1. Introduction

Secondary oil recovery plays a critical role in hydrocarbon extraction, aiming to enhance recovery beyond the capabilities of primary methods. After the initial production phase, which relies on the reservoir’s natural energy, secondary recovery techniques, such as water and-or gas injection, are employed to sustain or restore reservoir pressure. These methods not only improve extraction efficiency and extend the productive lifespan of oil fields but also contribute to reducing the environmental footprint of oil exploration and production while optimizing the economic viability of recovery operations [

1]. In this context, for more than half a century, waterflooding has served as a reliable method of maintaining reservoir pressure and increasing oil production efficiency [

2,

3,

4,

5,

6,

7].

Given the importance of advanced oil recovery methods, laboratory scale models are critical for understanding not only the dynamics of multiphase flows in heterogeneous porous media, but also the properties of the reservoir rock, to properly plan water floods [

8,

9]. Coreflood experiments, for example, allow researchers to simulate and study flow behavior under controlled conditions, revealing important information about the mechanisms of oil displacement and the effectiveness of various recovery techniques [

10]. These experiments provide important data for inverse problems, allowing the determination of intrinsic properties of the plug subjected to fluid flow, such as relative permeabilities [

11,

12,

13,

14,

15,

16,

17].

A significant body of research has focused on numerically predicting water saturation dynamics and oil recovery in porous media, aiming to elucidate the complexities of multiphase flow in both multidimensional [

18,

19,

20] and one-dimensional frameworks [

21,

22,

23]. One-dimensional models, such as the Buckley-Leverett formulation and its variations [

12,

24,

25,

26], have been widely used to study two-phase flow in porous media. These simplified formulations effectively capture the fundamental physics of the problem while offering cost effective solutions, making them invaluable for understanding flow behavior in complex systems.

However, since these solutions neglect the influence of capillary pressure, they fail to accurately represent flows where this effect plays a significant role. Incorporating such terms introduces a strong nonlinear behavior into the problem. Nonlinear convective and diffusive effects and-or nonlinear source terms are frequently encountered in transport phenomena modeling, often resulting in nonlinear partial differential equations. These nonlinear formulations are generally unsolvable using traditional analytical methods [

27,

28,

29,

30]. Instead, they typically require approximate numerical approaches [

31,

32,

33,

34] or the application of mathematical techniques that involve dependent or independent variable transformations in specific formulations or approximate analytical solutions of limited scope [

35,

36,

37,

38].

As a result, numerical approaches have become the dominant choice for tackling nonlinear problems, supported by a range of effective algorithms and schemes. Nonetheless, there is a growing need to further improve the efficiency of computationally intensive processes, particularly in applications involving nonlinear formulations. These challenges are especially relevant in tasks such as inverse problems, optimization and uncertainty quantification, due to the usually required large number of runs of the direct problem solution, where the demand for scalability and computational feasibility continues to rise [

39].

In response to the limitations of classical exact or approximate analytical solution techniques, the development of hybrid approaches that combine analytical and numerical techniques has gained significant traction. Among these, one particularly notable and mature methodology is the Generalized Integral Transform Technique (GITT). Initially introduced by Cotta and Ozisik [

40] and subsequently extended through numerous contributions [

41,

42,

43,

44,

45,

46,

47,

48,

49,

50,

51,

52,

53], GITT generalized the classical integral transform method originally developed for linear diffusion problems [

27,

28,

29]. This meshless technique demonstrates the effective combination of the accuracy and computational efficiency of analytical solutions with the flexibility and generality of numerical solutions to tackle intricate engineering challenges, yielding error controlled solutions with moderate computational expense, allowing seamless incorporation with different tasks that demand extensive direct model evaluations.

The application of the Generalized Integral Transform Technique (GITT) to nonlinear problems is based on the idea that nonlinear partial differential equations can be reformulated to confine the nonlinear terms within the source terms, both in the governing equations and boundary conditions. This reformulation preserves linear characteristic coefficients, which define the associated eigenvalue problem. Through eigenfunction expansion and the integral transformation process, the reformulated nonlinear partial differential equation is transformed into a system of coupled, nonlinear, infinite transformed ordinary differential equations. This transformed ODEs system is then numerically solved to determine the transformed potentials, facilitating the analysis of complex nonlinear dynamics in the original problem.

Over the past three decades, following the introduction of GITT for nonlinear problems, this methodology has been progressively expanded to address a wide range of challenges. These extensions include applications to nonlinear models featuring variable physical properties, nonlinear source terms in both governing equations and boundary conditions, moving boundary problems, irregular domains, eigenvalue problems, nonlinear convection, diffusion or reaction-dissipation effects [

41,

42,

43,

45,

46,

47,

48,

49,

51,

54]. Recent applications of GITT that involve flow and transport in porous media can be cited such as pumping in confined, leaky, and unconfined aquifers [

55], flow on fractured heterogeneous porous media [

56], and flow in variably saturated porous media [

57]. In reservoir engineering, GITT has been used in three-dimensional transient flow in heterogeneous reservoirs [

58], two-dimensional energy balance for the transient temperature of sand faces in wells with mixed production [

59], analysis of one-dimensional oil displacement by water injection in a core plug [

60], and the two-dimensional convection-diffusion problem for tracer flow in a five-spot pattern [

61,

62].

Based on the discussion above and considering the potential of GITT and the importance of the addressed topic, this work presents a hybrid solution via GITT for immiscible two-phase flow in porous media with capillary pressure effects, which are highly relevant for reservoir studies. The formulation considers a two-phase flow in heterogeneous porous media, presenting linear and classical boundary conditions, which are independent of capillary pressure. In this demonstration, the effect of water injection at the rock’s boundary is expressed by a Dirichlet boundary condition, where the water saturation is at its maximum. The Kirchhoff transformation [

28,

37,

63,

64,

65,

66] is used to incorporate the nonlinearity of the diffusive operator originating from the capillary pressure into the transformed dependent variable to prepare the governing equation for the integral transformation via GITT. The test-case results here presented focus on the dynamics of the transformed and reconstructed solutions, highlighting convergence behavior, verification against an approximate numerical solution, and discusses the accuracy of low-order approximations.

3. Results

3.1. Convergence Analysis

This section presents the convergence analysis of the proposed integral transform solution. The truncation order in the eigenfunction expansion is initially fixed at , and the results are examined for different number of terms in the resulting series, in order to inspect the convergence behavior of the proposed expansion. All numerical integrations for the transformed system matrices and initial conditions vector are performed using Gaussian quadrature with points, ensuring that integration errors remain sufficiently low and controlled below the desired four digits accuracy in the final results throughout the analysis.

To accelerate and further verify the expansion convergence, the first-level Shanks transformation is applied to the partial sums of each sequence. The Shanks method provides an accelerated estimate of the series limit, which also serves as an additional consistency check for the computed values. Given the favorable convergence behavior already observed for moderate values of N, the contribution of the Shanks transformation in accelerating convergence is useful mostly at lower time values, yet confirms the robustness of the solution procedure.

The numerical results are summarized in

Table 2,

Table 3 and

Table 4, for three distinct time instants (

). In all cases, the solution

is evaluated at five representative spatial positions (

). A clear trend of convergence is observed as

N increases, with full convergence to four significant digits at the highest value of

N (± 1 in the last digit given), as confirmed by the Shanks transformation.

To complement the convergence study, a relative error analysis is conducted to quantify the accuracy of the truncated eigenfunction expansions. The objective is to assess how the partial sum of

N terms compares to a reference solution obtained with

terms. The relative residue estimate

is defined as:

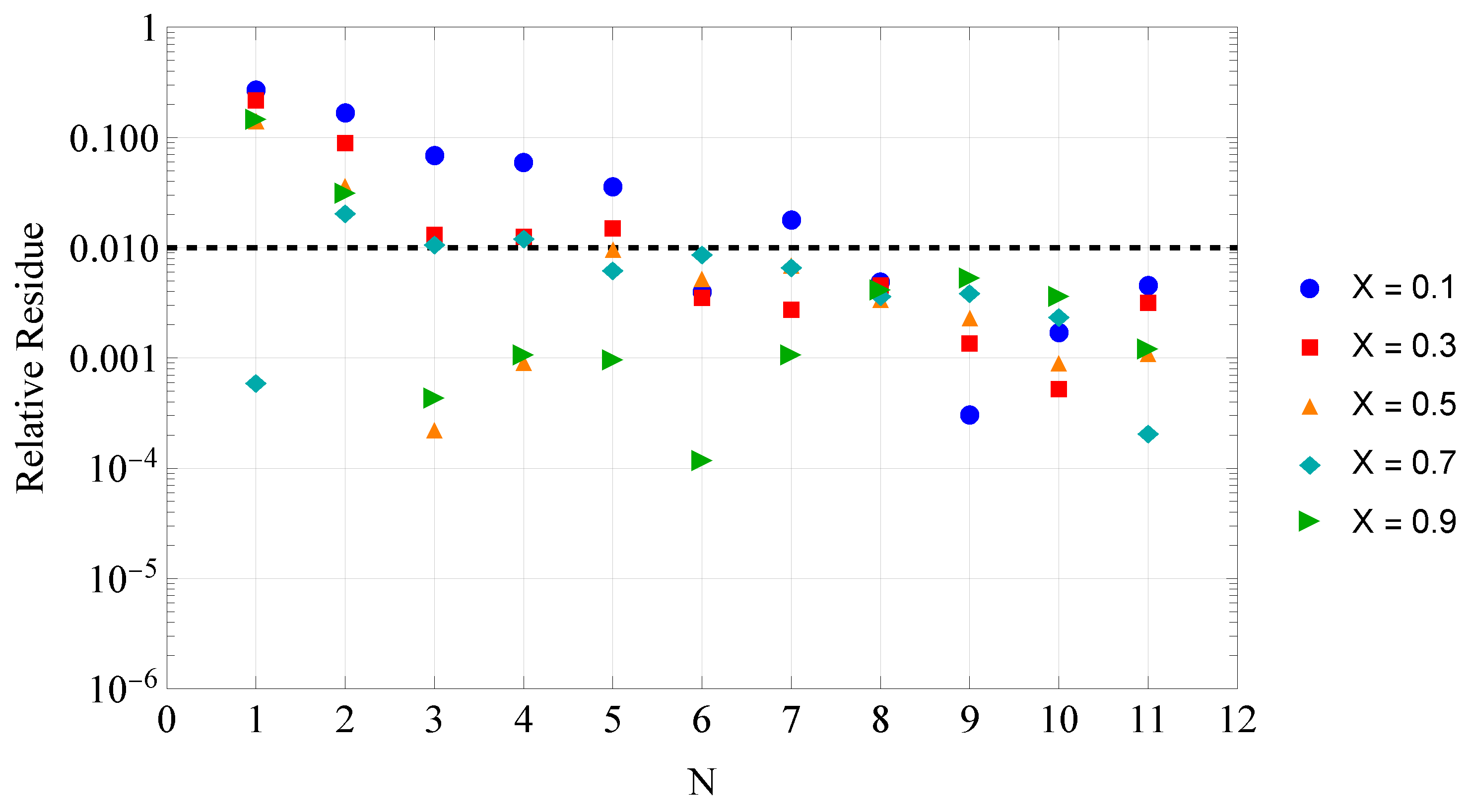

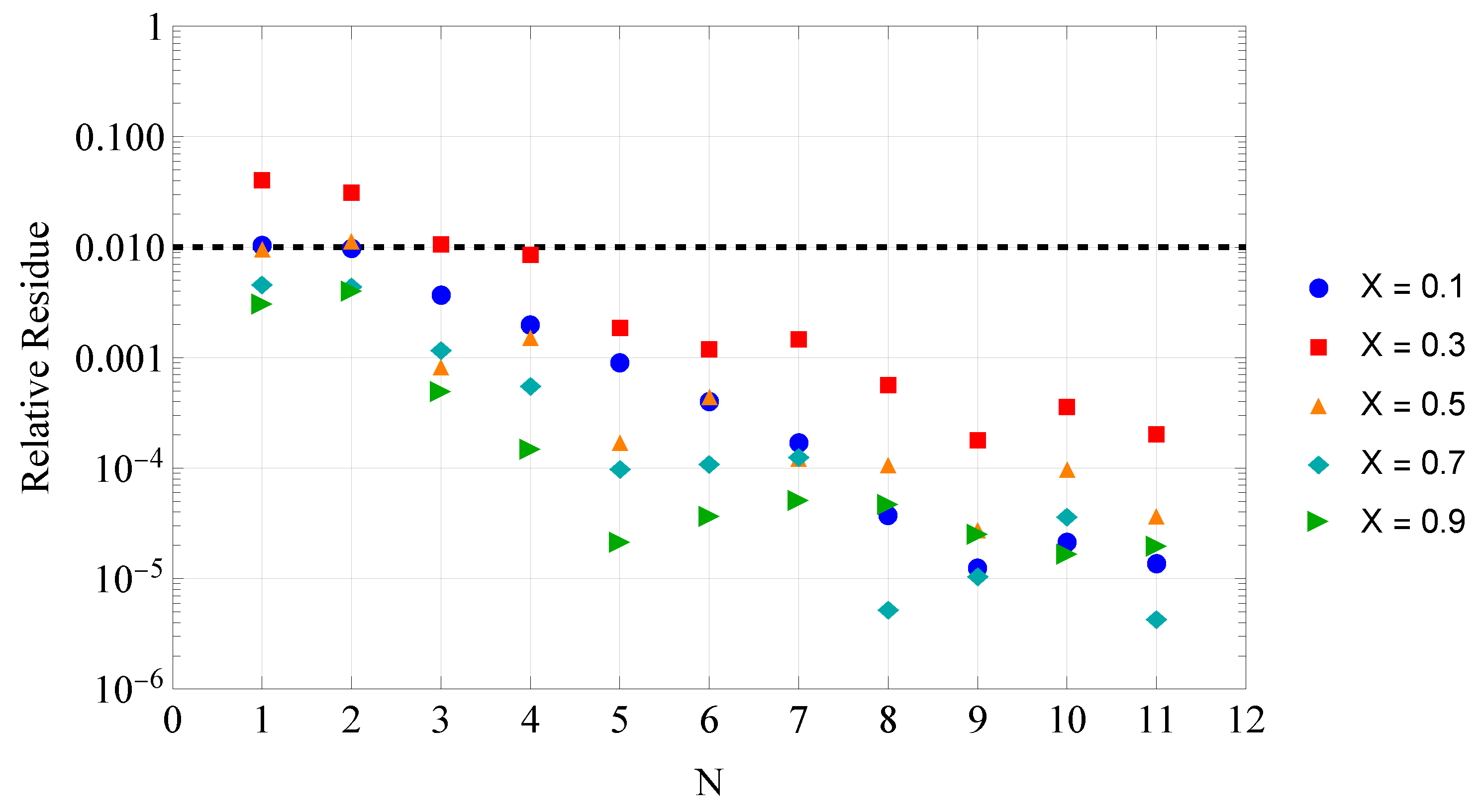

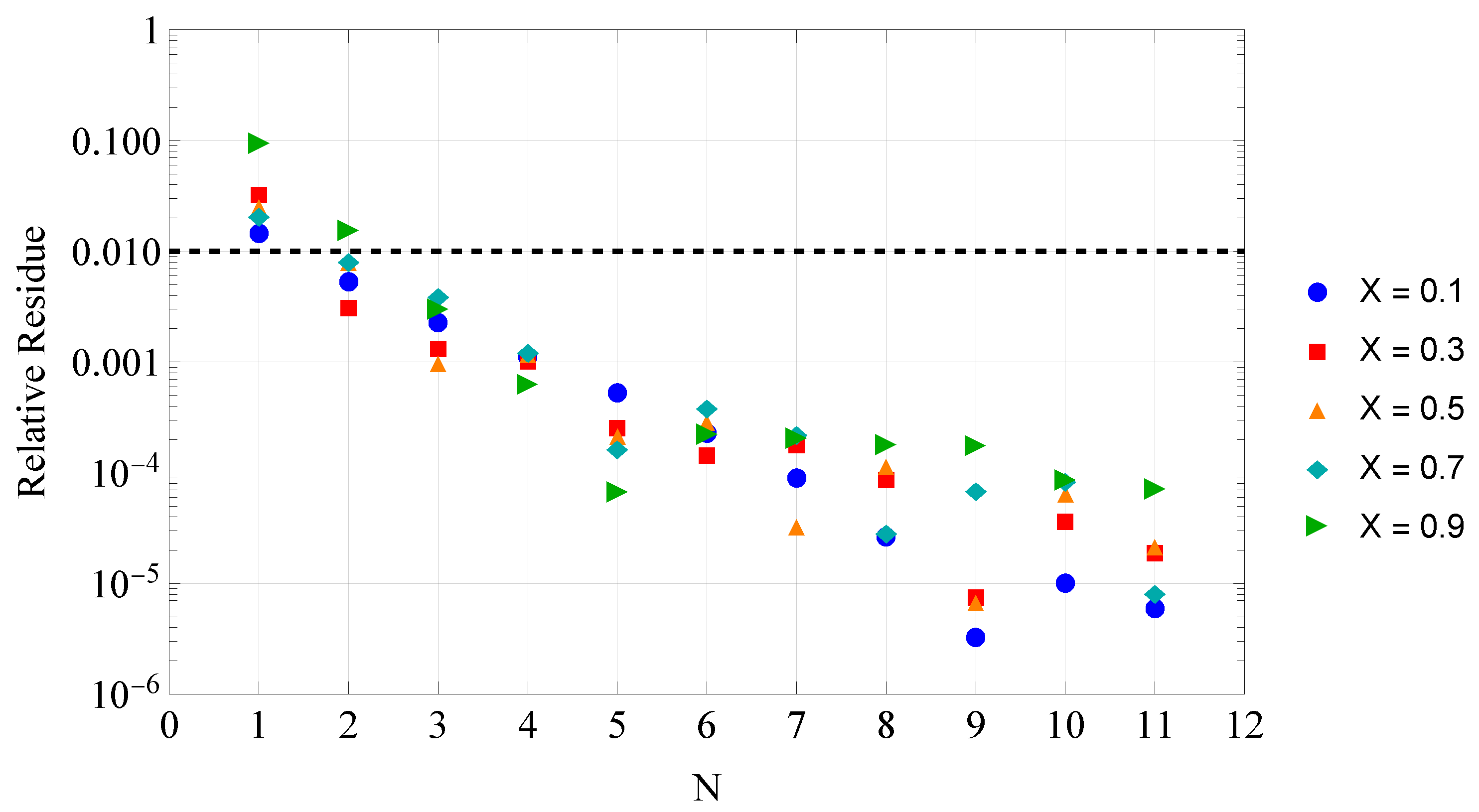

The results presented on

Figure 3,

Figure 4 and

Figure 5, for five different dimensionless positions and three different times, demonstrate that even for relatively low truncation levels, such as

, the relative residue remains below 1% at all relevant spatial and temporal positions. This highlights the efficiency of the proposed methodology in capturing the dominant dynamics of the system with a reduced computational cost.

The convergence tables presented so far refer to the values of computed at selected spatial positions and time instants. However, from a physical point of view, one needs to analyze the behavior of the water saturation , as this variable directly represents the fluid distribution within the porous medium. For completeness, we therefore provide below the corresponding convergence tables for , evaluated at the same dimensionless spatial positions and time instants used previously for .

These results are obtained by post-processing the values of through a numerical interpolation of the inverse Kirchhoff transform, but were also critically compared with the direct inversion through the nonlinear algebraic equation solver, without making use of the interpolated curve, and no difference has been observed with respect to the results shown below.

Table 5.

Convergence of for s and N up to 12.

Table 5.

Convergence of for s and N up to 12.

| N |

|

|

|

|

|

| 2 |

0.5608 |

0.4669 |

0.4043 |

0.3421 |

0.2 |

| 4 |

0.5578 |

0.4665 |

0.4056 |

0.3414 |

0.2 |

| 6 |

0.5579 |

0.4665 |

0.4056 |

0.3413 |

0.2 |

| 8 |

0.5584 |

0.4660 |

0.4055 |

0.3431 |

0.2 |

| 10 |

0.5586 |

0.4662 |

0.4056 |

0.3426 |

0.2 |

| 12 |

0.5586 |

0.4662 |

0.4055 |

0.3424 |

0.2 |

| Shanks |

0.5586 |

0.4662 |

0.4055 |

0.3424 |

0.2 |

Table 6.

Convergence of for s and N up to 12.

Table 6.

Convergence of for s and N up to 12.

| N |

|

|

|

|

|

| 2 |

0.5888 |

0.5096 |

0.4670 |

0.4405 |

0.4271 |

| 4 |

0.5876 |

0.5092 |

0.4674 |

0.4407 |

0.4269 |

| 6 |

0.5874 |

0.5093 |

0.4673 |

0.4408 |

0.4269 |

| 8 |

0.5873 |

0.5092 |

0.4673 |

0.4408 |

0.4269 |

| 10 |

0.5873 |

0.5092 |

0.4673 |

0.4408 |

0.4269 |

| 12 |

0.5873 |

0.5092 |

0.4673 |

0.4408 |

0.4269 |

| Shanks |

0.5873 |

0.5092 |

0.4673 |

0.4408 |

0.4269 |

Table 7.

Convergence of for s and N up to 12.

Table 7.

Convergence of for s and N up to 12.

| N |

|

|

|

|

|

| 2 |

0.6318 |

0.5687 |

0.5380 |

0.5213 |

0.5139 |

| 4 |

0.6304 |

0.5683 |

0.5384 |

0.5215 |

0.5137 |

| 6 |

0.6302 |

0.5684 |

0.5383 |

0.5215 |

0.5137 |

| 8 |

0.6301 |

0.5684 |

0.5384 |

0.5215 |

0.5137 |

| 10 |

0.6301 |

0.5684 |

0.5384 |

0.5215 |

0.5137 |

| 12 |

0.6301 |

0.5684 |

0.5384 |

0.5215 |

0.5137 |

| Shanks |

0.6301 |

0.5684 |

0.5384 |

0.5215 |

0.5137 |

In all examined time instants, the values of exhibit a clear convergence trend as N increases. Convergence to three significant digits can be observed for truncation orders as low as even at the lowest value of time. The application of the Shanks transformation further confirms this observation.

3.2. Verification Analysis

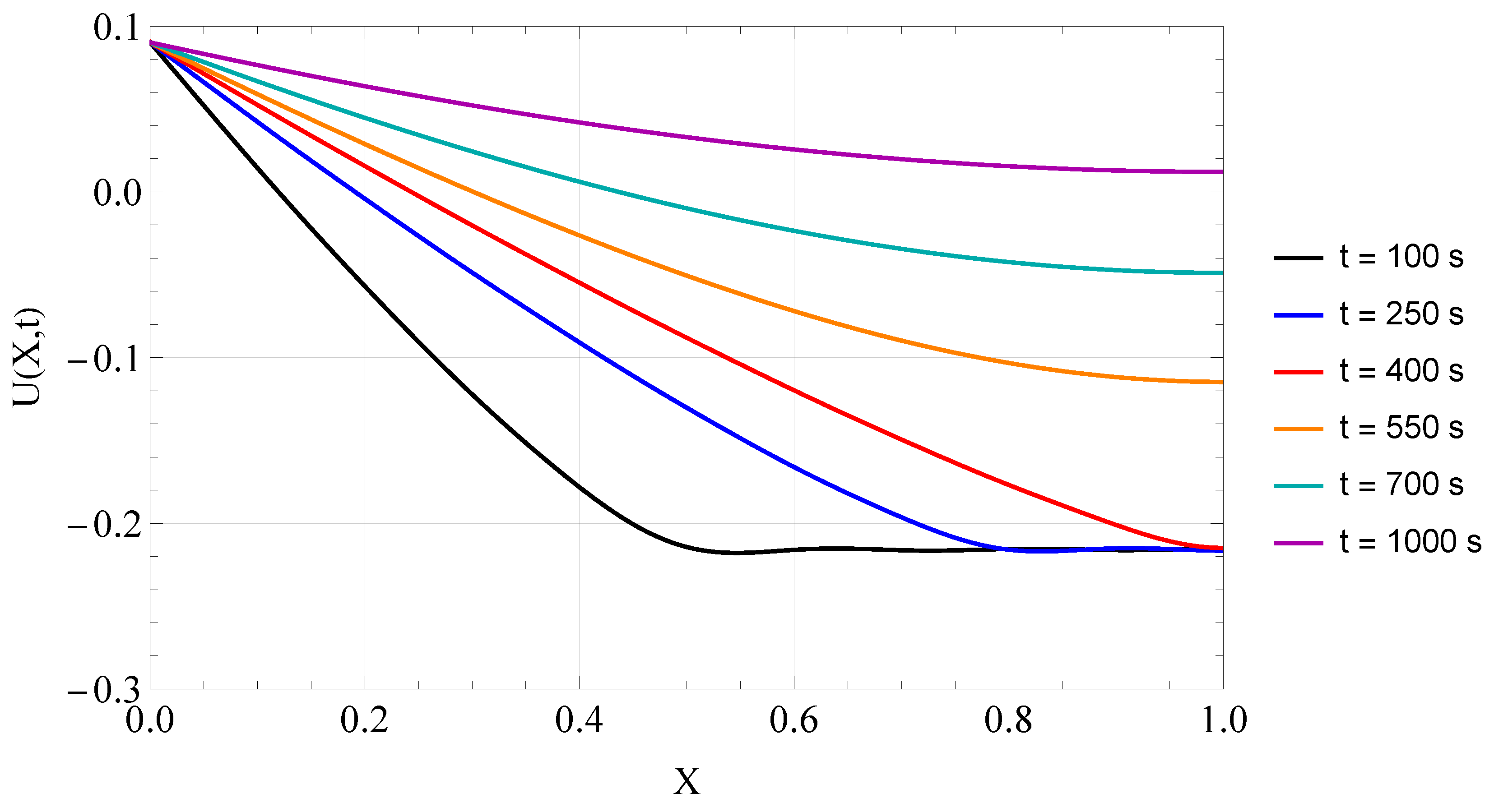

Figure 6 illustrates the spatial evolution of

at selected time instants, namely

s. These time points were chosen to encompass both the initial transient regime and the post-breakthrough phase of the saturation front. The results show that the solution maintains a smooth and well-behaved structure throughout the spatial domain for all times considered. Only for the lowest time value (

) it can be noticed, after careful inspection, that the transition region after the saturation front might require a few more terms in the expansion.

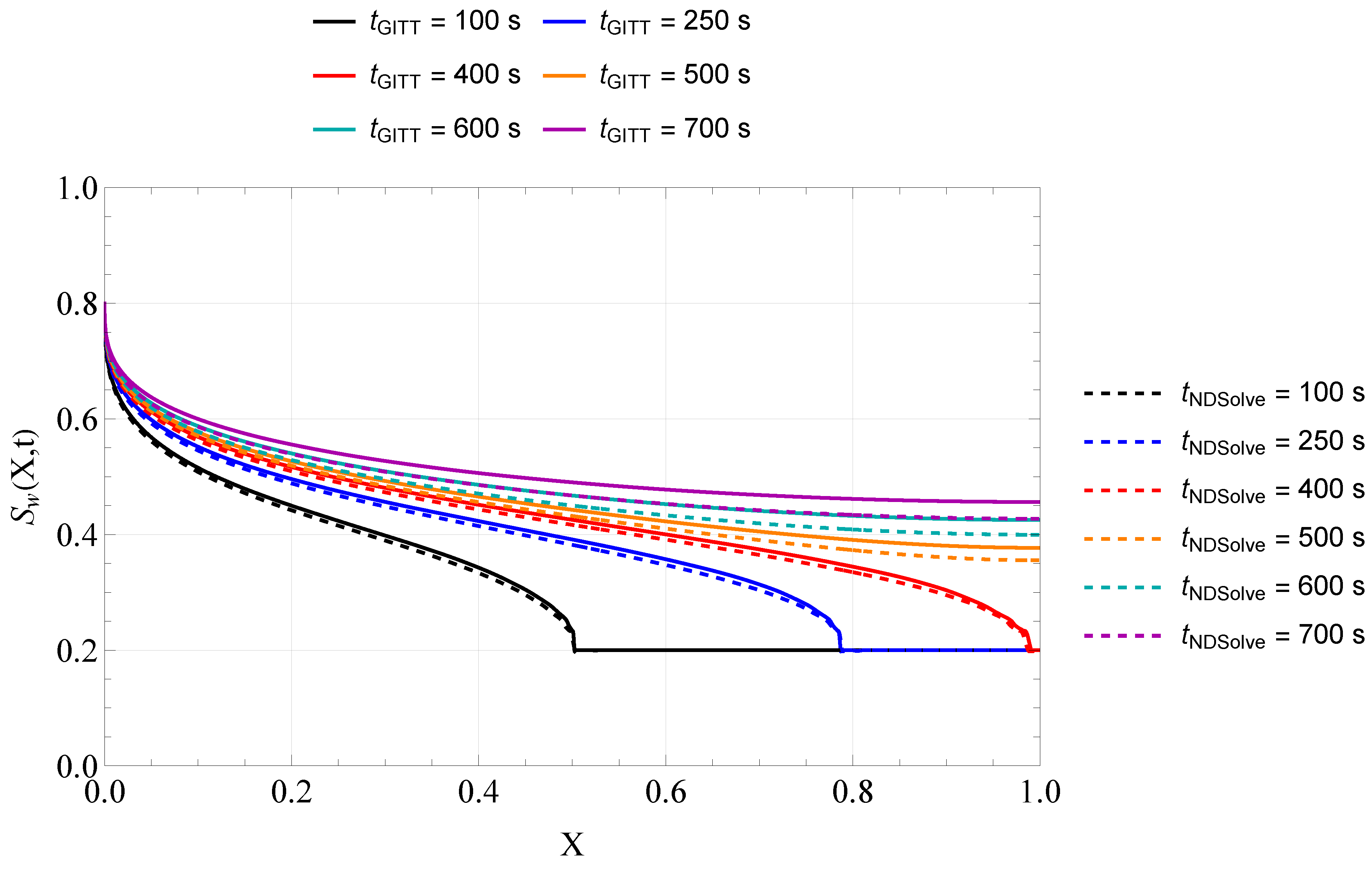

Figure 7 presents a verification analysis performed by comparing the proposed solution with a numerical solution obtained using

NDSolve,

Mathematica’s built-in PDE solver. Due to numerical instabilities encountered when solving the full nonlinear PDE directly, it was necessary to benefit from the Kirchoff transformation as well. Even then,

NDSolve was not able to handle the nonlinearity due to the capillary pressure, and it was necessary to introduce a simplification in the diffusive term, the nonlinear coefficient

was evaluated using the known solution obtained by the present method itself. This semi-coupled strategy yielded an approximate numerical result that still serves as a meaningful result for verification purposes.

The comparison revealed a good agreement between the proposed solution and the approximate numerical solution with NDSolve, particularly at early and intermediate times. As expected, a gradual loss of accuracy is observed at larger times, which is attributable to the approximation introduced and propagated in the numerical solution by NDSolve. in the numerical model. Nevertheless, the level of agreement remains sufficient to verify the GITT-based solution.

3.3. Low Order Truncation Solution

In the context of inverse problems and other computationally intensive tasks that require multiple evaluations of the direct problem solution, the use of low-order truncation expansions is particularly attractive, in combination with the Approximation Error Model (AEM) methodology [

73,

74], as it significantly reduces computational cost, without compromising the overall precision in the estimations. In this section, we investigate the behavior of the solution when the number of terms is limited to

.

It is important to emphasize that when the eigenfunction expansion is restricted to low order truncation such as , it is inherently assumed that all transformed components for are identically zero. On the other hand, one may also extract the truncated expansions for instance up to from a computed solution with , in which case the contributions from higher-order modes ( to 12) are present in the solution space but excluded from the partial sum. As such, these two approaches yield different results, and this distinction becomes relevant when evaluating the implications of model truncation in inverse analyses, combined with the AEM approach.

To illustrate the behavior of a low truncation expansion, we compare three sets of results for three representative time instants: (i) direct computations with increasing

N up to 6 (with

); (ii) the Shanks-transformed value at

; and (iii) the truncated expansion at

extracted from the

truncated expansion.

Table 8,

Table 9, and

Table 10 report the values of

for each time value

at five spatial positions.

The comparison reveals that the direct solutions are remarkably close to the Shanks accelerated estimates, which confirms that the expansion with is essentially converged. Nevertheless, when comparing with the truncated sum at of the expansion with terms, the deviations are more noticeable, though always below 2.5% from these tables, but for accurate estimates should be accounted for by the approximation error model when implementing the inverse problem analysis.

This observation supports the use of low-order truncations, such as in the present example, as efficient and reliable. Therefore, the results suggest that a truncated solution with can serve as a robust surrogate for the full model in inverse formulations, enabling efficient parameter estimation while preserving the essential physical features of the system.

In sequence, we analyze the influence of the numerical integration accuracy on the final solution, by varying the number of Gaussian quadrature points used in the evaluation of the transformed terms . Although all previous results were computed with to eliminate integration-induced errors from the convergence study, it is relevant to assess the effect of reducing , particularly in the context of inverse problems, when computational savings are always at a premium.

Table 11,

Table 12 and

Table 13 present the values of

obtained for

and

, for the same spatial positions and time instants previously analyzed. The Shanks transformation results computed with

are included for comparison.

The results indicate that the solution converges rapidly with respect to , and that already provides values very close to the reference with and . At , the results are already converged to ± 1 in the fourth significant digit, indicating that the numerical integration error becomes irrelevant to within the desired accuracy in the final results.

For applications that require a large number of the direct problem evaluations, such as most parameter estimation in inverse formulations, this reduction in integration cost can lead to substantial performance gains.

4. Discussion

The results presented in the previous sections confirm the robustness, efficiency, and accuracy of the proposed solution for immiscible two-phase flow in porous media based on the Generalized Integral Transform Technique (GITT). The convergence analysis demonstrated that a relatively low number of terms in the truncated eigenfunction expansion (

) suffices to achieve converged and precise solutions for both the Kirchhoff-transformed variable

and the physically meaningful saturation field

. The use of the Kirchhoff transform is handy in partially incorporating the nonlinearity due to the capillary pressure effect into the dependent variable and thus reducing the stiffness in the transformed ODE system numerical solution. Besides, as previously observed in [

39], it offers an inherent convergence acceleration bonus, as more information on the original problem nonlinear diffusive operator is aggregated to the dependent variable. These findings are particularly relevant in the context of inverse problems, where computational tractability is a key requirement.

The agreement between the GITT-based solution and the approximate numerical one provided by NDSolve provides verification of the implemented simulation. Despite the simplification that had to be adopted in the numerical simulation, where the nonlinear coefficient in the diffusive term was evaluated from the hybrid GITT solution itself, the match remains consistently good across the spatial and temporal domains. Minor discrepancies at longer times are attributed to the error propagation in the approximate numerical procedure rather than flaws in the proposed methodology.

From a computational standpoint, the analysis of numerical integration effects revealed that Gaussian quadrature with as few as points already yields negligible error to the final water saturation results at the lower truncation order or , indicating that the method is not only accurate but also computationally efficient. This supports the potential use of the present formulation in repeated simulations, such as those encountered in parameter estimation or uncertainty quantification tasks.

Moreover, the truncated low-order reduced model was shown to retain the essential features of the full solution while offering significant reductions in computational cost. The comparison between the truncated models and the higher-order solution confirms that even the low order truncated expansion preserved accuracy always below 2.5%, which is certainly acceptable for combining with the AEM for inverse problem analysis. This suggests that the approach can serve as a reliable reduced-order model in inverse formulations, where repeated forward evaluations are required.

In the broader context of modeling nonlinear flow in porous media, the present methodology offers a valuable alternative to conventional numerical solvers. It combines the interpretability and structure of analytical approaches with the flexibility of numerical integration, enabling hybrid strategies that are particularly well-suited for data assimilation, control, inverse problems, and optimization scenarios.

Future research may extend the current formulation to include more complex boundary conditions and multi-dimensional geometries. The flexibility of the integral transform approach also allows for its integration with Bayesian inference frameworks, further expanding its applicability in modern reservoir characterization workflows.

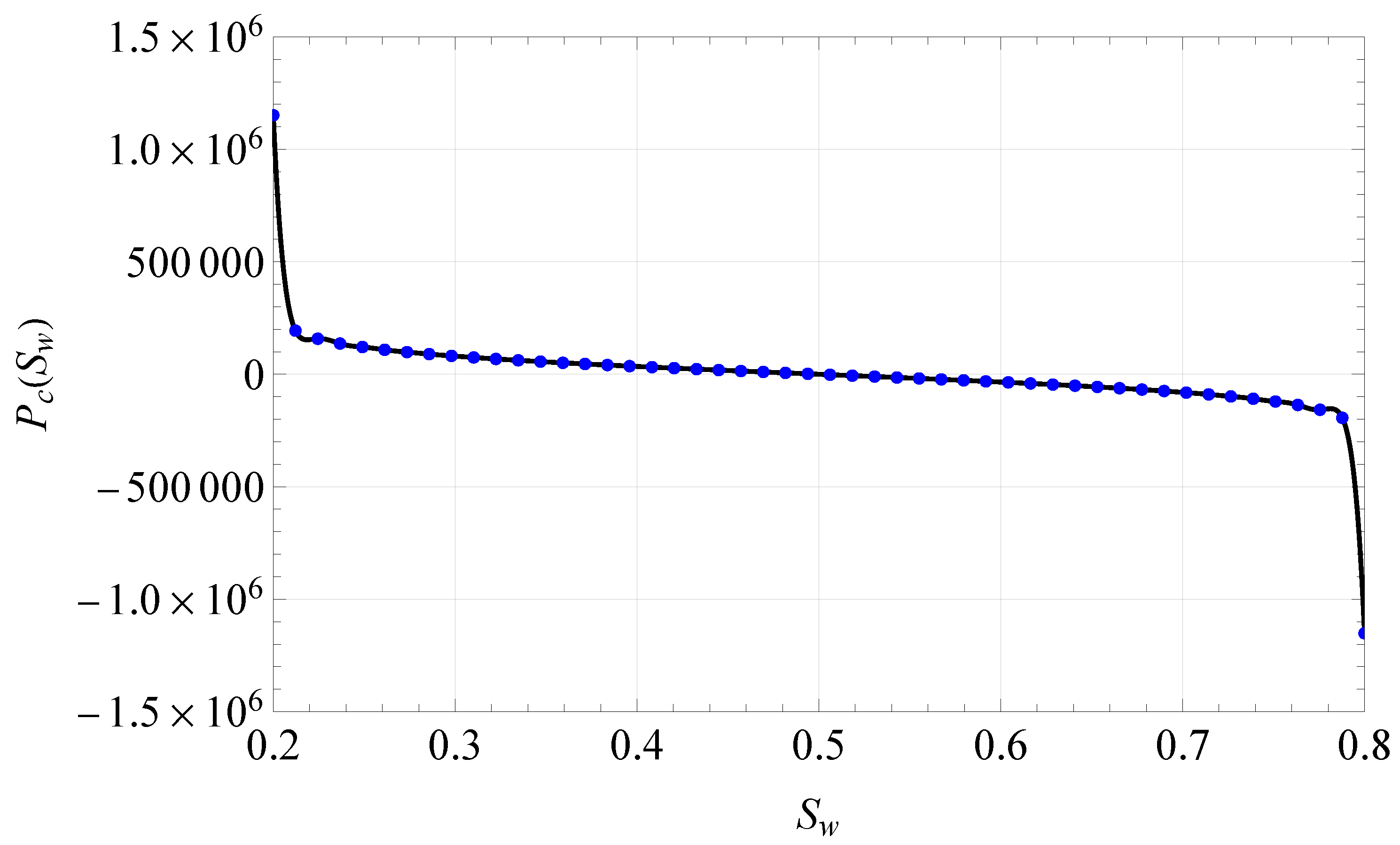

Figure 1.

Original

data provided by [

68] (blue dots) and the interpolation used (black curve).

Figure 1.

Original

data provided by [

68] (blue dots) and the interpolation used (black curve).

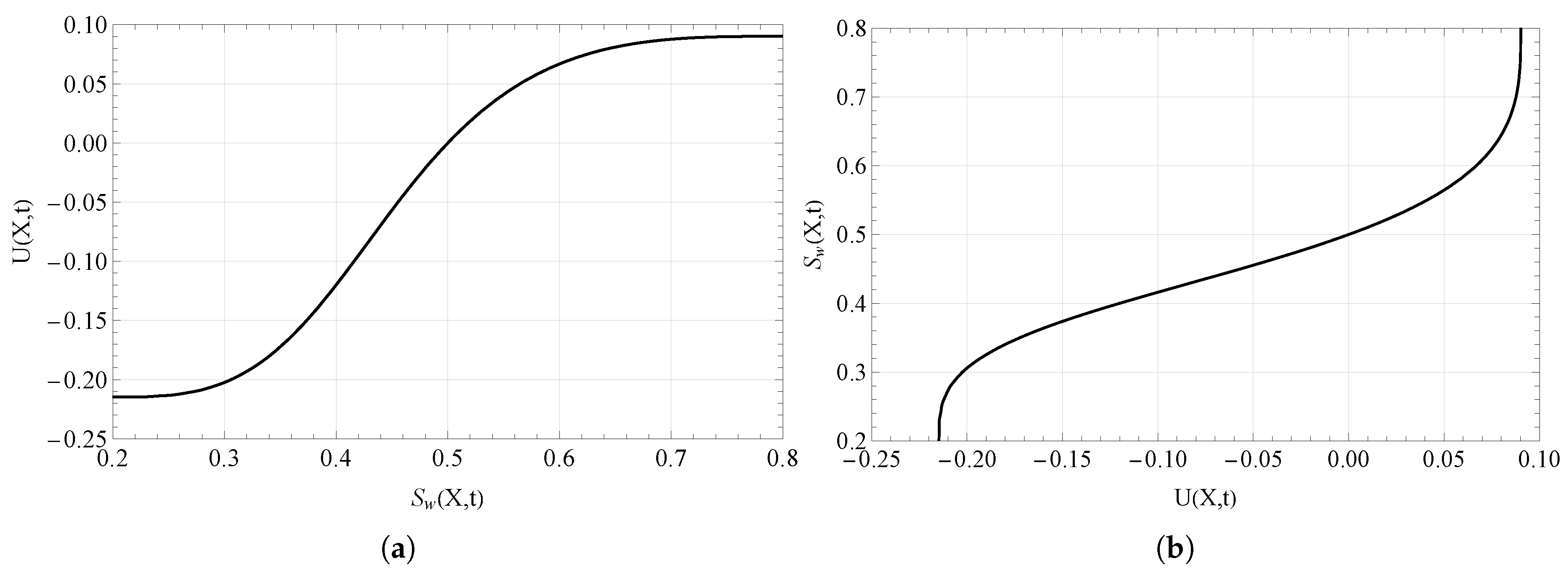

Figure 2.

Graphical illustration of the Kirchhoff transformation and its inversion, with plots of (a) versus and (b) versus .

Figure 2.

Graphical illustration of the Kirchhoff transformation and its inversion, with plots of (a) versus and (b) versus .

Figure 3.

Relative residue estimate for at s.

Figure 3.

Relative residue estimate for at s.

Figure 4.

Relative residue estimate for at s.

Figure 4.

Relative residue estimate for at s.

Figure 5.

Relative residue estimate for at s.

Figure 5.

Relative residue estimate for at s.

Figure 6.

Computed profiles of across the spatial domain for different time instants .

Figure 6.

Computed profiles of across the spatial domain for different time instants .

Figure 7.

Comparison of profiles computed via the GITT approach (solid lines) and the NDSolve approximate numerical solution (dashed lines), across the spatial domain and multiple time instants.

Figure 7.

Comparison of profiles computed via the GITT approach (solid lines) and the NDSolve approximate numerical solution (dashed lines), across the spatial domain and multiple time instants.

Table 1.

Physical properties and other input data.

Table 1.

Physical properties and other input data.

| Property |

Symbol |

Value |

Unit |

| Maximum water relative permeability |

|

|

- |

| Maximum oil relative permeability |

|

|

- |

| Exponent in model |

|

3 |

- |

| Exponent in model |

|

3 |

- |

| Irreducible oil saturation |

|

|

- |

| Irreducible water saturation |

|

|

- |

| Porosity |

|

|

- |

| Water viscosity |

|

|

kg·m−1·s−1

|

| Oil viscosity |

|

|

kg·m−1·s−1

|

| Core diameter |

D |

|

m |

| Absolute permeability |

K |

100 |

mD |

| Injected water flow rate |

q |

1 |

cm3·h−1

|

| Core length |

L |

|

m |

Table 2.

Convergence of for s and N up to 12.

Table 2.

Convergence of for s and N up to 12.

| N |

|

|

|

|

|

| 2 |

0.04847 |

-0.03647 |

-0.1162 |

-0.1809 |

-0.2178 |

| 4 |

0.04661 |

-0.03696 |

-0.1146 |

-0.1815 |

-0.2179 |

| 6 |

0.04667 |

-0.03702 |

-0.1146 |

-0.1816 |

-0.2179 |

| 8 |

0.04696 |

-0.03764 |

-0.1147 |

-0.1802 |

-0.2188 |

| 10 |

0.04712 |

-0.03733 |

-0.1146 |

-0.1806 |

-0.2195 |

| 12 |

0.04713 |

-0.03731 |

-0.1147 |

-0.1807 |

-0.2197 |

| Shanks |

0.04711 |

-0.03736 |

-0.1147 |

-0.1807 |

-0.2198 |

Table 3.

Convergence of for s and N up to 12.

Table 3.

Convergence of for s and N up to 12.

| N |

|

|

|

|

|

| 2 |

0.06305 |

0.009250 |

-0.03644 |

-0.06956 |

-0.08694 |

| 4 |

0.06252 |

0.008871 |

-0.03593 |

-0.06930 |

-0.08727 |

| 6 |

0.06242 |

0.008964 |

-0.03601 |

-0.06925 |

-0.08729 |

| 8 |

0.06239 |

0.008958 |

-0.03598 |

-0.06926 |

-0.08729 |

| 10 |

0.06239 |

0.008949 |

-0.03599 |

-0.06926 |

-0.08728 |

| 12 |

0.06239 |

0.008951 |

-0.03599 |

-0.06926 |

-0.08728 |

| Shanks |

0.06239 |

0.008951 |

-0.03599 |

-0.06926 |

-0.08728 |

Table 4.

Convergence of for s and N up to 12.

Table 4.

Convergence of for s and N up to 12.

| N |

|

|

|

|

|

| 2 |

0.07796 |

0.05304 |

0.03312 |

0.01980 |

0.01328 |

| 4 |

0.07760 |

0.05280 |

0.03346 |

0.01994 |

0.01308 |

| 6 |

0.07752 |

0.05286 |

0.03340 |

0.01998 |

0.01306 |

| 8 |

0.07751 |

0.05286 |

0.03342 |

0.01997 |

0.01306 |

| 10 |

0.07750 |

0.05285 |

0.03341 |

0.01997 |

0.01307 |

| 12 |

0.07750 |

0.05286 |

0.03342 |

0.01997 |

0.01307 |

| Shanks |

0.07750 |

0.05285 |

0.03342 |

0.01997 |

0.01307 |

Table 8.

Convergence of for s and N up to 6 .

Table 8.

Convergence of for s and N up to 6 .

| N |

|

|

|

|

|

| 1 |

0.5525 |

0.4573 |

0.3962 |

0.3396 |

0.2737 |

| 2 |

0.5595 |

0.4651 |

0.4018 |

0.3375 |

0.2000 |

| 3 |

0.5593 |

0.4650 |

0.4019 |

0.3377 |

0.2000 |

| 4 |

0.5569 |

0.4652 |

0.4029 |

0.3354 |

0.2000 |

| 5 |

0.5583 |

0.4645 |

0.4034 |

0.3348 |

0.2000 |

| 6 |

0.5573 |

0.4650 |

0.4030 |

0.3352 |

0.2000 |

| Shanks |

0.5577 |

0.4648 |

0.4032 |

0.3350 |

0.2000 |

| 6 (N=12) |

0.5579 |

0.4665 |

0.4056 |

0.3413 |

0.2000 |

Table 9.

Convergence of for s and N up to 6 .

Table 9.

Convergence of for s and N up to 6 .

| N |

|

|

|

|

|

| 1 |

0.5846 |

0.5037 |

0.4598 |

0.4320 |

0.4176 |

| 2 |

0.5857 |

0.5048 |

0.4604 |

0.4318 |

0.4168 |

| 3 |

0.5848 |

0.5044 |

0.4608 |

0.4321 |

0.4165 |

| 4 |

0.5846 |

0.5044 |

0.4608 |

0.4321 |

0.4165 |

| 5 |

0.5845 |

0.5045 |

0.4608 |

0.4321 |

0.4165 |

| 6 |

0.5845 |

0.5045 |

0.4608 |

0.4321 |

0.4165 |

| Shanks |

0.5845 |

0.5045 |

0.4608 |

0.4321 |

0.4165 |

| 6 (N=12) |

0.5874 |

0.5093 |

0.4673 |

0.4408 |

0.4269 |

Table 10.

Convergence of for s and N up to 6 .

Table 10.

Convergence of for s and N up to 6 .

| N |

|

|

|

|

|

| 1 |

0.6328 |

0.5690 |

0.5363 |

0.5174 |

0.5085 |

| 2 |

0.6297 |

0.5658 |

0.5347 |

0.5177 |

0.5102 |

| 3 |

0.6287 |

0.5654 |

0.5350 |

0.5180 |

0.5099 |

| 4 |

0.6283 |

0.5654 |

0.5351 |

0.5179 |

0.5100 |

| 5 |

0.6281 |

0.5655 |

0.5351 |

0.5179 |

0.5100 |

| 6 |

0.6281 |

0.5655 |

0.5350 |

0.5180 |

0.5100 |

| Shanks |

0.6281 |

0.5655 |

0.5350 |

0.5180 |

0.5100 |

| 6 (N=12) |

0.6302 |

0.5684 |

0.5383 |

0.5215 |

0.5137 |

Table 11.

Convergence of for s and .

Table 11.

Convergence of for s and .

|

|

|

|

|

|

| 20 |

0.5572 |

0.4649 |

0.4028 |

0.3344 |

0.2000 |

| 40 |

0.5573 |

0.4650 |

0.4030 |

0.3351 |

0.2000 |

| 60 |

0.5573 |

0.4650 |

0.4030 |

0.3351 |

0.2000 |

| 80 |

0.5573 |

0.4650 |

0.4030 |

0.3352 |

0.2000 |

|

Shanks () |

0.5577 |

0.4648 |

0.4032 |

0.3350 |

0.2000 |

Table 12.

Convergence of for s and .

Table 12.

Convergence of for s and .

|

|

|

|

|

|

| 20 |

0.5843 |

0.5041 |

0.4603 |

0.4314 |

0.4156 |

| 40 |

0.5844 |

0.5044 |

0.4607 |

0.4320 |

0.4164 |

| 60 |

0.5844 |

0.5044 |

0.4607 |

0.4320 |

0.4164 |

| 80 |

0.5845 |

0.5045 |

0.4608 |

0.4321 |

0.4165 |

|

Shanks () |

0.5845 |

0.5045 |

0.4608 |

0.4321 |

0.4165 |

Table 13.

Convergence of for s and .

Table 13.

Convergence of for s and .

|

|

|

|

|

|

| 20 |

0.6279 |

0.5653 |

0.5348 |

0.5177 |

0.5097 |

| 40 |

0.6280 |

0.5655 |

0.5350 |

0.5179 |

0.5099 |

| 60 |

0.6281 |

0.5655 |

0.5350 |

0.5179 |

0.5099 |

| 80 |

0.6281 |

0.5655 |

0.5350 |

0.5180 |

0.5100 |

|

Shanks () |

0.6281 |

0.5655 |

0.5350 |

0.5180 |

0.5100 |