1. Introduction

Long before modern medicine understood the microbiome, early physicians recognized a powerful link between the gut and the liver. As early as the 4th century, traditional Chinese medicine used fecal preparations to treat food poisoning, an approach still used today as fecal microbiota transplantation [

1]. In the early 1900s, Ivan Pavlov’s Nobel-winning experiments showed that the brain could influence digestion by triggering stomach and pancreatic secretions, a foundational discovery in brain–gut communication [

2].

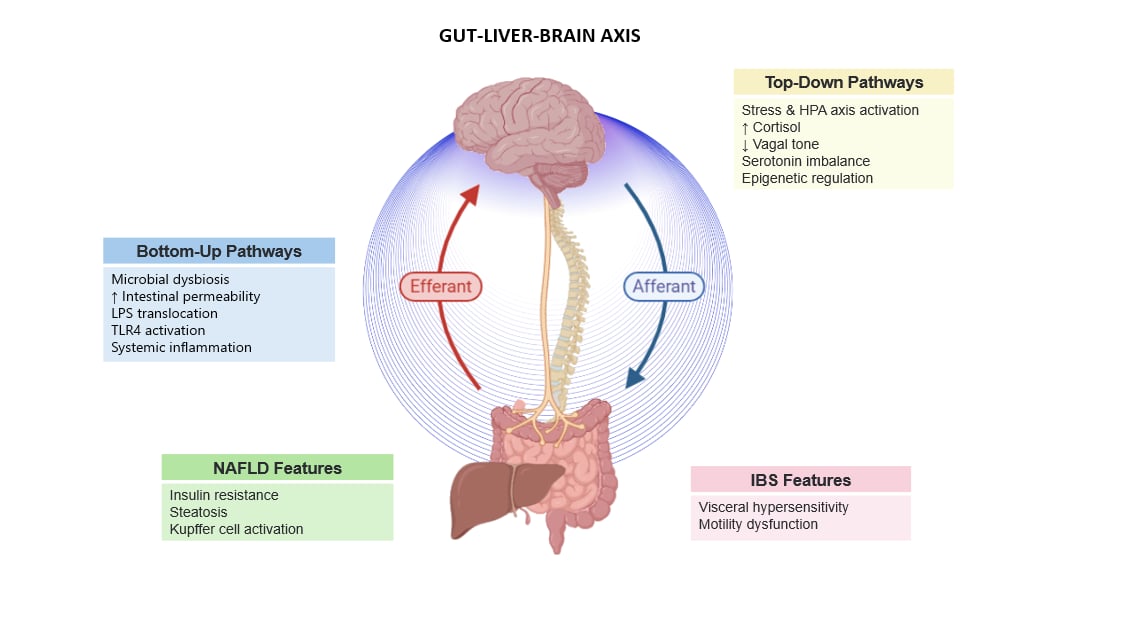

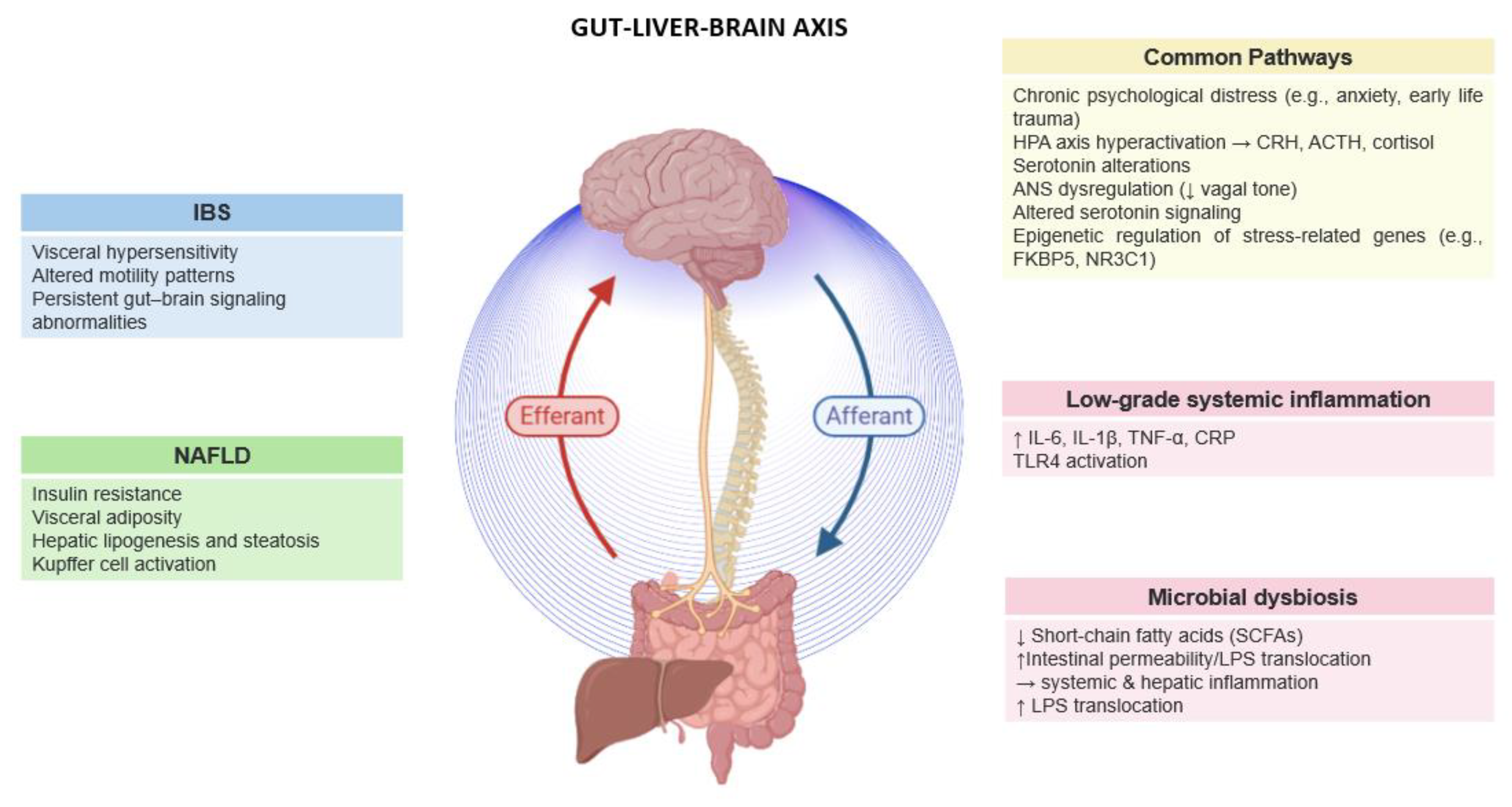

Today, a growing body of evidence converges on the concept of the gut–liver–brain axis (GLBA) as an extension of the gut-brain axis (GBA), a dynamic, tridirectional communication system involving the gastrointestinal tract, liver, and central nervous system (CNS). This axis functions through an intricate interplay of neural, immune, endocrine, and microbial pathways [

3,

4,

5,

6].

Central to its regulation are the gut microbiota and the integrity of the intestinal epithelial barrier. When barrier function is impaired, microbial metabolites such as lipopolysaccharides (LPS) can enter the portal circulation, triggering hepatic inflammation and systemic metabolic disturbances [

7]. At the neural level, the enteric nervous system forms a specialized branch of the autonomic nervous system that communicates with the CNS via the vagus nerve and spinal afferents, relaying information about luminal content, microbial composition, and immune activation [

5,

8,

9]. In response to food intake, intestinal peptides and hormones activate these afferent pathways, influencing emotional state, visceral sensitivity, and autonomic balance. These signals are centrally integrated and in turn modulate gastrointestinal and hepatic activity via parasympathetic (vagal) efferents. Importantly, top-down signals from the brain, particularly under chronic stress, can alter gut permeability, immune responses, and hepatic metabolism through the activation of the hypothalamic–pituitary–adrenal (HPA) axis and autonomic dysregulation.

This tri-directional communication is particularly relevant in Irritable Bowel Syndrome (IBS) and Non-Alcoholic Fatty Liver Disease (NAFLD), two seemingly distinct disorders that are increasingly recognized as interconnected. While affecting different organs, both conditions share a constellation of underlying mechanisms, including gut microbiota dysbiosis, intestinal barrier dysfunction, altered motility, and dysregulation of the GLBA. These disruptions promote immune activation, low-grade systemic inflammation, and neuroendocrine imbalance, all of which are central to their development and clinical overlap [

6].

IBS is a common functional gastrointestinal disorder that affects up to 23% of the global population [

10]. It is characterized by recurrent abdominal pain, changes in bowel habits, visceral hypersensitivity, psychological comorbidities, and fatigue [

10]. Although its precise etiology remains uknown, IBS is recognized as a disorder of the GBA dysfunction, where disruptions in bidirectional signaling between the CNS and the gastrointestinal tract contribute to symptom development [

6,

11]. Aberrations in this system can lead to altered motility, immune activation, neurotransmitter imbalance and increased intestinal permeability. These pathophysiological changes are further shaped by a complex interplay of genetic susceptibility, epigenetic modulation, psychological stress, and environmental influences [

10].

NAFLD, often considered the hepatic counterpart of metabolic syndrome, affects an estimated 25%–30% of the population worldwide [

12]. Characterized by abnormal triglyceride accumulation in hepatocytes without notable alcohol consumption, NAFLD is frequently associated with obesity, insulin resistance, Type 2 diabetes, and cardiovascular complications [

11,

13]. Its clinical trajectory spans from benign steatosis to more severe conditions such as steatohepatitis, liver fibrosis, and cirrhosis. Like IBS, NAFLD is now increasingly understood as a disorder not limited to a single organ, but one that emerges from the breakdown of communication along the GLBA, where metabolic, microbial, and neuroendocrine imbalances reinforce one another in a pathophysiological loop.

The GLBA has emerged as a dynamic interface where psychological distress translates into physiological dysfunction, influencing the onset and progression of both gastrointestinal and metabolic disorders. In particular, psychological distress in IBS is known to hyperactivate the HPA axis and to disrupt brain–gut communication, contributing to symptom onset and severity. This neurobiological impact is supported by recent neuroimaging studies, which reveal altered functional connectivity in IBS patients within regions implicated in emotional regulation, interoception, and sensorimotor integration [

9,

14]. Similar alterations in brain activity have also been observed in individuals with metabolic syndrome and NAFLD, suggesting shared disruptions in central autonomic and emotional processing circuits [

15].

Mounting evidence indicates that these brain connectivity changes are not merely functional correlates, but may also reflect enduring biological imprints of stress at the molecular level. Epigenetic mechanisms, including DNA methylation, histone modifications, and microRNA expression, serve as key mediators through which chronic stress reprograms gene expression [

13,

16]. Neuromodulatory systems such as serotonin, GABA, and CRH signaling are particularly susceptible to such epigenetic remodeling, linking psychological stress to both central and peripheral physiological changes.

This perspective review explores the converging mechanisms through which psychological distress influences the progression of both IBS and NAFLD, emphasizing the central role of GLBA dysfunction and neuroepigenetic reprogramming. We focus on how stress-responsive pathways, shaped by psychological, neuroendocrine, and epigenetic processes, modulate disease expression via top-down signaling. By synthesizing evidence from clinical, neuroimaging, and molecular studies, we highlight shared pathophysiological features and propose a unified framework that supports the development of innovative, multidisciplinary therapeutic strategies.

In this review, we explore how psychological distress influences the progression of IBS and NAFLD, with a focus on the neuroepigenetic regulation of stress-responsive pathways. We aim to highlight the converging evidence across behavioral, imaging, and molecular studies, shedding light on the shared pathophysiological underpinnings of these conditions and offering perspectives for future interventions.

2. Co-Prevalence of IBS and NAFLD

Epidemiological studies consistently report a significant co-prevalence of IBS and NAFLD, suggesting shared mechanistic pathways. In a large cross-sectional study from China, Ke et al. (2013) found that 23% of NAFLD patients experienced IBS symptoms, while 66% of individuals with IBS-like complaints also met criteria for NAFLD. Similarly, Hasanian et al. (2018) observed that 74% of IBS patients had NAFLD, with greater liver disease severity correlating with worse gastrointestinal symptoms. Supporting these findings, a retrospective analysis from India reported a 29% prevalence of IBS among patients with NAFLD [

17]. Likewise, Ng et al. (2023) concluded that IBS patients exhibit a threefold higher likelihood of developing NAFLD, and that up to 74% of NAFLD patients may report IBS-like symptoms [

11]. This association has been corroborated by broader systematic reviews and observational studies [

6,

11,

17].

Beyond their epidemiological overlap, IBS and NAFLD appear to share common upstream biological mechanisms that point to a unified pathophysiological framework. Lee et al. (2016) reported increased levels of liver enzymes, alanine aminotransferase (ALT) and gamma-glutamyl transferase (GGT), as well as a higher incidence of metabolic syndrome in patients with IBS [

18]. Similarly, Sadik et al. (2010) found that higher body mass index (BMI) in IBS subjects correlates with faster colonic and rectosigmoid transit as well as increased bowel frequency [

19]. A cross-sectional study from Japan demonstrated a positive association between IBS and higher triglyceride levels and prevalence of metabolic syndrome [

20]. Additionally, Gulcan et al. (2009) and Aasbrenn et al. (2017) observed higher rates of pre-diabetes and elevated LDL cholesterol in IBS patients [

21]. These molecular and metabolic links are especially prominent among individuals with insulin resistance, visceral adiposity, and chronic inflammation, hallmarks of both disorders [

6,

12].

3. Psychological Distress and the Gut–Liver–Brain Axis in IBS and NFLD

Psychological comorbidities have been shown to exacerbate the onset, severity, and progression of both IBS and NAFLD [

10,

22,

23,

24]. IBS is strongly associated with emotional dysregulation, heightened stress reactivity, anxiety, and depressive symptoms [

10,

25]. A comprehensive systematic review and meta-analysis by Zamani et al. (2019) reported that 39% of IBS patients exhibit anxiety symptoms, 23% had anxiety disorders, 29% experienced depressive symptoms, and 23.3% suffered from clinical depression [

25]. Notable, IBS symptoms can precede the onset of psychological distress, triggering mood disorders in nearly half of patients, while pre-existing anxiety and depression triple the risk of developing IBS [

10,

25].

In NAFLD, psychological distress similarly contributes to disease onset and progression through both neuroendocrine and metabolic pathways. Clinical and epidemiological studies showed that elevated stress correlates with more severe hepatic histopathology, including steatosis, lobular inflammation, and fibrosis [

22,

26]. In a large cross-sectional study involving over 170,000 Korean adults, Kang et al. (2020) demonstrated a significant independent association between high perceived stress levels and NAFLD risk, even after adjusting for metabolic and lifestyle confounders [

27].

Both acute and chronic psychological distress result in the hyperactivation of HPA axis, resulting in prolonged elevations of cortisol and norepinephrine. While this HPA axis hyperactivation constitutes the core stress response, it is accompanied by broader physiological disturbances, including autonomic nervous system dysregulation, vagal tone suppression, neuroimmune signaling disruption, neurotransmitter imbalance, and gut microbial dysbiosis [

11,

13].

These alterations collectively disrupt the GLBA, depending on an individual’s genetic, epigenetic, microbial, and metabolic makeup, this dysregulation may manifest primarily as gastrointestinal symptoms typical of IBS or as hepatic disturbances characteristic of NAFLD. In IBS, the cascade contributes to gut dysfunction, visceral hypersensitivity, altered motility, and mucosal inflammation, while in NAFLD, it promotes insulin resistance, hepatic lipid accumulation, steatosis, and inflammatory signaling.

Crucially, these neuroendocrine stress responses are tightly interwoven with the gut microbiota, whose composition and function are highly sensitive to psychological and hormonal shifts. Thus, psychological distress acts not only as a trigger of HPA axis dysfunction but also as a driver of microbial imbalance, perpetuating a pathogenic feedback loop that links emotional, gastrointestinal, and metabolic disturbances across both IBS and NAFLD [

12,

13].

4. Critical Mechanisms Linking Psychological Distress to IBS and NAFLD

Psychological distress translates into biological dysfunction across multiple levels of the GLΒA, initiating a cascade of events that impair intestinal smooth muscle function in IBS and drive hepatic lipid accumulation in NAFLD.

4.1. Microbial Alterations in IBS and NAFLD

At the microbial level, gut dysbiosis acts both as a cause and a consequence of the pathophysiology observed in IBS and NAFLD. Microbial communities are central to GLBA communication, producing approximately 90% of the body’s neurotransmitters [

28]. This microbial system generates a diverse array of neuroactive compounds, such as short-chain fatty acids (SCFAs), tryptophan metabolites, and gamma-aminobutyric acid, that are essential for maintaining intestinal homeostasis, epithelial barrier integrity, and CNS regulation [

10,

29,

30,

31,

32].

Disruption of the gut microbial ecosystem in both IBS and NAFLD is associated with a significant decline in these beneficial metabolites, leading to compromised barrier integrity and increased permeability [

6]. This allows the translocation of pro-inflammatory molecules and bacterial components from the intestinal lumen into systemic circulation. Psychological distress exacerbates these changes via HPA axis activation and cortisol release, which can further disrupt gut microbial composition and amplify neuroimmune signaling [

6,

11].

Specific bacterial taxa and their metabolites also directly influence host neural activity and behavior by modulating immune pathways and interacting with neural circuits. For example,

Bifidobacterium longum NCC3001 has been shown to upregulate brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF), promote neuroplasticity in the enteric nervous system, and alleviate mood disturbances in IBS. In terms of composition, IBS is frequently characterized by reduced alpha diversity, a relative abundance of potentially pro-inflammatory species such as

Ruminococcus gnavus,

Streptococcus spp., and other Firmicutes, and a depletion of anti-inflammatory genera like

Faecalibacterium prausnitzii,

Lactobacillus, and

Bifidobacterium [

11,

18,

32,

33,

34,

35,

36,

37,

38,

39,

40,

41,

42].

NAFLD exhibits a similar dysbiotic pattern, with increased representation of

Proteobacteria, particularly

Enterobacteriaceae (e.g.,

Escherichia coli) and

Clostridium spp., alongside reductions in

Faecalibacterium,

Bifidobacterium,

Prevotella, and

Roseburia [

11,

18,

31,

32,

33,

34,

35,

36,

37,

38,

39,

40,

43,

44]. These shifts are associated with impaired bile acid metabolism, reduced choline availability, and increased gut permeability, all of which favor the translocation of lipopolysaccharide (LPS) into the portal vein. The hepatic immune response elicited by this translocation promotes liver steatosis, inflammation, and fibrosis.

Table 1.

Summary of microbial features associated with Irritable Bowel Syndrome (IBS) and Non-Alcoholic Fatty Liver Disease (NAFLD). The table highlights overlapping and condition-specific microbial alterations. Arrows indicate directional changes in abundance. SCFAs = short-chain fatty acids; LPS = lipopolysaccharide; TLR4 = Toll-like receptor 4. “Shared?” indicates whether the microbial feature is common to both disorders.

Table 1.

Summary of microbial features associated with Irritable Bowel Syndrome (IBS) and Non-Alcoholic Fatty Liver Disease (NAFLD). The table highlights overlapping and condition-specific microbial alterations. Arrows indicate directional changes in abundance. SCFAs = short-chain fatty acids; LPS = lipopolysaccharide; TLR4 = Toll-like receptor 4. “Shared?” indicates whether the microbial feature is common to both disorders.

| Microbial features associated with IBS and NAFLD |

|---|

| Microbial Feature |

Regulation and function in IBS and NAFLD |

| ↓Faecalibacterium prausnitzii

|

Anti-inflammatory function in IBS; reduction leads to decreased SCFA levels and increased visceral pain. In NAFLD, reduced abundance is associated with inflammation. Shared feature [11,34,35,36] |

| ↓ Bifidobacterium spp. |

Reduced SCFA production and weakened immune modulation in IBS; decreased levels in NAFLD (especially fibrosis); associated with reduced immune resilience and SCFA loss. Shared microbial pattern. [11,37,38,39] |

| ↓ Lactobacillus spp. |

Impaired gut barrier function and altered motility in IBS and NAFLD. Less consistently reported in NAFLD. Partial shared feature. [18,32,40] |

| ↑ Ruminococcus gnavus |

In IBS: mucin degradation and production of pro-inflammatory metabolites. Not clearly implicated in NAFLD. Not a shared feature [11,41] |

| ↑ Streptococcus spp. |

Linked to bloating and altered fermentation in IBS. Not a key feature in NAFLD. Not shared. [33,34,42] |

| ↑ Proteobacteria / E. coli |

Mild increase in IBS; linked to mucosal inflammation. Strongly associated with endotoxemia and disease progression in NAFLD. Shared feature. [34,37,43] |

| ↑ Clostridium spp |

Not prominent in IBS. Elevated in NAFLD, contributing to bile acid dysregulation. Not shared. [30,31,33] |

| ↓ SCFAs (e.g., butyrate) |

In IBS: reduction due to loss of SCFA-producing taxa (e.g., F. prausnitzii, Bifidobacterium). Same pattern seen in NAFLD; leads to impaired gut-liver anti-inflammatory signaling. Shared feature. [37,44] |

| ↑ LPS translocation |

In IBS: due to Gram-negative overgrowth (e.g., Proteobacteria). In NAFLD: drives hepatic inflammation via TLR4 activation. Shared feature. [32,45] |

4.2. Stress-Induced HPA Axis Dysregulation

Psychological and physical stressors initiate a cascade within the HPA, leading to the release of corticotropin-releasing hormone (CRH), adrenocorticotropic hormone (ACTH), and ultimately cortisol (

Figure 1). Chronic activation of this system results in sustained cortisol exposure, which disrupts immune function, metabolic regulation, and gut–brain signaling [

13]. In IBS, patients often show heightened HPA responsiveness and elevated cortisol levels, particularly in the presence of stress sensitivity or anxiety [

23,

29,

46,

47]. CRH and cortisol impair gut motility, increase intestinal permeability, and enhance mucosal inflammation and visceral hypersensitivity, increasing susceptibility to inflammation and altered sensory perception [

23,

29,

46,

47]. The gut microbiota amplifies these effects by modulating neuroendocrine signaling pathways through the production of short-chain fatty acids and neuroactive metabolites [

11].

In NAFLD, cortisol dysregulation contributes to the metabolic and inflammatory milieu underlying disease progression. Cortisol excess promotes insulin resistance, hepatic fat accumulation, and immune activation, while dysbiosis facilitates LPS translocation across a compromised intestinal barrier, triggering Kupffer cell activation and hepatic injury [

11,

13]. Both IBS and NAFLD exhibit self-reinforcing feedback loops within GLBA. Stress-induced microbial dysbiosis amplifies HPA axis hyperactivity, which in turn exacerbates dysbiosis and systemic inflammation, thereby sustaining the pathophysiology of both disorders [

11,

13].

Importantly, while the gut microbiota modulates HPA axis reactivity, the reverse is also true, chronic HPA axis hyperactivity feeds back on the gut ecosystem, reducing microbial diversity and selectively depleting beneficial genera such as

Lactobacillus and

Bifidobacterium, while enriching pro-inflammatory taxa such as

Clostridium difficile and

Streptococcus spp. [

48,

49].

4.3. Neurotransmitter and Neuromodulator Imbalances

Hyperactivation of the HPA axis leads to elevated levels of corticotropin-releasing hormone (CRH), adrenocorticotropic hormone (ACTH), and cortisol (

Figure 1). This persistent neuroendocrine activity alters key neurotransmitter systems, including serotonin (5-HT), dopamine, gamma-aminobutyric acid (GABA), norepinephrine (NE), and histamine. In IBS, stress-induced HPA hyperactivity is associated with altered 5-HT signaling; increased serotonin and 5-HT₃ receptor activity contribute to diarrhea and visceral pain, while reduced levels are linked to constipation [

10,

50,

51]. Altered GABA, norepinephrine, histamine, and dopamine levels are also linked to heightened pain perception and abnormal motility [

10,

51].

In NAFLD, though less extensively studied, similar neuromodulator disruptions have been observed [

50,

52]. Chronic HPA axis activation sustains cortisol increase, promoting insulin resistance, hepatic steatosis, and inflammation [

6,

13]. Stress also affects serotonergic signaling and gut hormone release, including GLP-1 and PYY, influencing hepatic metabolism and mood regulation [

13,

53]. Microbiota-derived deficits in SCFAs and secondary bile acids impair serotonin synthesis and vagal communication, further disturbing neuroimmune and hepatic pathways [

13,

53]. Stress intensifies these alterations by increasing pro-inflammatory cytokines, exacerbating gut permeability, neuroinflammation, and visceral sensitivity, thus reinforcing a feed-forward loop with microbial dysbiosis [

51].

4.4. Low-Grade Inflammation

Low-grade inflammation is a key driver of disease progression in both IBS and NAFLD (

Figure 1). Chronic stress induces a series of immune changes that contribute to low-grade, systemic inflammation in both IBS and NAFLD via the LGBA (

Figure 1). Elevated pro-inflammatory cytokines, including IL-6, TNF-α, IL-1β, and IL-8, are common to both disorders, originating from the colonic mucosa in IBS and the liver in NAFLD, and circulate systemically to promote neuroinflammation and immune activation across organs [

6,

11,

53]. Glucocorticoid resistance, caused by chronic HPA axis stimulation, further amplifies these responses by weakening cortisol’s anti-inflammatory effects [

6,

11]. Furthermore, in both conditions, increased intestinal permeability allows microbial products such as LPS to enter the circulation, activating TLR4 in gut and liver tissue and triggering NF-κB-mediated cytokine release [

11]. The result is a self-sustaining inflammatory loop, reinforced by elevated IL-6 and CRP, linking gut, liver, and brain dysfunction under chronic stress.

4.5. Autonomic Nervous System (ANS) Dysregulation

Both IBS and NAFLD are characterized by autonomic imbalance, with a shift toward sympathetic dominance and reduced parasympathetic (vagal) activity (

Figure 1)[

6]. This dysregulation contributes to altered motility, inflammation, and metabolic dysfunction across the GLBA [

11,

53]. Stress-induced ANS changes also impair neuroimmune communication and may exacerbate visceral hypersensitivity in IBS and hepatic inflammation in NAFLD [

11,

53,

54]. Reduced vagal tone impairs the cholinergic anti-inflammatory pathway, weakening the body’s ability to suppress cytokine production and maintain gut–liver immune homeostasis. In both IBS and NAFLD, vagal dysfunction under stress contributes to systemic inflammation and reinforces microbiota–brain dysregulation.

4.6. Personality Traits

In both IBS and NAFLD, high neuroticism is associated with increased stress sensitivity, maladaptive coping, and heightened physiological reactivity [

55,

56]. These traits contribute to low-grade inflammation, behavioral dysregulation (e.g., poor diet, inactivity), and worse clinical outcomes [

22,

24,

55].

4.7. Bidirectional Feedback Loops

Personality traits, psychological distress, and maladaptive cognitive styles, such as rumination and threat anticipation, contribute to HPA axis hyperactivation in both IBS and NAFLD, by disrupting the GLBA (

Figure 1). Stress-related cortisol elevation and autonomic imbalance alter the microbiota, impair barrier function, and weaken immune control [

6]. This promotes microbial translocation and inflammation, which then feed back to the brain, reinforcing emotional dysregulation and sustaining a vicious cycle of GLBA dysfunction.

5. Neuroimaging and Central Processing

Neuroimaging findings confirm and extend the pathophysiological and molecular alterations found in both IBS and NAFLD, particularly those involving stress responsiveness, emotional regulation, and GLBA communication [

57,

58,

59]. Functional MRI (fMRI) studies in both disorders consistently show altered activity and connectivity in brain regions such as the amygdala, insula, prefrontal cortex, and hippocampus; areas central to interoception, emotion processing, and cognitive control [

57,

58,

60,

61]. In IBS and NAFLD alike, amygdala hyperactivation reflects heightened sensitivity to stress and visceral cues, while insula dysfunction is linked to impaired emotional awareness, symptom severity and visceral pain perception [

9]. Alterations in the prefrontal cortex and hippocampus, especially in patients with anxiety or depression, suggest compromised executive regulation and stress adaptation [

62].

Importantly, both disorders also exhibit disrupted connectivity in the Default Mode Network (DMN), a brain network associated with internally directed thought, sensory monitoring, and pain modulation. Studies on IBS and NAFLD showed reduced DMN coherence that may reflect the impaired downregulation of visceral and emotional signals, contributing to hypervigilance and maladaptive cognitive-emotional processing [

63,

64]. These brain changes are further modulated by psychological traits and stress history, including anxiety, catastrophizing, and early life trauma [

57]. Concurrently, alterations in gut microbiota composition and systemic inflammation have been shown to influence large-scale brain networks, emphasizing the bidirectional nature of the GLBA [

61,

65]. Notably, probiotic interventions have been shown to reduce activity in the amygdala and insula, and to normalize connectivity in key networks such as the salience network and DMN [

9].

6. Epigenetic Mechanisms in Stress Response

Epigenetic mechanisms are considered a crucial link between psychological stress and the persistent alterations observed in the GLBA. Both psychological stress and early-life adversity can induce stable epigenetic changes, such as DNA methylation, histone modifications, and altered microRNA expression, in genes regulating stress responses, neurotransmission, inflammation, and intestinal barrier integrity (

Table 2)[

50,

66,

67,

68]. Key epigenetically modified targets include the glucocorticoid receptor (NR3C1), corticotropin-releasing factor (CRF), serotonin transporter (SERT) (

Table 2) [

13,

16,

50,

67,

68,

69]. These genes are critical for maintaining homeostasis across the GLBA and are increasingly shown to respond to stress signals at the molecular level [

13,

16].

6.1. DNA Methylation Patterns

Chronic stress triggers convergent methylation patterns across IBS and NAFLD, reinforcing dysfunction along the GLBA. DNA methylation, especially at promoter regions and CpG islands, represses gene transcription and plays a key role in shaping long-term disease trajectories. Among the most consistently affected genes, FKBP5, which expresses a regulator of glucocorticoid receptor sensitivity, is hypomethylated under stress, leading to exaggerated HPA axis responses and impaired cortisol feedback (

Table 2) [

13,

67,

68]. Likewise, NR3C1, which encodes the glucocorticoid receptor itself, is frequently hypermethylated, particularly in early-life stress models, reducing receptor expression and further dysregulating HPA axis control [

50,

70].

Methylation of CLDN1, which encodes the tight junction protein claudin-1, weakens epithelial barrier integrity, contributing to increased gut permeability in IBS and metabolic endotoxemia in NAFLD [

3,

16,

46,

67,

70,

71]. The TRPV1 gene, which encodes a pain-sensing ion channel, also exhibits altered methylation under stress, amplifying visceral hypersensitivity in IBS and inflammatory signaling in NAFLD [

13,

16,

46,

67,

70,

71]. Furthermore, BDNF, which is crucial for neuroplasticity and emotional regulation, shows stress-induced methylation changes that impair neuronal adaptability and immune-neuroendocrine balance along the GLBA [

13,

16,

67,

71].

6.2. Histone Modifications

Histone modifications further contribute to transcriptional reprogramming across the GLBA. Stress-altered microbial metabolites, especially short-chain fatty acids (SCFAs) like butyrate, act as histone deacetylase (HDAC) inhibitors, promoting or repressing gene expression via changes in chromatin accessibility. TRPV1 gene undergoes increased histone acetylation, enhancing its expression and contributing to visceral pain in IBS and hepatic inflammation in NAFLD (

Table 2) [

3,

16,

46,

67,

70,

71]. Similarly, CRF and NR3C1, key regulators of the HPA axis, are subject to histone acetylation and methylation that modulate stress responses and downstream immune activity [

13,

16,

47,

67,

71].

Tight junction proteins such as Claudin-1, Occludin, and ZO-1 also undergo histone modifications that affect barrier permeability [

13,

16,

67,

71]. Under homeostatic conditions, SCFA-driven acetylation preserves barrier integrity. However, stress and dysbiosis reduce SCFA production, leading to histone deacetylation, decreased protective gene expression, and increased epithelial and hepatic permeability [

13,

16].

6.3. MicroRNA Regulation

MicroRNAs (miRNAs) serve as fine-tuning regulators of gene expression and are increasingly implicated in GLBA disruption in both IBS and NAFLD. These small non-coding RNAs bind to complementary sequences on target mRNAs, leading to translational repression or degradation. In the context of GLBA dysfunction, miRNAs respond to psychological stress and microbial cues, thereby acting as dynamic mediators between environmental stimuli and long-term physiological outcomes. Their dysregulation sustains neuroimmune imbalance, epithelial permeability, and chronic inflammation, reinforcing the pathophysiological overlap between IBS and NAFLD.

MiR-122 is highly expressed in the liver and regulates lipid metabolism and inflammation [

13,

67]. Its downregulation is linked to hepatic steatosis in NAFLD, while altered expression in IBS may modulate gut immune activity. In addition, miR-29a regulates intestinal permeability and fibrogenic signaling and it is found to be elevated in both disorders, contributing to mucosal inflammation in IBS and hepatic stellate cell activation in NAFLD [

13,

16,

67,

71].

In both disorders, miR-34a upregulation has been shown to promote inflammatory signaling and insulin resistance [

13]. Similarly, miR-155, a stress-responsive and pro-inflammatory miRNA, influences cytokine expression in the gut and liver [

13,

47,

71]. Furthemore, there an overexpression of miR-21 has also been found, which is associated with tissue remodeling and fibrosis and is know to induce chronic inflammation and impaired repair mechanisms [

13,

16,

67,

71]. These miRNAs, often stress-sensitive and microbiota-responsive, reinforce maladaptive signaling cascades across GLBA organs. They are also emerging as potential biomarkers and therapeutic targets for both IBS and NAFLD.

6.4. Epigenetic Imprint of Stress and Therapeutic Implications

These epigenetic signatures act together as molecular imprints of chronic stress, reinforcing a cycle of low-grade inflammation, and epithelial and hepatic dysfunction, anchoring long-term symptomatology across both disorders. Reduced vagal tone and HPA axis hyperactivation exacerbate these epigenetic shifts, reinforcing barrier dysfunction and neuroinflammation [

11,

13,

16]. While tissue-specific evidence in humans remains limited, preclinical studies confirm that sustained stress triggers stable epigenetic reprogramming across gut and brain circuits in IBS, and in liver and gut epithelial cells in NAFLD [

13,

16,

67]. These changes collectively fuel a feedback loop of dysregulation within the GLBA, positioning epigenetic control as a key shared mechanism driving the progression of both disorders.

In both IBS and NAFLD, persistent epigenetic changes may sustain aberrant gene expression patterns that perpetuate inflammation and metabolic dysfunction, even after the initial stressor has subsided. This chronicity highlights a compelling paradox: while these epigenetic modifications are long-lasting, they are not permanent. Unlike genetic mutations, epigenetic marks, such as DNA methylation and histone modifications, do not alter the underlying DNA sequence and are, in principle, reversible.

Environmental changes (e.g., microbiota modulation, diet, or stress reduction), pharmacological agents (such as HDAC inhibitors), and psychological therapies like Cognitive-Behavioral Therapy (CBT) and Mentalization-Based Therapy (MBT) have all shown potential to reverse stress-induced epigenetic alterations. Clinical and experimental studies reveal that CBT can modify methylation of key stress-regulation genes: increasing methylation of

SLC6A4 (serotonin transporter) and decreasing methylation of

FKBP5 (a glucocorticoid receptor co-chaperone), thereby improving HPA axis regulation and emotional resilience [

72,

73,

74]. Likewise, psychotherapeutic engagement has been shown to normalize

BDNF methylation, a gene critical for neuroplasticity and mood regulation [

75].

Moreover, growing evidence suggests that certain epigenetic marks can escape erasure during gamete formation and early embryonic development, raising the possibility of transgenerational inheritance. Stress-related methylation changes, particularly in

FKBP5 and

NR3C1, can be transmitted to offspring when exposures occur during sensitive developmental periods, such as pregnancy or early childhood [

13,

76]. As a result, unresolved stress may “prime” future generations for increased vulnerability to immune dysregulation, emotional disorders, or metabolic conditions, even in the absence of direct exposure.

Psychotherapeutic interventions, therefore, may hold intergenerational value, by normalizing stress-related epigenetic patterns in parents, such therapies could potentially reduce the transmission of maladaptive marks to offspring or mitigate their effects. This dual potential, both therapeutic and preventive, highlights the plasticity of epigenetic regulation and offers a compelling avenue for addressing the chronic and systemic nature of both IBS and NAFLD.

7. Biomarkers of Gut–Liver–Brain Axis Dysfunction

In parallel with epigenetic modifications, a range of biomarkers has emerged as promising indicators of gut–liver–brain axis (GLBA) dysfunction in both IBS and NAFLD. Inflammatory cytokines such as IL-6, TNF-α, and C-reactive protein (CRP) consistently signal the presence of chronic low-grade systemic inflammation in both conditions [

13]. Lipopolysaccharide (LPS), a hallmark of gut barrier disruption and microbial translocation, is frequently elevated, contributing to hepatic stress and neuroimmune activation [

12,

49].

Neuroendocrine mediators such as serotonin, glucagon-like peptide-1 (GLP-1), and fibroblast growth factor 19 (FGF19), along with microbial-derived metabolites like short-chain fatty acids (SCFAs) and trimethylamine-N-oxide (TMAO), further reflect the complex interplay between microbial, metabolic, and neurohormonal dysregulation [

6,

47,

50]. Together, these biomarkers offer a valuable translational window into GLBA disruption and hold potential for monitoring disease progression and treatment response.

To further elucidate the molecular landscape of these disorders, epigenome-wide association studies (EWAS) are currently underway to identify differential DNA methylation patterns in genes regulating inflammation, metabolism, and neurotransmission [

76]. These investigations aim to advance predictive models for disease trajectory and therapeutic responsiveness in both IBS and NAFLD.

8. Future Therapies

Recent advances in the understanding of the GLBA have opened new therapeutic avenues aimed at restoring systemic homeostasis and halting disease progression in disorders such as IBS and NAFLD. One promising strategy is the modulation of epigenetic mechanisms, including DNA methylation, histone modifications, and microRNA expression. Although epigenetic markers are relatively stable, they are reversible, making them ideal targets for therapeutic intervention. Preclinical studies have demonstrated that pharmacological agents, such as HDAC inhibitors and DNA methylation modulators, can counteract stress-induced gene expression changes [

16]. Moreover, cutting-edge approaches like CRISPR/dCas9-based epigenetic editing tools hold potential for site-specific correction of aberrant epigenetic signatures [

13,

83].

Lifestyle interventions have also shown significant promise. For example, exercise has been found to restore m6A RNA methylation in the medial prefrontal cortex, producing anxiolytic effects through the GLBA [

6,

84]. This effect relies on hepatic synthesis of methyl donors, highlighting the unexpected but pivotal role of liver function in regulating CNS activity. Likewise, dietary strategies, particularly the use of probiotics, have demonstrated efficacy in rebalancing the gut microbiota and reducing systemic inflammation [

11]. Some of these interventions, including probiotic formulations based on

Bifidobacterium and

Lactobacillus, are currently being evaluated in phase III clinical trials [

13].

From a psychological and neuroendocrine perspective, CBT and Mindfulness-Based Stress Reduction (MBSR) have emerged as potent non-pharmacological treatments [

72,

73,

74]. These interventions reduce HPA axis overactivation and modulate methylation levels of key stress-responsive genes such as

FKBP5 and

BDNF [

13]. Beyond symptom relief, such therapies may also mitigate the transgenerational transmission of stress-induced epigenetic alterations, offering long-term preventive benefits.

Looking forward, a multi-modal, integrative approach, one that combines psychotherapeutic, microbial, and epigenetic strategies, is necessary to address the complex, multifactorial nature of IBS and NAFLD. Future clinical research will benefit from stratified trial designs guided by biomarker profiling (e.g., LPS, SCFAs, cytokines, miRNAs) to enhance personalization and efficacy.

9. Conclusions

In this review, we have explored how psychological stress, through its impact on the gut–liver–brain axis, shapes the pathophysiology of both IBS and NAFLD via interconnected neuroimmune, microbial, and epigenetic pathways.

Psychological distress, through the sustained activation of the HPA axis and suppression of vagal tone, triggers a cascade of physiological alterations along the GLBA. This cascade involves neuroimmune dysregulation, microbial imbalance, and inflammation, which together contribute to a self-reinforcing loop of dysfunction. Depending on genetic, epigenetic, and metabolic predispositions, this dysregulation may manifest as IBS, characterized by gut sensitivity and motility issues, or as NAFLD, marked by hepatic steatosis and insulin resistance. The convergence of these mechanisms highlights the GLBA as a common pathway through which psychological processes influence visceral and metabolic function. Epigenetic mechanisms, such as DNA methylation, histone modifications, and microRNA regulation, mediate the biological imprint of stress and contribute to the chronic course of both conditions.

Conceptualizing the GLBA as a dynamic interface between psychological and somatic processes invites a rethinking of therapeutic strategies. Integrated interventions, combining psychotherapeutic, microbiota-directed, and epigenetic approaches, offer new opportunities to interrupt maladaptive feedback loops and restore physiological balance. Future studies should prioritize multimodal, individualized frameworks capable of capturing the complexity of GLBA dysfunction and informing tailored interventions for disorders at the intersection of brain, gut, and liver.

References

- Zhang, F. Luo, W., Shi, Y., Fan, Z., Ji, G. Should we standardize the 1,700-year-old fecal microbiota transplantation? American Journal of Gastroenterology 2012, 107, 1755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pavlov, I. P. Nobel Lecture: Physiology of digestion. NobelPrize.org. 1904. Available online: https://www.nobelprize.org/prizes/medicine/1904/pavlov/lecture/ (accessed on day month year).

- Ansari F, Neshat M, Pourjafar H, Jafari SM, Samakkhah SA, Mirzakhani E. The role of probiotics and prebiotics in modulating of the gut-brain axis. Front Nutr. 2023, 10, 1173660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Sundman M, H. , Chen, N. K., Subbian, V., & Chou, Y. H. The bidirectional gut-brain-microbiota axis as a potential nexus between traumatic brain injury, inflammation, and disease. Brain, behavior, and immunity 2017, 66, 31–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu X, Han Y, Jing D, Liu R, Jin K, Yi W. Microbiota-gut–brain axis and the central nervous system. Oncotarget. 2017, 8, 53829–53838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, S.; et al. Non-alcoholic fatty liver is associated with increased risk of IBS: a prospective cohort study. BMC Medicine 2022, 20, 262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ralli, T. , Saifi, Z., Tyagi, N., Vidyadhari, A., Aeri, V., & Kohli, K. Deciphering the role of gut metabolites in non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. Critical reviews in microbiology 2022, 49, 815–833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hyland NP, Cryan JF. Microbe-host interactions: influence of the gut microbiota on the enteric nervous system. Dev Biol Enter Nerv Syst. 2016, 417, 182–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crocetta A, Liloia D, Costa T, Duca S, Cauda F, Manuello J. From gut to brain: unveiling probiotic effects through a neuroimaging perspective—A systematic review of randomized controlled trials. Front Nutr. 2024, 11, 1446854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koumbi L, Giannelou M-A, Castelli L. The gut–brain axis in irritable bowel syndrome: neuroendocrine and epigenetic pathways. Academia Biology. 2025, 3, 74–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ng, J. J. J. , Loo, W. M., & Siah, K. T. H. Associations between irritable bowel syndrome and non-alcoholic fatty liver disease: A systematic review. World Journal of Hepatology 2023, 15, 925–938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhattacharjee, B.; et al. Study of interrelationship between irritable bowel syndrome and non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. Acta Scientific Gastrointestinal Disorders 2023, 6, 8–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, M.; et al. Gut–liver–brain axis in diseases: implications for therapeutic interventions. Signal Transduction and Targeted Therapy 2023, 8, 443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Weaver KR, Sherwin LB, Walitt B, Melkus GD, Henderson WA. Neuroimaging the brain-gut axis in patients with irritable bowel syndrome. World J Gastrointest Pharmacol Ther. 2016, 7, 320–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weinstein, G. , O’Donnell, A., Frenzel, S., Xiao, T., Yaqub, A., Yilmaz, P., de Knegt, R. J., Maestre, G. E., Melo van Lent, D., & Launer, L. J. Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease, liver fibrosis, and structural brain imaging: The Cross-Cohort Collaboration. Hepatology 2022, 76, 1425–1436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, Y.; et al. Gut microbiota induced epigenetic modifications in the non-alcoholic fatty liver disease pathogenesis. Engineering in Life Sciences 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Purssell, H. , Whorwell, P. J., Athwal, V. S., & Vasant, D. H. Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease in irritable bowel syndrome: More than a coincidence? World Journal of Hepatology 2021, 13, 1816–1827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee SH, Kim KN, Kim KM, Joo NS. Irritable Bowel Syndrome May Be Associated with Elevated Alanine Aminotransferase and Metabolic

Syndrome. Yonsei Med J 2016, 57, 146–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sadik R, Björnsson E, Simrén M. The relationship between symptoms, body mass index, gastrointestinal transit and stool frequency in patients

with irritable bowel syndrome. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol 2010, 22, 102–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guo Y, Niu K, Momma H, Kobayashi Y, Chujo M, Otomo A, Fukudo S, Nagatomi R. Irritable bowel syndrome is positively related to metabolic syndrome: a population-based cross-sectional study. PLoS One 2014, 9, e112289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aasbrenn M, Høgestøl I, Eribe I, Kristinsson J, Lydersen S, Mala T, Farup PG. Prevalence and predictors of irritable bowel syndrome in patients with morbid obesity: a cross-sectional study. BMC Obes 2017, 4, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Younossi, Z. , Tacke, F., Arrese, M., et al. Global perspectives on nonalcoholic fatty liver disease and nonalcoholic steatohepatitis. Hepatology 2019, 69, 2672–2682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hellström, P. M. , & Benno, P. The Rome IV: Irritable bowel syndrome—a functional disorder. Best Practice & Research Clinical Gastroenterology 2019, 40–41, 101634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goodoory, V.C.; Mikocka-Walus, A.; Yiannakou, Y.; Houghton, L.A.; Black, C.J.; Ford, A.C. Impact of Psychological Comorbidity on the Prognosis of Irritable Bowel Syndrome. Am. J. Gastroenterol. 2021, 116, 1485–1494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zamani M, Alizadeh-Tabari S, Zamani V. Systematic review with meta-analysis: the prevalence of anxiety and depression in patients with irritable bowel syndrome. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2019, 50, 132–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bellentani, S. The epidemiology of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. Liver International 2017, 37 (Suppl. 1), 81–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kang, D. , Zhao, D., Ryu, S., Guallar, E., Cho, J., Shin, H., Chang, Y., & Sung, E. Perceived stress and non-alcoholic fatty liver disease in apparently healthy men and women. Scientific Reports 2020, 10, Article 4260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strandwitz, P. Neurotransmitter modulation by the gut microbiota. Brain Res. 2018, 1693 Pt B, 128–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fukudo S, Nomura T, Hongo M. Stress and visceral pain: focusing on irritable bowel syndrome. Pain. 2013, 154 (Suppl. 1), S63–70. [CrossRef]

- Bassotti G, Villanacci V. Irritable bowel syndrome and the gut microbiota: is there a link? World J Gastroenterol. 2014, 20, 10547–10557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Kolodziejczyk, A. A. , Zheng, D., Shibolet, O., & Elinav, E. The role of the microbiome in NAFLD and NASH. Nature Reviews Gastroenterology & Hepatology 2019, 16, 745–757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dlugosz A, Winckler B, Lundin E, Zakikhany K, Sandström G, Ye W, Engstrand L, Lindberg G, et al. No difference in small bowel microbiota between patients with irritable bowel syndrome and healthy controls. Sci Rep. 2015, 5, 8508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boursier J, Mueller O, Barret M, Machado M, Fizanne L, Araujo-Perez F, Guy CD, Seed PC, Rawls JF, David LA, Hunault G, Oberti F, Calès P, Diehl AM. The severity of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease is associated with gut dysbiosis and shift in the metabolic function of the gut microbiota. Hepatology. 2016, 63, 764–775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhuang X, Xiong L, Li L, Li M, Chen M. Alterations of gut microbiota in patients with irritable bowel syndrome: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2017, 32, 28–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shin J-H, Lee Y, Song EJ, Lee D, Jang S-Y, Byeon HR, Hong M-G, Lee S-N, Kim H-J, Seo J-G, et al. Faecalibacterium prausnitzii prevents hepatic damage in a mouse model of NASH induced by a high-fructose high-fat diet. Frontiers in Microbiology. 2023, 14, 1123547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miquel S, Martín R, Lashermes A, Gillet M, Meleine M, Gelot A, Eschalier A, Ardid D, Bermúdez-Humarán LG, Sokol H, Thomas M, Theodorou V, Langella P, Carvalho FA. Anti-nociceptive effect of Faecalibacterium prausnitzii in non-inflammatory IBS-like models. Scientific Reports. 2016, 6, 19399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leung C, Rivera L, Furness JB, Angus PW. The role of the gut microbiota in NAFLD. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2016, 13, 412–425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

-

O’Mahony L, McCarthy J, Kelly P, Hurley G, Luo F, Chen K, et al. Lactobacillus and Bifidobacterium in irritable bowel syndrome: Symptom responses and relationship to cytokine profiles. Gastroenterology. 2005, 128, 541–551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoon SJ, Yu JS, Min BH, Gupta H, Won SM, Park HJ, et al. Bifidobacterium-derived short-chain fatty acids and indole compounds attenuate nonalcoholic fatty liver disease by modulating gut-liver axis. Gut Microbes. 2023, 15, 2191153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Han, X. , Lee, A., Huang, S., Gao, J., Spence, J. R., & Owyang, C. Lactobacillus rhamnosus GG prevents epithelial barrier dysfunction induced by interferon-gamma and fecal supernatants from irritable bowel syndrome patients in human intestinal enteroids and colonoids. Gut Microbes 2019, 10, 59–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhai L, Huang C, Ning Z, Zhang Y, Zhuang M, Yang W, et al. Ruminococcus gnavus plays a pathogenic role in diarrhea-predominant irritable bowel syndrome by increasing serotonin biosynthesis. Cell Host Microbe. 2023, 31, 33–44.e5. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

-

Xia H, et al. Intestinal microbiome and NAFLD: molecular insights and therapeutic perspectives. J Gastroenterol. 2020, 55, 142–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petersen, AM. Gastrointestinal dysbiosis and Escherichia coli pathobionts in inflammatory bowel diseases. APMIS 2022, 130 (Suppl. 144), 1–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

-

Gargari G, Mantegazza G, Taverniti V, Gardana C, Valenza A, Rossignoli F, Barbaro MR, Marasco G, Cremon C, Barbara G, Guglielmetti S. Fecal short-chain fatty acids in non-constipated irritable bowel syndrome: a potential clinically relevant stratification factor based on catabotyping analysis. Gut Microbes. 2023, 15, 2274128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prospero, L. , Riezzo, G., Linsalata, M., Orlando, A., D’Attoma, B., & Russo, F. Psychological and gastrointestinal symptoms of patients with irritable bowel syndrome undergoing a low-FODMAP diet: The role of the intestinal barrier. Nutrients 2021, 13, 2469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moloney, R. D. , Johnson, A. C., O’Mahony, S. M., Dinan, T. G., Greenwood-Van Meerveld, B., & Cryan, J. F. Stress and the microbiota–gut–brain axis in visceral pain: Relevance to irritable bowel syndrome. CNS Neuroscience & Therapeutics 2016, 22, 102–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahurkar-Joshi, S. , & Chang, L. Epigenetic mechanisms in irritable bowel syndrome. Frontiers in Psychiatry 2020, 11, 805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang J, Shi M, Zhao C, Liang G, Li C, Ge X, Pei C, Wang L, et al. Role of intestinal flora in the development of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease in children. Microbiol Spectr. 2023, 11, e01006–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ge L, Liu S, Li S, Yang J, Hu G, Xu C, et al. Psychological stress in inflammatory bowel disease: Psychoneuroimmunological insights into bidirectional gut–brain communications. Front Immunol. 2022, 13, 1016578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, C. , Fan, J., & Qiao, L. Potential epigenetic mechanism in non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. International Journal of Molecular Sciences 2015, 16, 5161–5185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou Q, Yang L, Larson S, Basra S, Merwat S, Tan A, et al. Decreased miR-199 augments visceral pain in patients with IBS through translational upregulation of TRPV1. Gut. 2015, 65, 797–805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elkatry, H. A. , Mohamed, S. M., El-Sayed Hamed, A., Baky, A., Ebrahim, H. A., Ibrahim, A. M., … El-Saleh, S. F. Neuronal modulation of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease: Anti-inflammatory effects of autonomic nervous system innervation. Frontiers in Medicine 2020, 7, 62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wan M, Zhao W, Cai Y, He Q, Zeng J. Role of gut-brain axis dysregulation in the pathogenesis of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease: mechanisms and therapeutic implications. Am J Transl Res. 2025, 17, 3276–3292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Wang SE, Ko SY, Jo S, Choi M, Lee SH, Jo H-R, Seo JY, Lee SH, Kim Y-S, Jung SJ, Son H. TRPV1 regulates stress responses through HDAC2. Cell Rep. 2017, 19, 401–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stewart, N. H. , Kelleher, K. J., & Melnyk, B. M. Personality traits and the risk of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease: A population-based study. Frontiers in Psychology 2022, 13, 830112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim D, Vazquez-Montesino LM, Li AA, Cholankeril G, Ahmed A. Inadequate physical activity and sedentary behavior are independent predictors of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Hepatology. 2020, 72, 1556–1568. [CrossRef]

- Nisticò, V. , Rossi, R. E., D’Arrigo, A. M., Priori, A., Gambini, O., & Demartini, B. Functional Neuroimaging in Irritable Bowel Syndrome: A Systematic Review Highlights Common Brain Alterations With Functional Movement Disorders. Psychosomatic Medicine 2023, 85, 356–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weaver KR, Griffioen MA, Klinedinst NJ, Galik E, Duarte AC, Colloca L, Resnick B, Dorsey SG, Renn CL. Quantitative sensory testing across chronic pain conditions and use in special populations. Front Pain Res (Lausanne). 2022, 2, 779068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weinstein G, O’Donnell A, Davis-Plourde K, Zelber-Sagi S, Ghosh S, DeCarli CS, Thibault EG, Sperling RA, Johnson KA, Beiser AS, Seshadri S. Non-Alcoholic Fatty Liver Disease, Liver Fibrosis, and Regional Amyloid-β and Tau Pathology in Middle-Aged Adults: The Framingham Study. J Alzheimer’s Dis. 2022, 86, 1371–1383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, J. L. , Gu, J. P., Wang, L. Y., Zhu, Q. R., You, N. N., Li, J., Li, J., & Shi, J. P. Aberrant Spontaneous Brain Activity and its Association with Cognitive Function in Non-Obese Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease: A Resting-State fMRI Study. Journal of integrative neuroscience 2023, 22, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z. , Lai, J., Zhang, P., Ding, J., Jiang, J., Liu, C., Huang, H., Zhen, H., Xi, C., Sun, Y., Wu, L., Wang, L., Gao, X., Li, Y., Fu, Y., Jie, Z., Li, S., Zhang, D., Chen, Y., Zhu, Y., … Hu, S. Multi-omics analyses of serum metabolome, gut microbiome and brain function reveal dysregulated microbiota-gut-brain axis in bipolar depression. Molecular psychiatry 2022, 27, 4123–4135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, T. , Yang, Z., Kusumanchi, P., Han, S., & Liangpunsakul, S. Critical role of microRNA-21 in the pathogenesis of liver diseases. Frontiers in Medicine 2023, 10, 1133809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, M. , Hao, Z., Li, M., Xi, H., Hu, S., Wen, J., Gao, Y., Antwi, C. O., Jia, X., Yu, Y., & Ren, J. Functional changes of default mode network and structural alterations of gray matter in patients with irritable bowel syndrome: a meta-analysis of whole-brain studies. Frontiers in neuroscience 2023, 17, 1236069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Icenhour, A. , Witt, S. T., Elsenbruch, S., Lowén, M., Engström, M., Tillisch, K., Mayer, E. A., & Walter, S. Brain functional connectivity is associated with visceral sensitivity in women with Irritable Bowel Syndrome. NeuroImage. Clinical 2017, 15, 449–457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cooke, M. B. , Catchlove, S., & Tooley, K. L. Examining the Influence of the Human Gut Microbiota on Cognition and Stress: A Systematic Review of the Literature. Nutrients 2022, 14, 4623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pirola, C. J. , Scian, R., & Sookoian, S. Epigenetic modifications in the biology of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease: The role of DNA hydroxymethylation and TET proteins. Medicine (Baltimore) 2015, 94, e1480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, Q. , Frick, J. M., O’Neil, M. F., Eller, O. C., Morris, E. M., Thyfault, J. P., Christianson, J. A., & Lane, R. H. Early-life stress perturbs the epigenetics of Cd36 concurrent with adult onset of NAFLD in mice. Pediatric Research 2023, 94, 1942–1950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Winston JH, Li Q, Sarna SK. Chronic prenatal stress epigenetically modifies spinal cord BDNF expression to induce sex-specific visceral hypersensitivity in offspring. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2014, 26, 715–730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carco, C. , Young W., Gearry R. B., Talley N. J., McNabb W. C., Roy N. C. Increasing Evidence That Irritable Bowel Syndrome and Functional Gastrointestinal Disorders Have a Microbial Pathogenesis Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 2020, 10, 468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lyall MJ, Cartier J, Haider A, Healy ME, Bermingham ML, Maher JJ, et al. Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) is associated with dynamic changes in DNA hydroxymethylation. Epigenetics. 2020, 15, 61–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiley JW, Higgins GA. Epigenomics and the Brain–gut Axis: Impact of Adverse Childhood Experiences and Therapeutic Challenges. J Transl Gastroenterol. 2024, 2, 125–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roberts, S. , Lester, K. J., Hudson, J. L., et al. Serotonin transporter methylation and response to cognitive behaviour therapy in children with anxiety disorders. Translational Psychiatry 2014, 4, e444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Quevedo Y, Booij L, Herrera L, Hernández C, Jiménez JP. Potential epigenetic mechanisms in psychotherapy: a pilot study on DNA methylation and mentalization change in borderline personality disorder. Front Hum Neurosci. 2022, 16, 955005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fujii T, Hori H, Ota M, Hattori K, Teraishi T, Sasayama D, Yamamoto N, Higuchi T, Kunugi H. Effect of the common functional FKBP5 variant (rs1360780) on the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis and peripheral blood gene expression. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2014, 42, 89–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Penadés R, Almodóvar-Payá C, García-Rizo C, Ruíz V, Catalán R, Valero S, Wykes T, Fatjó-Vilas M, Arias B. Changes in BDNF methylation patterns after cognitive remediation therapy in schizophrenia: A randomized and controlled trial. J Psychiatr Res. 2024, 173, 166–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Youssef NA, Lockwood L, Su S, Hao G, Rutten BPF. The Effects of Trauma, with or without PTSD, on the Transgenerational DNA Methylation Alterations in Human Offsprings. Brain Sci. 2018, 8, 83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Zheng G, Pang S, Wang J, Wang F, Wang Q, Yang L, Ji M, Xie D, Zhu S, Chen Y, Zhou Y, Higgins GA, Wiley JW, Hou X, Lin R. Glucocorticoid receptor-mediated Nr1d1 chromatin circadian misalignment in stress-induced irritable bowel syndrome. Signal Transduct Target Ther. 2023, 8, 95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinheiro JA, Freitas FV, Borçoi AR, Mendes SO, Conti CL, Arpini JK, Vieira TS, de Souza RA, dos Santos DP, Barbosa WM, Archanjo AB, de Oliveira MM, dos Santos JG, Sorroche BP, Casali-da-Rocha JC, Trivilin LO, Borloti EB, Louro ID, Arantes LMRB, Alvares-da-Silva AM. Alcohol consumption, depression, overweight and cortisol levels as determining factors for NR3C1 gene methylation. Sci Rep. 2021, 11, 6768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jimenez-Rondan F, Pastor-Villaescusa B, Canelles S, Marti A, Samblas M, Riezu-Boj JI, et al. High-fat and high-metal diet alters intestinal barrier integrity via epigenetic modulation of Claudin-1 expression. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2022, 323, G430–G442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kundakovic M, Gudsnuk K, Herbstman JB, Tang D, Perera FP, Champagne FA. DNA methylation of BDNF as a biomarker of early-life adversity. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2015, 112, 6807–6813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, F. , Glaser, S. S., Francis, H., Yang, F., Han, Y., Stokes, A., Staloch, D., McCarra, J., Liu, J., Venter, J., Zhao, H., Liu, X., Francis, T., Swendsen, S., Liu, C.-G., Tsukamoto, H., & Alpini, G. Epigenetic regulation of miR-34a expression in alcoholic liver injury. The American Journal of Pathology 2012, 181, 804–817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wadan, A.-H. S. , Abd El-Aziz, M. K., & El-Sayed Ellakwa, D. The microbiota-gut-brain-axis theory: Role of gut microbiota modulators (GMMs) in gastrointestinal, neurological, and mental health disorders. Naunyn-Schmiedeberg’s Archives of Pharmacology 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai R, Lv R, Shi X, Yang G, Jin J. CRISPR/dCas9 Tools: Epigenetic Mechanism and Application in Gene Transcriptional Regulation. Int J Mol Sci. 2023, 24, 14865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Yan L, Wei JA, Yang F, Wang M, Wang S, Cheng T, Liu X, Jia Y, So KF, Zhang L. Physical Exercise Prevented Stress-Induced Anxiety via Improving Brain RNA Methylation. Adv Sci 2022, 9, e2105731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).