Submitted:

30 April 2025

Posted:

02 May 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

The concept of space-time has long been a cornerstone of physics, with Einstein’s theory of relativity defining gravity as the curvature of space-time due to mass. However, this research introduces an alternative perspective—Temporal Dynamics, where space remains structurally fixed, and gravity arises from variations in the flow of time. This framework proposes that time flows uniformly through space at a constant rate but is altered by the presence of mass, leading to gravitational effects. By redefining gravity as a consequence of time flow distortions rather than spatial curvature, this model provides new insights into gravitational acceleration, free-fall mechanics, and black hole dynamics. Through derived equations, the study successfully predicts gravitational acceleration for Earth and Mars, demonstrating the framework’s validity. It further explores gravitational lensing, black hole event horizons, and space-time singularities from a temporal flow perspective. The research challenges conventional understandings by suggesting that black holes do not collapse into singularities but instead accumulate mass at the event horizon, where time flow ceases. Additionally, the study introduces the concept of Temporal Dimensions, proposing that variations in time flow could exist as distinct dimensions, influencing our perception of reality. This Temporal Dynamics framework not only aligns with observed gravitational phenomena but also provides an alternative explanation for motion, relativity, and cosmic expansion. By shifting the focus from spatial curvature to time flow variations, this model opens new avenues for understanding gravity, space-time interactions, and potential applications in astrophysics and cosmology.

Keywords:

Introduction: The Evolution of Space-Time Concepts

- Hendrik Lorentz (1890s–1900s) – Developed transformations that suggested time and space are linked.

- Henri Poincaré (1900s) – Formulated early ideas of relativistic space-time.

- Albert Einstein (1905, 1915) – Established special and general relativity, demonstrating that time is relative and space-time is curved by mass.

- Hermann Minkowski (1908) – Introduced the mathematical formalism of space-time as a four-dimensional construct.

The Core Premise: A Fixed Space with Dynamic Time Flow

Beyond Uniformity: The Role of Mass and Chaos

The Nature of Mass in This Model

The Equation for Additional Time Introduced by Mass

- -

- ∆T= Additional time delay due to mass (s).

- -

- M = Mass of the object (kg).

- -

- Cm = Mass constant (2.970330587876230×10^-27 smkg^-1).

- -

- D = Distance influenced by mass (m).

Total Time Flow in the Presence of Mass

Gravity as a Consequence of Time Flow Variations

Next Steps: Motion in a Time-Based Gravity Model

Motion as a Consequence of Time Flow Changes

- D_motion = Total distance expanded in the direction of motion after one second

- D_expanded = Distance expanded due to normal time flow (299,792,458 m)

- V = Speed of the moving body

- C = Speed of light (299,792,458 m/s)

- T_normal = Time flow in absence of motion

- T_altered = Time flow altered by motion

How Gravity and Motion Are Connected

Gravity as a Continuous Time Flow Alteration

- If normal time flow slows by a factor of 2, the altered time flow becomes ½ of normal time.

- If it slows further by a factor of 2, it becomes ¼ of the original time flow.

- If it slows again, it becomes ⅛, then ¹/¹⁶, then ¹/32…

The Gravitational Acceleration Equation

- A = Gravitational acceleration

- C = Speed of light (299,792,458 m/s)

- Gravitational ratio = Ratio between normal time flow and actual time flow under gravity

Conclusion and Next Steps

- Motion occurs because time flows slower in the direction of movement, creating an effect similar to a “pull” forward.

- Gravity is essentially the same process but happens continuously, leading to acceleration rather than a constant velocity.

- This means both motion and gravity are consequences of time flow variations rather than space curvature.

Real-World Applications

Key Theoretical Equations and Their Meaning

- M = Mass (kg)

- C_m = Mass constant (2.970330587876230 × 10⁻²⁷ smkg⁻¹)

- D = Distance (m)

Applying the Framework to Real-World Cases

-

Step 1: Calculate the Additional Time Flow Due to Earth’s Mass

- ∆ t = (5.972 × 10^24) × (2.970330587876230 × 10^-27) ÷ 12,742,000

- ∆ t = 1.773 × 10^-2 ÷ 12,742,000

- ∆ t ≈ 1.3908 × 10^-9 s

-

Step 2: Compute the Total Time Flow of Space Influenced by Earth

- T_mass flow = ∆ t + (D × U)

- T_mass flow = 1.3908 × 10^-9 + (12,742,000 × 3.33564095 × 10^-9)

- T_mass flow = 1.3908 × 10^-9 + 0.04250273698

- T_mass flow ≈ 0.04250273837 s

-

Step 3: Compute the Gravitational Ratio

- G_ratio = 0.04250273698 ÷ 0.04250273837

- G_ratio ≈ 0.9999999673

-

Step 4: Compute Earth’s Gravitational Acceleration

- G = c – (g_ratio × D_expanded)

- G = 299,792,458 – (0.9999999673 × 299,792,458)

- G b>G ≈ 9.81 ms²

Case Study 2: Mars’ Gravity

-

Step 1: Calculate Additional Time Flow Due to Mars’ Mass

- ∆ t = (6.4171 × 10^23) × (2.970330587876230 × 10^-27) ÷ 6,792,000

- ∆ t ≈ 2.805 × 10^-10 s ]

-

Step 2: Compute Mars’ Total Time Flow

- T_mass flow = 2.805 × 10^-10 + (6,792,000 × 3.33564095 × 10^-9)

- T_mass flow = 2.805 × 10^-10 + 0.02265

- T_mass flow ≈ 0.0226500003 s

-

Step 3: Compute Mars’ Gravitational Ratio

- G_ratio = 0.02265 ÷ 0.0226500003

- G_ratio ≈ 0.9999999876

-

Step 4: Compute Mars’ Gravitational Acceleration

- G = 299,792,458 – (0.9999999876 × 299,792,458)

- G b>G ≈ 3.7 ms²

Conclusion

- Mass slows time flow, creating gravitational attraction.

- Motion occurs due to changes in time flow gradients.

- Gravitational acceleration is derived purely from time flow alterations.

Derivation of the Mass Constant (Cₘ) in the Temporal Dynamics Framework

- Δt = Additional time flow distortion due to mass (s)

- M = Mass of the object (kg)

- Cₘ = Mass constant (smkg⁻¹)

- D = Distance influenced by mass (m) (e.g., the diameter of a planet)

- G = Gravitational acceleration (ms²)

- C = Speed of light (299,792,458 m/s)

- G_ratio = Gravitational ratio, defined as:

- G_ratio = T_normal ÷ T_mass flow

- D_expanded = Distance expanded by space in one second (299,792,458 m)

-

Step 3: Solve for the Mass Constant (Cₘ)

- We apply this equation to Earth, using known values:

- Mass of Earth (Mₑ) = 5.972 × 10²⁴ kg

- Diameter of Earth (Dₑ) = 12,742,000 m

- Gravitational acceleration (gₑ) = 9.81 ms²

- Speed of light (c) = 299,792,458 m/s

- Total distance expanded after 1 second (D_expanded) = 299,792,458 m

- First, solve for g_ratio:

- G_ratio = (c – g) ÷ D_expanded

- G_ratio = (299,792,458 – 9.81) ÷ 299,792,458

- G_ratio ≈ 0.9999999673

- Using the definition of g_ratio:

- G_ratio = T_normal ÷ T_normal + ∆ t

- Rearrange for Δt:

- ∆ t = T_normal ÷ g_ratio – T_normal

- ∆ t = (0.04250273698 ÷ 0.9999999673) – 0.04250273698

- ∆ t ≈ 1.3908 × 10^-9 s

- Now, solve for Cₘ using:

- Mₑ × C_m ÷ Dₑ = ∆ t

- C_m =( ∆ t × Dₑ) ÷ Mₑ

- C_m = (1.3908 × 10^-9) × (12,742,000)÷(5.972 × 10^24)

- C_m ≈ 2.970330587876230 × 10^-27 s m kg^-1

-

Step 4: Validate with Other Celestial Bodies (Mars)

- For Mars:

- Mass of Mars (Mₘ) = 6.4171 × 10²³ kg

- Diameter of Mars (Dₘ) = 6,792,000 m

- Gravitational acceleration (gₘ) = 3.7 ms²

- Following the same process, we calculate:

- G_ratio ≈ 0.9999999876

- ∆ t ≈ 2.805 × 10^-10 s

- C_m = (2.805 × 10^-10) × (6,792,000) ÷ (6.4171 × 10^23)

- C_m ≈ 2.970330587876230 × 10^-27 s m kg^-1

Conclusion

- The mass constant (Cₘ) was derived using:

- The relationship between mass, time flow, and distance.

- Empirical validation using Earth’s and Mars’ known gravitational acceleration.

- Consistency across different planetary bodies.

- Final Derived Value of the Mass Constant:

Explaining Why Bodies of Different Mass Fall at the Same Rate Using the Temporal Dynamics Framework

- C = Speed of light

- G_ratio = Ratio of normal time flow to time flow altered by Earth’s mass

- D_expanded = Distance space expands in one second (299,792,458 m)

Why Mass Doesn’t Affect Free Fall in This Model

Mathematical Explanation

Comparison with Einstein’s Model

Experimental Validation: The Apollo 15 Hammer-Feather Test

- The hammer and feather both exist within the same time flow gradient created by the Moon’s mass.

- Since gravity is just a function of time flow variation, both objects move at the same rate, regardless of their different masses.

- The experimental results are naturally explained by this framework.

Conclusion

- Gravity is not a force, but a response to gradients in time flow.

- All objects in the same time flow gradient experience the same gravitational acceleration.

- This naturally explains why objects of different masses fall at the same rate on Earth’s surface.

Complex Gravitational Temporal Dynamics: A New Framework for Gravity and Time Flow

Gravitational Time Change: Mass as Frozen Time

- ΔT represents the additional time introduced by mass,

- M is the mass of the gravitational body (kg),

- M_c is the mass constant, and

- D is the distance occupied by the mass.

Gravitational Acceleration

Gravitational Acceleration Ratio

- T_normal represents normal time flow in the absence of mass,

- ΔT accounts for additional time due to gravitational influence.

- G_a is gravitational acceleration,

- D represents the distance expanded after one second (299,792,458 meters),

- C is the speed of light, and

- Gr is the gravitational ratio.

Implications of Gravitational Acceleration

Gravitational Speed

- T_mass = T_normal + ΔT

Constraints on Gravitational Speed

Gravitational Lensing and Black Hole Event Horizon Formation: A Temporal Dynamics Approach

Gravitational Angle of Deviation (Gravitational Lensing)

The Equation for Photon Deviation Due to Gravity

- T_normal is the normal time required for light to travel a given distance.

- G_a represents gravitational acceleration.

- Uc is the universal time-flow constant.

The Relationship Between Light, Gravity, and Time Flow

Derivation of the Deviation Angle

Interpretation of the Angle of Deviation

Black Holes and Event Horizon Formation

How the Event Horizon Forms

Implications for the Collapsing Mass in Black Holes and the Nature of Space Pockets Inside the Event Horizon

The Stopping Point of a Collapsing Mass in a Black Hole

The State of Mass Inside the Event Horizon

Why Mass Does Not Collapse Into a Singularity

Why Light Appears “Frozen” at the Event Horizon

Space Pockets Inside the Event Horizon: The Concept of Energy Pockets

How Space Pockets Form Inside the Event Horizon

How Space Pockets Contribute to Hawking Radiation

The Process of Energy Release from Space Pockets

- Trapped light and energy exist in space pockets where time is paused.

- Mass accretion expands the event horizon, shifting the boundaries of trapped energy pockets.

- Some trapped energy may interact with newly accreted mass, leading to partial conversion into radiation.

- As some of these energy pockets fall outside the event horizon, their contents may escape, producing Hawking radiation.

Conclusion: The Event Horizon as a Dynamic Structure

- Mass stops collapsing, accumulating at the boundary.

- Light is effectively frozen, appearing motionless due to the absence of time progression.

- Energy pockets within the event horizon hold trapped light, which may later be released as radiation when the event horizon changes.

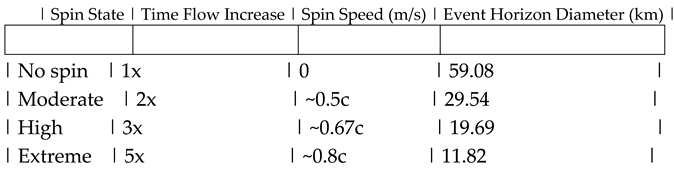

Rethinking Black Hole Spin Using Temporal Dynamics

Introduction

Event Horizon Formation in Temporal Dynamics

Effects of Spin on Time Flow and the Event Horizon

- Near the event horizon: Spin increases the local time flow, effectively reducing ∆T below 1. This pushes the event horizon deeper inside.

- Farther from the black hole: Spin slows the time flow further, increasing gravitational complexity.

No Singularity Formation

Mass-Energy Feedback and Horizon Shrinkage

Key Equations and Physical Meaning

-

Altered Time Flow

- -

- Equation: Altered time flow = (Diameter × 3.33564095 × 10^-9) + ∆T

- -

- Purpose: Calculates the total linear time flow across the black hole, combining geometry and gravitational distortion.

-

Spin Speed

- -

- Equation: Spin Speed = c – ((altered time flow × 299,792,458) ÷ new altered time flow)

- -

- Purpose: Derives the apparent rotational speed due to a change in time flow caused by spin.

-

Event Horizon Diameter from Mass

- -

- Equation: Mass × 2.970330587876230031748161313565 × 10^-27 = Diameter

- -

- Purpose: Converts black hole mass into an initial event horizon diameter based on temporal distortion constants.

-

New Event Horizon with Spin

- -

- Equation: New Event Horizon = ((Diameter × 3.33564095 × 10^-9) × (altered time flow ÷ new altered time flow)) ÷ 3.33564095 × 10^-9

- -

- Purpose: Adjusts the event horizon inward to account for time flow changes induced by spin.

-

Alternative Expression for New Event Horizon

- -

- Equation: New Event Horizon = Diameter × ((c – spin speed) ÷ c)

- -

- Purpose: Provides a simplified way to calculate the new event horizon using the relative reduction in effective speed caused by spin.

Simulation: 10 Solar Mass Black Hole

Worked Example (2x Time Flow Increase)

- Mass = 10 × 1.989 × 10^30 = 1.989 × 10^31 kg

- Diameter = 1.989 × 10^31 × 2.97033058787623 × 10^-27 = ~59,079.88 m

- Altered Time Flow = (59,079.88 × 3.33564095 × 10^-9) + 1 = ~1.000197 s

- New Time Flow = 2 × 1.000197 = ~2.000394 s

- Spin Speed = 299,792,458 – ((1.000197 × 299,792,458) ÷ 2.000394) = ~149,896,234 m/s

- New Horizon = ((59,079.88 × 3.33564095 × 10^-9) × (1.000197 ÷ 2.000394)) ÷ 3.33564095 × 10^-9 = ~29,539.94 m (~29.54 km)

- Alternatively, New Horizon = 59,079.88 × ((299,792,458 – 149,896,234) ÷ 299,792,458) ≈ 29,539.94 m

Conclusion

- An inward shift of the event horizon,

- A natural avoidance of singularities,

- More complex gravitational behavior,

- Potential mass-energy conversion through spin.

Temporal Dimensions and Variations in Time Flow

-

Understanding Temporal Dimensions:

- -

- Temporal dimensions can be thought of as distinct realms where time flows differently, each characterized by its own specific rate of temporal progression. While we perceive time as a single linear flow, there exists the possibility of multiple temporal dimensions where time behaves in unique ways.

-

Universal Constants and Time Flow:

- -

- The universal speed of light (denoted as c = 299,792,458 meters per second) serves as a fundamental constant in our understanding of the universe. By expressing time flow in terms of universal constants, we can formulate a relationship: uc = {1}÷{299,792,458}. This relationship implies that different temporal dimensions can be defined by distinct values of universal constants. Each unique constant influences how time flows, creating a varied temporal dynamic that sets these dimensions apart from one another.

-

Separation of Temporal Dimensions:

- -

- Each temporal dimension operates independently, with its own fabric of time that does not necessarily interact with or relate to other temporal dimensions. For instance, if one temporal dimension has a flow where one second equals two seconds in our perception, then entities existing in this dimension would experience time distinctly, leading to unique physical and causal relationships.

-

Existence of Other Temporal Realms:

- -

- Just as there are multiple spatial dimensions—potentially more than the three we observe—there could be temporal dimensions that coexist alongside our own. These dimensions are just as real as our conventional perception of time, but they exist in isolation from our experiential framework, governed by their own rules and constants.

-

Implications for Physics and Cosmology:

- -

- The notion of multiple temporal dimensions raises intriguing questions about the nature of reality, causality, and the structure of the universe. It challenges our foundational understanding of physics and could offer insights into phenomena that seem paradoxical or unexplained within the confines of our four-dimensional space-time model.

Conclusions & Future Work

- Gravity results from time flow variations, not space-time curvature.

- Mass slows time flow, creating gravitational acceleration.

- Objects of different masses fall at the same rate because they experience the same local time-flow gradient.

- Black holes do not collapse into singularities but grow outward as mass accumulates at the event horizon.

- Temporal dimensions could redefine our understanding of space-time interactions.

- Experimental Validation: Future work should explore precise time-flow measurements around massive bodies, testing whether gravitational acceleration can be directly correlated to time-flow variations rather than space-time curvature.

- Astronomical Observations: Studying black hole event horizons with high-resolution imaging could provide evidence for the accumulation model over singularity formation.

- Implications for Cosmic Expansion: Investigating whether time flow variations influence cosmic expansion could refine our understanding of dark energy.

- Mathematical Extensions: Further derivations are needed to unify this framework with existing relativistic and quantum theories, particularly regarding time-flow variations at microscopic scales.

Conflicts of Interest

AI Disclosure Statement

- Drafting and Refinement – Assisting in structuring the manuscript, enhancing clarity, and improving coherence in explanations related to temporal dynamics, space-time, and gravity.

- Mathematical Formatting – Converting equations into linear text for readability and consistency with formatting guidelines.

- Reference Compilation – Generating APA-style citations based on key sources in gravitational physics, space-time theory, and black hole dynamics.

- Abstract and Summary Generation – Assisting in the development of an engaging abstract and structured conclusions.

References

- Einstein, A. The foundation of the general theory of relativity. Annalen der Physik 1916, 49(7), 769–822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Newton, I. Philosophiæ Naturalis Principia Mathematica [Mathematical principles of natural philosophy]; Royal Society, 1687. [Google Scholar]

- Hawking, S. W. Particle creation by black holes. Communications in Mathematical Physics 1975, 43(3), 199–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bekenstein, J. D. Black holes and entropy. Physical Review D 1973, 7(8), 2333–2346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwarzschild, K. On the gravitational field of a mass point according to Einstein’s theory. Sitzungsberichte der Königlich Preußischen Akademie der Wissenschaften 1916, 189–196. [Google Scholar]

- Wald, R. M. General relativity; University of Chicago Press, 1984. [Google Scholar]

- Thorne, K.S. Black holes and Time Warps: Einstein’s Outrageous Legacy; W. W. Norton & Company, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Carroll, S.M. Spacetime and Geometry: An Introduction to General Relativity; Addison-Wesley, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Francis, O.O. Essence dynamics: Essence interactions, applications and Reality. Part I. Preprints 2024, 2024082057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).