1. Introduction

Cefiderocol (CFD) is a novel cephalosporin that combines structural motifs similar to those found in ceftazidime and cefepime, namely dimethyl, oxime, and pyrrolidinium groups, which confer stability against a wide range of beta-lactamases, including carbapenemases. It features a chlorocatechol moiety in the C-3 side chain, enabling it to chelate trivalent iron ions, mimicking siderophores and leveraging bacterial iron uptake mechanisms to actively penetrate the periplasmic space, where it exerts its antibacterial activity predominantly through the inhibition of penicillin-binding protein (PBP) 3 [

1]. Consequently, it has emerged as a promising therapeutic alternative for infections caused by difficult-to-treat Gram-negative bacteria [

2]. However, since its clinical approval in 2019, resistant isolates and the emergence of resistance during treatment have been reported [

3,

4], underscoring the need to characterize the underlying mechanisms to optimize its use and prevent the spread of resistant strains, thus prolonging the antibiotic’s clinical utility.

The main resistance mechanisms identified to date involve alterations in siderophore receptors, specific beta-lactamase variants, mutations in PBP3, and changes in membrane permeability [

5]. Evidence supporting these findings derived from isogenic mutant construction assays, but genomic analyses of clinical isolates is still limited. Although observational studies suggest that resistance to CFD remains low, the growing number of resistance reports is concerning [

6,

7]. This study aims to compare the resistome of two collections of CPE from human origin, CFD resistant and CFD susceptible, in order to explore the possible genomic determinants of CFD resistance.

2. Results

2.1. Isolate Selection and Identification

From January 1, 2022, to December 31, 2024, a total of 172 non-duplicate (first isolate per patient) CPE isolates were identified from clinical and epidemiological samples at the Microbiology laboratory of the Miguel Servet University Hospital (HUMS) in Zaragoza, Spain. The most prevalent species were Klebsiella pneumoniae complex, Escherichia coli, Citrobacter spp., and Enterobacter cloacae complex, accounting for 51%, 19%, 13%, and 10% of cases, respectively. Of these, 63 strains (~36%) were tested for CFD susceptibility by one of the accepted methods listed in the inclusion criteria. Resulting in 31 susceptible (CFD-S), 30 resistant (CFD-R) and two within the area of technical uncertainty that were excluded from further analysis.

After phenotypic evaluation identification was confirmed prior to sequencing to ensure culture purity, using Matrix assisted laser desorption ionization time of flight mass spectrometry (MALDI-TOF MS). Following whole-genome sequencing (WGS), two strains—one from each group—were excluded due to a N-50 sub-threshold value and contamination, respectively. The contaminated sample contained sequences belonging to Citrobacter portucalensis (80%) and Citrobacter cronae (20%), both belonging to the Citrobacter freundii complex. Given the sequencing depth was near the lower acceptable limit, no filtering was applied, and the isolate was entirely excluded from the study. All remaining strains met quality control thresholds.

Consequently, the final cohort included 29 CFD-R and 30 CFD-S isolates. Species distribution based on WGS was as follows: Resistant group: K. pneumoniae (n=15), E. coli (n=9), Enterobacter hormaechei (n=2), Enterobacter asburiae (n=1), Enterobacter kobei (n=1), C. portucalensis (n=1), Providencia stuartii (n=1); Susceptible group: K. pneumoniae (n=16), Klebsiella variicola (n=1), E. coli (n=5), E. hormaechei (n=2), C. portucalensis (n=1), Citrobacter koseri (n=1), P. stuartii (n=1), Providencia hangzhouensis (n=1), Morganella morganii (n=1), Serratia sarumanii (n=1).

2.2. Origin of Isolates and Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing

Approximately, 80% of the samples were obtained from male patients. The median age at the time of sample collection was 46 years, ranging from 7 to 88 years. No significant age differences were observed between the resistant and susceptible groups.

A total of 59% of the isolates were recovered from epidemiological samples, primarily from rectal or triple-site swabs collected as part of the hospital’s “Zero Resistance” programme [

8]. The distribution of epidemiological samples was comparable between the CFD-R and CFD-S groups (p>0.05). The remaining samples were of clinical origin, with urine and wound exudate being the most prevalent sample types, accounting for 16.9% and 13.5%, respectively, with no significant differences in sample type distribution between the groups. The fact that an isolate was obtained from an epidemiological sample does not preclude the possibility that the patient developed a clinical infection later during hospitalization or after discharge. Three isolates originated from invasive samples (ascitic fluid, prosthetic joint material, and blood).

The overall rate of antibiotic resistance was high in both groups. All isolates showed non-susceptibility to ceftazidime and cefepime. Resistance to carbapenems (ertapenem, imipenem, and meropenem)was 89.8%, 89.8%, and 81.4%, respectively. Approximately three-quarters of the isolates were resistant to second- and third-generation fluoroquinolones, ciprofloxacin and levofloxacin. Aminoglycoside resistance ranged from 54.2% for amikacin to 91.5% for tobramycin. Resistance rates for last-resort antibiotics fosfomycin, tigecycline, and colistin was 37.3%, 35.6%, and 18.6%, respectively. Furthermore, resistance rates were 100% and 78% for the new-generation antibiotics ceftolozane–tazobactam and ceftazidime–avibactam. These resistance patterns were interpreted in light of the intrinsic resistance profiles of Enterobacteriaceae species evaluated, including chromosomal AmpC expression in certain species. Fosfomycin results were restricted to E. coli, and tigecycline results were interpreted based on E. coli-specific breakpoints.

2.3. Sequence Types, Resistome, and Plasmid Characterization

A high diversity of sequence types (ST) was observed among the global set of isolates. Among CFD-R K. pneumoniae isolates, ST395 was the most prevalent, while ST23 and ST512 were exclusive to this group. Conversely, ST147 was the most common ST in the CFD-S group, though these differences were not statistically significant. No predominant STs or statistically significant differences were observed in the other bacterial species.

Both groups exhibited complex resistomes, including Ambler classes A, B, and D carbapenemases [

9]. Among the CFD-R group, 38 carbapenemase genes were detected, including isolates with co-existing metallo and serine-carbapenemases. NDM-type enzymes were the most frequent, specifically

blaNDM-1 (n=13), followed by

blaKPC-3 (n=6) and

blaNDM-5 (n=5). Notably,

blaNDM-1 + blaOXA-48-like co-occurrence was identified in seven isolates. In the CFD-S group, VIM-type carbapenemases were significantly more common (p<0.05), particularly

blaVIM-1 (n=12), followed by

blaNDM-1 (n=10). Only one isolate carried

blaKPC-3, and the only combination observed was

blaNDM-1 + blaOXA-48,found in five isolates.

Extended-spectrum beta-lactamases (ESBL) were detected in half of the collection, primarily blaCTX-M-15, with no significant differences observed between groups. However, blaCTX-M-55 and blaCTX-M-9 were exclusively found in the CFD-R and CFD-S groups, respectively. Plasmid-mediated AmpC-type beta-lactamases (blaCMY alleles) were exclusively detected in the CFD-R group (p<0.05).

Mutations in gyrA and parC were more common in the CFD-R group, particularly D87N and S83I in GyrA for E. coli and K. pneumoniae, respectively. Numerous acetyltransferases, nucleotidyltransferases, and phosphotransferases were found in both groups. Notably, the mcr-10.1 and mcr-1.1 alleles were detected in one E. asburiae isolate (resistant group) and one E. coli isolate (susceptible group), respectively.

At least one carbapenemase-encoding plasmid was successfully reconstructed in 86% of the CFD-R isolates. The average plasmid size was 140Kb (range: 4.3–353Kb), belonging to various incompatibility groups, mainly IncF and IncC. Conjugative plasmids accounted for 72%, with MOBH and MOBF being the most frequent relaxases. Five isolates harboured at least two plasmids encoding carbapenemases. In the CFD-S group, 90% of the carbapenemase-harbouring plasmids were reconstructed, with at least two plasmids detected in five isolates. The average plasmid size was approximately 130Kb, with IncL and IncF being the most common incompatibility groups. Conjugative plasmids represented 74% of the total, and MOBP was the most frequent relaxase.

Table 1 summarises the main microbiological and epidemiological features of the included isolates, showing the distribution for species, sample origin, carbapenemase type, and cefiderocol susceptibility profile.

2.4. Mutation Analysis

2.4.1. Genes Involved in Iron Metabolism

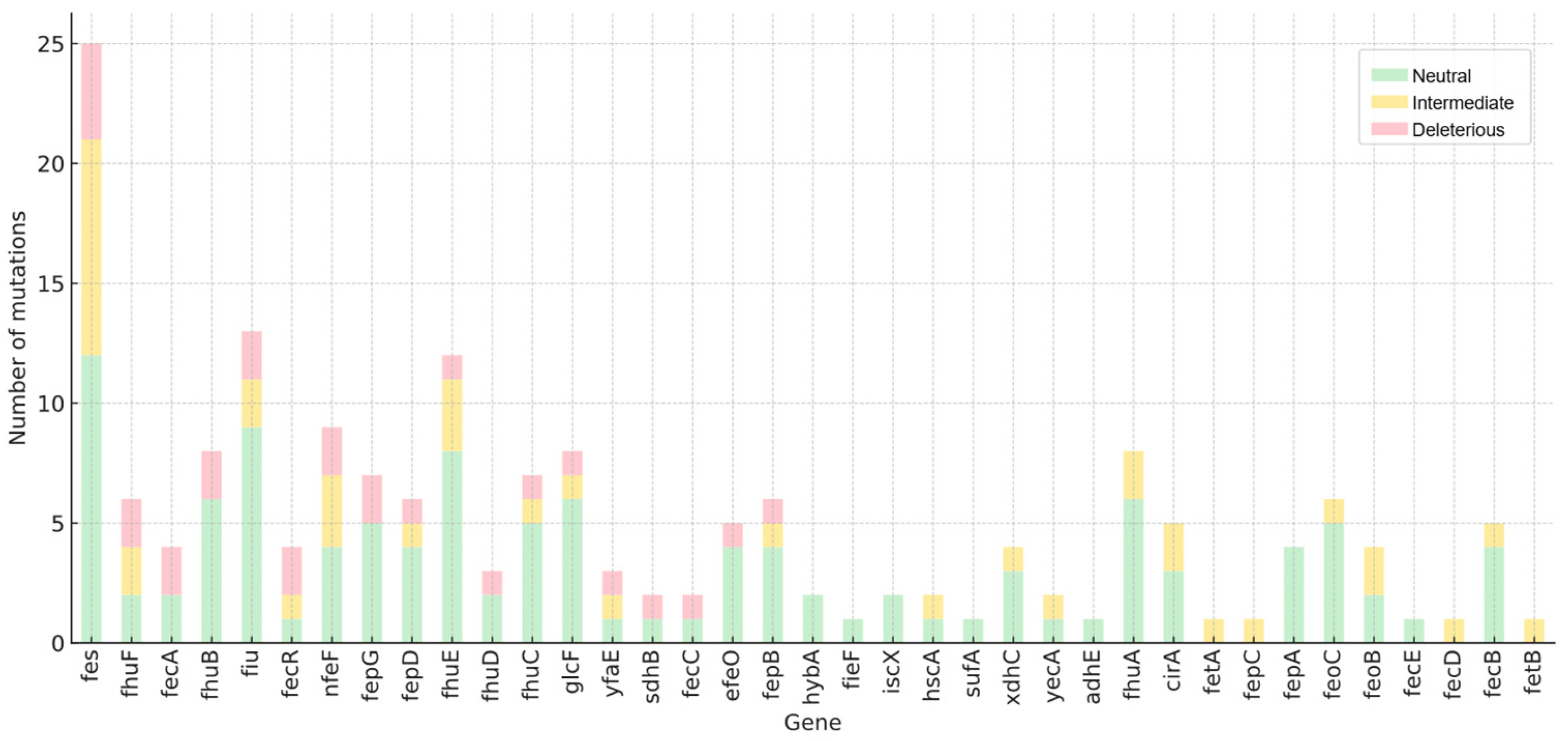

Functional annotation enabled the selection of genes associated with iron uptake and regulation at the cellular level. Using this list, genes bearing missense mutations were filtered in both groups based on nucleotide variant annotation. In the CFD-R group, 855 unique missense mutations were identified across 59 genes, with the fhu, fep, and fec operons showing the highest mutational burden.

Subsequently, mutations exclusive to the CFD-R group were selected to focus on biologically plausible mechanisms of CFD resistance. A total of 119 unique mutations were identified in seven key genes: fecB, fes, fiu, cirA, fhuC, nfeF, and fhuF (see Supplementary Material). Overall, the highest number of mutations were observed in fhuF, fes, and fiu with 82, 69, and 35 variants, respectively. Noteworthy high-prevalence mutations among isolates included V65A in fhuF, I57S in fes, and G465D in cirA. To determine whether the mutational burden in these genes represents a distinguishing feature of the CFD-R group, the total number of mutations per gene was compared between groups, revealing statistically significant differences in fecB, fes, fiu, cirA, fhu, nfeF, and fhuF (p<0.05).

After identifying the loci and differential mutations, we assessed whether these changes might indicate a loss of protein function by comparing the folding energy difference between the wild-type and mutant proteins. Due to the need for reference 3D models, this analysis was limited to

E. coli, whose proteome is a well-characterised. Mutations were classified as deleterious (>1.6 kcal/mol), intermediate (0.5–1.5 kcal/mol), or neutral (<0.5 kcal/mol) [

10]. In total, 182 nucleotide variants were found across 40 genes, of which 40 were considered intermediate and 28 deleterious (

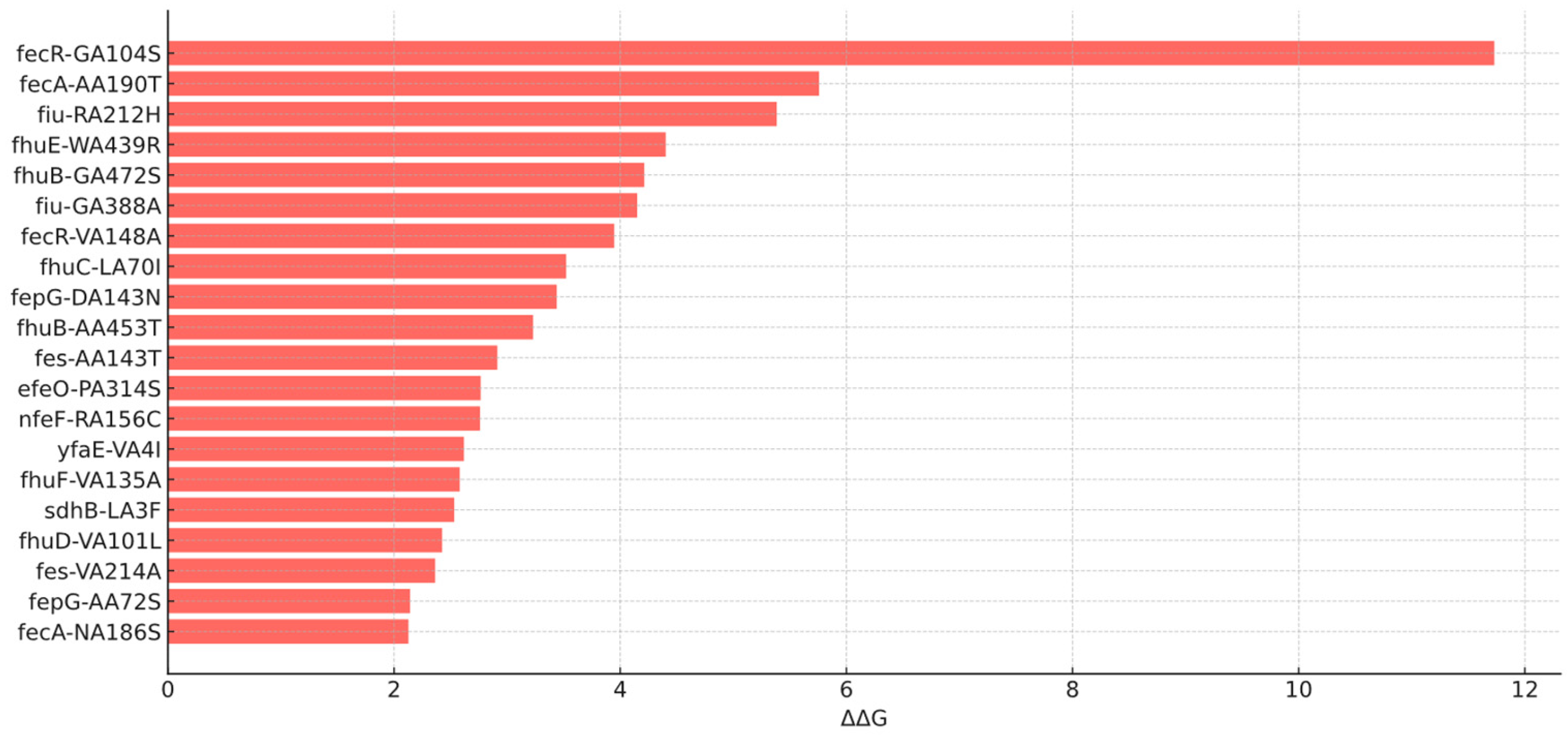

Figure 1). Among deleterious mutations (18 loci),

fecR:G104S,

fecA:A190T, and

fiu:R212H were those with the highest delta energy gap (ΔΔG) values of 11.7, 5.7, and 5.3 kcal/mol, respectively (

Figure 2). Average ΔΔG values per gene were also calculated, with

fecR,

fecA, and

sdhB exhibiting the highest averages of 4.1, 1.8, and 1.4 kcal/mol, respectively.

2.4.2. Penicillin-Binding Proteins (PBPs)

Using a similar approach, exclusive mutations were filtered for PBP1a, 1b, and 2–7, which corresponds to the mrcA, mrcB, mrdA, ftsI, dacB, dacA, dacC, and pbpG loci in E. coli. A total of 94 mutations were found across seven of these eight loci in the CFD-R group. Of these, 21 variants (distributed across PBP1a–PBP4) were exclusive to this group. PBP4 and PBP3 showed the highest number of unique variants accounting for seven and five, respectively.

Regarding structural impact, all PBP mutations were predicted to be neutral, except for mrcA:G414D, which showed a ΔΔG of 2.9 kcal/mol.

2.4.3. Efflux Pumps

Efflux pump systems are frequently associated with multidrug resistance. We catalogued all exclusive mutations in two major efflux systems in Enterobacteriaceae: AcrAB-TolC and OqxAB, including associated regulatory and structural components.

A total of 128 unique variants were identified, of which 97% belonged to the AcrAB-TolC system. Approximately 65% of these mutations were located in accessory genes such as acrD-F and acrR. Notably, 44% of the mutations were found in the acrR regulatory gene.

2.4.4. Allelic Variants in Carbapenemases and Class C Beta-lactamases

Certain mutations in beta-lactamase genes can alter their hydrolytic profiles conferring enhanced resistance. These changes have been primarily documented in carbapenemases and class C beta-lactamases, sometimes resulting in distinct allelic variants [

11].

In the resistant group, sequences of blaKPC-2, blaKPC-3, blaNDM-1, blaNDM-5, blaVIM-1, blaOXA-48, blaOXA-181, and blaOXA-244 were aligned against their respective references. All the aligned sequences showed 100% identity with the reference.

The analysis of class C beta-lactamases included both chromosomal and plasmid-mediated alleles: blaEC-8, blaEC-14, blaEC-15, blaACT-40, blaACT-52, blaACT-55, blaMIR-3, blaCMY-4, blaCMY-6, blaCMY-13, blaCMY-16, blaCMY-42, and blaCMY-181. After filtering out variants shared with the CFD-S group, mutations were detected in the blaEC alleles in seven E. coli isolates, as well as a duplication in blaACT-55 from E. hormaechei. Notably, blaEC-8 was exclusive to the CFD-R group.

Enhanced hydrolytic activity in AmpC beta-lactamases has often been linked to mutations within the Ω-loop [

12,

13]. We identified the R248C mutation in EC-14 and EC-15, as well as N201T, P209S, and S298I mutations in all EC-8 isolates. Of these, P209S is located close to α-helix 8, which configures the enzyme’s active site [

14]. In silico structural modelling predicted a root mean square deviation (RMSD) of 0.008 Å for the mutated protein compared to the wild type, indicating negligible structural disruption. Other mutations outside the Ω-loop included Q23K, P110S and A367T in EC-14/15 and T4M, S102I, Q196H, as well as T367A in EC-8.

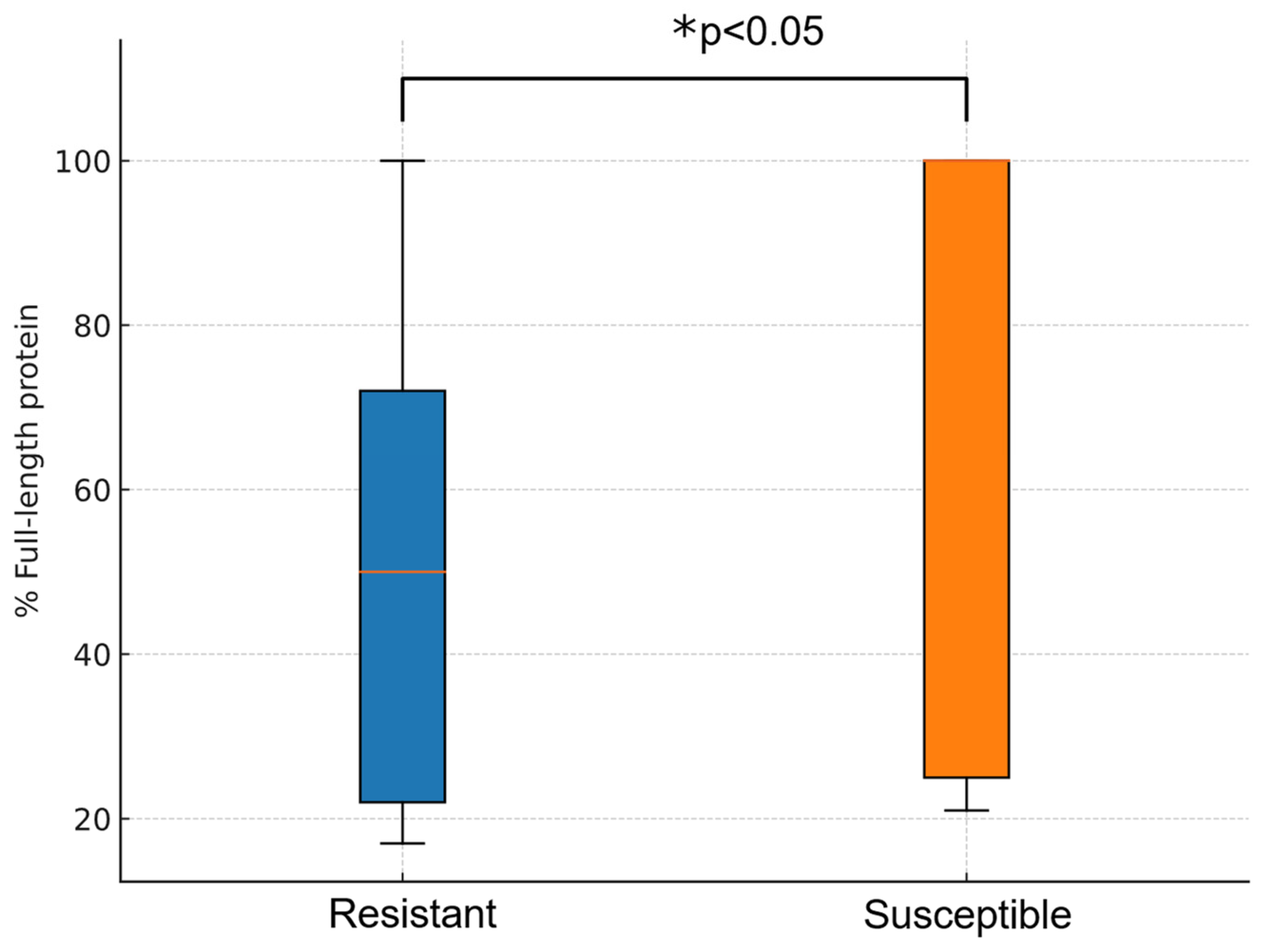

2.4.5. Porin Loss

Porin loss may act as a complementary mechanism in antibiotic resistance, especially OmpK35 and OmpK36 in

K. pneumoniae. Out of CFD-R isolates, 12 were found to harbour mutations resulting in truncated OmpK35 proteins with a predicted length of less than 75% of the wild-type sequence. Regarding mutations in loop 3 of OmpK36, GD deletion was identified in eight isolates and TD deletion in two. Additionally, one isolate exhibited a premature truncation of OmpK36, resulting in a peptide comprising less than 20% of the expected full-length protein. In contrast, only eight isolates in the CFD-S group showed any form of alteration in OmpK35 or OmpK36, representing a significantly lower frequency compared to the CFD-R group (p < 0.05). Moreover, the average predicted length of OmpK35 was higher in the CFD-S group (72.7%) compared to the resistant group (50.9%) (p < 0.05) (

Figure 2).

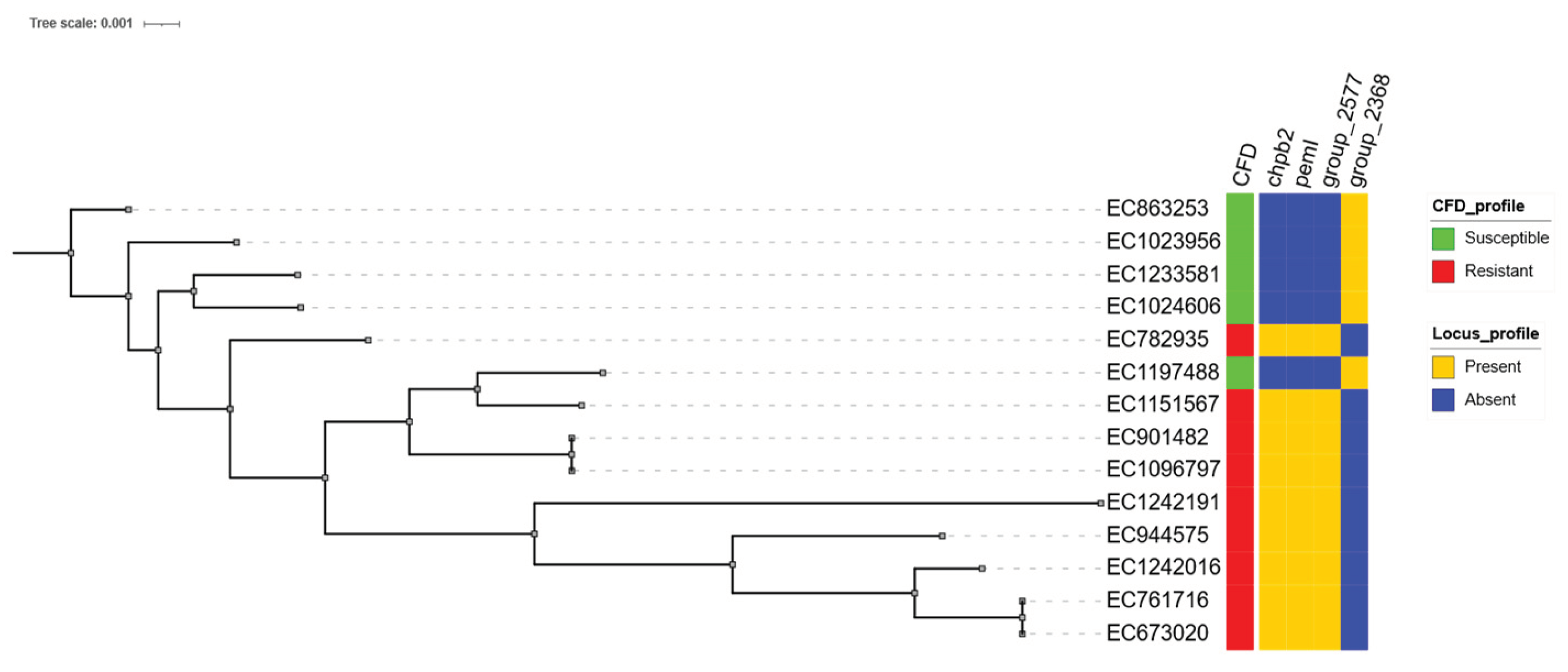

2.4.6. Pangenome Analysis

To enable a more comprehensive and unbiased investigation into the potential genes associated with cefiderocol resistance, a presence/absence analysis based on the pangenome of the isolates was conducted, comparing the CFD-R and CFD-S groups. Due to the number of isolates available for each species, this analysis was restricted to E. coli, K. pneumoniae, and E. hormaechei. Only group-exclusive loci—defined as genes present in all isolates of one group and absent from all isolates of the other—were considered.

Among the three species,

K. pneumoniae exhibited the largest pangenome, comprising 12,555 genes, followed by

E. coli with 11,839 and

E. hormaechei with 10,650. A similar distribution was observed for their core genomes. Notably, in both

K. pneumoniae and

E. coli, cloud genes—those present in fewer than 15% of isolates—accounted for 47.3% and 49.9% of the pangenome, respectively. This highlights substantial intraspecies variability and supports the presence of an open pangenome within the collection, consistent with findings from previous studies [

15]. Similarly, in

E. hormaechei, 80.8% of the pangenome consisted of shell genes (present in 15-95%of isolates), although this may reflect the limited number of isolates available for this species.

Regarding presence/absence analysis, no group-exclusive genes were identified in

K. pneumoniae or

E. hormaechei. However, in

E. coli, three loci were exclusive to the CFD-R group and one to the CFD-S group. The resistant-exclusive genes included

chpB2,

pemI, and a hypothetical protein internally annotated as group_2577 (

Figure 3), which exhibited 100% identity and coverage with a metalloprotease identified in the metallo-beta-lactamase-producing

E. coli strain EC_BZ_10 from Italy [

16]. The locus exclusive to the CFD-S group was also a hypothetical protein, designated

group_2368, with high sequence homology to a lipoprotein from

E. coli O139:H28 (strain E24377A / ETEC).

Table 2 summarises exclusive variants found in the resistant group by loci and resistance mechanism.

3. Discussion

This study compared the genomic differences between a collection of cefiderocol-resistant isolates and a set of susceptible isolates with similar characteristics. Although the absence of putative resistance determinants in the susceptible group does not imply causality, it serves as a useful filter to exclude findings that are unlikely related to resistance.

The main CPE species or CPE species complexes included in this study were K. pneumoniae, E. coli, and E. cloacae. Additional isolates included Citrobacter spp., Providencia spp., Morganella morganii, and Serratia sarumanii, the latter three being exclusive to the susceptible group. Although the total number of isolates was relatively limited, the groups were balanced both in overall count and species distribution. Moreover, the inclusion of multiple species adds biological diversity to the investigation of resistance mechanisms. All isolates were obtained from human samples, collected for clinical or epidemiological purposes, which strengthens the clinical relevance of the findings.

The higher rate of aztreonam susceptibility may be attributed to the high prevalence of metallo-beta-lactamases among the isolates. However, the co-occurrence of other beta-lactamases from classes A and C limits aztreonam’s effectiveness and confines its susceptibility rate to approximately 25%, thereby restricting its utility as a monotherapy option. In this context, non-beta-lactam antibiotics such as amikacin and colistin may gain importance as components of combination therapies in the absence of alternative treatment options, although their use is limited by a high incidence of adverse effects [

17].

The isolation of three strains from invasive clinical samples highlights the urgent need for effective therapeutic alternatives. Cefiderocol resistance, combined with the multidrug-resistant profiles exhibited by most isolates, significantly reduces the likelihood of effective treatment and worsens patient prognosis [

18]. A major limitation of this study is the lack of clinical data on CFD exposure in the patients from whom the isolates were obtained, which hinders the assessment of selective pressure that lead to resistance-associated mutations.

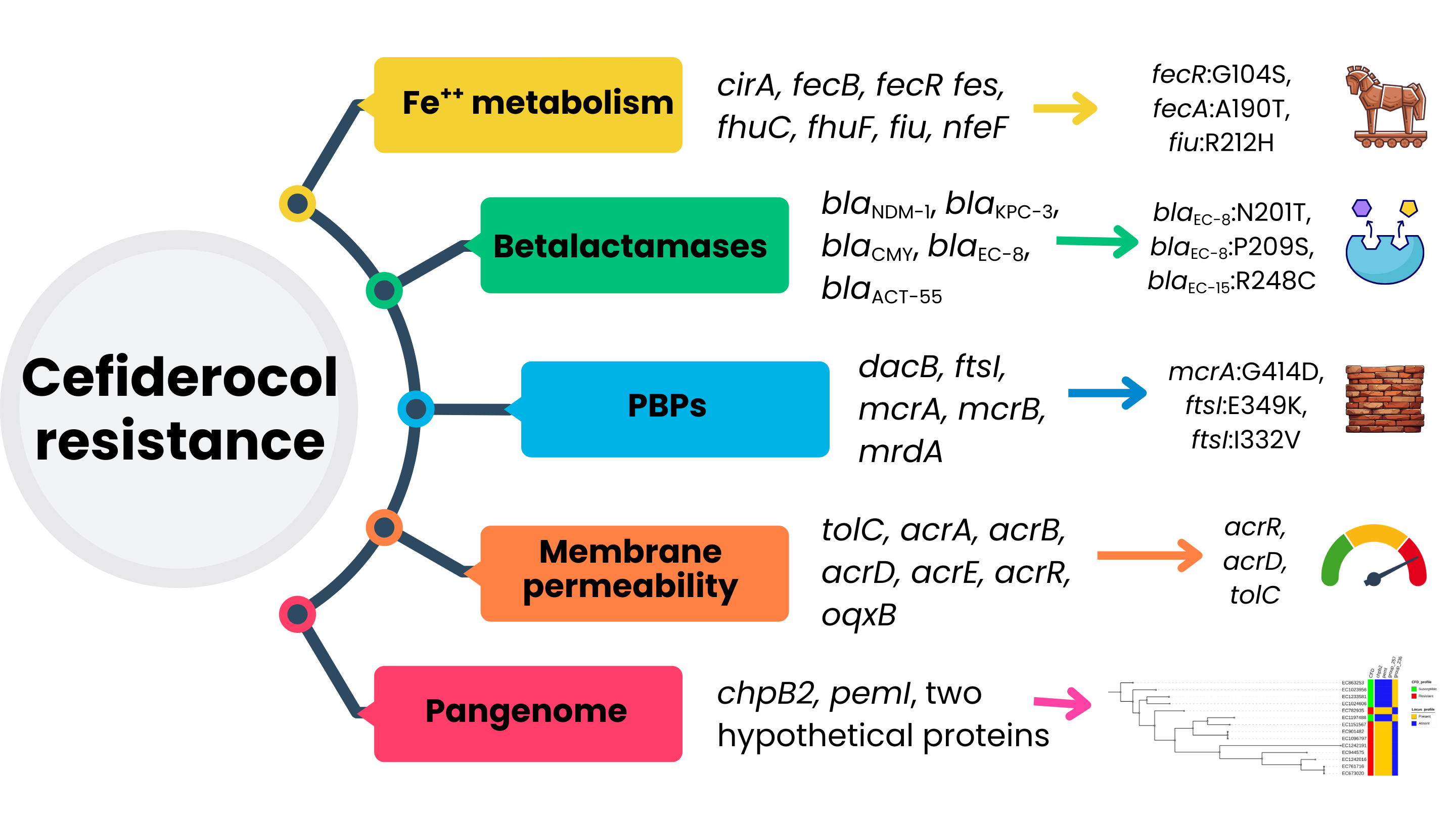

The current literature outlines four main mechanisms through which CFD resistance emerges in CPE: 1) mutations in genes related to iron transport systems 2) presence, mutation, or overexpression of certain beta-lactamases3) mutations in PBPs and 4) alterations in membrane permeability and active efflux [

5,

19]. The analyses conducted in this study were designed to address each of these categories.

3.1. Mutations in Genes Related to Iron Transport Systems

By mimicking the biological function of siderophores, CFD is highly dependent on intracellular iron transport systems in order to exert its antimicrobial activity [

1]. Therefore, a reduction in the expression or function of these proteins may contribute to its resistance.

The most notable differences observed when comparing the two groups, were reflected by a higher mutational burden in the genes

fecB,

fes,

fiu,

cirA,

fhu,

nfeF, and

fhuF. These genes have been previously reported as potential contributors to cefiderocol resistance [

20,

21,

22,

23], primarily in experimental models involving resistance induction assays and isogenic mutants, in which mutations have been shown to increase minimum inhibitory concentrations by 2- to 16-fold [

24]. In particular,

cirA has been identified in clinical isolates exhibiting resistance development during treatment [

25]. Our findings suggest that several mutations induced under laboratory conditions may indeed have a real-world impact in clinical, human-derived isolates.

Many of these genes operate in an interdependent manner or form part of well-characterised operons; thus, dysfunction in one component may compromise the system’s overall functionality. Moreover, the number of mutations in a given gene does not necessarily correlate with function loss. To address this issue, the energy difference (ΔΔG) associated with 182 variants across 40 loci in

E. coli resistant isolates was evaluated as an indirect indicator of loss of protein function. A total of 28 variants were predicted to be deleterious, affecting genes such as

efeO,

fecA,

fecC,

fecR,

fepB,

fepD,

fepG,

fes,

fhuB,

fhuC,

fhuD,

fhuE,

fhuF,

fiu,

glcF,

nfeF,

sdhB, and

yfaE (see

Figure 4). These mutations could result in misfolded or unstable proteins subject to degradation [

26], thereby impairing siderophore-mediated iron uptake into the periplasmic space and ultimately limiting the efficacy of cefiderocol.

For instance, in the fec operon, key functions such as the activity of the outer membrane siderophore (fecA) and the positive regulation of operon expression (fecR) were compromised by mutations associated with energy differences of 5.7 and 11.7 kcal/mol, respectively. The fhu operon also appeared significantly affected, with deleterious mutations impacting the entire sequence of iron acquisition (fhuE), transport (fhuD/B), and energy-dependent uptake (fhuC). These findings warrant experimental validation, especially for mutations predicted to be deleterious, in order to assess their direct impact on cefiderocol activity.

Such mutations may also influence bacterial fitness, as iron acquisition is essential for cell survival. However, this pathway is metabolically degenerate and includes redundant systems that may compensate for functional deficits by upregulating alternative receptors [

27] with a lower affinity for the chlorocatechol moiety of CFD.

3.2. Presence, Mutation, or Overexpression of Specific Beta-lactamases

Although CFD is stable against most beta-lactamases, the presence of certain enzymes has been associated with increased MICs and an increased likelihood for resistance development, particularly when combined with additional resistance mechanisms. In this regard, a higher prevalence (42–59%) of NDM-type metallo-beta-lactamases has been reported among cefiderocol-resistant isolates in several studies [

28,

29,

30]. In line with these findings,

blaNDM was more frequently detected in the resistant group, although it was also identified in approximately one-third of the CFD-S isolates. This observation likely reflects the local epidemiology of CPE in our setting [

31] and the fact that susceptibility to cefiderocol is more often tested in isolates exhibiting extensive resistance profiles.

Moreover, resistant isolates more frequently harboured multiple carbapenemase genes. Various

blaKPC allelic variants (e.g., blaKPC-31, blaKPC-33, blaKPC-41, blaKPC-50, blaKPC-25, blaKPC-29, blaKPC-44, blaKPC-121, blaKPC-203, blaKPC-109, blaKPC-216) have been associated with cefiderocol resistance in prior studies [

32,

33]. However, none of these variants were detected in our cohort. Likewise, we did not observe cross-resistance to ceftazidime-avibactam in isolates carrying class A carbapenemases, suggesting absence of enhance carbapenem hydrolytic variants, nor did we detect bla

OXA-427, another carbapenemase with potential cefiderocol hydrolytic activity [

34].

Variants of class C beta-lactamases have also been linked to cefiderocol resistance in Enterobacteriaceae, based both in vitro assays and clinical isolates. Notable examples include A292_L293del in EC, A313P and A292_L293del in ACT, and A114E, Q120K, V211S, and N346Y in CMY-2, as well as the presence of

blaCMY-186 in

K. pneumoniae [

19]. In our dataset, exclusive mutations of the resistant group were found in several allelic variants (i.e., EC-8, EC-14, EC-15, and ACT-55) none of which matched previously reported resistance-associated mutations (see

Table 2). Of particular interest is the P209S substitution located within the Ω-loop, a region known to influence the hydrolytic profile of beta-lactamases and confer resistance to agents such as ceftazidime-avibactam [

12]. However, its minimal impact on the three-dimensional configuration of the enzyme suggests that its functional effect is likely negligible. EC-8 was found exclusively in the resistant group, but its low prevalence limits any statistically meaningful association. Experimental studies are needed to assess the impact of these mutations on cefiderocol and other antibiotic susceptibility profiles.

Searching for beta-lactamase mutations using draft genomes may fail to detect low-frequency allelic variants not represented in the final assembly. However, mapping-based approaches pose additional challenges in this context, as these genes are often located on plasmids and complete reference sequences are lacking for many species. Moreover, low-frequency variants in genes that individually exert minor effects on antibiotic susceptibility are unlikely to alter group-level outcomes. It is noteworthy that blaNDM and blaKPC-3, both previously linked to elevated cefiderocol MICs, were more common among resistant isolates in our study.

No additional beta-lactamase genes previously associated with cefiderocol resistance in

Enterobacteriaceae—such as

CTX-M-27,

PER,

SPM-1,

BEL, or extended-spectrum

SHV variants—were detected [

5,

19].

Finally, although rare, the identification of such resistance-associated mutations holds clinical relevance, as they may confer cross-resistance to other next-generation beta-lactams such as ceftazidime-avibactam and ceftolozane-tazobactam. Their characterization through WGS is essential to inform the development of rapid, simplified molecular diagnostic tools for implementation in clinical microbiology laboratories.

3.3. Alterations in Penicillin-Binding Proteins (PBPs)

Sato and colleagues evaluated the impact of

insYRIN and

insYRIK insertions in

ftsI (encoding PBP3) in

E. coli isolates, reporting a two-fold increase in the cefiderocol MIC [

35]. Similarly, Price et al. identified the

insYRIN insertion during the genomic characterization of a collection of cefiderocol-resistant

E. coli isolates, observing a comparable elevation in MIC values [

3]. Since

ftsI is the target of most cephalosporins, it is reasonable to hypothesize that structural alterations in this protein may reduce its affinity for the antibiotic and thereby confer resistance. However, the available evidence suggests that such mutations may play only a marginal role in cefiderocol resistance and likely require the presence of additional mechanisms to exceed clinical breakpoints.

In our study, mutations exclusive to the CFD-R group were identified in

mrcA,

mrcB,

ftsI, and

dacB (see

Table 2). None of these were predicted to significantly impair the three-dimensional structure of the protein. Nevertheless, the absence of predicted structural disruption in these PBP mutations does not exclude their potential contribution to cefiderocol resistance. Unlike siderophore-related mechanisms, resistance in this context is not necessarily associated with loss of function, but rather with altered binding affinity of the antibiotic to the target protein.

In this regard, ftsI variants I332V and E349K warrant consideration due to their potential role in the active site conformation of the protein. It is plausible that only mutations capable of altering antibiotic affinity without compromising protein function would be selectively retained at the population level. Additional experimental studies are warranted to confirm the impact of these mutations on PBP function and binding affinity.

No isolates in our collection harbored the insYRIN or insYRIK insertions.

3.4. Alterations in Permeability and Active Efflux

Deletions in the outer membrane porins ompK35 and ompK36 have been associated with increased cefiderocol MICs in K. pneumoniae [

36]. This mechanism may be particularly relevant in iron-rich environments or in the presence of mutations affecting siderophore receptors. Additionally, mutations in ompK36 have been described in high-risk clones, leading to pore constriction and reduced permeability to multiple antibiotics [

37]. The marginal yet detectable impact of this mechanism on cefiderocol resistance is supported by the higher prevalence of such mutations (e.g., insGD, insTD or large deletions) in K. pneumoniae isolates from the resistant group, in line with findings reported by Simner et al. [

36]. This trend was especially pronounced in sequence types ST395 and ST512, which were prevalent in our collection and are known for their pronounced virulence and resistance profiles.

Another widely recognized resistance mechanism in

K. pneumoniae is active efflux via multidrug transporters. However, limited evidence is available regarding the specific role of the AcrAB-TolC and OqxAB systems in CFD resistance [

38]. In our study, a high frequency of mutations in the

acrR regulatory gene—part of the AcrAB efflux system—was observed in the resistant group, suggesting potential hyperactivation of this system and a possible contribution to antibiotic resistance, including CFD. These mutations were absent in the susceptible isolates.

The coexistence of such non-specific resistance mechanisms with others specifically targeting CFD may exert a synergistic effect in promoting resistance, especially when mutations in siderophore receptors coexist and the antibiotic must rely on traditional uptake pathways to reach the bacterial periplasm. Expression and functional studies are needed to fully elucidate the impact of these findings.

3.5. Pangenome Analysis

Finally, whole-genome association approaches, such as those proposed by Mosquera-Rendón et al., constitute a valuable strategy for generating hypotheses that canbe tested through targeted experiments and functional validations [

39]. In this regard, our analysis identified genes with predicted endoribonuclease activity that are, exclusively present in the CFD-R group and are linked to type II toxin–antitoxin systems (

chpB2 and

pemI), the latter also being associated with plasmid replication stability. Additionally, we identified two hypothetical coding sequences (CDSs), one exclusive to the resistant group and the other to the susceptible group, with putative functions consistent with a metalloprotease and a lipoprotein, respectively, based on homology analyses.

Although these loci may not be directly involved in cefiderocol resistance, their relevance lies in its potential to serve as surrogate markers of the resistant phenotype in specific species or clonal lineages, proven that these findings are validated in larger cohorts.

The main limitation of this study is the lack of parental (isogenic) strains, which precludes direct comparative genomics and limits the establishment of causal relationships, as resistance-associated mutations were identified and filtered out based on isolates with distinct genomic backgrounds.

4. Materials and Methods

Primary data regarding bacterial species, carbapenemase type, antimicrobial susceptibility profiles, and sample types from which the isolates were obtained were extracted from the Laboratory Information System (LIS) (SIGLO v2, Horus Software S.A.). All CPE isolates collected from January 1, 2022, to December 31, 2024, were reviewed. Only the first isolate per patient was considered. CFD susceptibility testing must have been performed during this period. All CPE isolates were recovered from human clinical or epidemiological samples submitted to the HUMS Laboratory as part of routine diagnostic procedures.

Inclusion criteria:

- a)

Strains belonging to the Enterobacteriaceae family

- b)

Strains with carbapenemase detection by phenotypic or molecular methods

Strains with informed CFD susceptibility Exclusion criteria:

- a)

No archived strain available

- b)

Non-viable archived strain

- c)

Contaminated archived strain

Bacterial strain archives were maintained in soy-tryptone broth supplemented with 20% glycerol at −80 °C. Subcultures were performed on Columbia blood agar (Oxoid™ Thermo Fisher, Waltham, MA, USA) and incubated at 35 °C for 24 hours to confirm species identity, validate CFD susceptibility, and increase biomass for whole-genome sequencing.

Species-level identification was performed following the manufacturer’s instructions using MALDI-TOF MS (Bruker Daltronics GmbH, Bremen, Germany). MALDI-TOF scores greater than 2.0 were considered valid.

CFD susceptibility testing was confirmed by disk diffusion on Müeller-Hinton agar using archived isolates, after confirming their identification. A second subculture was carried out on blood agar and incubated for 18–24 hours at 35 ± 1 °C under aerobic conditions. A 0.5 McFarland suspension was prepared in 0.9% saline and evenly spread onto the surface of Müeller-Hinton agar using a sterile swab. A Cefiderocol 30ug disk (Oxoid™ Cefiderocol disc, Oxoid Ltd., Wade Road, Basingstoke, Hampshire, RG24 8PW, United Kingdom) was placed at the centre of the plate, which was then incubated under aerobic conditions at 35 ± 1 °C. Results were read after 18 ± 2 hours and interpreted according to the EUCAST v15 criteria [

40].

Complementary antibiotic susceptibility testing was performed using the broth microdilution method with the MicroScan™ WalkAway semi-automated system (Beckman Coulter, Brea, CA, USA). Results were interpreted according to EUCAST guidelines version 15.

CPE isolates from clinical samples were identified either by immunochromatographic assays (NG-Test® CARBA 5, NG-Biotech Laboratories, Guipry-Messac, France) or by genotypic methods using isothermal amplification (Eazyplex®, Amplex Diagnostics GmbH, Gars am Inn, Germany) or the FilmArray® system (BioFire Diagnostics LLC, Salt Lake City, UT, USA), depending on the case and in accordance with the laboratory’s internal protocols. All strains that tested positive by molecular methods for carbapenemase genes were classified as CPE, regardless of their minimum inhibitory concentration to carbapenems.

Epidemiological samples were initially screened for carbapenem resistance using Brilliance™ CRE chromogenic selective medium (Oxoid Limited, Basingstoke, UK). Confirmation of presumptive CPE was achieved via NG-Test® CARBA 5 or real-time PCR using the Xpert® Carba-R assay (Cepheid, Sunnyvale, CA, USA).

All identified CPE isolates with a pure and viable archived culture were eligible for WGS. Genomic DNA was extracted from 60 to 80 isolated colonies using a magnetic capture-based protocol with the MagCore® system (RBC Bioscience, New Taipei City, Taiwan), following the manufacturer’s instructions, yielding 60 μL of eluate. Sequencing libraries were prepared using the Nextera XT™ DNA Library Prep Kit (Illumina Inc., San Diego, CA, USA). DNA concentration and quality were assessed throughout the process using Qubit™ fluorometric quantification (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.) and Bioanalyzer™ analysis (Agilent Technologies, Inc., Santa Clara, CA, USA). Samples with DNA concentrations below 2 ng/μL or insert size distributions outside the 300 ± 50 bp range were excluded.

Sequencing was performed on an Illumina® MiSeq™ platform using MiSeq V2 300-cycle reagent kits (Illumina Inc., San Diego, CA, USA), applying a 150 bp paired-end protocol with a targeted average sequencing depth greater than 50X. Libraries were loaded at a concentration of 12.5 pM, including 5% PhiX as a sequencing quality control.

De novo genome assembly was performed using Unicycler v0.5.1 [

41]. Structural and functional quality of the assemblies was assessed using QUAST v5.2.0 [

42] and BUSCO v5.6.1 [

43], respectively. Assemblies were excluded based on the following quality criteria: fewer than 800,000 reads with a median Phred quality score below 28, more than 10% undetermined bases (Ns), an N50 value less than 30,000, or an assembled genome size falling outside the expected range of 5.5 ± 1.5 Mb. Contamination in raw reads and assembled genomes was evaluated using Mash v2.3 [

44] and GUNC v1.0 [

45], respectively. Final assembly graphs were manually reviewed using Bandage v0.8.1 [

46]. Data were submitted to GenBank on 15 May 2025 under Submission ID SUB15324465. Sequences can be found under BioProject accession PRJNA1263540 and PRJNA1190923.

Species-level identification was confirmed using GAMBIT v1.0.1 [

47] and the PubMLST online species identification tool [

48] (

https://pubmlst.org/species-id, accessed on 01 February 2025). Multi-locus sequence typing was performed using mlst v2.23.0 [

49], except for

K. pneumoniae, which was analysed separately. For

Klebsiella species, MLST typing, resistance, and virulence gene annotation were conducted using Kleborate v3.1.3 [

50]. Structural genome annotation was performed using Prokka v1.14.6 [

51], and functional annotation was conducted with Sma3s v2 [

52] using the UniRef90 database. Resistance genes were identified using RGI v6.0.3 against the CARD v4.0.0 database [

53]. Resistance determinants with >80% coverage and >95% identity were retained for analysis.

Plasmidome assembly and characterization were performed using MOB-suite v3.1.9 [

54]. Further annotation of plasmid content was conducted using RGI v6.0.3 (CARD v4.0.0), and visualization of the plasmidome was carried out using Proksee (

https://proksee.ca/, accessed on 05 March 2025).

The pangenome was calculated separately for resistant and susceptible isolates of

K. pneumoniae,

E. coli, and

E. hormaechei using Roary v3.11.2 [

55]. Presence/Absence analysis was carried out with scoary v1.6.16 [

56]. Results were visualized with Phandango v1.3.1 (

https://jameshadfield.github.io/phandango/#/, accessed on 15 March 2025). Core genome alignment was performed with MAFFT v7.505 [

57], and phylogenetic reconstruction was carried out using FastTree v2.1.11 [

58].

Amino acid variant analysis of class C beta-lactamases and carbapenemases was performed in both groups by aligning the protein sequences (translated from nucleotide sequences) and manually inspecting them using MEGA12 v12.0.10 [

59]. The reference sequences for each beta-lactamase are detailed in the

Supplementary Table S1. Subsequently, only variants present in the resistant group and absent from the cefiderocol-susceptible group were selected. The root mean square deviation induced by the P209S substitution in the Ω-loop of EC-8 was calculated using PyMOL v3.1.4.1 (Schrödinger, LLC. The PyMOL Molecular Graphics System, 2015), based on the predicted three-dimensional structure of EC-8 obtained from SWISS-MODEL (

https://swissmodel.expasy.org/interactive, accessed on 20 March 2025).

Truncation levels of OmpK35 and OmpK36 and the presence of GD and TD deletions in OmpK36 from K. pneumoniae isolates were assessed by extracting and translating the respective gene sequences from annotations, aligning them to their homologs in the reference strain Klebsiella pneumoniae subsp. pneumoniae HS11286, and performing manual inspection using the tools described above.

Single nucleotide variant (SNV) detection was performed via mapping and variant calling using Snippy v4.6.0 [

60]. Detected variants were annotated with SnpEff v5.0 [

61]. Custom in-house scripts were used to filter and retain all non-synonymous variants located in genes related to iron metabolism, PBPs, and the efflux systems

acr,

tolC, and

oqx. Further filtering retained only those variants exclusively present in resistant isolates and absent from susceptible ones. The reference genomes used for each species are listed in the

Supplementary Table S2.

ΔΔG energy shifts caused by the identified nucleotide variants were calculated using the BuildModel function from FoldX v5.0 [

62], using as referencethe three-dimensional structures of the corresponding proteins from

Escherichia coli K12, as predicted by the AlphaFold Protein Structure Database (

https://alphafold.ebi.ac.uk/, accessed on 22 March 2025).

Inferential statistical analyses were conducted using various functions from the rstatix v0.7.2 package in R v4.4.2.

5. Conclusions

This study reinforces the concept that cefiderocol resistance is multifactorial in nature, identifying multiple loci that are potentially involved in a variety of clinical isolates from human-derived bacteria. The detection of exclusive mutations in siderophore-related genes with predicted structural impact supports the hypothesis that evasion of the drug’s “trojan horse” entry mechanism is a key driver of resistance, particularly through alterations in the fec, fhu, and cir operons, as well as the presence of specific beta-lactamases, notably NDM-type metallo-beta-lactamases.

Other elements, such as modifications in penicillin-binding proteins (PBPs), altered membrane permeability (e.g., loss of OmpK35/36), and upregulation of efflux systems like AcrAB, may act as complementary resistance mechanisms.

We are likely entering a new era in the study of antimicrobial resistance, in which traditional resistance models based on single-gene are giving way to more complex, multifactorial mechanisms. This highlights the value of omics-based approaches to better understand emerging bacterial resistance pathways and to guide the development of new countermeasures. Future efforts should move beyond the resistome and incorporate comprehensive genomic surveillance and functional validation platforms in the study of multidrug-resistant pathogens, while also encouraging the engagement of clinical teams dedicated to the management of difficult to treat infections.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: Preprints.org., Table S1: Betalactamases references used for comparative analysis; Table S2: Reference genomes used for comparative analysis.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Alexander Tristancho-Baró, Carmen Torres, PhD and Antonio Rezusta; Data curation, Alexander Tristancho-Baró, Mónica Ariza, Victor Viñeta and David Badenas-Alzugaray; Formal analysis, Alexander Tristancho-Baró, Mónica Ariza, Victor Viñeta, Miriam Latorre-Millán, Laura Clusa, Rosa Martínez, Carmen Torres, PhD and Antonio Rezusta; Investigation, Alexander Tristancho-Baró, Ana López-Calleja, Ana María Milagro, Mónica Ariza, Victor Viñeta and David Badenas-Alzugaray; Methodology, Alexander Tristancho-Baró, Ana López-Calleja, Ana María Milagro, Carmen Torres, PhD and Antonio Rezusta; Project administration, Alexander Tristancho-Baró and Antonio Rezusta; Resources, Ana López-Calleja, Ana María Milagro, Blanca Fortuño, Concha López, Rosa Martínez and Antonio Rezusta; Software, Alexander Tristancho-Baró and David Badenas-Alzugaray; Supervision, Carmen Torres, PhD and Antonio Rezusta; Validation, Ana López-Calleja, Ana María Milagro, Blanca Fortuño, Concha López, Rosa Martínez, Carmen Torres, PhD and Antonio Rezusta; Visualization, Alexander Tristancho-Baró, Miriam Latorre-Millán and Laura Clusa; Writing – original draft, Alexander Tristancho-Baró, Ana López-Calleja, Ana María Milagro, Miriam Latorre-Millán, Laura Clusa, Carmen Torres, PhD and Antonio Rezusta; Writing – review & editing, Alexander Tristancho-Baró, Miriam Latorre-Millán, Laura Clusa, Carmen Torres, PhD and Antonio Rezusta. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the local institutional ethics committee “Comité de Ética de la Investigación de la Comunidad Autónoma de Aragón (CEICA)”, with protocol code PI25-121 and approval date 09 April 2024 in record no. 07/2025. The study was conducted in accordance with local regulations (Spain), including compliance with the requirements of Law 14/2007, of 3 July, on Biomedical Research, and the applicable ethical principles.

Informed Consent Statement

Exemption of informed consent for the collection of retrospective data was accepted by the local institutional ethics committee “Comité de Ética de la Investigación de la Comunidad Autónoma de Aragón (CEICA)” protocol code PI25/121 and approval date 09 April 2024 in record no. 07/2025.

Data Availability Statement

Data were submitted to GenBank on 15 May 2025 under Submission ID SUB15324465. Sequences can be found under BioProject accession PRJNA1263540 and PRJNA1190923.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank the Microbiology Laboratory of HUMS, especially the laboratory technicians, for their assistance in processing samples for clinical diagnostic purposes. We would also like to extend our gratitude to the Infectious Diseases Department for their close collaboration with the laboratory in the treatment of infections caused by CPE.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Sato, T.; Yamawaki, K. Cefiderocol: Discovery, Chemistry, and In Vivo Profiles of a Novel Siderophore Cephalosporin. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2019, 69 (Suppl. 7), S538–S543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Katsube, T.; Echols, R.; Wajima, T. Pharmacokinetic and Pharmacodynamic Profiles of Cefiderocol, a Novel Siderophore Cephalosporin. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2019, 69 (Suppl. 7), S552–S558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Price, T.K.; Davar, K.; Contreras, D.; Ward, K.W.; Garner, O.B.; Simner, P.J.; Yang, S.; Chandrasekaran, S. Case Report and Genomic Analysis of Cefiderocol-Resistant Escherichia coli Clinical Isolates. Am. J. Clin. Pathol. 2022, 157, 257–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haidar, G.; Kline, E.G.; Kitsios, G.D.; Wang, X.; Kwak, E.J.; Newbrough, A.; Friday, K.; Kramer, K.H.; Shields, R.K. Emergence of high-level aztreonam–avibactam and cefiderocol resistance following treatment of an NDM-producing Escherichia coli bloodstream isolate exhibiting reduced susceptibility to both agents at baseline. JAC-Antimicrobial Resist. 2024, 6, dlae141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karakonstantis, S.; Rousaki, M.; Kritsotakis, E.I. Cefiderocol: Systematic Review of Mechanisms of Resistance, Heteroresistance and In Vivo Emergence of Resistance. Antibiotics 2022, 11, 723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wunderink, R.G.; Matsunaga, Y.; Ariyasu, M.; Clevenbergh, P.; Echols, R.; Kaye, K.S.; Kollef, M.; Menon, A.; Pogue, J.M.; Shorr, A.F.; et al. Cefiderocol versus high-dose, extended-infusion meropenem for the treatment of Gram-negative nosocomial pneumonia (APEKS-NP): a randomised, double-blind, phase 3, non-inferiority trial. Lancet Infect. Dis. 2021, 21, 213–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bassetti, M.; Echols, R.; Matsunaga, Y.; Ariyasu, M.; Doi, Y.; Ferrer, R.; Lodise, T.P.; Naas, T.; Niki, Y.; Paterson, D.L.; et al. Efficacy and safety of cefiderocol or best available therapy for the treatment of serious infections caused by carbapenem-resistant Gram-negative bacteria (CREDIBLE-CR): a randomised, open-label, multicentre, pathogen-focused, descriptive, phase 3 trial. Lancet Infect. Dis. 2021, 21, 226–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- lvarez-Lerma F, Catalán-González M, Álvarez J, Sánchez-García M, Palomar-Martínez M, Fernández-Moreno I, et al. Impact of the “Zero Resistance” program on acquisition of multidrug-resistant bacteria in patients admitted to Intensive Care Units in Spain. A prospective, intervention, multimodal, multicenter study. Med Intensiva Engl Ed. 2023 Apr;47(4):193–202.

- Ambler, R. The structure of b-lactamases. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci. 16(289):321–31.

- Guerois, R.; Nielsen, J.E.; Serrano, L. Predicting Changes in the Stability of Proteins and Protein Complexes: A Study of More Than 1000 Mutations. J. Mol. Biol. 2002, 320, 369–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang X, Xie Y, Zhang Y, Lei T, Zhou L, Yao J, et al. Evolution of ceftazidime–avibactam resistance driven by mutations in double-copy blaKPC-2 to blaKPC-189 during treatment of ST11 carbapenem-resistant Klebsiella pneumoniae. Dong X, editor. mSystems. 2024 Oct 22;9(10):e00722-24.

- Endimiani, A.; Doi, Y.; Bethel, C.R.; Taracila, M.; Adams-Haduch, J.M.; O’keefe, A.; Hujer, A.M.; Paterson, D.L.; Skalweit, M.J.; Page, M.G.P.; et al. Enhancing Resistance to Cephalosporins in Class C β-Lactamases: Impact of Gly214Glu in CMY-2. Biochemistry 2010, 49, 1014–1023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nordmann, P.; Shields, R.K.; Doi, Y.; Takemura, M.; Echols, R.; Matsunaga, Y.; Yamano, Y. Mechanisms of Reduced Susceptibility to Cefiderocol Among Isolates from the CREDIBLE-CR and APEKS-NP Clinical Trials. Microb. Drug Resist. 2022, 28, 398–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacoby, GA. AmpC β-Lactamases. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2009 Jan;22(1):161–82.

- Dey, S.; Gaur, M.; Sykes, E.M.E.; Prusty, M.; Elangovan, S.; Dixit, S.; Pati, S.; Kumar, A.; Subudhi, E. Unravelling the Evolutionary Dynamics of High-Risk Klebsiella pneumoniae ST147 Clones: Insights from Comparative Pangenome Analysis. Genes 2023, 14, 1037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bianconi, I.; Spath, M.; Aschbacher, R.; Pedron, R.; Wieser, S.; Pagani, E. Characterization of Verona Integron-Encoded Metallo-β-Lactamase-Type Carbapenemase-Producing Escherichia coli Isolates Collected over a 16-Year Period in Bolzano (Northern Italy). Microb. Drug Resist. 2023, 30, 91–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Spapen, H.; Jacobs, R.; Van Gorp, V.; Troubleyn, J.; Honoré, P.M. Renal and neurological side effects of colistin in critically ill patients. Ann. Intensiv. Care 2011, 1, 14–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, D.; Park, B.Y.; Choi, M.H.; Yoon, E.-J.; Lee, H.; Lee, K.J.; Park, Y.S.; Shin, J.H.; Uh, Y.; Shin, K.S.; et al. Antimicrobial resistance and virulence factors of Klebsiella pneumoniae affecting 30 day mortality in patients with bloodstream infection. J Antimicrob Chemother [Internet]. 2018 Oct 5 [cited 2024 Nov 23]; Available from: https://academic.oup.com/jac/advance-article/doi/10.1093/jac/dky397/5116214.

- Bianco, G.; Boattini, M.; Cricca, M.; Diella, L.; Gatti, M.; Rossi, L.; Bartoletti, M.; Sambri, V.; Signoretto, C.; Fonnesu, R.; et al. Updates on the Activity, Efficacy and Emerging Mechanisms of Resistance to Cefiderocol. Curr. Issues Mol. Biol. 2024, 46, 14132–14153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Padovani, M.; Bertelli, A.; Corbellini, S.; Piccinelli, G.; Gurrieri, F.; De Francesco, M.A. In Vitro Activity of Cefiderocol on Multiresistant Bacterial Strains and Genomic Analysis of Two Cefiderocol Resistant Strains. Antibiotics 2023, 12, 785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bao, J.; Xie, L.; Ma, Y.; An, R.; Gu, B.; Wang, C. Proteomic and Transcriptomic Analyses Indicate Reduced Biofilm-Forming Abilities in Cefiderocol-Resistant Klebsiella pneumoniae. Front. Microbiol. 2022, 12, 778190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nurjadi, D.; Kocer, K.; Chanthalangsy, Q.; Klein, S.; Heeg, K.; Boutin, S. New Delhi Metallo-Beta-Lactamase Facilitates the Emergence of Cefiderocol Resistance in Enterobacter cloacae. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2021, 66, e0201121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McElheny, C.L.; Fowler, E.L.; Iovleva, A.; Shields, R.K.; Doi, Y. In Vitro Evolution of Cefiderocol Resistance in an NDM-Producing Klebsiella pneumoniae Due to Functional Loss of CirA. Microbiol. Spectr. 2021, 9, e0177921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ito A, Sato T, Ota M, Takemura M, Nishikawa T, Toba S, et al. In Vitro Antibacterial Properties of Cefiderocol, a Novel Siderophore Cephalosporin, against Gram-Negative Bacteria. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2018 Jan;62(1):e01454-17.

- Klein, S.; Boutin, S.; Kocer, K.; O Fiedler, M.; Störzinger, D.; A Weigand, M.; Tan, B.; Richter, D.; Rupp, C.; Mieth, M.; et al. Rapid Development of Cefiderocol Resistance in Carbapenem-resistant Enterobacter cloacae During Therapy Is Associated With Heterogeneous Mutations in the Catecholate Siderophore Receptor cirA. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2022, 74, 905–908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Govers, S.K.; Mortier, J.; Adam, A.; Aertsen, A. Protein aggregates encode epigenetic memory of stressful encounters in individual Escherichia coli cells. PLOS Biol. 2018, 16, e2003853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chu, B.C.; Garcia-Herrero, A.; Johanson, T.H.; Krewulak, K.D.; Lau, C.K.; Peacock, R.S.; Slavinskaya, Z.; Vogel, H.J. Siderophore uptake in bacteria and the battle for iron with the host; a bird’s eye view. BioMetals 2010, 23, 601–611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mushtaq S, Sadouki Z, Vickers A, Livermore DM, Woodford N. In Vitro Activity of Cefiderocol, a Siderophore Cephalosporin, against Multidrug-Resistant Gram-Negative Bacteria. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2020 Nov 17;64(12):e01582-20.

- Hackel, M.A.; Tsuji, M.; Yamano, Y.; Echols, R.; Karlowsky, J.A.; Sahm, D.F. In Vitro Activity of the Siderophore Cephalosporin, Cefiderocol, against Carbapenem-Nonsusceptible and Multidrug-Resistant Isolates of Gram-Negative Bacilli Collected Worldwide in 2014 to 2016. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2018, 62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Longshaw, C.; Manissero, D.; Tsuji, M.; Echols, R.; Yamano, Y. In vitroactivity of the siderophore cephalosporin, cefiderocol, against molecularly characterized, carbapenem-non-susceptible Gram-negative bacteria from Europe. JAC-Antimicrobial Resist. 2020, 2, dlaa060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tristancho-Baró, A.; Franco-Fobe, L.E.; Ariza, M.P.; Milagro, A.; López-Calleja, A.I.; Fortuño, B.; López, C.; Latorre-Millán, M.; Clusa, L.; Martínez, R.; et al. Genomic Characterization of Carbapenemase-Producing Enterobacteriaceae from Clinical and Epidemiological Human Samples. Antibiotics 2025, 14, 42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Poirel, L.; Sadek, M.; Kusaksizoglu, A.; Nordmann, P. Co-resistance to ceftazidime-avibactam and cefiderocol in clinical isolates producing KPC variants. Eur. J. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 2022, 41, 677–680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tiseo G, Falcone M, Leonildi A, Giordano C, Barnini S, Arcari G, et al. Meropenem-Vaborbactam as Salvage Therapy for Ceftazidime-Avibactam-, Cefiderocol-Resistant ST-512 Klebsiella pneumoniae –Producing KPC-31, a D179Y Variant of KPC-3. Open Forum Infect Dis. 2021 Jun 1;8(6):ofab141.

- Jacob, A.-S.; Chong, G.-L.; Lagrou, K.; Depypere, M.; Desmet, S. No in vitro activity of cefiderocol against OXA-427-producing Enterobacterales. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2021, 76, 3317–3318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sato, T.; Ito, A.; Ishioka, Y.; Matsumoto, S.; Rokushima, M.; Kazmierczak, K.M.; Hackel, M.; Sahm, D.F.; Yamano, Y. Escherichia coli strains possessing a four amino acid YRIN insertion in PBP3 identified as part of the SIDERO-WT-2014 surveillance study. JAC-Antimicrobial Resist. 2020, 2, dlaa081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simner, P.J.; Beisken, S.; Bergman, Y.; Ante, M.; Posch, A.E.; Tamma, P.D. Defining Baseline Mechanisms of Cefiderocol Resistance in the Enterobacterales. Microb. Drug Resist. 2022, 28, 161–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- David, S.; Wong, J.L.C.; Sanchez-Garrido, J.; Kwong, H.-S.; Low, W.W.; Morecchiato, F.; Giani, T.; Rossolini, G.M.; Brett, S.J.; Clements, A.; et al. Widespread emergence of OmpK36 loop 3 insertions among multidrug-resistant clones of Klebsiella pneumoniae. PLOS Pathog. 2022, 18, e1010334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Padilla, E.; Llobet, E.; Doménech-Sánchez, A.; Martínez-Martínez, L.; Bengoechea, J.A.; Albertí, S. Klebsiella pneumoniae AcrAB Efflux Pump Contributes to Antimicrobial Resistance and Virulence. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2010, 54, 177–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mosquera-Rendón, J.; Moreno-Herrera, C.X.; Robledo, J.; Hurtado-Páez, U. Genome-Wide Association Studies (GWAS) Approaches for the Detection of Genetic Variants Associated with Antibiotic Resistance: A Systematic Review. Microorganisms 2023, 11, 2866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- The European Committee on Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing. Breakpoint Tables for Interpretation of MICs and Zone Diameters, Version 15 [Internet]. 2025. Available online: http://www.eucast.org/clinical_breakpoints (accessed on 1 January 2020).

- Wick, R.R.; Judd, L.M.; Gorrie, C.L.; Holt, K.E. Unicycler: Resolving bacterial genome assemblies from short and long sequencing reads. PLoS Comput. Biol. 2017, 13, e1005595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gurevich, A.; Saveliev, V.; Vyahhi, N.; Tesler, G. QUAST: quality assessment tool for genome assemblies. Bioinformatics 2013, 29, 1072–1075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seppey M, Manni M, Zdobnov EM. BUSCO: Assessing Genome Assembly and Annotation Completeness. In: Kollmar M, editor. Gene Prediction [Internet]. New York, NY: Springer New York; 2019 [cited 2024 Nov 24]. p. 227–45. (Methods in Molecular Biology; vol. 1962). Available from: http://link.springer.com/10.1007/978-1-4939-9173-0_14.

- Ondov, B.D.; Starrett, G.J.; Sappington, A.; Kostic, A.; Koren, S.; Buck, C.B.; Phillippy, A.M. Mash Screen: high-throughput sequence containment estimation for genome discovery. Genome Biol. 2019, 20, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Orakov A, Fullam A, Coelho LP, Khedkar S, Szklarczyk D, Mende DR, et al. GUNC: detection of chimerism and contamination in prokaryotic genomes. Genome Biol. 2021 Dec;22(1):178.

- Wick, R.R.; Schultz, M.B.; Zobel, J.; Holt, K.E. Bandage: interactive visualization of de novo genome assemblies. Bioinformatics 2015, 31, 3350–3352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lumpe, J.; Gumbleton, L.; Gorzalski, A.; Libuit, K.; Varghese, V.; Lloyd, T.; Tadros, F.; Arsimendi, T.; Wagner, E.; Stephens, C.; et al. GAMBIT (Genomic Approximation Method for Bacterial Identification and Tracking): A methodology to rapidly leverage whole genome sequencing of bacterial isolates for clinical identification. PLOS ONE 2023, 18, e0277575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jolley, K.A.; Bray, J.E.; Maiden, M.C.J. Open-access bacterial population genomics: BIGSdb software, the PubMLST.org website and their applications. Wellcome Open Res. 2018, 3, 124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seeman, T. MLST; GitHub: San Francisco, CA, USA. Available online: https://github.com/tseemann/mlst (accessed on 25 June 2020).

- Lam, M.M.C.; Wick, R.R.; Watts, S.C.; Cerdeira, L.T.; Wyres, K.L.; Holt, K.E. A genomic surveillance framework and genotyping tool for Klebsiella pneumoniae and its related species complex. Nat. Commun. 2021, 12, 4188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seemann, T. Prokka: Rapid Prokaryotic Genome Annotation. Bioinformatics 2014, 30, 2068–2069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casimiro-Soriguer, C.S.; Muñoz-Mérida, A.; Pérez-Pulido, A.J. Sma3s: A universal tool for easy functional annotation of proteomes and transcriptomes. Proteomics 2017, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alcock, B.P.; Huynh, W.; Chalil, R.; Smith, K.W.; Raphenya, A.R.; A Wlodarski, M.; Edalatmand, A.; Petkau, A.; A Syed, S.; Tsang, K.K.; et al. CARD 2023: expanded curation, support for machine learning, and resistome prediction at the Comprehensive Antibiotic Resistance Database. Nucleic Acids Res. 2023, 51, D690–D699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Robertson, J.; Nash, J.H.E. MOB-suite: software tools for clustering, reconstruction and typing of plasmids from draft assemblies. Microb. Genom. 2018, 4, e000206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Page, A.J.; Cummins, C.A.; Hunt, M.; Wong, V.K.; Reuter, S.; Holden, M.T.G.; Fookes, M.; Falush, D.; Keane, J.A.; Parkhill, J. Roary: Rapid large-scale prokaryote pan genome analysis. Bioinformatics 2015, 31, 3691–3693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brynildsrud O, Bohlin J, Scheffer L, Eldholm V. Rapid scoring of genes in microbial pan-genome-wide association studies with Scoary. Genome Biol. 2016 Dec;17(1):238.

- Katoh, K.; Standley, D.M. MAFFT Multiple Sequence Alignment Software Version 7: Improvements in Performance and Usability. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2013, 30, 772–780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Price, M.N.; Dehal, P.S.; Arkin, A.P. FastTree 2—Approximately Maximum-Likelihood Trees for Large Alignments. PLoS ONE 2010, 5, e9490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tamura K, Stecher G, Kumar S. MEGA11: Molecular Evolutionary Genetics Analysis Version 11. Battistuzzi FU, editor. Mol Biol Evol. 2021 Jun 25;38(7):3022–7.

- Seemann, T.; Snippy: Rapid Haploid Variant Calling and Core Genome Alignment. GitHub. 2020. Available online: https://github.com/tseemann/snippy (accessed on 10 February 2020).

- Cingolani, P.; Platts, A.; Wang, L.L.; Coon, M.; Nguyen, T.; Wang, L.; Land, S.J.; Lu, X.; Ruden, D.M. A program for annotating and predicting the effects of single nucleotide polymorphisms, SnpEff. Fly 2012, 6, 80–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schymkowitz, J.; Borg, J.; Stricher, F.; Nys, R.; Rousseau, F.; Serrano, L. The FoldX web server: an online force field. Nucleic Acids Res. 2005, 33, W382–W388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).