1. Introduction

We can mention energy generation, the environment, health, and biological systems where porous media flow knowledge is significant. Specifically, we have as examples oil and gas exploitation, fuel cells, batteries, solid mechanics, and cardiovascular systems [

1]. For example, numerical simulation can be used in the oil industry, which invests significant resources to reduce its costs and risks inherent to production.

We can obtain data about flow patterns by performing experiments using reservoir samples. On the other hand, information can also be collected through pressure tests in injection/producing wells and temperature and pressure data analysis. However, these are expensive and may be unfeasible when we want to study several production scenarios. For this purpose, numerical simulation becomes a valuable alternative tool [

2]. In this context, we propose here to use it to solve non-isothermal two-phase flow using a one-equation model derived without assuming the hypothesis of local thermal equilibrium.

Numerical reservoir simulation requires a prior understanding of several areas of knowledge, such as mathematics, physics, numerical methods, and advanced programming [

3], and it is widely used in the oil industry [

2]. It is due to the inherent difficulties in accurately obtaining reservoir properties throughout its extension and the complexity of determining flow behavior in situ. Therefore, it is an ally when we need to maximize hydrocarbon recovery.

We know that the hydrocarbon production stages can be divided into primary, secondary, and tertiary [

4]. In the primary, the oil or gas is obtained due to the difference in pressure between the interior of the reservoir and the surface. In the second, part of the large quantity of hydrocarbons remaining in the reservoir is recovered via the injection of an immiscible fluid, available in abundance and at low cost. Finally, we have the chemical, miscible displacement, biological, and thermal methods [

5]. All aim to promote higher mobility of hydrocarbons, decreasing the resistance to their flow and promoting increased production [

4].

In the case of conventional oils (API gravity greater than 30), production costs are comparatively lower than those associated with heavier oils [

6]. However, due to the current depletion of their reserves, special attention has been given to exploring those with API gravity between 5 and 22. On the other hand, as they have a higher viscosity, there is higher resistance to their flow, and production costs are higher [

7]. Under these circumstances, the dominant recovery techniques are thermal, non-thermal, or cold and solvent-based [

8].

Therefore, an attractive alternative to increase the recovery of heavy oils is the use of so-called thermal methods [

9]. For example, static heaters can be positioned inside the reservoir. As a result, there will be a decrease in its viscosity and a consequent increase in its fluidity [

10].

As with other recovery techniques, we can also use numerical simulation for thermal methods [

11]. The most commonly used is steam injection [

12], which has the disadvantage of requiring a large amount of available water in addition to the energy cost associated with steam generation. In addition, it causes harmful effects on the environment due to the means generally used to generate the necessary energy, causing the emission of greenhouse gases [

12]. An alternative, in situ combustion, has been applied with relative success in Canada [

8].

We can also use electric energy to heat the reservoir by introducing heating elements that transfer heat to the fluid and the rock [

7,

13]. Another possibility is electromagnetic heating, enabling localized heating and being able to transfer up to 92% of the energy generated to its surroundings [

14]. The number and location of the heating elements can vary to maximize the recovery process.

In the physical-mathematical modeling of porous media flow, compared to isothermal flow, we must consider the energy equation in non-isothermal flow in addition to the continuity and momentum equations. In the literature, one- or two-equation models are commonly used, with the second being the most suitable when there are significant differences in the order of magnitude of the thermal properties of the fluids and the porous matrix [

15,

16]. The one-equation model for single-phase flow [

11,

17,

18] can be derived with or without assuming the hypothesis of local thermodynamic equilibrium [

19]. In the case of the two-equation model [

15,

16], we use separate equations to obtain the temperature of the fluid and the rock, and the heat transfer between them is accounted for via a source term [

20].

In the most general case, we must consider a multiphase flow due to the presence of more than one phase when using advanced recovery techniques. For example, Siavashi et al. [

21] simulated the non-isothermal two-phase flow of immiscible fluids in a saturated medium, adopting the hypothesis of local thermal equilibrium, and they simulated the injection of heated water via the streamline method. On the other hand, also assuming local thermal equilibrium, Roy et al. [

22] studied the non-isothermal, compositional two-phase flow, considering the presence of chemical reactions. We find other applications in Lindner et al. [

23] and Kumar et al. [

24]. The first dealt with cooling by phase change and used a mixing model, considering a multi-component fluid, without considering local thermal equilibrium. The last one addressed the drying process in food via microwaves, in which a fluid flow model in a porous medium with phase change was used.

Although phase changes may occur due to the temperature increase inside the reservoir, we did not consider them here. As a preventive measure, we monitored the maximum temperature values to prevent them from occurring. Therefore, the case of a three-phase flow is outside the scope. In this initial work, we will only deal with the problem of injecting a heated fluid into a reservoir with slab geometry. Later, we will attack the heating problem using static heating wells.

2. Non-Isothermal Flow in Porous Media

We present below the governing equations that will provide the saturation and average temperature of the reservoir. In addition to establishing how the properties of the fluids and the porous matrix will be calculated.

We considered the following hypotheses in the model used:

the rock formation is anisotropic in terms of absolute permeability;

the rock compressibility is small and constant;

the fluids are Newtonian;

no chemical reactions occur;

the flow is laminar at a very low velocity;

the fluids have a steady chemical composition;

the flow is non-isothermal, two-phase and three-dimensional;

the fluids are slightly compressible;

the thermal conductivities of the rock and fluids are constant;

and the hypothesis of local thermal equilibrium is not considered.

For two-phase flow in porous media, we we obtain from the mass balance [

3]

where

is the porosity,

is the density,

is the superficial velocity,

S is the saturation,

is the source term, and the subscript

indicates the phase in question. Furthermore,

where

is the reference porosity, determined at the reference pressure (

) and temperature (

),

is the rock compressibility coefficient,

represents the rock thermal expansivity coefficient,

is the pressure of the non-wetting phase (oil) and

T is the mean reservoir temperature (to be defined later) [

3].

Regarding density [

3], we employ

where

is the density of the phase

under reference conditions,

is the fluid compressibility coefficient, and

is the thermal expansion coefficient of the phase

.

Although viscosity varies depending on pressure and temperature, we will only consider its variation with temperature [

11],

where

and

are constants determined for a given type of oil,

is the reference temperature for calculating viscosity, and the water viscosity is considered constant.

In two-phase flow, Darcy’s classical law must be modified by introducing the relative permeability

[

3],

where

is the relative permeability of

phase,

is the viscosity,

is the absolute permeability tensor (diagonal),

is the pressure,

, where

g is the magnitude of the acceleration due to gravity, and

Z is the depth.

Since this is a non-isothermal flow, we use a model that takes into account the variation of relative permeability as a function of temperature [

25]:

for the wetting phase (water), where

and, for the non-wetting phase,

where

,

is the saturation of the wetting phase, and the temperature

T should be given in

oC. These correlations are valid for temperatures ranging from 70 to 220 degrees Celsius.

Combining Equations (

1) and (

5), we have, for each phase,

where

is the formation-volume factor,

and

, being

and

the densities at standard (constant) conditions of the wetting phase (water), and of the non-wetting phase (oil), respectively.

The reservoir is saturated

and the effects of capillary pressure,

are accounted for [

26]

where

is the maximum capillary pressure, the exponent

must be provided,

is the irreducible water saturation, and

is the residual oil saturation.

Therefore, by substituting Equations (

10) and (

11) into Equations (

8) and (

9) we obtain the two governing equations:

As previously stated, it is common to use the assumption of local thermal equilibrium (equality of mean temperatures of fluids and porous matrix) [

22,

27]. However, in some situations, it may be inappropriate [

28]. As alternatives, we have the one-equation model without adopting such an assumption [

19], or the two-equation model [

15] or three-equations, with phase change [

28] or without phase change [

29]. Here, we employ the one-equation model (without local thermal equilibrium), whose dependent variable is the mean reservoir temperature (weighted average of the phase and rock temperatures), and the thermal heating is modeled via source terms [

11].

For constant heat capacities, the macroscopic equation governing heat transfer is [

30]:

where

represents the effective thermal dispersion tensor,

and

are the enthalpies of oil and water,

represents a volumetric thermal source (when there are heating wells),

is the total volume, and

and

represent the volumetric mass flow rates when there are injection/producing wells.

The average temperature of the porous medium, considering both phases and the rock, is given by [

30]:

where

,

,

, and

are respectively the specific heat and temperatures of the oil and water, and

T represents the average reservoir temperature. Furthermore [

30],

represents the average heat capacity.

The enthalpies of the fluids are calculated knowing the average temperature of the reservoir [

11]:

For example, after applying the Method of Volume Averaging [

31] to the energy balance equation, we see the appearance of the effective thermal dispersion tensor in the macroscopic equation describing energy transfer at the laboratory scale [

19,

32]. It contains the contribution of three terms related to thermal conduction, tortuosity, and hydrodynamic dispersion and, in the case of two-phase flow,

where

,

and

are the thermal conductivities of oil, water and rock, respectively,

is the identity tensor,

is the tortuosity tensor, and

is the hydrodynamic dispersion tensor.

We assume that the tortuosity tensor is diagonal and that its components are constant and given by [

33]:

We take the hydrodynamic dispersion tensor to be diagonal and anisotropic, with its axial

and transversal

components determined via [

32]:

where

is the Péclet number. The Reynolds (

) and Prandtl (

) numbers are defined for the mobile phases (water and oil) by

and

, where

represents the mean particle diameter of the porous medium.

2.1. Initial and Boundary Conditions

We still need to provide the initial and boundary conditions to complete the physical-mathematical model, whose governing equations are (

13), (

14), and (

15).

We provide pressure, temperature, and saturation as initial conditions at

. For pressure, their values consider the hydrostatic gradients [

3]. Similarly, for temperature, geothermal energy causes it to vary at a rate

of 25-30 K/km for the region of the Earth’s crust [

34].

Regarding boundary conditions, Dirichlet, Neumann, or Robin-type conditions can be employed on the entire boundary

or on part of it [

4].

The reservoir has a slab geometry, and the main flow is in the direction of the x-axis. At the inlet boundary, we impose a pressure gradient and the temperature and saturation of the injected fluid. At the right boundary, we establish a pressure value and zero derivatives for the saturation and temperature in the flow direction. At the other boundaries, we consider zero flow conditions and zero derivatives for saturation and temperature in the directions perpendicular to the reservoir face.

3. Numerical Resolution Methodology

In solving governing differential equations, we employ the Finite Volume Method [

2,

35]. It is a well-known method having conservative properties that make it a good option when solving systems of partial differential equations [

35]. As usual, the mean values of the dependent variables are determined at the center of the finite volumes and do not vary inside them (for a given time).

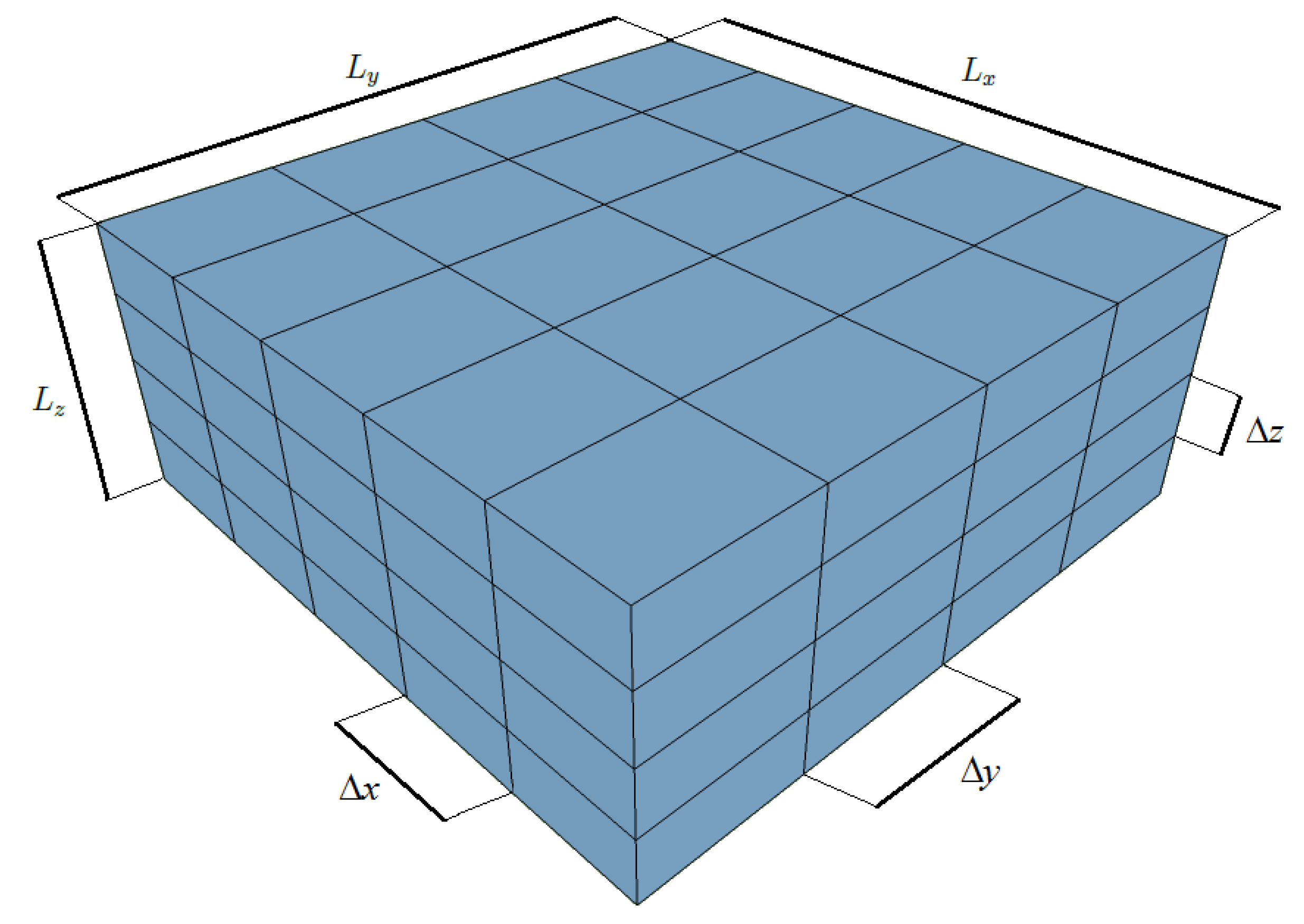

The domain of dimensions

,

, and

is discretized using

,

, and

finite volumes (whose dimensions, not necessarily constant, are

,

, and

) in the

x-,

y-, and

z-directions,

Figure 1, so that,

where the indices

i,

j and

k indicate the blocks (cells or finite volumes) in the

x-,

y- and

z-directions, respectively. In this system, we reference the boundaries (faces) of the blocks via the notation (

), (

), and (

) [

35].

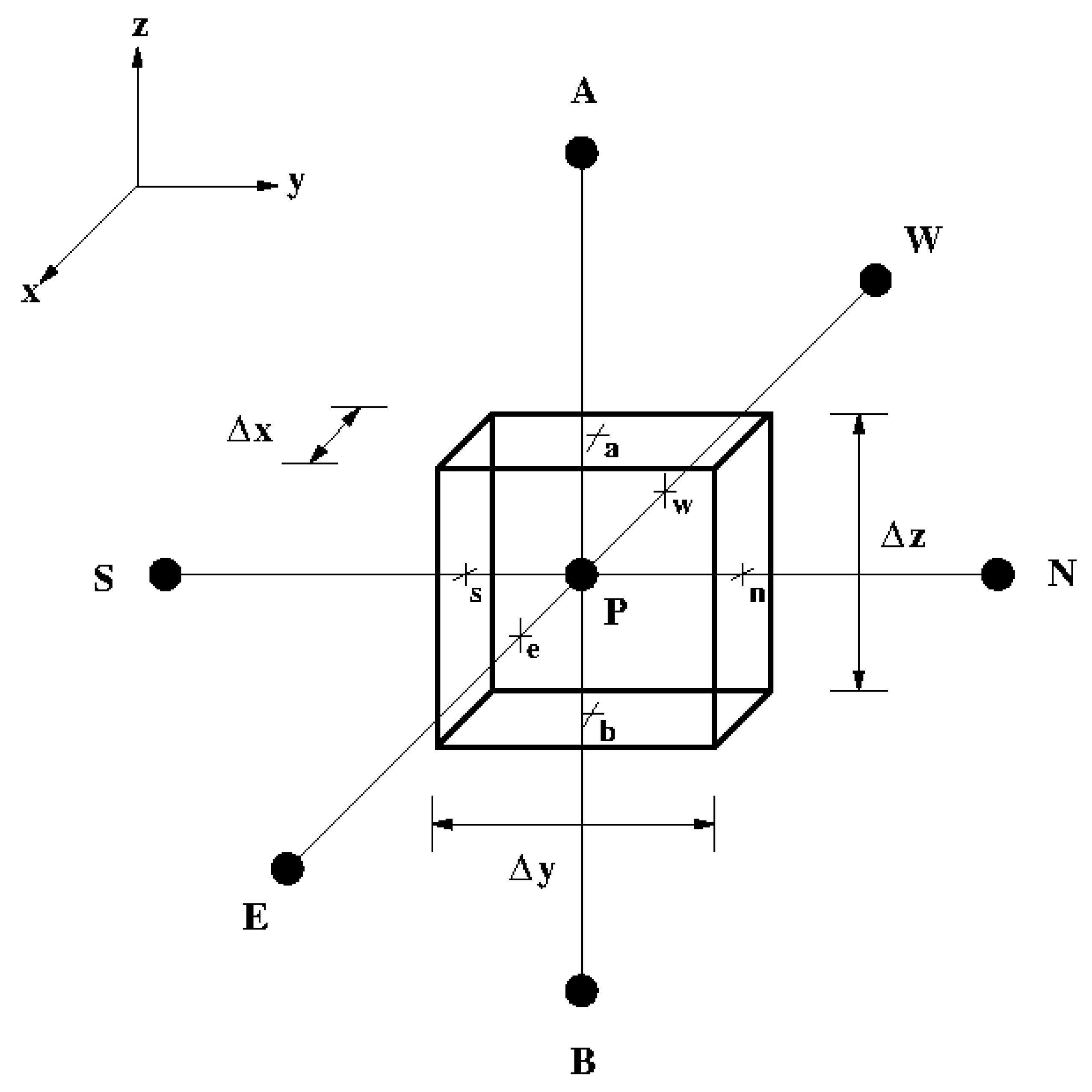

In

Figure 2, we indicate the faces of the finite volumes by

,

,

,

,

and

. On the other hand, we use capital letters when we refer to the nodes positioned at their respective centers:

,

,

,

,

, and

.

Once we have generated the computational mesh, we perform space-time integration of Equations (

13), (

14), and (

15) in each cell of the domain:

where

is the time increment and the subscript

V indicates that the integration domain is the control volume.

Since we chose a widely used method, we will omit the details concerning space-time integration of the governing equations [

30]. We opted for a fully time implicit formulation and used space-centered difference approximations.

In the discretized equations, we introduced a new variable,

, which represents the transmissibility evaluated on the faces of the finite volumes

where the subscripts

e and

w refer to the values that must be evaluated on the

and

faces,

and

represent the distances between the centers of the cells neighboring the finite volume considered, and

is the area of the face of the finite volume. Analogous expressions are obtained for the other faces in the

y- and

z-directions.

Another point of fundamental importance is the approximation of transmissibilities at the interfaces of the control volumes. These terms can be highly nonlinear due to their dependence on the unknowns of the problem. This fact can generate problems with convergence, as reported in [

36], and the stability of the numerical method. Knowing this context and remembering that we define the properties at the centroid of the finite volume, we must introduce appropriate approximations to overcome these issues. First, we calculate

from the product between a geometric term,

G, and two dependent on the dependent variables,

. Then,

For example, the geometric terms appearing in the three balance equations are approximated on the east face

e by

where the permeability, in turn, is determined via a harmonic mean

and the same type of approximation is used for the thermal conductivities that appear in the diffusion term of the energy equation.

The

F terms can be computed in two different ways. For example, we used a centered difference scheme (uniform mesh) for those that are pressure- and temperature-dependent (weakly nonlinear)

while for the saturation-dependent terms, which are strongly nonlinear, it is done using a first-order upwind scheme. For example, for relative permeability

That is, it is the calculation of the relative permeabilities on the faces of the finite volumes. The capillary pressures on the faces are calculated analogously.

After carrying out all the steps recommended by the Finite Volume Method, we obtained the discretized form for the non-wetting phase (oil) [

30]

where

refers to the set of faces of the finite volume, the term

is given by

and with respect to gravitational effects,

The terms coming from the transient term are given by

where

.

Continuing, we present the discretized equation for the wetting phase (water) [

30]

where

refers to the summation on each face

d and, at the same time, on each centroid of the neighboring cell

D, for the same spatial direction. Furthermore, the gravity term is given by

and the other ones are

Finally, we present the discretized form of the energy equation [

30]

where

and the advective, gravitational and source terms are given, respectively, by

It is worth noting that the nonlinear system formed by these three equations is coupled since the oil pressure and water saturation depend on the average temperature value.

3.1. Operator Splitting and Linearization

Since we decided to use linear algebra methods, we must linearize the system of discretized equations. To do so, we opted for the Picard Method [

37],

where

represents, for example, the transmissibility evaluated at time

, but at the previous iterative level

v. On the other hand, the dependent variables are calculated at

, where

is the subsequent iterative level. Therefore, we have an external iterative process linked to the Picard Method and an internal one for the numerical resolution of the system of discretized equations.

However, in the present work, we employed an Operator Splitting Method [

16,

38,

39] to enable the unknowns of the system to be determined by solving the equations sequentially. Thus, it was possible to arbitrate the most appropriate algebraic methods for each of them [

36].

We established the following resolution order [

30]:

firstly, the subsystem that will provide the pressure of the non-wetting phase is solved (Equation (

33));

next, the saturation of the wetting phase is obtained (Equation (

39));

finally, the average temperature of the reservoir is determined (Equation (

44)).

3.2. Resolution of Linear Algebraic Systems

Due to the strategy employed in solving the governing equations, the pressure and average temperature are determined via the Preconditioned Conjugate Gradient Method [

4], while the saturation is obtained using the Preconditioned Stabilized Biconjugate Gradient Method [

40].

The choice of preconditioned methods was based on the possibility of accelerating the convergence process of iterative methods. To this end, preconditioners constructed from the incomplete LU Factorization process were used [

41].

5. Conclusions

In this work, we developed a numerical simulator to solve the problem of non-isothermal three-dimensional two-phase flow in an oil reservoir, and we solved the subsystems for oil pressure, water saturation, and average temperature sequentially. The coefficients of the equations that appear in these subsystems are linearized using the Picard method, and we calculated implicitly pressure and the water saturation. When calculating the average temperature, we did not consider the hypothesis of local thermal equilibrium, and we also used an implicit formulation in time. The effects of tortuosity and hydrodynamic dispersion are taken into account.

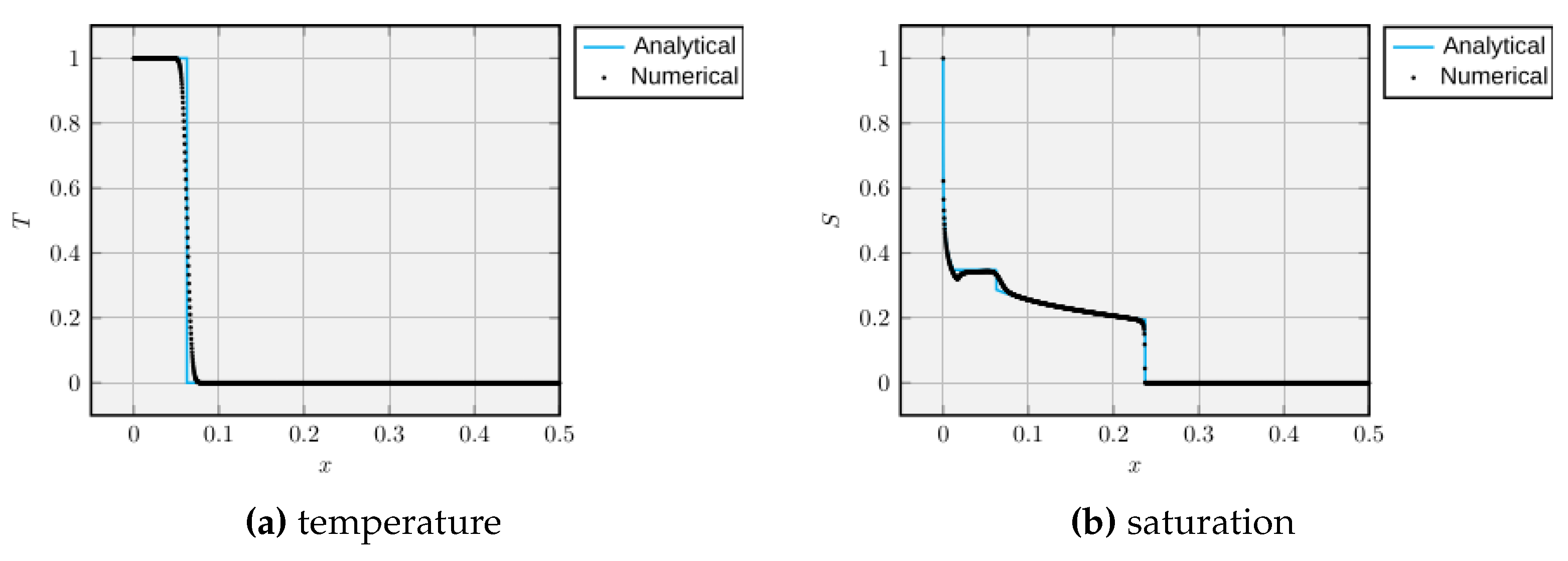

The numerical code was validated based on a problem already known in the literature and that has an analytical solution. From its resolution, it was possible to verify the numerical convergence and that the numerical results reproduced those provided by theory. However, we observed a small smoothing due to numerical diffusion caused by the first-order upwind scheme.

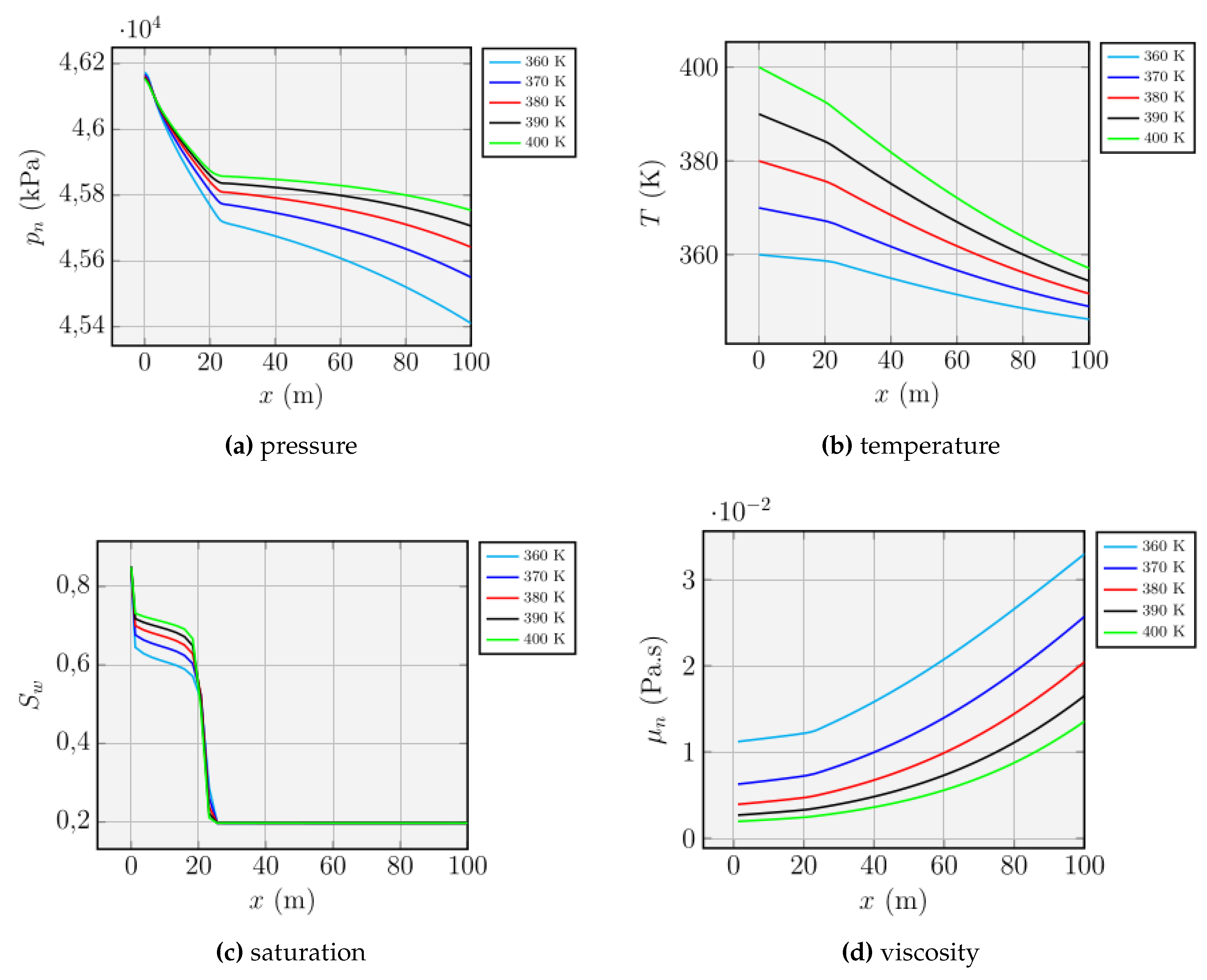

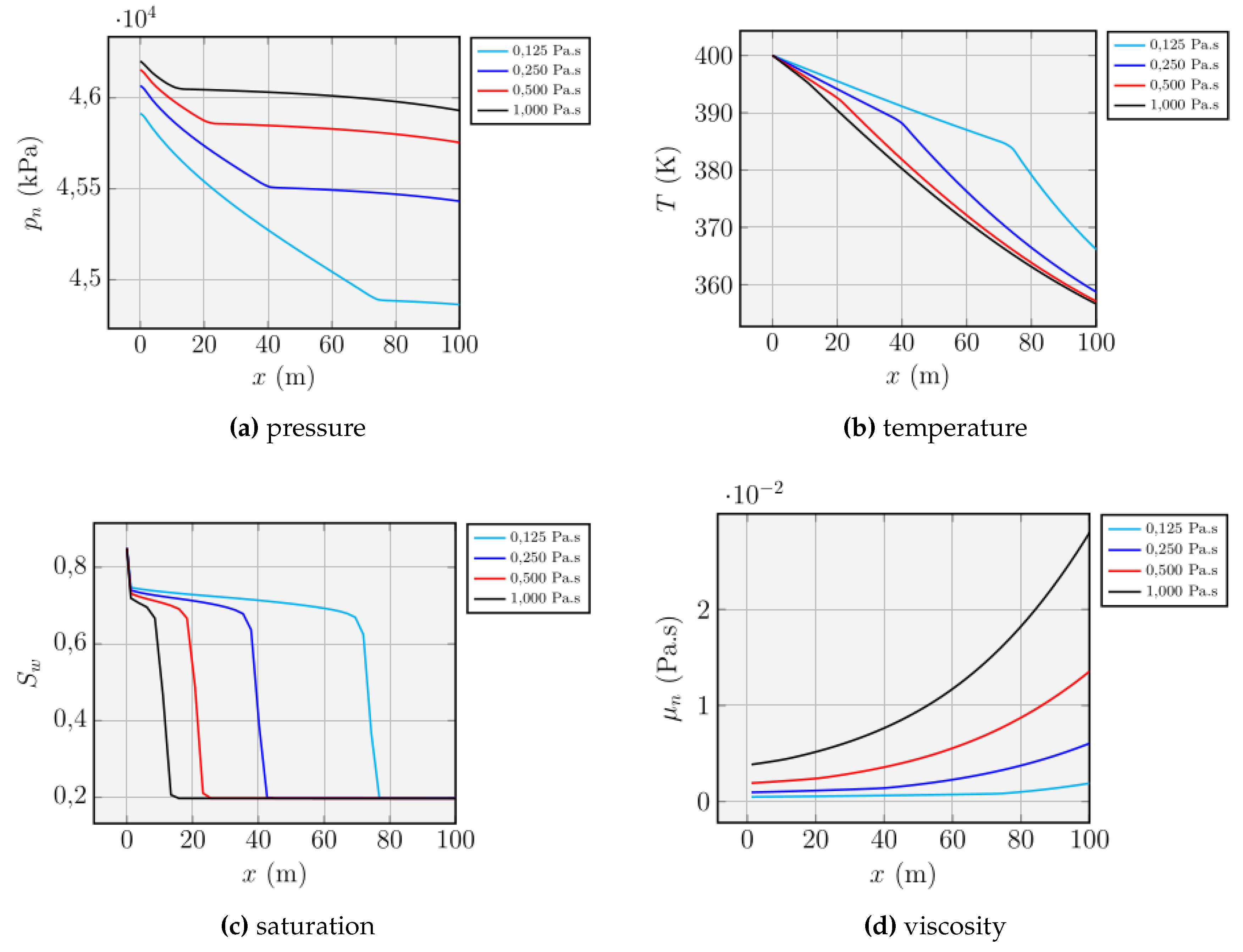

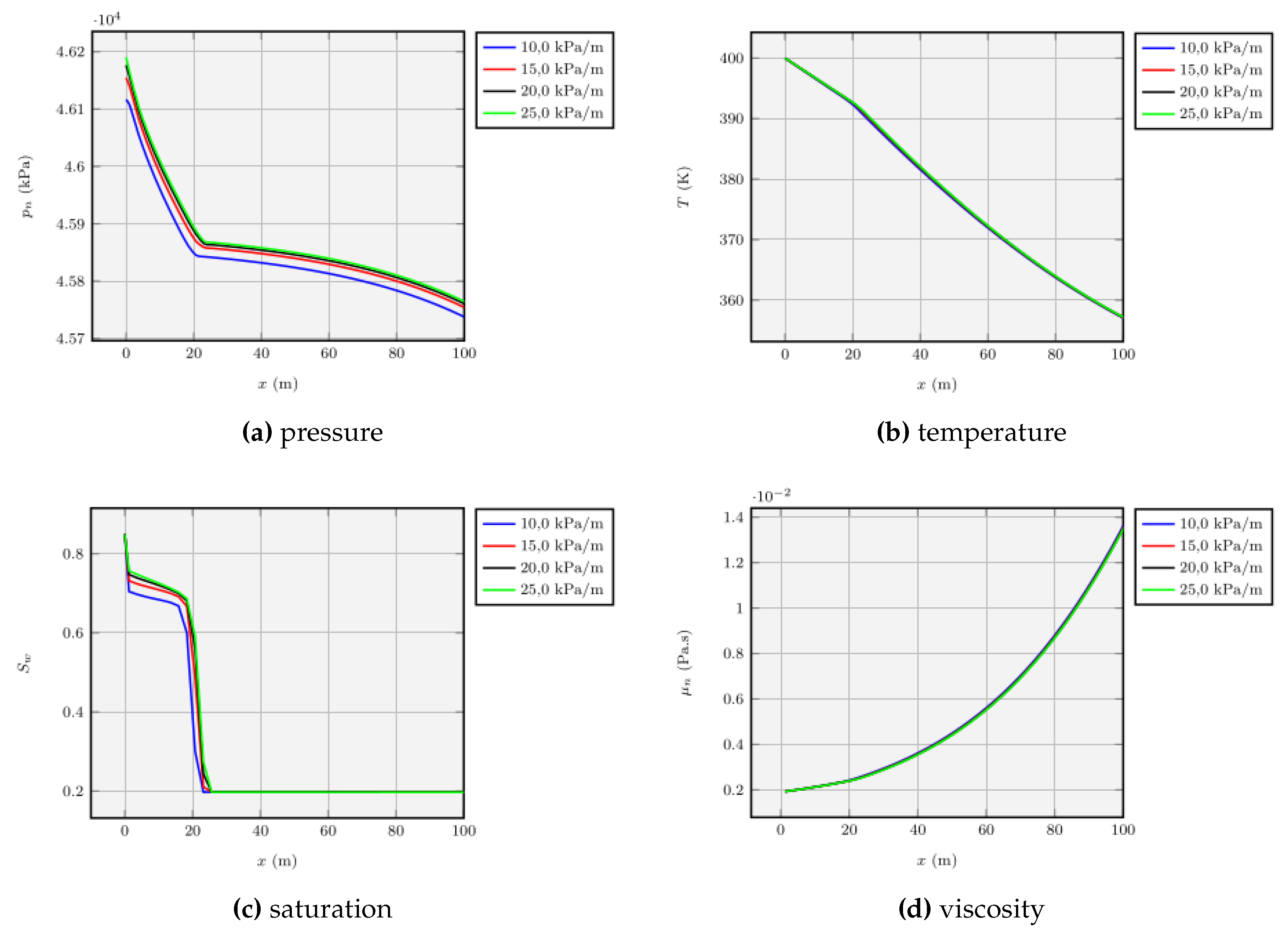

Unquestionably, the variation of the injection temperature proved to be the more efficient technique with regard to oil recovery for the cases we tested in the sensitivity analysis, taking into account the value of water saturation at the end of the rarefaction curve. For higher temperatures, there is a reduction in viscosity and the amount of oil found in the region swept by the heated water.

In the other cases, we did not obtain comparable practical gains in swept efficiency despite the reduction in oil viscosity. In the first test case, variation of the injected fluid temperature, the water saturation immediately before the discontinuity, which defines the position of the advancing front, went from approximately 0.55 to 0.65 for the lowest and highest values of water injection temperature, an increase of about 18%.

Overall, the sequential method and the methodologies for discretization, linearization, and solution of algebraic systems proved to be effective when applied to the problem of non-isothermal two-phase flow.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, G.d.S. and H.P.A.S.; methodology, M.M.d.F., G.d.S and H.P.A.S.; software, J.D.d.S.H., M.M.d.F. and G.d.S.; validation, J.D.d.S.H., G.d.S. and H.P.A.S.; formal analysis, J.D.d.S.H., M.M.d.F., G.d.S and H.P.A.S.; investigation, J.D.d.S.H., M.M.d.F., G.d.S and H.P.A.S.; resources, J.D.d.S.H., M.M.d.F., G.d.S and H.P.A.S.; data curation, J.D.d.S.H., M.M.d.F., G.d.S and H.P.A.S.; writing—original draft preparation, H.P.A.S; writing—review and editing, J.D.d.S.H., M.M.d.F., G.d.S and H.P.A.S.; visualization, J.D.d.S.H.; supervision, G.d.S and H.P.A.S.; project administration, G.d.S and H.P.A.S.; funding acquisition, G.d.S and H.P.A.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.