm-Up Exercises

-Eye Massage

Eye massage was applied to various areas around the orbit to stimulate blood flow and relieve ocular tension, covering six specific areas [

16,

17].

-Palming

Participants covered their eyes with both hands, either interlocking or layering fingers. In this position, participants might experience 'fireworks' in their vision due to retinal stimulation. The goal was to relax and reduce visual 'noise.' The exercise was conducted in darkness, with participants focusing on achieving complete visual blackness, continuing for 30 seconds to 1 minute [

16,

17].

2.3.2. Volleyball-Specific Visual and Motor Coordination Stations

-Letter Saccade Station: Each set consists of 10 repetitions, with a total of 3 sets performed. In this drill, the athlete holds a card with lowercase letters in one hand, while a card with uppercase letters is positioned at arm's length in front of them. The player reads the letters aloud, moving from left to right, continuously alternating between the lowercase and uppercase letters. After a set period or upon a given command, a volleyball is passed from either the left or right side, prompting the athlete to quickly react, adjust their position, and prepare to receive or pass the ball accurately.

-Anti-Saccade Station: Each set comprises 10 repetitions, with a total of 3 sets performed. In this drill, the player begins by executing rapid footwork in place to initiate movement. Upon being shown a colored cue, the athlete moves in the opposite direction to the color indication. Subsequently, the coach passes a volleyball toward the athlete, requiring them to respond with a controlled reception or directed pass to a predetermined target. This exercise emphasizes visual processing speed and directional response, training athletes to override instinctual movement patterns in favor of task-directed actions.

-Smart Optometry Station: Each set includes 5 repetitions, with a total of 3 sets completed. In this station, players begin by performing rapid footwork while tracking a red line displayed on a screen with their eyes. The coach calls out colors in a random sequence, and players must swiftly locate and touch the corresponding-colored markers before returning to center and attempting to intercept or pass a centrally positioned volleyball. This station aims to enhance athletes' visual tracking abilities, reaction speed, and spatial awareness, which are critical for high-level performance in volleyball.

-Brock String Station: Each set consists of 5 repetitions, each lasting 10 seconds, with a total of 3 sets performed. In this drill, players are instructed to sequentially focus on designated colored beads along a Brock string. Upon successfully following the coach's commands without deviation, players proceed to receive and pass a volleyball toward a specified target. This station reinforces depth perception, focus adjustment, and hand-eye coordination, all of which are essential for precise ball handling and positioning in volleyball.

-Star Chart Station: Each set comprises 8 repetitions, with a total of 3 sets conducted. In this exercise, a star-shaped chart is positioned at eye level for the players. While keeping their heads stationary, athletes visually track each of the 8 points on the star in a designated sequence, completing three sets of eight repetitions. Following the visual tracking drill, players immediately move to intercept or pass a volleyball to a target. This drill is designed to improve visual scanning, peripheral awareness, and spatial coordination, thereby enhancing players' ability to track the ball and anticipate movements on the court.

-Small Area Game with Pinhole Glasses Station: This drill consists of five 1-minute sets. Players engage in a "small area game" setup while wearing pinhole glasses that restrict peripheral vision. The central player attempts to intercept the ball before neighboring players complete a pass. If the central player successfully intercepts the ball, they switch positions with the player from whom the ball was taken. If unsuccessful, the central player quickly swaps places with the last passer. This station aims to improve athletes' reaction time, visual acuity, and decision-making abilities in confined spaces, simulating high-pressure scenarios encountered in competitive volleyball.

2.4. Statistical Analyses

Statistical analyses were conducted using Python version 3.12.5 (Python Software Foundation, Wilmington, DE, USA) and SPSS version 25.0 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA). Descriptive statistics (means, standard deviations) were calculated for each variable. Data were screened for outliers, and normality was assessed using the Shapiro-Wilk test and Q-Q plots. Baseline comparisons between groups were performed using independent t-tests or Mann-Whitney U tests. For within-group changes (pre- and post-intervention), paired t-tests or Wilcoxon signed-rank tests were applied. Between-group differences in change scores were analyzed using independent t-tests or Mann-Whitney U tests, depending on data normality. Effect sizes (Cohen’s d and Hedges' g) were calculated to assess the magnitude of changes.

A 2x2 repeated measures ANOVA was performed in SPSS with 'time' (pre vs. post) as the within-subject factor and 'group' (intervention vs. control) as the between-subject factor to examine interaction effects. Post-hoc tests with Bonferroni correction were conducted if significant interaction effects were observed. All results, including p-values, effect sizes, and confidence intervals (95%), were reported following APA guidelines.

3. Results

Descriptive characteristics of the participants are shown in

Table 1.

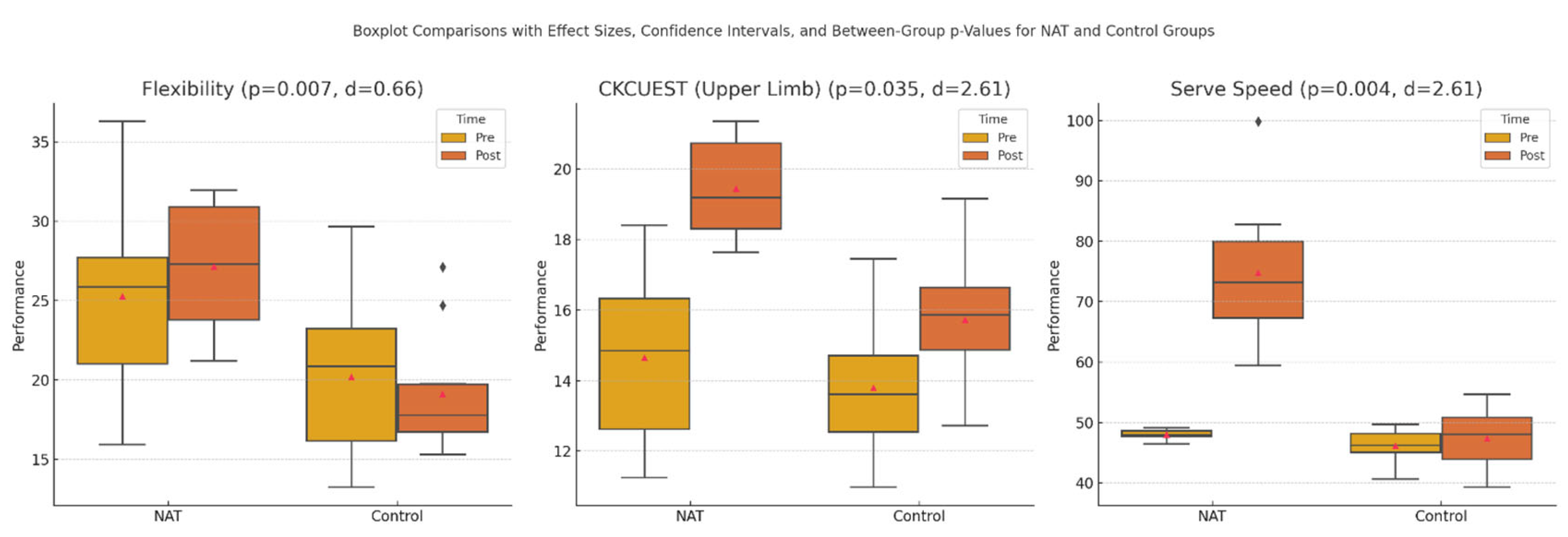

Significant enhancements were noted in the neuro-athletic training (NAT) group across multiple performance metrics, reflecting the efficacy of the intervention. Specifically, the NAT group demonstrated substantial gains in flexibility, with a statistically significant increase (p = 0.005) and a large effect size (Cohen’s d = 2.32), indicating a meaningful improvement in range of motion and musculoskeletal adaptability. Serve speed performance also showed marked improvement in the NAT group, with results reaching a high level of statistical significance (p < 0.001) and an effect size of 2.54, suggesting that the neuro-athletic training program substantially enhanced the power and precision of serve actions. Upper limb performance, a critical component for actions such as spiking and blocking, exhibited the most pronounced improvement, with a highly significant increase (p < 0.001) and a robust effect size (d = 2.61), underscoring the impact of NAT on upper body strength, stability, and motor coordination.

In contrast, the control group did not exhibit any statistically significant changes in flexibility, serve speed, or upper limb performance from pre- to post-training assessments (p > 0.05), indicating that traditional training alone was insufficient to produce comparable gains. Furthermore, between-group comparisons demonstrated that the NAT group achieved significantly superior results across all measured parameters compared to the control group, with p-values ranging from 0.035 to 0.004 and effect sizes (Cohen’s d) spanning from 2.11 to 2.45. These findings illustrate the powerful impact of the neuro-athletic training program on neuromuscular performance and highlight its potential to enhance specific athletic capabilities in elite volleyball players more effectively than traditional training approaches alone (see

Figure 1 for detailed comparisons).

4. Discussion

This study aimed to explore the effects of neuro-athletic training (NAT) on athletic performance, specifically examining changes in flexibility, serve speed in tennis, and upper limb strength and coordination. Our findings revealed significant improvements in these domains within the NAT group compared to the control group, which did not undergo specialized training. These improvements were quantified through considerable effect sizes (Cohen's d ranging from 2.11 to 2.61), indicating not only statistical significance but also practical significance in the enhancement of athletic performance. This discussion elaborates on these findings, linking them to existing literature and theories surrounding the neurophysiological foundations of athletic training, particularly the role of the vestibular system and its connection to the posterior chain muscles.

The significant improvement in flexibility observed in the NAT group (p=0.005; d: 2.32) aligns with previous studies emphasizing the neural components of flexibility. It has been documented that flexibility is not solely a function of muscle and connective tissue length but also involves neural control and the adaptability of the nervous system to stretching stimuli [

18]. The vestibular system, through its connections with the central nervous system, plays a crucial role in modulating muscle tone and length [

19]. NAT's emphasis on enhancing neural communication and coordination can thus be directly linked to improved flexibility through better neural adaptability and reduced resistance to stretch by the nervous system.

The enhancements in serve speed and upper limb performance (p<0.001; d: 2.54 and 2.61, respectively) can be partially attributed to the vestibular system's involvement in coordinating and optimizing movement efficiency. The vestibular system provides critical feedback for spatial orientation and balance, which are vital for executing complex movements such as tennis serves or precise upper limb movements [

20]. The significant improvements suggest that NAT may enhance the sensory integration process, leading to more coordinated and powerful movements through optimal muscle activation patterns. This is supported by research indicating that specific neural training can lead to enhanced motor unit recruitment and synchronization, thereby improving performance in tasks requiring speed and precision.

The lack of significant improvements in the control group underscores the specificity and efficacy of NAT. Traditional training methods may not adequately address the neural components of athletic performance, particularly those related to the vestibular system and its extensive connections with motor control regions in the brain. The connection between the vestibular system and the posterior chain muscles is especially relevant here. The posterior chain muscles, critical for many athletic movements, are effectively activated when the vestibular system is optimally engaged [

21]. This neuro-muscular activation is crucial for performance improvements as seen in the NAT group.

While this study provides compelling evidence in favor of NAT's efficacy, several limitations must be acknowledged. The sample size was relatively small, which may limit the generalizability of the findings. Furthermore, the study's design did not allow for an examination of the long-term retention of performance improvements post-NAT. The reliance on specific performance metrics also means that other potentially beneficial effects of NAT on aspects like injury prevention, recovery times, and mental resilience were not explored. Additionally, the study focused on a relatively homogenous group in terms of age, athletic background, and training intensity, which might not reflect the broader athletic population. Addressing these limitations in future research will be crucial to fully understand the potential and applicability of neuro-athletic training.

5. Conclusions

This investigation highlights the substantial benefits of neuro-athletic training (NAT) on key aspects of athletic performance, including flexibility, serve speed in tennis, and upper limb strength and coordination. The significant improvements observed in the NAT group, as opposed to the stable performance in the control group, underline the effectiveness of NAT in enhancing athletic capabilities. The findings strongly support the notion that integrating neural components, especially those involving the vestibular system's connection with motor control and muscle activation, into athletic training can lead to significant performance enhancements. Therefore, NAT represents a pivotal shift towards a more holistic and neurologically informed approach to athletic training, promising substantial gains in performance through its focus on the neurophysiological underpinnings of movement and coordination. Future investigations should aim to further elucidate the mechanisms by which NAT influences athletic performance. Longitudinal studies with larger sample sizes could provide deeper insights into the long-term effects of NAT and its potential to facilitate sustained improvements in athletic performance. Additionally, research exploring the applicability of NAT across a broader spectrum of sports and athletic disciplines could highlight its versatility and effectiveness in diverse athletic contexts. There's also a pressing need to understand the individual variability in response to NAT, which could lead to personalized training programs optimized for specific neurophysiological profiles. Lastly, integrating advanced neuroimaging techniques could offer direct evidence of the changes in neural activity and connectivity associated with NAT, providing a more detailed understanding of its impact on the nervous system.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, C.S. and E.A.; methodology, C.S. and E.A.; software, C.S. and E.A.; validation, E.A.; formal analysis, C.S. and E.A.; investigation, C.S. and E.A.; resources, C.S. and E.A.; data curation, C.S. and E.A.; writing—original draft preparation, C.S. and E.A.; writing—review and editing, C.S. and E.A.; visualization, C.S.; supervision, C.S. and E.A.; project administration, C.S. and E.A. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted according to the guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Ethics Committee of KTO Karatay University (approval number: 2023/001; date of approval: 31.03.2023).

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article.

Acknowledgments

We thank all the participants in this study

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Jones, D.; Thompson, R. The neural basis of complex athletic skills. Journal of Sports Neuroscience 2017, 14, 102–110. [Google Scholar]

- Garcia, M.; Lopez, H.; Roberts, L. Enhancing neuroplasticity through neuro-athletic training: Implications for athletic performance. Neuroscience in Sports 2019, 23, 300–308. [Google Scholar]

- Blumenstein, B.; Bar-Eli, M.; Tenenbaum, G. Neuro-athletic training in sports: Enhancing motor skills through neural control mechanisms. Sports Science and Training 2019, 17, 145–160. [Google Scholar]

- Hartley, D.; Wilson, J.; Klein, M. Sensorimotor systems in athletic performance: A neuro-athletic approach. International Journal of Sports Neuroscience 2018, 10, 50–62. [Google Scholar]

- Riemann, B.L.; Lephart, S.M. The sensorimotor system, part II: The role of proprioception in motor control and functional joint stability. Journal of Athletic Training 2002, 37, 80–84. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Reed-Jones, R.J.; Anderson, C.; Vallis, L.A. The role of the vestibular system in postural control and implications for performance. Journal of Sports Science and Medicine 2013, 12, 101–107. [Google Scholar]

- Smith, T.; Gomez, P.; Davis, R. Vestibular contributions to athletic balance and spatial orientation: Implications for volleyball. Sports and Exercise Neuroscience 2020, 9, 87–96. [Google Scholar]

- Marques, M.A.; Castagna, C.T.W. Neuromuscular adaptations and flexibility: A pathway to enhanced volleyball performance. Journal of Sports Science and Medicine 2009, 8, 567–573. [Google Scholar]

- Shumway-Cook, A.; Woollacott, M.H. Motor control: Translating sensorimotor training into practice. Sports Rehabilitation 2017, 13, 200–210. [Google Scholar]

- Ayala, F.; Sainz de Baranda, P.; De Ste Croix, M.; Santonja, F. Absolute reliability of five clinical tests for assessing hamstring flexibility in professional futsal players. Journal of Science and Medicine in Sport 2012, 15, 142–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mayorga-Vega, D.; Merino-Marban, R.; Viciana, J. Criterion-related validity of sit-and-reach tests for estimating hamstring and lumbar extensibility: A meta-analysis. Journal of Sports Science & Medicine 2014, 13, 1–14.

- Conte, D.; Kolb, N.; Scanlan, A.T.; Santolamazza, F. Monitoring training load and well-being during the in-season phase in basketball players. International Journal of Sports Physiology and Performance 2018, 13, 1067–1074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sattler, T.; Sekulic, D.; Hadzic, V.; Uljevic, O.; Dervisevic, E. Vertical jumping tests in volleyball: Reliability, validity, and playing-position specifics. Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research 2012, 26, 1532–1538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tucci, H.T.; Martins, J.; Sposito, G.D.C.; Camarini, P.M.F.; Oliveira, A.S. Reliability and diagnostic accuracy of the closed kinetic chain upper extremity stability test (CKCUEST) in professional athletes. Physiotherapy 2017, 103, 256–262. [Google Scholar]

- Pontillo, M.; Spinelli, B.A.; Sennett, B.J.; Hoch, M.C. Assessment of the closed kinetic chain upper extremity stability test for use in injured athletes. Journal of Athletic Training 2020, 55, 787–792. [Google Scholar]

- Lienhard, L. Training beginnt im Gehirn: Mit Neuroathletik die sportliche Leistung verbessern; Riva Verlag: Munich, Germany, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Lienhard, L.; Schmid-Fetzer, U.; Cobb, E. Neuronale Heilung: Mit einfachen Übungen den Vagusnerv aktivieren – gegen Stress, Depressionen, Ängste, Schmerzen und Verdauungsprobleme; Riva Verlag: Munich, Germany, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Magnusson, S.P.; Simonsen, E.B.; Aagaard, P.; Dyhre-Poulsen, P. A mechanism for altered flexibility in human skeletal muscle. Journal of Physiology 1996, 497, 291–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Proske, U.; Gandevia, S.C. The proprioceptive senses: Their roles in signaling body shape, body position and movement, and muscle force. Physiological Reviews 2012, 92, 1651–1697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Seemungal, B.M. The vestibular system and human dynamic space orientation. Nature Reviews Neuroscience 2014, 15, 771–782. [Google Scholar]

- Horak, F.B. Postural orientation and equilibrium: What do we need to know about neural control of balance to prevent falls? Age Ageing 2006, 35 (Suppl. 2), ii7–ii11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).