1. Introduction

The Gram-negative bacterium Pseudomonas aeruginosa is a major cause of hospital-acquired infections. Frail hospitalized patients such as those who have suffered burns, require ventilation, or have neutropenia or chronic debility are at higher risk to develop infections due to P. aeruginosa. P. aeruginosa possesses intrinsic resistance and may acquire mechanism conferring resistance to a variety of antibiotics, including extended-spectrum-lactamases (ESBLs) and carbapenemases.

Worldwide, difficult-to-treat (DTR)

P. aeruginosa causes a wide range of severe infections, including pneumonia, bloodstream infections (BSI), endophthalmitis, endocarditis, meningitis and is frequently associated with high mortality and morbidity rates [

1,

2].

A common feature of DTR and pan-drug-resistant P. aeruginosa isolates is the production of metallo-β-lactamase (MBL) such as Verona integron–encoded (VIM) and active on imipenem (IMP) metallo-β-lactamase. A great variety of ESBLs is also reported, such as oxacillinase (OXA), Pseudomonas extended resistance β-lactamase (PER), Guiana extended spectrum β-lactamase (GES), Vietnam extender spectrum β-lactamase (VEB) and polyamine oxidase (PAO) β-lactamase.

Nowadays, β-lactamase enzymes are widely disseminated among different

P. aeruginosa sequence types (STs) and are often associated to other resistance mechanisms, including decreased membrane permeability or active efflux pump systems [

3,

4,

5]. Since the year 2000, a persistent circulation of DTR

P. aeruginosa strains producing VIM and IMP has been reported in Italian hospitals, frequently resulting in outbreaks with limited treatment options [

6,

7,

8]. As novel antimicrobial compounds such as ceftolozane-tazobactam, ceftazidime-avibactam and imipenem-relebactam are useful against non-MBL producer

P. aeruginosa, cefiderocol might be considered a last resort antibiotic for MBL producing strains [

2,

8].

Here, we report on the management of three cases of severe infections caused by DTR, MBL producer P. aeruginosa strains and investigate the molecular and epidemiological features of the isolates as well as the in vitro synergistic effects of different antibiotic combinations.

2. Patients and Methods

In January-February 2024, three cases of infection due to MBL-producing P. aeruginosa were diagnosed in three different Intensive Care Units in the San Camillo Hospital in Rome. The patients were treated with a combination of cefiderocol and imipenem/relebactam. Samples collected before the commencement of combination antibiotic therapy were sent to the Microbiology Laboratory of the National Institute for Infectious Diseases "L. Spallanzani", IRCCS Microbiology Laboratory for further phenotypic and molecular characterization of the isolates and to evaluate in vitro antibiotic synergy.

2.1. Phenotypic and Molecular Characterization of Isolates

Antibiotic susceptibility and species identification were determined by the Vitek-2 System (bioMérieux, Marcy l’Étoile, France), AST-438 plus XZ26 and MALDI-TOF MS Biotyper Sirius (Bruker Daltonics) respectively. Minimum inhibitory concentrations (MICs) for cefiderocol was performed by broth microdilution and synergy test by gradient stripes method (Liofilchem, Roseto degli Abruzzi, Italy). Results were interpreted according to the European Committee on Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing [

9]. First detection and identification of the most diffused carbapenemases (KPC, OXA-48-like, IMP, VIM and NDM) was achieved using immunochromatographic assay (NG-Test CARBA 5, Biotech, France) and confirmed by Whole Genome Sequencing (WGS) performed by Illumina Miseq (San Diego, United States). All raw reads generated were submitted to the Sequence Read Archive (SRA) under the BioProject ID PRJNA1161848.

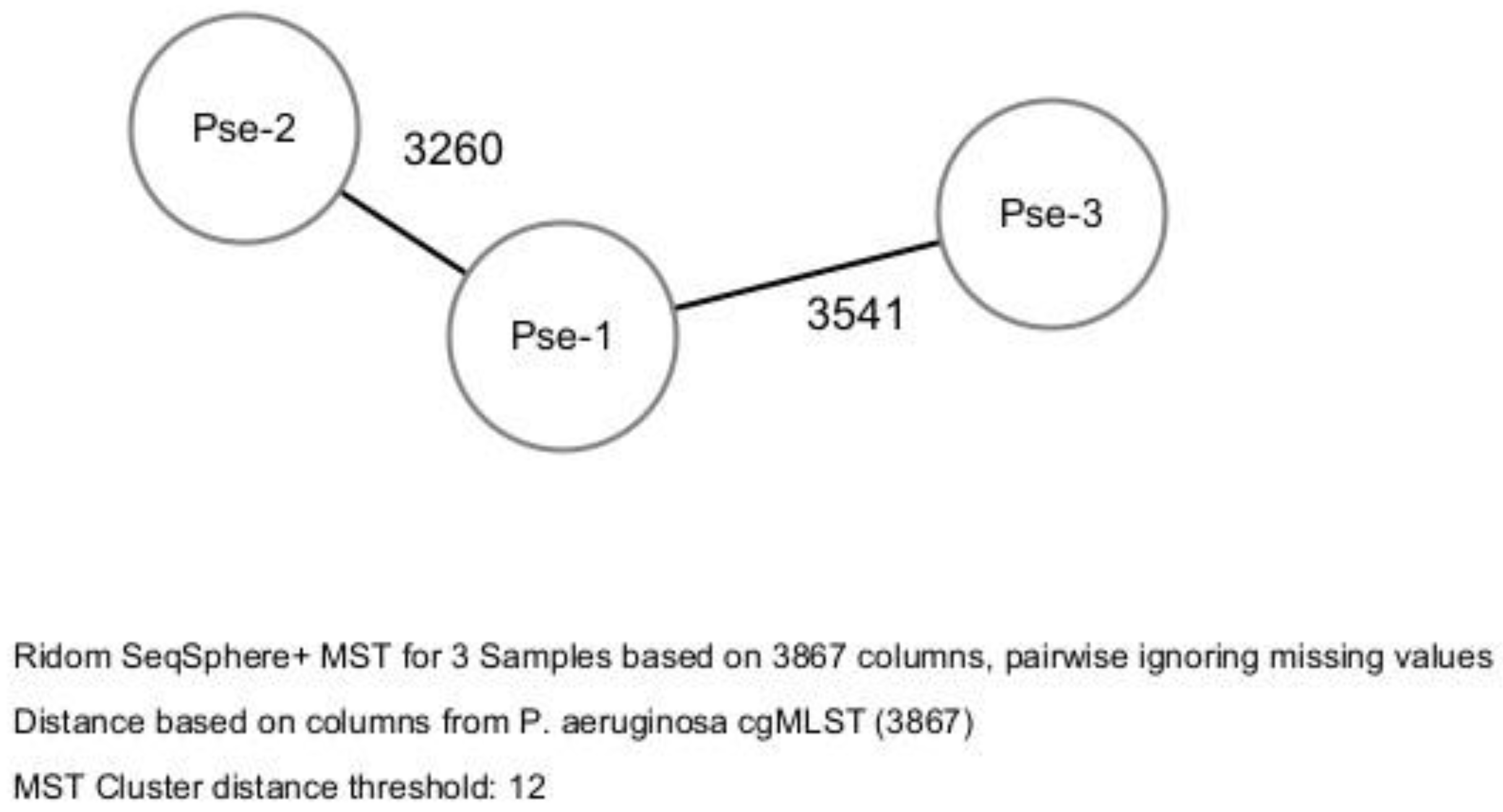

The resistance profile and Sequence types (STs) of isolates, were identified by

in silico analysis using the ResFinder v3.0 web server [

10]. Bacterial epidemiological typing was performed by the WGS-based core genome MLST (cgMLST) scheme v1.0, using the Ridom SeqSphere+ software (Ridom GmbH, Münster, Germany) with default settings. Based on the defined cgMLST for P. aeruginosa, a gene-by-gene approach with 3867 target genes, was used to compare the genomes [

11]. According to the manufacture instruction, compared to the reference strain (GenBank accession no. NC_002516.2), the resulting set of target genes was then used for interpreting the clonal relationship displayed in a minimum spanning tree (MST) using a complex type (CT) distance of 12 alleles [

12].

2.2. The Fractional Inhibitory Concentration (FIC) Index as a Measure of Antibiotic Synergy

An inoculum equal to 0.5 McFarland turbidity was prepared from each isolate. Determination of MICs by E-test was first performed for the two drugs separately, and the MICs were interpreted at the point of intersection between the inhibition zone and the E-test strip. For synergy testing, the two E-test strips were placed on the same culture plate in a cross formation, so that they intersected each other at their respective MICs with a 90° angle or at the highest concentration present on the E-test strip, when the MIC exceeded this value (e.g., > 256 mg/L). The plates were then incubated at 37°C for 24 hours. The Fractional Inhibitory Concentration Index (FICI) was calculated on the basis of the resulting zone of inhibition as follows: FICI = FIC A+FIC B, where FIC A is the MIC of the combination/MIC of drug A alone, FIC B is the MIC of the combination/MIC of drug B alone [

13]. interpretation of the FIC results, according to accepted criteria, were as follows: <= 0.5, synergy; 0.5 to 1.0, additivity; >1.0 to 4.0, indifference; and >4, antagonism [

13].

3. Results

3.1. Clinical Cases Presentation

Three patients were included in the study, receiving combination therapy with cefiderocol and imipenem/relebactam. All three patients had prompt clinical improvement and microbial eradication, without the occurrence of relapses. This resulted in their discharge from the Intensive Care Units where they had been admitted.

Case 1 - isolate Pse-1

The initial case was that of a 65-year-old patient who had undergone cardiac surgery to replace the ascending aorta due to a diagnosis of type A dissection. This patient was diagnosed with mechanical ventilator-associated pneumonia. The patient was receiving intensive care and was undergoing continuous renal replacement therapy. The microorganism isolated from bronchoalveolar lavage was a P. aeruginosa producing IMP-13 MBL (Pse-1). The patient was treated with combination therapy with cefiderocol, 2 grams every 8 hours as a continuous infusion, in association with imipenem/relebactam, 0,625 grams every 6 hours for a total duration of 7 days. This resulted in a rapid resolution of the clinical picture, allowing a rapid respiratory weaning with early extubation four days after the start of combination antimicrobial therapy.

Case 2 - isolate Pse-2

The second case concerned a central venous catheter-related bloodstream infection in a 37-year-old patient who had been hospitalized in the intensive care unit due to a recent road polytrauma. A strain of P. aeruginosa producing VIM was isolated from blood cultures (Pse-2). The patient underwent replacement of the central venous catheter and a combination antibiotic treatment was initiated, comprising cefiderocol (2 grams every 8 hours in extended infusion) and imipenem/relebactam (1,250 grams every 6 hours for a total duration of 14 days). During this period, the patient made a rapid recovery, with negative control blood cultures and echocardiogram.

Case 3 - isolate Pse-3

The third case was a 43-year-old woman with bacteremic pneumonia associated with mechanical ventilation. The patient was initially admitted to the intensive care unit for the treatment of pneumonia and severe acute respiratory failure caused by the influenza A H1N1 virus. A strain of P. aeruginosa producing IMP-13 was isolated from the blood (Pse-3). The patient was treated with a combination of cefiderocol (2 grams every 8 hours in prolonged infusion) and imipenem/relebactam (1,250 grams every 6 hours for a total duration of 14 days). The patient made a rapid recovery during treatment with early negativity of control blood cultures, rapid and progressive improvement of respiratory exchanges, allowing extubation three days after starting the combination therapy.

3.2. Phenotypic and Molecular Characterization of Isolates

As shown in

Table 1, the three isolates (named Pse-1 Pse-2 and Pse-3) were obtained from different specimens: bronchoalveolar lavage for Pse-1, blood culture for Pse-2 and Pse-3. Pse-1 and Pse-2 were resistant to carbapenems, ceftazidime-avibactam, ceftolozane-tazobactam, meropenem-vaborbactam, imipenem-relebactam and ciprofloxacin. Isolate Pse-3 was resistant to ceftazidime-avibactam and ceftolozane-tazobactam. All the three isolates were susceptible to cefiderocol.

Detection of acquired antimicrobial resistance genes and STs are recorded in

Table 2.

The three isolates were positive for beta-lactams resistance genes such as MBLs (VIM-2 or IMP-13), blaPAO and OXA-type beta-lactamases but belonged to different STs.

Pse-1 (ST621) harbored blaIMP-13. Instead, Pse-2 produced a VIM-2 carbapenemase and belonged to the ST233, a clonal strain, referred as an international high-risk clone, responsible for nosocomial infection identified worldwide [

14]. Additional resistance profile of Pse-2 isolates, showed the presence of 3 aminoglycoside resistance genes [aac(6’)-II, aph(3’)-IIb, aac(3’)-Id], 3 phenicol resistance genes [catB7 cmlA1 floR], a quaternary ammonium compound qacE, and tetracycline, fosfomycin, sulfonamide, trimethoprim and quinolone resistance genes tet(G), fosA, sul1, dfrB5 and crpP, respectively.

According to the cgMLST method, the three isolates did not cluster into a Cluster-Type, and were categorized as belonging to 3 STs showing high allelic distance (more than 3000 allele difference) (

Figure 1).

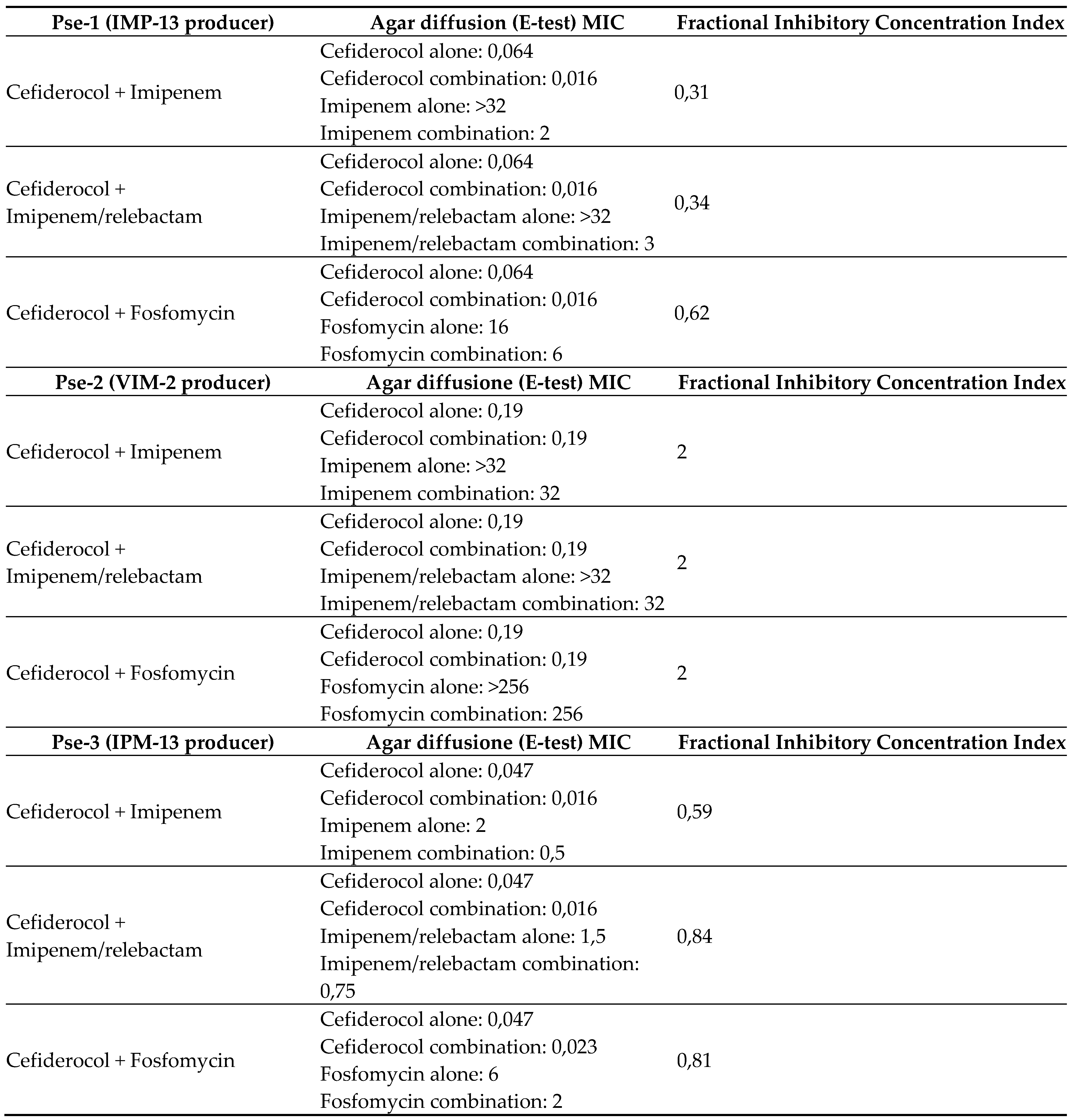

3.3. The Evaluation of Antibiotic Synergy by Fractional Inhibitory Concentration Index (FICI)

The evaluation of antibiotic synergy by the E-test method and the FICI showed the presence of synergy/additivity of cefiderocol in combination with imipenem-relebactam in the two

P. aeruginosa isolates producing IMP-13. Pse-1 had a FICI of 0.34 (synergy), Pse-3 had a FICI of 0.84 (additivity). No synergy between cefiderocol and imipenem-relebactam was observed for the Pse-2 isolate producing VIM-2 (FICI of 2, defined as indifference) (

Figure 2).

Bacterial epidemiological typing was performed by the whole genome sequencing-based core genome multi-locus sequence typing (cgMLST). A gene-by-gene approach with 3867 target genes was used to compare the genomes.

An inoculum equal to a 0.5 McFarland turbidity was prepared from each isolate. Determination of MICs by E-test was first performed for the two drugs separately, and the MICs were interpreted at the point of intersection between the inhibition zone and the E-test strip. For synergy testing, the two E-test strips were placed on the same culture plate in a cross formation, so that they intersected each other at their respective MICs with a 90° angle or at the highest concentration present on the E-test strip, when the MIC exceeded this value (e.g., > 256 mg/L). The plates were then incubated at 37°C for 24 hr. The Fractional Inhibitory Concentration Index (FICI) was calculated on the basis of the resulting zone of inhibition as follows: FICI = FI A+FIC B, where FIC A is the MIC of the combination/MIC of drug A alone, FIC B is the MIC of the combination/MIC of drug B alone. interpretation of the FIC results, according to accepted criteria, were as follows: <= 0.5, synergy; 0.5 to 1.0, additivity; >1.0 to 4.0, indifference; and >4, antagonism.

4. Discussion

The global occurrence of carbapenem-resistant and MDR P. aeruginosa is alarming because infections by these bacteria often result in limited treatment options [

15]. The antimicrobial cefiderocol might be considered a last resort drug for some MBLs, non-New Delhi metallo-β-lactamase producing P. aeruginosa strain. Alarmingly, the emergence of cefiderocol resistance has been reported in non-New Delhi metallo-β-lactamase producing P. aeruginosa strains [

16,

17]. The emergence of resistance to cefiderocol in P. aeruginosa has been demonstrated both in vitro and in vivo, and was linked to alterations of the iron uptake pathways [

18,

19,

20,

21]

Here, we present three cases of severe MDR P. aeruginosa infection sustained by MBL producing strains, successfully treated with an antibiotic combination of cefiderocol and imipenem/relebactam. It is important to remark that currently there is no clear evidence that association therapy is more effective than monotherapy for infection due to MDR P. aeruginosa [

22], unless may be in severe infections like septic shock.

A recent multicentre, retrospective cohort study [

23] compared outcomes of patients with septic shock due to P. aeruginosa BSI receiving adequate empirical combination therapy to those on adequate empirical monotherapy. Adequate empirical combination therapy was associated with a lower 30-day all-cause mortality (25%, six out of 24) compared to adequate empirical monotherapy (56.8%, 42 out of 74; P = 0.007). Multivariate Cox regression analysis indicated Adequate empirical combination therapy as the only factor significantly associated with improved survival (aHR 0.30; 95% CI 0.12–0.71; P: 0.006) [

23].

The administration of cefiderocol in combination with other antibiotics, i.e. ceftazidime/avibactam, ampicillin/sulbactam or meropenem, has been recently proposed to treat MDR and pandrug-resistant Gram negative bacteria, including P. aeruginosa [

24,

25]. The rationale for administering cefiderocol in combination with other antimicrobials is to avoid resistance development and to exploit a potential synergistic effect [

24].

The antibiotic combination may provide a synergistic effect, determining a greater and faster bactericidal effect, with improved patient outcome [

26]. In addition, a potential benefit of the combination therapy is the reduction in the emergence of resistance to cefiderocol [

27,

28]. To consider, combination therapy may also have disadvantages, such as potentially increasing toxicity, or increased C. difficile infections [

29]. Moreover, there is currently little data available to guide the choice of ancillary drug to be given with cefiderocol in the treatment of MBL-producing P. aeruginosa infections, i.e. fosfomycin or carbapenems.

In literature, there is scant data on the evaluation of synergy between cefiderocol and other antimicrobials against P. aeruginosa [

30,

31].

Therefore, an assay to evaluate the synergy between cefiderocol and imipenem, imipenem/relebactam, fosfomycin as well as other antibiotics, may have potential therapeutic utility in the management of MBL-producing P. aeruginosa infections to assist in the selection or discontinuation of the companion drug in combination with cefiderocol. Of course, this approach may only be useful if supported by prior microbiological testing of the isolate susceptibility profile and molecular characterisation. To our knowledge, this is the first report using the E-test technique and FICI to evaluate the synergy of cefiderocol plus imipenem/relebactam against MBL-producing P. aeruginosa strains.

By E-test and FICI evaluation, our two P. aeruginosa producing IMP-13 MBL showed synergy or additivity of cefidercol plus imipenem/relebactam, whilst the isolate producing VIM-2 showed no synergy effect. The mechanisms behind the synergy between cefiderocol and imipenem against P. aeruginosa are still unclear. One possible explanation could be the inhibition of multiple PBP targets by the two drugs (i.e., PBP 3, which is preferentially bound by cefiderocol, and other PBPs including PBP2, which are bound by imipenem at concentrations that might partially evade degradation by MBLs [

31,

32,

33].

Further studies on the potential synergistic effects of cefiderocol combinations with carbapenems and other antimicrobials would be useful.

Understanding of the specific MBL type may also be of potential benefit. In our study, the difference in the phenotypic profiles of the three P. aeruginosa isolates could be a result of the difference in the resistome. All isolates were positive for β-lactam resistance genes such as MBLs (VIM or IMP), blaPAO and an OXA-type beta-lactamase and belonged to three different STs. Pse-1 and Pse-3, respectively ST621 and ST446, harboured blaIMP-13 and an identical additional resistance profile. Interestingly, they showed a completely different phenotypic profile. This could be due to a difference in membrane permeability and efflux pumps, as both OXA-50 and OXA-395 are oxacillinases with weak carbapenemase activity (unique difference in the molecular profile of isolates Pse-1 and Pse-3) [

34,

35].

5. Conclusions

Until further data are available, clinicians may consider combination therapy with cefiderocol and another antimicrobial for the treatment of severe infections caused by MBL-producing P. aeruginosa in order to avoid the development of cefiderocol resistance and to take advantage of a potential synergistic effect.

The E-test and FICI evaluation may prove a valuable tool in the treatment of MBL-producing P. aeruginosa infections, assisting in the selection or discontinuation of the companion drug in combination with cefiderocol.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, G.G., C.V., C.F. and S.C.; methodology, C.R., V.D., S.D., A.G.; software, G.G., C.V.; validation, G.G, C.F., A.C. and S.C.; formal analysis, G.P., A.C., C.V., C.F.; investigation, G.P., A.C., C.V., C.F.; resources, G.P., S.C., C.F.; data curation, C.R., V.D., S.D., A.G.; writing—original draft preparation, G.G., C.V.; writing—review and editing, G.G., A.C., S.C.; visualization, G.G., C.V., C.F., S.C.; supervision, S.C., C.F.; project administration, S.C., C.F.; funding acquisition, S.C., C.F. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.”.

Funding

This work was supported by the Italian Ministry of health, through Ricerca Corrente Line n. 1, Project n. 2.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Acknowledgments

We gratefully acknowledge the staff of our BioBank: Gianluca Prota, Alberto Rossi, Melissa Baroni, Valentina Antonelli for their helpful activity in the storage of samples and microorganisms.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Reynolds, D.; Kollef, M. The Epidemiology and Pathogenesis and Treatment of Pseudomonas aeruginosa Infections: An Update. Drugs 2021, 81, 2117–2131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bassetti, M.; Echols, R. , Matsunaga, Y.; Ariyasu, M.; Doi, Y.; Ferrer, R.; Lodise, T. P.; Naas, T.; Niki, Y.; Paterson, D.L.; Portsmouth, S.; Torre-Cisneros, J.; Toyoizumi, K.; Wunderink, R.G.; Nagata, T.D.. Efficacy and safety of cefiderocol or best available therapy for the treatment of serious infections caused by carbapenem-resistant Gram-negative bacteria (CREDIBLE-CR): a randomised, open-label, multicentre, pathogen-focused, descriptive, phase 3 trial. Lancet Infect Dis 2021, 21, 226–240. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Ahmed, O.B. Detection of Antibiotic Resistance Genes in Pseudomonas aeruginosa by Whole Genome Sequencing. Infect Drug Resist 2022, 15, 6703–6709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Breidenstein, E.B.; de la Fuente-Nu´ ñez, C.; Hancock, R.E. Pseudomonas aeruginosa: all roads lead to resistance. Trends microbiol 2011, 19, 419–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Streling, A.P.; Cayô, R.; Nodari, C.S.; Almeida, L.G.P.; Bronze, F.; Siqueira, A.V.; Matos, A.P.; Oliveira, V.; Vasconcelos, A.T.R.; Marcondes, M.F.M.; Gales, A.C. Kinetics Analysis of β-Lactams Hydrolysis by OXA-50 Variants of Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Microb Drug Resist 2022, 28, 849–852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pagani, L.; Colinon, C.; Migliavacca, R.; Labonia, M.; Docquier, J.D.; Nucleo, E.; Spalla, M.; Li Bergoli, M.; Rossolini, G.M. Nosocomial outbreak caused by multidrug-resistant Pseudomonas aeruginosa producing IMP-13 metallo-beta-lactamase. J Clin Microbiol 2005, 43, 3824–3828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rossolini, G.M.; Riccio, M.L.; Cornaglia, G.; Pagani, L.; Lagatolla, C.; Selan, L.; Fontana, R. Carbapenem-resistant Pseudomonas aeruginosa with acquired bla(vim) metallo-beta-lactamase determinants, Italy. Emerg Infect Dis 2000, 6, 312–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Do Rego, H.; Timsit, J.F. Management strategies for severe Pseudomonas aeruginosa infections. Curr Opin Infect Dis 2023, 36, 585–595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Available at: http://www.eucast.org. Last accessed. 02/09/2024.

- Available at: http://www.genomicepidemiology.org. Last accessed. 02/09/2024.

- Tönnies, H.; Prior, K.; Harmsen, D.; Mellmann, A. Establishment and evaluation of a core genome multilocus sequence typing scheme for whole-genome sequence-based typing of Pseudomonas aeruginosa. J Clin Microbiol 2020, 59, e01987–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Available at: www.cgMLST.org. Last accessed. 02/09/2024.

- Okoliegbe, I.N.; Hijazi, K.; Cooper, K.; Ironside, C. : Gould, I.M. Antimicrobial Synergy Testing: Comparing the Tobramycin and Ceftazidime Gradient Diffusion Methodology Used in Assessing Synergy in Cystic Fibrosis-Derived Multidrug-Resistant Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Antibiotics (Basel) 2021, 10, 967. [Google Scholar]

- Dößelmann, B.; Willmann, M.; Steglich, M.; Bunk, B.; Nübel, U.; Peter, S.; Neher, R.A. Rapid and Consistent Evolution of Colistin Resistance in Extensively Drug-Resistant Pseudomonas aeruginosa during Morbidostat Culture. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 2017, 61, e00043–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sastre-Femenia, M.À.; Fernández-Muñoz, A.; Gomis-Font, M.A.; Taltavull, B.; López-Causapé, C.; Arca-Suárez, J.; Martínez-Martínez, L.; Cantón, R.; Larrosa, N.; Oteo-Iglesias, J.; Zamorano, L.; Oliver, A.; GEMARA-SEIMC/CIBERINFEC Pseudomonas study Group. Pseudomonas aeruginosa antibiotic susceptibility profiles, genomic epidemiology and resistance mechanisms: a nation-wide five-year time lapse analysis. Lancet Reg Health Eur 2023, 34, 100736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Poirel, L.; Ortiz de la Rosa, J.M.; Sadek, M.; Nordmann, P. Impact of acquired broad-spectrum β-lactamases on susceptibility to cefiderocol and newly developed β-lactam/β-lactamase inhibitor combinations in Escherichia coli and Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 2022, 66, e0003922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fröhlich, C.; Sørum, V.; Tokuriki, N.; Johnsen, P.J.; Samuelsen, Ø. Evolution of β-lactamase-mediated cefiderocol resistance. J Antimicrob Chemother 2022, 77, 2429–2436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Streling, A.P.; Al Obaidi, M.M.; Lainhart, W.D.; Zangeneh, T.; Khan, A.; Dinh, A.Q.; Hanson, B.; Arias, C.A.; Miller, W.R. Evolution of Cefiderocol Non-Susceptibility in Pseudomonas aeruginosa in a Patient Without Previous Exposure to the Antibiotic. Clinical Infectious Diseases 2021, e4472–e4474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Teran, N.; Egge, S.L.; Phe, K.; Baptista, R.P.; Tam, V.H.; Miller, W.R. The emergence of cefiderocol resistance in Pseudomonas aeruginosa from a heteroresistant isolate during prolonged therapy. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 2024, 68, e0100923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shields, R.K.; Kline, E.G.; Squires, K.M.; Van Tyne, D.; Doi, Y. In vitro activity of cefiderocol against Pseudomonas aeruginosa demonstrating evolved resistance to novel β-lactam/β-lactamase inhibitors. JAC-Antimicrobial Resistance 2023, 5, dlad107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sadek, M.; Le Guern, R.; Kipnis, E.; Gosset, P.; Poirel, L.; Dessein, R.; Nordmann, P. Progressive in vivo development of resistance to cefiderocol in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis 2023, 42, 61–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Foucrier, A.; Dessalle, T.; Tuffet, S.; Federici, L.; Dahyot-Fizelier, C.; Barbier, F.; Pottecher, J.; Monsel, A.; Hissem, T.; Lefrant, J.Y.; Demoule, A.; Constantin, J.M.; Rousseau, A.; Simon, T.; Leone, M.; Bouglé, A.; iDIAPASON Trial Investigators. Association between combination antibiotic therapy as opposed as monotherapy and outcomes of ICU patients with Pseudomonas aeruginosa ventilator-associated pneumonia: an ancillary study of the iDIAPASON trial. Crit Care 2023, 27, 211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vena, A.; Schenone, M.; Corcione, S.; et al. On behalf of SITA GIOVANI (Young Investigators Group of the Società Italiana Terapia Antinfettiva). Impact of adequate empirical combination therapy on mortality in septic shock due to Pseudomonas aeruginosa bloodstream infections: a multicentre retrospective cohort study. J Antimicrob Chemother 2024, dkae296. [Google Scholar]

- Bavaro, D.F.; Belati, A.; Diella, L.; Stufano, M.; Romanelli, F.; Scalone, L.; Stolfa, S.; Ronga, L.; Maurmo, L.; Dell’Aera, M.; et al. Cefiderocol-Based Combination Therapy for “Difficult-to-Treat” Gram-Negative Severe Infections: Real-Life Case Series and Future Perspectives. Antibiotics 2021, 10, 652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gill, C.M.; Santini, D.; Takemura, M.; Longshaw, C.; Yamano, Y.; Echols, R.; Nicolau, D.P. In vivo efficacy & resistance prevention of cefiderocol in combination with ceftazidime/avibactam, ampicillin/sulbactam or meropenem using human-simulated regimens versus Acinetobacter baumannii. Journal of Antimicrobial Chemotherapy 2023, 78, 983–990. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Schmid, A.; Wolfensberger, A.; Nemeth, J.; Schreiber, P.W.; Sax, H.; Kuster, S.P. Monotherapy versus combination therapy for multidrug-resistant Gram-negative infections: Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Sci Rep 2019, 9, 15290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fischbach, M.A. Combination therapies for combating antimicrobial resistance. Curr Opin Microbiol 2011, 14, 519–523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guillamet, M.C.V.; Vazquez, R.; Noe, J.; Micek, S.T.; Fraser, V.J.; Kollef, M.H. Impact of Baseline Characteristics on Future Episodes of Bloodstream Infections: Multistate Model in Septic Patients with Bloodstream Infections. Clin Infect Dis 2020, 71, 3103–3109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scully, M.; Hassoun, A. Increasing evidence of potential toxicity of a common antibiotic combination. J Infect Public Health 2018, 11, 594–595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palombo, M.; Bovo, F.; Amadesi, S.; Gaibani, P. Synergistic Activity of Cefiderocol in Combination with Piperacillin-Tazobactam, Fosfomycin, Ampicillin-Sulbactam, Imipenem-Relebactam and Ceftazidime-Avibactam against Carbapenem-Resistant Gram-Negative Bacteria. Antibiotics 2023, 12, 858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tascini, C.; Antonelli, A.; Pini, M.; De Vivo, S.; Aiezza, N.; Bernardo, M.; Di Luca, M.; Rossolini, G.M. Infective Endocarditis Associated with Implantable Cardiac Device by Metallo-β-Lactamase-Producing Pseudomonas aeruginosa, Successfully Treated with Source Control and Cefiderocol Plus Imipenem. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 2023, 67, e0131322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ito, A.; Sato, T.; Ota, M.; Takemura, M.; Nishikawa, T.; Toba, S.; Kohira, N.; Miyagawa, S.; Ishibashi, N.; Matsumoto, S.; Nakamura, R.; Tsuji, M.; Yamano, Y. In vitro antibacterial properties of cefiderocol, a novel siderophore cephalosporin, against Gram-negative bacteria. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 2018, 62, e01454–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hashizume, T.; Ishino, F.; Nakagawa, J-I. et al. Studies on the mechanism of action of imipenem (N-formimidoylthienamycin) in vitro: binding to the penicillin-binding proteins (PBPs) in Escherichia coli and Pseudomonas aeruginosa, and inhibition of enzyme activities due to the PBPs in E. coli. J Antibiot 1984, 37, 394–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nakae, T. Role of membrane permeability in determining antibiotic resistance in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Microbiol Immunol 1995, 39, 221–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Streling, A.P.; Cayô, R.; Nodari, C.S.; Almeida, L.G.P.; Bronze, F.; Siqueira, A.V.; Matos, A.P.; Oliveira, V.; Vasconcelos, A.T.R.; Marcondes, M.F.M.; Gales, A.C. Kinetics Analysis of β-Lactams Hydrolysis by OXA-50 Variants of Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Microb Drug Resist 2022, 28, 849–852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).