Submitted:

03 July 2025

Posted:

04 July 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Patients and Bacterial Isolates

2.2. Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing

2.3. Phenotypic Detection of β-Lactamases

2.4. Molecular Detection of Resistance Genes

2.5. CarbaResist Inter-Array Genotyping Kit

2.6. Whole Genome Sequencing (WGS)

2.7. Characterization of Plasmids

2.8. Detection of Virulence Determinants

2.9. Genotyping

3. Results

3.1. Patients and Bacterial Isolates

3.2. Antibiotic Susceptibility

3.3. Phenotypic Detection of β-Lactamases

3.4. Molecular Detection of Resistance Genes

3.5. Genotpying by Interarray CarbaResist Kit

| Isolate and Protocol Number | Res phenotype | β-Lactam | Aminoglycoside | sulphonami | trimethoprim | Integrase genes |

| PM 2 | AMX, AMC, TZP, CAZ,CTX, CRO, FEP, GM,AMI CIP |

ISEcpblaCTX-M-15 blaTEM blaVIM |

aac(6′’)IIc aadA1 aadA2 armA |

sul1 |

dfrA1 |

Intl2 |

| PM 3 | AMX, AMC, TZP, CAZ,CTX, CRO, FEP, GM,AMI CIP |

ISEcpblaCTX-M-15 blaCMY blaTEM blaVIM |

aac(6′’)IIc aadA1 aadA2 armA |

sul1 sul2 |

dfrA1 |

Intl1 Intl2 |

|

PM4 |

AMX, AMC, TZP, CAZ,CTX, CRO, FEP, GM,AMI CIP |

ISEcpblaCTX-M-15 blaTEM blaVIM |

aac(6′’)IIc aadA1 aadA2 armA |

sul1 sul2 |

dfrA1 dfrA15 |

Intl1 Intl2 |

| PM11 | AMX, AMC, TZP, CAZ,CTX, CRO, FEP, GM,AMI CIP |

ISEcpblaCTX-M-15 blaTEM blaVIM |

aac(6′’)IIc aadA1 aadA2 armA |

sul1 sul2 |

dfrA1 |

Intl1 Intl2 |

| PM14 | AMX, AMC, TZP, CAZ,CTX, CRO, FEP, GM,AMI CIP |

ISEcpblaCTX-M-15 blaTEM blaVIM |

aac(6′’)IIc aadA1 aadA2 armA |

sul1 sul2 |

dfrA1 |

Intl1 Intl2 |

| PM 19 | AMX, AMC, TZP, CAZ,CTX, CRO, FEP, GM,AMI CIP |

ISEcpblaCTX-M-15 blaTEM blaVIM |

aac(6′’)IIc aadA1 aadA2 armA |

sul1 sul2 |

dfrA1 |

Intl1 Intl2 |

| PM 20 | AMX, AMC, TZP, CAZ,CTX, CRO, FEP, GM,AMI CIP |

ISEcpblaCTX-M-15 blaTEM blaVIM |

aac(6′’)IIc aadA1 aadA2 armA |

sul1 sul2 |

dfrA1 |

Intl1 Intl2 |

3.6. WGS

3.7. Plasmid Analysis

3.8. Detection of Virulence Determinants

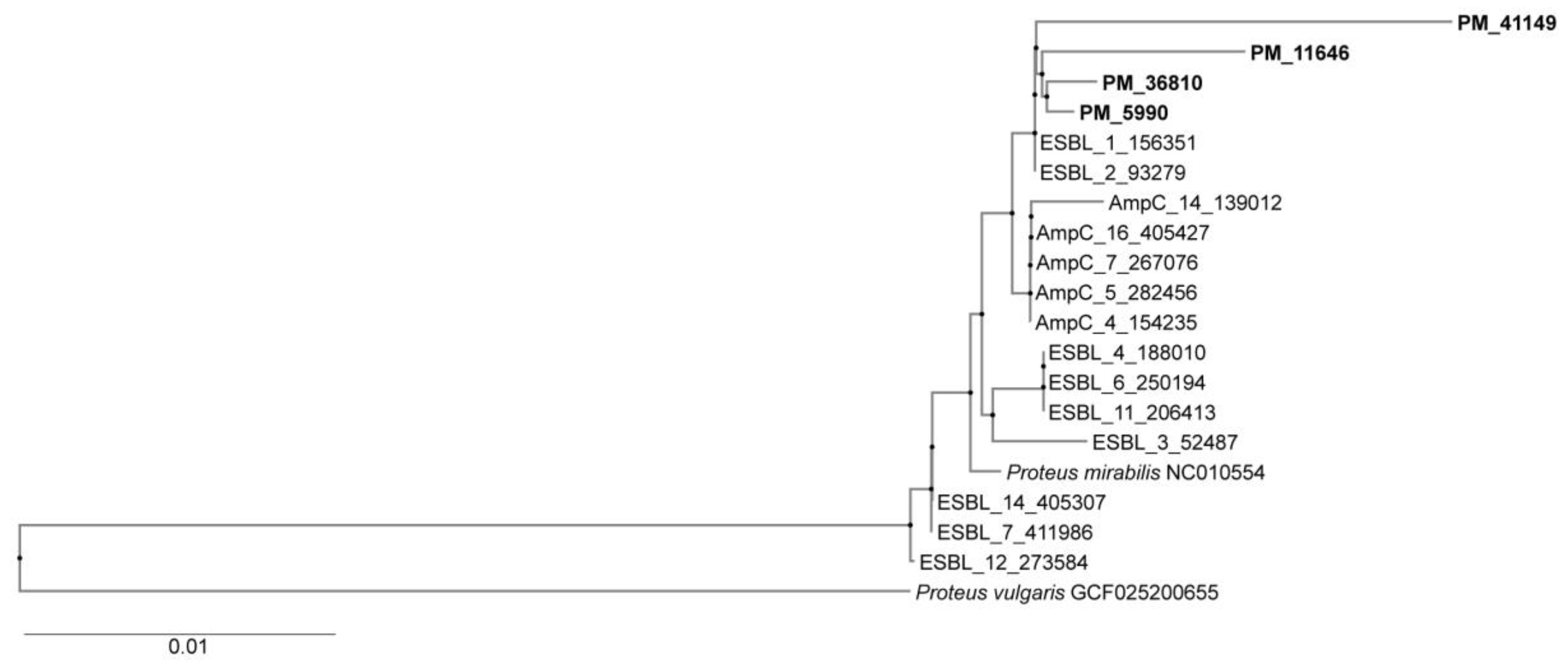

3.9. Genotyping

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Sanches, M.S.; Silva, L.C.; Silva, C.R.D.; Montini, V.H.; Oliva, B.H.D.; Guidone, G.H.M.; Nogueira, M.C.L.; Menck-Costa, M.F.; Kobayashi, R.K.T.; Vespero, E.C.; Rocha, S.P.D. Prevalence of Antimicrobial Resistance and Clonal Relationship in ESBL/AmpC-Producing Proteus mirabilis Isolated from Meat Products and Community-Acquired Urinary Tract Infection (UTI-CA) in Southern Brazil. Antibiotics (Basel). 2023, 2023 10, 370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Yin, M.; Fang, C.; Fu, Y.; Dai, X.; Zeng, W.; Zhang, L. Genetic analysis of resistance and virulence characteristics of clinical multidrug-resistant Proteus mirabilis isolates. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 2023, 11, 1229194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Girlich, D.; Bonnin, R.A.; Dortet, L.; Naas, T. Genetics of Acquired Antibiotic Resistance Genes in Proteus spp. Front Microbiol. Front Microbiol. 2020, 21, 256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paterson, D.L.; Bonomo, R.A. Extended-spectrum β-lactamases: A clinical update. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 2005, 18, 657–686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cantón, R.; Coque, T.M. The CTX-M β-lactamase pandemic. Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 2006, 9, 466–475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jacoby, G.A. AmpC β-lactamases. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2009, 22, 161–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Potter RF, D'Souza AW, Dantas G. The rapid spread of carbapenem-resistant Enterobacteriaceae. Drug Resist Updat. 2016, 29, 30–46. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Sardelić, S.; Bedenić, B.; Sijak, D.; Colinon, C.; Kalenić, S. Emergence of Proteus mirabilis isolates producing TEM-52 extended-spectrum β-lactamases in Croatia. Chemotherapy. 2010, 56, 208–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tonkić, M.; Mohar, B.; Šiško-Kraljević, K.; Meško-Meglič, K.; Goić-Barišić, I.; Novak, A.; Kovačić, A.; Punda-Polić, V. High prevalence and molecular characterization of extended-spectrum β-lactamase-producing Proteus mirabilis strains in southern Croatia. J Med Microbiol. 2010, 59, 1185–1190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bedenić, B.; Firis, N.; Elveđi-Gašparović, V.; Krilanović, M.; Matanović, K.; Štimac, I.; Luxner, J.; Vraneš, J.; Meštrović, T.; Zarfel, G.; Grisold, A. Emergence of multidrug-resistant Proteus mirabilis in a long-term care facility in Croatia. Wien Klin Wochenschr. 2016, 128, 404–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rubić, Z.; Soprek, S.; Jelić, M.; Novak, A.; Goić-Barisić, I.; Radić, M.; Tambić-Andrasević, A.; Tonkić, M. Molecular Characterization of β-Lactam Resistance and Antimicrobial Susceptibility to Possible Therapeutic Options of AmpC-Producing Multidrug-Resistant Proteus mirabilis in a University Hospital of Split, Croatia. Microb Drug Resist. 2021, 27, 162–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- European Committee for Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing. Breakpoint Tables for Interpretation of MICs and Zone Diameters. Version 12. 2022. Available online: http://www.eucast.org (accessed on 1st October 2023).

- Clinical Laboratory Standard Institution. Performance Standards for Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing, 28th ed.; Approved Standard M100-S22; Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute: Wayne, PA, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Magiorakos, A.P.; Srinivasan, A.; Carey, R.B.; Carmeli, Y.; Falagas, M.E.; Giske, C.G.; Harbarth, S; Hindler, J.F; Kahlmeter, G; Olsson-Liljequist, B; Paterson, D.L; Rice, L.B; Stelling J.; Struelens, M.J.; Vatopoulos, A.; Weber, J.T.; Monnet, D. Multidrug-resistant, extensively drug-resistant and pandrug-resistant bacteria: An international expert proposal for interim standard definitions for acquired resistance. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 2002, 18, 268–281. [CrossRef]

- Jarlier, V.; Nicolas, M.H.; Fournier, G.; Philippon, A. Extended broad-spectrum beta-lactamases conferring transferable resistance to newer beta-lactam agents in Enterobacteriaceae: hospital prevalence and susceptibility patterns. Rev Infect Dis. 1988, 10, 867–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacDonald, J.W.; Chibabhai, V. Evaluation of the RESIST-4 O.K.N.V Immunochromatographic Lateral Flow Assay for the Rapid Detection of OXA-48, KPC, NDM and VIM Carbapenemases from Cultured Isolates. Access Microbiol. 2019, 1, e000031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, K.; Lim, Y.S.; Yong, D.; Yum, J.H.; Chong, Y. Evaluation of the Hodge Test and the Imipenem-EDTA-double-disk Synergy Test for Differentiating Metallo-β-lactamase-producing Isolates of Pseudomonas spp. and Acinetobacter spp. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2003, 41, 4623–4629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- CLSI. Performance Standards for Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing, M100, 31st ed.; Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute: Wayne, PA, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Arlet, G.; Brami, G.; Decre, D.; Flippo, A.; Gaillot, O.; Lagrange, P.H.; Philippon, A. Molecular characterization by PCR restriction fragment polymorphism of TEM β-lactamases. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 1995, 134, 203–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nüesch-Inderbinen, M.T.; Hächler, H.; Kayser, F.H. Detection of genes coding for extended-spectrum SHV β-lactamases in clinical isolates by a molecular genetic method, and comparison with the E test. Eur. J. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 1996, 15, 398–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Woodford, N.; Ward, M.E.; Kaufmann, M.E.; Turton, J.; Fagan, E.J.; James, D.; Johnson, A.P.; Pike, R.; Warner, M.; Cheasty, T.; Pearson, A.; Harry, S.; Leach, J.B; Loughrey, A.; Lowes, J.A.; Warren, R.E.; Livermore, D.M. Community and hospital spread of Escherichia coli producing CTX-M extended-spectrum β-lactamases in the UK. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2004, 54, 735–743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Robicsek, A.; Jacoby, G.A.; Hooper, D.C. The worldwide emergence of plasmid-mediated quinolone resistance. Lancet Infect. Dis. 2006, 6, 629–640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poirel, L.; Walsh, T.R.; Cuveiller, V.; Nordman, P. Multiplex PCR for Detection of Acquired Carbapenemases Genes. Diagn. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 2011, 70, 119–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woodford, N. , Ellington, M. J; Coelho, J; Turton, J; Ward, M.E.; Brown, S; Amyes S.G; Livermore, D.M.. Multiplex PCR for genes encoding prevalent OXA carbapenemases. Int. J. Antimicrob. Agents. 2006, 27, 351–353. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Perez-Perez, F.J.; Hanson, N.D. Detection of plasmid-mediated AmpC β-lactamase genes in clinical isolates by using multiplex PCR. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2002, 40, 2153–2162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woodford, N.; Fagan, E.J.; Ellington, M.J. Multiplex PCR for rapid detection of genes encoding CTX-M extended-spectrum β-lactamases. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2006, 57, 154–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saladin, M.; Cao, V.T.B.; Lambert, T.; Donay, J.L.; Hermann, J.; Ould-Hocine, L. Diversity of CTX-M β-lactamases and Their Promoter Regions from Enterobacteriaceae Isolated in Three Parisian Hospitals. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 2002, 209, 161–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zankari, E.; Hasman, H.; Cosentino, S.; Vestergaard, M.; Rasmussen, S.; Lund, O.; Aarestrup, F.M.; Larsen, M.V. Identification of acquired antimicrobial resistance genes. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2012, 67, 2640–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carattoli, A.; Bertini, A.; Villa, L.; Falbo, V.; Hopkins, K.L.; Threfall, E.J. Identification of plasmids by PCR-based replicon typing. J Microbiol Methods. 2005, 63, 219–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carattoli, A.; Seiffert, S.N.; Schwendener, S.; Perreten, V.; Endimiani, A. Differentiation of IncL and IncM Plasmids Associated with the Spread of Clinically Relevant Antimicrobial Resistance. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0123063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaaban, M.; Elshaer, S.L.; Abd El-Rahman, O.A. Prevalence of extended-spectrum β-lactamases, AmpC, and carbapenemases in Proteus mirabilis clinical isolates. BMC Microbiol. 2022, 11, 247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miriagou, V; Papagiannitsis, C. C; Tzelepi, E; Casals, J.B; Legakis, N.J; Tzouvelekis, L.S. Detecting VIM-1 production in Proteus mirabilis by an imipenem-dipicolinic acid double disk synergy test. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2010, 48, 667–8. [CrossRef]

- Papagiannitsis, C. C; Miriagou, V; Kotsakis, S. D; Tzelepi, E; Vatopoulos, A.C; Petinaki, E; Tzouvelekis,.LS. Characterization of a transmissible plasmid encoding VEB-1 and VIM-1 in Proteus mirabilis. Antimicrob. Agents. Chemother. 2012, 56, 4024–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Protonotariou E, Poulou A, Politi L, Meletis G, Chatzopoulou F, Malousi A, Metallidis S, Tsakris A, Skoura L. Clonal outbreak caused by VIM-4-producing Proteus mirabilis in a Greek tertiary-care hospital. Int J Antimicrob Agents. Int J Antimicrob Agents. 2020, 56, 106060. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Markovska R, Schneider I, Keuleyan E, Ivanova D, Lesseva M, Stoeva T, Sredkova M, Bauernfeind A, Mitov I. Dissemination of a Multidrug-Resistant VIM-1- and CMY-99-Producing Proteus mirabilis Clone in Bulgaria. Microb Drug Resist. 2017, 23, 345–350. [CrossRef]

- Fritzenwanker, M; Falgenhauer, J; Hain, T; Imirzalioglu, C; Chakraborty T, Yao, Y. The Detection of Extensively Drug-Resistant Proteus mirabilis Strains Harboring Both VIM-; and VIM-75 Metallo-β-Lactamases from Patients in Germany. Microorganisms. 2025 25, 266. [CrossRef]

- Sattler, J.; Noster, J.; Stelzer, Y.; Spille, M.; Schäfer, S.; Xanthopoulou, K.; Sommer, J.; Jantsch, J.; Peter, S.; Göttig, S.; et al. OXA-48-like carbapenemases in Proteus mirabilis—Novel genetic environments and a challenge for detection. Emerg. Microbes. Infect. 2024, 13, 2353310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Potron, A.; Hocquet, D.; Triponney, P.; Plésiat, P.; Bertrand, X.; Valot, B. Carbapenem-Susceptible OXA-23-Producing Proteus mirabilis in the French Community. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2019, 63, e00191–e19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonnin, R.A.; Girlich, D.; Jousset, A.B.; Gauthier, L.; Cuzon, G.; Bogaerts, P. A single Proteus mirabilis lineage from human and animal sources: A hidden reservoir of OXA-23 or OXA-58 carbapenemases in Enterobacterales. Sci Rep. 2020, 8, 9160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bedenić, B; Sardelić, S; Luxner, J; Bošnjak, Z; Varda-Brkić, D; Lukić-Grlić, A; Mareković, I; Frančula-Zaninović, S; Krilanović, M; Šijak, D; Grisold, A; Zarfel, G. Molecular characterization of clas B carbapenemases in advanced stage of dissemination and emergence of class D carbapenemases in Enterobacteriaceae from Croatia. Infect Genetic Evol 2016,. 43,74-82. Doi10.1016.

- Literacka, E.; Bedenic, B.; Baraniak, A. ; Fiett, J; Tonkic, M. ; Jajic-Bencic, I.; Gniadkowski, M. blaCTX-M genes in Escherichia coli strains from Croatian Hospitals are located in new (blaCTX-M-3a) and widely spread (blaCTX-M-3a and blaCTX-M-15) genetic structures. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2009, 53, 1630–1635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Car, H.; Dobrić, M.; Pospišil, M.; Nađ, M.; Luxner, J.; Zarfel, G.; Grisold, A.; Nikić-Hecer, A.; Vraneš, J.; Bedenić, B. Comparison of Carbapenemases and Extended-Spectrum β-Lactamases and Resistance Phenotypes in Hospital- and Community-Acquired Isolates of Klebsiella pneumoniae from Croatia. Microorganisms 2024, 2, 2224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bedenić, B; Luxner, J; Zarfel, G; Grisold, A; Dobrić, M; Đuras-Cuculić, B; Kasalo, M; Bratić, V; Dobretzberger, V; Barišić, I. First Report of CTX-M-32 and CTX-M-101 in Proteus mirabilis from Zagreb, Croatia. Antibiotic, 2025, 30, 462. [CrossRef]

- Miriagou, V; Papagiannitsis, C. C; Tzelepi, E; Casals, J.B; Legakis, N.J, Tzouvelekis, L.S. Detecting VIM-1 production in Proteus mirabilis by an imipenem-dipicolinic acid double disk synergy test. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2010, 48, 667–8. [CrossRef]

| AMX 32 |

AMC 32/16 |

TZP 128/4 |

CXM 32 |

CAZ 16 |

CTX 4 |

CRO 4 |

FEP 16 |

IMI 4 |

MEM 4 |

GM 16 |

CIP 0,25 |

|

| 1 | >128 (R) | 32/16(R) | 8/4 (S) | >128(R) | 8 (R) | >128(R) | >128(R) | 16(R) | 128 (R) | 0,25(S) | >128(R) | >128(R) |

| 2 | >128 (R) | 64/32(R) | 8/4 (S) | >128(R) | 16(R) | >128(R) | >128(R) | >128(R) |

128 R) | 0,25(S) | >128(R) | >128(R) |

| 3 | >128 (R) | 64/32(R) | 8/4(S) | >128(R) | 8 (R) | >128(R) | >128(R) | >128(R) | 128 (R) | 0,25(S) | >128(R) | >128(R) |

| 4 | >128 (R) | 128/64(R) | 8/4(S) | >128(R) | 2 (I) | >128(R) | >128(R) | >128(R) | 128 (R) | 0,25(S) | >128(R) | >128(R) |

| 5 | >128 (R) | 32/16(R) | 16/4 (S) | >128(R) | 2 (I) | >128(R) | >128(R) | >128(R) | 4 (R) | 0,12 S) | >128(R) | >128(R) |

| 6 | >128 (R) | 32/16(R) | 16/4(S) | >128(R) | 8(R) | >128(R) | >128(R) | >128(R) | 4 (R) | 0,25(S) | >128(R) | >128(R) |

| 7 | >128 (R) | 128/64(R) | 8/4 (S) | >128(R) | 8(R) | >128(R) | >128(R) | >128(R) | 4 (R) | 0,5 (S) | >128(R) | >128(R) |

| 8 | >128 (R) | 128/64(R) | 8/4 (S) | >128(R) | 16(R) | >128(R) | >128(R) | >128(R) | 8 (R) | 0,25(S) | >128(R) | >128(R) |

| 9 | >128 (R) | 128/64(R) | 8/4 (S) | >128(R) | 16(R) | >128(R) | >128(R) | >128(R) | 4 (R) | 0,25(S) | >128(R) | >128(R) |

| 10 | >128 (R) | 128/64(R) | 8/4 (S) | >128(R) | 32(R) | >128(R) | 32(R) | >128(R) | 4 (R) | 0,12 S) | >128(R) | >128(R) |

| 11 | >128 (R) | 128/64(R) | 8/4 (S) | >128(R) | 128(R) | >128(R) | 32(R) | >128(R) | 4 (R) | 0,25(S) | >128(R) | >128(R) |

| 12 | >128 (R) | 128/64(R) | 16/4(S) | >128(R) | 2(I) | >128(R) | >128(R) | >128(R) | 8 (R) | 0,25(S) | >128(R) | >128(R) |

| 13 | >128 (R) | 128/64(R) | 8/4 (S) | >128(R) | 32(R) | >128(R) | 32(R) | >128(R) | 8 (R) | 0,5 (S) | >128(R) | >128(R) |

| 14 | >128 (R) | 128/64(R) | 16/4(S) | >128(R) | 128(R) | >128(R) | 16((R) | >128(R) | 4 (R) | 0,5 (S) | >128(R) | >128(R) |

| 15 | >128 (R) | 128/64(R) | 8/4 (S) | >128(R) | 32(R | >128(R) | 16(R) | >128(R) | 4 (R) | 0,25(S) | >128(R) | >128(R) |

| 16 | >128 (R) | 128/64(R) | 16/4(S) | >128(R) | 128(R) | >128(R) | 128(R) | >128(R) | 4 (R) | 0,12 S) | >128(R) | >128(R) |

| 17 | >128 (R) | 64/32(R) | 16/4(S) | >128(R) | 16(R) | >128(R) | 32(R) | >128(R) | 8 (R) | 0,06 (S) | >128(R) | >128(R) |

| 18 | >128 (R) | 128/64(R) | 8/4 (S) | >128(R) | 64(R) | >128(R) | 64(R) | >128(R) | 4 (R) | 0,25(S) | >128(R) | >128(R) |

| 19 | >128 (R) | 128/64(R) | 8/4 (S) | >128(R) | 64(R) | >128(R) | 32(R) | >128(R) | 4 (R) | 0,25(S) | >128(R) | >128(R) |

| 20 | >128 (R) | 64/32(R) | 16/4(S) | >128(R) | 64(R) | >128(R) | 128(R) | >128(R) | 4 (R) | 0,5 (S) | >128(R) | >128(R) |

|

Isolate and Protocol Number |

β-Lactam | Aminoglycosides | Sulphonamide | Trimethoprim | Chloramphenicol | Tetracycline |

| PM 3 | blaCTX-M-202, blaTEM-156, blaTEM-1A, blaTEM-2, blaVIM-4, blaVIM-1, | aac(3)-IId, aph(6)-Id, aph(3'')-Ib, aadA1, armA, aac(6')-IIc, |

sul1 sul2 |

dfrA1 | cat | tet(J) |

| PM 5 | blaCTX-M-202 blaTEM-2, blaTEM-1A, blaVIM-4 | aac(3)-IId, aph(6)-Id, aph(3'')-Ib, aadA1, armA, aac(6')-IIc, |

sul1 sul2 |

dfrA1 | cat | tet(J) |

| PM 6 | blaCTX-M-202 blaTEM-2, , blaVIM--4, | aph(6)-Id, aph(3'')-Ib, armA, aac(6')-IIc, aac(3)-IId, aac(6')-IIc, aadA1 |

sul1 sul2 |

dfrA1 | cat | tet(J) |

| PM 8 | blaCTX-M-202, blaTEM-2, blaTEM-1A, blaVIM-1, blaVIM-4, | aac(3)-IId, aph(6)-Id, aph(3'')-Ib, aadA1, armA, aac(6')-IIc, |

sul1 sul2 |

dfrA1 |

cat | tet(J) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).