Submitted:

14 April 2025

Posted:

15 April 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Results

2.1. Epidemiological and Clinical Characteristics of the P. mirabilis Outbreak

2.2. Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing (AST) and Carbapenemase Detection

2.3. Clonal Relationship

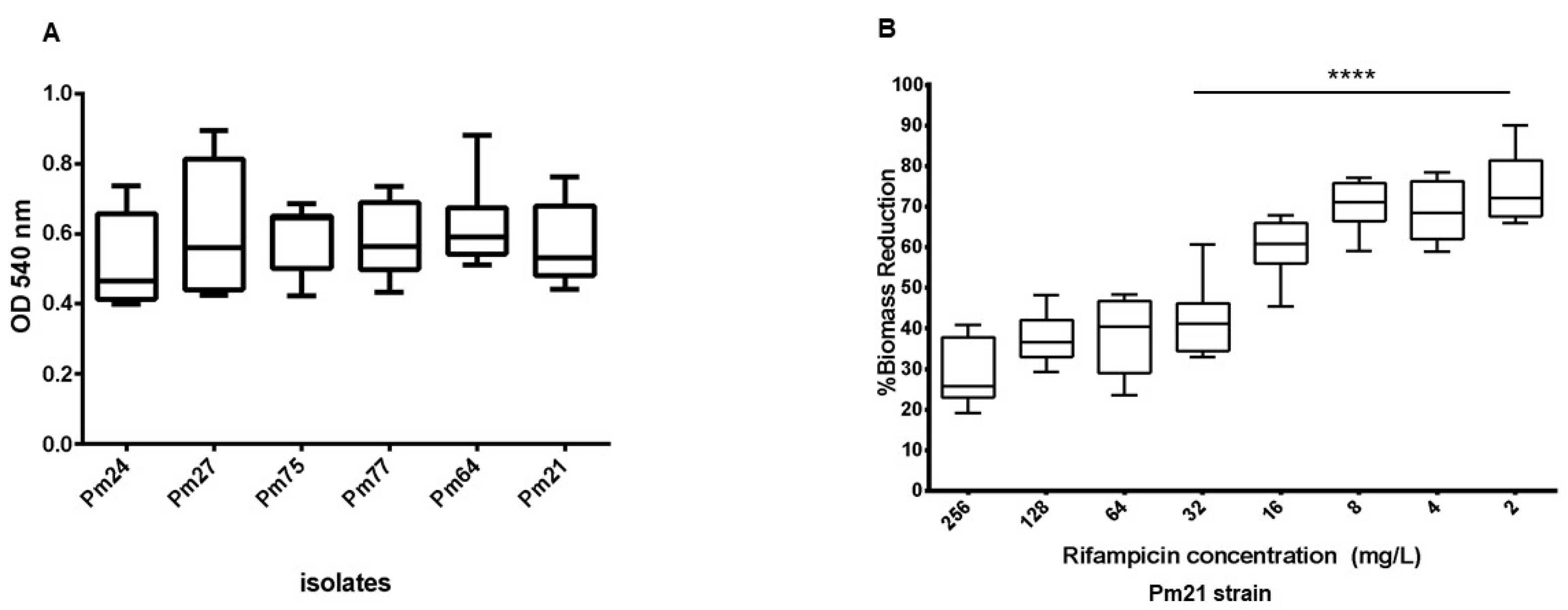

2.4. Biofilm Formation and Substrate-Specific Growth

2.5. Impact of Rifampicin on Established Biofilms

2.6. Genome Analysis

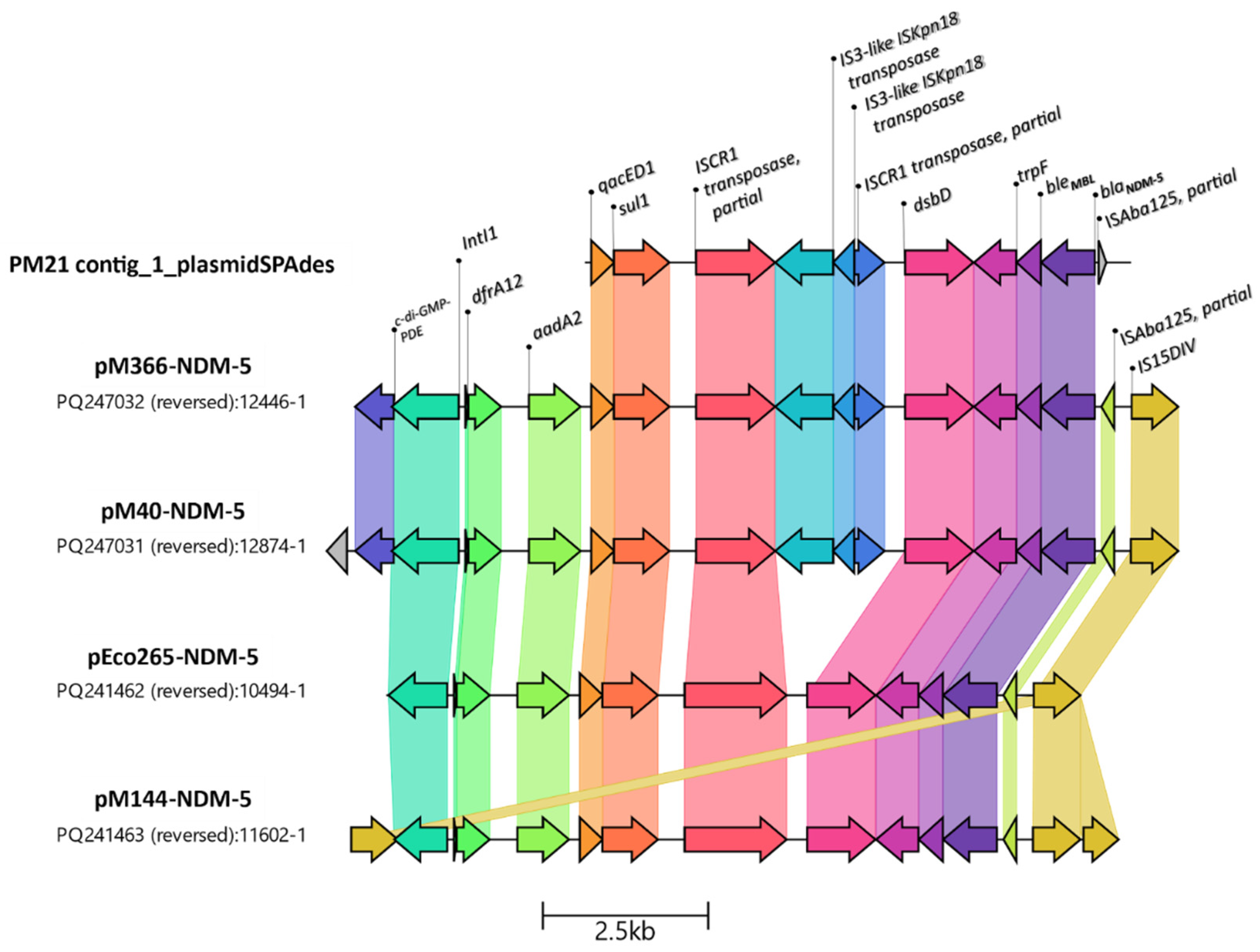

2.7. Genetic Analysis of Resistance Marker Environments

2.8. Phylogenetic Tree

3. Discussion

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Hospital Setting and Bacterial Isolates

4.2. Bacterial Identification and Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing (AST)

4.3. Resistance Mechanisms

4.4. Molecular Typing

4.5. Biofilm Formation Assays

4.6. Biofilm Antimicrobial Susceptibility

4.7. Statistical Analysis

4.8. Whole-Genome Sequencing Analysis

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| Abbreviation | Meaning |

| AMK | Amikacin |

| AST | Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing |

| AZT | Aztreonam |

| CAZ | Ceftazidime |

| CPE | Carbapenemase-Producing Enterobacteriaceae |

| CFU | Colony Forming Unit |

| CIP | Ciprofloxacin |

| CLSI | Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute |

| CTX | Cefotaxime |

| CV | Crystal Violet |

| EDTA | Ethylenediaminetetraacetic Acid |

| ERIC | Enterobacterial Repetitive Intergenic Consensus |

| ESBL | Extended Spectrum β-lactamase |

| FEP | Cefepime |

| GEN | Gentamicin |

| GI | Genomic Island |

| IPM | Imipenem |

| LB | Lysogeny Broth |

| MALDI-TOF MS | Matrix-Assisted Laser Desorption/Ionization Time-of-Flight Mass Spectrometry |

| MB | Minimum Biofilm MIC (assumed: MIC-b) |

| MBL | Metallo-β-lactamase |

| MDR | Multidrug Resistant |

| MEM | Meropenem |

| MIC | Minimum Inhibitory Concentration |

| MIC-b | Minimum Inhibitory Concentration in the Biofilm Plate |

| MLST | Multilocus Sequence Typing |

| MRC | Minimum Re-Growth Concentration |

| OD | Optical Density |

| PBA | Phenylboronic Acid |

| PBS | Phosphate-Buffered Saline |

| PTZ | Piperacillin/Tazobactam |

| REP-PCR | Repetitive Extragenic Palindromic PCR |

| ST | Sequence Type |

| TMS | Trimethoprim/Sulfamethoxazole |

| TSA | Tryptic Soy Agar |

| TSB | Tryptic Soy Broth |

| WGS | Whole-Genome Sequencing |

| cgMLST | Core Genome Multilocus Sequence Typing |

References

- Zhu, X.; Zhang, Y.; Shen, Z.; Xia, L.; Wang, J.; Zhao, L.; Wang, K.; Wang, W.; Hao, Z.; Liu, Z. Characterization of NDM-1-Producing Carbapenemase in Proteus Mirabilis among Broilers in China. Microorganisms 2021, 9, 2443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, M.; Li, D.; Jia, W.; Ma, J.; Zhao, X. Study of the Molecular Characteristics and Homology of Carbapenem-Resistant Proteus Mirabilis by Whole Genome Sequencing. Journal of Medical Microbiology 2023, 72, 001648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bitar, I.; Mattioni Marchetti, V.; Mercato, A.; Nucleo, E.; Anesi, A.; Bracco, S.; Rognoni, V.; Hrabak, J.; Migliavacca, R. Complete Genome and Plasmids Sequences of a Clinical Proteus Mirabilis Isolate Producing Plasmid Mediated NDM-1 From Italy. Microorganisms 2020, 8, 339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fusco, A.; Coretti, L.; Savio, V.; Buommino, E.; Lembo, F.; Donnarumma, G. Biofilm Formation and Immunomodulatory Activity of Proteus Mirabilis Clinically Isolated Strains. International Journal of Molecular Sciences 2017, 18, 414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wilks, S.A.; Fader, M.J.; Keevil, C.W. Novel Insights into the Proteus Mirabilis Crystalline Biofilm Using Real-Time Imaging. PLOS ONE 2015, 10, e0141711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ficik, J.; Andrezál, M.; Drahovská, H.; Böhmer, M.; Szemes, T.; Liptáková, A.; Slobodníková, L. Carbapenem-Resistant Klebsiella Pneumoniae in COVID-19 Era—Challenges and Solutions. Antibiotics 2023, 12, 1285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Yin, M.; Fang, C.; Fu, Y.; Dai, X.; Zeng, W.; Zhang, L. Genetic Analysis of Resistance and Virulence Characteristics of Clinical Multidrug-Resistant Proteus Mirabilis Isolates. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 2023, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hua, X.; Zhang, L.; Moran, R.A.; Xu, Q.; Sun, L.; Schaik, W. van; Yu, Y. Cointegration as a Mechanism for the Evolution of a KPC-Producing Multidrug Resistance Plasmid in Proteus Mirabilis. Emerging Microbes & Infections 2020.

- He, J.; Sun, L.; Zhang, L.; Leptihn, S.; Yu, Y.; Hua, X. A Novel SXT/R391 Integrative and Conjugative Element Carries Two Copies of the blaNDM-1 Gene in Proteus Mirabilis. mSphere 2021, 6, e0058821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fritzenwanker, M.; Falgenhauer, J.; Hain, T.; Imirzalioglu, C.; Chakraborty, T.; Yao, Y. The Detection of Extensively Drug-Resistant Proteus Mirabilis Strains Harboring Both VIM-4 and VIM-75 Metallo-β-Lactamases from Patients in Germany. Microorganisms 2025, 13, 266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costa, A.; Figueroa-Espinosa, R.; Gaudenzi, F.; Lincopan, N.; Fuga, B.; Ghiglione, B.; Gutkind, G.; Di Conza, J. Co-Occurrence of NDM-5 and RmtB in a Clinical Isolate of Escherichia Coli Belonging to CC354 in Latin America. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 2021, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González-Espinosa, F.; Di Pilato, V.; Calabrese, L.; Costa, E.; Costa, A.; Gutkind, G.; Cejas, D.; Radice, M. Integral Genomic Description of BlaNDM-5-Harbouring Plasmids Recovered from Enterobacterales in Argentina. Journal of Global Antimicrobial Resistance 2024, 39, 224–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bleichenbacher, S.; Stevens, M.J.A.; Zurfluh, K.; Perreten, V.; Endimiani, A.; Stephan, R.; Nüesch-Inderbinen, M. Environmental Dissemination of Carbapenemase-Producing Enterobacteriaceae in Rivers in Switzerland. Environmental Pollution 2020, 265, 115081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, L.; He, H.; Chen, Q.; Wang, K.; Lin, Y.; Li, P.; Li, J.; Liu, X.; Jia, L.; Song, H.; et al. Nosocomial Outbreak of Carbapenemase-Producing Proteus Mirabilis With Two Novel Salmonella Genomic Island 1 Variants Carrying Different blaNDM–1 Gene Copies in China. Front. Microbiol. 2022, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Protonotariou, E.; Poulou, A.; Politi, L.; Meletis, G.; Chatzopoulou, F.; Malousi, A.; Metallidis, S.; Tsakris, A.; Skoura, L. Clonal Outbreak Caused by VIM-4-Producing Proteus Mirabilis in a Greek Tertiary-Care Hospital. International Journal of Antimicrobial Agents 2020, 56, 106060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakano, R.; Nakano, A.; Abe, M.; Inoue, M.; Okamoto, R. Regional Outbreak of CTX-M-2 β-Lactamase-Producing Proteus Mirabilis in Japan. Journal of Medical Microbiology 2012, 61, 1727–1735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cremet, L.; Bemer ,Pascale; Rome ,Joanna; Juvin ,Marie-Emmanuelle; Navas ,Dominique; Bourigault ,Celine; Guillouzouic ,Aurelie; Caroff ,Nathalie; Lepelletier ,Didier; Asseray ,Nathalie; et al. Outbreak Caused by Proteus Mirabilis Isolates Producing Weakly Expressed TEM-Derived Extended-Spectrum β-Lactamase in Spinal Cord Injury Patients with Recurrent Bacteriuria. Scandinavian Journal of Infectious Diseases 2011, 43, 957–961. [CrossRef]

- Jain, S.; Gaind, R.; Kothari, C.; Sehgal, R.; Shamweel, A.; Thukral, S.S.; Chellani, H.K. VEB-1 Extended-Spectrum β-Lactamase-Producing Multidrug-Resistant Proteus Mirabilis Sepsis Outbreak in a Neonatal Intensive Care Unit in India: Clinical and Diagnostic Implications. JMM Case Rep 2016, 3, e005056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rödel, J.; Mellmann, A.; Stein, C.; Alexi, M.; Kipp, F.; Edel, B.; Dawczynski, K.; Brandt, C.; Seidel, L.; Pfister, W.; et al. Use of MALDI-TOF Mass Spectrometry to Detect Nosocomial Outbreaks of Serratia Marcescens and Citrobacter Freundii. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis 2019, 38, 581–591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Florio, L.; Riva, E.; Giona, A.; Dedej, E.; Fogolari, M.; Cella, E.; Spoto, S.; Lai, A.; Zehender, G.; Ciccozzi, M.; et al. MALDI-TOF MS Identification and Clustering Applied to Enterobacter Species in Nosocomial Setting. Front. Microbiol. 2018, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wasfi, R.; Hamed, S.M.; Amer, M.A.; Fahmy, L.I. Proteus Mirabilis Biofilm: Development and Therapeutic Strategies. Front Cell Infect Microbiol 2020, 10, 414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bouhrour, N.; Nibbering, P.H.; Bendali, F. Medical Device-Associated Biofilm Infections and Multidrug-Resistant Pathogens. Pathogens 2024, 13, 393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nwabor, L.C.; Chukamnerd, A.; Nwabor, O.F.; Pomwised, R.; Voravuthikunchai, S.P.; Chusri, S. Rifampicin Enhanced Carbapenem Activity with Improved Antibacterial Effects and Eradicates Established Acinetobacter Baumannii Biofilms. Pharmaceuticals 2023, 16, 477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Armengol, E.; Kragh, K.N.; Tolker-Nielsen, T.; Sierra, J.M.; Higazy, D.; Ciofu, O.; Viñas, M.; Høiby, N. Colistin Enhances Rifampicin’s Antimicrobial Action in Colistin-Resistant Pseudomonas Aeruginosa Biofilms. Antimicrobial Agents and Chemotherapy 2023, 67, e01641–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marchetti, V.M.; Bitar, I.; Mercato, A.; Nucleo, E.; Bonomini, A.; Pedroni, P.; Hrabak, J.; Migliavacca, R. Complete Nucleotide Sequence of Plasmids of Two Escherichia Coli Strains Carrying blaNDM–5 and blaNDM–5 and blaOXA–181 From the Same Patient. Front. Microbiol. 2020, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hornsey, M.; Phee, L.; Wareham, D.W. A Novel Variant, NDM-5, of the New Delhi Metallo-β-Lactamase in a Multidrug-Resistant Escherichia Coli ST648 Isolate Recovered from a Patient in the United Kingdom. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 2011, 55, 5952–5954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sugawara, Y.; Akeda, Y.; Hagiya, H.; Sakamoto, N.; Takeuchi, D.; Shanmugakani, R.K.; Motooka, D.; Nishi, I.; Zin, K.N.; Aye, M.M.; et al. Spreading Patterns of NDM-Producing Enterobacteriaceae in Clinical and Environmental Settings in Yangon, Myanmar. Antimicrobial Agents and Chemotherapy 2019, 63, 10.1128/aac.01924-18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.; Peng, K.; Liu, Y.; Xiao, X.; Wang, Z.; Li, R. Characterization of TMexCD3-TOprJ3, an RND-Type Efflux System Conferring Resistance to Tigecycline in Proteus Mirabilis, and Its Associated Integrative Conjugative Element. Antimicrobial Agents and Chemotherapy 2021, 65, 10.1128/aac.02712-20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.L.; Kang, Y.T.; Liang, Y.H.; Qiu, X.T.; Li, Z.J. A Core Genome Multilocus Sequence Typing Scheme for Proteus Mirabilis. Biomed Environ Sci 2023, 36, 343–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- CLSI M100 Performance Standards for Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing 30th Edition. CLSI Supplement M100 Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute; 2020.

- Cordeiro-Moura, J.R.; Fehlberg, L.C.C.; Nodari, C.S.; Matos, A.P. de; Alves, V. de O.; Cayô, R.; Gales, A.C. Performance of Distinct Phenotypic Methods for Carbapenemase Detection: The Influence of Culture Media. Diagnostic Microbiology and Infectious Disease 2020, 96, 114912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dominguez, J.E.; Redondo, L.M.; Figueroa Espinosa, R.A.; Cejas, D.; Gutkind, G.O.; Chacana, P.A.; Di Conza, J.A.; Fernández Miyakawa, M.E. Simultaneous Carriage of Mcr-1 and Other Antimicrobial Resistance Determinants in Escherichia Coli From Poultry. Front Microbiol 2018, 9, 1679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marchisio, M.L.; Liebrenz, K.I.; Méndez, E. de los A.; Di Conza, J.A. Molecular Epidemiology of Cefotaxime-Resistant but Ceftazidime-Susceptible Enterobacterales and Evaluation of the in Vitro Bactericidal Activity of Ceftazidime and Cefepime. Braz J Microbiol 2021, 52, 1853–1863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Versalovic, J.; Koeuth, T.; Lupski, R. Distribution of Repetitive DNA Sequences in Eubacteria and Application to Finerpriting of Bacterial Enomes. Nucleic Acids Research 1991, 19, 6823–6831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Passerini de Rossi, B.; García, C.; Calenda, M.; Vay, C.; Franco, M. Activity of Levofloxacin and Ciprofloxacin on Biofilms and Planktonic Cells of Stenotrophomonas Maltophilia Isolates from Patients with Device-Associated Infections. Int J Antimicrob Agents 2009, 34, 260–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stepanovic, S.; Vukovic, D.; Dakic, I.; Savic, B.; Svabic-Vlahovic, M. A Modified Microtiter-Plate Test for Quantification of Staphylococcal Biofilm Formation. J Microbiol Methods 2000, 40, 175–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Passerini de Rossi, B.; Feldman, L.; Pineda, M.S.; Vay, C.; Franco, M. Comparative in Vitro Efficacies of Ethanol-, EDTA- and Levofloxacin-Based Catheter Lock Solutions on Eradication of Stenotrophomonas Maltophilia Biofilms. J Med Microbiol 2012, 61, 1248–1253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cernohorská, L.; Votava, M. Determination of Minimal Regrowth Concentration (MRC) in Clinical Isolates of Various Biofilm-Forming Bacteria. Folia Microbiol (Praha) 2004, 49, 75–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schwengers, O.; Jelonek, L.; Dieckmann, M.A.; Beyvers, S.; Blom, J.; Goesmann, A. Bakta: Rapid and Standardized Annotation of Bacterial Genomes via Alignment-Free Sequence Identification. Microb Genom 2021, 7, 000685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bharat, A.; Petkau, A.; Avery, B.P.; Chen, J.C.; Folster, J.P.; Carson, C.A.; Kearney, A.; Nadon, C.; Mabon, P.; Thiessen, J.; et al. Correlation between Phenotypic and In Silico Detection of Antimicrobial Resistance in Salmonella Enterica in Canada Using Staramr. Microorganisms 2022, 10, 292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galata, V.; Fehlmann, T.; Backes, C.; Keller, A. PLSDB: A Resource of Complete Bacterial Plasmids. Nucleic Acids Res 2019, 47, D195–D202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molano, L.-A.G.; Hirsch, P.; Hannig, M.; Müller, R.; Keller, A. The PLSDB 2025 Update: Enhanced Annotations and Improved Functionality for Comprehensive Plasmid Research. Nucleic Acids Res 2025, 53, D189–D196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmartz, G.P.; Hartung, A.; Hirsch, P.; Kern, F.; Fehlmann, T.; Müller, R.; Keller, A. PLSDB: Advancing a Comprehensive Database of Bacterial Plasmids. Nucleic Acids Res 2022, 50, D273–D278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Siebor, E.; Neuwirth, C. Proteus Genomic Island 1 (PGI1), a New Resistance Genomic Island from Two Proteus Mirabilis French Clinical Isolates. J Antimicrob Chemother 2014, 69, 3216–3220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Seemann, T. Tseemann/Snippy 2025.

- Croucher, N.J.; Page, A.J.; Connor, T.R.; Delaney, A.J.; Keane, J.A.; Bentley, S.D.; Parkhill, J.; Harris, S.R. Rapid Phylogenetic Analysis of Large Samples of Recombinant Bacterial Whole Genome Sequences Using Gubbins. Nucleic Acids Res 2015, 43, e15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Page, A.J.; Taylor, B.; Delaney, A.J.; Soares, J.; Seemann, T.; Keane, J.A.; Harris, S.R. SNP-Sites: Rapid Efficient Extraction of SNPs from Multi-FASTA Alignments. Microbial Genomics 2016, 2, e000056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, L.-T.; Schmidt, H.A.; von Haeseler, A.; Minh, B.Q. IQ-TREE: A Fast and Effective Stochastic Algorithm for Estimating Maximum-Likelihood Phylogenies. Mol Biol Evol 2015, 32, 268–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Argimón, S.; Abudahab, K.; Goater, R.J.E.; Fedosejev, A.; Bhai, J.; Glasner, C.; Feil, E.J.; Holden, M.T.G.; Yeats, C.A.; Grundmann, H.; et al. Microreact: Visualizing and Sharing Data for Genomic Epidemiology and Phylogeography. Microbial Genomics 2016, 2, e000093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Patient | Age | Sex | Sample origin* | Date# | Sample source (n) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 61 | M | ICU | 29/9/2020 | blood culture (1) urine (1) |

| 2 | 42 | M | MCU | 1/10/2020 | catheter (2) tracheal aspirate (2) |

| 3 | 52 | M | ICU | 8/10/2020 | catheter (1) |

| 4 | 45 | M | ICU | 20/10/2020 | urine (1) |

| 5 | 51 | M | ICU | 23/10/2020 | urine (1) tracheal aspirate (1) |

| 6 | 37 | F | ICU | 27/10/2020 | catheter (1) blood culture (1) |

| 7 | 60 | M | ICU | 30/10/2020 | blood culture (2) |

| 8 | 46 | M | ICU | 7/11/2020 | catheter (1) |

| 9 | 53 | F | ICU | 8/11/2020 | blood culture (2) tracheal aspirate (2) |

| 10 | 57 | M | ICU | 11/11/2020 | blood culture (1) tracheal aspirate (1) urine (1) |

| 11 | 45 | M | MCU | 22/11/2020 | urine (1) blood culture (1) catheter (1) |

| 12 | 66 | F | GER | 25/11/2020 | blood culture (1) |

| 13 | 47 | F | MCU | 25/11/2020 | blood culture (1) |

| 14 | 50 | F | ICU | 27/11/2020 | blood culture (1) |

| 15 | 53 | F | GS | 2/12/2020 | tracheal aspirate (1) miscellaneous (1) |

| 16 | 51 | M | MCU | 5/12/2020 | blood culture (1) |

| 17 | 55 | F | MCU | 6/12/2020 | miscellaneous (1) |

| 18 | 45 | M | MCU | 20/12/2020 | blood culture (1) |

| 19 | 57 | M | GER | 7/1/2021 | blood culture (1) urine (2) |

| 20 | 65 | F | ICU | 13/1/2021 | tracheal aspirate (1) |

| 21 | 60 | M | MCU | 17/1/2021 | urine (1) |

| 22 | 43 | M | ICU | 21/1/2021 | urine (1) |

| 23 | 48 | F | ICU | 6/2/2021 | blood culture (1) catheter (1) |

| 24 | 90 | M | MCU | 9/2/2021 | miscellaneous (1) |

| 25 | 45 | M | ICU | 10/2/2021 | urine (1) |

| 26 | 50 | M | ICU | 13/2/2021 | blood culture (4) retroculture (1) catheter (1) |

| 27 | 60 | F | ICU | 5/3/2021 | blood culture (2) |

| 28 | 71 | M | MCU | 10/3/2021 | urine (1) |

| 29 | 45 | M | ICU | 12/3/2021 | catheter (2) |

| 30 | 44 | F | GS | 24/3/2021 | blood culture (3) retroculture (2) |

| 31 | 54 | M | ICU | 27/3/2021 | tracheal aspirate (1) blood culture (2) urine (2) |

| 32 | 57 | M | ICU | 14/4/2021 | tracheal aspirate (1) |

| 33 | 64 | M | ICU | 17/4/2021 | blood culture (2) tracheal aspirate (1) |

| 34 | 34 | F | ICU | 18/4/2021 | tracheal aspirate (1) |

| 35 | 56 | F | ICU | 24/4/2021 | blood culture (2) retroculture (2) |

| 36 | 54 | M | MCU | 26/4/2021 | blood culture (2) |

| 37 | 52 | M | ICU | 27/4/2021 | tracheal aspirate (1) |

| 38 | 55 | F | ICU | 27/4/2021 | tracheal aspirate (1) |

| 39 | 40 | M | ICU | 29/4/2021 | tracheal aspirate (1) |

| 40 | 51 | M | ICU | 30/4/2021 | blood culture (2) urine (2) |

| Proteus mirabilis Pm21 assembly metrics | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Characteristics | Details | |||

| Genome size (bp) | 4,265,609 | |||

| % GC content | 39.07 | |||

| N50 (bp) | 140,806 | |||

| Resistome | ||||

| Gene | Predicted Phenotype | %Identity | %Coverage | HSP Length/Total Length |

| aac(3)-IId | gentamicin | 99.88 | 100 | 861/861 |

| aac(3)-IV | gentamicin, tobramycin | 100 | 100 | 777/777 |

| aadA1 | streptomycin | 100 | 100 | 789/789 |

| aadA2 | streptomycin | 99.88 | 97,92 | 802/819 |

| aadA5 | streptomycin | 99.87 | 100 | 789/789 |

| aph(3'')-Ib | streptomycin | 100 | 100 | 804/804 |

| aph(3')-Ia | kanamycin | 100 | 100 | 816/816 |

| aph(4)-Ia | hygromycin | 100 | 100 | 1026/1026 |

| aph(6)-Id | kanamycin | 100 | 100 | 837/837 |

| blaCTX-M-15 | ampicillin, ceftriaxone | 100 | 100 | 876/876 |

| blaNDM-5 | ampicillin, amoxicillin/clavulanic acid, cefoxitin, ceftriaxone, meropenem | 100 | 100 | 813/813 |

| blaOXA-1 | ampicillin | 100 | 100 | 831/831 |

| blaOXA-2 | ampicillin | 100 | 100 | 828/828 |

| blaTEM-1B | ampicillin | 100 | 100 | 861/861 |

| cat | chloramphenicol | 98.17 | 100.15 | 655/654 |

| catA1 | chloramphenicol | 99.85 | 100 | 660/660 |

| catB3 | chloramphenicol | 100 | 69.83 | 442/633 |

| dfrA1 | trimethoprim | 100 | 100 | 474/474 |

| dfrA17-like* | trimethoprim | 100 | 86.92 | 412/474 |

| dfrA32-like* | trimethoprim | 100 | 86.92 | 412/474 |

| ere(A) | erythromycin | 99.84 | 100 | 1221/1221 |

| qacEdelta1 | resistance to antiseptics | 100 | 84.68 | 282/333 |

| rmtB | amikacin, gentamicin, kanamycin, streptomycin | 100 | 100 | 756/756 |

| sul1 | sulfisoxazole | 100 | 100 | 840/840 |

| sul2 | sulfisoxazole | 100 | 100 | 816/816 |

| tet(C) | tetracycline | 99.66 | 100 | 1191/1191 |

| tet(J) | tetracycline | 99.08 | 100 | 1197/1197 |

| Plasmids | IncQ1 | 100 | 65.83 | 524/796 |

| GenBank accession number | Sequence Read Archive submission: PRJNA1236692. | |||

| Genome assembly | https://ri.conicet.gov.ar/handle/11336/252337 | |||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).