1. Introduction

Modern physics is based on the concept of four-dimensional spacetime, first introduced in Einstein’s special and general relativity theories. In this concept, three dimensions correspond to space (length, width, height), and one corresponds to time. A single four-dimensional manifold with Lorentzian metric is formed, defining the geometry of the Universe and determining laws of motion for material objects and signal propagation.

Although relativity theory has proved highly effective in describing gravity and large scales, it faces several unresolved issues:

Mass problem of elementary particles: The Standard Model of particle physics describes interactions well but does not provide a complete explanation for why fundamental particles have exactly the masses measured experimentally. The Higgs mechanism partially resolves this but leaves open aspects of the mass-geometry relationship.

Incompatibility with quantum mechanics: General relativity is a classical theory and does not include quantum effects. The unification of gravity and quantum mechanics remains one of the main challenges in modern science.

Nature of time and causality: In the classical theory, time is a single axis perceived as a monotonically increasing quantity. However, quantum phenomena and some cosmological models question the simplicity and linearity of temporal measurement.

Several modern approaches have attempted to extend the classical spacetime model:

Theories with extra spatial dimensions (e.g., string theory) introduce up to 10 or 11 dimensions but require complex mathematical structure and lack unambiguous testable predictions.

Models with additional temporal dimensions — two-time physics (2T physics) — propose two time axes, leading to new symmetries but are difficult to interpret physically and are associated with causality problems.

In this work, a new concept is proposed — to consider time as a three-dimensional manifold with coordinates . This radical paradigm shift assumes that the three time dimensions are fundamental, and space emerges as a derivative interaction of these temporal axes.

The main mathematical tool is the introduction of the Kuznetsov tensor , which characterizes local distortions of the temporal manifold’s metric, similar to how the Ricci tensor describes curvature of spacetime.

Advantages of the proposed model:

Causal structure is preserved — despite the multidimensionality of time, event sequences are not violated.

It becomes possible to explain particle masses via time geometry.

The model provides testable experimental predictions, lacking in many theories with extra dimensions.

In the following sections, we will detail the mathematical structure of the model, dynamic equations, physical interpretation, and experimental testing approaches.

2. Mathematical Formulation

2.1. Temporal Manifold

Consider a three-dimensional smooth temporal manifold , locally diffeomorphic to , with coordinates , corresponding to three independent directions of temporal development.

Let denote the overall manifold of events generated by these coordinates, and let be a smooth embedding defining the “state” position on the temporal manifold.

Each point represents a triple , interpreted as a composite temporal state. The geometry of the manifold is described by a covariant metric tensor , where Greek indices refer to the temporal directions.

2.2. Spatial Metric as a Derivative of Time

For each point

, consider the differential map

:

where

is the tangent space to

at

.

Define the spatial metric

via the inner product of tangent vectors:

where

is the inert scalar product in the state space

, defining the geometry of emerging space.

The metric is a covariant symmetric rank-two tensor, defining local distances and angles between spatial vector directions.

2.3. Introduction of the Kuznetsov Tensor

To describe changes of the metric along temporal directions, introduce the tensor:

where

is one of the temporal coordinates,

.

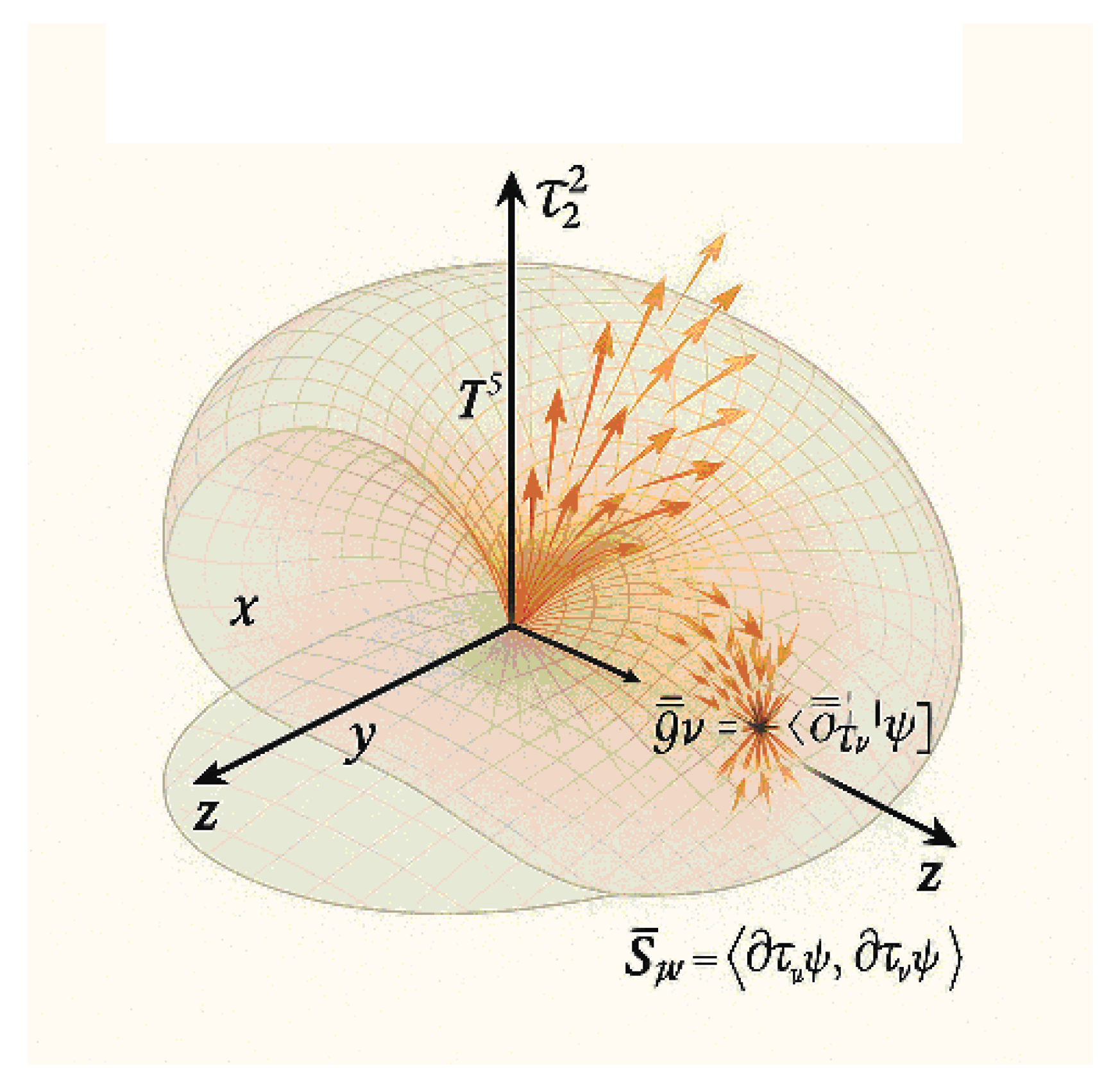

Figure 1.

Singular model of three-dimensional time and Kuznetsov tensor.

Figure 1.

Singular model of three-dimensional time and Kuznetsov tensor.

The figure conceptualizes time as a multidimensional structure. Spatial coordinates are depicted orthogonally, while temporal components are shown along axes and , interpreted as temporal directions (e.g., ).

Orange vectors emanate from the origin pointing toward the quantum expression:

interpreted as an effective spatial metric emerging from quantum interaction in the multidimensional time structure.

These vectors embody components of the Kuznetsov tensor , describing metric distortions along temporal directions. They visualize the dynamic transfer of structure from temporal manifold into space. This tensor characterizes local metric distortions analogously to the Ricci tensor reflecting spacetime curvature. may contain singularities reflecting physical phenomena such as energy concentration or mass generation.

Properties of the Kuznetsov tensor:

Symmetry: because is symmetric.

Dependence on temporal direction , reflecting temporal anisotropy.

Represents local temporal dynamics and transition to spatial structures.

Also introduced is the tensor:

a generalized density tensor related to derivatives of the wave function over temporal coordinates, reflecting temporal fluctuations and structural features of time as a physical quantity.

2.4. Relation to Classical One-Dimensional Time Axis

Restricting to a one-dimensional section , for example, fixing , the model reduces to classical linear time axis , and transitions to the usual spatial metric.

Thus, the proposed three-dimensional time structure generalizes the standard model.

2.5. Analytical Methods

Methods of differential geometry are applied for working with the metric and Kuznetsov tensor:

Computation of covariant derivatives and curvature.

Analysis of metric singularities through eigenvalues of .

Study of metric evolution along temporal axes.

This provides the foundation for constructing dynamic equations and physical interpretations.

3. Dynamics of the Temporal Metric

3.1. General Dynamic Equation

The dynamic evolution of the metric

in the three-dimensional temporal manifold is governed by the equation:

where:

is the change of the metric along the temporal coordinate ,

is the Kuznetsov tensor describing local distortions and singularities,

are components of the Ricci tensor defined on the temporal manifold ,

is the cosmological constant setting the global background.

This equation can be considered as a generalization of a modified Ricci flow for the temporal manifold.

3.2. Ricci Tensor for the Temporal Manifold

The Ricci tensor

relates to the curvature of the space formed as a consequence of time’s structure. It is computed from the curvature tensor components

:

In the context of three-dimensional time, this tensor reflects intrinsic geometric properties and influences metric evolution.

3.3. Role of the Cosmological Constant

The parameter Λ models the influence of the temporal background on the local structure. Its magnitude and sign can determine expansion or contraction of space and affect stability of the solutions of the dynamic equation.

3.4. Special Cases and Symmetries

, the equation reduces to the classical Ricci flow describing geometric evolution.

Solutions with constant metric correspond to stationary states.

Symmetries of the manifold determine solution classification — e.g., isotropic and anisotropic configurations.

3.5. Solution Methods

To study the dynamic equation, the following methods are used:

Analytical methods for special symmetries and approximations.

Numerical methods for the general case, including mesh modeling and variational approaches.

Comparison with experimental data to calibrate model parameters.

This dynamics governs how three temporal axes interact and how from this interaction emerges observable space with its geometry and physical properties.

4. Entropy Functional and Stability

4.1. Definition of the Functional

To analyze the stability of configurations of the temporal manifold and the metric

, a generalized entropy functional is introduced:

where:

is a scalar function called the temporal potential,

is the gradient of f with respect to the coordinates ,

is the scalar curvature of the temporal manifold derived from the Ricci tensor,

is the norm squared of the Kuznetsov tensor,

is the volume element on the manifold .

4.2. Physical Meaning

The functional can be interpreted as a generalized entropy or an “energy” measure of the temporal manifold’s configuration accounting for local distortions (via ) and geometry (via ). The weighting factor acts similarly to a probability distribution in statistical mechanics.

4.3. Extremum Conditions and Variational Principle

Considering the variation of the functional with respect to

and

:

leads to equations linking metric changes and the potential

. Extremum conditions correspond to stable states of the system where dynamics slow down or stop.

4.4. Relation to Perelman’s Functional

Similarly to the functional introduced by Grigori Perelman for studying Ricci flow, serves as a measure controlling the “entropy” of the geometry. However, here the functional is extended by the term, accounting for specific temporal distortions. This extension broadens the class of models and provides new possibilities for describing evolution and stability.

5. Physical Interpretations and Consequences

5.1. Particle Mass as a Geometric Effect

In the proposed model, the mass of elementary particles is interpreted as an eigenvalue of an operator related to the geometry of the temporal manifold. Consider the equation:

where:

is the Laplacian operator constructed with respect to the metric on the temporal manifold ,

is the particle’s wavefunction depending on the temporal coordinates,

is a potential functionally dependent on the Kuznetsov tensor ,

is the particle mass.

Thus, the particle mass emerges as a result of local distortions of the temporal metric and singularities described by .

This perspective suggests a purely geometric origin of mass, without invoking external scalar fields (such as the Higgs field in the Standard Model), but instead tying mass directly to the internal structure of time itself.

This geometric approach opens new avenues for understanding:

why different fundamental particles (electron, muon, quarks) have different masses;

how mass might vary under changes in the geometry of time (e.g., in early cosmology);

and potentially allows calculation of particle masses from first principles based on the structure of .

5.2. Gravity as Geometry of Time

Anisotropy and curvature in the three-dimensional time structure produce effects equivalent to a gravitational field. Unlike classical general relativity, where gravity arises from curvature of four-dimensional spacetime, here gravity arises from the dynamics of the temporal metric manifold. This opens new pathways for unifying gravity with quantum phenomena, since the dynamics of time are directly linked to quantum states.

5.3. Quantum Effects and Preservation of Causality

The three-dimensional temporal structure provides a natural explanation for quantum nonlocality, while preserving strict causal order of events. The model ensures monotonic temporal evolution along each time axis , excluding paradoxes of backward causality.

5.4. Implications for Cosmology and Fundamental Physics

Explaining the origin of the cosmological constant Λ as a property of the temporal manifold.

Modeling dark energy and dark matter dynamics via the Kuznetsov tensor.

Offering new perspectives on the formation of the universe’s structure in early cosmological epochs.

This section connects the mathematical constructions with observed physics, offering new interpretations of fundamental phenomena.

6. Possible Experimental Verifications

6.1. Spectroscopy and Particle Masses

Since the model provides expressions for the masses of elementary particles through the geometry of time, high-precision experiments measuring the masses of electrons, muons, quarks, and other fundamental particles can test the model’s predictions. Any discrepancies between calculated and observed values will indicate the need for adjustments or constraints on the parameters of the Kuznetsov tensor.

6.2. Atomic Clocks and Time Anisotropy

The three-dimensional structure of time implies that small anisotropies in temporal intervals could be observed along different temporal directions. Experiments using ultra-precise atomic clocks arranged in various orientations and environmental conditions are capable of detecting such anisotropies, thereby confirming or refuting the model.

6.3. Analysis of Gravitational Waves

The dynamics of the temporal manifold affect the properties of gravitational wave propagation. Comparing predictions with data from LIGO, Virgo, and other detectors may reveal deviations from general relativity’s predictions and assess the influence of the Kuznetsov tensor.

6.4. Quantum Entanglement and Causality

The model predicts strict preservation of causality even under quantum nonlocality conditions. Experiments on quantum entanglement conducted over large distances can test conformity with the model’s predictions regarding the structure of time and causality.

These directions open prospects for practical verification of the theory and its potential refinement.

7. Discussion and Conclusion

7.1. Summary of the Research

This work proposes an innovative theory that treats time as a three-dimensional manifold , based on the Kuznetsov tensor , which describes local distortions and dynamics of the temporal metric. The proposed model allows interpreting the mass of elementary particles as a geometric effect, understanding gravity through time curvature, and preserving causality even with three temporal dimensions. A key advantage is the presence of specific experimentally testable predictions, which distinguishes this theory from many abstract models with additional dimensions.

7.2. Limitations and Challenges

Further formalization and deeper mathematical analysis of the dynamic equations is needed.

Experimental verification of some aspects of the model is challenging due to the small magnitude of effects or technological limitations.

Integration with existing quantum mechanics and general relativity theories is required to create a unified theoretical framework.

7.3. Prospects for Development

Extending the model to higher-dimensional spaces and studying interactions with other fundamental fields.

Developing numerical methods and software for modeling the evolution of the temporal manifold.

Conducting targeted experiments to verify specific predictions, especially concerning particle masses and time anisotropy.

Conclusion

The three-dimensional time model presented in this work offers a radically new perspective on the fundamental foundations of physical reality. Considering time as an independent three-dimensional manifold, together with the introduction of the Kuznetsov tensor , enables a novel interpretation of the origin of space, mass, and gravity as consequences of the internal dynamics of the temporal metric. This approach removes the limitations of one-dimensional time and opens the possibility to describe anisotropies, singularities, and causal connections within a more general geometric structure.

The model maintains mathematical rigor, aligns with quantum theory, and provides experimentally verifiable predictions. Its potential lies not only in explaining existing physical observations but also in establishing a foundation for a new unified theory encompassing quantum fields, gravity, and matter structure. It may serve as a cornerstone for the next stage of theoretical physics development.

References

- Perelman, G. The entropy formula for the Ricci flow and its geometric applications. arXiv:math/0211159 (2002). Available at: en.wikipedia.org, arxiv.org, reddit.com, link.springer.com, degruyter.com.

- Cao, H.-D., Zhu, X.-P. A complete proof of the Poincaré and geometrization conjectures — application of the Hamilton–Perelman theory of the Ricci flow. Asian Journal of Mathematics, 10, 165–495 (2006).

- Guo, H.-X. An entropy formula relating Hamilton’s surface entropy and Perelman’s W-entropy. Comptes Rendus Mathématique, 351(3–4):115–118 (2013). [CrossRef]

- Li, X.-D. Perelman’s W-entropy for the Fokker–Planck equation over complete Riemannian manifolds. Bulletin des Sciences Mathématiques, 135, 871–882 (2011).

- Streets, J. Regularity and expanding entropy for connection Ricci flow. Journal of Geometry and Physics, 58(7), 900–912 (2008). [CrossRef]

- Ni, L. The entropy formula for linear heat equation. Journal of Geometric Analysis, 14(1), 87–100 (2004). [CrossRef]

- Vacaru, S. I. Geometric information flows and G. Perelman entropy for relativistic classical and quantum mechanical systems. arXiv:1905.12399 (2019).

- Vacaru, S. Off-diagonal cosmological solutions in emergent gravity theories and Grigory Perelman entropy for geometric flows. European Physical Journal C, 80, 98 (2020). [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y. On the equivalence between noncollapsing and bounded entropy for ancient solutions to the Ricci flow. Journal für die reine und angewandte Mathematik, 762, 89–130 (2020).

- Ambjørn, J., et al. Causal dynamical triangulation as a model of quantum gravity. Physics Letters B, 607, 205–213 (2005).

- Hollands, S., Wald, R. M. Quantum fields in curved spacetime. arXiv:1401.2026 (2014).

- Basu, A., et al. Shear dynamics in higher-dimensional FLRW cosmology. arXiv:1404.1878 (2014).

- Hamilton, R. S. Three-manifolds with positive Ricci curvature. Journal of Differential Geometry, 17, 255–306 (1982). [CrossRef]

- Hamilton, R. S. The Ricci flow on surfaces. Contemporary Mathematics, 71, 237–262 (1988).

- Morgan, J., Tian, G. Ricci Flow and the Poincaré Conjecture. Clay Mathematics Monographs, vol. 3, AMS (2007).

- Chow, B., Knopf, D. The Ricci Flow: An Introduction. Mathematical Surveys and Monographs, vol. 110, AMS (2004).

- Li, S., Li, X.-D. W-entropy formula for the Witten Laplacian on manifolds with time dependent metrics and potentials. Pacific Journal of Mathematics, 278(1), 173–199 (2015). [CrossRef]

- Vacaru, S. I., Bubuianu, L. Perelman’s W-entropy and statistical and relativistic thermodynamic description of gravitational fields. European Physical Journal C, 77, 184 (2017).

- Kuznetsov, V. A. An entropic analogue of Perelman’s theorem using the Kuznetsov tensor. Proceedings of Azerbaijan High Technical Education Institute, 54(06), Issue 05–02, 805–814 (2025). [CrossRef]

- Penrose, R. Cycles of Time: An Extraordinary New View of the Universe. Bodley Head (UK), Knopf (US) (2010).

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).